Preparation and Properties of Novel Crosslinked Polyphosphazene-Aromatic Ethers Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Microspheres

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Characterization

2.3. Synthesis

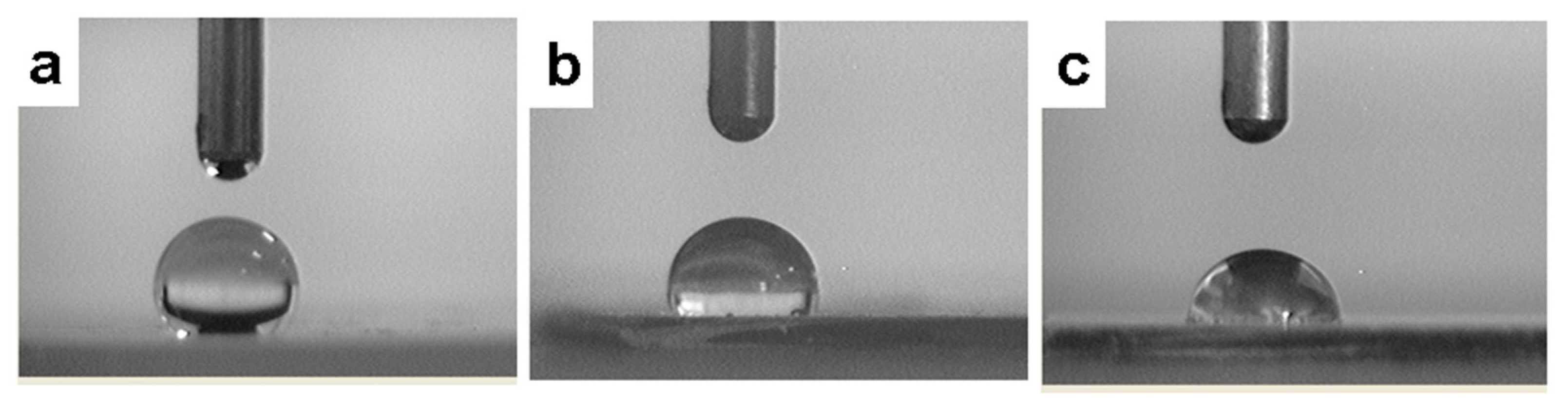

2.4. Film Preparation for CA Measurement

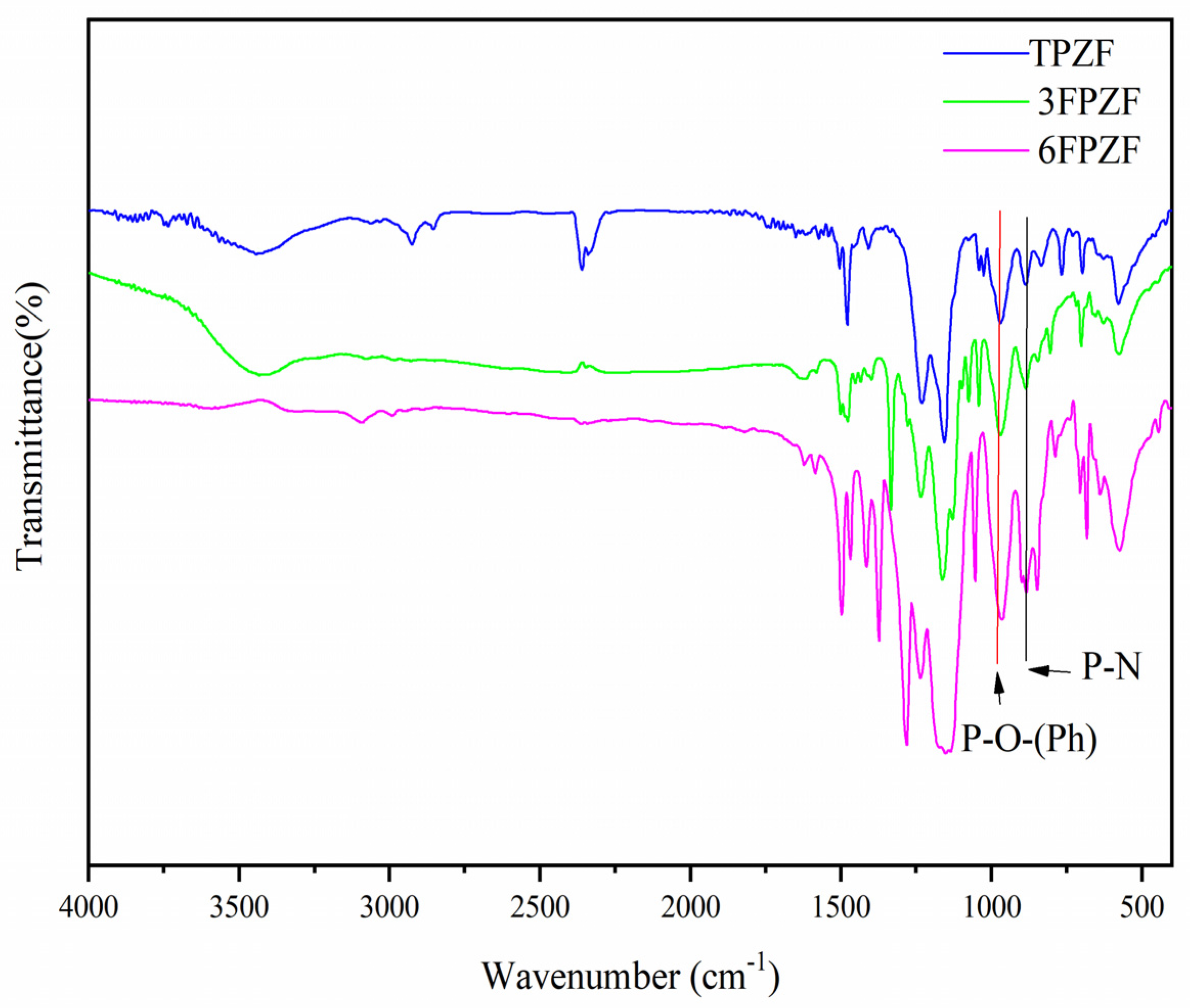

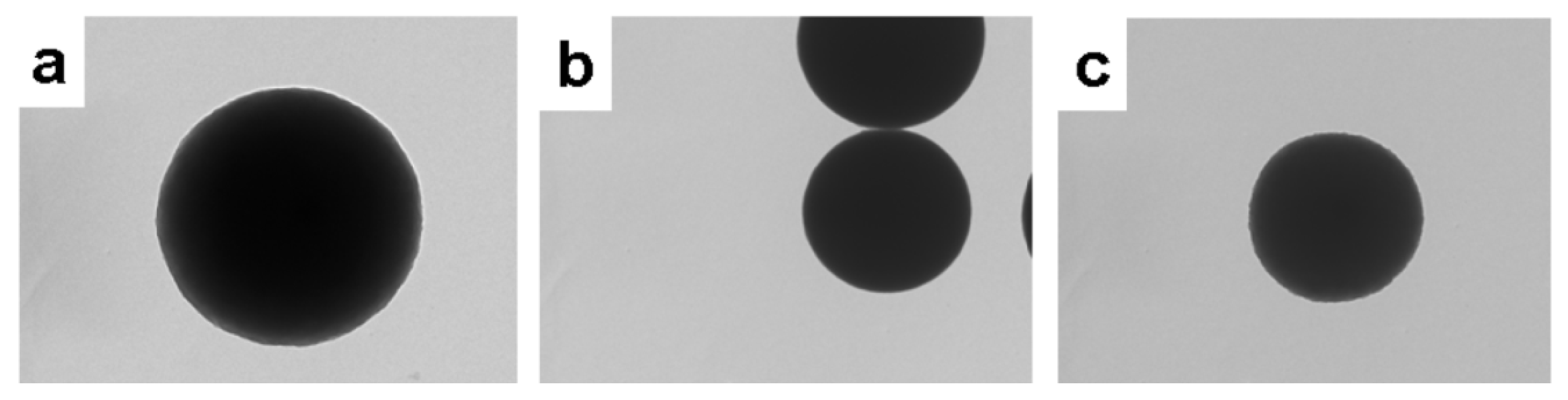

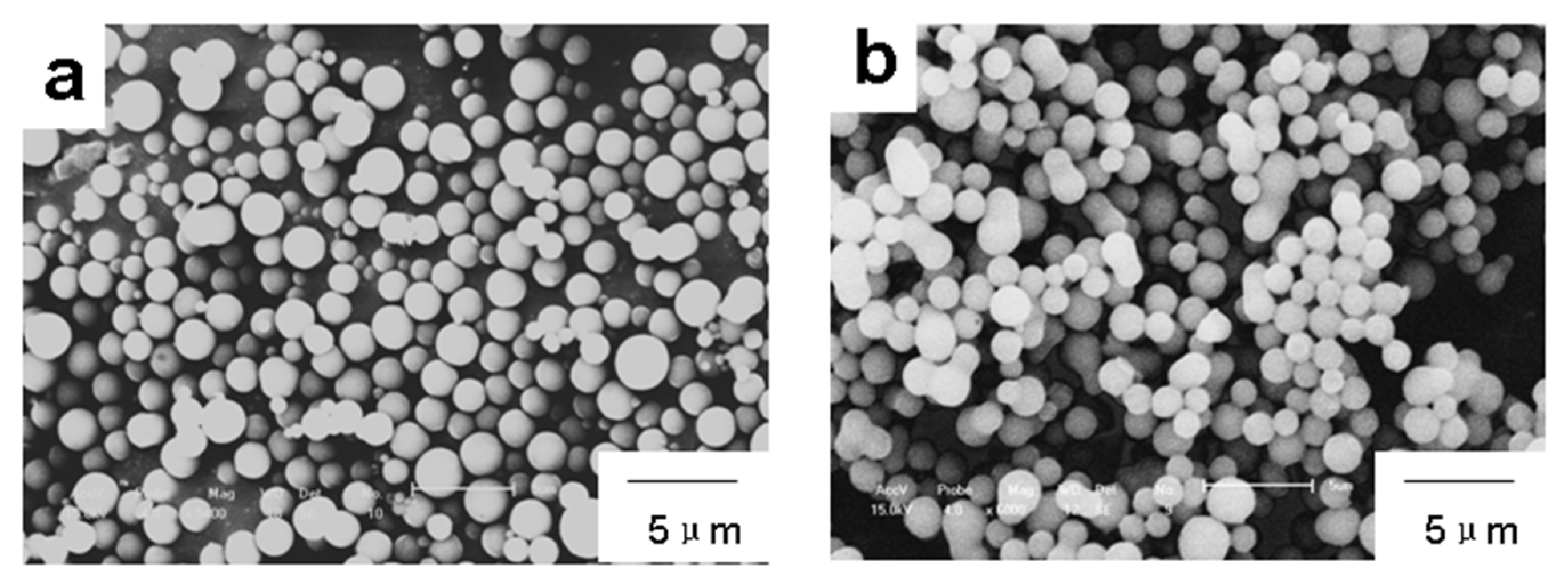

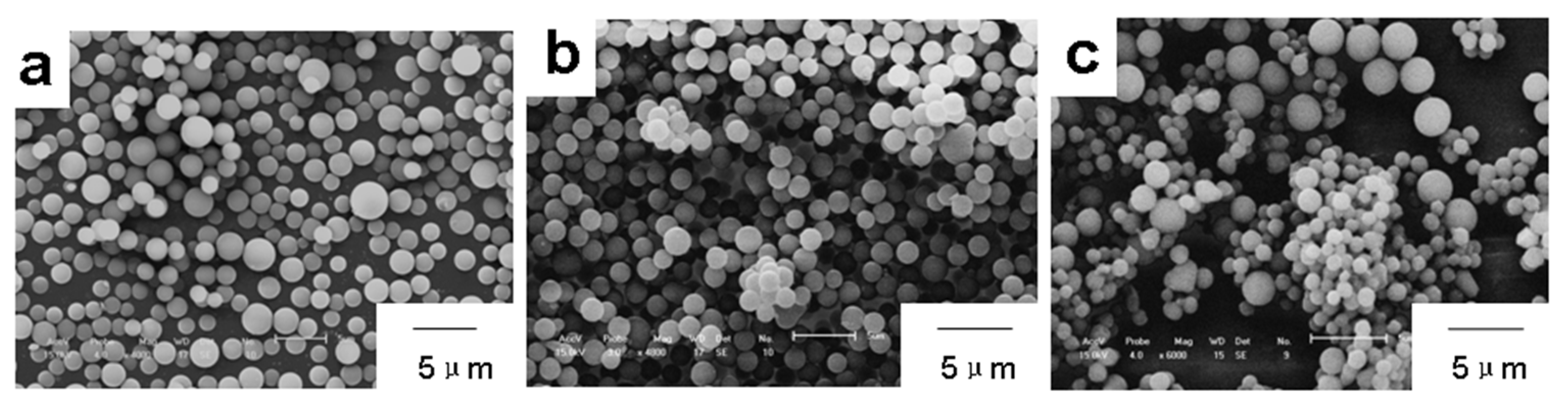

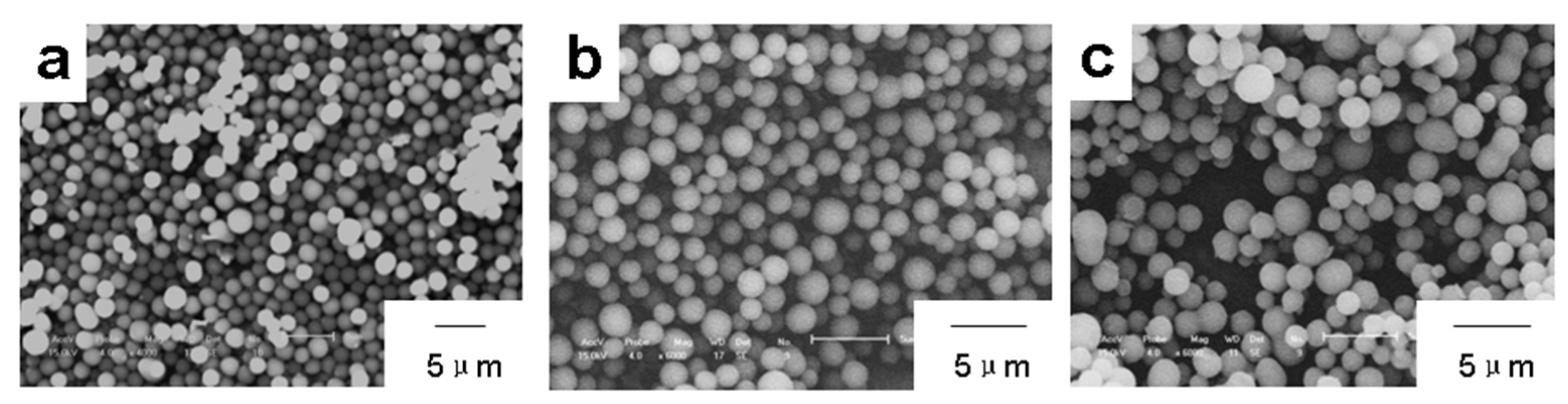

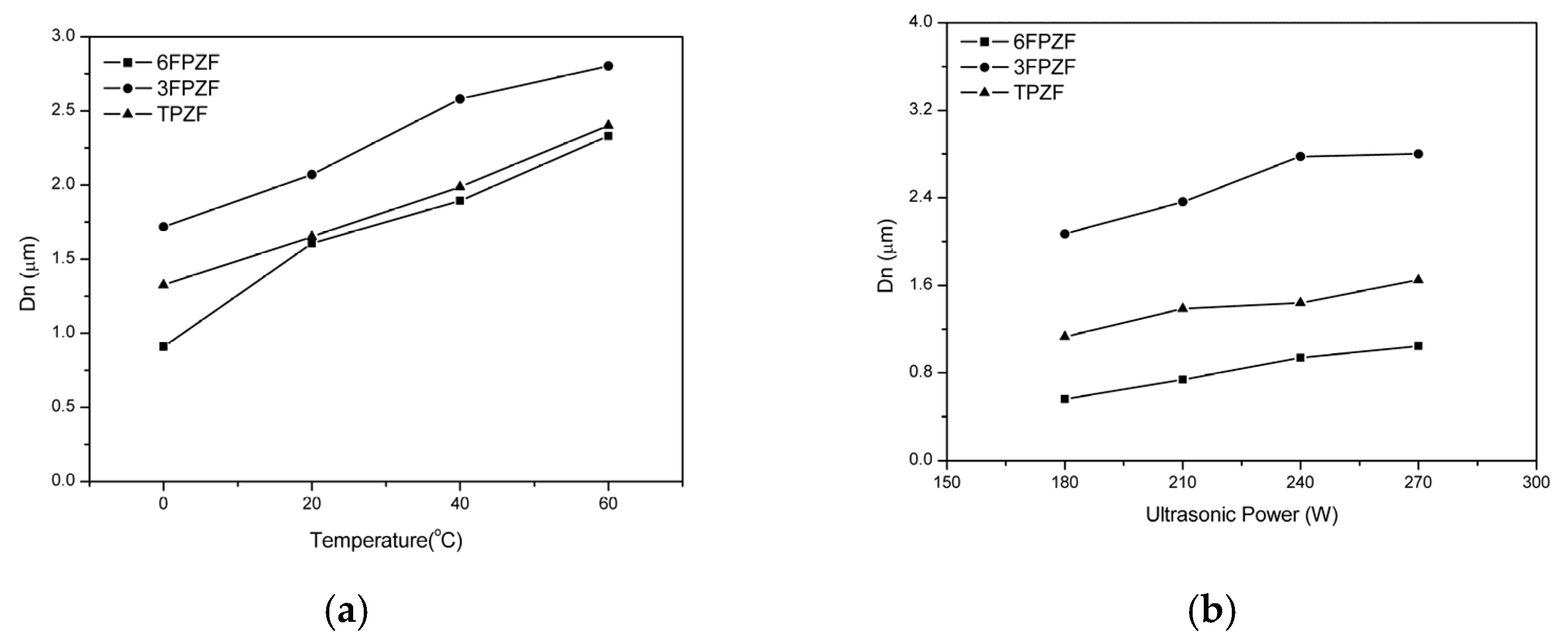

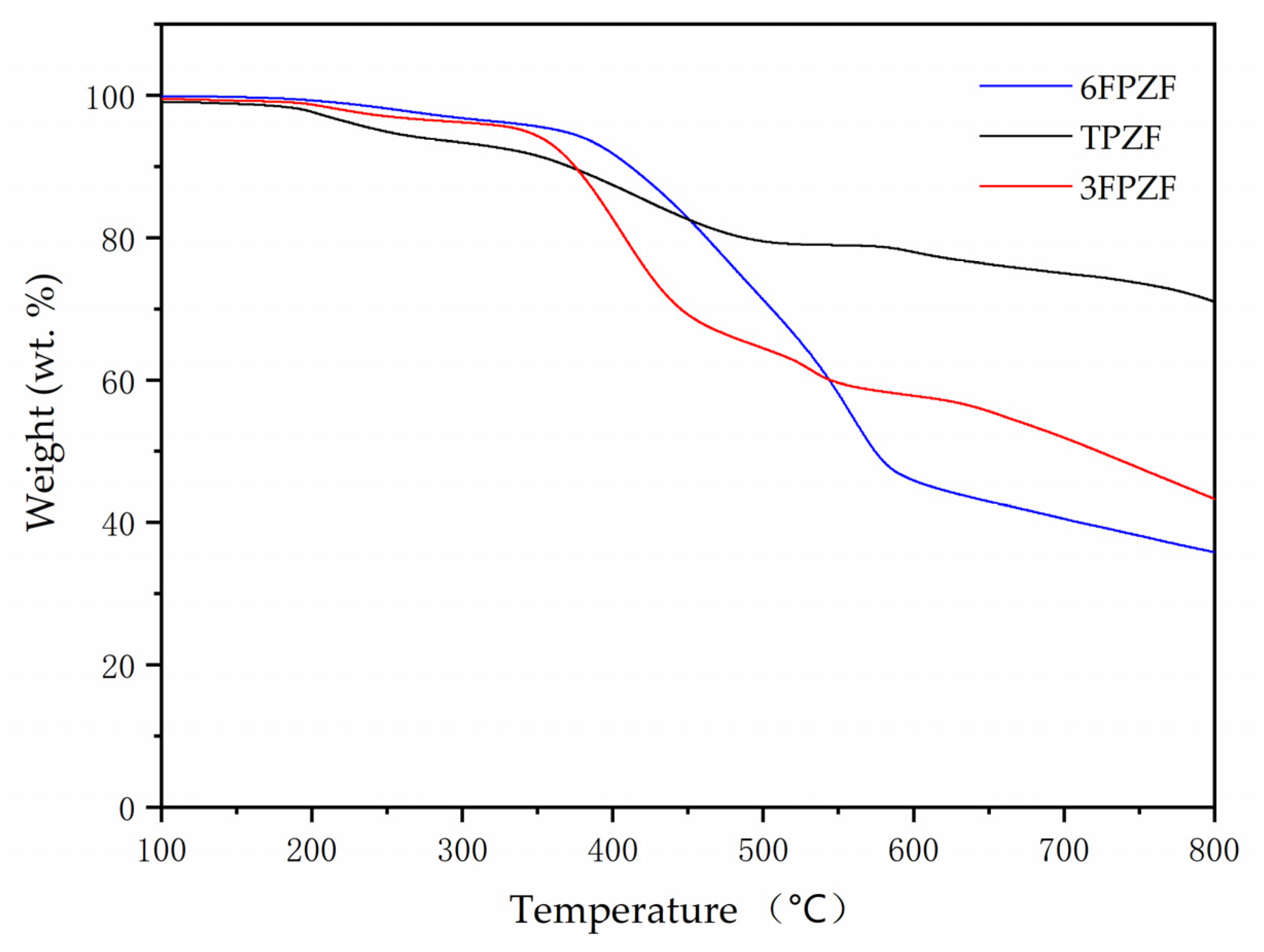

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singler, R.E.; Schneider, N.S.; Hagnauer, G.L. Polyphosphazenes—Synthesis-Properties-Applications. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1975, 15, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcock, H.R. Inorganic-Organic Polymers. Adv. Mater. 1994, 6, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jaeger, R.; Gleria, M. Poly(organophosphazene)s and related compounds: Synthesis, properties and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 