Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion of Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. CLTE Measurement Methods

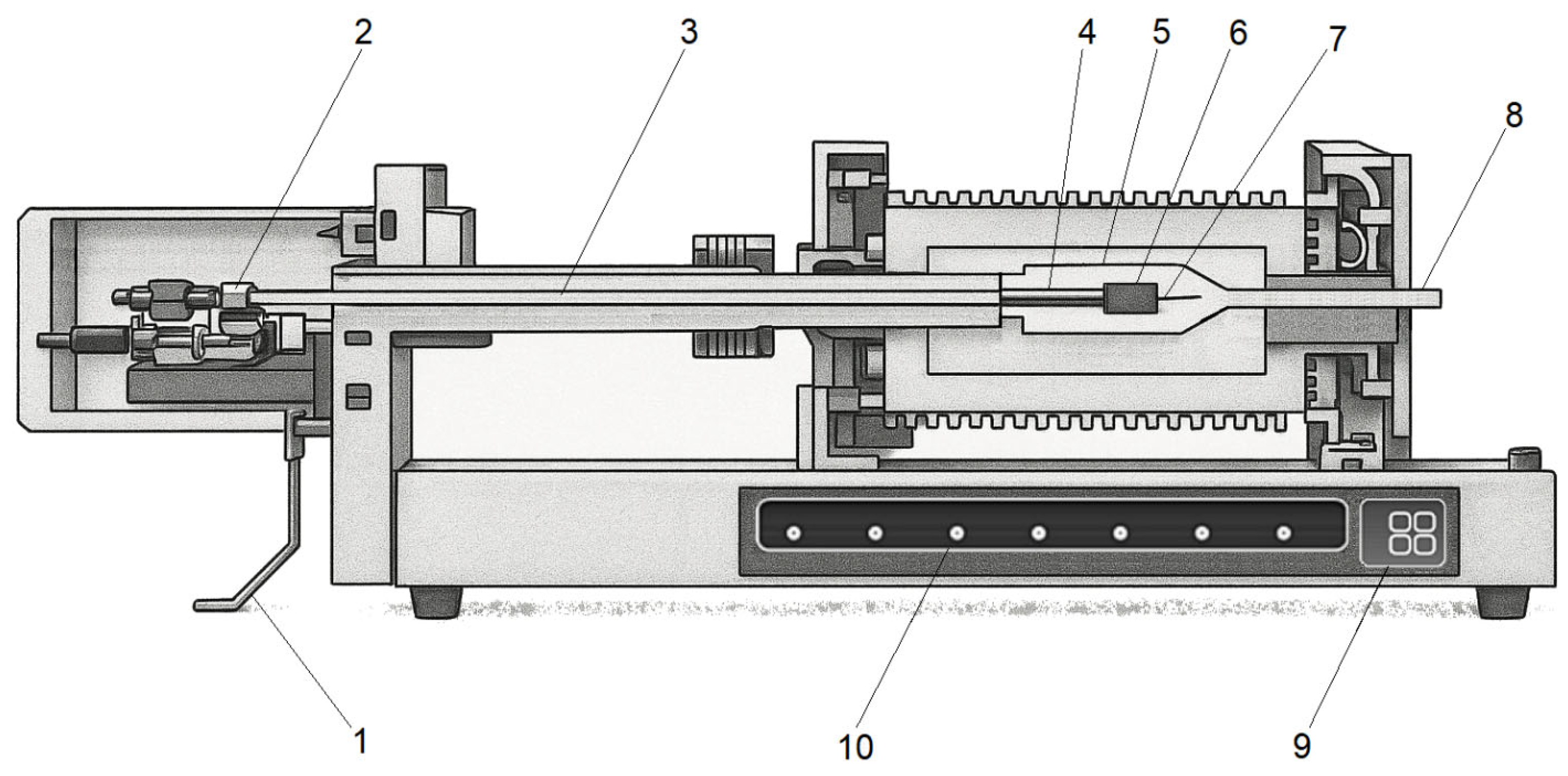

2.1. Contact Dilatometry

2.2. Thermomechanical Analysis

2.3. Optical Methods

2.3.1. Digital Image Correlation

2.3.2. Laser Interferometry

2.3.3. Laser Diffraction

2.4. Strain-Gauge Method

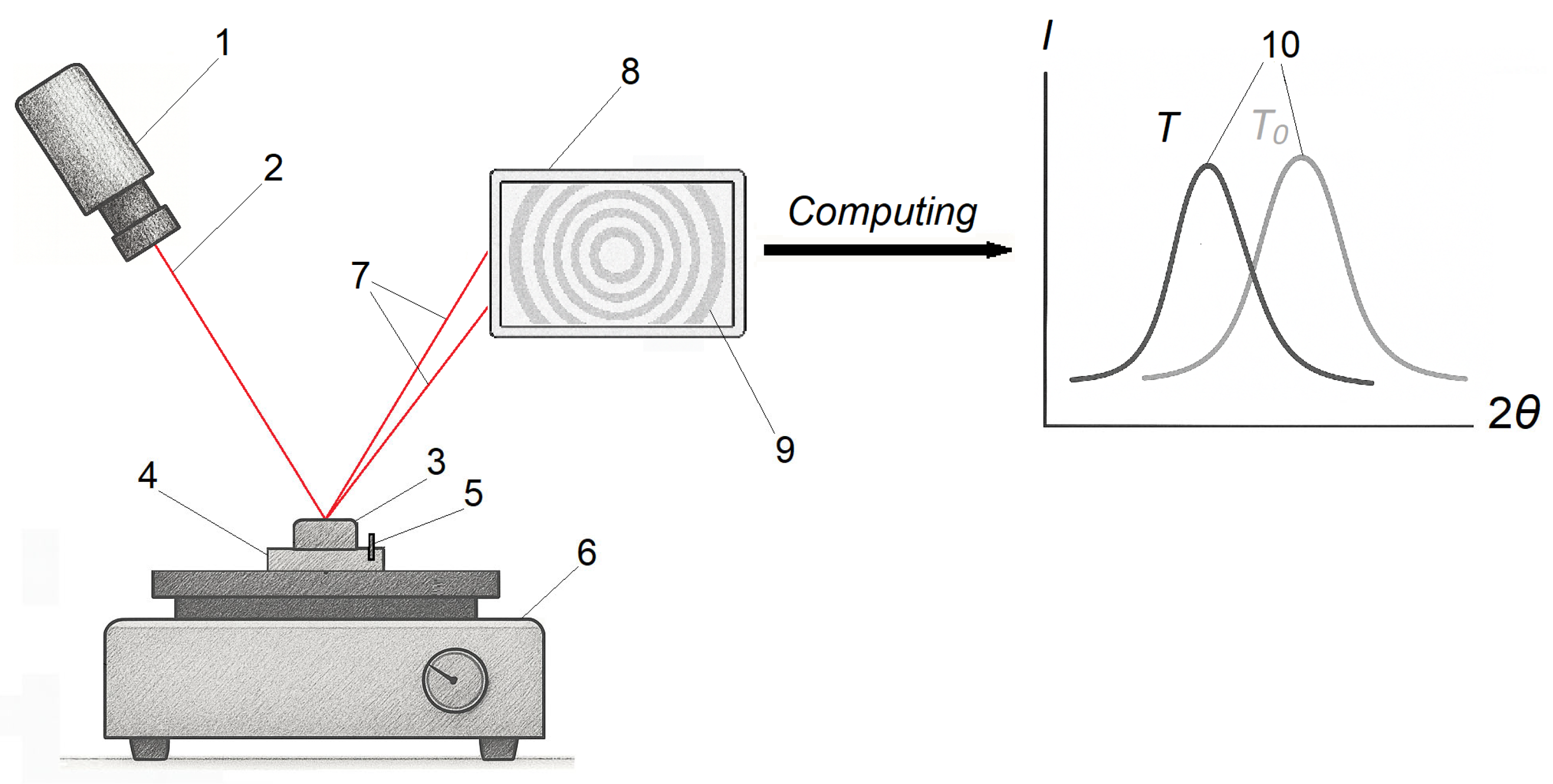

2.5. X-Ray Diffractometry

3. Mathematical Modeling Approaches for Predicting the CLTE of PCMs

- to identify the constituent materials (in particular, the filler and the matrix), which leads to an inverse coefficient problem in the mechanics of composite materials [62];

- to identify the reinforcement scheme (particulate, fibrous, etc.) and/or the geometry of the reinforcing elements and/or the filler content (volume or mass fraction), which leads to a global structural optimization problem.

