Tailoring Functionalized Lignin-Based Spherical Resins as Recyclable Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Uptake

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Materials

2.2. Characterizations

2.3. Preparation of Porous Spherical Lignin Beads from Pulping Black Liquor

2.4. Fabrication of Porous Cyanoethyl-Functionalized Spherical Lignin Beads

2.5. Preparation of Aminated Cyanoethyl-Functionalized Spherical Lignin Resin

2.6. Adsorption Experiments of Pb2+ Using ACSLR Adsorbent

2.7. Adsorption Kinetics Studies of Pb2+ Removal by ACSLR Adsorbent

2.8. Adsorption Isotherm Analysis of Pb2+ Removal by ACSLR Adsorbent

2.9. Desorption and Regeneration Studies of ACSLR Adsorbent for Pb2+ Removal

3. Results and Discussion

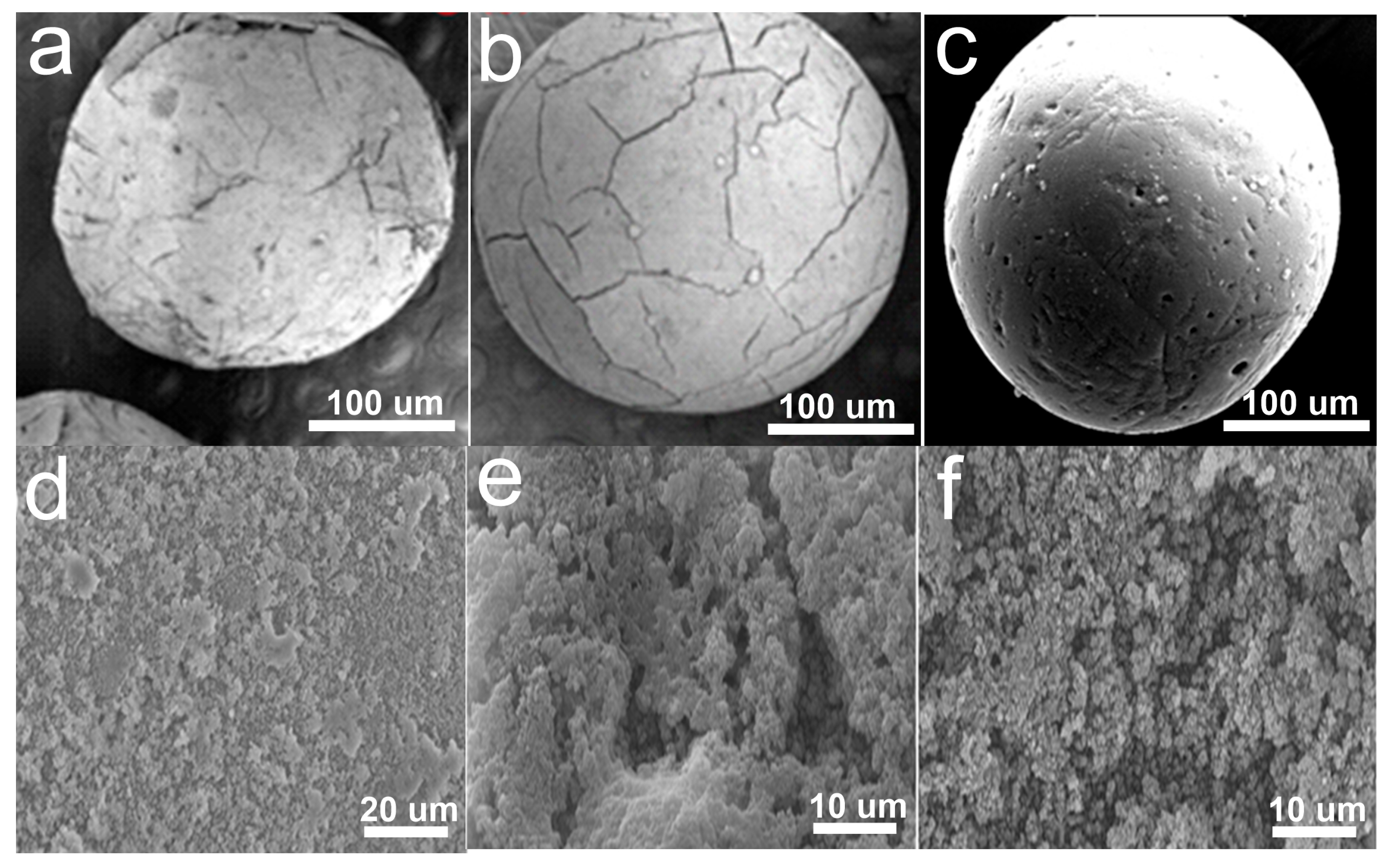

3.1. Morphology Analysis of ACSLR Before and After Pb2+ Adsorption

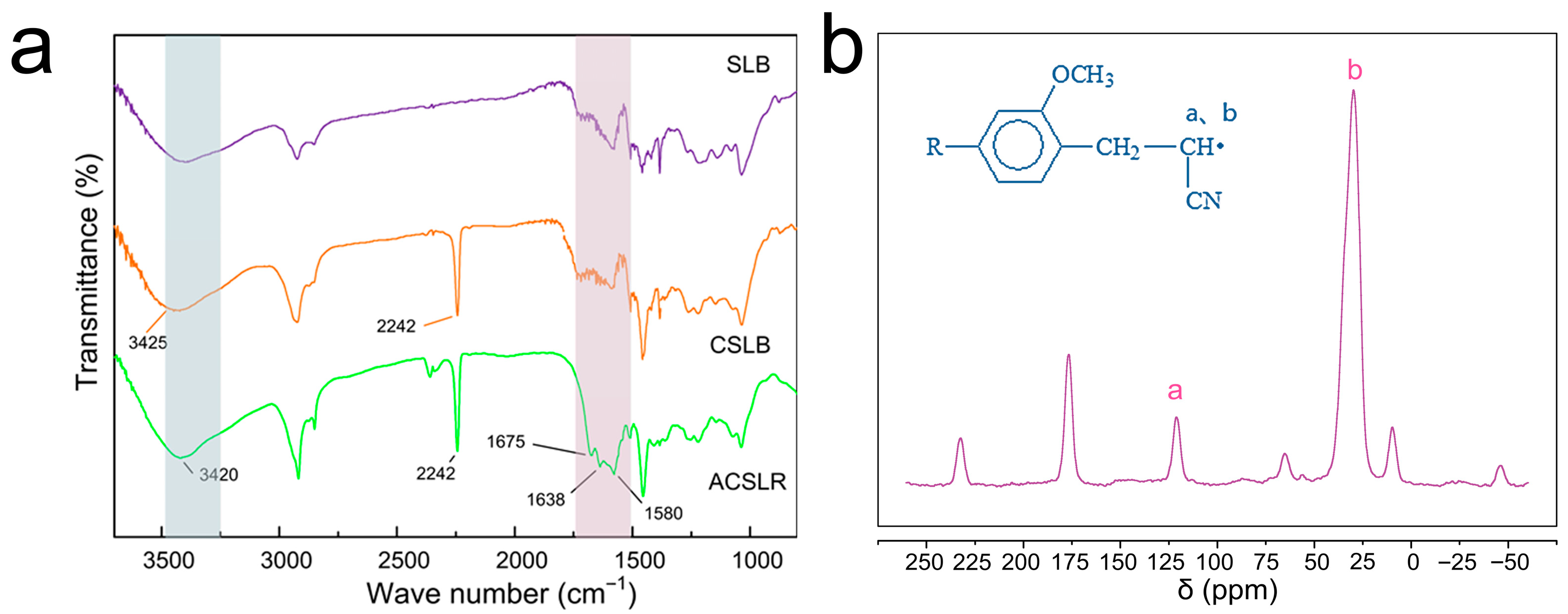

