Abstract

Nowadays, rice production faces significant challenges due to population pressure, global climate change, and outbreak of various pests and diseases. Breeding techniques used to improve rice traits include mutant breeding, cross breeding, heterogeneity, transformation, molecular markers, genome-wide association study (GWAS), and so on. Since the recently developed CRISPR/Cas9 technology can directly target a specific part of a desired gene to induce mutation, it can be used as a powerful means to expand genetic diversity of crops and develop new varieties. So far, CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been used for improving rice characteristics such as high yield, good quality, abundant nutrition, pest and disease resistance, herbicide resistance, and biotic and abiotic stress resistance. This review highlights the mechanisms and optimization of the CRISPR system and its application to rice crop, including resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses, and improved rice quality and yield.

1. Introduction

Rice is one of the most important food crops in the world. It is consumed by half of the world’s population [1]. In 2019, total rice output surpassed 755 million tons [2]. By 2050, the world’s population is projected to rise by 34% to nearly 10 billion [3]. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations has estimated that worldwide grain yields would need to rise by 70% to satisfy global demand [4]. Furthermore, climate change is also projected to increase global temperatures by 2 degrees Celsius over the next 30 years. [5]. Simiarly, soil salinity has the potential to decrease global rice output by 50% [6]. Cold stress also has the potential to diminish rice yield and quality [7]. Climate change, arable land loss, water shortages, biotic and abiotic stressors, and other factors pose new challenges to global food security, threatening crop output and causing massive losses [8]. To solve these challenges, scientists and plant breeders have been working hard to create new crop types that are not only high yielding but also resistant to abiotic and biotic stresses, including drought stress, salt stress, floods, insects, and diseases [9]. Innovative techniques and methods have emerged in the field of plant molecular breeding to increase yields, improve quality, and resist pests and diseases against the effects of adverse environmental conditions.

In the past 10 years, new techniques for site-directed mutagenesis, commonly referred to as “genome editing”, have been introduced to plant breeding programs. CRISPR/Cas9 is an effective and reliable gene-editing technique for plant breeding [10,11]. It is the most efficient and the easiest gene-editing technique to apply to plant breeding [12]. With CRISPR/Cas9 technology, DNA is cleaved by a nuclease precisely at a target site where a mutation is likely to be beneficial. The DNA is healed by the cellular repair system either through error-prone, non-homologous end joining or homologous recombination, by which small DNA fragments can be inserted at the target site [13,14]. Genome editing provides information for creating new alleles, fixing faulty alleles, and pyramiding alleles to obtain the desired phenotype by eliminating the generic drug [15].

New CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technologies have led to significant advancements in life sciences [16]. The success of plant breeding is determined by phenotypic variability and total genetic diversity across populations. Genome editing has been recently used to improve yield performance and a variety of quality-related characteristics. CRISPR/Cas9 has been shown to be effective in improving agricultural disease resistance, yield, nutrition, and domestication [17]. To develop new varieties by CRISPR/Cas9 technology, breeders should firstly identify genes that act as negative regulators in yield increase, quality improvement, abiotic stress tolerance, and biotic stress resistance, as shown in Tables 1 and 2. These genes can be applied to produce specific mutations for developing new varieties. In the near future, breeders should use the technique of homology directed repair (HDR) to facilitate their breeding strategies for specific genes of interest. In this review, the current application and future prospects are discussed.

2. CRISPR/Cas9 System and How It Works

CRISPR stands for Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats. CRISPR sequences were originally discovered as short genomic DNA sequences downstream of the alkaline isozyme phosphatase (iap) gene in E. coli [18]. They were discovered in the genomes of bacteria and archaea [19,20]. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing is based on a natural immune system defense mechanism employed by bacteria to resist invading viruses. However, it is currently recognized as part of an adaptive defensive system that includes Cas enzymes associated with CRISPR/Cas9 [21]. CRISPR/Cas9 functions were not initially linked to microbial cellular immunity until 2003 [22]. CRISPR/Cas9 systems can detect and cut complementary DNA sequences, enabling bacteria to recall and eliminate viral intruders [23,24].

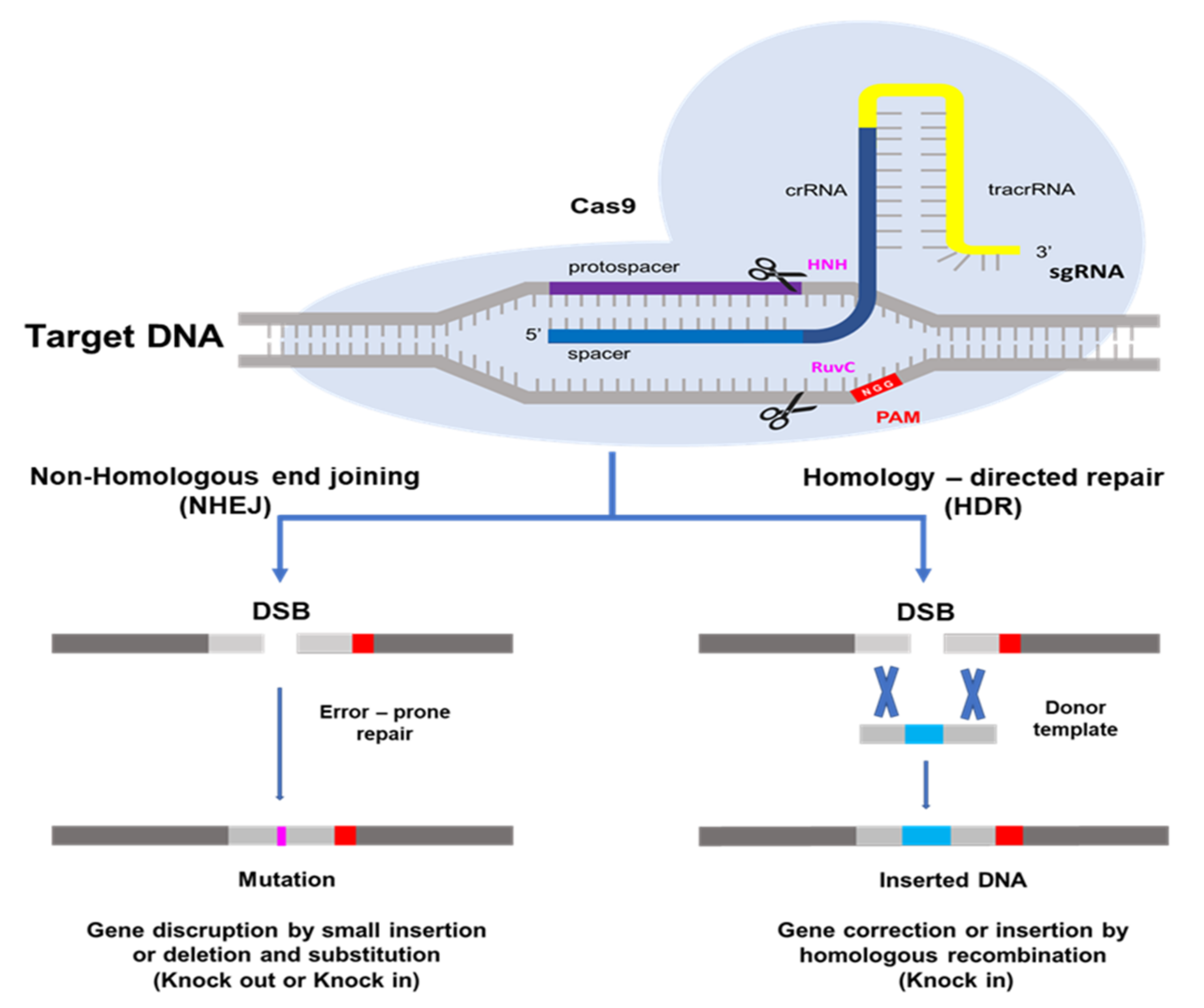

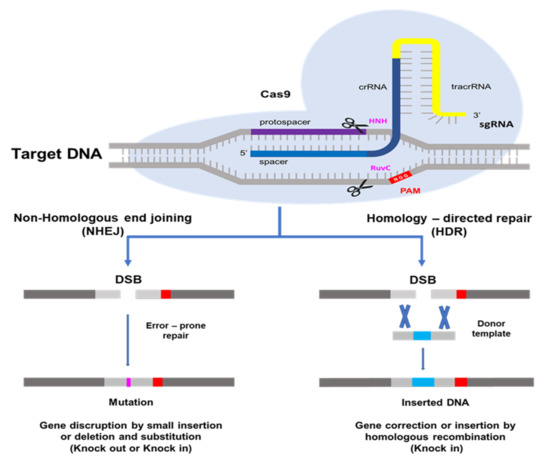

The CRISPR/Cas9 system, which is most often utilized in plant genome editing, can adapt with type II of Streptococcus pyogenes [14]. One CRISPR RNA transcript is processed to produce one or more short guide RNAs that can lead Cas9 to the target DNA sequence [13,14,25]. The Cas9 protein has DNA endonuclease activity. Cas9 attaches to the guide RNA in the cell and produces a binary complex that utilizes Watson–Crick base pairing to search the genome for the DNA target for cleavage. The guide RNA binds to the specific target gene. Cas9 also needs a proto-spacer adjacent motif (PAM) located immediately downstream of the target DNA sequence on the non-target DNA strand. PAM sequence 5′-NGG-3′ is recognized by Cas9 from S. pyogenes [14,26,27] A wide compatibility of PAM substantially increases the targeting range of plant genome editing tools based on the CRISPR/Cas9 system [28]. HNH and RuvC are two nuclease domains found in Cas9 proteins. The target DNA strand complementary to the guide RNA sequence is cleaved by the HNH-like nuclease domain and the non-target strand is cleaved by the RuvC-like nuclease domain [13,14,29]. This induces a DNA double-strand break (DSB) at the target site, which may be utilized for non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) or homology directed repair (HDR) modifications [30]. The DSB created by Cas9 is repaired using either error-prone non-homologous end-joining [31], which results in small random insertions and deletions at the cleavage site, or high-fidelity, homology-directed repair [32], which results in precise genome modification at the DSB site using a homologous repair template. Because of its ease of development, simplicity of application, and high efficiency, the CRISPR/Cas9 system has become quickly adopted as an extremely effective tool for genome modification in a broad range of species since the initial demonstration of its potential for genome engineering [13,24]. As a result, NHEJ has become a popular method for disrupting genes by introducing small base pair InDels (insertions/deletions) at specific target genes, while HDR has been used to precisely introduce point mutations and insert or replace desired large sequences into the target DNA [33] in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic picture of genome editing mediated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The Cas9 protein, which is guided by a desired single-strand guide (gRNA), cuts the double-stranded DNA and makes a double strand break (DSB). Subsequently, DNA repair occurs through either Non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) or homology directed repair (HDR) pathways (Modified from Doudna JA, Charpentier E, 2014) [34].

