Enhanced Numerical Modeling of Non-Newtonian Particle-Laden Flows: Insights from the Carreau–Yasuda Model in Circular Tubes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Model and Methods

2.1. Governing Equations

2.2. Particle Poiseuille Flow Through a Cylindrical Tube

2.3. Steady State Velocity and Particle Distributions

2.4. Nondimensionalization and Numerical Details

3. Results and Discussion

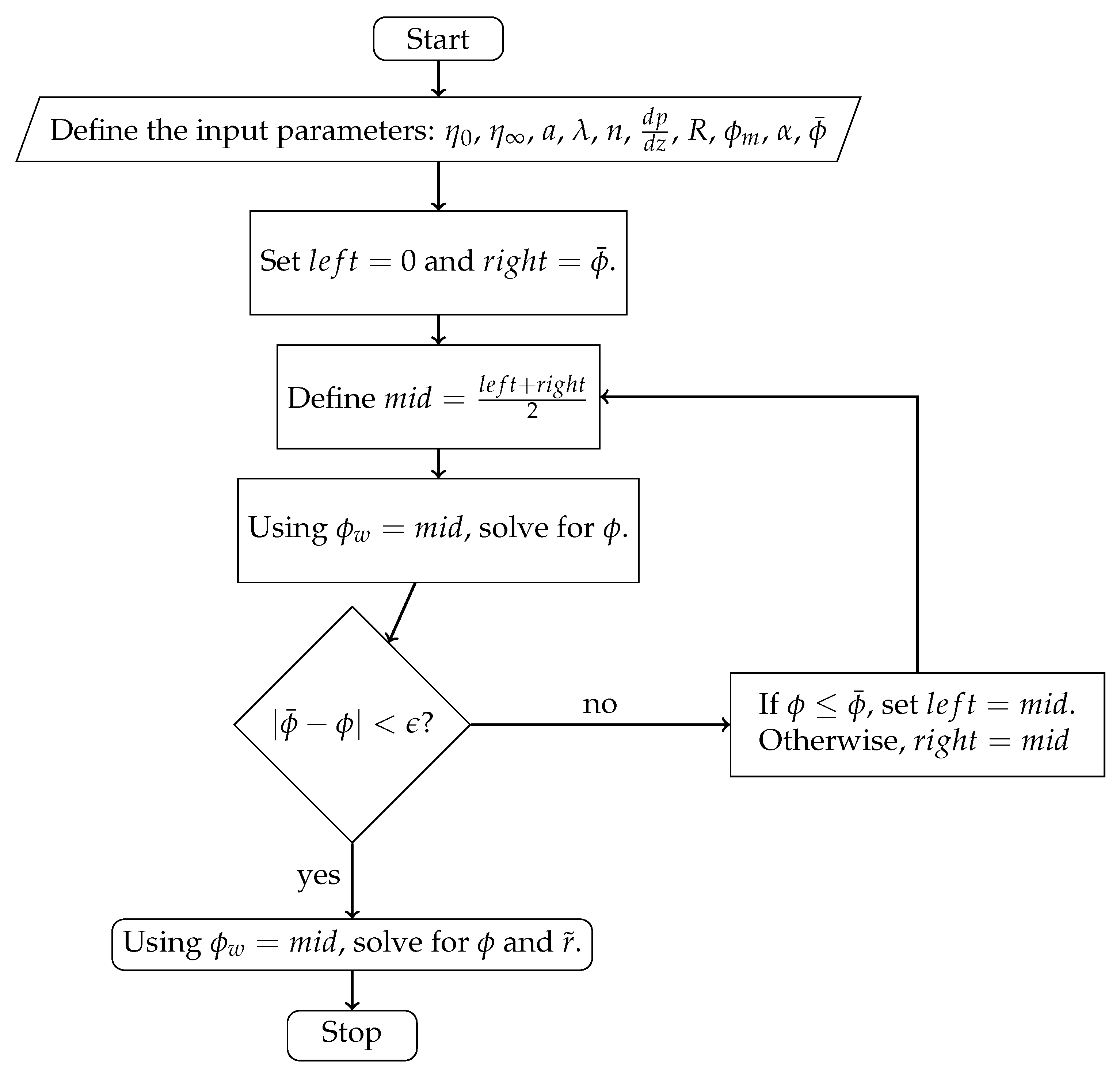

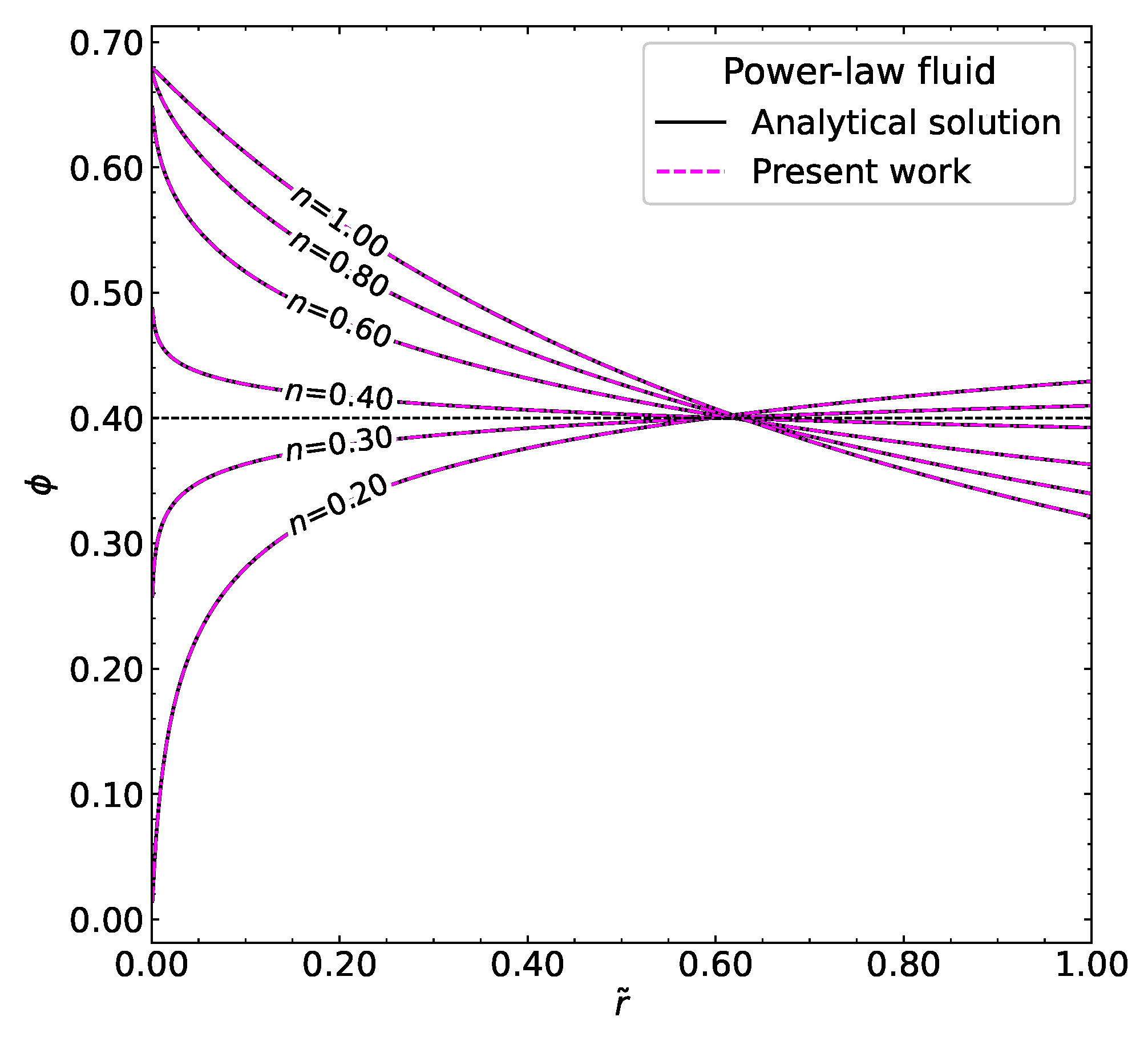

