Annotation of the 12th Chromosome of the Forest Pathogen Fusarium circinatum

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Analysis In Silico

3. Results

In Silico Characterisation of Putative F. circinatum Genes

4. Discussion

4.1. Distribution of F. circinatum, the Causative Agent of PPC Disease

4.2. Development of New Diagnostic Methods to Ensure Reduction of PPC

4.3. Pathways of Transmission and Potential Host Risk of the Pathogen

4.4. Risk of Establishing the Pathogen in New Regions in Europe

4.5. Possible Interactions between F. circinatum and Other Fungal Species

4.6. In Silico Approach to the Identification and Characterisation of Genes

5. Conclusions

- Overall, the knowledge gained in this study about the annotations of genes, ORFs and domains in the 12th chromosome of F. circinatum could make an important contribution to the management of PPC disease and to strategies for containment and mitigation strategies.

- Our study can serve to clarify the phylogeny of the species and furthermore to develop new molecular detection tools.

- The genomic organisation of virulence genes can be used to clarify the relationship between F. ciricantum and hosts.

- We concluded that at least 14 genes are associated with pathogenesis/virulence.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Localization and Annotation of Putative F. circinatum Proteins

| Gene | Strand | Localization | No. Introns | Transcript | Localization | Predicted Protein Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | 31217–31960 | 2 | 1 | 31217–31219 | 196 |