3. Research Trends of Major Traits

3.1. Rice Improvement via CRISPR/Cas9 System

The CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing method has been used in almost 20 crop species so far for improving various characteristics such as yield and resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses [35] (Table 1). The most direct use of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing is NHEJ-mediated gene editing. Pathogenic microorganisms can cause biotic stress, with more than 42% of potential yield loss and 15% global food production decline [36]. To increase crop productivity, host tolerance against specific infections, disease resistance to abiotic stressors such as drought and salinity, and elimination of negative regulators of grain growth may be essential. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9 offers alternative methods for delivering target genes into crops without leaving a transgenic footprint, such as viral infection, Agrobacterium infiltration, or preassembled Cas9 protein-sgRNA ribonucleoproteins’ transformation; all those activations removed the limitations of standard GMO regulations [37]. The method for developing genome editing (GE) plants that involve upstream open reading frames (uORF) mutation editing using the CRISPR/Cas9 system provides an efficient approach for producing GE crops and expanding the spectrum of use of genome editing technology [38]. As the CRISPR/Cas9 method is simple, efficient, and precise, it is anticipated to have a significant effect on plant biology and crop breeding. Compared to backcrossing in traditional breeding programs, genome editing allows major crops to be precisely changed while saving time [39]. CRISPR/Cas9 technology offers an effective way to pyramid crop breeding by allowing many characteristics to be changed simultaneously [40].

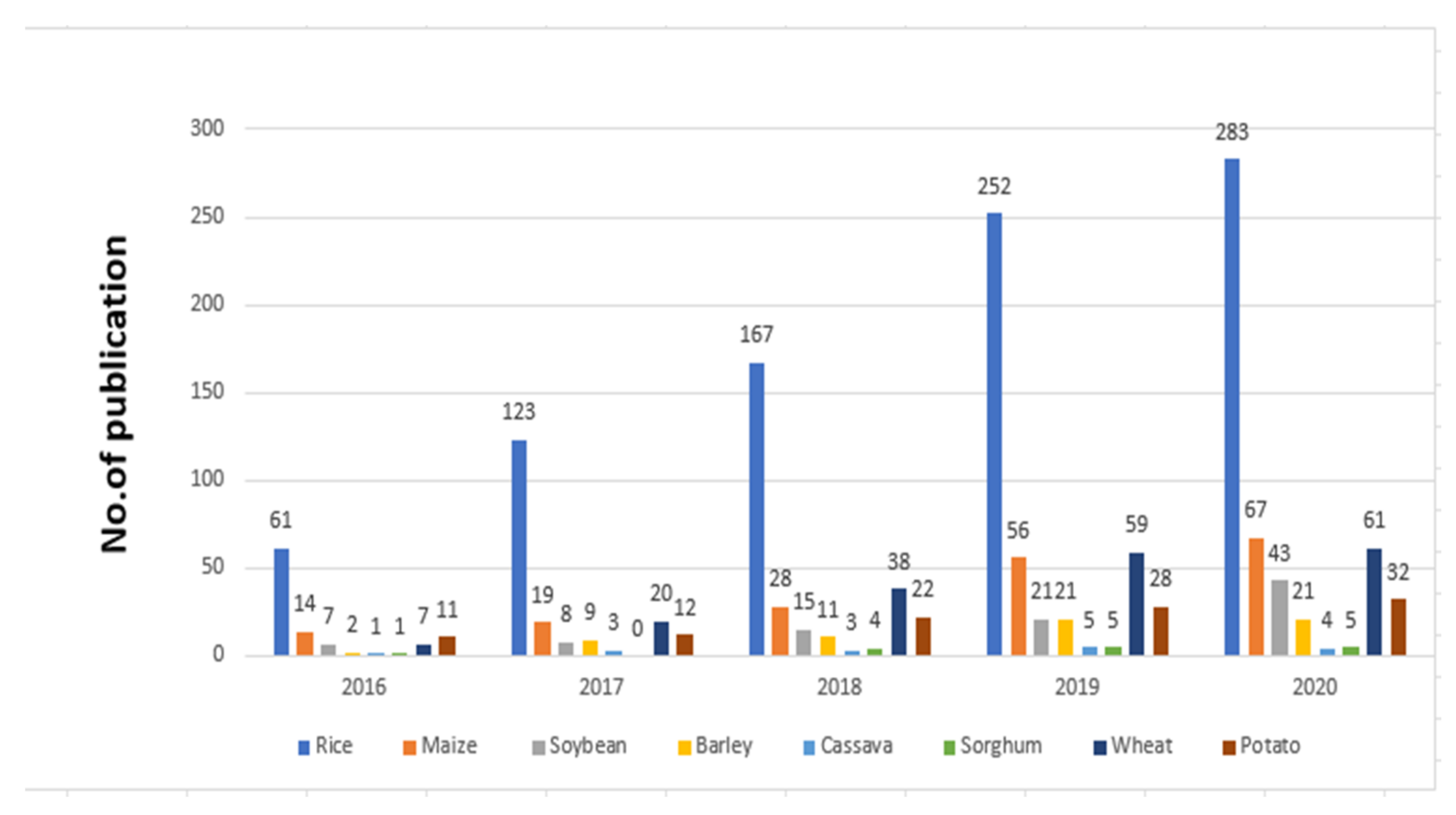

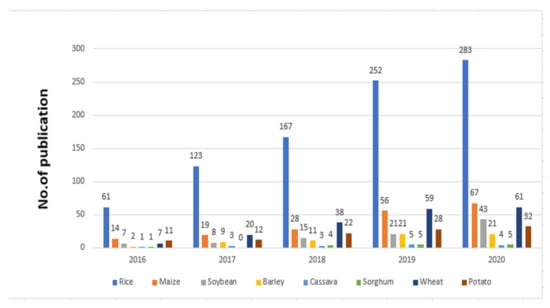

CRISPR/Cas9 has been widely applied in plants’ genome editing, with over 5000 papers published utilizing this method in the past few years. Research papers and publications using CRISPR/Cas9 for improving rice and other crops are increasing year by year. Such an increase in publications is especially high for rice in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Publications using CRISPR/Cas9 for improving rice and other crops from 2016 to 2020.

3.1.1. Grain Yield Increase

In recent years, the main goal of almost all rice breeding projects is to improve grain yield potential [41]. Rice yield is a significant and complicated agronomic characteristic affected by the number of grains per panicle, the number of panicles per plant, percent ripened grains, and the 1000 weight [42,43]. Nowadays, rice varieties using genome-editing technologies contain new genotypes of yield-associated genes. CRISPR/Cas9 system shows potential to increase grain yield [44]. Li et al. [45] modified four genes (Gn1a, DEP1, GS3, and IPA1) using the CRISPR/Cas9 system in rice cultivar Zhonghua 11. These four genes have been reported to function as regulators of plant architecture, panicle architecture, grain number, and grain size. The CRISPR/Cas9 method was highly influential in inducing targeted gene editing in the first generation of transformed plants. They found that gn1a, dep1, and gs3 mutants of T2 generations produced more grain numbers, dense erect panicles, and bigger grain size, respectively [45]. The CRISPR/Cas9 technology was then used to create homozygous Gs3 mutation lines with stable inheritance and a long-grain phenotype. Their study offers a simple and effective method for increasing grain production, which may considerably speed up the breeding strategy of long-grain japonica parents and encourage the creation of high-yielding rice [46].

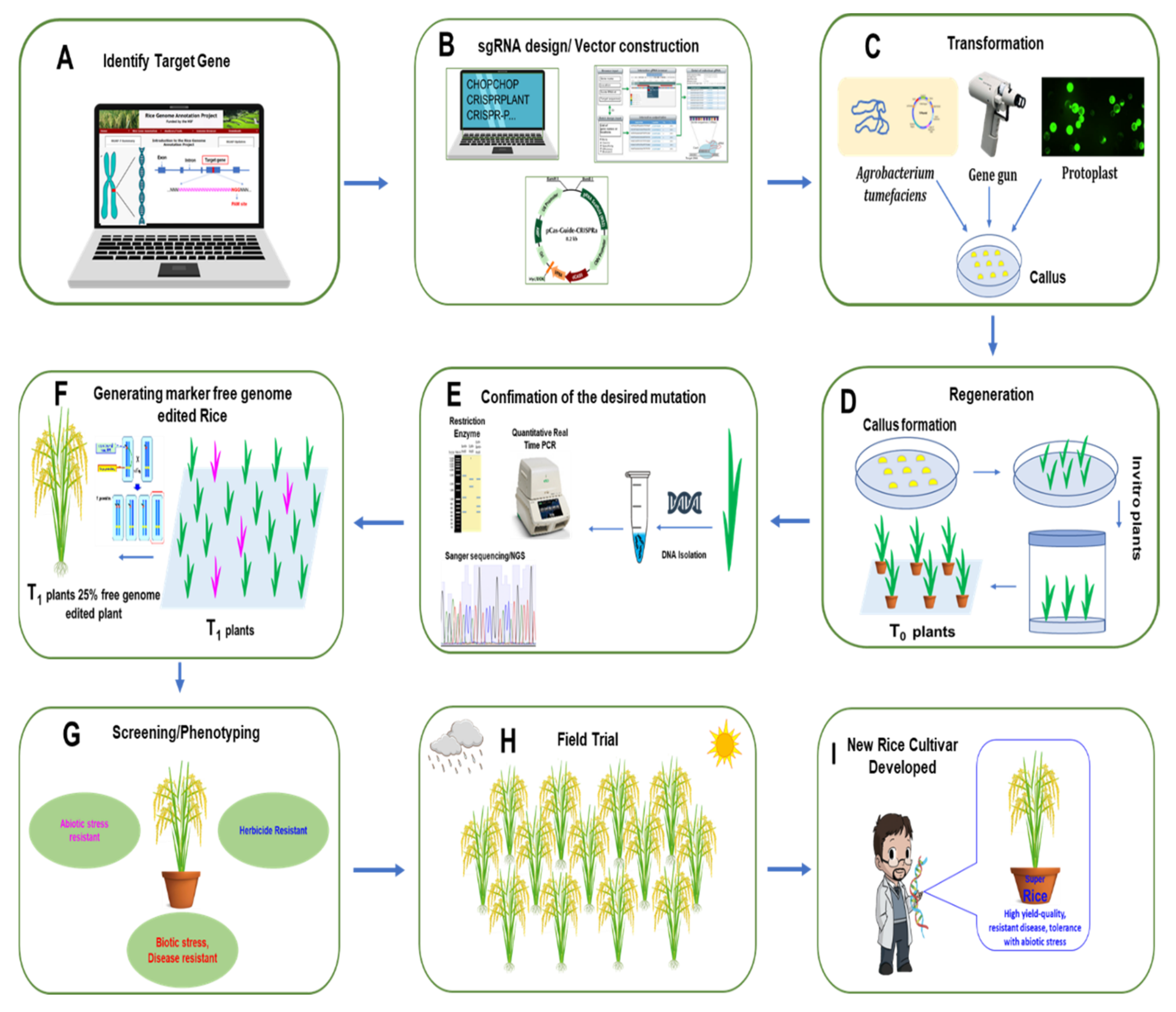

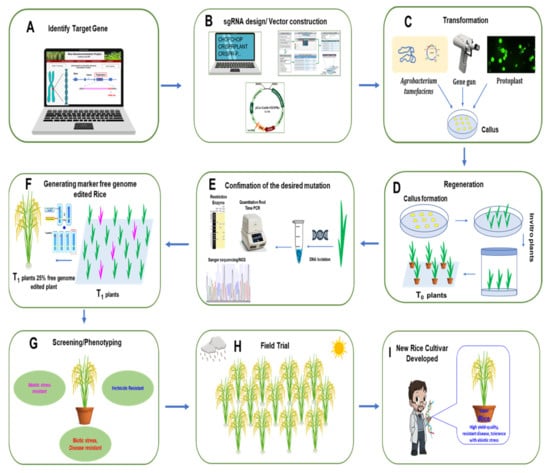

In rice, the process from choosing the target gene to field trial with elite lines using the CRISPR/Cas9 system to develop new varieties with high yield, high quality trait, disease resistance, and abiotic stress tolerance is illustrated step by step in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

