Kinetic Analysis and Products Characterization of Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Tetra Pak Waste for Bio-Oil Production

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental Methods

2.1. Materials and Equipment

2.2. Performance Characterization

2.3. Data Processing

3. Results and Discussions

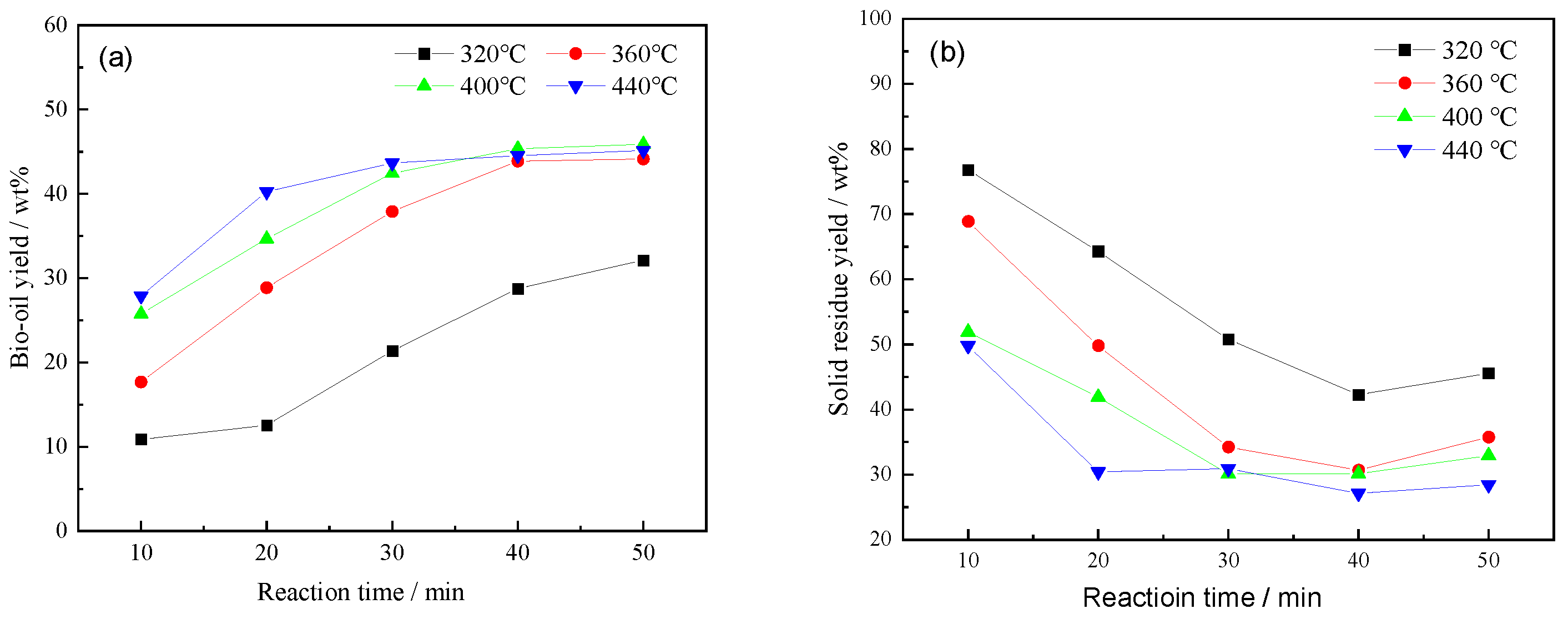

3.1. Effect of Temperature and Time on the Bio-Oil Yield

3.2. Boiling Point Distribution of Bio-Crude

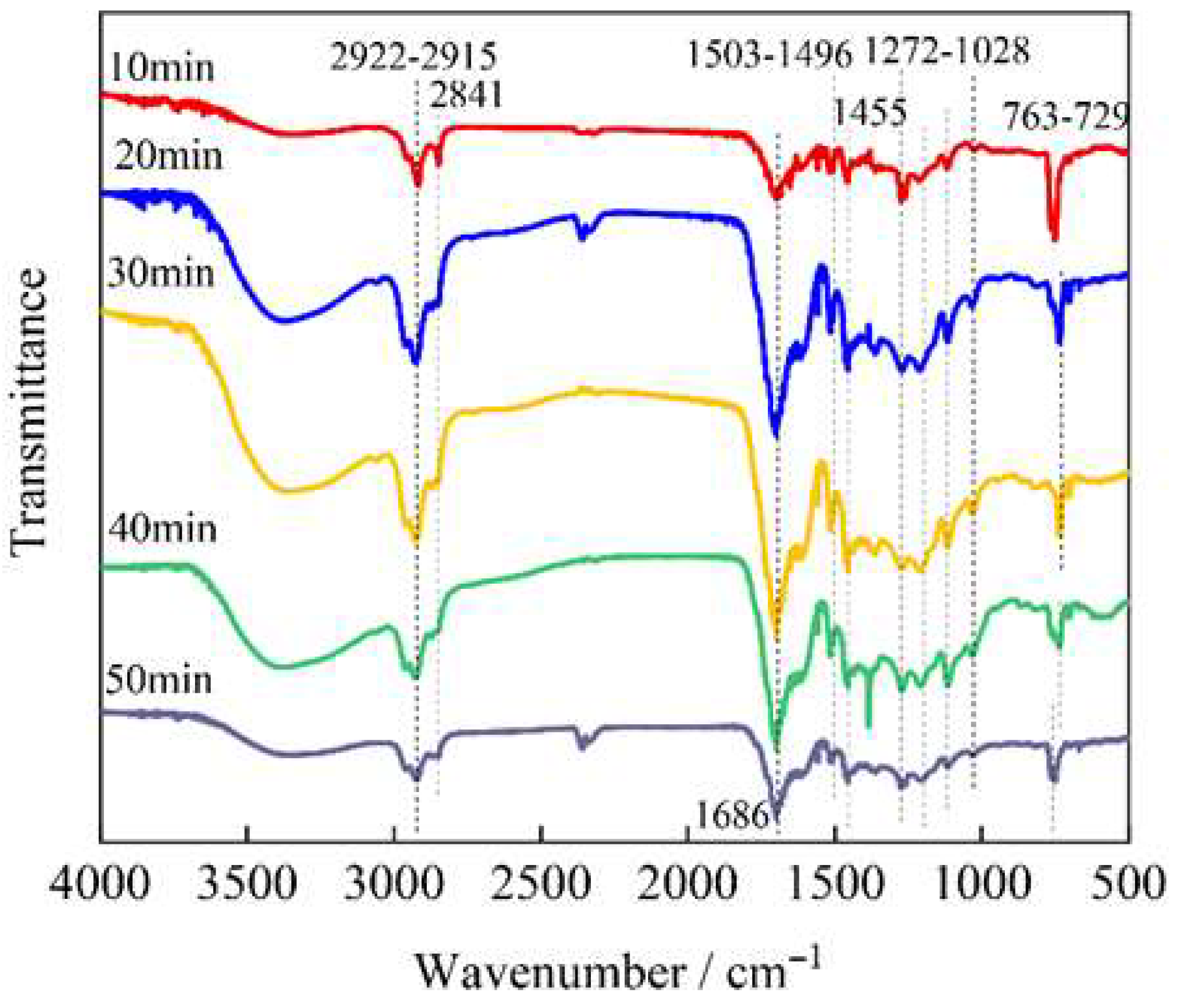

3.3. Infrared Analysis of Bio-Oil

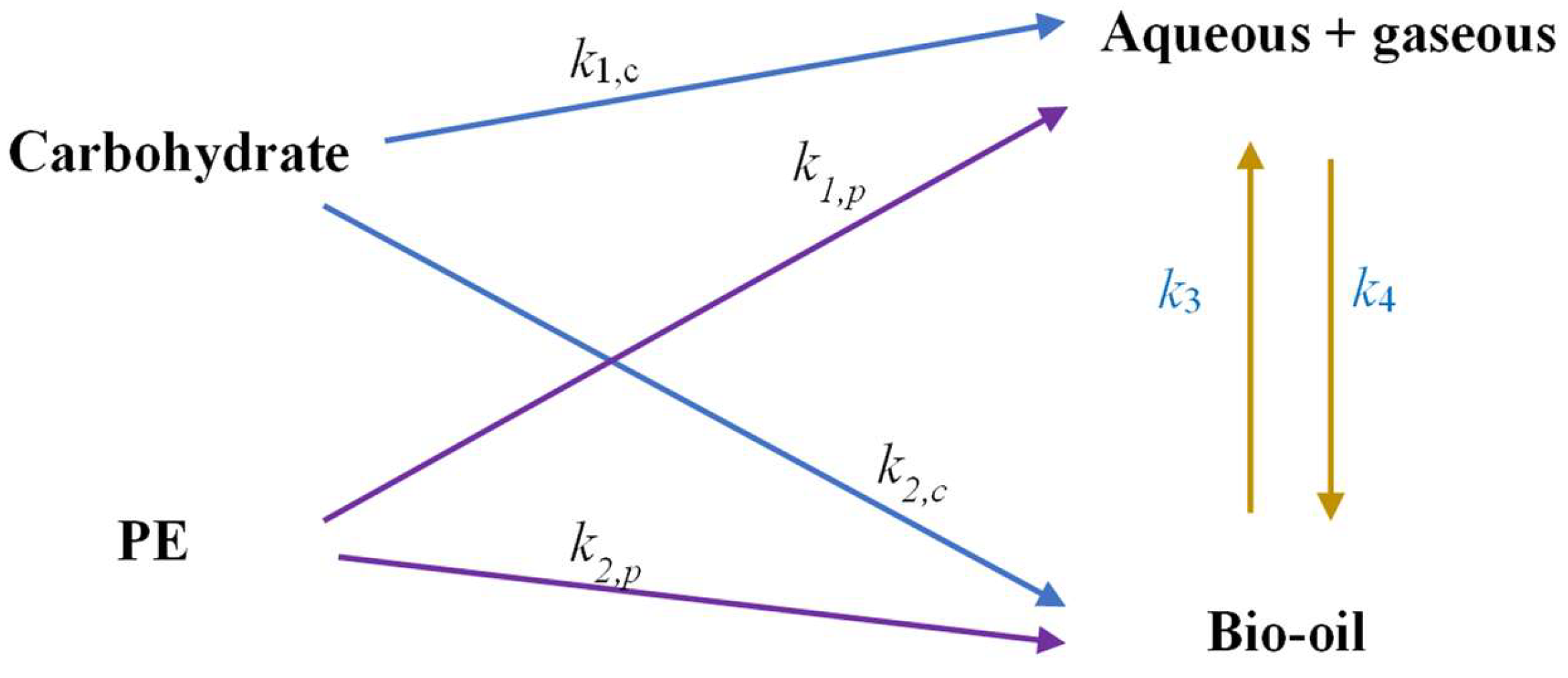

4. HTL Model and Performance Analysis for Tetra Pak

4.1. Model Development

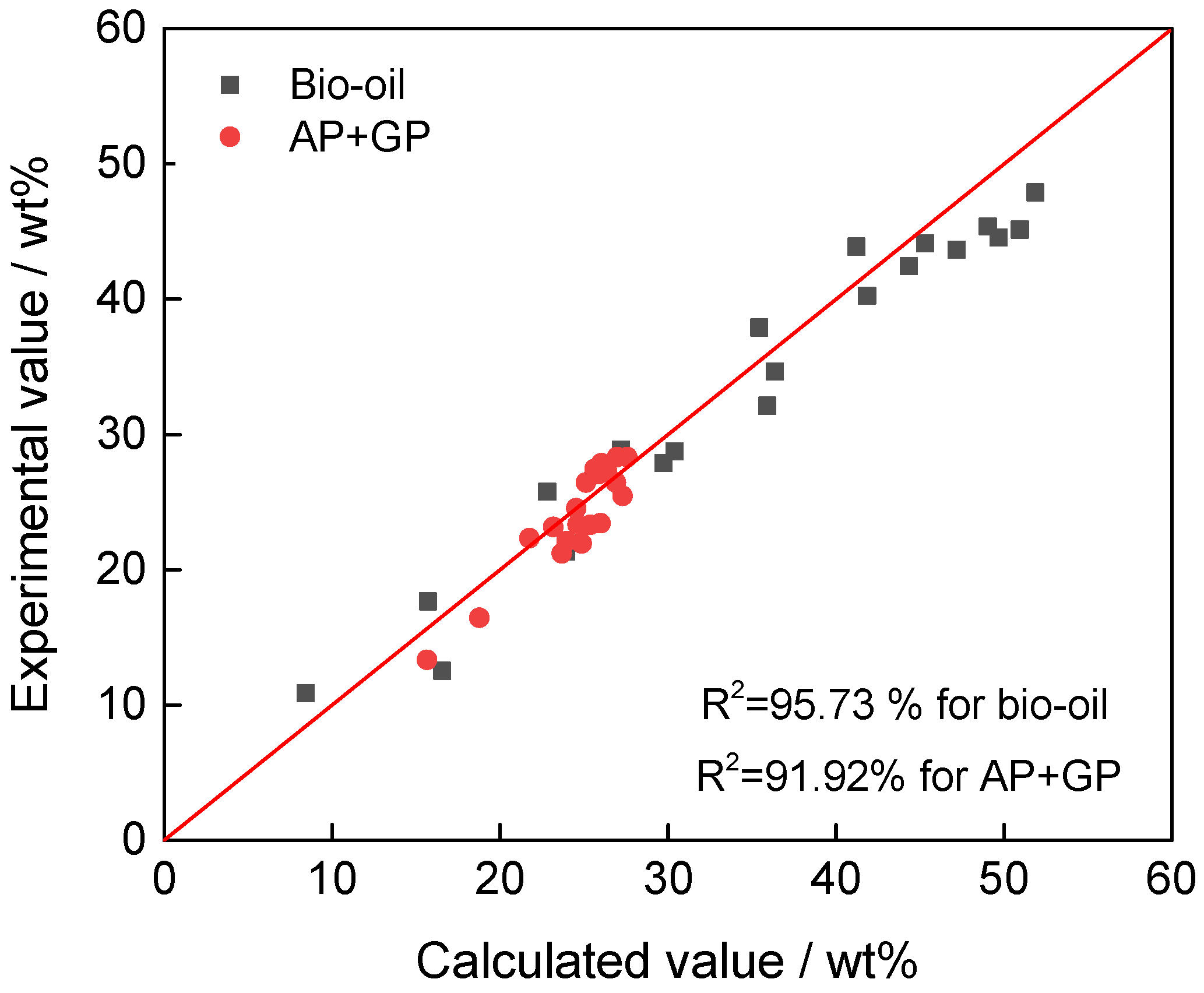

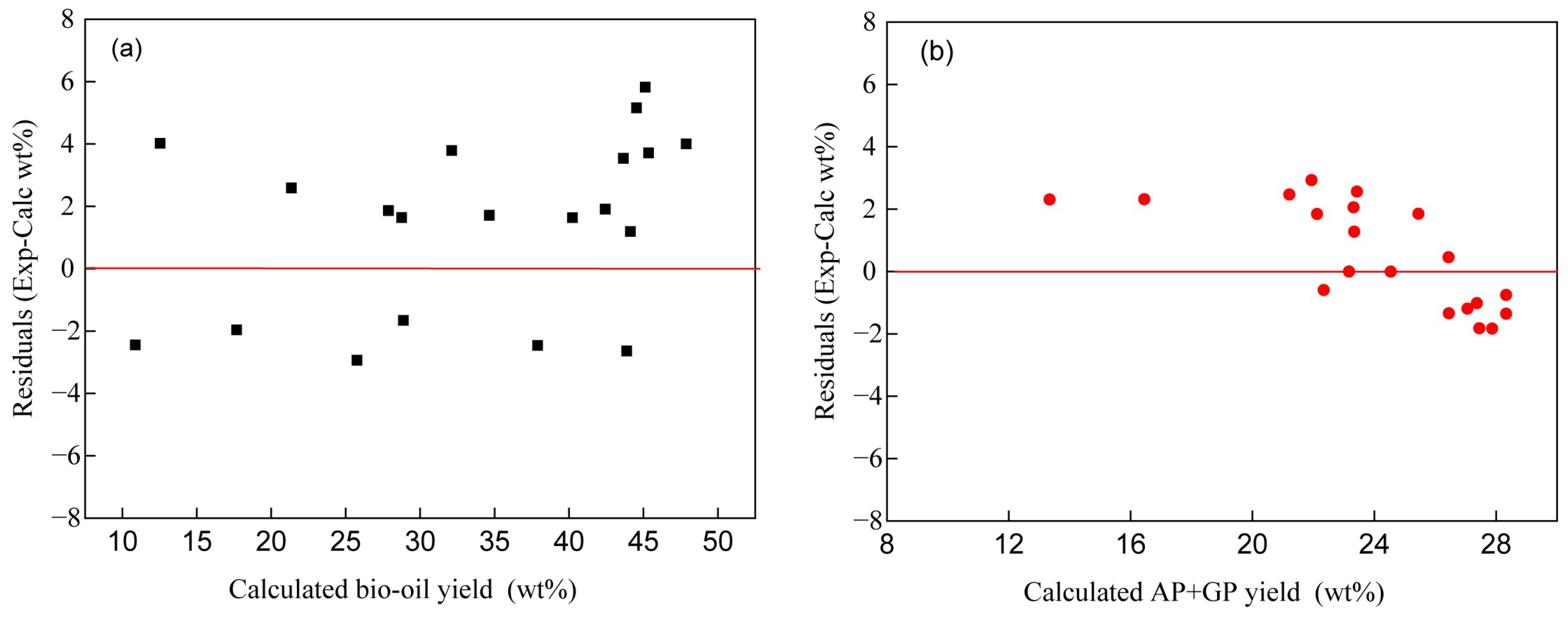

4.2. Model Correlation

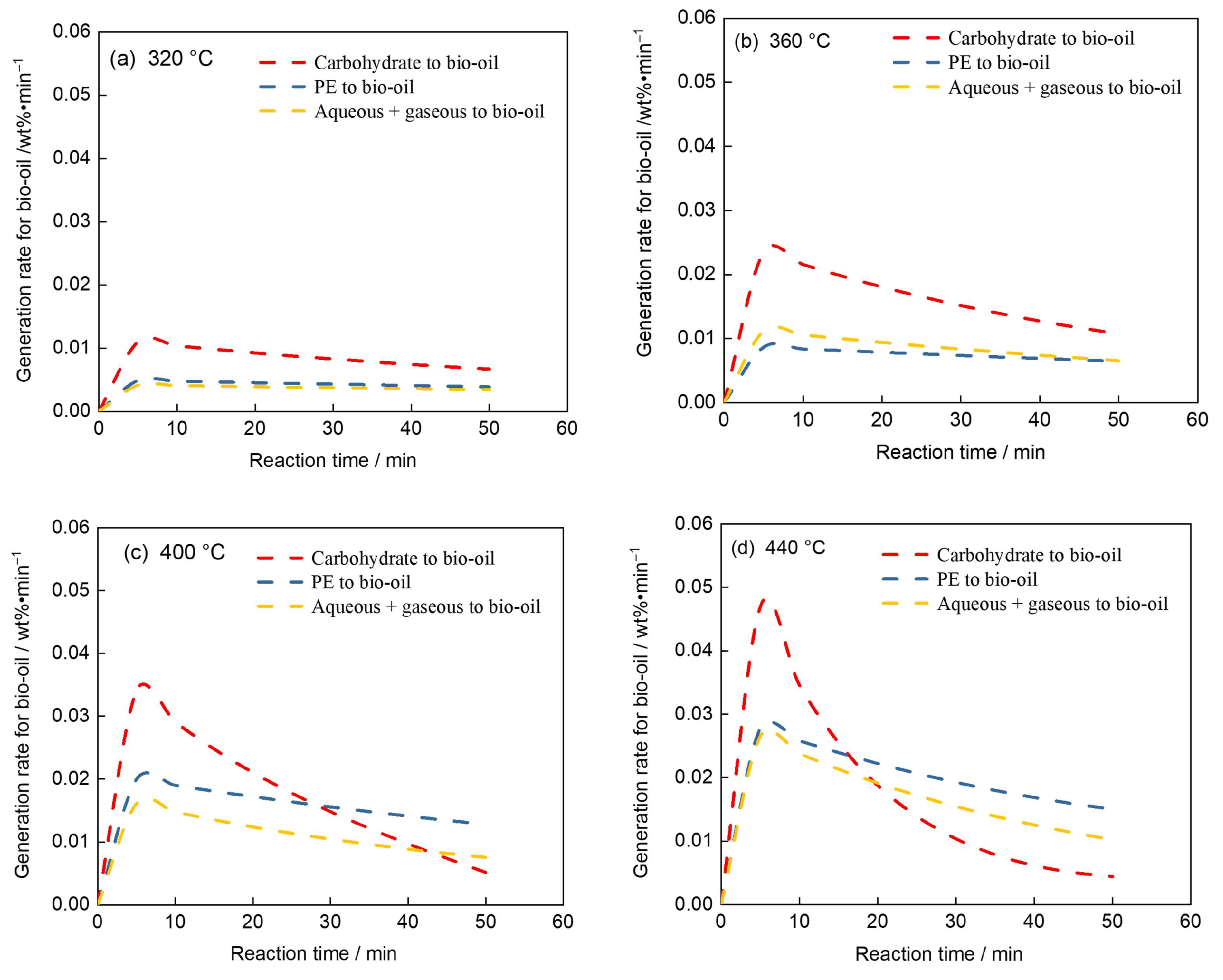

4.3. Analysis of Bio-Oil Generation Rates

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wong, P.K.; Lui, Y.W.; Tao, Q.; Lui, M.Y. Solvent-targeted recovery of all major materials in beverage carton packaging waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 202, 107367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetra Pak. Tetra Pak Sustainability Report 2023; Tetra Pak International S.A.: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.tetrapak.com (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- China Packaging Federation. Annual Report on Packaging Industry Development in China 2022; China Packaging Federation: Beijing, China, 2022; Available online: http://www.pack.org.cn (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Cao, M.; Reaihan, E.; Yuan, C.; Rosendahl, L.A.