Functionalization Strategies of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes (NIPUs): A Systematic Review of Mechanical and Biological Advances

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

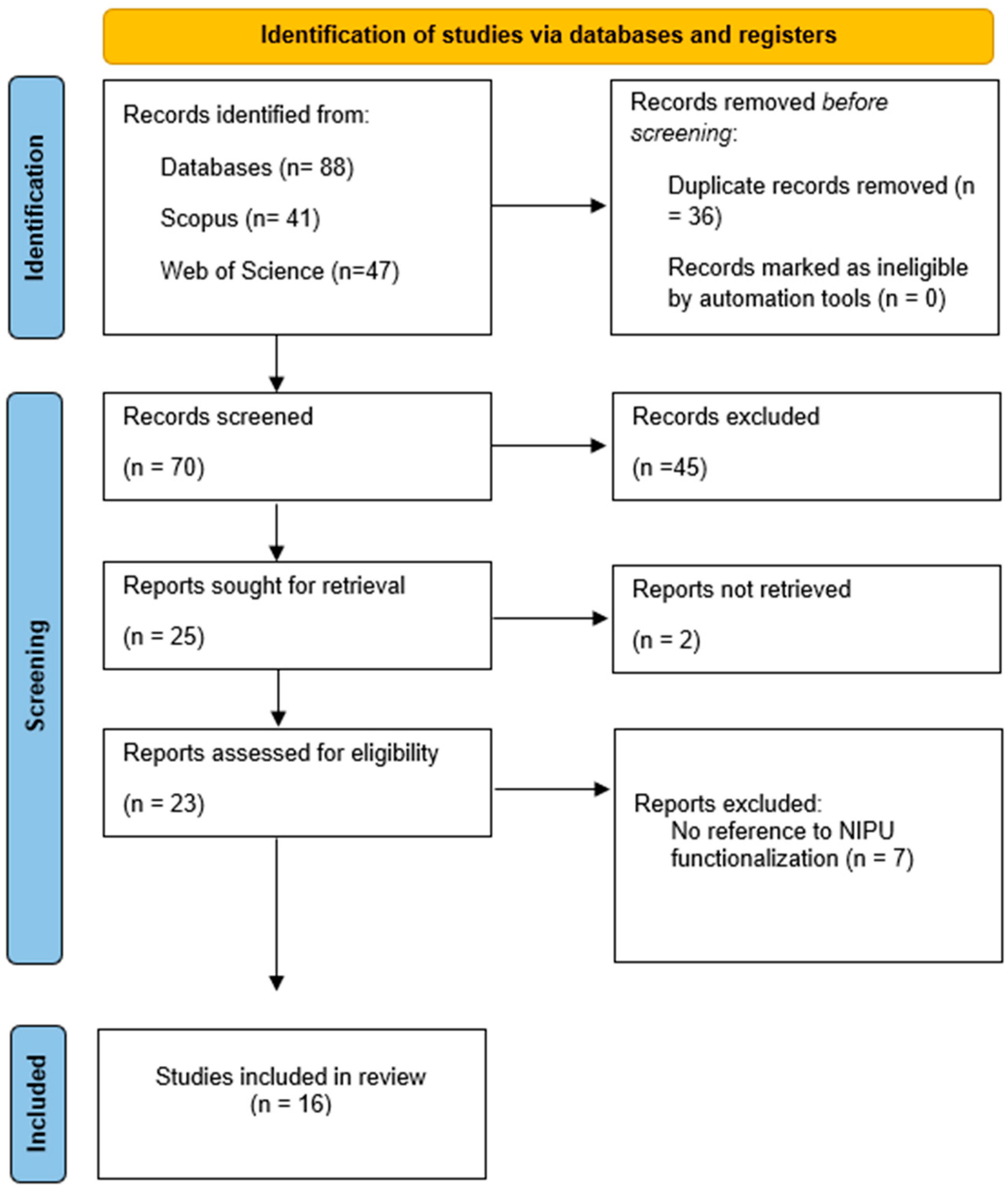

2.3. Selection and Data Collection Process

3. Results

3.1. Selection Process and Overview of Articles Included

3.2. Functionalized NIPUs

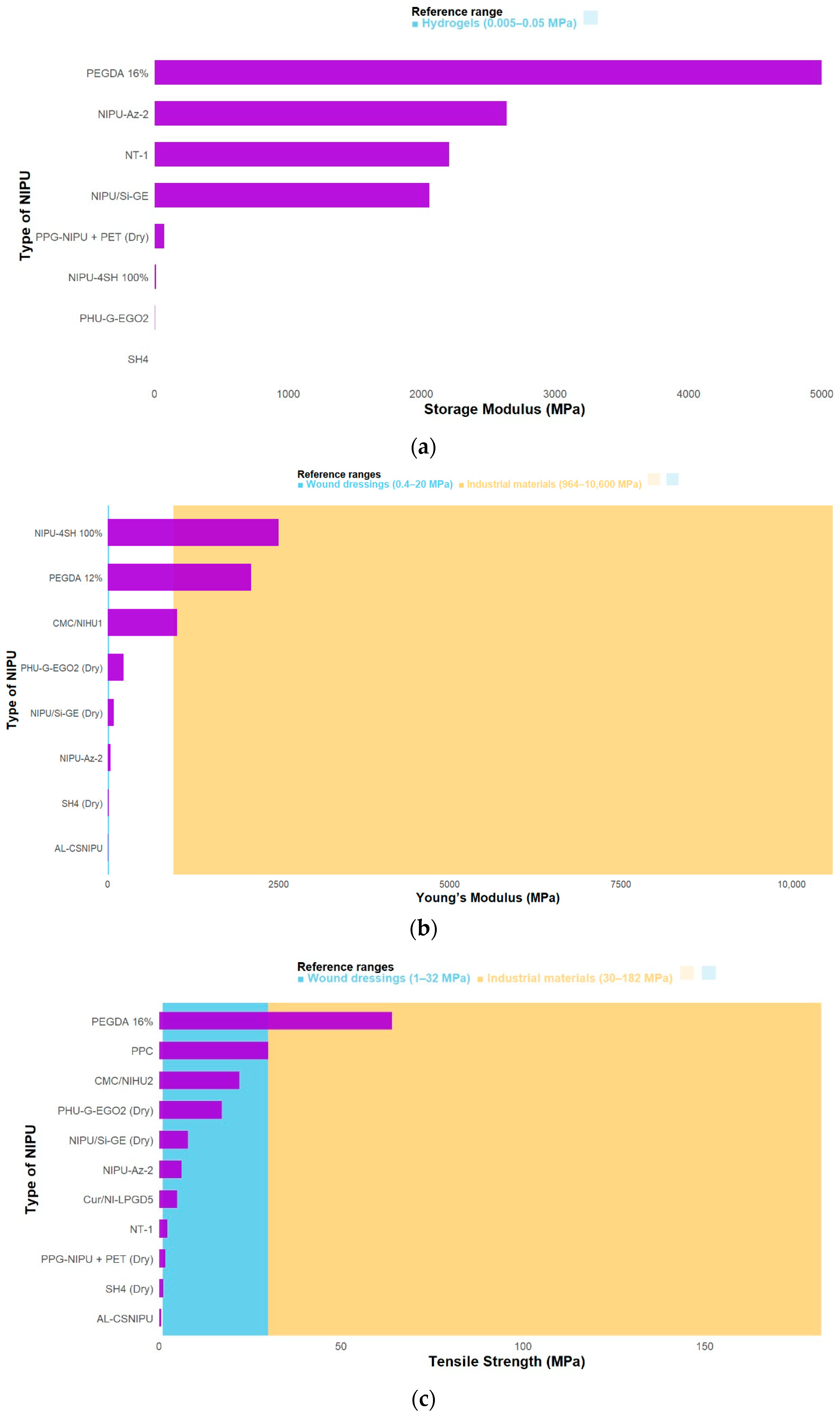

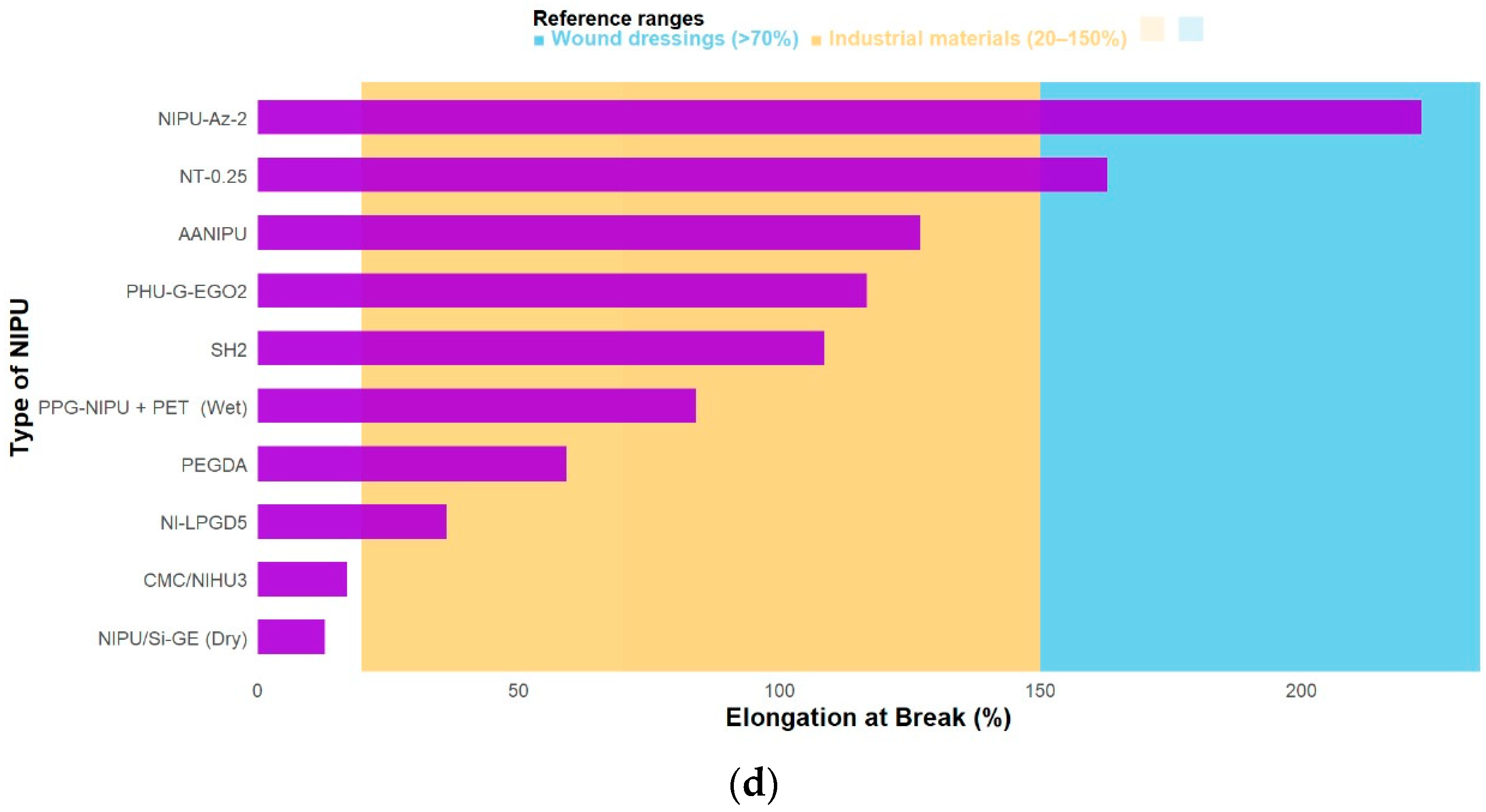

3.3. Mechanical Properties of Functionalized NIPUs

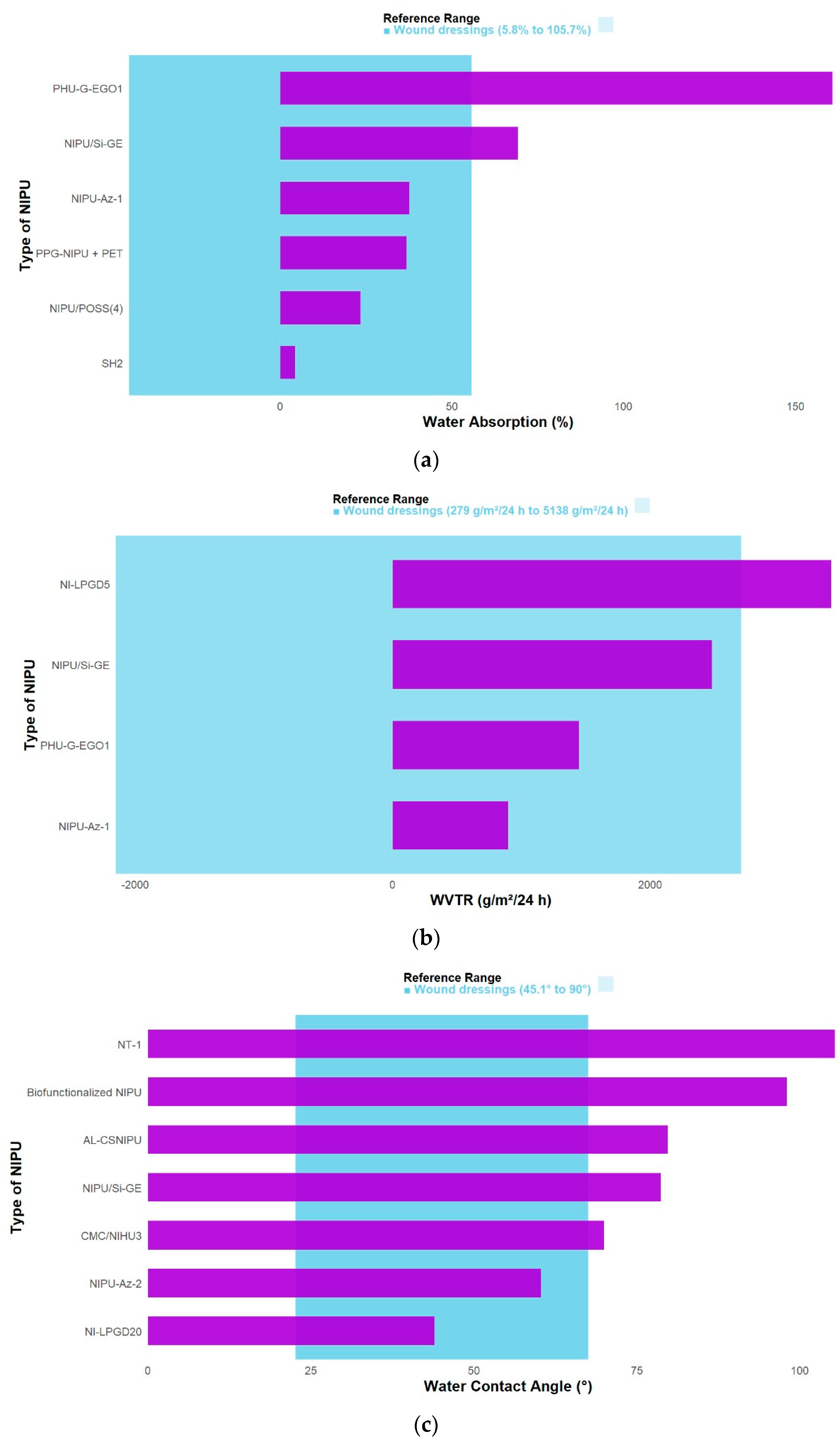

3.4. Physical Properties of Functionalized NIPUs

3.5. Biologicals Properties of Functionalized NIPUs

3.6. Main Applications and Results of Functionalized NIPUs

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Prasannatha, B.; Rao, B.N.; Konda Reddy, K.; Padala, C.; Manavathi, B.; Jana, T. Biodegradable and Biocompatible Nonisocyanate Polyurethanes Synthesized from Bio-Derived Precursors. Polymer 2024, 309, 127446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami, Z.; Kabiri, K.; Zohuriaan-Mehr, M.J. Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Thermoset Based on a Bio-Resourced Star-Shaped Epoxy Macromonomer in Comparison with a Cyclocarbonate Fossil-Based Epoxy Resin: A Preliminary Study on Thermo-Mechanical and Antibacterial Properties. J. CO2 Util. 2019, 34, 558–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, S.F.; Nondonfaz, A.; Aqil, A.; Pierrard, A.; Hulin, A.; Delierneux, C.; Ditkowski, B.; Gustin, M.; Legrand, M.; Tullemans, B.M.E.; et al. Design, Manufacturing and Testing of a Green Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Prosthetic Heart Valve. Biomater. Sci. 2024, 12, 2149–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oladzadabbasabadi, N.; Abraham, B.; Ghasemlou, M.; Ivanova, E.P.; Adhikari, B. Green Synthesis of Non-Isocyanate Hydroxyurethane and Its Hybridization with Carboxymethyl Cellulose to Produce Films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 276, 133617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaliya, J.D.; Kutcherlapati, S.N.R.; Dhore, N.; Punugupati, N.; Sunkara, K.L.; Misra, S.; Joshi, S.S.K. Soybean Oil-Derived, Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane-TiO2 Nanocomposites with Enhanced Thermal, Mechanical, Hydrophobic and Antimicrobial Properties. RSC Sustain. 2025, 3, 1434–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Cao, H.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Su, C.; Lv, X.; Zhao, J.; Qin, P.; Cai, D. Fabrication of Ultraviolet Resistant and Anti-Bacterial Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes Using the Oligomers from the Reductive Catalytic Fractionated Lignin Oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 193, 116213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-González, M.; Valero, M.F.; Díaz, L.E. Physicochemical and Mechanical Properties of Non-Isocyanate Polyhydroxyurethanes (NIPHUs) from Epoxidized Soybean Oil: Candidates for Wound Dressing Applications. Polymers 2024, 16, 1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Wu, G.; Chen, J.; Huo, S.; Jin, C.; Kong, Z. Synthesis and Properties of POSS-Containing Gallic Acid-Based Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes Coatings. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 121, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H.; Yeganeh, H. Soybean Oil-Derived Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes Containing Azetidinium Groups as Antibacterial Wound Dressing Membranes. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 142, 110142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aduba, D.C.; Zhang, K.; Kanitkar, A.; Sirrine, J.M.; Verbridge, S.S.; Long, T.E. Electrospinning of Plant Oil-Based, Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes for Biomedical Applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 46464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Pathak, J.L.; Feng, W.; Wu, W.; Yang, C.; Wu, L.; Zheng, H. Fabrication and Characterization of Photosensitive Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane Acrylate Resin for 3D Printing of Customized Biocompatible Orthopedic Surgical Guides. Int. J. Bioprint. 2023, 9, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Xia, X.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Z.; Lei, F.; Tan, X.; Yu, D.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, H. Thermoresponsive Behavior of Non-Isocyanate Poly(Hydroxyl)Urethane for Biomedical Composite Materials. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2022, 5, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, J.; Pielichowski, K. Sustainability of Nonisocyanate Polyurethanes (NIPUs). Sustainability 2024, 16, 9911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurén, I.; Farzan, A.; Teotia, A.; Lindfors, N.C.; Seppälä, J. Direct Ink Writing of Biocompatible Chitosan/Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane/Cellulose Nanofiber Hydrogels for Wound-Healing Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 259, 129321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayung, M.; Ghani, N.A.; Hasanudin, N. A Review on Vegetable Oil-Based Non Isocyanate Polyurethane: Towards a Greener and Sustainable Production Route. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 9273–9299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.; Wen, Y.F.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.P.; Xie, X.L. Modifying Poly(Propylene Carbonate) with Furan-Based Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 41, 1069–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, D.; Bakhshi, H.; Rogg, K.; Fuhrmann, E.; Wieland, F.; Schenke-Layland, K.; Meyer, W.; Hartmann, H. Green Chemistry for Biomimetic Materials: Synthesis and Electrospinning of High-Molecular-Weight Polycarbonate-Based Nonisocyanate Polyurethanes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 39772–39781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, F.; Wan, T.; Kong, L.; Xu, B.; Sun, M.; Wang, B.; Liang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhao, X. Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane-Co-Polyglycolic Acid Electrospun Nanofiber Membrane Wound Dressing with High Biocompatibility, Hemostasis, and Prevention of Chronic Wound Formation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, J.J.; Wang, P.; Mellor, W.M.; Hwang, H.H.; Park, J.H.; Pyo, S.H.; Chen, S. 3D Printable Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes with Tunable Material Properties. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 4665–4674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pilar Maya, M.; Torres, S.; Gartner, C. Synthesis and Surface Modification of Sunflower Oil-Based Non-Isocyanate Polyurethane: Physicochemical and Antibacterial Properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babaahmadi, M.; Yeganeh, H. Antibacterial Polyhydroxyurethane-Gelatin Wound Dressings with In Situ-Generated Silver Nanoparticles or Hyperthermia Induced by Near-Infrared Light Absorption. J. Polym. Environ. 