Exploring Lemon Industry By-Products for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production: Comparative Performances of Haloferax mediterranei PHBV vs. Commercial PHBV

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and Inoculum Preparation

2.2. Determination of Cell Growth

2.3. Agrifood Residues as a Carbon Source for PHBV Production

2.3.1. First Screening (Lemon By-Product Concentration)

2.3.2. Second Screening (Inoculum Percentage Scanning)

2.3.3. Carbon–Nitrogen–Phosphorus (C:N:P) Ratio Experiments

2.4. Scaling Up the Fermentation

2.5. PHBV Extraction

2.6. PHBV Characterisation

2.6.1. Materials Used

2.6.2. Characterisation of PHBV by Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

2.6.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

2.6.4. Melt Flow Rate (MFR)

2.7. PHBV Extrusion and Comparison with a Commercial PHBV

2.7.1. PHBV Extrusion

2.7.2. Characterisation of PHBV by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.7.3. Raman Spectroscopy

2.7.4. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

2.7.5. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

3. Results

3.1. Agrifood Residues as a Carbon Source for PHBV Production

3.1.1. First Screening: Effect of Lemon By-Product Concentration on Microbial Growth and PHBV Production

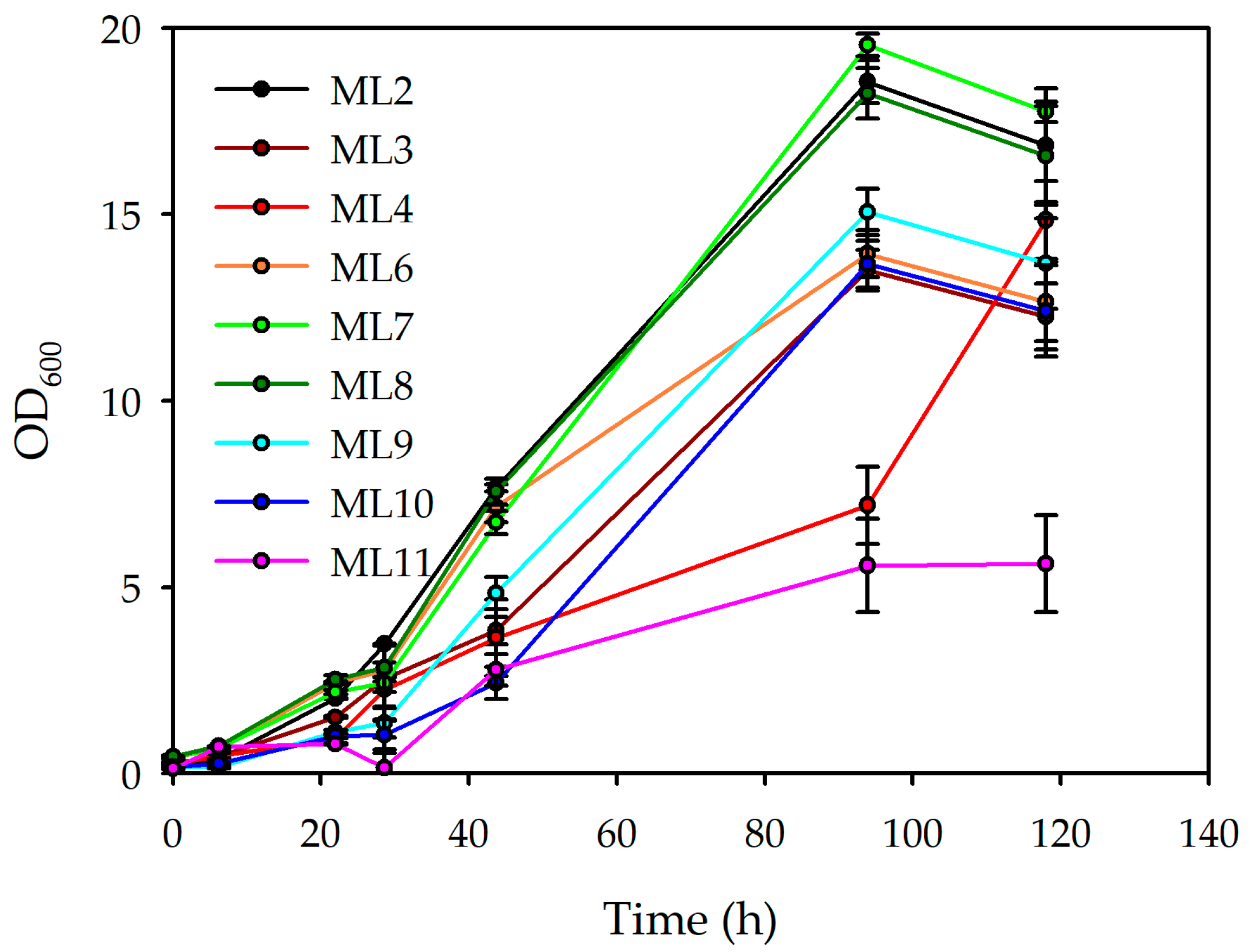

3.1.2. Second Screening: Impact of Inoculum and Lemon By-Product Concentration on Microbial Growth and PHBV Production

3.1.3. C:N:P Ratio Experiments: Effect of Nutrient Ratios (C:N and C:P) and Medium Composition on Microbial Growth and PHBV Production

