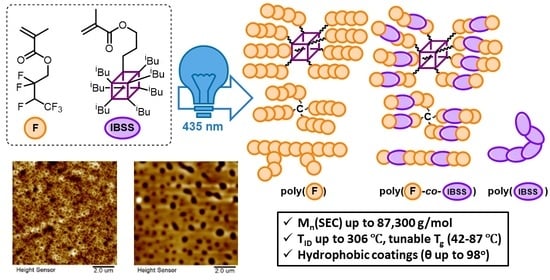

Organocatalyzed Atom Transfer Radical (Co)Polymerization of Fluorinated and POSS-Containing Methacrylates: Synthesis and Properties of Linear and Star-Shaped (Co)Polymers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.3. Polymerization Procedures

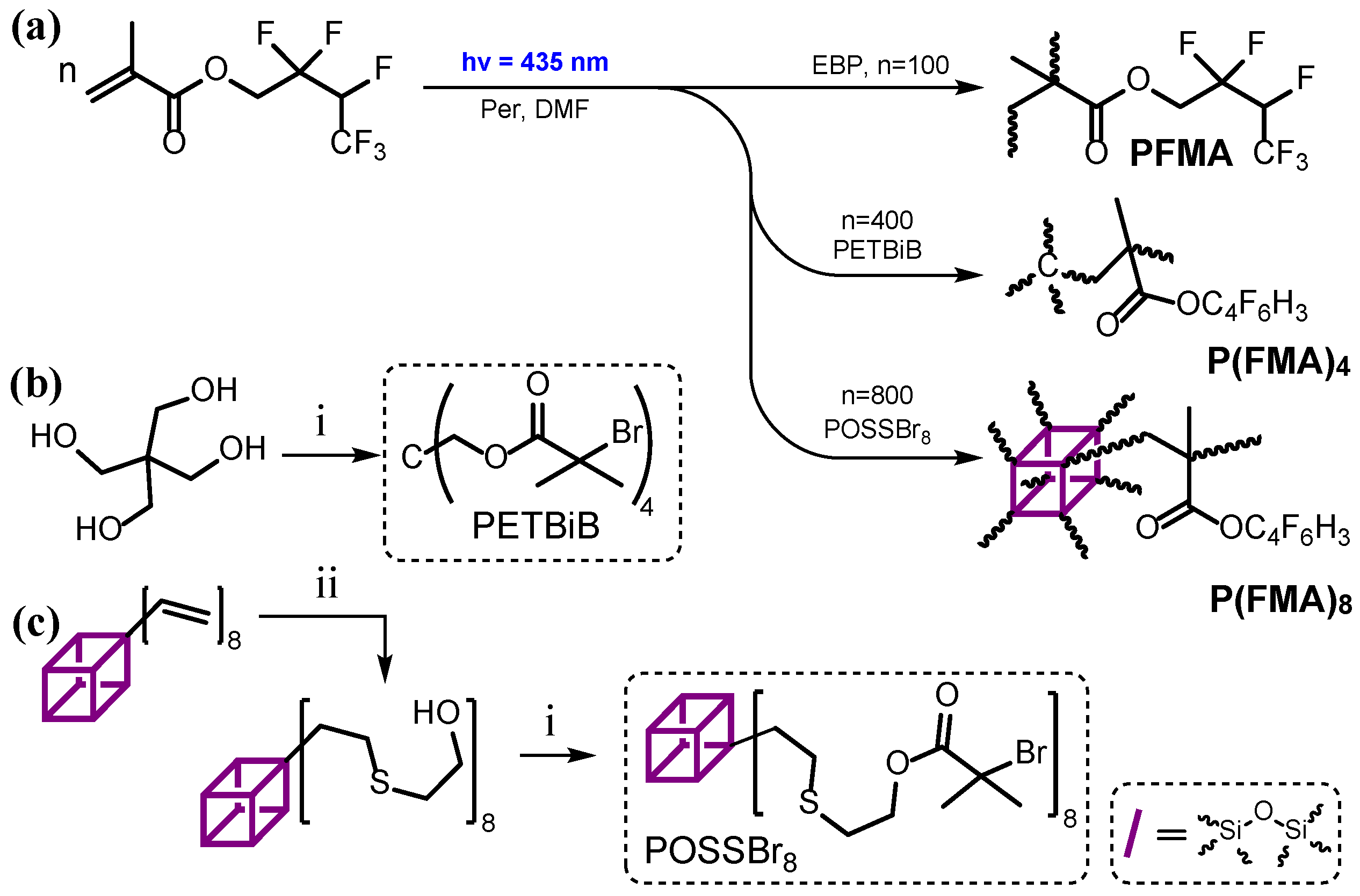

2.3.1. Synthesis of FMA-Based Homopolymers with Various Architectures

2.3.2. Synthesis of IBSS-Based Homopolymers with Various Architectures

2.3.3. Synthesis of Random Copolymers Based on FMA and IBSS with Various Architectures