1998, 23, 179–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.W.; Phelps, M.V.B.; Silva, R.J.; Gaumond, R.P.; Allcock, H.R. Patterning poly(organophosphazenes) for selective cell adhesion applications. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 1689–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Yang, Y.W.; Lee, H.F.; Yuan, C.Y. A flame-retardant phosphate and cyclotriphosphazene-containing epoxy resin: Synthesis and properties. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2000, 38, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, A.; Fantin, G.; Pedrini, P.; Gleria, M.; Minto, F. Functionalization of Phosphazenes. 1. Synthesis of phosphazene materials containing hydroxyl-groups. Macromolecules 1992, 25, 2569–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleria, M.; Bolognesi, A.; Porzio, W.; Catellani, M.; Destri, S.; Audisio, G. Grafting reactions onto poly(organophosphazenes). 1. The case of poly bis(4-isopropylphenoxy)phosphazene-g-polystyrene copolymers. Macromolecules 1987, 20, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luther, T.A.; Stewart, F.F.; Lash, R.P.; Wey, J.E.; Harrup, M.K. Synthesis and characterization of poly{hexakis (methy1)(4-hydroxyphenoxy) cyclotriphosphazene}. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 82, 3439–3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, D.; Nair, C.P.R.; Ninan, K.N. Phosphazene-triazine cyclomatrix network polymers: Some aspects of synthesis, thermal- and flame-retardant characteristics. Polym. Int. 2000, 49, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Femec, D.A.; McCaffrey, R.R. Solvent replacement in the synthesis of persubstituted phosphonitrilic hydroquinone prepolymer materials. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1994, 52, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cai, Q.; Wu, D.Z.; Jin, R.G. Phosphazene cyclomatrix network polymers: Some aspects of the synthesis, characterization, and flame-retardant mechanisms of polymer. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 95, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Xu, Y.Y.; Yuan, W.Z.; Xi, J.Y.; Huang, X.B.; Tang, X.Z.; Zheng, S.X. One-pot synthesis of poly(cyclotriphosphazene-co-4,4′-sulfonyldiphenol) nanotubes via an in situ template approach. Adv. Mater. 