2024, 32, 4282–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, P.; Yeganeh, H.; Omrani, I.; Babaahmadi, M. Gelatin Modified Nonisocyanate Polyurethane/Siloxane Functionalized with Quaternary Ammonium Groups as Antibacterial Wound Dressing Membrane. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierrard, A.; Melo, S.F.; Thijssen, Q.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Lancellotti, P.; Oury, C.; Detrembleur, C.; Jérôme, C. Design of 3D-Photoprintable, Bio-, and Hemocompatible Nonisocyanate Polyurethane Elastomers for Biomedical Implants. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 1810–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, S.K.; Sreedharan, S.; Singh, H.; Khan, M.; Tiwari, K.; Shiras, A.; Smythe, C.; Thomas, J.A.; Das, A. Mitochondria Targeting Non-Isocyanate-Based Polyurethane Nanocapsules for Enzyme-Triggered Drug Release. Bioconjugate Chem. 2018, 29, 3532–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tam, E.K.W.; Chong, N.X.; Choong, P.; Sana, B.; Seayad, A.M.; Jana, S.; Seayad, J. Phosphate Functionalized Nonisocyanate Polyurethanes with Bio-Origin, Water Solubility and Biodegradability. Green Chem. 2023, 26, 1007–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowczan, A.; Łukaszewska, I.; Pielichowski, K. Thermal Degradation of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2024, 149, 10885–10899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgil, D.; Barak, S. Mesquite Gum (Prosopis Gum): Structure, Properties & Applications—A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 159, 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palácio, S.B.; Penello, S.O.; Hodel, K.V.S.; Barbosa, W.T.; Reis, G.A.; Machado, B.A.S.; Godoy, A.L.P.C.; Tavares, M.I.B.; Mahnke, L.C.; Viana Barbosa, J.D.; et al. Commercial, Non-Commercial and Experimental Wound Dressings Based on Bacterial Cellulose: An In-Depth Comparative Study of Physicochemical Properties. Fibers 2025, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, E.; Liu, H.; Secord, T.; Laflamme, S.; Rivero, I.V. Flexible Shape Memory Structures with Low Activation Temperatures through Investigation of the Plasticizing Effect. Mater. Res. Express 2025, 12, 055310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, G.; Preuschen, J. Hydrogel Pressure Sensitive Adhesives for Use as Wound Dressings. European Patent Application EP 1 051 983 A1, 6 November 1999. published 15 November 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Modern Building Alliance. Physical Properties of Polyurethane Insulation Safe and Sustainable Construction with Polymers; Australian Modern Building Alliance: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Li, C.; Wang, Q. A Critical Review on Performance and Phase Separation of Thermosetting Epoxy Asphalt Binders and Bond Coats. Construction and Building Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, S.; Keul, H.; Moeller, M. Synthesis of Azetidinium-Functionalized Polymers Using a Piperazine Based Coupler. Macromolecules 2013, 46, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chang, Y.; Qiu, S.; Liu, H.; Zhao, J.; Gao, J. High Mechanical Energy Storage Capacity of Ultranarrow Carbon Nanowires Bundles by Machine Learning Driving Predictions. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res. 2023, 4, 2300112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.C.; Mai, Y.W. Thermodynamics at the Nanoscale: A New Approach to the Investigation of Unique Physicochemical Properties of Nanomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2014, 79, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.; Yaqoob, M.; Aggarwal, P. An Overview of Biodegradable Packaging in Food Industry. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Fu, P.; Li, W.; Xiao, L.; Chen, J.; Nie, X. Influence of Crosslinking Density on the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Plant Oil-Based Epoxy Resin. RSC Adv. 2022, 12, 23048–23056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djafari Petroudy, S.R. Physical and Mechanical Properties of Natural Fibers. In Advanced High Strength Natural Fibre Composites in Construction; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safta, D.A.; Bogdan, C.; Iurian, S.; Moldovan, M.L. Optimization of Film-Dressings Containing Herbal Extracts for Wound Care—A Quality by Design Approach. Gels 2025, 11, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, D.R.; Fung, S.S.; Sieracki, J.M. Wound Dressing with Multiple Adhesive Layers. U.S. Patent US 11,007,086 B2, 18 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, E.N. Engineering Termoplastics-Materials, Properties, Trends. In Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook: Processing, Materials, and Applications: Second Edition; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboughaly, M.; Babaei-Ghazvini, A.; Dhar, P.; Patel, R.; Acharya, B. Enhancing the Potential of Polymer Composites Using Biochar as a Filler: A Review. Polymers 2023, 15, 3981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Zhao, K.; Cao, P.; Cao, L.; Liao, H.; Tang, X. Molecular Simulation Study on the Impact of a Cross-Linked Network Structure on the Tensile Mechanical Properties of PBT Substrates. Materials 2025, 18, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, J. Ciencia de Materiales Aplicaciones en Ingeniería; Alfaomega Grupo Editor: Mexico City, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Ding, J.; Wang, B.; Zhuang, Y.; Huang, Z. Synthesis and thermal degradation study of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (Poss) modified phenolic resin. Polymers 2021, 13, 1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džunuzović, E.; Vodnik, V.; Jeremić, K.; Nedeljković, J.M. Thermal properties of PS/TiO2 nanocomposites obtained by in situ bulk radical polymerization of styrene. Mater. Lett. 2009, 63, 908–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yu, P.; Dong, S. The influence of crosslink density on the failure behavior in amorphous polymers by molecular dynamics simulations. Materials 2016, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gooranorimi, A.; Mousavifard, S.M.; Mohseni, M.; Yahyaei, H.; Makki, H. Effective Cross-Link Density as a Metric for Structure–Property Relationships in Complex Polymer Networks: Insights from Acrylic Melamine Systems. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 9034–9044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martau, G.A.; Mihai, M.; Vodnar, D.C. The use of chitosan, alginate, and pectin in the biomedical and food sector-biocompatibility, bioadhesiveness, and biodegradability. Polymers 2019, 11, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebere Onyekachi, O. Mechanical and Water Absorption Properties of Polymeric Compounds. Am. J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2019, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Bora, M.; Gee, R.; Dauskardt, R.H. Water Vapor Transmission Rate Measurement for Moisture Barriers Using Infrared Imaging. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 308, 128289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Neto, R.J.; Genevro, G.M.; Paulo, L.d.A.; Lopes, P.S.; de Moraes, M.A.; Beppu, M.M. Characterization and in Vitro Evaluation of Chitosan/Konjac Glucomannan Bilayer Film as a Wound Dressing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 212, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi-Firoozjah, R.; Parandi, E.; Heydari, M.; Kolahdouz-Nasiri, A.; Bahraminejad, M.; Mohammadi, R.; Rouhi, M.; Garavand, F. Betalains as Promising Natural Colorants in Smart/Active Food Packaging. Food Chem. 2023, 424, 136408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.Y. Definitions for Hydrophilicity, Hydrophobicity, and Superhydrophobicity: Getting the Basics Right. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 686–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsart, M.; Van Vlierberghe, S.; Dubruel, P.; Mignon, A. Commercial Wound Dressings for the Treatment of Exuding Wounds: An in-Depth Physico-Chemical Comparative Study. Burn. Trauma 2022, 10, tkac024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Mahanwar, P. A Brief Discussion on Advances in Polyurethane Applications. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2020, 3, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebda, E.; Pielichowski, K. Biomimetic Polyurethanes in Tissue Engineering. Biomimetics 2025, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, A.M.S.; Silva, G.M.C.; Coutinho, J.A.P.; Pereira, J.F.B. Unravelling the molecular interactions behind the formation of PEG/PPG aqueous two-phase systems. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 7308–7317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stachak, P.; Łukaszewska, I.; Hebda, E.; Pielichowski, K. Recent advances in fabrication of non-isocyanate polyurethane-based composite materials. Materials 2021, 14, 3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, J.; Lehocký, M.; Humpolíček, P.; Sáha, P. HaCaT Keratinocytes Response on Antimicrobial Atelocollagen Substrates: Extent of Cytotoxicity, Cell Viability and Proliferation. J. Funct. Biomater. 2014, 5, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaou, N.; Stavropoulou, E.; Voidarou, C.; Tsigalou, C.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Towards Advances in Medicinal Plant Antimicrobial Activity: A Review Study on Challenges and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10993-5; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices Part 5: Tests for In Vitro Cytotoxicity. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- Rybczyńska-Tkaczyk, K.; Grenda, A.; Jakubczyk, A.; Kiersnowska, K.; Bik-Małodzińska, M. Natural Compounds with Antimicrobial Properties in Cosmetics. Pathogens 2023, 12, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wahab, W.A.A. Review of research progress in immobilization and chemical modification of microbial enzymes and their application. Microb. Cell Factories 2025, 24, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krukiewicz, K.; Gniazdowska, B.; Jarosz, T.; Herman, A.P.; Boncel, S.; Turczyn, R. Effect of immobilization and release of ciprofloxacin and quercetin on electrochemical properties of poly(3,4-ethylenedioxypyrrole) matrix. Synth. Met. 2019, 249, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drożdż, K.; Gołda-Cȩpa, M.; Chytrosz-Wróbel, P.; Kotarba, A.; Brzychczy-Włoch, M. Improving Biocompatibility of Polyurethanes Applied in Medicine Using Oxygen Plasma and Its Negative Effect on Increased Bacterial Adhesion. Int. J. Biomater. 2024, 5102603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dai, D.; Xie, H.; Li, D.; Xiong, G.; Zhang, C. Biological Effects, Applications and Design Strategies of Medical Polyurethanes Modified by Nanomaterials. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 6791–6819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraris, S.; Cochis, A.; Cazzola, M.; Tortello, M.; Scalia, A.; Spriano, S.; Rimondini, L. Cytocompatible and anti-bacterial adhesion nanotextured titanium oxide layer on titanium surfaces for dental and orthopedic implants. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2019, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshel, S.H.; Azhdadi, S.N.K.; Asefnejad, A.; Sadraeian, M.; Montazeri, M.; Biazar, E. The relationship between cellular adhesion and surface roughness for polyurethane modified by microwave plasma radiation. Int. J. Nanomed. 2011, 6, 641–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyab, V.; Hussain, Z.; Noor, A.; Qayyum, H.; Shafique, H. Graphene Oxide-Silver Composite Synthesis by Pulsed Laser Ablation in Liquid: Morphology Dependent Antibacterial and Electrochemical Properties. Bionanoscience 2025, 15, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N. In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization Methods for Evaluation of Modern Wound Dressings. Pharmaceutics 2022, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwalla, A.; Ahmed, W.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.; Rizvi, T.A.; Khan, M.; Zaneldin, E. Characteristics and Key Features of Antimicrobial Materials and Associated Mechanisms for Diverse Applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çetin, Y. Assessing the Toxic Potential of New Entities: The Role of Cytotoxicity Assays. In Cytotoxicity-A Crucial Toxicity Test for In Vitro Experiments; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oeveren, W. Obstacles in Haemocompatibility Testing. Scientifica 2013, 2013, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zakharkin, S.O.; Kim, K.; Bartolucci, A.A.; Page, G.P.; Allison, D.B. Optimal Allocation of Replicates for Measurement Evaluation Studies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2006, 4, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himanen, L.; Geurts, A.; Foster, A.S.; Rinke, P. Data-Driven Materials Science: Status, Challenges, and Perspectives. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severino, M.I.; Freitas, C.; Pimenta, V.; Nouar, F.; Pinto, M.L.; Serre, C. Cost Estimation of the Production of MIL-100(Fe) at Industrial Scale from Two Upscaled Sustainable Synthesis Routes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2025, 64, 2708–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Znidar, D.; Dallinger, D.; Kappe, C.O. Practical Guidelines for the Safe Use of Fluorine Gas Employing Continuous Flow Technology. ACS Chem. Heal. Saf. 2022, 29, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | NIPUs | Synthesis Technique | Modification | Modification Technique | Form of the Material | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonates | Amines | Chemistry | Physics | ||||

