High-Tg Vat Photopolymerization Materials Based on In Situ Sequential Interpenetrating Polymer Networks of Maleimide and Cyanate Ester Monomers

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Resin Preparation

2.3. Experimental Procedures and Characterizations

3. Results and Discussion

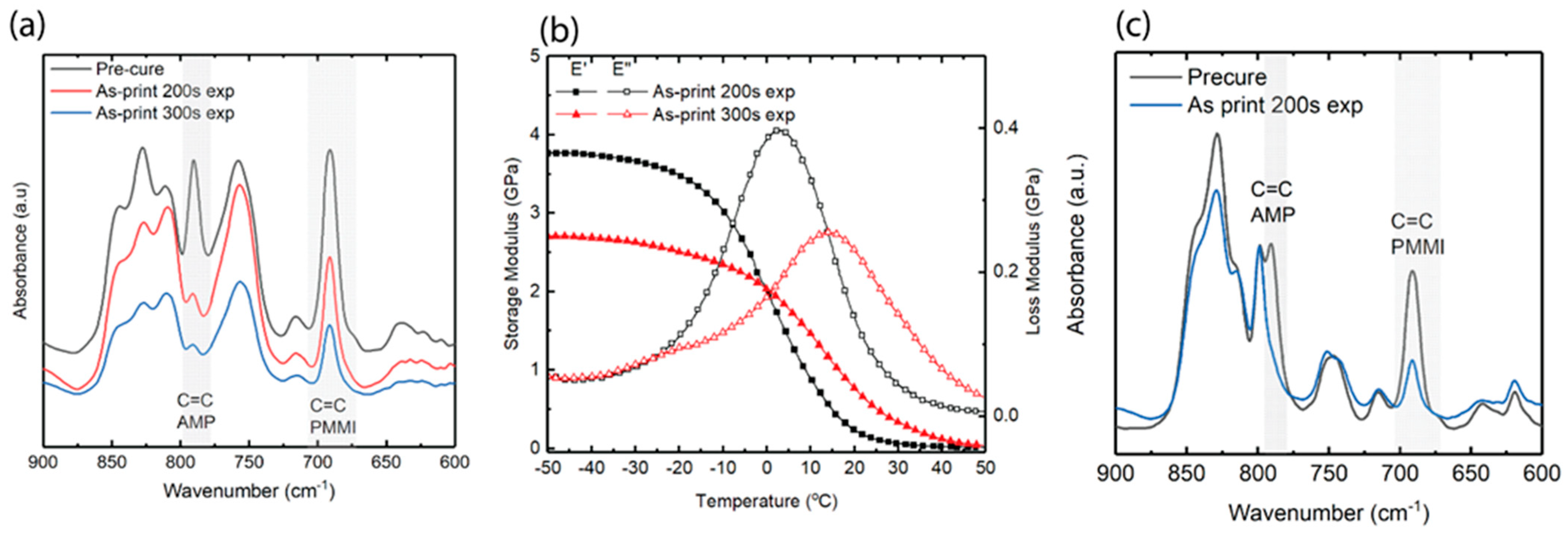

3.1. Selection of Resin and Exposure Time

3.2. Thermomechanical Properties of PMMI-AMP Systems

3.3. Thermomechanical Properties of IPN Systems

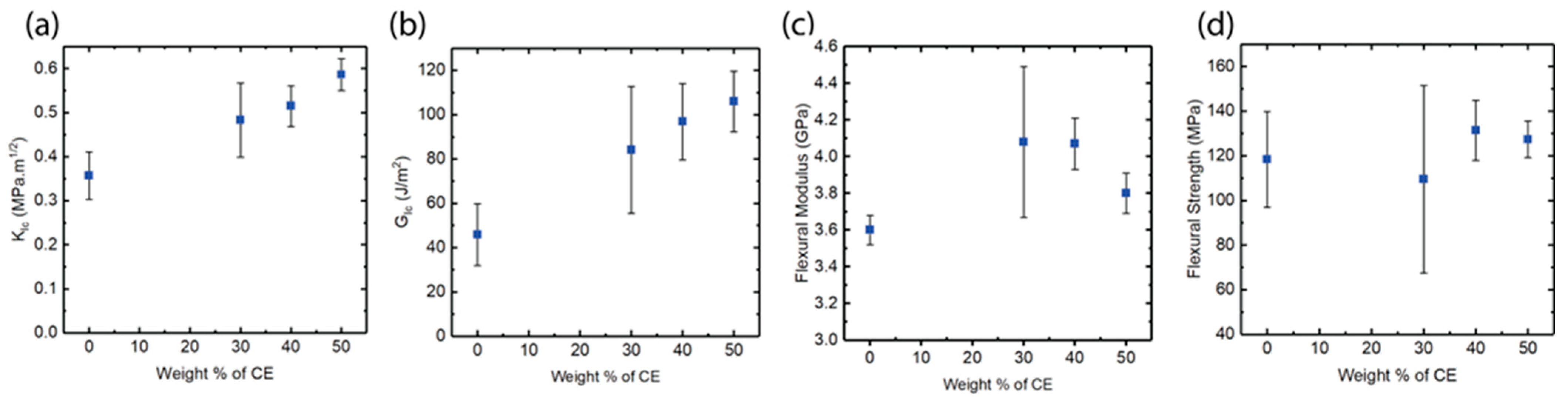

3.4. Mechanical Properties of IPN vs. PMMI-AMP Systems

3.5. Density Change upon Curing

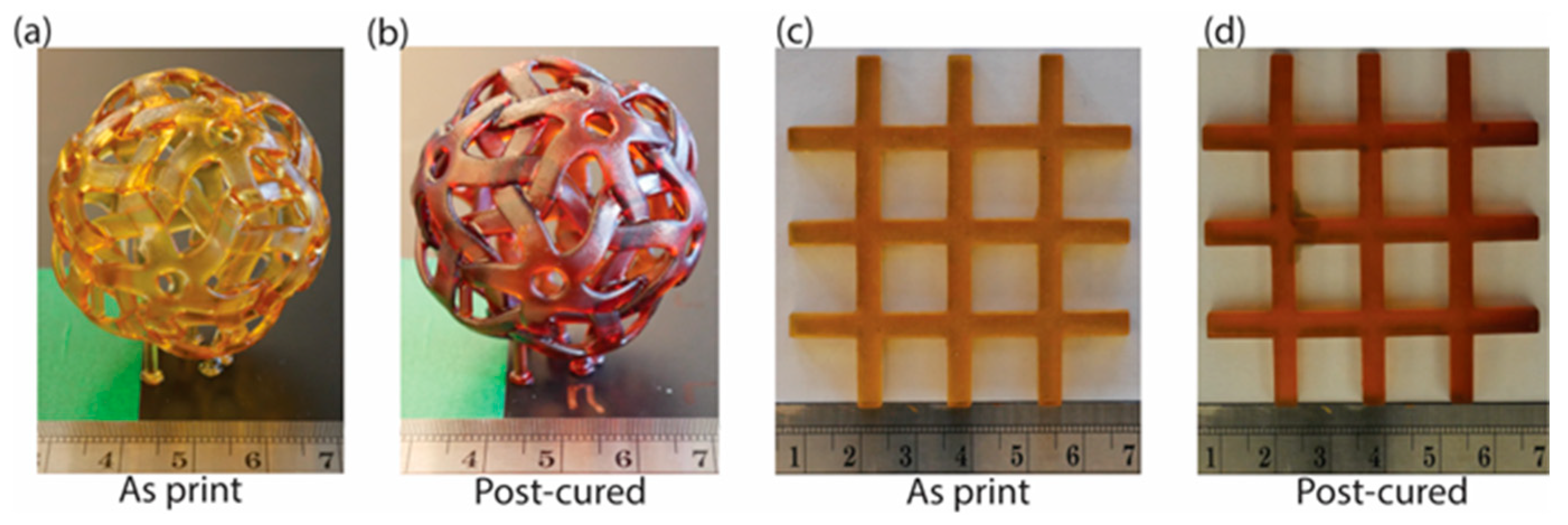

3.6. Printed Part Fidelity

3.7. Control of Print Conversion

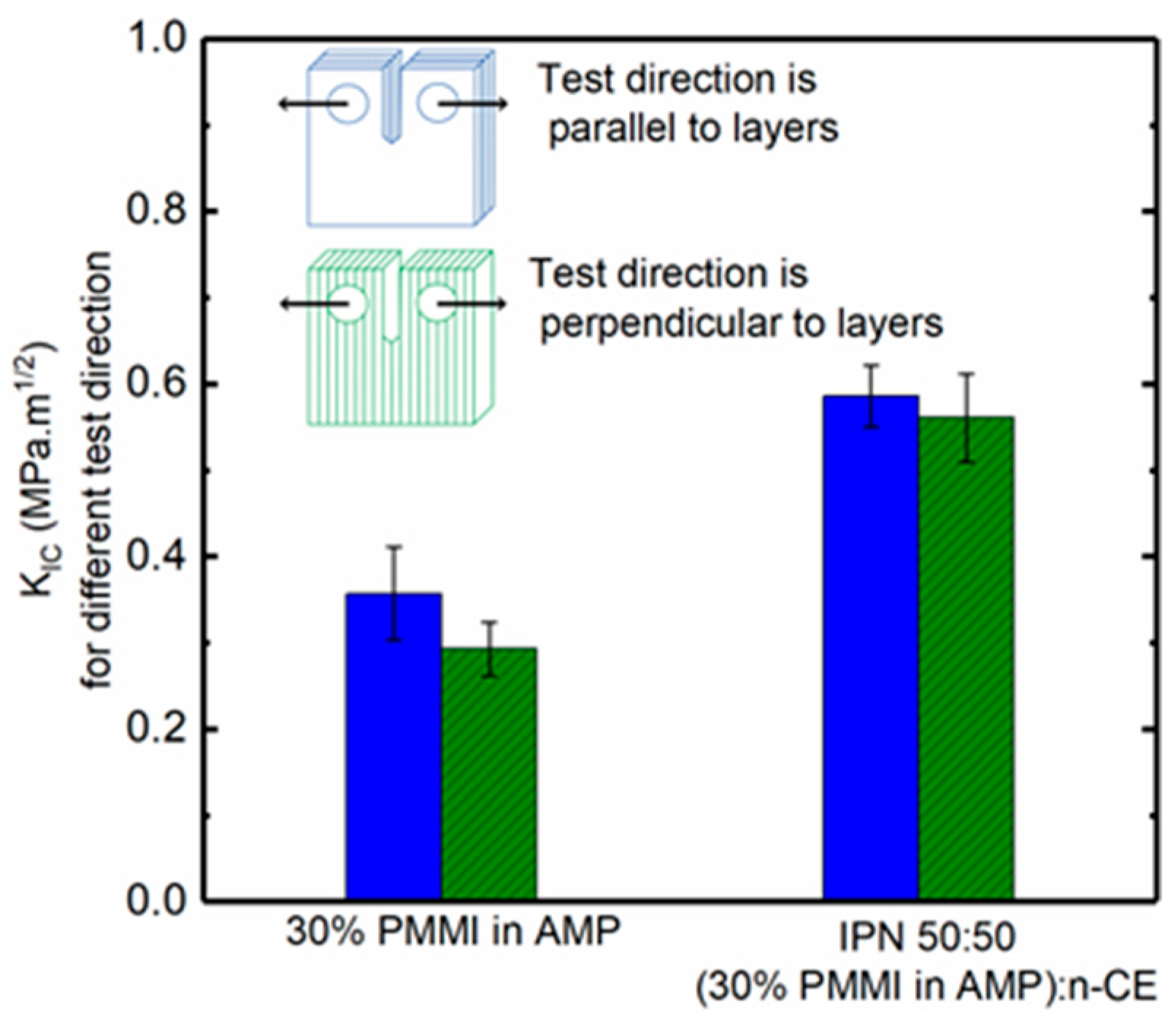

3.8. Bonding Between Layers

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Guo, N.; Leu, M.C. Additive manufacturing: Technology, applications and research needs. Front. Mech. Eng. 2013, 8, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligon, S.C.; Liska, R.; Stampfl, J.; Gurr, M.; Mülhaupt, R. Polymers for 3D printing and customized additive manufacturing. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10212–10290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Duoss, E.B.; Worsley, M.A.; Lewicki, J.P. 3D printing of high performance cyanate ester thermoset polymers. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, X.; Guo, Y.; Ji, Z.; Jia, X.; Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Liu, W. Additively manufacturing high-performance bismaleimide architectures with ultraviolet-assisted direct ink writing. Mater. Des. 2019, 180, 107947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.; Meenakshisundaram, V.; Chartrain, N.; Sekhar, S.; Tafti, D.; Williams, C.B.; Long, T.E. 3D printing all-aromatic polyimides using mask-projection stereolithography: Processing the nonprocessable. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1701240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Li, L.; Yan, B.; Bao, J.; Zhang, A. Acrylate-based photosensitive resin for stereolithographic three-dimensional printing. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, K.; Fang, D.; Kang, G.; Qi, H.J. High-Speed 3D Printing of High-Performance Thermosetting Polymers via Two-Stage Curing. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39, 1700809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karalekas, D.; Rapti, D.; Gdoutos, E.; Aggelopoulos, A. Investigation of shrinkage-induced stresses in stereolithography photo-curable resins. Exp. Mech. 2002, 42, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bychkov, P.S.; Chentsov, A.V.; Kozintsev, V.M.; Popov, A.L. Determination of residual stresses in objects at their additive manufacturing by layer-by-layer photopolymerization method. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 991, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, D.U.; Schubel, P.J. Evaluation of cure shrinkage measurement techniques for thermosetting resins. Polym. Test. 2010, 29, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmese, G.; Gillham, J. Time–temperature–transformation (TTT) cure diagrams: Relationship between Tg and the temperature and time of cure for a polyamic acid/polyimide system. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1987, 34, 1925–1939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, J.; Toll, S.; Månson, J.-A.E.; Hult, A. Residual stress build-up in thermoset films cured above their ultimate glass transition temperature. Polymer 1995, 36, 3135–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Noodeh, M.B.; Delpouve, N.; Saiter, J.