1. Introduction

The development of micro- and nanofabrication techniques has received interest in terms of the mechanical properties of photocurable polymers, such as SU-8, which can be used in the case of silicon micromachining [

1,

2,

3]. These photoresist layers play a critical role in defining the structures of microelectromechanical systems (MEMS), biomedical microdevices, or integrated microsystems [

4]. SU-8 is a negative-tone, epoxy-based photoresist commonly used in MEMS and bioMEMS devices. It is usually applied as a thin film on silicon or glass wafer substrates and then exposed to ultraviolet light through a mask, creating precise patterns [

4,

5]. After curing, these systems show excellent chemical stability, mechanical strength, and ability to form thick, high-aspect-ratio structures [

6,

7,

8]. Its versatility allows it to be used in applications such as sensors, microfluidics, or optical devices. The mechanical integrity of SU-8 layers is crucial for device performance and long-term reliability, particularly when they serve as structural or encapsulating components exposed to mechanical or thermal loading. Understanding their mechanical properties during manufacturing phases can also be beneficial in optimizing the fabrication process, enhancing the reliability of electronic devices.

The raw SU-8 material contains an epoxy-based monomer (Bisphenol A Novolac) and photocatalytic initiator (Triarylsulfonium/hexafluoroantimonate salt) dissolved in an organic solvent (gamma-butyrolactone or cyclopentanone) [

9]. Due to UV exposure, the generated photoacid (hexafluoroantimonic) promotes the thermally activated reactions of the epoxy monomers through their neutral epoxy groups to form a cross-linked polymer network [

5]. By varying the curing parameters (UV dose and exposure time, baking temperature, and cycle times), the mechanical properties of the film can be controlled. To optimize the thermal process of the SU-8 layer, a typical baking program consists of multiple steps using room temperature cycles—65 –95 °C—in both pre-bake (or soft bake) and post-bake (post-exposure bake—PEB) cases. The completely cross-linked resist is characterized by excellent mechanical properties, although to improve its hardness, a further hard-bake process can be considered [

10].

The polymer network of SU-8 evolves through solvent evaporation and cross-linking during the sequential UV exposure and baking steps of lithographic processes, and its mechanical response is highly dependent on the degree of curing and the resulting cross-link density. The lifespan of the final SU-80based products is significantly affected by the hardness, stiffness, or viscoelastic behaviour of the material [

11].

The fabrication of SU-8 structures on the silicon wafers involves several thermal treatments, namely pre-bake (often called soft bake), post-bake (or post-exposure bake implemented after lithography, the UV exposure in this context), and hard bake [

10,

12]. These baking steps affect mechanical and chemical properties due to the induced changes in the polymer structure and the density of the cross-linking. The pre-bake step is described to primarily remove solvents and enhance adhesion to the substrate. This phase significantly affects the mechanical stability of the resist. The post-bake step initiates extensive cross-linking reactions and can greatly impact the hardness of the surface layer. The last baking phase, hard bake, is usually an optional step and is used to stabilize the SU-8 polymer further to remove residual mechanical stresses, improving long-term stability [

13,

14]. Most previous investigations examined either static mechanical properties or high-temperature viscoelasticity, while few studies have correlated the evolution of viscoelastic parameters with the specific baking stages used in microfabrication.

