1. Introduction

As the global energy transition progresses and the electrification of the transportation sector expands, emission-free propulsion and energy storage solutions are gaining increasing relevance. Polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) technology is pivotal in facilitating the commercial use of hydrogen as a potential energy storage medium for medium- and long-distance transportation, including trucks, marine vessels, and aviation, as well as for stationary and decentralized energy supply systems within the broader energy sector [

1]. However, for widespread adoption, significant improvements in both the cost-effectiveness and lifespan of PEMFC systems are essential to make them competitive with conventional fossil-fuel-based propulsion and storage technologies [

2]. The optimization of stack design and the construction of individual fuel cell components should ideally focus on enhancing both performance and longevity [

3], while minimizing the thickness and volume of the components to reduce costs and save space [

4]. In addition to these design challenges, the materials used must meet stringent demands. Among the components, the bipolar plate stands out as having the most critical requirements and potential for optimization, as it accounts for 30–40% of the overall cost [

5] and up to 80% of the total weight of a fuel cell [

6]. Therefore, the bipolar plate must exhibit high electrical conductivity, mechanical stability, and corrosion resistance, while also being lightweight, compact, affordable, and efficiently replicated channel structures for gas distribution [

2]. Current research focuses on both metallic and polymer composite materials to meet these demands. Metallic materials offer high electrical conductivity and mechanical strength, flexibility [

7], and low component thickness [

8]. However, they are prone to corrosion and oxidation due to the reaction products formed during electrochemical processes [

9]. This leads to increased contact resistance, reduced power output, and shorter cell lifespans [

10], often necessitating costly and complex corrosion-resistant coatings [

4]. Current developments include the improvement of corrosion resistance through the use of advanced coatings [

11], the improvement of current coating processes [

12], the usage of new materials such as titanium [

13], and the improvement of current production processes like forming and stamping [

14]. Among the coatings, pure carbon coatings [

15], Cr-doped a-C coatings [

16], conductive polymer coatings [

11], transition metal carbides (TMCs) [

17], metal nitride and carbide films [

18], and precious metal coatings [

12] are the most important representatives that are currently the subject of particular attention in research [

14]. Moreover, the production of metallic bipolar plates is constrained by either inefficiency and high processing costs [

19] or limitations in channel structure complexity, with high aspect ratios frequently causing dimensional errors, cracks, and wrinkles due to substrate thinning [

20]. On the other hand, polymer composite-based bipolar plates are emerging as a technically and economically viable alternative. They offer distinct advantages, including reduced specific weight, enhanced corrosion resistance [

21], durability [

10], high functional integration within complex 3D geometries, and lower production costs [

22].

The electrical insulating properties of polymers, which are disadvantageous for this application, can be significantly modified through the incorporation of various fillers and additives into the polymer matrix. The introduction of conductive elements such as fibers, flakes, or spherical particles made from metals, conductive carbon black, graphite, or nanofillers like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) can reduce the resistivity of polymers by several orders of magnitude [

23]. Several studies have attempted to improve the electrical conductivity of polymer-based bipolar plates by modifying the filler, using materials such as graphite powder [

24] or conductive carbon black in combination with carbon microspheres [

25]. Roth et al. showed that with a total filler content of 80 wt.% of graphite flakes [

26], improved bipolar plates with excellent electrical conductivity properties can be achieved.

To use the cost and durability advantages of polymers in the production of bipolar plates, it is essential to achieve high filler content to ensure adequate electrical conductivity. However, such modifications to thermoplastic melts lead to significantly increased viscosity and negatively impact melt thermal conductivity, thereby impeding mold filling and replication quality. This, in turn, restricts the achievable thickness and dimensional stability of bipolar plates produced via injection molding [

26]. In contrast, metallic bipolar plates are already being produced with thicknesses as low as 100 μm [

8], highlighting that the weight benefits of polymer-based plates have yet to be fully utilized.

