The In Vivo, In Vitro and In Ovo Evaluation of Quantum Dots in Wound Healing: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Nanotechnologies

1.2. Quantum Dots

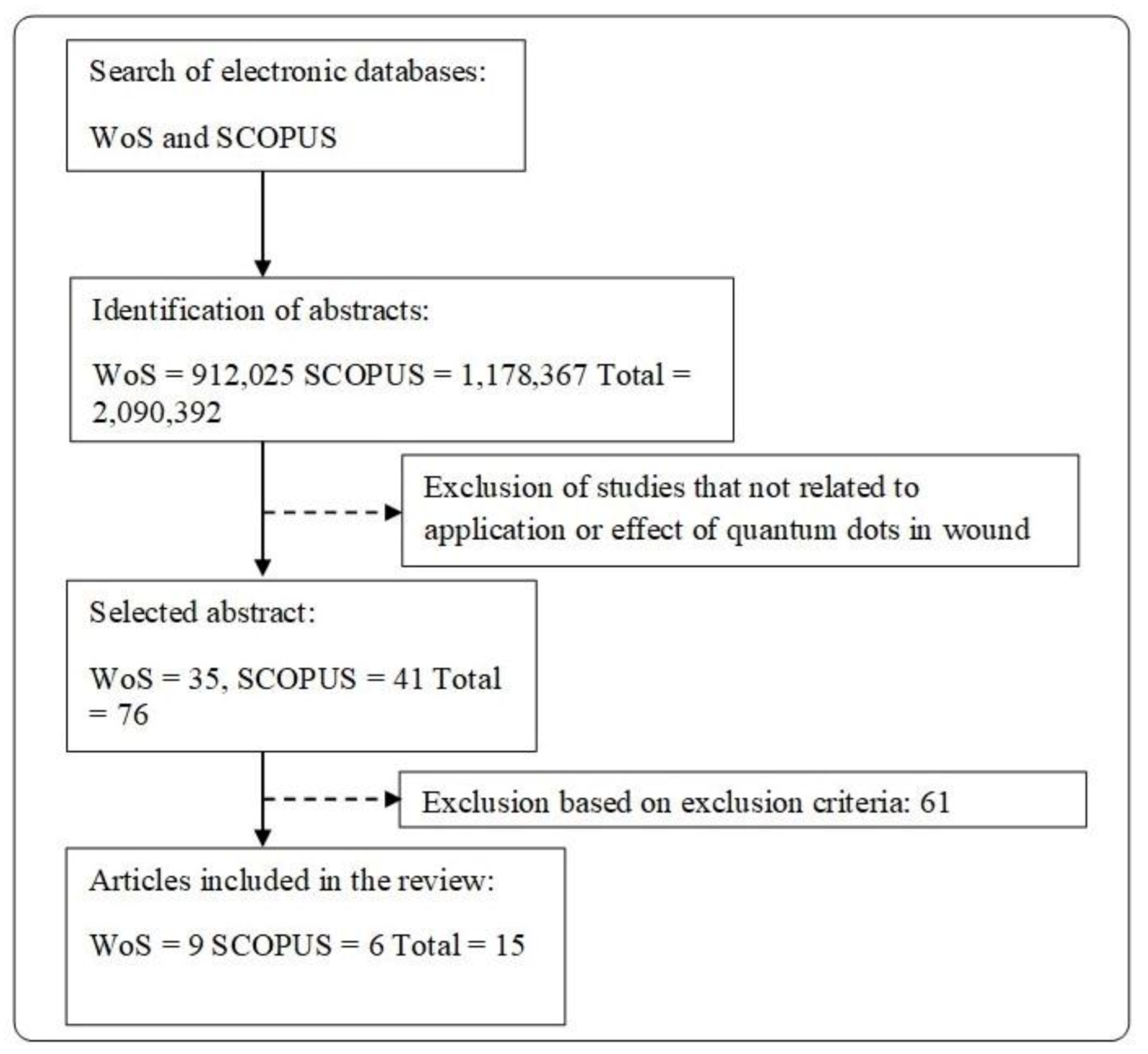

2. Literature Search

3. Wound Healing Properties of QDs

3.1. Wound Closure

3.2. Antibacterial Effects

3.3. Angiogenesis

4. Future Perspective

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| QDs | Quantum dots |

| VACM1 | Vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 |

| SELE | Selectin E, endothelial adhesion molecule 1 |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| IL-1 | Interleukin-1 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| HUVEC | Human umbilical vein endothelial cells |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| MIC | Minimum inhibition concentration |

