Viscosity-Dependent Shrinkage Behavior of Flowable Resin Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Composite Materials

2.2. Viscosity Measurements

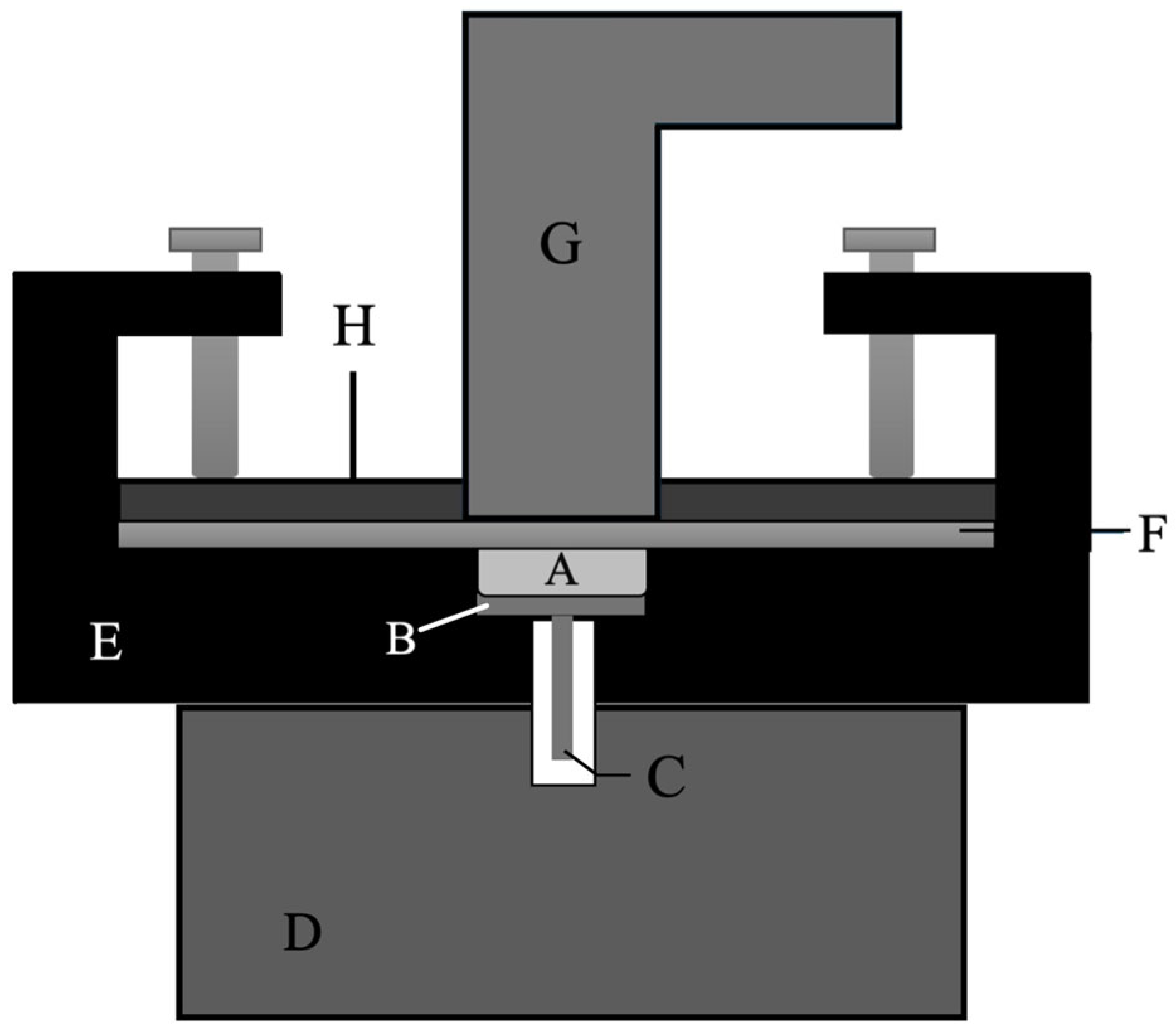

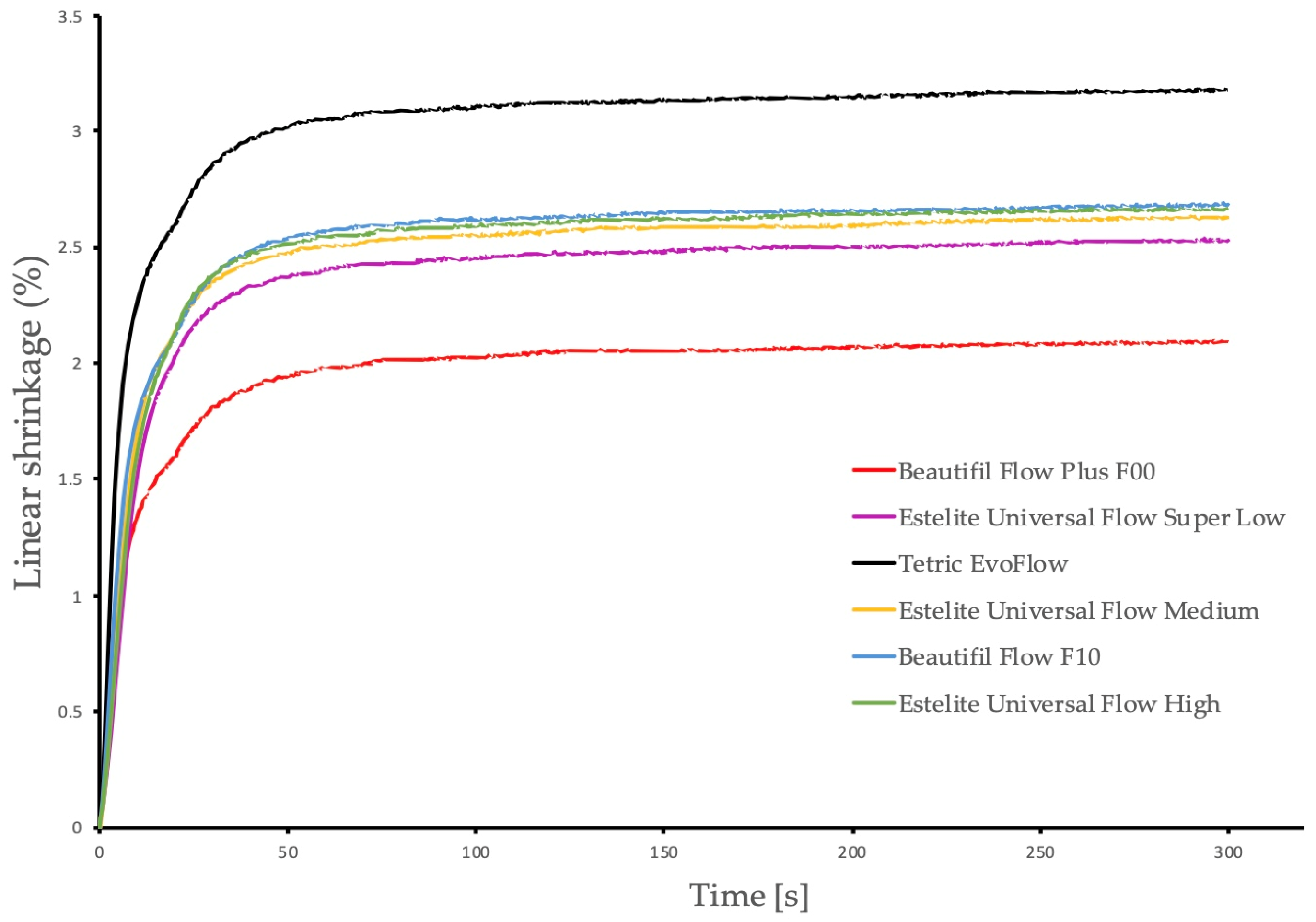

2.3. Linear Polymerization Shrinkage

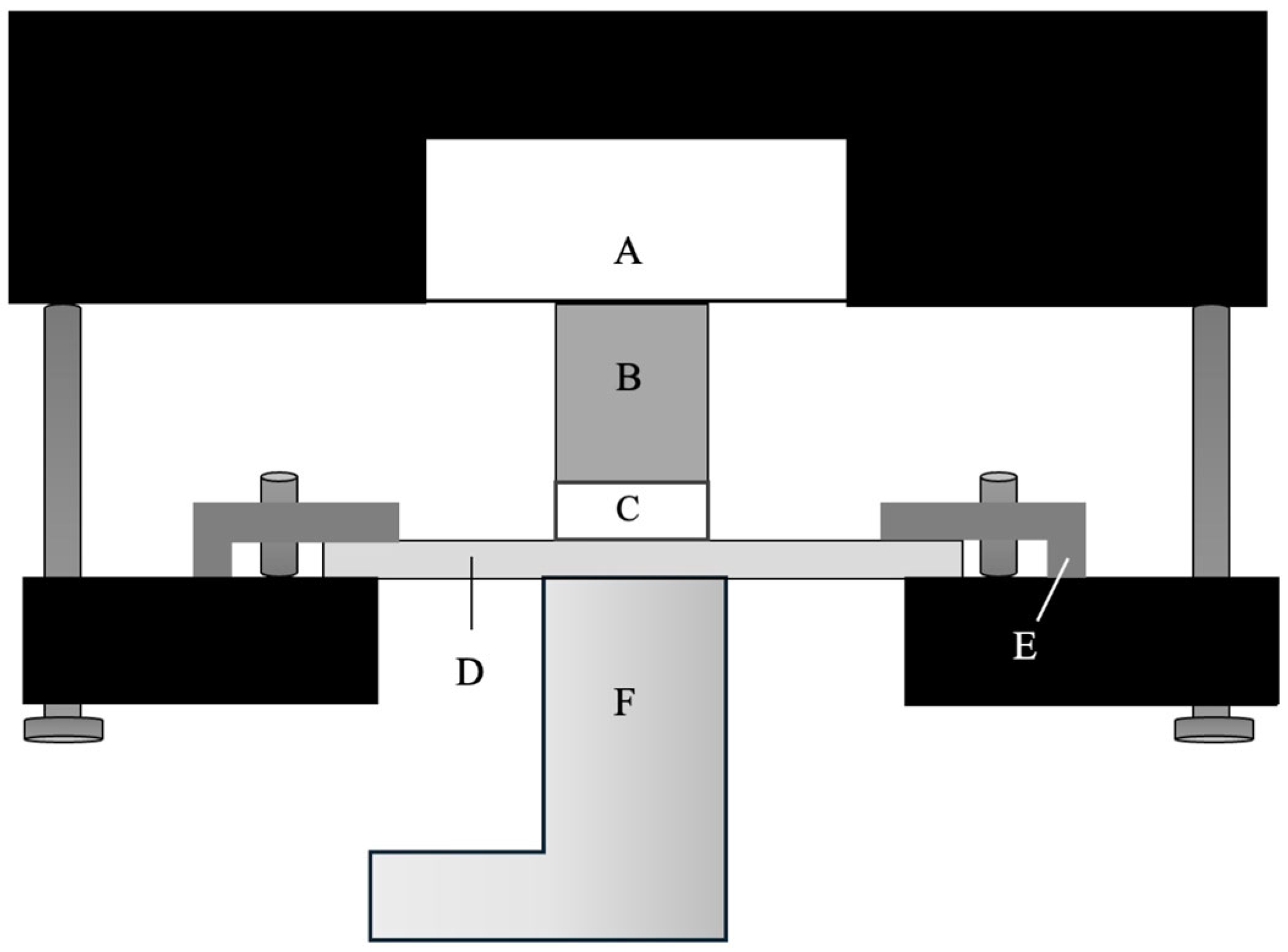

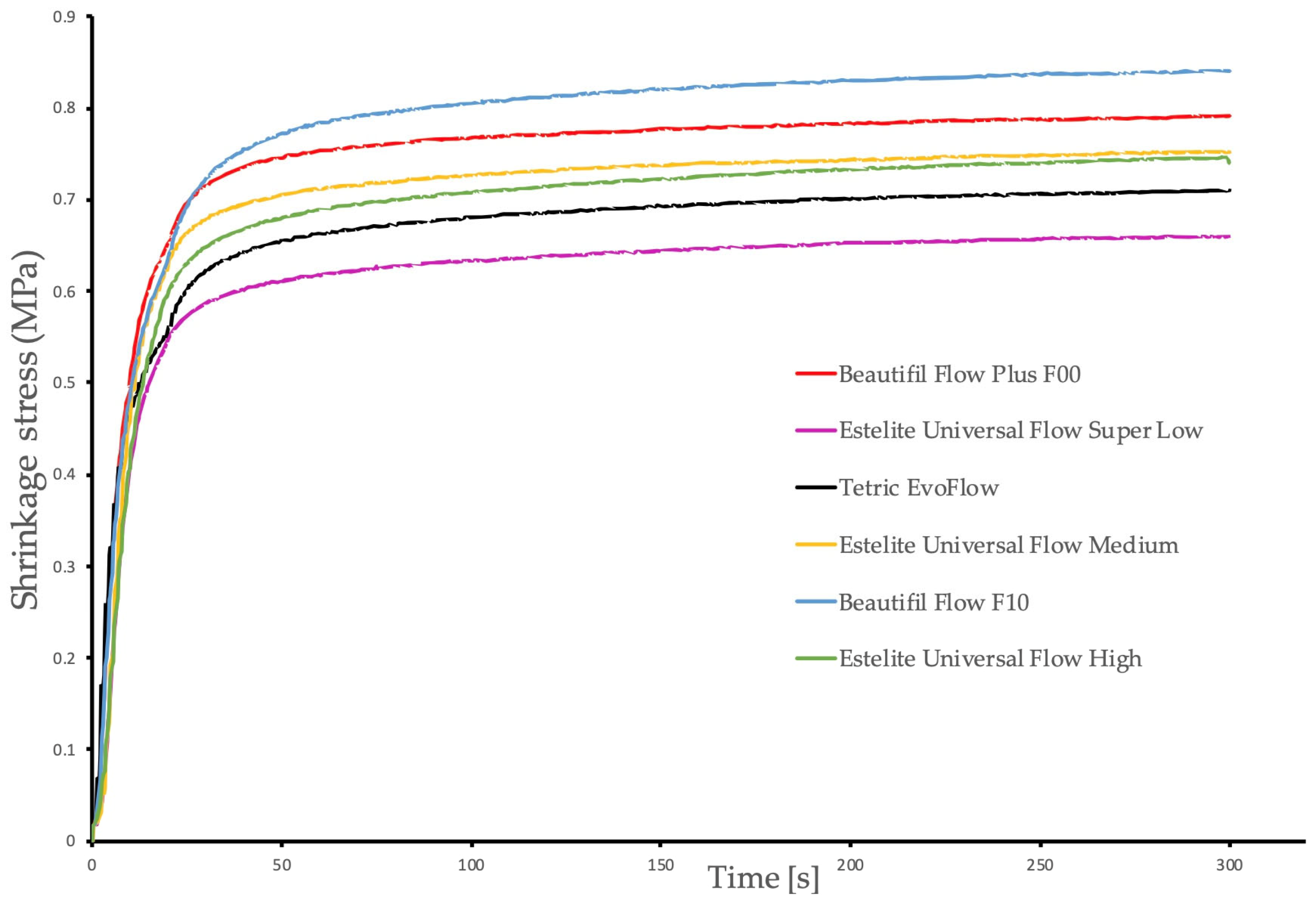

2.4. Polymerization Shrinkage Stress

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baroudi, K.; Mahmoud, S. Improving Composite Resin Performance Through Decreasing Its Viscosity by Different Methods. Open Dent. J. 2015, 9, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.D.; Pütz, N.; Michaelis, M.; Bitter, K.; Gernhardt, C.R. Influence of Cavity Lining on the 3-Year Clinical Outcome of Posterior Composite Restorations: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroudi, K.; Rodrigues, J.C. Flowable Resin Composites: A Systematic Review and Clinical Considerations. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, ZE18–ZE24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-H.; Um, C.-M.; Lee, I.-B. Rheological properties of resin composites according to variations in monomer and filler composition. Dent. Mater. 2006, 22, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitasako, Y.; Sadr, A.; Burrow, M.F.; Tagami, J. Thirty-six month clinical evaluation of a highly filled flowable composite for direct posterior restorations. Aust. Dent. J. 2016, 61, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durão, M.D.A.; de Andrade, A.K.M.; do Prado, A.M.; Veloso, S.R.M.; Maciel, L.M.T.; Montes, M.A.J.R.; Monteiro, G.Q.M. Thirty-six-month clinical evaluation of posterior high-viscosity bulk-fill resin composite restorations in a high caries incidence population: Interim results of a randomized clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021, 25, 6219–6237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauböck, T.T.; Buchalla, W.; Hiltebrand, U.; Roos, M.; Krejci, I.; Attin, T. Influence of the interaction of light- and self-polymerization on subsurface hardening of a dual-cured core build-up resin composite. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2011, 69, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rocha Gomes Torres, C.; Rêgo, H.M.C.; Perote, L.C.C.C.; Santos, L.F.T.F.; Kamozaki, M.B.B.; Gutierrez, N.C.; Di Nicoló, R.; Borges, A.B. A split-mouth randomized clinical trial of conventional and heavy flowable composites in class II restorations. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdemir, U.; Sancakli, H.S.; Yaman, B.C.; Ozel, S.; Yucel, T.; Yıldız, E. Clinical comparison of a flowable composite and fissure sealant: A 24-month split-mouth, randomized, and controlled study. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozan, G.; Sancakli, H.S.; Erdemir, U.; Yaman, B.C.; Yildiz, S.O.; Yildiz, E. Comparative evaluation of a fissure sealant and a flowable composite: A 36-month split-mouth, randomized clinical study. J. Dent. 2022, 123, 104205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Par, M.; Gubler, A.; Attin, T.; Tarle, Z.; Tarle, A.; Prskalo, K.; Tauböck, T.T. Effect of adhesive coating on calcium, phosphate, and fluoride release from experimental and commercial remineralizing dental restorative materials. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Par, M.; Gubler, A.; Attin, T.; Tarle, Z.; Tarle, A.; Tauböck, T.T. Experimental Bioactive Glass-Containing Composites and Commercial Restorative Materials: Anti-Demineralizing Protection of Dentin. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, C.; Nizami, B.; Robles, A.; Gummadi, S.; Lawson, N.C. Correlation Between Dental Composite Filler Percentage and Strength, Modulus, Shrinkage Stress, Translucency, Depth of Cure and Radiopacity. Materials 2024, 17, 3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, H.A.; Kriven, W.M.; Casanova, H. Development of mechanical properties in dental resin composite: Effect of filler size and filler aggregation state. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2019, 101, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, E.; Wang, R.; Zhu, X.X. Correlation of resin viscosity and monomer conversion to filler particle size in dental composites. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-B.; Son, H.-H.; Um, C.-M. Rheologic properties of flowable, conventional hybrid, and condensable composite resins. Dent. Mater. 2003, 19, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Par, M.; Burrer, P.; Prskalo, K.; Schmid, S.; Schubiger, A.-L.; Marovic, D.; Tarle, Z.; Attin, T.; Tauböck, T.T. Polymerization Kinetics and Development of Polymerization Shrinkage Stress in Rapid High-Intensity Light-Curing. Polymers 2022, 14, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JÄger, F.; Mohn, D.; Attin, T.; TaubÖck, T.T. Polymerization and shrinkage stress formation of experimental resin composites doped with nano- vs. micron-sized bioactive glasses. Dent. Mater. J. 2021, 40, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, L.J.D.S.; Penha, K.J.D.S.; Souza, A.F.; Lula, E.C.O.; Magalhães, F.C.; Lima, D.M.; Firoozmand, L.M. Is there correlation between polymerization shrinkage, gap formation, and void in bulk fill composites? A μCT study. Braz. Oral Res. 2017, 31, e100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Swartz, M.L.; Phillips, R.W.; Moore, B.K.; Roberts, T.A. Effect of filler content and size on properties of composites. J. Dent. Res. 1985, 64, 1396–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, F.; Kawano, Y.; Pfeifer, C.; Stansbury, J.W.; Braga, R.R. Influence of BisGMA, TEGDMA, and BisEMA contents on viscosity, conversion, and flexural strength of experimental resins and composites. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2009, 117, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.F.; Kalachandra, S.; Sankarapandian, M.; McGrath, J.E. Relationship between filler and matrix resin characteristics and the properties of uncured composite pastes. Biomaterials 1998, 19, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Fidalgo-Pereira, R.; Torres, O.; Carvalho, O.; Henriques, B.; Özcan, M.; Souza, J.C.M. The impact of inorganic fillers, organic content, and polymerization mode on the degree of conversion of monomers in resin-matrix cements for restorative dentistry: A scoping review. Clin. Oral Investig. 2024, 28, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liao, Y.; Hedin, N.E.; Fong, H. Fabrication and evaluation of Bis-GMA/TEGDMA dental resins/composites containing nano fibrillar silicate. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, L.G.; Newman, S.M.; Bowman, C.N. The effects of light intensity, temperature, and comonomer composition on the polymerization behavior of dimethacrylate dental resins. J. Dent. Res. 1999, 78, 1469–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrahlah, A.; Al-Odayni, A.-B.; Al-Mutairi, H.F.; Almousa, B.M.; Alsubaie, F.S.; Khan, R.; Saeed, W.S. A Low-Viscosity BisGMA Derivative for Resin Composites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Evaluation of Its Rheological Properties. Materials 2021, 14, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beun, S.; Bailly, C.; Devaux, J.; Leloup, G. Rheological properties of flowable resin composites and pit and fissure sealants. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 548–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.; Yap, A.U.; Wang, X.Y. Influence of Shrinkage and Viscosity of Flowable Composite Liners on Cervical Microleakage of Class II Restorations: A Micro-CT Analysis. Oper. Dent. 2018, 43, 656–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maesako, M.; Fischer, N.G.; Matsui, N.; Elgreatly, A.; Mahrous, A.; Tsujimoto, A. Comparing Polymerization Shrinkage Measurement Methods for Universal Shade Flowable Resin-Based Composites. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauböck, T.T.; Jäger, F.; Attin, T. Polymerization shrinkage and shrinkage force kinetics of high- and low-viscosity dimethacrylate- and ormocer-based bulk-fill resin composites. Odontology 2019, 107, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauböck, T.T.; Bortolotto, T.; Buchalla, W.; Attin, T.; Krejci, I. Influence of light-curing protocols on polymerization shrinkage and shrinkage force of a dual-cured core build-up resin composite. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2010, 118, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Par, M.; Mohn, D.; Attin, T.; Tarle, Z.; Tauböck, T.T. Polymerization shrinkage behaviour of resin composites functionalized with unsilanized bioactive glass fillers. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauböck, T.T.; Feilzer, A.J.; Buchalla, W.; Kleverlaan, C.J.; Krejci, I.; Attin, T. Effect of modulated photo-activation on polymerization shrinkage behavior of dental restorative resin composites. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2014, 122, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environement for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Hadley Wickham, M.A.; Bryan, J.; Chang, W.; McGowan, L.D.; François, R.; Grolemund, G.; Hayes, A.; Henry, L.; Hester, J.; Kuhn, M.; et al. Welcome to the tidyverse. J. Open Source Softw. 2019, 4, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N.; Hickel, R. Investigations on mechanical behaviour of dental composites. Clin. Oral Investig. 2009, 13, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahdal, K.; Silikas, N.; Watts, D.C. Rheological properties of resin composites according to variations in composition and temperature. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meereis, C.T.W.; Münchow, E.A.; de Oliveira da Rosa, W.L.; da Silva, A.F.; Piva, E. Polymerization shrinkage stress of resin-based dental materials: A systematic review and meta-analyses of composition strategies. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 82, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anseth, K.S.; Bowman, C.N.; Brannon-Peppas, L. Mechanical properties of hydrogels and their experimental determination. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 1647–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczesio-Wlodarczyk, A.; Polikowski, A.; Krasowski, M.; Fronczek, M.; Sokolowski, J.; Bociong, K. The Influence of Low-Molecular-Weight Monomers (TEGDMA, HDDMA, HEMA) on the Properties of Selected Matrices and Composites Based on Bis-GMA and UDMA. Materials 2022, 15, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Hwang, I.-N. Polymerization shrinkage and depth of cure of bulk-fill resin composites and highly filled flowable resin. Oper. Dent. 2015, 40, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrer, P.; Par, M.; Fürer, L.; Stübi, M.; Marovic, D.; Tarle, Z.; Attin, T.; Tauböck, T.T. Effect of polymerization mode on shrinkage kinetics and degree of conversion of dual-curing bulk-fill resin composites. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 3169–3180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Landis, F.A.; Wang, Z.; Bai, D.; Jiang, L.; Chiang, M.Y.M. Polymerization stress evolution of a bulk-fill flowable composite under different compliances. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 578–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chiang, M.Y.M. System compliance dictates the effect of composite filler content on polymerization shrinkage stress. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.-H.; Ferracane, J.; Lee, I.-B. Effect of shrinkage strain, modulus, and instrument compliance on polymerization shrinkage stress of light-cured composites during the initial curing stage. Dent. Mater. 2010, 26, 1024–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Stansbury, J.W.; Dickens, S.H.; Eichmiller, F.C.; Bowman, C.N. Probing the origins and control of shrinkage stress in dental resin-composites: I. Shrinkage stress characterization technique. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2004, 15, 1097–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbishari, H.; Satterthwaite, J.; Silikas, N. Effect of filler size and temperature on packing stress and viscosity of resin-composites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 5330–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stansbury, J.W. Dimethacrylate network formation and polymer property evolution as determined by the selection of monomers and curing conditions. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellakwa, A.; Cho, N.; Lee, I.B. The effect of resin matrix composition on the polymerization shrinkage and rheological properties of experimental dental composites. Dent. Mater. 2007, 23, 1229–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, H.N.; Hefnawy, S.M.; Nagi, S.M. Degree of Conversion and Polymerization Shrinkage of Low Shrinkage Bulk-Fill Resin Composites. Contemp. Clin. Dent. 2019, 10, 465–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetric EvoCeram. Direct Composite Technology Has Evolved. 2011. Available online: https://www.ivoclar.com/medias/sys_master/celum-connect2-assets/celum-connect2-assets/h84/h33/10453523333150/Tetric-EvoCeram-scientific-documentation-en.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Satterthwaite, J.D.; Maisuria, A.; Vogel, K.; Watts, D.C. Effect of resin-composite filler particle size and shape on shrinkage-stress. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 609–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, H.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, W.; Su, B.; Li, S. The Development of Filler Morphology in Dental Resin Composites: A Review. Materials 2021, 14, 5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Material | Composition | Filler Size (μm) | Filler Content (wt%/vol%) | Lot No./Shade | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beautifil Flow Plus F00 | Matrix: Bis-GMA 1, TEGDMA 2, CQ 3 Filler: AFS-glass 4, SiO2 5, Al2O3 6, colorant | 1–3 | 67/47 | 062331/A2 | Shofu, Kyoto, Japan |