3.2. The Molecular Level Confirmation of the Adsorbent Synthesized by Step-by-Step Modification

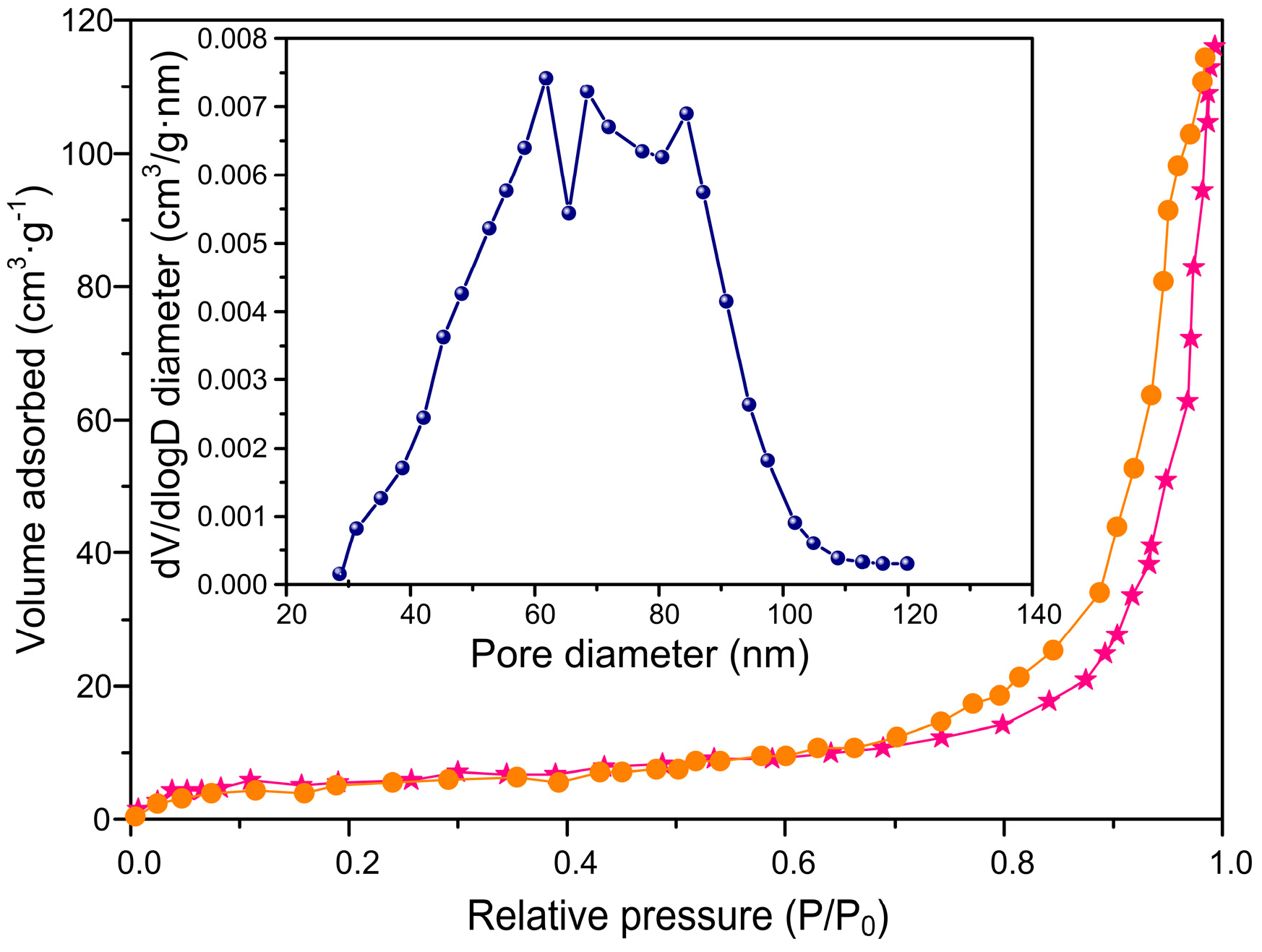

3.3. The Characterization of the Mesoporous Structure of ACSLR Adsorbent

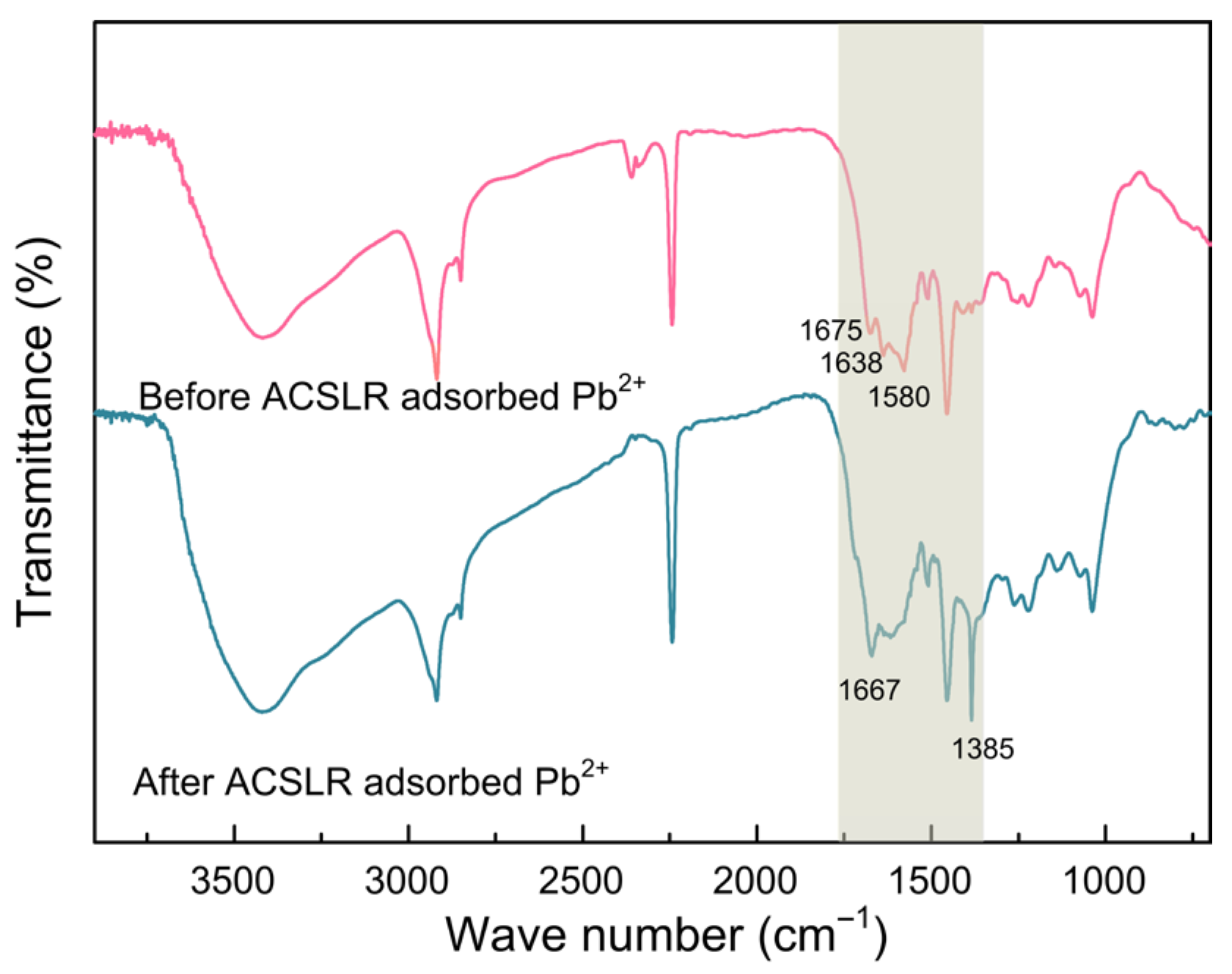

3.4. Comparison of Infrared Analysis of ACSLR Before and After Pb2+ Adsorption

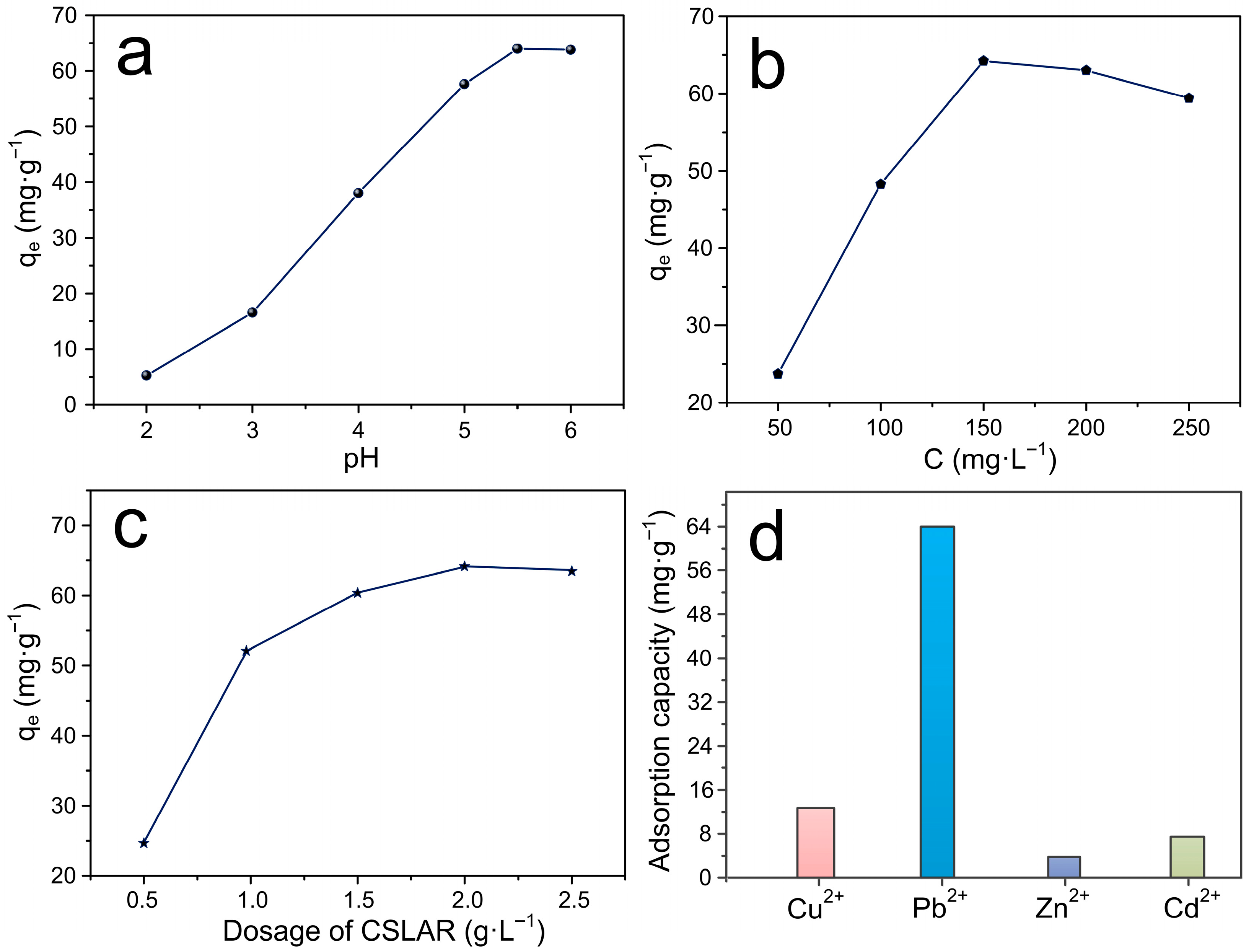

3.5. The Adsorption Law of Lead Ion Removal by ACSLR

3.6. Adsorption Kinetics Analysis

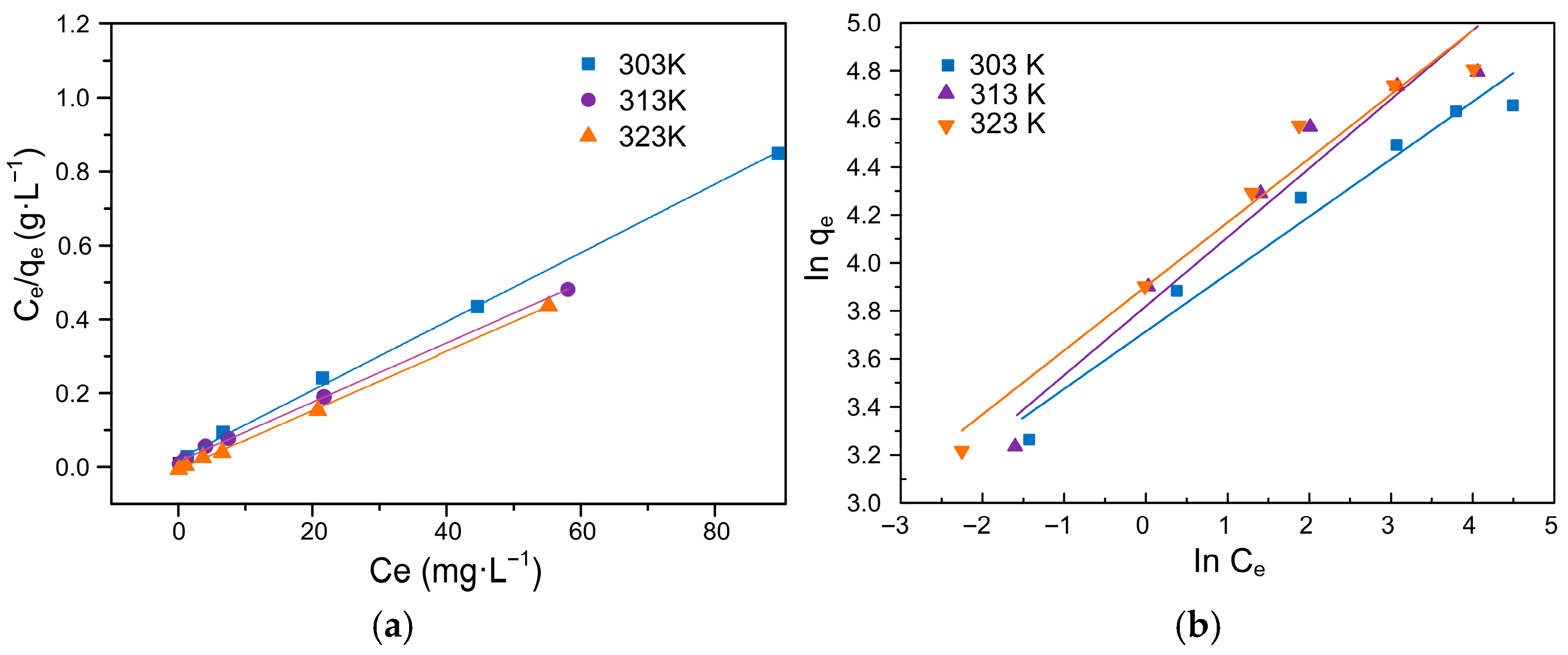

3.7. Adsorption Isotherm Analysis

3.8. Thermodynamic Study on the Adsorption of Pb(II) onto ACSLR

3.9. The Reusability and Stability of ACSLR Adsorbent for Removing Pb2+

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fan, L.; Tang, H.; Xu, K.; Xu, J.; Liu, G.; Chang, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, H. G-Quadruplex and DNAzyme dual-driven DNA detection system for real-time quantitative detection of environmental lead