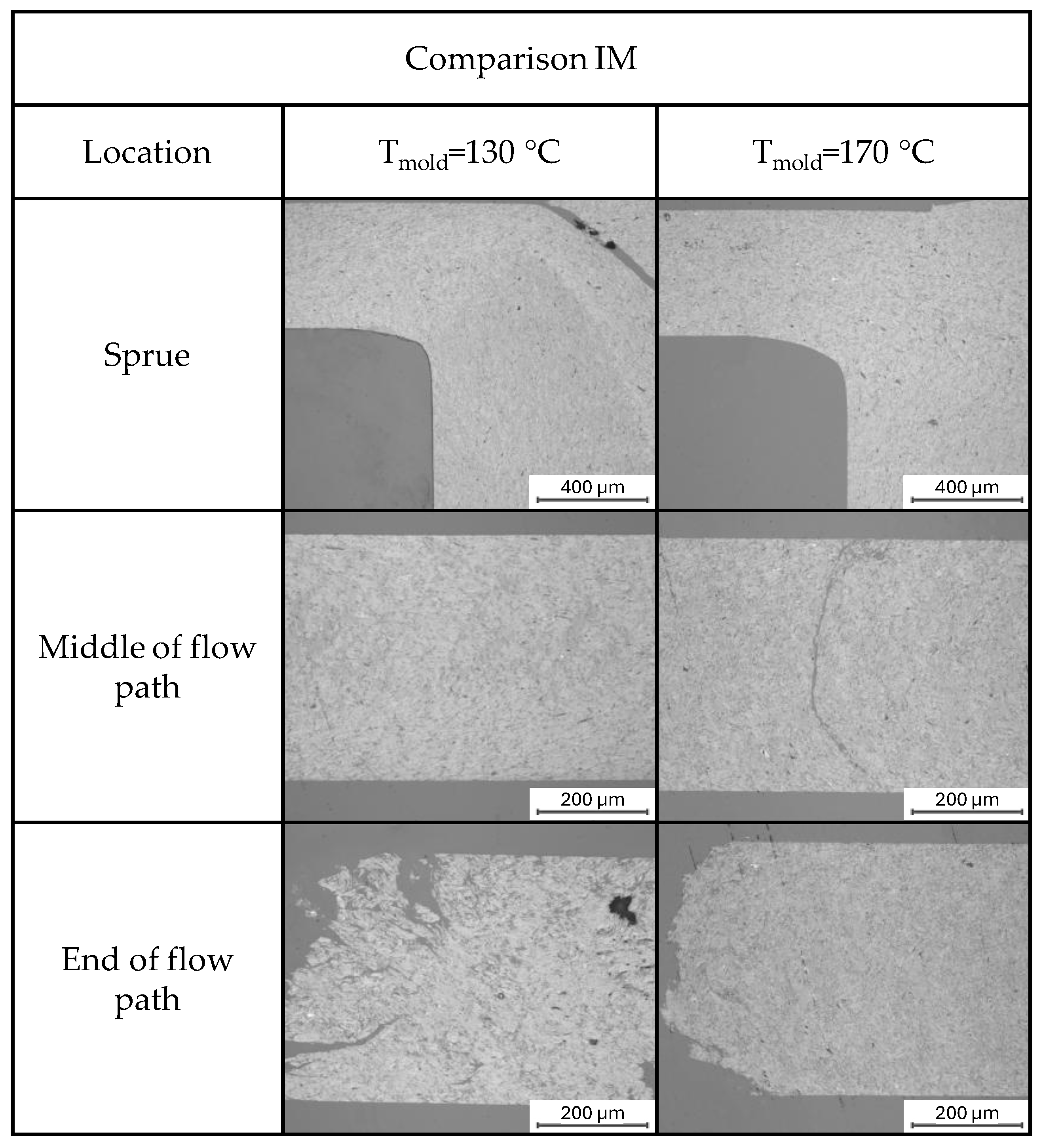

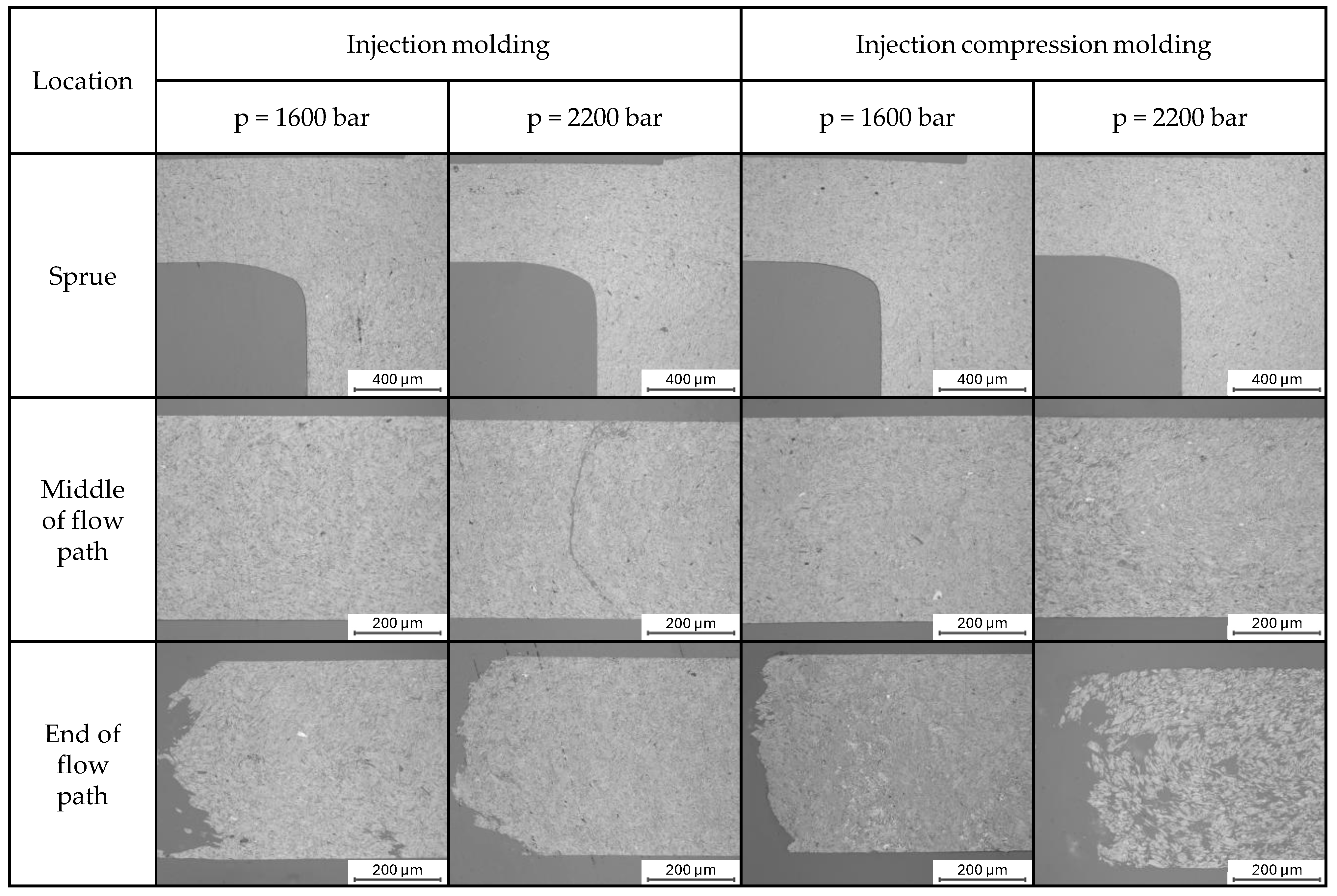

Given that the output voltage of a single cell is capped at a maximum of 1.23 V, multiple cells must be connected in series to achieve higher voltages. Consequently, thicker polymer-based plates contribute to increased space requirements and higher costs. Reduced plate thicknesses result in a diminished flow cross-section. Higher injection speeds and elevated mold temperatures therefore seem necessary but have proven to be insufficient, as these approaches lead to excessive pressure demands during filling [

27] and generate non-uniform pressure and temperature distributions along the flow path [

28]. At the component level, these challenges manifest as flow-path-dependent variations in thickness accuracy [

29] and reduced precision in molding the intricate channel structures [

6].