3.1. Verification and Validation of Numerical Results

3.1.1. Newtonian Fluid

3.1.2. Power-Law Fluid

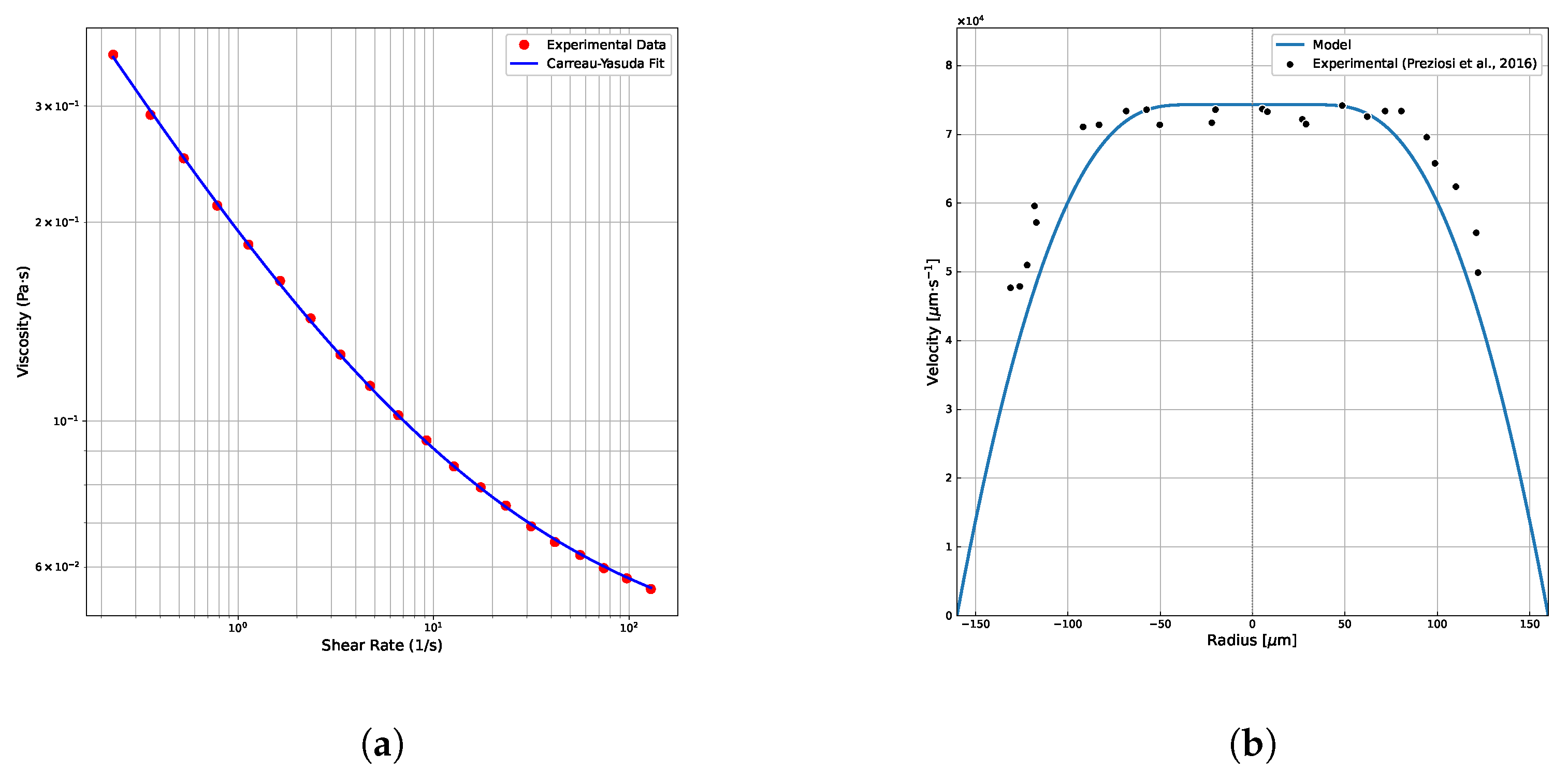

3.1.3. Comparison with Experimental Data

- Pa·s (zero-shear viscosity);

- Pa·s (infinite-shear viscosity);

- (Carreau–Yasuda transition parameter);

- s (relaxation time);

- (power-law index);

- Pa/m (pressure gradient);

- m (tube radius);

- (maximum particle volume fraction used by Preziosi et al.);

- (migration parameter );

- (average particle volume fraction).

