1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of hypersonic vehicles has intensified focus on thermal protection, where heat management remains a critical bottleneck [

1]. Polymer nanocomposites with inorganic nanomaterial additives exhibit superior thermal resistance, flame resistance, chemical resistance, conductivity, and reduced permeability. Ongoing research emphasizes applications in rocket nozzle ablatives, thermo-oxidatively resistant carbon–carbon composites, and damage-tolerant epoxy matrices [

2]. Polymeric ablatives (PAs) are the most versatile thermal protection system (TPS) materials, with advances such as the Phenolic Impregnated Carbon Ablator (PICA) developed by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the modified version PICA-X developed by Space Exploration Technologies Corporation (SpaceX), with the latter offering improved ablation resistance at a one-order-of-magnitude lower cost [

3]. Ablative TPS materials, particularly polymeric systems, remain essential for propulsion and hypersonic protection, with their thermal response commonly assessed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), thermomechanical analysis (TMA), and differential thermal analysis (DTA), while oxy-acetylene torch (OAT) testing and simulated solid rocket motor (SRM) tests more accurately reproduce hyperthermal environments [

4].

TPS development must prioritize mass-efficient materials, accurate modeling and simulation, and advanced sensors to ensure optimal performance, reduce mission risks, and enable in-space damage detection and repair [

5]. Concerning advancements, the development of high-strength hollow microspheres (HMs) has made possible low-damage, low-density TPS materials with enhanced ablation resistance, addressing HM breakage during extrusion and achieving greater density reduction than previously reported, thereby improving SRM performance [

6]. To improve weight saving, dual-layer ablatives enhance TPS performance via customizable layering, with uniform composites as the foundation, supporting missions like Dragonfly [

7]. Emerging commercial and NASA missions demand low-cost, rapidly producible, and environmentally friendly ablative TPS, prompting the development of PICA-Flex, a hybrid blanket from the MERINO family intermingling carbon and phenolic fibers [

8]. Moreover, boron trioxide (B

2O

3)-reinforced polymer matrix composites (PMCs) enhanced char-layer antioxidation, reducing ablation by 48% and increasing residue and liquid-film content, with highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) formation improving TPS performance in varied SRM environments [

9].

Thermal protection system material development is validated via testing, such as thermal–fluid–ablation models showing that local thermal non-equilibria and radiation strongly affect responses based on pore sizes greater than 1 micrometer and porosity [

10], or by computational fluid dynamics (CFD), which is used to simulate the complex flow of hot gases and predict heat transfer during atmospheric entry [

11,

12]. A flame exposure apparatus, set up according to the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) E 285-80 standard and validated via CFD simulations of oxygen–acetylene combustion, accurately predicted heat flux and surface temperatures, providing a benchmark for TPS material testing [

13]. Two additional TPS classes combining a carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) layer with phenolic-based ablatives, cork, or carbon felt reinforced with 1–2 weight percentage nano-silicon carbide (nSiC) and joined by a ceramic adhesive, were oxy-butane (OTB)-tested. These tests showed that carbon felt reinforcement and nSiC doping improved thermal conductivity, reduced mass loss, and limited erosion via energy dissipation and silicon carbide (SiC) to silicon dioxide (SiO

2) oxidation, confirming high thermal resistance for aerospace applications [

14].

Five high-temperature thermoplastics—two polyetherimides (PEIs), two polyether ether ketones (PEEKs), and one polyether ketone ketone (PEKK)—were fabricated by fused filament fabrication (FFF) three-dimensional (3D) printing and characterized for ablation and thermal performance. Among them, PEKK exhibited the highest char yield (64 weight percent) and best residual mass under 100 W/cm

2 OAT and inductively coupled plasma (ICP) tests, while the PEIs exhibited the lowest flammability measured by microscale combustion calorimetry (MCC, heat release 408 J/g-K) and the PEEKs showed the highest thermal decomposition temperatures, confirming material-dependent intumescent behavior and porous char formation under rapid heating [

15]. The PEKK composites reinforced with 10 weight percentage carbon nanotubes (CNTs), carbon fibers (CFs), and glass fibers (GFs) were fabricated by FFF 3D printing and tested under TGA and OTB exposure. CNT–PEKK showed the highest char yield (69 weight percent), lowest mass loss, minimal swelling, and best thermal performance, while CFs and GFs increased effusivity but also swelling [

16]. Moreover, polyacrylonitrile carbon fiber (PAN-CF) carbon/phenolic composites (CPCs) were OAT-tested for in-plane and out-of-plane thermal diffusivity, showing agreement with reference materials MX-4926 and FM-5014 under high heating rates [

17].

