Vegetable-Oil-Loaded Microcapsules for Self-Healing Polyurethane Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

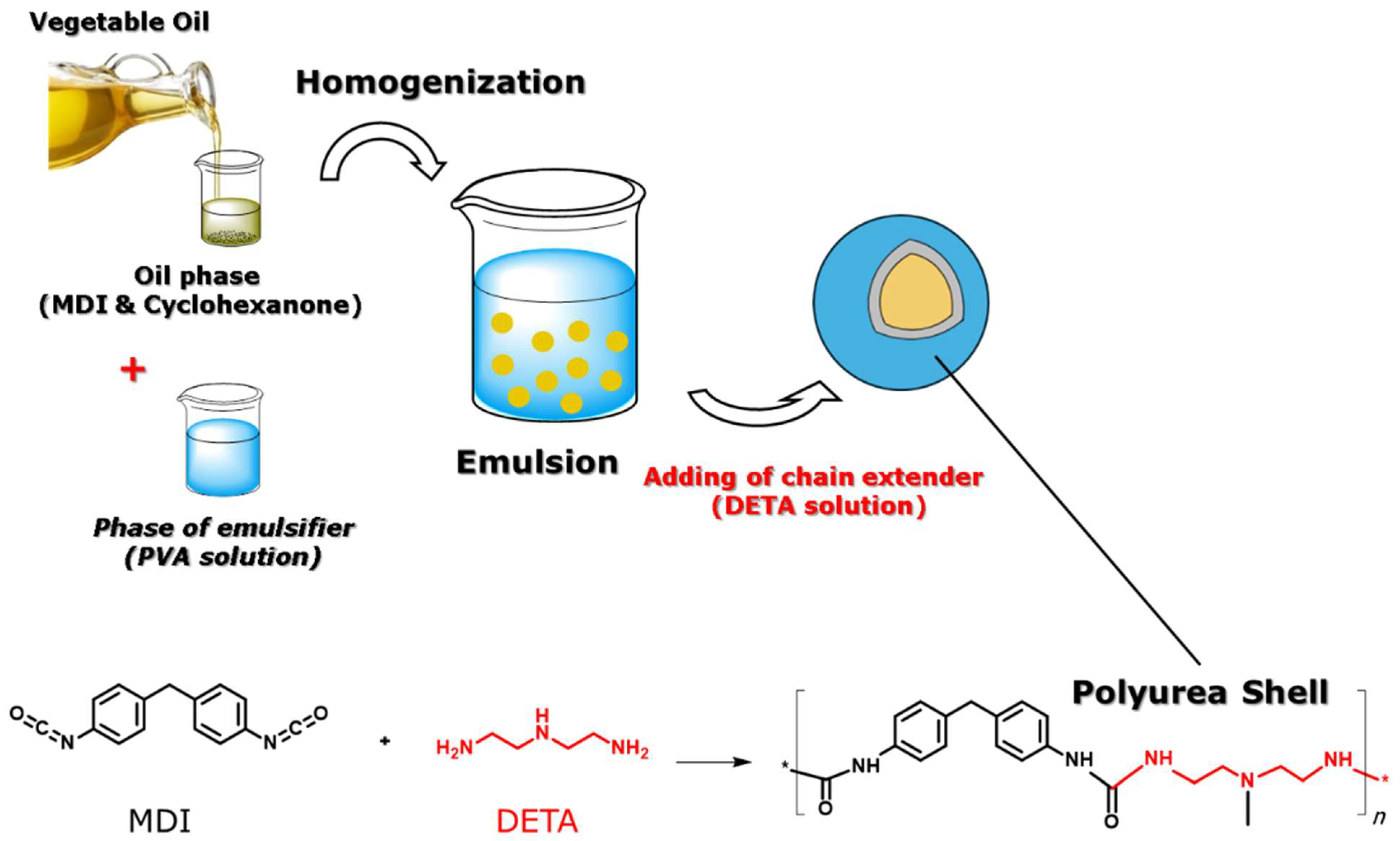

2.2. Synthesis of VO-MCs

2.3. Extraction of Encapsulated Oil (wt.%) from VO-MCs

2.4. Calibration Curves and Quantification of Encapsulated Oil (wt.%) in VO-MCs

2.5. Preparation of Coatings

2.6. Self-Healing Tests

2.7. Anticorrosion Protection Tests

2.8. Characterization

2.9. Determination of Isocyanate Content

3. Results

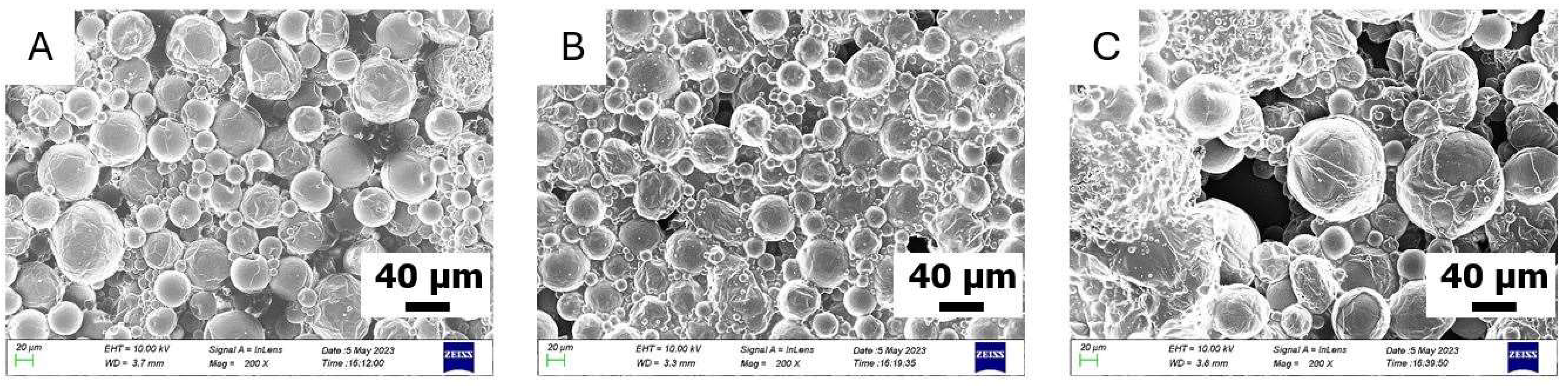

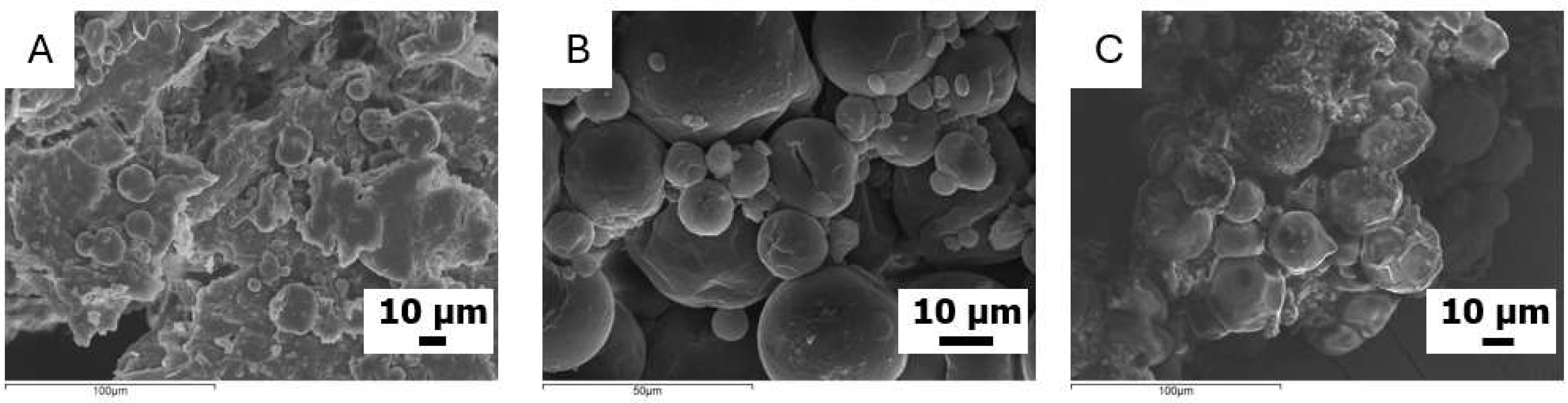

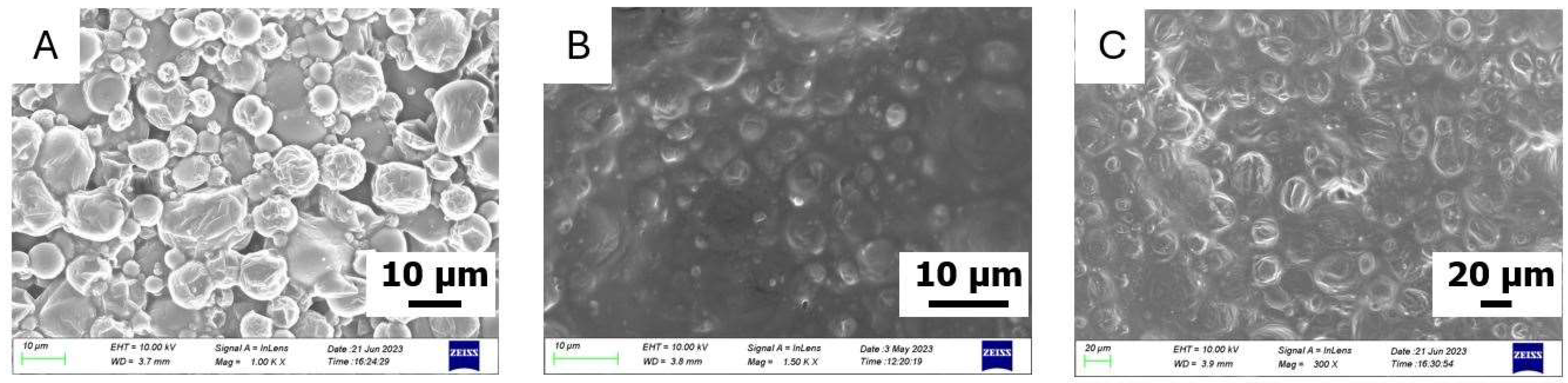

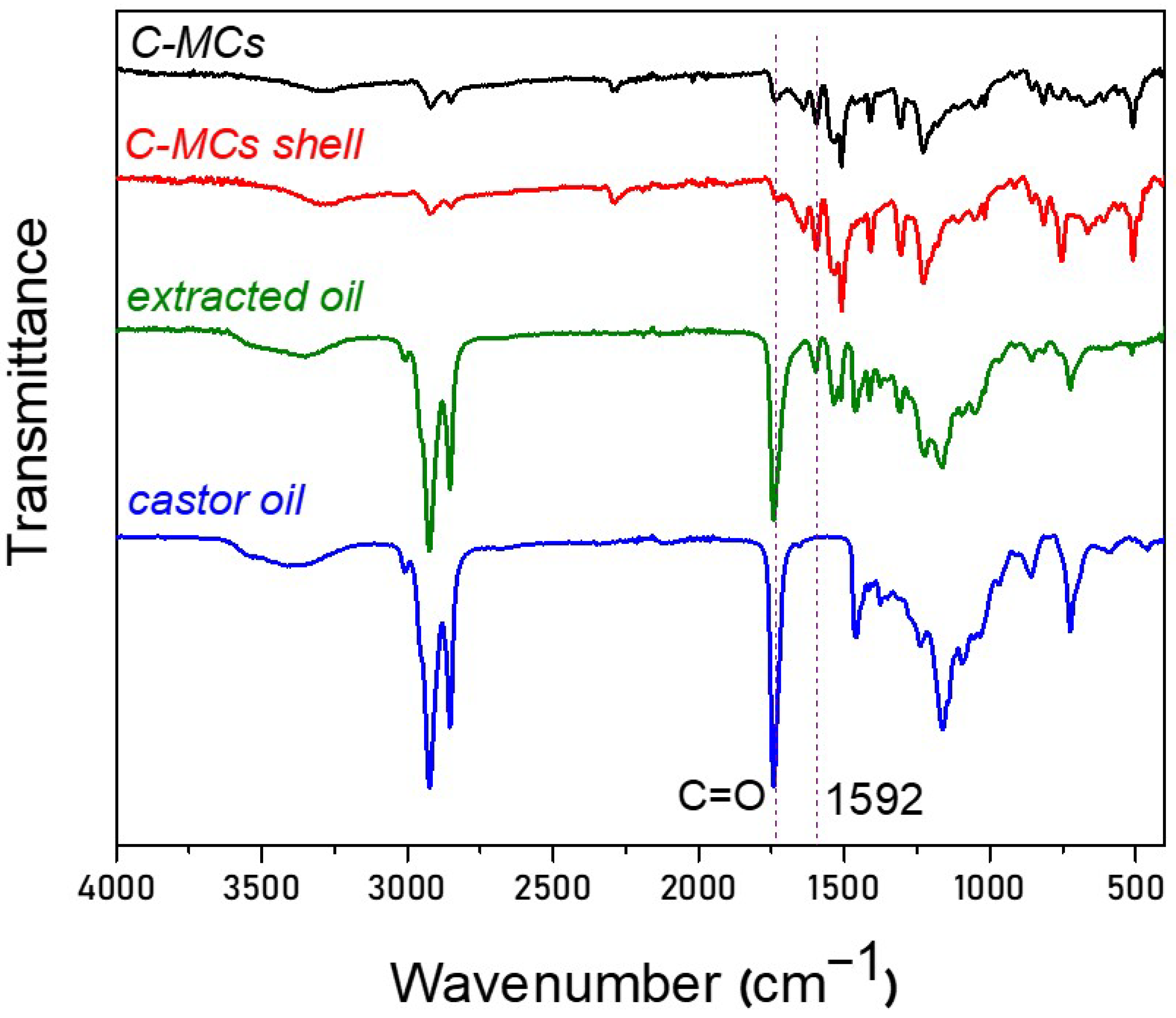

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of VO-MCs

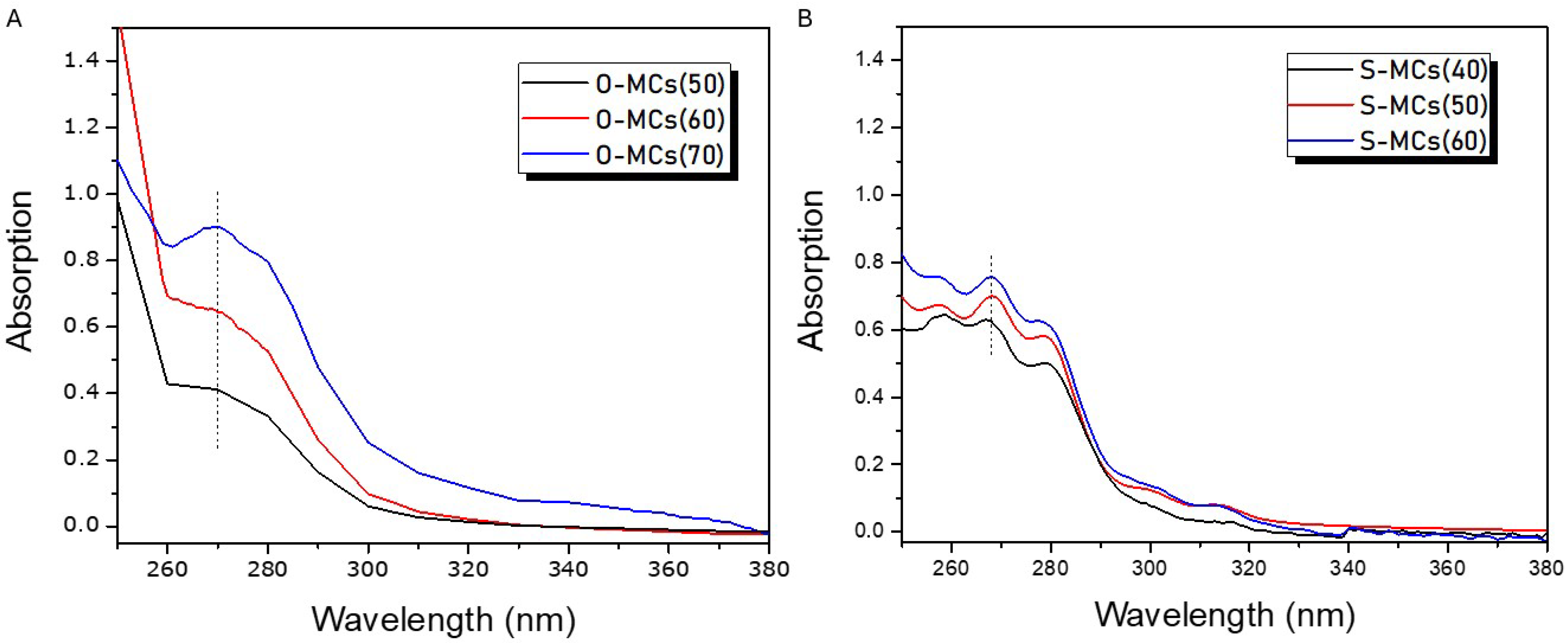

3.2. Determination of Encapsulated Oil in VO-MCs

3.2.1. Olive and Soybean Oil

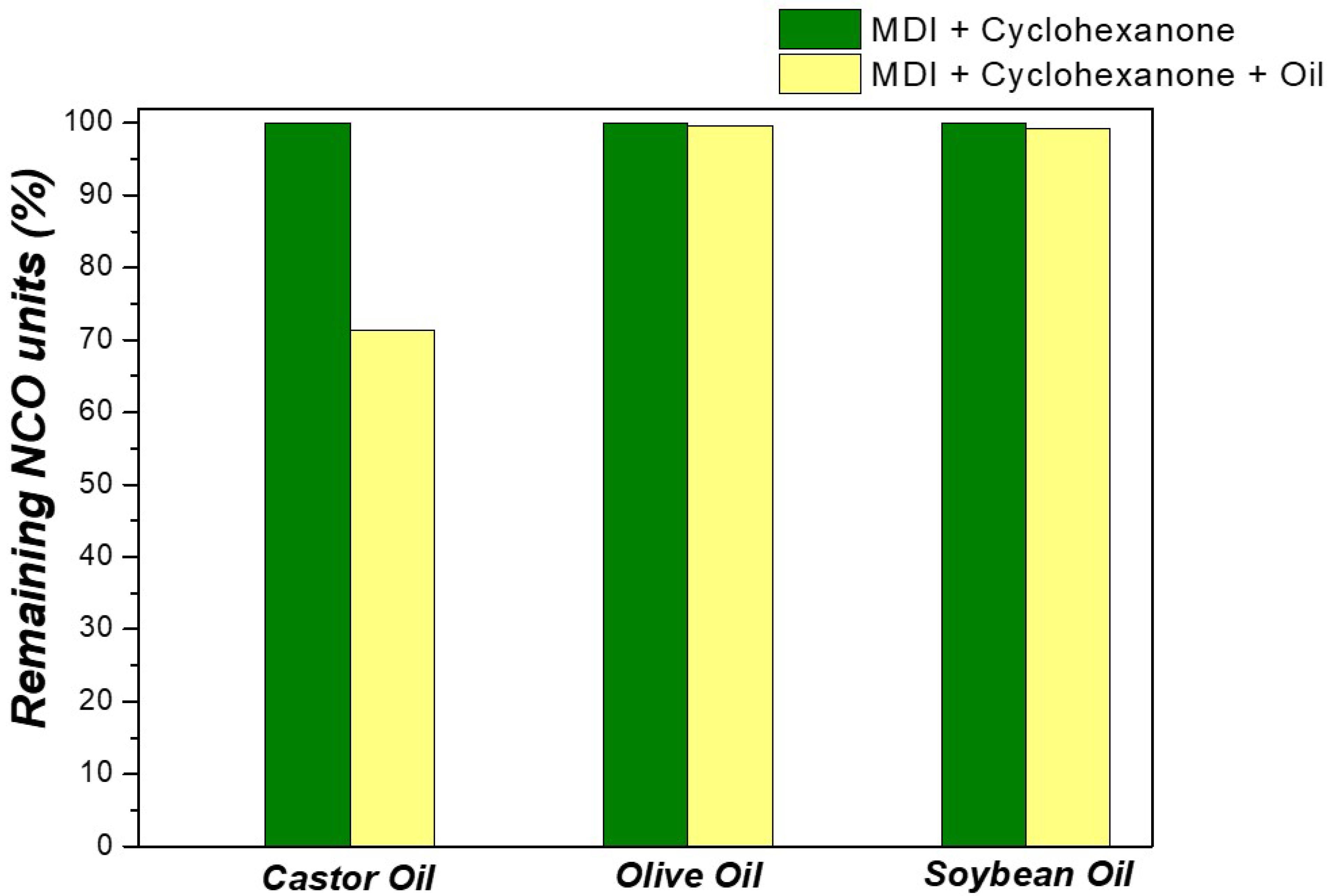

3.2.2. Castor Oil

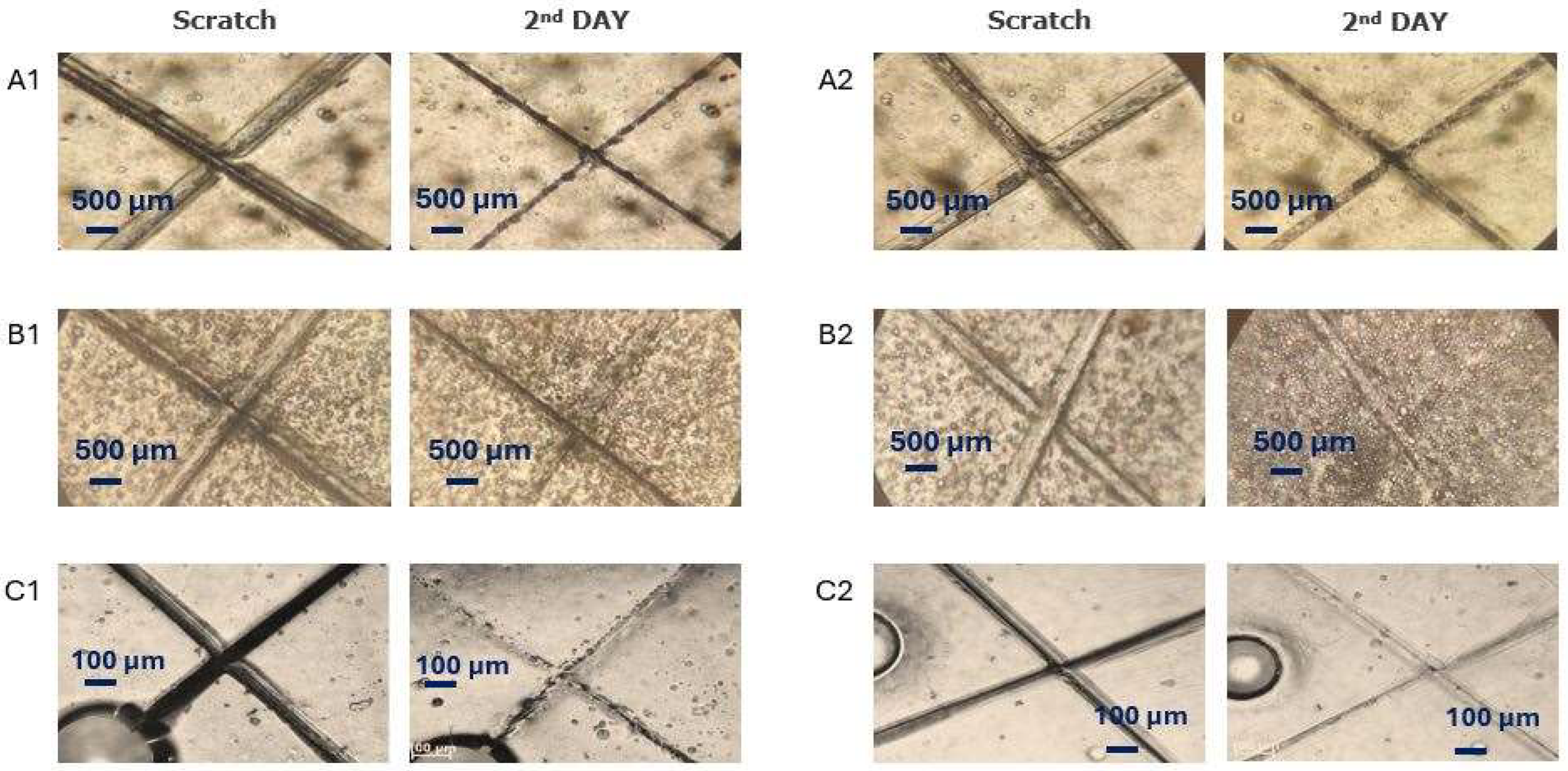

