Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Safety of New Wound Coatings Based on Cod Collagen for Fast Healing of Burn Surfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Isolation of Fish Collagen

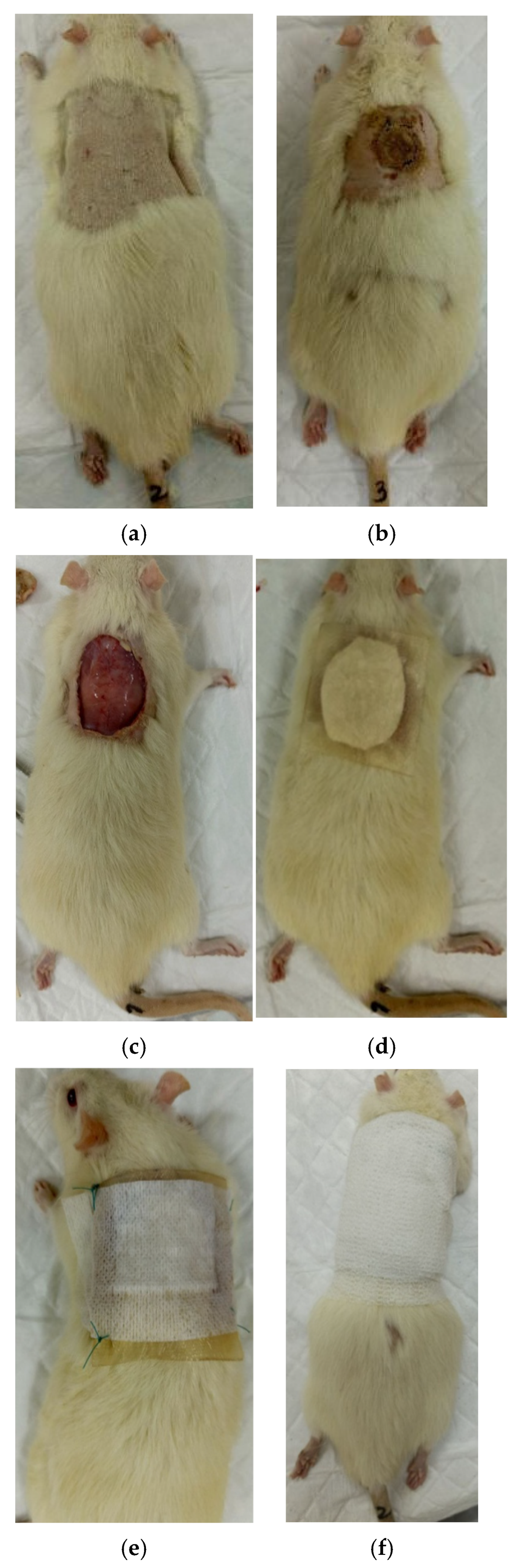

2.3. Obtaining Gel for the Sample—“Coating No. 1”

2.4. Obtaining Gel for the Sample—“Coating No. 2”

2.5. Production of Sponge Plates

2.6. Setting up an Experiment with Animals

2.7. Research Methods

2.7.1. Sponge-Plate Analysis

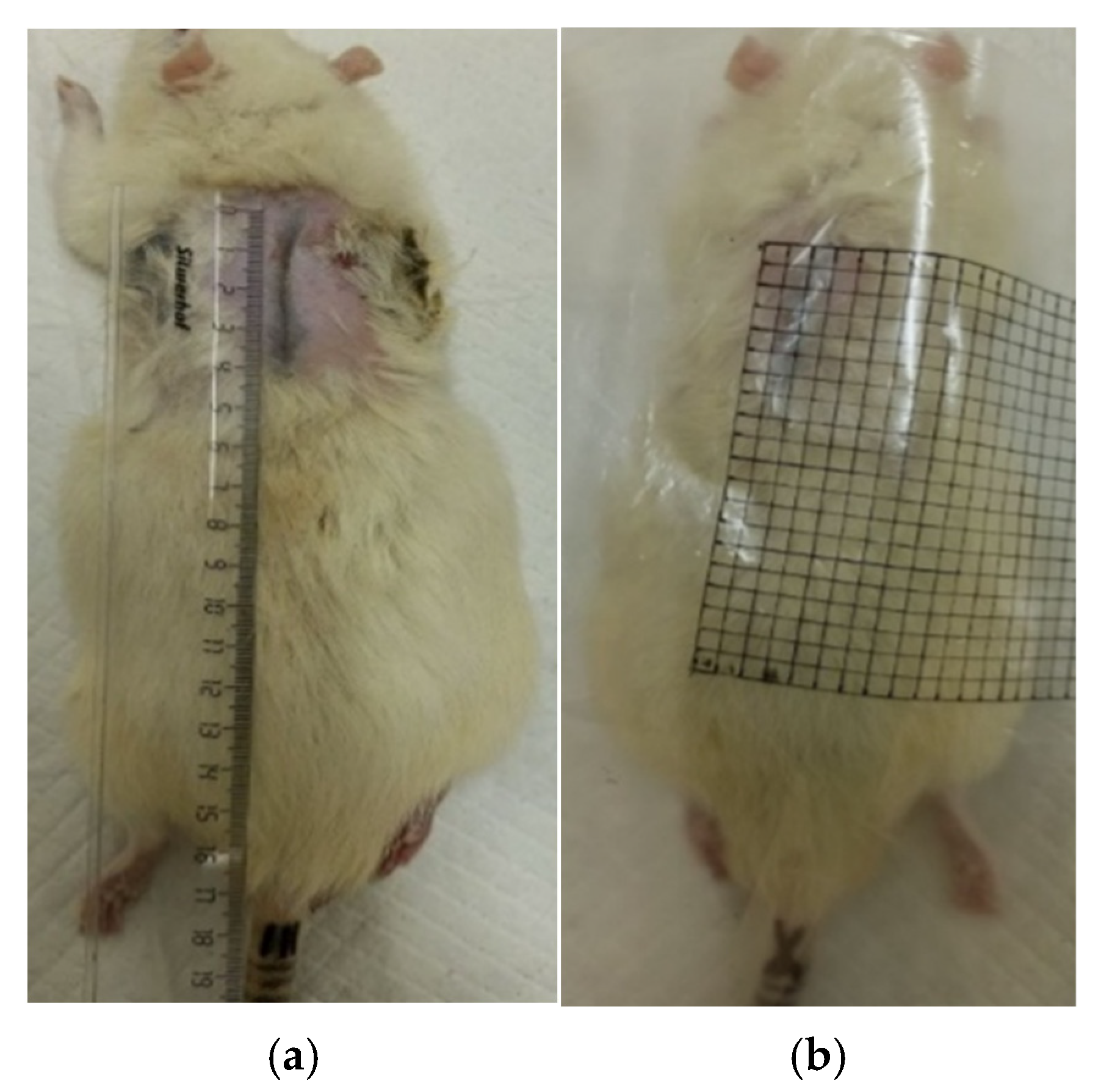