| + | 2 | 2 | 31229–31960 | 192 | ||

| 2 | + | 33294–34089 | 1 | 33294–34089 | 238 | |

| 3 | − | 36737–36989 | 1 | 36737–36989 | 68 | |

| 4 | + | 38485–39264 | 0 | 38485–39264 | 259 | |

| 5 | + | 40947–41501 | 0 | 40947–41501 | 184 | |

| 6 | − | 42288–44793 | 7 | 1 | 42288–44793 | 687 |

| 7 | 2 | 42288–44793 | 687 | |||

| 7 | + | 47832–50343 | 3 | 47832–50343 | 712 | |

| 8 | + | 50528–51772 | 0 | 50528–51772 | 414 | |

| 9 | − | 53269–53616 | 0 | 53269–53616 | 115 | |

| 10 | − | 53692–54501 | 0 | 53692–54501 | 269 | |

| 11 | − | 58288–59517 | 1 | 58288–59517 | 393 | |

| 12 | − | 67276–67674 | 0 | 67276–67674 | 132 | |

| 13 | − | 69092–69550 | 0 | 69092–69550 | 152 | |

| 14 | − | 71147–71430 | 0 | 71147–71430 | 75 | |

| 15 | + | 71985–72521 | 1 | 71985–72521 | 136 | |

| 16 | − | 76693–77699 | 1 | 76693–77699 | 300 | |

| 17 | + | 81870–83876 | 0 | 81870–83876 | 668 | |

| 18 | − | 83977–85827 | 0 | 83977–85827 | 618 | |

| 19 | − | 87569–88259 | 2 | 87569–88259 | 194 | |

| 20 | + | 89834–92287 | 0 | 89834–92287 | 817 | |

| 21 | + | 95681–96392 | 1 | 1 | 95681–96392 | 219 |

| + | 1 | 2 | 95777–96392 | 187 | ||

| 22 | − | 101909–103049 | 4 | 1 | 101973–103049 | 148 |

| 5 | 2 | 101909–103049 | 195 | |||

| 23 | + | 104774–105565 | 2 | 104774–105565 | 223 | |

| 24 | + | 108785–110371 | 0 | 108785–110371 | 528 | |

| 25 | + | 115888–116535 | 2 | 115888–116535 | 146 | |

| 26 | − | 117728–122084 | 2 | 117728–122084 | 1379 | |

| 27 | − | 130442–131614 | 4 | 130442–131614 | 323 | |

| 28 | + | 133748–134953 | 3 | 1 | 133982–134953 | 271 |

| 6 | 2 | 133748–134953 | 297 | |||

| 29 | − | 138883–139227 | 0 | 138883–139227 | 114 | |

| 30 | − | 143831–145637 | 5 | 143831–145637 | 441 | |

| 31 | + | 145727–148851 | 11 | 145727–148851 | 475 | |

| 32 | + | 156385–157122 | 1 | 156385–157122 | 228 | |

| 33 | − | 157739–158284 | 0 | 157739–158284 | 181 | |

| 34 | − | 165252–166541 | 0 | 165252–166541 | 429 | |

| 35 | − | 167760–169128 | 2 | 167760–169128 | 311 | |

| 36 | + | 171554–172271 | 1 | 1 | 171554–172271 | 178 |

| 2 | 171578–172271 | 170 | ||||

| 37 | + | 173661–174852 | 2 | 173661–174852 | 364 | |

| 38 | + | 177631–179403 | 3 | 177631–179403 | 368 | |

| 39 | − | 179756–180727 | 2 | 1 | 179756–180727 | 285 |

| 2 | 2 | 179756–180727 | 288 | |||

| 40 | + | 180965–181919 | 1 | 180965–181919 | 209 | |

| 41 | − | 181947–182603 | 2 | 181947–182603 | 185 | |

| 42 | − | 184433–186403 | 3 | 1 | 184433–186403 | 436 |

| 4 | 2 | 184433–186403 | 461 | |||

| 43 | − | 197699–198520 | 1 | 197699–198520 | 131 | |

| 44 | + | 201599–202213 | 0 | 201599–202213 | 204 | |

| 45 | − | 206352–206792 | 1 | 206352–206792 | 114 | |

| 46 | − | 212670–213117 | 1 | 212670–213117 | 117 | |

| 47 | − | 217694–218296 | 1 | 217694–218296 | 134 | |

| 48 | − | 219886–220412 | 1 | 219886–220412 | 153 | |

| 49 | + | 241829–243064 | 4 | 241829–243064 | 292 | |

| 50 | + | 249462–249912 | 1 | 249462–249912 | 132 | |

| 51 | − | 255019–255430 | 1 | 255019–255430 | 117 | |

| 52 | − | 260511–267687 | 4 | 260511–267687 | 1871 | |

| 53 | + | 267833–269506 | 0 | 267833–269506 | 557 | |

| 54 | + | 269924–270610 | 0 | 269924–270610 | 228 | |

| 55 | − | 270814–272503 | 4 | 1 | 270814–272503 | 442 |

| 4 | 2 | 270814–272503 | 433 | |||

| 56 | − | 279820–281924 | 2 | 279820–281924 | 636 | |

| 57 | + | 284917–288900 | 5 | 284917–288900 | 1103 | |

| 58 | + | 290740–294512 | 8 | 1 | 290740–294512 | 993 |

| 8 | 2 | 290740–290742 | 1008 | |||

| 59 | − | 296603–298423 | 1 | 296603–298423 | 465 | |

| 60 | − | 299021–300337 | 0 | 299021–300337 | 436 | |

| 61 | + | 301149–301535 | 0 | 301149–301535 | 128 | |

| 62 | + | 306378–309789 | 3 | 306378–309789 | 987 | |

| 63 | + | 312081–313133 | 0 | 312081–313133 | 350 | |

| 64 | − | 314421–314718 | 1 | 314421–314718 | 82 | |

| 65 | − | 316363–317384 | 2 | 316363–317384 | 304 | |

| 66 | + | 319615–321355 | 1 | 1 | 319636–321355 | 550 |

| 1 | 2 | 319615–321355 | 557 | |||

| 67 | − | 321897–322763 | 0 | 321897–322763 | 288 | |

| 68 | + | 324749–325970 | 3 | 324749–325970 | 339 | |

| 69 | + | 327367–328119 | 0 | 327367–328119 | 250 | |

| 70 | − | 328511–329701 | 0 | 328511–329701 | 396 | |

| 71 | − | 333730–334527 | 0 | 333730–334527 | 165 | |

| 72 | − | 335535–336444 | 1 | 335535–336444 | 141 | |

| 73 | + | 339435–340126 | 1 | 1 | 339435–340042 | 186 |

| 2 | 2 | 339435–340126 | 196 | |||

| 74 | − | 340698–341147 | 2 | 340698–341147 | 116 | |

| 75 | − | 344219–347477 | 2 | 344219–347477 | 1042 | |

| 76 | + | 349423–350519 | 2 | 1 | 349423–350519 | 331 |

| 1 | 2 | 349423–350519 | 347 | |||

| 77 | − | 352248–352879 | 1 | 352248–352879 | 118 | |

| 78 | + | 353875–354707 | 1 | 353875–354707 | 235 | |

| 79 | + | 358678–362423 | 5 | 358678–362423 | 1046 | |

| 80 | − | 364509–365599 | 1 | 364509–365599 | 346 | |

| 81 | − | 368775–372232 | 5 | 1 | 368775–372232 | 660 |

| 5 | 2 | 368775–372232 | 634 | |||

| 82 | − | 373134–374775 | 1 | 373134–374775 | 527 | |

| 83 | + | 375893–377234 | 1 | 375893–377234 | 428 | |

| 84 | − | 377746–379869 | 2 | 377746–379869 | 638 | |

| 85 | + | 381383–382024 | 0 | 381383–382024 | 213 | |

| 86 | + | 384422–387495 | 3 | 1 | 386043–387495 | 418 |

| 0 | 2 | 384422–385309 | 295 | |||

| 5 | 3 | 384422–387495 | 754 | |||

| 87 | + | 389607–393031 | 6 | 1 | 389607–393031 | 550 |

| 7 | 2 | 389607–393031 | 531 | |||

| 88 | + | 393067–393411 | 0 | 393067–393411 | 114 | |

| 89 | + | 396581–397378 | 1 | 1 | 396650–397378 | 167 |

| 1 | 2 | 396581–397378 | 190 | |||

| 90 | − | 399885–401207 | 2 | 399885–401207 | 504 | |

| 91 | − | 403346–403807 | 0 | 403346–403807 | 153 | |

| 92 | − | 405413–405787 | 2 | 1 | 405413–405787 | 92 |

| 1 | 2 | 405413–405738 | 91 | |||

| 93 | − | 412668–413939 | 1 | 412668–413939 | 407 | |

| 94 | + | 418703–419415 | 2 | 418703–419415 | 201 | |

| 95 | − | 419654–420268 | 0 | 419654–420268 | 204 | |

| 96 | − | 423279–424095 | 2 | 423279–424095 | 240 | |

| 97 | − | 432389–433183 | 0 | 432389–433183 | 264 | |

| 98 | − | 437147–438263 | 1 | 437147–438263 | 327 | |

| 99 | − | 441782–442974 | 1 | 1 | 441782–442974 | 379 |

| 2 | 2 | 441782–442974 | 349 | |||

| 100 | − | 444928–446536 | 2 | 444928–446536 | 502 | |

| 101 | + | 447456–448802 | 3 | 447456–448802 | 392 | |

| 102 | + | 451345–452097 | 0 | 451345–452097 | 250 | |

| 103 | + | 459258–461038 | 2 | 459258–461038 | 552 | |

| 104 | + | 462490–462897 | 1 | 462490–462897 | 102 | |

| 105 | − | 465130–468729 | 9 | 465130–468729 | 888 | |

| 106 | + | 476676–478090 | 1 | 476676–478090 | 448 | |

| 107 | − | 481803–482006 | 0 | 481803–482006 | 67 | |

| 108 | − | 486871–487349 | 1 | 486871–487349 | 141 | |

| 109 | − | 490202–492772 | 4 | 490202–492772 | 528 | |

| 110 | + | 490202–492772 | 1 | 490202–492772 | 156 | |

| 111 | + | 497012–498151 | 0 | 497012–498151 | 379 | |

| 112 | + | 499716–500198 | 0 | 499716–500198 | 160 | |

| 113 | − | 502582–504360 | 1 | 502582–504360 | 508 | |

| 114 | + | 506239–507444 | 3 | 1 | 506239–507444 | 174 |

| 2 | 2 | 506239–507444 | 161 | |||

| 115 | + | 508757–509677 | 2 | 1 | 508757–509677 | 198 |

| 3 | 2 | 508757–509677 | 239 | |||

| 116 | + | 511677–512903 | 0 | 511677–512903 | 408 | |

| 117 | − | 513379–514311 | 2 | 513379–514311 | 137 | |

| 118 | + | 515695–516607 | 1 | 515695–516607 | 249 |

| Protein | Length (AA) | Best Match ID | Accession No. (Best Match) | E Value | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g1t1 | 196 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1200 F. circinatum | KAF5689737.1 | 100.00 | |

| g1t2 | 192 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1200 F. circinatum | XP_049150203.1 | 100.00 | |

| g2t1 | 238 | Cell wall beta-glucan synthesis, FCIRC_1201, F. circinatum | KAF5689738.1 | 100.00 | |

| g3t1 | 68 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1202, F. circinatum | KAF5689739.1 | 100.00 | |

| g4t1 | 258 | Hypothetical protein, FCIRC_1203 F. circinatum | KAF5689740.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g5t1 | 184 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1204 F. circinatum | KAF5689741.1 | 100.00 | |

| g6t1 | 687 | Tyrosinase precursor, FCIRC_1205, F. circinatum | KAF5689742.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g6t2 | 687 | Tyrosinase precursor, FCIRC_1205, F. circinatum | KAF5689742.1 | 0.0 | 98.84 |

| g7t1 | 712 | Extracellular gdsl-like lipase, FCIRC_1206, F. circinatum | KAF5689743.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g8t1 | 414 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1207 F. circinatum | KAF5689744.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g9t1 | 115 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1208, F. circinatum | KAF5689745.1 | 100.00 | |

| g10t1 | 269 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1209, F. circinatum | KAF5689746.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g11t1 | 393 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1210, F. circinatum | KAF5689747.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g12t1 | 132 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1211, F. circinatum | KAF5689748.1 | 100.00 | |

