This section presents the performance of the proposed LSTM models across different feature sets and prediction horizons. We begin with the sequence-to-time-step results, which showed the strongest and most consistent behaviour.

Short-Horizon LSTM Prediction Results

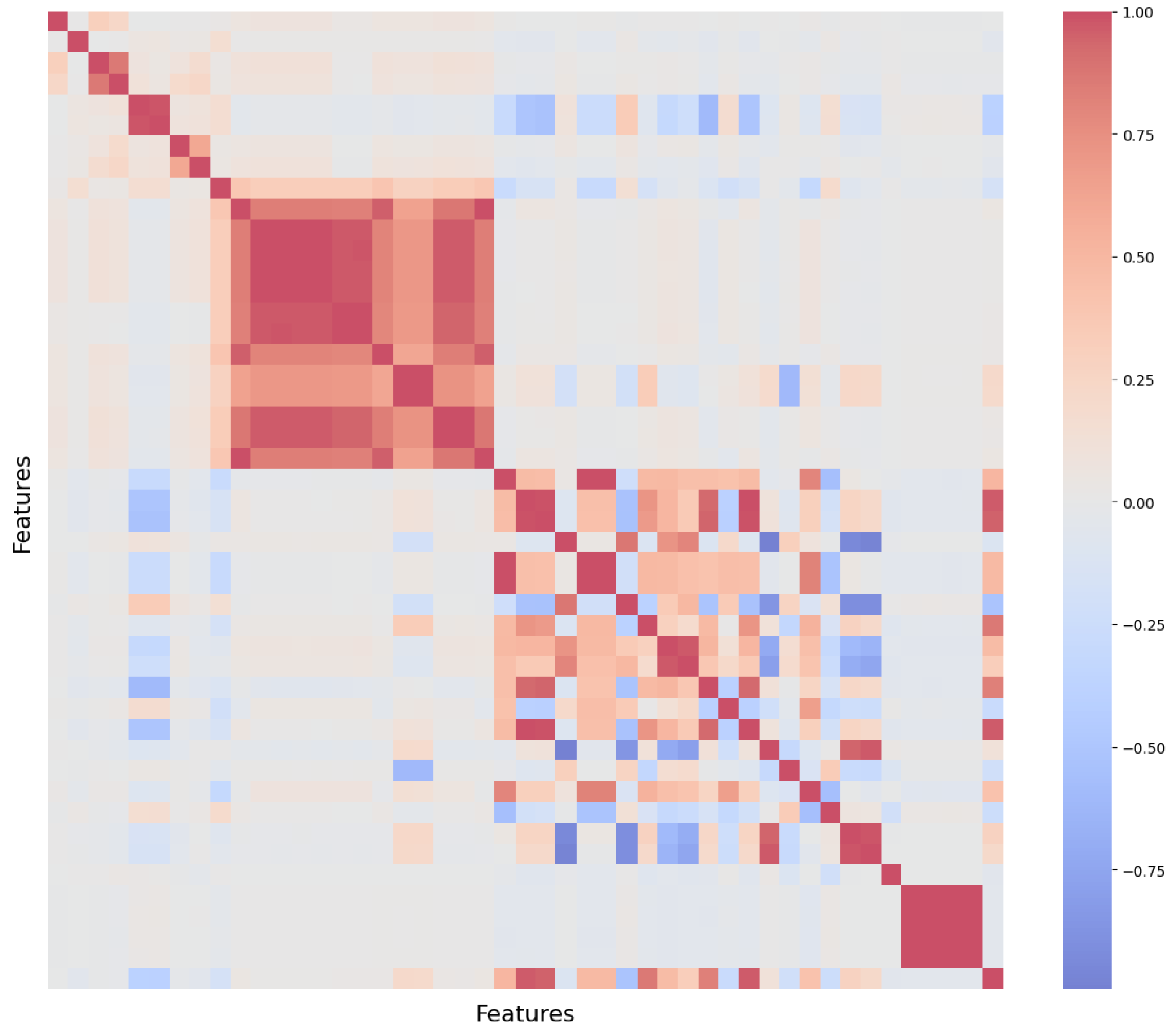

This section presents the evaluation of all LSTM configurations under six experimental setups, combining three feature-selection strategies with two prediction horizons. The feature groups tested were (i) Double Torque (2 features), (ii) Pearson Correlation (14 features), and (iii) Explained Variance (33 features). All models were trained using sliding windows of 50 cycles and evaluated for both next-step (sequence-to-time-step) prediction and multi-step (sequence-to-sequence) prediction over a defect-prone horizon of seven cycles. Given the strong class imbalance present in the dataset, the F1-score was adopted as the primary metric for assessing anomaly detection performance.