3.1.4. Other Relative Viscosity Models

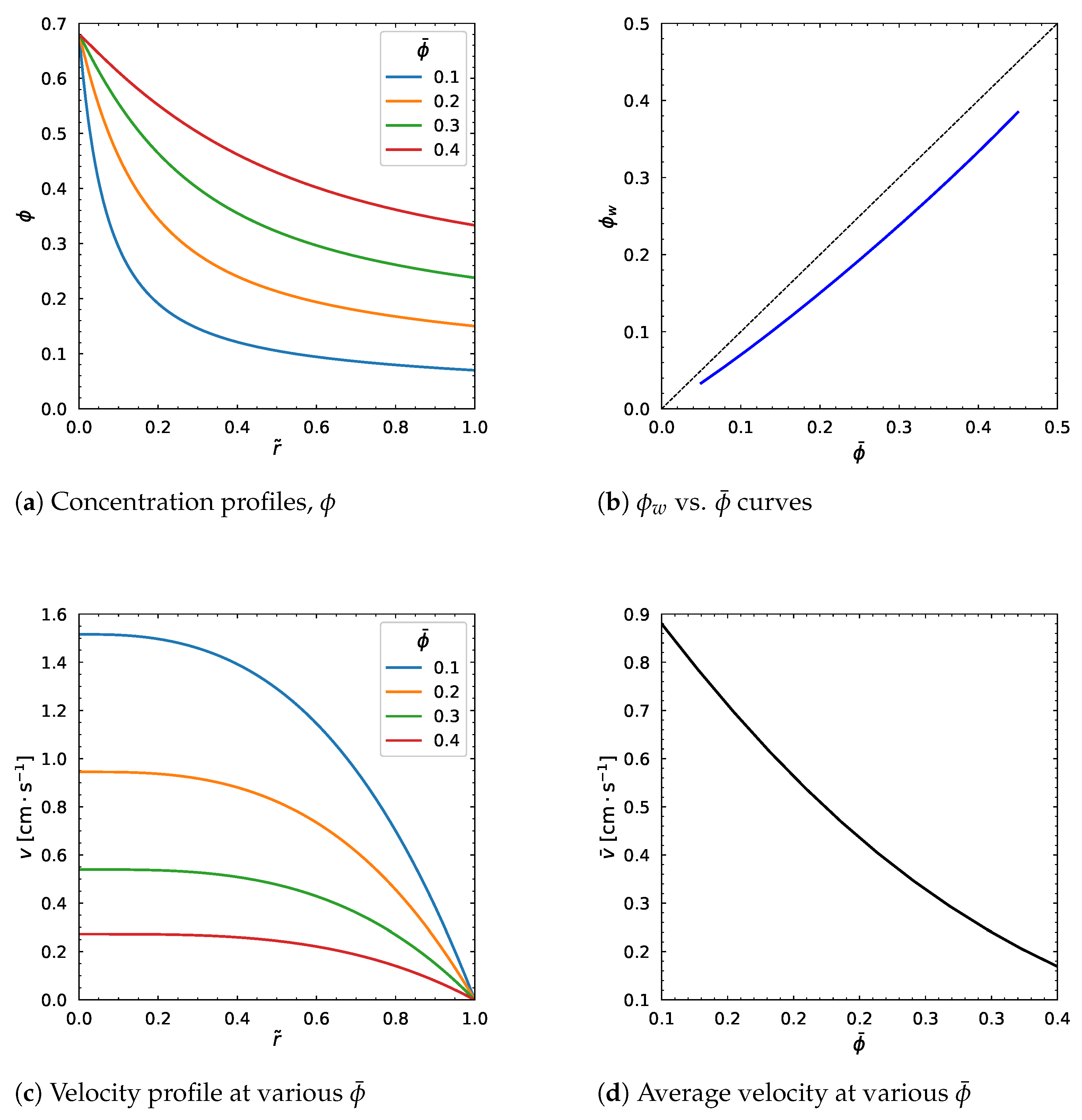

3.2. Influence of Average Particle Volume Fraction