2006, 18, 2997–3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, H.W.; Huang, X.B.; Huang, Y.W.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, X.Z. Facile preparation of branched phosphazene-containing nanotubes via an in situ template approach. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2008, 293, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Huang, X.; Huang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, X. Preparation of Silver Nanocables Wrapped with Highly Cross-Linked Organic-Inorganic Hybrid Polyphosphazenes via a Hard-Template Approach. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 16840–16844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Huang, X.; Fu, H.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Tang, X. A One-Pot Approach to Novel Cross-Linked Polyphosphazene Microspheres with Active Amino Groups. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2009, 210, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.W.; Fu, J.W.; Pan, Y.; Huang, X.B.; Tang, X.Z. Pervaporation of ethanol aqueous solution by polyphosphazene membranes: Effect of pendant groups. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2009, 66, 504–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Dai, Q.Y.; Huang, X.B.; Tang, X.Z. Synthesis and characterization of novel magnetic Fe3O4/polyphosphazene nanofibers. Solid State Sci. 2009, 11, 1861–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.J.; Yuan, M.Y.; Zheng, X.W.; Huang, X.B. Facile synthesis of amino-functionalized polyphosphazene microspheres and their application for highly sensitive fluorescence detection of Fe3+. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2020, 137, 48937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhu, X.-Y.; Gao, Q.-L.; Fang, F.; Huang, X.-J. Surface modification of cyclomatrix polyphosphazene microsphere by thiol-ene chemistry and lectin recognition. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 387, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.J.; Wang, A.; Shi, X.M.; Li, J.M.; You, L.J.; Wang, S.Y. Preparation of multiple-spectra encoded polyphosphazene microspheres and application for antibody detection. Polym. Bull. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, L.L.; Zhang, W.H.; Jiang, Z.H.; Mu, J.X. A comparative structure-property study of polyphosphazene micro-nano spheres. Polym. Bull. 2014, 71, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.B.; Wang, D.; Jiang, Z.H.; Chen, C.H.; Zhang, W.J.; Wu, Z.W. The synthesis and properties of fluoropoly(aryl ether ketone)s. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. Chin. 2001, 22, 1053–1056. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.J.; Hu, W.; Chen, C.H.; Jiang, Z.H.; Zhang, W.J.; Wu, Z.W.; Matsumoto, T. Soluble aromatic poly(ether ketone)s with a pendant 3,5-ditrifluoromethylphenyl group. Polymer 2004, 45, 3241–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, S.E.; Yang, S.Y.; Choe, S.J. Mechanism of the formation of stable microspheres by precipitation copolymerization of styrene and divinylbenzene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2004, 42, 3967–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