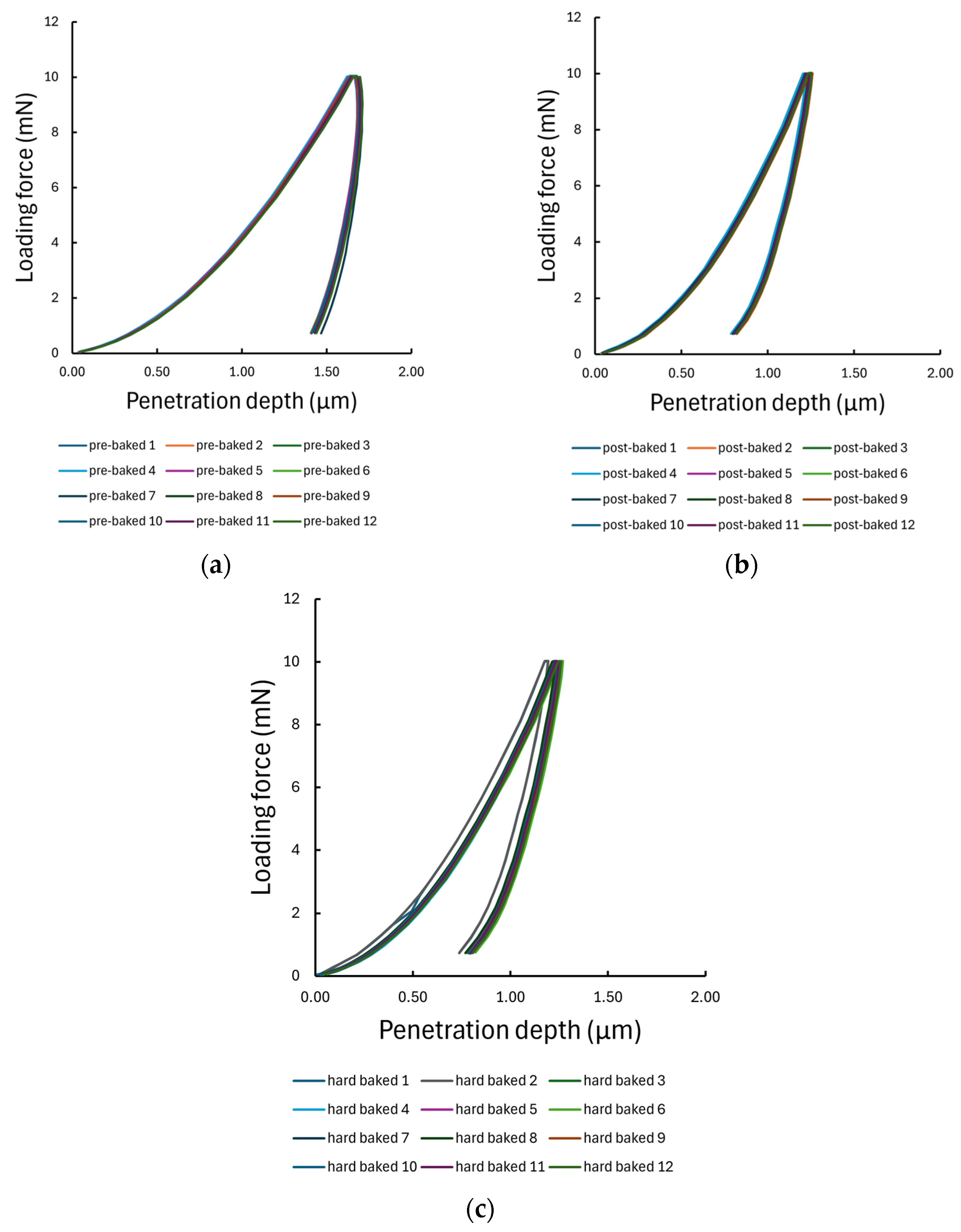

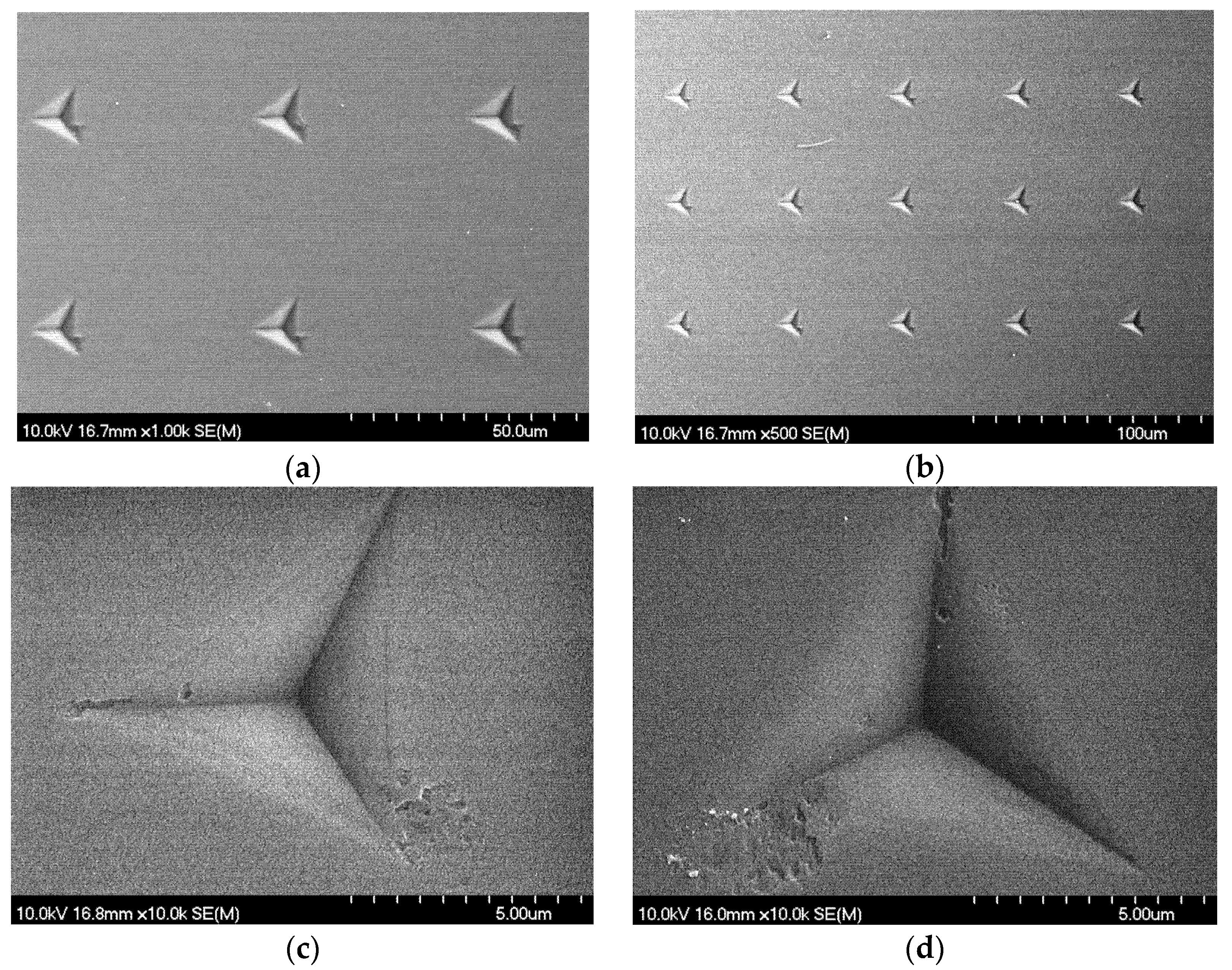

A modern approach to testing the mechanical properties is the nanoindentation method. Nanoindentation is described as a sensitive non-destructive method and can be used to characterize properties of thin films and nanostructured or even bulk materials [

11,

15]. It can give a reproducible, detailed picture of the hardness, elastic modulus, creep, or dynamic behaviour of samples at a high spatial resolution. To test silicon wafers or MEMS properties, such high-precision devices are well-suited. The nanoindenter tools, in general, apply a load through a sharp indenter tip, and the force and displacement are measured continuously. The obtained load–displacement curves can be analysed to investigate the hardness or modulus of elasticity of the material through the Oliver–Pharr method [

15].

Beyond conventional microfabrication polymers, recent studies on polymer-based thin films have highlighted that mechanical integrity, stress transfer efficiency, and stiffness evolution critically govern device reliability and functional stability in advanced flexible and microstructured systems [

16,

17]. In such materials, quantification of elastic parameters and time-dependent mechanical properties is essential for understanding structure–property relationships for optimizing processing conditions [

18].

