Dual-Band Electrochromic Poly(Amide-Imide)s with Redox-Stable N,N,N’,N’-Tetraphenyl-1,4-Phenylenediamine Segments

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

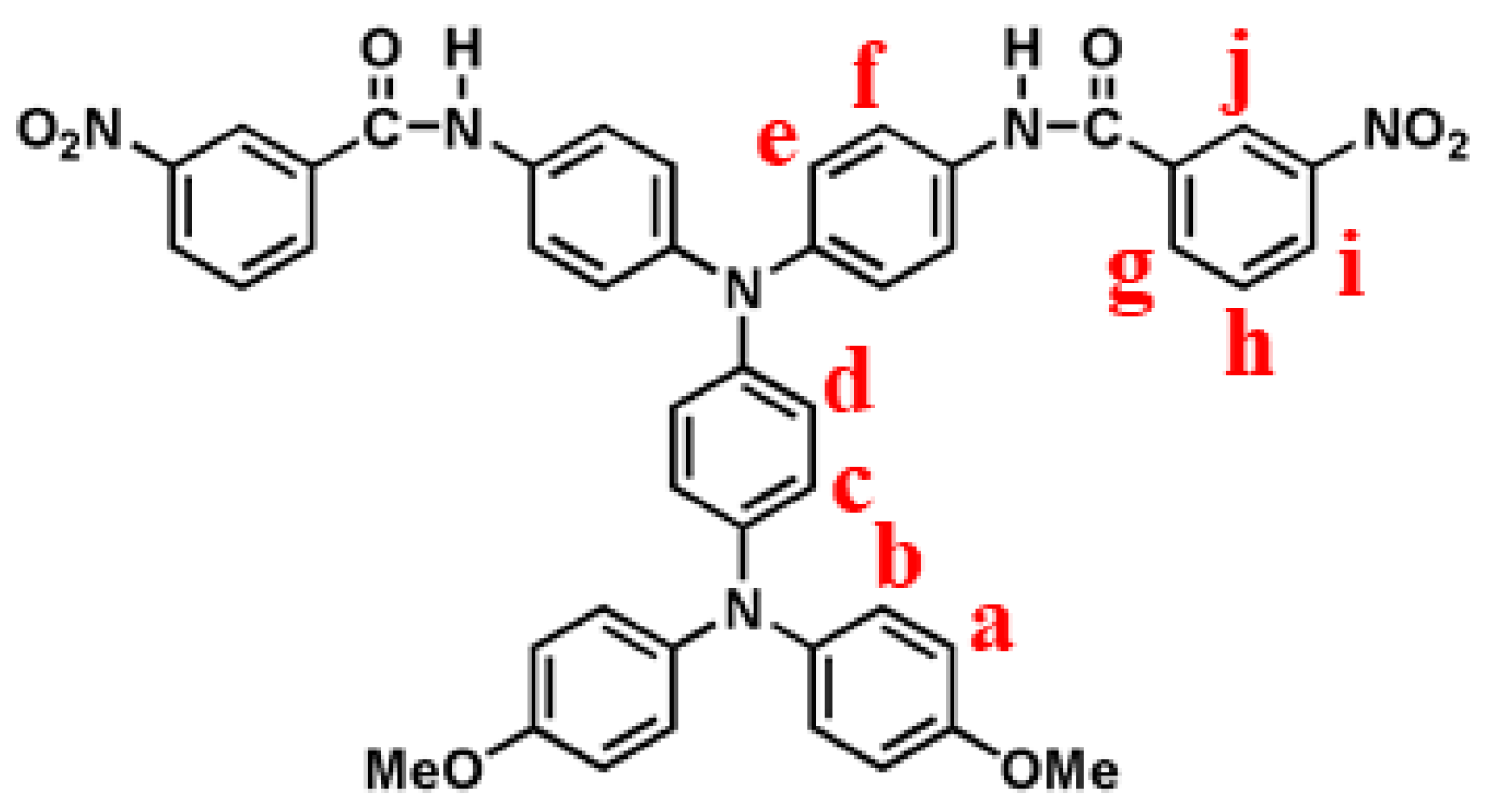

2.2. Synthesis of N,N-Bis(4-(3-Nitrobenzamido)Phenyl)-N’,N’-Bis(4-Methoxyphenyl)- 1,4-Phenylenediamine (m-5)

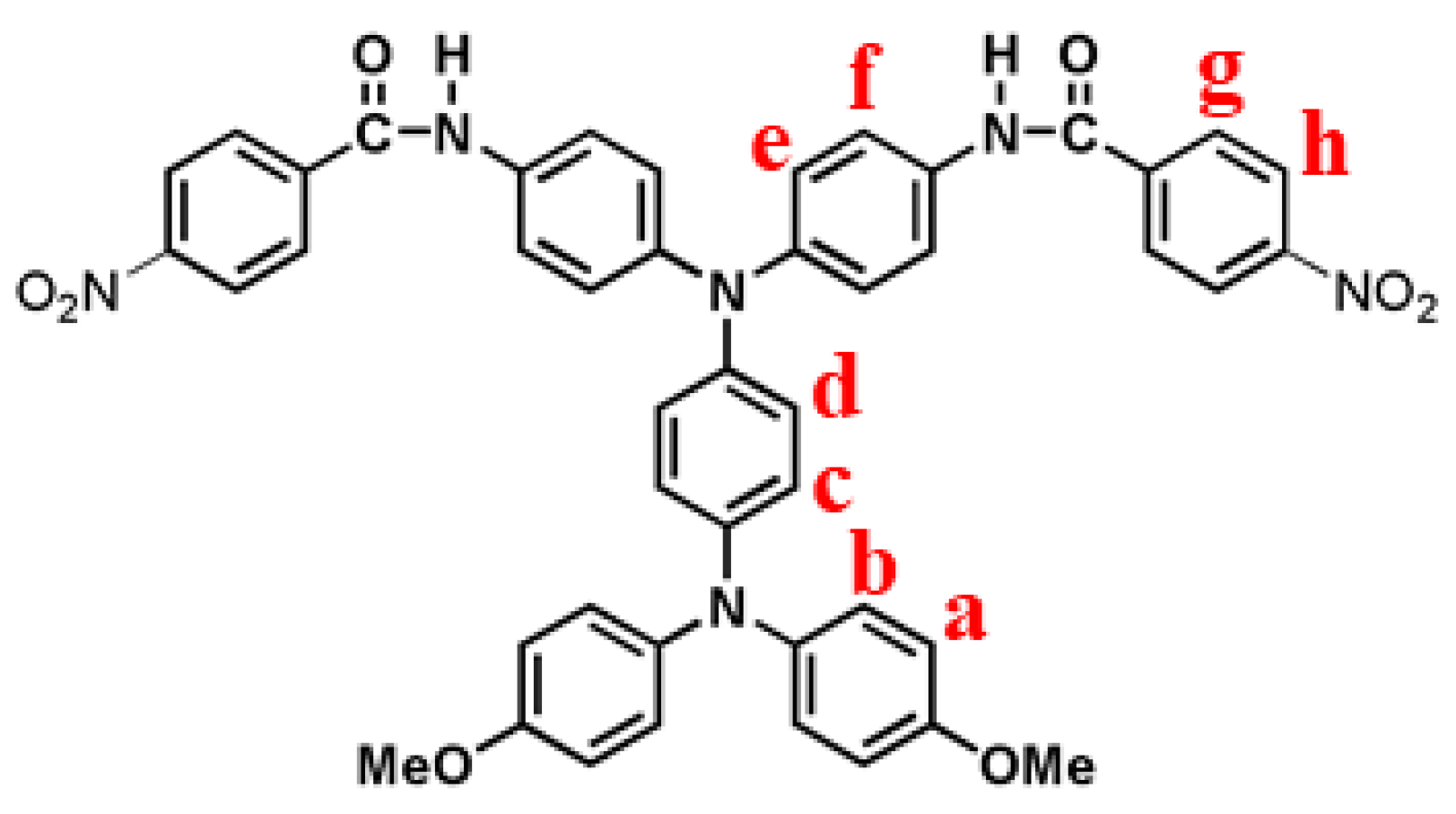

2.3. Synthesis of N,N-Bis(4-(4-Nitrobenzamido)Phenyl)-N’,N’-Bis(4-Methoxyphenyl)- 1,4-Phenylenediamine (p-5)

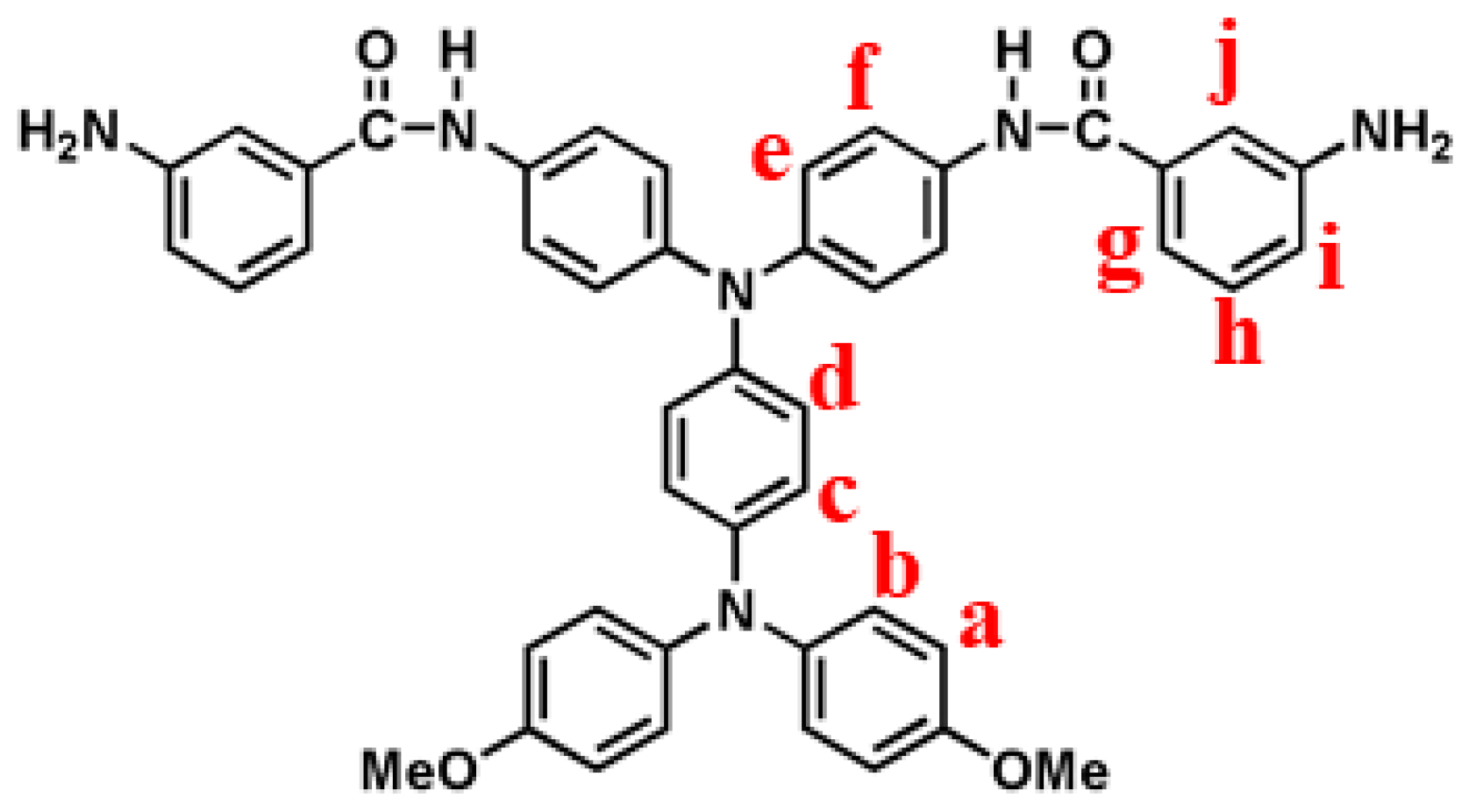

2.4. Synthesis of N,N-Bis(4-(3-Aminobenzamido)Phenyl)-N’,N’-Bis(4-Methoxyphenyl)- 1,4-Phenylenediamine (m-6)

2.5. Synthesis of N,N-Bis(4-(4-Aminobenzamido)Phenyl)-N’,N’-Bis(4-Methoxyphenyl)- 1,4-Phenylenediamine (p-6)

2.6. Synthesis of Poly(Amide-Imide)s

2.7. Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

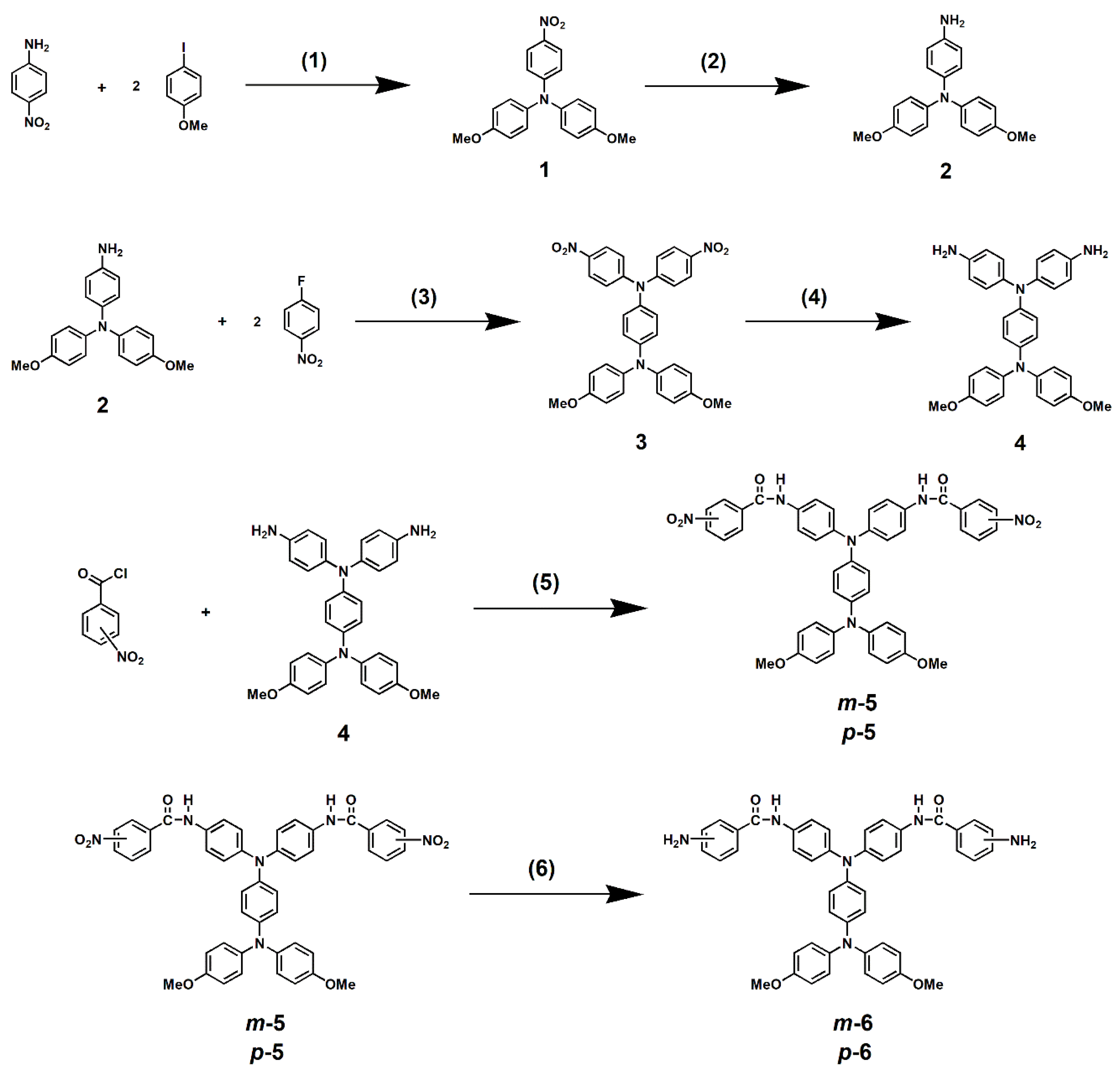

3.1. Monomer Synthesis

3.2. Synthesis of Model Compounds

3.3. Polymer Synthesis

3.4. Solubility and Thermal Properties of the PAIs

3.5. Electrochemical Properties

3.6. Spectroelectrochemical and Electrochromic Properties

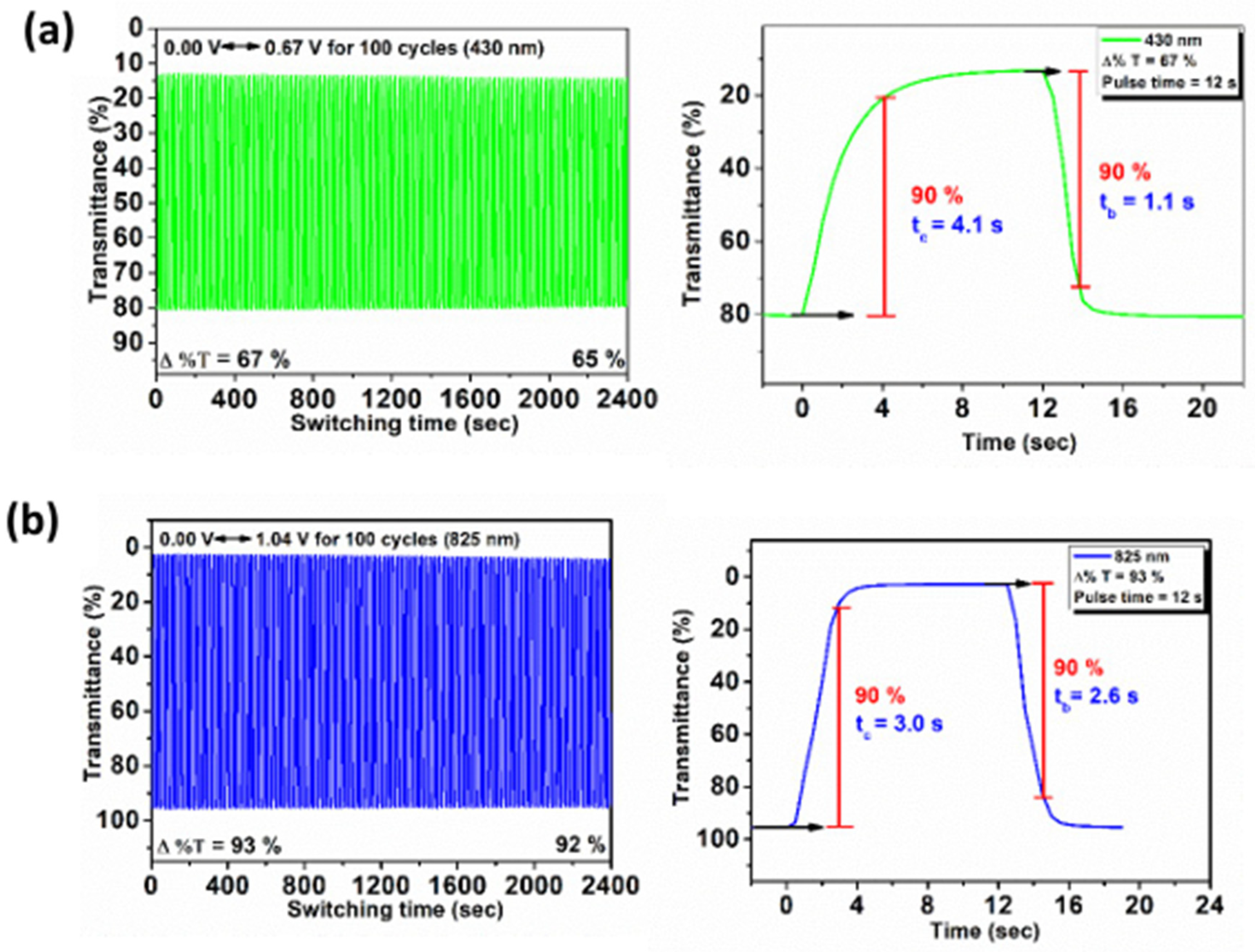

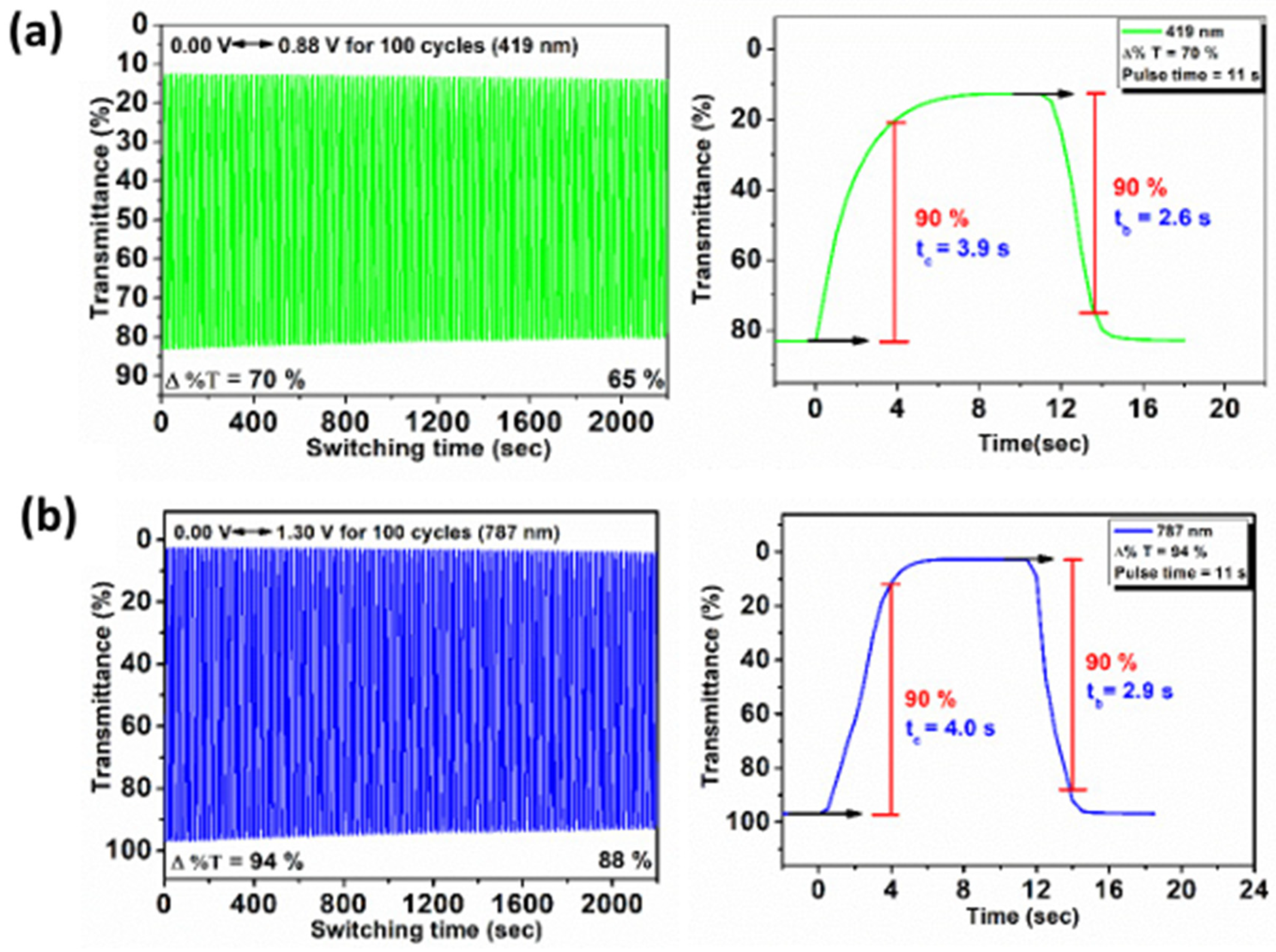

3.7. Electrochromic Switching Stability

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monk, P.M.S.; Mortimer, R.J.; Rosseinsky, D.R. Electrochromism and Electrochromic Devices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.H.; Chua, M.H.; He, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Wang, X.Z.; Meng, H.; Xu, J.W.; Huang, W. Multifunctional Electrochromic Materials and Devices Recent Advances and Future Potential. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 503, 157820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Lv, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Sui, Q.; Wang, J.; Zeng, Z.; Cai, G. Electrochromic Smart Windows with on-Demand Photothermal Regulation for Energy-Saving Buildings. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2502706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Cao, S.; Liu, Y.; Qin, S.; Li, H.; Yang, T.; Zhao, J.; Zou, B. A Multi-Color Four-Mode Electrochromic Window for All-Season Thermal Regulation in Buildings. Adv. Energy Mater. 2025, 15, 2403414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Jia, A.B.; Zhang, Y.M.; Zhang, S.X.A. Emerging Electrochromic Materials and Devices for Future Displays. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 14679–14721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Österholm, A.M.; Shen, D.E.; Kerszulis, J.A.; Bulloch, R.H.; Kuepfert, M.; Dyer, A.L.; Reynolds, J.R. Four Shades of Brown: Tuning of Electrochromic Polymer Blends Toward High-Contrast Eyewear. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wei, W.; Hou, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, K.; Wang, H. Wearable Electrochromic Materials and Devices: From Visible to Infrared Modulation. J. Mater. Chem. C 2023, 11, 7183–7210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, W. Recent Advances in Electrochromic Materials and Devices for Camouflage Applications. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 2337–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Zhu, X.; Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Xi, F.; Kang, T.; Ma, W.; Lee, C.S. Multivalent-Ion Electrochromic Energy Saving and Storage Devices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2308989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Deng, J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yan, D.; Yao, G.; Hu, L.; Sun, S.