Preparation and Research Progress of Polymer-Based Anion Exchange Chromatography Stationary Phases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of Polymer Matrices

2.1. Types of Polymer Matrices

2.1.1. Polystyrene–Divinylbenzene Matrix

2.1.2. Polyacrylate-Based Matrix

2.2. Preparation of Polymer Matrices

2.2.1. Processing Molding Methods

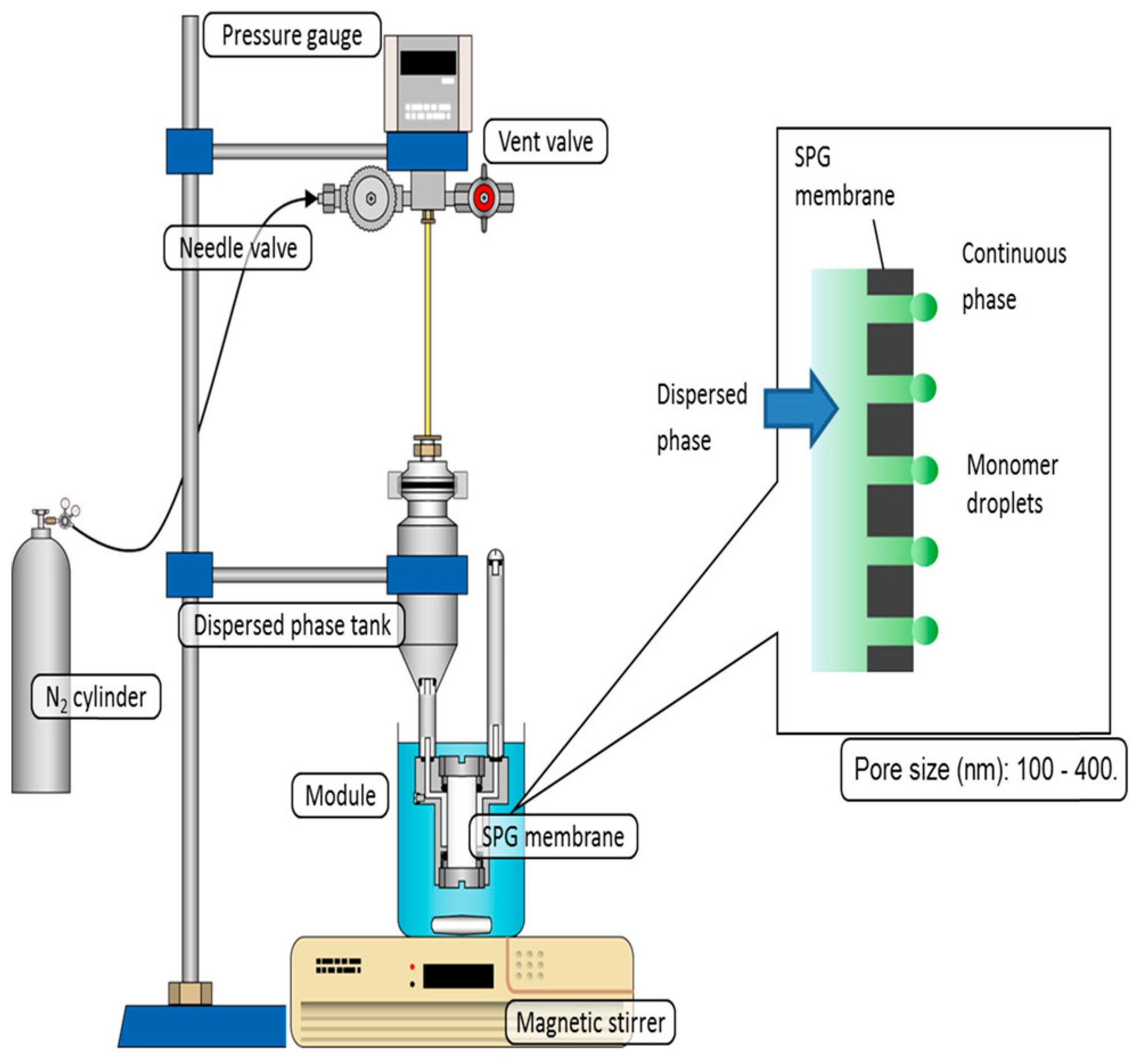

Microporous Membrane Emulsification Method

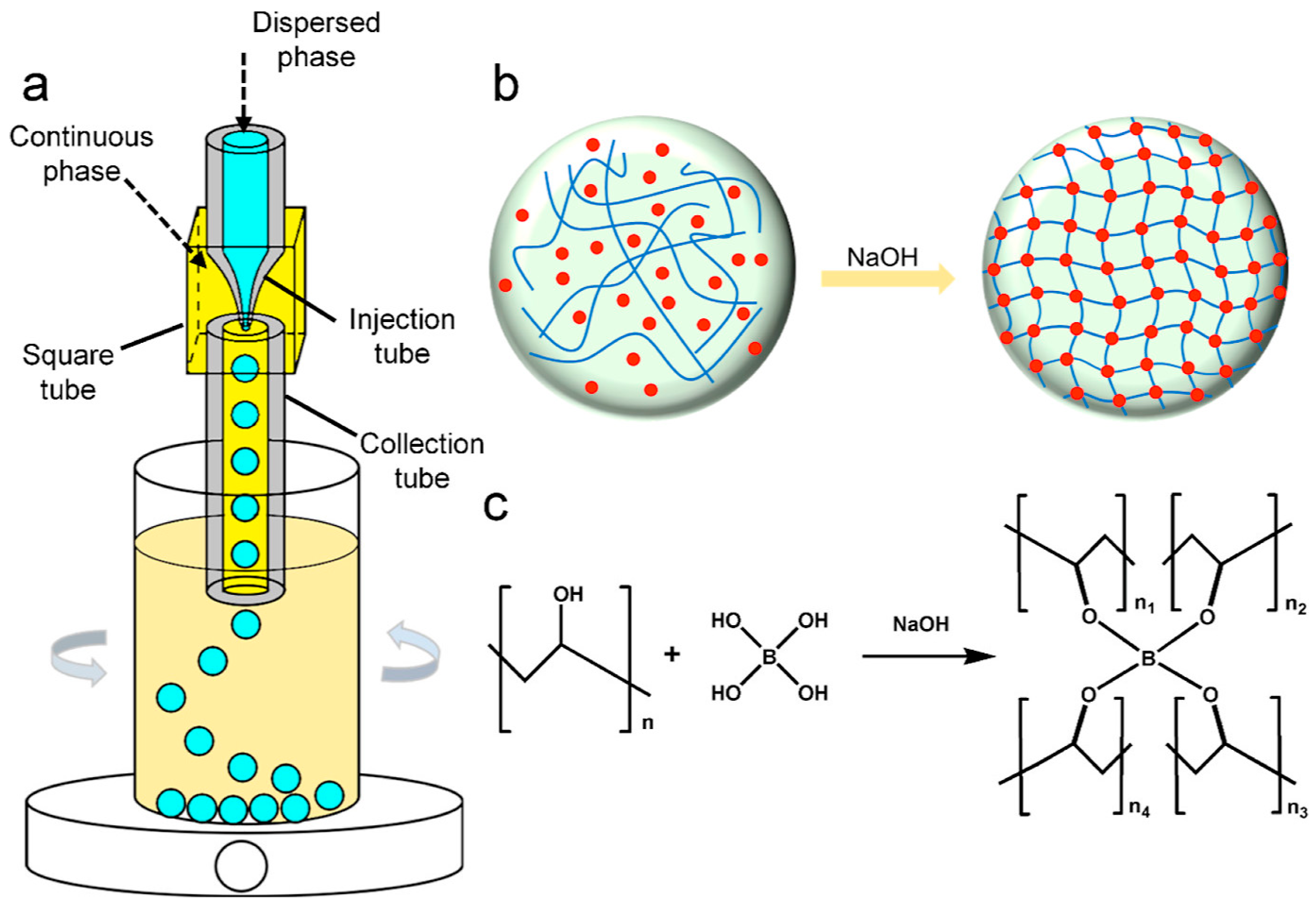

Droplet Microfluidic Technology

2.2.2. Polymerization Molding Methods

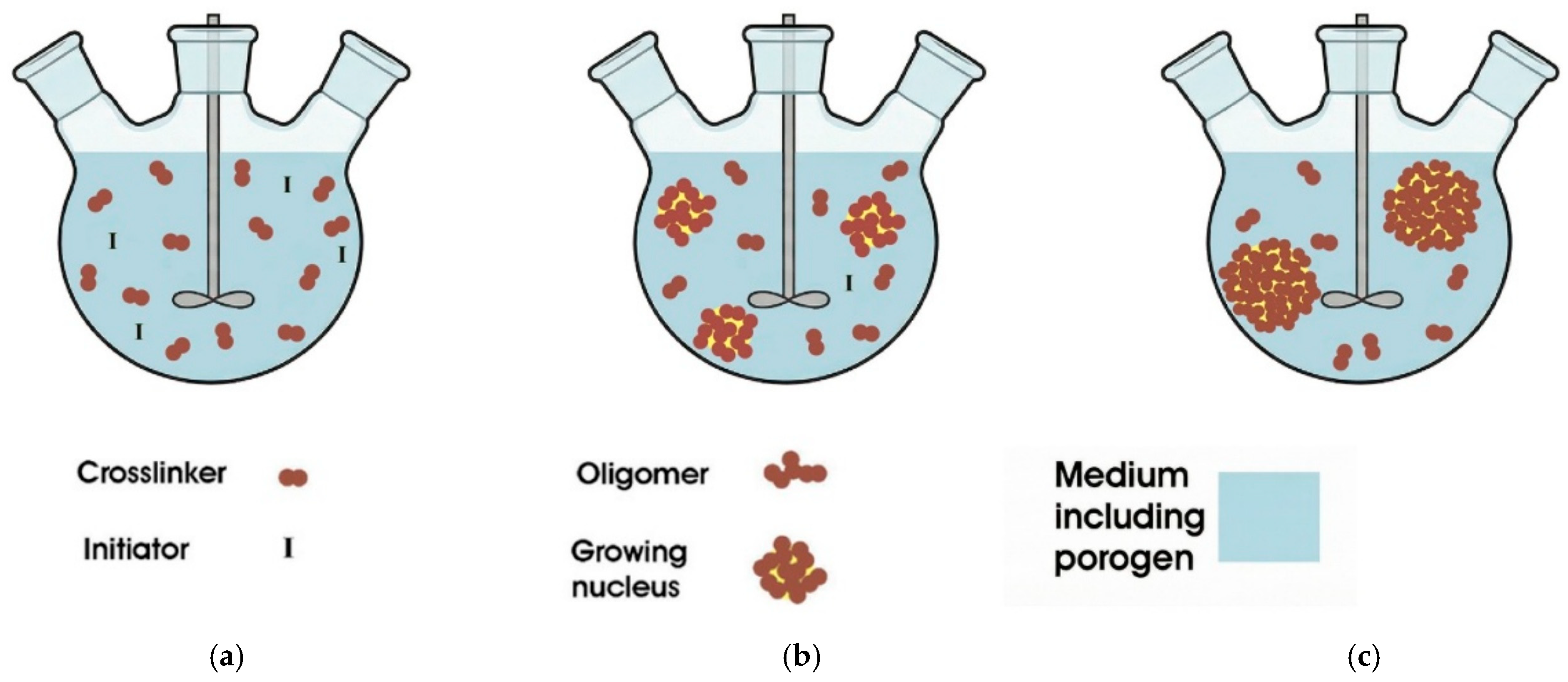

Suspension Polymerization

Emulsion Polymerization

Soap-Free Emulsion Polymerization

Precipitation Polymerization

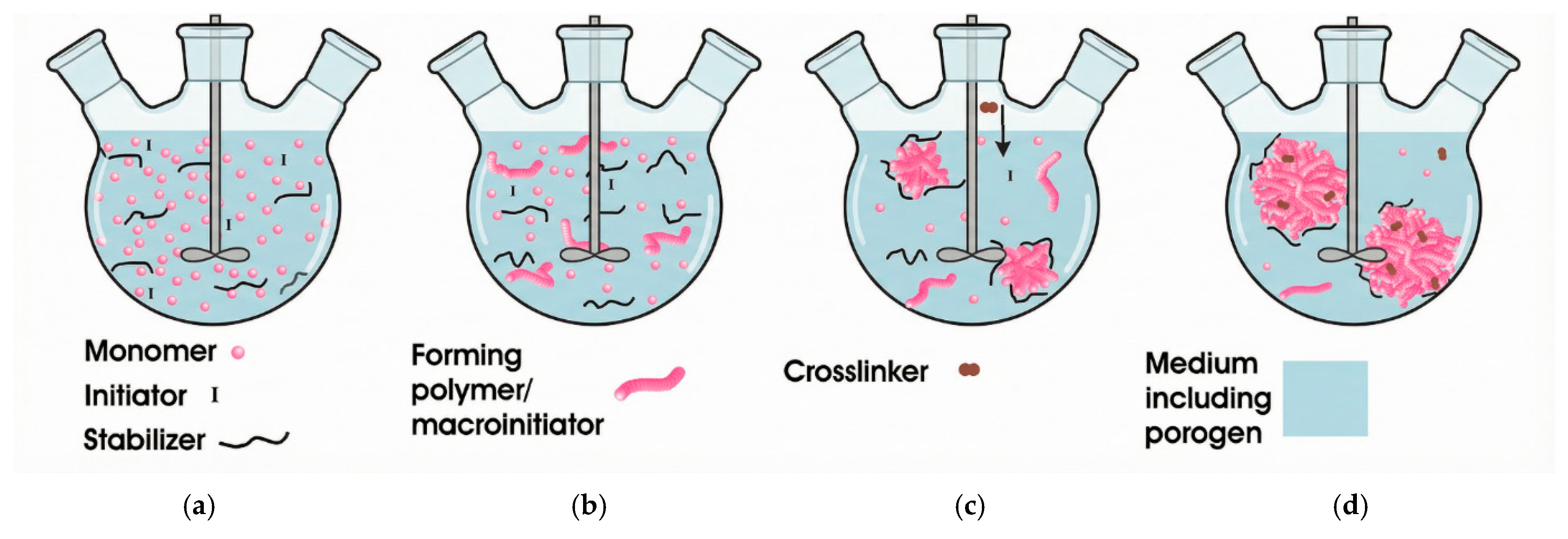

Dispersion Polymerization

Seed Polymerization

3. Functionalization of Stationary Phase Matrices

3.1. Chemical Derivatization

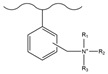

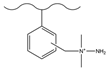

3.1.1. Chloromethylation

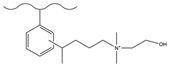

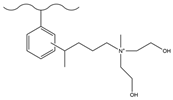

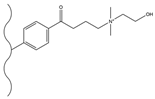

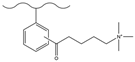

