In recent years, increasing scientific attention has been devoted to the development of novel biodegradable materials and the exploration of their potential applications in the biomedical field. Polymers have emerged as highly attractive candidates for biomedical use, particularly in hard tissue engineering, due to their ability to elicit a controlled and beneficial host tissue response. To address the inherent limitations associated with single polymer systems, the concepts of polymer blending and polymer composite fabrication have been introduced. By combining two or more polymers, the resulting hybrid materials can exhibit enhanced mechanical, structural, and biological properties. Such polymer-based implants are widely employed in various medical interventions, particularly in orthopedic applications such as bone and joint prostheses, as well as in other fields where lightweight, biocompatible, and degradable materials are required. The continuous advancement of social and economic systems has further stimulated extensive scientific and engineering research into polymer discovery, optimization, and practical implementation. Recent innovations also emphasize the importance of tailoring polymer degradation rates to match tissue regeneration processes, thereby improving long-term implant performance. Moreover, the integration of bioactive molecules into polymer matrices is increasingly being explored to enhance biocompatibility and therapeutic outcomes [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Polylactic acid (PLA) is one of the most studied biopolymers because it can be produced from nontoxic renewable raw materials. PLA is extensively utilized in biomedical applications owing to its intrinsic biocompatibility and controlled biodegradability. Recent investigations have examined the incorporation of nanomaterials, particularly few-layer graphene, into PLA matrices to improve their mechanical and thermal performance while preserving cytocompatibility, thereby expanding the material’s potential for advanced biomedical use [

10]. PHB is a biodegradable, biocompatible, and nontoxic aliphatic polyester, characterized by a highly regular, linear polymer chain that enables crystallization and confers favorable mechanical and thermal properties. As a microbial storage polymer synthesized primarily by various Bacillus and Ralstonia species, PHB exhibits a degradation profile compatible with physiological environments and generates nontoxic products such as 3-hydroxybutyric acid. Despite its advantageous biocompatibility and environmental sustainability, its intrinsic brittleness and narrow processing window have stimulated extensive research into copolymerization (e.g., with PHV) and blending strategies to enhance ductility, thermal stability, and suitability for biomedical applications including tissue engineering scaffolds, controlled drug delivery systems, and temporary implant materials [

11]. Starch is a naturally occurring polysaccharide-based biopolymer synthesized by plants as a primary energy reserve. It is predominantly composed of two macromolecular fractions, linear amylose and highly branched amylopectin, whose structural arrangement strongly influences its physicochemical behavior. Starch is characterized by several advantageous material properties, including low density and low production cost, as well as its inherent biodegradability and non-abrasive nature, which make it an attractive renewable resource for various industrial and environmental applications [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. The fabrication of filaments derived from biodegradable polymers introduces new perspectives in material development and represents a significant convergence of medical science and engineering disciplines. Such filaments enable the creation of specific patients’ biomedical devices through additive manufacturing, while ensuring biocompatibility and controlled degradation within physiological environments. Moreover, the integration of advanced polymer processing techniques facilitates the optimization of mechanical, thermal, and structural properties required for clinical applications. This multidisciplinary approach ultimately accelerates innovation in regenerative medicine, implant design, and personalized therapeutic solutions [