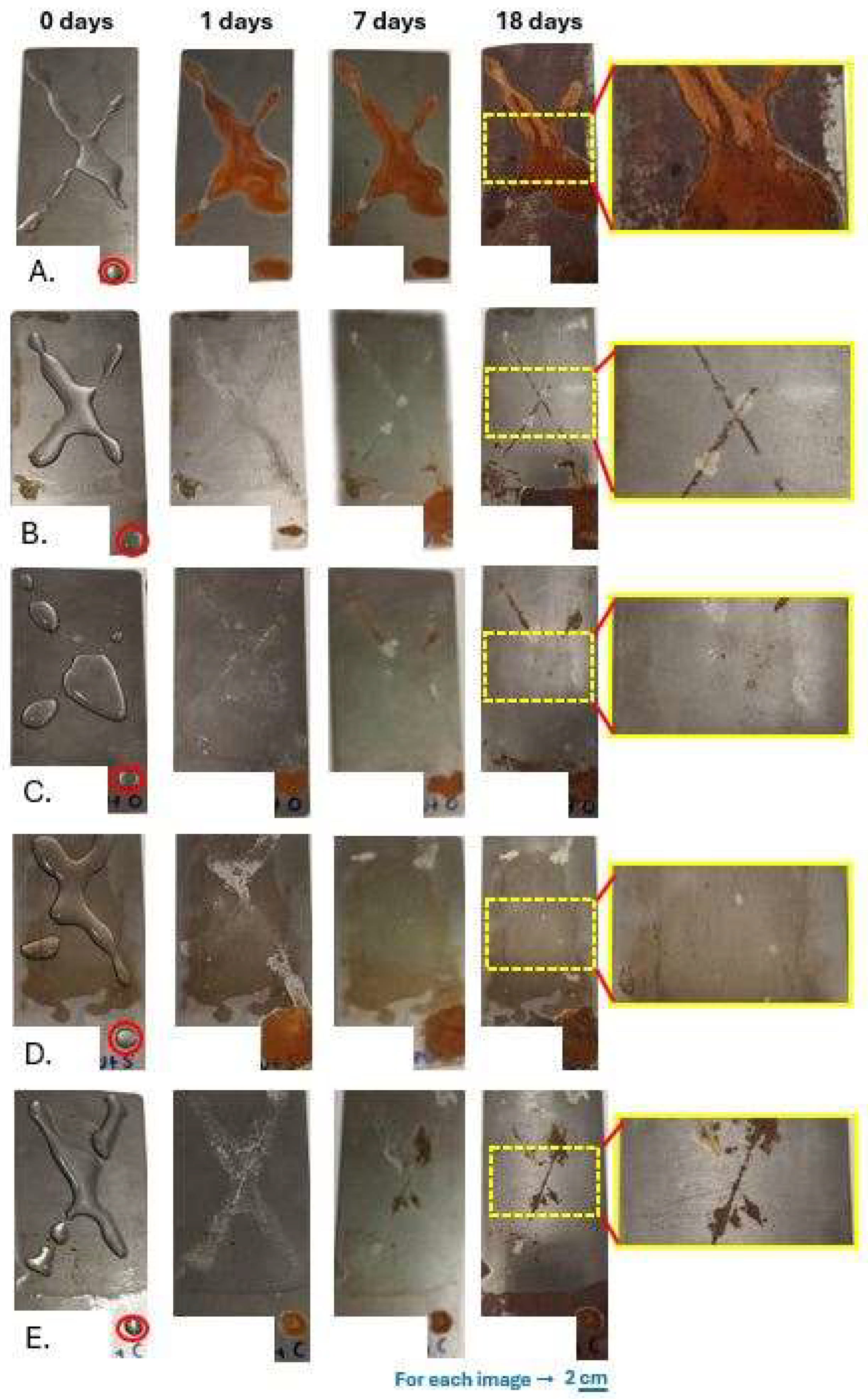

3.3. Self-Healing Properties and Anticorrosion Test

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamid, Y.; Fat’hi, M.R. A Novel Cationic Surfactant-Assisted Switchable Solvent-Based Dispersive Liquid–Liquid Microextraction for Determination for Orange II in Food Samples. Food Anal. Methods 2018, 11, 2131–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Han, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y. Recent advances in the sustained-release technology for improving the antifungal potential of essential oil in food preservation. J. Future Foods 2026, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patravale, V.B.; Mandawgade, S.D. Novel cosmetic delivery systems: An application update. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2008, 30, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boh Podgornik, B.; Šandrić, S.; Kert, M. Microencapsulation for Functional Textile Coatings