Polyester Sheet Plastination: Technical Foundations, Methodological Advances, Anatomical Applications, and AQUA-Based Quality Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

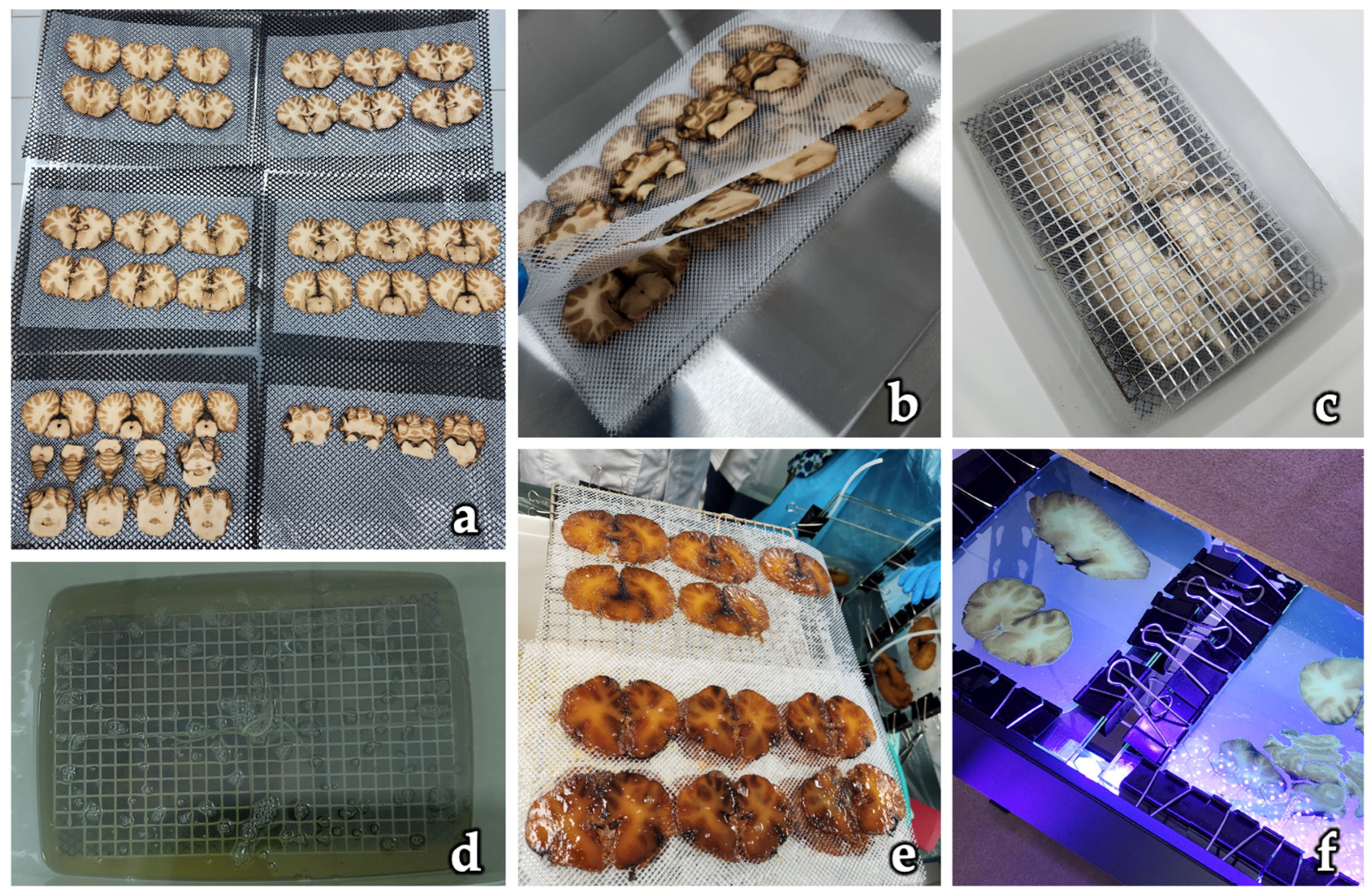

2. Materials and Methods

- Search Strategy and Eligibility Criteria

- Inclusion criteria were as follows:

- Original research articles published in peer-reviewed journals.