| g13t1 | 152 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1212, F. circinatum | KAF5689749.1 | 100.00 | |

| g14t1 | 75 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1213, F. circinatum | KAF5689750.1 | 100.00 | |

| g15t1 | 136 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1214, F. circinatum | KAF5689751.1 | 100.00 | |

| g16t1 | 300 | Serine threonine kinase, FCIRC_1215, F. circinatum | KAF5689752.1 | 81.33 | |

| g17t1 | 668 | Hypothetical protein CIRC_1216, F. circinatum | KAF5689753.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g18t1 | 616 | Hypothetical protein CIRC_1217, F. circinatum | KAF5689754.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g19t1 | 194 | Hypothetical protein CIRC_1218, F. circinatum | KAF5689755.1 | 100.00 | |

| g20t1 | 817 | Transcription factor jumonji, FCIRC_1219, F. circinatum | KAF5689756.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g21t1 | 219 | Hypothetical protein CIRC_1220, F. circinatum | KAF5689757.1 | 92.80 | |

| g21t2 | 187 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1220, F. circinatum | KAF5689757.1 | 91.67 | |

| g22t1 | 148 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1222, F. circinatum | KAF5689759.1 | 99.23 | |

| g22t2 | 195 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1222, F. circinatum | KAF5228515.1 | 93.33 | |

| g23t1 | 223 | Hypothetical protein CIRC_1223, F. circinatum | KAF5689760.1 | 100.00 | |

| g24t1 | 528 | Hypothetical protein CIRC_1224, F. circinatum | KAF5689761.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g25t1 | 146 | Hypothetical protein CIRC_1225, F. circinatum | KAF5689762.1 | 100.00 | |

| g26t1 | 1379 | Ankyrin repeat protein, FCIRC_1226, F. circinatum | KAF5689763.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g27t1 | 323 | Hypothetical protein CIRC_1227, F. circinatum | KAF5689764.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g28t1 | 271 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1228, F. circinatum | KAF5689765.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g28t2 | 297 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1228, F. circinatum | KAF5689765.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g29t1 | 114 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1229, F. circinatum | KAF5689766.1 | 100.00 | |

| g30t1 | 441 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1230, F. circinatum | KAF5689767.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g31t1 | 475 | Translation initiation factor IF-2, FCIRC_1231, F. circinatum | KAF5689768.1 | 96.51 | |

| g32t1 | 228 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1232, F. circinatum | KAF5689769.1 | 100.00 | |

| g33t1 | 181 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1233, F. circinatum | KAF5689770.1 | 100.00 | |

| g34t1 | 429 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1234, F. circinatum | KAF5689771.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g35t1 | 311 | C2H2 transcription factor, FCIRC_1235, F. circinatum | KAF5689772.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g36t1 | 178 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1237, F. circinatum | KAF5689774.1 | 100.00 | |

| g36t2 | 170 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1237, F. circinatum | KAF5689774.1 | 100.00 | |

| g37t1 | 364 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1729, F. circinatum | KAF5688719.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g38t1 | 368 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1731, F. circinatum | KAF5688721.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g39t1 | 285 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1732, F. circinatum | KAF5688722.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g39t2 | 288 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1732, F. circinatum | KAF5688722.1 | 0.0 | 98.61 |

| g40t1 | 209 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1733, F. circinatum | KAF5688723.1 | 100.00 | |

| g41t1 | 185 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1734, F. circinatum | KAF5688724.1 | 100.00 | |

| g42t1 | 436 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1735, F. circinatum | KAF5688725.1 | 0.0 | 99.74 |

| g42t2 | 461 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1735, F. circinatum | KAF5688725.1 | 0.0 | 99.74 |

| g43t1 | 131 | FK506-binding protein, FCIRC_1236, F. circinatum | KAF5688726.1 | 100.00 | |

| g44t1 | 204 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1737, F. circinatum | KAF5688727.1 | 100.00 | |

| g45t1 | 114 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1738 F. circinatum | KAF5688728.1 | 100.00 | |

| g46t1 | 117 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1739 F. circinatum | KAF5688729.1 | 100.00 | |

| g47t1 | 134 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_1740, F. circinatum | KAF5688730.1 | 100.00 | |

| g48t1 | 153 | Arginine deiminase type-3, F. mexicanum | KAF5555127.1 | 95.83 | |

| g49t1 | 292 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_10050, F. circinatum | KAF5666814.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g50t1 | 132 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_10051, F. circinatum | KAF5666815.1 | 100.00 | |

| g51t1 | 117 | Sterol 3beta-glucosyltransferase, FCIRC_10052, F. circinatum | KAF5666816.1 | 100.00 | |

| g52t1 | 1871 | NACHT ankyrin domain-containing protein, FCIRC_10053, F. circinatum | KAF5666817.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g53t1 | 557 | NCS1 nucleoside transporter, FCIRC_10054, F. circinatum | KAF5666818.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g54t1 | 228 | Asp glu hydantoin racemase, FCIRC_10055, F. circinatum | KAF5666819.1 | 100.00 | |

| g55t1 | 442 | C6 transcription factor, FCIRC_10056, F. circinatum | KAF5666820.1 | 0.0 | 97.96 |

| g55t2 | 433 | C6 transcription factor, FCIRC_10056, F. circinatum | KAF5666820.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g56t1 | 638 | CMGC DYRK kinase, FCIRC_10058, F. circinatum | KAF5666822.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g57t1 | 1103 | Serine threonine kinase, FCIRC_10059, F. circinatum | KAF5666823.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g58t1 | 993 | NACHT domain-containing protein, FCIRC_5226, F. circinatum | KAF5682015.1 | 0.0 | 99.59 |

| g58t2 | 1008 | NACHT domain-containing protein, FCIRC_5226, F. circinatum | KAF5682015.1 | 0.0 | 92.73 |

| g59t1 | 465 | TPR domain-containing protein, F. denticulatum | KAF5674688.1 | 0.0 | 55.26 |

| g60t1 | 438 | TPR domain-containing protein, FCIRC_5228, F. circinatum | KAF5682016.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g61t1 | 128 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_5229, F. circinatum | KAF5682017.1 | 100.00 | |

| g62t1 | 987 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_5230, F. circinatum | KAF5682018.1 | 0.0 | 92.40 |

| g63t1 | 350 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_5231, F. circinatum | KAF5682019.1 | 0.0 | 98.86 |

| g64t1 | 82 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_5232, F. circinatum | KAF5682020.1 | 100.00 | |

| g65t1 | 304 | Aspartate aminotransferase, FCIRC_5233, F. circinatum | KAF5682021.1 | 100.00 | |

| g66t1 | 550 | Multidrug resistance protein fnx1, FCIRC_8030, F. circinatum | KAF5673567.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g66t2 | 557 | Multidrug resistance protein fnx1, FCIRC_8030, F. circinatum | KAF5673567.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g67t1 | 288 | D-isomer specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase, FCIRC_8029, F. circinatum | KAF5673566.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g68t1 | 339 | Macrophomate synthase, FCIRC_8028, F. circinatum | KAF5673565.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g69t1 | 250 | Demethylmenaquinone methyltransferase family, FCIRC_8027, F. circinatum | KAF5673564.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g70t1 | 396 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8026 F. circinatum | KAF5673563.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g71t1 | 165 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8025, F. circinatum | KAF5673562.1 | 100.00 | |