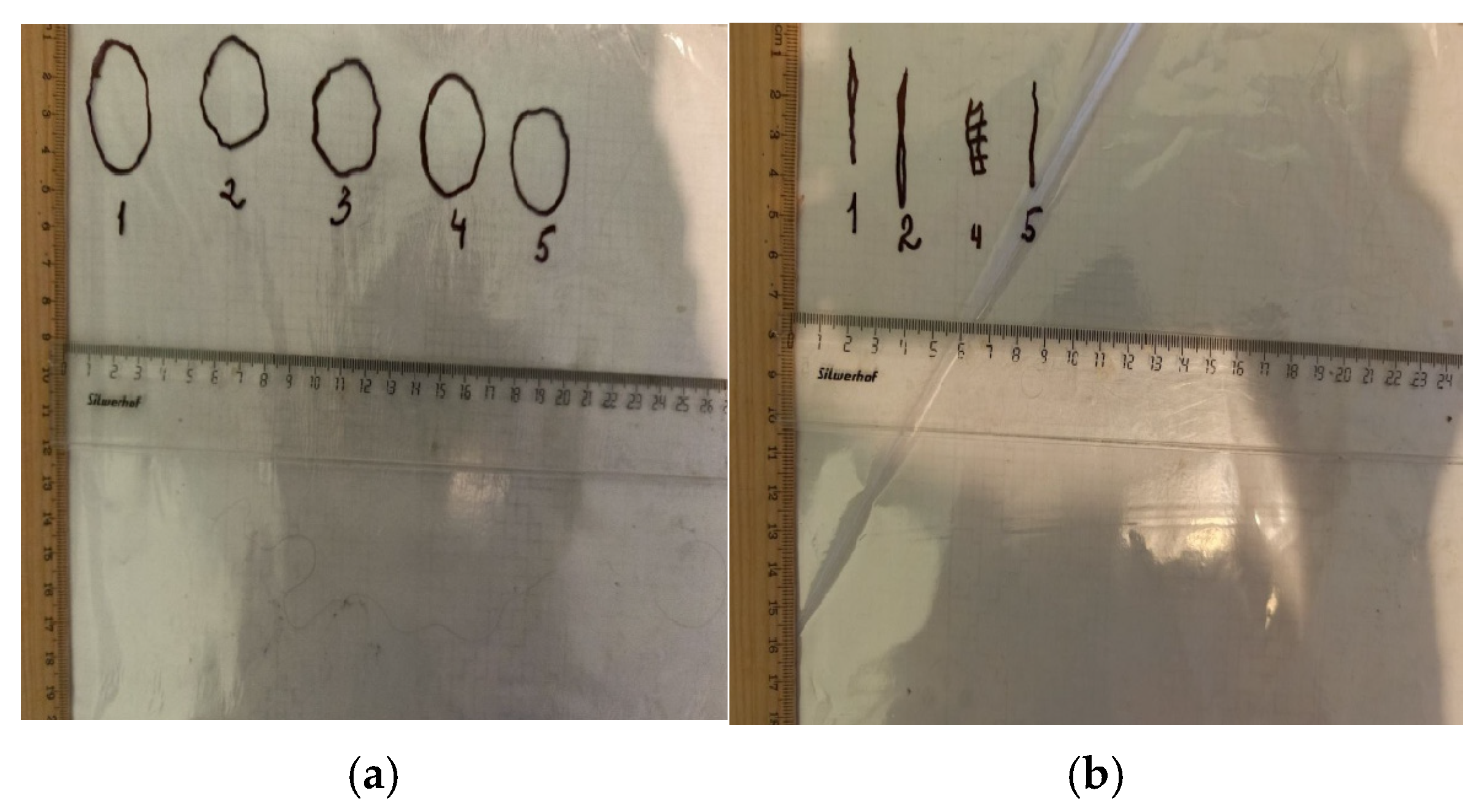

2.7.2. Planimetric Assessment of the Process of Repair of Burn Wounds in Rats

2.7.3. Morphological Studies of the Skin

2.7.4. Microcirculation Research

2.8. Statistical Processing of Results

3. Results

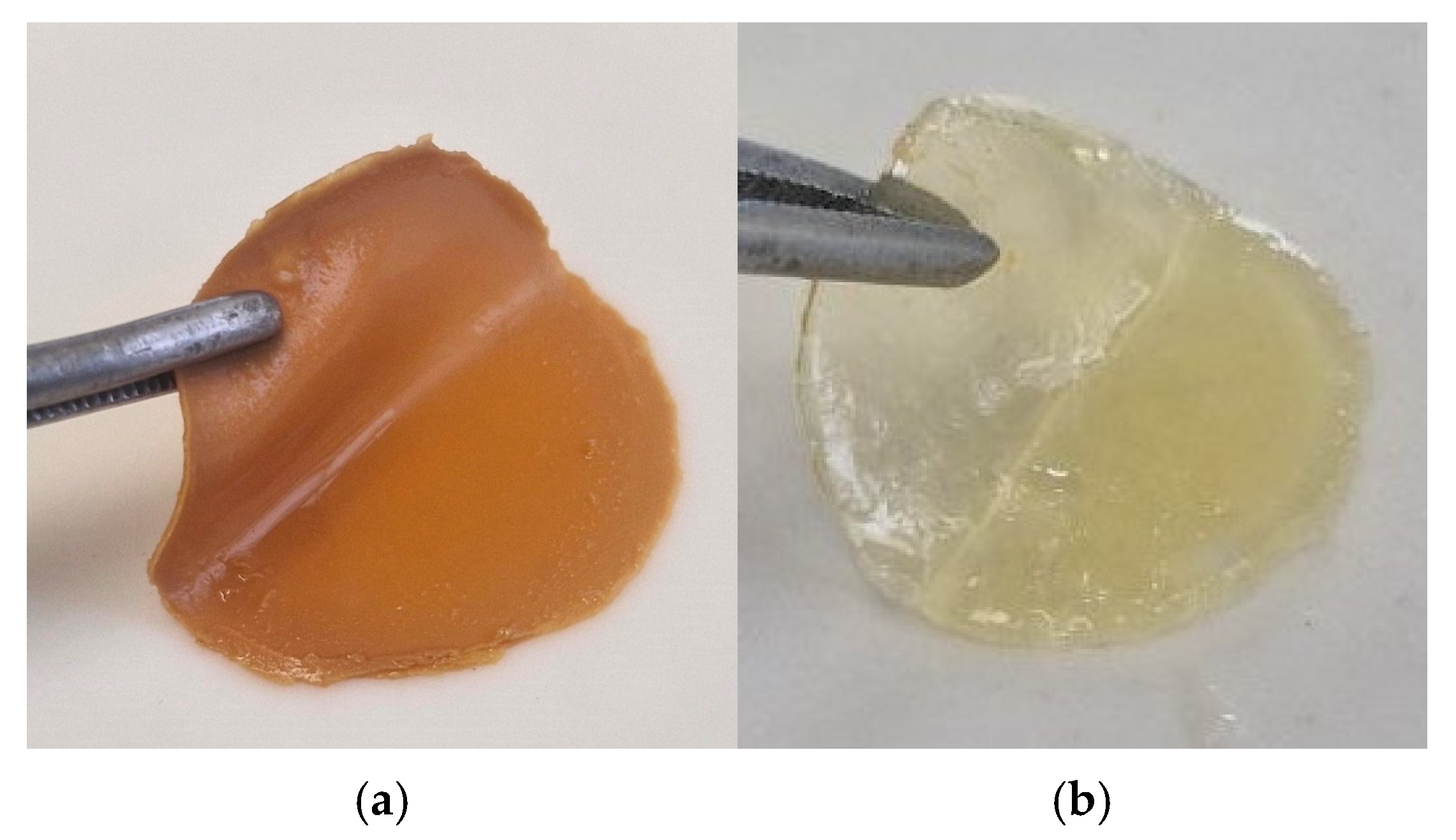

3.1. Sponge Plates for Wound Coverings Based on Fish Collagen

- for the “Coating No.1” sample, small amounts (at the level of 1% of the total mass of the starting substances) were not integrated into the matrix of the grafted copolymer PMMA-collagen, PMMA-pectin;

- for the “Coating No.2” sample, small amounts (at the level of 1% of the total mass of the starting substances) were not integrated into the matrix of the grafted copolymer PMMA-collagen and PEG;

- for both samples, insignificant amounts of low-molecular-weight collagen with MW ~10 kDa and ~20 kDa.

3.2. The Results of a Planimetric Assessment of the Repair Process of Burn Wounds in Rats During Their Treatment with Collagen Preparations