- Studies explicitly addressing polyester-based sheet plastination techniques, including P35 (Biodur Products GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany), P40, or P45 (Dalian Hoffen Biotechnic Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) methods.

- Articles reporting technical innovations, procedural protocols, educational applications, or research use of plastinated specimens.

- Studies conducted on human or animal anatomical specimens.

- Exclusion criteria included:

- Articles focused exclusively on silicone or epoxy plastination techniques.

- Narrative reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, or conference abstracts without full methodological description.

- Duplicated publications or studies lacking sufficient technical or anatomical detail.

- Studies unrelated to anatomical science or without practical application in education, research, or preservation.

- AQUA Quality Assessment and Reviewer Agreement

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Historical Background of Polyester Plastination

4.2. Technical Robustness and Standardization

4.3. Tissue Shrinkage in Polyester Plastination

4.4. Educational and Research Utility

| Anatomical Region | Purpose of Study | Key Findings/Advantages | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human brain (curriculum specimens) | Use of plastinated brain slices in anatomical education | Implementation of 4 mm P35 brain sections for neuroanatomy teaching to medical and allied health students; offered excellent gray–white matter contrast, cleanliness, odorless handling, durability, and direct correspondence with CT imaging courses | Weiglein (1993) [18] |

| Brain (coronal and Horizontal slices) | Neuroanatomical visualization | Produced thin (4–8 mm) odorless, high-contrast slices between gray and white matter; suitable for teaching without handling constraints | Barnett (1997) [24] |

| Human Brain (sagittal slices) | To determine the effect of different immersion and impregnation temperatures on shrinkage rates in brain plastination | Sagittal 4 mm slices processed at −25 °C (immersion and impregnation) showed lower shrinkage (4.41%) compared to slices processed at +5 °C/+15 °C (6.96%); supports low-temperature processing to enhance morphometric fidelity | Sora et al. (1999) [26,28] |

| Human Brain (methanol) | Evaluation of methanol as alternative dehydration solvent | Successfully plastinated 4 mm coronal brain slices using methanol (−20 to −25 °C) instead of acetone; no processing issues noted; methanol dehydration did not impair final P40 plastinate quality | Sora & Brugger (2000) [26] |

| Brain (Coronal slices) | Neuroanatomical visualization and educational use | Achieved clear, detailed coronal sections of the brain with preserved structural relationships using P35; suitable for teaching without odor or toxicity | Barnett et al. (2005) [17] |

| Brain (Coronal slices) | Neuroanatomical visualization for teaching | Preserved structural relationships; high-quality teaching material with minimal shrinkage | Guerrero et al. (2019) [23] |

| Human Brain (3 mm slices) | To statistically analyse tissue shrinkage during sheet plastination with polyester resin (Biodur® P40) | Reported shrinkage between 2.14 and 6.22% after dehydration and 7.02–10.62% after forced impregnation; confirmed that most shrinkage occurs during impregnation; highlighted need for low-temperature dehydration to reduce distortion | Ottone et al. (2020) [9] |

| Knee Joint | To explore fibular support to the tibial plateau (Proximal tibiofibular region) | Found dense trabecular connections forming an arch-like structure that may influence knee load distribution and KOA | Jiang et al. (2021) [34] |

| To analyze bony features at cruciate ligament attachment sites | Identified dense ridges and trabecular structures supporting ligament anchorage and guiding reconstruction | Jiang et al. (2022) [35] | |

| To clarify the anterior insertions of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) | Demonstrated that the MPFL does not attach directly to the patella but integrates with the vastus medialis obliquus, vastus intermedius, and parapatellar tendons; findings refine surgical reconstruction strategies | Cheng et al. (2025) [37] | |