ions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 489, 137651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, B.; Guan, W.; Wang, H. Lead affects the proliferation and apoptosis of chicken embryo fibroblasts by disrupting intracellular calcium homeostasis and mitochondrial function. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 303, 118863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, M.S.; Venkatraman, S.K.; Vijayakumar, N.; Kanimozhi, V.; Arbaaz, S.M.; Stacey, R.S.; Anusha, J.; Choudhary, R.; Lvov, V.; Tovar, G.I. Bioaccumulation of lead (Pb) and its effects on human: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasem, N.A.; Mohammed, R.H.; Lawal, D.U. Removal of heavy metal ions from wastewater: A comprehensive and critical review. npj Clean Water 2021, 4, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, R.; Xu, Y.; Wei, G. Recent advances in biohybrid membranes for water treatment: Preparation strategies, nano-hybridization, bioinspired functionalization, applications, and sustainability analysis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 26967–27000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nthwane, Y.; Fouda-Mbanga, B.; Thwala, M.; Pillay, K. A comprehensive review of heavy metals (Pb2+, Cd2+, Ni2+) removal from wastewater using low-cost adsorbents and possible revalorisation of spent adsorbents in blood fingerprint application. Environ. Technol. 2025, 46, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelatontsev, D. Production of versatile biosorbent via eco-friendly utilization of non-wood biomass. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 451, 138811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaga, A.C.; Zaharia, C.; Suteu, D. Polysaccharides as support for microbial biomass-based adsorbents with applications in removal of heavy metals and dyes. Polymers 2021, 13, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Bansal, M.; Wilson, K.; Gupta, S.; Dhanawat, M. Lignocellulose biosorbents: Unlocking the potential for sustainable environmental cleanup. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 294, 139497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shen, D.; Wu, C.; Gu, S. State-of-the-art on the production and application of carbon nanomaterials from biomass. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 5031–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Li, L.; Deng, H.; Zhong, Y.; Deng, W.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Hu, X.; Wang, Y. Biomass-derived 2D carbon materials: Structure, fabrication, and application in electrochemical sensors. J. Mater. Chem. B 2023, 11, 10793–10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, H.N.; Idrus, S. Recent developments in the application of bio-waste-derived adsorbents for the removal of methylene blue from wastewater: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Wu, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, A.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Sun, K.; Li, S.; Zhou, J.; Li, B. Biomass-derived catalytically active carbon materials for the air electrode of Zn-air batteries. ChemSusChem 2024, 17, e202301779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Jiang, B.; Yuan, Y.; Li, M.; Wu, W.; Jin, Y.; Xiao, H. Biological activities and emerging roles of lignin and lignin-based products—A review. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 4905–4918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Shi, C.; Hong, Q.; Du, J.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Qu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H. Harnessing graft copolymerization and inverse vulcanization to engineer sulfur-enriched copolymers for the selective uptake of heavy metals. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 362, 131902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Jiao, H.; Guo, X.; Chen, G.; Guo, J.; Wu, W.; Jin, Y.; Cao, G.; Liang, Z. Lignin-based materials for additive manufacturing: Chemistry, processing, structures, properties, and applications. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2206055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, L.; Zheng, H.; Shen, T.; Wu, Z.; Xiong, T.; Liu, S.; Cao, J.; Peng, H.; Zhan, H.; Li, H. Engineering Biochar from biomass pyrolysis for effective adsorption of heavy metal: An innovative machine learning approach. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 361, 131592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sher, F.; Lima, E.; Anastopoulos, I.; Tran, H.; Hosseini-Bandegharaei, A. Is one performing the treatment data of adsorption kinetics correctly? J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 9, 104813. [Google Scholar]