3.2. Lemon By-Product Scaleup

3.3. PHBV Pure Characterisation

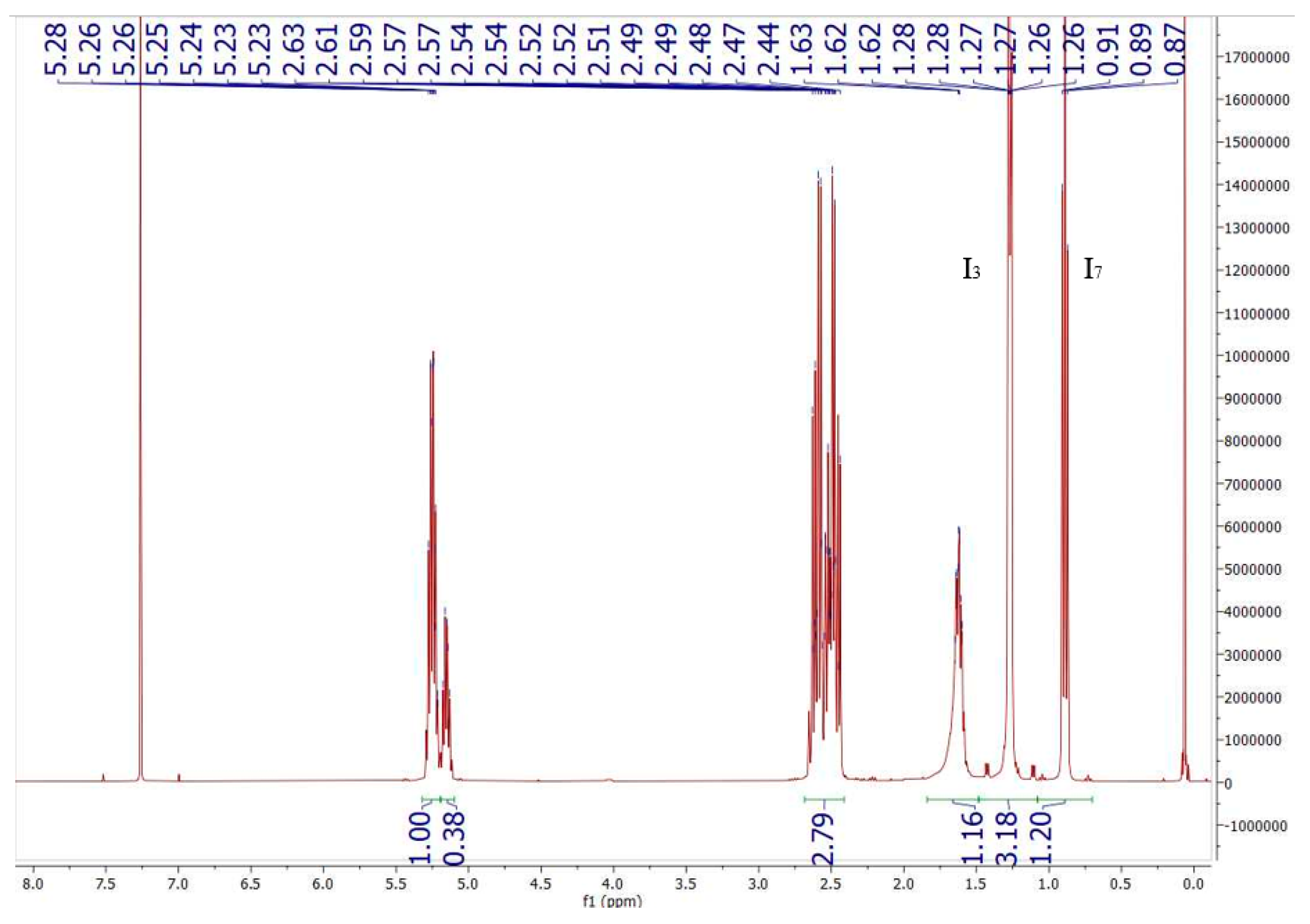

3.3.1. NMR

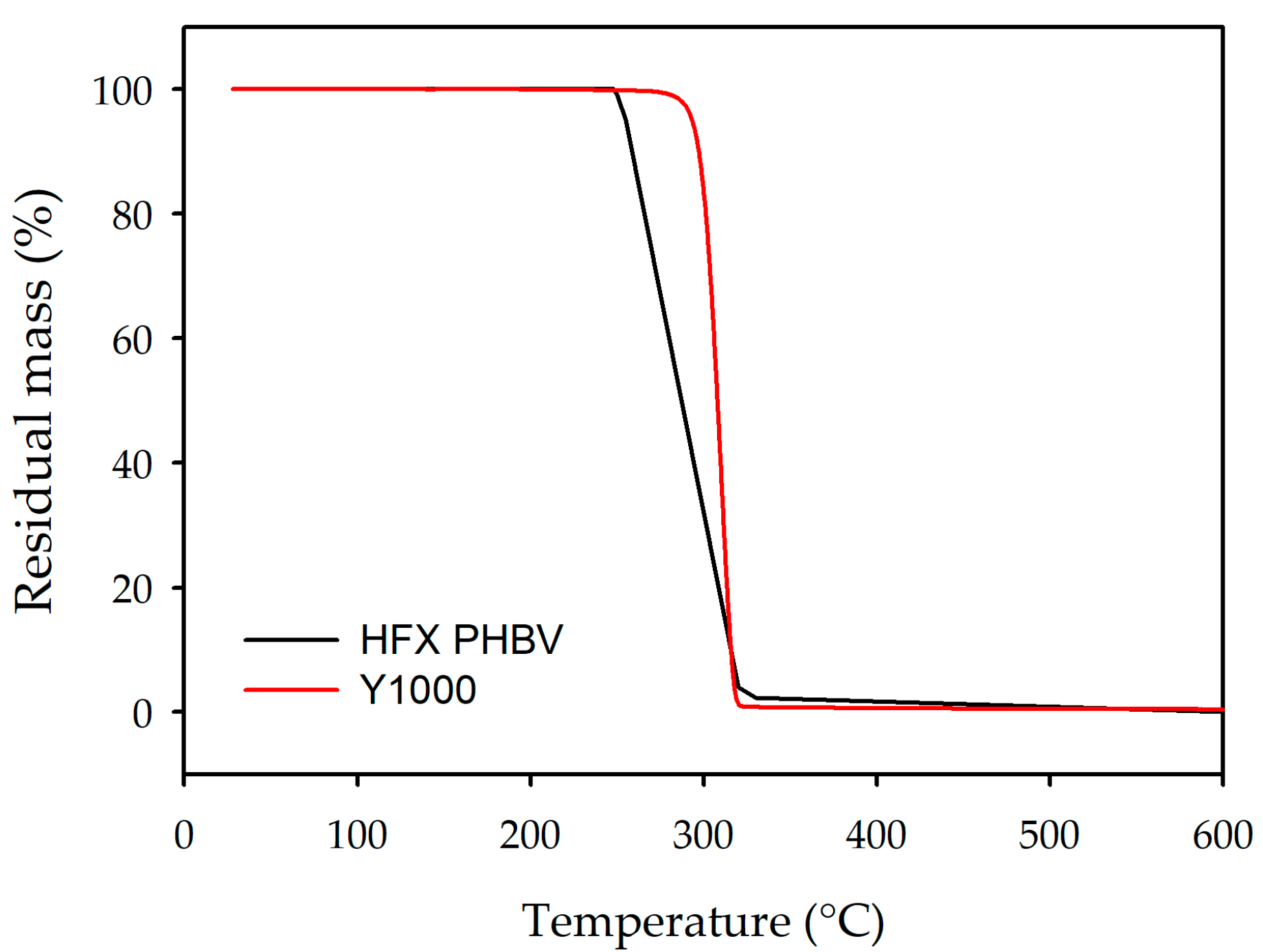

3.3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis

3.3.3. Melting Flow Rate

3.4. PHBV Blend Characterisation

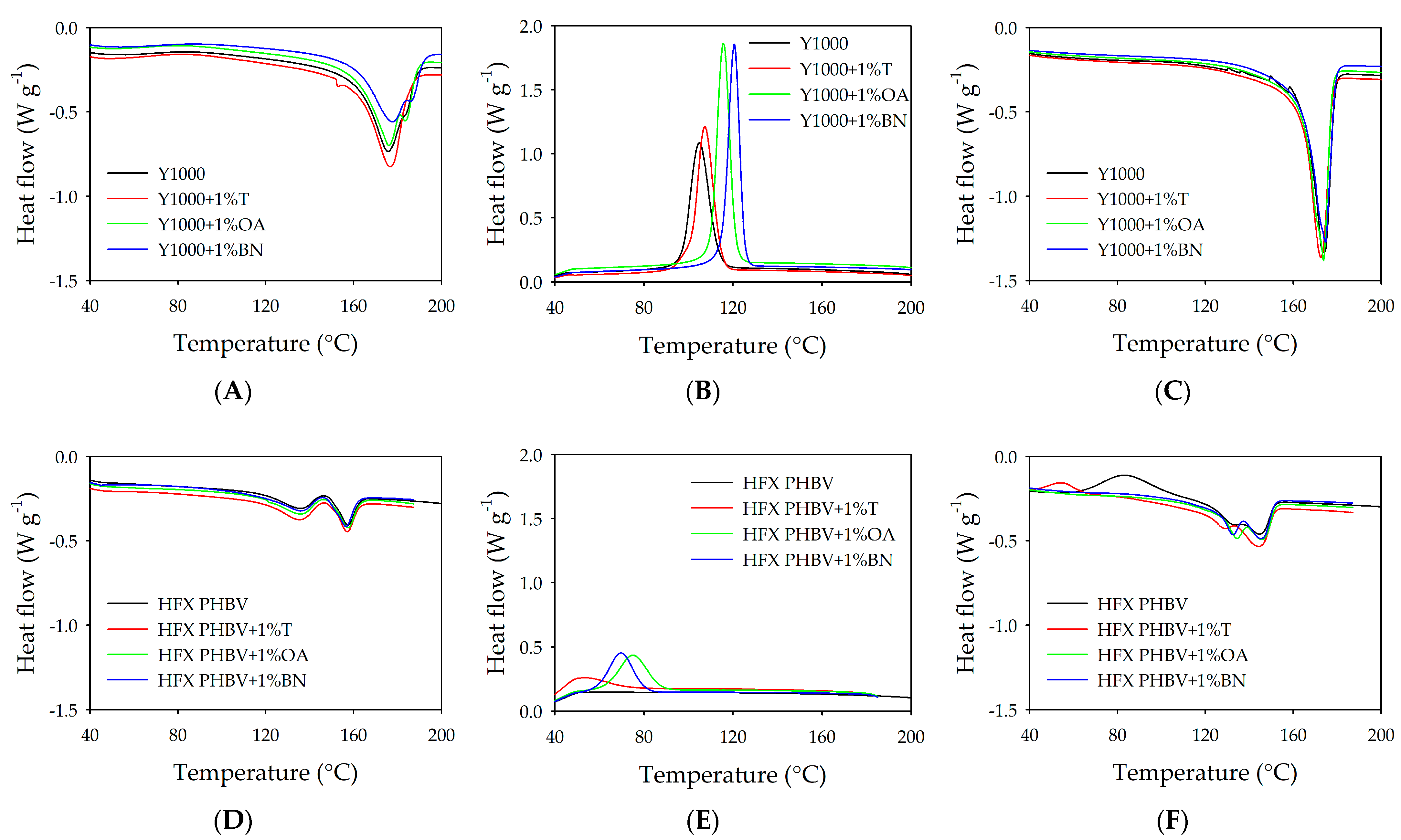

3.4.1. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

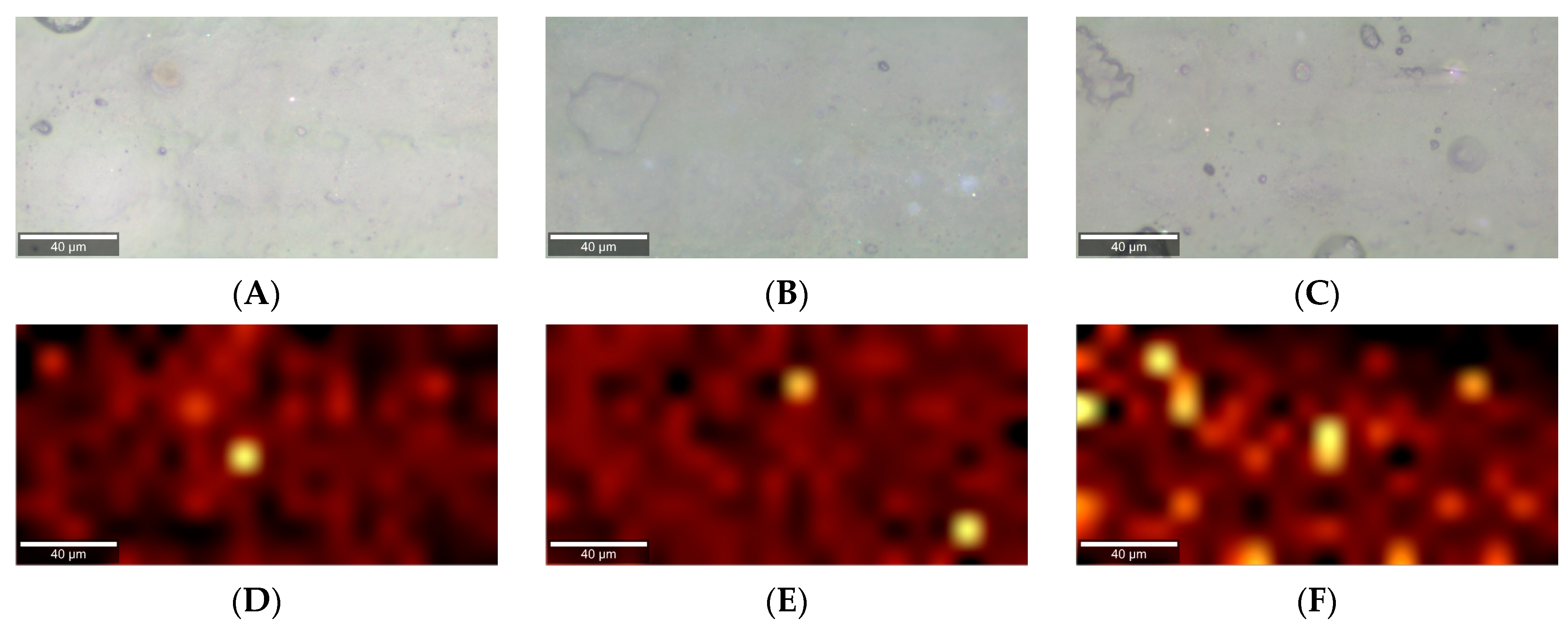

3.4.2. Raman Spectroscopy

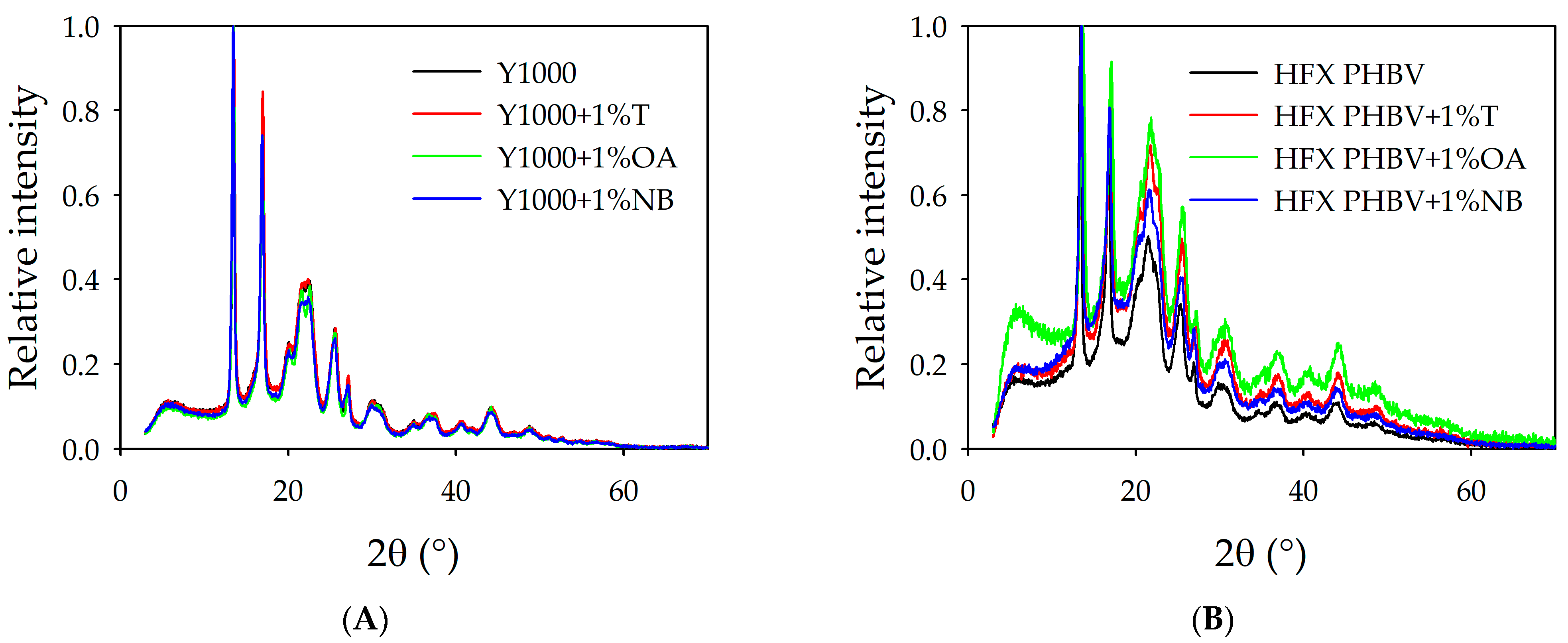

3.4.3. X-Ray Diffraction

3.4.4. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3HB | 3-hydroxybutyrate |

| 3HV | 3-hydroxyvalerate |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| BN | Boron nitride |

| C:N | Carbon–nitrogen |

| C:N:P | Carbon–nitrogen–phosphorus |

| C:P | Carbon–phosphorus |

| CA | Cyanuric acid |

| CaCl2 | Calcium chloride |

| CDCl3 | Deuterated chloroform |

| CTNC | Centro Tecnológico Nacional de la Conserva y Alimentación |

| DCW | Dry cell weight |

| DMA | Dynamic mechanical analysis |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| Dt | Doubling time |

| FeCl3 | Iron (III) chloride |

| H. mediterranei | Haloferax mediterranei |

| H2O | Dihydrogen monoxide |

| HFX PHBV | Haloferax mediterranei Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) |

| HFX PHBV + 1% T | Haloferax mediterranei Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) with one percent of theobromine as the nucleating agent |