| Proximal Tibia (Knee joint) | Trabecular architecture mapping | Identified trabecular patterns: thick longitudinal trabeculae in condyles, network in intercondylar region, arcuate trusses in metaphysis; reinforced bone near ligament attachments | Sun et al. (2021) [36] |

| Proximal femur | To investigate trabecular morphology and biomechanics via plastination and finite element analysis | Identified medial and lateral trabecular systems; vertical struts absorb compression, horizontal struts resist tension; Ward’s triangle defined as structurally weak region with clinical relevance for implant design | Shah et al. (2025) [38] |

| To qualitatively analyse the three-dimensional arrangement of trabeculae in coronal, sagittal, and horizontal planes | Described a “mushroom-like” primary compressive strut and two independent trabecular subsystems (head–neck and neck–shaft), separated by a redefined quadrangular Ward’s triangle; insights inform fixation, implant design, and surgical robotics | Zhang et al. (2025) [43] | |

| Craniovertebral junction/Miodural bridge | Definition of TBNL and VDL | Proposed link to CSF circulation; clarified dural attachments | Zheng et al. (2014) [51] |

| To assess MDB presence across mammalian species | Found MDB in all 15 species, suggesting it is a conserved and essential structure | Zheng et al. (2017) [46] | |

| To classify the attachment patterns of the myodural bridge from the RCPmi muscle | Identified four insertion patterns of the myodural bridge; supports its role in CSF dynamics and cervicogenic headache pathophysiology | Yuan et al. (2016) [48] | |

| To define the MDBC as a functional anatomical unit | Identified MDBC components (RCPmi, RCPma, OCI); proposed roles in CSF flow, dural tension, and venous return | Zheng et al. (2020) [54] | |

| To examine effects of congenital C0–C1 fusion on the MDB | Found that MDB persists via nuchal ligament fibers despite absence of key muscles, indicating compensatory support | Chi et al. (2022) [49] | |

| To analyze the fiber composition of the cervical spinal dura mater | The SDM is a three-layered structure formed by fibers from the cerebral dura, occipital periosteum, and myodural bridge; findings support dural preservation in CVJ surgery | Zhuang et al. (2022) [55] | |

| To study LCT structure via P45 and confocal microscopy | Revealed layered collagen architecture and tissue connections; useful for lateral canthoplasty | Li et al. (2023) [22] | |

| To analyze the detailed morphology of the suboccipital cavernous sinus (SCS) and its anatomical relationship with the myodural bridge complex (MDBC) | Identified fibrous MDBC connections to the SCS; suggests role in venous drainage and intracranial pressure regulation. | Zhang et al. (2023) [56] | |

| Orbit/Eyelid | To study fat tissue distribution (upper eyelid, Asian) | Clarified preseptal and preaponeurotic fat layers; high-resolution sections for surgical relevance | Chun et al. (2015) [41] |

| To analyze ROOF continuity using histology and P45 (periorbital region) | Found ROOF is a continuous fat layer from brow to cheek; relevant for surgery and filler safety | Ma et al. (2020) [40] | |

| To examine canthal ligaments (periorbital region) | Revealed structure and insertions of canthal ligaments; useful for eyelid surgical planning | Qin et al. (2021) [39] | |

| Nasolabial region | To study the relationship between nasolabial fold and superficial fascia | Found nasolabial fold aligns with medial edge of SFS; supports surgical approaches for facial rejuvenation | Hwang et al. (2021) [44] |

| Midcheek region | To analyze anatomical basis of midcheek groove and evaluate treatment | Identified fibroelastic bundles beneath OOM linked to groove; deep filling improved clinical outcomes | Du et al. (2021) [45] |

| Infratemporal and pterygopalatine fossae (masticatory muscles) | To characterise the debated sphenomandibularis (SM) using plastination and dissection | Confirmed distinct morphology from temporalis; close relation to maxillary nerve, buccal nerve, and maxillary artery; supports recognition of SM as independent muscle with educational and clinical relevance (neuralgia, nerve block, mandibular biomechanics) | Zhang et al. (2025) [53] |