3. Results and Discussion

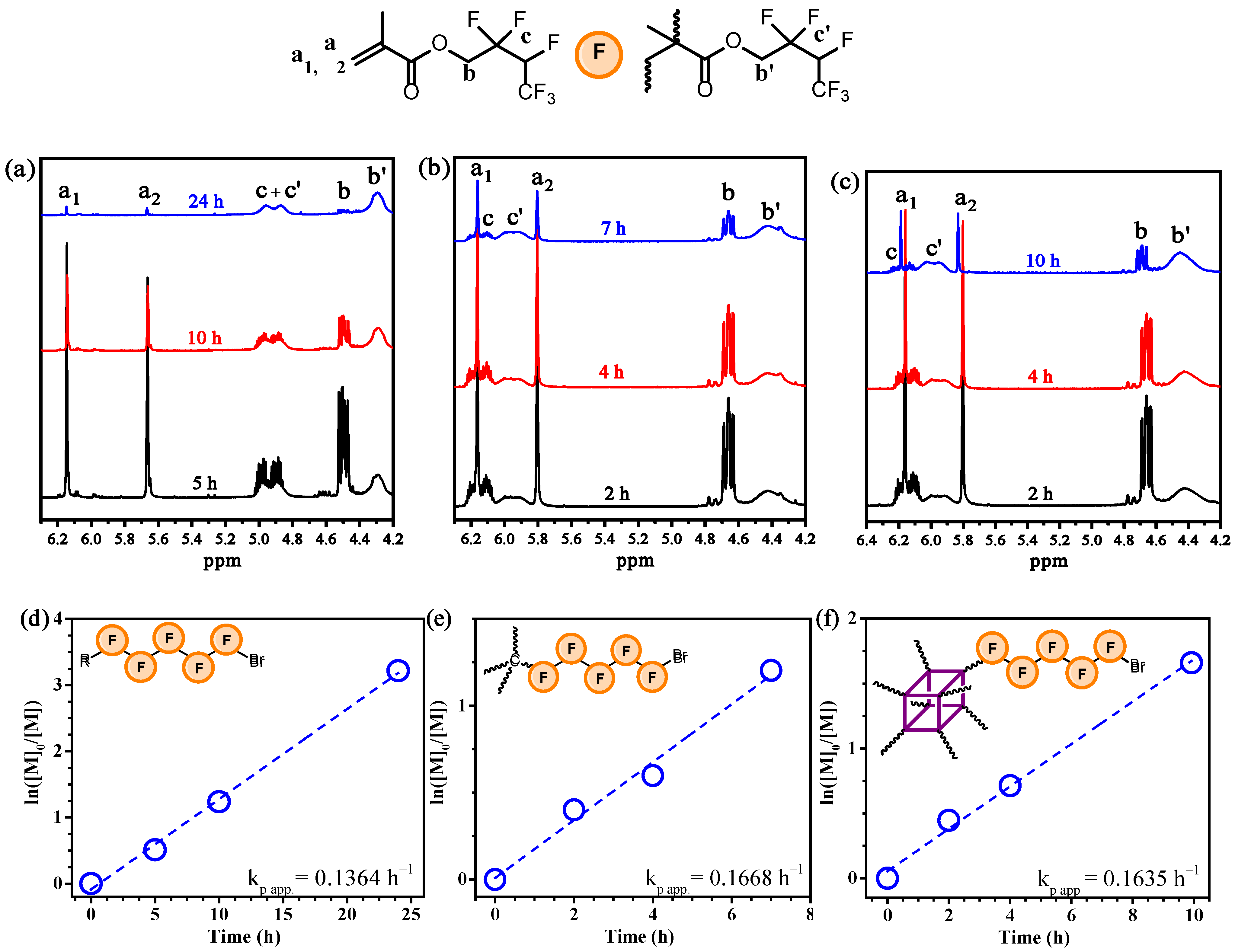

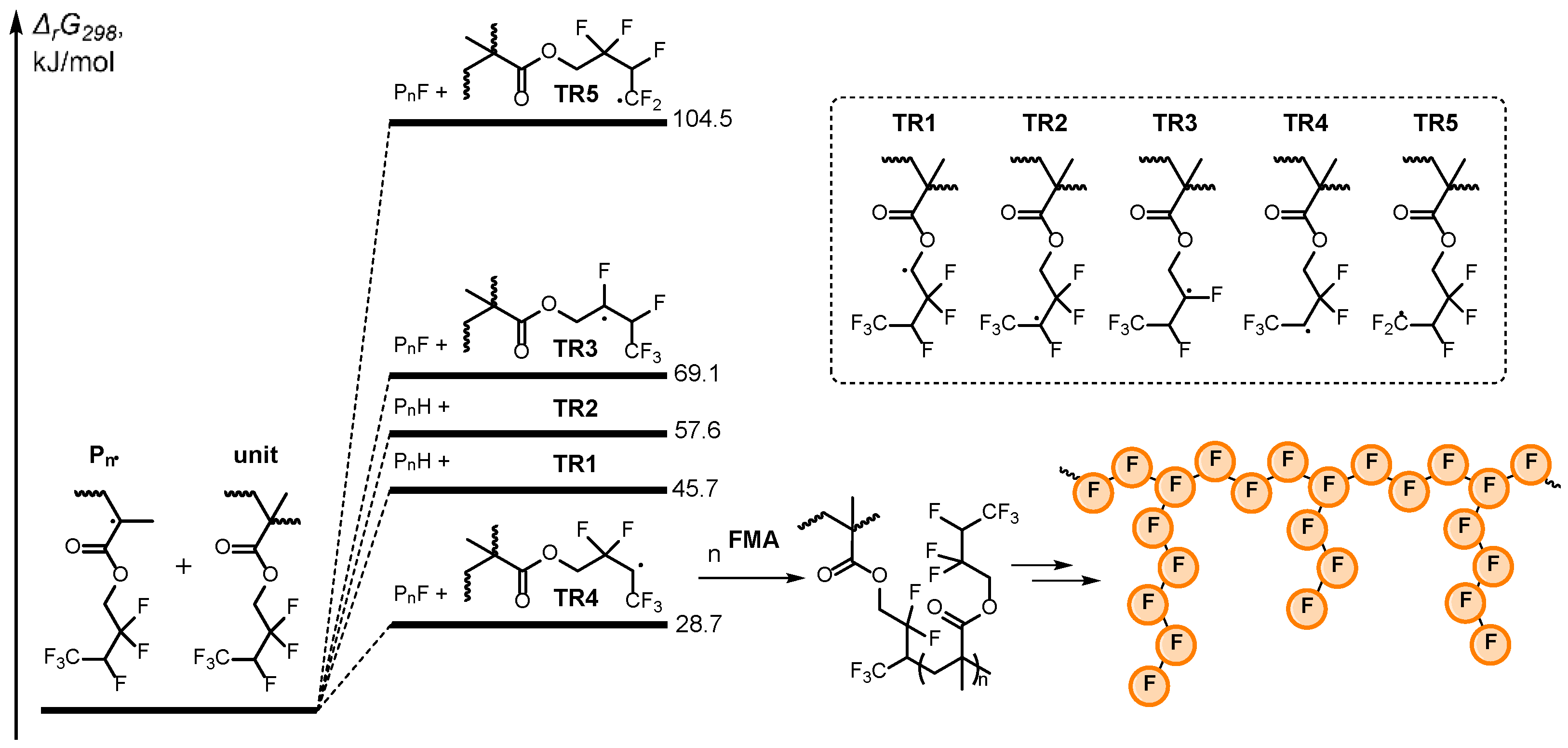

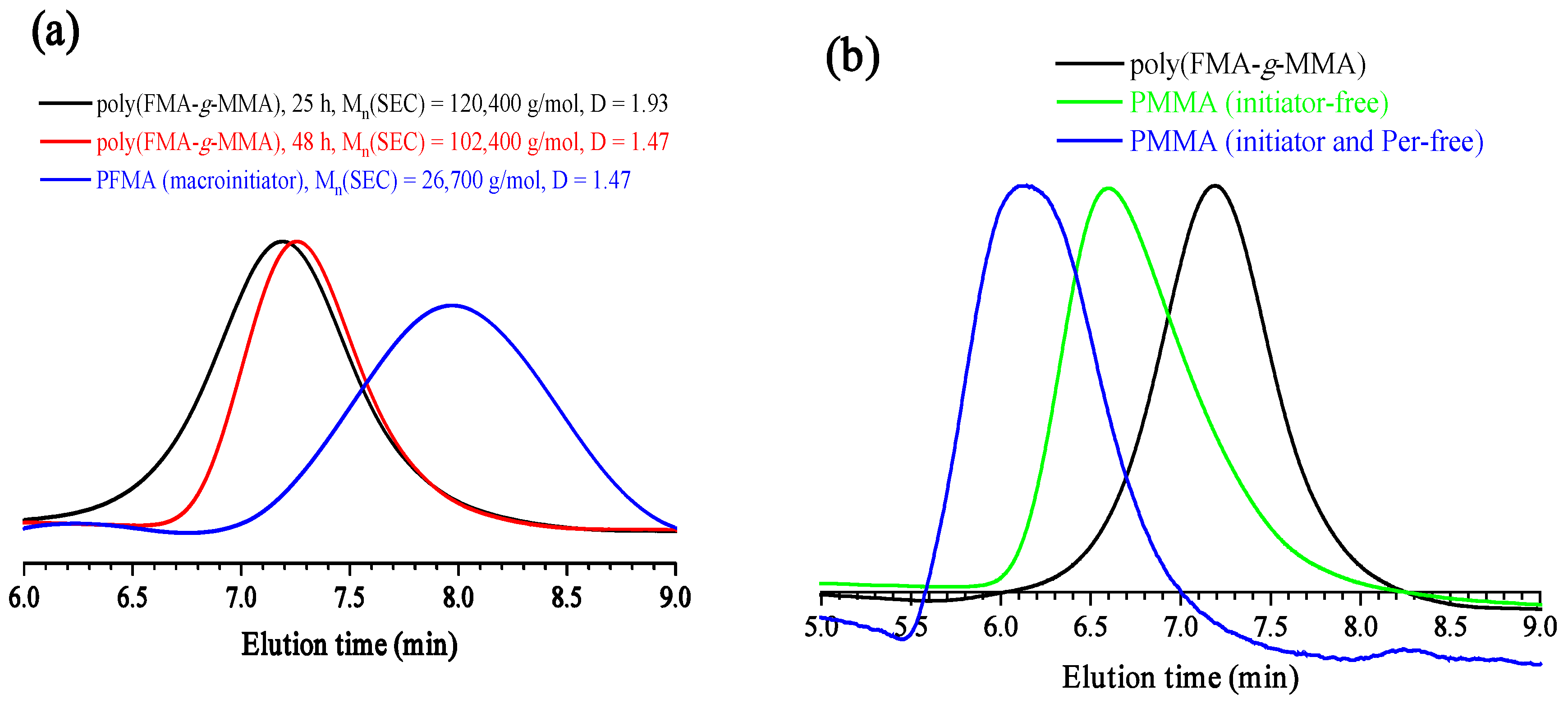

3.1. Polymerization of FMA

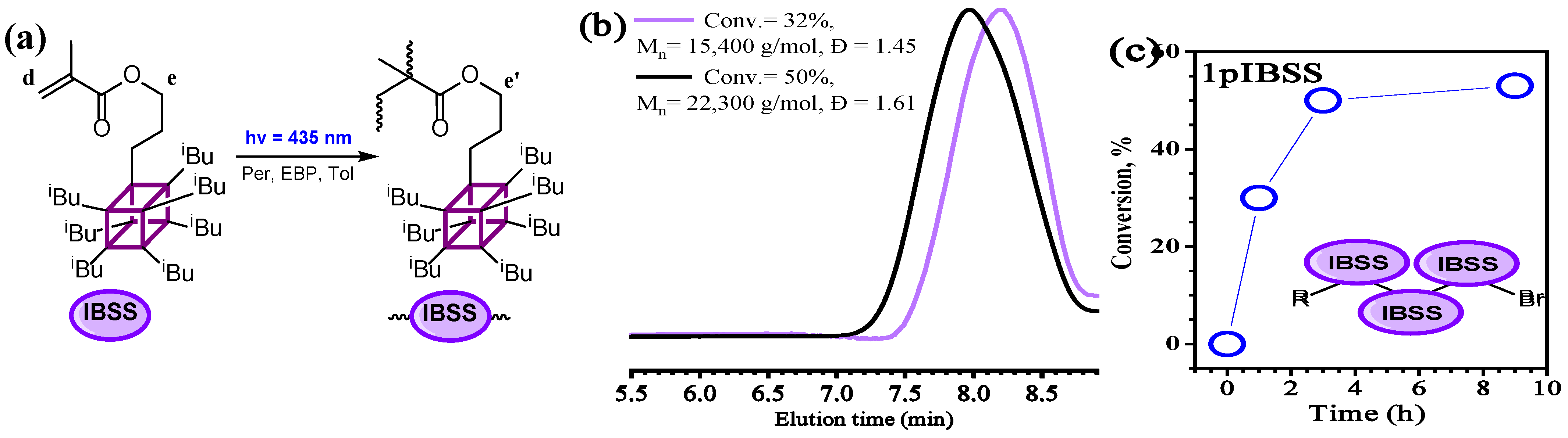

3.2. Polymerization of IBSS

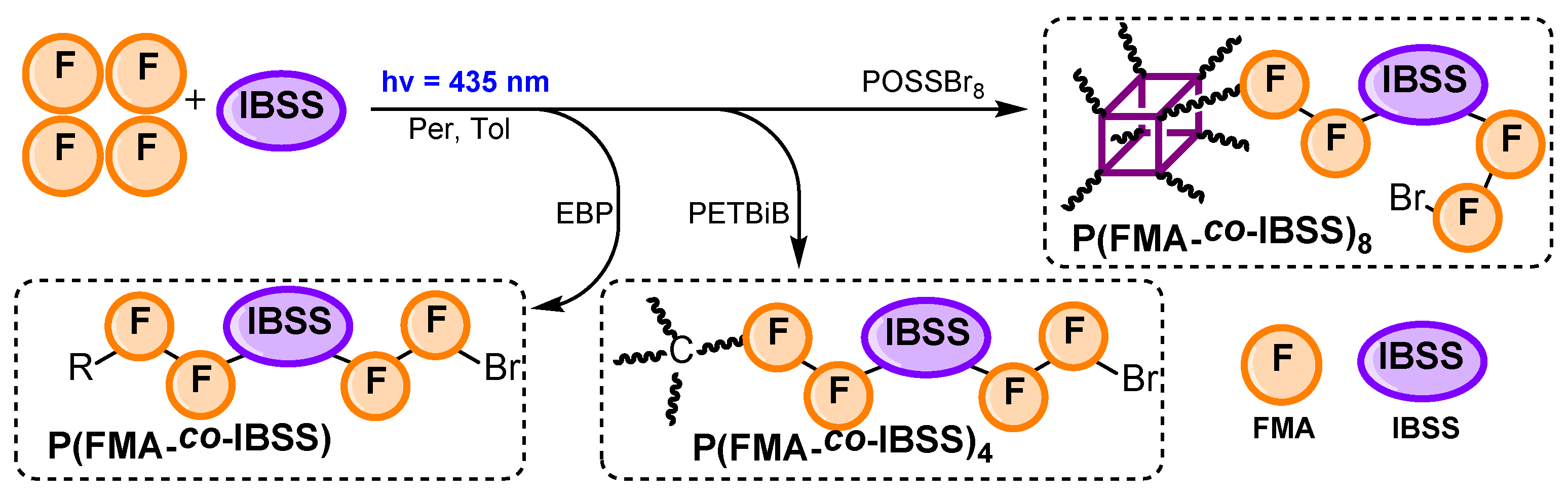

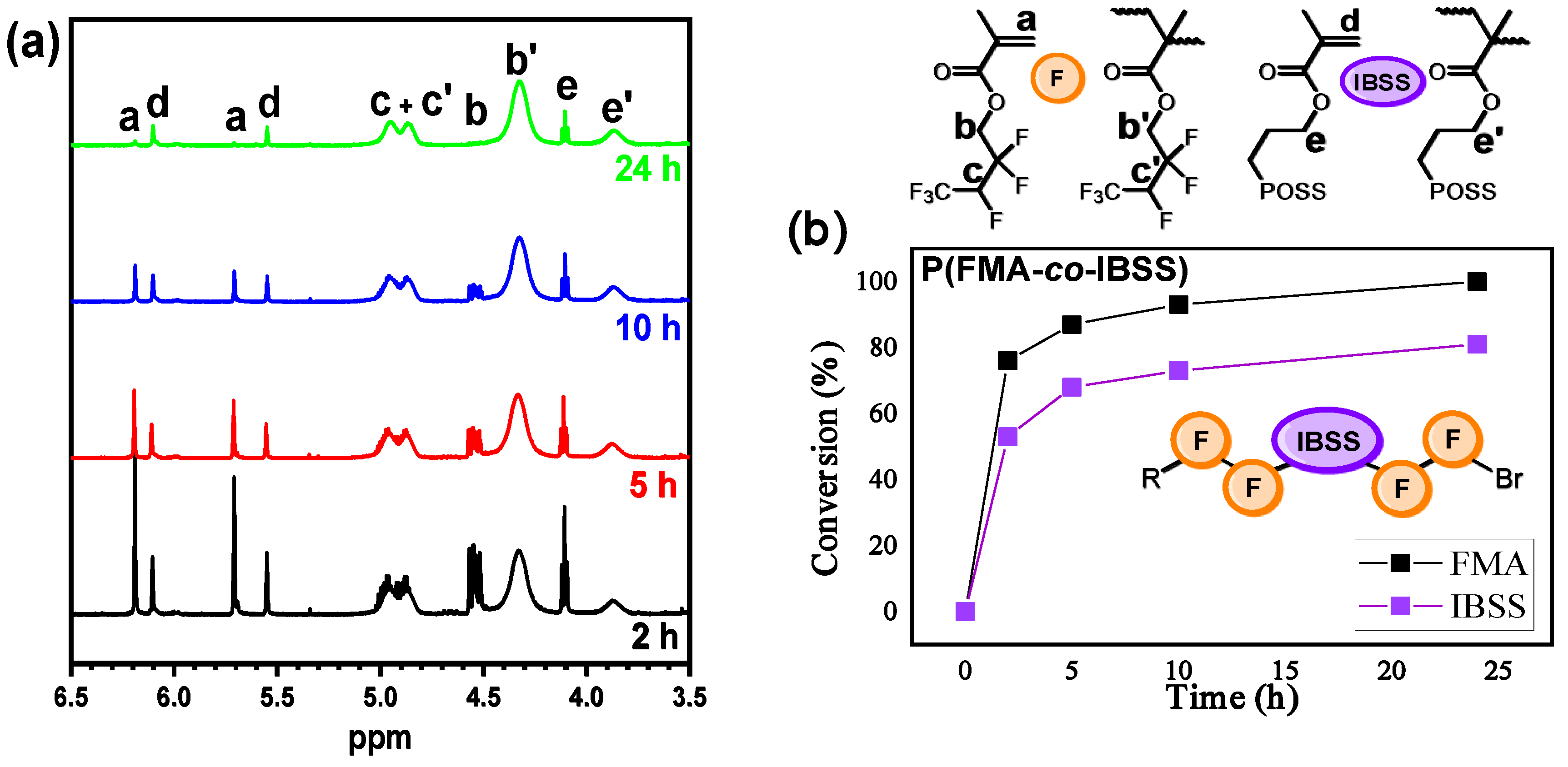

3.3. Copolymerization of FMA with IBSS

3.4. Thermal Properties

3.5. Solvophobic Properties

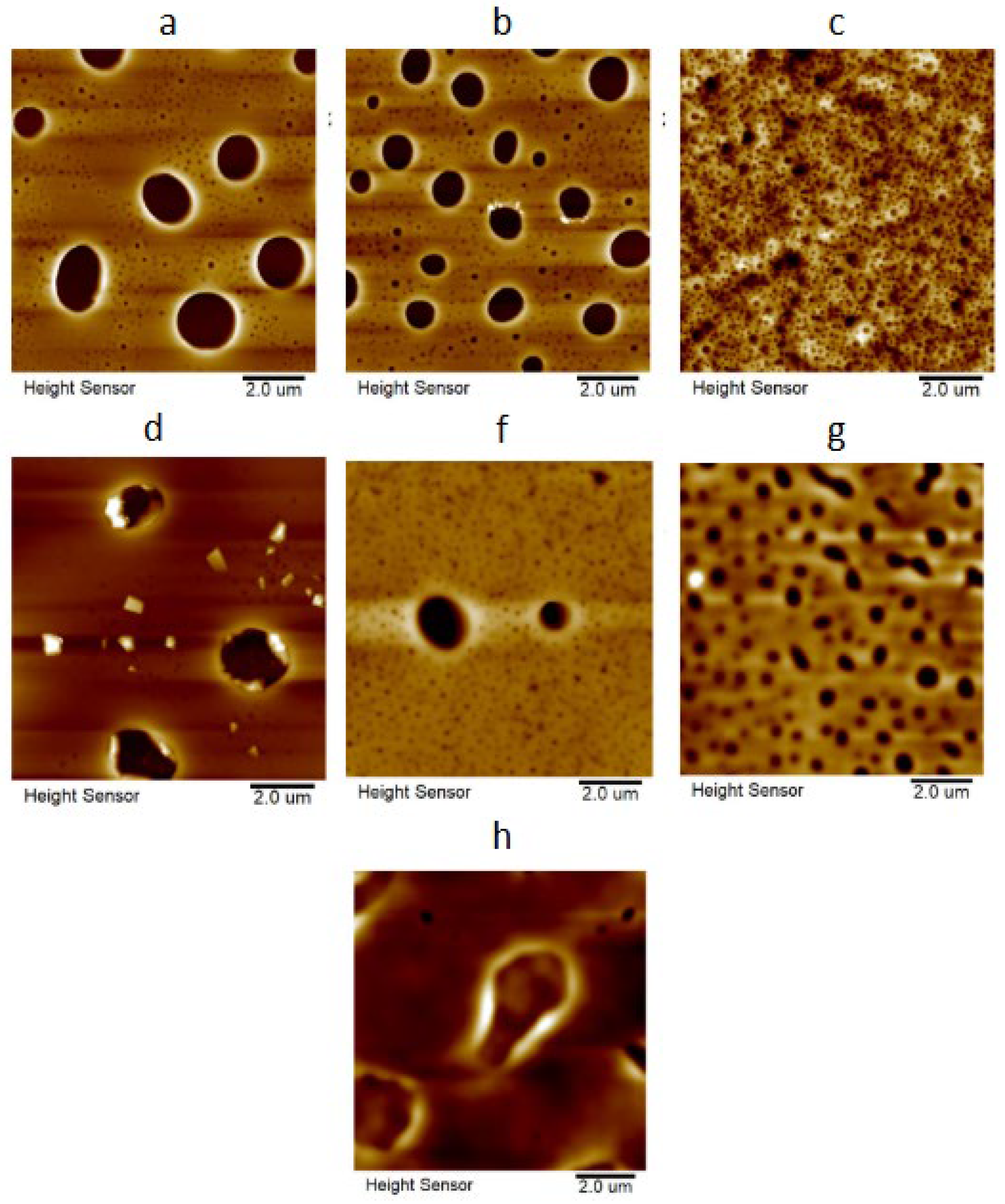

3.6. Atomic Force Microscopy