General strategy for rice development using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. (A) Identify the target gene sequence in the rice genome. (B) Design the sgRNA and prepare the vector construct. (C) After confirming the correct sequence of the construct, it is transferred either by Agrobacterium, biolistic bombardment (gene gun), or protoplast method. The construct is then transformed to rice callus. (D) T0 plants are regenerated from transformed callus. (E) Regenerated plants are confirmed through PCR, restriction digestion, and sequencing. (F) In T1 generation, according to Mendelian segregation rules, 25% of plants will be gene-edited null plants. (G) Rice plants are then screened for desired characteristics. (H) Selected plants are transplanted for field trials. (I) New rice variety with high yield, high quality trait, disease resistance, and abiotic stress tolerance is then developed by genome editing scientists.

CRISPR/Cas9 has been simultaneously applied to three grain weight-related genes, thousand-grain weight 6 (TGW6), grain weight 2 (GW2), and GW5, to induce mutations, resulting in a 29.3% increase in thousand-grain weight in the triple null mutation. Compared to wild-type LH422, T2 null mutants had substantially larger grains and a higher TGW. Grain length, grain width, and TGW of the double mutants increased by 11.69%, 8.47%, and 12.68%, respectively, whereas the grain length, grain width, and TGW of the four triple mutants increased by 24.2~25.3%, 19.8~20.5%, and 27.1~29.8% [47]. Application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing for the OsGA20ox2 gene in indica rice cultivar has produced semi-dwarf mutant lines; the mutations can alter amino acid sequences of mutant plants, resulting in lower levels of gibberellins (GA) and plant height (PH), shorter flag leaf length (FLL), and higher yield per plant (YPP) [48].

Multiplex editing of QTLs using CRISPR/Cas9 offers a novel, simple, and cost-effective breeding approach. OsGS3, OsGW2, and OsGn1a genes are yield-related QTL genes in rice. Their contributions are cumulative, resulting in yield per panicle increases of 68% and 30% for triple mutants of J809 and L237, respectively [49]. Compared to wild type, multiplex gene editing of three genes (Gn1a, GW2, and GS3) also increased grain yield of rice plant [50]. The OsPAO5 mutant was created using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Compared with the wild type, pao5 mutants had longer mesocotyls, released less H2O2, and synthesized more ethylene [51].

By simultaneously performing gene editing for three cytochrome P450 homoeologs and OsBADH2 using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology, novel rice mutants with high yield and enhanced fragrance were generated. RNA sequencing and proteome analyses were conducted to reveal alterations; other agronomic characteristics were unchanged in mutants, including grain size, 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP) content, and grain cell numbers [52]. However, OsPIN5b and GS3 were modified by using the CRISPR/Cas9 method. Results showed that OsPIN5b and GS3 mutants had longer panicles and larger grains. Compared to the wild type, mutants had a higher yield in the T2 generation [53].

CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing was applied to design two target sites in the coding area of each of the eight FWL genes in rice. The phenotypic analysis shows that flag leaves, grain length, tiller number, and plant yield of OsFWL4 gene mutants are much higher than the wild type [54]. Cis-regulatory sequence mutated to alterations in gene expression and phenotypes the beneficial alleles in new rice varieties by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system which easily produced alleles with similar expression levels as shown for OsTB1 gene [55]. To increase the grain size in rice, OsSPL16/qGW8 was mutagenized through CRISPR/Cas9, and proteomic analysis was performed to reveal variations triggered by mutations [56]. CRISPR/Cas9 technology was used to modify PYL genes in rice. Only pyl1 and pyl12 showed severe seed dormancy abnormalities among the single pyl mutants. In real paddy field settings, 36.4% of pyl1 mutants showed the highest growth and grain production, while preserving virtually normal seed dormancy [57].

3.1.2. High Quality and Nutrition Fortification

Grain quality is one of the most significant characteristics directly affecting marketing and trade after harvesting [58]. The price of rice on the market is decided by its quality, which includes appearance, milling, and cooking qualities of rice grains [59]. Good cooking, sensory traits, milling, palatability, nutritional value, and physical appearance are essential factors affecting rice market price [60]. It will be beneficial to create new breeding techniques if we know how to edit genes that influence quality traits [61]. Gene modification by genome editing to enhance rice grain quality characteristics is a quick, sustainable, and cost-effective method [62].

Rice gel consistency (GC) and gelatinization temperature (GT) are known to be associated with Waxy gene [63,64]. By introducing a loss-of-function mutation into Waxy gene in two common elite japonica cultivars using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, it has been shown that mutations in Waxy gene can decrease AC (amylose content) and convert rice to glutinous types without altering other desired agronomic characteristics. The low AC in CRISPR-waxy seeds classifies them as waxy or glutinous rice, indicating that utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 to modify the Waxy gene can effectively convert two non-glutinous kinds, XS134 and 9522, into new glutinous types [65]. Another study successfully altered the Wx gene in a japonica background, resulting in lower AC; the AC was decreased in transgenic Taichung 65 rice lines carrying a Wx antisense construct. Hybrids derived from these transgenic lines exhibited lower AC [66]. Two genes, OsSBEI and OsSBEIIb, in rice were utilized to produce targeted mutagenesis using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Although there were no significant differences in phenotypes between sbeI mutants and wild type, sbeII mutants had a higher proportion of long chains in debranched amylopectin. AC and RS (resistant starch) contents reached 25.0% and 9.8%, respectively, leading to modified microstructure and nutritional properties of starch [67] (Table 1).

The advantages of CRISPR/Cas9 technology and its efficiency can be applied as the most dependable and efficient way for new rice breeding [68]. The CRISPR/Cas9 system has been employed to modify the ISA1 gene in rice using Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. It was found that amounts of total starch, amylose, and amylopectin in cr-isa1 mutants’ endosperm were substantially decreased, while sugar content and starch gel consistency were noticeably enhanced compared to the wild-type. Furthermore, cr-isa1 mutants showed significantly reduced transcript levels for most starch synthesis-related genes. These results indicate that ISA1 gene edition can influence starch synthesis and endosperm formation, which has significant implications for rice quality development [69]. The CRISPR/Cas9 technique has also been utilized to generate new OsBADH2 alleles, resulting in the introduction of fragrance into an elite non-aromatic rice variety, ASD16. Sequence analysis of aromatic T0 lines revealed 22 distinct mutations ranging from −17 bp to +15 bp in the sgRNA region. The intense fragrance was generated by the −1/−2 bp deletion in lines # 8~19 and the −8/−5 bp deletion in lines # 2~16. This trait was stably inherited in the T1 generation [70].

Oleic acid is an essential component of rice bran oil. Increasing oleic acid concentration in rice bran oil could benefit health and improve disease prevention. In plants, fatty acid desaturase 2 (FAD2) can convert oleic acid to linoleic acid. Four FAD2 genes, namely, OsFAD2-1, OsFAD2-2, OsFAD2-3, and OsFAD2-4, were discovered in the rice genome. The OsFAD2-1 gene is the most highly expressed one [71]. The OsFAD2-1 gene was disrupted using CRISPR/Cas9 technology. Abe and his colleagues successfully produced homozygous OsFAD2-1 knockout rice plants. Oleic acid concentrations in these OsFAD2-1 knockout rice plants were increased more than two-fold than those in the wild type, whereas concentrations of linoleic acid, a catabolite of oleic acid by FAD2, dropped significantly to undetectable levels in fad2-1 mutant brown rice seeds [72]. A multiplex sgRNA-CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system was used to modify the FAD2 gene in rice; the results showed that the multiplex sgRNA-CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system could be used for crop improvement through gene editing of monocot species [73].

Genes related to improved eating and cooking quality (OsAAP6, OsAAP10), slender grain shape, less chalkiness (OsGS9), grain with low Cd accumulation (OsNramp5), increased β-carotene (OsOr, SSU-crtI, ZmPsy) were also tried to examine their functional analysis by gene editing using CRISPR/Cas9 technique [74,75,76,77,78].

Table 1.

Application of CRISPR/Cas9 system to increase yield, nutrition quality, and other agronomic traits in rice.

Table 1.

Application of CRISPR/Cas9 system to increase yield, nutrition quality, and other agronomic traits in rice.

| Target Gene | Gene ID | Cas9 Promoter | sgRNA Promoter | Method of Delivery | Mutation Type | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OsIPA1 | LOC_Os08g39890 | p35S, ZmUBI | OsU6, OsU3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Enhanced grain number, Grain yield. | [45] |

| OsGn1a | LOC_Os09g31310 | ||||||

| OsGS3 | LOC_Os12g34380 | 35S pro Pubi | U6a, U6b | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain size | [46] |

| OsGW2, OsGW6 | LOC_Os02g14720 LOC_Os06g15620 | pUBQ | OsU3, OsU6, TaU3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain yield, grain size | [47] |

| OsGA20ox2 | LOC_Os01g66100 | Pubi-H | OsU6a, OsU6b | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain yield, plant architecture | [48] |

| OsGW2 | LOC_Os02g14720 | p35S | OsU6, OsU3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain yield, grain size, grain weight | [49] |

| OsPAO5 | LOC_Os04g57560 | CaMV 35S | U6 | Rice protoplasts | NHEJ | Increase grain weight, grain number | [51] |

| OsBADH2 | LOC_Os08g32870 | 35S/ubi | U3m, U6a | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain yield, grain size, aromatic | [52] |

| OsPIN5b OsMYB30 | LOC_Os08g41720 LOC_Os02g41510 | 2 × 35S pro Pubi-H | OsU6a | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain yield, grain size Cold tolerance | [53] |

| OsFWL4 | LOC_Os03g61440 | Maize Ubi1 | OsU6 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain yield, plant architecture | [54] |

| OsTB1/ OsFC1 | LOC_Os03g49880 | 2 × 35S pro CaMV | gRNA1,2,3 gRNA4,5,6 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Plant architecture, number of tillers | [55] |