3.3. Results of Morphological Examination

3.4. Assessment of Microcirculation in the Healing Process of Burn Wounds

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sionkowska, A. Collagen blended with natural polymers: Recent advances and trends. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2021, 122, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Rodrigues, G.; Martins, G.; Henriques, C.; Silva, J.C. Evaluation of nanofibrous scaffolds obtained from blends of chitosan, gelatin and polycaprolactone for skin tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 102, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddamallappa, N.G.; Basavaraju, M.; Sionkowska, A.; Gowda, C.G.D. A review on synthetic polypeptide-based blends with other polymers: Emerging trends and advances. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 215, 113225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umemori, K.; Little, D. Impact of polymer degradation on cellular behavior in tissue engineering. Bioprinting 2025, 50, e00429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, M.; Liang, C.; Chen, Z.; Chen, A.; Cui, W. Development of fish collagen in tissue regeneration and drug delivery. Eng. Regen. 2022, 3, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M.; Zhong, J.; Lv, X.; Shen, X.; Fu, J.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Chen, C.; Xie, Q.; Xiong, S. Eco-engineered recombinant collagen III-PEG hydrogels with curcumin synergy for accelerated skin regeneration: A green crosslinking strategy in wound therapeutics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 325, 147324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, Y.; Mao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Fan, Z.; Yang, H.; Xia, A.; Zhang, X. Fish skin dressing for wound regeneration: A bioactive component review of omega-3 PUFAs, collagen and ECM. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinales, C.; Romero-Pena, M.; Calderon, G.; Vergara, K.; Caceres, P.J.; Castillo, P. Collagen, protein hydrolysates and chitin from by-products of fish and shellfish: An overview. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivic, N.; Bouzrati-Zerelli, M.; Kermagoret, A.; Dumur, F.; Fouassier, J.-P.; Gigmes, D.; Lalevée, J. Photocatalysts in polymerization reactions. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1617–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Nian, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z. Distinctive fish collagen drives vascular regeneration by polarizing macrophages to M2 phenotype via TNF-α/NF-κB pathway. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 35, 102273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kon, K.; Rai, M. Antibiotic Resistance: Mechanisms and New Antimicrobial Approaches; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; 436p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinemerem Nwobodo, D.; Ugwu, M.C.; Oliseloke Anie, C.; Al-Ouqaili, M.T.S.; Chinedu Ikem, J.; Victor Chigozie, U.; Saki, M. Antibiotic Resistance: The Challenges and Some Emerging Strategies for Tackling a Global Menace. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 2022, 36, e24655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Ju, H.; Tong, X.; Xu, F.; Zhang, J.; Gin, K.Y.-H. A comprehensive framework of health risk assessment for antibiotic resistance in aquatic environments: Status, progress, and perspectives. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 497, 139748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Generalova, A.N.; Dushina, A.O. Metal/metal oxide nanoparticles with antibacterial activity and their potential to disrupt bacterial biofilms: Recent advances with emphasis on the underlying mechanisms. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 345, 103626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, Y.T.; Rao, K.V.; Kumari, B.S.; Kumar, V.S.S.; Pavani, T. Synthesis of Fe3O4 nanoparticles and its antibacterial application. Int. Nano Lett. 2015, 5, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnat, B.; Kisielewska, A.; Marzec, M.; Jakubowski, W.; Szymanski, W.; Krok-Borkowicz, M.; Pamuta, E. Antibacterial metal ions doped in titanium dioxide sol-gel coatings: Which offers the best performance for biomedical applications? Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 31618–31631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M.; Ersatir, M.; Saleh, M.; Demirbag, B.; Yabalak, E.; Kilic, A. Boron Compounds as Key Drivers of Innovation: Exploring Their Role in Environmental Remediation, Sustainable Agriculture, Advanced Biomedical Applications, and Green Chemistry. J. Organomet. Chem. 2025, 1035, 123688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhad, M.; Chowdhury, M.; Khan, M.N.; Rahman, M.M. Metal nanoparticles incorporated chitosan-based electrospun nanofibre mats for wound dressing applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenycheva, L.; Chasova, V.; Matkivskaya, J.; Fukina, D.; Koryagin, A.; Belaya, T.; Grigoreva, A.; Kursky, Y.; Suleimanov, E. Features of Polymerization of Methyl Methacrylate using a Photocatalyst–the Complex Oxide RbTe1.5W0.5O6. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2021, 31, 3572–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasova, V.; Fukina, D.; Koryagin, A. Preparation of a Composite Material by Graft Copolymerization of Methylmethacrylate and Fish Gelatin Using a Photocatalyst—Complex Oxide RbTe1.5W0.5O6. Key Eng. Mater. 2021, 899, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenycheva, L.L.; Chasova, V.O.; Fukina, D.G.; Koryagin, A.V.; Valetova, N.B.; Suleimanov, E.V. Synthesis of Polymethyl-Methacrylate–Collagen-Graft Copolymer Using a Complex Oxide RbTe1.5W0.5O6Photocatalyst. Polym. Sci. Ser. D 2022, 15, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chasova, V.; Semenycheva, L.; Egorikhina, M.; Charykova, I.; Linkova, D.; Rubtsova, Y.; Fukina, D.; Koryagin, A.; Valetova, N.; Suleimanov, E. Cod Gelatin as an Alternative to Cod Collagen in Hybrid Materials for Regenerative Medicine. Macromol. Res. 2022, 30, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenycheva, L.; Chasova, V.; Fukina, D.; Koryagin, A.; Belousov, A.; Valetova, N.; Suleimanov, E. Photocatalytic Synthesis of Materials for Regenerative Medicine Using Complex Oxides with β-pyrochlore Structure. Life 2023, 13, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenycheva, L.; Chasova, V.; Sukhareva, A.; Fukina, D.; Koryagin, A.; Valetova, N.; Smirnova, O.; Suleimanov, E. New Composite Materials with Cross-Linked Structures Based on Grafted Copolymers of Acrylates on Cod Collagen. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, Y.L.; Lobanova, K.S.; Gushchina, K.S.; Vedernikova, N.V.; Rumyantseva, V.O.; Mitin, A.V.; Khmelevsky, K.P.; Vavilova, A.S.; Semenycheva, L.L. Features of formation of 3d-structures for regenerative medicine based on collagen, pectin and acrylic monomers in the presence of triethylboron complex with hexamethylenediamine. All Mater. Encycl. Ref. Book 2024, 10, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, Y.L.; Gushchina, K.S.; Prodaevich, V.V.; Yegorikhina, M.N.; Smirnova, O.N.; Vavilova, A.S.; Gubareva, K.S.; Charykova, I.N.; Rubtsova, Y.P.; Kovylina, T.A.; et al. Synthesis and properties of hydrogels based on collagen-pectin-methyl methacrylate copolymers synthesized in the presence of triethylborane. Uchen. Zap. Kazan. Univ. Ser. Nests. Sci. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Rumyantseva, V.; Semenycheva, L.; Valetova, N.; Egorikhina, M.; Farafontova, E.; Linkova, D.; Levicheva, E.; Fukina, D.; Suleimanov, E. Biocompatibility of New Hydrogels Based on a Copolymer of Fish Collagen and Methyl Methacrylate Obtained Using Heterogeneous Photocatalysis Under the Influence of Visible Light. Polymers 2025, 17, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukina, D.G.; Koryagin, A.V.; Koroleva, A.V.; Zhizhin, E.V.; Suleimanov, E.V.; Kirillova, N.I. Photocatalytic properties of β-pyrochlore RbTe1.5W0.5O6 under visible-light irradiation. J. Solid State Chem. 2021, 300, 122235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenycheva, L.L.; Astanina, M.V.; Kuznetsova, J.L.; Valetova, N.B.; Geras’kina, E.V.; Tarankova, O.A. Method for Production of Acetic Dispersion of High Molecular Fish Collagen. Patent RU, 2015, 2567171 C1, 10 November 2015. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2567171C1 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Khabriev, R.U. Guidelines for Experimental (Preclinical) Study of New Pharmacological Substances; Medicine Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2005; 832p. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, K.C.; Ma, H.; Liao, W.C.; Lee, C.K.; Lin, C.Y.; Chen, C.C. The optimal time for early burn wound excision to reduce pro–inflamatory cytokine production in a murine burn injury model. Burns 2010, 36, 1059–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakhomova, A.E.; Pakhomova, Y.V.; Pakhomova, E.E. New methods of experimental modeling thermal combustions of skin at laboratory animals, qualified to the principles of Good Laboratory Practice. J. Sib. Med. Sci. 2015, 3, 97. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Korzhevsky, D.E.; Gilyarov, A.V. Fundamentals of Histological Technique; SpetsLit Publishing House: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2010; 95p. [Google Scholar]