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, C.C.; Wu, Y.; Kong, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Green coal and lubricant via hydrogen-free hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Luo, Y.; Bai, X. Upcycling polyamide containing post-consumer Tetra Pak carton packaging to valuable chemicals and recyclable polymer. Waste Manag. 2021, 131, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, S.; Dai, F.; Chen, Y.; Dang, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Qi, H. Sustainable hydrothermal self-assembly of hafnium–lignosulfonate nanohybrids for highly efficient reductive upgrading of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Dai, F.; Dang, C.; Wang, M.; Liu, D.; Lu, F.; Qi, H. Scale-up biopolymer-chelated fabrication of cobalt nanoparticles encapsulated in N-enriched graphene shells for biofuel upgrade with formic acid. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4732–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahima, J.; Sundaresh, R.K.; Gopinath, K.P.; Rajan, P.S.; Arun, J.; Kim, S.H.; Pugazhendhi, A. Effect of algae (Scenedesmus obliquus) biomass pre-treatment on bio-oil production in hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL): Biochar and aqueous phase utilization studies. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, C.; Zheng, X.; Xu, D. Effect of Ce in Ni10Cex/γ-Al2O3 for the in situ hydrodeoxidation of Tetra Pak bio-oil during hydrothermal liquefaction. Energy 2022, 248, 123507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, D.C.; Biller, P.; Ross, A.B.; Schmidt, A.J.; Jones, S.B. Hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass: Developments from batch to continuous process. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 178, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jena, U.; Das, K.C.; Kastner, J.R. Effect of operating conditions on the thermochemical conversion of algae. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 7794–7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, J.; Amin, N.A.S. A review on process conditions for optimum bio-oil yield in hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 1615–1624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Wang, S.; Savage, P.E. Fast and isothermal hydrothermal liquefaction of sludge at different severities: Reaction products, pathways, and kinetics. Appl. Energy 2020, 260, 114312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Reddy, S.N. Reaction kinetics for hydrothermal liquefaction of Cu-impregnated water hyacinth to bio-oil with product characterization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2023, 198, 116677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channiwala, S.A.; Parikh, P.P. A unified correlation for estimating HHV of solid, liquid and gaseous fuels. Fuel 2002, 81, 1051–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, A.; Kumar, P.; Reddy, S.N. Hydrothermal liquefaction: Exploring biomass/plastic synergies and pathways for enhanced biofuel production. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 969, 178909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, S.; Liu, P.; Xu, F.; Wang, W.; Fan, Y. Bio-oil production from hydrothermal liquefaction of algal biomass: Effects of feedstock properties and reaction parameters. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Qian, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Gu, H.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Q. A review on fast hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass. Fuel 2022, 327, 125135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.C.; Pinho, C. Liquefaction of lignocellulosic biomass using thermogravimetric analysis to determine product distribution. Fuel 2014, 133, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-H.; Lin, B.-J.; Huang, M.-Y.; Chang, J.-S. Thermogravimetric analysis of the pyrolysis and combustion kinetics of algae-derived biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 184, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, S.; Yang, S.; Si, B.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.; Brown, R.C.; Jones, S.B.; Schmidt, A.J. From food waste to sustainable aviation fuel: Cobalt molybdenum catalysis of pretreated hydrothermal liquefaction biocrude. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 9570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-juboori, J.M.; Lewis, D.M.; Hall, T.; van Eyk, P.J. Characterisation of chemical properties of the produced organic fractions via hydrothermal liquefaction of biosolids from a wastewater treatment plant. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 170, 106703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, T.M.A.; Brdecka, M.; Salas, V.D.; Jang, B. Effects of temperature, reaction time, atmosphere, and catalyst on hydrothermal liquefaction of Chlorella. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 101, 5886–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, X.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhao, J.; Shen, L.; Rosendahl, L.; Chen, G. Influence of sodium hypochlorite/ultrasonic pretreatment on sewage sludge and subsequent hydrothermal liquefaction: Study on reaction mechanism and properties of bio-oil. Biomass Bioenergy 2023, 175, 106872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Luo, J.; Lin, J.; Ma, R.; Sun, S.; Fang, L.; Li, H. Study of co-pyrolysis endpoint and product conversion of plastic and biomass using microwave thermogravimetric technology. Energy 2022, 247, 123547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Passos, J.S.; Chiaberge, S.; Biller, P. Combined Hydrothermal Liquefaction of polyurethane and lignocellulosic biomass for improved carbon recovery. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 10630–10640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, C.; Liu, Z. Construct a novel anti-bacteria pool from hydrothermal liquefaction aqueous family. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borazjani, Z.; Azin, R.; Osfouri, S. Kinetics studies and performance analysis of algae hydrothermal liquefaction process. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2024, 14, 19257–19284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oghyanous, F.A.; Eskicioglu, C. Hydrothermal liquefaction vs. fast/flash pyrolysis for biomass-to-biofuel conversion: New insights and comparative review of liquid biofuel yield, composition, and properties. Green Chem. 2025, 27, 7009–7041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Wang, J.; Fang, C.; Du, Y.; Su, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y. Recent Progresses in Pyrolysis of Plastic Packaging Wastes and Biomass Materials for Conversion of High-Value Carbons: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saral, J.S.; Reddy, D.G.; Ranganathan, P. A general kinetic modelling for the hydrothermal liquefaction of Spirulina platensis. Biomass Convers. Biorefin. 2022, 12, 21807–21815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Han, X.; Zeng, Y.; Xu, C.C. Development of a global kinetic model based on chemical compositions of lignocellulosic biomass for predicting product yields from hydrothermal liquefaction. Renew. Energy 2023, 215, 118956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | Composition (wt%) |