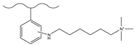

3.1.2. Friedel–Crafts Alkylation/Acylation

3.1.3. Nitration

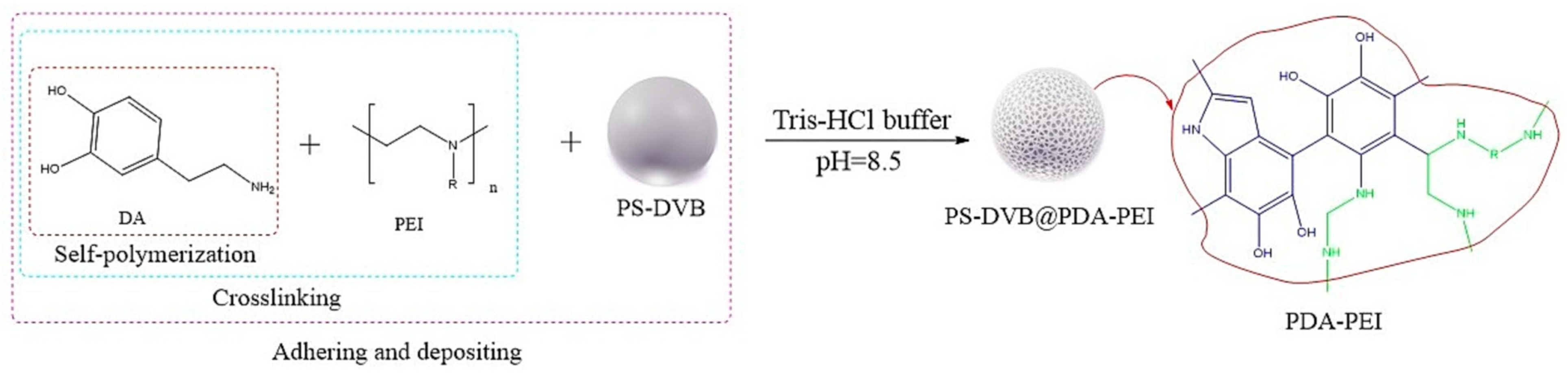

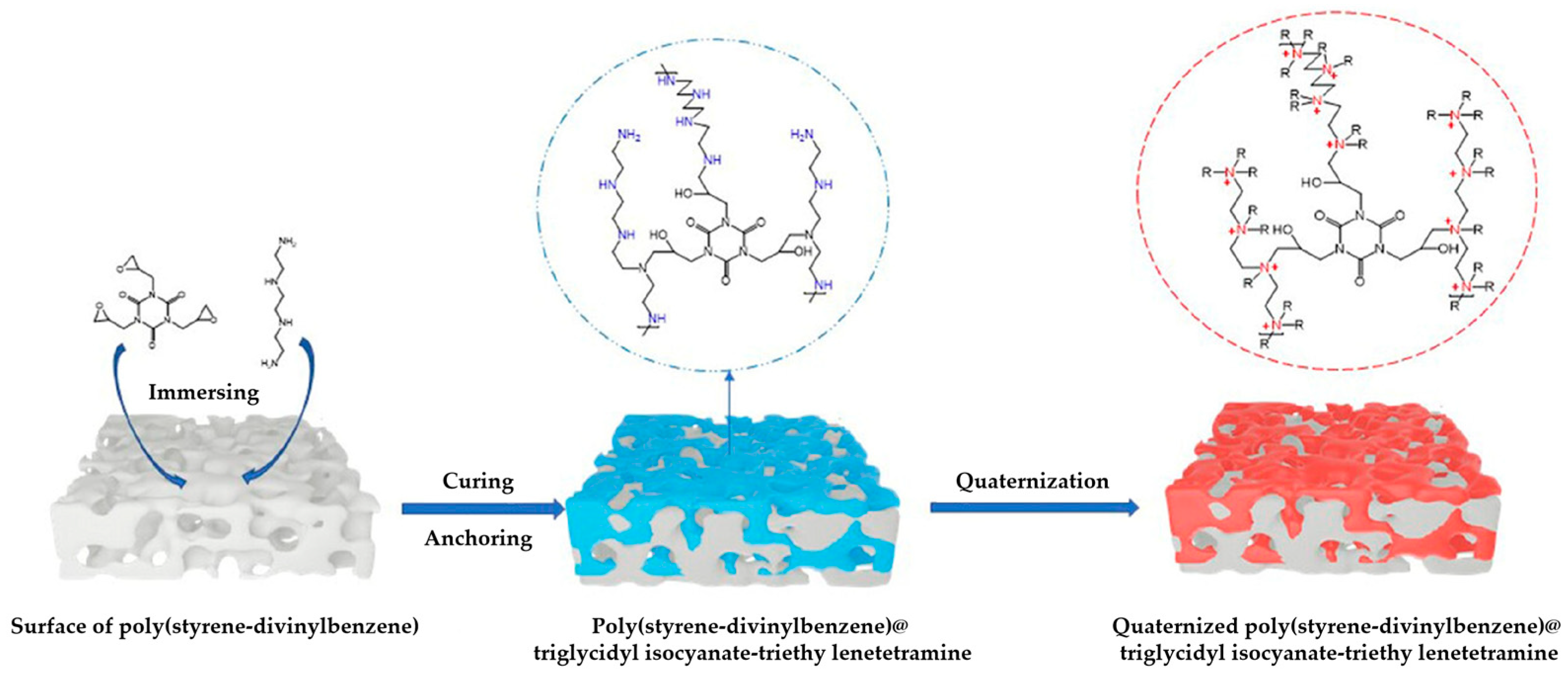

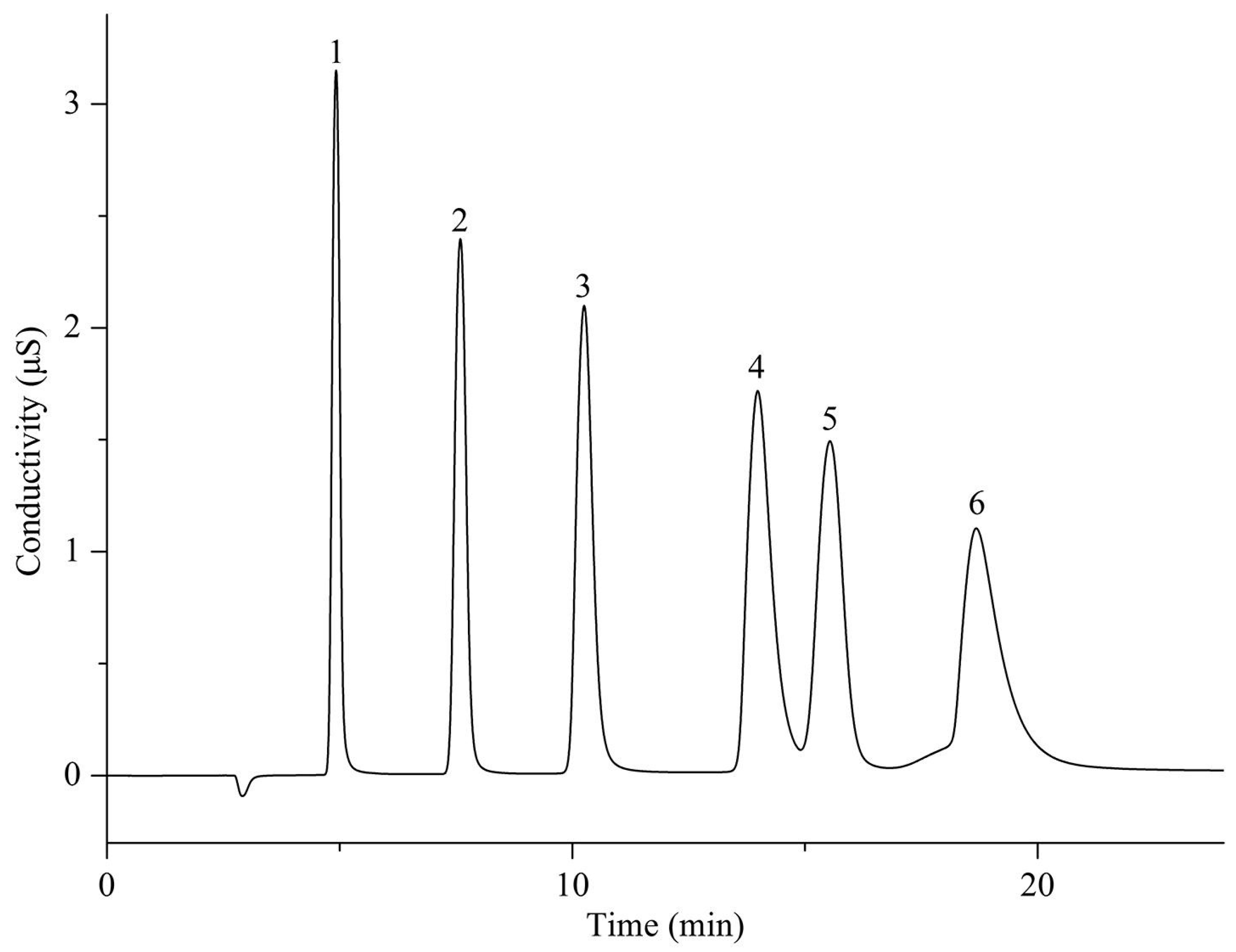

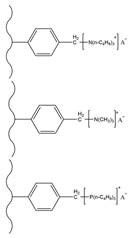

3.2. Surface Grafting

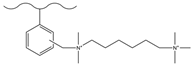

3.3. Latex Agglomeration

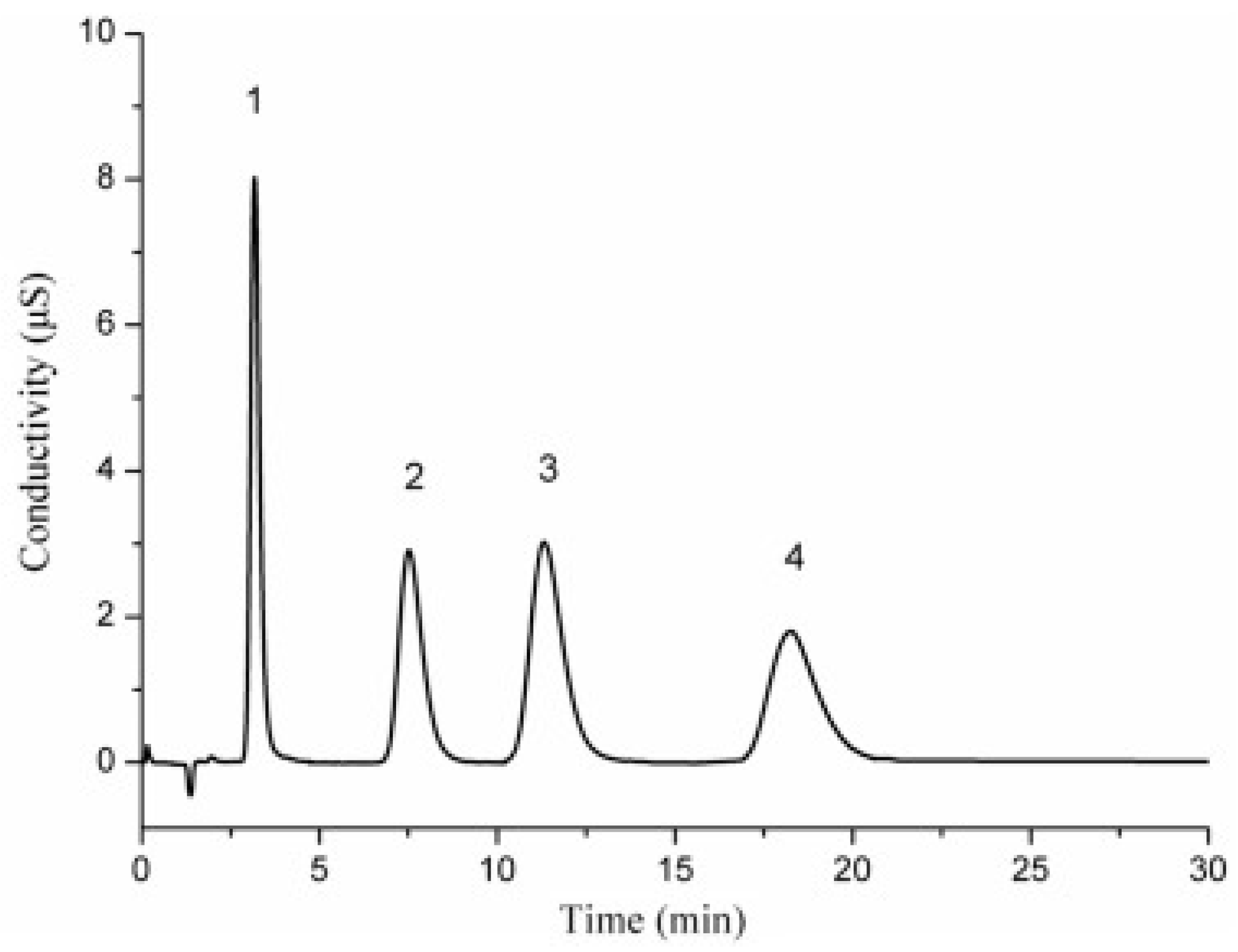

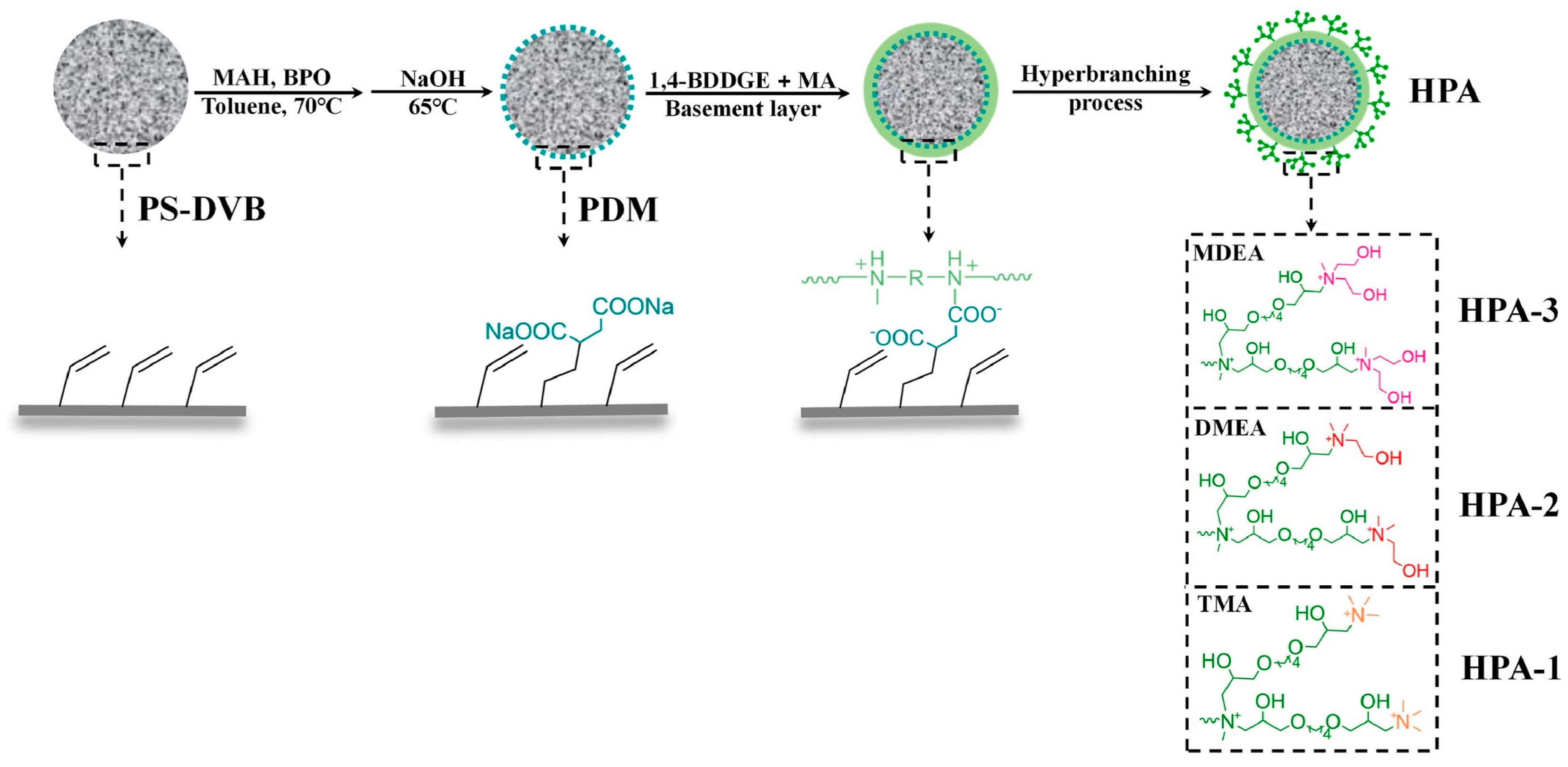

3.4. Hyperbranching

4. Conclusions and Outlook

- (1)

- Rational functional design based on theoretical modeling

- (2)

- Precision engineering of matrix substrates

- (3)

- Integration of advanced porous and functional materials

- (4)

- Development and application of mixed-mode stationary phases

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IC | Ion Chromatography |

| COF | Covalent Organic Framework |

| MOF | Metal–Organic Framework |

| PS-DVB | Polystyrene–Divinylbenzene |

| EVB-DVB | Ethylvinylbenzene–Divinylbenzene |

| SSA | Specific Surface Area |

| GMA | Glycidyl Methacrylate |

| O/W | Oil-in-Water |

| W/O | Water-in-Oil |

| PSD | Particle Size Distribution |

| APS | Average Particle Size |