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y. Advanced Dual-Band Smart Windows: Inorganic All-Solid-State Electrochromic Devices for Selective Visible and Near-Infrared Modulation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2413659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bera, M.K.; Sarmah, S.; Santra, D.C.; Higuchi, M. Heterometallic Supramolecular Polymers: From Synthesis to Properties and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 501, 215573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, M.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, D.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J. Viologen-Based Electrochromic Devices: A Review of Structural and Functional Modification. Dyes Pigments 2026, 244, 113063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaujuge, P.M.; Reynolds, J.R. Color Control in π-Conjugated Organic Polymers for Use in Electrochromic Devices. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 268–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neo, W.; Ye, Q.; Chua, S.J.; Xu, J. Conjugated Polymer-Based Electrochromics: Materials, Device Fabrication and Application Prospects. J. Mater. Chem. C 2016, 4, 7364–7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, W.; Ouyang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wright, D.S.; Zhang, C. Polymeric Electrochromic Materials with Donor-Acceptor Structures. J. Mater. Chem. C 2017, 5, 12–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, V.; Singh, R.S.; Blackwood, D.J.; Zhili, D. A Review on Recent Advances in Electrochromic Devices: A Material Approach. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 2000082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelakkat, M. Star-Shaped, Dendrimeric and Polymeric Triarylamines as Photoconductors and Hole Transport Materials for Electro-Optical Applications. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2002, 287, 442–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Chen, J. Arylamine Organic Dyes for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 3453–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.H.; Hsiao, S.H.; Su, T.H.; Liou, G.S. Novel Aromatic Poly(amine-imide)s Bearing a Pendent Triphenylamine Group: Synthesis, Thermal, Photophysical, Electrochemical, and Electrochromic Characteristics. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Liou, G.S.; Hsiao, S.H. Highly Stable Anodic Green Electrochromic Aromatic Polyamides: Synthesis and Electrochromic Properties. J. Mater. Chem. 2007, 17, 1007–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.J.; Liou, G.S. Solution-Processable Triarylamine-Based Electroactive High Performance Polymers for Anodically Electrochromic Applications. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.J.; Liou, G.S. Recent Advances in Triphenylamine-Based Electrochromic Derivatives and Polymers. Polym. Chem. 2018, 9, 3001–3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.J.; Liou, G.S. Design and Preparation of Tiphenylamine-Based Polymeric Materials towards Emergent Optoelectronic Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2019, 89, 250–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xing, Z.; Jia, S.; Shi, X.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, Z. Research Progress in Special Engineering Plastic-Based Electrochromic Polymers. Materials 2024, 17, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuyko, I.A.; Troshin, P.A.; Ponomarenko, S.A.; Luponosov, Y.N. Polymers Based on Triphenylamine: Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2025, 94, RCR5152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, S.; He, Y.; Meng, H. Triarylamine-Based Electrochromic Materials: From Design to Multifunctional Devices. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 526, 171341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, M.B.; Day, P. Mixed Valence Chemistry—A Survey and Classification. Adv. Inorg. Chem. Radiochem. 