| Perineum | Spatial organization of ischioanal fossa | Improved interpretation for imaging and surgery | Zhang et al. (2017) [42] |

| Penis | Definition of corpora-glans ligament | Clarified anatomical anchoring relevant to reconstruction | Jiang et al. (2023) [52] |

| Hip Joint | Morphometric validation for orthopedic planning | Agreement with 3D metrics; minimal shrinkage | Genser-Strobl & Sora (2005) [33] |

| Comparative anatomy (mammals, reptiles) | MDB structure across species | Demonstrated universal presence and functional conservation | Zhang et al. (2016) [50] |

| Sperm whale | Aquatic adaptations of MDB | Suggested CSF regulation during diving | Liu et al. (2018) [57] |

| Neophocaena | Characterize the myodural bridge as independent muscle | Identification of an independent muscle (“occipital-dural muscle”) potentially involved in cerebrospinal fluid circulation | Zhang et al. (2021) [47] |

| Equine Tarsus (Horse ankle) | Aid in interpreting MR images via plastinated slices | P-40 semitransparent and S10 thick slices (2–10 mm) provided detailed anatomical correlation with sagittal and transverse MR images, improving visualization of joints, tendons, synovial pouches and muscle–tendon relationships | Latorre et al. (2003) [7] |

| Suboccipital region (marine mammal) | To verify the existence and structure of the myodural bridge (MDB) in Neophocaena phocaenoides | The MDB exists in this species; RCDmi inserts into the cervical spinal dura via a tendinous bridge through the posterior atlanto-occipital interspace. No dorsal atlanto-occipital membrane was observed. P45 plastination and histology confirmed the structure, composed of type I collagen | Liu et al. (2017) [58] |

| Multiple tissues (brain, viscera, bone, muscle) | To present polyester sheet plastination as a versatile method applicable to different tissue types. | Technique produced durable, odorless, and transparent plastinated sheets across multiple organs and systems; emphasized its adaptability and suitability for both teaching and research, expanding applications beyond neuroanatomy. | Latorre et al. (2004) [59] |