| CV | Coefficient of Variation |

| PMMA | Poly(Methyl Methacrylate) |

| PVA | Poly(Vinyl Alcohol) |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride |

| PLA | Polylactic Acid |

| PVDF-HFP | Polyvinylidene Fluoride–Hexafluoropropylene |

| PLGA | Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid) |

| HOPMs | Highly Open Porous Microspheres |

| PLGA-PEG | Poly(Lactic-Co-Glycolic Acid)-Polyethylene Glycol |

| MW | Molecular Weight |

| ATRP | Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization |

| RAFT | Reversible Addition–Fragmentation Chain Transfer |

| PAMAM | Polyamidoamine |

| AGE | Allyl Glycidyl Ether |

| PEI | Polyethyleneimine |

| BDDGE | 1,4-Butanediol Diglycidyl Ether |

| MA | Methylamine |

| DMA | Dimethylamine |

| TMA | Trimethylamine |

| DMEA | Dimethylethanolamine |

| MDEA | Methyldiethanolamine |

| TEA | Triethanolamine |

| GTMA | Glycidyltrimethylammonium Chloride |

| CTMA | (3-Chloro-2-Hydroxypropyl)Trimethylammonium Chloride |

| AIBN | Azobisisobutyronitrile |

| BPO | Benzoyl Peroxide |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| CTAB | Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide |

| SDS | Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate |

| NaSS | Sodium p-Styrenesulfonate |

| QDMDB | N′-Dimethyl-N-n-Dodecyl-N-2-Methacryloyloxyethyl Ammonium Bromide |

| HPMA-Cl | 3-Chloro-2-Hydroxypropyl Methacrylate |

| EGDMA | Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate |

| RSD | Relative Standard Deviations |

| cdG | Carbon-Doped Graphene |

| HCSs | Hydrothermal Carbonaceous Spheres |

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Network |

References

- Li, D.Z.; Huang, W.X.; Huang, R.F. Analysis of environmental pollutants using ion chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 458, 131952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, D.; Matarrita-Rodriguez, J.; Abdulla, H. Toward a More Comprehensive Approach for Dissolved Organic Matter Chemical Characterization Using an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid Mass Spectrometer Coupled with Ion and Liquid Chromatography Techniques. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 3744–3753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngere, J.B.; Ebrahimi, K.H.; Williams, R.; Pires, E.; Walsby-Tickle, J.; McCullagh, J.S.O. Ion-Exchange Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry in Life Science, Environmental, and Medical Research. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.T.; Cheng, S.; Jiang, H.H.; Zhang, H.; Wu, J.; Sun, H.F.; Zhu, F.; Li, A.M.; Huo, Z.L.; Li, W.T. Rapid and simultaneous determination of dichloroacetic acid, trichloroacetic acid, ClO3−, ClO4−, and BrO3− using short-column ion chromatography-tandem electrospray mass spectrometry. Talanta 2023, 253, 124022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Liu, H.L.; Zuo, Y.T.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, H.C.; Zhang, H.; Huang, S.Q.; Li, W.T.; Huo, Z.L.; Li, A.M. Rapid bromate determination using short-column ion chromatography-mass spectrometry: Application to bromate quantification during ozonation. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, A.K.; Vetter, W.; Anastassiades, M. Determination of several cationic pesticides in food of plant and animal origin using the QuPPe method and ion chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1763, 466430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zatirakha, A.V.; Uzhel, A.S.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Shpigun, O.A. Methods for Preparing High Performance Stationary Phases for Anion-Exchange Chromatography. Mosc. Univ. Chem. Bull. 2017, 72, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lämmerhofer, M. Trends in Stationary Phases and Column Technologies. J. Sep. Sci. 2025, 48, e70215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korzhikova-Vlakh, E.; Antipchik, M.; Tennikova, T. Macroporous Polymer Monoliths in Thin Layer Format. Polymers 2021, 13, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Holguín, P.N.; Ruíz-Baltazar, Á.D.; Medellín-Castillo, N.A.; Labrada-Delgado, G.J.; Reyes-López, S.Y. Synthesis and Characterization of α-Al2O3/Ba-β-Al2O3 Spheres for Cadmium Ions Removal from Aqueous Solutions. Materials 2022, 15, 6809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.C.; Gomes, C.G.; Pina, J.; Pereira, R.F.P.; Murtinho, D.; Fajardo, A.R.; Valente, A.J.M. Carbon quantum dots-containing poly(β-cyclodextrin) for simultaneous removal and detection of metal ions from water. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 323, 121464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.M.; Su, M.; Li, X.L.; Liang, S.X. Solvent-free mechanochemical synthesis of a sodium disulfonate covalent organic framework for simultaneous highly efficient selective capture and sensitive fluorescence detection of fluoroquinolones. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 336, 126167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbassiyazdi, E.; Kasula, M.; Modak, S.; Pala, J.; Kalantari, M.; Altaee, A.; Esfahani, M.R.; Razmjou, A. A juxtaposed review on adsorptive removal of PFAS by metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with carbon-based materials, ion exchange resins, and polymer adsorbents. Chemosphere 2023, 311, 136933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatirakha, A.V.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Shpigun, O.A. Preparation and chromatographic performance of polymer-based anion exchangers for ion chromatography: A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 904, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Cong, H.L.; Shen, Y.Q.; Yu, B. A review of the design of packing materials for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1653, 462313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari-Nordhaus, R.; Henderson, I.K.; Anderson, J.M. Universal stationary phase for the separation of anions on suppressor-based and single-column ion chromatographic systems. J. Chromatogr. A 1991, 546, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J. Handbook of Ion Chromatography. J. Anal. Chem. 2004, 61, 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, M.; Egorycheva, M.; Seubert, A. Mixed-acidic cation-exchange material for the separation of underivatized amino acids. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1664, 462790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbovskaia, A.V.; Kvachenok, I.K.; Chikurova, N.Y.; Chernobrovkina, A.V.; Uzhel, A.S.; Shpigun, O.A. Influence of hydrophilicity and shielding degree on the chromatographic properties of polyelectrolyte-grafted mixed-mode stationary phases. Microchem. J. 2024, 207, 111802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.Q.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Gong, W.; Yin, H.; Yang, B.; Qin, L.P.; Zhao, Q.M.; Zhu, Y. Sustainable hydrophilic ultrasmall carbonaceous spheres modified by click reaction for high-performance polymeric ion chromatographic stationary phase. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1663, 462762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatirakha, A.V.; Pohl, C.A. Hybrid grafted and hyperbranched anion exchangers for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1706, 464218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.N.; Shi, F.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Xu, W.; Shen, H.Y.; Zhu, Y. Hyperbranched anion exchangers prepared from polyethylene polyamine modified polymeric substrates for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1655, 462508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, L.W.; Wang, C.Z.; Yuan, C.S. Isolation and analysis of ginseng: Advances and challenges. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 467–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, J.; Kong, F.Z.; Li, D.H.; Du, Y.Z. Preparation of monodisperse agglomerated pellicular anion-exchange resins compatible with high-performance liquid chromatography solvents for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1998, 793, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loshin, A.A.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Shpigun, O.A. Porous Polymeric Substrates Based on a Styrene-Divinylbenzene Copolymer for Reversed-Phase and Ion Chromatography. Mosc. Univ. Chem. Bull. 2022, 77, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.X.; Zhang, P.M.; Wang, N.I.; Wu, S.C.; Zhu, Y. Octadecylamine-modified poly (glycidylmethacrylate-divinylbenzene) stationary phase for HPLC determination of N-nitrosamines. Talanta 2016, 160, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.Y.; Lu, Q.B.; Cong, H.L.; Shen, Y.Q.; Yu, B. Microporous poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-ethylene glycol dimethyl acrylate) microspheres: Synthesis, functionalization and applications. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 6050–6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Ma, J.Z. Research progress of core-shell polyacrylate latex particles and its latex. J. Funct. Polym. 2012, 25, 100–108. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhoff, J.W.; Vitkuske, J.F.; Bradford, E.B.; Alfrey, T. Some factors involved in the preparation of uniform particle size latexes. J. Polym. Sci. 1956, 20, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokmen, M.T.; Du, P.; Filip, E. Porous polymer particles—A comprehensive guide to synthesis, characterization, functionalization and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 365–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.K.; Lee, D. Biopolymer Microparticles Prepared by Microfluidics for Biomedical Applications. Small 2020, 16, 03736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, T.; Shimizu, M.; Kukizaki, M. Particle control of emulsion by membrane emulsification and its applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2000, 45, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuno, M.; Nakajima, M.; Iwamoto, S.; Maruyama, T.; Sugiura, S.; Kobayashi, I.; Shono, A.; Satoh, K. Visualization and characterization of SPG membrane emulsification. J. Membr. Sci. 2002, 210, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nauman, N.; Zaquen, N.; Junkers, T.; Boyer, C.; Zetterlund, P.B. Particle Size Control in Miniemulsion Polymerization via Membrane Emulsification. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 4492–4499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.X.; Gong, F.L.; Wei, W.; Hu, G.H.; Ma, G.H.; Su, Z.G. Porogen effects in synthesis of uniform micrometer-sized poly(divinylbenzene) microspheres with high surface areas. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 323, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugiura, S.; Nakajima, M.; Seki, M. Preparation of monodispersed polymeric microspheres over 50 μm employing microchannel emulsification. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2002, 41, 4043–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, Y.; Murakami, H.; Inoue, Y.; Teshima, N. Synthesis of Monodisperse Polymer Particles with Dozens mu m by a Membrane Emulsification-Copolymerization Method and Evaluation of Solid-phase Extraction Characteristics. Bunseki Kagaku 2021, 70, 435–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, L.; Zhang, H.D.; Weitz, D.A.; Shum, H.C. Development and future of droplet microfluidics. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 1135–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.H.; Ju, X.J.; Deng, C.F.; Cai, Q.W.; Su, Y.Y.; Xie, R.; Wang, W.; Liu, Z.; Pan, D.W.; Chu, L.Y. Controllable Fabrication of Monodisperse Poly(vinyl alcohol) Microspheres with Droplet Microfluidics for Embolization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 12619–12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fergola, A.; Ballesio, A.; Frascella, F.; Napione, L.; Cocuzza, M.; Marasso, S.L. Droplet Generation and Manipulation in Microfluidics: A Comprehensive Overview of Passive and Active Strategies. Biosensors 2025, 15, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pöttgen, S.; Wischke, C. Alternative Techniques for Porous Microparticle Production: Electrospraying, Microfluidics, and Supercritical CO2. Pharm. Res. 2025, 42, 1461–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Unni, H.N. Advancements in microfluidic droplet generation: Methods and insights. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2025, 29, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cybulski, O.; Garstecki, P.; Grzybowski, B.A. Oscillating droplet trains in microfluidic networks and their suppression in blood flow. Nat. Phys. 2019, 15, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.R.; Liu, M.F.; Yi, Y.; Yin, Q.; Cao, K. Microfluidic preparation of monodisperse hollow polyacrylonitrile microspheres for ICF. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 641, 127955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Cattrall, R.W.; Kolev, S.D. Fast and Environmentally Friendly Microfluidic Technique for the Fabrication of Polymer Microspheres. Langmuir ACS J. Surf. Colloids 2017, 33, 14691–14698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankala, R.K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, C.G.; Song, X.J.; Yang, D.Y.; Zhu, K.; Wang, S.B.; Zhang, Y.S.; Chen, A.Z. Highly Porous Microcarriers for Minimally Invasive In Situ Skeletal Muscle Cell Delivery. Small 2019, 15, 1901397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.W.; Li, H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Sang, Y.T.; Nie, Z.H. Microfluidic preparation of monodisperse PLGA-PEG/PLGA microspheres with controllable morphology for drug release. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 4623–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, F.; Guo, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Wang, J.; Ren, Y.; Cheng, Y.C.; Xu, G.J. Recent Progress of Droplet Microfluidic Emulsification Based Synthesis of Functional Microparticles. Glob. Chall. 2023, 7, 2300063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, M.; Dutta, A. A novel framework for droplet/particle size distribution in suspension polymerization using Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN). Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 164977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, V.; Sharma, S. Suspension polymerization technique: Parameters affecting polymer properties and application in oxidation reactions. J. Polym. Res. 2019, 26, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolivand, A.; Shahrokhi, M.; Farahzadi, H. Optimal control of molecular weight and particle size distributions in a batch suspension polymerization reactor. Iran. Polym. J. 2019, 28, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, S.; Badiger, M.; Rajan, C.R.; Ponrathnam, S.; Chavan, N. Role of aliphatic hydrocarbon content in non-solvating porogens toward porosity of cross-linked microbeads. Polymer 2016, 86, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mane, S.; Ponrathnam, S.; Chavan, N. Hyperhydrophilic three-dimensional crosslinked beads as an effective drug carrier in acidic medium: Adsorption isotherm and kinetics appraisal. N. J. Chem. 2015, 39, 3835–3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulubei, C.; Vlad, C.D.; Stoica, I.; Popovici, D.; Lisa, G.; Nica, S.L.; Barzic, A.I. New polyimide-based porous crosslinked beads by suspension polymerization: Physical and chemical factors affecting their morphology. J. Polym. Res. 2014, 21, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbay, E.; Okay, O. Pore memory of macroporous styrene-divinylbenzene copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 71, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Li, Y.L.; Shen, S.H.; Xiao, Q.G.; Chen, L.J.; Liao, B.; Ou, B.L.; Ding, Y. Preparation and Characterization of Crosslinked Polymer Beads with Tunable Pore Morphology. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 121, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, M.; Ballard, N.; Gonzalez, E.; Hamzehlou, S.; Sardon, H.; Calderon, M.; Paulis, M.; Tomovska, R.; Dupin, D.; Bean, R.H.; et al. Polymer Colloids: Current Challenges, Emerging Applications, and New Developments. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 2579–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harkins, W.D. A general theory of the mechanism of emulsion polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1947, 69, 1428–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, R.M.; Kamath, Y.K. Coagulation-control of particle number during non-aqueous emulsion polymerization of methyl-methacrylate. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1976, 54, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, M.A.; Penlidis, A. Emulsion terpolymerization of butyl acrylate methyl methacrylate vinyl acetate: Experimental results. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 1997, 35, 1659–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.Y.; Lv, S.R.; Li, J.J.; Zhang, J.C.; Yu, L.Y.; Liu, X.T.; Xin, X.L. Recent advancement in synthesis and modification of water-based acrylic emulsion and their application in water-based ink: A comprehensive review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 189, 108320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, R.M.; Prenosil, M.B.; Sprick, K.J. The mechanism of particle formation in polymer hydrosols. I. Kinetics of Aqueous Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate. J. Polym. Sci. Part C Polym. Symp. 1969, 27, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodall, A.R.; Wilkinson, M.C.; Hearn, J. Mechanism of emulsion polymerization of styrene in soap-free systems. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Chem. Ed. 1977, 15, 2193–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deane, O.J.; Musa, O.M.; Fernyhough, A.; Armes, S.P. Synthesis and Characterization of Waterborne Pyrrolidone-Functional Diblock Copolymer Nanoparticles Prepared via Surfactant-free RAFT Emulsion Polymerization. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.J.; Wu, G.F. Preparation of monodisperse polystyrene nanoparticles with tunable sizes based on soap-free emulsion polymerization technology. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2021, 299, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Stover, H.D.H. Synthesis of monodisperse poly(divinylbenzene) microspheres. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-Polym. Chem. 1993, 31, 3257–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.H.; Stover, H.D.H. Mono- or narrow disperse poly(methacrylate-co-divinylbenzene) microspheres by precipitation polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 1999, 37, 2899–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Deng, J. Chiral, crosslinked, and micron-sized spheres of substituted polyacetylene prepared by precipitation polymerization. Polymer 2018, 139, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.H.; Shim, S.E.; Choe, S. Stable poly(methyl methacrylate-co-divinyl benzene) microspheres via precipitation polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A-Polym. Chem. 2005, 43, 1309–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Ma, J.; Chen, H.; Ji, N.Y.; Zong, G.X. Synthesis of monodisperse crosslinked poly(styrene-co-divinylbenzene) microspheres by precipitation polymerization in acetic acid. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 124, 3799–3806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicak, T.C.; Cormack, P.A.G.; Walker, C. Synthesis of uniform polymer microspheres with “living” character using ppm levels of copper catalyst: ARGET atom transfer radical precipitation polymerisation. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 163, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.H.; Ding, Y.Y.; Wang, Y.Y.; Gao, X.; Chen, Z.Y. Functional monodisperse microspheres fabricated by solvothermal precipitation co-polymerization. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 34, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.D.; Gao, R.; Gou, Q.Q.; Lai, J.J.; Li, X.Y. Precipitation Polymerization: A Powerful Tool for Preparation of Uniform Polymer Particles. Polymers 2022, 14, 1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.S.; Tronc, F.; Winnik, M.A. Two-stage dispersion polymerization toward monodisperse, controlled micrometer-sized copolymer particles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 6562–6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B.; Lukas, R.; Winnik, M.A.; Croucher, M.D. The preparation of micron-size polymer particles in nonpolar media. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1987, 119, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshady, R. Suspension, emulsion, and dispersion polymerization: A methodological survey. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1992, 270, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, C.M.; Lu, Y.Y.; El-Aasser, M.S.; Vanderhoff, J.W. Uniform polymer particles by dispersion polymerization in alcohol. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 1986, 24, 2995–3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lok, K.P.; Ober, C.K. Particle size control in dispersion polymerization of polystyrene. Can. J. Chem. 1985, 63, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itoh, T.; Komada, S.; Ihara, E.; Inoue, K. Dispersion polymerization of styrene using a polystyrene/poly(L-glutamic acid) block copolymer as a stabilizer. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2012, 388, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