References

- Padbury, J.F. Skin—The first line of defense. J. Pediatr. 2008, 152, A2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorg, H.; Tilkorn, D.J.; Hager, S.; Hauser, J.; Mirastschijski, U. Skin Wound Healing: An Update on the Current Knowledge and Concepts. Eur. Surg. Res. 2017, 58, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S. Wound assessment. Br. J. Commun. Nurs. 2019, 24, S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muangman, P.; Opasanon, S.; Suwanchot, S.; Thangthed, O. Efficiency of microbial cellulose dressing in partial-thickness burn wounds. J. Am. Col. Certif. Wound Spec. 2011, 3, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhivya, S.; Padma, V.V.; Santhini, E. Wound dressings—A review. BioMedicine 2015, 5, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percival, N.J. Classification of Wounds and their Management. Surgery 2002, 20, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, O.; Pérez-Amodio, S.; Navarro-Requena, C.; Mateos-Timoneda, M.Á.; Engel, E. Instructive microenvironments in skin wound healing: Biomaterials as signal releasing platforms. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2018, 129, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, H.N.; Hardman, M.J. Wound healing: Cellular mechanisms and pathological outcomes. Open Biol. 2020, 10, 200223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mh Busra, F.; Rajab, N.F.; Tabata, Y.; Saim, A.B.; BH Idrus, R.; Chowdhury, S.R. Rapid treatment of full-thickness skin loss using ovine tendon collagen type I scaffold with skin cells. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2019, 13, 874–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; DiPietro, L.A. Critical review in oral biology & medicine: Factors affecting wound healing. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.C.D.O.; Andrade, Z.D.A.; Costa, T.F.; Medrado, A.R.A.P. Wound healing—A literature review. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2016, 91, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera, A.E.; Spencer, J.M. Clinical aspects of full-thickness wound healing. Clin. Dermatol. 2007, 25, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsson, M.; Järbrink, K.; Divakar, U.; Bajpai, R.; Upton, Z.; Schmidtchen, A.; Car, J. The humanistic and economic burden of chronic wounds: A systematic review. Wound Repair Regen. 2019, 27, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, M.A.; Ibrahim, F.W.; Arshad, S.A.; Hui, C.K.; Jufri, N.F.; Hamid, A. Cytotoxicity, proliferation and migration rate assessments of human dermal fibroblast adult cells using zingiber zerumbet extract. Sains Malays. 2019, 48, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.S.; Khurshid, Z.; Almas, K. Oral tissue engineering progress and challenges. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2015, 12, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landén, N.X.; Li, D.; Ståhle, M. Transition from inflammation to proliferation: A critical step during wound healing. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3861–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vig, K.; Chaudhari, A.; Tripathi, S.; Dixit, S.; Sahu, R.; Pillai, S.; Dennis, V.; Singh, S. Advances in Skin Regeneration Using Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinke, J.M.; Sorg, H. Wound repair and regeneration. Eur. Surg. Res. 2012, 49, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, D.M.; Liu, Z.-J.; Velazquez, O.C. Oxygen: Implications for Wound Healing. Adv. Wound Care 2012, 1, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, U.A.; Dipietro, L.A. Diabetes and wound angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouin, J.P.; Kiecolt-Glaser, J.K. The Impact of Psychological Stress on Wound Healing: Methods and Mechanisms. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2011, 31, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carolina, E.; Kato, T.; Khanh, V.C.; Moriguchi, K.; Yamashita, T.; Takeuchi, K.; Hamada, H.; Ohneda, O. Glucocorticoid impaired the wound healing ability of endothelial progenitor cells by reducing the expression of CXCR4 in the PGE2 pathway. Front. Med. 2019, 5, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, M.S.; Alnazzawi, A.A.; Alrahabi, M.; Fareed, M.A.; Najeeb, S.; Khurshid, Z. Nanotechnology and nanomaterials in dentistry. In Advanced Dental Biomaterials; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 477–505. ISBN 9780081024768. [Google Scholar]