4.5. AQUA-Based Analysis of Anatomical Studies

4.6. Limitations and Areas for Improvement

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- von Hagens, G. Impregnation of Soft Biological Specimens with Thermosetting Resins and Elastomers. Anat. Rec. 1979, 194, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hagens, G. Heidelberg Plastination Folder: Collection of Technical Leaflets for Plastination; Biodur Products: Heidelberg, Germany, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- von Hagens, G.; Tiedemann, K.; Kriz, W. The Current Potential of Plastination. Anat. Embryol. 1987, 175, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottone, N.E. Advances in Plastination Techniques; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.W.; Latorre, R. Polyester Plastination of Biological Tissue: P40 Technique for Brain Slices. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2007, 22, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.; Weiglein, A.; Latorre, R.; Henry, R.W. Polyester Plastination of Biological Tissue: P35 Technique. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2007, 22, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, R.; Arencibia, A.; Gil, F.; Rivero, M.; Ramírez, G.; Vásquez-Autón, J.M.; Henry, R.W. P-40 and S10 Plastinated Slices: An Aid to Interpreting MR Images of the Equine Tarsus. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2003, 18, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baptista, C.A.C.; DeJong, K.; Latorre, R.; Bittencourt, A.S. P40 Polyester Sheet Plastination Technique for Brain and Body Slices: The Vertical and Horizontal Flat Chamber Methods. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2019, 48, 572–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottone, N.E.; Guerrero, M.; Alarcón, E.; Navarro, P. Statistical Analysis of Shrinkage Levels of Human Brain Slices Preserved by Sheet Plastination Technique with Polyester Resin. Int. J. Morphol. 2020, 38, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sora, M.C.; Latorre, R.; Baptista, C.; López-Albors, O. Plastination—A Scientific Method for Teaching and Research. Anat. Histol. Embryol. 2019, 48, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H.; Lm, J.; Yu, S.; Sui, H. A New Polyester Technique for Sheet Plastination. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2006, 21, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, B.M.; Tomaszewski, K.A.; Ramakrishnan, P.K.; Roy, J.; Vikse, J.; Loukas, M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Walocha, J.A. Development of the Anatomical Quality Assessment (AQUA) Tool for the Quality Assessment of Anatomical Studies Included in Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews. Clin. Anat. 2017, 30, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewski, K.A.; Henry, B.M.; Ramakrishnan, P.K.; Roy, J.; Vikse, J.; Loukas, M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Walocha, J.A. Development of the Anatomical Quality Assurance (AQUA) Checklist: Guidelines for Reporting Original Anatomical Studies. Clin. Anat. 2017, 30, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadood, A.A.; Jabbar, A.; Das, N. Plastination of Whole Brain Specimen and Brain Slices. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2001, 13, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Weber, W.; Henry, R.W. Sheet Plastination of the Brain—P35 Technique, Filling Method. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 1992, 6, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiglein, A.H. Preparing and Using S-10 and P-35 Brain Slices. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 1996, 10, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.; Burland, G.; Duxson, M. Plastination of Coronal Slices of Brains from Cadavers Using the P35 Technique. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2005, 20, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiglein, A.H. Plastinated Brain-Specimens in the Anatomical Curriculum at Graz University. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 1993, 7, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, H.J.; Henry, R.W. Hoffen P45: A Modified Polyester Plastination Technique for Both Brain and Body Slices. J. Plast. 2015, 27, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzuela, O.M.; Azócar, S.C.; Werner, F.K.; Vega, P.E.; Valdés, G.F. Experiencia en Plastinación con Resina Poliéster P-4 para Cortes Anatómicos. Int. J. Morphol. 2012, 30, 810–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvenato, L.S.; Monteiro, Y.F.; Miranda, R.P.; Bittencourt, A.P.S.V.; Bittencourt, A.S. Is Domestic Polyester Suitable for Plastination of Thin Brain Slices? Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2023, 56, e12566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F.; Wei, R.X.; Yang, K.Q.; Hack, G.D.; Chi, Y.Y.; Tang, W.; Sui, X.J.; Zhang, M.L.; Sui, H.J.; Yu, S.B. A Valuable Subarachnoid Space Named the Occipito-Atlantal Cistern. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 12096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Vargas, C.; Alarcón, E.; Del Sol, M.; Ottone, N.E. Development of a Sheet Plastination Protocol with Polyester Resin Applied to Human Brain Slices. Int. J. Morphol. 2019, 37, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, R.J. Plastination of Coronal and Horizontal Brain Slices Using the P40 Technique. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 1997, 12, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üzel, M.; Weiglein, A.H. P35 Plastination: Experiences with Delayed Impregnation. J. Plast. 2013, 25, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sora, M.C.; Brugger, P. P40 Brain Slices Plastination Using Methanol for Dehydration. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2000, 15, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.B.; Helms, L.; Rowe, J.A. Curing Times of P40 Exposed to Different Light Sources. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2008, 28, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sora, M.C.; Brugger, P.; Traxler, H. P40 Plastination of Human Brain Slices: Comparison between Different Immersion and Impregnation Conditions. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 1999, 14, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.S.; Sui, H.J. Updated Protocol for the Hoffen P45 Sheet Plastination Technique. J. Plast. 2019, 31, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.S.; Dou, Y.R.; Sui, H.J. Tissue Shrinkage after P45 Plastination. J. Plast. 2019, 31, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiglein, A.H. Plastination in the Neurosciences. Keynote Lecture. Acta Anat. 1997, 158, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, R.; Henry, R.W. Polyester Plastination of Biological Tissue: P40 Technique for Body Slices. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2007, 22, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genser-Strobl, B.; Sora, M.C. Potential of P40 Plastination for Morphometric Hip Measurements. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2005, 27, 147–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.B.; Sun, S.Z.; Li, C.; Adds, P.; Tang, W.; Chen, W.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J. Anatomical Basis of the Support of Fibula to Tibial Plateau and Its Clinical Significance. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.B.; Song, T.W.; Sun, S.Z.; Li, C.; Adds, P.; Xu, Q.; Liu, C.; Tang, W.; Chi, Y.Y.; Chen, W.; et al. Bony Structures at the Attachment Areas of the Cruciate Ligaments in Human Knee Joints and Their Clinical Significance, Studied Using the P45 Plastination Technique. Int. J. Morphol. 2022, 40, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.Z.; Jiang, W.B.; Song, T.W.; Chi, Y.Y.; Xu, Q.; Liu, C.; Tang, W.; Xu, F.; Zhou, J.X.; Yu, S.B.; et al. Architecture of the Cancellous Bone in Human Proximal Tibia Based on P45 Sectional Plastinated Specimens. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2021, 43, 2055–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.; Alam Shah, M.A.; Wang, J.W.; Jiang, W.B.; Zhang, X.H.; Sui, H.J.; Zheng, N.; Yu, S.B. Anterior Attachments of the Medial Patellofemoral Ligament: Morphological Characteristics. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2025, 107, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.A.A.; Lü, S.J.; Zhang, J.F.; Wang, J.W.; Tang, W.; Luo, W.C.; Lai, H.X.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J. Functional Morphology of Trabecular System in Human Proximal Femur: A Perspective from P45 Sectional Plastination and 3D Reconstruction Finite Element Analysis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Chun, P.; Li, F.F.; Yu, S.B.; Hwang, K.; Sui, H.J. Medial and Lateral Canthal Ligaments Shown in P45 Sheet Plastination and Dissection. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 69, 1150–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.D.; Chun, P.; Zhang, C.; Li, F.F.; Qin, T.; Qin, H.Z.; Sui, H.J. Investigation of Retro-Orbicularis Oculi Fat and Associated Orbital Septum Connective Tissues in Upper Eyelid Surgery. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 3899–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, P.; Yu, S.; Qin, H.; Sui, H. The Use of P45 Plastination Technique to Study the Distribution of Preseptal and Preaponeurotic Fat Tissues in Asian Eyelids. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2015, 73, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.F.; Du, M.L.; Sui, H.J.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, H.Y.; Meng, C.; Qu, M.J.; Zhang, Q.; Du, B.; Fu, Y.S. Investigation of the Ischioanal Fossa: Application to Abscess Spread. Clin. Anat. 2017, 30, 1029–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.F.; Lü, S.J.; Wang, J.W.; Tang, W.; Li, C.; Campbell, G.; Sui, H.J.; Yu, S.B.; Zhao, D.W. The Qualitative Analysis of Trabecular Architecture of the Proximal Femur Based on the P45 Sectional Plastination Technique. J. Anat. 2025, 246, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, K.; Sui, H.J.; Han, S.H.; Kim, H. The Nasolabial Area Shown on Histology and P45 Sheet Plastination. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2021, 32, 771–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Sui, H.; Luo, S. Anatomic Characteristics and Treatment of the Midcheek Groove by Deep Filling. Dermatol. Surg. 2021, 47, e47–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Yuan, X.Y.; Chi, Y.Y.; Liu, P.; Wang, B.; Sui, J.Y.; Han, S.H.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J. The Universal Existence of Myodural Bridge in Mammals: An Indication of a Necessary Function. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 8248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.X.; Gong, J.; Yu, S.B.; Li, C.; Sun, J.X.; Ding, S.W.; Ma, G.J.; Sun, S.Z.; Zhou, L.; Hack, G.D.; et al. A Specialized Myodural Bridge Named Occipital-Dural Muscle in the Narrow-Ridged Finless Porpoise (Neophocaena asiaeorientalis). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.Y.; Yu, S.B.; Li, Y.F.; Chi, Y.Y.; Zheng, N.; Gao, H.B.; Luan, B.Y.; Zhang, Z.X.; Sui, H.J. Patterns of Attachment of the Myodural Bridge by the Rectus Capitis Posterior Minor Muscle. Anat. Sci. Int. 2016, 91, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Y.Y.; Zhuang, J.; Jin, G.; Hack, G.D.; Song, T.W.; Sun, S.Z.; Chen, C.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J. Congenital Atlanto-Occipital Fusion and Its Effect on the Myodural Bridge: A Case Report Utilizing the P45 Plastination Technique. Int. J. Morphol. 2022, 40, 796–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Tang, W.; Zhang, Z.X.; Luan, B.Y.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J. Connection of the Posterior Occipital Muscle and Dura Mater of the Siamese Crocodile. Anat. Rec. 2016, 299, 1402–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, N.; Yuan, X.Y.; Li, Y.F.; Chi, Y.Y.; Gao, H.B.; Zhao, X.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J.; Sharkey, J. Definition of the To Be Named Ligament and Vertebrodural Ligament and Their Possible Effects on the Circulation of CSF. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e103451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.B.; Li, C.; Gilmore, C.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J. Detailed Anatomy of the Corpora-Glans Ligament via the P45 Plastination Method. Int. J. Morphol. 2023, 41, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Li, F.F.; Ma, X.D.; Qi, W.Y.; Liu, Y.Z.; Sui, H.J.; Chun, P. The Sphenomandibularis Shown on P45 Sheet Plastination and Dissection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.; Chung, B.S.; Li, Y.L.; Liu, T.Y.; Zhang, L.X.; Ge, Y.Y.; Wang, N.X.; Zhang, Z.H.; Cai, L.; Chi, Y.Y.; et al. The Myodural Bridge Complex Defined as a New Functional Structure. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2020, 42, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, J.; Gong, J.; Hack, G.D.; Chi, Y.Y.; Song, Y.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J. A New Concept of the Fiber Composition of Cervical Spinal Dura Mater: An Investigation Utilizing the P45 Sheet Plastination Technique. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2022, 44, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.H.; Gong, J.; Song, Y.; Hack, G.D.; Jiang, S.M.; Yu, S.B.; Song, X.; Zhang, J.; Yang, H.; Cheng, J.; et al. An Anatomical Study of the Suboccipital Cavernous Sinus and Its Relationship with the Myodural Bridge Complex. Clin. Anat. 2023, 36, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, C.; Zheng, N.; Yuan, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chun, P.; Chi, Y.; Gilmore, C.; Yu, S.; Sui, H. The Myodural Bridges’ Existence in the Sperm Whale. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0200260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Li, C.; Zheng, N.; Xu, Q.; Yu, S.B.; Sui, H.J. The Myodural Bridge Existing in the Neophocaena phocaenoides. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latorre, R.; Arencibia, A.; Gil, F.; Rivero, M.; Ramírez, G.; Vásquez-Autón, J.M.; Henry, R.W. Sheet Plastination with Polyester: An Alternative for All Tissues. J. Int. Soc. Plast. 2004, 19, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwanaga, J.; Singh, V.; Ohtsuka, A.; Hwang, Y.; Kim, H.J.; Moryś, J.; Ravi, K.S.; Ribatti, D.; Trainor, P.A.; Sañudo, J.R.; et al. Acknowledging the Use of Human Cadaveric Tissues in Research Papers: Recommendations from Anatomical Journal Editors. Clin. Anat. 2021, 34, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwanaga, J.; Kim, H.J.; Akita, K.; Logan, B.M.; Hutchings, R.T.; Ottone, N.; Nonaka, Y.; Anand, M.; Burns, D.; Singh, V.; et al. Ethical Use of Cadaveric Images in Anatomical Textbooks, Atlases, and Journals: A Consensus Response from Authors and Editors. Clin. Anat. 2025, 38, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Description | Reagents | Equipment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Fixation (optional) | Tissue is fixed in 4% formaldehyde or buffered formalin solution to preserve morphology. | 4% buffered formaldehyde | Fixation tanks, PPE (gloves, masks, lab coat) |