| g72t1 | 141 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8024, F. circinatum | KAF5673561.1 | 100.00 | |

| g73t1 | 186 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8023, F. circinatum | KAF5673560.1 | 100.00 | |

| g73t2 | 196 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8023, F. circinatum | KAF5673560.1 | 100.00 | |

| g74t1 | 116 | SNF2 family domain containing protein, F. agapanthi | KAF4497424.1 | 92.24 | |

| g75t1 | 1042 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8022, F. circinatum | KAF5673559.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g76t1 | 331 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8021, F. circinatum | KAF5673558.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g76t2 | 347 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8021, F. circinatum | KAF5673558.1 | 0.0 | 95.39 |

| g77t1 | 118 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8020, F. circinatum | KAF5673557.1 | 100.00 | |

| g78t1 | 235 | Kinase-like domain-containing protein, FCIRC_8019, F. circinatum | KAF5673556.1 | 87.97 | |

| g79t1 | 1046 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8018, F. circinatum | KAF5673555.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g80t1 | 346 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8017, F. circinatum | KAF5673554.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g81t1 | 660 | Para-nitrobenzyl esterase, FCIRC_8016, F. circinatum | KAF5673553.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g81t2 | 634 | Para-nitrobenzyl esterase, FCIRC_8016, F. circinatum | KAF5673553.1 | 0.0 | 96.06 |

| g82t1 | 527 | Cutinase transcription factor 1 alpha, FCIRC_8015, F. circinatum | KAF5673552.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g83t1 | 428 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8014, F. circinatum | KAF5673551.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g84t1 | 638 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8013, F. circinatum | KAF5673550.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g85t1 | 213 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8012, F. circinatum | KAF5673549.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g86t1 | 418 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8010, F. circinatum | KAF5673547.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g86t2 | 295 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8011, F. circinatum | KAF5673548.1 | 0.0 | 97.97 |

| g86t3 | 754 | SGL domain-containing protein, Fusarium sp. LHS14.1 | KAI8724150.1 | 52.38 | |

| g87t1 | 550 | ATP synthase F1, FCIRC_8009, F. circinatum | KAF5673546.1 | 0.0 | 91.65 |

| g87t2 | 531 | ATP synthase F1, FCIRC_8009, F. circinatum | KAF5673546.1 | 0.0 | 87.94 |

| g88t1 | 114 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8008, F. circinatum | KAF5673545.1 | 100.00 | |

| g89t1 | 167 | Caspase, FCIRC_8007, F. circinatum | KAF5673544.1 | 100.00 | |

| g89t2 | 190 | Caspase, FCIRC_8007, F. circinatum | KAF5673544.1 | 100.00 | |

| g90t1 | 405 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8006, F. circinatum | KAF5673543.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g91t1 | 153 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8005, F. circinatum | KAF5673542.1 | 100.00 | |

| g92t1 | 92 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8004, F. circinatum | KAF5673541.1 | 100.00 | |

| g92t2 | 91 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_8004, F. circinatum | KAF5673541.1 | 86.52 | |

| g93t1 | 407 | Transaldolase, FCIRC_7317, F. circinatum | KAF5675701.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g94t1 | 201 | Aromatic prenyltransferase, FCIRC_7316, F. circinatum | KAF5675700.1 | 100.00 | |

| g95t1 | 204 | Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, FCIRC_7315, F. circinatum | KAF5675699.1 | 100.00 | |

| g96t1 | 240 | Nonribosomal peptide synthase, FCIRC_7314, F. circinatum | KAF5675698.1 | 100.00 | |

| g97t1 | 264 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7313, F. circinatum | KAF5675697.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g98t1 | 327 | Uncharacterized protein FSUBG_13770, F. subglutinans | XP_036530762.1 | 64.23 | |

| G99t1 | 379 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7311, F. circinatum | KAF5675696.1 | 0.0 | 84.22 |

| g99t2 | 349 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7311, F. circinatum | KAF5675696.1 | 0.0 | 76.34 |

| g100t1 | 502 | Rhs repeat-associated core domain-containing protein, FCIRC_7310, F. circinatum | KAF5675695.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g101t1 | 392 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7309, F. circinatum | KAF5675694.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g102t1 | 250 | Esterase SGNH hydrolase-type subgroup, FCIRC_7308, F. circinatum | KAF5675693.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g103t1 | 552 | SET domain-containing protein, FCIRC_7305, F. circinatum | KAF5675692.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g104t1 | 102 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7306, F. circinatum | KAF5675691.1 | 100.00 | |

| g105t1 | 888 | Major facilitator superfamily transporter, FCIRC_7305 F. circinatum | KAF5675690.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g106t1 | 448 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7304, F. circinatum | KAF5675689.1 | 0.0 | 95.12 |

| g107t1 | 67 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7303, F. circinatum | KAF5675688.1 | 100.00 | |

| g108t1 | 141 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7302, F. circinatum | KAF5675687.1 | 100.00 | |

| g109t1 | 528 | Polyketide synthase FCIRC_7301, F. circinatum | KAF5675686.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g110t1 | 156 | Taurine dioxygenase family FCIRC_7300, F. circinatum | KAF5675685.1 | 100.00 | |

| g111t1 | 379 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7299, F. circinatum | KAF5675684.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g112t1 | 160 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7298, F. circinatum | KAF5675683.1 | 100.00 | |

| g113t1 | 508 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7297, F. circinatum | KAF5675682.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g114t1 | 174 | Kinase-like (PK-like), FCIRC_7296 F. circinatum | KAF5675681.1 | 100.00 | |

| g114t2 | 161 | Kinase-like (PK-like), FCIRC_7296 F. circinatum | KAF5675681.1 | 100.00 | |

| g115t1 | 198 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7295, F. circinatum | KAF5675680.1 | 81.17 | |

| g115t2 | 239 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7295, F. circinatum | KAF5675680.1 | 100.00 | |

| g116t1 | 408 | Alpha beta-hydrolase, FCIRC_7294, F. circinatum | KAF5675679.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| g117t1 | 137 | Hypothetical protein FCIRC_7293, F. circinatum | KAF5675678.1 | 100.00 | |

| g118t1 | 249 | Telomere-associated recQ-like helicase, FCIRC_7292, F. circinatum | KAF5675677.1 | 0.0 | 100.00 |

| Gene | Pfam Acc. No. | InterPro Acc. No. | Domain Name | Domain Name Abbreviation | Localization (AA) | E Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g2t1 | PF10342 | IPR018466 | Kre9/KNH-like N-terminal Ig-like domain | GPI-anchored | 29–123 | |

| g6t1 | PF00264 | IPR002227 | Tyrosinase copper-binding | Tyrosinase | 60–358 | |