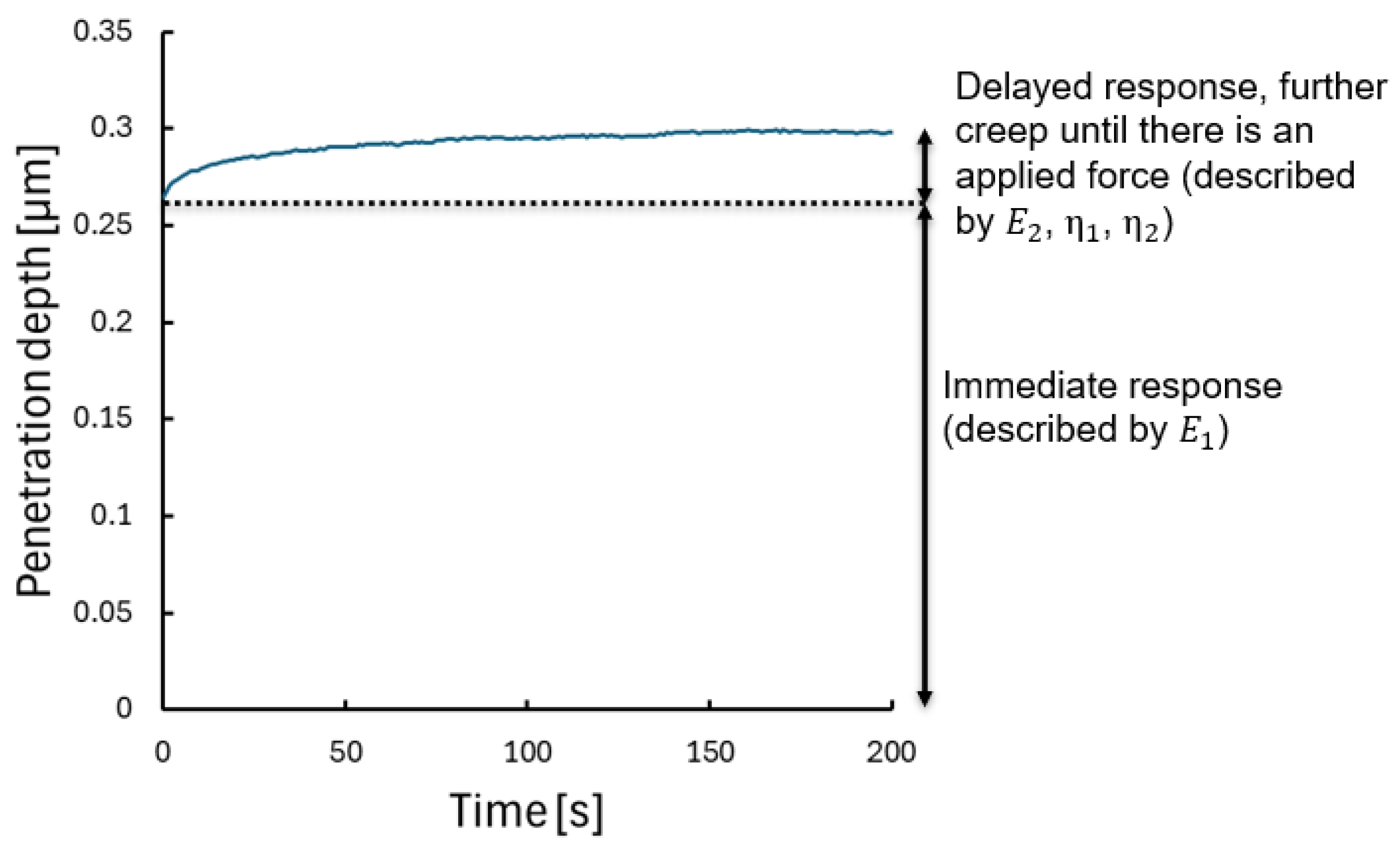

The present study aims to fill this gap by providing a systematic nanoindentation-based assessment of both the instantaneous and time-dependent mechanical behaviour of SU-8 coatings on silicon wafer under different baking conditions that are directly relevant to lithographic fabrication. Static indentation data were complemented by creep experiments analysed using the Burgers viscoelastic model to quantify the changes in the elastic moduli and viscosity parameters associated with progressive cross-linking. By comparing these results with established literature data, we elucidate how processing temperature governs the transition from viscous to viscoelastic–elastic behaviour and propose nanoindentation as a rapid, nondestructive tool for monitoring polymerization and mechanical stability in SU-8-based microfabrication.