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ATRP | Atom-transfer radical polymerization |

| DBPO | Diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide |

| DFT | Density functional theory |

| IBSS | Methacryloxypropyl-substituted poly(isobutyl-T8-silsesquioxane) |

| FMA | 2,2,3,4,4,4-Hexafluorobutyl methacrylate |

| MMA | Methyl methacrylate |

| O-ATRP | Organocatalyzed atom-transfer radical polymerization |

| Per | Perylene |

| PIBSS | Linear poly(methacryloxypropyl-substituted poly(isobutyl-T8-silsesquioxane)) |

| P(IBSS)4 | 4-armed star-shaped poly(methacryloxypropyl-substituted poly(isobutyl-T8-silsesquioxane)) |

| PFMA | Linear poly(2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl methacrylate) |

| P(FMA)4 | 4-armed star-shaped poly(2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl methacrylate) |

| P(FMA)8 | 8-armed star-shaped poly(2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl methacrylate) |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS) | Linear poly(2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl methacrylate-co-methacryloxypropyl-substituted poly(isobutyl-T8-silsesquioxane)) |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS)4 | 4-armed star-shaped poly(2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl methacrylate-co-methacryloxypropyl-substituted poly(isobutyl-T8-silsesquioxane)) |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS)8 | 8-armed star-shaped poly(2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl methacrylate-co-methacryloxypropyl-substituted poly(isobutyl-T8-silsesquioxane)) |

| PMMA | Poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Additional Polymerization Experiments