| OsSPL16/ qGW8 | LOC_Os08g41940 | 2 × 35S pro Pubi | OsU6a | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain yield, grain weight, grain size | [56] |

| OsPYL1, OsPYL12 | LOC_Os10g42280 LOC_Os02g15620 | Maize Ubi1 | OsU6, OsU3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Number of grains, grain yield | [57] |

| OsWaxy | LOC_Os06g04200 | CaMV 35S | U6 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Decrease amylose content | [65] |

| OsBEI, | LOC_Os06g51084 | pCXUN | OsU3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | High amylose content | [67] |

| OsISA1 | LOC_Os08g40930 | CaMV 35S | OsU6 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Reduced amylose content | [69] |

| OsBADH2 | LOC_Os08g32870 | OsUbi | OsU6a | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Enhanced fragrance | [70] |

| OsFAD2-1/ OsFAD2 | LOC_Os02g48560 | pZH 2 × 35S | U3 and U6 OsU6a, OsU6b | Agrobacterium-mediated Rice protoplast | NHEJ | High oleic/low linoleic | [72] [73] |

| OsAAP6, OsAAP10 | LOC_Os01g65670 LOC_Os02g49060 | CaMV35S | OsU3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Improved eating and cooking quality | [74] |

| OsGS9 | LOC_Os09g27590 | OsUb | OsU6a | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Slender grain shape, less chalkiness | [75] |

| OsNramp5 | LOC_Os07g15370 | ZmUBI | OsU6a | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Grain low Cd accumulation | [76] |

| OsOr | LOC_Os02g43500 | 2 × 35S | OsU6-2 | Rice Protoplast | NHEJ | Increased β-carotene | [77] |

| SSU-crtI, ZmPsy | - | Ubi1 | OsU6 | Gene gun | NHEJ | Increased β-carotene | [78] |

| OsALS | LOC_Os02g30630 | ZmUBI | U3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | HDR | Herbicide resistance | [79] |

| OsAOX1a, OsAOX1b, OsAOX1c | LOC_Os04g51150 | - | OsU3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Fertility, Male sterility | [80] |

| OsEPSPS | LOC_Os06g04280 | - | OsU3 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ, HDR | Glyphosate resistance, high grain yield | [81] |

| OsHd2 | LOC_Os06g16370 | 35S | U3, U6a, U6c | Protoplast | NHEJ | Rice early maturing | [82] |

| OsHd4, OsHd5 | - | - | - | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Rice early maturing | [83] |

| OsCIPK3 | LOC_Os07g48760 | CaMV 35S | LacZa | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Long day flowering | [84] |

| OsMYB1 | LOC_Os05g35500 | CaMV 35S | OsU6-2 | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Seed maturation | [85] |

| OsHAK-1 | LOC_Os04g32920 | - | - | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Low cesium accumulation | [86] |

| OsPRX2 | LOC_Os02g33450 | CaMV 35S | OsU3t | Agrobacterium-mediated | NHEJ | Potassium deficiency tolerance | [87] |

3.1.3. Developing Rice Variety with Herbicide Tolerance

In over 130 nations, herbicides such as Basta and glyphosate (N-phosphono-methylglycine) are used to destroy weeds [88]. Ideal herbicides must kill only weeds, not crop plants. Increasing herbicide resistance in rice genome using CRISPR/Cas9 has shown popularity in recent years [79]. Using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, transgenic rice plants containing sgRNA:Cas9 have been produced by A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation after combining sgRNA and Cas9 cassette in a binary vector. Alterations were discovered by examining the targeted location on the genomes of matching transgenic plants. The effectiveness of mutagenesis ranged from 2% to 16%. Furthermore, the biallelic mutant transgenic plant was sensitive to bentazon according to phenotypic analyses [80] (Table 1). The previous study reported that the CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to develop effective intron-mediated, site-specific gene replacement and insertion methods that could produce mutations through the NHEJ pathway. Targeted gene insertions were accomplished at a frequency of 2.2% utilizing a sgRNA targeting one intron and a donor DNA template with the same sgRNA position. Glyphosate resistance was found with anticipation in rice plants carrying the OsEPSPS gene [81,89]. Site-specific gene substitutions and insertions were also reliably inherited by the following generation [90].

3.1.4. Male Sterile Lines for Hybrid Breeding

Hybrid rice breeding is a valuable technique for increasing rice yields. The development of a sterile male line is critical to cross-breeding success. Using the CRISPR/Cas9 system, a group of researchers in China created 10 target sites in the coding region of TMS5 for targeted mutagenesis, the most widely used thermo-sensitive genic male sterility (TGMS) gene, and developed new “transgene clean” TGMS lines; within a year, both rice subspecies produced 11 new “transgene clean” TGMS lines with high potential application in hybrid breeding [91]. One of the essential stages in two-line hybrid rice breeding is developing photoperiod-sensitive genic male sterility (PGMS) lines. Such lines were traditionally vetted and produced using a traditional rice breeding method in both long-day and short-day environments. This isolation and backcross procedure may potentially take more than 3 years to complete, with a shallow success rate. However, CRISPR/Cas9 technology provides a simple way to create Carbon-starved anther (csa)-based PGMS rice lines [92] (Table 1).

For commercial rice breeding, developing nuclear-sterile lines for two-line hybrid breeding is important. Researchers from China developed the pC1300-2 × 35S::sgRNA expression vector using CRISPR/Cas9 technology to edit the male fertility gene PTGMS2-1 in 93-11 and Huazhan, the two most commonly compatible rice varieties. According to results of phytotron tests with four temperature and photoperiod treatments, the most significant factor in restoring pollen fertility in ptgms2-1 mutants in the 93-11 and Huazhan rice varieties is temperature, while photoperiod has some impacts on pollen fertility in these two rice backgrounds. Using a genome editing method to develop new male-sterile lines will substantially speed up the rice breeding process [93].

3.1.5. Rice Early Maturing and Long Day Flowering

The flowering time of rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the most significant agronomic variables for area adaptation and grain output. Breeders would want to have a more efficient and somewhat modulated blooming period of an elite cultivar in the rice breeding process. Four homozygous lines were modified to boost the expression of flowering repressors using the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technique by modifying Hd2 uORFs. A high-efficiency breeding technique for manipulating rice heading date was created using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing, which saves time and labor compared to conventional breeding [82,83]. The CRISPR/Cas9 technique was used to identify OsCIPK3. A mutation in OsCIPK3 causes a late heading date under LDs but a normal heading date under short-day circumstances. According to the results, OsCIPK3 phosphorylates OsFD1 to enhance the development of RFT1-containing florigen activation complexes and, as a consequence, flowering in rice under long-day conditions [84].

Genes related to seed maturation (OsMYB1), low cesium accumulation (OsHAK-1), and potassium deficiency tolerance (OsPRX2) were also tried to examine their functional analysis by NHEJ of gene editing using CRISPR/Cas9 technique [85,86,87].

3.1.6. Abiotic Stress Resistance

Salinity Tolerance

Salt is a significant environmental stressor that may have an adverse effect on rice development and production. Recent research has indicated that members of AP2/ERF domain containing RAV (related to ABI3/VP1) TF family might play a role in abiotic stress adaption [94]. Under a salt stress condition, expression patterns of all five OsRAVs were analyzed. By treating cells with high salinity, just one gene, OsRAV2, was stably activated. The regulatory role of the GT-1 element in OsRAV2 salt induction has been shown in situ in plants utilizing targeted mutations produced using the CRISPR/Cas9 technology (Table 1). These results suggest that the GT-1 element exerts direct control over OsRAV2′s salt response. This research contributes to a better understanding of OsRAVs’ potential activities and the molecular regulatory mechanisms governing plant gene expression in response to salt stress [95]. In a previous study, salt tolerance of rice was improved by introducing a Cas9-OsRR22-sgRNA expressing vector targeting the rice OsRR22 gene. Mutant plants lacking transfer DNA (T-DNA) were generated via segregation in T1 progeny. Specifically, findings revealed that salt tolerance of T2 homozygous mutant lines was substantially increased compared to that of wild-type plants when grown to seedling stage. Additionally, no significant differences in agronomic characteristics among T2 heterozygous mutant lines and wild-type plants were observed. These findings in the T2 generation suggest that CRISPR/Cas9 might be an effective tool for increasing rice salt [96] (Table 2).

Drought Tolerance

Drought tolerance is a multi-gene trait that shows multiple genotypes through environment interaction [97,98]. Drought stress can reduce the photosynthetic rate, limiting plant growth and yield loss, ranging from 13% to 94% [99]. The study by scientists from Japan demonstrated that the role of OsERA1 in rice plants may be functionally characterized utilizing the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing method. Rice osera1 mutant lines with CRISPR/Cas9-induced frameshift mutations in OsERA1 revealed comparable leaf growth to wild-type (WT) plants. These mutant lines showed improved main root development compared to WT; through stomatal regulation, these osera1 mutant lines also had better sensitivity to ABA and drought stress. These results indicate that OsERA1 in rice can serve as a negative regulator of primary root development in non-stressed circumstances as well as a negative regulator of ABA and drought stress responses [100].

Ossapk2 mutants showed an ABA-insensitive phenotype during the germination and post-germination phases, suggesting that OsSAPK2 might play a crucial role in ABA-mediated seed dormancy. This mutant was more susceptible to drought stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS) than wild-type plants, indicating that OsSAPK2 might be essential for rice drought responses [101] (Table 2).

Santosh Kumar and colleagues used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to generate mutant alleles of drought and salt tolerance (DST) genes in indica mega rice cultivar MTU1010. Their results revealed that downregulation of stomatal developmental genes SPCH1, MUTE, and ICE1 contributed to the decrease in stomatal density in DST loss-of-function mutants. In the seedling stage, a Cas9-free dstD184–305 mutant showed moderate resistance to osmotic stress and high tolerance to salt stress. As a result, DST mutant alleles developed in their research will be helpful for increasing drought and salt tolerance of indica rice cultivars as well as grain production [102]. Under stressful circumstances, the OsmiR535 gene is activated relative to controls. Researchers have confirmed that inhibiting or knocking down OsmiR535 in rice can improve plant tolerance to NaCl, ABA, dehydration, and PEG stressors using transgenic and CRISPR/Cas9 knockout system methods. Furthermore, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing resulted in a homozygous 5 bp deletion in OsmiR535′s coding sequence, indicating that OsmiR535 might be a viable genetic editing target for drought and salinity tolerance [103].

OsPYL9 was mutagenized in rice using CRISPR/Cas9 to better understand the function of one of the ABA receptors. The OsPYL9 mutants demonstrated an increase in grain output under both drought and well-watering conditions. Overall, the findings demonstrated that OsPYL9 mutants created by CRISPR/Cas9 have the potential to increase rice drought tolerance and production [104]. CRISPR/Cas9-based mutagenesis of the Semi-rolled leaf1,2 (SRL1 and SRL2) genes resulted in rolled leaf mutant plants. When compared to their wild-type counterparts, the mutant plants had reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) levels but greater survival rates under drought stress. The mutant restorer hybrids had a semi-rolled leaf phenotype with enhanced panicle number, grain number per panicle, and yield per plant, according to the researchers. This research expands to our understanding of the rice drought tolerance protein network by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system [105].