-M.; Tan, L.; Negahban, M. Printing continuously graded interpenetrating polymer networks of acrylate/epoxy by manipulating cationic network formation during stereolithography. Express Polym. Lett. 2016, 10, 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitzmann, E.V.; Anderson, R.F.; Koljack, M.P.; Cruz, J.G.; Srivastava, C.M. High Temperature Performance Polymers for Stereolithography. U.S. Patent US6054250A, 25 April 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Iredale, R.J.; Ward, C.; Hamerton, I. Modern advances in bismaleimide resin technology: A 21st century perspective on the chemistry of addition polyimides. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 69, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamerton, I.; Hay, J.N. Recent developments in the chemistry of cyanate esters. Polym. Int. 1998, 47, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, C.P.R.; Mathew, D.; Ninan, K. Cyanate ester resins, recent developments. In New Polymerization Techniques and Synthetic Methodologies; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; pp. 1–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A. High performance bismaleimide/cyanate ester hybrid polymer networks with excellent dielectric properties. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2006, 66, 1749–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X. Bismaleimide and Cyanate Ester Based Sequential Interpenetrating Polymer Networks for High Temperature Application. Ph.D. Thesis, Drexel University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hamerton, I. High-performance thermoset-thermoset polymer blends: A review of the chemistry of cyanate ester-bismaleimide blends. High Perform. Polym. 