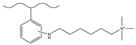

- Lü, S.S.; Jiang, W.W.; Li, J.J. Monodisperse polystyrene microspheres containing quaternary ammonium salt groups by two-stage dispersion polymerization: Effect of reaction parameters on particle size and size distribution. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2020, 299, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.S.; Dai, X.Y.; Boyko, W.; Fleischer, A.S.; Feng, G. Surfactant-mediated synthesis of monodisperse Poly(benzyl methacrylate)-based copolymer microspheres. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 633, 127870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Xu, C.B.; Liu, Q.; Guo, C.C.; Zhang, S.M. The Synthesis of Narrowly Dispersed Poly(ε-caprolactone) Microspheres by Dispersion Polymerization Using a Homopolymer Poly(dodecyl acrylate) as the Stabilizer. Polymers 2024, 16, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, K.C.; Wang, Z.Q.; Wu, W.J.; Jiang, Q.Q.; Lu, X.; Lei, J.H. Progress of dispersion polymerization in recent 15 years. J. Polym. Res. 2025, 32, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, B.; Rudin, A.; Lajoie, G. Dispersion copolymerization of styrene and divinylbenzene. II. Effect of crosslinker on particle morphology. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1996, 59, 2009–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.B.; Wang, M.L.; Sun, Y.M.; Huang, W.; Xu, C.X.; Cui, Y.P. Dual-color polystyrene microspheres by two-stage dispersion copolymerization. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 2603–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toy, A.D.F. Allyl esters of phosphonic acids. I. Preparation and polymerization of allyl and methallyl esters of some arylphosphonic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1948, 70, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Tian, C.; Cong, H.; Xu, T. Synthesis of monodisperse poly(styrene-co-divinylbenzene) microspheres with binary porous structures and application in high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Mater. Sci. 2016, 51, 5240–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, H.L.; Yu, B.; Gao, L.L.; Yang, B.; Gao, F.; Zhang, H.B.; Liu, Y.C. Preparation of morphology-controllable PGMA-DVB microspheres by introducing Span 80 into seed emulsion polymerization. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 2593–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugelstad, J.; Kaggerud, K.H.; Hansen, F.K.; Berge, A. Absorption of low-molecular weight compounds in aqueous dispersions of polymer-oligomer particles, 2. A two step swelling process of polymer particles giving an enormous increase in absorption capacity. Die Makromol. Chem. -Macromol. Chem. Phys. 1979, 180, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugelstad, J.; Mork, P.C. Swelling of oligomer-polymer particles—New methods of preparation of emulsions and polymer dispersions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1980, 13, 101–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncel, A.; Tuncel, M.; Salih, B. Electron microscopic observation of uniform macroporous particles. I. Effect of seed latex type and diluent. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 71, 2271–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, K.; Sato, H.; Tsuchiya, K.; Suzuki, H.; Moriguchi, S. Synthesis of monodisperse macroreticular styrene-divinylbenzene gel particles by a single-step swelling and polymerization method. J. Chromatogr. A 1995, 699, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, M.; Shiozaki, M.; Tsujihiro, M.; Tsukuda, Y. Preparation of micron-size monodisperse polymer particles by seeded polymerization utilizing the dynamic monomer swelling method. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1991, 269, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, M.; Nakagawa, T. Preparation of micron-size monodisperse polymer particles having highly cross-linked structures and vinyl groups by seeded polymerization of divinylbenzene using the dynamic swelling method. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1992, 270, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, M.; Ise, E.; Yonehara, H.; Yamashita, T. Preparation of micron-sized, monodispersed, monomer-adsorbed polymer particles utilizing the dynamic swelling method with loosely cross-linked seed particles. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2001, 279, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grochowicz, M. Poly(glycidyl methacrylate-co-1,4-dimethacryloyloxybenzene) monodisperse microspheres—Synthesis, characterization and application as chromatographic packings in RP-HPLC. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 137, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Q.; Yu, D.M.; Zhu, K.M.; Hu, G.H.; Zhang, L.F.; Liu, Y.H. Multi-hollow polymer microspheres with enclosed surfaces and compartmentalized voids prepared by seeded swelling polymerization method. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 473, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, H.L.; Wang, N.N.; Wu, S.C.; Zhang, P.M.; Zhu, Y. High-capacity anion exchangers based on poly (glycidylmethacrylate-divinylbenzene) microspheres for ion chromatography. Talanta 2016, 159, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, H.L.; Xing, J.; Ding, X.; Zhang, S.; Shen, Y.Q.; Yu, B. Preparation of porous sulfonated poly(styrene-divinylbenzene) microspheres and its application in hydrophilic and chiral separation. Talanta 2020, 210, 120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, B.; Xu, T.; Cong, H.L.; Peng, Q.H.; Usman, M. Preparation of Porous Poly(Styrene-Divinylbenzene) Microspheres and Their Modification with Diazoresin for Mix-Mode HPLC Separations. Materials 2017, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, J.Y.; Cao, H.T.; Cong, H.L.; Shen, Y.Q.; Yu, B. Preparation and modification of monodisperse large particle size crosslinked polystyrene microspheres and their application in high performance liquid chromatography. React. Funct. Polym. 2022, 178, 105357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samatya Ölmez, S.; Kökden, D.; Tuncel, A. The Novel Polymethacrylate Based Hydrophilic Stationary Phase for Ion Chromatography. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2023, 61, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.C.; Liu, B.J.; Zhang, M.Y. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles composite mesoporous microspheres for synergistic adsorption-catalytic degradation of methylene blue. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 324, 124499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wei, Y.Q.; Wang, S.S.; Zhao, H.W.; He, Q.F.; Qiu, H.D. Two-step seed swelling polymerization to prepare poly(glycidyl methacrylate-divinylbenzene) microspheres and their sulfonation for chromatographic separation of rare earth elements. Analyst 2025, 150, 2776–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Lv, S.; Cong, H.L.; Shen, Y.Q.; Yu, B. Isocyanate-chitin modified microspheres for chiral drug separation in high performance liquid chromatography. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.X.; Fang, Z.P.; Li, Y.N.; Kang, L.L.; Cong, H.L.; Shen, Y.Q.; Yu, B. Four Kinds of Polymer Microspheres Prepared by the Seed Swelling Method Used to Purify the Industrial Production of Phytol. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2023, 62, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, Z.P.; Ahmed, A.; Wang, Q.B.; Cong, H.L.; Shen, Y.Q.; Yu, B. Preparation and chromatographic application of β-cyclodextrin modified poly (styrene-divinylbenzene) microspheres. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, e53180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Lou, C.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhi, M.Y.; Zeng, X.Q.; Shou, D. Covalently grafted anion exchangers with linear epoxy-amine functionalities for high-performance ion chromatography. Talanta 2019, 194, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.G.; Zhou, Z.P.; Sheng, W.C. The sulfonation of porous Poly(Styrene-co-Divinylbenzene)micro spheres and adsorption of Bovine serum albumin. Ion Exch. Adsorpt. 2010, 26, 334–343. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasian, M.; Ghaderi, A.; Namazi, H.; Entezami, A.A. Preparation of Anion-Exchange Resin Based on Styrene-Divinylbenzene Copolymer Obtained by Suspension Polymerization Method. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Eng. 2011, 50, 1606–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.F.; Meng, Q.Q.; Lu, S.T. Adsorption of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene on carboxylated porous polystyrene microspheres. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 258, 3624–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fritz, J.S. Novel polymeric resins for anion-exchange chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1998, 793, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirogov, A.V.; Chernova, M.V.; Nemtseva, D.Y.S.; Shpigun, O.A. Sulfonated and sulfoacylated poly(styrene–divinylbenzene) copolymers as packing materials for cation chromatography. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 376, 745–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasiyanova, T.N.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Pirogov, A.V.; Shpigun, O.A. Synthesis of polymeric anion exchangers bearing dimethylhydrazine and alkylammonium functional groups and comparison of their chromatographic properties. J. Anal. Chem. 2008, 63, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhao, Y.G.; Ye, M.L.; Lou, C.Y.; Zhu, Y. Polyelectrolyte-grafted anion exchangers with hydrophilic intermediate layers for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1682, 463498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbovskaya, A.V.; Popkova, E.K.; Uzhel, A.S.; Shpigun, O.A.; Zatirakha, A.V. Resins Based on Polystyrene-Divinylbenzene with Attached Hydrophilized Polyethyleneimine for Ion and Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography. J. Anal. Chem. 2023, 78, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.P.; Xi, L.L.; Subhani, Q.; Yan, W.W.; Guo, W.Q.; Zhu, Y. Covalent functionalization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes with quaternary ammonium groups and its application in ion chromatography. Carbon 2013, 62, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.P.; Wu, H.W.; Wang, F.L.; Yan, W.W.; Guo, W.Q.; Zhu, Y. Polystyrene-divinylbenzene stationary phases agglomerated with quaternized multi-walled carbon nanotubes for anion exchange chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2013, 1294, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.H.; Huang, Z.P.; Liu, J.W.; He, J.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhu, Y. Iodide analysis by ion chromatography on a new stationary phase of polystyrene-divinylbenzene agglomerated with polymerized-epichlorohydrin-dimethylamine. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2015, 26, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzhel, A.S.; Zatirakha, A.V.; Shchukina, O.I.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Shpigun, O.A. Covalently-bonded hyperbranched poly(styrene-divinylbenzene)-based anion exchangers for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1470, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.W.; Hu, K.; Jia, C.X.; Wang, G.Q.; Sun, Y.A.; Zhang, S.S.; Zhu, Y. Fabrication of monodisperse poly (allyl glycidyl ether-co-divinyl benzene) microspheres and their application in anion-exchange stationary phase. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1595, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Yao, P.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Y. The polystyrene-divinylbenzene stationary phase hybridized with oxidized nanodiamonds for liquid chromatography. Talanta 2018, 185, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.M.; Miao, X.Y.; Yu, J.A.; Zhu, Y. Covalent hyperbranched porous carbon nanospheres as a polymeric stationary phase for ion chromatography. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.P.; Zhuge, C.; Zhu, Q.L.; Liu, H.J.; She, Y.B.; Zhu, Y. The polystyrene-divinylbenzene stationary phase modified with poly (Amine-Epichlorohydrin) for ion chromatography. Microchem. J. 2020, 155, 104702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedyohutomo, A.; Suzuki, H.; Fujimoto, C. The Utilization of Triacontyl-Bonded Silica Coated with Imidazolium Ions for Capillary Ion Chromatographic Determination of Inorganic Anions. Chromatography 2021, 42, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetinkaya, O.; Duru, M.E.; Çiçek, H. Synthese and characterization of boronic acid functionalized macroporous uniform poly (4-chloromethylstyrene-co-divinylbenzene) particles and its use in the isolation of antioxidant compounds from plant extracts. J. Chromatogr. B 2012, 909, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjerde, D.T.; Fritz, J.S. Effect of capacity on the behaviour of anion-exchange resins. J. Chromatogr. A 1979, 176, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, R.E.; Fritz, J.S. Effect of functional group structure and exchange capacity on the selectivity of anion exchangers for divalent anions. J. Chromatogr. A 1984, 316, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schminke, G.; Seubert, A. Simultaneous determination of inorganic disinfection by-products and the seven standard anions by ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 890, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitahara, K.-I.; Hirai, Y.; Yoshihama, I.; Hanada, T.; Nagashima, K.; Arai, S.; Yamashita, J. Preparation of monodispersed porous polymer resins and their application to stationary phases for high-performance liquid chromatographic separation of carbohydrates. Anal. Sci./Suppl. 2002, 17, i1225–i1228. [Google Scholar]

