Optimization of Composite Formulation Using Recycled Polyethylene for Rotational Molding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

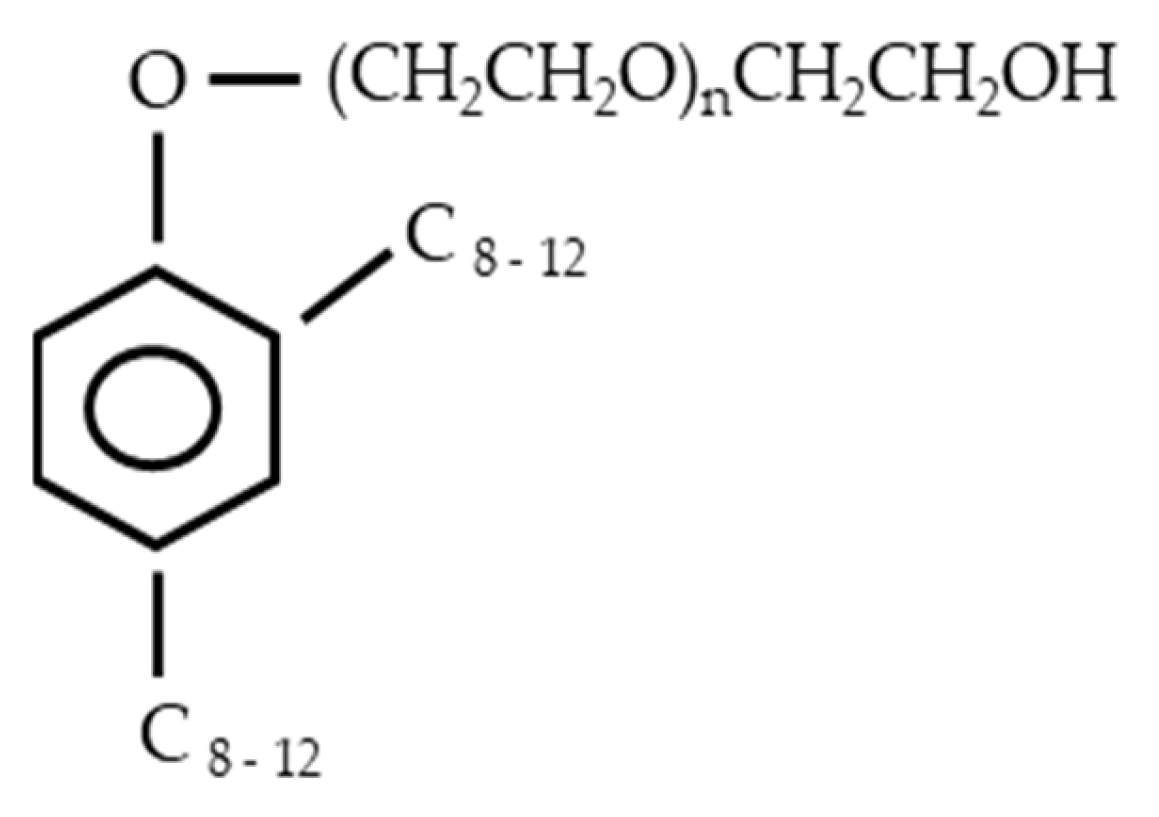

2.1. Materials

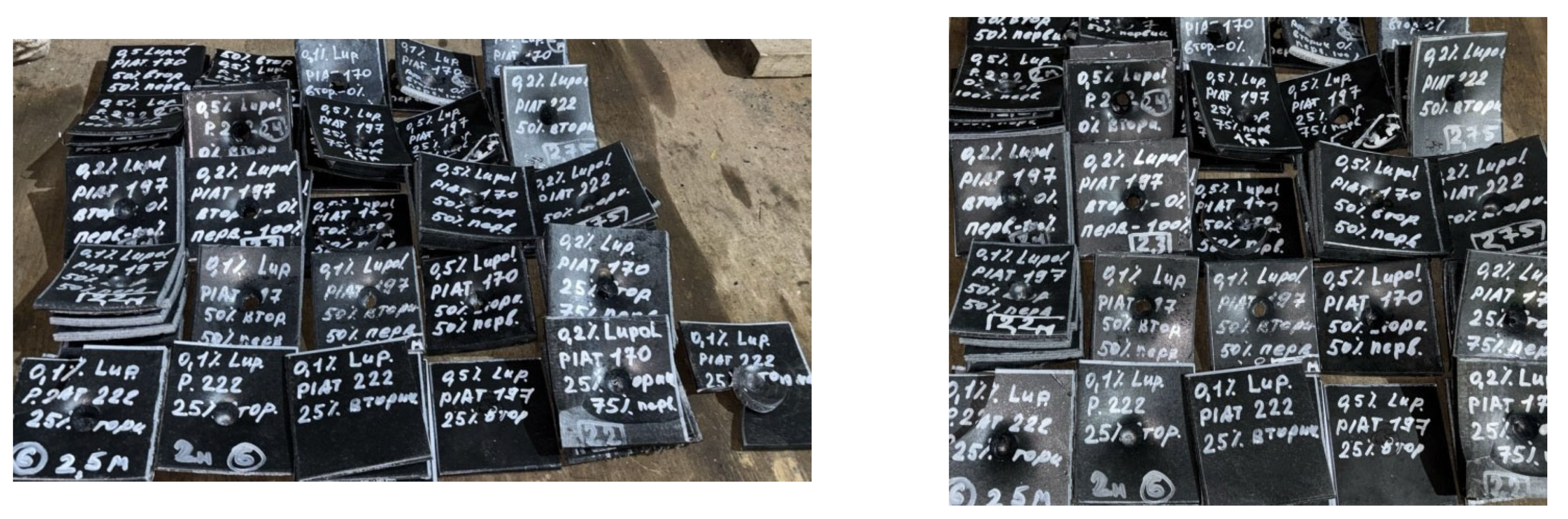

2.2. Samples Preparation

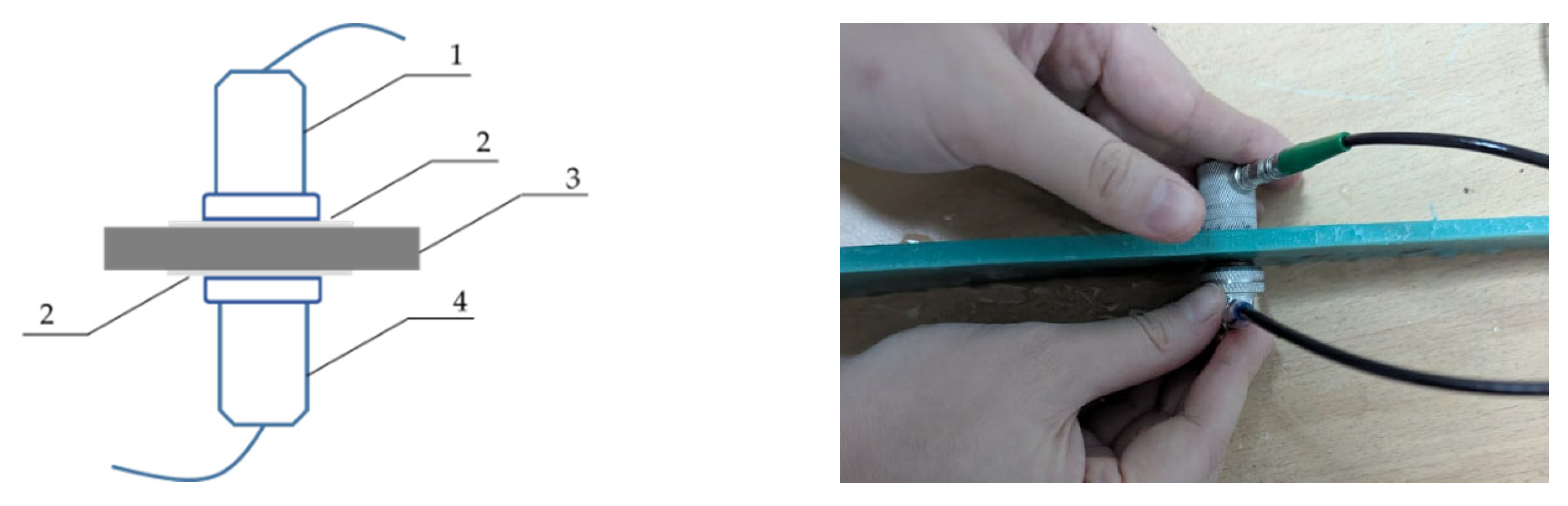

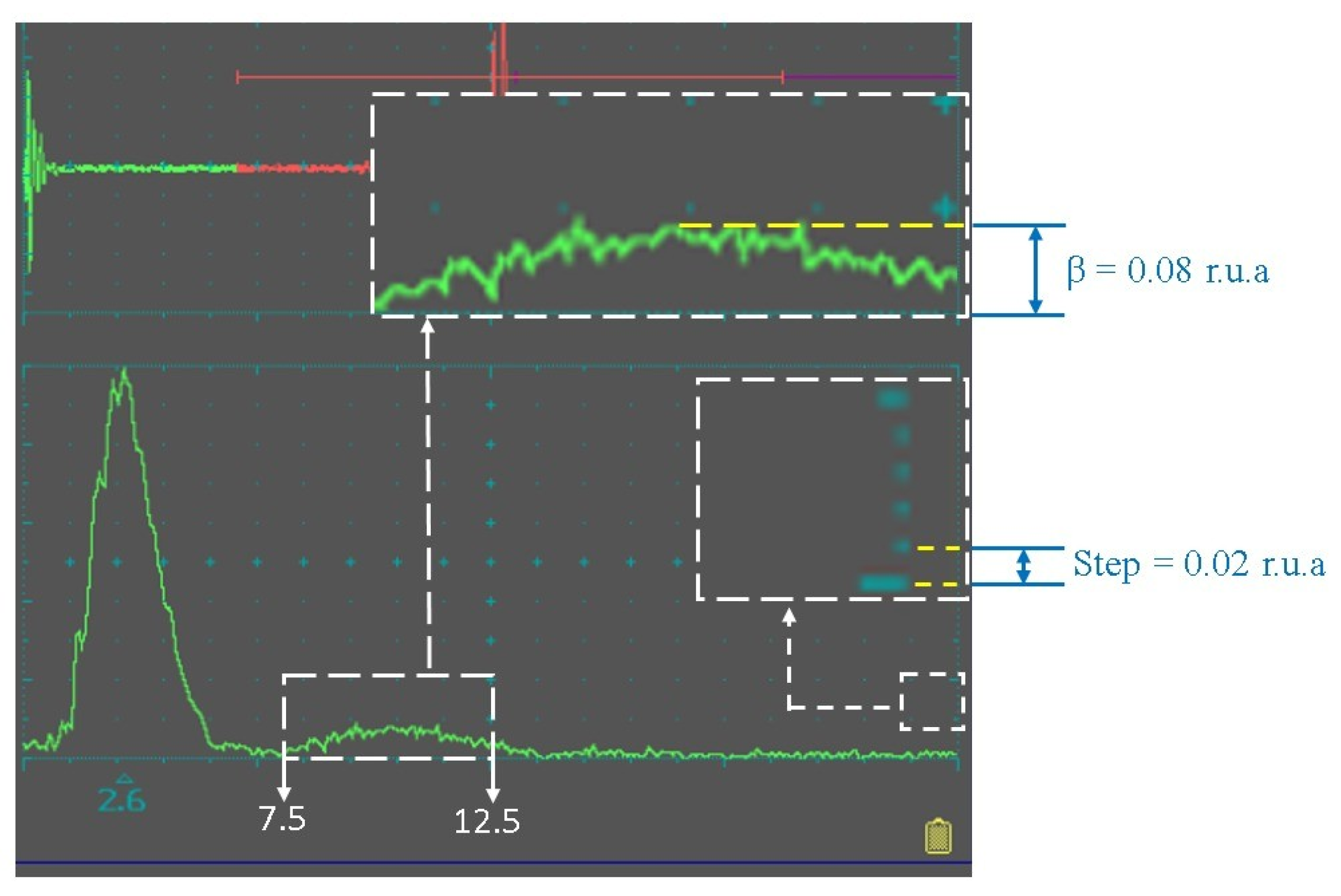

2.3. Ultrasonic Testing Method

2.4. Mechanical Testing Method

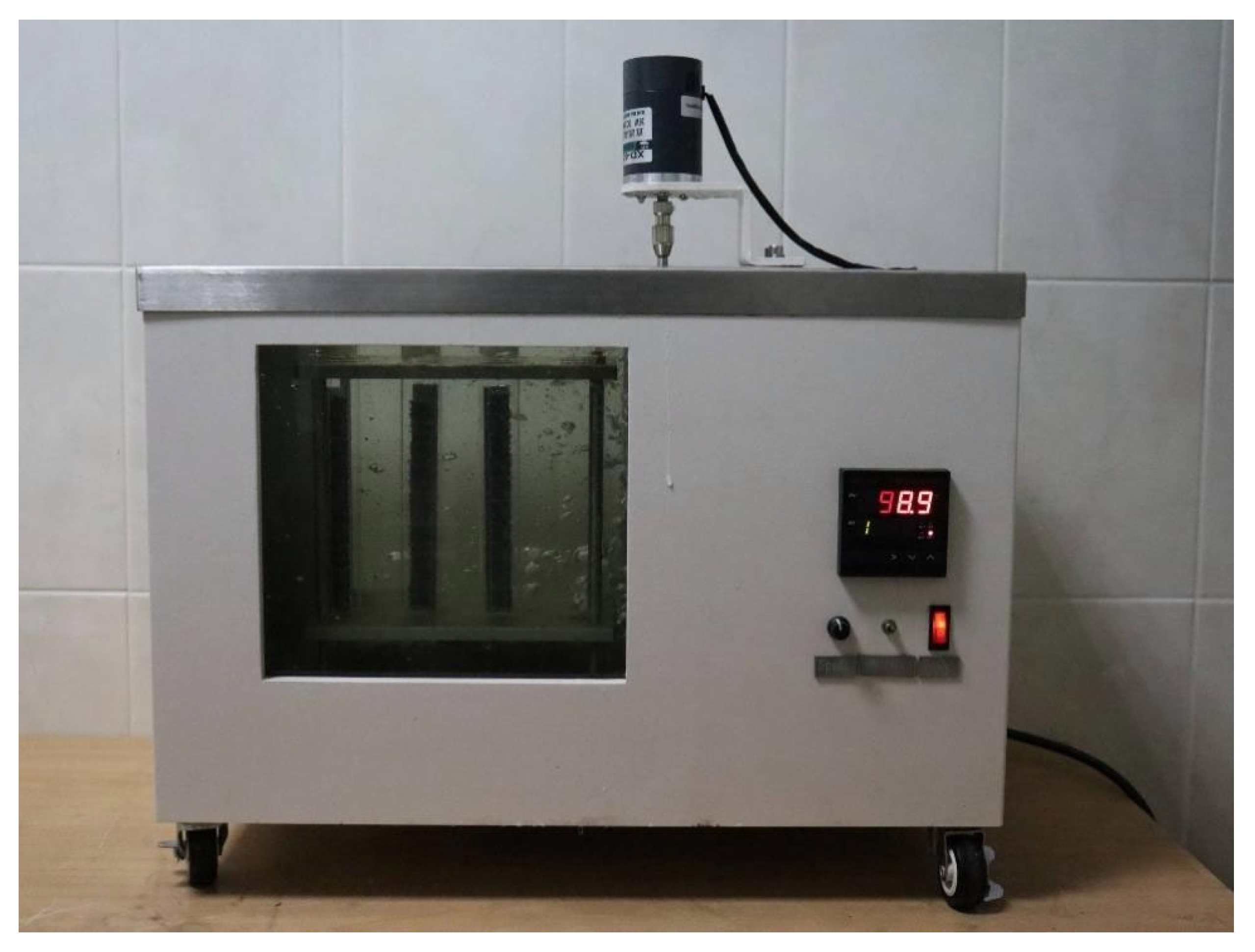

2.5. ESCR Test Method

2.6. Contact Angle Measurement Method

2.7. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Method

2.8. Method of Thermal Analysis

2.9. Experimental Design

Planning an Experiment for Modeling

- Input factors and their levels were defined as follows:

- -

- rPE content: 0%, 25%, 50%;

- -

- Pigment (Cp) content: 0.1%, 0.2%, 0.5%;

- -

- PIAT: 170 °C, 197 °C, 222 °C.

- Next, an orthogonal plan of a three-factor experiment at three levels was developed. Table 1 presents this orthogonal plan and the results of the experimental determination of the mechanical and thermal properties of the composites, the ultrasonic signal amplitude (β), MFEsp., contact angle, and ESCR.

3. Results

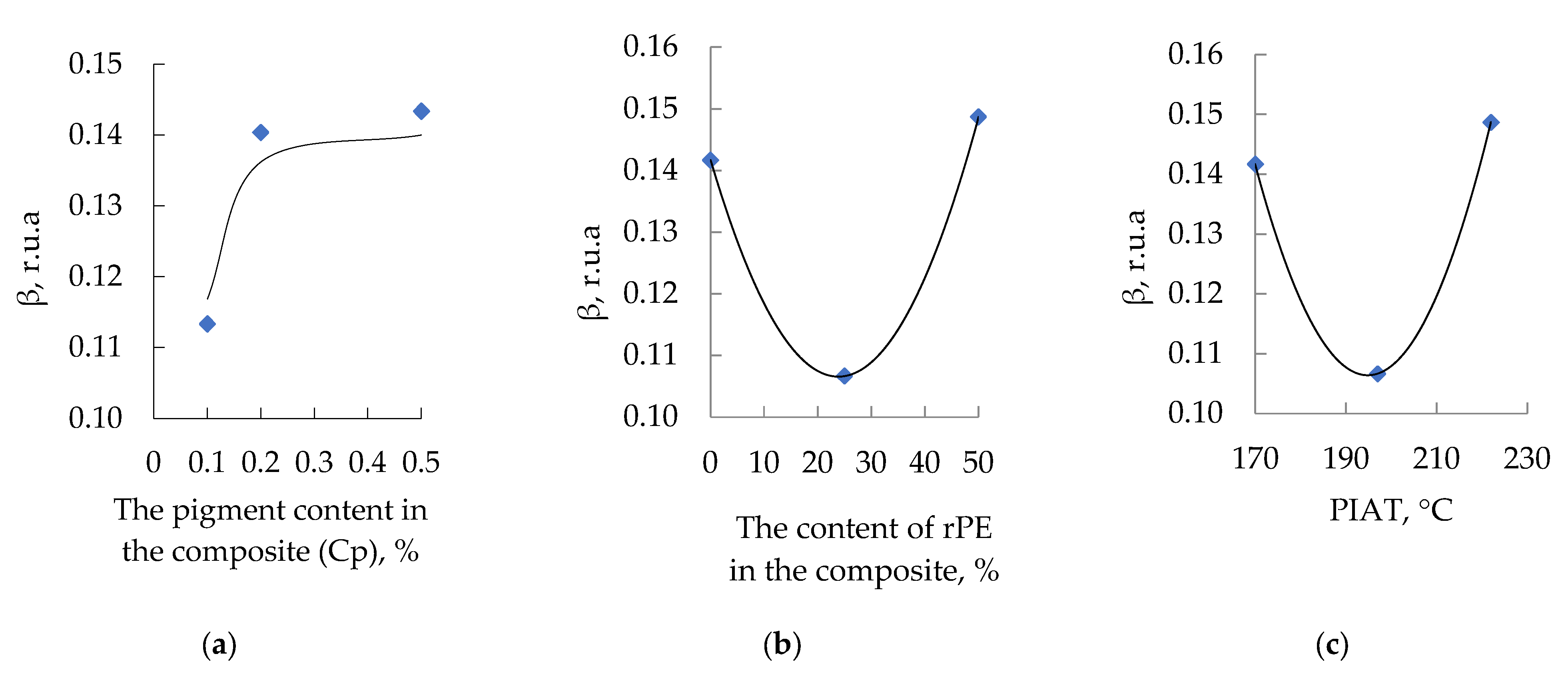

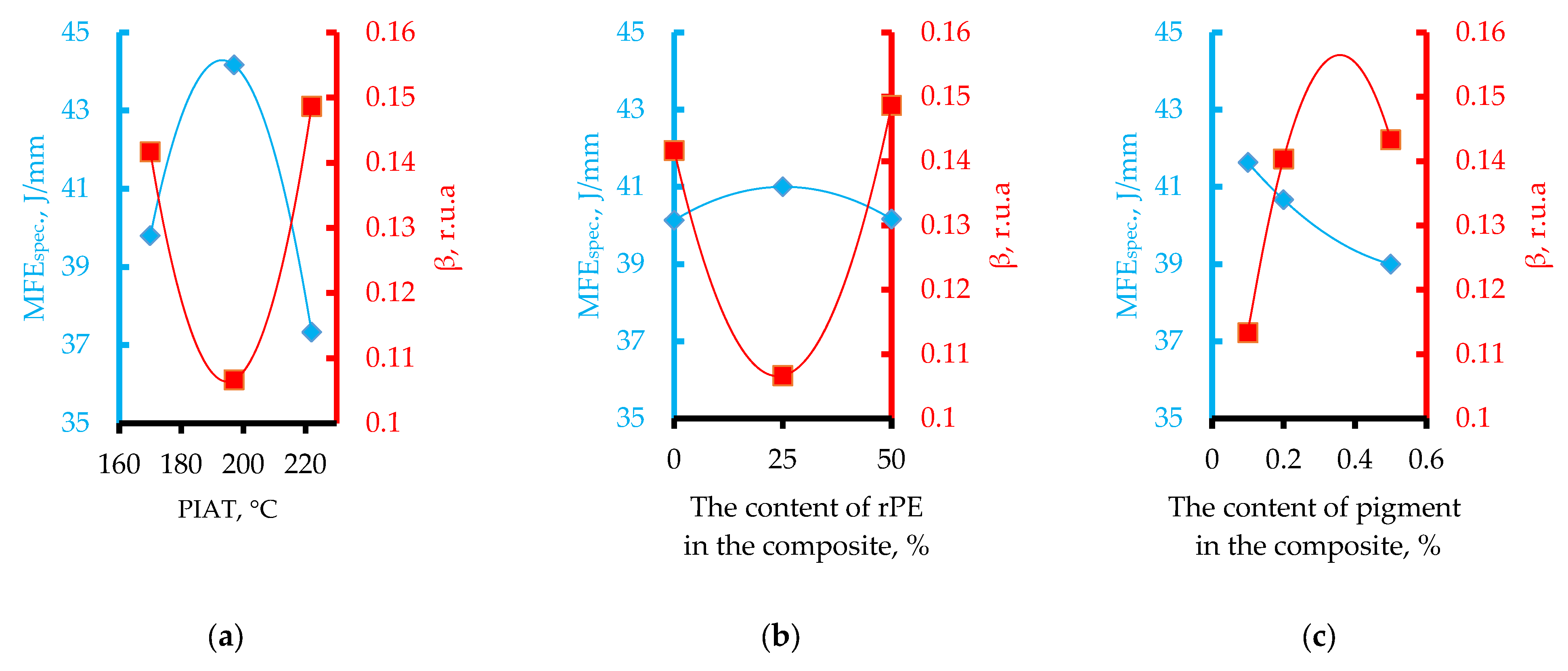

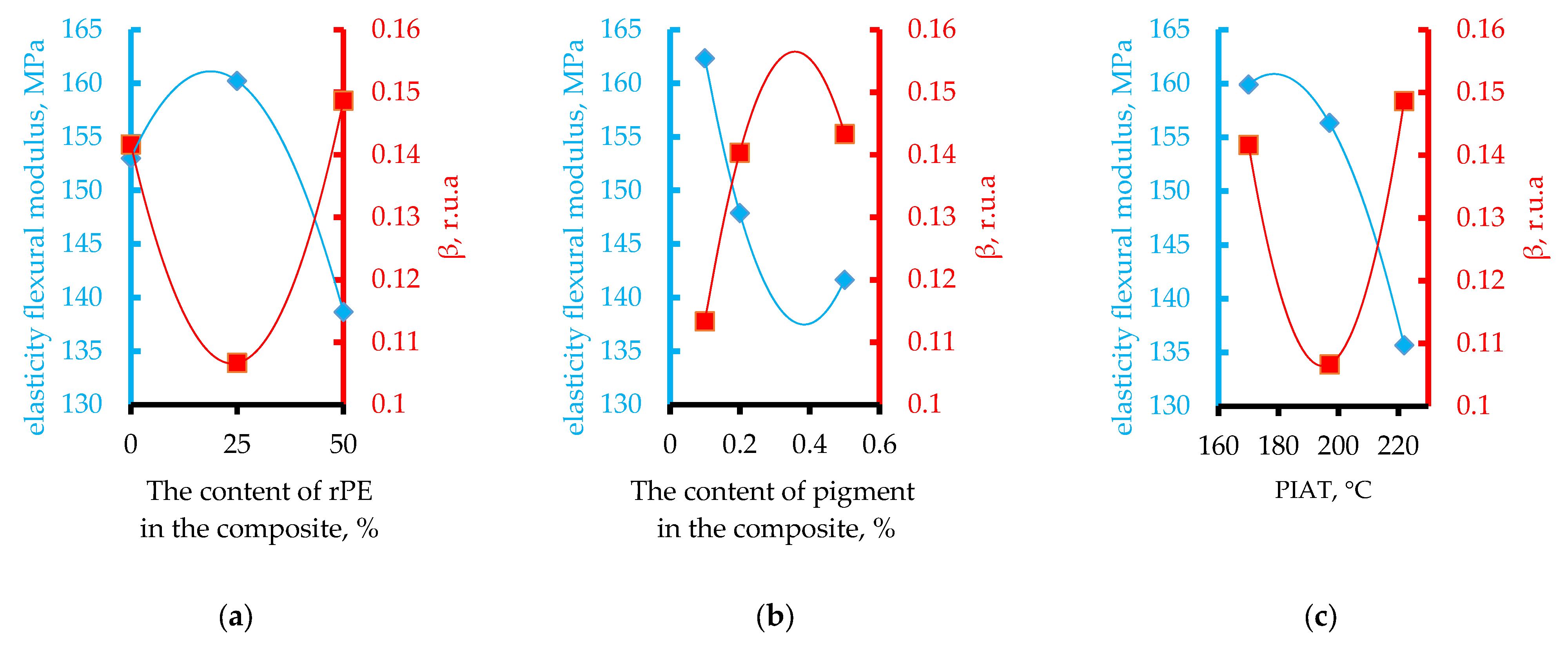

3.1. The Influence of Optimization Parameters (rPE, Cp, and PIAT) on the Amplitude of the Ultrasonic Third Harmonic β (r.u.a.)