A. Next-Step Instability Detection.

The sequence-to-time-step formulation yielded the strongest and most consistent results across all experiments. Although this approach predicts only the next time step, it effectively identifies the subtle temporal deviations that precede volatile operating conditions. As shown in

Table 1, the two-feature torque-based model provided strong performance with a macro-average F1-score of 0.94, demonstrating that even minimal, but rheologically meaningful, feature sets are sufficient for accurate predictions.

Similarly, the 33-feature explained-variance set (see

Table 2) achieved a macro-average F1-score of 0.95, with anomaly-class F1 around 0.91 and normal-class F1 around 0.96.

The identical performance values reported in

Table 1 and

Table 2 show that, for next-step prediction, torque features already capture the dominant discriminative information, and adding explained-variance features does not provide additional predictive benefit beyond torque-based inputs.

The Pearson 14-feature dataset also performed competitively (see

Table 3), achieving a macro-average F1-score of 0.93, despite slightly lower anomaly-class recall.

These observations confirm that modelling short-horizon dynamics is an effective strategy for capturing drift conditions in injection moulding, where instability typically develops gradually rather than abruptly.

B. Polymer-Science Interpretation of Model Behaviour.

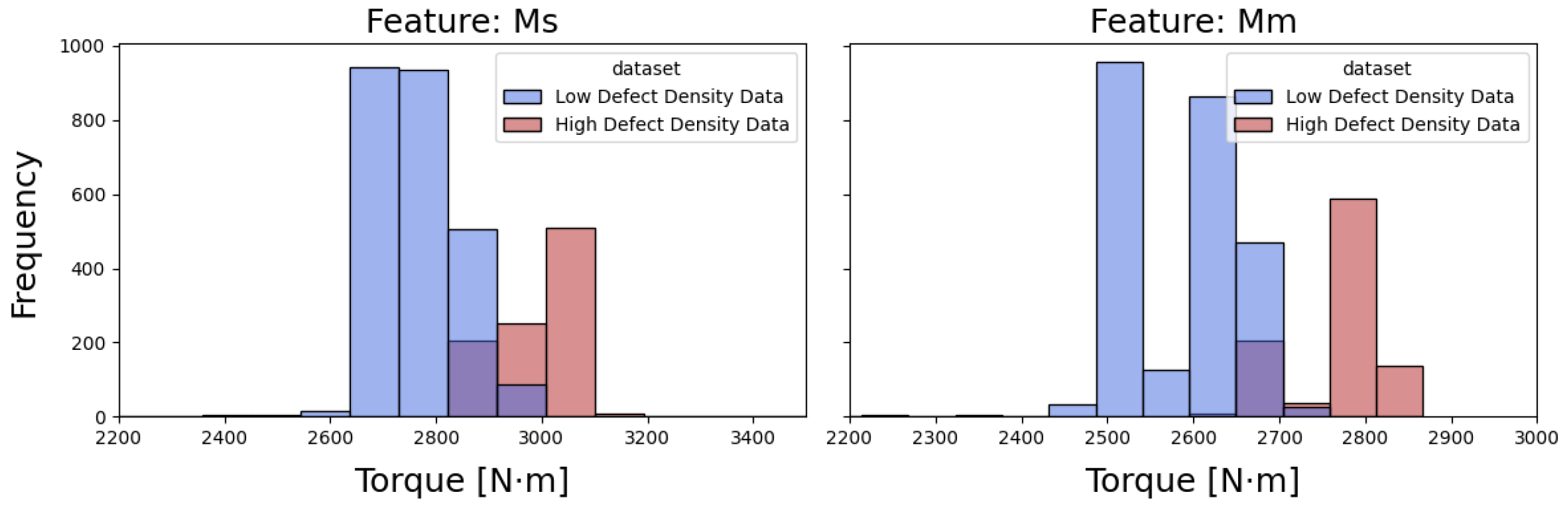

The predictive patterns learned by the LSTM model align closely with established thermo-rheological behaviour of polymer melts. Volatile periods in the dataset were preceded by slow drifts in melt viscosity and progressive increases in screw torque. Such behaviour is consistent with fluctuating shear conditions, insufficient or uneven plastification, and transient thermal imbalances within the barrel. These rheological deviations typically manifest before visible defects occur, such as incomplete filling or the formation of weld lines, explaining why the LSTM is able to anticipate instability windows several minutes before they become critical.