1996, 8, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.L.; Boey, F.Y.C.; Abadie, M.J.M. UV curing of a liquid based bismaleimide-containing polymer system. Express Polym. Lett. 2007, 1, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D5045-99 (M1); Standard Test Methods for Plane-Strain Fracture Toughness and Strain Energy Release Rate of Plastic Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1999.

- ASTM D790-17; Standard Test Methods for Flexural Properties of Unreinforced and Reinforced Plastics and Electrical Insulating Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D1505-03; Standard Test Method for Density of Plastics by the Density-Gradient Technique. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2003.

- Marella, V.V.; Throckmorton, J.A.; Palmese, G.R. Hydrolytic degradation of highly crosslinked polyaromatic cyanate ester resins. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 104, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.; Akinc, M.; Kessler, M.R. Cure kinetics of thermosetting bisphenol E cyanate ester. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2008, 93, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligon-Auer, S.C.; Schwentenwein, M.; Gorsche, C.; Stampfl, J.; Liska, R. Toughening of photo-curable polymer networks: A review. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperling, L.H. Interpenetrating Polymer Networks: An Overview; ACS Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, M.S.; Liu, C.C.; Lee, C.T. Toughened interpenetrating polymer network materials based on unsaturated polyester and epoxy. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 72, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Resin | Dp (μm) | Ec (mW/cm2) |

