Mechanical Behavior of Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites (Towpreg) Under Various Temperature Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Constituent Materials

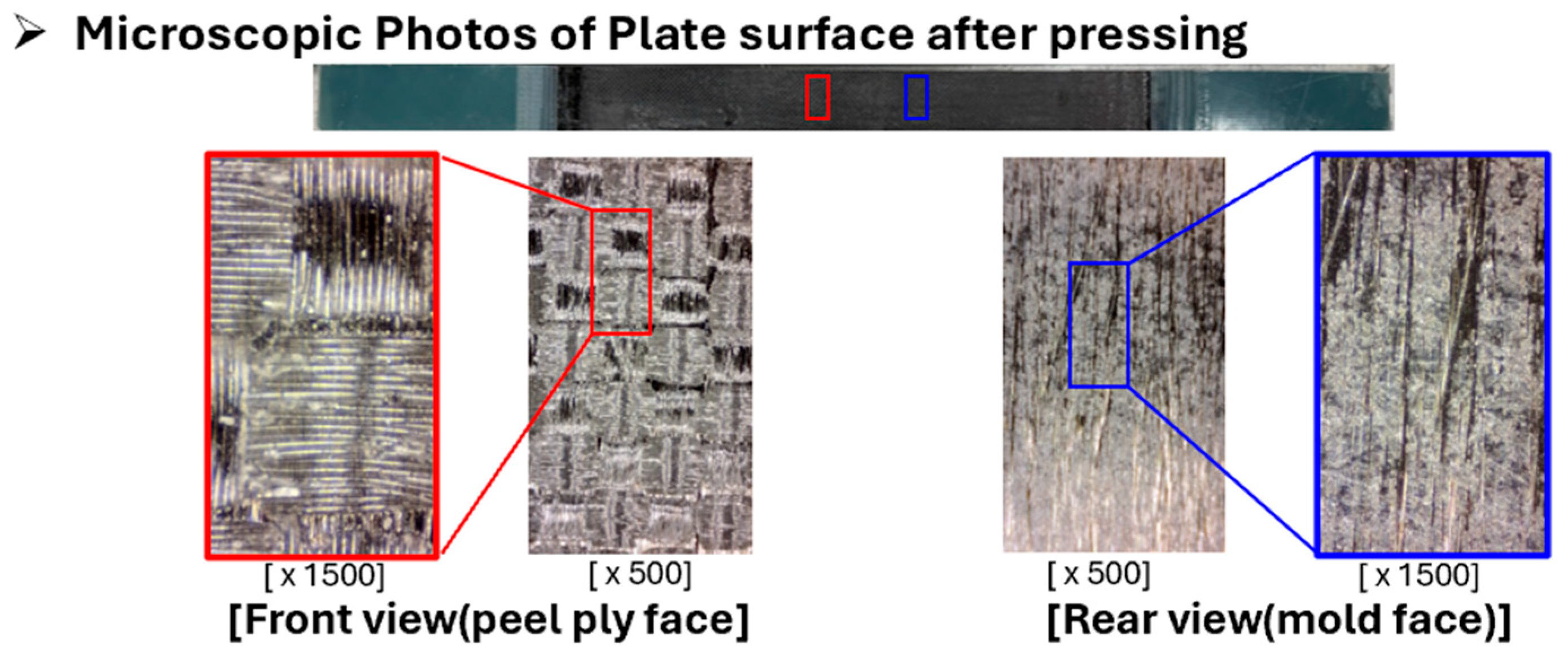

2.2. Manufacturing Process of Towpreg Flat Panel and Specimens

2.3. Novel Localized Thermal Control Systems

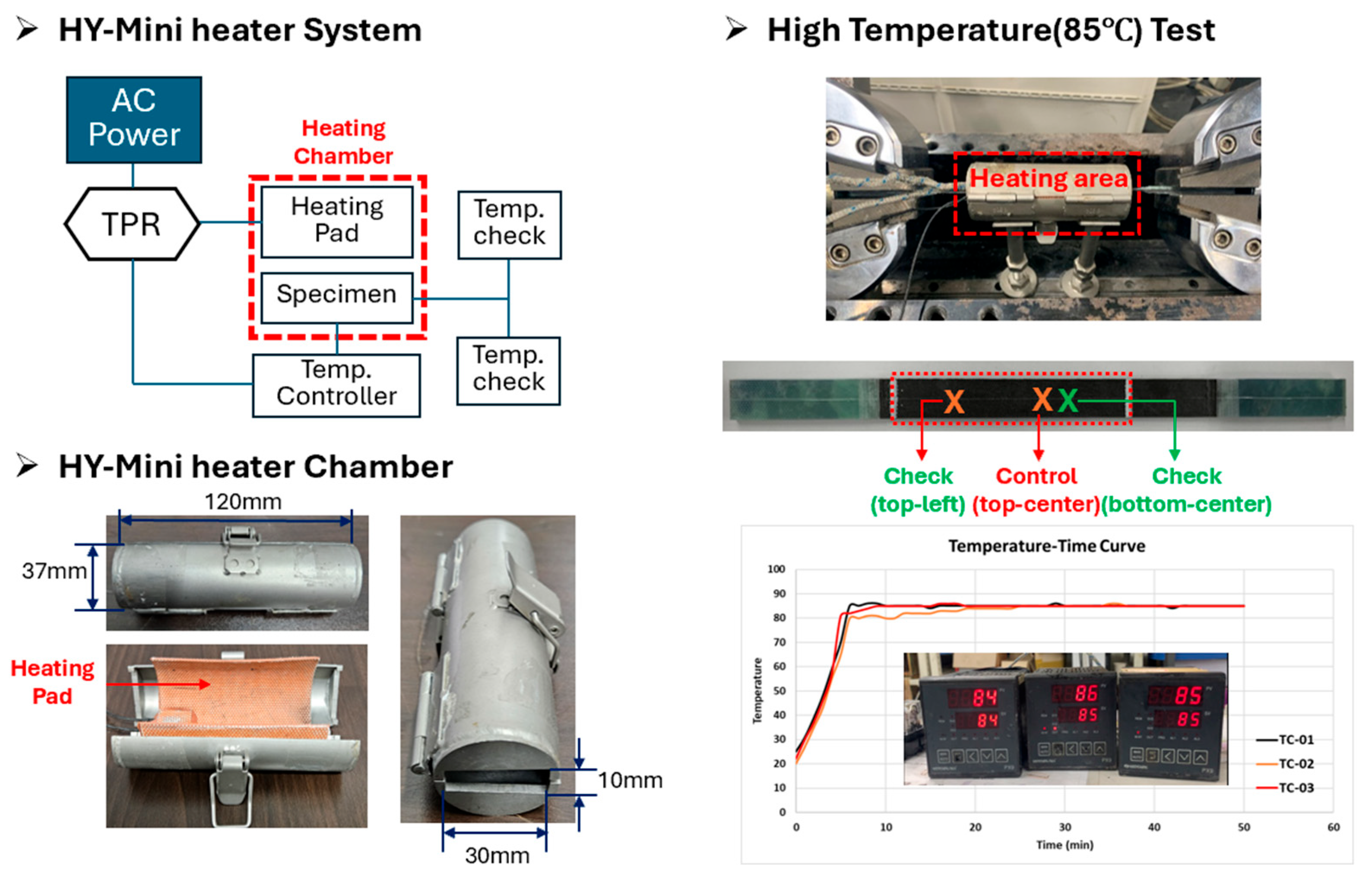

2.3.1. High-Temperature (85 °C) “HY-Mini Heater System”

2.3.2. Low-Temperature (−40 °C) “HY-Cooler System”