- Kalashnikova, I.; Das, S.; Seal, S. Nanomaterials for wound healing: Scope and advancement. Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 2593–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaemi, F.; Abdullah, L.C.; Kargarzadeh, H.; Abdi, M.M.; Azli, N.F.W.M.; Abbasian, M. Comparative study of the electrochemical, biomedical, and thermal properties of natural and synthetic nanomaterials. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virlan, M.J.R.; Miricescu, D.; Radulescu, R.; Sabliov, C.M.; Totan, A.; Calenic, B.; Greabu, M. Organic nanomaterials and their applications in the treatment of oral diseases. Molecules 2016, 21, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mihai, M.M.; Dima, M.B.; Dima, B.; Holban, A.M. Nanomaterials for Wound Healing and Infection Control. Materials 2019, 12, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, R.; Al-Qudaihi, A.; Alaseel, S.E.; Fita, I.Z.; Khalid, M.S.; Pottoo, F.H. Preparation of a novel curcumin nanoemulsion by ultrasonication and its comparative effects in wound healing and the treatment of inflammation. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 20192–20206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, Z.; Najeeb, S.; Khurshid, Z.; Verma, V.; Rashid, H.; Glogauer, M. Biodegradable materials for bone repair and tissue engineering applications. Materials 2015, 8, 5744–5794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salleh, A.; Naomi, R.; Utami, N.D.; Mohammad, A.W.; Mahmoudi, E.; Mustafa, N.; Fauzi, M.B. The Potential of Silver Nanoparticles for Antiviral and Antibacterial Applications: A Mechanism of Action. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefat, F.; Raja, T.I.; Zafar, M.S.; Khurshid, Z.; Najeeb, S.; Zohaib, S.; Ahmadi, E.D.; Rahmati, M.; Mozafari, M. Nanoengineered biomaterials for cartilage repair. In Nanoengineered Biomaterials for Regenerative Medicine; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 39–71. ISBN 9780128133552. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, M.X.; Zhu, B.J. The Research and Applications of Quantum Dots as Nano-Carriers for Targeted Drug Delivery and Cancer Therapy. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekimov, A.; Onushchenko, A. Quantum size effect in three-dimensional microscopic semiconductor crystals. Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. Lett. 1981, 34, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Matea, C.T.; Mocan, T.; Tabaran, F.; Pop, T.; Mosteanu, O.; Puia, C.; Iancu, C.; Mocan, L. Quantum dots in imaging, drug delivery and sensor applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2017, 12, 5421–5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenthal, S.J.; Chang, J.C.; Kovtun, O.; McBride, J.R.; Tomlinson, I.D. Biocompatible quantum dots for biological applications. Chem. Biol. 2011, 18, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haw, C.; Chiu, W.; Khanis, N.H.; Abdul Rahman, S.; Khiew, P.; Radiman, S.; Abd-Shukor, R.; Abdul Hamid, M.A. Tin stearate organometallic precursor prepared SnO2 quantum dots nanopowder for aqueous- and non-aqueous medium photocatalytic hydrogen gas evolution. J. Energy Chem. 2016, 25, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsaheb, M.; Asadi, A.; Sillanpää, M.; Farhadian, N. Application of carbon quantum dots to increase the activity of conventional photocatalysts: A systematic review. J. Mol. Liq. 2018, 271, 857–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M.; Nejabat, M.; Charbgoo, F.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Abnous, K. Graphene-Based Hybrid Nanomaterials for Biomedical Applications. In Biomedical Applications of Graphene and 2D Nanomaterials; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 119–141. ISBN 9780128158890. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Zhou, Z.W.; Pan, S.T.; He, Z.X.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, J.X.; Duan, W.; Yang, T.; Zhou, S.F. Graphene quantum dots induce apoptosis, autophagy, and inflammatory response via p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and nuclear factor-κB mediated signaling pathways in activated THP-1 macrophages. Toxicology 2015, 327, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Fan, S.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, X.; Boudreau, M.D.; Pan, Y.; Tian, X.; Yin, J.J. Bactericidal effects and accelerated wound healing using Tb4O7 nanoparticles with intrinsic oxidase-like activity. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba, L.; Scarabelli, T. Metallic nanoparticles and their medicinal potential. Part II: Aluminosilicates, nanobiomagnets, quantum dots and cochleates. Ther. Deliv. 2013, 4, 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omidi, M.; Yadegari, A.; Tayebi, L. Wound dressing application of pH-sensitive carbon dots/chitosan hydrogel. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 10638–10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafieerad, A.; Yan, W.; Sequiera, G.L.; Sareen, N.; Abu-El-Rub, E.; Moudgil, M.; Dhingra, S. Application of Ti3C2 MXene Quantum Dots for Immunomodulation and Regenerative Medicine. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shereema, R.M.; Sruthi, T.V.; Kumar, V.B.S.; Rao, T.P.; Shankar, S.S. Angiogenic Profiling of Synthesized Carbon Quantum Dots. Biochemistry 2015, 54, 6352–6356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romoser, A.A.; Chen, P.L.; Berg, J.M.; Seabury, C.; Ivanov, I.; Michael, F.M.; Sayes, C.M. Quantum dots trigger immunomodulation of the NFκB pathway in human skin cells. Mol. Immunol. 2011, 48, 1349–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, D.; Xue, X. Fabrication of pH-responsive TA-keratin bio-composited hydrogels encapsulated with photoluminescent GO quantum dots for improved bacterial inhibition and healing efficacy in wound care management: In vivo wound evaluations. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2020, 202, 111676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamad, N.; Loh, E.Y.X.; Fauzi, M.B.; Ng, M.H.; Mohd Amin, M.C.I. In vivo evaluation of bacterial cellulose/acrylic acid wound dressing hydrogel containing keratinocytes and fibroblasts for burn wounds. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2019, 9, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, R.; Niu, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.M. Bienzymatic synergism of vanadium oxide nanodots to efficiently eradicate drug-resistant bacteria during wound healing in vivo. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 559, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, L.; Wu, W.; Zheng, Y.; Lin, L.; Weng, S.; Lin, X. Nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots as an antimicrobial agent against Staphylococcus for the treatment of infected wounds. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 179, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankoti, K.; Rameshbabu, A.P.; Datta, S.; Das, B.; Mitra, A.; Dhara, S. Onion derived carbon nanodots for live cell imaging and accelerated skin wound healing. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 6579–6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghshenas, M.; Hoveizi, E.; Mohammadi, T.; Kazemi Nezhad, S.R. Use of embryonic fibroblasts associated with graphene quantum dots for burn wound healing in Wistar rats. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2019, 55, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Mao, C.; Liu, X.; Cui, Z.; Jing, D.; Yang, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Zheng, Y.; et al. Rapid and Superior Bacteria Killing of Carbon Quantum Dots/ZnO Decorated Injectable Folic Acid-Conjugated PDA Hydrogel through Dual-Light Triggered ROS and Membrane Permeability. Small 2019, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Sun, Y.; Fan, S.; Boudreau, M.D.; Chen, C.; Ge, C.; Yin, J.J. Photogenerated Charge Carriers in Molybdenum Disulfide Quantum Dots with Enhanced Antibacterial Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 4858–4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Yu, J.; Lv, F.; Yan, L.; Zheng, L.R.; Gu, Z.; Zhao, Y. Functionalized Nano-MoS2 with Peroxidase Catalytic and Near-Infrared Photothermal Activities for Safe and Synergetic Wound Antibacterial Applications. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 11000–11011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Gao, N.; Dong, K.; Ren, J.; Qu, X. Graphene quantum dots-band-aids used for wound disinfection. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 6202–6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.; Han, F.; Cao, W.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Gong, X.; Turnbull, G.; Shu, W.; Xia, L.; et al. Carbon quantum dots derived from lysine and arginine simultaneously scavenge bacteria and promote tissue repair. Appl. Mater. Today 2020, 19, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, G.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Shen, J. Facile synthesis of ZnO QDs@GO-CS hydrogel for synergetic antibacterial applications and enhanced wound healing. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 378, 122043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas Hess, C. Checklist for Factors Affecting Wound Healing. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2011, 24, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wang, Q.; Lu, S.; Niu, Y. Hydrogen Peroxide: A Potential Wound Therapeutic Target? Med. Princ. Pract. 2017, 26, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Song, Z.; Gu, J.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Han, H. Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots for Preventing Biofilm Formation and Eradicating Drug-Resistant Bacteria Infection. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 4739–4749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmir, S.; Karbalaei, A.; Pourmadadi, M.; Hamedi, J.; Yazdian, F.; Navaee, M. Antibacterial properties of a bacterial cellulose CQD-TiO2 nanocomposite. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 234, 115835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muktha, H.; Sharath, R.; Kottam, N.; Srinath, S.; Randhir, Y. Evaluation of Antibacterial and In vivo Wound healing activity of Carbon Dot Nanoparticles. Nanoscale Rep. 2019, 2, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zheng, Y.; Song, W.; Luan, J.; Wen, X.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Guo, S. In situ synthesis of silver-nanoparticles/bacterial cellulose composites for slow-released antimicrobial wound dressing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 102, 762–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajendiran, K.; Zhao, Z.; Pei, D.S.; Fu, A. Antimicrobial activity and mechanism of functionalized quantum dots. Polymers 2019, 11, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demidova-Rice, T.N.; Durham, J.T.; Herman, I.M. Wound Healing Angiogenesis: Innovations and Challenges in Acute and Chronic Wound Healing. Adv. Wound Care 2012, 1, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shibuya, M. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) and Its Receptor (VEGFR) Signaling in Angiogenesis: A Crucial Target for Anti- and Pro-Angiogenic Therapies. Genes Cancer 2011, 2, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balakrishnan, S.; Bhat, F.A.; Raja Singh, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Elumalai, P.; Das, S.; Patra, C.R.; Arunakaran, J. Gold nanoparticle-conjugated quercetin inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition, angiogenesis and invasiveness via EGFR/VEGFR-2-mediated pathway in breast cancer. Cell Prolif. 2016, 49, 678–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maarof, M.; Law, J.X.; Chowdhury, S.R.; Khairoji, K.A.; Saim, A.B.; Idrus, R.B.H. Secretion of wound healing mediators by single and bi-layer skin substitutes. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 1873–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.L.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.M.; Song, P.; Xu, J.; Li, P.; Wang, S.; Yang, L. Amorphous nano-selenium quantum dots improve endothelial dysfunction in rats and prevent atherosclerosis in mice through Na + /H + exchanger 1 inhibition. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2019, 115, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Panwar, V.; Chopra, V.; Thomas, J.; Kaushik, S.; Ghosh, D. Interaction of Carbon Dots with Endothelial Cells: Implications for Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 5483–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, E.Y.X.; Mohamad, N.; Fauzi, M.B.; Ng, M.H.; Ng, S.F.; Mohd Amin, M.C.I. Development of a bacterial cellulose-based hydrogel cell carrier containing keratinocytes and fibroblasts for full-thickness wound healing. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, N.E.; Kellenberger, L.; Greenaway, J.; Moorehead, R.A.; Linnerth-Petrik, N.M.; Petrik, J. Extracellular Matrix Proteins and Tumor Angiogenesis. J. Oncol. 2010, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonnesen, M.G.; Feng, X.; Clark, R.A.F. Angiogenesis in wound healing. J. Investig. Dermatology Symp. Proc. 2000, 5, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufan, A.; Satiroglu-Tufan, N. The Chick Embryo Chorioallantoic Membrane as a Model System for the Study of Tumor Angiogenesis, Invasion and Development of Anti-Angiogenic Agents. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2005, 5, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, M.; Brahma, P.; Dixit, M. A Cost-Effective and Efficient Chick Ex-Ovo CAM Assay Protocol to Assess Angiogenesis. Methods Protoc. 2018, 1, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lokman, N.A.; Elder, A.S.F.; Ricciardelli, C.; Oehler, M.K. Chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay as an in vivo model to study the effect of newly identified molecules on ovarian cancer invasion and metastasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 9959–9970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Copeland, C.; Henry, S.; Barbul, A. Complex Wounds and Their Management. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 90, 1181–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón-Jiménez, B.; Johnson, M.E.; Montoro Bustos, A.R.; Murphy, K.E.; Winchester, M.R.; Baudrit, J.R.V. Silver nanoparticles: Technological advances, societal impacts, and metrological challenges. Front. Chem. 2017, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