For the development of the manufacturing process, additive manufacturing of concrete for TPS applications employed a traveling salesman problem (TSP)-based continuous print path with contour offset and sharp-turn removal, improving print quality, structural integrity, and reducing anisotropic strength, as validated through experimental and numerical evaluation of planar and topology-optimized designs [

18]. Additive manufacturing of ablative TPS was also demonstrated using a low-cost five-axis extrusion printer and a high-viscosity, 3D-printable composite, producing char yields comparable to legacy materials and enabling in situ deposition, scalable production, and reduced tile fabrication and assembly costs [

19].

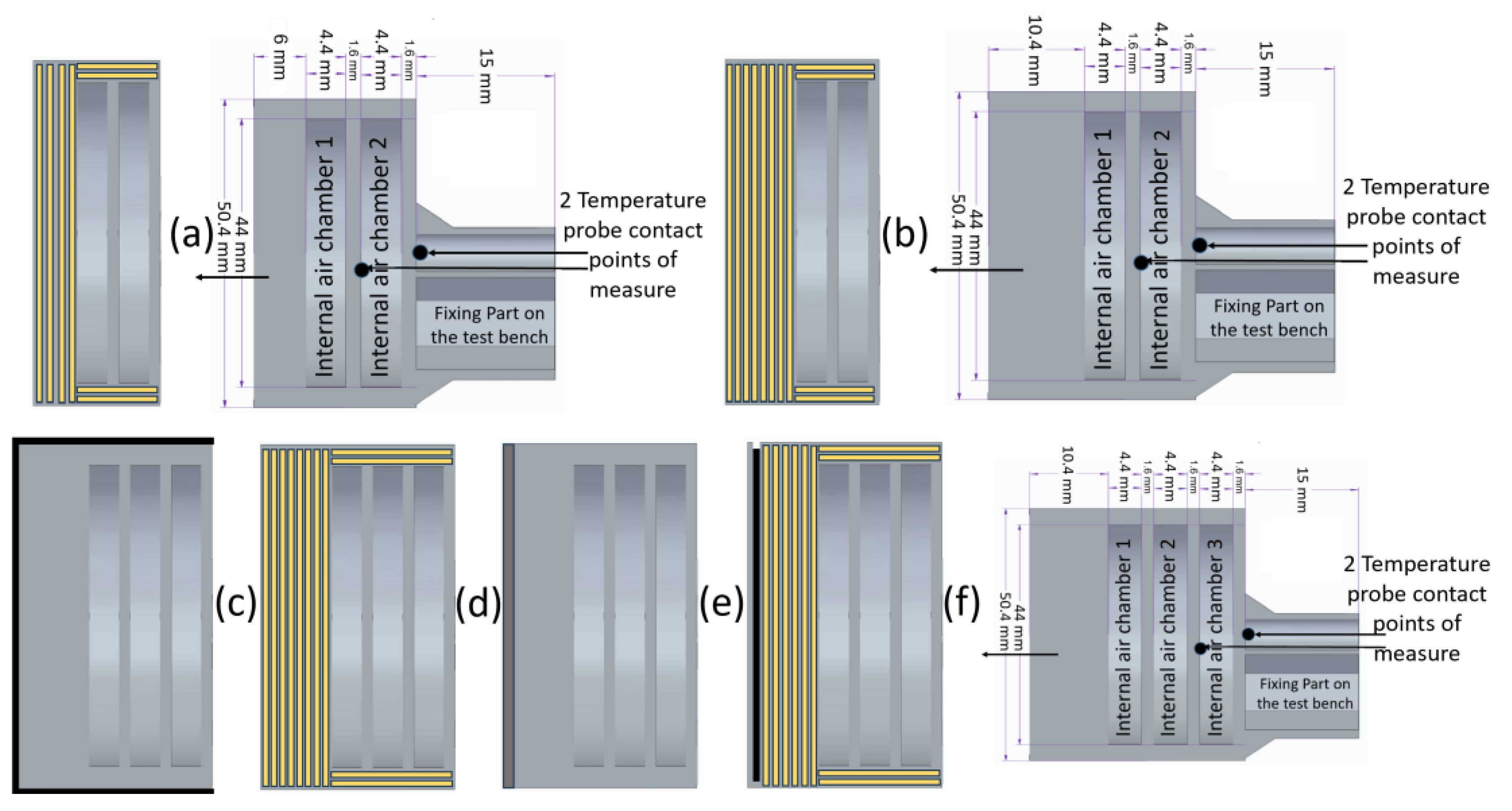