The model also showed high sensitivity to variations in injection pressure and filling time. Both parameters are directly tied to the resistance of the melt during cavity filling. Minor deviations in these signals often indicate changes in melt temperature, shear rate, or local viscosity. The model’s reliance on these variables demonstrates its ability to infer the physical state of the melt through patterns embedded in machine signals, even when explicit thermal measurements present limited variability.

Together, these findings show that the LSTM is not merely detecting statistical anomalies; it is identifying physically meaningful precursors to rheological instability.

C. Evidence of Non–Thermo-Rheological Influences.

While the LSTM models predominantly captured behaviour consistent with the thermo-rheological characteristics of polymer melts, several observations indicate that non-rheological factors also contributed to the predictions.

Mechanical torque effects: Although screw torque is strongly related to melt viscosity, it is also influenced by mechanical phenomena such as screw-drive friction, lubrication variability, servo-motor dynamics, or equipment wear. The strong performance of the two-feature torque configuration suggests that the LSTM may be responding to a mixture of mechanical and rheological signals.

Indirect detection of thermal variations: Due to the low variance in recorded melt and barrel temperatures, these features contributed minimally to the learning process. As a result, the model inferred thermal instabilities indirectly through pressure and torque patterns. Any thermal drift not reflected in these secondary features would not be detected directly.

Operational sources of variability: Occasional cycle-time irregularities, potentially caused by downstream robotics, conveyor delays, or operator intervention, also influenced anomaly predictions. These fluctuations are operational rather than rheological, indicating that the models capture process-level disturbances beyond melt behaviour.