| HFX PHBV + 1% OA | Haloferax mediterranei Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) with one percent of orotic acid as the nucleating agent |

| HFX PHBV + 1% BN | Haloferax mediterranei Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) with one percent of boron nitride as the nucleating agent |

| KCl | Potassium chloride |

| KH2PO4 | Monopotassium phosphate |

| KNO3 | Potassium nitrate |

| MFR | Melt flow rate |

| MgCl2 | Magnesium chloride |

| MgSO4 | Magnesium sulphate |

| NaBr | Sodium bromide |

| NaCl | Sodium chloride |

| NaH2PO4 | Monosodium phosphate |

| NaHCO3 | Sodium bicarbonate |

| NMR | Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| OA | Orotic acid |

| OD600 | Optical density at 600 nm |

| PHA | Polyhydroxyalkanoate |

| PHB | Poly 3-hydroxybutyrate |

| PHBHHx | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) |

| PHBV | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) |

| T | Theobromine |

| Tc | Peak temperature of crystallisation |

| TGA | Thermal gravimetric analysis |

| Tm | Peak temperature of melting |

| g/g | Gram per gram |

| v/v | Volume per volume |

| w/v | Weight per volume |

| Y1000 + 1% T | Y1000 polymer with one percent of theobromine as the nucleating agent |

| Y1000 + 1% OA | Y1000 polymer with one percent of orotic acid as the nucleating agent |

| Y1000 + 1% BN | Y1000 polymer with one percent of boron nitride as the nucleating agent |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| ΔH0 | Enthalpy of melting of 100% crystalline material |