4. CLTE of Polymer Materials

4.1. CLTE of Thermoplastics

4.1.1. Commodity Thermoplastics

4.1.2. Engineering Thermoplastics

4.1.3. High-Performance Thermoplastics

| Polymer Type | ΔT1, °C | αl, ppm/°C | ΔT2, °C | α2, ppm/°C | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High-density polyethylene (HDPE) | - | - | −30–60 | ~180 | [92] |

| Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) | - | - | 0–65 | ~300 | [93] |

| Polypropylene (PP) | - | - | −50–50 | ~110 | [94] |

| Polystyrene (PS) | 0–100 | ~60–100 | - | - | [95] |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) | 0–90 | ~150 | 110–150 | ~250–300 | [117] |

| 20–65 | ~100–150 | [118] | |||

| Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) | 20–90 | ~80 | - | - | [119] |

| Acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene (ABS) | 20–50 | ~90 | - | - | [120] |

| Poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET) | −40–50 | ~20–50 | 80–200 | ~650 | [97] |

| Polyamide 6 (nylon 6, PA6) | 0–30 | ~75 | 60–80 | ~130 | [98] |

| Polyamide 66 (nylon 66, PA66) | −20–50 | ~70–80 | 100–130 | ~110–120 | [99] |

| Poly(butylene terephthalate) (PBT) | −40–40 | ~80 | 70–160 | ~90 | [121] |

| Poly(phenylene oxide) (PPO) | 0–180 | ~25–75 | 230–260 | ~200 | [90] |

| Polyphthalamide (PPA) | 25–80 | ~80 | - | - | [122] |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | −40–95 | ~60–70 | - | - | [100] |

| Poly(phenylene sulfide) (PPS) | 20–70 | ~50 | - | - | [123] |

| Polysulfone (PSU) | 20–80 | ~55 | [124] | ||

| Polyethersulfone (PES) | 30–150 | ~70 | [125] | ||

| Polyphenylsulfone (PPSU) | 20–80 | ~55 | - | - | [126] |

| Poly(ether ketone) (PEK) | 50–120 | ~60 | - | - | [127] |

| Poly(ether ether ketone) (PEEK) | 25–120 | ~45–50 | 180–250 | ~100–120 | [102] |

| Poly(ether ketone ketone) (PEKK) | 20–80 | ~30 | - | - | [128] |

| Polyimides (PI) | 50–250 | ~0–50 | - | - | [107] |

| 50–200 | ~0–50 | [129] | |||

| Polyetherimide (PEI) | 0–150 | ~40–65 | - | - | [130] |

| Polyamide–imide (PAI) | 30–300 | ~−5–45 | - | - | [112] |

| Liquid-crystal polymers (LCPs) –along the macromolecular orientation | 20–200 | ~0–10 | - | - | [131] |

| Liquid-crystal polymers (LCPs) –transverse to the macromolecular orientation | 50–150 | ~30 | - | - | [116] |

4.2. CLTE of Thermosetting Polymers

4.2.1. Epoxy Resins

4.2.2. Polyester Resins

4.2.3. Phenol–Formaldehyde Resins

4.2.4. Bismaleimide (BMI) Resins

4.2.5. Silicone Resins

| Polymer Type | ΔT1, °C | α1, ppm/°C | ΔT2, °C | α2, ppm/°C | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy resins | 40–80 | 73 | 120–200 | 216 | [166] |

| 50–110 | 65 | 130–210 | 190 | [167] | |

| - | 71 | - | 165 | [168] | |

| 60–100 | 80 | 200–250 | 183 | [169] | |

| Polyester resins | 25–40 | ~120 | 70–100 | ~200 | [170] |

| 20–80 | ~100 | 100–120 | ~120 | [171] | |

| 20–50 | ~55 | 90–140 | ~180 | [149] | |

| 30–65 | ~80–110 | 90–125 | ~180–200 | [148] | |

| Phenol-formaldehyde resins | 20–90 | ~45–50 | - | - | [172] |

| - | ~65–75 | - | ~160–180 | [173] | |

| 0–100 | ~50–60 | - | - | [174] | |

| Bismaleimide resins | 20–80 | ~50 | - | - | [175] |

| −20–150 | ~70 | - | - | [159] | |

| Silicone resins | - | - | - | ~165–180 | [176] |

| - | - | 100 | ~125 | [177] | |

| 150 | ~250 | ||||

| 200 | ~425 | ||||

| 25–350 | 110 | [178] | |||

| 25–160 | ~15–30 | [165] | |||

| Polyimides (thermally cured) | 50–250 | ~0–50 | - | - | [107] |

| 50–200 | ~0–50 | [129] |

5. CLTE of Polymer Composite Materials

5.1. CLTE of Different Types of Fillers

5.1.1. Ceramic Fillers

Silicon-Containing Materials

Aluminosilicates

Nitrides

Other Inorganic Salts

5.1.2. Carbon Particulate Fillers

5.1.3. Fiber and Fabric Reinforcements

| Filler | ΔT, °C | α, ppm/°C | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Si | 25–1227 | 2.6–4.6 | [194] |

| SiO2 (quartz glass) | 25–250 | 0.55 | [192] |

| Al2O3 (corundum) | 25–250 | 6.6 | [192] |

| 25–1000 | 9.1 | [219] | |

| 2MgO-2Al2O3-5SiO2 | 100–600 | 2.0–2.8 | [220] |

| Li2O-A12O3-SiO2 | 27 | −2.7 | [221] |

| LiAlSiO4 (β-eucryptite), along the crystallographic a-axis. | 20–1300 | 7.8 | [221] |

| LiAlSiO4 (β-eucryptite), along the crystallographic c-axis. | −17.5 | ||

| ZnO | - | 0.7 | [195] |

| AlN | 25–250 | 4.4 | [197] |

| BN | - | <1 | [195] |

| Si3N4 | - | 3.2 | [195] |

| Sc2(WO4)3 | −263–177 | −2.2 | [222] |

| PbTiO3 | 27 | −4 | [223] |

| CaTiO3 | 25–1000 | 13.4 | [214] |

| BaZrO3 | 25–1000 | 6.3 | [196] |

| ZrW2O8 | −273–77 | −9.1 | [224] |

| Zr2WP2O12 | 25–800 | −3.9–(−2.6) | [225] |

| (Mn0.96Fe0.04)3(Zn0.5Ge0.5)N | 43–113 | −25 | [197] |

| Bi0.95La0.05NiO3 | 27–97 | −137 | [198] |

| Amorphous carbon | 20–1400 | ~0.5–6 | [199] |

| Graphite (in-plane) | 0–300 | −0.5–(−1.5) | [202] |

| Graphite (out-of-plane) | 0–300 | 20–30 | [202] |

| Diamond powder | - | 0.8 | [195] |

| Graphene | −73–127 | ~−12–(−2.5) | [205] |

| MWCNT (axial direction) | −5–85 | ~−20–0 | [213] |

| 30–60 | ~−12 | [211] | |

| MWCNT (radial direction) | −263–47 | ~30 | [212] |

| Carbon fiber (longitudinal direction) | −200–1000 | −1.5–1 | [216,217,226] |

| Carbon fiber (transverse direction) | 5.5–30 | ||

| Glass fiber (longitudinal direction) | −50–350 | 5–6.0 | [216] |

| Glass fiber (transverse direction) | 22–25 | ||

| Basalt fiber (longitudinal direction) | −50–600 | 5.0–8.0 | [218] |

| Basalt fiber (transverse direction) | 7.0–12.0 |

5.2. Key Factors Governing the CLTE of Composite Materials

5.2.1. Influence of Polymer Matrix Properties

5.2.2. Influence of Filler Properties

CLTE of the Filler

Particle Size (Dispersion) of the Filler

Filler Orientation

Functionalization and Surface Modification of the Filler

5.2.3. Composite Structure

Filler Content

Interfacial Adhesion Between Matrix and Filler

Hybrid Composites

5.2.4. Processing Factors and CLTE Measurement Methodology

6. Discussion: Applications and Practical Significance of CLTE for Polymers and PCMs

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABS | acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene copolymer |

| AH | asymptotic homogenization |

| BMIs | bismaleimide resins |

| CAB | cellulose acetate butyrate |

| CLT | classical laminate theory |

| CLTE | coefficient of linear thermal expansion |

| CMs | composite materials |

| CNTs | carbon nanotubes |

| CTE | coefficient of thermal expansion |

| CVTE | coefficient of volumetric thermal expansion |

| ECTFE | ethylene chlorotrifluoroethylene (copolymer) |

| EMT | effective medium theory |

| ERs | epoxy resins |

| ETFE | ethylene tetrafluoroethylene (copolymer) |

| FEP | fluorinated ethylene propylene (TFE–HFP copolymer) |

| HDPE | high-density polyethylene |

| LCP | liquid-crystal polymer |

| LDPE | low-density polyethylene |

| LVDT | linear variable differential transformer |

| MWCNTs | multi-walled nanotubes |

| PA6 | polyamide 6 (nylon 6) |

| PA12 | polyamide 12 (nylon 12) |

| PA66 | polyamide 66 (nylon 66) |

| PAEK | polyaryletherketone (family) |

| PAI | polyamide-imide |

| PAR | polyarylate |

| PARA | polyarylamide (aromatic polyamide) |

| PBI | polybenzimidazole |

| PBT | polybutylene terephthalate |

| PC | polycarbonate |

| PCB | printed circuit board |

| PCMs | polymer composite materials |

| PCTFE | polychlorotrifluoroethylene |

| PDMS | polydimethylsiloxane |

| PE | polyethylene |

| PEI | polyetherimide |

| PEK | polyether ketone |

| PEKK | polyether ketone ketone |

| PEKEKK | poly(ether ketone ether ketone ketone) |

| PEEK | poly(ether ether ketone) |

| PEN | polyethylene naphthalate |

| PES | polyethersulfone |

| PFA | perfluoroalkoxy (TFE-based) copolymer |

| PFRs | phenol–formaldehyde resins |

| PET | poly(ethylene terephthalate) |

| PETG | glycol-modified poly(ethylene terephthalate) |

| PI | polyimide |

| PMMA | poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| PMP | poly(4-methyl-1-pentene) |