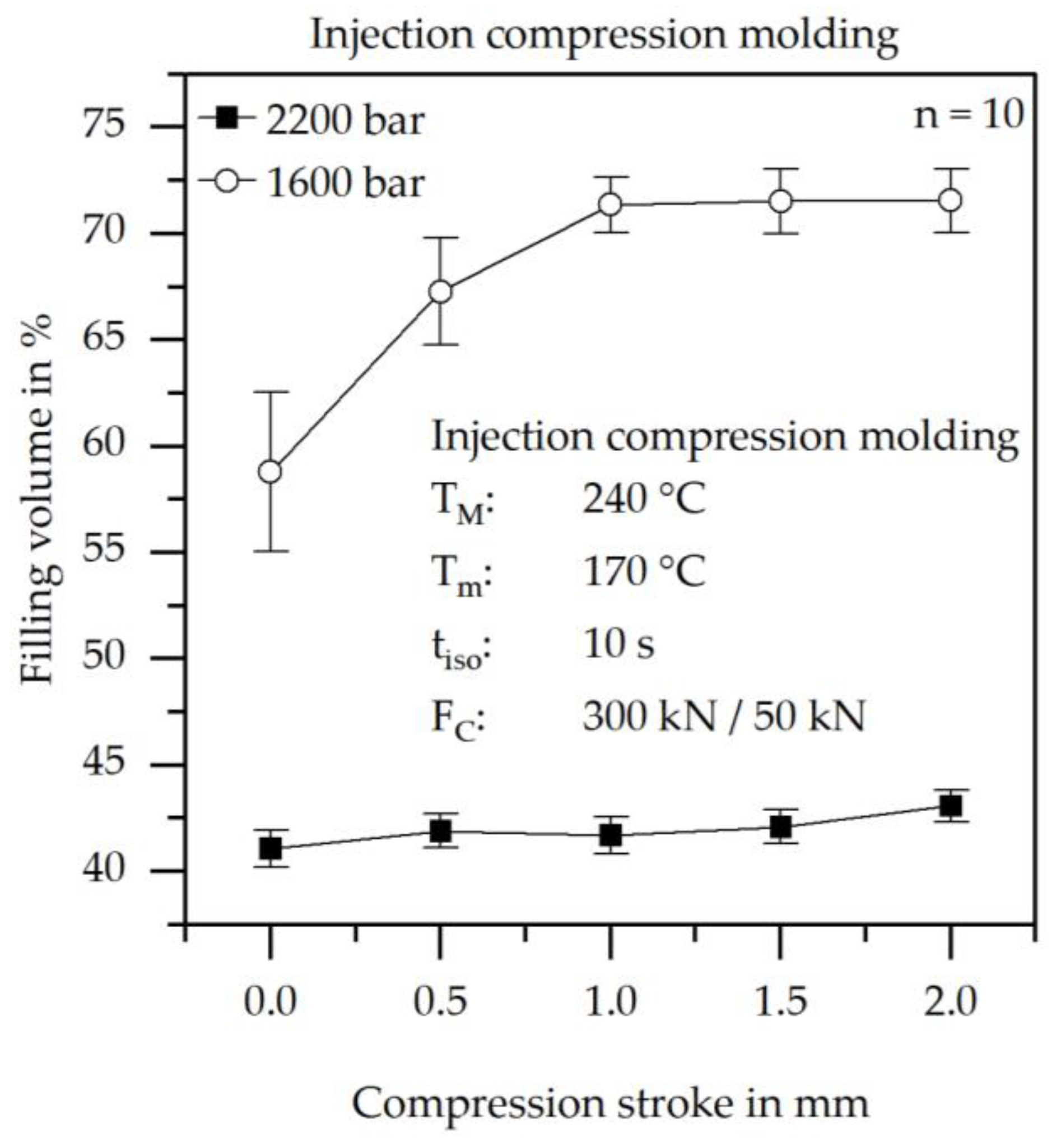

Rzeczkowski et al. [

27] showed with an isothermal mold temperature that the injection molding process is limited to an aspect ratio of 40 with a plate dimension of 80 × 80 × 2 mm

3. The material that was used was PP with 80 wt.% of graphite. Brokamp et al. [

30] achieved an aspect ratio of ~48 with plate dimensions of 142.5 × 80 × 3 mm

3 and a highly filled PPS graphite compound with a filler content of 75 wt.%. Roth et al. [

26] showed that with an injection compression molding (ICM) process with a dynamic mold control (DT), aspect ratios of up to 90 can be achieved. Due to the limitations of the maximum compression stroke of the mold used by Roth et al., it was not possible to further investigate which maximum aspect ratios can be achieved in the ICM-DT process. The literature search did not reveal any other peer-reviewed research activities other than the work of Roth et al. [

26] in the field of bipolar plate production by injection compression molding with dynamic mold control.

Numerical investigations represent a frequently applied method for analyzing the maximum achievable ratio of flow path length to wall thickness in more detail. By using simulations, costly and complex iterative processes with physical molds can be avoided. The maximum ratio of flow path length to wall thickness can be determined before the final mold is built. The basis for determining the maximum flow paths and the aspect ratio is the accuracy of the simulation and the material models. Therefore, the usage of pressure-dependent viscosity models is recommended by Wang et al. for simulating parts with high surface-to-volume ratio (S/V) [

31].

During processing, small components face different time–temperature–pressure conditions compared to larger parts [

32]. The higher surface-to-volume (S/V) ratio of micro- and thin-walled components causes a faster heat transfer between the melt and the mold [