| ΔHc | Enthalpy of crystallisation |

| ΔHf | Enthaply of melting |

References

- Paritosh, K.; Kushwaha, S.K.; Yadav, M.; Pareek, N.; Chawade, A.; Vivekanand, V. Food Waste to Energy: An Overview of Sustainable Approaches for Food Waste Management and Nutrient Recycling. Biomed. Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 2370927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atiwesh, G.; Mikhael, A.; Parrish, C.C.; Banoub, J.; Le, T.A.T. Environmental Impact of Bioplastic Use: A Review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbery, M.; O’Connor, W.; Palanisami, T. Trophic Transfer of Microplastics and Mixed Contaminants in the Marine Food Web and Implications for Human Health. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, A.A.; Dixon, S.J. Microplastics: An Introduction to Environmental Transport Processes. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2018, 5, e1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binelli, A.; Della Torre, C.; Nigro, L.; Riccardi, N.; Magni, S. A Realistic Approach for the Assessment of Plastic Contamination and Its Ecotoxicological Consequences: A Case Study in the Metropolitan City of Milan (N. Italy). Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, K.; Green, D. The Potential Effects of Microplastics on Human Health: What Is Known and What Is Unknown. Ambio 2022, 51, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, G.V.B.; Justino, A.K.S.; Eduardo, L.N.; Lenoble, V.; Fauvelle, V.; Schmidt, N.; Junior, T.V.; Frédou, T.; Lucena-Frédou, F. Plastic in the Inferno: Microplastic Contamination in Deep-Sea Cephalopods (Vampyroteuthis infernalis and Abralia veranyi) from the Southwestern Atlantic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 174, 113309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, I.; Amezcua, F.; Rivera, J.M.; Green-Ruiz, C.; de Jesus Piñón-Colin, T.; Wakida, F. First Report of Plastic Contamination in Batoids: Plastic Ingestion by Haller’s Round Ray (Urobatis halleri) in the Gulf of California. Environ. Res. 2022, 211, 113077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghighi, E.; Shah, T.; Chia, R.W.; Lee, J.Y.; Shang, J.; Rodríguez-Seijo, A. The Forgotten Impacts of Plastic Contamination on Terrestrial Micro- and Mesofauna: A Call for Research. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S.L.; Kelly, F.J. Plastic and Human Health: A Micro Issue? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 6634–6647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amobonye, A.; Bhagwat, P.; Singh, S.; Pillai, S. Plastic Biodegradation: Frontline Microbes and Their Enzymes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 759, 143536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.J.; Cui, Y.W.; Chen, S.; Wang, X. Effects of Magnetic Field Exposure Patterns on Polyhydroxyalkanoates Synthesis by Haloferax mediterranei at Extreme Hypersaline Context: Carbon Distribution and Salt Tolerance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; An, Z.; Wang, J.; Lansing, S.; Kumar Amradi, N.; Sazzadul Haque, M.; Wang, Z.W. Long-Term Effects of Cycle Time and Volume Exchange Ratio on Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) Production from Food Waste Digestate by Haloferax mediterranei Cultivated in Sequencing Batch Reactors for 450 Days. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 416, 131771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, A.; Zuber, M.; Zia, K.M.; Noreen, A.; Anjum, M.N.; Tabasum, S. Microbial Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) and Its Copolymers: A Review of Recent Advancements. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 89, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avella, M.; Martuscelli, E.; Raimo, M. Review Properties of Blends and Composites Based on Poly(3-Hydroxy)Butyrate (PHB) and Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) Copolymers. J. Mater. Sci. 2000, 35, 523–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loo, C.Y.; Sudesh, K. Biosynthesis and Native Granule Characteristics of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) in Delftia acidovorans. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2007, 40, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M. Polyhydroxyalkanoate Biosynthesis at the Edge of Water Activitiy-Haloarchaea as Biopolyester Factories. Bioengineering 2019, 6, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaali, Z.; Naghavi, M.R. Biotechnological Approaches for Enhancing Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) Production: Current and Future Perspectives. Curr. Microbiol. 2023, 80, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.W.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ding, Y.W.; Dao, J.W.; Li, H.R.; Ma, X.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Liu, J.X.; Mi, C.H.; et al. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: The Natural Biopolyester for Future Medical Innovations. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 6013–6034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cánovas, V.; Garcia-Chumillas, S.; Monzó, F.; Simó-Cabrera, L.; Fernándezayuso, C.; Pire, C.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Analysis of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Granules in Haloferax mediterranei by Double-fluorescence Staining with Nile Red and SYBR Green by Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy. Polymers 2021, 13, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Cabrera, L.; García-Chumillas, S.; Benitez-Benitez, S.J.; Cánovas, V.; Monzó, F.; Pire, C.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Production of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV) by Haloferax mediterranei Using Candy Industry Waste as Raw Materials. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simó-Cabrera, L.; García-Chumillas, S.; Hagagy, N.; Saddiq, A.; Tag, H.; Selim, S.; Abdelgawad, H.; Agüero, A.A.; Sánchez, F.M.; Cánovas, V.; et al. Haloarchaea as Cell Factories to Produce Bioplastics. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Abdallah, M.; Saadaoui, I.; Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Zouari, N.; Hahladakis, J.N.; Chamkha, M.; Sayadi, S. Advances in Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Production from Renewable Waste Materials Using Halophilic Microorganisms: A Comprehensive Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 963, 178452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramvash, A.; Hajizadeh-Turchi, S.; Moazzeni-zavareh, F.; Gholami-Banadkuki, N.; Malek-sabet, N.; Akbari-Shahabi, Z. Effective Enhancement of Hydroxyvalerate Content of PHBV in Cupriavidus necator and Its Characterization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 87, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, T.D.; Ghosh, S.; Agarwal, A.; Patel, S.K.S.; Tripathi, A.D.; Mahato, D.K.; Kumar, P.; Slama, P.; Pavlik, A.; Haque, S. Production, Optimization, Scale up and Characterization of Polyhydoxyalkanoates Copolymers Utilizing Dairy Processing Waste. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigouin, C.; Lajus, S.; Ocando, C.; Borsenberger, V.; Nicaud, J.M.; Marty, A.; Avérous, L.; Bordes, F. Production and Characterization of Two Medium-Chain-Length Polydroxyalkanoates by Engineered Strains of Yarrowia Lipolytica. Microb. Cell Fact. 2019, 18, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurian, N.S.; Das, B. Comparative Analysis of Various Extraction Processes Based on Economy, Eco-Friendly, Purity and Recovery of Polyhydroxyalkanoate: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 183, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toh, P.S.Y.; Jau, M.-H.; Yew, S.-P.; Abed, R.M.M.; Sudesh, K. Comparison of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Biosynthesis, Mobilization and the Effects on Cellular Morphology in Spirulina platensis and Synechocystis sp. Uniwge. Trop. Life Sci. Res. 2008, 19, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Khomlaem, C.; Aloui, H.; Kim, B.S. Biosynthesis of Polyhydroxyalkanoates from Defatted chlorella Biomass as an Inexpensive Substrate. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M. Recycling of Waste Streams of the Biotechnological Poly(Hydroxyalkanoate) Production by Haloferax mediterranei on Whey. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 2015, 370164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Gnaim, R.; Greiserman, S.; Fadeev, L.; Gozin, M.; Golberg, A. Macroalgal Biomass Subcritical Hydrolysates for the Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) by Haloferax mediterranei. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 271, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M.; Rittmann, S.K.M.R. Haloarchaea as Emerging Big Players in Future Polyhydroxyalkanoate Bioproduction: Review of Trends and Perspectives. Curr. Res. Biotechnol. 2022, 4, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamplod, T.; Wongsirichot, P.; Winterburn, J. Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates from Hydrolysed Rapeseed Meal by Haloferax mediterranei. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 386, 129541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barham, P.J. Nucleation Behaviour of Poly-3-Hyd Roxy-Butyrate. J. Mater. Sci. 1984, 19, 3826–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bledsoe, J.C.; Crane, G.H.; Locklin, J.J. Beyond Lattice Matching: The Role of Hydrogen Bonding in Epitaxial Nucleation of Poly(Hydroxyalkanoates) by Methylxanthines. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 3858–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquel, N.; Tajima, K.; Nakamura, N.; Miyagawa, T.; Pan, P.; Inoue, Y. Effect of Orotic Acid as a Nucleating Agent on the Crystallisation of Bacterial Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyhexanoate) Copolymers. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 114, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloembergen, S.; Holden, D.A.; Hamer, G.K.; Bluhm, T.L.; Marchessault, R.H. Studies of Composition and Crystallinity of Bacterial Poly(/3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-/3-Hydroxyvalerate). Macromolecules 1986, 19, 2865–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; Pan, J.; Xu, K. Miscibility, Crystallisation Kinetics, and Mechanical Properties of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate)(PHBV)/Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4- Hydroxybutyrate)(P3/4HB) Blends. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 117, 838–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srithep, Y.; Nealey, P.; Turng, L.S. Effects of Annealing Time and Temperature on the Crystallinity and Heat Resistance Behavior of Injection-Molded Poly(Lactic Acid). Polym. Eng. Sci. 2013, 53, 580–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galego, N.; Rozsa, C.; Fung, J.; Santo Tomás, J. Characterization and Application of Poly(β-Hydroxyalkanoates) Family as Composite Biomaterials. Polym. Test. 2000, 19, 485–492. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Rubio, P.M.; Avilés, M.D.; Pamies, R.; Benítez-Benítez, S.J.; Arribas, A.; Carrión-Vilches, F.J.; Bermúdez, M.D. In-Depth Analysis of the Complex Interactions Induced by Nanolayered Additives in PHBV Nanocomposites. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2024, 309, 2400016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melanie, S.; Winterburn, J.B.; Devianto, H. Production of Biopolymer Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) by Extreme Halophilic Marine Archaea Haloferax mediterranei in Medium with Varying Phosphorus Concentration. J. Eng. Technol. Sci. 2018, 50, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rubio, P.-M.; Avilés, M.-D.; Carrión-Vilches, F.-J.; Pamies, R. The Complex Crystalline Behavior and Tribological Performance of Polyhydroxyalkanoates. Polymer 2025, 340, 129207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunioka, M.; Doi, Y. Thermal Degradation of Microbial Copolyesters: Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) and Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-4-Hydroxybutyrate). Macromolecules 1990, 23, 1933–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshie, N.; Saito, M.; Inoue, Y. Structural Transition of Lamella Crystals in a Isomorphous Copolymer, Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate). Macromolecules 2001, 34, 8953–8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, S.F.; Wu, T.M.; Liao, C.S. Nonisothermal Crystallisation Behavior and Crystalline Structure of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate)/Layered Double Hydroxide Nanocomposites. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 2007, 45, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Y.; Fang, C.; Shi, D.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Coupling Effects of Boron Nitride and Heat Treatment on Crystallisation, Mechanical Properties of Poly (3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV). Polymer 2022, 252, 124967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.J.; Yang, H.L.; Wang, Z.; Dong, L.S.; Liu, J.J. Effect of Nucleating Agents on the Crystallisation of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2002, 86, 2145–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Lv, Y.; Duan, T.; Zhu, M.; Li, Y.; Miao, W.; Wang, Z. In-Situ Investigation of Multiple Endothermic Peaks in Isomorphous Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) with Low HV Content by Synchrotron Radiation. Polymer 2019, 169, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluhm, T.L.; Hamer, G.K.; Marchessault, R.H.; Fyfe, C.A.; Veregin, R.P. Isodimorphism in bacterial poly(β-hydroxybutyrate-co-β-hydroxyvalerate). Macromolecules 1986, 19, 2871–2876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekaran, S.; Sankari, G.; Ponnusamy, S. Vibrational Spectral Investigation on Xanthine and Its Derivatives—Theophylline, Caffeine and Theobromine. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2005, 61, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rojek, B.; Plenis, A. TGA, FTIR and Raman Spectroscopy Supported by Statistical Multivariate Methods in the Detection of Incompatibility in Mixtures of Theobromine with Excipients. In Prime Archives in Molecular Sciences; Vide Leaf: Hyderabad, India, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ucun, F.; Saǧlam, A.; Güçlü, V. Molecular Structures and Vibrational Frequencies of Xanthine and Its Methyl Derivatives (Caffeine and Theobromine) by Ab Initio Hartree-Fock and Density Functional Theory Calculations. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2007, 67, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, D.E.; Nartowski, K.P.; Khimyak, Y.Z.; Morris, K.R.; Byrn, S.R.; Griesser, U.J. Structural Properties, Order-Disorder Phenomena, and Phase Stability of Orotic Acid Crystal Forms. Mol. Pharm. 2016, 13, 1012–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernanz, A.; Billes, F.; Bratu, I.; Navarro, R. Vibrational Analysis and Spectra of Orotic Acid. Biopolym. Biospectroscopy Sect. 2000, 57, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenal, R.; Ferrari, A.C.; Reich, S.; Wirtz, L.; Mevellec, J.Y.; Lefrant, S.; Rubio, A.; Loiseau, A. Raman Spectroscopy of Single-Wall Boron Nitride Nanotubes. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 1812–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, S.; Ferrari, A.C.; Arenal, R.; Loiseau, A.; Bello, I.; Robertson, J. Resonant Raman Scattering in Cubic and Hexagonal Boron Nitride. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2005, 71, 205201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokouchi, M.; Chatani, Y.; Tadokoro, H.; Teranishi, K.; Tani, H. Structural Studies of Polyesters: 5. Molecular and Crystal Structures of Optically Active and Racemic Poly(p-Hyd Roxybutyrate). Polymer 1973, 14, 267–272. [Google Scholar]