|---|---|---|

| 20% PMMI in AMP | 223.3 | 11.5 |

| 30% PMMI in AMP | 152.6 | 13.7 |

| 40% PMMI in AMP | 93.8 | 16.7 |

| IPN 50:50 (30% PMMI in AMP):n-CE | 272.5 | 23.5 |

| IPN 60:40 (30% PMMI in AMP):n-CE | 249.8 | 20.7 |

| IPN 70:30 (30% PMMI in AMP):n-CE | 169.8 | 14.7 |

| Cure Stage | 20% PMMI in AMP | 30% PMMI in AMP | 40% PMMI in AMP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αAMP | As printed | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.41 |

| Post-cured | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| αPMMI | As printed | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.09 |

| Post-cured | 1 | 0.98 | 0.91 | |

| Tg (°C) | Post-cured | 200 | 225 | 252 |

| Tg (°C) | Estimated (Fox) | Used as reference | 230 | 263 |

| Cure Stage | IPN 70:30 (30% PMMI in AMP):n-CE | IPN 60:40 (30% PMMI in AMP):n-CE | IPN 50:50 (30% PMMI in AMP):n-CE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| αAMP | As printed | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.63 |

| UV post-cure | 0.91 | 0.96 | ~1 | |

| Thermal post-cure | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| αPMMI | As printed | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| UV post-cure | 0.4 | 0.41 | 0.42 | |

| Thermal post-cure | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.89 | |

| αn-CE | As printed | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| UV post-cure | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Thermal post-cure | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Tg (°C) | Thermal post-cure | 216 | 212 | 245 |

| Second DMA (E”) | 259 | 260 | 266 | |

| Tan delta | 287 | 294 | 300 | |

| Estimated (Fox) | 251 | 260 | 270 |

| Cure Stage | 30% PMMI in AMP | IPN 70:30 (30% PMMI in AMP) :n-CE | IPN 60:40 (30% PMMI in AMP) :n-CE | IPN 50:50 (30% PMMI in AMP) :n-CE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ (g/cm3) | Resin | 1.1748 | 1.2018 | 1.2073 | 1.2151 |

| As printed | 1.2757 | 1.2616 | 1.2601 | 1.2757 | |

| UV post-cured | 1.2785 | 1.2781 | 1.2817 | 1.2829 | |

| Thermal post-cured | 1.2817 | 1.2841 | 1.2838 | 1.2853 | |

| % change in density | As printed vs. resin | 8.58 | 4.95 | 4.37 | 4.98 |

| UV post-cured vs. resin | 8.82 | 6.34 | 6.16 | 5.58 | |

| Thermal post-cured vs. resin | 9.1 | 6.84 | 6.34 | 5.77 |

| 30% PMMI in AMP | IPN 50:50 (30% PMMI in AMP):n-CE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layers Perpendicular to Test Direction | Layers Parallel to Test Direction | Layers Perpendicular to Test Direction | Layers Parallel to Test Direction | |

| GIc (J/m2) | 45.8 ± 13.9 | 30.0 ± 6.4 | 106.0 ± 13.7 | 99.0 ± 18.0 |

| KIc (MPa.m1/2) | 0.357 ± 0.054 | 0.293 ± 0.031 | 0.586 ± 0.036 | 0.561 ± 0.051 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fridman, A.; Alvarez, N.J.; Palmese, G.R. High-Tg Vat Photopolymerization Materials Based on In Situ Sequential Interpenetrating Polymer Networks of Maleimide and Cyanate Ester Monomers. Polymers 2025, 17, 3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233179

Fridman A, Alvarez NJ, Palmese GR. High-Tg Vat Photopolymerization Materials Based on In Situ Sequential Interpenetrating Polymer Networks of Maleimide and Cyanate Ester Monomers. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233179

Chicago/Turabian StyleFridman, Anh, Nicolas J. Alvarez, and Giuseppe R. Palmese. 2025. "High-Tg Vat Photopolymerization Materials Based on In Situ Sequential Interpenetrating Polymer Networks of Maleimide and Cyanate Ester Monomers" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233179

APA StyleFridman, A., Alvarez, N. J., & Palmese, G. R. (2025). High-Tg Vat Photopolymerization Materials Based on In Situ Sequential Interpenetrating Polymer Networks of Maleimide and Cyanate Ester Monomers. Polymers, 17(23), 3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233179