33]. As a result, the melt cools faster across the cross-section, which increases flow resistance because of the increasing viscosity due to the temperature decrease [

32]. In addition, the solidified surface layers take up more of the flow cross-section than in larger components, making it harder to fill the mold and accurately replicate fine surface details [

34]. To address the increase in the viscosity, higher mold temperatures [

35] or faster injection speeds [

36] are used. However, faster injection speeds, combined with smaller flow cross-sections, require higher pressures during the filling phase [

37]. For example, Yokoi et al. [

38] observed injection pressures up to 3000 bar at a speed of 1000 mm·s

−1 over a flow path of 150 mm with a plate thickness of 2 mm. In general, the highest pressure occurs close to the sprue due to the high deformation of the melt by shear and elongation [

32]. The pressure decreases throughout the flow path, which creates a pressure gradient [

39]. The pressure gradient decreases as the melt flows, resulting in different pressure levels along the flow path [

40]. Studies on thin-walled injection-molded parts have shown that uneven pressure distribution during filling leads to noticeable variations in density [

41] and thickness [

29] along the flow path, regardless of whether dynamic or conventional isothermal mold temperature control is used. The highest density and thickness occur near the gate, where the polymer solidifies under maximum pressure, while at the flow path’s end, the polymer solidifies under minimal pressure influence [

28]. Since the viscosity of highly filled material strongly depends on pressure [

42], the high injection pressures required for thin-walled molding further increase viscosity, making it even harder to achieve accurate replication and dimensional stability.