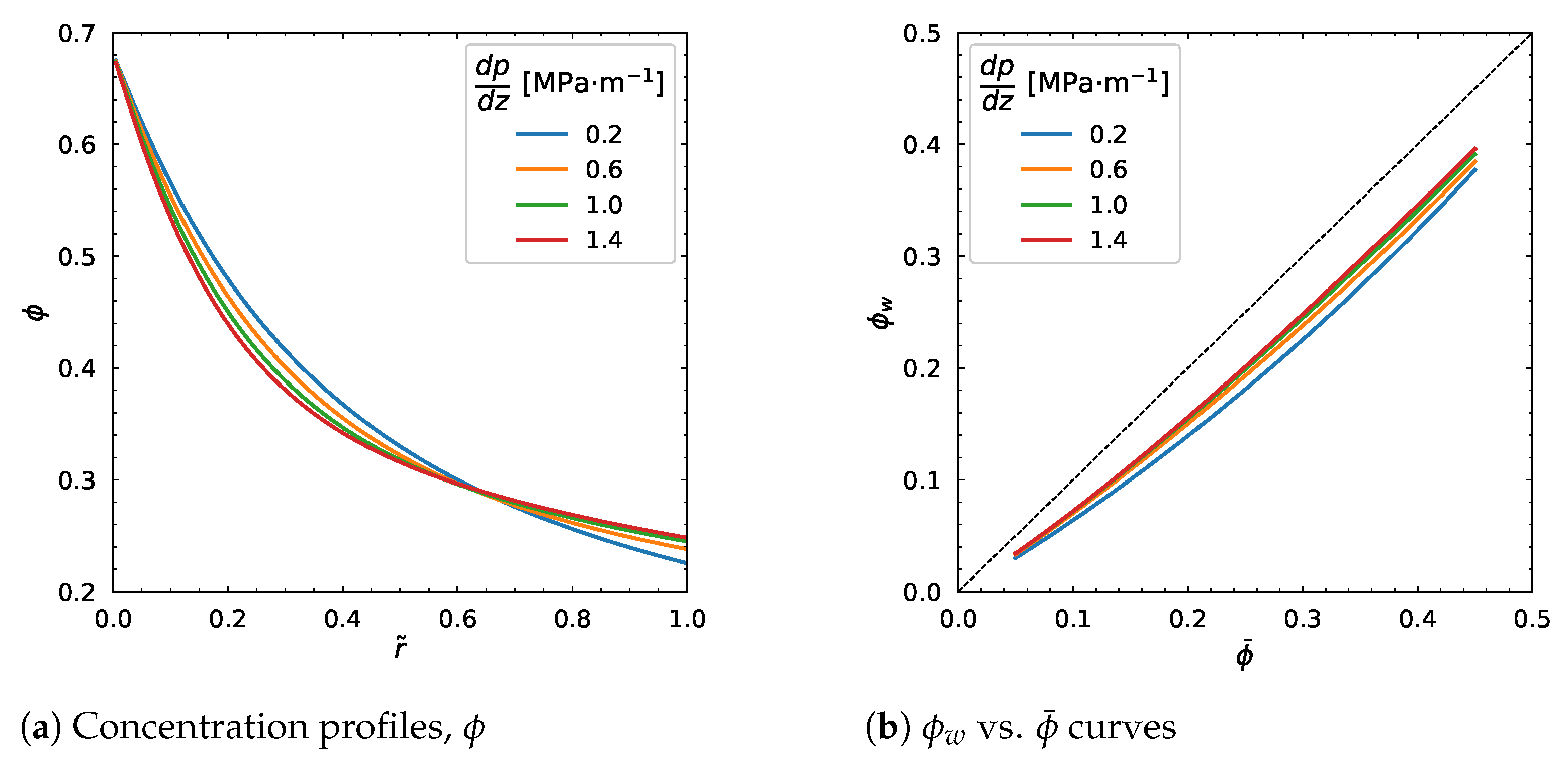

3.3. Influence of Pressure Gradient

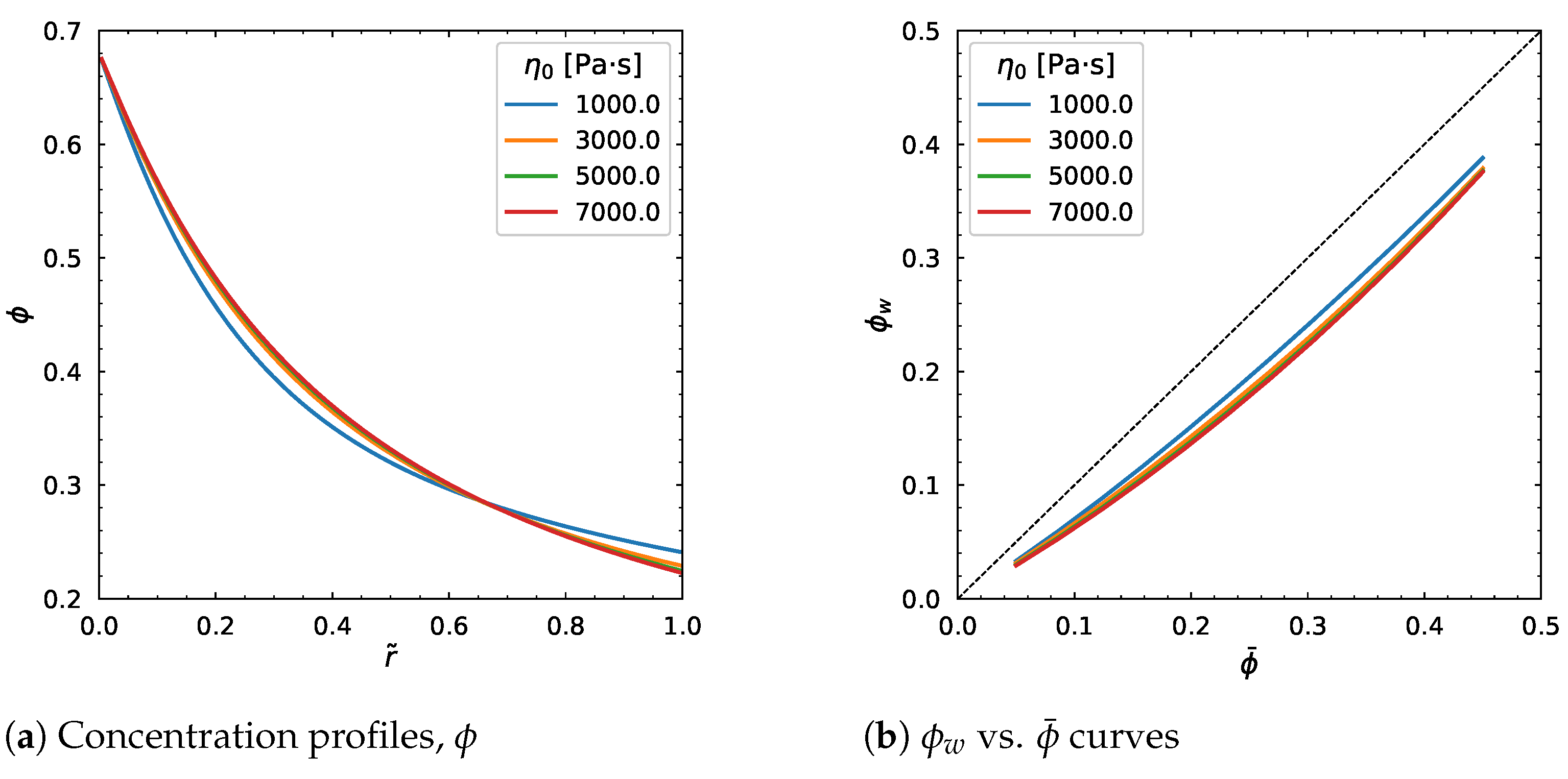

