The Transition State of PBLG Studied by Deuterium NMR

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of the PBLG Samples

2.2. NMR Measurements

3. Results

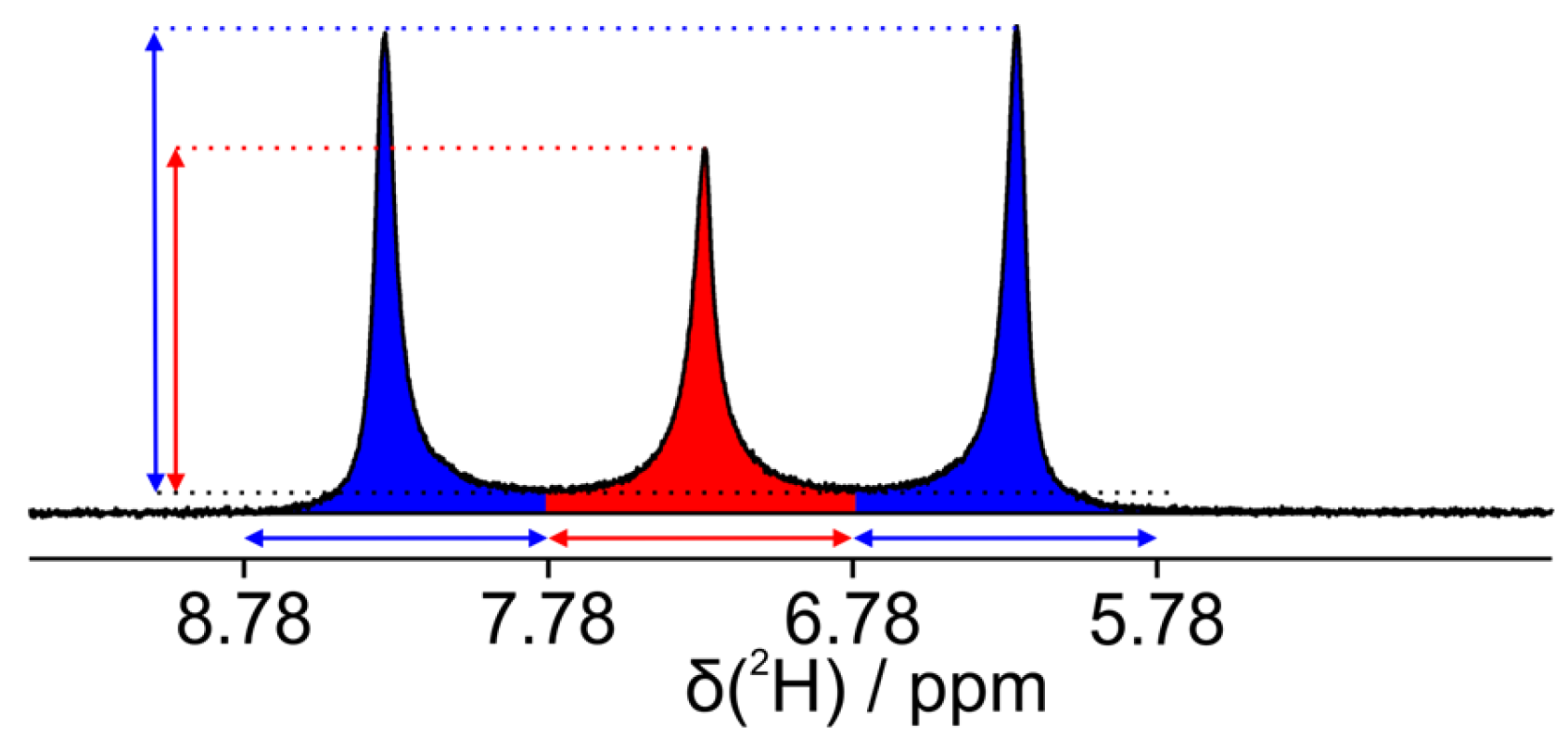

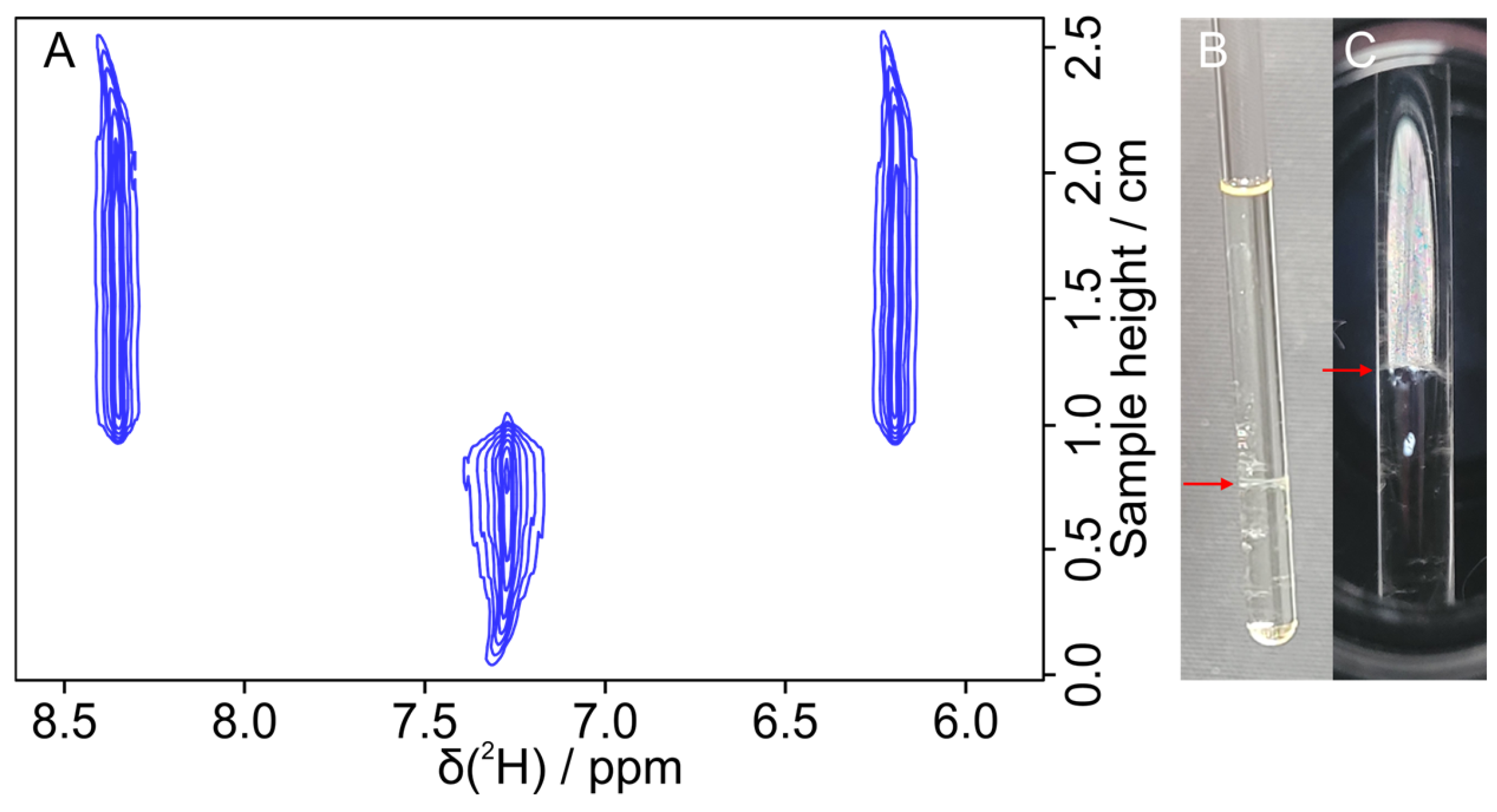

3.1. Dilution Study Without Solute Molecules

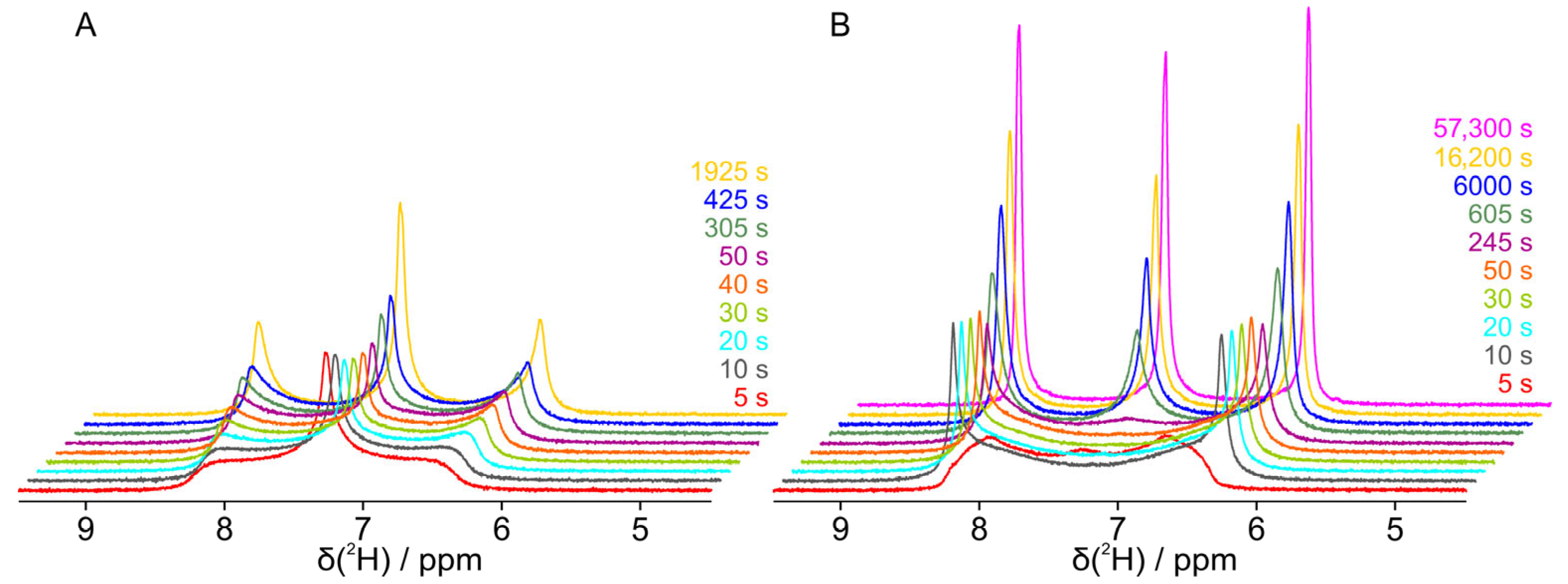

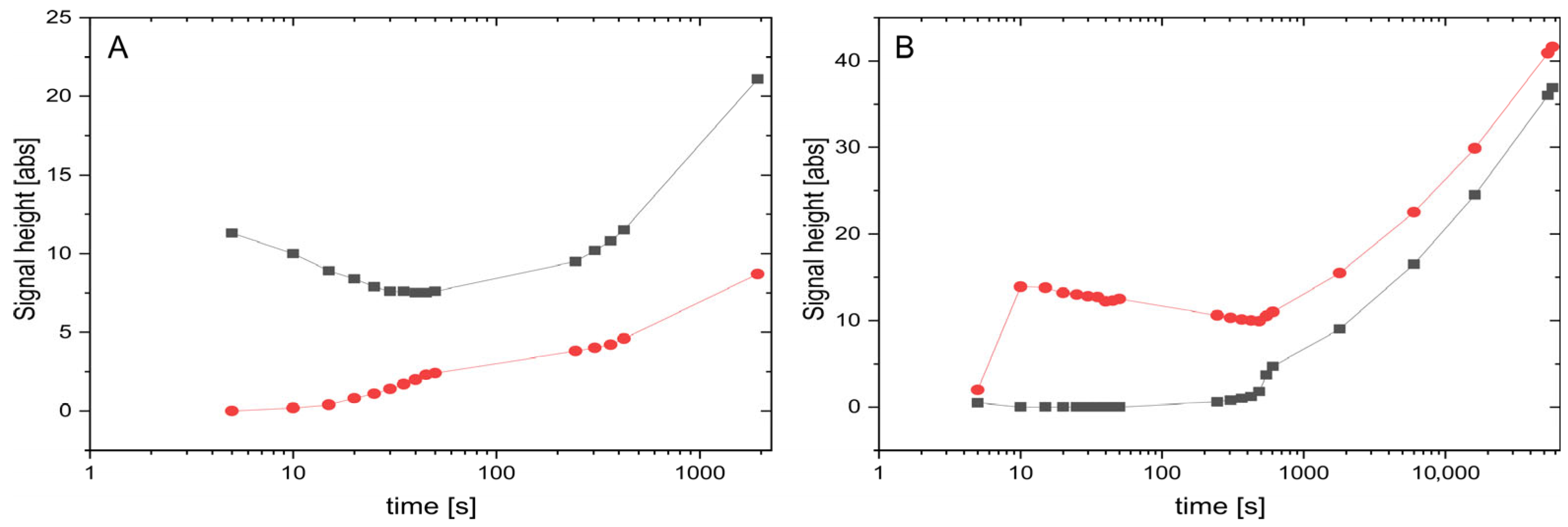

3.2. Measurement of Kinetic Behavior of Coexisting Phases at the Transition

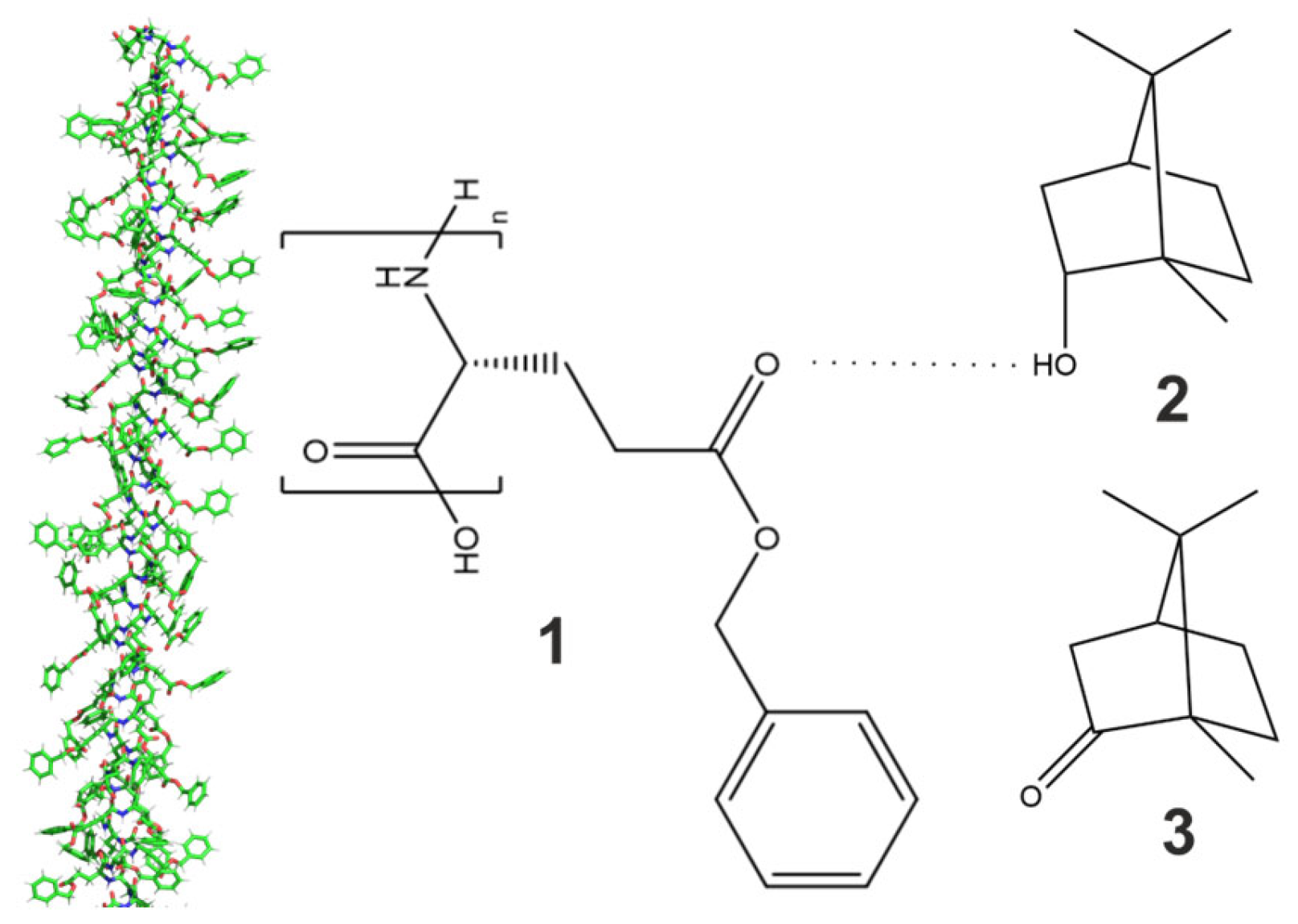

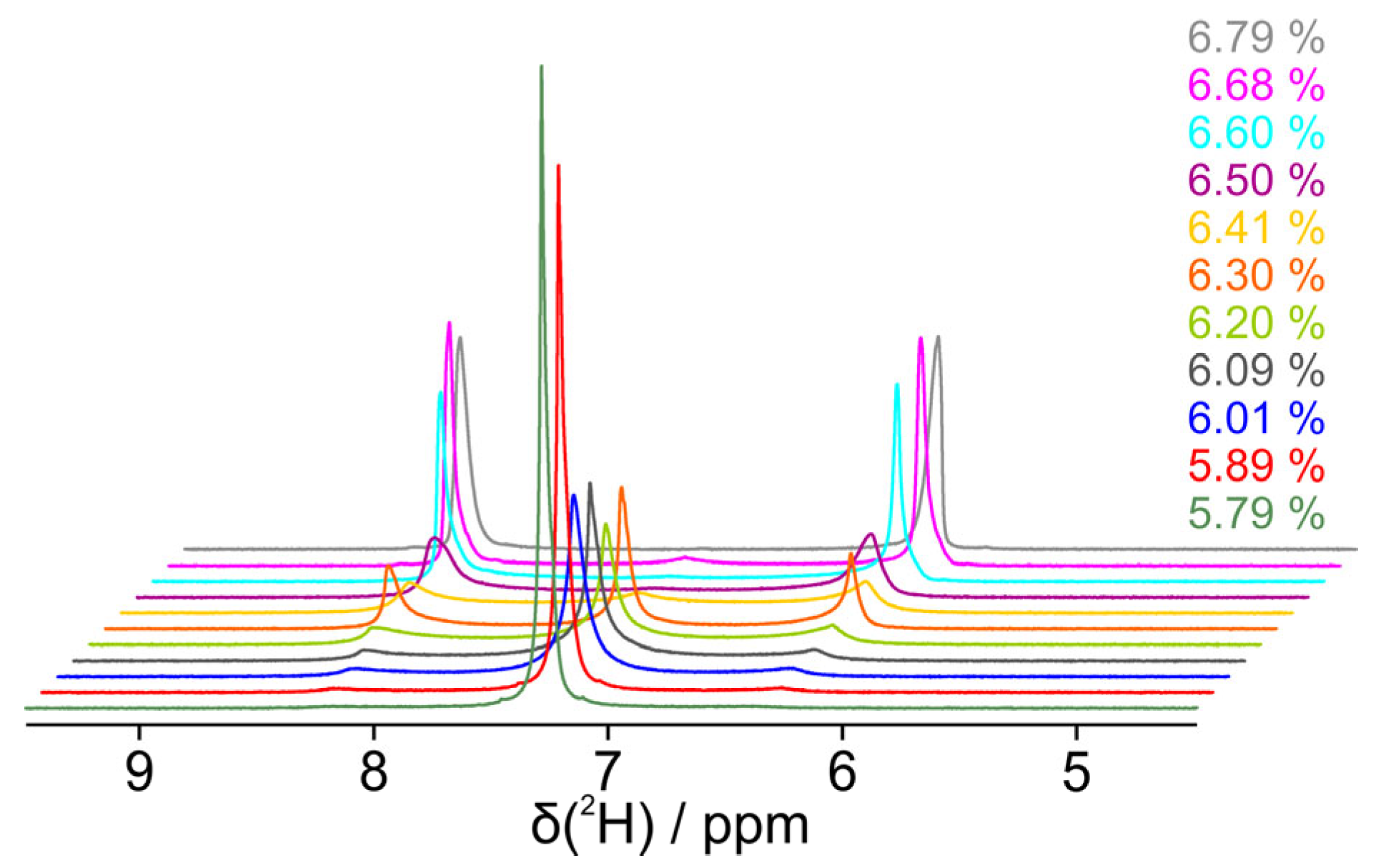

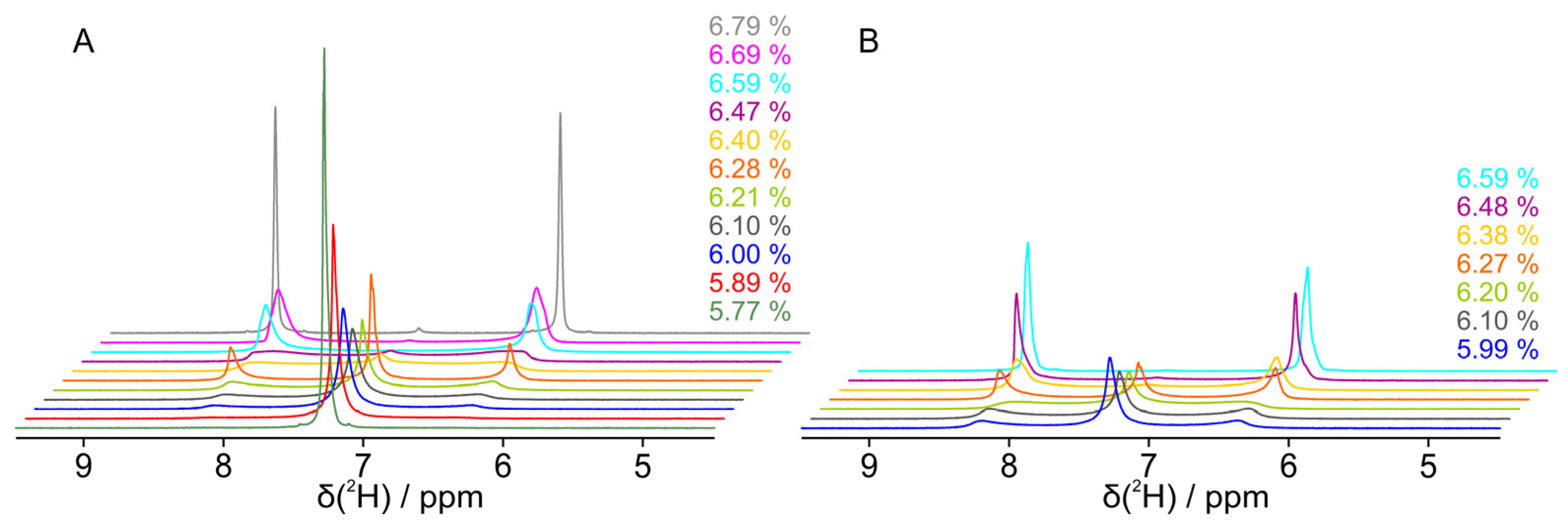

3.3. Influence of Borneol and Camphor on Phase Transition

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sarfati, M.; Lesot, P.; Merlet, D.; Courtieu, J. Theoretical and Experimental Aspects of Enantiomeric Differentiation Using Natural Abundance Multinuclear Nmr Spectroscopy in Chiral Polypeptide Liquid Crystals. Chem. Commun. 2000, 21, 2069–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesot, P.; Aroulanda, C.; Berdagué, P.; Meddour, A.; Merlet, D.; Farjon, J.; Giraud, N.; Lafon, O. Multinuclear NMR in Polypeptide Liquid Crystals: Three Fertile Decades of Methodological Developments and Analytical Challenges. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2020, 116, 85–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsley, J.W.; Lindon, J.C. NMR Spectroscopy Using Liquid Crystal Solvents; Pergamon Press Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kummerlöwe, G.; Luy, B. Residual Dipolar Couplings as a Tool in Determining the Structure of Organic Molecules. TrAC 2009, 28, 483–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.