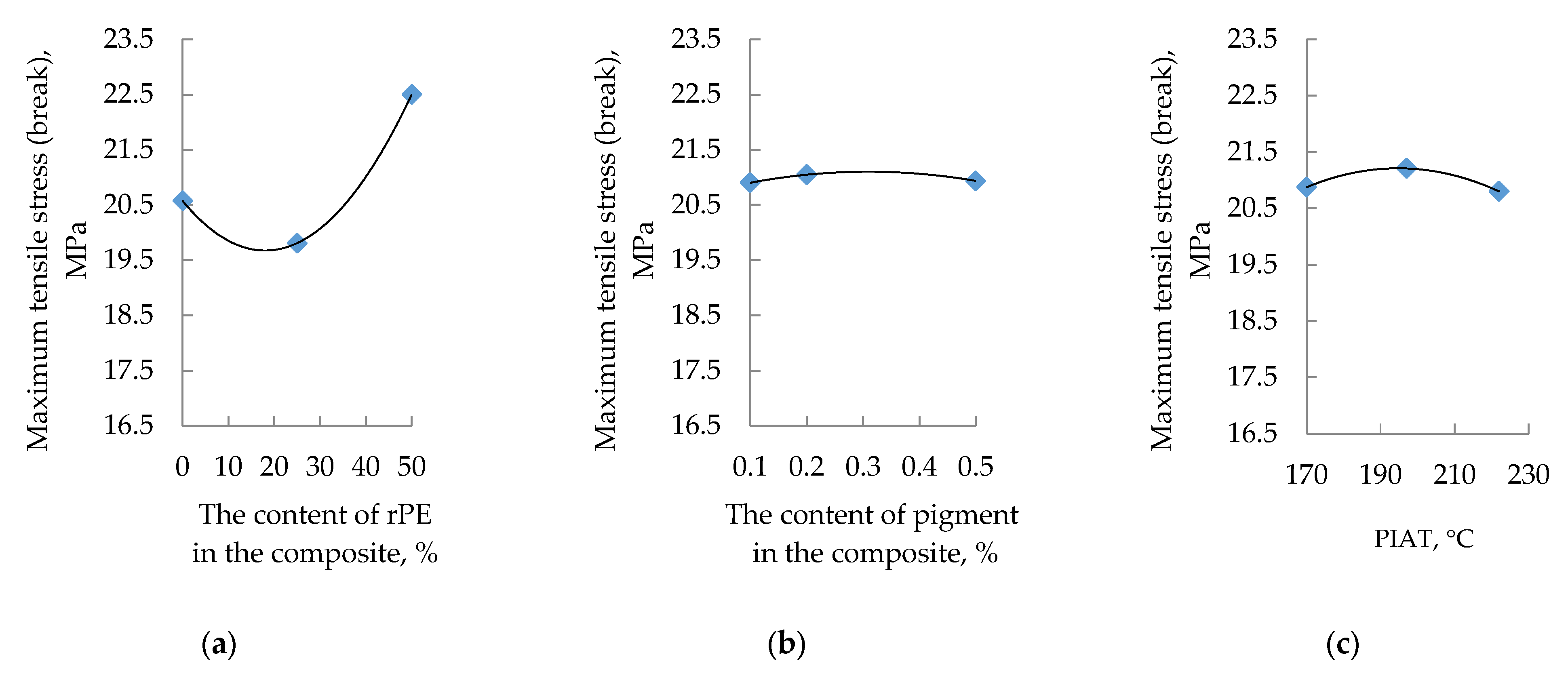

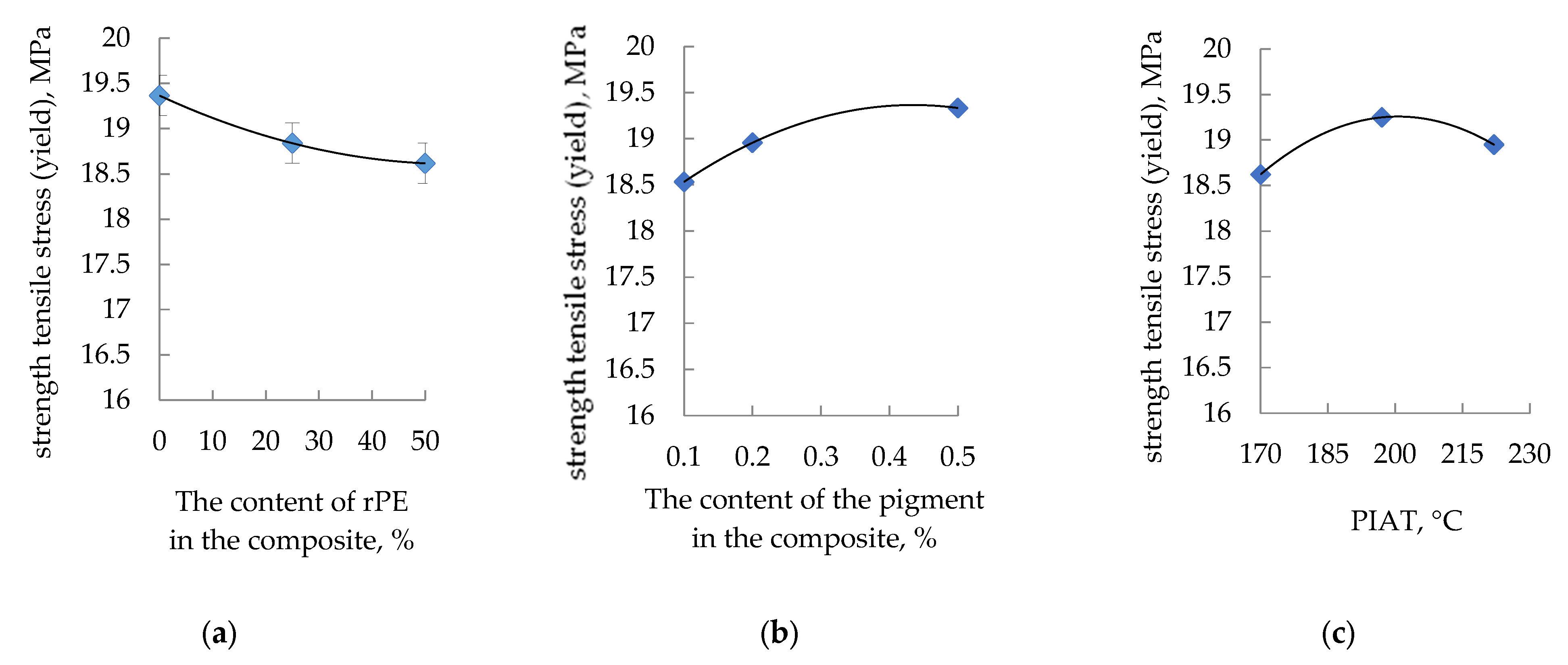

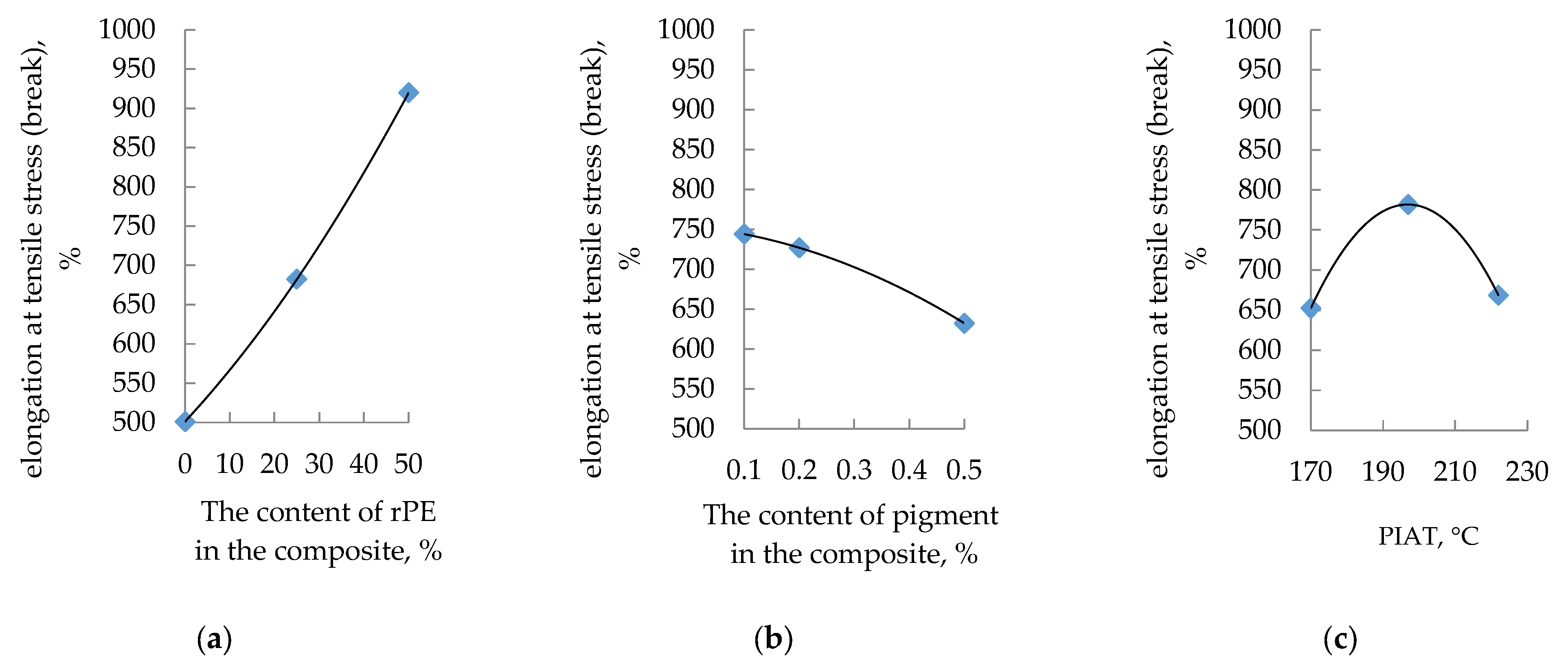

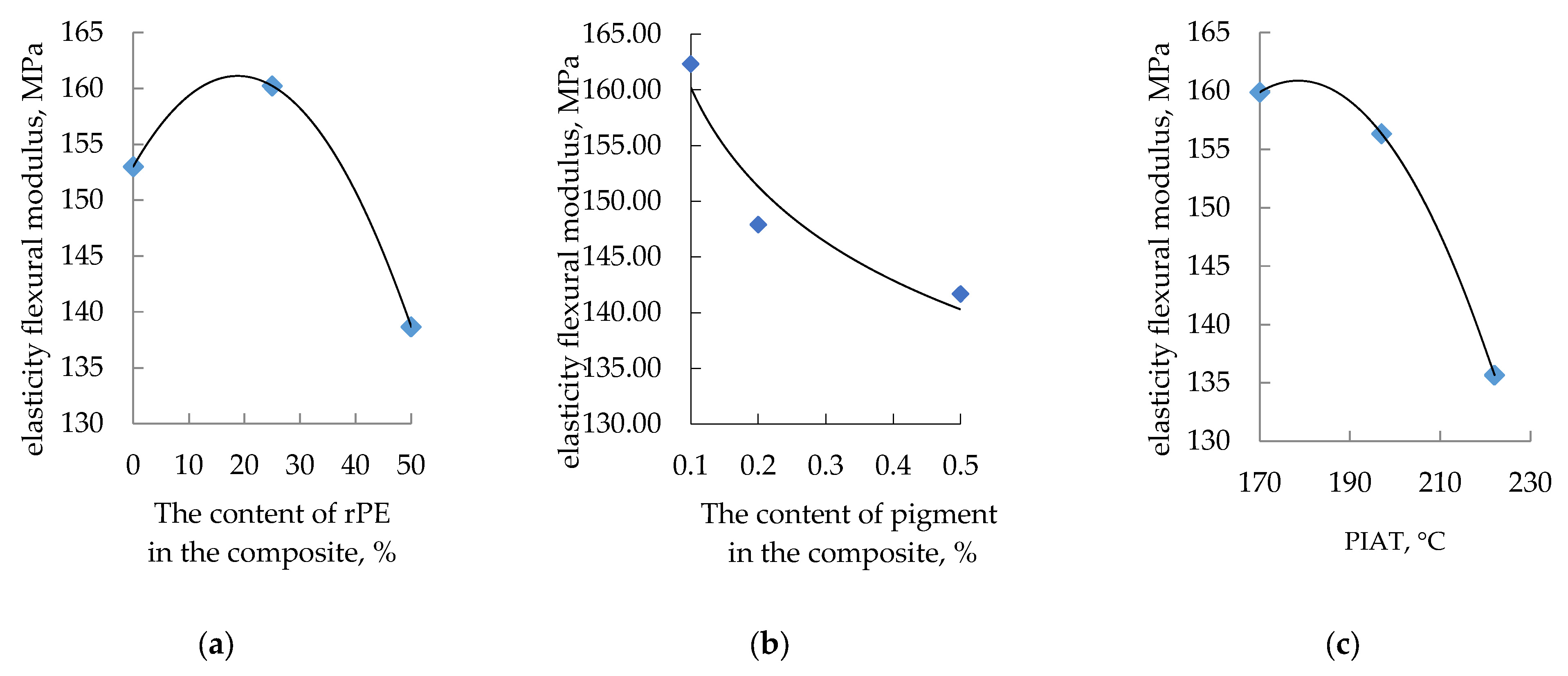

3.2. The Influence of Optimization Parameters (rPE, Cp, and PIAT) on the Mechanical Properties of the Composites

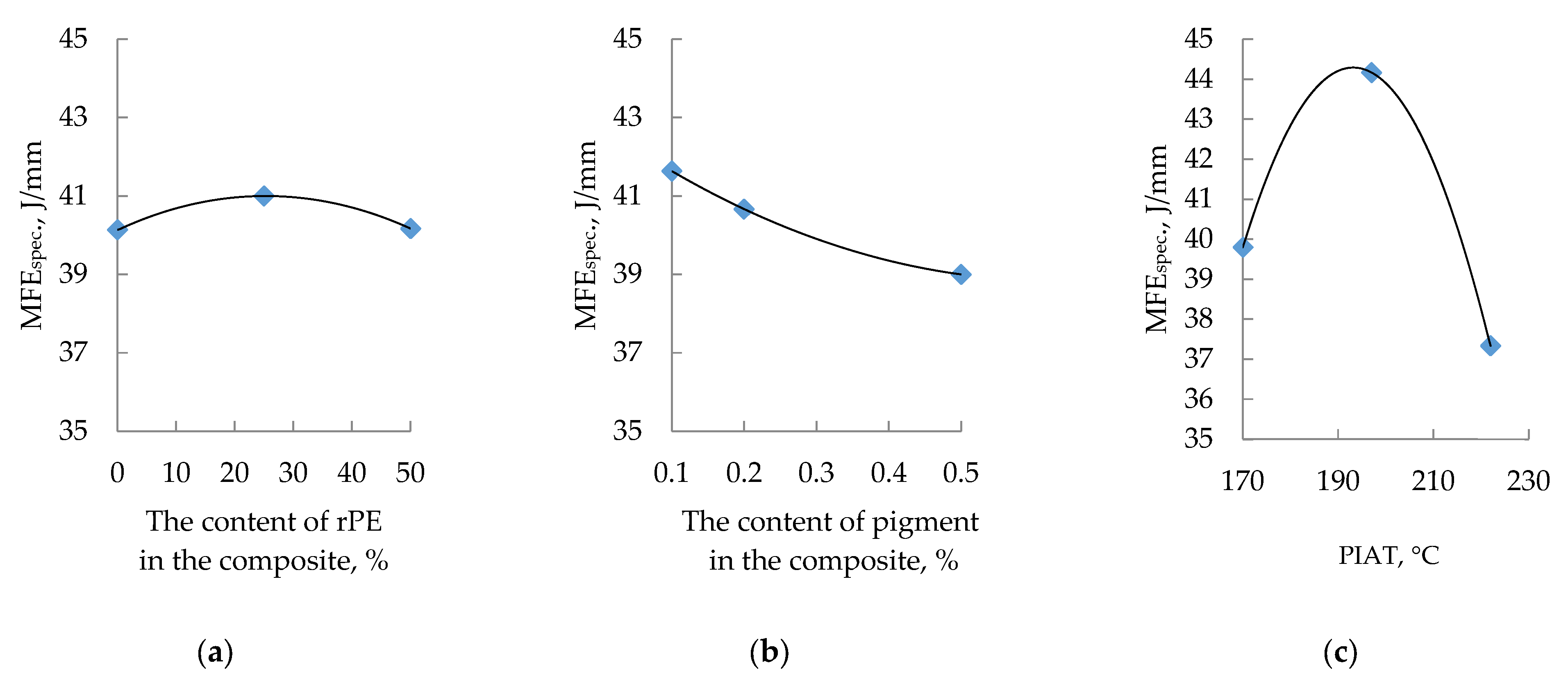

3.3. The Influence of Optimization Parameters (rPE, Cp, and PIAT) on the Impact Strength of the Composites

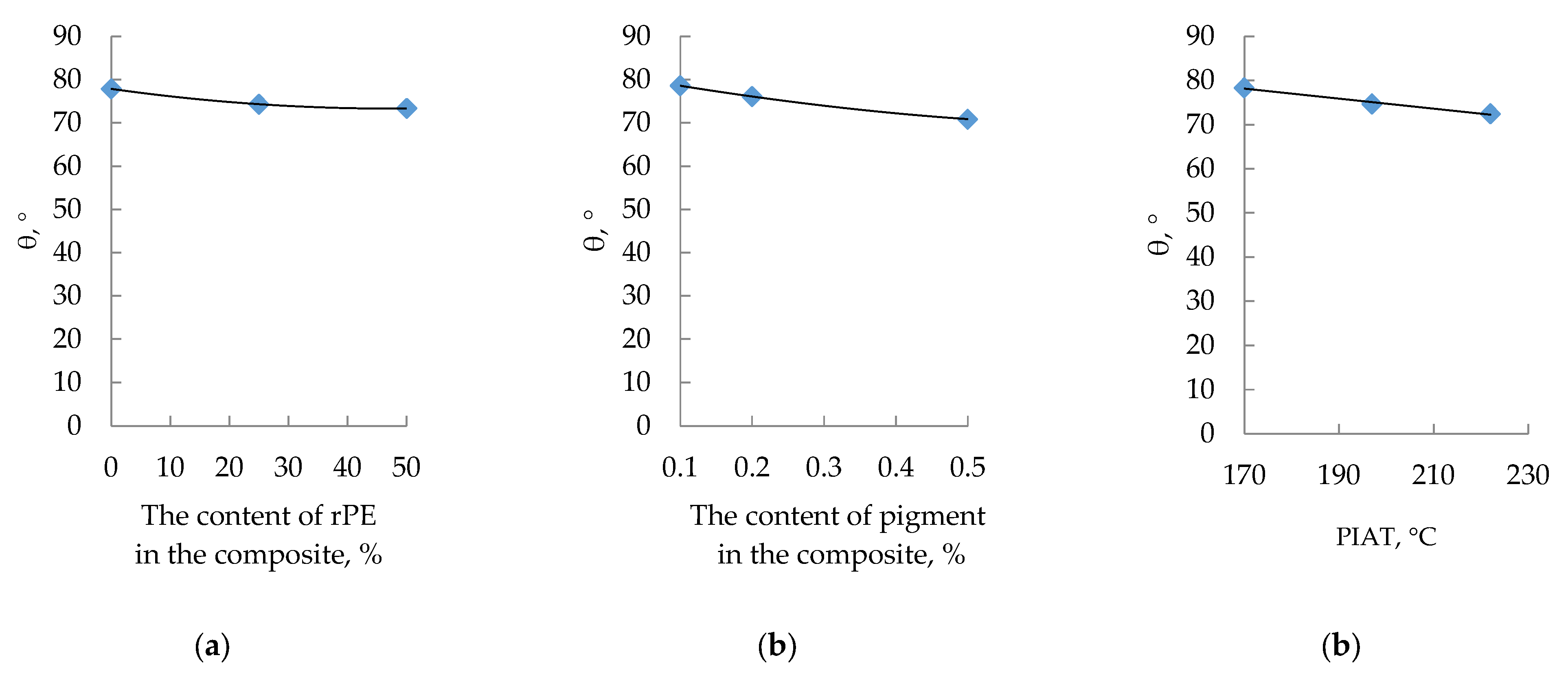

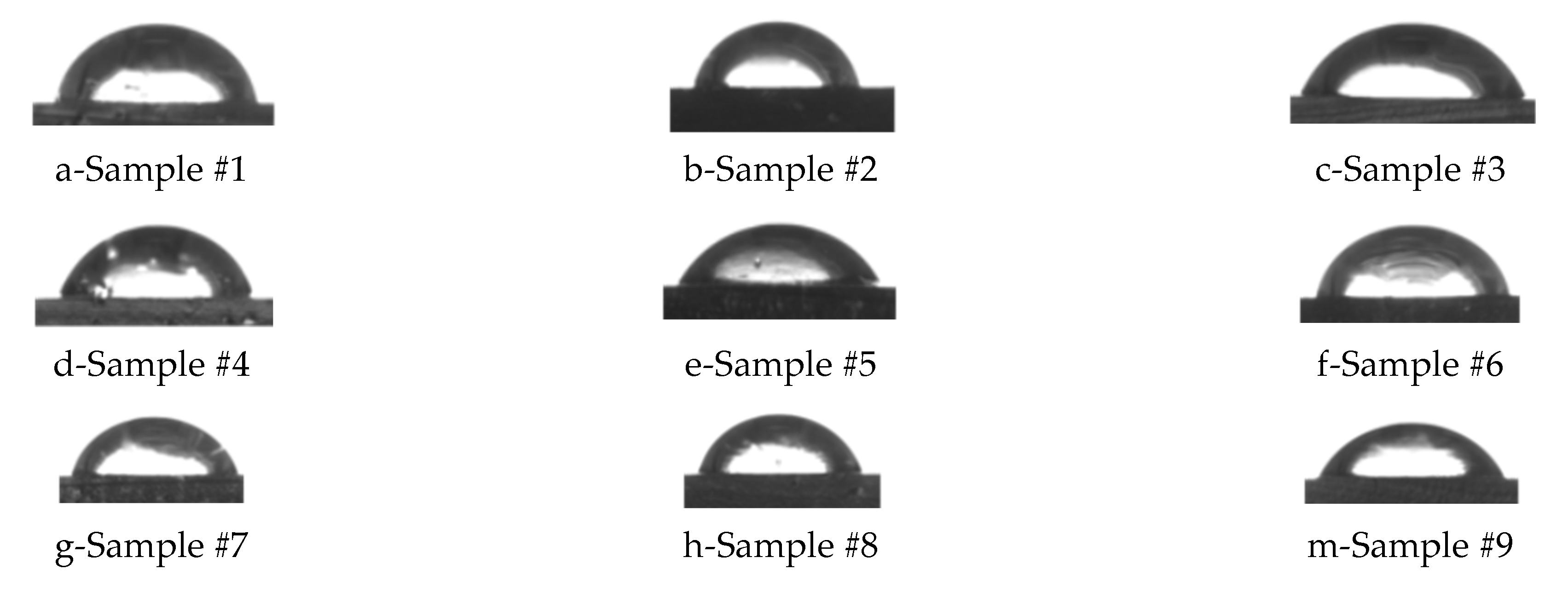

3.4. The Influence of Optimization Parameters (rPE, Cp, and PIAT) on the Wettability of the Composites (Contact Angle θ)

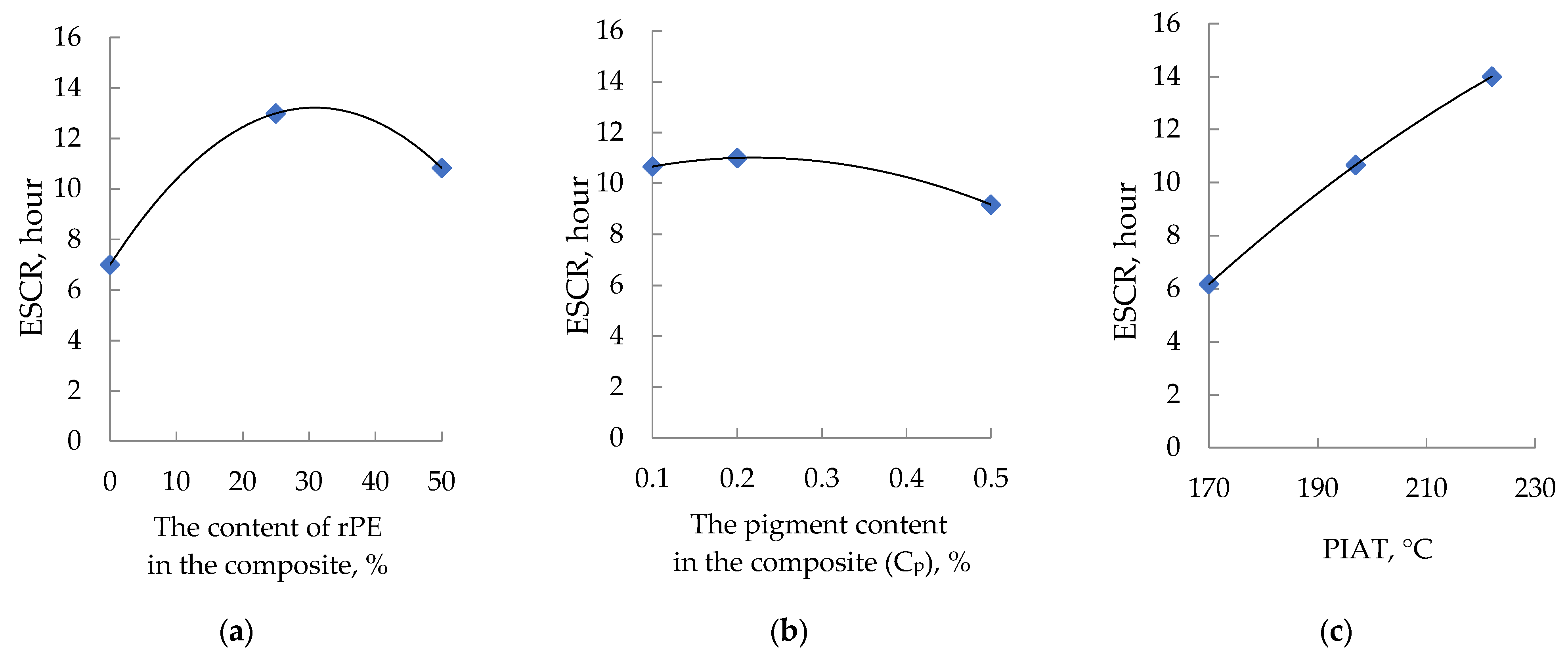

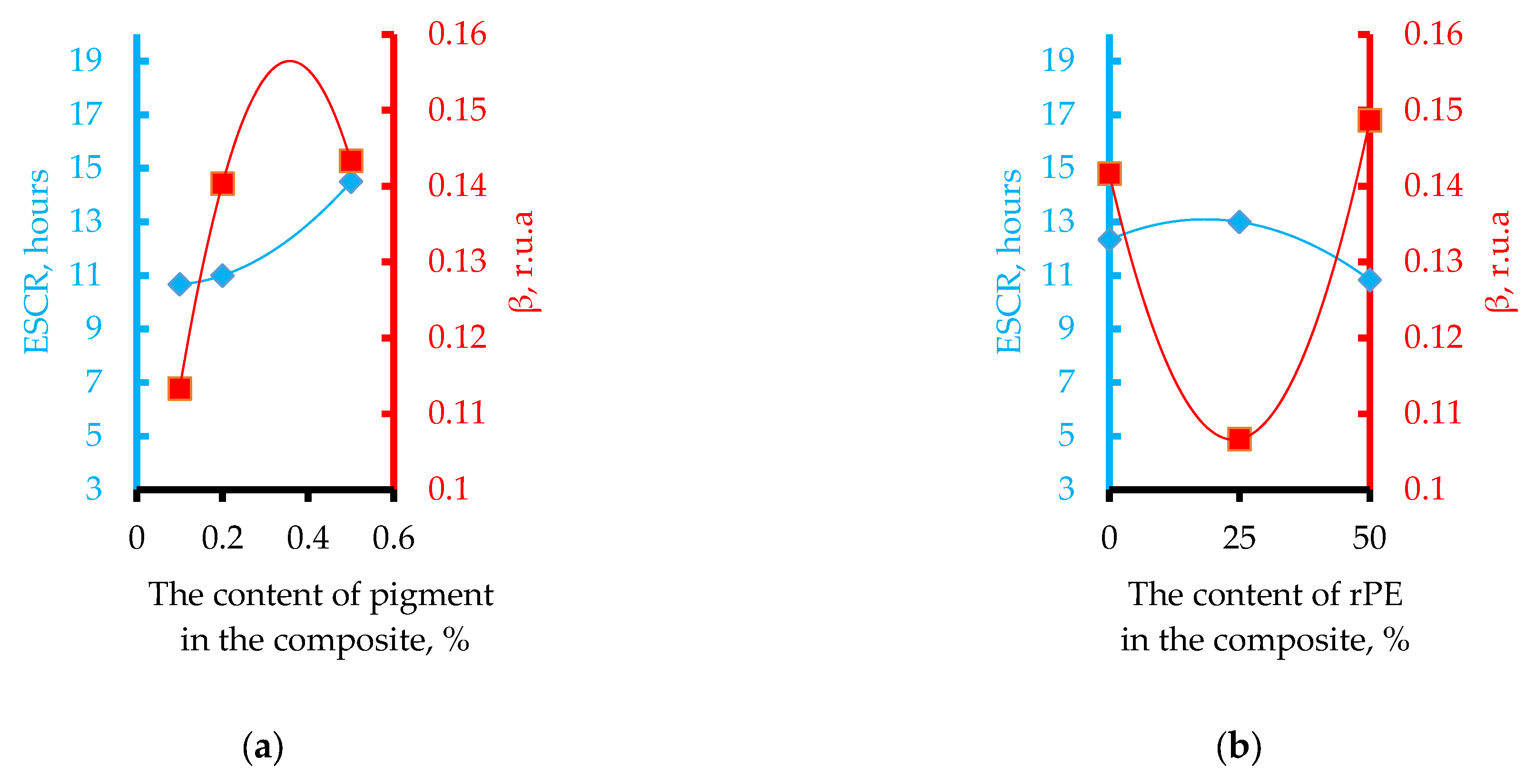