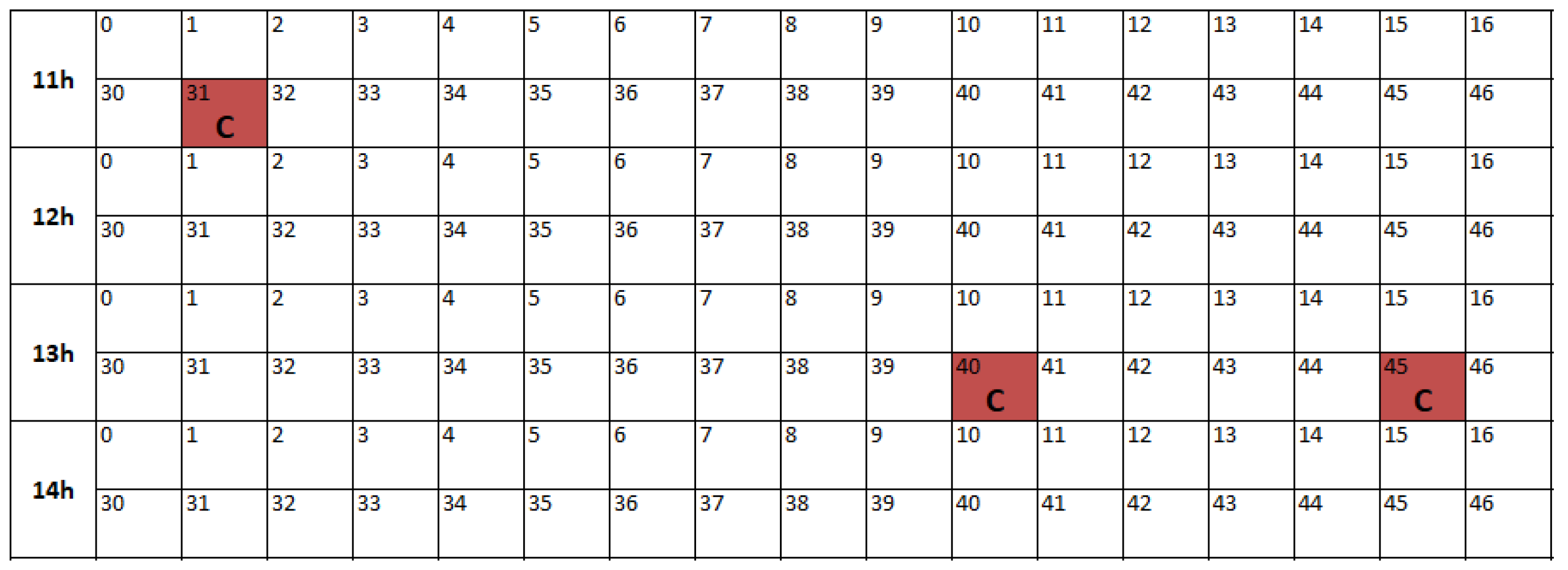

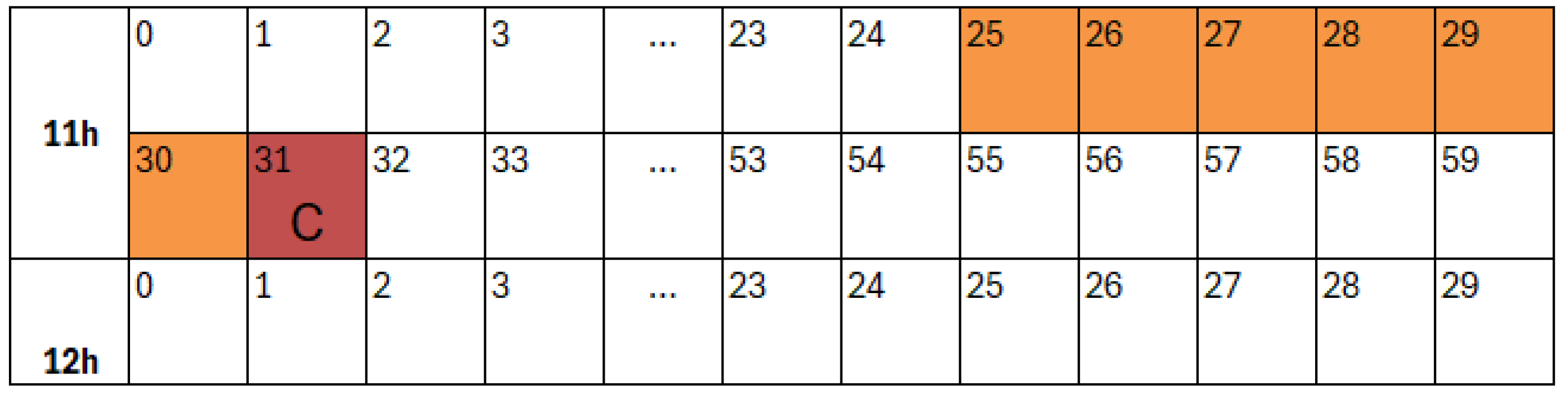

Label ambiguity: The use of a seven-cycle volatile window introduced ambiguous training examples, particularly for sequence-to-sequence prediction. When a sequence containing both stable and unstable behaviour is labelled entirely as volatile, the discriminative signal becomes diluted, complicating the model’s ability to distinguish true melt-instability patterns from benign variations.

These observations reflect the realistic complexity of industrial data, in which mechanical, operational, and rheological effects interact simultaneously. While the model effectively anticipates melt-instability events, its predictions incorporate a combination of polymer-process signatures and machine-related behaviours, which is typical in real manufacturing environments.

D. Sequence-to-Sequence Prediction.

The sequence-to-sequence approach delivered lower accuracy than the single-step models. As reported in

Table 4,

Table 5 and

Table 6, macro-average F1-scores plateaued around 0.82–0.83 across all feature groups, with anomaly-class recall significantly reduced.

This behaviour is largely attributable to ambiguous training labels caused by the 7-cycle volatile window definition.

E. Cross-Configuration Comparison.

A global comparison of all models, summarised in

Table 7, highlights the superiority of the sequence-to-time-step LSTM configurations, which achieved the highest AUC values (0.960–0.975), with the 33-feature model performing best. These models consistently outperformed the sequence-to-sequence configurations, which reached lower AUC values in the range of 0.89–0.91 due to the inherent label ambiguity introduced by multi-step volatile windows. Overall, the results confirm that short-horizon temporal modelling provides the most reliable discrimination between stable and unstable melt-flow conditions in industrial injection moulding.

Although the primary focus of this work is on modelling melt-instability dynamics, it is worth noting the practical considerations that support deployment in industrial edge environments. The proposed LSTM models operate on a compact set of routinely collected machine signals, require modest computational resources due to their single-layer architecture, and do not rely on high-dimensional temporal reconstructions or large memory buffers. These characteristics make the approach compatible with typical on-machine controllers or embedded monitoring units, where processing power and latency constraints must be respected. While a full edge-deployment study is beyond the scope of this work, these properties indicate that the framework is suitable for integration into real-time monitoring pipelines in industrial settings.

Overall, model performance is affected by class imbalance, label ambiguity arising from volatile windows, and sensitivity to operational disturbances, reflecting the inherent complexity of real industrial injection moulding processes.