2.4. Mechanical Test Procedure

3. Results

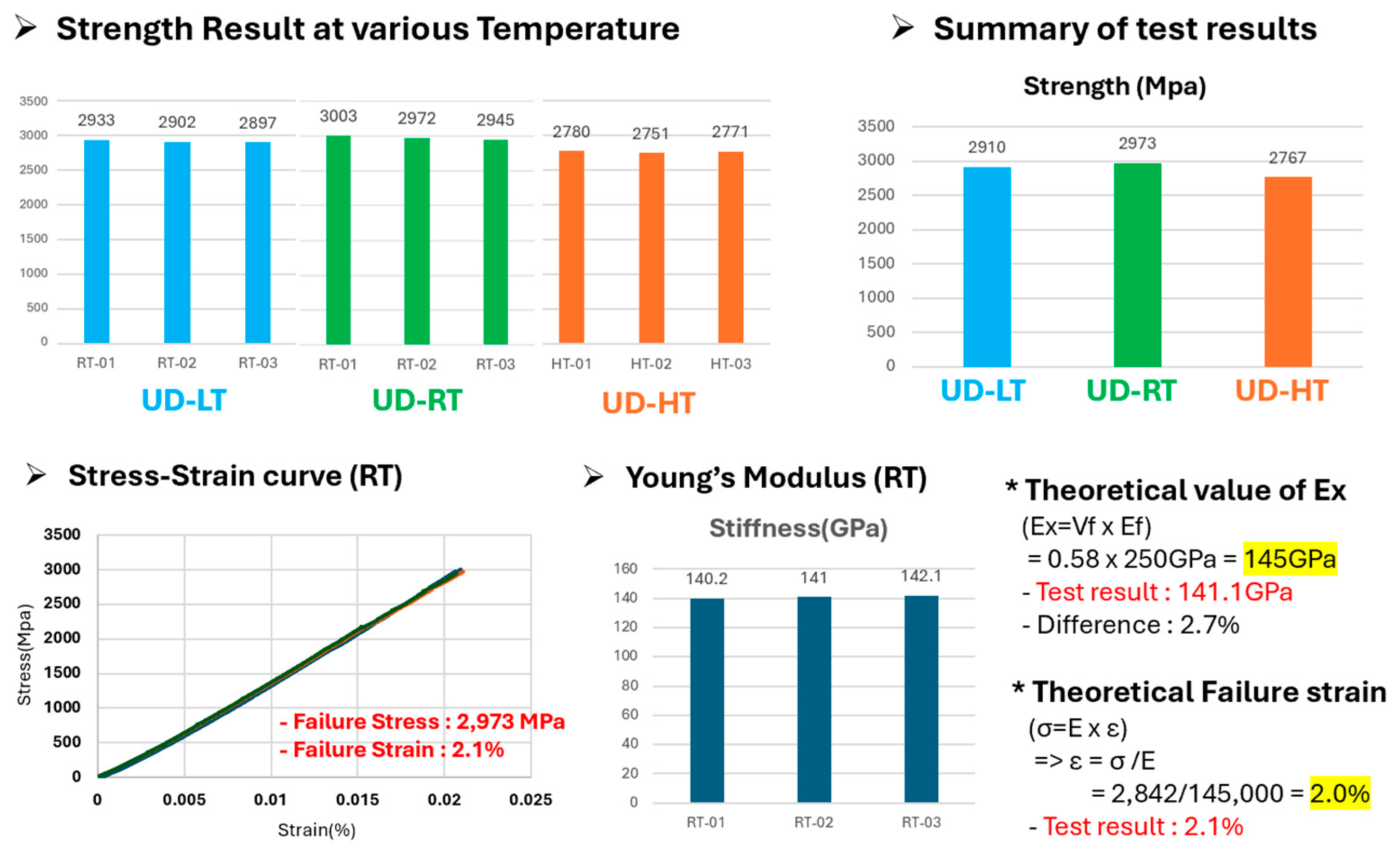

3.1. Static Tensile Behavior Analysis

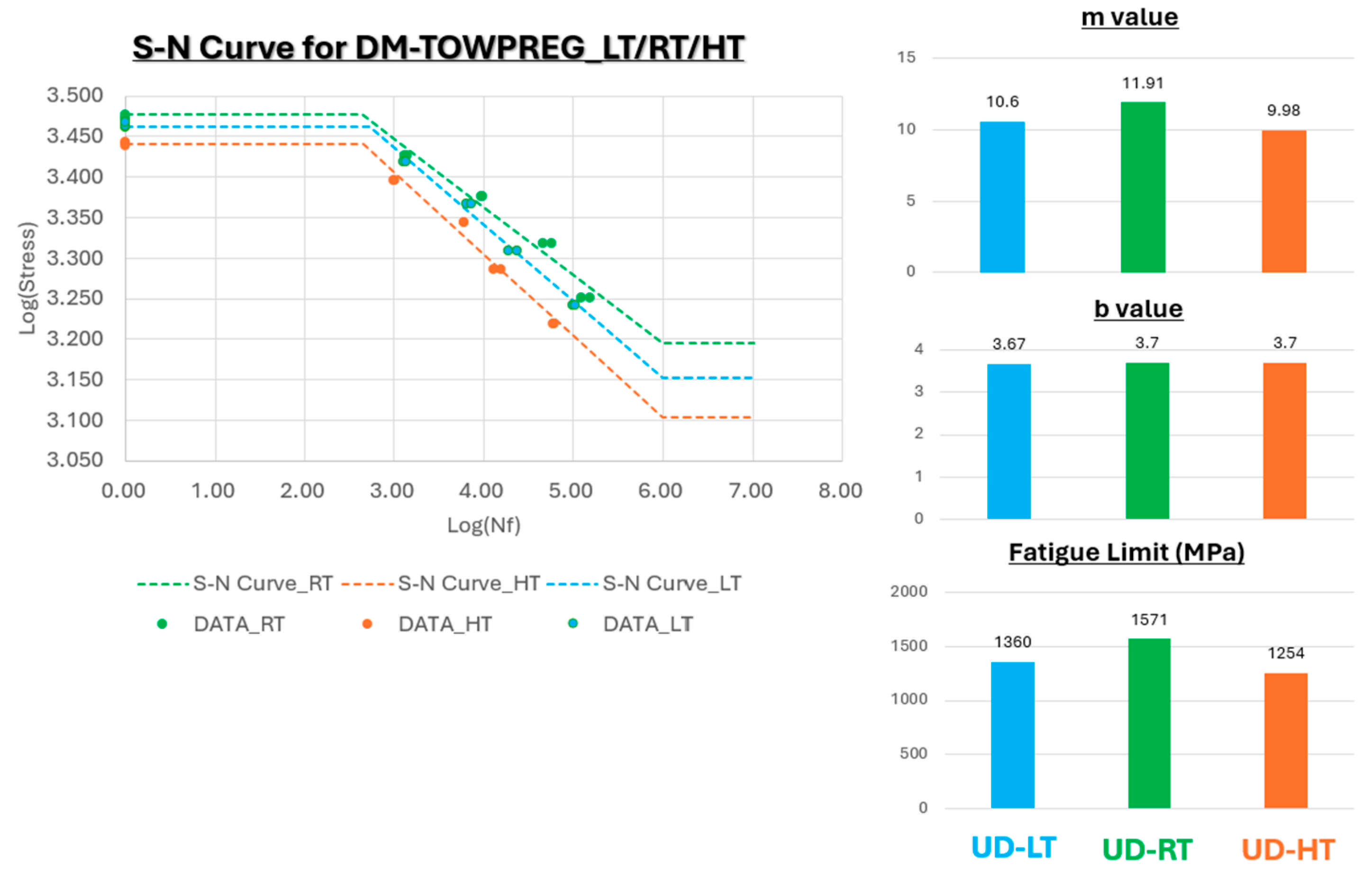

3.2. Fatigue Life (S–N) Behavior Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. A New Paradigm in Composite Testing: Validation of the Localized Thermal Control Methodology

4.2. Superior Thermo-Mechanical Stability of the Carbon Fiber Reinforcement Polymer Composite (Towpreg)

- (1)

- High-Temperature Stability: The limited 7% decrease in tensile strength at 85 °C is primarily attributed to the high Tg of the DM resin (127 °C). Since the service temperature (85 °C) remains well below Tg, the matrix maintains a robust glassy state rather than entering the transition region [36]. This prevents the typical degradation phenomena observed when T approaches Tg, such as matrix softening, or plasticization. Regarding the fiber–matrix interfacial Strength and relaxation behavior, which are critical concerns at elevated temperatures, the stability of the fatigue limit and the constant Basquin intercept (log b) observed in this study suggest that the interfacial bonding integrity was maintained without significant relaxation-induced degradation. Furthermore, while residual thermal stresses typically induce microcracking at cryogenic temperatures, the high Tg margin at 85 °C minimizes the impact of thermal stress on the static strength.