Cold Tolerance

Low temperature is an important abiotic stress that negatively affects morphological development and yield production in rice. At the seedling stage, cold stress causes low germination, poor growth, and damage to seedlings. Cold stress can also reduce grain yield in the reproductive stage [106,107]. The rice annexin gene OsAnn3 was knocked down by using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Consequently, the cold tolerance characteristic of T1 mutant lines generated from T0 biallelic mutants was found after a 3-day cold treatment at 4 °C. The relative electrical conductivity (REC) of T1 mutant lines increased after they were exposed to cold treatment. However, their survival ratio decreased substantially compared to the wild type. As a result, OsAnn3 was thought to have a function in rice cold tolerance [108] (Table 2). It was found that ospin5b, gs3, and osmyb30 mutants showed increased panicle length, enlarged grain size, and cold tolerance. These yield-related traits and cold tolerance of nine ospin5b/gs3 transgenic lines, six ospin5b/osmyb30 transgenic lines, and six gs3/osmyb30 transgenic lines were then matched to genes changed. Additionally, eight triple mutants were created by simultaneously editing all three genes. The remaining six mutants showed off-target events at the putative off-target site of OsMYB30-site1. According to these results, T2 generations of these two mutants showed higher yield and cold tolerance than those of the wild type [53].

Heat Stress Tolerance

Global warming has become a serious threat to crop productivity worldwide [109]. Heat stress (HS) from a rapidly warming climate has become a serious threat to global food security [110]. A heat-shock (HS) inducible mutant was created using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. The effectiveness of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in targeted mutagenesis was evaluated using a soybean heat-shock protein gene and rice U3 promoter to produce Cas9 and sgRNA, respectively. The existence of targeted mutations was evaluated before and after HS treatment at two loci in rice. Before HS, there was only a small number of targeted mutagenesis (16%). After HS, the rate of mutagenesis among transgenic lines increased significantly (50–63%). Targeted mutagenesis was repressed in plants but increased by HS, which was visible by Sanger sequencing after a few weeks of HS treatments according to the analysis of regenerated plants containing HS-CRISPR/Cas9 plants. These HS-induced mutations were passed down to the offspring at a high rate, resulting in monoallelic and biallelic mutations that segregated from the Cas9 gene separately. Furthermore, when HS-CRISPR/Cas9 lines were compared to constitutive overexpression CRISPR/Cas9 lines, off-target mutations were either undetectable or detected at a reduced rate [111] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Application of CRISPR/Cas9 system to increase abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in rice.

Table 2.

Application of CRISPR/Cas9 system to increase abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in rice.

| Target Gene | Gene ID | Cas9 Promoter | sgRNA Promoter | Method of Delivery | Mutation Type | Functional | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OsRAV2 | LOC_Os01g04800 | CaMV 35S | U6 | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Salt induction | [95] |

| OsRR22 | LOC_Os06g08440 | CaMV35S (2 × 35S) | OsU6a | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Salinity tolerance | [96] |

| OsERA1 | LOC_Os01g53600 | - | - | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Drought tolerance | [100] |

| OsSAPK2 | LOC_Os07g42940 | Pubi-H | U3 | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Reduced salinity, Drought tolerance | [101] |

| OsDST | LOC_Os03g57240 | OsUBQ | OsU3 | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Salinity tolerance, osmotic tolerance | [102] |

| OsmiR535 (OsSPL7) | LOC_Os04g46580 | UBI 35S-P | OsU3, OsU6 | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Drought tolerance | [103] |

| OsPYL9 | LOC_Os06g33690 | PubiH | OsU6a, OsU6b | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Drought tolerance, Grain yield | [104] |

| OsSRL1, OsSRL2 | LOC_Os01g54390 | Pubi-H | U6a, U6b, U6c, U3m | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Improved drought tolerance | [105] |

| OsAnn3 | LOC_Os07g46550 | CaMV 35S | U3 | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Cold stress tolerance | [108] |

| OsPDS | LOC_Os03g08570 | 35S-P | U3 | Gene gun | NHEJ | Heat shock resistant | [111] |

| OsSub1 | LOC_Os01g17160.1 | CaMV 35S | OsU6 | Agrobacterium mediated | NHEJ | Submergence tolerance | [112] |

| OsERF922 | LOC_Os01g54890 | 2 × 35S pro Pubi-H | OsU6a | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Rice blast resistance | [113] |

| OsALB1, OsRSY1 | - | TrpC, TEF1 | SNR52, U6-1, U6-2 | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Rice blast resistance | [114] |

| OsPi21 | LOC_Os04g32850 | PubiH | OsU6a, OsU3 | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Rice blast resistance | [115] |

| OsSEC3A | LOC_Os03g427500 | OsU3 | OsU3 | Rice Protoplast | NHEJ | Rice blast resistance | [116] |

| OsMPK5, MPK2,MPK5, MPK6 | LOC_Os06g06090 | UBI | OsU3 | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Disease resistance | [117] |

| OsSWEET14 | LOC_Os08g42350 | 35S, Ubi | U3, U6a | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Resistance to Bacterial leaf blight | [118] |

| OsSWEET11, OsSWEET13, OsSWEET14 | LOC_Os11g31190 | CaMV 35S | U6 | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Resistance to Bacterial leaf blight | [119] |

| Os8N3 | LOC_Os08g42350 | 35S-p | OsU6a | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Resistance to Bacterial leaf blight | [120] |

| OseIF4G | - | ZmUBI1, CaMV35S | TaU6 | Agrobacterium -mediated | NHEJ | Rice tungro virus resistant | [121] |

Submergence Tolerance

Most coastal rice-growing areas in the tropics and subtropics are submerged, particularly low-lying deltas along Southeast Asia’s coasts, such as Vietnam’s Mekong delta and Red River delta, Myanmar’s Ayeyerwaddy delta, and Bangladesh’s Ganges–Brahmaputra delta. These deltas account for 34% to 70% of total rice output in these nations. Any decrease in rice production due to increased flooding frequency will have severe impacts on food security [122]. With CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing of the SUBMERGENCE 1A-1 gene of the variety Ciherang-Sub1, techniques for Agrobacterium-mediated and biolistic transformation and regeneration of indica rice have been improved. The approaches pave the path for improving Indica-resistant rice varieties quickly by using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing [112].

3.1.7. Biotic Stress: Disease Resistance

Disease control requires a thorough understanding of resistance mechanisms and the development of resistant cultivars [123]. Recent results on pathogen associated to biomolecular analysis in rice blast disease are discussed. Pyramiding several R genes and other methods such as host-induced gene silencing, cross-species transformation, and gene editing might be useful for creating broad-spectrum resistant varieties [124].

Rice blast (Magnaporthe oryzae) disease is one of the most infectious diseases that affect rice worldwide, resulting in losses of 10–30% of the global yield of rice [125]. Rice blast resistance can be enhanced by developing a CRISPR/Cas9 SSN (C-ERF922) targeting the OsERF922 gene in rice, according to recent research (Table 1). Out of 50 T0 transgenic plants, 21 C-ERF922-induced mutant plants (42.0%) were found. These plants have different insertion or deletion (InDel) mutations at the target location based on Sanger sequencing; at both seedling and tillering phases, the number of blast lesions produced after pathogen infection was substantially reduced in all six mutant lines compared to wild-type plants [113]. These results indicate that gene modification through CRISPR/Cas9 is a viable method for enhancing blast resistance in rice. There were more reports on disease resistance genes such as OsALB1, OsRSY1, OsPi21, OsSEC3A, and OsMPK5, MPK2,MPK5, MPK6, which have been applied to examine their functional analysis by gene editing using CRISPR/Cas9 technique [114,115,116,117].

In Southeast Asia and West Africa, Xanthomonas oryzae PV. oryzae (Xoo) causes bacterial blight of rice, a severe rice disease; OsSWEET14 gene has been reported to be a critical bacterial blight susceptibility gene targeted by four distinct transcription activator-like (TAL) effectors from Asian or African Xoo strains [126]. In the Kitaake context, however, OsSWEET14 single-deletion or promoter mutants are weakly resistant or even vulnerable to African Xoo strains. CRISPR/Cas9 was used in another research to impair the function of OsSWEET14 by altering its equivalent coding sequence in rice Zhonghua 11. It was found that plant height was increased without decreasing yield when OsSWEET14 was disrupted [118]. In a recent study, researchers used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to change sequences in all three SWEET gene promoters (SWEET11, SWEET13, and SWEET14). Sequence analysis of TALe (transcription-activator-like effectors) genes in 63 Xoo strains revealed numerous TALe variations for SWEET13 alleles, which aided gene editing. SWEET14, which is similarly targeted by two TALes from an African Xoo lineage, has been mutated. Kitaake, IR64, and Ciherang-Sub1 rice varieties were all given five promoter mutations simultaneously. Paddy trials revealed that these rice lines with genome-edited SWEET promoters have broad-spectrum and robust resistance [119]. In addition, the CRISPR/Cas9 technology was used to delete rice gene Os8N3 to improve Xoo resistance. These mutations were transmitted to the next generations and genotyped. Rice plants in T0, T1, T2, and T3 generations were edited; the result showed that the homozygous mutants had significantly enhanced resistance to Xoo. The T1 generation demonstrated stable CRISPR/Cas9-mediated Os8N3 gene editing transmission without the transferred DNA [120].

Rice tungro disease (RTD) is a major stumbling block to rice production in tropical regions. RTD is caused by the interaction of rice tungro spherical virus (RTSV) with rice tungro bacilliform virus [127]. To develop new sources of RTD resistance, mutations in eIF4G were created using the CRISPR/Cas9 method in an RTSV-susceptible cultivar IR64. The mutation rates varied from 36.0~86.6%. These mutations were passed down effectively to subsequent generations. The Cas9 sequence was no longer present in the final products with RTSV resistance and it increased yield under glasshouse conditions. As a result, RTSV-resistant plants with new eIF4G alleles are valuable resources for developing more varied RTSV-resistant cultivars [121].

3.1.8. Biotic Stress: Insect Resistance

Globally, about 52% of rice production is lost due to biological and environmental factors, of which about 21% is caused by pests [128,129] (Table 1). Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) is a Gram-positive soil bacterium that can produce a variety of insecticidal protein toxins with narrow specificity to a variety of insects. These toxins, called crystal (Cry) and cytolytic (Cyt) proteins, can accumulate in crystalline inclusions within the bacteria. Vegetative insecticidal proteins, or VIPs, are another class of toxins from this bacterium. They are expressed during bacterial growth [130,131].