| PMPS | poly(methylphenylsiloxane) |

| POM | polyoxymethylene (acetal) |

| PP | polypropylene |

| PPA | polyphthalamide |

| PPO | poly(phenylene oxide) |

| PPS | poly(phenylene sulfide) |

| PPSU | poly(phenylsulfone) |

| PS | polystyrene |

| PSU | polysulfone |

| PTFE | polytetrafluoroethylene |

| PVDC | poly(vinylidene chloride) |

| PVDF | poly(vinylidene fluoride) |

| PVC | polyvinyl chloride |

| RVE | representative volume element |

| SAN | styrene–acrylonitrile copolymer |

| SWCNTs | single-walled nanotubes |

| Tg | glass transition temperature |

| TMA | thermomechanical analysis |

| TPU | thermoplastic polyurethane |

| UHMW-PE | ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene |

| PPP | poly(p-phenylene) |

References

- Miller, W.; Smith, C.W.; Mackenzie, D.S.; Evans, K.E. Negative thermal expansion: A review. J. Mater. Sci. 2009, 44, 5441–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Shi, C.; Li, P.; Guo, X.; Wang, B.; Zou, D. Thermal Expansion Challenges and Solution Strategies for Phase Change Material Encapsulation: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2409884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, K. Negative thermal expansion materials: Technological key for control of thermal expansion. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2012, 13, 013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somano, T.T. The Physical Properties of Thermal Expansion of Solid Matter. Am. J. Mod. Phys. 2022, 11, 79–84. Available online: http://ajmp.org/article/10.11648/j.ajmp.20221105.11 (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Siddiqui, M.S.; Fowler, D.W. Optimizing Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of Concrete and Its Importance on Concrete Structures. In Construction Materials and Structures; Ekolu, S.O., Dundu, M., Gao, X., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, L.; Deng, J.; Xing, X. Negative thermal expansion in functional materials: Controllable thermal expansion by chemical modifications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3522–3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drebushchak, V.A. Thermal expansion of solids: Review on theories. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 142, 1097–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.P.; Pandey, B.K.; Singh, A.K.; Srivastava, R.; Srivastava, H.C.; Upadhyay, M. Formulation of a Compression-Dependent Volume Thermal Expansion Coefficient Utilising the Equation of State. Int. Sci. J. Eng. Manag. 2025, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.Y.; Taylor, R.E. (Eds.) Thermal Expansion of Solids; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- James, J.D.; Spittle, J.A.; Brown, S.G.R.; Evans, R.W. A review of measurement techniques for the thermal expansion coefficient of metals and alloys at elevated temperatures. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2001, 12, R1–R15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Seki, T.; Ito, H.; Garcia-Garibay, M.A. Anisotropic Thermal Expansion as the Source of Macroscopic and Molecular-Scale Motion in Phosphorescent Amphidynamic Crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18003–18010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindler, A.; Vay, O.; Hansmann, C.; Müller, U. Dimensional stability of multi-layered wood-based panels: A review. Wood Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 969–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, S.; Sekiguchi, K.; Mizoroki, M.; Okada, T.; Ishige, R. Anisotropic Linear and Volumetric Thermal-Expansion Behaviors of Self-Standing Polyimide Films Analyzed by Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) and Optical Interferometry. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2018, 219, 1700354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprengel, W.; Würschum, R. High-Precision Dilatometry for the Study of Precipitation Processes and Microalloying Effects in Lightweight Alloys—A Specific Review. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2400426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escher, I.; Hahn, M.; Ferrero, G.A.; Adelhelm, P. A Practical Guide for Using Electrochemical Dilatometry as Operando Tool in Battery and Supercapacitor Research. Energy Technol. 2022, 10, 2101120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinkovic, B.A.; Machado, T.M.; de Avillez, R.R.; Madrid, A.; de Melo Toledo, P.H.; Andrade, G.F.S. Zero thermal expansion in ZrMg1−xZnxMo3O12. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 26567–26571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinlay, L.J.; Gerin, M.; Mittal, U.; Maynard-Casely, H.E.; Machon, D.; Radescu, S.; Sharma, N.; Pischedda, V. Pressure Behavior of the Zero Thermal Expansion Material Sc1.5Al0.5W3O12. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 2259–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, Y. Theoretical analyses of thermal shock and thermal expansion coefficients of metals and ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, A.; Kim, H.; Lee, M.-S.; Lee, S.-J. Thermal Behavior of Concrete: Understanding the Influence of Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of Concrete on Rigid Pavements. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Mirhakimi, A.S.; Elbestawi, M.A. Negative Thermal Expansion Metamaterials: A Review of Design, Fabrication, and Applications. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Zou, K.; Wang, B.; Yuan, X.; An, S.; Ma, Z.; Shi, K.; Deng, S.; Xu, J.; Yin, W.; et al. Zero Thermal Expansion Behavior in High-Entropy Anti-Perovskite Mn3Fe0.2Co0.2Ni0.2Mn0.2Cu0.2N. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2410608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukarov, S.; Petrushenko, S.; Sukhov, R.; Sukhov, V. Nanostructured Silver Films with a Low Coefficient of Thermal Expansion as a Promising Material for Nanoelectronics. Phys. Status Solidi A 2023, 220, 2200664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrille, B.; Vignoud, L.; Chapelon, L.-L.; Estevez, R. Advances in the Thermal Study of Polymers for Microelectronics Using the Thermally Induced Curvature Approach. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2024, 37, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, S.; Juneja, S. Comparative Analysis and Review of Materials Properties Used in Aerospace Industries: An Overview. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 48, 1609–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xie, Z.; Lu, T.; Liu, H.; Qiu, G.; Zhang, H. Design of Large-Scale Space Lattice Structure with Near-Zero Thermal Expansion Metamaterials. Aerospace 2023, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhao, X.; Lin, Y.; Sun, C. Thermo-optic coefficients of polymers for optical waveguide applications. Polymer 2006, 47, 4893–4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, A.J.T.; Mishra, A.; Park, I.; Kim, Y.-J.; Park, W.-T.; Yoon, Y.-J. Polymeric biomaterials for medical implants and devices. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2016, 2, 454–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieerad, A.R.; Bushroa, A.R.; Zalnezhad, E.; Sarraf, M.; Basirun, W.J.; Baradaran, S.; Nasiri-Tabrizi, B. Microstructural development and corrosion behavior of self-organized TiO2 nanotubes coated on Ti–6Al–7Nb. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 10844–10855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kul, M.; Akgül, B.; Karabay, Y.Z.; Hitzler, L.; Sert, E.; Merkel, M. Minimum and Stable Coefficient of Thermal Expansion by Three-Step Heat Treatment of Invar 36. Crystals 2024, 14, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, T. Thermal expansion of FeNi Invar and zinc-blende CdTe from the view point of local structure. Microstructures 2021, 1, 2021003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, L.; Pashayi, K.; Raeisi Fard, H.; Kotha, S.P.; Borca-Tasciuc, T.; Ozisik, R. Engineering the coefficient of thermal expansion and thermal conductivity of polymers filled with high aspect ratio silica nanofibers. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 58, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Hoshino, Y.; Katsura, N.; Ishii, J. Superheat-resistant polymers with low coefficients of thermal expansion. Polymer 2017, 111, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramakrishna, S.; Mayer, J.; Wintermantel, E.; Leong, K.W. Biomedical applications of polymer-composite materials: A review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2001, 61, 1189–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, N.; Jawaid, M. A review on thermomechanical properties of polymers and fibers reinforced polymer composites. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 67, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharbanda, S.; Bhadury, T.; Gupta, G.; Fuloria, D.; Pati, P.R.; Mishra, V.K.; Sharma, A. Polymer composites for thermal applications—A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 2839–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleşa, I.; Noţingher, P.V.; Schlögl, S.; Sumereder, C.; Muhr, M. Properties of Polymer Composites Used in High-Voltage Applications. Polymers 2016, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqui, S.I.; Robinson, I.M. Tensile dilatometric studies of deformation in polymeric materials and their composites. J. Mater. Sci. 1993, 28, 1421–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Banna, A.A.; McKenna, G.B. AFM dilatometry measurements on ultra-stable fluoropolymer glasses: Further evidence of extreme fictive temperature reduction. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Tan, R.; Feng, M.; Shen, W.; Lv, D.; Song, W. Humidity sensing using polymers: A critical review of current technologies and emerging trends. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas-Abadi, M.S. The effect of process and structural parameters on the stability, thermo-mechanical and thermal degradation of polymers with hydrocarbon skeleton containing PE, PP, PS, PVC, NR, PBR and SBR. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 143, 2867–2882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingler, A.; Gilberg, M.; Reisinger, D.; Schlögl, S.; Wetzel, B.; Krüger, J.-K. Thermal volume expansion as seen by temperature-modulated optical refractometry, Oscillating dilatometry and thermo-mechanical analysis. Polym. Test. 2024, 131, 108340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunkel, M.; Surm, H.; Steinbacher, M. Dilatometry. In Handbook of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry: Recent Advances, Techniques and Applications, 2nd ed.; Vyazovkin, S., Koga, N., Schick, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; Volume 6, pp. 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetton, R.E. Thermomechanical Methods. In Handbook of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry: Principles and Practice; Brown, M.E., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 363–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma, S.; Goyanes, S.N.; Duplaá, C. Development of a dilatometer based on diffractometry. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2002, 73, 3271–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Peng, X.; Fan, Y.; Lu, W. A method for measuring the thermal expansion of long samples using a heterodyne interferometer with two-color inline refractivity compensation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 190, 113186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, H.; Jervis, R.; Brett, D.J.L.; Shearing, P.R. Developments in dilatometry for characterisation of electrochemical devices. Batter. Supercaps 2021, 4, 1378–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, A.M.; Ren, Y.; Sarvestani, A.; Picu, C.R.; Varshney, V.; Nepal, D. Thermomechanical analysis (TMA) of vitrimers. Polym. Test. 2023, 118, 107877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruffino, G. Recent advances in optical methods for thermal expansion measurements. Int. J. Thermophys. 1989, 10, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Strycker, M.; Schueremans, L.; Van Paepegem, W.; Debruyne, D. Measuring the thermal expansion coefficient of tubular steel specimens with digital image correlation techniques. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2010, 48, 978–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Guo, J.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, Q. High-Accuracy Thermal Expansion Coefficient Measurement Based on Fiber-Optic EFPIs with Automatic Temperature Compensation. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 19359–19366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradere, C.; Batsale, J.-C.; Goyheneche, J.-M.; Pailler, R.; Dilhaire, S. Estimation of the transverse coefficient of thermal expansion on carbon fibers at very high temperature. Inverse Probl. Sci. Eng. 2007, 15, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hu, Z.; Yan, B.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H.; Ye, F.; Sun, B.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Ding, G.; et al. A flexible resistive strain gauge with reduced temperature effect via thermal expansion anisotropic composite substrate. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eim, S.; Jo, S.; Kim, J.; Park, S.; Lee, D.; Russell, T.P.; Ryu, D.Y. Insights into the Thermal Expansion of Amorphous Polymers. ACS Macro Lett. 2024, 13, 1490–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisuriyachot, J.; Singhapong, W.; Rodriguez Santana, P.; Sangan, C.M.; Bowen, C.; Dolbnya, I.P.; Butler, R.; Lunt, A.J.G. Quantification of the thermal expansion of carbon fibres in CFRP at low temperatures using X-ray diffraction. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 305, 112697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buryachenko, V.A. Micromechanics of Heterogeneous Materials; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhvalov, N.; Panasenko, G. Homogenisation: Averaging Processes in Periodic Media: Mathematical Problems in the Mechanics of Composite Materials; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panasenko, G. Multi-Scale Modelling for Structures and Composites; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.-M.; Park, S.-H.; Youn, S.-K. Design of microstructures of viscoelastic composites for optimal damping characteristics. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2000, 37, 4791–4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.W.; Li, Q. The design of functional gradient materials with inverse homogenization method. Adv. Mater. Res. 2008, 32, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiglhofer, W.S. On the inverse homogenization problem of linear composite materials. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2001, 28, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamaian, S.S.; Mackay, T.G. On limitations of the Bruggeman formalism for inverse homogenization. J. Nanophotonics 2010, 4, 043510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vatulyan, A.O.; Yurov, V.O. On a new approach to identifying inhomogeneous mechanical properties of elastic bodies. Izv. Saratov Univ. Math. Mech. Inform. 2024, 24, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, W. Ueber die Beziehung zwischen den beiden Elasticitätsconstanten isotroper Körper. Ann. Phys. 1889, 274, 573–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuss, A. Berechnung der Fließgrenze von Mischkristallen auf Grund der Plastizitätsbedingung für Einkristalle. Z. Angew. Math. Mech. 1929, 9, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapery, R.A. Thermal Expansion Coefficients of Composite Materials Based on Energy Principles. J. Compos. Mater. 1968, 2, 380–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, J.-H.; Jeon, Y.-J.; Kang, M.-S. Effective Properties for the Design of Basalt Particulate–Polymer Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupski, J.; Zweifel, L.; Preinfalck, M.; Baz, S.; Hajikazemi, M.; Brauner, C. Coefficients of Thermal Expansion in Aligned Carbon Staple Fiber-Reinforced Polymers: Experimental Characterization with Numerical Investigation. Polymers 2025, 17, 1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashin, Z.; Shtrikman, S. A Variational Approach to the Theory of the Elastic Behaviour of Multiphase Materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 1963, 11, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, V.M. Thermal Expansion Coefficient of Heterogeneous Materials. Mech. Solids 1967, 2, 58–61. [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, B.W.; Hashin, Z. Effective Thermal Expansion Coefficients and Specific Heats of Composite Materials. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1970, 8, 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, W.; Gregorová, E. Critical Assessment 18: Elastic and thermal properties of porous materials—Rigorous bounds and cross-property relations. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2015, 31, 1801–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarenko, L.; Stolarski, H.; Khoroshun, L.; Altenbach, H. Effective thermo-elastic properties of random composites with orthotropic components and aligned ellipsoidal inhomogeneities. Int. J. Solids Struct. 2018, 136–137, 220–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwu, C. Mechanics of Laminated Composite Structures, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2024; 415p. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, J.; Li, Y. An Analytical Model for Cure-Induced Deformation of Composite Laminates. Polymers 2022, 14, 2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taibi, N.; Belabed, Z.; Boucham, B.; Benguediab, M.; Tounsi, A.; Khedher, K.M.; Salem, M.A. On the Thermomechanical Behavior of Laminated Composite Plates Using Different Micromechanical-Based Models for Coefficients of Thermal Expansion (CTE). J. Appl. Comput. Mech. 2024, 10, 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhvalov, N.S. Averaged characteristics of bodies with periodic structure. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1974, 218, 1046–1048. [Google Scholar]