-W.; Liu, H.; Qiu, F.; Wang, X.-J.; Lei, X.-X. Residual Dipolar Couplings in Structure Determination of Natural Products. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2018, 8, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Saurí, J.; Mevers, E.; Peczuh, M.W.; Hiemstra, H.; Clardy, J.; Martin, G.E.; Williamson, R.T. Unequivocal Determination of Complex Molecular Structures Using Anisotropic NMR Measurements. Science 2017, 356, eaam5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummerlöwe, G.; Crone, B.; Kretschmer, M.; Kirsch, S.F.; Luy, B. Residual Dipolar Couplings as a Powerful Tool for Constitutional Analysis: The Unexpected Formation of Tricyclic Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2643–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroulanda, C.; Lesot, P. Molecular Enantiodiscrimination by NMR Spectroscopy in Chiral Oriented Systems: Concept, Tools, and Applications. Chirality 2022, 34, 182–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesot, P.; Berdagué, P.; Silvestre, V.; Remaud, G. Exploring the Enantiomeric 13C Position-Specific Isotope Fractionation: Challenges and Anisotropic NMR-Based Analytical Strategy. Anal Bioanal Chem 2021, 413, 6379–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luy, B. Distinction of Enantiomers by NMR Spectroscopy Using Chiral Orienting Media. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2010, 90, 119–132. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, N.; Fuentes-Monteverde, J.C.; Pech-Puch, D.; Rodríguez, J.; Jiménez, C.; Noll, M.; Kreiter, A.; Reggelin, M.; Navarro-Vázquez, A.; Griesinger, C. Relative Configuration of Micrograms of Natural Compounds Using Proton Residual Chemical Shift Anisotropy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, F.; Kouřil, K.; Berger, S.T.; Meier, B.; Luy, B. Rheo-NMR at the Phase Transition of Liquid Crystalline Poly-γ-Benzyl-l-Glutamate: Phase Kinetics and a Valuable Tool for the Measurement of Residual Dipolar Couplings. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 7782–7794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. Liquid-Crystalline Structures in Solutions of a Polypeptide. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1956, 52, 571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. The Cholesteric Phase in Polypeptide Solutions and Biological Structures. Mol. Cryst. 1966, 1, 467–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.G.; Wu, C.C.; Wee, E.L.; Santee, G.L.; Rai, J.H.; Goebel, K.G. Thermodynamics and Dynamics of Polypeptide Liquid Crystals. Pure Appl. Chem. 1974, 38, 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.G.; Wee, E.L. Liquid Crystal-Isotropic Phase Equilibriums in the System Poly(Gamma.-Benzyl. Alpha.