- Portalone, G. Redetermination of Orotic Acid Monohydrate. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Struct. Rep. Online 2008, 64, o656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai, W.; He, Y.; Inoue, Y. Fast Crystallisation of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) and Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) with Talc and Boron Nitride as Nucleating Agents. Polym. Int. 2005, 54, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legras, R.; Mercier, J.P.; Nield, E. Polymer Crystallisation by Chemical Nucleation. Nature 1983, 304, 432–434. [Google Scholar]

- Libster, D.; Aserin, A.; Garti, N. Advanced Nucleating Agents for Polypropylene. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2007, 18, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, K.; Watanabe, K.; Urushihara, T.; Toda, A.; Hikosaka, M. Role of Epitaxy of Nucleating Agent (NA) in Nucleation Mechanism of Polymers. Polymer 2007, 48, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquel, N.; Tajima, K.; Nakamura, N.; Kawachi, H.; Pan, P.; Inoue, Y. Nucleation Mechanism of Polyhydroxybutyrate and Poly(Hydroxybutyrate-Co- Hydroxyhexanoate) Crystallized by Orotic Acid as a Nucleating Agent. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 115, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.; Frank, C.W. Comparison of Anhydrous and Monohydrated Forms of Orotic Acid as Crystal Nucleating Agents for Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate). Polymer 2014, 55, 6364–6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doineau, E.; Perdrier, C.; Allayaud, F.; Blanchet, E.; Preziosi-belloy, L.; Grousseau, E.; Gontard, N.; Angellier-Coussy, H. Designing Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate-Co-3-Hydroxyvalerate) P(3HB-Co-3HV) Films with Tailored Mechanical Properties. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raho, S.; Carofiglio, V.E.; Montemurro, M.; Miceli, V.; Centrone, D.; Stufano, P.; Schioppa, M.; Pontonio, E.; Rizzello, C.G. Production of the Polyhydroxyalkanoate PHBV from Ricotta Cheese Exhausted Whey by Haloferax mediterranei Fermentation. Foods 2020, 9, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafadi, D.; Al-Mashaqbeh, O. A One-Stage Cultivation Process for the Production of Poly-3-(Hydroxybutyrate-Co-Hydroxyvalerate) from Olive Mill Wastewater by Haloferax mediterranei. N. Biotechnol. 2017, 34, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montemurro, M.; Salvatori, G.; Alfano, S.; Martinelli, A.; Verni, M.; Pontonio, E.; Villano, M.; Rizzello, C.G. Exploitation of Wasted Bread as Substrate for Polyhydroxyalkanoates Production through the Use of Haloferax mediterranei and Seawater. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1000962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, S.; Wu, Y.; Liu, R.; Jia, H.; Qiu, Y.; Jiang, M.; Ma, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Study on the Production of High 3HV Content PHBV via an Open Fermentation with Waste Silkworm Excrement as the Carbon Source by the Haloarchaeon Haloferax Mediterranei. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 981605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsafadi, D.; Ibrahim, M.I.; Alamry, K.A.; Hussein, M.A.; Mansour, A. Utilizing the Crop Waste of Date Palm Fruit to Biosynthesize Polyhydroxyalkanoate Bioplastics with Favorable Properties. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, M.; Atlić, A.; Gonzalez-Garcia, Y.; Kutschera, C.; Braunegg, G. Polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) Biosynthesis from Whey Lactose. In Macromolecular Symposia; WILEY-VCH Verlag: Weinheim, Germany, 2008; Volume 272, pp. 87–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mozejko-Ciesielska, J.; Moraczewski, K.; Czaplicki, S.; Singh, V. Production and Characterization of Polyhydroxyalkanoates by Halomonas alkaliantarctica Utilizing Dairy Waste as Feedstock. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 22289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozejko-Ciesielska, J.; Marciniak, P.; Moraczewski, K.; Rytlewski, P.; Czaplicki, S.; Zadernowska, A. Cheese Whey Mother Liquor as Dairy Waste with Potential Value for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production by Extremophilic Paracoccus homiensis. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2022, 33, e00449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Concentration (g/L) |