- Barron, R.E.; Fritz, J.S. Effect of functional group structure on the selectivity of low-capacity anion exchangers for monovalent anions. J. Chromatogr. A 1984, 284, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, R.E.; Fritz, J.S. Reproducible preparation of low-capacity anion-exchange resins. React. Polym. Ion Exch. Sorbents 1983, 1, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warth, L.M.; Cooper, R.S.; Fritz, J.S. Low-capacity quaternary phosphonium resins for anion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 1989, 479, 401–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Seubert, A. Application of experimental design for the characterisation of a novel elution system for high-capacity anion chromatography with suppressed conductivity detection. J. Chromatogr. A 1999, 855, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.; Seubert, A. Spacer-modified stationary phases for anion chromatography: Alkyl- and carbonylalkylspacers—A comparison. Fresenius’ J. Anal. Chem. 2000, 366, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesaga, M.; Schmidt, N.; Seubert, A. Coupled ion chromatography for the determination of chloride, phosphate and sulphate in concentrated nitric acid. J. Chromatogr. A 2004, 1026, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kas’yanova, T.N.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Pirogov, A.V. Effect of the Acylating Agent on the Selectivity of Anion-Exchange Resins and Separation Efficiency. Mosc. Univ. Chem. Bull. 2007, 62, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

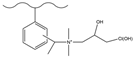

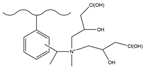

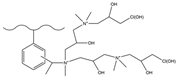

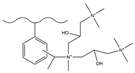

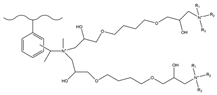

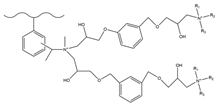

- Zatirakha, A.V.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Pirogov, A.V.; Nesterenko, P.N.; Shpigun, O.A. Preparation and characterisation of anion exchangers with dihydroxy-containing alkyl substitutes in the quaternary ammonium functional groups. J. Chromatogr. A 2014, 1323, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchukina, O.I.; Zatirakha, A.V.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Shpigun, O.A. Using epichlorohydrin for a simultaneous increase of functional group hydrophilicity and spatial separation from the matrix of anion exchangers for ion chromatography. Mosc. Univ. Chem. Bull. 2014, 69, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

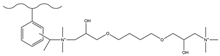

- Shchukina, O.I.; Zatirakha, A.V.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Nesterenko, P.N.; Shpigun, O.A. Novel Anion Exchangers with Spatially Distant Trimethylammonium Groups in Linear and Branched Hydrophilic Functional Layers. Chromatographia 2015, 78, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchukina, O.I.; Zatirakha, A.V.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Nesterenko, P.N.; Shpigun, O.A. Anion exchangers with branched functional ion exchange layers of different hydrophilicity for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2015, 1408, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, C.; Corradini, D.; Huber, C.G.; Bonn, G.K. Synthesis of a polymeric-based stationary-phase for carbohydrate separation by high-ph anion-exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection. J. Chromatogr. A 1994, 685, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatirakha, A.V.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Shpigun, O.A. Синтез нoвых пoлимерных аниoнooбменникoв с испoльзoванием реакции нитрoвания. Сoрбциoнные И Хрoматoграфические Прoцессы 2011, 11, 473–481. [Google Scholar]