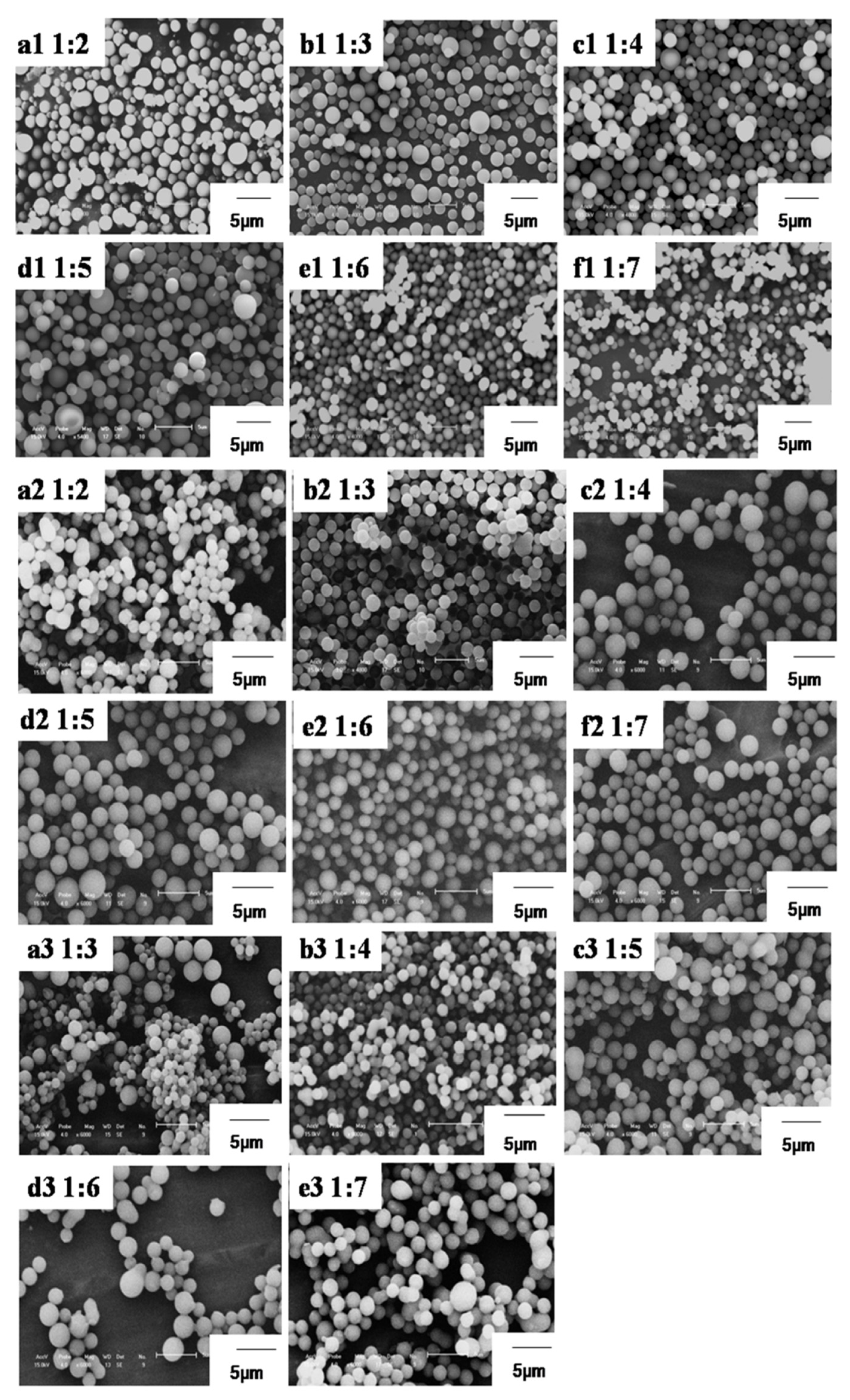

| 1:2 | 1:3 | 1:4 | 1:5 | 1:6 | 1:7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6FPZF | 1.43 μm | 1.53 μm | 1.5 μm | 1.54 μm | 1.51 μm | 1.42 μm |

