Directed Evolution of Xylanase from Dickeya dadantii DCE-01 with Improved Enzymatic Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

2.1.2. Chemicals and Media

2.2. Methods

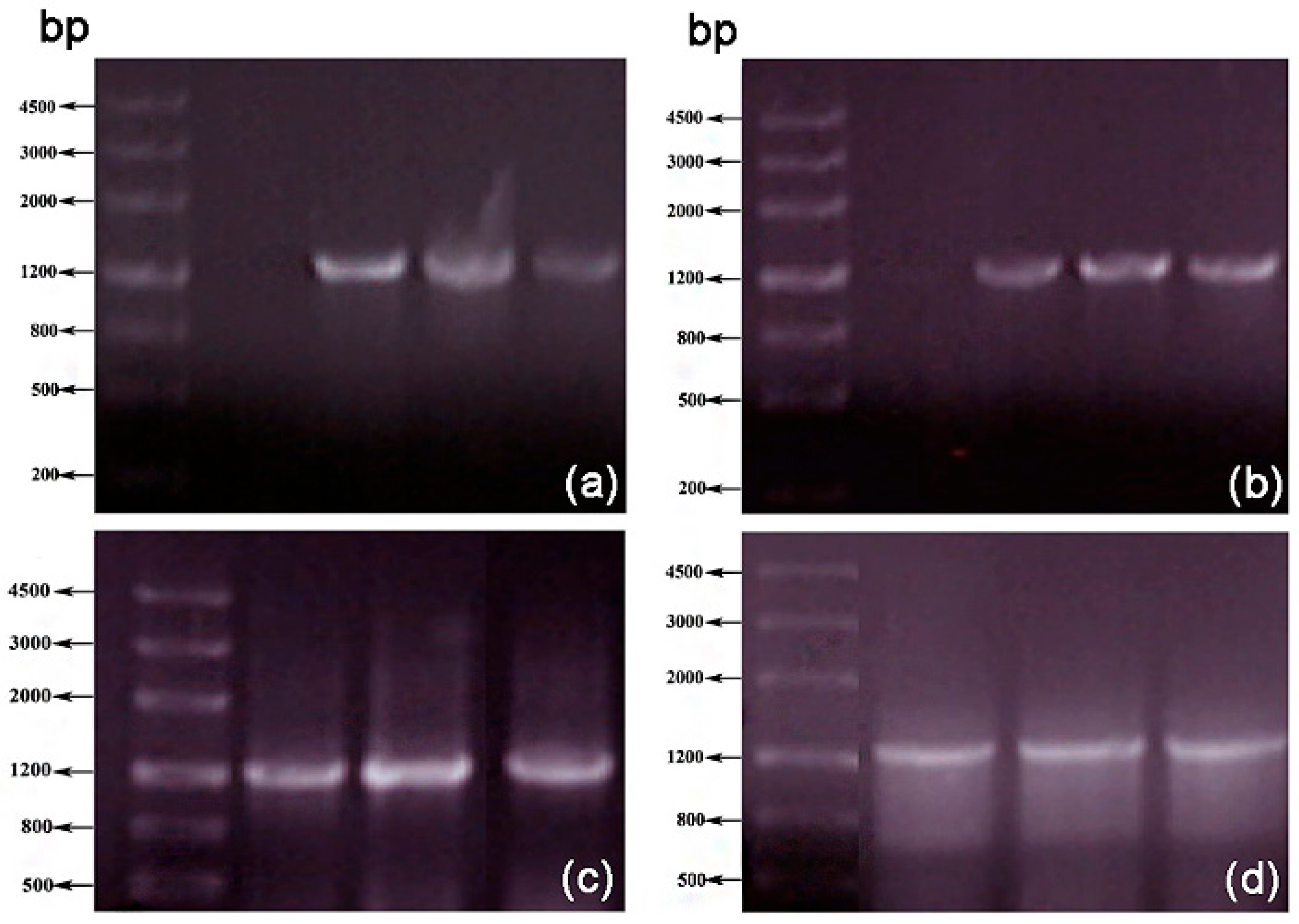

2.2.1. Construction of the Mutant Library

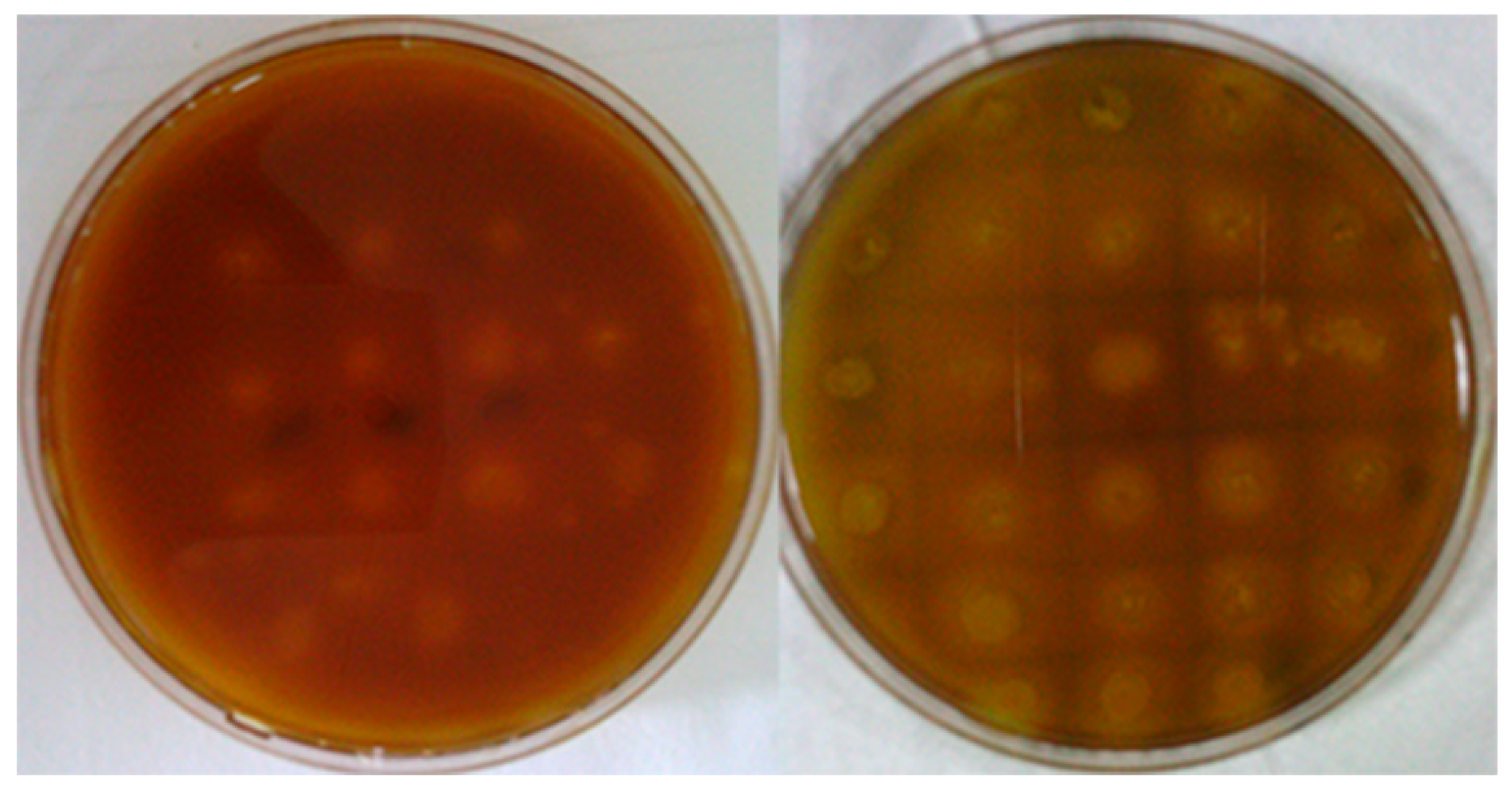

2.2.2. Screening of Mutant Strains

2.2.3. SDS-PAGE Analysis

2.2.4. Determination of Xylanase Activity of Mutant Strains

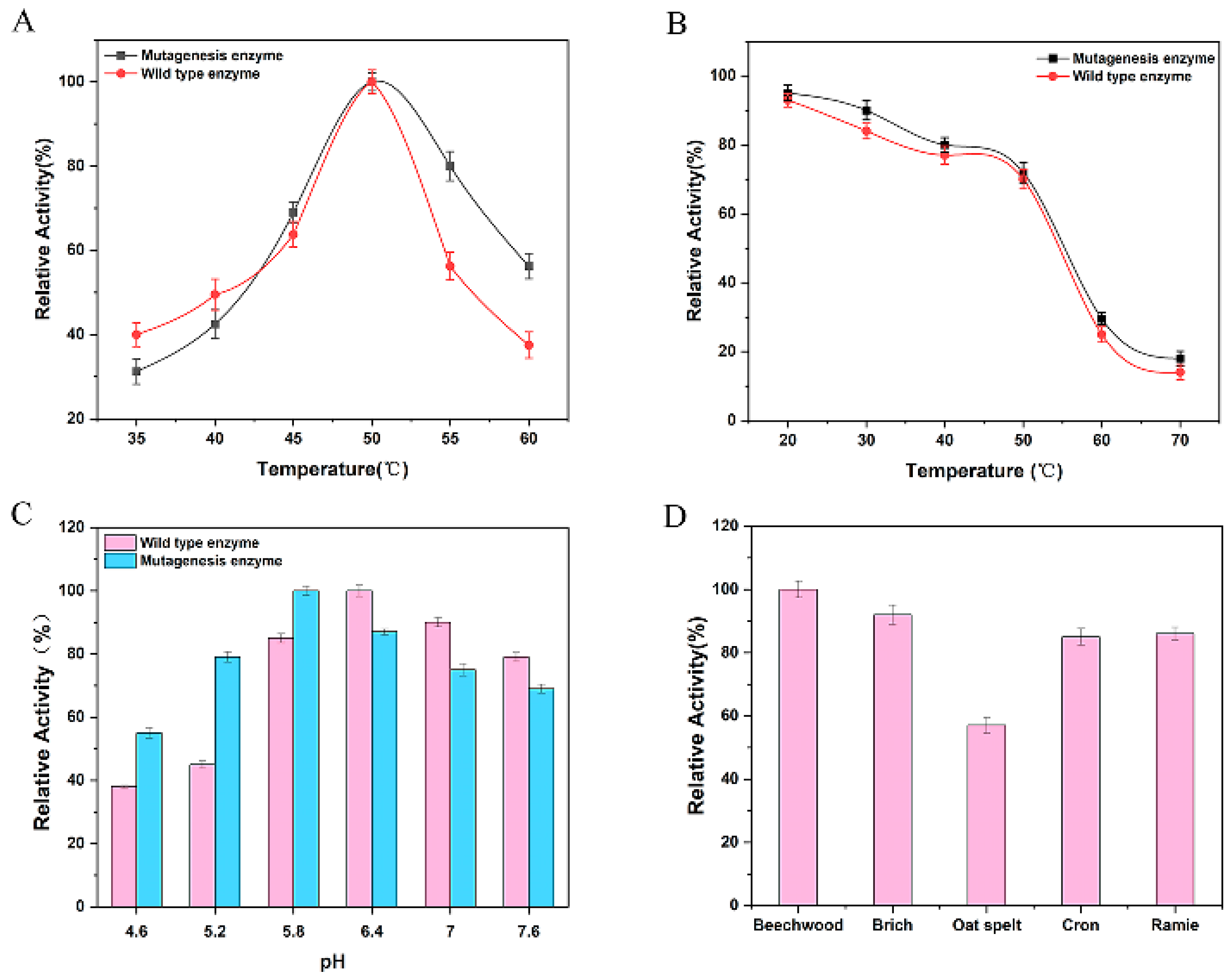

2.2.5. Temperature and Optimal pH of Mutant Xyn-ep

2.2.6. Thermal Stability of Mutated Xyn-ep

2.2.7. Substrate Specificity of Mutant Xyn-ep

2.2.8. Structural Analysis of Xyn-ep

2.2.9. The Degumming Performance of Mutant Strains on Ramie

3. Results and Discussion

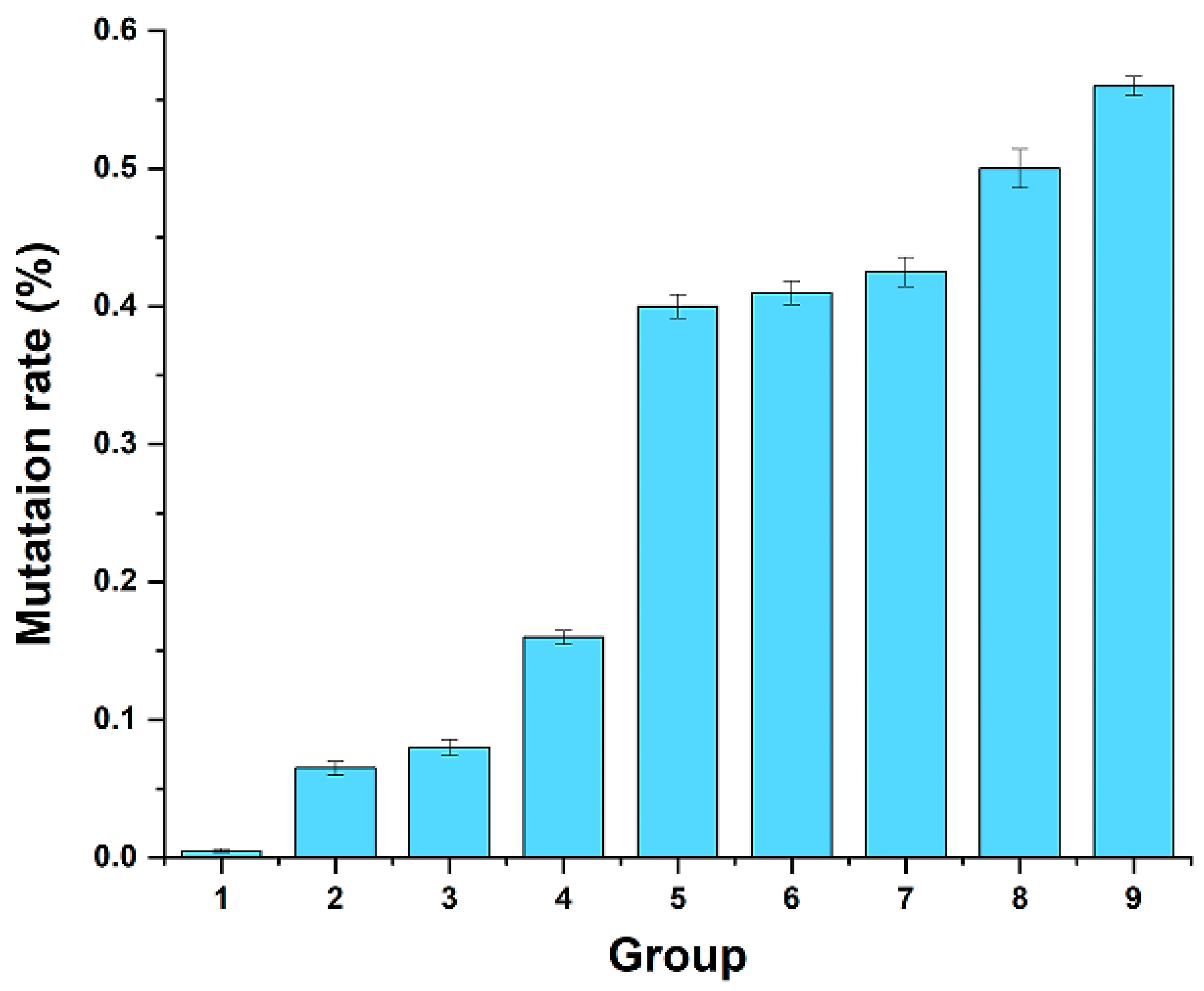

3.1. Error-Prone PCR Mutagenesis

3.2. Analysis of Enzymatic Properties of Mutant Strains

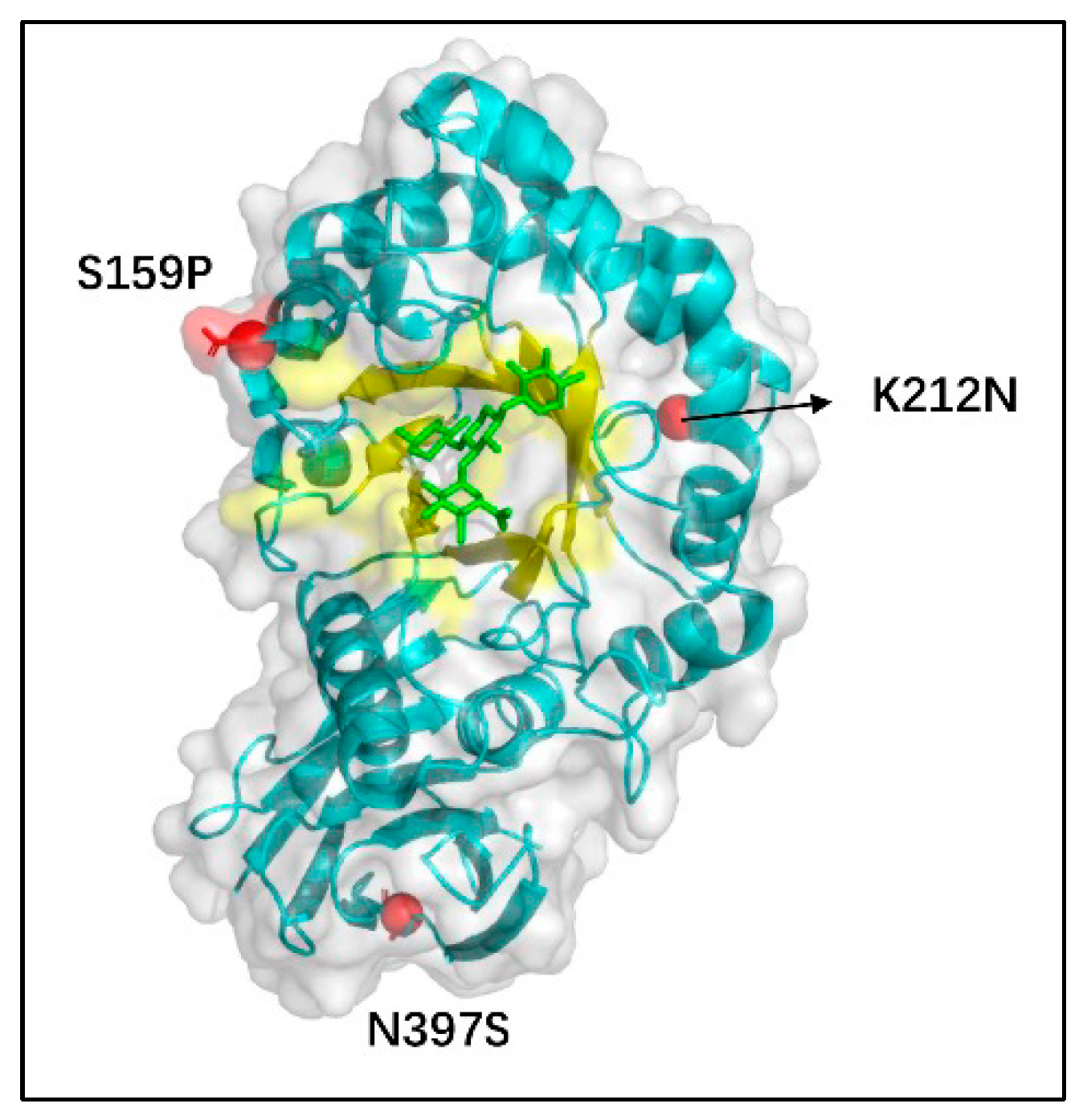

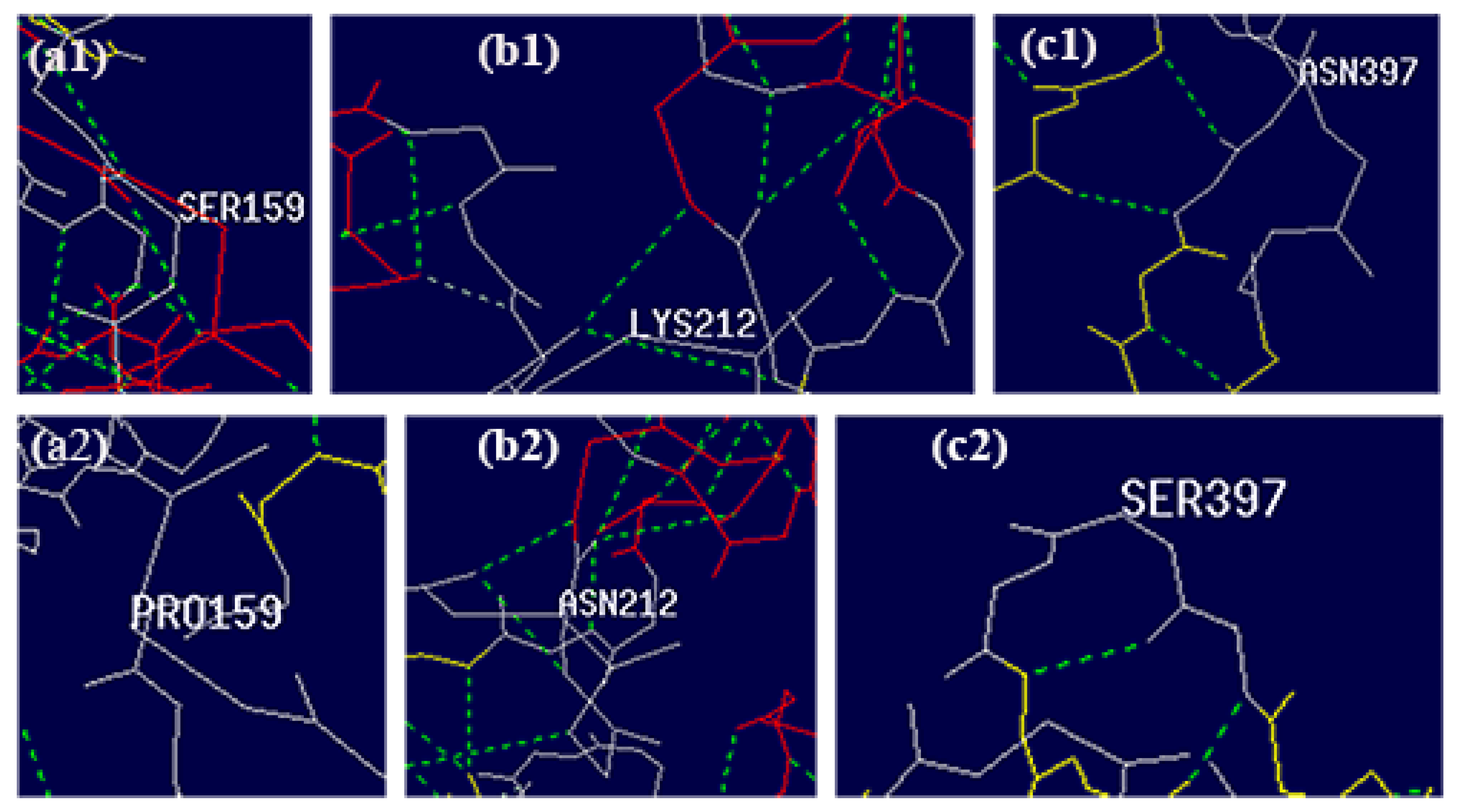

3.3. Structural Analysis of Mutated Enzymes

3.4. Effect of the Mutant Xylanase on Ramie Degumming

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chaudhari, A.A.; Sharma, A.M.; Rastogi, L.; Dewangan, B.P.; Sharma, R.; Singh, D.; Sah, R.K.; Das, S.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Mellerowicz, E.J.; et al. Modifying lignin composition and xylan o-acetylation induces changes in cell wall composition, extractability, and digestibility. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limayem, A.; Ricke, S.C. Lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol production: Current perspectives, potential issues and future prospects. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012, 38, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Q.; Kazachenko, A.X.Z. Crystallization and water cast film formability of birchwood xylans. Cellulose 2023, 30, 4623–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kormelink, F.J.M.; Voragen, A.G.J. Degradation of different glucuronoarabinoxylans by a combination of purified xylan-degrading enzymes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1993, 38, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abena, T.; Simachew, A. A review on xylanase sources, classification, mode of action, fermentation processes, and applications as a promising biocatalyst. BioTechnologia 2024, 105, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, T.; Gerday, C.; Feller, G. Xylanases, xylanase families and extremophilic xylanases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, V.; Golaconda, R.H.; Drula, E.; Coutinho, P.M.; Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbarasans Janis, J.; Paloheimo, M.; Laitaoja, M.; Vuolanto, M.; KarimäkI, J.; Vainiotalo, P.; Leisola, M.; Turunen, O. Effect of glycosylation and additional domains on the thermostability of a family 10 xylanase produced by Thermopolyspora flexuosa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 356–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, G.; Berrin, J.G.; Beaugrand, J. GH11 xylanases: Structure/function/properties relationships and applications. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 56–592. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Lin, M.; Yan, Y.; Jiang, S.; Dai, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, J. Identification of a novel glycoside hydrolase family 8 xylanase from Deinococcus geothermalis and its application at low temperatures. Arch. Microbiol. 2024, 206, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puchart, V.; Šuchová, K.; Biely, P. Xylanases of glycoside hydrolase family 30-an overview. Biotechnol. Adv. 2021, 47, 107704. [Google Scholar]

- Nirantar, S. Directed evolution methods for enzyme engineering. Molecules 2021, 26, 5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punekar, N.S. Exploiting Enzymes: Technology and Applications. In ENZYMES: Catalysis, Kinetics and Mechanisms; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 501–523. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahimi Fana, S.; Fazaeli, A.; Aminian, M. Directed evolution of cholesterol oxidase with improved thermostability using error-prone PCR. Biotechnol. Lett. 2023, 45, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, L.