- Gorbachev, V.I. The homogenization method of Bakhvalov–Pobedrya in the composite mechanics. Mosc. Univ. Mech. Bull. 2016, 71, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Palencia, E. Non-Homogeneous Media and Vibration Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, C.; Lv, J.; Zu, L.; Liu, L.; Mei, H. Prediction of thermo-mechanical properties of 8-harness satin-woven C/C composites by asymptotic homogenization. Materials 2024, 17, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.; Arora, G.; Singh, M.K.; Ayyappan, V.; Bhowmik, P.; Rangappa, S.M.; Siengchin, S. Review of Machine Learning Approaches for Predicting Mechanical Behavior of Composite Materials. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracheva, E.; Lambard, G.; Samitsu, S.; Sodeyama, K.; Nakata, A. Prediction of the Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion for the Amorphous Homopolymers Based on Chemical Structure Using Machine Learning. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. Methods 2021, 1, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulkir, O. Artificial intelligence techniques for thermomechanical property optimization of metal-PLA composites additive manufactured parts. Measurement 2025, 256, 118089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malashin, I.; Tynchenko, V.; Gantimurov, A.; Nelyub, V.; Borodulin, A. A Multi-Objective Optimization of Neural Networks for Predicting the Physical Properties of Textile Polymer Composite Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fahem, N.; Belaidi, I.; Oulad Brahim, A.; Noori, M.; Khatir, S.; Abdel Wahab, M. Prediction of Resisting Force and Tensile Load Reduction in GFRP Composite Materials Using Artificial Neural Network-Enhanced Jaya Algorithm. Compos. Struct. 2022, 304, 116326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. Handbook of Polymers, 2nd ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, C.; Yung, P.W.S.; Chen, A.; Acquaye, A. Review and recommendations for sustainable pathways of recycling commodity plastic waste across different economic regions. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 14, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulkatov, D.P.; Storozhuk, I.P.; Khina, A.G.; Kuleznev, A.S.; Buryakov, V.S.; Prokopova, E.V. Novel Melt-Processible Copolyetherimides Based on 4,4′-diaminodiphenylmethane: Synthesis and Study. Pol. Sci. Ser. B 2025, 67, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storozhuk, I.P.; Khina, A.G.; Bulkatov, D.P.; Buryakov, V.S.; Kuleznev, A.S. Synthesis and study of melt processing of polyarylate–polysulfone cardo block copolymers. Polym. Sci. Ser. B 2024, 66, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idumah, C.I. Thermal expansivity of polymer nanocomposites and applications. Polym.-Plast. Technol. Mater. 2023, 62, 1178–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Fang, Z.; Yi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Meng, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, K. Ultra-low loss polyphenylene oxide-based composites with negative thermal expansion fillers. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawlins, J.W.; Whittermore, J. In Commodity Plastics. In Polymer Grafting and Crosslinking, 1st ed.; Bhattacharya, A., Rawlins, J.W., Ray, P., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Xu, X.; Lee, S.; Zhang, Y.; Kim, B.J.; Wu, Q. High density polyethylene composites reinforced with hybrid inorganic fillers: Morphology, mechanical and thermal expansion performance. Materials 2013, 6, 4122–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmos, D.; Fernández, J.F.; González-Benito, G.; González-Benito, J. Effect of the presence of silica nanoparticles on the coefficient of thermal expansion of LDPE thin films measured by AFM. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 1495–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.; Satapathy, A. Thermal and dielectric behaviour of polypropylene composites reinforced with ceramic fillers. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2015, 26, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Hing, P.; Hu, X. Thermal expansion behaviour of polystyrene–aluminium nitride composites. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2000, 33, 1606–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, E.N. Engineering thermoplastics—Materials, properties, trends. In Applied Plastics Engineering Handbook: Processing, Materials, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Kutz, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. PET poly(ethylene terephthalate). In Handbook of Polymers, 2nd ed.; Wypych, G., Ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; pp. 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Lee, H.-L.; Ha, S.-M.; Jeon, B.-K.; Won, J.-C.; Lee, S.-G. Effect of graphite and carbon fiber contents on the morphology and properties of thermally conductive composites based on polyamide 6. Polym. Int. 2014, 63, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, P.; Sambale, A.K.; Uhlig, K.; Stommel, M.; Schneider, B.; Kaiser, J.-M. Hygromechanical Behavior of Polyamide 6.6: Experiments and Modeling. Polymers 2023, 15, 3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. PC polycarbonate. In Handbook of Polymers, 2nd ed.; Wypych, G., Ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; pp. 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storozhuk, I.P.; Bulkatov, D.P.; Khina, A.G.; Buryakov, V.S.; Kuleznev, A.S.; Orlov, M.A. Development of Polyethersulfones for Modification of Epoxy Resins. Polym. Sci. Ser. B 2024, 66, 514–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyase, A.; Qu, S.; Lo, K.H.; Wang, S.S. Elevated-Temperature Thermal Expansion of PTFE/PEEK Matrix Composite with Random-Oriented Short Carbon Fibers and Graphite Flakes. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 2020, 142, 021002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M. Development of Solution-Processable, Optically Transparent Polyimides with Ultra-Low Linear Coefficients of Thermal Expansion. Polymers 2017, 9, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Koseki, K. Poly(ester imide)s Possessing Low Coef-cient of Thermal Expansion and Low Water Absorption. High Perform. Polym. 2006, 18, 697–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Chen, H.; Song, G.; Dai, F.; Chen, C.; Yao, J. Superheat-resistant polyimides with ultra-low coefficients of thermal expansion. Polymer 2020, 196, 122482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottiger, M.T.; Coburn, J.C.; Edman, J.R. The effect of orientation on thermal expansion behavior in polyimide films. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 1994, 32, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Numata, S.; Fujisaki, K.; Kinjo, N. Re-examination of the relationship between packing coefficient and thermal expansion coefficient for aromatic polyimides. Polymer 1987, 28, 2282–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Watanabe, T.; Ishii, J.; Sekiguchi, T.; Narita, Y.; Horiuchi, S. High-temperature polymers overcoming the trade-off between excellent thermoplasticity and low thermal expansion properties. Polymer 2016, 99, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhao, Z.-K.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Li, Y.-Q.; Fu, Y.-Q.; Sun, B.-G.; Shi, H.-Q.; Huang, P.; Hu, N.; Fu, S.-Y. Mechanical, tribological and thermal properties of injection molded short carbon fiber/expanded graphite/polyetherimide composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 201, 108498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Drzal, L.T. Effects of graphene nanoplatelets on the coefficient of thermal expansion of polyetherimide composite. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2014, 146, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, M.; Horii, S. Low-CTE Polyimides Derived from 2,3,6,7-Naphthalenetetracarboxylic Dianhydride. Polym. J. 2007, 39, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Zhai, L.; He, M.; Wang, C.; Mo, S.; Fan, L. Preparation of heat-resistant poly(amide-imide) films with ultralow coefficients of thermal expansion for optoelectronic application. React. Funct. Polym. 2019, 141, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, M.; Mo, C.; He, L.; Feng, X.; Liu, X.; Tong, L. Strong and tough semi-crystalline poly(aryl ether nitrile) with low coefficient of thermal expansion. Polymer 2024, 308, 127363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mossety-Leszczak, B.; Kisiel, M. Liquid Crystalline Polymers. In Thermal Analysis of Polymeric Materials: Methods and Developments; Pielichowski, K., Pielichowska, K., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2022; Volume 1, pp. 381–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turek, D.E.; Simon, G.P.; Tiu, C. Relationships Among Rheology, Morphology, and Solid-State Properties in Thermotropic Liquid-Crystalline Polymers; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 307–333. [Google Scholar]