- (2)

- Low-Temperature Stability: The suppression of strength variation to within 2% at −40 °C is equally significant, indicating the absence of low-temperature embrittlement. Many composite systems experience residual thermal stress from the mismatch in the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) between fibers and the matrix during cooling, often resulting in matrix microcracking and strength loss. The stable performance of the carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer composites (Towpreg) even under low-temperature conditions suggests that the matrix possesses high toughness and that fiber–matrix adhesion is strong, enabling the material to effectively resist internal stress concentrations.

4.3. Temperature-Dependent Fatigue Damage Mechanisms

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Methodological Contribution: The study identified the fundamental limitations of conventional large-chamber temperature testing (tab slippage at high temperature and energy inefficiency at low temperature) and introduced a new specimen-based localized thermal control methodology to overcome these issues.

- (2)

- High-Temperature System: The HY-Mini Heater System developed for 85 °C testing effectively prevented tab slippage and enabled reliable measurement of intrinsic material properties. Three-point thermocouple validation confirmed uniform temperature stabilization (±1.5 °C) within 20 min.

- (3)

- Low-Temperature System: The HY-Cooler System designed for −40 °C testing combined a Stirling cooler (utilizing the Joule–Thomson effect), a thermosiphon, and dual insulation (aerogel + foil) to achieve stable local cooling within 60 min using a compact and cost-efficient setup.

- (4)

- Material Process: A reproducible Towpreg plate fabrication process was developed by optimizing dry-winding and hot-press parameters according to the DM resin TDS, ensuring consistent specimen quality.

- (5)

- Performance Verification (Static): Static mechanical tests confirmed the excellent thermo-mechanical stability of the carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer composites (Towpreg), with tensile strength limited to approximately −7% at 85 °C and −2% at −40 °C relative to room temperature.

- (6)