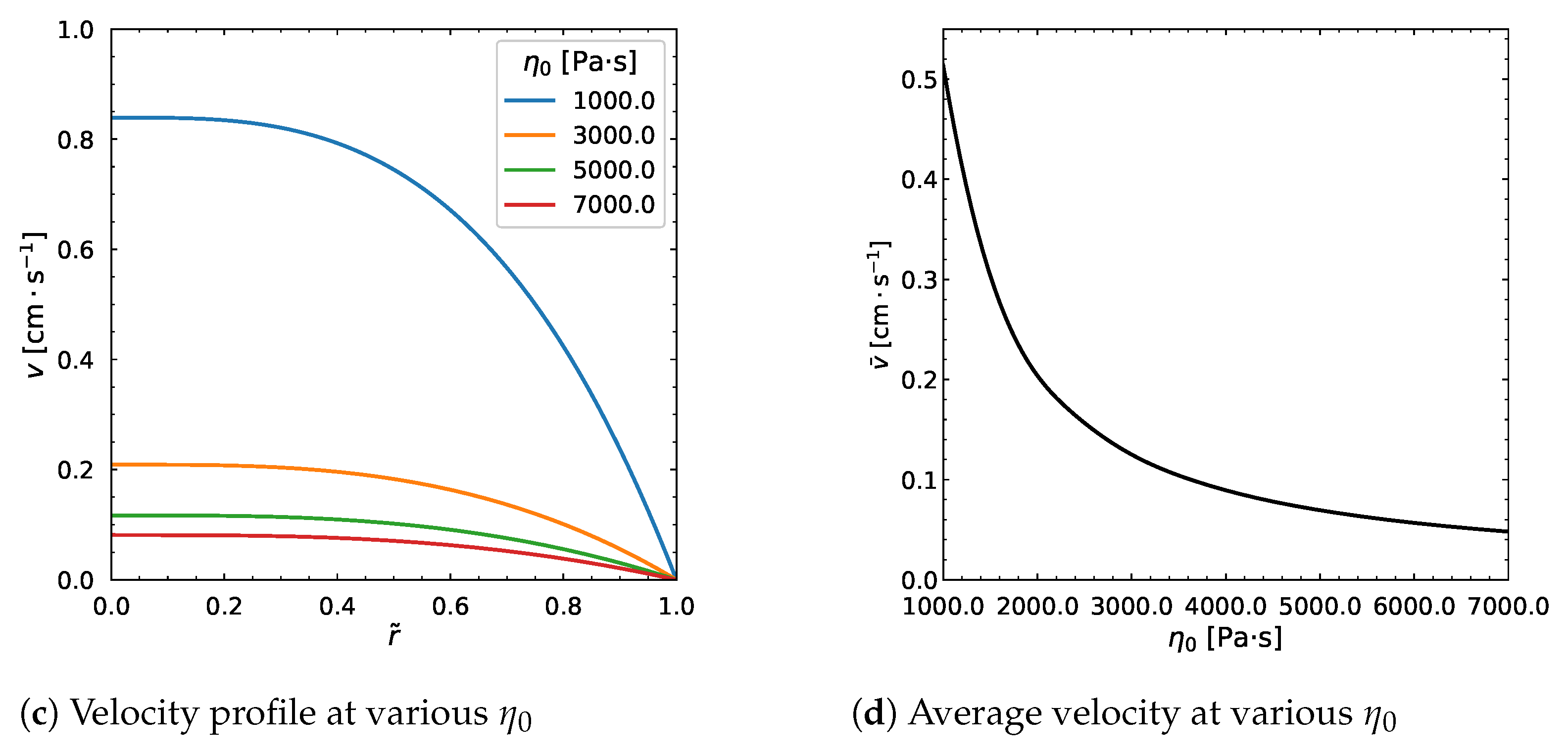

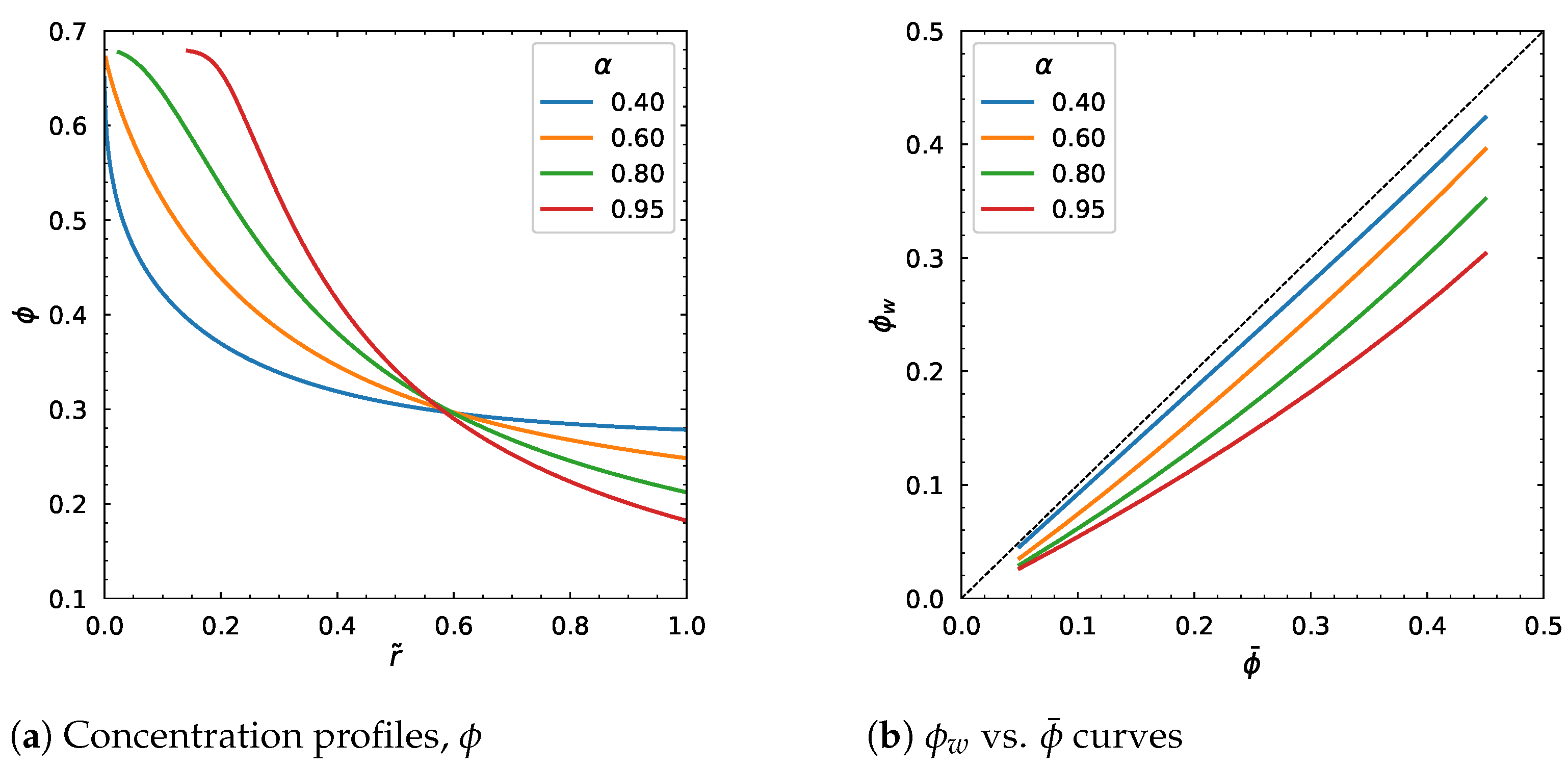

3.4. Influence of Carreau–Yasuda Parameters

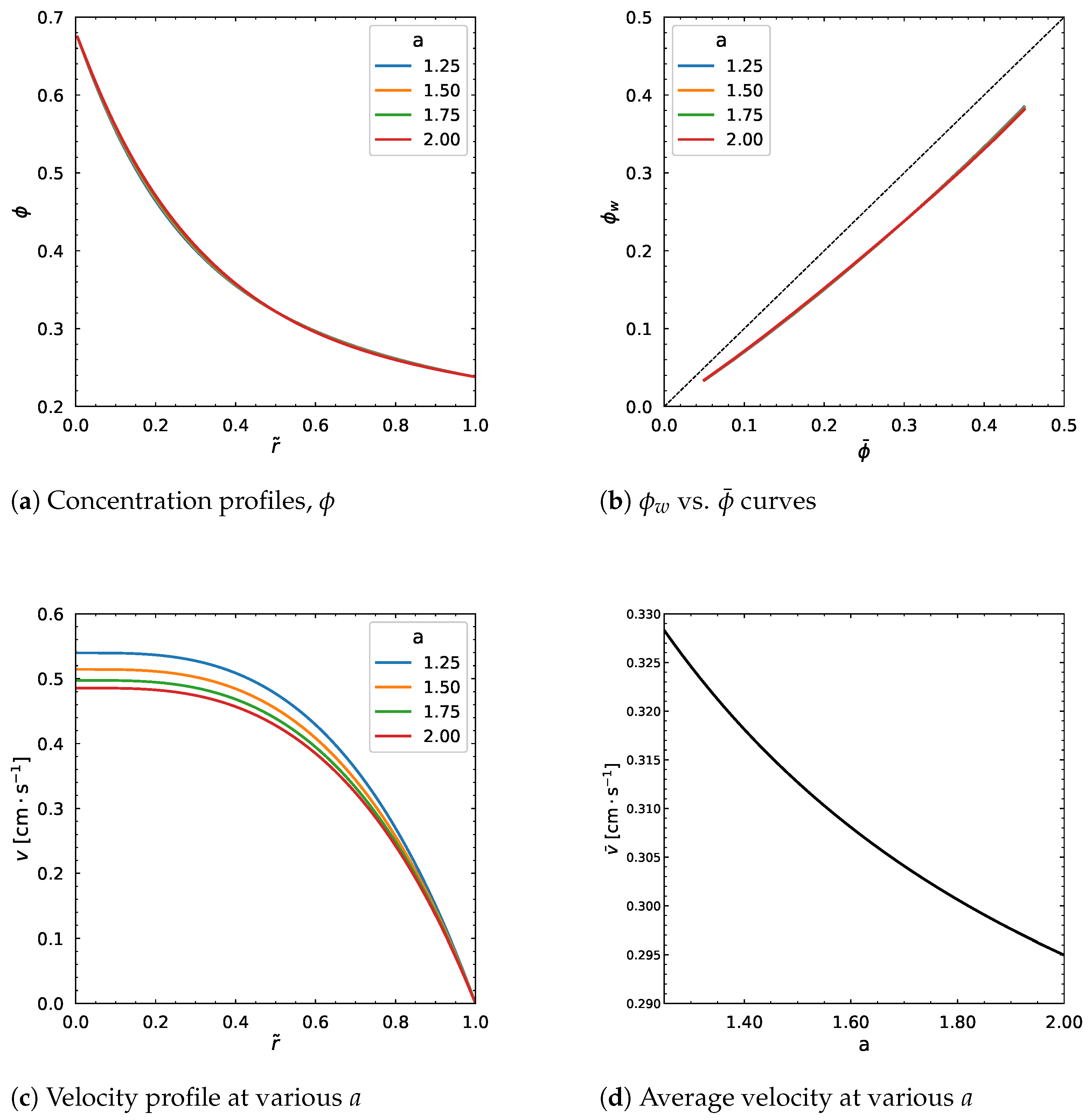