17,

18,

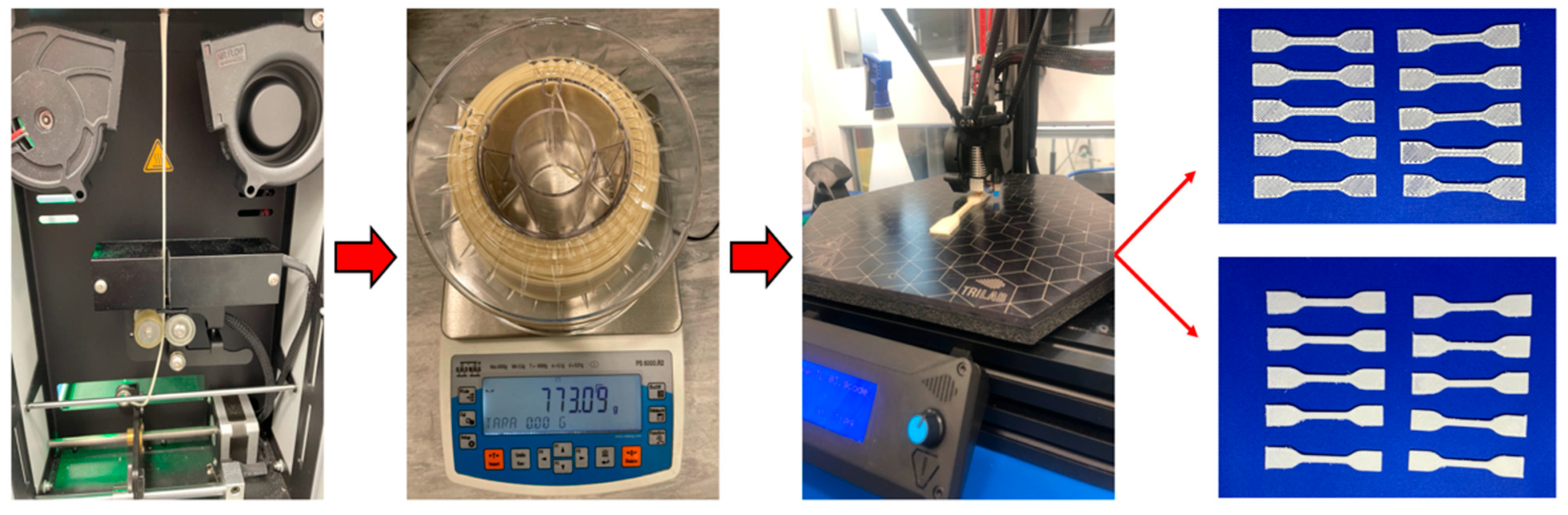

19]. Using a desktop extrusion system, we produced three filaments with the type labels 111, 145, and 146 from the above-mentioned biodegradable components. Extrusion is a manufacturing process in which thermoplastic materials are forced through a die with a defined cross-sectional profile to produce a continuous strand of molded product (filament). The extrusion process begins with the material in the form of granules, pellets, or powders being fed from a hopper into the extruder zone. Then the melting process begins by means of the heat from mechanical energy generated by the rotation of the screw and the heaters that are placed along the head. The molten materials are then forced into the die, which structures the materials during the cooling process. Large companies use industrial filament makers (extrusion systems), which are characterized by large volumes of extruded material and precision. In our research, however, we chose desktop extrusion systems at a good level because desktop extrusion systems are increasingly on par with industrial extrusion systems in quality. When filament is used in additive technologies, it is essential that it meets the requirements needed for high-quality 3D printing of implants suitable for tissue substitution. Essential filament characteristics for additive manufacturing include high mechanical strength, uniform diameter consistency, and a smooth surface finish. These properties are critical determinants of the dimensional accuracy, structural integrity, and overall quality of the final printed constructs. Notably, the Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM/FFF) technique, which underpins much of modern polymer-based 3D printing, was first patented in 1989, providing the foundation for subsequent advancements in additive manufacturing technologies [

20]. Three-dimensional printers based on FFF technology are currently the most popular three-dimensional printers. This technology is based on the extrusion of filament from a nozzle that is deposited on a heated plate, creating a two-dimensional layer on top of a second layer, resulting in a tangible three-dimensional object. FFF commonly employs filaments composed of thermoplastic polymers such as PLA, among others, with a prevalent filament diameter of 1.75 mm. PLA/PHB-based materials with plasticizer and starch are used as hard tissue substitutes, mainly because their properties can be well adapted to those of natural tissue and are biologically safe. The main reasons are biocompatibility and biodegradability, because both polymers gradually decompose into natural metabolites (lactic acid, 3-hydroxybutanoic acid), which is advantageous when the material is intended to replace newly formed bone mass. The PLA/PHB + starch and plasticizer composite allows the formation of a porous structure similar to trabecular bone. This supports the ingrowth of bone cells, the exchange of nutrients, and the formation of new bone mass [

21,

22]. These material characteristics facilitate the manufacture of functional implants via FFF, while maintaining biocompatibility and controlled resorption [