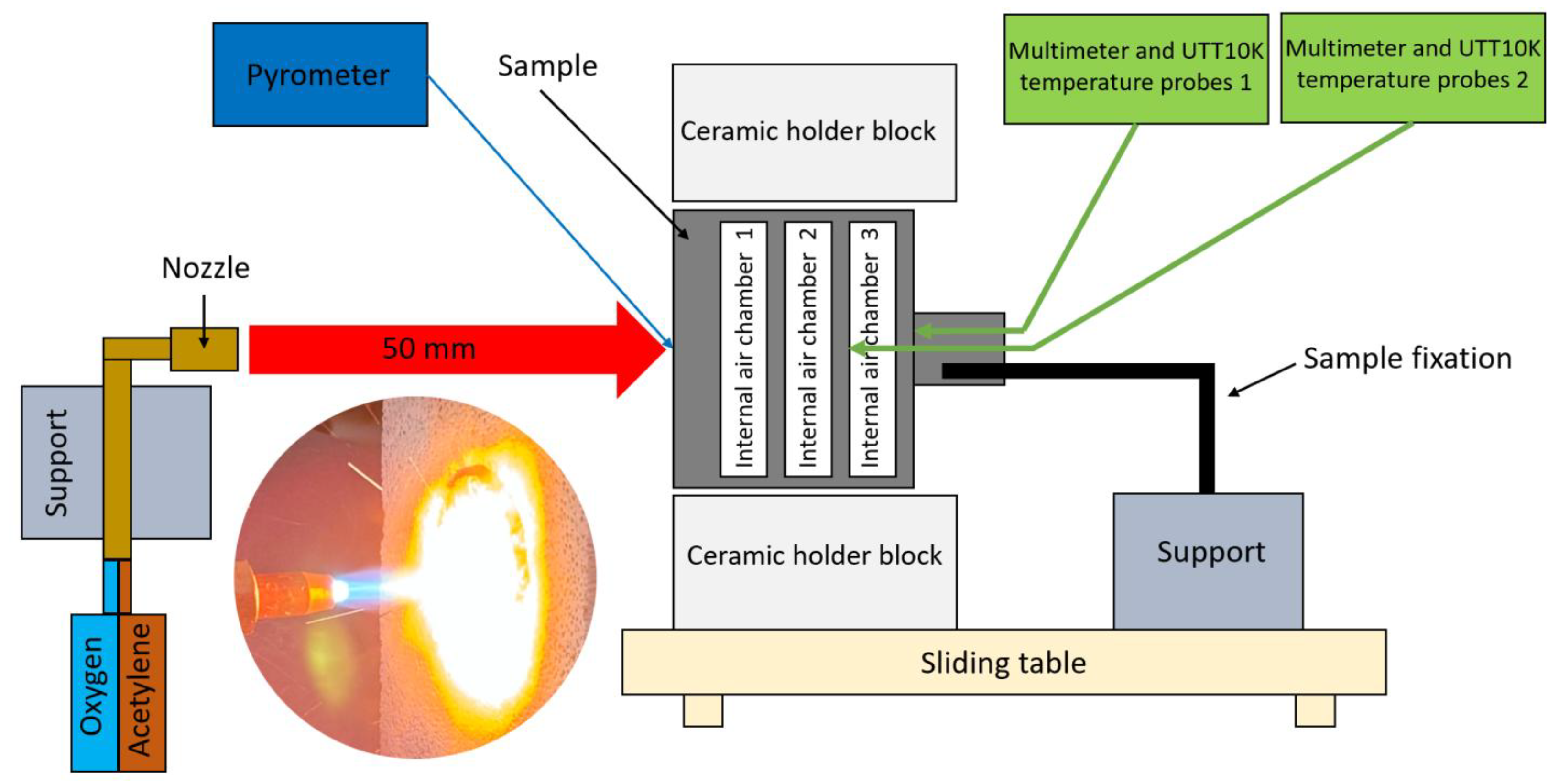

This study builds upon recent advancements in additive manufacturing of ablative thermal protection systems (TPSs), demonstrating that ceramic-coated and hybrid or continuous fiber-reinforced composites improved ablation resistance, while the incorporation of internal air chambers enhanced lightweight performance. The novelty of incorporating 3D-printed air chamber architectures effectively reduces thermal conductivity and convective heat transfer, enabling scalable, in situ fabrication while maintaining high char yield and structural integrity. These innovations distinguish the present work from previous studies and mark a significant advancement in the next generations of TPS design, bridging material innovation and advanced manufacturing strategies.