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, G. Improving the specific activity and pH stability of xylanase XynHBN188A by directed evolution. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2019, 6, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, J.; Turunen, O.; Xiong, H. High-temperature behavior of hyperthermostable Thermotoga maritima xylanase XYN10B after designed and evolved mutations. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 106, 2017–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.K.; Liu, J.Z. Enhancing catalytic activity of a xylanase retrieved from a fosmid library of rumen microbiota in hu sheep by directed evolution. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2014, 13, 538–544. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q.; Gao, M.; Cheng, L.; Feng, X.; Zheng, K.; Peng, Z.; Peng, Y.; Duan, S. Genomic scanning and extracellular proteomic analysis of Dickeya dadantii DCE-01 reveal its excellent performance on ramie degumming. Fibers Polym. 2023, 24, 1517–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, L.; Duan, S.; Feng, X.; Zheng, K.; Cheng, Y.; Zeng, J. A novel endo-β-1,4-xylanase GH30 from Dickeya dadantii DCE-01: Clone, expression, characterization, and ramie biological degumming function. Text. Res. J. 2019, 89, 463–472. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.S.; Jeong, G.R.; Bae, C.H.; Yeo, J.-H.; Chi, W.-J. Identification and Characterization of an Agarase- and Xylanse-producing Catenovulum jejuensis A28-5 fron Coastal Seawater of Jeju Island, Korea. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett. 2017, 45, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Echan, L.A.; Speicher, D.W. Protein Detection in Gels Using Fixation. Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. 2002, 29, 10.5.1–10.5.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.L. Use of dinitrosalicylic acid reagent for determination of reducing sugar. Anal. Chem. 1959, 31, 426–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhang, L.; Cai, W.; Deng, S.; Zhang, H.; Wu, L.; Li, H.; Liu, H. Purification and characterization of the low molecular weight xylanase from Bacillus cereus L-1. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2023, 54, 2951–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Feng, X.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, K.; Yi, L.; Duan, S.; Cheng, L. Improvement on Thermostability of Pectate Lyase and Its Potential Application to Ramie Degumming. Polymers 2022, 14, 2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; He, C.; Guo, J.; Yuan, L. Improvement of the catalytic activity of Thermoacidophilic sp. pullulan hydrolase type III by error-prone PCR technology. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2022, 58, 277–285. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, J.; Yang, H.; Shao, Y.; Li, L.; Sun, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, Y.; Xin, Z. Enhancing the activity and thermal stability of a phthalate-degrading hydrolase by random mutagenesis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021, 209, 111795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.T.; Sang, J.C.; Ying, T.W.; Sun, T.; Liu, H.; Yue, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Dai, Y.; Lu, F.; et al. Rational design of a Yarrowia lipolytica derived lipase for improved thermostability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 137, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuchner, O.; Arnold, F.H. Directed evolution of enzyme catalysts. Trends Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johannes, T.W.; Zhao, H.M. Directed evolution of enzymes and biosynthetic pathways. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, D.E.; Singh, S.; Permaul, K. Error-prone PCR of a fungal xylanase for improvement of its alkaline and thermal stability. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 293, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherry, J.R.; Lamsa, M.H.; Schneider, P.; Vind, J.; Svendsen, A.; Jones, A.; Pedersen, A.H. Directed evolution of a fungal peroxidase. Nat. Biotechnol. 1999, 17, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.S.; Roccatano, D.; Zacharias, M.; Schwaneberg, U. A statistical analysis of random mutagenesis methods used for directed protein evolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 355, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trevizano, L.M.; Ventorim, R.Z.; de Rezende, S.T.; Junior, F.P.S.; Guimarães, V.M. Thermostability improvement of Orpinomyces sp. xylanase by directed evolution. J. Mol. Catal. B-Enzym. 2012, 81, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirumamilla, R.R.; Muralidhar, R.; Marchant, R.; Nigam, P. Improving the quality of industrially important enzymes by directed evolution. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2001, 224, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrou, N.E. Random mutagenesis methods for in-vitro directed enzyme evolution. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2010, 11, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.X.; Liu, P.; Tan, Z.J.; Zhao, W.; Gao, J.; Gu, Q.; Ma, H.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L. Complete Depolymerization of PET Wastes by an Evolved PET Hydrolase from Di-rected Evolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 135, e202218390. [Google Scholar]