|---|---|

| C | 50.55 |

| H | 6.226 |

| Oa | 38.07 |

| HHV (MJ/kg) | 19.18 |

| Fraction | Boiling Point Range | Carbon Number Range | Relative Content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 min | 20 min | 30 min | 40 min | |||

| Naphtha | 25–200 °C | C7–C10 | 27.6 | 20.1 | 26.5 | 21.9 |

| Kerosene | 200–300 °C | C11–C15 | 32.9 | 24.5 | 25.5 | 26.2 |

| Diesel | 300–550 °C | C16–C47 | 28.3 | 29.0 | 27.7 | 30.0 |

| Vacuum Oil Residue | ≥550 °C | ≥C48 | 11.3 | 26.3 | 20.4 | 22.0 |

| Subscript | Reaction | k (min−1) | E (KJ/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 320 °C | 360 °C | 400 °C | 440 °C | |||

| 1,C | Carb → AP + GP | 0.0328 | 0.045 | 0.06 | 0.0794 | 25.78 |

| 1,P | PE → AP + GP | 0 | 0.00168 | 0.00543 | 0.00918 | 78.27 |

| 2,C | Carb → bio-oil | 0.0116 | 0.0257 | 0.04 | 0.0637 | 49.01 |

| 2,P | PE → bio-oil | 0.005 | 0.00891 | 0.0209 | 0.03005 | 54.91 |

| 3 | AP + GP → bio-oil | 0.0203 | 0.0312 | 0.0435 | 0.0569 | 30.12 |

| 4 | bio-oil → AP + GP | 0.00421 | 0.0118 | 0.0176 | 0.0296 | 55.47 |

| Feed | Reaction Rate Constant k/min−1 | E (KJ/mol) | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 320 | 360 | 400 | |||