with Emphasis on Biodegradability—A Systematic Review. Coatings 2021, 11, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, M. 8—A review on application of encapsulation in agricultural processes. In Encapsulation of Active Molecules and Their Delivery System; Sonawane, S.H., Bhanvase, B.A., Sivakumar, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casanova, F.; Santos, L. Encapsulation of cosmetic active ingredients for topical application—A review. J. Microencapsul. 2016, 33, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongnuanchan, P.; Benjakul, S. Essential Oils: Extraction, Bioactivities, and Their Uses for Food Preservation. J. Food Sci. 2014, 79, R1231–R1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Chemistry and Biology of Volatiles. Available online: https://download.e-bookshelf.de/download/0000/5959/65/L-X-0000595965-0001311315.XHTML/index.xhtml (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Weerawatanakorn, M.; Wu, J.-C.; Pan, M.-H.; Ho, C.-T. Reactivity and stability of selected flavor compounds. J. Food Drug Anal. 2015, 23, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, M.; He, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Li, W. Microencapsulation of oil soluble polyaspartic acid ester and isophorone diisocyanate and their application in self-healing anticorrosive epoxy resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cui, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H. Fabrication of microcapsules containing dual-functional tung oil and properties suitable for self-healing and self-lubricating coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 115, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Guo, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Fang, B.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Liu, J. Self-healing performance and anti-corrosion mechanism of microcapsule-containing epoxy coatings under deep-sea environment. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 203, 109176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, Q. Evaluation and failure analysis of linseed oil encapsulated self-healing anticorrosive coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 118, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Wang, X.; Zou, F.; Tian, W.; Zhong, Y.; Ma, C. Facile preparation of function-coupled microcapsules for organic contaminants adsorption and self-healing corrosion resistance. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xie, W.; Yang, Q.; Cao, Y.; Ren, J.; Almalki, A.S.A.; Xu, Y.; Cao, T.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Guo, Z. Self-healing anti-corrosive coating using graphene/organic cross-linked shell isophorone diisocyanate microcapsules. React. Funct. Polym. 2024, 202, 106000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotovvat, B.; Behzadnasab, M.; Mirabedini, S.M.; Mohammadloo, H.E. Anti-corrosion performance and mechanical properties of epoxy coatings containing microcapsules filled with linseed oil and modified ceria nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 648, 129157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolini, N.A.; Cordeiro Neto, A.G.; Pellanda, A.C.; Carvalho Jorge, A.R.D.; Barros Soares, B.D.; Floriano, J.B.; Berton, M.A.C.; Vijayan, P.P.; Thomas, S. Evaluation of Corrosion Protection of Self-Healing Coatings Containing Tung and Copaiba Oil Microcapsules. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 2021, 6650499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzin, S.H. Mechanism of Extrinsic and Intrinsic Self-healing in Polymer Systems. In Multifunctional Epoxy Resins: Self-Healing, Thermally and Electrically Conductive Resins; Hameed, N., Capricho, J.C., Salim, N., Thomas, S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 107–138. [Google Scholar]