3. Results and Discussions

Following the Oxy-acetylene Test Bed (OTB) ablation tests, a comprehensive post-test analysis was conducted, which included visual inspection, morphological characterization, and metrological measurements of both weight and thickness. Weight measurements were performed with a Kern PLJ 510-3M (KERN & SOHN GmbH, Balingen, Germany) analytical balance, which provided a precision of ±0.001 g. Thickness measurements were taken using a Mitutoyo CD-P15P (Mitutoyo Corporation, Kawasaki, Japan) digital vernier caliper with a measuring range of 0–150 mm and an accuracy of 0.01 mm. These systematic measurements provided quantitative data for evaluating the material’s performance and the extent of degradation.

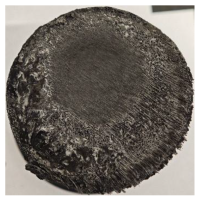

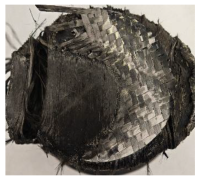

Table 2 depicts images of the specimens after oxy-acetylene torch (OTB) ablation testing. Some configurations developed a carbon-rich char layer, interspersed with dark-brown regions indicative of localized oxidation. Unlike conventional thermoset-based ablators, which form thick and cohesive protective char layers, the thermoplastic systems investigated here produced thinner and more fragile char. This behavior is attributed to the decomposition pathways of thermoplastics, which involve rapid pyrolysis and volatile release at relatively low temperatures, thereby limiting the accumulation of a dense insulating layer.

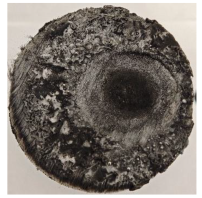

The hybridized configurations exhibited differentiated surface responses under ablation testing compared to the other configurations. Specimens modified with an external reinforcement CFRP layer (Hexply M49/42%/200T2X2/CHS-3K) preserved comparatively cleaner surfaces with less charring after exposure. Configuration 7, which incorporated a cured CFRP laminate disk embedded within a 2 mm slot at the flame-facing interface, demonstrated a similar protective effect, maintaining surface integrity aside from localized damage at the flame impingement zone. In contrast, Configuration 6, which integrated a 3 mm alumina (Al2O3) surface layer, exhibited accelerated degradation, with significant surface penetration and reduced structural preservation relative to the CFRP-modified counterparts. Across all hybridized specimens, material loss was concentrated at the region corresponding to the flame diameter, whereas peripheral areas remained largely unaffected. The results demonstrate the superior shielding capacity of CFRP-based modifications, although the internal structure of air chambers was still affected, while the alumina-filled configuration proved limited due to rapid erosion of the alumina–epoxy layer under high thermal flux and reduced stand-off distance.

Post-test analysis revealed that all Onyx FR-V0 specimens, whether reinforced or hybridized, developed a carbon-rich char layer after 60 s and 90 s of oxy-acetylene exposure. This layer acted as a transient thermal barrier by insulating and re-radiating heat, and dissipating energy through progressive erosion. Nonetheless, local detachment was observed in some specimens, while others exhibited stronger adhesion, likely due to liquid phase formation at elevated temperatures and re-solidification upon cooling. Reinforced specimens outperformed hybridized ones, forming denser, more stable char layers. This behavior is attributed to the oxidative degradation of Onyx FR-V0, where oxygen-induced carbonyl groups enhanced char cohesion in fiber-reinforced architectures.

According to

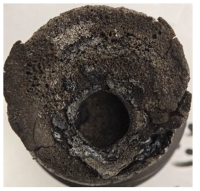

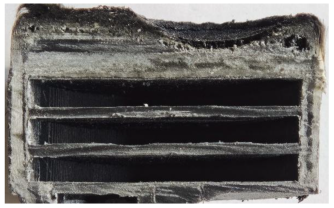

Table 3, Specimens 1 and 6 showed the most extensive damage under both exposure times, with structural deformation indicating failure. Configuration 1 experienced significant deformation leading to critical damage, primarily due to the thinner frontal wall and the limited reinforcement provided by only four continuous carbon fiber-reinforced rings in the frontal area.