| Carb → AP + GP | |||||

| Tetra Pak | 0.0328 | 0.045 | 0.06 | 25.78 | This paper |

| Spirulina | 0.1234 | 0.1207 | 0.1382 | 9.87 | [31] |

| Cellulose | 0.27 | -- | -- | 68.92 | [32] |

| Xylan | 0.37 | -- | -- | 2.88 | [32] |

| Alkali lignin | 0.4 | -- | -- | 2.88 | [32] |

| Aurantiochytrium sp. | 0.0331 | 0.0506 | 0.0724 | 33.08972 | [28] |

| C. protothecoides | 0.3234 | 0.4649 | 0.6333 | 27.89347 | [28] |

| Scenedesmus sp. | 0.3613 | 0.5259 | 0.7239 | 28.84958 | [28] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | 0.9788 | 1.1048 | -- | 9.4521866 | [28] |

| Carb→bio-oil | |||||

| Tetra Pak | 0.0116 | 0.0257 | 0.04 | 49.01 | This paper |

| Spirulina | 0.0224 | 0.008 | 0.0788 | 11.15 | [31] |

| Cellulose | 0.16 | -- | -- | 74.29 | [32] |

| Xylan | 0.14 | -- | -- | 25.74 | [32] |

| Alkali lignin | 0.24 | -- | -- | 64.83 | [32] |

| Aurantiochytrium sp. | 0.0624 | 0.1378 | 0.2705 | 60.88 | [28] |

| C. protothecoides | 0.0013 | 0.0049 | 0.0155 | 102.86 | [28] |

| Scenedesmus sp. | 0.0004 | 0.0021 | 0.0076 | 122.34 | [28] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | 0.0004 | 0.0008 | 54.10 | [28] | |

| AP + GP→bio-oil | |||||

| Tetra Pak | 0.0203 | 0.0312 | 0.0435 | 30.12 | This paper |

| Spirulina | 0.2965 | 0.3022 | 0.2447 | 10.12 | [31] |

| Celluslose | 0.13 | -- | -- | 38.32 | [32] |

| Xylan | 0.007 | -- | -- | 20.52 | [32] |

| Alkali lignin | 0.13 | -- | -- | 28.06 | [32] |

| Aurantiochytrium sp. | 0.0895 | 0.1498 | 0.2324 | 39.74 | [28] |

| C. protothecoides | 0.0057 | 0.013 | 0.0262 | 63.52 | [28] |

| Scenedesmus sp. | 0.004 | 0.0078 | 0.0137 | 51.27 | [28] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | 0.407 | 0.4867 | -- | 14.00 | [28] |

| Bio-oil→AP + GP | |||||

| Tetra Pak | 0.00421 | 0.0118 | 0.0176 | 55.47 | This paper |

| Spirulina | 0.2841 | 0.3482 | 0.2977 | 10.39 | [31] |

| Celluslose | 0.12 | -- | -- | 43.93 | [32] |

| Xylan | 0.038 | -- | -- | 23.93 | [32] |

| Alkali lignin | 0.13 | -- | -- | 28.16 | [32] |

| Aurantiochytrium sp. | 0.0848 | 0.1346 | 0.1995 | 35.51 | [28] |

| C. protothecoides | 0.0039 | 0.0129 | 0.0352 | 91.34 | [28] |

| Scenedesmus sp. | 0.0035 | 0.0114 | 0.031 | 90.54 | [28] |

| Chlorella vulgaris | 0.3233 | 0.4072 | -- | 18.01 | [28] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Lu, A.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Y.; Shan, D.; Fang, C. Kinetic Analysis and Products Characterization of Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Tetra Pak Waste for Bio-Oil Production. Polymers 2025, 17, 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243246

Wang Y, Lu A, Liu Z, Feng Y, Shan D, Fang C. Kinetic Analysis and Products Characterization of Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Tetra Pak Waste for Bio-Oil Production. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243246

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yuzhen, Ao Lu, Zhuan Liu, Yu Feng, Di Shan, and Changqing Fang. 2025. "Kinetic Analysis and Products Characterization of Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Tetra Pak Waste for Bio-Oil Production" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243246

APA StyleWang, Y., Lu, A., Liu, Z., Feng, Y., Shan, D., & Fang, C. (2025). Kinetic Analysis and Products Characterization of Hydrothermal Liquefaction of Tetra Pak Waste for Bio-Oil Production. Polymers, 17(24), 3246. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243246