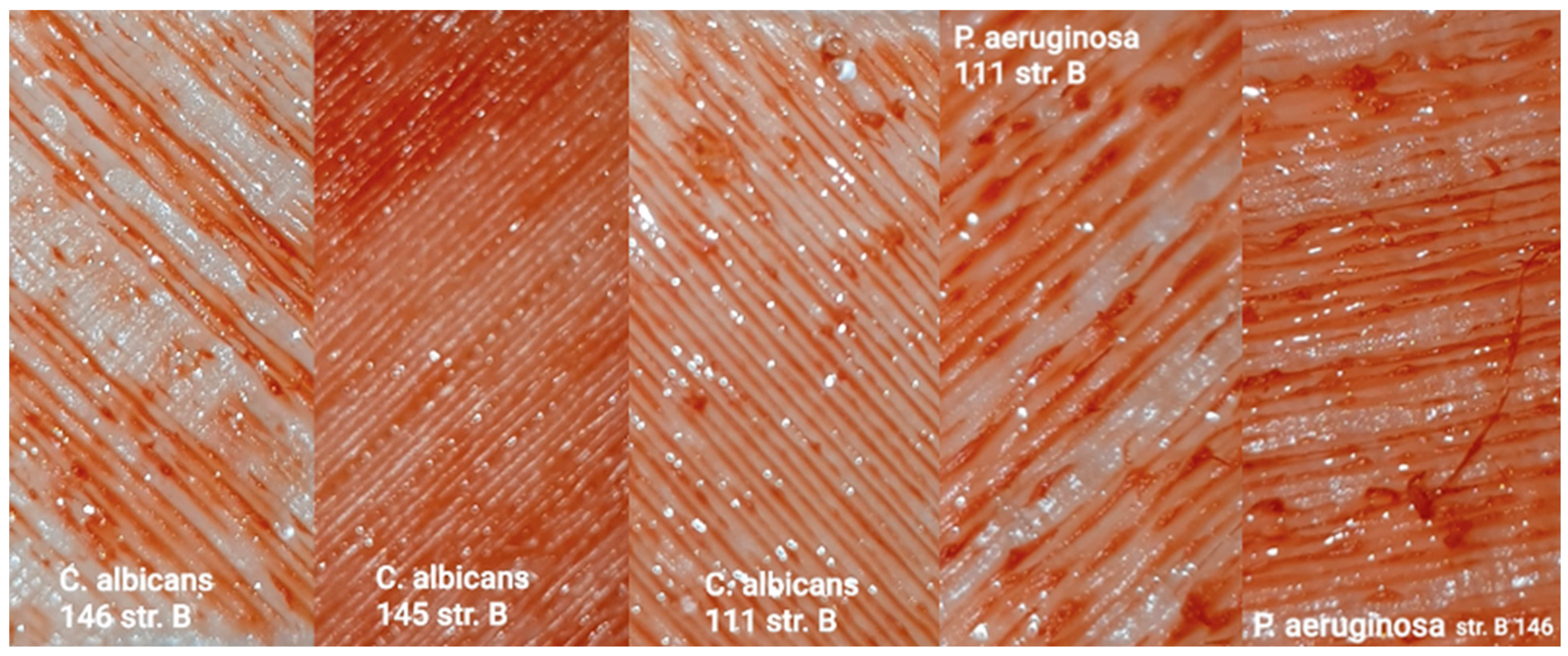

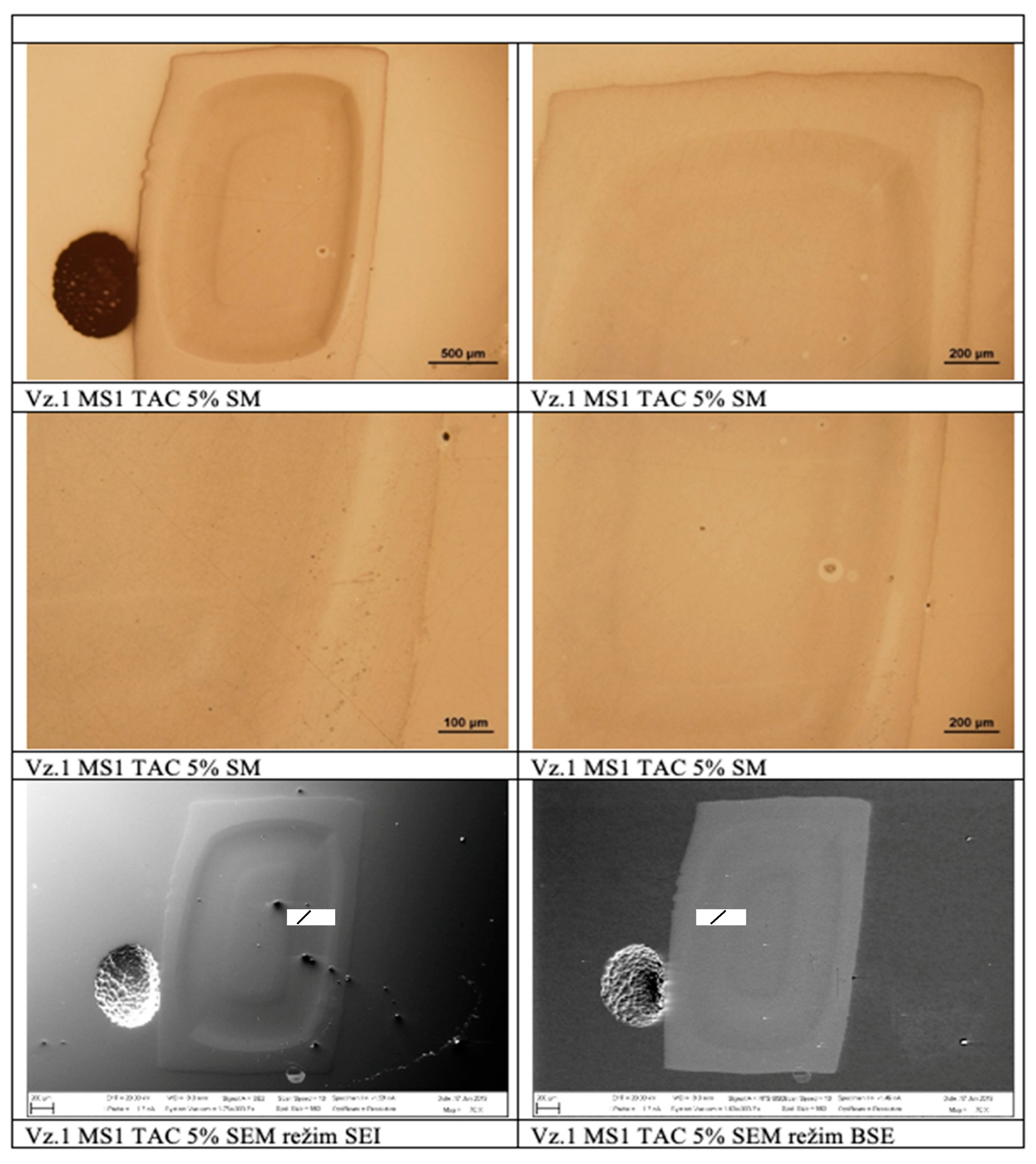

23]. It is very difficult to produce a suitable medical filament that meets all these requirements. However, this study provides new findings and makes a significant contribution to the solution to this issue, as we subjected our materials to rigorous analysis using light microscopy techniques and an Olympus GX71 instrument (microscope) with an Olympus DP12 camera. We chose the SEM (secondary electron mode) and BSE (backscattered electron mode) imaging modes. Bioimplants designed for sites in the human body with low mechanical stress in the form of bioresorbable stents represent unique solutions in this field and bring new possibilities to prevent various complications. Research and development efforts are directed towards the use of biocompatible implants made of materials such as PLLA, PGA, PLGA, and PCL because of their mechanical strength and biocompatibility [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. A key factor for long-term and reliable implant performance is good choice of biomaterial. Biological environments will not accept any material. Therefore, in order to optimize biological efficacy, implants should be chosen to reduce negative biological responses, while maintaining adequate function. To ensure the therapeutic efficacy of the implant, control of parameters is essential and three main factors should be considered: structure, mechanical properties, and biological properties [

31]. Optimization of mechanical properties is very important for the in vivo functioning of the implant. With this in mind, manufacturing parameters must be optimized to ensure maximum mechanical functionality. The basic mechanical requirements of implants include elastic modulus and tensile, compressive, and shear strength, yield strength, fatigue strength, hardness, and toughness [