| Estelite Universal Flow SuperLow | Matrix: POE 7, Bis-MPEPP 8, EDBO 9, UVP 10 Filler: spherical SiO2, TiO2 11 ZrO2 12 nanoparticles | mean: 0.2 | 70/56 | 073E33/A2 | Tokuyama, Tokyo, Japan |

| Tetric EvoFlow | Matrix: Bis-GMA, UDMA 13, D3DMA 14, TPO 15, CQ, EDAB 16 Filler: YbF3 17, barium glass, ZrO2-SiO2 mixed oxide, prepolymerized filler particles | 0.1–15.5 | 68/46 | Z06F2Z/A2 | Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein |

| Estelite Universal Flow Medium | Matrix: POE, Bis-MPEPP, EDBO, UVP Filler: spherical SiO2, TiO2 ZrO2 nanoparticles | mean: 0.2 | 71/57 | 101E73/A2 | Tokuyama, Tokyo, Japan |

| Beautifil Flow F10 | Matrix: Bis-GMA, TEGDMA, CQ Filler: AFS-glass, Al2O3, SiO2, colorants | mean: 0.8 | 53/33 | 062392/A2 | Shofu, Kyoto, Japan |

| Estelite Universal Flow High | Matrix: POE, Bis-MPEPP, EDBO, UVP Filler: spherical SiO2, TiO2 ZrO2 nanoparticles | mean: 0.2 | 69/55 | 079EZ3/A2 | Tokuyama, Tokyo, Japan |

| Manufacturer Classification | Material | Linear Shrinkage (%) | Shrinkage Stress (MPa) | Viscosity at Shear Rate of 10 s−1 (Pa·s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-flow | Beautifil Flow Plus F00 | 1.89 (0.13) C | 0.75 (0.12) AB | 37.87 (1.70) D |

| Low-flow | Estelite Universal Flow SuperLow | 2.53 (0.20) B | 0.65 (0.10) B | 60.23 (1.60) B |

| Medium-flow | Tetric EvoFlow | 3.18 (0.21) A | 0.70 (0.08) AB | 67.17 (2.55) A |

| Medium-flow | Estelite Universal Flow Medium | 2.63 (0.14) B | 0.73 (0.09) AB | 48.00 (0.70) C |

| High-flow | Beautifil Flow F10 | 2.68 (0.21) B | 0.83 (0.14) A | 14.60 (0.17) F |

| High-flow | Estelite Universal Flow High | 2.67 (0.19) B | 0.80 (0.09) AB | 28.10 (0.27) E |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeconias, N.; Fischer, P.; Tauböck, T.T. Viscosity-Dependent Shrinkage Behavior of Flowable Resin Composites. Polymers 2025, 17, 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243292

Jeconias N, Fischer P, Tauböck TT. Viscosity-Dependent Shrinkage Behavior of Flowable Resin Composites. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243292

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeconias, Nadja, Peter Fischer, and Tobias T. Tauböck. 2025. "Viscosity-Dependent Shrinkage Behavior of Flowable Resin Composites" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243292

APA StyleJeconias, N., Fischer, P., & Tauböck, T. T. (2025). Viscosity-Dependent Shrinkage Behavior of Flowable Resin Composites. Polymers, 17(24), 3292. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243292