- Maitra, A.; Das, T.; Das, C.K. Liquid Crystalline Polymer and Its Composites: Chemistry and Recent Advances. In Liquid Crystalline Polymers: Volume 2—Processing and Applications; Thakur, V.K., Kessler, M.R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.A.; Al-Sarraf, A.R. Study the contrast of thermal expansion behavior for PMMA denture base, single and hybrid reinforced using the thermomechanical analysis technique (TMA). AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2769, 020027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, J.; Castillo, E.; Cruz-Caldito, J.F. Determination of the linear coefficient of thermal expansion in polymer films at the nanoscale: Influence of the composition of EVA copolymers and the molecular weight of PMMA. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 18495–18500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudescu, M.C.; Botean, A.; Hârdău, M. Thermal expansion coefficient determination of polymeric materials using digital image correlation. Mater. Plast. 2013, 50, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, Y.-T.; Fasulo, P.D.; Rodgers, W.R.; Yoo, Y.-T.; Yoo, Y.; Paul, D.R. Properties of polycarbonate/acrylonitrile–butadiene–styrene/talc composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 124, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyavahare, S.A.; Kharat, B.M.; More, A.P. Polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) blends and composites: A review. Vietnam J. Chem. 2024, 62, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. PPA polyphthalamide. In Handbook of Polymers, 2nd ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; pp. 514–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, P.; Shirinbayan, M.; Tcharkhtchi, A.; Fitoussi, J.; Bakir, F. Overall investigation of poly(phenylene sulfide) from synthesis and process to applications—A review. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2019, 304, 1800686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. PSU polysulfone. In Handbook of Polymers, 2nd ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; pp. 580–585. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-H.; Lan, N.X.V.; Kulkarni, U.; Kim, C.; Cho, S.M.; Yoo, P.J.; Kim, D.; Schroeder, M.; Yi, G.-R. Optically transparent and low-CTE polyethersulfone-based nanocomposite films for flexible display. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 7, 2001422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez-Pascual, A.M.; Díez-Vicente, A.L. Effect of TiO2 nanoparticles on the performance of polyphenylsulfone biomaterial for orthopaedic implants. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 7502–7514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patki, A.M.; Goyal, R.K. High performance polyetherketone-hexagonal boron nitride nanocomposites for electronic applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 3899–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, K.; Kafi, A.; Simons, R.; Bateman, S. Optimization of material extrusion additive manufacturing process parameters for polyether ketone ketone (PEKK). Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 126, 1067–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; He, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, S. Progress in Aromatic Polyimide Films for Electronic Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-Y.; Huang, Y.-L.; Ma, C.-C.M.; Yuen, S.-M.; Teng, C.-C.; Yang, S.-Y. Mechanical, thermal and electrical properties of aluminum nitride/polyetherimide composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2011, 42, 1573–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. LCP liquid crystalline polymers. In Handbook of Polymers, 2nd ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; pp. 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Dallaev, R.; Pisarenko, T.; Papež, N.; Sadovský, P.; Holcman, V. A Brief Overview on Epoxies in Electronics: Properties, Applications, and Modifications. Polymers 2023, 15, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wazalwar, R.; Sahu, M.; Raichur, A.M. Mechanical properties of aerospace epoxy composites reinforced with 2D nano-fillers: Current status and road to industrialization. Nanoscale Adv. 2021, 10, 2741–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kausar, A. Epoxy and quantum dots-based nanocomposites: Achievements and applications. Mater. Res. Innov. 2020, 24, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mula, V.R.; Ramachandran, A.; Pudukarai Ramasamy, T. A review on epoxy granite reinforced polymer composites in machine tool structures—Static, dynamic and thermal characteristics. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 2022–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, M.; Zhou, Z.; Gou, J.; Hui, D. 3D printing of polymer matrix composites: A review and prospective. Compos. Part B Eng. 2017, 110, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, L.-L.; Hong, W.-J.; Yang, S.-Y. Improved Melt Processabilities of Thermosetting Polyimide Matrix Resins for High Temperature Carbon Fiber Composite Applications. Polymers 2022, 14, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korolev, A.; Mishnev, M.; Ulrikh, D.V. Non-Linearity of Thermosetting Polymers’ and GRPs’ Thermal Expanding: Experimental Study and Modeling. Polymers 2022, 14, 4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leroy, E.; Dupuy, J.; Maazouz, A.; Seytre, G. Evolution of the coefficient of thermal expansion of a thermosetting polymer during cure reaction. Polymer 2005, 46, 9919–9927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrelli, M.; Skordos, A.A.; Partridge, I.K. Investigation of Cure-Induced Shrinkage in Unreinforced Epoxy Resin. Plast. Rubber Compos. 2002, 31, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.-W.; Zhang, H.-J.; Gao, Y.; Wang, X.-Q.; Leng, J.-S. Effect of Post-Cure on the Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of Composite Materials. J. Solid Rocket Technol. 2013, 36, 246–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoney, I.; Pethrick, R.A. Low coefficient of thermal expansion of thermoset composite materials. Proc. IMechE Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2012, 226, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Duan, Y.; Wang, H.; Hui, J.; Qi, J. Bio-based trifunctional diphenolic acid epoxy resin with high glass transition temperature and low thermal expansion: Synthesis and properties. Polym. Bull. 2023, 80, 10457–10471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athawale, A.A.; Pandit, J.A. Unsaturated Polyester Resins, Blends, Interpenetrating Polymer Networks, Composites and Nanocomposites: State of the Art and New Challenges. In Unsaturated Polyester Resins: Fundamentals, Design, Fabrication, and Applications; Thomas, S., Hosur, M., Chirayil, C.J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.G.; Yang, L.-S. Preparation, Properties and Applications of Unsaturated Polyesters. In Modern Polyesters: Chemistry and Technology of Polyesters and Copolyesters; Scheirs, J., Long, T.E., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2003; pp. 699–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Romero, P.; Zhang, H.; Huang, M.; Lai, F.-J. Unsaturated polyester resin concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 228, 116709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, F.; Hu, W.; Song, L.; Hu, Y. State-of-the-Art Research in Flame-Retardant Unsaturated Polyester Resins: Progress, Challenges and Prospects. Fire Technol. 2024, 60, 1077–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrighetti, C.; Tassone, P.; Ciardelli, F.; Ruggeri, G. Reduction of the thermal expansion of unsaturated polyesters by chain-end modification. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2005, 90, 346–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faitel’son, E.A.; Korkhov, V.P.; Aniskevich, A.N.; Starkova, O.A. Effects of Moisture and Stresses on the Structure and Properties of Polyester Resin. Mech. Compos. Mater. 2004, 40, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdnikova, P.V.; Zhizhina, E.G.; Pai, Z.P. Phenol-formaldehyde resins: Properties, fields of application, and methods of synthesis. Catal. Ind. 2021, 13, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, L.; Sreekala, M.S.; Kumar, S.A.; Thomas, S. A comprehensive review on phenol-formaldehyde resin-based composites and foams. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 8602–8621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, D.; Shalash, M.; El-Bahy, S.M.; Wu, Z.; Ren, J.; Guo, Z.; El-Bahy, Z.M. A comprehensive review on modified phenolic resin composites for enhanced performance across various applications. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 8731–8769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A.; Ibeh, C.C. Phenol-formaldehyde resins. In Handbook of Thermoset Plastics, 4th ed.; Dodiuk, H., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 13–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Jiang, X.; Li, S.; Zhu, M. An Overview of Recycling Phenolic Resin. Polymers 2024, 16, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iredale, R.J.; Ward, C.; Hamerton, I. Modern advances in bismaleimide resin technology: A 21st century perspective on the chemistry of addition polyimides. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 69, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; He, Q.; Zeng, X.; Ma, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X. Molecular design and application of low dielectric bismaleimide resin. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 5859–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanaa Iyer, N.; Arunkumar, N. Review on fiber reinforced/modified bismaleimide resin composites for aircraft structure application. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 923, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Chi, Q. Improved heat resistance and electrical properties of epoxy resins by introduction of bismaleimide. J. Electron. Mater. 2023, 52, 1865–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Sun, Q.; Guo, J.; Wang, C. High-performance bismaleimide resin with an ultralow coefficient of thermal expansion and high thermostability. Macromolecules 2024, 57, 1808–1818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeyns, C.; Picard, L.; Ganachaud, F. Synthesis, characterization and modification of silicone resins: An augmented review. Prog. Org. Coat. 2018, 125, 287–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Jiang, B. Silicone resin applications for heat-resistant coatings: A review. Polym. Sci. Ser. C 2023, 65, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.V.; Minyaylo, E.O.; Temnikov, M.N.; Mukhtorov, L.G.; Atroshchenko, Y.M. Silicones in Cosmetics. Polym. Sci. Ser. B 2023, 65, 578–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchin, G.; Elsayed, H.; Botti, R.; Huang, K.; Schmidt, J.; Giometti, G.; Zanini, A.; De Marzi, A.; D’Agostini, M.; Scanferla, P.; et al. Additive manufacturing of ceramics from liquid feedstocks. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2022, 1, 100012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, M.A. Functional silicone oils and elastomers: New routes lead to new properties. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 12813–12829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, W.; Ree, M. Anisotropic thermal expansion behavior of thin films of polymethylsilsesquioxane, a spin-on-glass dielectric for high-performance integrated circuits. Langmuir 2004, 20, 6932–6939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, X.; Wang, J.; Qi, B.; Hu, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Lin, Z.; Sun, R. SiO2/SiC binary systems reinforced epoxy resins with high thermal conductivity and low CTE as underfill for 2.5D/3D electronic packaging. Compos. Commun. 2025, 56, 102353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liang, Z.; Gonnet, P.; Liao, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, C. Effect of nanotube functionalization on the coefficient of thermal expansion of nanocomposites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2007, 17, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xue, Y.; Li, X.; Wen, Y.; Liu, J.; Xue, Z.; Shi, D.; Zhou, X.; Xie, X.; Mai, Y.-W. High-performance epoxy/binary spherical alumina composite as underfill material for electronic packaging. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2019, 118, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Chun, H.; Park, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J.; Oh, C.H. Preparation and curing chemistry of ultra-low CTE epoxy composite based on the newly-designed triethoxysilyl-functionalized ortho-cresol novolac epoxy. Polymer 2018, 147, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chieruzzi, M.; Miliozzi, A.; Kenny, J.M. Effects of the nanoparticles on the thermal expansion and mechanical properties of unsaturated polyester/clay nanocomposites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2013, 45, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoun, L.; Palardy, G.; Hubert, P. Relation between volumetric changes of unsaturated polyester resin and surface finish quality of fiberglass/unsaturated polyester composite panels. Polym. Compos. 