Nevertheless, the char layers of both specimens were porous and fragile, detaching even after 60 s and leading to structural collapse. In contrast, other reinforced and hybridized specimens retained adherent char layers, preserving integrity.

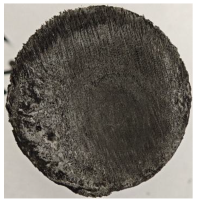

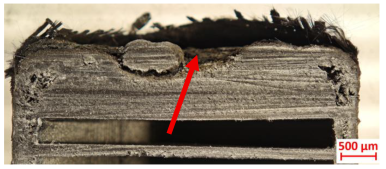

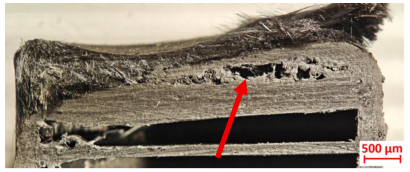

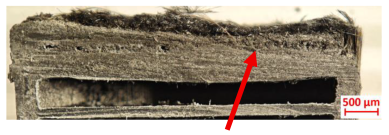

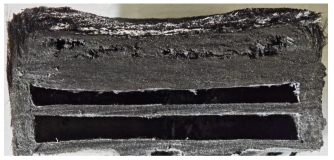

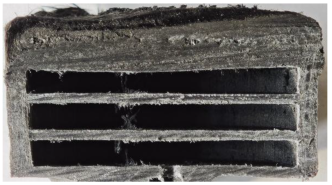

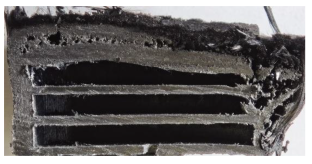

For Specimen 2.1 (10.4 mm frontal wall), the cross-section after testing showed ablation and thermo-oxidative degradation, with a rough surface, material loss, and exposed carbon fiber bundles due to matrix pyrolysis. Significant porosity was present, originating from both FFF process-induced voids and thermal-degradation gases. The longer exposure of Specimen 2.2 intensified ablation, reducing wall thickness and producing deeper erosion with extensive pits. The thermal front penetrated further, compromising the thin layer between air chambers and weakening insulation capacity.

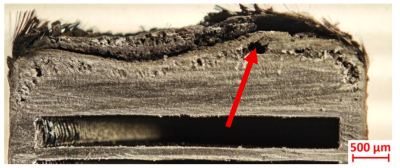

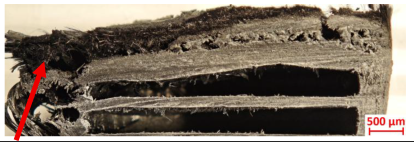

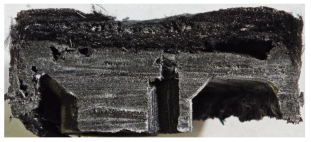

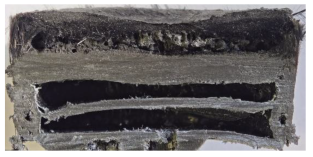

Across hybridized configurations, prolonged exposure consistently worsened degradation. Specimens 3.1 and 3.2 illustrate this trend; 3.1 (60 s) retained intact air chambers under a protective char layer with localized porosity, while 3.2 (90 s) exhibited accelerated ablation, reduced wall thickness, and thermal front propagation that compromised internal layers. Similarly, Specimens 7.1 and 7.2 shifted from controlled degradation to severe plastic deformation; 7.1 (60 s) pre-served geometry via a char layer formed by CCF and CFRP reinforcements, whereas 7.2 (90 s) showed a collapse of air chambers, extensive deformation, and dislodgement of CCF reinforcements, indicating a loss of structural capacity.