- Performance Verification (Fatigue): Fatigue analysis revealed a nearly constant Basquin intercept (log b = 3.67–3.70) and a stable slope (m = 9.98–11.91) across all temperature conditions, demonstrating quantitatively that temperature variation has only a minor effect on the material’s strength and fatigue life.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kovac, A.; Paranos, M.; Marcius, D. Hydrogen in energy transition: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 10016–10035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züttel, A. The prospects for hydrogen as an energy carrier. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2016, 41, 19911–19925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpasi, S.O.; Anekwe, I.M.S.; Tetteh, E.K.; Amune, U.O.; Kiambi, S.L. Hydrogen as a clean energy carrier: Advancements, challenges, and its role in a sustainable energy future. Clean Energy 2025, 9, 52–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabianbardar, A.; Sefidvash, H.; Eslami, H. Challenges, processes, and innovations in high-pressure hydrogen storage vessels: A comprehensive review. Mater. Test. Process. 2025, 39, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeq, A.M.; Homod, R.Z.; Hussein, A.K.; Togun, H.; Mahmoodi, A.; Isleem, H.F.; Patil, A.R.; Moghaddam, A.H. Hydrogen energy systems: Technologies, trends, and future prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 934, 173622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko, A.J.; Epaarachchi, J.; Jewewantha, J.; Zeng, X. A review of Type IV composite overwrapped pressure vessels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 109, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chai, X.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yang, X.; Wen, Y.; Xu, Z.; Jiang, B.; Wang, J.; Jin, G.; et al. Small-Scale High-Pressure Hydrogen Storage Vessels: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouhala, L.; Karatrantos, A.; Reinhardt, H.; Schramm, N.; Akin, B.; Rauscher, A.; Mauersberger, A.; Taşkıran, S.T.; Ulaşlı, M.E.; Aktaş, E.; et al. Advancement in the Modeling and Design of Composite Pressure Vessels for Hydrogen Storage: A Comprehensive Review. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.S.; Kim, H.S.; Yoon, K.T.; Lee, K.J. Failure analysis of a 700-bar type IV hydrogen composite pressure vessel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 13206–13214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byerly, D.; Wilson, C. Carbon Composite Optimization Reducing Tank Cost. In DOE Hydrogen Program; Project ID ST237; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. Available online: https://www.hydrogen.energy.gov/docs/hydrogenprogramlibraries/pdfs/review24/st237_byerly_2024_o.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Shin, H.K.; Ha, S.K. A review on the cost analysis of hydrogen gas storage tanks for fuel cell vehicles. Energies 2023, 16, 5233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global Hydrogen Review 2024; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-hydrogen-review-2024 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Mazzuca, P.; Firmo, J.P.; Correia, J.R.; Rosa, I.C. Fire Behaviour of Vacuum-Infused Glass Fibre Reinforced Polymer Sandwich Panels: The Role of Polyurethane and Polyethylene Terephthalate Foam Cores and Panel Architecture. Eng. Struct. 2025, 345, 121411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, N.; Pouladvand, A.R.; Beheshty, M.H. Optimizing Towpreg Parameters for Filament Winding: A Comparison With Wet Winding. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 15331–15341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.-X.; Wang, L.; Li, R.; Wei, Z.-X.; Zhou, W.-W. Fatigue test of carbon epoxy composite high pressure hydrogen storage vessel under hydrogen environment. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. A 2013, 14, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trajkovska Petkoska, A.; Samakoski, B.; Samardjioska Azmanoska, B.; Velkovska, V. Towpreg—An Advanced Composite Material with a Potential for Pressurized Hydrogen Storage Vessels. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, B.E.; Hylton, A.R. Cost comparisons of wet filament winding versus prepreg filament winding for type II and type IV CNG cylinders. Sampe J. 2001, 37, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ökten, Y.K. Use of Carbon/Epoxy Towpregs during Dry Filament Winding of Composite Flat Specimens and Pressure Vessels. Master’s Thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey.

- Xiong, X.; Wang, W.; Li, X.; Fan, F.; Zhou, J.; Chen, M. Prediction and Optimization of the Long-Term Fatigue Life of a Composite Hydrogen Storage Vessel Under Random Vibration. Materials 2025, 18, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomioka, J.; Kiguchi, K.; Tamura, Y.; Mitsuishi, H. Influence of pressure and temperature on the fatigue strength of Type-3 compressed-hydrogen tanks. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 17639–17644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, P.; Zhang, D. Effect of Temperature-Dependent Mechanical Properties on Drilling-Induced Delamination of CFRP. Polymers 2023, 15, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khashaba, U.A.; Al-Sultan, A.S.; El-Soud, A.A. Influence of temperature on a carbon-fibre epoxy composite subjected to static and fatigue loading under mode-I delamination. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 47, 240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Wei, S.; Hong, Y.; Zheng, C. Prediction of long-term fatigue life of CFRP composite hydrogen storage vessel based on micromechanics of failure. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 97, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabaz, S.M.; Sharma, S.; Shetty, N.; Shetty, S.D.; Gowrishankar, M.C. Influence of Temperature on Mechanical Properties and Machining of Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites: A Review. Eng. Sci. 2021, 16, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrion, M.; Lizarbe, S.; Barroso, A.; Viña, J. Low temperature fatigue crack propagation in toughened epoxy resins aimed for filament winding of type V composite pressure vessels. Polymers 2021, 13, 3302. [Google Scholar]