2011, 32, 1473–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, J.; Kimura, H.; Hirota, K.; Kido, H. Thermal expansion and mechanical properties of phenolic resin/ZrW2O8 composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 106, 3343–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogata, M.; Kinjo, N.; Kawata, T. Effects of crosslinking on physical properties of phenol–formaldehyde novolac cured epoxy resins. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1993, 48, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottram, J.T.; Geary, B.; Taylor, R. Thermal expansion of phenolic resin and phenolic-fibre composites. J. Mater. Sci. 1992, 27, 5015–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypych, G. BMI polybismaleimide. In Handbook of Polymers, 2nd ed.; ChemTec Publishing: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2016; pp. 21–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.D.; Li, S.; Zhang, S.; Liu, X.W.; Wong, C.P. Thermo and dynamic mechanical properties of the high refractive index silicone resin for light emitting diode packaging. IEEE Trans. Compon. Packag. Manuf. Technol. 2014, 4, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhang, H.; Tang, M.; Tu, W.; Zhang, X. Improved thermal property of a multilayered graphite nanoplatelets filled silicone resin composite. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2014, 24, 920–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhou, W.; Wang, H.; Luo, F.; Zhu, D. Preparation and properties of carbonyl iron particles (CIPs)/silicone resin composite with negative thermal expansion filler. J. Polym. Res. 2015, 22, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, K.; Hussain, A.; Habib, A.; Maqbool, M.; Khan, M.B.; Hussain, M.; Khan, Y.; Raza, G. Computational design and development of high-performance polymer composites for backside encapsulation of concentrated photovoltaic (CPV) systems. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 5617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, R.; Singh, M.; Shekhawat, D.; Lee, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J. The role of fillers to enhance the mechanical, thermal, and wear characteristics of polymer composite materials: A review. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2023, 175, 107775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Huang, S.; Lv, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Sun, R. Novel polyimides with improved adhesion to smooth copper and low coefficient of thermal expansion. Polymer 2023, 285, 126388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Liu, H.; Yan, F.; Ma, C. Manufacturing technologies of polymer composites—A review. Polymers 2023, 15, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, G.; Barkanov, E. Design of near-zero thermal expansion polymer composites. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 5th KhPI Week on Advanced Technology (KhPIWeek), Kharkiv, Ukraine, 7–11 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Peng, C.; Zhao, L.; Huang, A.; Wei, M.; Yuan, C.; Xu, Y.; Zeng, B.; Chen, G.; Luo, W.; et al. Preparation of highly thermally conductive, flexible and transparent AlOOH/polyimide composite film with high mechanical strength and low coefficient of thermal expansion. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 281, 111558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroisová, D.; Dvořáčková, Š.; Kůsa, P. Use of Thermomechanical Analysis in the Design of a Composite System with a Low Coefficient of Longitudinal Thermal Expansion for End Gauges. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 21, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravola, M.; Cortes, P.; Juhasz, M.; Rutana, D.; Kowalczyk, B.; Conner, B.; MacDonald, E. Development of a Low Coefficient of Thermal Expansion Composite Tooling via 3D Printing. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition (IMECE 2018), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 9–15 November 2018. Paper No. IMECE2018-88594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Luo, J.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ding, G.; Wang, Z. Development of a polyimide/SiC-whisker/nano-particles composite with high thermal conductivity and low coefficient of thermal expansion as dielectric layer for interposer application. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 68th Electronic Components and Technology Conference (ECTC), San Diego, CA, USA, 29 May–1 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, R.S.; Jacob, S.; Murthy, C.R.L.; Balachandran, P.; Rao, Y.V.K.S. Hybridization of carbon–glass epoxy composites: An approach to achieve low coefficient of thermal expansion at cryogenic temperatures. Cryogenics 2011, 51, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Shen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, W. Thermal and Tensile Properties Preparation of Negative Thermal Expansion Polymer Composite ZrW2O8–Cf/E51. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2022, 230, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, C. Two Decades of Negative Thermal Expansion Research: Where Do We Stand? Materials 2012, 5, 1125–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottigar, S.A.; Santhosh, B.; Nair, R.G.; Punith, P.; Guruprasad, P.J.; Naik, N.K. Three-dimensional braided composites with zero, negative and isotropic thermal expansion behavior. J. Compos. Mater. 2020, 54, 1761–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.P.; Bollampally, R.S. Thermal Conductivity, Elastic Modulus, and Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of Polymer Composites Filled with Ceramic Particles for Electronic Packaging. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 74, 3396–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, M.T.; Jantunen, H. Polymer–Ceramic Composites of 0–3 Connectivity for Circuits in Electronics: A Review. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2010, 7, 415–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, Y.; Tokumaru, Y. Precise Determination of Lattice Parameter and Thermal Expansion Coefficient of Silicon Between 300 and 1500 K. J. Appl. Phys. 1984, 56, 314–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.M.; Mariatti, M.; Busfield, J.J.C. Effects of types of fillers and filler loading on the properties of silicone rubber composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2011, 30, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Gu, A.; Jiao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liang, G.; Hu, J.-T.; Yao, W.; Yuan, L. High-performance hexagonal boron nitride/bismaleimide composites with high thermal conductivity, low coefficient of thermal expansion, and low dielectric loss. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2012, 23, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenaka, K.; Takagi, H. Giant negative thermal expansion in Ge-doped anti-perovskite manganese nitrides. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2005, 87, 261902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, M.; Chen, W.-T.; Seki, H.; Czapski, M.; Smirnova, O.; Oka, K.; Mizumaki, M.; Watanuki, T.; Ishimatsu, N.; Kawamura, N.; et al. Colossal negative thermal expansion in BiNiO3 induced by intermetallic charge transfer. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-G.; Li, K.-Z.; Li, H.-J.; Wang, C.; Zhai, Y.-Q. The thermal expansion of carbon/carbon composites from room temperature to 1400 °C. J. Mater. Sci. 2006, 41, 8356–8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, J.E.; Perottoni, C.A. Thermal expansion of graphite revisited. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 199, 110719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Tang, J.; Zhou, M.; Shen, K. A review of the coefficient of thermal expansion and thermal conductivity of graphite. New Carbon Mater. 2022, 37, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, W.C. Thermal expansion coefficients of graphite crystals. Carbon 1972, 10, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostanovskiy, A.V.; Zeodinov, M.G.; Kostanovskaya, M.E.; Pronkin, A.A. Temperature dependence of the thermal coefficient of linear expansion. Therm. Eng. 2022, 69, 802–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K.; Morozov, S.V.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Dubonos, S.V.; Grigorieva, I.V.; Firsov, A.A. Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 2004, 306, 666–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, D.; Son, Y.-W.; Cheong, H. Negative Thermal Expansion Coefficient of Graphene Measured by Raman Spectroscopy. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3227–3231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandin, A.A.; Ghosh, S.; Bao, W.; Calizo, I.; Teweldebrhan, D.; Miao, F.; Lau, C.N. Superior Thermal Conductivity of Single-Layer Graphene. Nano Lett. 2008, 8, 902–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urade, A.R.; Lahiri, I.; Suresh, K.S. Graphene Properties, Synthesis and Applications: A Review. JOM 2023, 75, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Gao, F.; Sun, L.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Terrones, M.; Wang, Y. Surface Modification Methods and Mechanisms in Carbon Nanotubes Dispersion. Carbon 2023, 212, 118133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sizov, V.A.; Denisyuk, A.P.; Khina, A.G.; Demidova, L.A. 1,1′-Ferrocenedicarboxylic Acid Salts as Burning Rate Modifiers of Double-Base Propellant. J. Propuls. Power 2022, 38, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-T.; Sun, K.; Luo, D.; Wang, Y.-M.; Han, L.; Liu, H.; Guo, X.-L.; Yu, D.-L.; Ren, T.-L. A Review on Low-Dimensional Novel Optoelectronic Devices Based on Carbon Nanotubes. AIP Adv. 2021, 11, 110701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasu, K.; Yamamoto, G.; Tamaki, I.; Ogasawara, T.; Shimamura, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Hashida, T. Negative Axial Thermal Expansion Coefficient of Carbon Nanotubes: Experimental Determination Based on Measurements of Coefficient of Thermal Expansion for Aligned Carbon Nanotube Reinforced Epoxy Composites. Carbon 2015, 95, 904–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandow, S. Radial Thermal Expansion of Purified Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes Measured by X-ray Diffraction. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 36, 1403–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirasu, K.; Nakamura, A.; Yamamoto, G.; Ogasawara, T.; Shimamura, Y.; Inoue, Y.; Hashida, T. Potential Use of CNTs for Production of Zero Thermal Expansion Coefficient Composite Materials: An Experimental Evaluation of Axial Thermal Expansion Coefficient of CNTs Using a Combination of Thermal Expansion and Uniaxial Tensile Tests. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2017, 95, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, D.K.; Wagh, P.H.; Linul, E. Manufacturing Technologies of Carbon/Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites and Their Properties: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideridis, E. Thermal expansion coefficients of fiber composites defined by the concept of the interphase. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1994, 51, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Iglesias, R.; Cappello, R.; Thomsen, O.T.; Dulieu-Barton, J.M. Estimating the coefficients of thermal expansion of carbon fibre composite materials using infrared thermography. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 198, 109094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Morgan, R.J. Characterization of microcrack development in BMI–carbon fiber composite under stress and thermal cycling. J. Compos. Mater. 2004, 38, 2007–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavalan, V.; Sivagamasundari, R. Thermal expansion coefficient of basalt fibre reinforced polymer bars. Int. J. Res. Eng. Appl. Manag. (IJREAM) 2019, 5, 414–418. Available online: https://ijream.org/papers/IJREAMV05I0149156.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Gladysz, G.M.; Chawla, K.K. Coefficients of thermal expansion of some laminated ceramic composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2001, 32, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuščer, D.; Bantan, I.; Hrovat, M.; Malič, B. The microstructure, coefficient of thermal expansion and flexural strength of cordierite ceramics prepared from alumina with different particle sizes. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 37, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostertag, W.; Fischer, G.R.; Williams, J.P. Thermal expansion of synthetic β-spodumene and β-spodumene–silica solid solution. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 1968, 51, 651–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, X.; Yu, W.; Wang, X.; Wu, B.; Wang, M. Effect of Ti content on the microstructure and properties of Sc2W3O12 particle-reinforced Ag–Cu–Ti brazing alloy joints for brazing SiC and Cu. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 47, 113174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirane, G.; Hoshino, S. On the phase transition in lead titanate. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1951, 6, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.O. Negative thermal expansion materials. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1999, 19, 3317–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.W.; Zhou, Q.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, B. Preparation and properties of Zr2WP2O12 with negative thermal expansion without sintering additives. Process. Appl. Ceram. 2020, 14, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, D.E.; Tompkins, S.S. Prediction of Coefficients of Thermal Expansion for Unidirectional Composites. J. Comp. Mater. 1989, 23, 370–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Feng, Y.; Guo, J.; Wang, C. High performance epoxy resin with ultralow coefficient of thermal expansion cured by conformation-switchable multi-functional agent. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 450, 138295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynov, O.; Hasanov, S.; Fidan, I. Influence of the matrix material on the thermal properties of the short carbon fiber reinforced polymer composites manufactured by material extrusion. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 92, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavchev, I.; Petrova, K.T.; Ivanova, M. Determination of the coefficient of thermal expansion of epoxy composites. Polym. Test. 2002, 21, 177–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSarkar, M.; Senthilkumar, P.; Franklin, S.; Chatterjee, G. Effect of particulate fillers on thermal expansions and other critical performances of polycarbonate-based compositions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2011, 124, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Benito, J.; Castillo, E.; Caldito, J.F. Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of TiO2-Filled EVA-Based Nanocomposites: A New Insight into the Influence of Filler Particle Size in Composites. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 1747–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.-S.; Bouveret, B.; Suhr, J.; Gibson, R.F. Combined numerical/experimental investigation of particle diameter and interphase effects on coefficient of thermal expansion and young’s modulus of SiO2/epoxy nanocomposites. Polym. Compos. 2012, 33, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.Y.; Fu, J.F.; Yu, W.Q.; Huang, L.; Yin, J.T.; Dong, X.; Zong, P.S.; Lu, Q.; Shang, D.P.; Shi, L.Y. Enhanced Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Epoxy Composites by Spherical Silica with Different Size. Key Eng. Mater. 2017, 727, 519–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.-Y.; Li, X.-K.; Zhang, X.-N.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Ai, K. The effect of carbon fiber length on the thermal expansion of fiber-reinforced particulate hybrid composites. Polym. Compos. 2024, 46, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, M.; Jang, J.; Suhr, J. Effect of filler geometry on coefficient of thermal expansion in carbon nanofiber reinforced epoxy composites. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2011, 11, 1098–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawab, Y.; Jacquemin, F.; Casari, P.; Boyard, N.; Borjon-Piron, Y.; Sobotka, V. Study of variation of thermal expansion coefficients in carbon/epoxy laminated composite plates. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 50, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Liu, Y.; Raghavan, S.; Moon, K.-S.; Sitaraman, S.K.; Wong, C.-P. Magnetic alignment of hexagonal boron nitride platelets in polymer matrix: Toward high performance anisotropic polymer composites for electronic encapsulation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2013, 5, 7633–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhi, C.; Jiang, P.; Golberg, D.; Bando, Y.; Tanaka, T. Polyhedral Oligosilsesquioxane-Modified Boron Nitride Nanotube Based Epoxy Nanocomposites: An Ideal Dielectric Material with High Thermal Conductivity. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2012, 23, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Jin, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, W. Improved coefficient thermal expansion and mechanical properties of PTFE composites for high-frequency communication. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2023, 241, 110142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, A.; Ansari, R.; Aghdam, M.K.H.; Jamali, J. Numerical prediction of thermal conductivity and thermal expansion coefficient of glass fiber-reinforced polymer hybrid composites filled with hollow spheres. J. Compos. Mater. 2024, 58, 1123–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wen, Y.; Xue, Z.; Zhou, X.; Shi, D.; Hu, G.-H.; Xie, X. Novel micro-nano epoxy composites for electronic packaging application: Balance of thermal conductivity and processability. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 209, 108760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.; Kim, Y.-J.; Tak, S.-Y.; Park, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J.; Oh, C.H. Preparation of ultra-low CTE epoxy composite using the new alkoxysilyl-functionalized bisphenol A epoxy resin. Polymer 2018, 135, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, H.; Park, S.-Y.; Park, S.-J.; Kim, Y.-J. Preparation of low-CTE composite using new alkoxysilyl-functionalized bisphenol A novolac epoxy and its CTE enhancement mechanism. Polymer 2020, 207, 122916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, W.-B.; Hao, L.-F.; Jiao, W.-C.; Yang, F.; Wang, R.-G. Preparation of carbon nanotube/carbon fiber hybrid fiber by combining electrophoretic deposition and sizing process for enhancing interfacial strength in carbon fiber composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2013, 88, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.-H.; Liang, G.-Z.; Zhou, Z.-W.; Li, F. Structure and properties of UHMWPE fiber/carbon fiber hybrid composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 101, 1880–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchitra, M.; Renukappa, N.M. The thermal properties of glass fiber reinforced epoxy composites with and without fillers. Macromol. Symp. 2016, 361, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Guo, Y.; Douglas, J.F.; Xia, W. Understanding the role of cross-link density in the segmental dynamics and elastic properties of cross-linked thermosets. J. Chem. Phys. 2022, 157, 064901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Guo, Y.; Douglas, J.F.; Xia, W. Competing effects of cohesive energy and cross-link density on the segmental dynamics and mechanical properties of cross-linked polymers. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 9990–10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Nsengiyumva, W. Introduction and background of fiber-reinforced composite materials. In Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation of Fiber-Reinforced Composite Structures; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mao, J.; Qian, B.; Zhao, M. Progress in surface modification preparation, interface characterization and properties of continuous carbon fiber reinforced polymer matrix composites. Compos. Interfaces 2024, 31, 729–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lock, S.S.M.; Lau, K.K.; Shariff, A.M.; Yeong, Y.F.; Bustam, M.A. Computational insights on the role of film thickness on the physical properties of ultrathin polysulfone membranes. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 44376–44393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikasetsin, S.; Jung, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Kim, B.S.Y.; Seo, J.; Choi, J.; Bae, K.; Park, W. Observation of highly anisotropic thermal expansion of polymer films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 27166–27172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Dai, F.; Wang, M.; Chen, C.; Qian, G.; Yu, Y. Homopolyimides containing both benzimidazole and benzoxazole with high Tg and low coefficient of thermal expansion. J. Polym. Sci. 2021, 59, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shardakov, I.N.; Trufanov, A.N. Identification of the temperature dependence of the thermal expansion coefficient of polymers. Polymers 2021, 13, 3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinaldi, A.; Ferrara, M.; Piliaru, L.; Allegranza, C.; Nanni, F. Additive manufacturing of polyether ether ketone-based composites for space application: A mini-review. CEAS Space J. 2023, 15, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ree, M. High Performance Polyimides for Applications in Microelectronics and Flat Panel Displays. Macromol. Res. 2006, 14, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokaian, A. Thermal Expansion of Pipe-in-Pipe Systems. Mar. Struct. 2004, 17, 475–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, Ö.; Stewart, H.E.; O’Rourke, T.D. Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Polyethylene Pipes. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2007, 19, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarian, K.; Santhanam, S.; Wing, Z.N. Coefficient of Thermal Expansion of Particulate Composites with Ceramic Inclusions. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 17659–17665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guseva, O.; Lusti, H.R.; Gusev, A.A. Matching Thermal Expansion of Mica–Polymer Nanocomposites and Metals. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2004, 12, S101–S105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rădulescu, B.; Mihalache, A.M.; Hrițuc, A.; Rădulescu, M.; Slătineanu, L.; Munteanu, A.; Dodun, O.; Nagîț, G. Thermal Expansion of Plastics Used for 3D Printing. Polymers 2022, 14, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barra, G.; Guadagno, L.; Raimondo, M.; Santonicola, M.G.; Toto, E.; Vecchio Ciprioti, S. A Comprehensive Review on the Thermal Stability Assessment of Polymers and Composites for Aeronautics and Space Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmol, G. Automotive and Construction Applications of Fiber Reinforced Composites. In Fiber Reinforced Composites: Constituents, Compatibility, Perspectives and Applications; Joseph, K., Oksman, K., Gejo, G., Wilson, R., Appukuttan, S., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing (Elsevier): Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 785–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Li, J.; Yuan, Y.; Gao, C.; Cui, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Peng, C.; Wu, Z. A Review of the Polymer for Cryogenic Application: Methods, Mechanisms and Perspectives. Polymers 2021, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segerström, S.; Ruyter, I.E. Mechanical and Physical Properties of Carbon–Graphite Fiber-Reinforced Polymers Intended for Implant Suprastructures. Dent. Mater. 2007, 23, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Muralikrishnan, B.; Lee, V.; Rachakonda, P.; Sawyer, D.; Gleason, J. Methods to Calibrate a Three-Sphere Scale Bar for Laser Scanner Performance Evaluation per the ASTM E3125-17. Measurement 2020, 152, 107274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, X.-C.; He, M.-Z.; Li, L.-F.; Ye, X.-Y.; Li, J.-S. Photogrammetric Scale-Bar Measurement Method Based on Microscopic Image Aiming. Proc. SPIE 2012, 8417, 84170A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Muralikrishnan, B.; Lee, V.; Sawyer, D.; Icasio-Hernández, O. Improvised Long Test Lengths via Stitching Scale Bar Method: Performance Evaluation of Terrestrial Laser Scanners per ASTM E3125-17. J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 2020, 125, 125017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Lu, N.-G.; Dong, M.-L.; Yan, B.-X.; Wang, J. Simultaneous All-Parameters Calibration and Assessment of a Stereo Camera Pair Using a Scale Bar. Sensors 2018, 18, 3964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Anisotropy | Orthotropy (e.g., Fiber-Reinforced PCMs with a Regular Microstructure) | Isotropy (Homogeneous Materials, e.g., Amorphous Polymers) |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Elongation, mm |