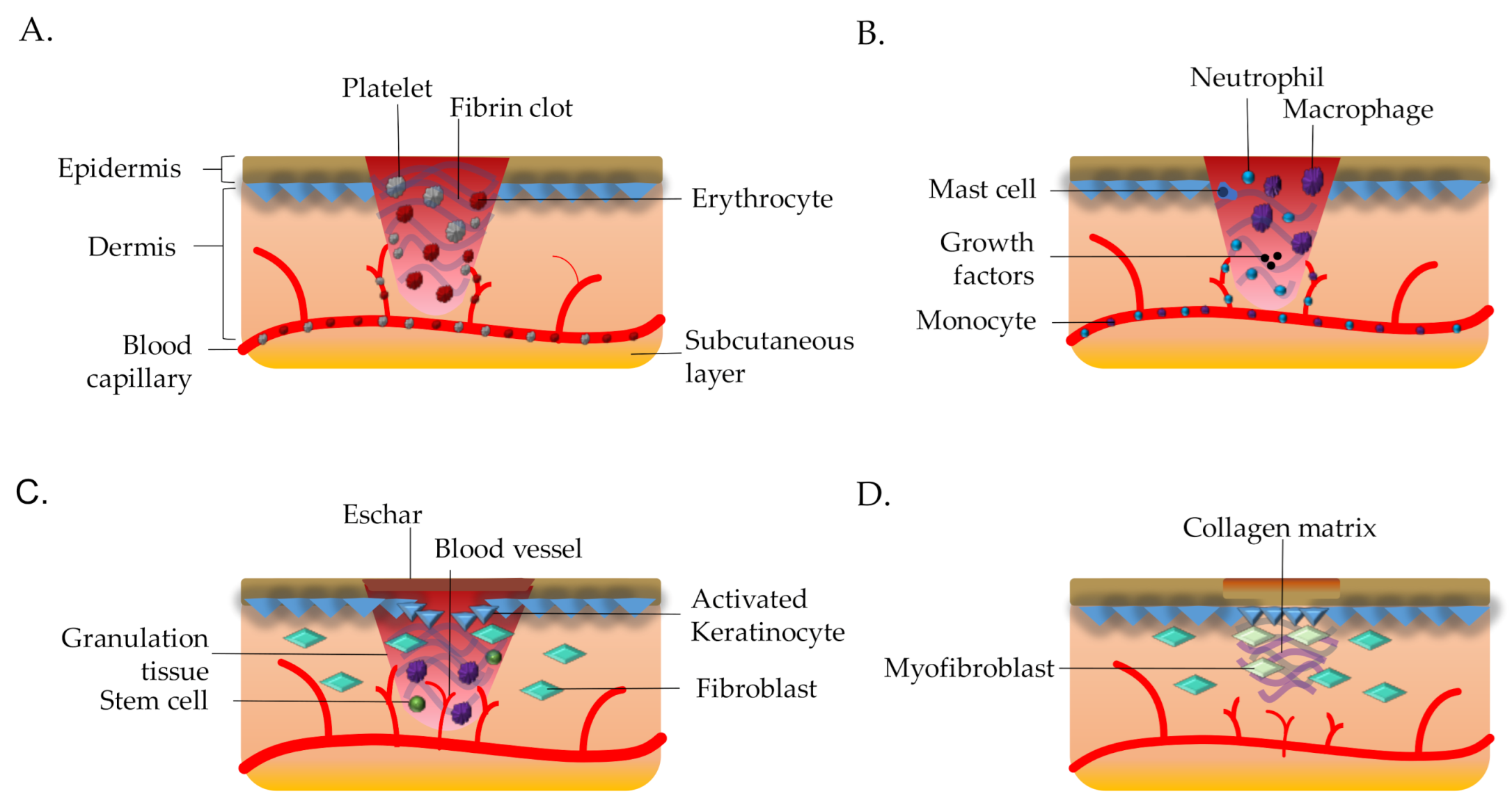

| Phase | Biological Events |

|---|---|

| Hemostasis [16] | Exposure of collagen initiates intrinsic and extrinsic clotting cascades Thrombocytes aggregated and triggering the vasoconstriction Blot clot formation to act as a temporary wound matrix—assist in migration of cells Blood vessels dilated; thrombocytes and leukocytes migrated after 5 to 10 min of vasoconstriction Platelets degranulated—cytokines and growth factors released into the wound |

| Inflammation [11] | The increasing number of leukocytes in the wound area Expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines caused by transmigration of neutrophils through endothelial cells Pro-inflammatory cytokines promote the adhesion molecules expression e.g., intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM1) and selectin (SELE) The neutrophils will migrate against the chemokine gradients, where there are high concentration of chemokines in this case wound site Neutrophils performed phagocytosis and produce cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) to increase the inflammatory response Monocytes will migrate to wound site and differentiate into macrophages after 3 days injury—attract other inflammatory cells and produce prostaglandins |