Marker-free transgenic plants in rice were generated through Agrobacterium-mediated transformation with expression of the cry2AX1 gene driven by green tissue-specific promoter rbcS. Such transgenic plants showed moderate levels of resistance against rice leaf folder (C. medinalis) and rice yellow stem borer (S. incerulas) [132]. Knockdown of two aminopeptidase N genes, APN1 and APN2, by RNAi in rice plants resulted in decreased susceptibility to C. suppressalis larvae [133]. In a study using S. exigua, CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to generate a knockout homozygous mutant (Seα6-KO) of the α-6 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAchR) in which 1760 bp was deleted. Seα6-KO showed 373-fold higher resistance to spinosad and 850-fold higher resistance to spinetoram compared to WH-S with the same genetic background. As a result of genetic analysis, this mutant was found to be inherited as an incomplete recessive trait [134,135]. To determine the causal relationship between ABCA2 genes (HaBCA2) and Cry2Ab resistance in H. armigera, two HaABCA2 knockout mutants were generated as sensitive SCD strains through the CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing system. Both knockout mutants were identified with a 2 bp or 5 bp deletion in the exon site, respectively. They were found to have high levels of resistance to Cry2Aa (>120-fold) and Cry2Ab (>100-fold), whereas they had no or very limited resistance to Cry1Ac (<4-fold) [136].

3.2. Rice Improvement by Homology-Directed Repair (HDR)

In rice, efficient HDR is critical for accurate genome editing. Despite the fact that CRISPR/Cas9 has emerged as a potential genome-editing tool in rice, NHEJ remains the favored method for DSB repair over HDR. The difficulty in supplying enough repair templates and the template’s limited-duration stability inside the cell are the two main reasons behind this. Because of these challenges, random insertion/deletion (InDels) is typically done at specific sites [66,91] However, NHEJ is prone to frequent mutation mistakes as a result of nucleotide deletions and insertions (InDels). HDR is a technology that requires donor DNA with high homology to replace key SNPs or specific regions in genomic DNA and has not yet been generalized in higher plants [137,138].

Delivering a donor repair template (DRT) into a plant for HDR-mediated DSB repair is difficult. In rice, many efforts to enhance HDR-mediated genome editing have focused on the template for repair. A geminivirus-based donor template delivery system was created in rice, with a gene knock-in frequency of 19.4% [139]. The acetolactate synthase (OsALS) gene was substituted with a mutant form containing two particular mutations, and stable rice lines were recently produced [80]. Herbicides target the ALS enzyme. Mutations in OsALS at specific locations can give herbicide tolerance. An additional approach was recently made to enhance HDR by fusing Cas9 with Agrobacterium VirD2. The Cas9-VirD2 chimeric protein performs two functions. Cas9 creates DSBs, while VirD2 relaxase brings the DRT closer to the DSB site. The DRT’s proximity to the target site makes HDR possible. This newly discovered Cas9-VirD2 method was utilized to precisely modify the OsALS allele in rice plants to make them herbicide tolerant [140]. Using a sgRNA targeting one intron and a donor DNA template with the exact sgRNA location, Li and Colleagues successfully produced targeted EPSPS gene insertions at a frequency of 2.2% [91] (See Table 1). This HDR technology has to be developed to the extent that it can be applied precisely. It is thought that it will be applied to crop breeding as a technology that can develop varieties with new functions by modifying promoters and ORFs of numerous agriculturally important genes in the near future.

4. Challenge and Future Prospects

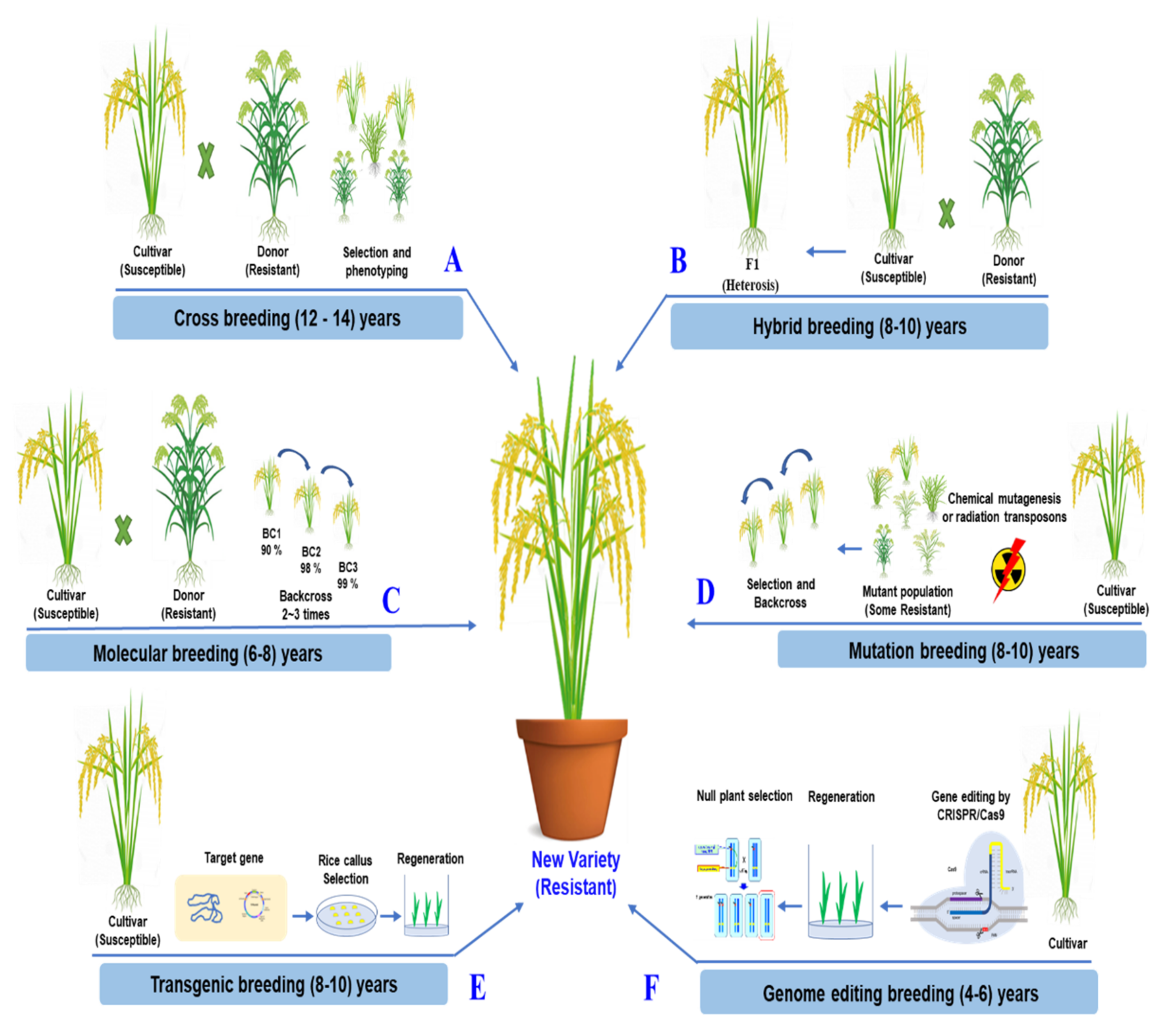

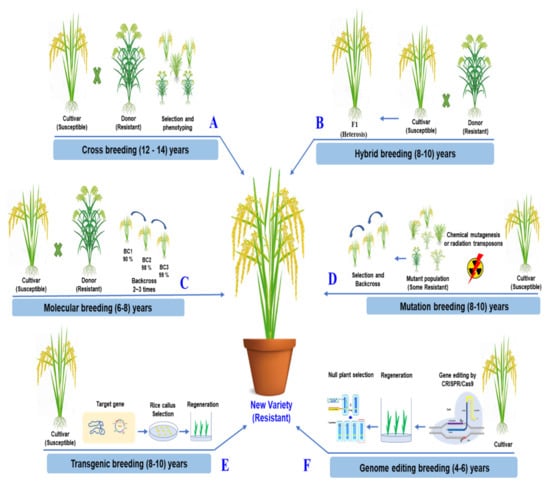

The simplicity and effectiveness of CRISPR/Cas9 over other genome editing methods are its most significant benefits. The ability to concurrently edit several target genes with the CRISPR/Cas9 system is a significant benefit [141,142]. In a two-step experimental method, Zsögön targeted six genes and produced mutations in four of them. CRISPR/Cas9 may also introduce multiplex off-target mutations into the genome [143] However, novel CRISPR/Cas variants that recognize various PAMs have increased the editing effectiveness of target bases in the sequence of interest [144]. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing can improve a characteristic by accurately altering and rapidly rearranging chromosomes in one of the best breeding strategies. It takes less time than traditional breeding methods [145]. The comparisons of traditional breeding and the modern breeding methods for rice improvement are described in detail, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the traditional breeding and the modern breeding methods for rice improvement. (A) Crossbreeding based on naturally occurring mutations has introduced various traits into elite recipient lines selected by phenotype, free of transgene. (B) Through hybrid breeding, two genetically different parent lines are produced. The heterosis effect is maintained for only one generation, free of transgene. (C) Through molecular breeding, various traits are introduced into elite lines, followed by backcrossing, selectinon by phenotype, and molecular marker, free of transgene. (D) Throught mutation breeding, radiation and chemical mutagenesis is used to induce random mutations genome-wide. It greatly expands genetic variations. It requires backcrossing. It is free of transgene. (E) Transgenic breeding introduces genes or traits from other organisms. Foreign DNA is randomly integrated into the rice genome (GMO). (F) Genome editing breeding technologies can modify plant genomes to improve traits without integrating foreign DNA into the genome. The genome is mutated by NHEJ and HDR pathways, free of transgenes. They are precise techniques for future plant breeding.

Even though CRISPR/Cas9 is a very effective and vast application, there are still some limitations that hamper improving crops. First of all, breeders should set up the efficient transformation system for CRISPR/Cas9-Target gene vector to develop enough transgenic plants and to confirm the gene-edited plants. This application should be set up well for each target plant species. The success of creating the gene-edited plants may depend on this step. Off-target mutations are DNA changes made by a deceptive gRNA, a gRNA-independent method, or non-specific sites [146]. There is a lot of concern about off-target activity or mutations that happen at places other than the intended target site. This could make the genome unstable and change the function of normal genes, Numerous ways exist for precisely modifying the gene evolved by blocking NHEJ or boosting HDR, including genetic manipulation, synchronized expression, and overlapping homology arm [143]. Off-target mutations are often tolerable in plants and mutants, and they may be discovered and eradicated by segregation over subsequent crossing [147]. Some bioinformatics tools, such as Cas-OFFinder and CCTop, have been developed to detect off-targets as well as some systems, such as SELEX, IDLV capture, Guide-seq, and Digenome-seq [148]. In comparison to the NHEJ pathway, HDR has a lower efficiency. Another limitation is that some countries are not ready to commercialize genome editing crops [68]. With the increase of gene-editing tools, there exists a need to carefully consider the modern definition of GMOs and the corresponding regulatory frameworks with them [149].