- Szafraniec-Szczęsny, J.; Janik-Hazuka, M.; Odrobińska, J.; Zapotoczny, S. Polymer Capsules with Hydrophobic Liquid Cores as Functional Nanocarriers. Polymers 2020, 12, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, G.; Qi, X.; Shi, J.; Tian, J.; Xiao, H. Toughened and self-healing carbon nanotube/epoxy resin composites modified with polycaprolactone filler for coatings, adhesives and FRP. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 111, 113207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterova, T.; Dam-Johansen, K.; Pedersen, L.T.; Kiil, S. Microcapsule-based self-healing anticorrosive coatings: Capsule size, coating formulation, and exposure testing. Prog. Org. Coat. 2012, 75, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yang, J. Facile microencapsulation of HDI for self-healing anticorrosion coatings. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 11123–11130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakry, A.M.; Abbas, S.; Ali, B.; Majeed, H.; Abouelwafa, M.Y.; Mousa, A.; Liang, L. Microencapsulation of Oils: A Comprehensive Review of Benefits, Techniques, and Applications. Comp. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2016, 15, 143–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behzadnasab, M.; Mirabedini, S.M.; Esfandeh, M.; Farnood, R.R. Evaluation of corrosion performance of a self-healing epoxy-based coating containing linseed oil-filled microcapsules via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 105, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, C.; Borsotto, P.; Barbieri, C.; Borsotto, P. Essential Oils: Market and Legislation. In Potential of Essential Oils; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Shi, H.; Liu, F.; Han, E.-H. Self-healing epoxy coating based on tung oil-containing microcapsules for corrosion protection. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 156, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samadzadeh, M.; Boura, S.H.; Peikari, M.; Ashrafi, A.; Kasiriha, M. Tung oil: An autonomous repairing agent for self-healing epoxy coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2011, 70, 383–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryanarayana, C.; Rao, K.C.; Kumar, D. Preparation and characterization of microcapsules containing linseed oil and its use in self-healing coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2008, 63, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdipour, H.; Rezaei, M.; Abbasi, F. Synthesis and characterization of high durable linseed oil-urea formaldehyde micro/nanocapsules and their self-healing behaviour in epoxy coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 124, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Xu, S. Investigation on the restoration properties of wood oil microcapsules in wood coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 197, 108853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Chen, F.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Xing, X.; Li, Z. Anticorrosion healing properties of epoxy coating with poly(urea–formaldehyde) microcapsules encapsulated linseed oil and benzotriazole. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2023, 20, 1977–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.; Zhou, Q. Synthesis and characterization of poly(urea-formaldehyde) microcapsules containing linseed oil for self-healing coating development. Prog. Org. Coat. 2017, 105, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, M.; Li, H. Preparation of Tung Oil-Loaded PU/PANI Microcapsules and Synergetic Anti-Corrosion Properties of Self-Healing Epoxy Coatings. Macro. Mater. Eng. 2021, 306, 2000581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, Y.; Song, G.; Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Luo, X.; Yin, H.; et al. Mechanically robust, super tough and ultrastretchable self-healing polyurethane constructed from multiple asymmetric hydrogen bonds. Polymer 2025, 319, 128022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghayegh, M.; Mirabedini, S.M.; Yeganeh, H. Preparation of microcapsules containing multi-functional reactive isocyanate-terminated-polyurethane-prepolymer as healing agent, part II: Corrosion performance and mechanical properties of a self healing coating. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 50874–50886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatiya, P.D.; Mahulikar, P.P.; Gite, V.V. Designing of polyamidoamine-based polyurea microcapsules containing tung oil for anticorrosive coating applications. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2016, 13, 715–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, D.; Wu, D.; Huang, K. Self-healing polyurethane based on a substance supplement and dynamic chemistry: Repair mechanisms and applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 141, e55007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanawala, K.; Khanna, A.S.; Raman, R.K.S. Development of Self-Healing Coatings Using Encapsulated Linseed Oil and Tung Oil as Healing Agents. In Proceedings of the CORROSION, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–10 March 2016. NACE-2016-7310. [Google Scholar]