3.5. The Influence of Optimization Parameters (rPE, Cp, and PIAT) on the ESCR of the Composites

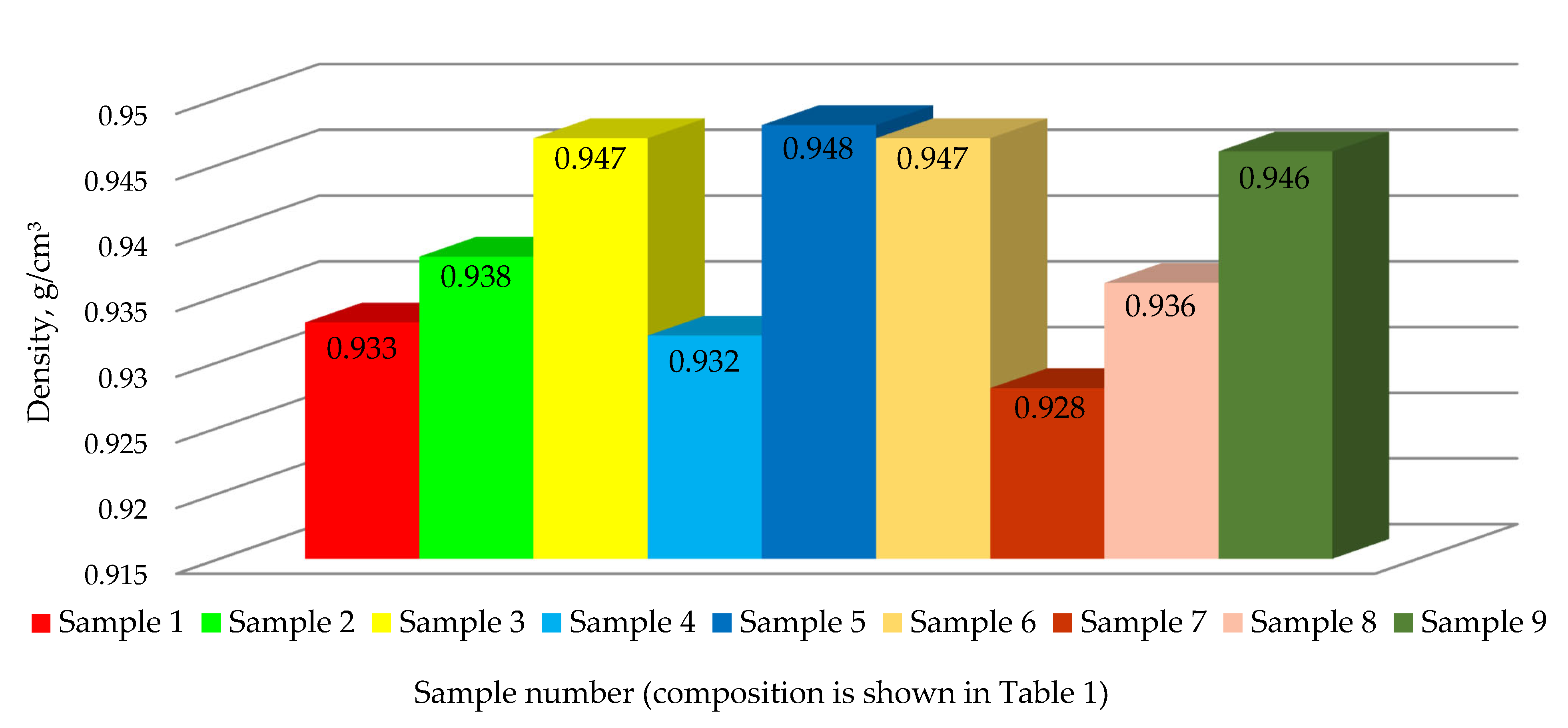

3.6. The Influence of Optimization Parameters (rPE, Cp, and PIAT) on the Density of the Samples

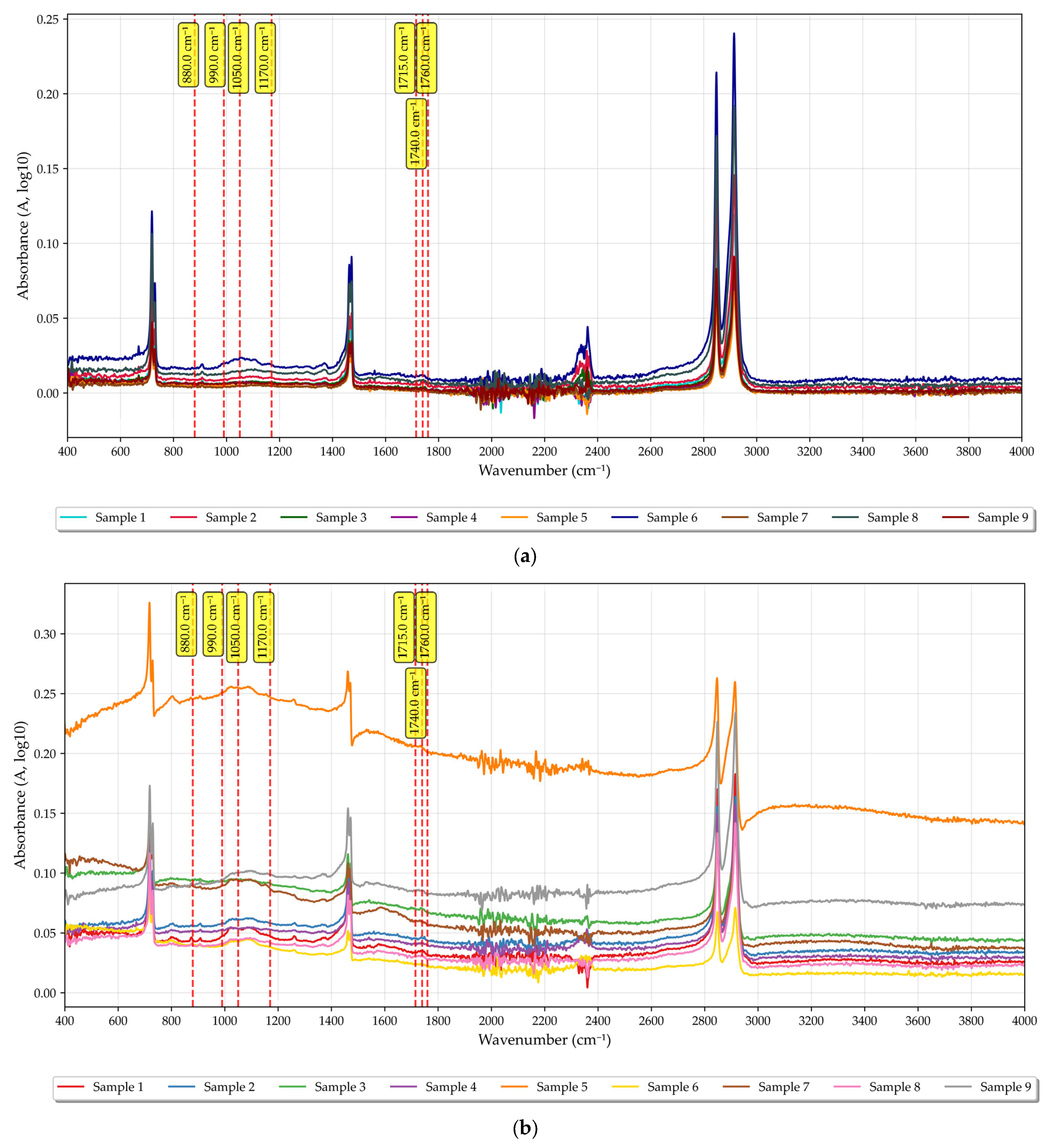

3.7. IR Spectroscopy of the Obtained Samples

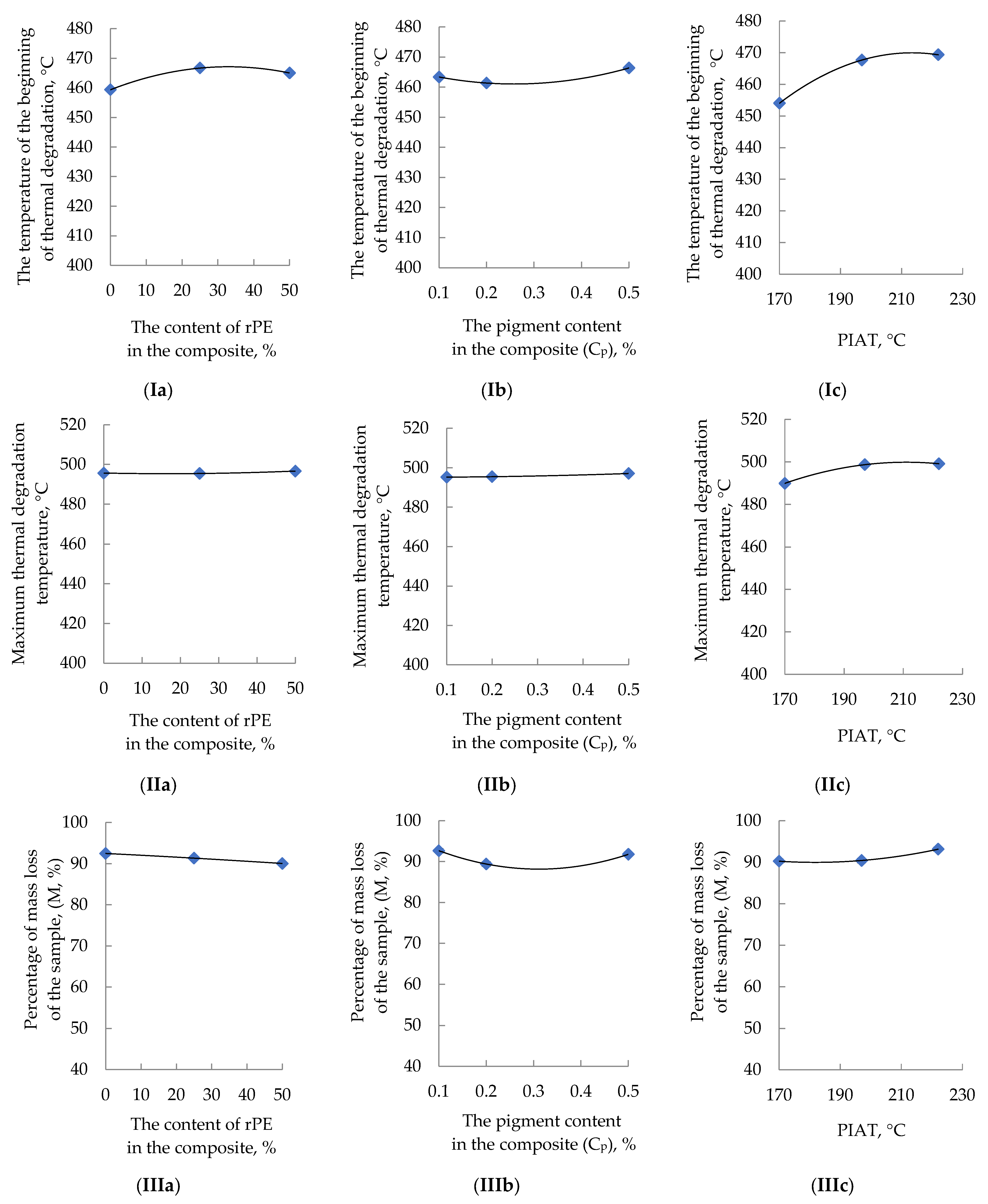

3.8. The Influence of Optimization Parameters (rPE, Cp, and PIAT) on the Thermal Properties of the Composites

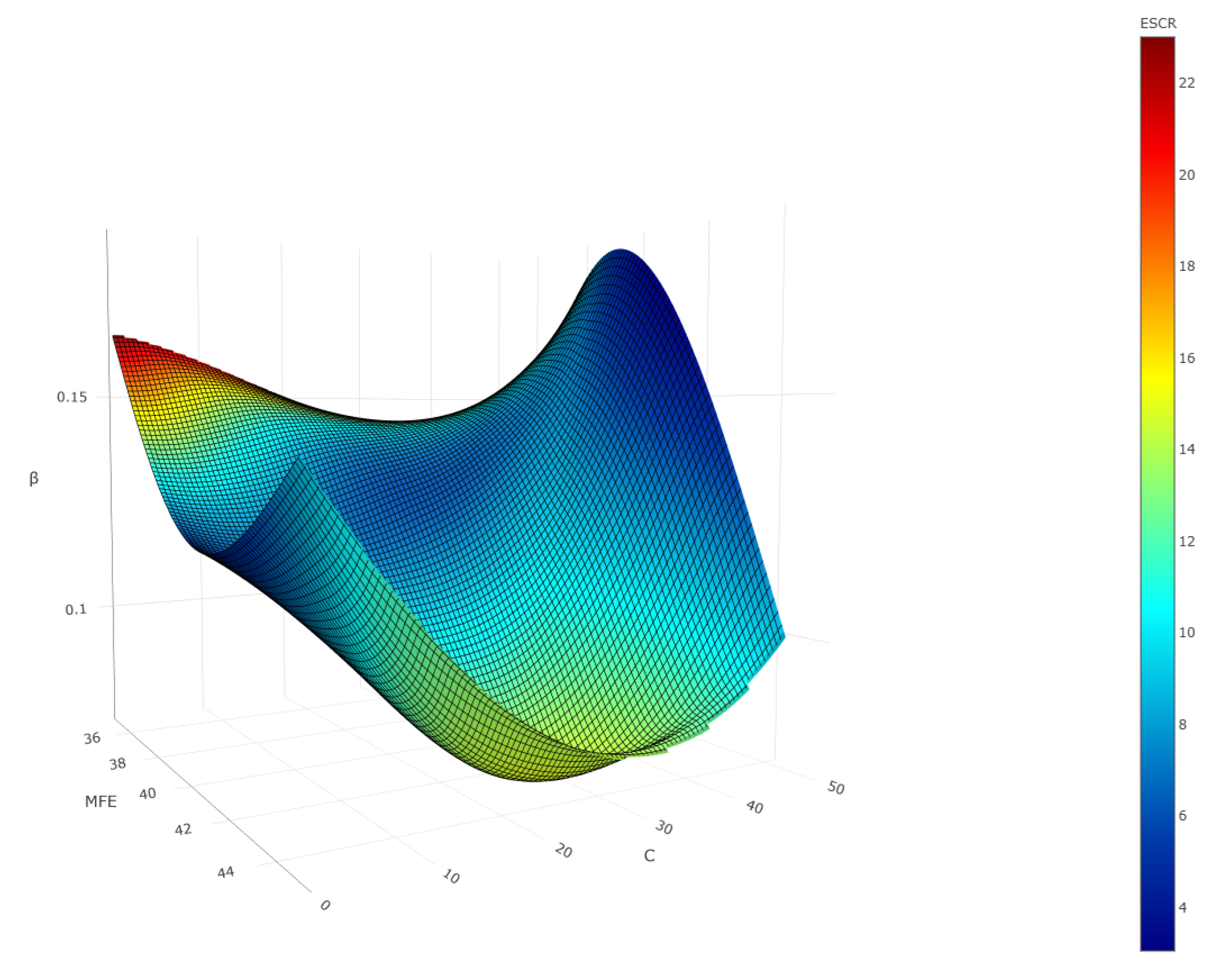

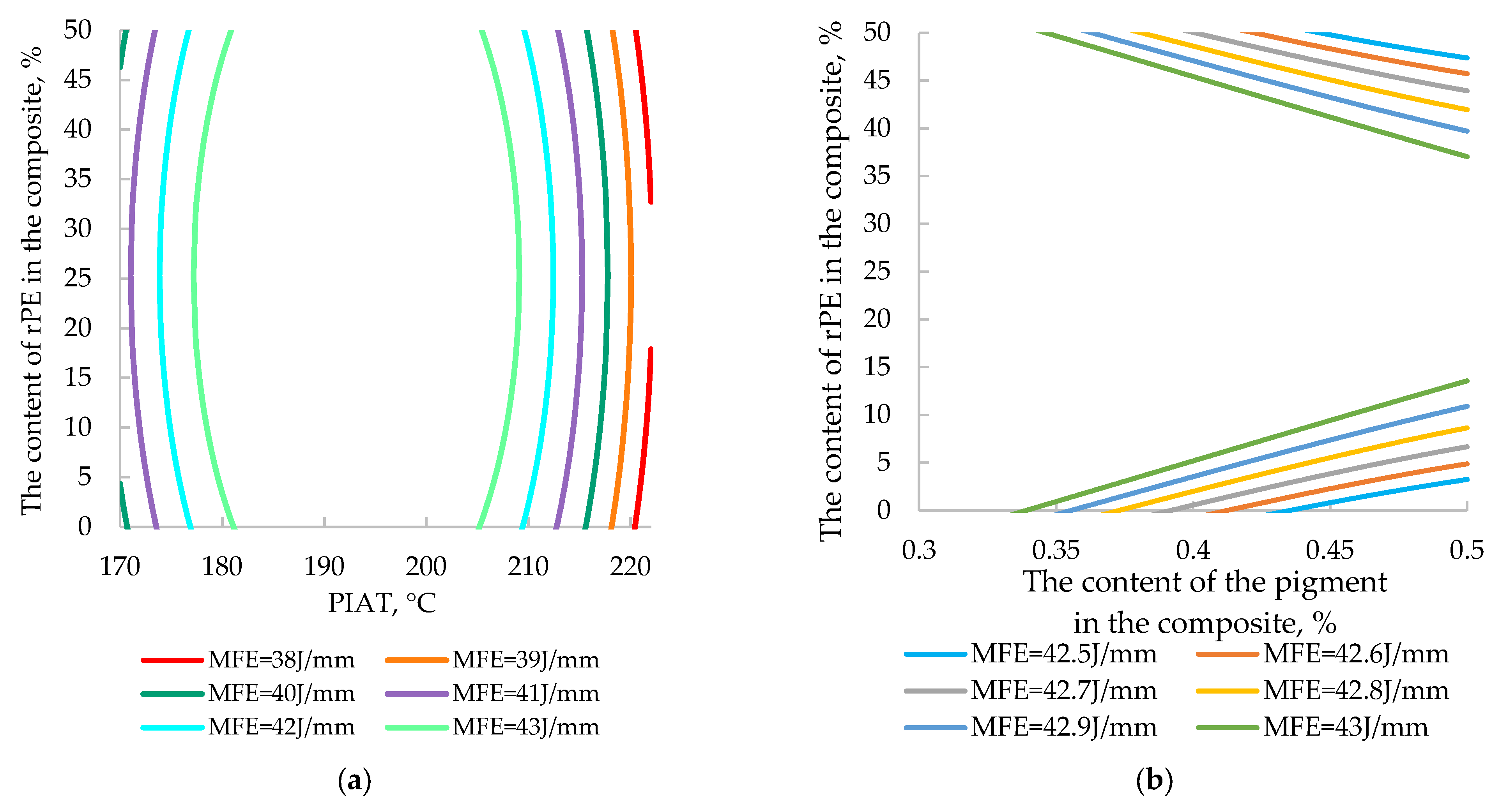

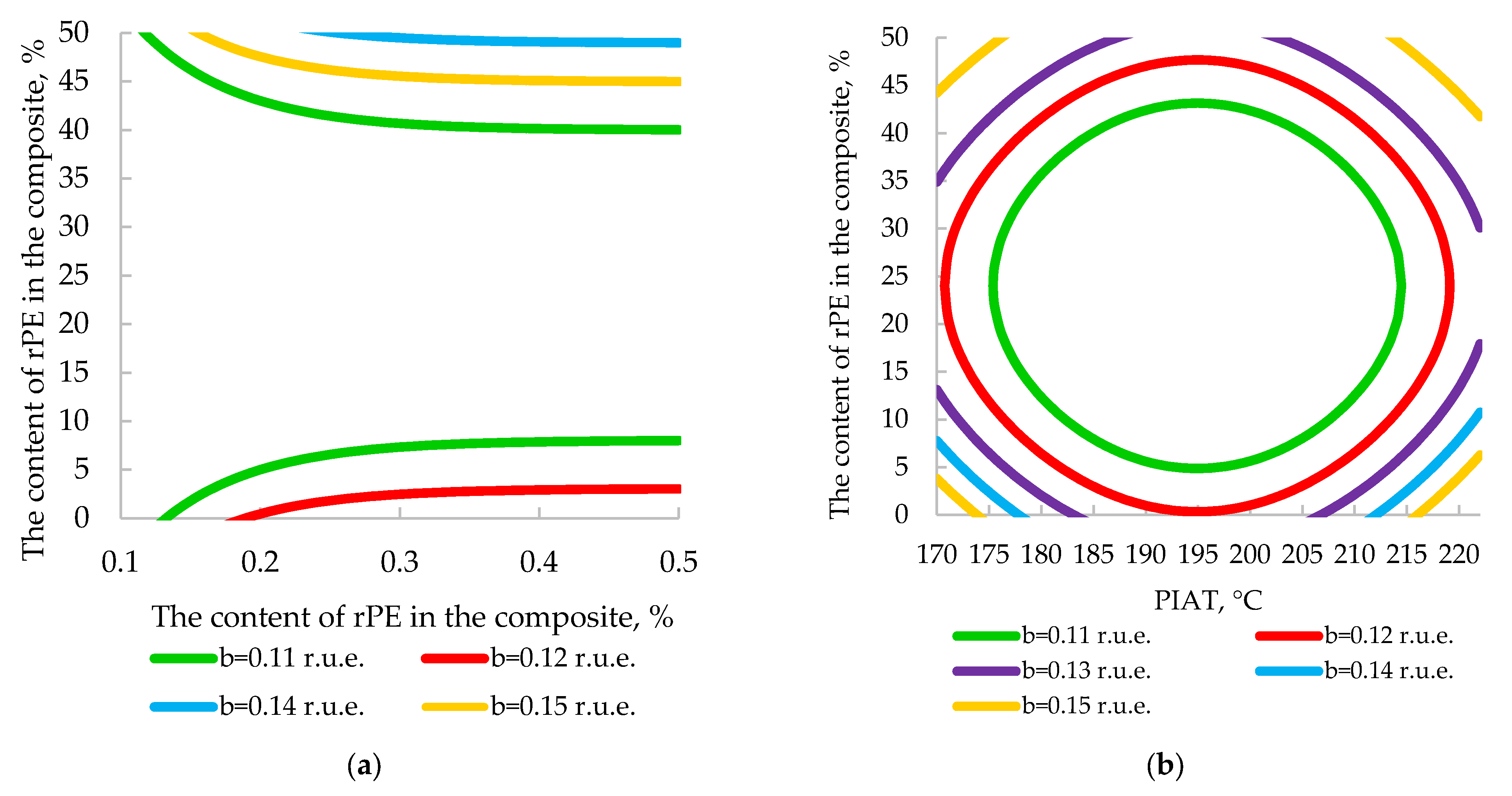

3.9. Development of a Mathematical Model

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Our ESCR tests—a standard measure of internal stress in polyethylene—showed that the ultrasonic third-harmonic amplitude β is a viable quantitative indicator of internal stress in rotomolded parts. In fact, we found a strong correlation between β and all three key performance metrics.

- IR spectroscopy and contact angle measurements showed that neither adding rPE (up to 50%) nor increasing PIAT caused any statistically significant increase in the hydrophilicity of PE. In contrast, raising the pigment concentration did measurably reduce the composites’ hydrophobicity.

- Incorporating rPE had no appreciable effect on the composites’ thermal performance. Thus, using up to 50% recycled PE in these rotomolded composites is feasible for producing items with acceptable thermal stability. Adding pigment up to 0.5% gave a slight improvement in thermal stability, and a higher PIAT also modestly enhanced thermal resistance.

- PIAT proved to be the dominant processing factor determining all the key performance characteristics of the rotomolded products. Therefore, we recommend limiting the PIAT to ~190–205 °C during processing of these composites.

- Taking into account all mechanical and thermal results (including MFEsp, β, and ESCR), the composite formulation that minimizes internal stress—and thereby maximizes performance and service life—is ~30% rPE and 0.5% pigment, with a PIAT of ~195 °C.