1967, 10, 247–422. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, C.; Nöll, G. The Class II/III Transition in Triarylamine Redox Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 8434–8442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, C.; Nöll, G. Intervalence Charge-Transfer Bands in Triphenylamine-Based Polymers. Synth. Met. 2003, 139, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeghalmi, A.V.; Erdmann, M.; Engel, V.; Schmitt, M.; Amthor, S.; Kriegisch, V.; Popp, L. How Delocalized is N,N,N’,N’-tetraphenylphenylenediamine Radical Cation? An Experimental and Theoretical Study on the Electronic and Molecular Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 7834–7845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, G.S.; Chang, C.W. Highly Stable Anodic Electrochromic Aromatic Polyamides Containing N,N,N’,N’-Tetraphenyl-p-phenylenediamine Moieties: Synthesis, Electrochemical, and Electrochromic Properties. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 1667–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Liou, G.S. Novel Anodic Electrochromic Aromatic Polyamides with Multi-Stage Oxidative Coloring Based on N,N,N’,N’-tetraphenyl-p-phenylenediamine Derivatives. J. Mater. Chem. 2008, 18, 5638–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Chung, C.H.; Liou, G.S. Novel Anodic Polyelectrochromic Aromatic Polyamides Containing Pendent Dimethyltriphenylamine Moieties. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 8441–8451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, H.J.; Liou, G.S. Solution-Processable Novel Near-Infrared Electrochromic Aromatic Polyamides Based on Electroactive Tetraphenyl-p-phenylenediamine Moieties. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 4062–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.H.; Liou, G.S.; Wang, H.M. Highly Stable Electrochromic Polyamides Based on N,N-Bis(4-aminophenyl)-N’,N’-bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)-1,4-phenylenediamine. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 2330–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, X.; Zhong, X.; Ming, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J. Electrochromic Conjugated Porous Polymers based on N,N,N’,N’-tetraphenyl-1,4-phenylenediamine with Donor-Donor and Donor-Acceptor Structures. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 230, 113894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, Y.T.; Yen, C.C.; Wang, J.M.; Lu, I.S.; Huang, B.W.; Hsiao, S.H. Redox-Stable and Multicolor Electrochromic Polyamides with Four Triarylamine Cores in the Repeating Unit. Polymers 2024, 16, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, Y.T.; Lin, Y.Q.; Han, J.R.; Chiu, Y.C. Achieving Ultrahigh Electrochromic Stability of Triarylamine-Based Polymers by the Design of Five Electroactive Nitrogen Centers. Mater. Today Chem. 2024, 40, 102236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, Y.T.; Zeng, S.-J.; Lu, I.S.; Huang, B.W.; Hsiao, S.H. Advancing Electrochromic Stability in Polyamides through the Concept of Multiple Electroactive Centers. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 236, 114123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.C.; Hsiao, S.H. Electrochemical and Electrochromic Properties of Aromatic Polyamides and Polyimides with Phenothiazine-Based Multiple Triphenylamine Cores. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 16098–16108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.C.; Hsiao, S.H. Visible and Near-Infrared Electrochromic Polyamides and Polyimides Featuring a Phenothiazine-Triphenylamine Star-Shaped Architecture. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 12367–12377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, Y.T.; Chen, Y.Z.; Lin, P.L.; Hsiao, S.H. Multicolored and Near-Infrared Electrochromic Polyimide and Polyamide Functionalized with Triphenylamine Star-Shaped Architecture. Appl. Mater. Today 2025, 47, 102941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zou, X.; Tan, Y.; Jia, C.; Weng, X.; Deng, L. Infrared Electrochromic Materials, Devices and Applications. Appl. Mater. Today 2021, 24, 101073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.H.; Chang, Y.M.; Chen, H.W.; Liou, G.S. Novel Aromatic Polyamides and Polyimides Functionalized with 4-tert-Butyltriphenylamine Groups. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2006, 44, 4579–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.H.; Liou, G.S.; Kung, Y.C.; Pan, H.Y.; Kuo, C.H. Electroactive Aromatic Polyamides and Polyimides with Adamantylphenoxy-Substituted Triphenylamine Units. Eur. Polym. J. 2009, 45, 2234–2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.H.; Wang, H.M.; Chang, P.C.; Kung, Y.R.; Lee, T.M. Synthesis and Electrochromic Properties of Aromatic Polyetherimides Based on a Triphenylamine-Dietheramine Monomer. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2013, 51, 2925–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, S.H.; Ni, Z.D. Synthesis and Electrochromic Properties of Triphenylamine-Based Aromatic Poly(Amide-Imide)s. Polymers 2025, 17, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, Z.D.; Hsiao, S.H. Substituent Effects on the Electrochemical and Electrochromic Properties of Triphenylamine-Based Poly(Amide–Imide)s. ChemistrySelect 2025, 10, e03352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymer Code | ηinh a (dL/g) | Solvents b,c | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMP | DMAc | DMF | DMSO | m-Cresol | THF | ||