- Thanawala, K.; Mutneja, N.; Khanna, A.S.; Raman, R.K.S. Development of Self-Healing Coatings Based on Linseed Oil as Autonomous Repairing Agent for Corrosion Resistance. Materials 2014, 7, 7324–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomić, N.Z.; Mustapha, A.N.; AlMheiri, M.; AlShehhi, N.; Antunes, A. Advanced application of drying oils in smart self-healing coatings for corrosion protection: Feasibility for industrial application. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 172, 107070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhou, Z.; Qin, L.; Yu, C.; Zhang, F. Preparation of PVA/PU/PUA microcapsules and application in self-healing two-component waterborne polyurethane coatings. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2022, 19, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatiya, P.D.; Hedaoo, R.K.; Mahulikar, P.P.; Gite, V.V. Novel Polyurea Microcapsules Using Dendritic Functional Monomer: Synthesis, Characterization, and Its Use in Self-healing and Anticorrosive Polyurethane Coatings. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 1562–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhi, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, J.; Cao, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, G.; Lu, C.; Lu, X. Preparation and properties of double-layer phenolic/polyurethane coated isophorone diisocyanate self-healing microcapsules. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.N.; Kessler, M.R.; Sottos, N.R.; White, S.R. In situ poly(urea-formaldehyde) microencapsulation of dicyclopentadiene. J. Microencapsul. 2003, 20, 719–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avdeliodi, E.; Soto Beobide, A.; Voyiatzis, G.A.; Bokias, G.; Kallitsis, J.K. Novolac-based microcapsules containing isocyanate reagents for self-healing applications. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 173, 107204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeliodi, E.; Tsioli, A.; Bokias, G.; Kallitsis, J.K. Controlling the Synthesis of Polyurea Microcapsules and the Encapsulation of Active Diisocyanate Compounds. Polymers 2024, 16, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Hong, C.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, C. Multifunctional waterborne polyurethane coating constructed by phloretin: Integrating high robustness, self-healing, UV resistance, and anticorrosion, applied to leather finish. Prog. Org. Coat. 2025, 207, 109430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oz, K.; Merav, B.; Sara, S.; Yael, D. Volatile Organic Compound Emissions from Polyurethane Mattresses under Variable Environmental Conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 9171–9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, A.; Shi, L.; Shi, H.; Qian, J.; Shi, Y. Role of the Soft and Hard Segments Structure in Modifying the Performance of Acrylic Adhesives Modified by Polyurethane Macromonomers. ACS Omega 2024, 30, 32735–32744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, T.; Sun, F.; Li, S.; Geng, Y.; Yao, B.; Xu, J.; Fu, J. Bio-inspired self-healing and anti-corrosion waterborne polyurethane coatings based on highly oriented graphene oxide. Npj Mater. Degrad. 2023, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Jin, Y.; Fan, W.; Zhou, R. A review on room-temperature self-healing polyurethane: Synthesis, self-healing mechanism and application. J. Leather Sci. Eng. 2022, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, T.; Wang, K.; Wang, C.; Sun, H. Preparation of self-healing coatings based on pH-responsive microcapsules containing healing agents and corrosion inhibitors. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 69, 106752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Method-COI-T. 20-Doc.-No-19-Rev.-5-2019-2.pdf. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Method-COI-T.20-Doc.-No-19-Rev.-5-2019-2.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Godoy, A.C.; Dos Santos, P.D.S.; Nakano, A.Y.; Bini, R.A.; Siepmann, D.A.B.; Schneider, R.; Gaspar, P.A.; Pfrimer, F.W.D.; Da Paz, R.F.; Santos, O.O. Analysis of Vegetable Oil from Different Suppliers by Chemometric Techniques to Ensure Correct Classification of Oil Sources to Deal with Counterfeiting. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 13, 1138–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; An, J.; Wu, G.; Yang, J. Double-layered reactive microcapsules with excellent thermal and non-polar solvent resistance for self-healing coatings. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 4435–4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2572; Standard Test Method for Isocyanate Groups in Urethane Materials or Prepolymers. World Trade Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Wang, G.; Li, K.; Zou, W.; Hu, A.; Hu, C.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, C.; Guo, G.; Yang, A.; Drumright, R.; et al. Synthesis of HDI/IPDI hybrid isocyanurate and its application in polyurethane coating. Prog. Org. Coat. 2015, 78, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Sun, X.; Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Lin, J. Fabrication of a high-strength hydrogel with an interpenetrating network structure. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 346, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Jiang, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, M. Facile and cost-effective synthesis of isocyanate microcapsules via polyvinyl alcohol-mediated interfacial polymerization and their application in self-healing materials. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2017, 138, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/2104 of 29 July 2022 Supplementing Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Par-Liament and of the Council as Regards Marketing Standards for Olive Oil, and Repealing Commission Regulation (EEC) No 2568/91 and Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 29/2012; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; Volume 284, Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_del/2022/2104/oj (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Boskou, D. Food Chemistry; Gartaganis: Stemnitsa, Greece, 1986; Available online: https://www.bookstation.gr/Product.asp?ID=31652 (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Monfreda, M.; Gobbi, L.; Grippa, A. Blends of olive oil and sunflower oil: Characterisation and olive oil quantification using fatty acid composition and chemometric tools. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 2283–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nill, K. Soy Beans: Properties and Analysis. In Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, P. Safety Assessment of Ricinus Communis (Castor) Seed Oil and Ricinoleates as Used in Cosmetics. Available online: https://www.cir-safety.org/sites/default/files/Castor%20Oil.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Lu, H.; Tian, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Guan, R.; Wang, H. Water Polishing improved controlled-release characteristics and fertilizer efficiency of castor oil-based polyurethane coated diammonium phosphate. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Song, S.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Zhou, C.; Du, L.; Sun, D.; Li, P. Hydrophobic modification of castor oil-based polyurethane coated fertilizer to improve the controlled release of nutrient with polysiloxane and halloysite. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 165, 106756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Zhang, Q.; Fu, Q.; Yu, J.; Huang, X. Preparation and properties of polytetrafluoroethylene superhydrophobic surface. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 670, 131574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Du, X.; Cheng, X.; Wang, H.; Du, Z. Room-temperature self-healable and stretchable waterborne polyurethane film fabricated via multiple hydrogen bonds. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 151, 106081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, R.; Zhang, J.; Li, J.; Hong, C.; Xu, Y.; Song, Q.; Zhou, C. Self-Healing and Recyclable Waterborne Polyurethane With Ultra-High Toughness Based on Dynamic Covalent and Hydrogen Bonds. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, e56982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Xu, T. Water-assisted self-healing of polymeric materials. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 217, 113310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-M.; Song, I.-H.; Choi, J.-Y.; Jin, S.-W.; Nam, K.-N.; Chung, C.-M. Self-Healing Coatings Based on Linseed-Oil-Loaded Microcapsules for Protection of Cementitious Materials. Coatings 2018, 8, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sun, Z.; Jiao, S.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.; Meng, X.; Zhang, B.; Han, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, Y.; et al. Dual-Shell Microcapsules for High-Response Efficiency Self-Healing of Multi-Scale Damage in Waterborne Polymer–Cement Coatings. Polymers 2024, 16, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasina, O.O.; Hallman, H.; Craig-Schmidt, M.; Clements, C. Predicting temperature-dependence viscosity of vegetable oils from fatty acid composition. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2006, 83, 899–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthäus, B. Oxidation of edible oils. In Oxidation in Foods and Beverages and Antioxidant Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 183–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kalogianni, E.P.; Karapantsios, T.D.; Miller, R. Effect of repeated frying on the viscosity, density and dynamic interfacial tension of palm and olive oil. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogianni, E.P.; Karastogiannidou, C.; Karapantsios, T.D. Effect of potato presence on the degradation of extra virgin olive oil during frying. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Vegetable Oil | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | |

| Olive oil | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Soybean oil | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Castor oil | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✕ | ✕ | |

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | O-MCs(50) | O-MCs(60) | O-MCs(70) | S-MCs(40) | S-MCs(50) | S-MCs(60) |

| 50% | 60% | 70% | 40% | 50% | 60% | |

| P | 44% | 60% | 66% | 38% | 51% | 58% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Avdeliodi, E.; Derizioti, S.; Papadopoulou, I.; Arvaniti, A.; Krassa, K.; Kalogianni, E.P.; Kallitsis, J.K.; Bokias, G. Vegetable-Oil-Loaded Microcapsules for Self-Healing Polyurethane Coatings. Polymers 2025, 17, 3184. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233184

Avdeliodi E, Derizioti S, Papadopoulou I, Arvaniti A, Krassa K, Kalogianni EP, Kallitsis JK, Bokias G. Vegetable-Oil-Loaded Microcapsules for Self-Healing Polyurethane Coatings. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3184. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233184

Chicago/Turabian StyleAvdeliodi, Efterpi, Sofia Derizioti, Ioanna Papadopoulou, Aikaterini Arvaniti, Kalliopi Krassa, Eleni P. Kalogianni, Joannis K. Kallitsis, and Georgios Bokias. 2025. "Vegetable-Oil-Loaded Microcapsules for Self-Healing Polyurethane Coatings" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3184. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233184

APA StyleAvdeliodi, E., Derizioti, S., Papadopoulou, I., Arvaniti, A., Krassa, K., Kalogianni, E. P., Kallitsis, J. K., & Bokias, G. (2025). Vegetable-Oil-Loaded Microcapsules for Self-Healing Polyurethane Coatings. Polymers, 17(23), 3184. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233184