| [5] | Cyclic carbonated soybean oil (CSBO) (from ESBO). | Ethylenediamine (EDA). | The synthesis was carried out through the reaction of CO2 with epoxidized soybean oil (ESBO) in a high-pressure reactor. In this process, 250 g of ESBO and tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB, 8.8 wt% relative to ESBO) were added to the reactor, and the mixture was heated to 120 °C under continuous stirring. CO2 was then introduced into the reactor at a constant pressure of 20 bar, maintained for 24 h. After completion of the reaction, a light brown viscous oil was collected at 60–70 °C. | TiO2 nanoparticles (TNPs). | N/A | CSBO was weighed, and stannous octoate was added as a catalyst at room temperature. Subsequently, different concentrations of nanoparticles (NT-X, where X = 0%, 0.25%, 0.5%, and 1%) were incorporated into the formulation. The mixture was subjected to ultrasonication for 30 min, followed by the addition of a solvent mixture to reduce the viscosity of the NT-X dispersions. Finally, the curing agent (EDA) was added at 13 wt% relative to CSBO and thoroughly mixed. The films were cast into silicone molds and cured at 80 °C for 24 h, followed by an additional 4 h at 110 °C. | Films |

| [9] | Cyclic carbonated soybean oil (CSBO). | Tetraethylenepentamine (TEPA). | In a three-neck round-bottom flask, equimolar amounts of CSBO (6.00 g) and TEPA (1.64 g) (1:1 molar ratio of primary amine to cyclic carbonate) were introduced, followed by the addition of DMF (8 mL) to adjust the solid content to 50 wt%. The reaction temperature was raised to 70 °C under continuous stirring and maintained for 24 h. The resulting mixture was then transferred to a Teflon mold and placed in an oven at 90 °C for 12 h to allow solvent evaporation. The obtained membranes were subsequently immersed in 70% ethanol solution for 6 h to remove residual chemicals. | N/A | Azetidinium groups. | The temperature was reduced to room conditions and an appropriate amount of ECH (1.24 g or 2.48 g) was added to obtain a molar ratio of between ECH and the secondary amine groups of TEPA was 1:1 for NIPU-Az-1 and 2:1 for NIPU-Az-2. (ECH converts the secondary amine into an azetidinium cation, a positively charged group bound to the polymer). After heating the mixture at 90 °C for 12 h, polyurethane membranes functionalized with azetidinium groups were obtained. | Membranes |

| [8] | Thegallic acid-based cyclic carbonate. | Diamines: ethylenediamine (EDA), hexamethylene diamine (HMDA), isophorone diamine (IPDA) and Jeffamine (D230). | The reaction was carried out involving a gallic acid–based cyclic carbonate and the functionalizing compound, which were dissolved in DMF. Subsequently, different amines were added, and the mixture was stirred for 5 min to ensure homogeneity. The resulting solution was cast onto tin or Teflon plates and subjected to vacuum drying in an oven at 100 °C for 8 h, yielding dry coatings. | Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS). | N/A | The synthesis of the functionalization was performed through the incorporation of variable proportions of epoxy-functionalized POSS into the NIPU formulation. Both compounds were dissolved in the same DMF phase and underwent the same thermal curing process, thus obtaining NIPU/POSS coatings. | Coatings |