In addition to its influence on melt viscosity, hydrostatic pressure also affects the crystallization behavior of semi-crystalline thermoplastics [

43]. High-pressure studies on isotactic polypropylene (iPP) have shown that increasing pressure shifts the crystallization temperature to higher values and accelerates the nucleation kinetics, resulting in increased nucleation densities and earlier onset of crystallization compared to ambient pressure conditions [

44]. In nanocomposite systems, such as iPP filled with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), the combined effect of filler-induced nucleation and elevated pressure promotes the formation of the orthorhombic γ-phase instead of the α-phase. Furthermore, the crystallization temperature and nucleation density are further increased, while the spherulite size is reduced compared to the unfilled polymer [

45]. Under high-pressure processing conditions, such as injection molding or injection compression molding, solidification may therefore occur earlier not only due to the pressure-induced increase in viscosity but also as a result of pressure-induced crystallization [

46]. This premature solidification can lead to an early flow arrest and directly affects the achievable flow path lengths as well as the final morphology of the molded components.

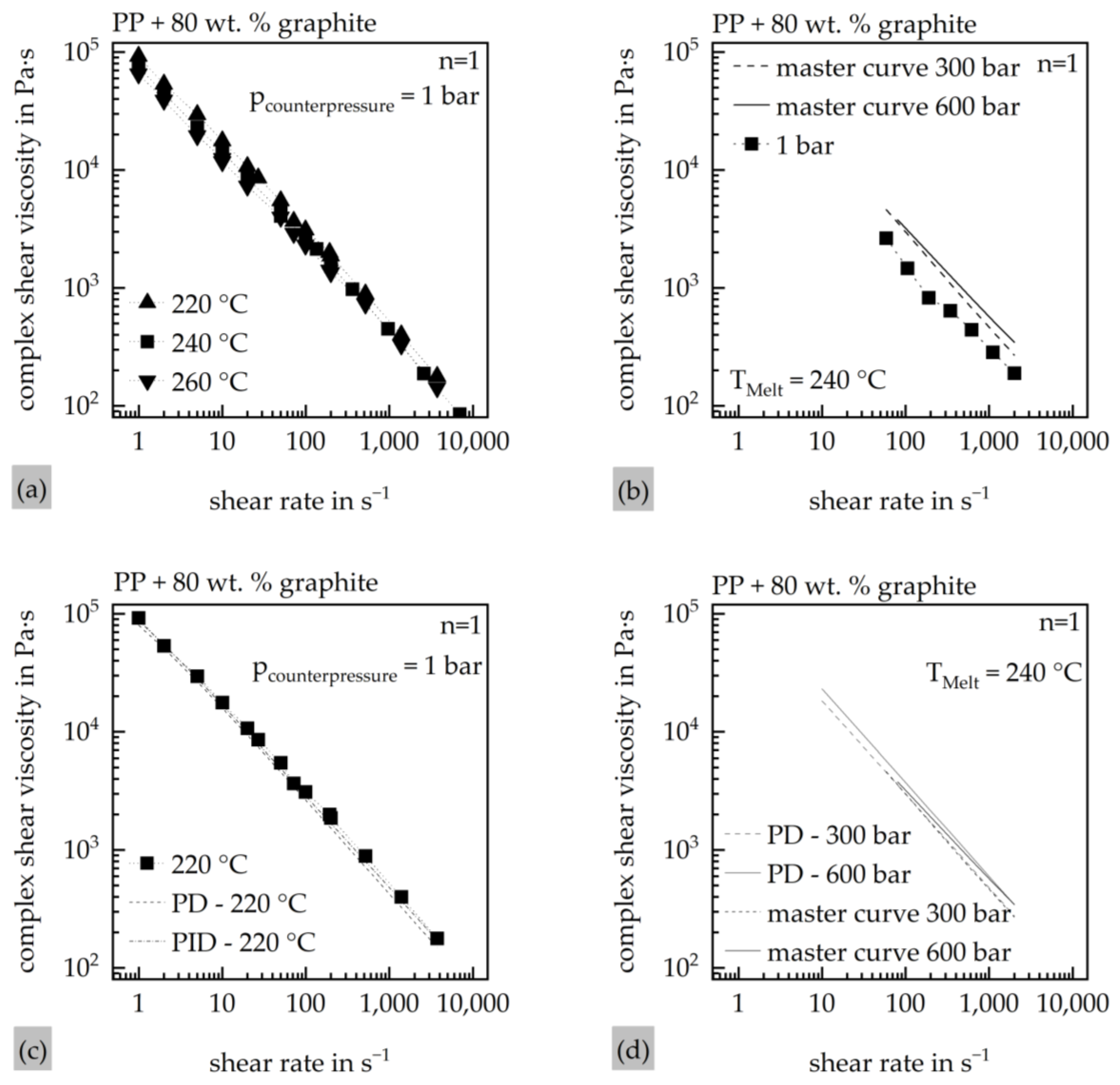

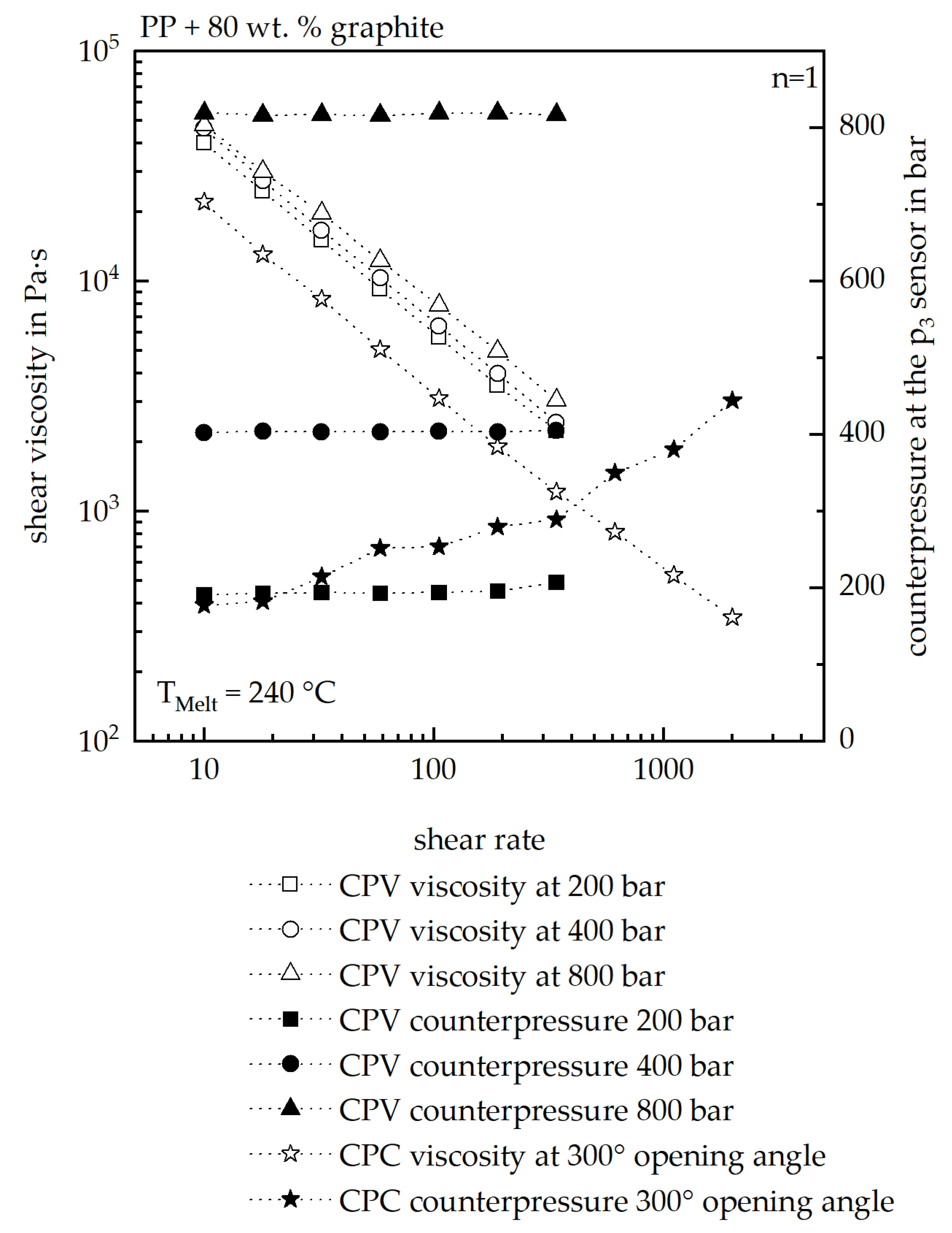

In general, the viscosity can be modeled by a Cross–WLF model, where the Cross model models the shear thinning behavior of the polymer [

47] while the influence of the temperature is modeled by the WLF model [

48]. The Cross–WLF model incorporates temperature and pressure effects into zero-shear viscosity using WLF shift factors [