An overall picture of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing applications in plants has been provided by El-Mounadi [150]. It introduces the user to the mechanism of Cas9 activity, methods of delivering to plant cells (i.e., transformation techniques), examples of enhancing crop traits using CRISPR/Cas9, and biosafety and regulatory aspects of genome editing. Many countries formally declare that crops will not be regulated under biosafety legislation if the product of the genome-edited crops do not contain foreign DNA [151]. Several countries including Brazil, Argentina, Japan, and the United States have already exempted genome-edited crops from being regulated in the same way as genetically modified organisms (GMOs) [152].

CRISPR/Cas9 enables the generation of non-GMO mutant plants, an approach that has been widely applied in diverse genomic architectures to study its function as well as its resistance to biotic and abiotic challenges and suitable agronomic and other essential agronomic characteristics, matching with current biosafety regulations for GMO plants. Overall, this method makes it easier to analyze functions of various genes and enhance genetics of the essential species. Because of these benefits, experts working on rice genetic improvement across the globe favor this CRISPR/Cas9 technology [153].

As implications for breeders, to develop new varieties with genes expressing important agronomical traits by CRISPR/Cas9 technology, breeders first identify genes that act as factors in yield increase, quality improvement, abiotic stress tolerance, and biotic stress resistance. They can apply these genes to create specific mutations to develop new varieties. In the near future, breeders should apply homology-directed repair (HDR) techniques to facilitate breeding strategies for specific genes of interest for breeding new varieties.

5. Conclusions

The majority of crop enhancements have relied on targeted editing, which includes repair of DSBs through NHEJ and rarely whole gene modification (HDR). To increase the efficiency of gene editing for many agronomically important genes, improvements in techniques for providing exact target genes and increasing the efficiency of the HDR route for specific target genes are required. Breeders may also try to modify cis-elements in the promoter region to change the expression of specific genes of agronomic importance. Genome-edited plants are being approved in many countries as crops that could be branded as non-GMO with foreign-DNA-free methods because there is no technological difference in genetic changes between plants generated by genome editing and plants produced through traditional breeding. In the future, molecular design breeding in crops using genome editing technologies with NHEJ and HDR to increase yield, disease or insect resistance, nutritional value, and other traits will be a significant focus.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and writing the article, V.T.L. and M.-S.K.; Review and editing, Y.-J.J. and K.-K.K.; Supervision, idea development, and editing, Y.-G.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant (PJ01483602) from the Rural Development Administration and the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry Education (2021R1I1A4A01057295) Republic of Korea. It was conducted during the research year of Chungbuk National University in 2019, Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this study to disclose.

References

- Gross, B.L.; Zhao, Z. Archaeological and genetic insights into the origins of domesticated rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 6190–6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- FAO Statistics. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/world-population-prospects-2017.html (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Hunter, M.C.; Smith, R.G.; Schipanski, M.E.; Atwood, L.W.; Mortensen, D.A. Agriculture in 2050: Recalibrating Targets for Sustainable Intensification. BioScience 2017, 67, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastin, J.F.; Clark, E.; Elliott, T.; Hart, S.; van den Hoogen, J.; Hordijk, I.; Ma, H.; Majumder, S.; Manoli, G.; Maschler, J.; et al. Correction: Understanding climate change from a global analysis of city analogues. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0224120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D.K.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Foley, J.A. Yield Trends Are Insufficient to Double Global Crop Production by 2050. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66428. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, N.L.; Che Lah, W.A.; Abd Kadir, N.; Mustaqim, M.; Rahmat, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Lam, S.D.; Ismail, M.R. Susceptibility and tolerance of rice crop to salt threat: Physiological and metabolic inspections. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godfray, H.C.; Beddington, J.R.; Crute, I.R.; Haddad, L.; Lawrence, D.; Muir, J.F.; Pretty, J.; Robinson, S.; Thomas, S.M.; Toulmin, C. Food security: The challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 2010, 327, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingali, P.L. Green revolution: Impacts, limits, and the path ahead. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12302–12308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.; Ran, F.A.; Cox, D.; Lin, S.; Barretto, R.; Habib, N.; Hsu, P.D.; Wu, X.; Jiang, W.; Marraffini, L.A.; et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 2013, 339, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolter, F.; Schindele, P.; Puchta, H. Plant breeding at the speed of light: The power of CRISPR/Cas to generate directed genetic diversity at multiple sites. BMC Plant. Biol. 2019, 19, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.; Zheng, W.; Joshi, R.K.; Kaijun, Z. Genome Editing Strategies Towards Enhancement of Rice Disease Resistance. Rice Sci. 2021, 28, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinek, M.; Chylinski, K.; Fonfara, I.; Hauer, M.; Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 2012, 337, 816–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Doudna, J.A. CRISPR/Cas9 Structures and Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2017, 46, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, R.R.; Sakhale, S.; Yadav, S.; Sandhu, N.; Hassan, L.; Hossain, M.A.; Kumar, A. Molecular Breeding for Improving Drought Tolerance in Rice: Recent Progress and Future Perspectives. Mol. Breed. Rice Abiotic Stress Toler. Nutr. Qual. 2021, 2, 5374. [Google Scholar]

- Anzalone, A.V.; Koblan, L.W.; Liu, D.R. Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, C.; Capistrano-Gossmann, G.; Braatz, J.; Sashidhar, N.; Melzer, S. Recent developments in genome editing and applications in plant breeding. Plant. Breed. 2018, 137, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shino, Y.; Shinagawa, H.; Makino, K.; Amemura, M.; Nakata, A. Nucleotide sequence of the iap gene, responsible for alkaline phosphatase isozyme conversion in Escherichia coli, and identification of the gene product. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 5429–5433. [Google Scholar]

- Mojica, F.J.; Díez-Villaseñor, C.; Soria, E.; Juez, G. Biological significance of a family of regularly spaced repeats in the genomes of Archaea, Bacteria and mitochondria. Mol. Microbiol. 2000, 36, 244–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grissa, I.; Vergnaud, G.; Pourcel, C. CRISPRFinder: A web tool to identify clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats. Nucleic Acids Researc. 2007, 35, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyaval, P.; Moineau, S.; Romero, D.; Horvath, P. Against Viruses in Prokaryotes. Science 2007, 315, 1709–1712. [Google Scholar]

- Mojica, F.J.M.; Díez-Villaseñor, C.; García-Martínez, J.; Soria, E. Intervening sequences of regularly spaced prokaryotic repeats derive from foreign genetic elements. J. Mol. Evol. 2005, 60, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurtle-Schmidt, D.M.; Lo, T.W. Molecular biology at the cutting edge: A review on CRISPR/CAS9 gene editing for undergraduates. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Educ. 2018, 46, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.D.; Lander, E.S.; Zhang, F. Development and Applications of CRISPR/Cas9 for Genome Engineering. Cell 2014, 157, 1262–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, P.; Barrangou, R. CRISPR/Cas, the immune system of bacteria and archaea. Science 2010, 327, 167–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lander, E.S. The Heroes of CRISPR. Cell 2016, 164, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anders, C.; Niewoehner, O.; Duerst, A.; Jinek, M. Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature 2014, 513, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Kuang, Y.; Ren, B.; Yan, D.; Yan, F.; Spetz, C.; Sun, W.; Wang, G.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, H. SpRY greatly expands the genome editing scope in rice with highly flexible PAM recognition. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Cox, D.; Yan, W.X.; Manteiga, J.C.; Schneider, M.W.; Yamano, T.; Nishimasu, H.; Nureki, O.; Crosetto, N.; Zhang, F. Engineered Cpf1 variants with altered PAM specificities. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symington, L.S.; Gautier, J. Double-strand break end resection and repair pathway choice. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2011, 45, 247–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieber, M.R. The Mechanism of DSB Repair by the NHEJ. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2011, 79, 181–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- San Filippo, J.; Sung, P.; Klein, H. Mechanism of eukaryotic homologous recombination. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2018, 77, 229–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Liang, Z.; Zhang, K.; Liu, J.; Xi, J.J.; Qiu, J.L.; et al. Targeted genome modification of crop plants using a CRISPR-Cas system. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doudna, J.A.; Charpentier, E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science 2014, 346, 1258096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricroch, A.; Clairand, P.; Harwood, W. Use of CRISPR systems in plant genome editing: Toward new opportunities in agriculture. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2017, 1, 169–182. [Google Scholar]