- Krupatkin, A.I. Clinical Neuroangiophysiology of Limbs (Perivascular Innervation and Nervous Trophism); Scientific World Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2003; 328p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupatkin, A.I.; Sidorov, V.V. Laser Doppler Flowmetry of Microcirculation; Medicine Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2005; 254p. [Google Scholar]

- Krupatkin, A.I.; Sidorov, V.V. Functional Diagnostics of the State of Microcirculatory-Tissue Systems: Fluctuations, Information, Nonlinearity: Guidance for Doctors; LIBROKOM Publishing House: Moscow, Russia, 2013; 496p. [Google Scholar]

| Group | 0 Day | 7 Days | 14 Days | 21 Days | 28 Days |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control 1 (without treatment) | 22.52 ± 0.71 | 21.55 ± 0.28 | 12.62 ± 0.15 | 4.34 ± 0.11 | 2.76 ± 0.03 |

| Control 2 (commercial coating) | 21.81 ± 0.53 | 20.93 ± 0.47 | 11.15 ± 0.09 | 3.83 ± 0.02 * | 1.31 ± 0.02 * |

| Experience 1 (Coating No.1) | 21.96 ± 1.02 | 17.91 ± 0.52 */∆ | 8.21 ± 0.12 */∆ | 2.70 ± 0.04 */∆ | 0 (scar) */∆ |