-L-Glutamate)-Methylformamide. J. Phys. Chem. 1971, 75, 1446–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, S.; Tokuma, K.; Uematsu, I. Phase Behavior of Poly(γ-Benzyl L-Glutamate) Solutions in Benzyl Alcohol. Polym. Bull. 1983, 10, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flory, P.L. Phase Equilibria in Solutions of Rod-like Particles. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 1956, 234, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, B.M.; Shepelevskii, A.A. Construction of The Full Phase Diagram for The System Of Poly(γ-Benzyl-l-Glutamate)/Dimethylformamide on the Basis of the Complex of Literature Data. J. Macromol. Sci. Part B 2003, 42, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Müller, E.A.; Jackson, G. Understanding and Describing the Liquid-Crystalline States of Polypeptide Solutions: A Coarse-Grained Model of PBLG in DMF. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 1482–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.G.; Kou, L.; Tohyama, K.; Voltaggio, V. Kinetic Aspects of the Formation of the Ordered Phase in Stiff-Chain Helical Polyamino Acids. J. Polym. Sci. C Polym. Symp. 1978, 65, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarniecka, K.; Samulski, E.T. Polypeptide Liquid Crystals: A Deuterium NMR Study. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1981, 63, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliks, M.D.; Park, Y.W.; Samulski, E.T. Poly-γ-Benzyl-L-Glutamate: Order Parameter, Oriented Gel, and Novel Derivatives. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. Incorporating. Nonlinear Opt. 1987, 153, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merle, C.; Kummerlöwe, G.; Freudenberger, J.C.; Halbach, F.; Stöwer, W.; Gostomski, C.L.V.; Höpfner, J.; Beskers, T.; Wilhelm, M.; Luy, B. Crosslinked Poly(Ethylene Oxide) as a Versatile Alignment Medium for the Measurement of Residual Anisotropic NMR Parameters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 10309–10312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luy, B.; Kobzar, K.; Knör, S.; Furrer, J.; Heckmann, D.; Kessler, H. Orientational Properties of Stretched Polystyrene Gels in Organic Solvents and the Suppression of Their Residual 1H NMR Signals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 6459–6465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsing, D.; Luy, B.; Kozlowska, M. Enantiomer Differentiation by Interaction-Specific Prediction of Residual Dipolar Couplings in Spherical-like Molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2024, 20, 6454–6469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sager, E.; Tzvetkova, P.; Lingel, A.; Gossert, A.D.; Luy, B. Hydrogen Bond Formation May Enhance RDC-Based Discrimination of Enantiomers. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2024, 62, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trigo-Mouriño, P.; Merle, C.; Koos, M.R.M.; Luy, B.; Gil, R.R. Probing Spatial Distribution of Alignment by Deuterium NMR Imaging. Chem. Eur. J. 