|---|---|

| glass | 0.9 |

| concrete | 1.2 |

| copper, stainless steel | 1.7 |

| aluminum | 2.4 |

| polypropylene | 15 |

| polyethylene | 20 |

| CLTE Range (ppm/°C) | Materials |

|---|---|

| 0–10 | Non-polymeric materials: quarts glass; borosilicate glass; ceramics (e.g., SiC, Al2O3, dental/technical glass-ceramics); special metal alloys (e.g., Invar, Kovar), wood (longitudinal direction); concrete (up to 12–13 ppm/°C) Polymers: LCPs (along the macromolecular orientation) PCMs: carbon fiber filled ERs, highly silica-filled PCMs |

| 10–20 | Non-polymeric materials: cement; bone tissues; gypsum; engineered stones Polymers: high crosslink density PI; aromatic PAI PCMs: glass fiber filled ERs; mineral-filled PCMs |

| 20–100 | Non-polymeric materials: wood (transverse direction); plywood; hardboard; asphalt Polymers: LCPs (transverse to the macromolecular orientation); PS; PVC; ABS; PET (below Tg); PA6; PA66; PBT; PPO; PPA; PC; PPS; PSU; PES; PPSU; PEK; PEEK; PEKK; PEI; ERs; PFRs; BMIs; polyester resins PCMs: particulate-filled PCMs (low and medium filler content); wood–polymer composites |

| >100 | Non-polymeric materials: paraffin; waxes; oily solid products Polymers: PE; PP; PMMA; PET (above Tg); silicone resins PCMs: polymer–rubber composites; highly foamed polymer concretes; resin mortars; asphalt–polymer mixes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khina, A.G.; Bulkatov, D.P.; Storozhuk, I.P.; Sokolov, A.P. Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion of Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers 2025, 17, 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233097

Khina AG, Bulkatov DP, Storozhuk IP, Sokolov AP. Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion of Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers. 2025; 17(23):3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233097

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhina, Alexander G., Denis P. Bulkatov, Ivan P. Storozhuk, and Alexander P. Sokolov. 2025. "Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion of Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review" Polymers 17, no. 23: 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233097

APA StyleKhina, A. G., Bulkatov, D. P., Storozhuk, I. P., & Sokolov, A. P. (2025). Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion of Polymers and Polymer Composites: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers, 17(23), 3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17233097