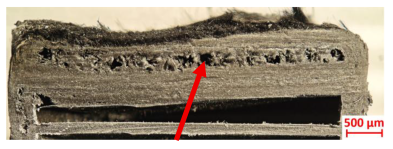

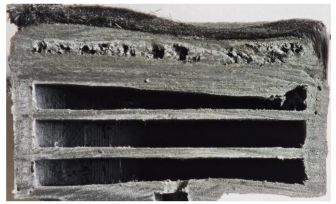

Specimens 4.1 and 4.2 further emphasize exposure duration effects; 4.1 (60 s) showed early degradation with moderate roughness and incipient char while maintaining integrity, whereas 4.2 (90 s) displayed severe material loss, wall thinning, deeper erosion, and the degradation of internal structures. Similarly, Specimens 5.1 and 5.2 highlight this progression; 5.1 (60 s) remained structurally sound with only initial surface degradation, while 5.2 (90 s) underwent significant ablative thinning, extensive porosity, and thermal front penetration into the core. Furthermore, in contrast to Probe 4.1, which was reinforced with continuous carbon fiber, the degradation observed in Probe 5.2, which was reinforced with continuous glass fiber has advanced to such an extent that the underlying onyx layer becomes distinctly visible.

When comparing Configurations 1 and 2, integrating only a two-air-chamber design, it is evident that the structural integrity of Specimens 1.1 and 1.2 was significantly compromised. Although, analyzing exclusively the surface degradation after 60 s of exposure, Configuration 2 seems more affected than Configuration 1; when examining the cross-sections, it is evident that Configuration 1 is structurally damaged. Likewise, when increasing the exposure time to 90 s, Configuration 1 (Sample 1.2) is clearly more affected by the damage being localized in a narrow region in the center of the exposed surface, the area directly subjected to the flame, and this is obvious when investigating both surface and section views. Specimens 1.1 and 1.2 exhibited major deformation after 60 s, followed by the collapse of the frontal wall and the overall structure after 90 s. This behavior is primarily attributed to the thinner frontal wall (6 mm) and the presence of only four CCF-F (continuous carbon fiber-reinforced) rings in the frontal wall area. In contrast, Configuration 2 featured a thicker frontal wall (10.4 mm) and eight CCF-F reinforcement rings, which provided greater resistance. However, it is important to note that the CCF-F-reinforced radial wall area in both configurations maintained sufficient structural integrity during the first 60 s of exposure. Thus, the degradation began at the center of the exposed surface, in the area directly subjected to the flame, eventually leading to structural failure after 90 s. Consequentially, a two-air chamber architecture will ensure a decrease in the overall system mass and can provide the necessary thermal conductivity reduction by limiting direct heat transfer pathways but only if integrated in a continuous reinforced structure in both frontal and radial wall areas to benefit from the anisotropic thermal conductivity of the fibers to distribute heat preferentially along aligned directions, thus mitigating localized degradation, as in the case of Configuration 2.

Configuration 2 showed the best performance, with thicker frontal walls and more CCF-F reinforcement preserving structural integrity under thermal load. Configuration 1 failed after 90 s, while hybridized three-air-chamber designs degraded progressively, with partial char protection at 60 s but significant ablation at 90 s. In all probes from

Table 3, internal air chamber structures remained intact, though minor deformations occurred, underscoring the role of wall thickness and continuous reinforcement.

Following the removal of the char layer by brushing the surface, a detailed analysis of the thickness change rate, thickness, and mass loss was conducted to quantify the material’s ablative performance. Thickness change rate is a key indicator of thermal protection duration, and it was calculated by dividing the thickness loss by the exposure time. As in Allcorn et al. [

23], the thickness after testing was defined as the thickness of the post-test virgin material. Consequently, the recession value quantifies the progression of the reaction front into the virgin material, excluding the residual char layer. As is desired, low recession values signify superior thermal protection.

Table 4 illustrates the results of the thickness change rates and provides cross-section views of all tested specimens.

Post-test analysis of the probes revealed the thickness change rate, which is a key metric for ablative performance, directly correlated with the extent of material degradation. The most significant thickness change rates were observed in Probes 1.1, 1.2, and 6.1, which experienced failure. In contrast, all other configurations demonstrated a more favorable performance, and with Probes 5.1 and 5.2 exhibiting the lowest thickness change rates, indicating superior thermal protection and structural integrity. The positive thickness change rates observed for Probes 2.2 and 4.1 are indicative of material buildup on the surface. This phenomenon is commonly attributed to the formation and densification of an expanded char layer, which projects beyond the original specimen plane.

The data confirms a direct relationship between increased thermal exposure duration and the extent of material loss. For instance, the transition from a 60 s to a 90 s exposure in most configurations led to a significant acceleration in the rate of ablative material removal. The most severe degradation was characterized by a profound increase in frontal wall thinning, deeper surface erosion, and the propagation of the thermal front into the internal structure, which in some cases compromised the internal structures of the air chambers. This highlights the critical role of exposure duration in determining the long-term effectiveness of the material’s thermal protection system.