| [3] | Poly(propylene glycol) bis(cyclic carbonate) (PPG bisCC) and poly(tetra hydrofuran) bis(cyclic carbonate) (PTHF bisCC). | 4-((4-aminocyclo hexyl)methyl)-cyclohexanamine (MBCHA) N′,N′-bis(2-aminoethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine (TAEA). | PPG bisCC (468 g/mol, 1 equivalent) or PTHF bisCC (850 g/mol, 1 equivalent) was mixed with 4-((4-aminocyclohexyl)methyl)cyclohexanamine (MBCHA, 0.2 equivalents) and N′,N′-bis(2-aminoethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine (TAEA, 0.53 equivalents), and the mixture was magnetically stirred at 40 °C for 15 min without the use of any catalyst. The solution was then poured into a flat Teflon mold (0.5 × 5 × 25 mm) and subjected to thermal curing in an oven at 70 °C for 24 h. | N/A | Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) mesh. | A PET mesh (Dacron 3002, Surgical Mesh™) was placed in the mold to improve the mechanical strength of the valves. Subsequently, the liquid-state polymer was injected into the mold and allowed to polymerize and solidify at high temperature (24 h at 70 °C). | Patches |

| [4] | Propylene carbonate (PC) | Ethylenediamine (EDA) | PC (30.87 g, 0.30 mol) was weighed into a beaker, and EDA (9.02 g, 0.15 mol) was added dropwise to the PC solution. No solvent or catalyst was used. The mixture was magnetically stirred for 3 h at room temperature, and the resulting white solid was dried at 60 °C in a vacuum oven for 24 h. The obtained product was then ground with a kitchen grinder to achieve a particle size of 120 μm. | N/A | Carboxymethyl cellulose | Glycerol was used as a plasticizer in different proportions (90:10, 80:20, and 70:30) by using a solution casting method. A solution was prepared by adding 1 g of glycerol to 100 mL of water, followed by the gradual addition of CMC under stirring at 90 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, dry NIHU powder was incorporated at 10, 20, and 30 wt%. Stirring was maintained for an additional 30 min at 90 °C, after which the dispersion was cooled to room temperature while maintaining agitation. The mixture was then subjected to ultrasonication for 4 min at 70% amplitude. Finally, 15 mL of the dispersion was transferred to a Petri dish and dried at room temperature for 48 h. | Films |

| [11] | Propylene carbonate (PC) | Isophorone diamine (IPDA) | Propylene carbonate (30.00 g, 0.29 mol) was added to a 250 mL flask equipped with mechanical stirring and a reflux condenser. The mixture was heated to 120 °C, and isophorone diamine (27.52 g, 0.16 mol) was added dropwise under stirring for 8–10 h. The reaction product was cooled, dissolved in 100 mL of dichloromethane, and stirred for 1.5 h, after which 300 mL of n-hexane was added to extract the product. The resulting white precipitate was washed with n-hexane to completely remove the ammonium byproduct and any unreacted triethylamine. Finally, the mixture was dried under vacuum at 60 °C to eliminate residual n-hexane. | N/A | Polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA)Methacryloyl chloride (MAC) | The NIPU prepolymer (60.00 g, 0.16 mol) and triethylamine (36.65 g, 0.36 mol) were dissolved in 200 mL of anhydrous dichloromethane and cooled to 0 °C in an ice bath. A solution of acryloyl chloride (38.71 g, 0.37 mol) in 100 mL of anhydrous dichloromethane was then added dropwise under stirring. The reaction mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature, and after 12 h, triethylamine hydrochloride salts were filtered off. Subsequently, a saturated sodium bicarbonate solution was added. PTZ (0.05 wt%), the organic solvent was removed by rotary evaporation to obtain NIPUMA. A NIPUA solution containing the NIPUMA monomer, TEGDA, PEGDA, and 1 wt% of the photoinitiator CQ was then prepared, stirred at 50 °C and 400 rpm for 15 min, and printed. | Resin |

| [16] | Furan-based bis(cyclic carbonate) (FBC) | 1,2-ethanediamine (EDA) and 1,6-hexanediamine (HDA) | A 100 mL three-neck flask was equipped with a mechanical stirring device and linked with a Schlenk line. The flask was then charged with 10 mmol FBC and 10 mmol diamines. The mixture was allowed to react at 60 °C for 20 min, then 80 °C for 1 h, and 100 °C for another 1 h under an inert gas atmosphere. | N/A | (Poly(propylene carbonate) | Before blending, PPC was dried in a vacuum drying oven at 30 °C for 24 h. Then, it was melting blended with furan-based NIPUs by an internal mixer under 110 °C for 10 min. The weight ratio of PPC/NIPU was set as 97.5/2.5, 95/5, 92.5/7.5, 90/10, and 85/15. To prepare the sample sheets for measurements, PPC and its blends were compression-molded at 110 °C under 10 MPa. | Sheet |

| [18] | Ethylene carbonate (EC) | 1,6-hexanediamine (1,6-HDA) | EC and 1,6-HAD were used as raw materials for the synthesis of BHHDC by heating the reaction at 80 °C for 2 h and then at 96 °C for another 2 h. Subsequently, 180 g of deionized water was added, and the reaction was maintained at 80 °C for 30 min before cooling the mixture to room temperature. This BHHDC was then used with PEG1000 for the synthesis of NIPU, employing SnCl2·2H2O as a catalyst. The reaction temperature was 220 °C under a pressure of 600 Pa. | N/A | Low-molecular-weight polyglycolic acid diol (LPGD) and curcumin | LPGD171 and NIPU were used as raw materials for NI-LPGD synthesis, with HFIP serving as the solvent. The reaction was conducted at a temperature of 60 °C for 30 min. Among the NI-LPGD, the mass fraction of LPGD171 was from 5 wt% to 20 wt%, and they were named NI-LPGD5, NI-LPGD10, NI-LPGD15 and NI-LPGD20. | Membranes |

| [17] | Polycarbonate diols (PCDLs) | 1,6-hexanodicarbamato (1,6-HDC) | They were synthesized by the transurethane reaction of PCDL and 1,6-HDC. PCDL (43.0 mmol), 1,6-HDC (43.0 mmol), and TBT (0.2–0.3 wt%) were added to a 100 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a condenser and a mechanical stirrer. The mixture was heated to 170 °C and mechanically stirred until a homogeneous solution was obtained. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was transferred to a vacuum oven and heated at 170 °C under dynamic vacuum. The product was dissolved in DMF (80 mL) at 70 °C, precipitated in methanol (2 L), and dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C overnight. Finally, an electrospinning process was carried out. | N/A | Rat tail collagen, type I (rCol I). | Collagen was extracted from rat tail tendons using an acid-based isolation method and lyophilized for long-term storage. Prior to biofunctionalization, the lyophilized collagen was solubilized in acetic acid (0.1 M) at a concentration of 0.1 mg/mL. The sheets were incubated in the collagen solution at 37 °C for 2 h, the excess solution was aspirated, and they were left to dry at 4 °C overnight. | Scaffolds |

| [19] | Trimethylolpropane monoallyl ether cyclic carbonate (TMPMEC) | Cadaverine (1,5-diaminopentane, >99%) | TMPMEC and cadaverine were mixed at a molar ratio of 2:1 in order to accommodate ring-opening conjugation with cadaverine’s two available primary amines. This mixture of TMPMEC and cadaverine was initially vortexed vigorously for 1 min and then heated (68°C for 15 min), during which it was also periodically vortexed. | N/A | Thiol-ene polymerization of alkene groups | Various molar ratios of thiol compounds were introduced to match the number of alkenyl groups in the diallyl-diurethane prepolymer. The mixtures were then heated at 78 °C for 5 min. Following this step, Darocur 1173® (2% v/v) was added, and the mixtures were stirred intermittently for an additional 5 min at 78 °C. | Slabs |

| [20] | Carbonated sunflower oil (CSFO) | Polyamine polyol (PAPO) | The CSFO and PAPO monomers were reacted at a molar ratio of 1:1.5, considering their functionality. After homogenization by mechanical stirring at 90 °C for 1–3 min, the viscous solution was poured into silicone molds and maintained at 90 °C for 24 h to promote crosslinking. | N/A | Acrylate Acid grafted LbL deposition of chitosan and alginate TTO | NIPU films were placed in Petri dishes containing a solution of BP dissolved in AA (0.5 mL, 0.2 M) and distilled water (0.5 mL). This system was exposed to UV light (365–415 nm) for 30 min. The samples were then thoroughly washed with NaOH solution followed by distilled water to remove any residues. The NIPU films with grafted AA (AANIPU) were vacuum-dried at room temperature until constant weight was achieved, after which a second treatment was carried out with AL-CS or TTO. A multilayer coating of cationic chitosan (CS) and anionic alginate (AL) was deposited onto the AANIPU films using the layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly method. Other treatment, AANIPU films were immersed in a TTO solution (50 wt%) for 24 h at 4 °C, using acetone as solvent. The samples were rinsed with acetone to remove excess TTO, washed with distilled water, and dried at room temperature until complete solvent evaporation. | Films |