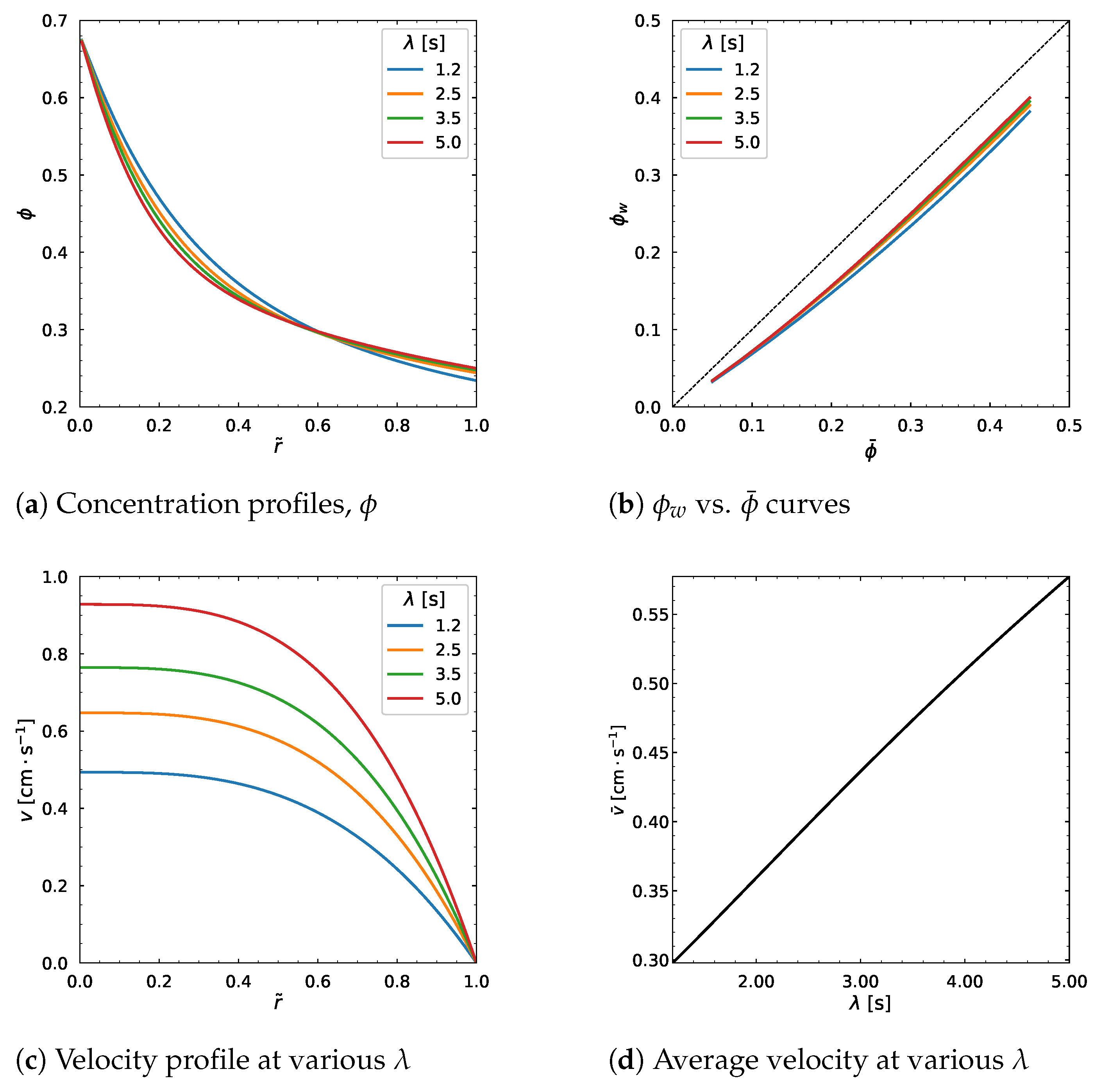

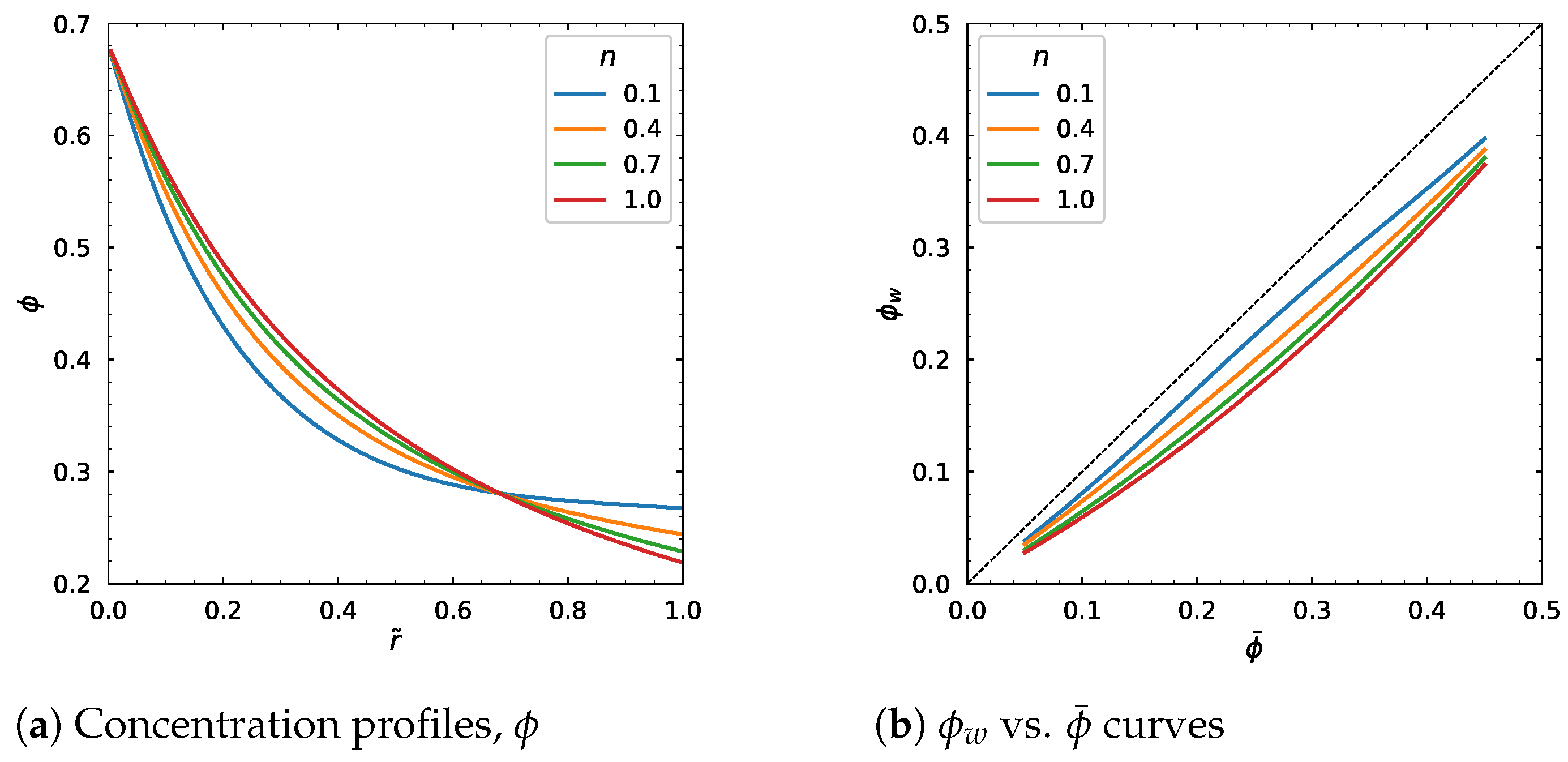

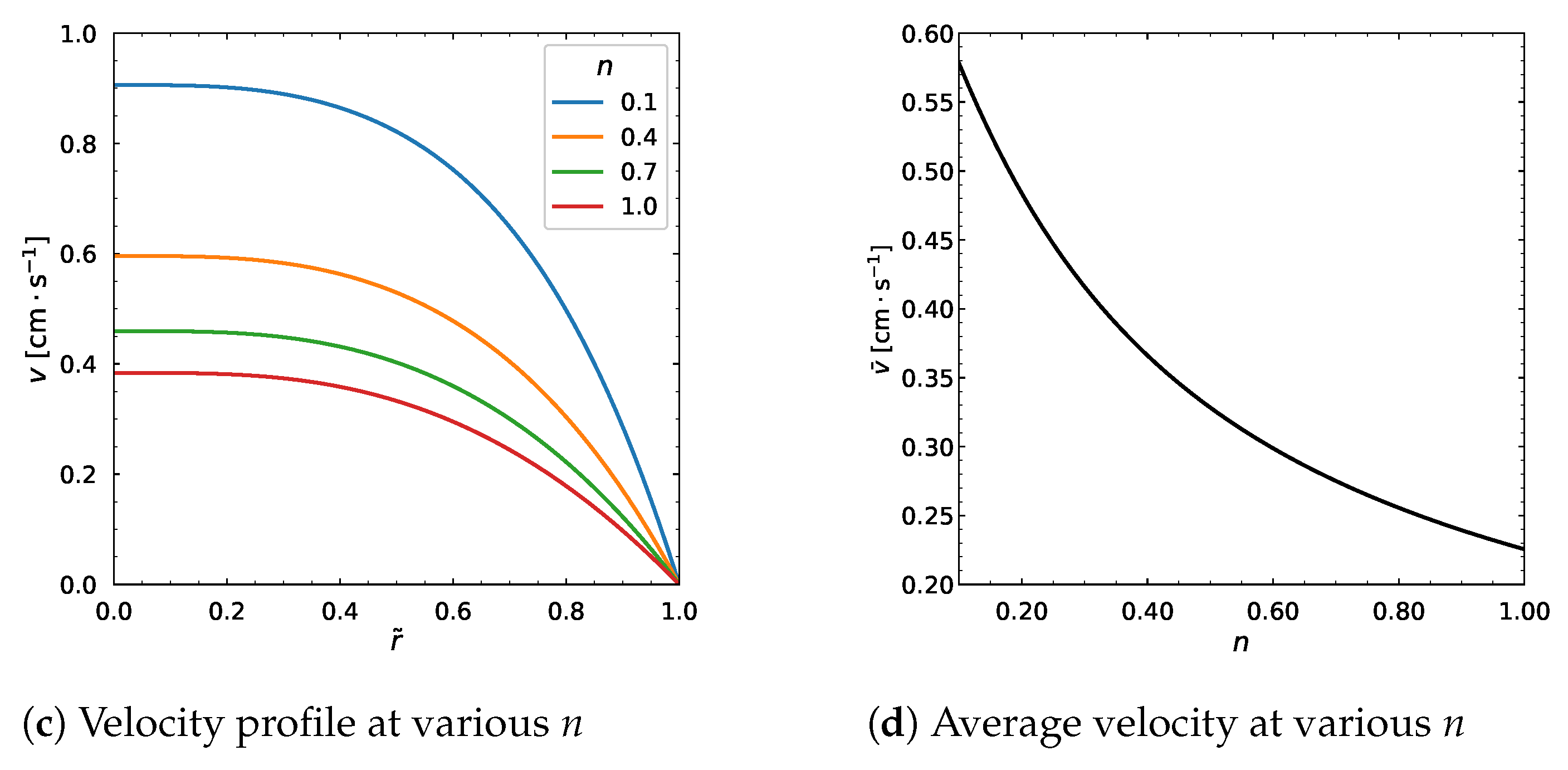

3.5. Influence of Other Model Parameters

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Particle volume fraction | |