Following the analysis of thickness change rates, a more direct quantification of ablative performance is the total thickness loss. This metric, illustrated in the subsequent chart (

Figure 3), shows the absolute reduction in material thickness for each tested specimen. Unlike the thickness change rate, which is an averaged value, thickness loss directly represents the total physical degradation, offering a clear visual and quantitative comparison of how effectively each configuration resisted the thermal load and protected its structural integrity.

The analysis of thickness change data reveals significant variations in the ablative performance of the tested probes. Probes 3 and 5 experienced the most substantial thickness change, with Probe 5 losing over 50% of its thickness in the 60 s test and more than 70% in the 90 s test. This indicates considerable material erosion and a failure to maintain structural integrity under extended thermal load. In contrast, Probes 2 and 4 demonstrated a markedly different trend. Probe 2 showed minimal thickness change across both exposure times, while Probe 4 exhibited a positive thickness change after 60 s. The latter suggests a swelling effect attributed to the formation of a protective char layer, which indicates superior thermal resistance and effective mitigation of material recession.

The weight loss data (

Figure 4) generally corroborates the trends observed in thickness change. Probes 1 and 6 displayed the highest weight loss percentages, signifying extensive mass ablation and material consumption, consistent with their overall structural failure. However, a notable discrepancy was observed in Probe 5, which, despite its significant thickness loss, showed one of the lowest weight loss percentages, particularly after the 60 s exposure. This apparent contradiction suggests a degradation mechanism distinct from simple mass ablation, where a portion of the material is sacrificed to form a lightweight, thermally insulating char layer.

Configurations 4, 5, and 3, all integrating a three-air-chamber design, showed the lower weight loss percentages, followed closely by 2 and 7. This trend is potentially due to CFRP protective layer that, however, once penetrated, left the unreinforced structure exposed due to the high thermal flux leading to accelerated degradation, as in the case of Configuration 3. Configurations 4 and 5 join the same structural design, the difference consisting in the continuous reinforcement phase-type carbon and, respectively, glass. Their lower weight loss percentages indicate an ablation protection provided by reinforcement phase primarily in the frontal and then in the radial regions, while the anisotropy of these composite structures promoted heat dissipation along fiber directions, limiting thermal penetration into the bulk and preventing excessive surface heating. Configuration 2, with two air chambers integrated into its internal structure, exhibits slightly higher weight loss percentages when compared to configurations discussed above (3, 4, and 5), which feature three-air-chamber designs. This indicated that a two-air-chamber design can sustain high thermal flux levels, if its TPS structure integrates both a thick frontal wall and high continuous reinforcement (eight carbon rings), which provide greater resistance. By contrast, Configuration 7, with a three-air-chamber design, displays significantly higher weight loss percentages when compared to the other tested configurations (except for Configuration 6), and this is due in all likelihood to the flame’s lack of centration and accelerated degradation of the radial wall, with the surface protective CFRP laminate being partially removed from the surface.