| m-8a | 0.35 | ++ | ++ | +h | ++ | +− | − |

| m-8b | 0.44 | +h | +h | +− | +h | +− | − |

| m-8c | 0.31 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +h | − |

| m-8d | 0.36 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +h | +− |

| m-8e | 0.85 | ++ | ++ | +h | ++ | +h | − |

| p-8b | 0.46 | +h | +h | +− | +h | +− | − |

| p-8c | 0.33 | ++ | ++ | +h | ++ | +− | +− |

| p-8d | 0.42 | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | +h | +− |

| p-8e | 0.71 | +h | +h | +− | +h | +− | − |

| PI-8c′ | 0.42 | ++ | ++ | +− | +− | − | − |

| Polymer Code | Tg (°C) a | Td at 5% Weight Loss (°C) b | Td at 10% Weight Loss (°C) b | Char Yield (wt %) c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N2 | Air | N2 | Air | |||

| m-8a | 268 | 445 | 417 | 469 | 469 | 58 |

| m-8b | 277 | 464 | 458 | 489 | 494 | 55 |

| m-8c | 250 | 457 | 457 | 483 | 499 | 48 |

| m-8d | 267 | 468 | 428 | 493 | 485 | 54 |

| m-8e | 265 | 435 | 421 | 461 | 460 | 52 |

| p-8b | 292 | 468 | 465 | 494 | 501 | 59 |

| p-8c | 252 | 455 | 461 | 477 | 489 | 56 |

| p-8d | 278 | 470 | 465 | 498 | 501 | 54 |

| p-8e | 275 | 439 | 437 | 465 | 472 | 55 |

| PI-8c′ | 244 | 457 | 473 | 481 | 525 | 48 |

| Polymer Code | Thin film Absorption Wavelength (nm) | Oxidation Potential (V) a | Egopt (eV) b | HOMO (eV) c | LUMO (eV) d | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| λmax | λonset | Eonset | E1/2Ox1 | E1/2Ox2 | ||||

| m-8a | 314 | 424 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.87 | 2.92 | −4.83 | −1.91 |

| m-8b | 338 | 422 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.86 | 2.94 | −4.83 | −1.89 |

| m-8c | 312 | 422 | 0.33 | 0.47 | 0.84 | 2.94 | −4.83 | −1.89 |

| m-8d | 304 | 419 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.85 | 2.96 | −4.83 | −1.87 |

| m-8e | 308 | 422 | 0.34 | 0.46 | 0.85 | 2.94 | −4.82 | −1.88 |

| p-8b | 311 | 422 | 0.35 | 0.50 | 0.88 | 2.94 | −4.86 | −1.92 |

| p-8c | 308 | 425 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0.87 | 2.92 | −4.89 | −1.97 |

| p-8d | 304 | 424 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.88 | 2.92 | −4.85 | −1.93 |

| p-8e | 304 | 420 | 0.37 | 0.52 | 0.89 | 2.95 | −4.88 | −1.93 |

| PI-8c′ | 326 | 402 | 0.46 | 0.62 | 0.95 | 3.09 | −4.98 | −1.89 |

| Polymer | λmax a (nm) | 1st Cycle Δ%T | 100th Cycle Δ%T | Response Time b | ΔOD c | Qd d (mC/cm2) | CE e (cm2/C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tc (s) | tb (s) | |||||||

| m-8a | 430 | 43 | 42 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 1.39 | 7.88 | 176 |

| 825 | 82 | 81 | 4.0 | 5.7 | 2.31 | 10.78 | 214 | |

| m-8b | 429 | 61 | 60 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 0.86 | 5.03 | 171 |

| 824 | 99 | 96 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 2.57 | 10.70 | 240 | |

| m-8c | 430 | 67 | 65 | 4.1 | 1.1 | 0.78 | 3.40 | 229 |

| 825 | 93 | 92 | 3.0 | 2.6 | 1.57 | 6.52 | 241 | |

| m-8d | 429 | 44 | 43 | 2.6 | 1.5 | 0.31 | 3.42 | 91 |

| 820 | 93 | 85 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 1.33 | 9.09 | 146 | |

| m-8e | 429 | 47 | 44 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 0.69 | 4.26 | 162 |

| 824 | 98 | 97 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 1.95 | 9.74 | 200 | |

| p-8b | 430 | 49 | 48 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 0.73 | 4.52 | 162 |

| 830 | 96 | 91 | 3.7 | 2.8 | 1.55 | 10.4 | 149 | |

| p-8c | 429 | 48 | 47 | 4.6 | 4.7 | 0.38 | 1.87 | 203 |

| 832 | 77 | 76 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 0.83 | 4.47 | 186 | |

| p-8d | 430 | 46 | 44 | 3.6 | 2.0 | 0.34 | 3.64 | 94 |

| 828 | 75 | 59 | 3.8 | 2.1 | 0.64 | 9.88 | 65 | |

| p-8e | 429 | 36 | 35 | 3.8 | 1.6 | 0.24 | 2.57 | 94 |

| 831 | 75 | 60 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 0.62 | 9.22 | 67 | |

| PI-8c′ | 419 | 70 | 65 | 3.9 | 2.6 | 0.81 | 4.46 | 182 |

| 787 | 94 | 88 | 4.0 | 2.9 | 1.62 | 8.38 | 193 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Huang, B.-W.; Hsiao, S.-H. Dual-Band Electrochromic Poly(Amide-Imide)s with Redox-Stable N,N,N’,N’-Tetraphenyl-1,4-Phenylenediamine Segments. Polymers 2026, 18, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010139

Huang B-W, Hsiao S-H. Dual-Band Electrochromic Poly(Amide-Imide)s with Redox-Stable N,N,N’,N’-Tetraphenyl-1,4-Phenylenediamine Segments. Polymers. 2026; 18(1):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010139

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Bo-Wei, and Sheng-Huei Hsiao. 2026. "Dual-Band Electrochromic Poly(Amide-Imide)s with Redox-Stable N,N,N’,N’-Tetraphenyl-1,4-Phenylenediamine Segments" Polymers 18, no. 1: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010139

APA StyleHuang, B.-W., & Hsiao, S.-H. (2026). Dual-Band Electrochromic Poly(Amide-Imide)s with Redox-Stable N,N,N’,N’-Tetraphenyl-1,4-Phenylenediamine Segments. Polymers, 18(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym18010139