49]. The Cross model is shown in Equation (1).

The model contains three parameters where τ* accounts for the critical shear stress, n is the shear thinning coefficient, and

η0 is the value of the viscosity when the shear rate approaches zero. The WLF zero shear viscosity is presented in Equation (2).

where D

1, D

2, A

1, and A

2 are coefficients for fitting the temperature dependency. In the specific context of accounting for the pressure effect, the WLF formulation for zero-shear viscosity can be expressed as shown in Equation (3) [

50].

The parameter D

3 denotes the pressure dependency, while P is the pressure acting on the polymer melt. Modeling the pressure dependency of viscosity requires numerous measurements under pressure, often using advanced and complex equipment [

32]. As a result, most material models in simulation software set the pressure coefficient to zero (D

3 = 0 K∙Pa

−1) [

48], effectively ignoring pressure dependency in these models [

51]. When pressure dependency is included, the D

3 parameter is usually represented as a single constant value. However, this simplification does not capture the actual behavior of thermoplastics, where the D

3 parameter significantly depends on shear rate [

52], temperature [

53], and pressure [

54], as shown in many studies [

50]. Furthermore, most simulation databases do not define a solidification criterion that accounts for the flow stopping due to a pressure-induced exponential increase in viscosity [

46]. Instead, flow is usually restricted by a temperature-dependent “no-flow” criterion, corresponding to the crystallization temperature and its pressure-related shift for thermoplastics [