| 3FPZF | 1.57 μm | 2.03 μm | 2.12 μm | 2.02 μm | 1.76 μm | 1.74 μm |

| TPZF | / | non-uniform | 1.97 μm | non-uniform | non-uniform | non-uniform |

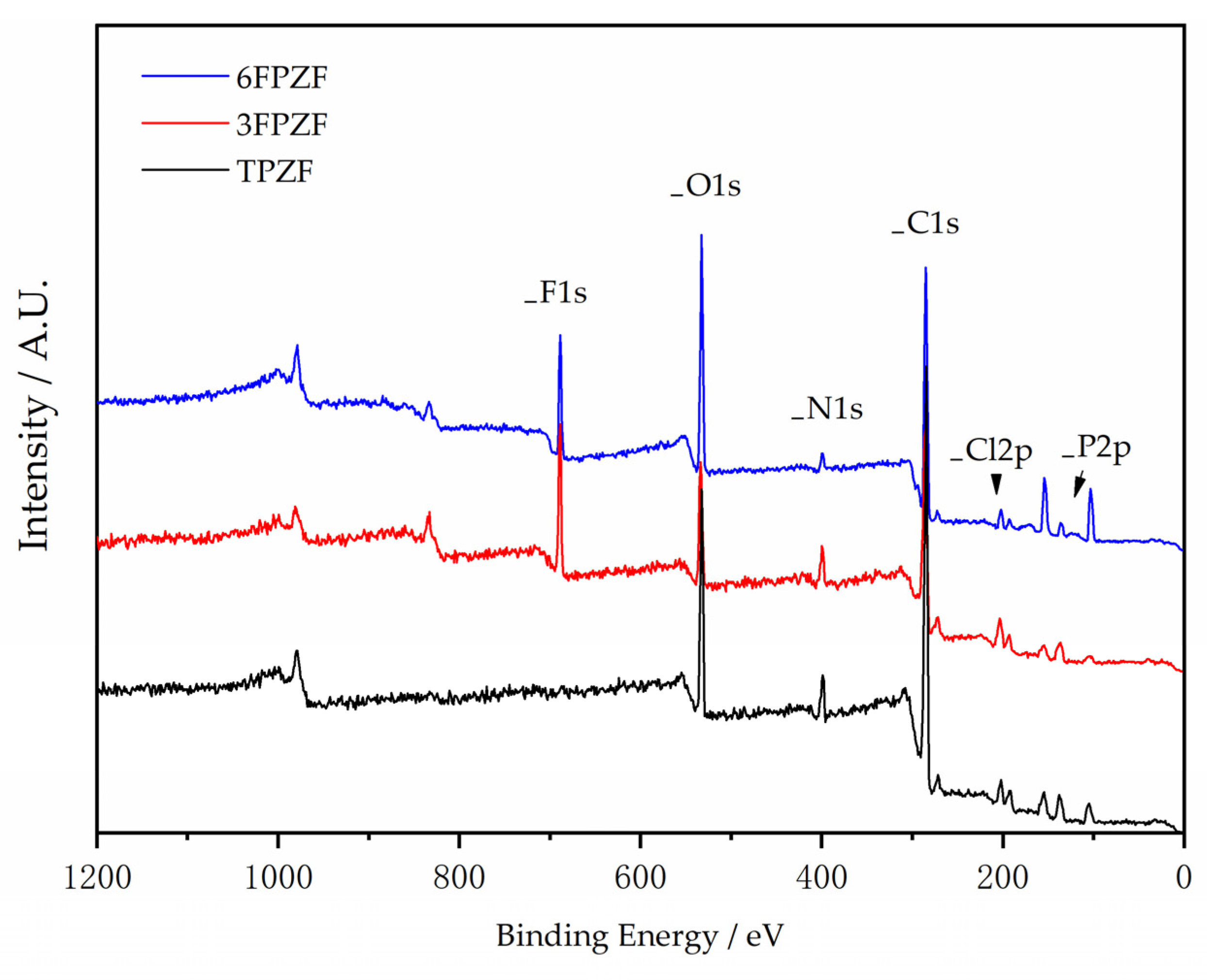

| P% | Cl% | C% | N% | O% | F% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6FPZF | 2.86 | 1.82 | 64.92 | 2.7 | 20.48 | 7.22 |

| 3FPZF | 5.97 | 4.7 | 63.65 | 5.38 | 11.61 | 8.7 |

| TPZF | 5.29 | 2.64 | 72.97 | 4.69 | 14.41 | 0 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Mu, J. Preparation and Properties of Novel Crosslinked Polyphosphazene-Aromatic Ethers Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Microspheres. Polymers 2022, 14, 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14122411

Wang Y, Yu Y, Li L, Zhang H, Chen Z, Yang Y, Jiang Z, Mu J. Preparation and Properties of Novel Crosslinked Polyphosphazene-Aromatic Ethers Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Microspheres. Polymers. 2022; 14(12):2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14122411

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yan, Yunwu Yu, Long Li, Hongbo Zhang, Zheng Chen, Yanchao Yang, Zhenhua Jiang, and Jianxin Mu. 2022. "Preparation and Properties of Novel Crosslinked Polyphosphazene-Aromatic Ethers Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Microspheres" Polymers 14, no. 12: 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14122411

APA StyleWang, Y., Yu, Y., Li, L., Zhang, H., Chen, Z., Yang, Y., Jiang, Z., & Mu, J. (2022). Preparation and Properties of Novel Crosslinked Polyphosphazene-Aromatic Ethers Organic–Inorganic Hybrid Microspheres. Polymers, 14(12), 2411. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14122411