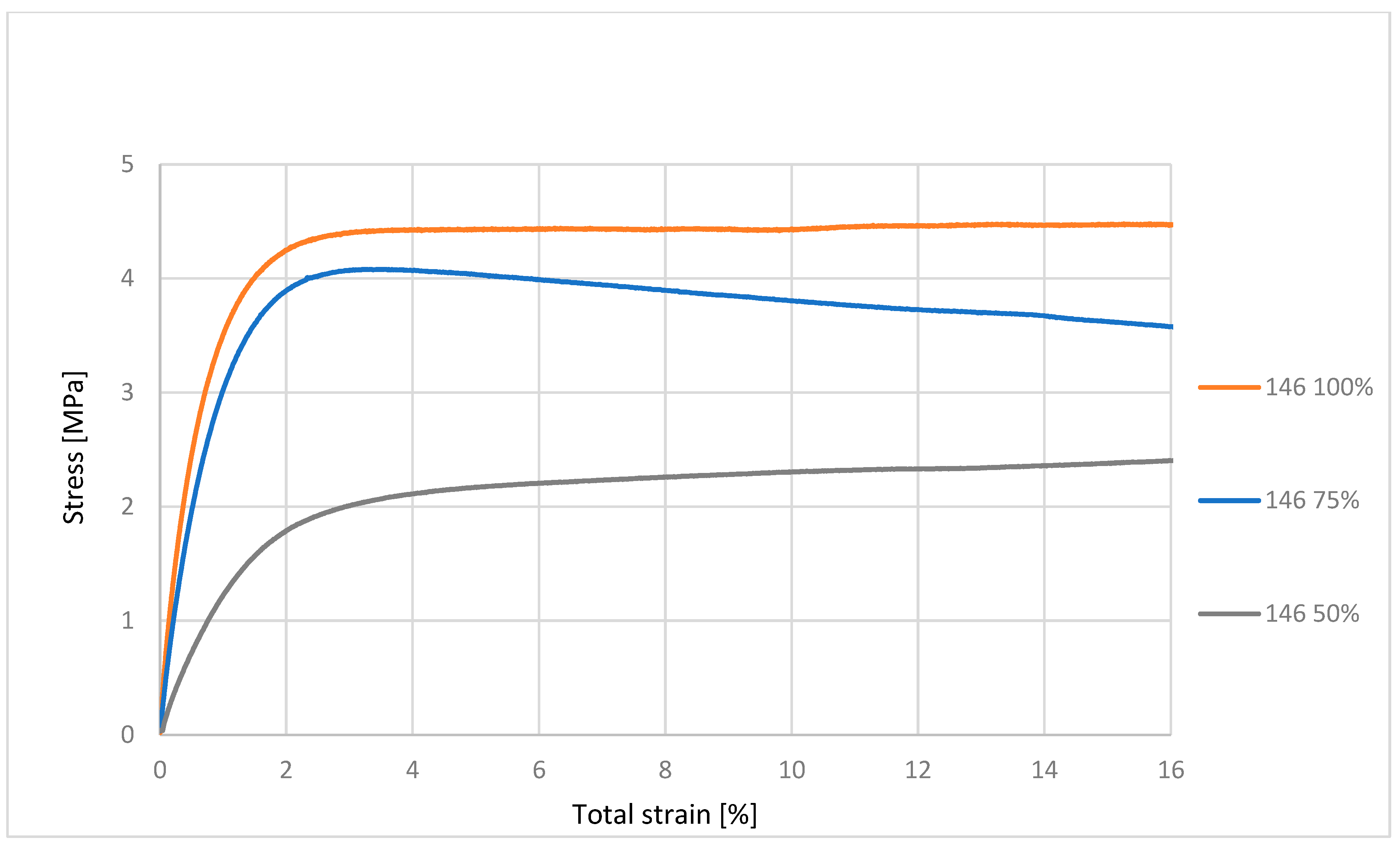

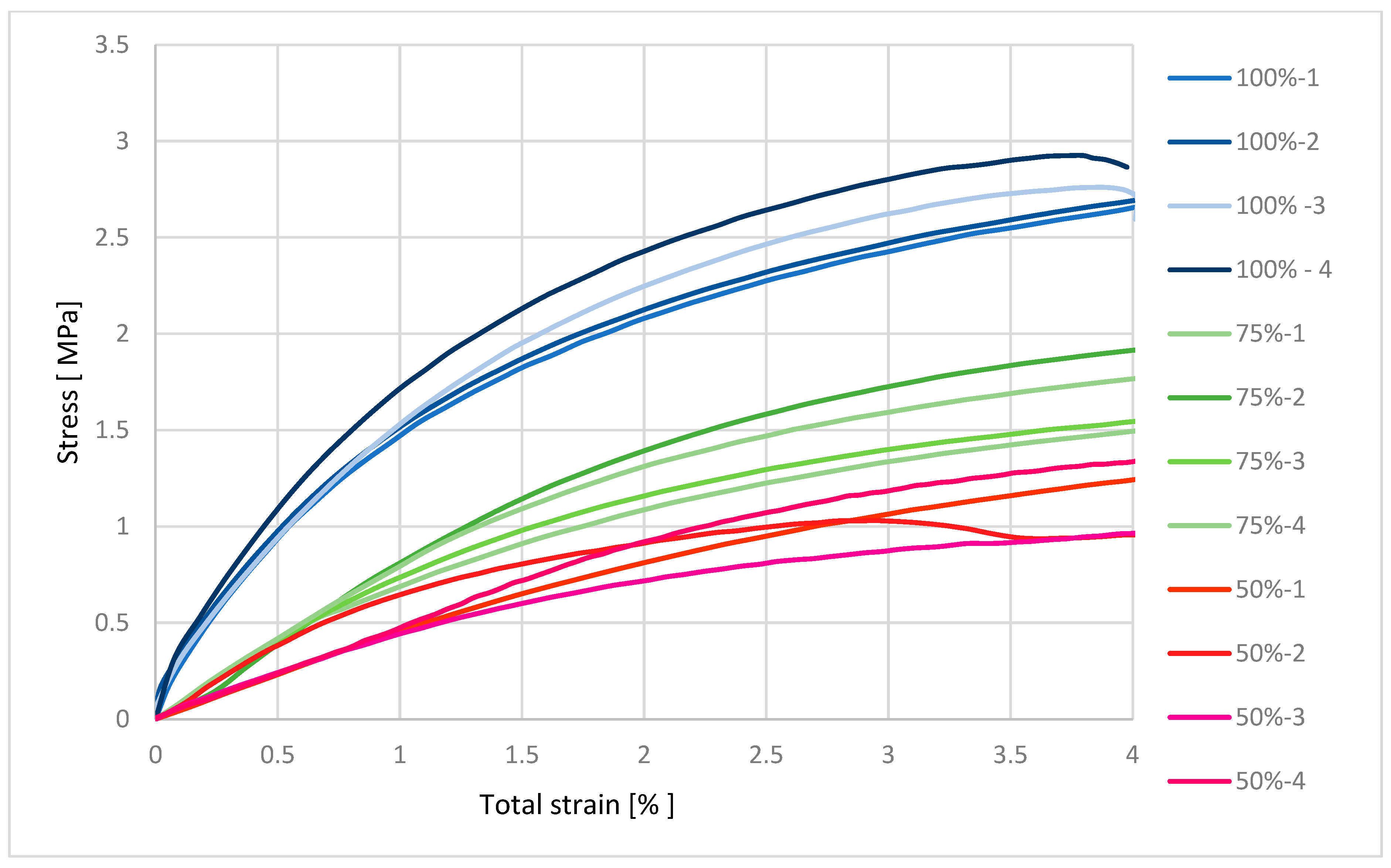

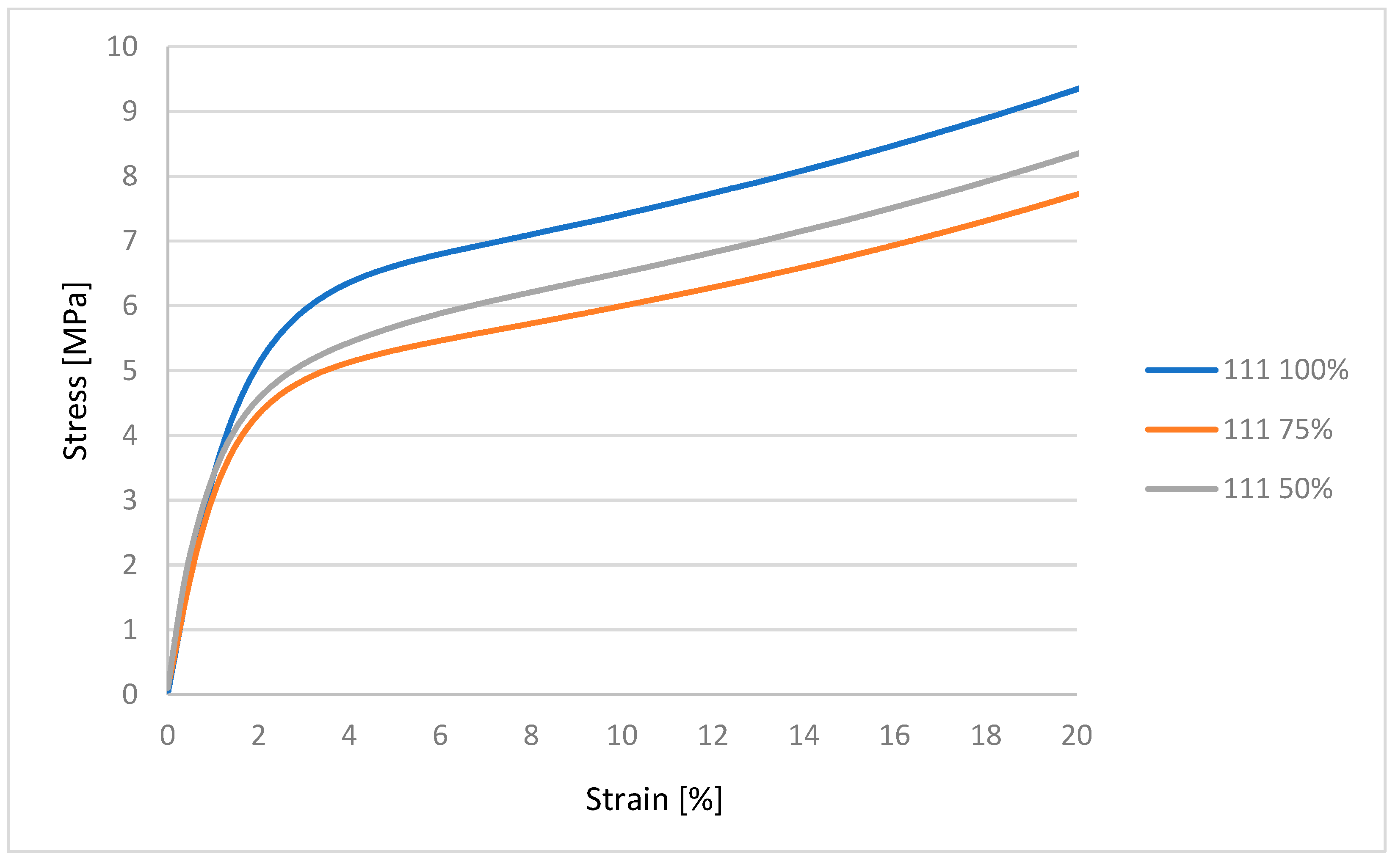

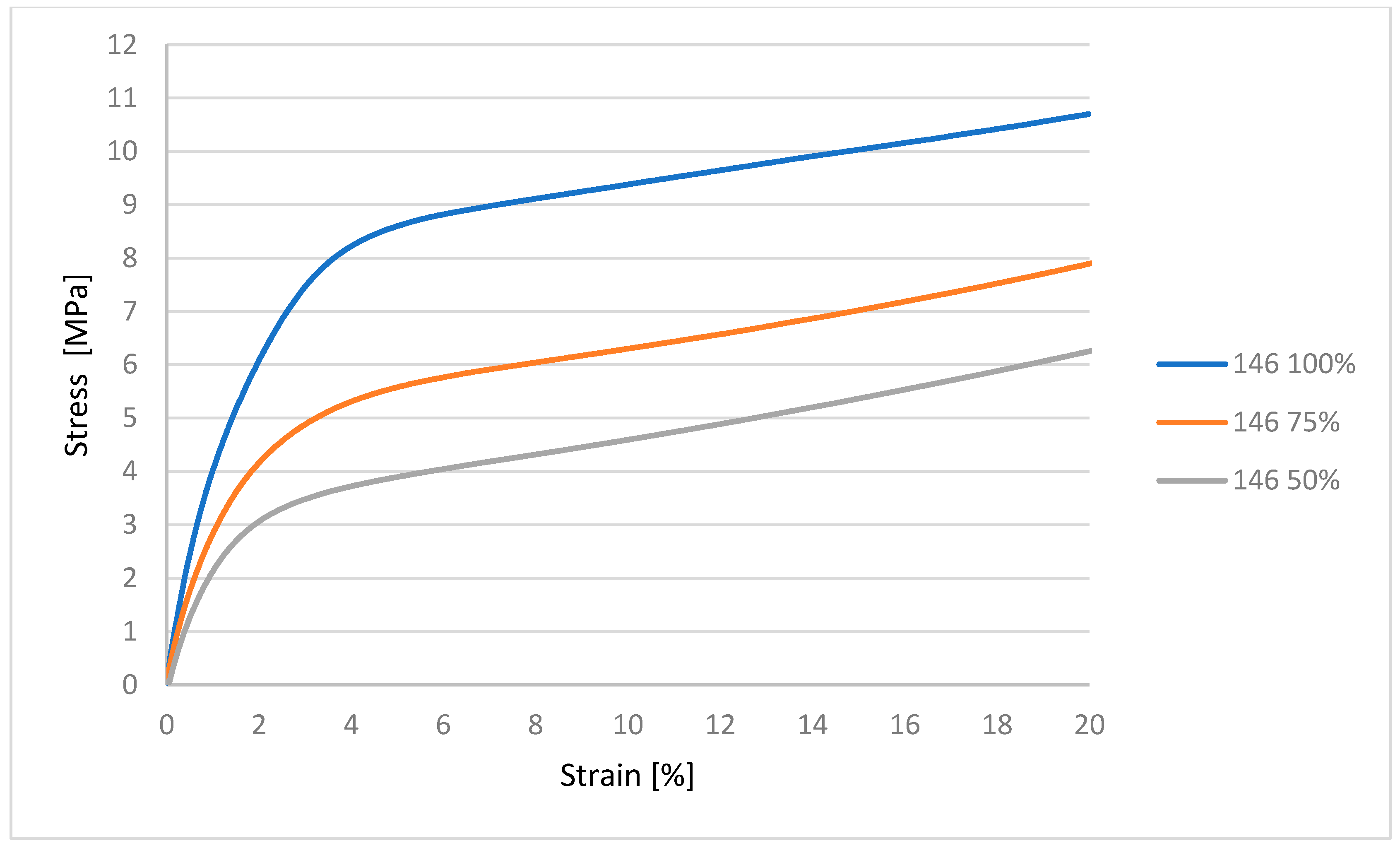