| g6t2 | PF00264 | IPR002227 | Tyrosinase copper-binding | Tyrosinase | 60–359 | |

| g7t1 | PF13472 | IPR013830 | SGNH hydrolase-type esterase | Lipase_GDSL_2 | 174–343 | |

| g18t1 | PF00112 | IPR000668 | Peptidase C1A, papain C-terminal | Peptidase_C1 | 434–607 | |

| g20t1 | - | IPR003347 | Jumonji | JmjC | 339–498 | |

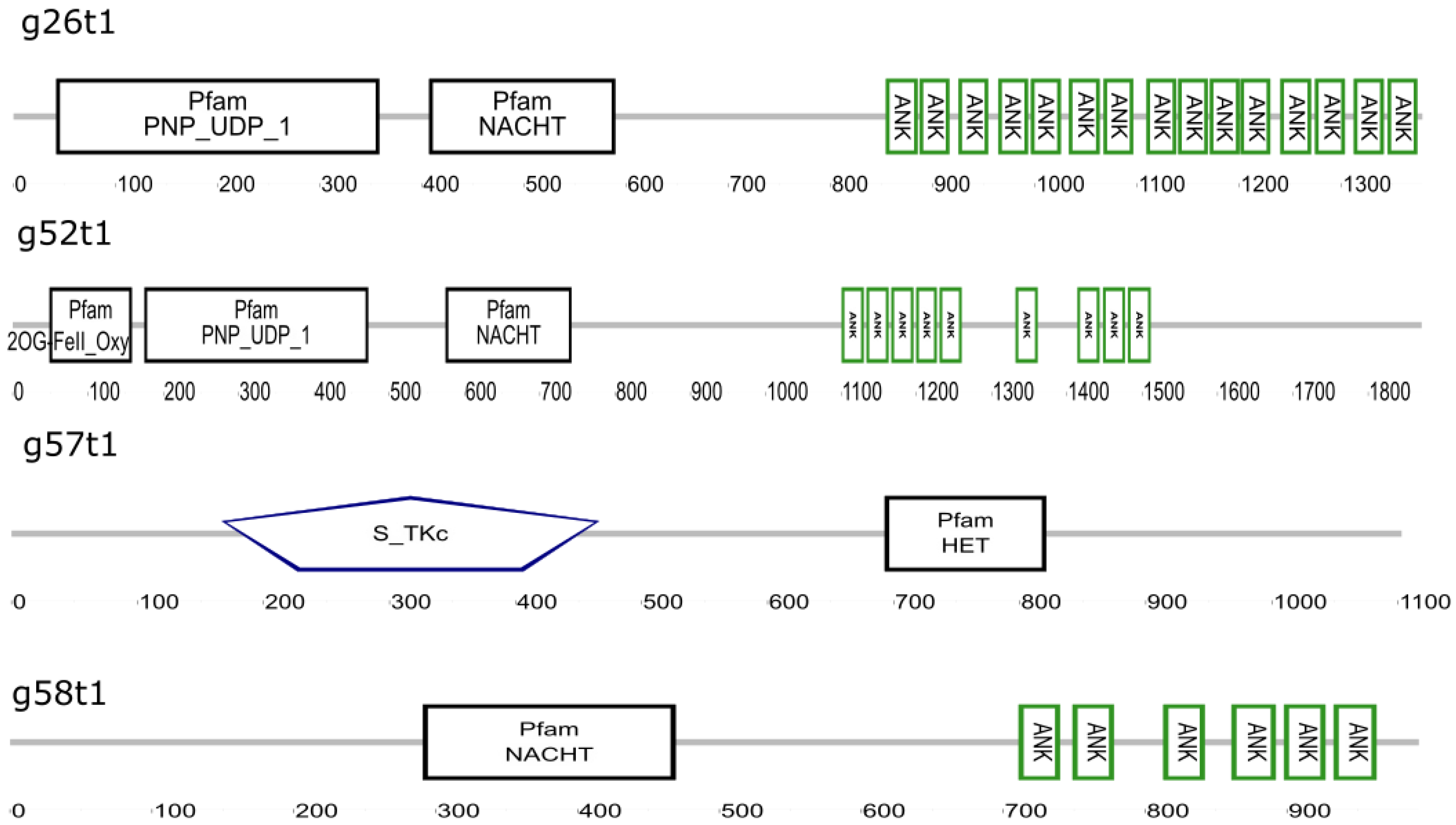

| g26t1 | PF01048 | IPR000845 | Nucleoside phosphorylase | PNP_UDP _1 | 42–358 | |

| g26t1 | PF05729 | IPR000845 | NACHT nucleoside triphosphatase | NACHT | 407–589 | |

| g26t1 | - | IPR002110 | Ankyrin repeat | ANK | 15 rpt. from 854 to 1374 | |

| g52t1 | PF03171 | IPR005123 | Oxoglutarate/iron-dependent dioxygenase | 2OG-FeII_Oxy | 49–158 | |

| g52t1 | PF01048 | IPR000845 | Nucleoside phosphorylase | PNP_UDP _1 | 175–472 | |

| g52t1 | PF05729 | IPR007111 | NACHT nucleoside triphosphatase | NACHT | 575–742 | |

| g53t1 | PF02133 | IPR001248 | Purine-cytosine permease | Transp_cyt_pur | 30–487 | |

| g54t1 | PF01177 | IPR015942 | Asp/Glu/hydantoin racemase | Asp_Glu_race | 42–219 | |

| g55t1 | PF04082 | IPR007219 | Transcription factor, fungi | Fungal_trans | 131–318 | |

| g55t1 | - | IPR001138 | Zn(2)-C6 fungal-type DNA-binding | GAL4 | 6–54 | |

| g55t2 | PF04082 | IPR007219 | Transcription factor, fungi | Fungal_trans | 130–318 | |

| g55t2 | - | IPR001138 | Zn(2)-C6 fungal-type DNA-binding | GAL4 | 6–54 | |

| g56t1 | - | IPR000719 | Protein kinase | S_TKc | 29–359 | |

| g57t1 | - | PR000719 | Protein kinase | S_TKc | 167–466 | 0.142 |

| g57t1 | PF06985 | IPR010730 | Heterokaryon incompatibility | HET | 693–821 | |

| g58t1 | PF05729 | IPR007111 | NACHT nucleoside triphosphatase | NACHT | 291–469 | |

| g58t1 | - | IPR002110 | Ankyrin repeats | ANK | 6 rpt. from 711 to 963 | |

| g58t2 | PF05729 | IPR007111 | NACHT nucleoside triphosphatase | NACHT | 291–469 | |

| g58t2 | - | IPR002110 | Ankyrin repeats | ANK | 6 rpt. from 726 to 978 | |

| p65t1 | PF00155 | IPR004839 | Aminotransferase, class I/class II | Aminotran_1_2 | 27–208 | |

| p66t1 | PF07690 | IPR011701 | Major facilitator superfamily | MSF1 | 61–459 | |