|---|---|

| Fructose | 26.67 ± 0.17 |

| Glucose | 43.60 ± 0.84 |

| Maltose | 9.20 ± 0.07 |

| Sucrose | 9.87 ± 0.70 |

| Condition | Lemon By-Products (v/v) | % Inoculum (v/v) |

|---|---|---|

| ML2 | 11.0 | 5.0 |

| ML3 | 14.0 | 5.0 |

| ML4 | 17.5 | 5.0 |

| ML6 | 11.0 | 10.0 |

| ML7 | 14.0 | 10.0 |

| ML8 | 17.5 | 10.0 |

| ML9 | 11.0 | 2.5 |

| ML10 | 14.0 | 2.5 |

| ML11 | 17.5 | 2.5 |

| Condition | Culture Medium | Lemon By-Products (v/v) | C:N (g/g) | C:P (g/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML2 | Minimal | 11.0 | 7.17 | 40.01 |

| EL2 | Enriched | 11.0 | 5.68 | 174.48 |

| ML2.1 | Minimal | 11.0 | 7.17 | 200.03 |

| ML3 | Minimal | 14.0 | 9.12 | 50.92 |

| EL3 | Enriched | 14.0 | 7.22 | 222.07 |

| ML3.1 | Minimal | 14.0 | 9.12 | 254.59 |

| Polymer | Zone 1 (°C) | Zone 2 (°C) | Zone 3 (°C) | Zone 4 (°C) | Die (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1000 | 145 | 155 | 165 | 165 | 145 |

| HFX PHBV | 125 | 135 | 145 | 135 | 125 |

| Polymer | First Heating | Isotherm | Cooling | Isotherm | Second Heating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y1000 | 30–210 °C 10 °C/min | 210 °C 1 min | 210–30 °C10 °C/min | 30 °C 1 min | 30–210 °C 10 °C/min |

| HFX PHBV | 30–190 °C 10 °C/min | 190 °C 1 min | 190–30 °C 10 °C/min | 30 °C 1 min | 30–190 °C 10 °C/min |

| Trial | DCW (g/L) | PHBV (g/L) | Yield gPHBV/gDCW | Yield gDCW/gSubstrate | Yield gPHBV/gSubstrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML1 | 5.204 ± 0.354 | 0.134 ± 0.011 | 0.026 ± 0.003 | 1.239 ± 0.061 | 0.032 ± 0.01 |

| ML2 | 15.967 ± 4.367 | 2.127 ± 0.025 | 0.098 ± 0.050 | 1.625 ± 0.080 | 0.216 ± 0.010 |

| ML3 | 7.316 ± 1.302 | 0.926 ± 0.037 | 0.128 ± 0.004 | 0.585 ± 0.028 | 0.074 ± 0.003 |

| ML4 | 19.724 ± 4.439 | 1.883 ± 0.107 | 0.097 ± 0.006 | 1.262 ± 0.062 | 0.120 ± 0.005 |

| ML5 | 21.346 ± 1.615 | 1.152 ± 0.031 | 0.054 ± 0.013 | 1.195 ± 0.059 | 0.064 ± 0.002 |

| Condition | DCW (g/L) | PHBV (g/L) | Yield gPHBV/gDCW | Yield gDCW/gSubstrate | Yield gPHBV/gSubstrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML2 | 15.967 ± 4.367 | 2.127 ± 0.025 | 0.098 ± 0.050 | 1.625 ± 0.080 | 0.216 ± 0.010 |

| ML3 | 7.316 ± 1.302 | 0.926 ± 0.037 | 0.128 ± 0.004 | 0.585 ± 0.028 | 0.074 ± 0.003 |

| ML4 | 19.724 ± 4.439 | 1.883 ± 0.107 | 0.097 ± 0.006 | 1.262 ± 0.062 | 0.120 ± 0.005 |

| ML6 | 8.855 ± 1.235 | 0.985 ± 0.273 | 0.122 ± 0.036 | 0.901 ± 0.044 | 0.100 ± 0.004 |

| ML7 | 11.620 ± 0.117 | 1.782 ± 0.039 | 0.154 ± 0.039 | 0.929 ± 0.045 | 0.142 ± 0.006 |

| ML8 | 22.603 ± 1.615 | 2.044 ± 0.003 | 0.122 ± 0.017 | 1.449 ± 0.071 | 0.131 ± 0.006 |

| ML9 | 16.903 ± 0.163 | 1.404 ± 0.064 | 0.056 ± 0.006 | 1.720 ± 0.085 | 0.143 ± 0.006 |

| ML10 | 17.938 ± 1.302 | 0.926 ± 0.037 | 0.128 ± 0.004 | 1.434 ± 0.071 | 0.074 ± 0.003 |

| ML11 | 4.746 ± 0.208 | 1.939 ± 0.006 | 0.274 ± 0.001 | 0.304 ± 0.014 | 0.124 ± 0.005 |

| Condition | DCW (g/L) | PHBV (g/L) | Yield gPHBV/gDCW | Yield gDCW/gSubstrate | Yield gPHBV/gSubstrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML2 | 15.967 ± 4.367 | 2.127 ± 0.025 | 0.098 ± 0.050 | 1.625 ± 0.080 | 0.216 ± 0.010 |

| EL2 | 7.072 ± 0.940 | 2.564 ± 0.411 | 0.361 ± 0.011 | 0.720 ± 0.035 | 0.261 ± 0.012 |

| ML2.1 | 8.313 ± 0.672 | 1.962 ± 0.071 | 0.237 ± 0.028 | 0.846 ± 0.041 | 0.200 ± 0.009 |

| ML3 | 7.316 ± 1.302 | 0.926 ± 0.037 | 0.128 ± 0.004 | 0.585 ± 0.028 | 0.074 ± 0.003 |

| EL3 | 9.080 ± 0.272 | 3.250 ± 0.014 | 0.358 ± 0.011 | 0.726 ± 0.035 | 0.260 ± 0.012 |

| ML3.1 | 5.131 ± 0.223 | 0.043 ± 0.006 | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 0.410 ± 0.020 | 0.003 ± 0.001 |