55]. This leads to an overestimation of plastic flowability in common simulation tools, even when the D

3 parameter is applied [

50]. In general, the usage of the pressure parameter D

3 of the seven-parameter Cross–WLF model is recommended by the literature when the following conditions are met [

56]:

- -

The flow path length to wall thickness ratio is bigger than 100;

- -

The injection pressure exceeds 1.000 bar;

- -

The wall thickness is lower than 2 mm;

- -

Using specific materials like PC.

While the influence of the consideration of the pressure dependency with the D

3 parameter on the flow behavior of unfilled plastic has been studied in the literature [

49,

50], it has not yet been possible to investigate the influence of the pressure dependence on highly filled plastic compounds in injection molding and injection compression molding. Recent research focuses on modifying the crystal structure of PP and the following optimizing of the mechanical properties of the material [

46], while the influence of the pressure-induced crystallization and its effects on the flow behavior of highly filled plastics has not yet been the subject of research. Therefore, the aim of this study is the evaluation of the effect of pressure-dependent viscosity data on the flow behavior of highly filled plastic melts. For this purpose, experiments and simulations were conducted. Based on the material characterization of the compounded material, two Cross–WLF models were fitted. Simulations in Moldex3D were performed both with and without considering the pressure dependency of the material and were validated through experiments. Furthermore, the validated model is used to estimate the maximum achievable flow path length to wall thickness ratios for larger bipolar plates.