| 2. Slicing | Specimens are frozen and sectioned into slices (2–4 mm) using a band saw or slicing device. | None | Band saw with liquid nitrogen or freezing unit, cryoprotection chamber |

| 3. Freeze Substitution Dehydration | Slices are placed in cold 100% acetone at −25 °C to dehydrate tissues while maintaining structure (15 to 20 days) | 100% acetone | Deep freezer (−25 °C), acetonometer, dehydration containers |

| 4. Pre-Impregnation Setup | Slices are positioned between polyethylene or foam boards to maintain orientation and prevent folding (24 h) | None | Polyethylene foam boards, pins or clamps |

| 5. Vacuum Impregnation with P40 | Dehydrated slices are submerged in P40 resin under vacuum to replace acetone with polymer (24 h) | P40 polyester resin | Vacuum chamber, vacuum pump, pressure gauge, resin container |

| 6. Curing (Polymerization) | Impregnated slices are placed between glass or acrylic plates and cured with UV light. | UV-sensitive P40 resin (no hardener required) | UV light source (e.g., 315–400 nm), glass or acrylic sandwich chambers, clamps or spring systems |

| 7. Trimming and Cleaning | Cured slices are removed from the chamber, excess resin trimmed, and surfaces cleaned. | Isopropanol or ethanol for cleaning | Scalpel or blade, soft cloths, trimming tools |

| 8. Labeling and Storage | Finished plastinates are labeled and stored in protective cases at room temperature. | None | Archival containers, labeling system |

| Aspect | P35 | P40 | P45 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resin used | Polyester P35 (Biodur®) | Polyester P40 (Biodur®) | Polyester P45 (Hoffen®) |

| Typical slice thickness | 4–8 mm | 2–4 mm | 2–3 mm (brain), large body sections |

| Curing process | UV + heat, dual curing | Simplified UV curing | Water bath at 40 °C |

| Main advantages | Excellent gray/white matter contrast in brain | High transparency, lower viscosity, more accessible, avoids UV using sunlight shadow | Avoids UV use, good clarity in large slices |

| Main disadvantages | Complex, bubble risk, requires thick safety glass | Sensitive to inadequate fixation | Less widespread, requires specific equipment |

| Common applications | Neuroanatomy, imaging correlation | Neuroanatomy, large body sections, medical and veterinary education | Large body sections, comparative research, veterinary anatomy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ottone, N.E.; Torres-Villar, C.; Gómez-Barril, R.; Baeza-Fernández, J.; Rodríguez-Torrez, V.H.; Veuthey, C. Polyester Sheet Plastination: Technical Foundations, Methodological Advances, Anatomical Applications, and AQUA-Based Quality Analysis. Polymers 2025, 17, 3177. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233177

Ottone NE, Torres-Villar C, Gómez-Barril R, Baeza-Fernández J, Rodríguez-Torrez VH, Veuthey C. Polyester Sheet Plastination: Technical Foundations, Methodological Advances, Anatomical Applications, and AQUA-Based Quality Analysis. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3177. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233177

Chicago/Turabian StyleOttone, Nicolás E., Carlos Torres-Villar, Ricardo Gómez-Barril, Josefa Baeza-Fernández, Víctor Hugo Rodríguez-Torrez, and Carlos Veuthey. 2025. "Polyester Sheet Plastination: Technical Foundations, Methodological Advances, Anatomical Applications, and AQUA-Based Quality Analysis" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3177. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233177

APA StyleOttone, N. E., Torres-Villar, C., Gómez-Barril, R., Baeza-Fernández, J., Rodríguez-Torrez, V. H., & Veuthey, C. (2025). Polyester Sheet Plastination: Technical Foundations, Methodological Advances, Anatomical Applications, and AQUA-Based Quality Analysis. Polymers, 17(23), 3177. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233177