2013, 19, 7013–7019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakamoto, R. Phase Separation of Poly(γ-Benzyl L-Glutamate) to Liquid Crystal and Isotropic Solution in Various Helicogenic Solvents. Colloid Polym. Sci. 1984, 262, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, J.C.; Donald, A.M. Phase Separation in the Poly(γ-Benzyl-α,l-Glutamate)/Benzyl Alcohol System and Its Role in Gelation. Polymer 1991, 32, 2418–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, P. Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Gelation in the Poly(γ-Benzyl α,l-Glutamate)—Benzyl Alcohol System. Polymer 1992, 33, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.L.; Dupré, D.B. Spherulite Morphology in Liquid Crystals of Polybenzylglutamates. Optical Rotatory Power and Effect of Magnetic Field. J. Polym. Sci. Polym. Phys. 1980, 18, 1599–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjandra, N.; Bax, A. Direct Measurement of Distances and Angles in Biomolecules by NMR in a Dilute Liquid Crystalline Medium. Science 1997, 278, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiele, C.M.; Berger, S. Probing the Diastereotopicity of Methylene Protons in Strychnine Using Residual Dipolar Couplings. Org. Lett. 2003, 5, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luy, B.; Kobzar, K.; Kessler, H. An Easy and Scalable Method for the Partial Alignment of Organic Molecules for Measuring Residual Dipolar Couplings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1092–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sackmann, E.; Meiboom, S.; Snyder, L.C. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectra of Enantiomers in Optically Active Liquid Crystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 2183–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recchia, M.J.J.; Cohen, R.D.; Liu, Y.; Sherer, E.C.; Harper, J.K.; Martin, G.E.; Williamson, R.T. “One-Shot” Measurement of Residual Chemical Shift Anisotropy Using Poly-γ-Benzyl-l-Glutamate as an Alignment Medium. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 8850–8854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doro-Goldsmith, E.; Song, Q.; Li, X.-L.; Li, X.-M.; Hu, X.-Y.; Li, H.-L.; Liu, H.-R.; Wang, B.-G.; Sun, H. Absolute Configuration of 12S-Deoxynortryptoquivaline from Ascidian-Derived Fungus Aspergillus Clavatus Determined by Anisotropic NMR and Chiroptical Spectroscopy. J. Nat. Prod. 2024, 87, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Chen, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; He, L. Temperature-Controllable Liquid Crystalline Medium for Stereochemical Elucidation of Organic Compounds via Residual Chemical Shift Anisotropies. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 2914–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.-L.; Chi, L.-P.; Navarro-Vázquez, A.; Hwang, S.; Schmieder, P.; Li, X.-M.; Li, X.; Yang, S.-Q.; Lei, X.; Wang, B.-G.; et al. Stereochemical Elucidation of Natural Products from Residual Chemical Shift Anisotropies in a Liquid Crystalline Phase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 2301–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallwass, F.; Schmidt, M.; Sun, H.; Mazur, A.; Kummerlöwe, G.; Luy, B.; Navarro-Vázquez, A.; Griesinger, C.; Reinscheid, U.M. Residual Chemical Shift Anisotropy (RCSA): A Tool for the Analysis of the Configuration of Small Molecules. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 9487–9490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kummerlöwe, G.; Grage, S.L.; Thiele, C.M.; Kuprov, I.; Ulrich, A.S.; Luy, B. Variable Angle NMR Spectroscopy and Its Application to the Measurement of Residual Chemical Shift Anisotropy. J. Magn. Reson. 2011, 209, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoffmann, F.M.; Luy, B. The Transition State of PBLG Studied by Deuterium NMR. Polymers 2025, 17, 3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243280

Hoffmann FM, Luy B. The Transition State of PBLG Studied by Deuterium NMR. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243280

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoffmann, Fabian M., and Burkhard Luy. 2025. "The Transition State of PBLG Studied by Deuterium NMR" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243280

APA StyleHoffmann, F. M., & Luy, B. (2025). The Transition State of PBLG Studied by Deuterium NMR. Polymers, 17(24), 3280. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243280