References

- Zhao, F.; Guan, J.; Bai, W.; Gu, T.; Liao, S. Transparent, thermal stable and hydrophobic coatings from fumed silica/fluorinated polyacrylate composite latex via in situ miniemulsion polymerization. Prog. Org. Coat. 2019, 131, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Gao, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, G.; Hodges, C.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H. Preparation and UV aging of nano-SiO2/fluorinated polyacrylate polyurethane hydrophobic composite coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2020, 141, 105556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.H.; Pan, H.; Wang, L.M.; Shen, Y.; Ding, Y. Preparation of fluorine-free superhydrophobic cotton fabric with polyacrylate/SiO2 nanocomposite. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2020, 20, 2292–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, T.; Meguro, M.; Nakamae, K.; Matsushita, M.; Ueda, Y. The lowest surface free energy based on -CF3 alignment. Langmuir 1999, 15, 4321–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, K.; Morita, M.; Otsuka, H.; Takahara, A. Molecular aggregation structure and surface properties of poly(fluoroalkyl acrylate) thin films. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 5699–5705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, J.-S.; Lee, T.R. The wettability of fluoropolymer surfaces: Influence of surface dipoles. Langmuir 2008, 24, 4817–4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuura, T.; Ando, S.; Sasaki, S.; Yamamoto, F. Polyimides derived from 2,2′-bis(trifluoromethyl)-4,4′-diaminobiphenyl. 4. Optical properties of fluorinated polyimides for optoelectronic components. Macromolecules 1994, 27, 6665–6670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-P.; Lee, W.-Y.; Kang, J.-W.; Kwon, S.-K.; Kim, J.-J.; Lee, J.-S. Fluorinated poly(arylene ether sulfide) for polymeric optical waveguide devices. Macromolecules 2001, 34, 7817–7821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Chang, Y.; Oh, S.-H.; Kim, S.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, J.-K.; Choi, S.-H.; Lim, J. Fluorous dispersion ring-opening metathesis polymerization. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 1515–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Peng, Z.; Pan, Q.; Liu, S.; Zhao, J. Effect of fluorinated substituents on solubility and dielectric properties of the liquid crystalline poly(ester imides). ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, T.; Su, Q.; Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; Long, S.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J. A novel high-performance composite material with low dielectric constant and excellent hydrophobicity. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 10248–10263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zheng, Z.; Gong, D.; Tian, C.; Wen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, J. Synthesis and characterization of fluorinated poly(aryl ether)s with excellent dielectric properties. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffini, G.; Levi, M.; Turri, S. Novel crosslinked host matrices based on fluorinated polymers for long-term durability in thin-film luminescent solar concentrators. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2013, 118, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-F.; Sekine, T.; Takeda, Y.; Yokosawa, K.; Matsui, H.; Kumaki, D.; Shiba, T.; Nishikawa, T.; Tokito, S. Fully printed PEDOT:PSS-based temperature sensor with high humidity stability for wireless healthcare monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Chen, N.; Hu, C.; Klok, H.-A.; Lee, Y.M.; Hu, X. Fluorinated poly(aryl piperidinium) membranes for anion exchange membrane fuel cells. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2210432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebnesajjad, S. (Ed.) Fluoroplastics, Volume 2: Melt Processible Fluoroplastics. The Definitive User’s Guide; William Andrew Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Scheirs, J. Modern Fluoropolymers: High Performance Polymers for Diverse Applications; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Ameduri, B.; Boutevin, B.; Kostov, G. Fluoroelastomers: Synthesis, properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2001, 26, 105–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameduri, B.; Boutevin, B. Well-Architectured Fluoropolymers: Synthesis, Properties and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ameduri, B.; Boutevin, B. Update on fluoroelastomers: From perfluoroelastomers to fluorosilicones and fluorophosphazenes. J. Fluor. Chem. 2005, 126, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.M.; Li, Y.; Wu, X.M.; Shan, X.F.; Wang, W.C. Synthesis and properties of fluoropolyacrylate coatings. Adv. Powder Technol. 2004, 15, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastoe, J.; Gold, S.; Steytler, D.C. Surfactants for CO2. Langmuir 2006, 22, 9832–9842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensley, J.E.; Way, J.D. Synthesis and characterization of perfluorinated carboxylate/sulfonate ionomer membranes for separation and solid electrolyte applications. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 4576–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riess, J.G. Highly fluorinated amphiphilic molecules and self-assemblies with biomedical potential. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 14, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Neoh, K.G.; Kang, E.T.; Teo, S.L.M. Surface-functionalized and surface-functionalizable poly(vinylidene fluoride) graft copolymer membranes via click chemistry and atom transfer radical polymerization. Langmuir 2011, 27, 2936–2945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsang, E.M.W.; Zhang, Z.B.; Yang, A.C.C.; Shi, Z.Q.; Peckham, T.J.; Narimani, R.; Frisken, B.J.; Holdcroft, S. Nanostructure, morphology, and properties of fluorous copolymers bearing ionic grafts. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 9467–9480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, D.B.; Lickiss, P.D.; Rataboul, F. Recent developments in the chemistry of cubic polyhedral oligosilsesquioxanes. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2081–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Müller, A.H.E. Architecture, self-assembly and properties of well-defined hybrid polymers based on polyhedral oligomeric silsequioxane (POSS). Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1121–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; Yang, S.; He, L.; Zhao, X. Star-shaped POSS diblock copolymers and their self-assembled films. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 27857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Pan, A.; He, L. POSS end-capped diblock copolymers: Synthesis, micelle self-assembly and properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 425, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Pyun, J.; Matyjaszewski, K. Synthesis of hybrid polymers using atom transfer radical polymerization: Homopolymers and block copolymers from polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane monomers. Macromolecules 2000, 33, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.-W.; Gao, S.-X.; Xu, K.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Peng, J.; Chen, M.-C. Synthesis and characterization of silsesquioxane-cored star-shaped hybrid polymer via “grafting from” RAFT polymerization. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 1696–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ata, S.; Dhara, P.; Mukherjee, R.; Singha, N.K. Thermally amendable and thermally stable thin film of POSS tethered Poly (methyl methacrylate)(PMMA) synthesized by ATRP. Eur. Polym. J. 2016, 75, 276–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W. Recent advances in organic-inorganic well-defined hybrid polymers using controlled living radical polymerization techniques. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 3950–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, L.; Zhuang, X.; Li, X.; Bai, J.; Chen, Y. Synthesis and self-assembly of tadpole-shaped organic/inorganic hybrid poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane via RAFT polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2008, 46, 7049–7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhuang, X.; Li, X.; Bai, J.; Chen, Y. Preparation and characterization of organic/inorganic hybrid polymers containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane via RAFT polymerization. React. Funct. Polym. 2009, 69, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mya, K.Y.; Lin, E.M.; Gudipati, C.S.; Shen, L.; He, C. Time-dependent polymerization kinetic study and the properties of hybrid polymers with functional silsesquioxanes. J. Phys. Chem. B 2010, 114, 9119–9127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Bernard, J.; Alcouffe, P.; Galy, J.; Dai, L.; Gérard, J.F. Nanostructured hybrid polymer networks from in situ self-assembly of RAFT-synthesized POSS-based block copolymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 4343–4352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegou, E.; Bellas, V.; Gogolides, E.; Argitis, P. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) acrylate copolymers for microfabrication: Properties and formulation of resist materials. Microelectron. Eng. 2004, 73, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Yu, B.; Jiang, X.; Yin, J. Hybrid core-shell microspheres from coassembly of anthracene-containing POSS (POSS-AN) and anthracene-ended hyperbranched poly(ether amine)(hPEA-AN) and their responsive polymeric hollow microspheres. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 3519–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, P.; Müller, A.H.; Zhang, W. Hollow polymeric capsules from POSS-based block copolymer for photodynamic therapy. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 8440–8448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.; Ma, X.; Li, Z.; Hou, X. Synthesis of star-shaped polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) fluorinated acrylates for hydrophobic honeycomb porous film application. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2014, 292, 1531–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, A.; He, L.; Wang, L.; Xi, N. POSS-based diblock fluoropolymer for self-assembled hydrophobic coatings. Mater. Today Proc. 2016, 3, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araki, H.; Naka, K. Syntheses of dumbbell-shaped trifluoropropyl-substituted POSS derivatives linked by simple aliphatic chains and their optical transparent thermoplastic films. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 6039–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.; Wei, Y.; Chen, B.; Mu, J. Polymerization of polyhedral oligomeric silsequioxane (POSS) with perfluoro-monomers and a kinetic study. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 10700–10706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatani, R.; Takano, H.; Wang, L.; Chandra, A.; Tanaka, Y.; Maeda, R.; Kihara, N.; Minegishi, S.; Miyagi, K.; Kasahara, Y. Precise synthesis of fluorine-containing block copolymers via RAFT. J. Photopolym. Sci. Technol. 2016, 29, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponnupandian, S.; Chakrabarty, A.; Mondal, P.; Hoogenboom, R.; Lowe, A.B.; Singha, N.K. POSS and fluorine containing nanostructured block copolymer: Synthesis via RAFT polymerization and its application as hydrophobic coating material. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 131, 109679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Szczepaniak, G.; Dadashi-Silab, S.; Lin, T.C.; Kowalewski, T.; Matyjaszewski, K. Cu-catalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization: The effect of cocatalysts. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2022, 224, 2200347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, C.; Corrigan, N.A.; Jung, K.; Nguyen, D.; Nguyen, T.K.; Adnan, N.N.M.; Oliver, S.; Shanmugam, S.; Yeow, J. Copper-mediated living radical polymerization (atom transfer radical polymerization and copper(0) mediated polymerization): From fundamentals to bioapplications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 1803–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, J.P.; Federico, C.R.; Lim, C.H.; Miyake, G.M. Photoinduced organocatalyzed atom-transfer radical polymerization using low ppm catalyst loading. Macromolecules 2019, 52, 747–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theriot, J.C.; McCarthy, B.G.; Lim, C.H.; Miyake, G.M. Organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization: Perspectives on catalyst design and performance. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2017, 38, 1700040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.J.; Puffer, K.O.; Kudisch, M.; Knies, D.; Miyake, G.M. Structure-property relationships of core-substituted diaryl dihydrophenazine organic photoredox catalysts and their application in O-ATRP. Polym. Chem. 2021, 12, 6110–6122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y.; Song, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Liao, S. Sulfur-doped anthanthrenes as effective organic photocatalysts for metal-free ATRP and PET-RAFT polymerization under blue and green light. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 4134–4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, C.; Liu, W. Toward the rational design of organic catalysts for organocatalysed atom transfer radical polymerisation. Polymers 2024, 16, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbin, D.A.; Miyake, G.M. Photoinduced organocatalyzed atom transfer radical polymerization (o-atrp): Precision polymer synthesis using organic photoredox catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 1830–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelmer, C.; Wang, D.K.; Keen, I.; Hill, D.J.T.; Symons, A.L.; Walsh, L.J.; Rasoul, F. Synthesis and characterization of POSS-(PAA)8 star copolymers and GICs for dental applications. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, e82–e92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaitusionak, A.A.; Vasilenko, I.V.; Sych, G.; Kashina, A.V.; Simokaitiene, J.; Grazulevicius, J.V.; Kostjuk, S.V. Atom-transfer radical homo- and copolymerization of carbazole-substituted styrene and perfluorostyrene. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 134, 109843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, G.M.; Theriot, J.C. Perylene as an organic photocatalyst for the radical polymerization of functionalized vinyl monomers through oxidative quenching with alkyl bromides and visible light. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 8255–8261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.P. The theory of reactions involving proton transfers. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1936, 154, 414–429. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.G.; Polanyi, M. Further considerations on the thermodynamics of chemical equilibria and reaction rates. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1936, 32, 1333–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moad, G.; Solomon, D.H. Radical Reaction the Chemistry of Radical Polymerization, 2nd ed.; Elsevier Science & Technology: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 11–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dolbier, W.R. Topics in Current Chemistry: Fluorinated Free Radicals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 97–163. [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, S.; Lee, M.W.; Grady, M.C.; Soroush, M.; Rappe, A.M. Computational evidence for self-initiation in spontaneous high-temperature polymerization of methyl methacrylate. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 1125–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutahya, C.; Aykac, F.S.; Yilmaz, G.; Yagci, Y. LED and visible light-induced metal free ATRP using reducible dyes in the presence of amines. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 6094–6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.K.; Yu, C.; Badgujar, S.; Kim, Y.; Kwon, Y.; Kim, D.; Lee, J.; Akhter, T.; Thangavel, G.; Park, L.S.; et al. Highly efficient organic photocatalysts discovered via a computer-aided-design strategy for visible-light-driven atom transfer radical polymerization. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 794–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treat, N.J.; Sprafke, H.; Kramer, J.W.; Clark, P.G.; Barton, B.E.; Read de Alaniz, J.; Fors, B.P.; Hawker, C.J. Metal-free atom transfer radical polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16096–16101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.; Fang, C.; Fantin, M.; Malhotra, N.; So, W.Y.; Peteanu, L.A.; Isse, A.A.; Gennaro, A.; Liu, P.; Matyjaszewski, K. Mechanism of photoinduced metal-free atom transfer radical polymerization: Experimental and computational studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 2411–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzalaco, S.; Fantin, M.; Scialdone, O.; Galia, A.; Isse, A.A.; Gennaro, A.; Matyjaszewski, K. Atom transfer radical polymerization with different halides (F, Cl, Br, and I): Is the process “living” in the presence of fluorinated initiators? Macromolecules 2016, 50, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Li, Q.; Peng, B.; Tan, S.; Zhang, Z. Grafting modification of poly(vinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene) via Cu(0) mediated controlled radical polymerization. React. Funct. Polym. 2021, 164, 104939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lei, M.; Tan, S.; Zhang, Z. Grafting modification of poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) via visible-light mediated C–F bond activation. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2022, 223, 2200041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raus, V.; Čadová, E.; Starovoytova, L.; Janata, M. ATRP of POSS monomers revisited: Toward high-molecular weight methacrylate–POSS (co)polymers. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 7311–7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T.; Leolukman, M.; Jin, S.; Goseki, R.; Ishida, Y.; Kakimoto, M.; Hayakawa, T.; Ree, M.; Gopalan, P. Hierarchical self-assembled structures from POSS-containing block copolymers synthesized by living anionic polymerization. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 8835–8843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, F.R.; Lewis, F.M. Copolymerization. I. A basis for comparing the behavior of monomers in copolymerization; The copolymerization of styrene and methyl methacrylate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1944, 66, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, J.M.G.; Arrighi, V. Polymers: Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials, 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Habibu, S.; Sarih, N.M.; Sairi, N.A.; Zulkifli, M. Rheological and thermal degradation properties of hyperbranched polyisoprene prepared by anionic polymerization. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 190869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, F.M.; Levchik, G.F.; Levchik, S.V.; Dick, C.; Liggat, J.J.; Snape, C.E.; Wilkie, C.A. The thermal stability of cross-linked polymers: Methyl methacrylate with divinylbenzene and styrene with dimethacrylates. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2001, 71, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Förch, R.; Schönherr, H.; Jenkins, T. Surface Design: Applications in Bioscience and Nanotechnology; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2009; pp. 471–473. [Google Scholar]