| Experience 2 (Coating No.2) | 22.30 ± 0.72 | 20.04 ± 0.67 | 10.43 ± 0.38 * | 3.32 ± 0.05 */∆ | 0.68 ± 0.01 */∆ |

| Group | MI, perf.un. | E, RVU | N, RVU | M, RVU | R, RVU | C, RVU | BI, perf.un. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact rats | 9.45 ± 0.85 | 12.93 ± 1.15 | 9.15 ± 0.86 | 8.37 ± 0.81 | 5.80 ± 0.49 | 3.33 ± 0.27 | 1.14 ± 0.08 |

| Control 1, 0 days | 4.86 ± 0.52 * | 14.73 ± 1.28 | 11.02 ± 0.93 | 11.74 ± 0.77 * | 8.26 ± 0.52 * | 4.99 ± 0.28 * | 0.92 ± 0.03 * |

| Control 1, 28 days | 6.99 ± 0.51 * | 13.07 ± 1.12 | 10.29 ± 1.13 | 10.04 ± 1.36 | 7.48 ± 0.65 * | 4.12 ± 0.36 | 0.98 ± 0.01 |

| Control 2, 0 days | 5.01 ± 0.39 * | 13.81 ± 1.05 | 10.87 ± 0.93 | 12.02 ± 1.34 * | 7.96 ± 0.83 * | 5.04 ± 0.20 * | 0.92 ± 0.05 * |

| Control 2, 28 days | 7.91 ± 0.46 | 12.85 ± 1.03 | 10.03 ± 0.42 | 9.83 ± 0.56 | 6.27 ± 0.16 | 3.85 ± 0.22 | 1.03 ± 0.02 |

| Experience 1, 0 days | 4.95 ± 0.37 * | 14.56 ± 1.23 | 10.92 ± 0.65 | 12.13 ± 0.83 * | 8.51 ± 0.47 * | 4.73 ± 0.16 * | 0.91 ± 0.03 * |

| Experience 1, 28 days | 8.76 ± 0.53 Δ | 14.02 ± 1.11 | 9.48 ± 0.37 | 9.24 ± 0.61 | 6.35 ± 0.42 | 3.50 ± 0.17 | 0.98 ± 0.07 |

| Experience 2, 0 days | 4.53 ± 0.48 * | 13.59 ± 1.04 | 11.65 ± 1.23 | 10.84 ± 1.32 | 8.64 ± 0.33 * | 5.12 ± 0.11 * | 0.94 ± 0.02 * |

| Experience 2, 28 days | 8.44 ± 0.61 Δ | 13.76 ± 1.27 | 10.48 ± 0.72 | 9.23 ± 0.36 | 6.12 ± 0.30 | 3.88 ± 0.29 | 1.11 ± 0.03 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Soloveva, A.; Semenycheva, L.; Rumyantseva, V.; Kuznetsova, Y.; Prodaevich, V.; Valetova, N.; Peretyagin, P.; Didenko, N.; Belyaeva, K.; Fukina, D.; et al. Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Safety of New Wound Coatings Based on Cod Collagen for Fast Healing of Burn Surfaces. Polymers 2025, 17, 3215. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233215

Soloveva A, Semenycheva L, Rumyantseva V, Kuznetsova Y, Prodaevich V, Valetova N, Peretyagin P, Didenko N, Belyaeva K, Fukina D, et al. Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Safety of New Wound Coatings Based on Cod Collagen for Fast Healing of Burn Surfaces. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3215. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233215

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoloveva, Anna, Lyudmila Semenycheva, Victoria Rumyantseva, Yulia Kuznetsova, Veronika Prodaevich, Natalia Valetova, Petr Peretyagin, Natalia Didenko, Ksenia Belyaeva, Diana Fukina, and et al. 2025. "Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Safety of New Wound Coatings Based on Cod Collagen for Fast Healing of Burn Surfaces" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3215. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233215

APA StyleSoloveva, A., Semenycheva, L., Rumyantseva, V., Kuznetsova, Y., Prodaevich, V., Valetova, N., Peretyagin, P., Didenko, N., Belyaeva, K., Fukina, D., Vedunova, M., & Suleimanov, E. (2025). Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Safety of New Wound Coatings Based on Cod Collagen for Fast Healing of Burn Surfaces. Polymers, 17(23), 3215. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233215