| [21] | Poly(ethylene glycol) Bis-cyclic Carbonate (PEGC) | Triethylenetetramine | To a three-necked bottom flask equipped with a refluxing condenser, the requisite amounts of PEGC and TEDA (at a 1:1molar ratio) were added and stirred while being heated to 50 °C. Subsequently, a mixture of TETA and methanol was added to the flask in three equal parts over three half-hour intervals using a syringe, and the reaction was allowed to proceed for 4 h at 50 °C. After the reaction was completed, the condenser was removed from the reaction system, and the methanol was allowed to evaporate completely. | N/A | Gelatin Epoxidized Graphene Oxide (EGO) Ag NPs | EGO powder was added to a 50 mL beaker containing 15 mL of deionized water, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 3 h using a magnetic stirrer. The nanoparticles were dispersed in water using ultrasound for 10 min. Solutions were prepared with the specified amounts of GE, PHU, and BDDE in separate beakers, with 10 mL, 10 mL, and 5 mL of deionized water, respectively. This was then added to the EGO solution, stirred for 15 min with a magnetic stirrer, and subjected to ultrasound for 10 min. It was slowly poured into a silicone mold and kept at 40°C for 24 h, finally undergoing additional heat treatment in a vacuum oven at 80°C for 36 h. On the other hand, the PHU-G5 and PHU-G-EGO2 membranes were immersed in a beaker with silver nitrate solution (1% by weight) and left in the dark for 36 h. They were then removed and washed with plenty of distilled water. Finally, the membranes were dried at room temperature under vacuum. | Films |

| [22] | Cyclic carbonated soybean oil (CSBO) | N, N′-Dimethylethylenediamine (DMEDA) | NIPU-TA was synthesized by reacting CSBO and DMEDA, following the procedure described by Yeganeh et al. [22] (A round-bottomed flask was charged with CSBO (100.00 g, 0.29 mol), LiCl (1.20 g, 0.028 mol) and THF (80 mL). DMEDA (33.23 g, 0.377 mol) was then added to the flask and the resulting solution was stirred at room temperature. At the end of the reaction, the flask content was diluted with ethyl acetate and extracted twice with distilled water slightly acidified by adding hydrochloric acid. The organic layer was then separated and freed from dissolved water via treatment with dry sodium sulphate). | N/A | (3-chloropropyl) trimethoxysilane (CPTMS), (3-Glycidyloxypropyl) trimethoxysilane (GPTMS), Tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) and gelatin | A three-necked round-bottomed flask equipped with a condenser, a magnetic stirrer, a thermometer, and a nitrogen inlet was charged with 5.0 g NIPU-TA, 2.0 g CPTMS, and moisture-free DMF solvent. The reaction mixture was stirred at 85 °C for 48 h. Finally, the solvent was evaporated, and the final product was subjected to high vacuum in an oven at 80 °C. In a beaker equipped with a magnetic stirrer, 5.0 g of QMSiNIPU, 0.5 g of TEOS, and 1.5 g of GPTMS were completely dissolved in 10 mL of DMF at room temperature. Then, three drops of acetic acid and one drop of Sn(oct)2 were added to the solutio and was slowly poured into a silicone mold. This was placed in an oven at 80 °C for 12 h and then at 120 °C for 2 h. The GE solution with a concentration of 4 wt%. Then, the NIPU/Si was immersed in the as-prepared solution at the same temperature, and the reaction was continued for 12 h. Finally, the membrane was thoroughly washed multiple times with an ample amount of double-distilled water. The resulting film was then placed in a vacuum oven at 60 °C. | Membranes |

| [23] | Poly(propylene glycol)-bis(cyclic carbonate) (PPG bisCC) | 4,4’-methylenebis(cyclohexylamine) (MBCHA) | Was synthesized by the solvent- and catalyst-free polyaddition of poly(propyleneglycol)-bis(cyclic carbonate) (PPG bisCC, synthesized from a 380 g/mol PPG-diglydicylether precursor) with 4,4’-methylenebis(cyclohexylamine) (MBCHA) at 70 °C for 96 h, as already reported in the literature. | N/A | α-alkylidene cyclic carbonate (αCC) Thiol–ene reaction | Five grams of PPG-PHU were dissolved in dry DMF (20 mL) in a 100 mL round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer. After complete dissolution, αCC and 1,8-diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene (DBU) were added under an inert atmosphere and stirred for 24 h. The product was purified by three successive precipitations in diethyl ether, centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 10 min, 15 °C), redissolved in CHCl3, and finally dried under vacuum. For photochemical crosslinking, the αCC-modified NIPU containing pendant C=C bonds was mixed with polythiols (SH2, SH3, or SH4) and Irgacure 819, followed by UV irradiation to trigger the thiol–ene reaction. | Resin |

| [24] | Adipate bicarbonate or alkyl C10 diglycerol carbonate | 1,8-diaminooctane | For the synthesis of the polyurethane capsules, 83 mg (0.57 mmol) of 1,8-diaminooctane, 1.0 g of water, 1.0 mg of dye or doxorubicin and 6.0 mg sodium chloride were added to 7 g of cyclohexane containing 200 mg of Hypermer™ B246. For pre-emulsification, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 h at 1200 rpm. After that, the mini-emulsion was obtained by ultrasonication of the mixture for 3 min. An equimolar amount of bis carbonate moiety with respect to the amino monomer was dissolved in 4 g of the cyclohexane-dichloromethane mixture. To this, a catalytic amount of TEA was added. The reaction mixture was added in a dropwise manner to the above mentioned mini-emulsion dispersion, and the resulting mixture was left for stirring at room temperature 24 h. | N/A | Post-grafting of the nanocapsules with phosphonium ion | Briefly, 2.0 g of NIPU nanocapsule dispersion (solid content of 5.0 wt %), (5-carboxypentyl)triphenylphosphonium cation (0.1 g), and 4- dimethylaminopyridine (0.05 g) were dissolved in 10 mL of dry DCM. N-ethyl-N׳-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC.HCl) (0.08 g) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (1 mL) and added dropwise to the reaction mixture at 0 °C with stirring. The reaction mixture was allowed to for a8 h at room temperature, and then the nanocapsule solution was transferred into SDS water solution. The resulting dispersion was stirred at 1000 rpm for 2 h at room temperature. Subsequently, the reaction mixture wasultrasonicated for 10 min. This was left to stir overnight at 1000 rpm at room. | Nanocapsules |

| [25] | 4,4′-(((furan-2,5-diylbis(methylene)) bis(oxy)) bis (methylene)) bis(1,3-dioxolan-2-one) (FuBCC) and bis((2-oxo-1,3-dioxolan-4-yl)methyl) succinate (SuBCC) | 1,5-pentanediamine (cadaverine) | FuBCC (10.3 g, 31.5 mmol) or SuBCC (10.0 g, 31.5 mmol) was added into the reactor. The content was dissolved in anisole (30 mL), and diamine (3.218 g, 31.5 mmol) was added. The reactor was sealed, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 28 h at 70 °C. Finally, the reaction mixture was cooled down to room temperature and the excess anisole was decanted. The polymer was then dissolved in methanol (10 mL) and the polymer was precipitated from diethyl ether (20 mL). The process was repeated two more times. The polymer was dried under air and then under vacuum at 80 °C, giving poly(FuCa) and poly(SuCa) in yields above 90%. | N/A | Post polymerization functionalization of NIPUs by phosphorylation | To a solution of poly (FuCa) in GVL (25 mL), trichloroacetonitrile (TCAN) was added followed by dropwise addition of a solution of tetrabutylammonium dihydrogen phosphate (TBAP) in anhydrous acetonitrile (10 mL). After the addition, the reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 18 h at 50 °C. Upon completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed The solid was then dissolved in a small amount of methanol (10 mL) and re-precipitated using diethyl ether (50 mL). This step was repeated three times before drying under vacuum to obtain poly(FuCa)-P15. To a solution of poly(FuCa) in GVL (25 mL), TCAN was added followed by dropwise addition of a solution of TBAP in anhydrous acetonitrile (50 mL). After the addition, the reaction mixture was allowed to stir for 18 h at 50 °C. Upon completion of the reaction, the solvent was removed to obtain. The solid was then dissolved in a small amount of methanol (10 mL) and re-precipitated using diethyl ether (50 mL). This step was repeated three times before drying under vacuum to obtain poly(FuCa)-P50. | Multifunctional additives |

| Authors | Tensile s. | Young’s Modulus | Storage Modulus | Elongation at Break | Water Contact Angle | Absorption of Water | Water Vapor Transmission Rate WVTR | Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) | Thermal Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | NT-1: (↑) 2,28 ± 0,11 MPa | N/A | NT-1: (↑) 2207 MPa | NT-0.25: (↓) 162.9 ± 13.7% | NT-1: (↑) 105.4 ± 1.3° | N/A | N/A | NT-1: (↑) 2769 °C | NT-1: (↑) 480.42 °C |