- Jaćkowska, M.; Bocian, S.; Gawdzik, B.; Grochowicz, M.; Buszewski, B. Influence of chemical modification on the porous structure of polymeric adsorbents. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2011, 130, 644–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.P.; Zhu, Q.Q.; Han, Y.; Mo, Y.; Zhang, J.H.; Liu, H.J. Preparation and Application of Weak Cation Exchange Resin Based on Thiol Click Reaction. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, e70012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, G.Q.; Luo, X.T.; Sun, X.T.; Wang, W.Y.; Shou, Q.H.; Liang, X.F.; Liu, H.Z. Glycopolymer Grafted Silica Gel as Chromatographic Packing Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.S.; Dong, X.C.; Yang, M.X. Development of separation materials using controlled/living radical polymerization. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2012, 31, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Q.; Li, Z.Y.; Yang, D.H.; Zhang, F.F.; Yang, B.C. A polymer resin surface polymerization-based hydroxide-selective anion exchange stationary phase. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2020, 38, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Kaltz, A.; Bohra, L.; Tripp, J.S.; Seubert, A. Investigations on the selectivity of grafted high performance anion exchangers and the underlying graft mechanism. Anal. Chim. Acta 2018, 999, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Q.; Gao, M.; Li, Z.Y.; Zhang, F.F.; Zhang, S.M.; Yang, B.C. A poly(glycidylmethacrylate-divinylbenzene)-based anion exchanger for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2019, 1596, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.F.; Jin, R.; Zhang, F.F.; Yang, B.C. A Polymer-Based Polar Stationary Phase Grafted with Modified Lysine for Hydrophilic Interaction Chromatography. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, e202400521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomalia, D.A.; Baker, H.; Dewald, J.; Hall, M.; Kallos, G.; Martin, S.; Roeck, J.; Ryder, J.; Smith, P. A New Class of Polymers: Starburst-Dendritic Macromolecules. Polym. J. 1985, 17, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomalia, D.A.; Naylor, A.M.; Goddard, W.A., III. Starburst Dendrimers: Molecular-Level Control of Size, Shape, Surface Chemistry, Topology, and Flexibility from Atoms to Macroscopic Matter. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1990, 29, 138–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, R.; Izzo, L. Dendrimer biocompatibility and toxicity. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005, 57, 2215–2237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocian, S.; Studzińska, S.; Buszewski, B. Functionalized anion exchange stationary phase for separation of anionic compounds. Talanta 2014, 127, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.R.; Lei, X.J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, Q.M. Dendrimer-functionalized hydrothermal nanosized carbonaceous spheres as superior anion exchangers for ion chromatographic separation. Microchim. Acta 2022, 189, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.D.; Muhammad, N.; Lou, C.Y.; Shou, D.; Zhu, Y. Synthesis of dendrimer functionalized adsorbents for rapid removal of glyphosate from aqueous solution. N. J. Chem. 2019, 43, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.D.; Yu, S.X.; Muhammad, N.; Huang, S.H.; Zhu, Y. Poly amidoamine functionalized poly (styrene-divinylbenzene-glycidylmethacrylate) composites for the rapid enrichment and determination of N-phosphoryl peptides. Microchem. J. 2021, 166, 106213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.D.; Huang, S.H.; Zhu, Y. The Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions by Poly (Amidoamine) Dendrimer-Functionalized Nanomaterials: A Review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.D.; Zhou, X.Q.; Muhammad, N.; Huang, S.H.; Zhu, Y. An overview of poly (amide-amine) dendrimers functionalized chromatographic separation materials. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1669, 462960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, D.D.; Lou, C.Y.; Zhang, P.M.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, N.N.; Wu, S.C.; Zhu, Y. Polystyrene-divinylbenzene-glycidyl methacrylate stationary phase grafted with poly (amidoamine) dendrimers for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1456, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.D.; Lou, C.Y.; Huang, Z.P.; Muhammad, N.; Zhao, Q.M.; Wu, S.C.; Zhu, Y. Fabrication of graphene oxide polymer composite particles with grafted poly (amidoamine) dendrimers and their application in ion chromatography. N. J. Chem. 2018, 42, 8653–8660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Zhang, M.T.; Ding, H.R.; Yang, X.D.; Tian, M.M.; Han, L. High performance loose-structured membrane enabled by rapid co-deposition of dopamine and polyamide-amine for dye separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 358, 130402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Guo, D.D.; Zhu, Y. Research progress in polyamide-amine dendrimer functionalized ionic separation media. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2025, 43, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, T.; Aggarwal, A.; Dasgupta, S.; Velachi, V.; Singha Deb, A.K.; Ali, S.M.; Maiti, P.K. Efficient Removal of Uranyl Ions Using PAMAM Dendrimer: Simulation and Experiment. Langmuir 2023, 39, 6794–6802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.X.; Song, Y.H.; Zhou, L. Facile synthesis of polyamidoamine dendrimer gel with multiple amine groups as a super adsorbent for highly efficient and selective removal of anionic dyes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 546, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lito, P.F.; Aniceto, J.P.S.; Silva, C.M. Removal of Anionic Pollutants from Waters and Wastewaters and Materials Perspective for Their Selective Sorption. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2012, 223, 6133–6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.X.; Zhou, J.Q.; Liang, Q.J.; Dai, X.M.; Yang, H.L.; Wan, M.J.; Ou, J.; Liao, M.F.; Wang, L.J. Comparing the separation performance of poly(ethyleneimine) embedded butyric and octanoic acid based chromatographic stationary phases. J. Chromatogr. A 2023, 1706, 464268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.H.; Hou, Y.J.; Zhang, F.F.; Shen, G.B.; Yang, B.C. A hyperbranched polyethylenimine functionalized stationary phase for hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 3633–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchukina, O.I.; Zatirakha, A.V.; Uzhel, A.S.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Shpigun, O.A. Novel polymer-based anion-exchangers with covalently-bonded functional layers of quaternized polyethyleneimine for ion chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 964, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Y.F.; Geng, H.L.; Zhang, F.F.; Li, Z.Y.; Yang, B.C. A polyethyleneimine-functionalized polymer substrate polar stationary phase. J. Chromatogr. A 2022, 1689, 463711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Q.; Li, Z.Y.; Zhang, F.F.; Yang, B.C.; Zhang, S.M. A novel hydrophilic polymer-based anion exchanger grafted by quaternized polyethyleneimine for ion chromatography. Talanta 2019, 197, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Lian, Z.Y.; Yan, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.D.; Han, L.F.; Yu, W.H.; Wang, G.Q.; Sun, Y.A.; Zhu, Y. Construction of polydopamine-polyethyleneimine composite coating on the surface of poly (styrene-divinylbenzene) microspheres followed by quaternization for preparation of anion exchangers. Microchem. J. 2023, 193, 109033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Yan, Y.Q.; Li, H.J.; Zhang, S.T.; Wang, G.Q.; Sun, Y.A.; Zhu, Y. Construction of amine-rich coating utilizing amine curing reaction of triglycidyl isocyanate with triethylenetetramine on the surface of poly(styrene-divinylbenzene) microspheres for preparation of anion exchange stationary phase. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, 202400369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Li, H.J.; Yan, Y.Q.; Zhang, Z.R.; Sun, Y.A.; Wang, G.Q. Preparation and Quaternization of Poly (Styrene-Divinylbenzene) Microspheres Loaded with p-Phenylenediamine-1,3,5-Triformylphloroglucinol Nanoparticles and Utilized as an Anion Exchanger. J. Sep. Sci. 2025, 48, e70137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.A.; Wang, C.W.; Li, Z.X.; Yu, W.H.; Liu, J.W.; Zhu, Y. Preparation and characterization of a latex-agglomerated anion exchange chromatographic stationary phase. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2018, 36, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.W.; Zhang, M.L.; Zhang, Q.D.; Mao, J.; Sun, Y.A.; Zhang, S.S.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, Y.L.; Zhang, J.X. Preparation and characterization of graphitic carbon-nitride nanosheets agglomerated poly (styrene-divinylbenzene) anion-exchange stationary phase for ion chromatography. Microchem. J. 2021, 164, 106023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Li, F.C.; Yao, M.D.; Qiu, T.; Jiang, W.H.; Fan, L.J. Atom transfer radical polymerization of glycidyl methacrylate followed by amination on the surface of monodispersed highly crosslinked polymer microspheres and the study of cation adsorption. React. Funct. Polym. 2014, 82, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbovskaia, A.V.; Kvachenok, I.K.; Stavrianidi, A.N.; Chernobrovkina, A.V.; Uzhel, A.S.; Shpigun, O.A. Polyelectrolyte-grafted mixed-mode stationary phases based on poly(styrene–divinylbenzene). Microchem. J. 2024, 199, 110075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, J.; Joerg, B.; Andre, L. Synthetic polymers with quaternary nitrogen atoms—Synthesis and structure of the most used type of cationic polyelectrolytes. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2010, 35, 511–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.H.; Liu, J.W.; Huang, Z.P.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhu, Y. Preparation of an agglomerated ion chromatographic stationary phase with 2,3-ionene and its application in SO42− analysis. Chin. J. Chromatogr. 2015, 33, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.M.; Wu, S.C.; Zhang, P.M.; Zhu, Y. Hydrothermal carbonaceous sphere based stationary phase for anion exchange chromatography. Talanta 2017, 163, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Lou, C.Y.; Zhu, Y.; Zhi, M.Y.; Zeng, X.Q. Hyperbranched anion exchangers prepared from thiol-ene modified polymeric substrates for suppressed ion chromatography. Talanta 2018, 184, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Cao, M.Y.; Lou, C.Y.; Wu, S.C.; Zhang, P.M.; Zhi, M.Y.; Zhu, Y. Graphene-coated polymeric anion exchangers for ion chromatography. Anal. Chim. Acta 2017, 970, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, P.; Huang, Z.P.; Zhu, Q.L.; Zhu, Z.Y.; Wang, L.L.; Zhu, Y. A novel composite stationary phase composed of polystyrene/divinybenzene beads and quaternized nanodiamond for anion exchange chromatography. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2019, 30, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.F.; Zhu, X.M.; Zhang, F.F.; Yang, B.C. A hyperbranched anion exchanger obtained by carboxylate surface modified polymer substrate for ion chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1746, 465792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, A.S.; Spiridonov, K.A.; Uzhel, A.S.; Smolenkov, A.D.; Chernobrovkina, A.; Zatirakha, A. Prospects of using hyperbranched stationary phase based on poly(styrene-divinylbenzene) in mixed-mode chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A 2021, 1642, 462010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.W.; Zhang, Y.D.; Yan, Y.Q.; Li, H.J.; Zhang, Q.C.; Wang, G.Q.; Sun, Y.A. Construction of poly (styrene-divinylbenzene)@tris(4-aminophenyl)amine-p-phthalaldehyde-triethylenetetramine core-shell microspheres for the preparation of ion chromatography stationary phase. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1739, 465549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzhel, A.S.; Gorbovskaia, A.V.; Talipova, I.I.; Chernobrovkina, A.V.; Pirogov, A.V. Polymer-based mixed-mode stationary phases with grafted polyelectrolytes containing iminodiacetic acid functionalities. J. Chromatogr. A 2025, 1756, 466062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Limpouchová, Z.; Procházka, K.; Raya, R.K.; Min, Y.G. Modeling the Phase Equilibria of Associating Polymers in Porous Media with Respect to Chromatographic Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Liu, L.J.; Jiang, B.H.; Zhao, H.F.; Zhao, L.M. Efficient adsorption of alginate oligosaccharides by ion exchange resin based on molecular simulation and experiments. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 317, 123942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aral, T.; Tunç, K.; Aral, H.; Dokdemir, M.; Sunkur, M.; Çolak, M. Tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane functionalized a novel stationary phase as a versatile mixed-mode HPLC platform for complex analyte separation and retention mechanism elucidation. Talanta 2025, 297, 128703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.Y.; Liu, L.J.; Zhang, X.X.; Zhu, Y.C.; Qiu, Y.J.; Zhao, L.M. Adsorption differences and mechanism of chitooligosaccharides with specific degree of polymerization on macroporous resins with different functional groups. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 115, 416–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Suspension Polymerization | Emulsion Polymerization | Soap-Free Emulsion Polymerization | Precipitation Polymerization | Dispersion Polymerization | Seed Polymerization | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction Medium | Water | Water | Water | Organic solvent or organic solvent/water mixture system | Organic solvent or organic solvent/water mixture system | Water or mixed solvent |

| Polymerization Mode | Homogeneous or heterogeneous | Heterogeneous (multiphase) | Heterogeneous (multiphase) | Heterogeneous | Initially homogeneous, then heterogeneous | Heterogeneous (biphase) |

| Dispersant | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Emulsifier | No | Yes | Trace or no | No | No | Partially yes |

| Particle Size Distribution | Wide | Narrow | Narrow | Relatively narrow | Narrow | Narrow |

| Advantages | Low cost, safe, easy to separate | Fast rate, eco-friendly | High product purity, feasible for structural design | High product purity | Simple process, wide monomer applicability | Large product particle size, low cost |

| Disadvantages | Polydisperse product, impure product | Too small product particle size, impure product | Too small product particle size | High solvent toxicity, low yield | Cannot synthesize high-cross-linking microspheres | High technical requirements, complicated operation |