| Condition | DCW (g/L) | PHBV (g/L) | Y gPHBV/gDCW | Y gDCW/ gSubstrate | Y gPHBV/gSubstrate | PHBV Productivity (mg/Lh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 7.542 ± 0.857 | 0.605 ± 0.033 | 0.080 ± 0.005 | 0.603 ± 0.029 | 0.048 ± 0.001 | 0.025 ± 0.001 |

| 48 h | 10.388 ± 1.358 | 2.113 ± 0.030 | 0.205 ± 0.030 | 0.831 ± 0.041 | 0.169 ± 0.007 | 0.030 ± 0.001 |

| 72 h | 6.254 ± 0.218 | 1.854 ± 0.011 | 0.297 ± 0.009 | 0.500 ± 0.024 | 0.148 ± 0.006 | 0.026 ± 0.001 |

| First Heating | Cooling | Second Heating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Blend | AHf (J/g) | Tm1/Tm2 (°C) | ∆Hc (J/g) | Tc (°C) | ∆Hf (J/g) | Tm1/Tm2 (°C) |

| Y1000 | 60.1 | 174.8 | −65.6 | 106.7 | 67.6 | 172.1 |

| Y1000 + 1%T | 59.9 | 175.9 | −70.4 | 109.9 | 76.8 | 171.4 |

| Y1000 + 1%OA | 60 | 175.4 | −68.5 | 116.9 | 70 | 173.1 |

| 182.8 | ||||||

| Y1000 + 1%BN | 55.4 | 177.1 | −72.5 | 121.8 | 77.7 | 171.9 |

| 185.4 | ||||||

| HFX PHBV | 16.9 | 135.2 | 24.6 | 133.1 | ||

| 156.9 | 144 | |||||

| HFX PHBV + 1%T | 20.8 | 134.8 | −11 | 53.9 | 34.3 | 128.6 |

| 156.6 | 143.6 | |||||

| HFX PHBV + 1%OA | 20.3 | 135 | −26.5 | 75.6 | 31 | 133.9 |

| 157.1 | 145.1 | |||||

| HFX PHBV + 1%BN | 22.8 | 135.3 | −25.4 | 70.2 | 33.2 | 132 |

| 155.9 | 144.6 | |||||

| Polymer Blend | Total Area | Crystalline Area | Crystallinity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Y1000 | 936.06 | 658.98 | 70.4 |

| Y1000 + 1% T | 979.78 | 695.21 | 71.0 |

| Y1000 + 1% OA | 965.41 | 715.70 | 74.1 |

| Y1000 + 1% BN | 960.31 | 701.19 | 73.0 |

| HFX PHBV | 786.57 | 453.80 | 57.7 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% T | 650.77 | 362.16 | 55.7 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% OA | 355.53 | 219.85 | 61.8 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% BN | 715.1 | 375.75 | 52.5 |

| Material | a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PHB [58] | 5.76 | 13.2 | 5.96 | 453.15 |

| Y1000 | 5.696 | 13.094 | 5.911 | 440.86 |

| OA [59] | 5.898 | 6.928 | 9.592 | 391.94 |

| Y1000 + 1% T | 5.680 | 13.038 | 5.957 | 441.15 |

| Y1000 + 1% OA | 5.696 | 13.086 | 5.911 | 440.59 |

| Y1000 + 1% BN | 5.712 | 13.131 | 5.921 | 444.20 |

| HFX PHBV | 5.748 | 13.183 | 5.938 | 449.96 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% T | 5.689 | 12.944 | 5.863 | 431.74 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% OA | 5.653 | 12.897 | 5.848 | 426.36 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% BN | 5.716 | 13.086 | 6.002 | 448.95 |

| Young’s Modulus (MPa) | Time (days) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | |

| HFX PHBV | 383 ± 29 | 560 ± 26 | 610 ± 44 | 637 ± 38 | 687 ± 21 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% T | 480 ± 36 | 617 ± 70 | 710 ± 10 | 733 ± 32 | 820 ± 56 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% OA | 497 ± 23 | 650 ± 42 | 653 ± 114 | 717 ± 81 | 853 ± 51 |

| HFX PHBV + 1% BN | 517 ± 15 | 593 ± 42 | 697 ± 47 | 737 ± 72 | 817 ± 70 |

| Tc (°C) | ΔHc (J/g) | Polymer | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| n.d. | n.d. | HFX PHBV | This study |

| 60.63 ± 10.47 | 12.57 ± 3.71 | HFX PHBV + 1% T | This study |

| 75.50 ± 0.10 | 26.53 ± 0.06 | HFX PHBV + 1% OA | This study |

| 69.70 ± 0.78 | 24.97 ± 1.02 | HFX PHBV + 1% BN | This study |

| 55.4 | 41.4 | P(98.66% HB-co-1.34% HV) | [73] |

| 61.0 | 48.7 | P(99.54% HB-co-0.46% HV) | [74] |

| 61.4 | 53.5 | P(99.85% HB-co-0.15% HV) | [74] |

| 58.6 | 36.1 | P(99.22% HB-co-0.78% HV) | [74] |

| 53.2 | 38.8 | P(39.41% HB-co-60.59% HV) | [74] |

| 58.0 | 49.0 | P(99.50% HB-co-0.5% HV) | [74] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

García-Chumillas, S.; Nicolás-Liza, M.; Monzó, F.; Martínez-Rubio, P.-M.; Arribas, A.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M.; Pamies, R. Exploring Lemon Industry By-Products for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production: Comparative Performances of Haloferax mediterranei PHBV vs. Commercial PHBV. Polymers 2026, 18, 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030340

García-Chumillas S, Nicolás-Liza M, Monzó F, Martínez-Rubio P-M, Arribas A, Martínez-Espinosa RM, Pamies R. Exploring Lemon Industry By-Products for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production: Comparative Performances of Haloferax mediterranei PHBV vs. Commercial PHBV. Polymers. 2026; 18(3):340. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030340

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Chumillas, Salvador, María Nicolás-Liza, Fuensanta Monzó, Pablo-Manuel Martínez-Rubio, Alejandro Arribas, Rosa María Martínez-Espinosa, and Ramón Pamies. 2026. "Exploring Lemon Industry By-Products for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production: Comparative Performances of Haloferax mediterranei PHBV vs. Commercial PHBV" Polymers 18, no. 3: 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030340

APA StyleGarcía-Chumillas, S., Nicolás-Liza, M., Monzó, F., Martínez-Rubio, P.-M., Arribas, A., Martínez-Espinosa, R. M., & Pamies, R. (2026). Exploring Lemon Industry By-Products for Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production: Comparative Performances of Haloferax mediterranei PHBV vs. Commercial PHBV. Polymers, 18(3), 340. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18030340