4. Discussion

The nanoindentation experiments revealed significant changes in the hardness of the SU-8-coated silicon wafer samples associated with the baking phase, indicating progressive polymer cross-linking and solvent evaporation throughout the thermal processing steps. The measurements showed that the SU-8 coating exhibits a relatively high elastic modulus and hardness after the post-baking and hard-baking phases, confirming its suitability as a mechanically robust polymer layer for microfabricated structures. The values obtained by the Oliver–Pharr method showed good consistency across measurement points, indicating uniform coating quality. Post-bake and hard-bake measurements showed a statistically significant increase in the mean hardness values compared to the pre-baked phase, while the modulus of elasticity, describing the stiffness of the layer, did not change during static measurements. Creep experiments demonstrated a distinct time-dependent deformation component, which was well described by the Burgers viscoelastic model. The extracted parameters (, , , and ) reflected the combined elastic and viscous behaviour of the SU-8 layer, with the instantaneous modulus dominating the short-term response and the retarded modulus governing long-term deformation. The measured creep depth values correlated with the viscous terms, supporting the validity of the model for polymeric coatings. The instantaneous modulus showed a significant increase after the post-bake and hard-bake phases compared to the pre-bake phase, similarly to the hardness results. However, the , , and time-dependant parameters showed a significant difference between all baking phases, describing different behaviours after these manufacturing processes. Overall, the results highlight the dual nature of SU-8 as a stiff yet viscoelastic material, emphasizing the importance of both elastic and time-dependent characterization in its mechanical assessment. The suitability of the Burgers model for this analysis is further supported by its ability to distinguish between instantaneous elasticity, retarded viscoelastic recovery, and long-term viscous flow, which evolve differently across the lithographic baking stages and cannot be resolved using simpler viscoelastic representations.

The static nanoindentation results obtained in this study are consistent with the literature values for SU-8 films fabricated on silicon substrates. Hwang et al. [

21] reported modulus of elasticity values between 1.8 and 3.5 GPa from microbeam bending tests, emphasizing the influence of interfacial defects on apparent stiffness. In their study, they fabricated SU-8 layers as microcantilever beams on both polished and unpolished wafer surfaces, and the modulus increased with an increasing beam width, improving the surface’s quality. Their results highlighted the sensitivity of the measured modulus to fabrication-related defects and interfacial integrity, which is comparable to the slight variability observed in our static indentation data between differently baked samples. Our higher mean modulus of ~6 GPa agrees with later indentation-based studies, which are less affected by interfacial compliance and probe the near-surface region of fully cured films. Similar magnitudes of modulus values were reported by Krishna et al. [

22], who obtained 6.5 ± 0.05 GPa for the modulus and 455 MPa for hardness using quasi-static indentation without significant size or rate effects, confirming that this range represents the intrinsic stiffness of cross-linked SU-8. Their study demonstrated that the modulus does not depend on the loading rate and holding time. Nanoindentation measurements predominantly sense the near-surface, fully polymerized region of the coating and reflect the higher degree of cross-linking achieved under current thermal processing parameters.

When nanoindentation is performed on thin films supported by stiff substrates, the contribution of the substrate to the measured mechanical response must be carefully considered. It is well established that substrate effects become significant when the indentation penetration depth exceeds approximately 10% of the film thickness, potentially leading to an overestimation of both elastic modulus and hardness for compliant coatings on rigid substrates [

20,

23]. In our case, the SU-8 film’s thickness was 22–25 μm, while the maximum indentation depth at the applied peak load of 10 mN was approximately 1.3 μm. This corresponds to a penetration depth-to-thickness ratio of about 5–6%, which is well below the commonly accepted threshold for the onset of significant substrate influence. The mechanical response measured under these conditions can be considered to predominantly reflect the intrinsic near-surface properties of the SU-8 coating rather than the underlying silicon wafer. This is also supported by the experimental observation that the measured elastic modulus values (~6 GPa) are in close agreement with the previously reported nanoindentation-based measurements of fully cured SU-8 films [

22] while remaining orders of magnitude lower than the elastic modulus of the silicon substrate. Taken together, these considerations indicate that substrate effects are negligible under the applied experimental conditions, and the reported elastic, plastic, and viscoelastic parameters represent a valid approximation of the intrinsic mechanical behaviour of the SU-8 coating in the near-surface region.