| [9] | NIPU-Az-2: (↑) 6.21 ± 0.18 MPa | NIPU-Az-2: (↑) 41.1 ± 4.7 MPa | NIPU-Az-2: (↑) (2638.6 MPa) | NIPU-Az-2: (↓) 223 ± 7% | NIPU-Az-2: (↓) 60.34 ± 0.49° | NIPU-Az-1: (↑) 37.55% | NIPU-Az-1: (↑) 896 gr /m2/day | NIPU-Az-2: (↑) 60 °C | N/A |

| [8] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | NIPU/POSS (4): (↓) 23.38% | N/A | NIPU/POSS(3): (↑) 57.58 °C | NIPU/POSS(1): (↑) 388.22 °C |

| [3] | PPG-NIPU + PET (Dry): (↑) 1.79 ± 0.10 MPa | PPG-NIPU + PET (Dry): (↑) 73.00 ± 19.51 MPa | PPG-NIPU + PET (Wet): (↑) 83.9 ± 31.9% | N/A | PPG-NIPU + PET: (↑) 36.76% | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| [4] | CMC/NIHU2: (↓) 22.03 MPa | CMC/NIHU1: (↓) 1017.50 MPa | N/A | CMC/NIHU3: (↑) 17.2% | CMC/NIHU3: (↑) 70.0° | N/A | N/A | CMC/NIHU1: (↑) 162.7 °C | CMC/NIHU1: (↑) 207.9 °C |

| [11] | PEGDA 16%: (↑) 63.93 MPa | PEGDA 12% (↓) ± 2100 MPa | PEGDA 16%: (↑) < 5 GPa | (↑) 59.2% | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | PEGDA 20% (↑) 253.92 °C |

| [16] | >(↑) 30 MPa | N/A | N/A | PPC/NIPU 1c and PPC/NIPU 2c: Increase 10% | N/A | N/A | N/A | PPC/NIPU 2c: (↑) 34.5 °C | (↓) Lees than 200 °C |

| [18] | Cur/NI-LPGD5: (↑) 5.0 ± 0.4 MPa | N/A | N/A | (↓) 36.1 ± 5.5 % | NI-LPGD20: (↓) 44° | N/A | NI-LPGD5: 3405.0 ± 24.1 g/(m2·d) | NI-LPGD: (=) −40 °C | NI-LPG: (↑) 272 °C |

| [17] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Biofunctionalized NIPU: (↓) 98° ± 2 | N/A | N/A | NIPU-C: (↑) −41 °C | N/A |

| [19] | N/A | NIPU-4SH 100%: 2500 MPa | NIPU-4SH 100%: 1.2E Pa | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | NIPU:50%4SH–50%3SH: −0.73 °C. | 250 °C |

| [20] | AL-CSNIPU: (↓) 591.99 ± 130.3 kPa | AL-CSNIPU: (↑) 7400 ± 6.8 kPa | N/A | AANIPU: (↓) 127.0% ± 0.26 | AL-CSNIPU: (↓) 79.77° | N/A | N/A | AL-CSNIPU: (↓) −17.68 °C | T75% (°C) AL-CSNIPU: (↑) 380.28 |

| [21] | PHU-G-EGO2: Dry (↑) 17.22 ± 0.20 MPa | PHU-G-EGO2: Dry (↑) 233.37±9.04 MPa | PHU-G-EGO2: (↓) 2.74 MPa | PHU-G-EGO2: Dry (↓) 116.66 ± 12.67 % | N/A | PHU-G-EGO1: (↓) 160.87±2.25% | PHU-G-EGO1: (↓) 1.45 ± 0.02 (g 10–1 cm−2 day−1) | PHU-G-EGO2: (↓) −2.96 °C | N/A |

| [22] | NIPU/Si-GE (dry): (↑) 7.91 ± 0.74 MPa | NIPU/Si-GE (Dry): (↑) 88.90 ± 4.67 MPa | NIPU/Si-GE: (↑) 2.06 ± GPa | NIPU/Si-GE (Dry): (↓) 12.90 ± 3.27% | NIPU/Si-GE: (↓) 78.70 ± 1.92° | NIPU/Si-GE: (↑) 69.2 ± 2.1% | NIPU/Si-GE: (↓) 2.48 ± 0.04 (g 10−1 cm−2 d−1) | NIPU/Si-GE: (↑) 17.7 °C | N/A |

| [23] | SH4: Dry: 1.1 ± 0.1 MPa | SH4: Dry: 16.0 ± 1.0 MPa | SH4: 58,000 Pa | SH2: Dry: 108.6 ± 1.3% | N/A | SH2: 4.2 ± 0.5% | N/A | SH4: 42.4 °C | N/A |

| [24] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| [25] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | poly(FuCa)-P15: (↑) 21 °C | poly(FuCa)-P15: (↓) 183 °C |

| Authors | Antimicrobial Activity | Cell Viability | Biocompatibility | Hemocompatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | NT-1: 3 mm (E. coli MTCC 443) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| [9] | NIPU-Az-2: 100 ± 0% (E. coli) ATCC 25922 98.27 ± 0.41% (S. aureus) ATCC 6538 | 85% in L929 mouse fibroblast cells | N/A | N/A |

| [8] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| [3] | N/A | PPG-NIPU Human primary fibroblasts: 78.7 ± 4.5% (HUVECs): 87.4 ± 5.0% | N/A | Only PPG-NIPU and PTHF-NIPU: −0.2 ± 0.15% |

| [4] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| [11] | N/A | Murine fibroblast L929 > 90% | Bone Cells (MC3T3-E1) and Muscle Cells (C2C12) absence of an inhibitory effect | >0.5% |

| [16] | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| [18] | E. coli (ATCC 8739) was not significant S. aureus (ATCC 29213) > 90% | Murine fibroblast L929 > 98% | N/A | Hemostatic capacity in vivo: NI-LPGD5: (↓) 125 ± 37 mg |

| [17] | N/A | L929 > 70% | MeT-5A cells adverse effects on cell proliferation | N/A |

| [19] | N/A | Murine myoblasts: cell death (−3%) | N/A | N/A |

| [20] | S. aureus (ATCC 25923) AA NIPU and AA_TTO NIPU E. coli (ATCC 25922) AA_TTO NIPU | Detroit 551-CCL 110™ fibroblasts. AANIPU: 73.94 ± 6.59 % TTONIPU: 46.32 % ± 4.05 | N/A | N/A |

| [21] | Staphylococcus aureus (ATCC 6538): 92.8 ± 0.9% E coli: 89.3 ± 0.8 % | L929 mouse fibroblast cell: >80% | N/A | N/A |

| [22] | S. aureus, (ATCC 6538): 82.2% E. coli, (ATCC 25922): 50.2% | L929 mouse fibroblast cells: >80% | N/A | IPU/Si-GE: <0.5% |

| [23] | N/A | Human fibroblasts: >80% | N/A | PPG-NIPU con SH2: 0.3% |

| [24] | N/A | LN229 cells: Nontoxic up to 100 micromolar concentrations | N/A | N/A |

| [25] | Bacillus (ATCC 35889): poly(FuCa)-P50: 21.7 mm E. coli strain K12: poly(FuCa)-P50: 24.8 mm | Human keratinocyte HaCaT cells: >80% in most concentrations | N/A | N/A |

| Authors | Application Type | Study Design | Results Mainly | Methodological Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [5] | Eco-friendly adhesives Antimicrobial coatings Protective surfaces | In vitro | In summary, the TNP-incorporated NIPU exhibited improved thermal stability, mechanical properties, hydrophobicity, and antimicrobial effectiveness compared to bare NIPU, highlighting their potential for high-performance, environmentally friendly coatingapplications. | Incomplete evaluation of properties, due to the absence of Young’s modulus, water absorption, among other relevant tests. Since their intended use is as antimicrobial coatings, only two samples of each material type were tested to obtain an average value for each group (reduced number of replicas). And finally the antimicrobial assays showed limited results. |

| [9] | Wound dressing membranes | In vitro | The combination of hydrogen bonding, azetidinium ionic interactions, and C-N covalent crosslinking resulted in excellent dry strength, extensibility, and dimensional stability upon hydration. Therefore, these compounds are expected to protect injured tissue, maintain an optimal humid environment, and balance water retention and vapor transmission, for later use as an advanced wound dressing. | Absence of hemocompatibility assays, despite the material being intended for use as wound dressing membranes. Lack of chemical resistance testing, considering that the document reports that cyclic-carbonate-derived polyurethanes may exhibit insufficient mechanical properties and chemical resistance to aqueous acid and base solutions. Finally, the absence of in vivo assays prevents confirmation of their practical applicability. |

| [8] | Coatings | In vitro | Compared to NIPUs without POSS addition and those with POSS addition, NIPUs/POSS showed greater pencil hardness, water resistance and thermal stability, but lower adhesion; however, water absorption decreased and impact resistance and flexibility were affected only in NIPUs 3. | Lack of all biological evaluations, despite being a material derived from a renewable resource no assays on biocompatibility or biodegradability were performed. Assessment of mechanical properties remains incomplete, even though the material is intended for use as coatings. |