- Voigt, C.A.; Mayo, S.L.; Arnold, F.H.; Wang, Z.G. Computational method to reduce the search space for directed protein evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3778–3783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mg2+ | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn2+ | |||||

| 0.2 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 10 | |

| 0.3 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 11 | |

| 0.4 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | |

| Negative Control | Pectinase Pretreatment | Pectinase + Wild Type Xyn | Pectinase + Mutant Xyn-ep | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reducing sugar content (mg/mL) | 0.003 | 0.512 | 0.116 | 0.149 |

| Weight loss rates (%) | 4.77 | 10.89 | 15.72 | 19.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, R.; Shi, K.; Zheng, K.; Yang, Q.; Xi, G.; Duan, S.; Cheng, L. Directed Evolution of Xylanase from Dickeya dadantii DCE-01 with Improved Enzymatic Activity. Polymers 2025, 17, 2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17192650

Wang R, Shi K, Zheng K, Yang Q, Xi G, Duan S, Cheng L. Directed Evolution of Xylanase from Dickeya dadantii DCE-01 with Improved Enzymatic Activity. Polymers. 2025; 17(19):2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17192650

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ruijun, Ke Shi, Ke Zheng, Qi Yang, Guoguo Xi, Shengwen Duan, and Lifeng Cheng. 2025. "Directed Evolution of Xylanase from Dickeya dadantii DCE-01 with Improved Enzymatic Activity" Polymers 17, no. 19: 2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17192650

APA StyleWang, R., Shi, K., Zheng, K., Yang, Q., Xi, G., Duan, S., & Cheng, L. (2025). Directed Evolution of Xylanase from Dickeya dadantii DCE-01 with Improved Enzymatic Activity. Polymers, 17(19), 2650. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17192650