| p66t2 | PF07690 | IPR011701 | Major facilitator superfamily | MSF1 | 86–466 | |

| p67t1 | PF02826 | IPR006140 | D-isomer specific 2-hydroxyacid dehydrogenase | 2-Hacid_dh_C | 60–256 | |

| p68t1 | PF03328 | IPR005000 | HpcH/HpaI aldolase/citrate lyase | HpcH_HpaI | 37–257 | |

| g70t1 | PF02771 | IPR013786 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase/oxidase, N-terminal | Acyl-CoA_dh_N | 5–117 | |

| g70t1 | PF02770 | IPR006091 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase/oxidase, middle | Acyl-CoA_dh_M | 121–222 | |

| g70t1 | PF00441 | IPR009075 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase/oxidase, C-terminal | Acyl-CoA | 234–390 | |

| g74t1 | PF00271 | IPR001650 | Helicase, C-terminal | helicase_C | 14–116 | |

| g79t1 | - | IPR002110 | Ankyrin repeats | ANK | 9 rpt. from 275 to 275 | |

| g81t1 | PF00135 | IPR00201 | Carboxylesterase, type B | COesterase | 33–488 | |

| g81t2 | PF00135 | IPR00201 | Carboxylesterase, type B | COesterase | 33–364 | |

| g82t1 | - | IPR007219 | Transcription factor, fungi | Fungal_trans | 242–314 | |

| g89t1 | PF00656 | IPR011600 | Peptidase C14, caspase | Caspase | 40–158 | |

| g89t2 | PF00656 | IPR011600 | Peptidase C14, caspase | Caspase | 63-181 | |

| g93t1 | PF03702 | IPR005338 | Anhydro-N-acetylmuramic acid kinase | AnmK | 2–382 | |

| g94t1 | PF11991 | IPR017795 | Aromatic prenyltransferase, DMATS-type | Trp_DMAT | 1–193 | |

| g95t1 | PF00067 | IPR001128 | Cytochrome P450 | p450 | 24–182 | |

| g96t1 | PF00501 | IPR000873 | AMP-dependent synthetase/ligase | AMP-binding | 4–83 | |

| g100t1 | PF03534 | IPR003284 | Salmonella virulence plasmid protein | SpvB | 47–240 | |

| g102t1 | PF13472 | IPR013830 | SGNH hydrolase-type esterase | Lipase_GDSL_2 | 22–239 | |

| g103t1 | - | IPR001214 | SET domain | SET | 7 –155 | |

| g105t1 | PF07690 | IPR011701 | Major facilitator superfamily | MSF1 | 38–416 | |

| g109t1 | PF00109 | IPR014030 | Beta-ketoacyl synthase, N-terminal | Ketoacyl-synt | 1–76 | |

| g109t1 | PF00109 | IPR014030 | Beta-ketoacyl synthase, N-terminal | Ketoacyl-synt | 72–166 | |

| g109t1 | PF02801 | IPR014031 | Beta-ketoacyl synthase, C-terminal | Ketoacyl-synt_C | 174–274 |