- Instron. 3119-600 Series Environmental Chambers. In Instron Technical Documentation; Instron Corporation: Norwood, MA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.instron.com (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- TA Instruments. Environmental Test Chamber (ETC). In TA Instruments Product Sheet; TA Instruments: New Castle, DE, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Banea, M.D.; da Silva, L.F.M.; Campilho, R.D.S.G. Effect of Temperature on Tensile Strength and Mode I Fracture Toughness of a High-Temperature Epoxy Adhesive. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2012, 26, 939–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyosung Advanced Materials. Carbon Materials (TANSOME®)—High-Pressure Vessel Applications; HS Hyosung Advanced Materials Co., Ltd.: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D3039/D3039M-17; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3479/D3479M-19; Standard Test Method for Tension–Tension Fatigue of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Bogdanov, A.A.; Panin, S.V.; Kosmachev, P.V. Characterization of Fatigue Properties of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 17, 157. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, R.B.; Reed, L.; Loy, Z. Discerning Localized Thermal Heating from Mechanical Strain in Polymer Matrix Composites. Sensors 2020, 20, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazlali, B.; Aid, A.; Strand, M.; Berggreen, C.; Branner, K. Reducing Stress Concentrations in Static and Fatigue Tensile Tests of Unidirectional Composites: A Review. Compos. Part A 2024, 180, 107603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, D.J. Center for Composite Materials and Structures: Compression Testing of Composite Materials; NASA CR-179637; National Aeronautics and Space Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Bard, S.; Demleitner, M.; Weber, R.; Zeiler, R.; Altstädt, V. Effect of Curing Agent on the Compressive Behavior at Elevated Test Temperature of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Polymers 2019, 11, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Property | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Reinforcement (Hyosung H2550-24K Carbon Fiber) | Filament Diameter (µm) | 7.0 |

| Tensile Strength (MPa) | 4900 | |

| Tensile Modulus (GPa) | 250 | |

| Tensile Strain (%) | 2.0 | |

| Fiber Density (g/cm3) | 1.78 |

| Category | Property | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix (CeTePox DM Epoxy System) | Glass Transition Temp, Tg (DSC) (°C) | 127 |

| Initial Mixing Viscosity (@ 50 °C) (mPas) | 590–600 | |

| Gel Time (@ 110 °C) (min) | 20–25 | |

| Recommended Cure Condition | 110 °C (1 h) + 120 °C (2 h) |

| Process | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Dry Winding | Winding Tension (kg) | 4 |

| Winding Speed (mm/s) | Max. 120 | |

| Hot Press Curing | Pressure (MPa) | 0.65 |

| Stage 1 (Temp./Time) | 110 °C/1 h | |

| Stage 2 (Temp./Time) | 120 °C/2 h | |

| Mold Configure | Shim Thickness (mm) | 1.2 |

| Dam Thickness (mm) | 2.0 |

| Temperature Condition | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Strength (vs. RT) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Failure Strain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −40 °C | 2907.7 | 97.8% | - | - |

| 25 °C | 2973.3 | 100% | 141.1 | 2.1 |

| 85 °C | 2767.3 | 93.0% | - | - |

| Temperature Condition | Basquin Slope (m) | Basquin Intercept (log b) | Fatigue Limit (MPa) | Fatigue Limit (vs. RT%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| −40 °C | 10.60 | 3.67 | 1360 | 86.6% |

| 25 °C | 11.97 | 3.70 | 1571 | 100% |

| 85 °C | 9.98 | 3.70 | 1254 | 79.8% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, Y.; Sun, J.; Dixit, A.; Kim, D.H.; Xia, Y.; Ha, S.K. Mechanical Behavior of Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites (Towpreg) Under Various Temperature Conditions. Polymers 2025, 17, 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243241

Seo Y, Sun J, Dixit A, Kim DH, Xia Y, Ha SK. Mechanical Behavior of Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites (Towpreg) Under Various Temperature Conditions. Polymers. 2025; 17(24):3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243241

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Yoonduck, Jiming Sun, Amit Dixit, Da Hye Kim, Yuen Xia, and Sung Kyu Ha. 2025. "Mechanical Behavior of Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites (Towpreg) Under Various Temperature Conditions" Polymers 17, no. 24: 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243241

APA StyleSeo, Y., Sun, J., Dixit, A., Kim, D. H., Xia, Y., & Ha, S. K. (2025). Mechanical Behavior of Carbon-Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites (Towpreg) Under Various Temperature Conditions. Polymers, 17(24), 3241. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17243241