- In response to industry needs, we developed four nomograms (rPE = f(MFEsp, Cp, PIAT) and rPE = f(β, Cp, PIAT)) to eliminate tedious calculations. These nomograms enable rapid determination of a product’s impact strength and predicted β value based on the actual PIAT and the composite’s rPE and pigment contents. They can also be used inversely to choose appropriate rPE and pigment levels for a required impact strength or target internal stress (β).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, Use, and Fate of All Plastics Ever Made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Rayes, N.; Chang, A.; Shi, J. Plastic Management and Sustainability: A Data-Driven Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazeau, B.; Minunno, R.; Zaman, A.; Shaikh, F. Elevating Recycling Standards: Global Requirements for Plastic Traceability and Quality Testing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Raw Materials Foresight Study 2023; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://commission.europa.eu (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Lau, W.W.Y.; Shiran, Y.; Bailey, R.M.; Cook, E.; Stuchtey, M.R.; Koskella, J.; Velis, C.A.; Godfrey, L.; Boucher, J.; Murphy, M.B.; et al. Evaluating scenarios toward zero plastic pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plastics Europe. Plastics—The Facts 2022: An Analysis of European Plastics Production, Demand, and Waste. Plastics Europe. October 2022. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-facts-2022/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic Waste Inputs from Land into the Ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Samborska, V.; Roser, M. Plastic Pollution. 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/plastic-pollution (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Zhaparova, S.B.; Bayazitova, Z.E.; Bekpergenova, Z.B. Use of Plastic Waste in the Production of Polymer-Sanded Tiles; Vestnik of M. Kozybayev North-Kazakhstan University: Petropavlovsk, Kazakhstan, 2020; Volume 3, pp. 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Khassenova, A.K.; Kuantkan, B. From Waste to Wealth: International Experience in Improving the Processing of Production and Consumption Waste; Vestnik of M. Kozybayev North-Kazakhstan University: Petropavlovsk, Kazakhstan, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 74–80. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, H. How Much of Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Come from Plastics? 2023. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/ghg-emissions-plastics (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- When Did Plastic Pollution Start? 2025. Available online: https://iere.org/when-did-plastic-pollution-start (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Gall, S.C.; Thompson, R.C. The impact of debris on marine life. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 92, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Jiang, X.; Xiang, X.; Qu, P.; Zhu, M. Recent developments in recycling of post-consumer polyethylene waste. Green Chem 2025, 27, 4040–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company; Innovation Fund Denmark. The New Plastics Economy: A Research, Innovation and Business Opportunity for Denmark; McKinsey & Company: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/europe/the-new-plastics-economy-a-danish-research-innovation-and-business-opportunity (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Cafiero, L.M.; De Angelis, D.; Tuccinardi, L.; Tuffi, R. Current State of Chemical Recycling of Plastic Waste: A Focus on the Italian Experience. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Plastic Pollution Is Growing Relentlessly as Waste Management and Recycling Fall Short, Says OECD. Press Release. 22 February 2022. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/news/press-releases/2022/02/plastic-pollution-is-growing-relentlessly-as-waste-management-and-recycling-fall-short.html (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Lara-Topete, G.O.; Robles-Rodríguez, C.E.; Orozco-Nunnelly, D.A.; Vázquez-Morillas, A.; Bernache-Pérez, G.; Gradilla-Hernández, M.S. A mini review on the main challenges of implementing mechanical biological treatment plants for municipal solid waste in the Latin America region: Learning from the experiences of developed countries. Waste Manag. Res. J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2023, 41, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.H.; Amin, M.; Iqbal, A.; Nadeem, I.; Kalin, M.; Soomar, A.; Muhammad, G.; Ahmed, M. A review on gasification and pyrolysis of waste plastics. Front. Chem. 2023, 10, 960894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schyns, Z.; Shaver, M. Mechanical Recycling of Packaging Plastics: A Review. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2020, 42, e2000415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). Reducing Plastic Production to Achieve Climate Goals. September 2023. Available online: https://www.ciel.org (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Pick, L.; Hanna, P.R.; Gorman, L. Assessment of processibility and properties of raw post-consumer waste polyethylene in the rotational moulding process. J. Polym. Eng. 2020, 42, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogila, K.; Shao, M.; Yang, W.; Tan, J. Rotational molding: A review of the models and materials. Express Polym. Lett. 2017, 11, 778–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly-Walley, J.; Martin, P.; Ortega, Z.; Pick, L.; McCourt, M. Recent Advancements towards Sustainability in Rotomoulding. Materials 2024, 17, 2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, H.; Rodrigue, D. Upcycling of recycled polyethylene for rotomolding applications via dicumyl peroxide crosslinking. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e56236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarti, B. Rotomolding Market Report 2025 (Global Edition). 2025. Available online: https://www.cognitivemarketresearch.com/rotomolding-market-report (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Biddle, M.B.; Villwock, R.D.; Tanner, J.M. Polyethylene Blends for Molding. WO1993000400A1, 7 January 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Unkles, P.J.; United States Patent and Trademark Office. Multilayer Structure with Recycled Polyolefin Layer for Rotational Molding Applications. US6180203B1, 30 January 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Carl-Gustav, E.; Wannerskog, A.; Rieder, S.; Ruemer, F.; World Intellectual Property Organization. Polyethylene Compositions with Crosslinked Polyethylene Waste (XLPE) for Rotational Molding. WO2016102341A1, 30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Quan, D.; Guo, Y.; Wu, D. One-Step Method for Foamed Rotational Molding Products Using Recycled XLPE. CN109664584B, 24 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Graeme, H.; Rijkmans, B.; Petinakis, E.; World Intellectual Property Organization. Multilayer Structures with PCR Polyethylene for Rotational Molding. WO2021222984A1, 11 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, H.; D’Agostino, C.; Canadian Intellectual Property Office. Rotational Molding Compositions Comprising Virgin and PCR Polyethylene. CA3190761A1, 25 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino, C.; Arnould, G.; United States Patent and Trademark Office. Rotomolding Compositions with Controlled PCR Segregation for Improved Adhesion. US20230093454A1, 30 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino, C.; Arnould, G.; Bellehumeur, C.; Hay, H.; Dang, V.; United States Patent and Trademark Office. Rotomolding Compositions Enabling Surface Roughness Control via Recycled Polymers. US20230124453A1, 27 April 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, H.; D’Agostino, C.; United States Patent and Trademark Office. Phase Segregation Strategies for Rotomolded Products with Enhanced Surface Adhesion. US20230339150A1, 26 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bellehumeur, C.; Rajkovic, A.; Hay, H.; Tracy, L.; World Intellectual Property Organization. Three-Component Polyethylene Compositions with rPE for Rotational Molding. WO2025114813A1, 1 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cestari, S.P.J.; Martin, P.R.; Hanna, P.P.; Kearns, M.; Mendes, L.C.; Millar, B. Use of Virgin/Recycled Polyethylene Blends in Rotational Moulding. J. Polym. Eng. 2021, 41, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, S.; Ortega, Z.; McCourt, M.; Kearns, M.P.; Benítez, A.N. Recycling of Polymeric Fraction of Cable Waste by Rotational Moulding. Waste Manag. 2018, 76, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaisrichawla, S.; Dangtungee, R. The Usage of Recycled Material in Rotational Molding Process for Production of Septic Tank. Mater. Sci. Forum 2018, 936, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.; Mendes, G.A.; de Oliveira, A.M.; Dias, C.G.B.T. Manufacture and Characterization of Polypropylene (PP) and High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) Blocks for Potential Use as Masonry Component in Civil Construction. Polymers 2022, 14, 2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saifullah, A.; Radhakrishnan, P.; Wang, L.; Saeed, B.; Sarker, F.; Dhakal, H.N. Reprocessed Materials Used in Rotationally Moulded Sandwich Structures for Enhancing Environmental Sustainability: Low-Velocity Impact and Flexure-after-Impact Responses. Materials 2022, 15, 6491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aníśko, J.A.; Barczewski, M.; Mietliński, P.M.; Piasecki, A.; Szulc, J. Valorization of Disposable Polylactide (PLA) Cups by Rotational Molding Technology: The Influence of Pre-Processing Grinding and Thermal Treatment. Polym. Test. 2022, 107, 107481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaker, R.; Rodrigue, D. Rotomolding of Thermoplastic Elastomers Based on Low-Density Polyethylene and Recycled Natural Rubber. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Rodrigue, D. Morphological, Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Recycled HDPE Foams via Rotational Molding. J. Cell. Plast. 2022, 58, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F.P.C.; Thompson, M.R. Analysis of Mullins Effect in Polyethylene Using Ultrasonic Guided Waves. Polym. Test. 2017, 60, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.P.C.; West, W.T.J.; Thompson, M.R. Effects of Annealing and Swelling to Initial Plastic Deformation of Polyethylene Probed by Nonlinear Ultrasonic Guided Waves. Polymer 2017, 131, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1693-21; Standard Test Method for Environmental Stress-Cracking of Ethylene Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- ISO 16770:2004; Plastics—Determination of Environmental Stress Cracking (ESC) of Polyethylene—Full-Notch Creep Test (FNCT). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- Gomes, F.P.C. Nondestructive Evaluation of Sintering and Degradation for Rotational Molded Polyethylene. Polym. Test. 2018, 65, 468–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, F.P.C. Nondestructive Evaluation of Polyethylene Using Nonlinear Ultrasonics. Ph.D. Thesis, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 16770:2019; Plastics—Determination of Environmental Stress Cracking (ESC) of Polyethylene—Full-Notch Creep Test (FNCT). ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/70480.html (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Tyukanko, V.; Demyanenko, A.; Semenyuk, V.; Dyuryagina, A.; Alyoshin, D.; Tarunin, R.; Voropaeva, V. Development of an ultrasonic method for the quality control of polyethylene tanks manufactured using rotational molding technology. Polymers 2023, 15, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Topic Centre Waste and Materials in a Green Economy (ETC/WMGE). Are We Losing Resources When Managing Europe’s Waste? Eionet Report No. ETC/WMGE 2019/3; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019; Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-wmge/products/etc-wmge-reports/are-we-losing-resources-when-managing-europes-waste-1 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- INEOS Olefins & Polymers USA. Environmental Stress Crack Resistance of Polyethylene; Technical Report; INEOS Olefins & Polymers USA: League City, TX, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.ineos.com/globalassets/ineos-group/businesses/ineos-olefins-and-polymers-usa/products/technical-information--patents/ineos-environmental-stress-crack-resistance-of-pe.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Dyuryagina, A.; Lutsenko, A.; Demyanenko, A.; Tyukanko, V.; Ostrovnoy, K.; Yanevich, A. Modeling the Wetting of Titanium Dioxide and Steel Substrate in Water-Borne Paint and Varnish Materials in the Presence of Surfactants. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2022, 1, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyukanko, V.; Demyanenko, A.; Dyuryagina, A.; Ostrovnoy, K.; Lezhneva, M. Optimization of the Composition of Silicone Enamel by the Taguchi Method Using Surfactants Obtained from Oil Refining Waste. Polymers 2021, 13, 3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyuryagina, A.N.; Lutsenko, A.A.; Tyukanko, V.Y. Study of the Disperse Effect of Polymeric Surface-Active Substances in Acrylic Dispersions Used for Painting Oil Well Armature. Bull. Tomsk. Polytech. Univ. Geo Assets Eng. 2019, 330, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Dyuryagina, A.; Lutsenko, A.; Ostrovnoy, K.; Tyukanko, V.; Demyanenko, A.; Akanova, M. Exploration of the Adsorption Reduction of the Pigment Aggregates Strength under the Effect of Surfactants in Water-Dispersion Paints. Polymers 2022, 14, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyukanko, V.Y.; Duryagina, A.N.; Ostrovnoy, K.A.; Demyanenko, A.V. Study of Wetting of Aluminum and Steel Substrates with Polyorganosiloxanes in the Presence of Nitrogen-Containing Surfactants. Bull. Tomsk. Polytech. Univ. Geo Assets Eng. 2017, 328, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrovnoy, K.; Dyuryagina, A.; Demyanenko, A.; Tyukanko, V. Optimization of Titanium Dioxide Wetting in Alkyd Paint and Varnish Materials in the Presence of Surfactants. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2021, 4, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyukanko, V.; Demyanenko, A.; Dyuryagina, A.; Ostrovnoy, K.; Aubakirova, G. Optimizing the Composition of Silicone Enamel to Ensure Maximum Aggregative Stability of Its Suspensions Using Surfactant Obtained from Oil Refining Waste. Polymers 2022, 14, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyukanko, V.; Demyanenko, A.; Semenyuk, V.; Alyoshin, D.; Brilkov, S.; Litvinov, S.; Shirina, T.; Akhmetzhanov, E. Identification of Patterns of the Stress–Strain State of a Standard Plastic Tank for Liquid Mineral Fertilizers. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2024, 4, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyukanko, V.; Demyanenko, A.; Semenyuk, V.; Dyuryagina, A.; Alyoshin, D.; Brilkov, S.; Litvinov, S.; Byzova, Y. Optimization of Polyethylene Rotomolded Tank Design for Storage of Liquid Mineral Fertilizers by the Taguchi Method. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2024, 3, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyuryagina, A.; Byzova, Y.; Ostrovnoy, K.; Demyanenko, A.; Tyukanko, V.; Lutsenko, A. The Effect of the Microstructure and Viscosity of Modified Bitumen on the Strength of Asphalt Concrete. Polymers 2024, 16, 1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyuryagina, A.N.; Byzova, Y.S.; Ostrovnoy, K.A.; Tyukanko, V.Y. Utilization of the Waste Sealing Liquid Component in Asphalt Concrete Pavements. Bull. Tomsk. Polytech. Univ. Geo Assets Eng. 2021, 332, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Association of Rotational Molders International (ARM). Low Temperature Impact Test. ARM Technical Document. 2023. Available online: https://cdn.ymaws.com/rotomolding.org/resource/resmgr/pdf/lowtemp.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Sorasan, C.; Ortega-Ojeda, F.E.; Rodríguez, A.; Rosal, R. Modelling the Photodegradation of Marine Microplastics by Means of Infrared Spectrometry and Chemometric Techniques. Microplastics 2022, 1, 198–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Savino, I.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V.F. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy to Assess the Degree of Alteration of Artificially Aged and Environmentally Weathered Microplastics. Polymers 2023, 15, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | Optimization Parameters | Obtained Experimental Parameters of Composites | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rPE Content (%) | Pigment Content (%) | PIAT (°C) | Third-Harmonic Amplitude β (r.u.a.) | Mechanical Properties of the Obtained Composites | MFEsp (J/mm) | Contact Angle θ (°) | ESCR (h) | Thermal Properties of the Obtained Composites | ||||||

| Max. Tensile Stress at Break (MPa) | Tensile Yield Stress (MPa) | Elongation at Break (%) | FLEXURAL Modulus E (MPa) | Onset Degradation Temp. Tb (°C) | Max Mass-Loss Temp. Tmax (°C) | Mass Loss M (%) | ||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 0.1 | 170 | 0.120 | 19.90 | 18.60 | 556.0 | 168 | 40.4 | 81.3 | 5 | 450 | 488.9 | 92.3 |

| 2 | 0 | 0.2 | 197 | 0.120 | 19.22 | 18.27 | 540.8 | 159 | 40 | 83.7 | 7 | 459 | 489.8 | 88.5 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.5 | 222 | 0.185 | 23.50 | 21.50 | 861.0 | 153 | 39 | 69.9 | 6.5 | 453 | 490.8 | 90.0 |

| 4 | 25 | 0.2 | 170 | 0.140 | 22.02 | 18.00 | 665.8 | 170 | 45 | 76.0 | 9 | 456 | 497.0 | 90.2 |

| 5 | 25 | 0.5 | 197 | 0.080 | 19.50 | 18.20 | 755.0 | 151 | 43 | 66.3 | 14 | 474 | 499.4 | 90.4 |

| 6 | 25 | 0.1 | 222 | 0.100 | 22.10 | 18.25 | 925.0 | 148 | 44.5 | 81.6 | 9 | 473 | 499.6 | 90.6 |

| 7 | 50 | 0.5 | 170 | 0.165 | 19.80 | 19.50 | 281.0 | 121 | 35 | 76.2 | 7 | 472 | 500.9 | 94.5 |

| 8 | 50 | 0.1 | 197 | 0.12 | 20.70 | 18.75 | 751.0 | 171 | 40 | 72.7 | 18 | 467 | 497.0 | 95.1 |

| 9 | 50 | 0.2 | 222 | 0.161 | 21.90 | 18.60 | 974.0 | 115 | 37 | 68.4 | 17 | 469 | 499.4 | 89.5 |

| Estimated Parameter | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | YM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MFEsp | −0.00136 | 0.0687 | 40.133 | 10.278 | −12.75 | 42.806 | −0.008367 | 3.2323 | −267.89 | 40.43 |

| β | 0.00006 | −0.0029 | 0.1417 | 0.145 | −15.00 | - | 0.0000572 | −0.0223 | 2.2789 | 0.13 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tyukanko, V.; Tarunin, R.; Demyanenko, A.; Semenyuk, V.; Dyuryagina, A.; Merkibayev, Y.; Bakibaev, A.; Alpyssov, R.; Alyoshin, D. Optimization of Composite Formulation Using Recycled Polyethylene for Rotational Molding. Polymers 2025, 17, 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243290

Tyukanko V, Tarunin R, Demyanenko A, Semenyuk V, Dyuryagina A, Merkibayev Y, Bakibaev A, Alpyssov R, Alyoshin D. Optimization of Composite Formulation Using Recycled Polyethylene for Rotational Molding. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243290

Chicago/Turabian StyleTyukanko, Vitaliy, Roman Tarunin, Alexandr Demyanenko, Vladislav Semenyuk, Antonina Dyuryagina, Yerik Merkibayev, Abdigali Bakibaev, Rustam Alpyssov, and Dmitriy Alyoshin. 2025. "Optimization of Composite Formulation Using Recycled Polyethylene for Rotational Molding" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243290

APA StyleTyukanko, V., Tarunin, R., Demyanenko, A., Semenyuk, V., Dyuryagina, A., Merkibayev, Y., Bakibaev, A., Alpyssov, R., & Alyoshin, D. (2025). Optimization of Composite Formulation Using Recycled Polyethylene for Rotational Molding. Polymers, 17(24), 3290. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243290