| [3] | Prosthetic heart valve | In vitro | The study lays the foundation for the future development of prosthetic heart valves made from NIPUs that are hemocompatible and hemodynamically competent, with good mechanical, elastic and stable properties, low hemolytic behavior, low platelet adhesion, resistance to calcification and excellent cytocompatibility with fibroblasts and endothelial cells. | No studies were conducted on chemical degradation resistance or biodegradation. In addition, the incorporation of the PET mesh may affect the interaction with blood components. There are difficulties in achieving optimal valve opening, durability tests are required. Finally, the absence of in vivo assays prevents confirmation of their practical applicability. |

| [4] | Packaging | In vitro | In particular, the incorporation of 20% (w/w) NIHU into CMC significantly improved the mechanical properties of resulting hybrids. The versatility and simplicity of the synthesis of NIHU and its hybridization with CMC, and the overall improvements in mechanical, thermal, and structural properties, these hybrids can make them promising candidates for many packaging applications. | Since this material is intended for packaging applications, biocompatibility and biodegradability tests were not performed. Furthermore, some properties were only compared to those of pure CMC, and not to those of pure NIHU. |

| [11] | 3D printing of custom biocompatible orthopedic surgical guides | In vitro In vivo | By adding 12% of PEGDA weight, it was possible to achieve maximum tensile and flexural strength, better elongation, thermal stability, resistance to acid/alkaline corrosion and excellent biocompatibility, taking into account cell viability, cell proliferation, among other things, with commercial materials it demonstrates lower toxicity and greater safety, which highlights its potential as a renewable medical-grade photocurable resin for 3D bioprinting and clinical applications. | Incomplete curing occurred during the process, and insufficient results were obtained regarding the corrosion resistance of NIPUA, since no quantitative measurements of mass change or residual mechanical properties were reported. |

| [16] | High-performance biodegradable polymeric materials | In vitro | Thanks to the abundant N―H and O―H groups in NIPU and the C=O groups of PPC, strong intermolecular interactions through hydrogen bonding were formed, and the glass transition temperatures, tensile strength, and elongation at break were significantly improved. In particular, by adding 5.0 wt% of NIPU, the tensile strength of the blends reached values above 30 MPa, approximately twice that of pure PPC and potentially equivalent to that of commercial polyethylene. This work demonstrates the preparation of high-performance, sustainable, and optimally biocompatible CO2-based biodegradable polymer materials. | Biological tests are lacking to confirm the intended purpose of the material as both biodegradable and biocompatible. |

| [18] | Wound dressing | In vitro In vivo | Based on our results, it can be concluded that the Cur/NI-LPGD5 nanofibrous membrane possesses excellent mechanical properties, water vapor transmittance, antibacterial properties, biocompatibility, and hemostasis ability; furthermore, it can effectively prevent chronic wound development and can serve as a wound dressing without requiring frequent replacement. | The presence of fluorine in the materials makes it necessary, in future studies, to identify a solvent with high polarity, volatility, and no hydroxyl groups for the synthesis process of the NI-LPGD membrane. A broader antibacterial evaluation against multidrug-resistant pathogens is also required, and finally, it is important to increase the number of experimental subjects in future investigations. |

| [17] | Substitute in cardiac tissue engineering | In vitro | Despite high water contact angles, the bare electrospun NIPU mats did not underperform in comparison to collagenfunctionalized mats because both fibroblasts and epithelial cells displayed good adhesion and proliferation. These in vitro investigations of the electrospun NIPU mats showed that they bear great potential in biomimetic cardiac scaffolds. | Further studies are needed to evaluate the mechanical properties of this material. Additionally, the use of a fluorinated solvent for solubilizing the NIPU represents a limitation, as it poses safety risks. A comparison with a commercially available TPU is necessary to confirm its functionality. Finally, the lack of in vivo testing prevents confirmation of its practical applicability. |

| [19] | Biomedical engineering (3D printable devices) | In vitro | The physical properties of NIPUs made from different combinations of linear and branched thiols were characterized, and they were shown to be tunable, cytocompatible, and printable by light-based 3D printing, making them novel, biocompatible, and mechanically flexible. The tunability and characteristics of the printable NIPU materials can be improved by using other types of biogenic polyamines, such as putrescine (C4 diamine), spermidine (triamine), and spermine (tetraamine), instead of cadaverine (C5 diamine). | The material exhibits low cell adhesion, which may represent both advantages and disadvantages, making it necessary to achieve a balance in this specific property. In addition, in vivo studies are required to demonstrate its potential use as 3D printable devices. |

| [20] | Antibacterial coating | In vitro | Its hydrophobic surface does not provide the antibacterial behavior expected for biomedical applications. A radical UV-initiated modification was performed to graft AA onto the surface and incorporate two antibacterial agents. Only TTO showed antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. aureus, but all surface modifications reduced the mechanical properties of the films. Further research is needed to understand the surface interactions between the different compounds and the nitrile protective film (NIPU). | The results indicate that the materials may potentially be considered cytotoxic. Moreover, contradictions were observed in some properties, such as the Tg versus surface stiffness and flexibility, which could not be fully understood due to experimental limitations. Finally, quantification of alginate and chitosan is necessary, since no antimicrobial activity was observed under the evaluated conditions. |

| [21] | Antibacterial wound dressings | In vitro | The strength of this sample was improved to 17.22 and 0.79 MPa (dry and wet conditions) by adding 2% by weight of EGO. The presence of Ag nanoparticles in the backbone of the dressings provided good antibacterial activity against various bacterial strains without severe cytotoxicity toward fibroblasts. This characteristic was enhanced to 90% bacterial elimination in samples containing Ag nanoparticles and EGO. | Lack of hemocompatibility tests, given that the material is developed as a wound dressing, and the absence of in vivo studies to evaluate its effectiveness. |

| [22] | Antibacterial wound dressing membrane | In vitro | The results indicated that the dressings exhibited excellent blood compatibility, attributed to the balanced concentration of QAS moieties within their structure and the appropriate level of water absorption, which effectively aids in the absorption of proteins involved in the blood clotting process. Overall, the properties of the developed dressings make them highly suitable for protecting low to moderate-exuding wounds, as well as infected wounds. | The results showed increased platelet adhesion, which highlights the need to achieve stability in this property. In addition, only limited activity against Gram-negative bacteria was observed, and finally, in vivo tests are still required to confirm the effectiveness of the material. |

| [23] | Applications in the cardiovascular field. | In vitro | The impact of the polythiols used on the thermomechanical properties of the final materials showed adequate values for various biomedical applications. In addition, in vitro biocompatibility/hemocompatibility tests, performed in contact of the materials with human fibroblasts, red blood cells, human platelets or platelet-poor plasma, showed biocompatible and hemocompatible profiles of the NIPUs, demonstrating the suitability of these materials for use in a biomedical context, including implants in contact with blood. | Use of solvents classified as “2” by the FDA, which raises safety concerns. Oxidation of the material was observed, leading to a “brown” coloration, which would prevent applications where strictly colorless materials are required. Finally, the absence of in vivo testing limits its potential application in the cardiovascular field. |

| [24] | Nanocapsules for Enzyme-Triggered Drug Release | In vitro | The drug carriers are synthesized using the inverse mini-emulsion technique by exploiting an in situ NH2–carbonate green reaction at the droplet interface. In addition, these nanocarriers can also be post grafted with organelle-specific targeting ligands for on-demand, target specific, drug delivery and bio-imaging. These nanocarriersoffer a promising novel therapeutic platform with high potential for biological imaging and drug delivery to fight cancer and other diseases. | Lack of evaluation of mechanical properties and stability tests. In addition, in vivo studies are needed to confirm their effectiveness. |

| [25] | Multifunctional additives in personal care/cosmetic applications. | In vitro | The resulting NIPUs were functionalized by mild and selective phosphorylation using tetrabutylammonium dihydrogen phosphate as the phosphate source, resulting in the production of NIPU phosphate monoesters with up to 50% phosphate content and showing the following features: (1) water solubility/dispersibility, (2) characteristic aerobic biodegradability, with degradation ranging from 56% to 75% within 28 days, absence of toxicity, with minimal or no inhibition of human keratinocyte HaCaT cell growth at concentrations up to 0.5 mg mL−1, absence of skin. | More exhaustive in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to fully understand the toxicity profile. The E factor results could be improved by optimizing reaction conditions and purification processes through solvent reduction and recycling. In vivo evaluation is necessary to determine both efficacy and non-toxicity. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Velez-Pardo, A.; Díaz, L.E.; Valero, M.F. Functionalization Strategies of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes (NIPUs): A Systematic Review of Mechanical and Biological Advances. Polymers 2025, 17, 3255. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243255

Velez-Pardo A, Díaz LE, Valero MF. Functionalization Strategies of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes (NIPUs): A Systematic Review of Mechanical and Biological Advances. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3255. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243255

Chicago/Turabian StyleVelez-Pardo, Ana, Luis E. Díaz, and Manuel F. Valero. 2025. "Functionalization Strategies of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes (NIPUs): A Systematic Review of Mechanical and Biological Advances" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3255. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243255

APA StyleVelez-Pardo, A., Díaz, L. E., & Valero, M. F. (2025). Functionalization Strategies of Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes (NIPUs): A Systematic Review of Mechanical and Biological Advances. Polymers, 17(24), 3255. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243255