- Oerke, E.C. Crop Losses to Pests. J. Agric. Sci. 2006, 144, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.W.; Kim, J.; Kwon, S.I.; Corvalán, C.; Cho, S.W.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, S.T.; Choe, S.; Kim, J.S. DNA-free genome editing in plants with preassembled CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoproteins. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 1162–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Um, T.; Park, T.; Shim, J.S.; Kim, Y.S.; Lee, G.S.; Choi, I.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Seo, J.S.; Park, S.C. Application of Upstream Open Reading Frames (uORFs) Editing for the Development of Stress-Tolerant Crops. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, M. High-Throughput Silencing Using the CRISPR/Cas9 System: A Review of the Benefits and Challenges. J. Biomol. Screen. 2015, 20, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortesi, L.; Fischer, R. The CRISPR/Cas9 system for plant genome editing and beyond. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, M.; Dar, Z.; Dar, S. Breeding Strategies for Improving Rice Yield—A Review. Agric. Sci. 2015, 6, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Kang, H.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Lim, S.; Gauch, H.G.; Eun, M.Y.; Mccouch, S. Identification of Quantitative Trait Loci in Rice for Yield, Yield Components, and Agronomic Traits across Years and Locations. Crop. Sci. 2007, 47, 2403–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, Q. Genetic and molecular bases of rice yield. Annu. Rev. Plant. Biol. 2010, 61, 421–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Q.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Gao, C. Genome editing in rice and wheat using the CRISPR/Cas system. Nat. Protoc. 2014, 9, 2395–2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, P.; Fang, M.; Pan, X.; Lin, Q.; Luo, W.; Wu, G.; Li, H. Reassessment of the Four Yield-related Genes Gn1a, DEP1, GS3, and IPA1 in Rice Using a CRISPR/Cas9 System. Front. Plant. Sci. 2016, 7, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usman, B.; Zhao, N.; Nawaz, G.; Qin, B.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. CRISPR/Cas9 Guided Mutagenesis of Grain Size 3 Confers Increased Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Grain Length by Regulating Cysteine Proteinase Inhibitor and Ubiquitin-Related Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yang, Y.; Qin, R.; Li, H.; Qiu, C.; Li, L.; Wei, P.; Yang, J. Rapid improvement of grain weight via highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplex genome editing in rice. J. Genet. Genom. = Yi Chuan Xue Bao 2016, 43, 529–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Teng, K.; Nawaz, G.; Feng, X.; Usman, B.; Wang, X.; Luo, L.; Zhao, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Generation of semi-dwarf rice (Oryza sativa L.) lines by CRISPR/Cas9-directed mutagenesis of OsGA20ox2 and proteomic analysis of unveiled changes caused by mutations. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Xin, X.; He, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhong, Z.; Deng, K.; Zheng, X.; Akher, S.A.; et al. Multiplex QTL editing of grain-related genes improves yield in elite rice varieties. Plant. Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacchini, E.; Kiegle, E.; Castellani, M.; Adam, H.; Jouannic, S.; Gregis, V.; Kater, M.M. CRISPR-mediated accelerated domestication of African rice landraces. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0229782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Shao, G.; Jiao, G.; Sheng, Z.; Xie, L.; Hu, S.; Tang, S.; Wei, X.; Hu, P. Targeted mutagenesis of POLYAMINE OXIDASE 5 that negatively regulates mesocotyl elongation enables the generation of direct-seeding rice with improved grain yield. Mol. Plant. 2021, 14, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, B.; Nawaz, G.; Zhao, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Generation of High Yielding and Fragrant Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Lines by CRISPR/Cas9 Targeted Mutagenesis of Three Homoeologs of Cytochrome P450 Gene Family and OsBADH2 and Transcriptome and Proteome Profiling of Revealed Changes Triggered by Mutations. Plants 2020, 9, 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wen, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Q.; Huang, W. Rational Improvement of Rice Yield and Cold Tolerance by Editing the Three Genes OsPIN5b, GS3, and OsMYB30 With the CRISPR/Cas9 System. Front. Plant. Sci. 2020, 10, 1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, G.; Sun, H.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Ji, J.; Wang, D.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, X. Targeted Mutagenesis of the Rice FW 2.2-Like Gene Family Using the CRISPR/Cas9 System Reveals OsFWL4 as a Regulator of Tiller Number and Plant Yield in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Hu, X.; Liang, G.; Feng, A.; Wang, F.; Ruan, S.; Dong, G.; Shen, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, D.; et al. Production of novel beneficial alleles of a rice yield-related QTL by CRISPR/Cas9. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1987–1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, B.; Nawaz, G.; Zhao, N.; Liao, S.; Qin, B.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Programmed Editing of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) OsSPL16 Gene Using CRISPR/Cas9 Improves Grain Yield by Modulating the Expression of Pyruvate Enzymes and Cell Cycle Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, C.; Xiao, L.; Hua, K.; Zou, C.; Zhao, Y.; Bressan, R.A.; Zhu, J.K. Mutations in a subfamily of abscisic acid receptor genes promote rice growth and productivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6058–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, R.P.; Fitzgerald, M.A. Genetic Diversity of Rice Grain Quality. Genet. Divers. Plants 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, M.C.; Cuevas, R.P.; Ynion, J.; Laborte, A.G.; Velasco, M.L.; Demont, M. Rice quality: How is it defined by consumers, industry, food scientists, and geneticists? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 92, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Xia, D.; He, Y. Rice grain quality—Traditional traits for high quality rice and health-plus substances. Mol. Breed. 2019, 40, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N.; Khanna, R. Rice Grain Quality: Current Developments and Future Prospects. In Recent Advances in Grain Crops Research; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Fiaz, S.; Ahmad, S.; Noor, M.A.; Wang, X.; Younas, A.; Riaz, A.; Riaz, A.; Ali, F. Applications of the CRISPR/Cas9 System for Rice Grain Quality Improvement: Perspectives and Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Cai, X.; Tang, S.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Hong, M.; Gu, M. Stable inheritance of the antisense Waxy gene in transgenic rice with reduced amylose level and improved quality. Transgenic Res. 2003, 12, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Qian, Q.; Liu, Q.; Yan, M.; Liu, X.; Yan, C.; Liu, G.; Gao, Z.; Tang, S.; Zeng, D.; et al. Allelic diversities in rice starch biosynthesis lead to a diverse array of rice eating and cooking qualities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 21760–21765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Botella, J.R.; Zhu, J.K. Generation of new glutinous rice by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the Waxy gene in elite rice varieties. J. Integr. Plant. Biol. 2018, 60, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, W.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, R.; Wang, B.; Yang, Z.; Li, H.; Lin, Y.; et al. A Robust CRISPR/Cas9 System for Convenient, High-Efficiency Multiplex Genome Editing in Monocot and Dicot Plants. Mol. Plant. 2015, 8, 1274–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Jiao, G.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Guo, X.; Du, W.; Du, J.; Francis, F.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Generation of High-Amylose Rice through CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Targeted Mutagenesis of Starch Branching Enzymes. Front. Plant. Sci. 2017, 8, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabassum, J.; Ahmad, S.; Hussain, B.; Mawia, A.M.; Zeb, A.; Ju, L. Applications and Potential of Genome-Editing Systems in Rice Improvement: Current and Future Perspectives. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, S.; Cai, Y.; Feng, B.; Jiao, G.; Sheng, Z.; Luo, J.; Tang, S.; Wang, J.; Hu, P.; Wei, X. Editing of Rice Isoamylase Gene ISA1 Provides Insights into Its Function in Starch Formation. Rice Sci. 2019, 26, 77–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ashokkumar, S.; Jaganathan, D.; Ramanathan, V.; Rahman, H.; Palaniswamy, R.; Kambale, R.; Muthurajan, R. Creation of novel alleles of fragrance gene OsBADH2 in rice through CRISPR/Cas9 mediated gene editing. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaplin, E.S.; Liu, Q.; Li, Z.; Butardo, V.M.; Blanchard, C.L.; Rahman, S. Production of high oleic rice grains by suppressing the expression of the OsFAD2-1 gene. Funct. Plant. Biol. 2013, 40, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, K.; Araki, E.; Suzuki, Y.; Toki, S.; Saika, H. Production of high oleic/low linoleic rice by genome editing. Plant. Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 131, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahariah, B.; Masani, M.; Rasid, O.A.; Parveez, G. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of the FAD2 gene in rice: A model genome editing system for oil palm. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2021, 19, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhong, C.; Yan, C.; Sun, S. Targeted mutagenesis of amino acid transporter genes for rice quality improvement using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Crop. J. 2020, 8, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.S.; Li, Q.F.; Zhang, C.Q.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Q.Q.; Pan, L.X.; Ren, X.Y.; Lu, J.; Gu, M.H.; Liu, Q.Q. GS9 acts as a transcriptional activator to regulate rice grain shape and appearance quality. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Songmei, L.; Jie, J.; Yang, L.; Jun, M.; Shouling, X.; Yuanyuan, T.; Youfa, L.; Qingyao, S.; Jianzhong, H. Characterization and Evaluation of OsLCT1 and OsNramp5 Mutants Generated Through CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Mutagenesis for Breeding Low Cd Rice. Rice Sci. 2019, 26, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, A.; Saika, H.; Takemura, M.; Misawa, N.; Toki, S. A novel approach to carotenoid accumulation in rice callus by mimicking the cauliflower Orange mutation via genome editing. Rice 2019, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, O.X.; Yu, S.; Jain, R.; Zhang, N.; Duong, P.Q.; Butler, C.; Li, Y.; Lipzen, A.; Martin, J.A.; Barry, K.W.; et al. Marker-free carotenoid-enriched rice generated through targeted gene insertion using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; He, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hou, H.; Guo, X.; Du, W.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, L. Engineering Herbicide-Resistant Rice Plants through CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Homologous Recombination of Acetolactate Synthase. Mol. Plant. 2016, 9, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.F.; Li, H.; Qin, R.Y.; Li, J.; Qiu, C.H.; Yang, Y.C.; Ma, H.; Li, L.; Wei, P.C.; Yang, J.B. Generation of inheritable and “transgene clean” targeted genome-modified rice in later generations using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, K.; Reddy, G.M.; Singh, J.; Vani, K.; Vijayalakshmi, M.; Kaul, T.; Reddy, M.K. Development of Transgenic Rice Harbouring Mutated Rice 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate 3-Phosphate Synthase (Os-mEPSPS) and Allium sativum Leaf Agglutinin (ASAL) Genes Conferring Tolerance to Herbicides and Sap-Sucking Insects. Plant. Mol. Biol. Report. 2014, 32, 1146–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; He, M.; Li, R.; Meng, W.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Bu, Q. Fine-tuning Flowering Time via Genome Editing of Upstream Open Reading Frames of Heading Date 2 in Rice. Rice 2021, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, W.; Ren, Y.; Tian, X.; Lv, T.; Wang, Z.; Fang, J.; Chu, C.; Yang, J.; Bu, Q. High-efficiency breeding of early-maturing rice cultivars via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing. J. Genet. Genom. 2017, 44, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Zhu, C.; Liu, T.; Zhang, S.; Feng, S.; Wu, C. Phosphorylation of OsFD1 by OsCIPK3 promotes the formation of RFT1-containing florigen activation complex for long-day flowering in rice. Mol. Plant. 2021, 14, 1135–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, N.; Zhang, B.; Gou, F.; Zhu, J.K. Application of the CRISPR-Cas system for efficient genome engineering in plants. Mol. Plant. 2013, 6, 2008–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieves-Cordones, M.; Mohamed, S.; Tanoi, K.; Kobayashi, N.I.; Takagi, K.; Vernet, A.; Guiderdoni, E.; Périn, C.; Sentenac, H.; Véry, A.A. Production of low-Cs+ rice plants by inactivation of the K+ transporter OsHAK1 with the CRISPR-Cas system. Plant. J. Cell Mol. Biol. 2017, 92, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, K.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, Q.; Chen, L.; Xie, H.; Zhang, J. OsPRX2 contributes to stomatal closure and improves potassium deficiency tolerance in rice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, K. The Development of Herbicide Resistance Crop Plants Using CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Editing. Genes 2021, 12, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.X.; Lin, C.; Shen, Z. Development of Transgenic Glyphosate-Resistant Rice with G6 Gene Encoding 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-Phosphate Synthase. Agric. Sci. China 2011, 10, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Meng, X.; Zong, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Gao, C. Gene replacements and insertions in rice by intron targeting using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu Zhou, H.; He, M.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Huang, Z.; Zheng, S.; Zhu, L.; Ni, E.; Jiang, D.; Zhao, B.; et al. Development of Commercial Thermo-sensitive Genic Male Sterile Rice Accelerates Hybrid Rice Breeding Using the CRISPR/Cas9-mediated TMS5 Editing System. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 37395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, W.; Zhang, D.; Qi, Y.; Yuan, Z. Generating Photoperiod-Sensitive Genic Male Sterile Rice Lines with CRISPR/Cas9. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1917, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, S.; Guojun, D.; Yu, Z.; Guocheng, H.; Qiang, Z.; Guanglian, H.; Bo, X.; Deyong, R.; Jiang, H.; Li, Z.; et al. Rapid Creation of New Photoperiod-/Thermo-Sensitive Genic Male-Sterile Rice Materials by CRISPR/Cas9 System. Rice Sci. 2019, 26, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Nolan, T.M.; Jiang, H.; Yin, Y. AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Regulatory Networks in Hormone and Abiotic Stress Responses in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant. Sci. 2019, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.B.; Li, J.; Qin, R.Y.; Xu, R.F.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.C.; Ma, H.; Li, L.; Wei, P.C.; Yang, J.B. Identification of a regulatory element responsible for salt induction of rice OsRAV2 through ex situ and in situ promoter analysis. Plant. Mol. Biol. 2016, 90, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]