| Maximum packing fraction | |

| Average particle volume fraction | |

| Particle volume fraction at the wall | |

| r | Point along radius of the tube (m) |

| Point along nondimensional radius of the tube | |

| R | Maximum radius of the tube (m) |

| z | Axial coordinate (m) |

| Shear rate () | |

| Shear rate at the wall () | |

| s | Nondimensional shear rate |

| Nondimensional velocity | |

| v | Dimensional velocity () |

| Dimensional average velocity () | |

| Pressure gradient () | |

| Viscosity (Pa·s) | |

| Viscosity at the wall (Pa·s) | |

| Nondimensional viscosity | |

| Zero-shear viscosity (Pa·s) | |

| Infinite-shear viscosity (Pa·s) | |

| Time constant (s) | |

| n | Power-law index (–) |

| a | Yasuda parameter (–) |

| Particle migration coefficient due to collisions | |

| Particle migration coefficient due to viscosity gradients | |

| Gradient of particle concentration (1/m) | |

| Shear stress (Pa) | |

| Extra stress tensor (Pa) | |

| b | particle radius (m) |

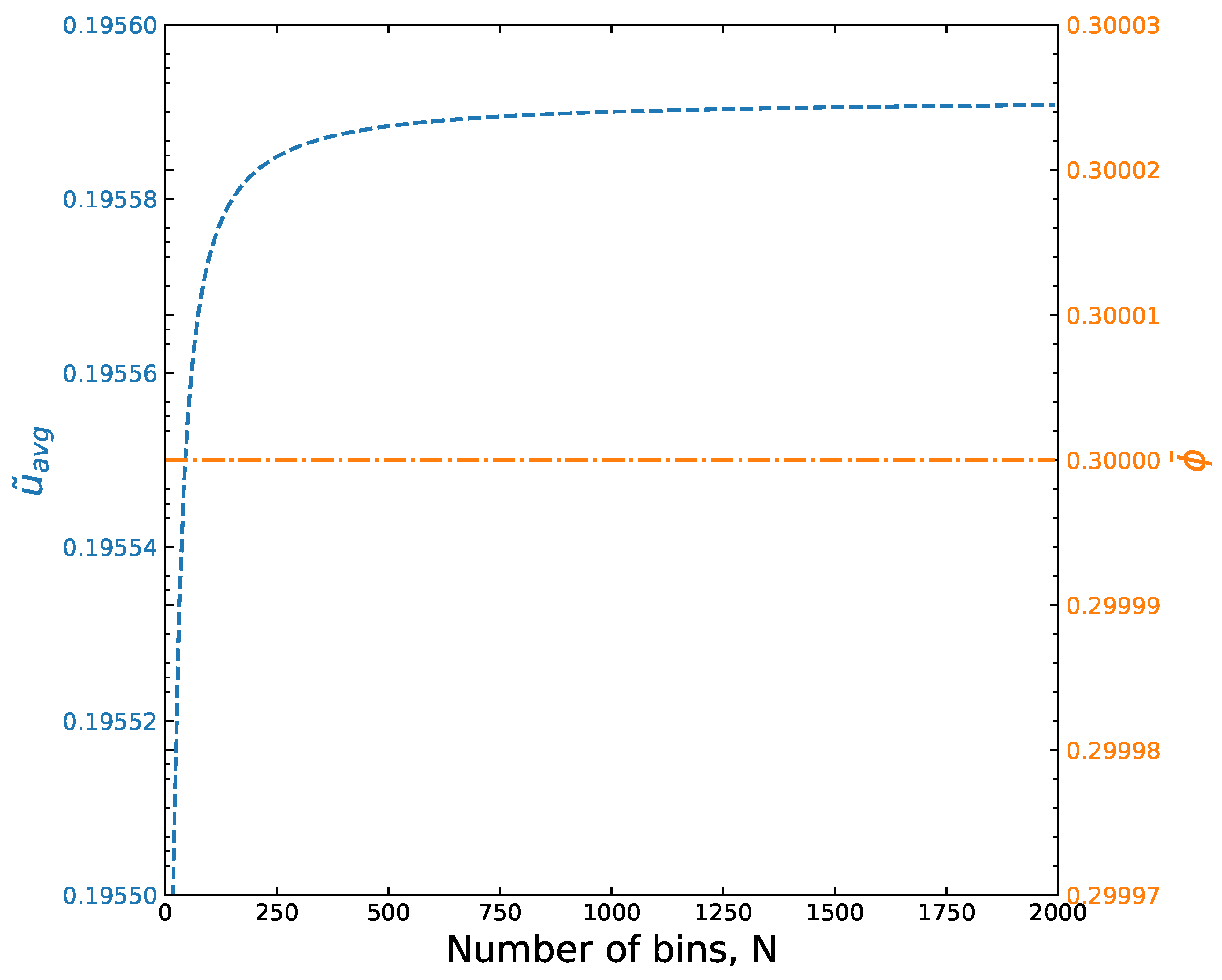

Appendix A. Function Error and Optimal Mesh Size in Numerical Computations

Appendix B. Influence of Carreau–Yasuda Model Parameters on Viscosity

Appendix C. Derivation of the Reduced Steady-State System

References

- Xie, X.; Zhang, L.; Shi, C.; Liu, X. Prediction of lubrication layer properties of pumped concrete based on flow induced particle migration. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 322, 126115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M.; Auscher, M.; Fulchiron, R.; Périé, T.; Martin, G.; Sonntag, P.; Cassagnau, P. Rheology and applications of highly filled polymers: A review of current understanding. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 66, 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.; Heckner, T.; Chrupala, A.; Pollock, J.; Goris, S.; Osswald, T. Experimental study of particle migration in polymer processing. Polym. Compos. 2019, 40, 2165–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.D.; Hare, S.D.; Slater, P.R.; Simmons, M.J.H.; Kendrick, E. Rheology and Structure of Lithium-Ion Battery Electrode Slurries. Energy Technol. 2022, 10, 2200545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.; Lam, J.; Yang, L.; Kendrick, E. Extensional rheology of battery electrode slurries with water-based binders. Mater. Des. 2022, 222, 111104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.; Armstrong, R.; Brown, R.; Graham, A.; Abbott, J. A Constitutive Equation for Concentrated Suspensions that Accounts for Shear- Induced Particle Migration. Phys. Fluids A Fluid Dyn. 1992, 4, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.; Armstrong, R.; Hassager, O. Dynamics of Polymeric Liquids. Volume 1, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.; Mirbod, P. Shear-induced particle migration of semi-dilute and concentrated Brownian suspensions in both Poiseuille and circular Couette flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2020, 126, 103239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dbouk, T.; Lemaire, E.; Lobry, L.; Moukalled, F. Shear-induced particle migration: Predictions from experimental evaluation of the particle stress tensor. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2013, 198, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauzlarić, D.; Greiner, A.; Korvink, J.G. A non-local extension of the Phillips model for shear induced particle migration. Microsyst. Technol. 2011, 17, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tan, K.; Lam, Y.; Chai, J. The Transverse Particle Migration of Highly Filled Polymer Fluid Flow in a Pipe. Innovation in Manufacturing Systems and Technology (IMST). 2003. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/3757 (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Chen, X.; Lam, Y.; Tan, K.; Chai, J.; Yu, S. Shear-Induced Particle Migration modelling in a concentrated suspension flow. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2003, 11, 503–522. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0965-0393/11/4/307 (accessed on 10 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Cebeci, T. Convective Heat Transfer, 2nd ed.; Springer GmbH & Co. KG: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. Steady isothermal flow of a Carreau–Yasuda model fluid in a straight circular tube. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2022, 310, 104937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, M.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, S. Prediction on pipe flow of pumped concrete based on shear-induced particle migration. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 52, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, I.; Carvalho, M. Particle migration in planar die-swell flows. J. Fluid Mech. 2017, 825, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouças, R.B.; Siqueira, I.; de Souza Mendes, P.; Carvalho, M. On the pressure-driven flow of suspensions: Particle migration in shear sensitive liquids. J. Non-Newton. Fluid Mech. 2016, 234, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, M. Rheology and Processing of Highly Filled Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Universite de Lyon, Lyon, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Preziosi, V.; Tomaiuolo, G.; Fenizia, M.; Caserta, S.; Guido, S. Confined tube flow of low viscosity emulsions: Effect of matrix elasticity. J. Rheol. 2016, 60, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krieger, I.; Dougherty, T. A Mechanism for Non-Newtonian Flow in Suspensions of Rigid Spheres. Trans. Soc. Rheol. 1959, 3, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, J.S.; Christiansen, E.B.; Baer, A.D. Rheology of concentrated Suspensions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1971, 15, 2007–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quemada, D. Rheology of concentrated disperse systems and minimum energy dissipation principle. Rheol. Acta 1977, 16, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | (Pa·s) | (Pa·s) | a | (s) | n | (MPa/m) | R (m) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1400 | 100 | 1.25 | 1.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.01 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Amangeldi, M.; Wei, D.; Perveen, A.; Zhang, D. Enhanced Numerical Modeling of Non-Newtonian Particle-Laden Flows: Insights from the Carreau–Yasuda Model in Circular Tubes. Polymers 2026, 18, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010043

Amangeldi M, Wei D, Perveen A, Zhang D. Enhanced Numerical Modeling of Non-Newtonian Particle-Laden Flows: Insights from the Carreau–Yasuda Model in Circular Tubes. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleAmangeldi, Medeu, Dongming Wei, Asma Perveen, and Dichuan Zhang. 2026. "Enhanced Numerical Modeling of Non-Newtonian Particle-Laden Flows: Insights from the Carreau–Yasuda Model in Circular Tubes" Polymers 18, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010043

APA StyleAmangeldi, M., Wei, D., Perveen, A., & Zhang, D. (2026). Enhanced Numerical Modeling of Non-Newtonian Particle-Laden Flows: Insights from the Carreau–Yasuda Model in Circular Tubes. Polymers, 18(1), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010043