| Gene | eggNOG | Description |

|---|---|---|

| g9t1 | arCOG00379 | trimeric autotransporter adhesin |

| g10t1 | 7KF05 | fibrous sheath CABYR-binding protein |

| g24t1 | BKZCK | ZnF_C2H2 |

| g27t1 | 5K2KN | sjoegren syndrome nuclear autoantigen 1 |

| g47t1 | 5J4GB | anthrone oxygenases |

| g48t1 | KOG1724 | S-phase kinase-associated protein 1 |

| g59t1 | KOG4626 | protein O-GlcNAc transferase |

| g60t1 | KOG4626 | protein O-GlcNAc transferase |

| g75t1 | KOG1546 | nicotinamide-nucleotide amidase |

| g81t1 | 7NBP8 | abhydrolase_1 alpha/beta hydrolase |

| g81t2 | 7NBP8 | abhydrolase_1 alpha/beta hydrolase |

| g101t1 | 7K74H | cupin domain |

References

- Aoki, T.; O’Donnell, K.; Geiser, D.M. Systematics of key phytopathogenic Fusarium species: Current status and future challenges. J. Gen. Plant Pathol. 2014, 80, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, R.; Van Kan, J.A.; Pretorius, Z.A.; Hammond-Kosack, K.E.; Di Pietro, A.; Spanu, P.D.; Rudd, J.J.; Dickman, M.; Kahmann, R.; Ellis, J.; et al. The Top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-García, J.; Paraschiv, M.; Flores-Pacheco, J.A.; Chira, D.; Diez, J.J.; Fernández, M. Susceptibility of several northeastern conifers to Fusarium circinatum and strategies for biocontrol. Forests 2017, 8, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, M.; Hammerbacher, A.; Ganley, R.; Steenkamp, E.; Gordon, T.; Wingfield, B.; Coutinho, T. Pitch canker caused by Fusarium circinatum—A growing threat to pine plantations and forests worldwide. Australas. Plant Pathol. 2008, 37, 319–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezos, D.; Martinez-Alvarez, P.; Fernandez, M.; Diez, J.J. Epidemiology and management of pine pitch canker disease in Europe—A review. Balt. For. 2017, 23, 279–293. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield, B.D.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Santana, Q.C.; Coetzee, M.P.; Bam, S.; Barnes, I.; Beukes, C.W.; Chan, W.Y.; Vos, L.D.; Fourie, G.; et al. First fungal genome sequence from Africa: A preliminary analysis. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2012, 108, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, L.D.; van der Nest, M.A.; van der Merwe, N.A.; Myburg, A.A.; Wingfield, M.J.; Wingfield, B.D. Genetic analysis of growth, morphology and pathogenicity in the F1 progeny of an interspecific cross between Fusarium circinatum and Fusarium subglutinans. Fungal Biol. 2011, 115, 902–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wyk, S.; Wingfield, B.D.; De Vos, L.; Santana, Q.C.; Van der Merwe, N.A.; Steenkamp, E.T. Multiple independent origins for a subtelomeric locus associated with growth rate in Fusarium circinatum. IMA Fungus 2018, 9, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Adalia, E.J.; Fernández, M.; Wingfield, B.D.; Diez, J.J. In silico annotation of five candidate genes associated with pathogenicity in Fusarium circinatum. For. Pathol. 2018, 48, e12417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phasha, M.; Wingfield, M.; Wingfield, B.; Coetzee, M.; Hallen-Adams, H.; Fru, F.; Swalarsk-Parry, B.; Yilmaz, N.; Duong, T.; Steenkamp, E. Ras2 is important for growth and pathogenicity in Fusarium circinatum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2021, 150, 103541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphosa, M.N.; Steenkamp, E.T.; Kanzi, A.M.; Van Wyk, S.; De Vos, L.; Santana, Q.C.; Duong, T.A.; Wingfield, B.D. Intra-species genomic variation in the pine pathogen Fusarium circinatum. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- der Nest, M.V.; Olson, Å.; Lind, M.; Vélëz, H.; Dalman, K.; Durling, M.B.; Karlsson, M.; Stenlid, J. Distribution and evolution of het gene homologs in the basidiomycota. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2014, 64, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanke, M.; Morgenstern, B. AUGUSTUS: A web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W465–W467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoff, K.J.; Stanke, M. WebAUGUSTUS—A web service for training AUGUSTUS and predicting genes in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, W123–W128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- InterProScan. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/search/sequence/ (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Jones, P.; Binns, D.; Chang, H.Y.; Fraser, M.; Li, W.; McAnulla, C.; McWilliam, H.; Maslen, J.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; et al. InterProScan 5: Genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 1236–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, M.; Chang, H.Y.; Chuguransky, S.; Grego, T.; Kandasaamy, S.; Mitchell, A.; Nuka, G.; Paysan-Lafosse, T.; Qureshi, M.; Raj, S.; et al. The InterPro protein families and domains database: 20 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D344–D354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Khedkar, S.; Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 49, D458–D460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Plaza, A.; Szklarczyk, D.; Botas, J.; Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Giner-Lamia, J.; Mende, D.R.; Kirsch, R.; Rattei, T.; Letunic, I.; Jensen, L.J.; et al. eggNOG 6.0: Enabling comparative genomics across 12 535 organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D389–D394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drenkhan, R.; Ganley, B.; Martín-García, J.; Vahalík, P.; Adamson, K.; Adamčíková, K.; Ahumada, R.; Blank, L.; Bragança, H.; Capretti, P.; et al. Global geographic distribution and host range of Fusarium circinatum, the causal agent of pine pitch canker. Forests 2020, 11, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Ballesteros, C.; Diez, J.J.; Martín-García, J.; Witzell, J.; Solla, A.; Ahumada, R.; Capretti, P.; Cleary, M.; Drenkhan, R.; Dvořák, M.; et al. Pine pitch canker (PPC): Pathways of pathogen spread and preventive measures. Forests 2019, 10, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vainio, E.J.; Bezos, D.; Bragança, H.; Cleary, M.; Fourie, G.; Georgieva, M.; Ghelardini, L.; Hannunen, S.; Ioos, R.; Martín-Garcí, J.; et al. Sampling and detection strategies for the pine pitch canker (PPC) disease pathogen Fusarium circinatum in Europe. Forests 2019, 10, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydenko, K.; Nowakowska, J.A.; Kaluski, T.; Gawlak, M.; Sadowska, K.; García, J.M.; Diez, J.J.; Okorski, A.; Oszako, T. A Comparative Study of the Pathogenicity of Fusarium circinatum and other Fusarium Species in Polish Provenances of P. sylvestris L. Forests 2018, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raitelaitytė, K.; Oszako, T.; Markovskaja, S.; Radzijevskaja, J.; Paulauskas, A. Fusarium circinatum research on Pinus sylvestris of different provenances and interaction with other pine-inhabiting fungi. In Proceedings of the Smart Bio: ICSB 2nd International Conference, Kaunas, Lithuania, 3–5 May 2018; Vytautas Magnus University: Kaunas, Lithuania, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Elvira-Recuenco, M.; Cacciola, S.O.; Sanz-Ros, A.V.; Garbelotto, M.; Aguayo, J.; Solla, A.; Mullett, M.; Drenkhan, T.; Oskay, F.; Kaya, A.G.A.; et al. Potential interactions between invasive Fusarium circinatum and other pine pathogens in Europe. Forests 2019, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.R.; Yan, K.; Dickman, M.B.; Leslie, J.F. Electrophoretic karyotypes distinguish the biological species of Gibberella fujikuroi (Fusarium section Liseola). MPMI-Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 1995, 8, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saupe, S.J. Molecular Genetics of Heterokaryon Incompatibility in Filamentous Ascomycetes. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puhalla, J.E.; Spieth, P.T. A comparison of heterokaryosis and vegetative incompatibility among varieties of Gibberella fujikuroi (Fusarium moniliforme). Exp. Mycol. 1985, 9, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoletti, M.; Clavé, C. The Fungus-Specific HET Domain Mediates Programmed Cell Death in Podospora anserina. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 2001–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrka, W.; Lamacchia, M.; Durrens, P.; Kobe, B.; Daskalov, A.; Paoletti, M.; Sherman, D.J.; Saupe, S.J. Diversity and Variability of NOD-Like Receptors in Fungi. Genome Biol. Evol. 2014, 6, 3137–3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saupe, S.; Turcq, B.; Bégueret, J. A gene responsible for vegetative incompatibility in the fungus Podospora anserina encodes a protein with a GTP-binding motif and Gβ homologous domain. Gene 1995, 162, 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koonin, E.V.; Aravind, L. The NACHT family–a new group of predicted NTPases implicated in apoptosis and MHC transcription activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000, 25, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, F.; Clavé, C.; Saupe, S.J. The Transcriptional Response to Nonself in the Fungus Podospora anserina. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2013, 3, 1015–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelest, E. Transcription Factors in Fungi: TFome Dynamics, Three Major Families, and Dual-Specificity TFs. Front. Genet. 2017, 8, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, P.K.; Ehrlich, K.C. Genome-wide analysis of the Zn(II)2Cys6 zinc cluster-encoding gene family in Aspergillus flavus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 4289–4300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galhano, R.; Illana, A.; Ryder, L.S.; Rodríguez-Romero, J.; Demuez, M.; Badaruddin, M.; Martinez-Rocha, A.L.; Soanes, D.M.; Studholme, D.J.; Talbot, N.J.; et al. Tpc1 is an important Zn(II)2Cys6 transcriptional regulator required for polarized growth and virulence in the rice blast fungus. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, M.; Huang, C.; Wu, X. Genome-wide characterization of the Zn(II)2Cys6 zinc cluster-encoding gene family in Pleurotus ostreatus and expression analyses of this family during developmental stages and under heat stress. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niño-Sánchez, J.; Castillo, V.C.D.; Tello, V.; Vega-Bartol, J.J.D.; Ramos, B.; Sukno, S.A.; Mínguez, J.M.D. The FTF gene family regulates virulence and expression of SIX effectors in Fusarium oxysporum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 1124–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahanty, B.; Mishra, R.; Joshi, R.K. Molecular characterization of Zn(II)2Cys6 cluster gene family and their association with pathogenicity of the onion basal rot pathogen, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cepae. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 117, 101782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Sirakova, T.; Rogers, L.; Ettinger, W.F.; Kolattukudy, P. Regulation of constitutively expressed and induced cutinase genes by different zinc finger transcription factors in Fusarium solani f. sp. pisi (nectria haematococca). J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 7905–7912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, M.J.; Murray, S.L.; Duncan, A.; Khew, G.S.; Davis, M.A. Regulatory genes controlling fatty acid catabolism and peroxisomal functions in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, A.L.M.; Pietro, A.D.; Ruiz-Roldán, C.; Roncero, M.I.G. Ctf1, a transcriptional activator of cutinase and lipase genes in Fusarium oxysporum is dispensable for virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek, A.; Strauss, J. The chromatin code of fungal secondary metabolite gene clusters. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 95, 1389–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, E.J.; Carpenter, P.B. Understanding the language of Lys36 methylation at histone H3. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connolly, L.R.; Smith, K.M.; Freitag, M. The Fusarium graminearum histone H3 K27 methyltransferase KMT6 regulates development and expression of secondary metabolite gene clusters. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1003916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janevska, S.; Baumann, L.; Sieber, C.M.; Münsterkötter, M.; Ulrich, J.; Kämper, J.; Güldener, U.; Tudzynski, B. Elucidation of the two H3K36me3 histone methyltransferases Set2 and Ash1 in Fusarium fujikuroi unravels their different chromosomal targets and a major impact of Ash1 on genome stability. Genetics 2018, 208, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Skalnik, D.G. CpG-binding protein (CXXC finger protein 1) is a component of the mammalian Set1 histone H3-Lys4 methyltransferase complex, the analogue of the yeast Set1/COMPASS complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 41725–41731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitag, M. Histone methylation by SET domain proteins in fungi. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 71, 413–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gacek-Matthews, A.; Berger, H.; Sasaki, T.; Wittstein, K.; Gruber, C.; Lewis, Z.A.; Strauss, J. KdmB, a Jumonji histone H3 demethylase, regulates genome-wide H3K4 trimethylation and is required for normal induction of secondary metabolism in Aspergillus nidulans. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.J.; Geiser, D.M.; Proctor, R.H.; Rooney, A.P.; O’Donnell, K.; Trail, F.; Gardiner, D.M.; Manners, J.M.; Kazan, K. Fusarium pathogenomics. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 67, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, P.; Fokkens, L.; Ayukawa, Y.; van der Gragt, M.; Ter Horst, A.; Brankovics, B.; Houterman, P.M.; Arie, T.; Rep, M. A mobile pathogenicity chromosome in Fusarium oxysporum for infection of multiple cucurbit species. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, C.A.; Schäfer, W.; Salomon, S. A secreted lipase of Fusarium graminearum is a virulence factor required for infection of cereals. Plant J. 2005, 42, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.N.; Bormann, J.; Le, G.T.T.; Stärkel, C.; Olsson, S.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Giese, H.; Schäfer, W. Autophagy-related lipase FgATG15 of Fusarium graminearum is important for lipid turnover and plant infection. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2011, 48, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo-Ruiz, G.; Ruiz-Roldán, C.; Roncero, M.I.G. Lipolytic system of the tomato pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici. Mol.-Plant-Microbe Interact. 2013, 26, 1054–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jashni, M.K.; Dols, I.H.M.; Iida, Y.; Boeren, S.; Beenen, H.G.; Mehrabi, R.; Collemare, J.; de Wit, P.J.G.M. Synergistic action of a metalloprotease and a serine protease from Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici cleaves chitin-binding tomato chitinases, reduces their antifungal activity, and enhances fungal virulence. Mol.-Plant-Microbe Interact. 2015, 28, 996–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Song, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Liang, W. The secreted FoAPY1 peptidase promotes Fusarium oxysporum invasion. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1040302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N. Structural advances for the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2013, 38, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergiopoulos, I.; Zwiers, L.H.; Waard, M.A.D. Secretion of Natural and Synthetic Toxic Compounds from Filamentous Fungi by Membrane Transporters of the ATP-binding Cassette and Major Facilitator Superfamily. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2002, 108, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorbo, G.D.; jan Schoonbeek, H.; Waard, M.A.D. Fungal Transporters Involved in Efflux of Natural Toxic Compounds and Fungicides. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2000, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.W.; McCormick, S.P.; Alexander, N.J.; Proctor, R.H.; Desjardins, A.E. A Genetic and Biochemical Approach to Study Trichothecene Diversity in Fusarium sporotrichioides and Fusarium graminearum. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2001, 32, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M.; Tokai, T.; O’Donnell, K.; Ward, T.J.; Fujimura, M.; Hamamoto, H.; Shibata, T.; Yamaguchi, I. The trichothecene biosynthesis gene cluster of Fusarium graminearum F15 contains a limited number of essential pathway genes and expressed non-essential genes. FEBS Lett. 2003, 539, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohn, T.M.; Krishna, R.; Proctor, R.H. Characterization of a Transcriptional Activator Controlling Trichothecene Toxin Biosynthesis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 1999, 26, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costachel, C.; Coddeville, B.; Latgé, J.P.; Fontaine, T. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored fungal polysaccharide in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 39835–39842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Herrera, J.; Ortiz-Castellanos, L. Cell wall glucans of fungi. A review. Cell Surf. 2019, 5, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.s.; Covert, S.F.; Momany, M. FsFKS1, the 1, 3-β-Glucan Synthase from the Caspofungin-Resistant Fungus Fusarium solani. Eukaryot. Cell 2006, 5, 1036–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, R.; Viljoen, A.; Myburg, A.A.; den Berg, N.V. Pathogenicity associated genes in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense race 4. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2013, 109, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, J.; Fan, F.; Zhang, D.; Wang, X. The Type 2C protein phosphatase FgPtc1p of the plant fungal pathogen Fusarium graminearum is involved in lithium toxicity and virulence. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2010, 11, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei-Bao, Z.; Ren, A.Z.; Xu, H.J.; Li, D.C. The gene fpk1, encoding a cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit homolog, is required for hyphal growth, spore germination, and plant infection in Fusarium verticillioides. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, K.; Tang, Y.; Wei, L.; Liu, E.; Liang, Z. Protein kinase Ime2 is associated with mycelial growth, conidiation, osmoregulation, and pathogenicity in Fusarium oxysporum. Arch. Microbiol. 2022, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffar, F.Y.; Imani, J.; Karlovsky, P.; Koch, A.; Kogel, K.H. Different Components of the RNA Interference Machinery Are Required for Conidiation, Ascosporogenesis, Virulence, Deoxynivalenol Production, and Fungal Inhibition by Exogenous Double-Stranded RNA in the Head Blight Pathogen Fusarium graminearum. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malewski, T.; Matić, S.; Okorski, A.; Borowik, P.; Oszako, T. Annotation of the 12th Chromosome of the Forest Pathogen Fusarium circinatum. Agronomy 2023, 13, 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030773

Malewski T, Matić S, Okorski A, Borowik P, Oszako T. Annotation of the 12th Chromosome of the Forest Pathogen Fusarium circinatum. Agronomy. 2023; 13(3):773. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030773

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalewski, Tadeusz, Slavica Matić, Adam Okorski, Piotr Borowik, and Tomasz Oszako. 2023. "Annotation of the 12th Chromosome of the Forest Pathogen Fusarium circinatum" Agronomy 13, no. 3: 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030773

APA StyleMalewski, T., Matić, S., Okorski, A., Borowik, P., & Oszako, T. (2023). Annotation of the 12th Chromosome of the Forest Pathogen Fusarium circinatum. Agronomy, 13(3), 773. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy13030773