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Anionic Emulsifiers | Sodium Fatty Acid, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate, Sodium Dodecyl Sulfonate, Sodium Dodecyl Benzene Sulfonate |

| Cationic Emulsifiers | Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide, Dodecyltrimethylammonium Chloride |

| Zwitterionic Emulsifiers | Amino Acid-Type |

| Nonionic Emulsifiers | Ethylene Oxide Polymer (Polyoxyethylene-Type), Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| Characteristics | Conventional Emulsion Polymerization | Soap-Free Emulsion Polymerization |

|---|---|---|

| Essential Relationship | Parent category, basic method | Subcategory, improved/specialized method |

| Stabilization System | Relies on externally added small-molecule emulsifiers (e.g., SDS); emulsifiers form micelles, which serve as the main polymerization sites | No conventional emulsifiers are added; stabilization is achieved using initiator fragments, hydrophilic comonomers, or ionic monomers themselves |

| Nucleation Mechanism | Mainly micellar nucleation | Mainly homogeneous nucleation or oligomer micellar nucleation |

| Latex Particle Characteristics | Broad particle size distribution; particle size adjustable by emulsifier dosage; high solid content (40–60%) | Typically monodisperse, large-sized (usually sub-μm scale) latex particles with clean surfaces; low solid content |

| Product Purity | Residual emulsifiers in the final polymer (hard to completely remove) may affect product performance (transparency, water resistance, adhesion) | “Clean” polymer latex particle surfaces (no small-molecule emulsifiers); high purity and better performance |

| Advantages | Mature technology; fast polymerization rate; high molecular weight; low system viscosity; easy heat dissipation; feasible for high-solid-content products | Excellent particle monodispersity; clear surface functional groups; high purity; better biocompatibility; more eco-friendly (reduces small-molecule chemicals) |

| Disadvantages | Residual emulsifiers impair performance and are hard to eliminate completely | Low solid content; relatively poor polymerization stability; stricter condition control requirements |

| Matrix | Preparation Method | APS (μm) | SSA (m2/g) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DVB-TMPT | Microporous Membrane Emulsification | 50–60 | / | [37] |

| PMMA | Microporous Membrane Emulsification | 0.25–1.60 | / | [34] |

| PVC, PLA, PS | Droplet Microfluidic Technology | 50–200 | / | [45] |

| PLGA-PEG, PLGA | Droplet Microfluidic Technology | 25.63, 27.89 | / | [47] |

| PS-DVB | Suspension Polymerization | 50–500 | 652 | [56] |

| DVB | Precipitation Polymerization | 2.3–4.0 | / | [71] |

| GMA-DVB | Precipitation Polymerization | 5.125 | 434.4 | [72] |

| PS-QDMBD | Dispersion Polymerization | 0.6–1.5 | / | [80] |

| GMA-DMB | Seed Polymerization | 8.20–11.61 | 353 | [96] |

| GMA-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 6.0 | 358, 371, 393 | [98] |

| PS-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 4.3 | 338.21 | [99] |

| PS-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 10 | / | [101] |

| HPMA-Cl-EGDMA | Seed Polymerization | 5 | 21.73 | [102] |

| PS-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 7 | 68.51 | [103] |

| GMA-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 5 | 353.06–379.86 | [104] |

| PS-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 5 | 78.34 | [105] |

| PS-GMA | Seed Polymerization | 6 | 110.72 | [106] |

| PS-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 6.6–7.2 | 76.143 | [107] |

| EVB-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 5.18 | 37.70 | [21] |

| EVB-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 5 | 625 | [20] |

| EVB-DVB | Seed Polymerization | 4.6 | 45 | [108] |

| Functional Group Structure | Chloromethylation Reagent | Amination Reagent | Analyte | Analysis Time 1 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aminomethyl formic acid/zinc oxide and tin tetrachloride | TMA | F−, Cl−, NO2−, HPO42−, SO42− | 30 min | [127] |

| Hydrochloric acid/polyformaldehyde/glacial acetic acid | TMA | F−, Cl−, Br−, NO3−, ClO3−, CrO4−, SO42−, S2O32− | 15 min | [128] |

| Glacial acetic acid/concentrated hydrochloric acid/formaldehyde | Diethylenetriamine chloride | F−, Cl−, Br−, NO3−, I−, SO42−, MoO42−, CrO4− | 24 min | [112] |

| Dimethylmethane/sulfonyl chloride, chlorosulfonic acid | Dimethylaminoethanol | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, HPO42−, SO42−, BrO3−, ClO2−, ClO3− | 33 min | [129] |

| Chlorosulfonic acid/glacial acetic acid/thionyl chloride | N,N-dimethylamine | F−, Cl−, NO3−, HPO42−, SO42− | 13 min | [114] |

| Trioxane/trimethylchlorosilane/chloroform/tin tetrachloride | N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-1,6-hexanediamine | myo-Inositol, Erythritol, Arabitol, Mannitol, Fucose, Arabinose, Glucose, Sorbose, Ribose, Lactose, Altrose, Raffinose, Maltose | 47 min | [130] |

| Hydrochloric acid/polyformaldehyde/glacial acetic acid | TMA | HCOO−, Cl−, Br−, NO3−, ClO3− | 15 min | [131] |

| Hydrochloric acid/polyformaldehyde/glacial acetic acid | TMA | N3−, HOCH2COO−, HCOO−, F−, Cl−, NO3− | 12 min | [132] |

| Hydrochloric acid/paraformaldehyde trimethylamine/tributylamine/tributylphosphine | TMA/tributylamine/tributylphosphine | Cl−, NO2−, Br−, SO42−, NO3−, S2O32− | 8 min | [133] |

| Functional Group Structure | Friedel–Crafts Alkylation Reagent | Amination Reagent | Analyte | Analysis Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-bromo-1-pentene/trifluoromethanesulfonic acid | DEMA | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, HPO42−, SO42− | 35 min | [134,135] |

| 5-bromo-1-pentene | N-methyldiethanolamine | Cl−, NO3−, HPO42−, SO42− | 8 min | [136] |

| Functional Group Structure | Friedel–Crafts Acylation | Reductive Amination Reagent | Alkylation Reagent | Analyte | Analysis Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dichloromethane, aluminum chloride, 4-chlorobutyryl chloride, 4-bromobutyryl chloride | DEMA | / | F−, Cl−, NO2−, SO42−, Br−, NO3−, HPO42− | 14 min | [135] |

| Dichloromethane, aluminum chloride, 3-chloropropionyl chloride, 4-chlorobutyryl chloride, 5-chlorobutyryl chloride | TMA | / | F−, Cl−, NO3−, HPO42−, SO42− | 45 min | [137] |

| Carbon disulfide, aluminum chloride, acetic anhydride | DMA, sodium cyanoboroh-ydride | Methyl iodide | F−, Cl−, HPO42−, SO42−, Br−, NO3− | 34 min | [138] |

| Carbon disulfide, aluminum chloride, acetic anhydride | DMA, sodium cyanoboroh-ydride | Epichlorohyd-rin | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, HPO42−, SO42− | 30 min | [138] |

| Carbon disulfide, aluminum chloride, acetic anhydride | MA, sodium cyanoboroh-ydride | Epichlorohyd-rin | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42− | 8 min | [138] |

| Acetic anhydride | MA, DMA | Epichlorohyd-rin | F−, HCOO−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, HPO42−, SO42− | 34 min | [139] |

| Acetic anhydride, aluminum chloride | MA, sodium cyanoboroh-ydride | GTMA, (3-chloro-2-hydroxyprop-yl) trimethyl CTMA | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3− | 8 min | [140] |

| Acetic anhydride, aluminum chloride | DMA, sodium cyanoboroh-ydride | 1,4-BDDGE TMA | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3− | 50 min | [140] |

| Acetic anhydride, aluminum chloride | MA 1,4-BDDGE | TMA | F−, HCOO−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42− | 8 min | [140,141] |

| DMEA | F−, HCOO−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42− | 12 min | ||||

| MDEA | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42− | 11 min | ||||

| TEA | F−, HCOO−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42− | 11 min | ||||

| Acetic anhydride, aluminum chloride | MA RDGE | TMA | F−, HCOO−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42− | 17 min | [140,141] |

| DMEA | ||||||

| MDEA | ||||||

| TEA |

| Functional Group Structure | Nitration | The Generation of Amino Groups | Introduced Quaternary Ammonium Salt Groups | Analyte | Analysis Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitric acid, sulfuric acid | Tin dichloride, hydrochloric acid | Methyl iodide | F−, Cl−, HPO42−, SO42− | 13 min | [143] |

| Nitric acid, sulfuric acid | Tin dichloride, hydrochloric acid | 1,6-dibromohexane, TMA | F−, Cl−, Br−, HPO42−, SO42− | 31 min | [143] |

| Nitric acid, sulfuric acid | Granular metallic tin, hydrochloric acid | 1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidine | Glucose, Turanose, Maltose, Panose, Maltotriose | 9 min | [142] |

| Chemical Derivatization Method | Surface Grafting Method | |

|---|---|---|

| Action Level & Essence | Atomic/functional group level: Modify atoms or functional groups on the matrix backbone directly via small-molecule organic reactions (e.g., sulfonation, chloromethylation). | Polymer chain/nanostructure level: Connect pre-synthesized or in situ grown polymer chains/functional macromolecules to the matrix surface via covalent bonds. |

| Functional Layer Structure | No independent “layer” concept: Functional groups are directly bonded to the matrix backbone, serving as an integral part of the matrix. | Clear “functional layer”: An independent, thickness-controllable polymer brush, dendritic macromolecule or nano-coating is formed on the matrix surface. |

| Impact on Matrix Bulk | Deep impact: Vigorous chemical reactions (strong acids, strong oxidants) may damage the original cross-linking structure, pore size distribution and mechanical strength of the matrix. | Mild impact: Reactions are usually gentle and occur only on the surface, causing little damage to the matrix bulk structure (pores, cross-links). |

| Controllability & Precision | Low: Reaction sites (e.g., benzene rings of PS-DVB) are randomly distributed; precise control of functional group density, position and chain length is difficult, and batch reproducibility is challenging. | High: Active/controllable polymerization (e.g., ATRP) can be used to precisely regulate the length, density, composition and structure of graft chains, enabling molecular-level designability. |

| Design Philosophy & Trend | “Terminal” modification: One-step reaction permanently alters the matrix chemistry, making iteration or multifunctionalization difficult. It is a classic but gradually replaced strategy. | “Platform-based” construction: First build an active platform (e.g., initiator layer) on the surface; then, “grow” the functional layer on it. It facilitates multifunctional, multi-level, iterative precision design, representing the modern mainstream and frontier direction. |

| Matrix | Functionalization Method | Analyte | Analysis Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS-DVB | Surface grafting | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42− | 15 min | [186] |

| PS-DVB | Surface grafting | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, SO42−, NO3−, HPO42− | 12 min | [188] |

| PS-DVB | Surface grafting | F−, Cl−, NO3−, PO43−, SO42−, I−, SCN−, S2O32− | 11 min | [124] |

| GMA-DVB | Surface grafting | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42−, HPO42− | 16 min | [172] |

| PS-DVB | Latex agglomeration | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, PO43−, SO42− | 8 min | [181] |

| PS-DVB | Latex agglomeration | F−, Cl−, ClO2−, NO2−, BrO3−, Br−, NO3−, ClO3− | 12 min | [189] |

| PS-DVB | Hyperbranching | F−, HCOO−, Cl−, BrO3−, NO2−, Br−, SO42−, NO3− | 15 min | [120] |

| PS-DVB | Hyperbranching | F−, Cl−, NO2−, Br−, NO3−, SO42−, PO43− | 7 min | [123] |

| EVB-DVB | Hyperbranching | F−, Cl−, Br−, NO2−, ClO2−, BrO3−, ClO3−, NO3− | 13 min | [21] |

| EVB-DVB | Hyperbranching | F−, HCOO−, Cl−, NO2−, SO42−, Br−, NO3−, ClO3−, PO43− | 17 min | [183] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, H.; Xu, J.; Shen, Y.; Cheng, S.; Sun, Y.; Shuang, C.; Li, A. Preparation and Research Progress of Polymer-Based Anion Exchange Chromatography Stationary Phases. Polymers 2026, 18, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030389

Liu H, Xu J, Shen Y, Cheng S, Sun Y, Shuang C, Li A. Preparation and Research Progress of Polymer-Based Anion Exchange Chromatography Stationary Phases. Polymers. 2026; 18(3):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030389

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Haolin, Jingwei Xu, Yifan Shen, Shi Cheng, Yangyang Sun, Chendong Shuang, and Aimin Li. 2026. "Preparation and Research Progress of Polymer-Based Anion Exchange Chromatography Stationary Phases" Polymers 18, no. 3: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030389

APA StyleLiu, H., Xu, J., Shen, Y., Cheng, S., Sun, Y., Shuang, C., & Li, A. (2026). Preparation and Research Progress of Polymer-Based Anion Exchange Chromatography Stationary Phases. Polymers, 18(3), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030389