The influence of processing and structural anisotropy on the mechanical performance of SU-8 has been highlighted in recent microtensile studies. Robin et al. [

24] examined 2 μm thick spin-coated SU-8 2002 films using in situ optical tensile experiments combined with digital image correlation to quantify full-field strain distributions. They reported mean modulus values of 3.48 ± 0.57 GPa for hard-baked and 2.92 ± 0.43 GPa for non-hard-baked films, accompanied by a ≈20% increase in modulus and strength after hard baking due to enhanced cross-linking, as confirmed by FTIR. Furthermore, the authors demonstrated that spin-coating induces in-plane anisotropy through radial shear flow, leading to direction-dependent tensile moduli and strength. Their analysis indicated that modulus values obtained from nanoindentation tests are typically 1.5–2× higher than those from tensile loading because of out-of-plane anisotropy and substrate constraint. These findings agree with our observation that the localized indentation of fully cross-linked near-surface regions yields higher apparent moduli (~6 GPa), whereas in-plane mechanical measurements or bulk bending tests yield lower values. Micromechanical investigations by Cherukuri et al. [

25] were used to conduct in situ SEM micropillar compression and Berkovich nanoindentation experiments on photolithographically patterned SU-8 films across seven orders of magnitude in strain rate (10

−3–10

3 s

−1), which also agrees with our quasi-static results. They reported that the elastic modulus remains nearly constant at ~4–5 GPa irrespective of the strain rate, while hardness and yield stress increase modestly. Their findings confirm that SU-8 behaves as a rate-insensitive elastic solid but exhibits thermally activated plasticity at high deformation rates. This reinforces that the primary differences between reported values arise from process-dependent cross-linking density and measurement depth rather than from viscoelastic rate effects. Our post- and hard-baked samples show slightly higher moduli (~6 GPa), which is consistent with a denser polymer network produced by extended thermal curing.

Temperature-controlled indentation by Chang et al. [

26] showed a moderate softening between 25 °C and 45 °C of the SU-8 using a Berkovich indenter integrated with an AFM-based nanoindenter system. They found a clear thermal softening trend, where the modulus decreased from approximately 14 GPa at 25 °C to 11 GPa at 45 °C under a 1 mN load, while hardness dropped from 0.43 GPa to 0.26 GPa. The authors attributed this decline to the temperature-induced mobility of the epoxy network, reducing effective cross-link density. In addition, they observed that apparent modulus and hardness increase with indentation load, an effect primarily caused by the stiffer silicon substrate contribution. These findings underline the pronounced temperature sensitivity of SU-8 and emphasize that the near-surface mechanical response depends not only on baking parameters but also on the thermal environment during testing and operation. In the present study, all measurements were performed at room temperature under quasi-static loading; thus, the reported moduli around 6 GPa reflect the intrinsic stiffness of the SU-8 coating in the fully cured state, without significant substrate or temperature-related deviations.

The time- and temperature-dependent deformation behaviour obtained from creep measurements agrees with previous viscoelastic characterizations of SU-8. Pustan et al. [

27] systematically investigated the evolution of the elastic modulus of SU-8, along with hardness, adhesion, and friction, using AFM-based nanoindentation and spectroscopy at operating temperatures between 20 °C and 100 °C for samples hard-baked at 125–215 °C. Their results revealed a marked softening with increasing temperature: The elastic modulus decreased by 47–53%, and hardness decreased by 46–70%, whereas adhesion and friction forces increased by up to 40% and 80%, respectively. These changes were attributed to thermal relaxation and enhanced chain mobility in the polymer network, consistent with the onset of viscoelastic flow well below the glass-transition temperature (

~ 210 °C). The viscoelastic nature of SU-8 has also been studied by Chung and Park [

28], who combined tensile and dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) to study its temperature- and frequency-dependent response between 25 °C and 200 °C. Their results revealed that the modulus decreases steadily with temperature, falling by nearly 60% as the polymer approaches its glass-transition region. DMA measurements showed characteristic peaks in the loss modulus and loss factor (tan δ) between 125 °C and 150 °C, marking the transition from glassy to rubbery behaviour. Increasing the excitation frequency (0.1–10 Hz) shifted this transition toward higher temperatures, reflecting thermally activated segmental mobility typical of cross-linked epoxies. Importantly, prolonged thermal exposure (3 h at 150 °C) led to the stabilization of the storage modulus and a right-shift of the loss factor maximum, indicating post-curing and increased cross-link density. These finding agrees with our Burgers model analysis, where the retarded modulus

and viscosity

showed significant increases after the post-bake step, suggesting a similar reduction in molecular relaxation pathways. Together, these results confirm that the time- and temperature-dependent deformation observed in SU-8 arises from a combination of thermally driven chain relaxation and curing-related stiffening, consistent with the viscoelastic behaviour of other highly cross-linked epoxy systems.