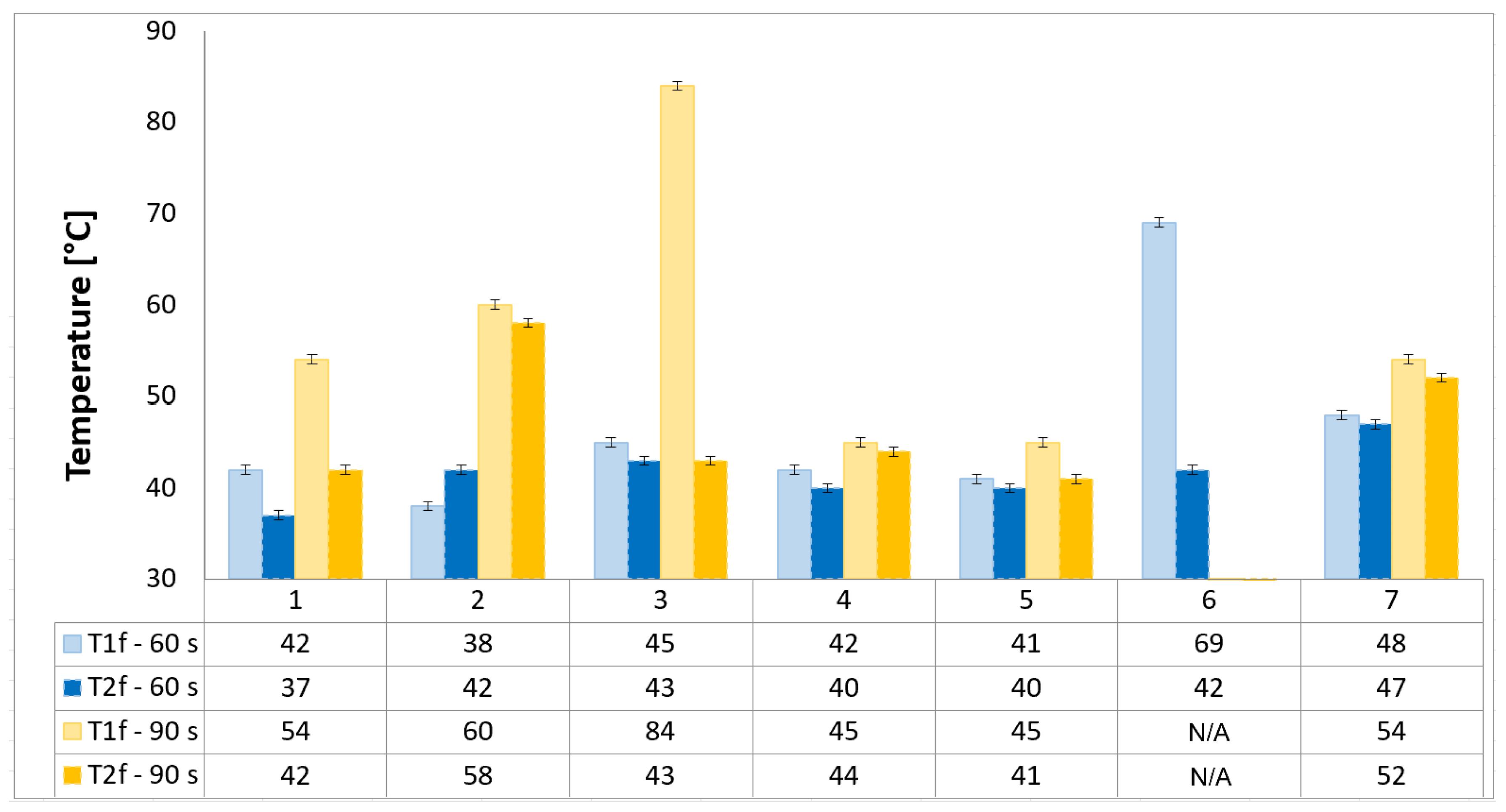

The temperature chart (

Figure 5) provides critical insights into the probes’ thermal insulation capabilities. From this, it can be generally observed that the temperature values measured at both locations remain significantly lower than the maximum allowable TPS back-face temperature of 180 °C, thereby ensuring that the spacecraft and its components remained within design safety margins.

Lower temperatures on the back face of the probe (T1f and T2f) are desirable, as they indicate effective thermal protection. Probe 6 shows an extremely high temperature reading on its back face at the 60 s mark (69 °C). Probe 3 demonstrates a significant increase in temperature at the back face with this, for the 90 s exposure, jumping to 84 °C. This suggests that while it may perform well in shorter tests, its long-term insulating capacity is compromised.

Conversely, Probes 4, 5, and 7 maintain relatively low back-face temperatures even during the 90 s exposure, all staying below 45 °C. This indicates that these configurations are highly effective at preventing heat from propagating through the material, despite varying degrees of thickness and weight loss. Probe 5, in particular, shows remarkable thermal insulation performance, maintaining a low back-face temperature despite its significant thickness loss. This suggests that its degradation mechanism results in a highly insulative, porous char layer.

Configurations 2, 4, and 5 are the most promising TPS designs, as their continuous reinforcement in their frontal and radial regions ensures ablation resistance and reduced back-face temperatures through anisotropic in-plane heat conduction; among them, Configurations 4 and 5, identical in design but reinforced with carbon and glass, respectively, exhibit the lowest weight loss and thermal loads, while Configuration 2, with thick reinforced walls, further demonstrates ablation resistance and highlights the potential of a two-air-chamber architecture to decrease system mass and enhance insulation, provided reinforcement continuity enables anisotropic redistribution of thermal loads and mitigates localized degradation.