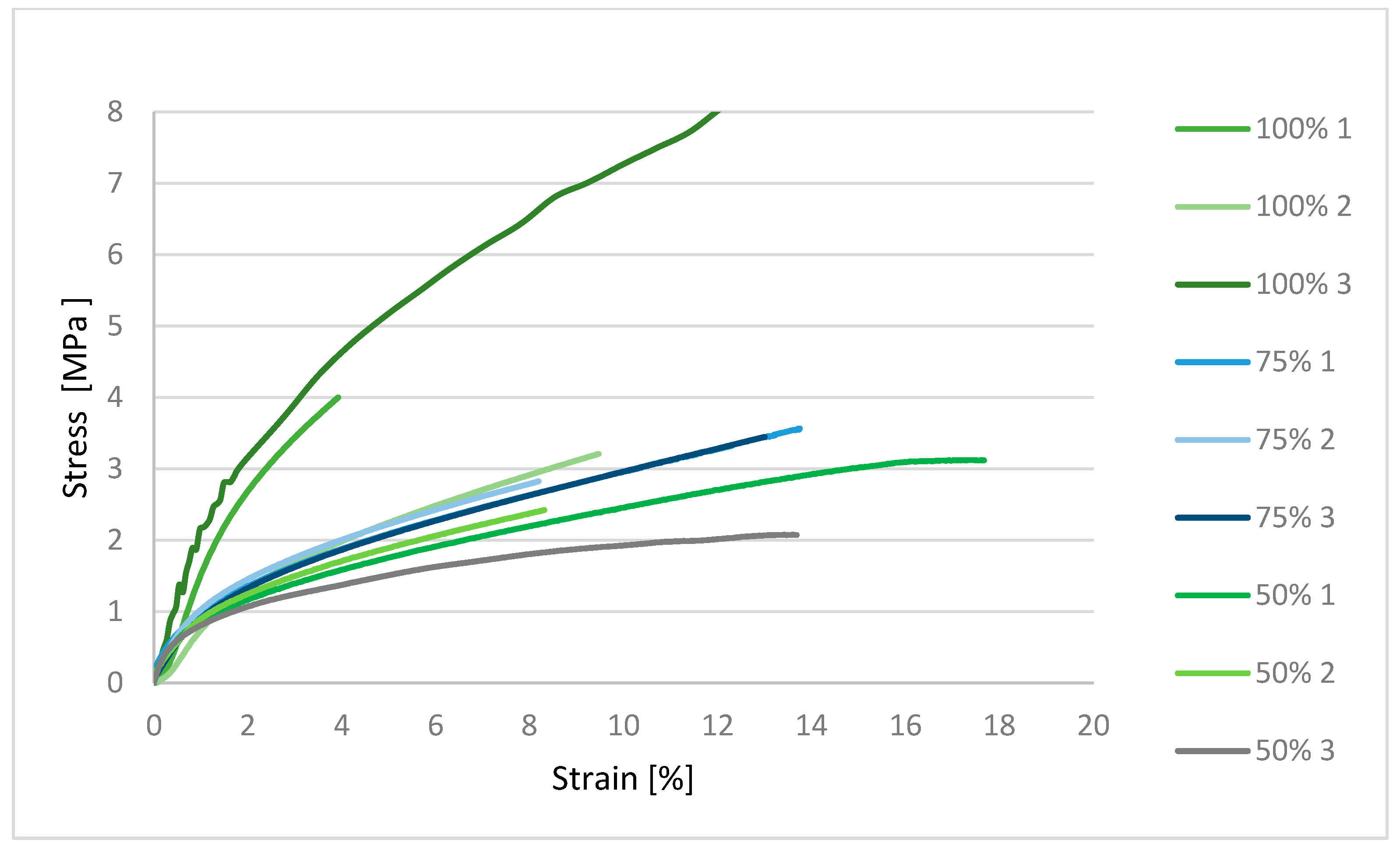

32]. Mechanical characterization using an MTS Insight testing system, combined with microbiological assessments against various bacterial and fungal strains, produced statistically significant data that are synthesized in the subsequent sections. These dual modalities of testing provide a comprehensive evaluation of both the structural robustness of the samples and their resistance to microbial colonization under relevant biological conditions [