- Brady, J.M.; Thomas, E.L. Effect of short-chain branching on the morphology of LLDPE-oriented thin films. J. Polym. Sci. B Polym. Phys. 1988, 26, 2385–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymer | Time (h) | Conv. 2 (%) | Mn(SEC) (g/mol) | Đ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFMA | 5 | 40 | 26,600 | 1.77 |

| 10 | 71 | 22,700 | 2.05 | |

| 24 | 96 | 25,600 | 1.73 | |

| 48 | 100 | 28,100 | 1.41 | |

| P(FMA)4 | 2 | 33 | 46,000 | 1.37 |

| 4 | 45 | 40,700 | 1.52 | |

| 7 | 70 | 38,000 | 1.45 | |

| 24 | 100 | 37,400 | 1.59 | |

| P(FMA)8 | 2 | 36 | 53,100 | 1.78 |

| 4 | 51 | 47,700 | 1.41 | |

| 10 | 81 | 42,800 | 1.89 | |

| 48 | 100 | 38,100 | 2.08 |

| Polymer | Time (h) | Conv. 2 (%) | Mn(Theor.) (g/mol) | Mn(SEC) (g/mol) | Mn(Corr.) 3 (g/mol) | IE 4 (%) | Đ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIBSS | 1 | 32 | 30,200 | 15,400 | 43,800 | 68.9 | 1.45 |

| 9 | 50 | 47,200 | 22,300 | 69,300 | 68.1 | 1.61 | |

| 24 | 53 | 50,000 | 22,700 | 70,800 | 70.6 | 1.60 | |

| P(IBSS)4 | 24 | 7 | 26,400 | 2200 | - | - | 1.13 |

| Polymer | Time (h) | Conv. 2 (%) | χ(FMA)/χ(IBSS) 3 | Mn(SEC) (g/mol) | Đ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMA | IBSS | Common | |||||

| P(FMA-co-IBSS) | 2 | 76 | 53 | 71 | 85/15 | 27,900 | 1.56 |

| 5 | 87 | 68 | 83 | 84/16 | 27,300 | 1.88 | |

| 10 | 93 | 73 | 89 | 84/16 | 29,900 | 1.65 | |

| 24 | 100 | 81 | 96 | 83/17 | 30,100 | 1.64 | |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS)4 | 24 | 98 | 90 | 96 | 81/19 | 79,800 | 3.80 |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS)8 | 24 | 92 | 62 | 86 | 86/14 | 87,300 | 2.74 |

| Polymer | Mn(SEC) (g/mol) | Tg 1 (°C) | TID 2 (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFMA | 28,100 | 53 | 256 |

| P(FMA)4 | 37,400 | 55 | 262 |

| P(FMA)8 | 38,100 | 58 | 306 |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS) | 30,100 | 55 | 239 |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS)4 | 79,800 | 67 | 259 |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS)8 | 87,300 | 65 | 292 |

| PIBSS | 22,700 | 85 | 362 |

| Contact Liquid | Glass | PFMA | P(FMA)4 | P(FMA)8 | P(FMA-co-IBSS) | P(FMA-co-IBSS)4 | P(FMA-co-IBSS)8 | PIBSS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| water | 61.2 ± 3.1 | 96.1 ± 0.5 | 90.4 ± 0.4 | 89.2 ± 0.2 | 91.3 ± 2.1 | 93.6 ± 0.3 | 95.6 ± 0.2 | 97.5 ± 0.2 |

| oil | 45.9 ± 0.6 | 46.2 ± 2.3 | 46.5 ± 0.9 | 46.8 ± 1.9 | 41.8 ± 1.6 | 41.6 ± 2.0 | 42.1 ± 1.5 | 33.0 ± 1.2 |

| Polymer | Film Thickness (nm) | Film Roughness (nm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Area | Without Counting Large Holes | ||

| PFMA | 73.2 ± 13.2 | 33.7 ± 4.8 | 11.5 ± 0.9 |

| P(FMA)4 | 102.4 ± 9.7 | 21.3 ± 3.1 | 7.5 ± 1.3 |

| P(FMA)8 | 175.0 ± 9.2 | 6.7 ± 2.6 | 5.6 ± 2.5 |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS) | 105.9 ± 3.3 | 32.0 ± 15.8 | 11.6 ± 5.5 |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS)4 | 190.9 ± 23.6 | 33.9 ± 12.4 | 13.3 ± 2.2 |

| P(FMA-co-IBSS)8 | 114.4 ± 18.8 | 6.4 ± 1.0 | 6.4 ± 1.0 |

| PIBSS | 136.1 ± 1.8 | 18.3 ± 12.3 | 10.0 ± 2.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Baravoi, H.; Belavusau, H.; Vaitusionak, A.; Kukanova, V.; Frolova, A.; Timashev, P.; Liu, H.; Kostjuk, S. Organocatalyzed Atom Transfer Radical (Co)Polymerization of Fluorinated and POSS-Containing Methacrylates: Synthesis and Properties of Linear and Star-Shaped (Co)Polymers. Polymers 2026, 18, 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010141

Baravoi H, Belavusau H, Vaitusionak A, Kukanova V, Frolova A, Timashev P, Liu H, Kostjuk S. Organocatalyzed Atom Transfer Radical (Co)Polymerization of Fluorinated and POSS-Containing Methacrylates: Synthesis and Properties of Linear and Star-Shaped (Co)Polymers. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):141. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010141

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaravoi, Hleb, Heorhi Belavusau, Aliaksei Vaitusionak, Valeriya Kukanova, Anastasia Frolova, Peter Timashev, Hongzhi Liu, and Sergei Kostjuk. 2026. "Organocatalyzed Atom Transfer Radical (Co)Polymerization of Fluorinated and POSS-Containing Methacrylates: Synthesis and Properties of Linear and Star-Shaped (Co)Polymers" Polymers 18, no. 1: 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010141

APA StyleBaravoi, H., Belavusau, H., Vaitusionak, A., Kukanova, V., Frolova, A., Timashev, P., Liu, H., & Kostjuk, S. (2026). Organocatalyzed Atom Transfer Radical (Co)Polymerization of Fluorinated and POSS-Containing Methacrylates: Synthesis and Properties of Linear and Star-Shaped (Co)Polymers. Polymers, 18(1), 141. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010141