The viscoelastic interpretation of our creep data is also strongly supported by the microscale analysis of Xu et al. [

11], who combined micropillar compression and viscoelastic nanoindentation of SU-8 2025 films fabricated by UV lithography. Their study demonstrated that SU-8 exhibits measurable viscoelastic relaxation even at room temperature, with the mean modulus increasing from ~3.1 to 4.8 GPa as the strain rate rose from 10

−4 to 10

−2 s

−1. When the same material was analysed using the classical Oliver–Pharr approach, the apparent modulus was ~6 GPa, an overestimation caused by neglecting viscoelastic compliance during unloading. By applying Lu’s nanoindentation-based viscoelastic analysis, Xu et al. extracted relaxation and creep parameters that closely matched the tensile test results reported by Robin et al. [

24]. Their findings confirm that the instantaneous stiffness of SU-8 is higher than its long-term equilibrium modulus and that the measured parameters depend on the strain-rate window and load-hold protocol. This behaviour is consistent with our Burgers model analysis, in which the retarded modulus

and viscosities

capture the same time-dependent stress-relaxation effects observed by Xu et al. The studies of Schiffmann and Brill [

29] complement these results. They systematically investigated SU-8 thin films at each stage of the lithographic process using nanoindentation-based creep and stress-relaxation tests. By deriving time-dependent viscoelastic functions, they quantified how cross-linking progressively transforms SU-8 from a viscous liquid-like resist into a predominantly elastic solid. The dynamic viscosity increased by nearly fifty-fold during cross-linking, and the retardation spectra revealed a strong reduction in long relaxation times as curing advanced. Notably, the fully processed SU-8 films exhibited ~75% total elastic recovery (immediate + retarded) after three days, while pre-baked films only showed ~25%, demonstrating the transition from viscous to viscoelastic-elastic behaviour. These results are fully consistent with our Burgers model analysis, where the post-bake step caused marked increases in the retarded modulus (

) and viscosities (

and

), accompanied by a reduction in long-time creep. Collectively, these experimental and modelling observations confirm that post-bake processing increases cross-link density and suppresses viscoelastic flow, stabilizing the mechanical response of SU-8 across thermal and temporal scales. Despite this general consistency with earlier viscoelastic investigations, an important distinction must be emphasized. Previous nanoindentation-based creep and stress-relaxation studies of SU-8 primarily addressed either broad curing trends, temperature-dependent behaviour, or generic stages of polymerization without direct alignment to the discrete baking steps used in standard photolithographic processing. In contrast, the present work explicitly maps the evolution of Burgers model parameters onto the pre-bake, post-exposure-bake, and hard-bake phases applied to wafer-supported SU-8 coatings. This process-resolved approach reveals that the most pronounced changes in viscoelastic response occur during the post-bake step, where the retarded modulus and viscosity increase dramatically, while further hard-baking mainly stabilizes these parameters. Such differentiation cannot be inferred from static indentation alone and provides direct mechanistic insight into how thermal curing suppresses long-term viscoelastic deformation through increasing cross-link density.

The strong dependence of both elastic and viscoelastic properties on the thermal history of SU-8 underscores the importance of optimized curing conditions in MEMS and microfluidic applications. A sufficiently long post-bake or hard-bake step ensures stable modulus and minimized creep under mechanical or thermal loading. Because nanoindentation directly captures both the instantaneous and time-dependent responses, it provides a rapid, nondestructive means of assessing polymerization completeness and uniformity across wafers. The present results, therefore, not only clarify the mechanical evolution of SU-8 during processing but also support its use as a process-monitoring and quality-control tool for polymer-based microsystems.