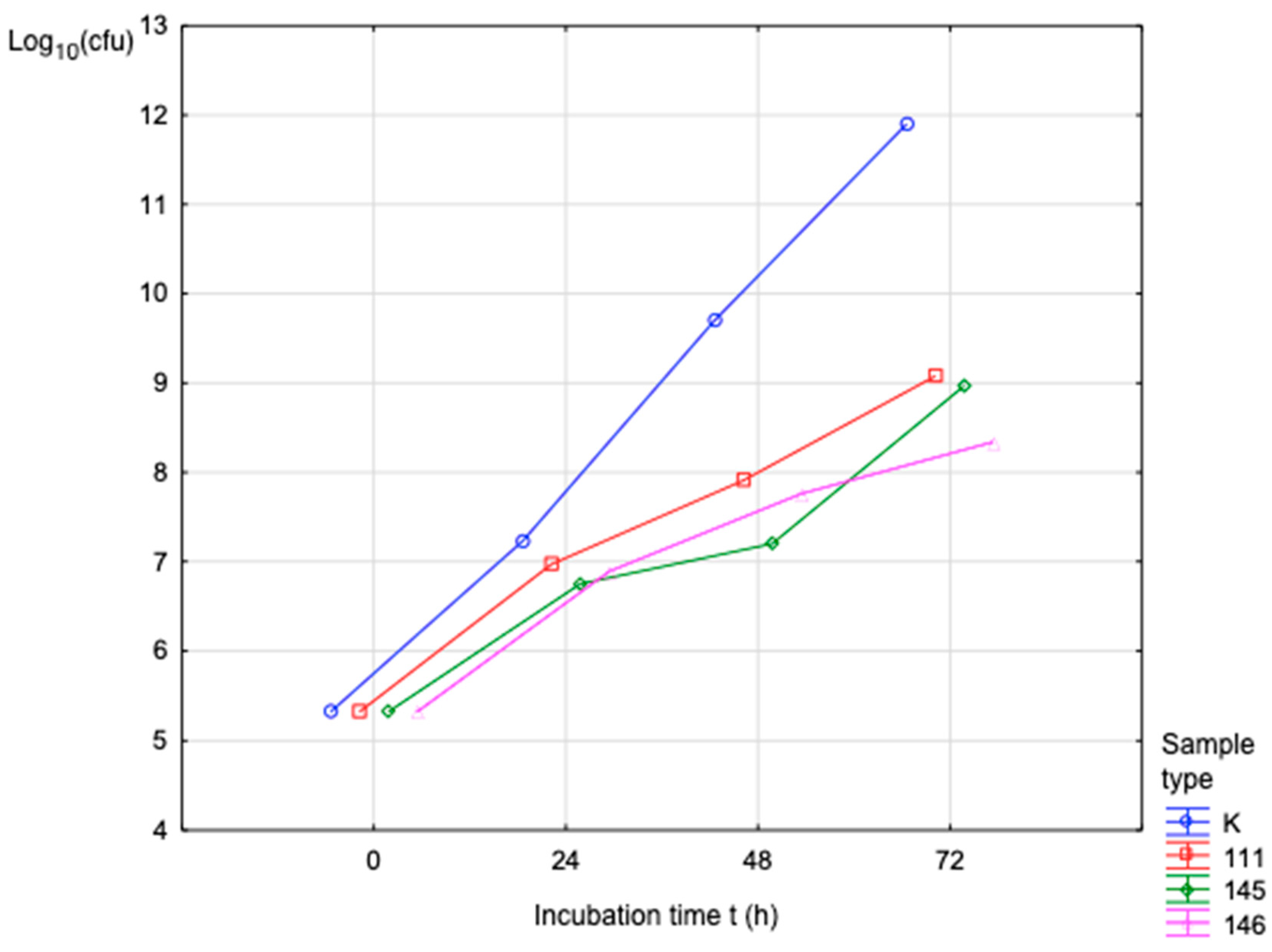

33,

34,

35]. Based on the studies conducted, the researchers focused on the following composition/purpose: PLA/PHB/TPS of various formulations, intended for 3D-printable scaffolding applications. Mechanics (E, σu): the authors measured mechanical properties for various blends, where the results show that the mechanical values are within the usable range for scaffolds, with the addition of TPS typically reducing stiffness and tensile strength compared to pure PLA components. Dimensional tolerances/accuracy: the authors document printed scaffolds with well-preserved geometry and porosity. Printability (deformation/threading): PLA/PHB/TPS blends were considered printable (the author provides printing parameters—temperatures, speed) and the printing did not show significant clogging; at higher TPS content, layer bonding may deteriorate. Degradation: samples were tested in water/hydrolytically and the authors describe that TPS increases hydrophilicity and water absorption, potentially accelerating degradation; specific degradation intervals in biological environments are not fully quantified. Biological testing: MTT tests and direct contact cytotoxicity tests were performed on human chondrocytes without toxic effects; cells adhered and proliferated on the scaffold [

36,

37,

38]. These studies show that PLA/PHB-based composites (with TPS and plasticizers or with bioactive fillers) are FDM-printable, exhibit mechanical properties suitable for 3D scaffolds, maintain the designed geometry and porosity, are biocompatible (no cytotoxicity, with cell adhesion and proliferation), and have potential as biodegradable tissue substitutes.