- Senniappan, S.; Palanisamy, S.; Mani, V.M.; Umesh, M.; Govindasamy, C.; Khan, M.I.; Shanmugam, S. Exploring the adsorption efficacy of Cassia fistula seed carbon for Cd (II) ion removal: Comparative study of isotherm models. Environ. Res. 2023, 235, 116676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J.T.; Nunes, K.G.P.; Cardoso Estumano, D.; Feris, L.A. Applying the bayesian technique, statistical analysis, and the maximum adsorption capacity in a deterministic way for caffeine removal by adsorption: Kinetic and isotherm modeling. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 1530–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magesh, N.; Renita, A.A.; Siva, R.; Harirajan, N.; Santhosh, A. Adsorption behavior of fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin) using zinc oxide impregnated activated carbon prepared from jack fruit peel: Kinetics and isotherm studies. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Y.; Hu, Y.H. Design, synthesis, and performance of adsorbents for heavy metal removal from wastewater: A review. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 1047–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.; Qu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Miao, X.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Han, T.; Song, H.; Ma, S. Efficient scavenging of aqueous Pb (II)/Cd (II) by sulfide-iron decorated biochar: Performance, mechanisms and reusability exploration. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, F.; Zhuang, Q.; Huang, G.; Deng, H.; Zhang, X. Infrared spectrum characteristics and quantification of OH groups in coal. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 17064–17076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xin, M.; Xie, D.; Fan, S.; Ma, J.; Liu, K.; Yu, F. Variation in extracellular polymeric substances from Enterobacter sp. and their Pb2+ adsorption behaviors. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 9617–9628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, E.; Kim, H.; Choi, N.; Cho, K. The biochar derived from Spirulina platensis for the adsorption of Pb and Zn and enhancing the soil physicochemical properties. Chemosphere 2024, 364, 143203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul Zaman, H.; Baloo, L.; Kutty, S.R.; Aziz, K.; Altaf, M.; Ashraf, A.; Aziz, F. Insight into microwave-assisted synthesis of the chitosan-MOF composite: Pb (II) adsorption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 6216–6233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vesali-Naseh, M.; Naseh, M.R.V.; Ameri, P. Adsorption of Pb (II) ions from aqueous solutions using carbon nanotubes: A systematic review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Shi, L.; Yi, K.; Zhang, C.; Pang, H.; Li, J.; Li, S. Investigation of the adsorption behavior of Pb (II) onto natural-aged microplastics as affected by salt ions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xiong, C.; He, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, X.; Zheng, J.; Wang, S. Facile preparation of magnetic Zr-MOF for adsorption of Pb (II) and Cr (VI) from water: Adsorption characteristics and mechanisms. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 415, 128923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Fu, L.; Zhang, L. Novel magnetic covalent organic framework for the selective and effective removal of hazardous metal Pb (II) from solution: Synthesis and adsorption characteristics. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 307, 122783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wang, B.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, F. Adsorption of Pb (II) in water by modified chitosan-based microspheres and the study of mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, W.; Mehmood, S.; Mahmood, M.; Ali, S.; Shakoor, A.; Núñez-Delgado, A.; Asghar, R.M.A.; Zhao, H.; Liu, W.; Li, W. Adsorption of Pb (II) from wastewater using a red mud modified rice-straw biochar: Influencing factors and reusability. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 326, 121405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.; Vincent, C.; Kirthika, K.; Kumar, K.S. Kinetics and equilibrium studies of Pb2+ ion removal from aqueous solutions by use of nano-silversol-coated activated carbon. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.; He, S.; Han, C.; Luo, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, N.; Dionysiou, D.D. Facile synthesis of amino-functional large-size mesoporous silica sphere and its application for Pb2+ removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 378, 120664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Tang, X.; Yuan, J.; Li, Q.; Qi, L.; Wang, H.; Ye, Z.; Zhao, Q. Activated sludge process enabling highly efficient removal of heavy metal in wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 21132–21143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Chu, Y.; Muhmood, T.; Xia, M.; Xu, Y.; Yang, L.; Lei, W.; Wang, F. Adsorption properties of Pb2+ by amino group’s functionalized montmorillonite from aqueous solutions. J. Chem. Eng. Data 2018, 63, 2940–2949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, G.; Xie, S.; Mao, B.; Chen, H.; Xue, Y.; Xu, Q.; Guo, J.; Dai, M. Tailoring Functionalized Lignin-Based Spherical Resins as Recyclable Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Uptake. Polymers 2025, 17, 3324. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243324

Xiao G, Xie S, Mao B, Chen H, Xue Y, Xu Q, Guo J, Dai M. Tailoring Functionalized Lignin-Based Spherical Resins as Recyclable Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Uptake. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3324. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243324

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Gao, Shumin Xie, Bizheng Mao, Hong Chen, Yiwei Xue, Qingmei Xu, Jie Guo, and Manna Dai. 2025. "Tailoring Functionalized Lignin-Based Spherical Resins as Recyclable Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Uptake" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3324. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243324

APA StyleXiao, G., Xie, S., Mao, B., Chen, H., Xue, Y., Xu, Q., Guo, J., & Dai, M. (2025). Tailoring Functionalized Lignin-Based Spherical Resins as Recyclable Adsorbents for Heavy Metal Uptake. Polymers, 17(24), 3324. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243324