| Proliferation [17] | The proliferation of vascular endothelial cells and fibroblasts due to secretion of growth factors by inflammatory cells Collagen secreted by fibroblasts to replace the fibrin matrix Differentiation of fibroblasts into myofibroblasts expressing actin—contraction and reduction of the wound area Healthy tissues and endothelial progenitors initiated the angiogenesis Formation of granulation tissue—the invasion of vascular endothelial cells and capillaries |

| Remodeling [18] | Collagen III replaced by collagen I Myofibroblasts attach to collagen for wound contraction and help decrease development of scar Angiogenic process diminished—wound blood flow declines and metabolic activity slows down until it stops |

| No. | References | Experimental Model | Type of Quantum Dots | Outcome Measures | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ma et al., 2019 [48] | Sprague-Dawley rats 6 weeks old Weight 200 g Excision wound (1.00 cm2) | VOxNDs | 1. Morphology of wound 2. Histological evaluation (H & E stain) | H2O2/ VOxNDs have 60% decrease in wound area compared to control and rigid epidermal layer after 6 days therapy | H2O2/VOxNDs group have the greatest wound healing capacity among all tested group |

| 2 | Zhao et al., 2019 [49] | Sprague-Dawley rats Weight 250 ± 20 g Full thickness wound (1.80 cm2) | NCQDs | 1. Wound morphology 2. Histological evaluation (H & E stain) 3. White blood count (blood slide) | Treatment with NCQDs have significantly higher healing rate where the wound area is 0.2% at the 14th day of treatment and lower white blood count which is 1 × 1010 L−1 indicate decrease of inflammation in wound area | NCQDs show effective treatment towards wound healing |

| 3 | Bankoti et al., 2017 [50] | Albino Wistar rats Weights 150–200 g Excision wound (3.14 cm2) | CND | 1. Morphology evaluation 2. Histological examination (H & E stain) | Treatment of OCNDs had more than 80% of healing compare to control (65%) and shown to have intact dermal and epidermal structure which does not show signs of inflammation nor infection | Topical application of OCNDs improved the wound healing process |

| 4 | Haghshenas et al., 2019 [51] | Wistar rats Burn wound | GQDs | 1. Morphology study of recovery process 2. Histological assessment (H & E stain and Masson’s trichrome staining) | Treatment group have higher healing rate than control group and formation of fibroblasts are 10% higher than control | GQDs able to accelerate the repair of skin lesion in burn wound healing model |

| 5 | Ren et al., 2020 [46] | Rats 10–12 weeks old Weight 250–300 g Full thickness wound (1.50 cm2) | GOQDs | 1. Gross morphology of wound 2. Histological assessment (H & E stain) | Treatment with TA/KA-GOQDs show 98% of wound are closure and matured epidermal layer after 16 days of treatment | TA/KA-GOQDs proves its ability to treat wounds within short period of time and without side effects |

| 6 | Xiang et al., 2019 [52] | Rats Incision wound | CQDs | 1. Gross morphology of wound 2. Histological assessment (H & E stain and Masson’s trichrome staining) | DFT-C/ZnO-hydrogel-treated group have 95.7% of wound closure by 10 days of treatment. H & E staining show that this treatment group have complete epidermal structure in 2 days Dense collagen fiber have been observed in treatment group after 10th day of treatment | Treatment with DFT-C/ZnO-hydrogel groups exhibit the best wound healing results |

| 7 | Omidi et al., 2017 [42] | Rat Weights 260 g Excision wound (1.00 cm2) | CND | 1. Morphology evaluation | The wound heals at ~100% at 16th days in with CDs/chitosan nanocomposite compared to 40% of control group | The characteristic of CDs/chitosan shown to be beneficial as wound dressing products |

| 8 | Tian et al., 2019 [53] | BALB/c mice 8 weeks old Incision wound | MoS2QDs | 1. Morphology evaluation | The infected wounds almost 90% completely healed in photoexcited MoS2QDs group, compared to control group | The potential application of the of MoS2 QDs was demonstrated great improvement of wound healing |

| 9 | Yin et al., 2016 [54] | Female BALB/c mice 8 weeks old Weight 18–23 g Excision wound (0.78 cm2) | MoS2NF | 1. Gross morphology of wound 2. Histological assessment (H & E stain and Masson’s trichrome stain) | The treatment groups show formation of epidermal layer for wound closure at 5th day of treatment and attachment of collagen fiber with dermal layer | The MoS2NF shown improvement of wound healing in short period of time |

| 10 | Sun et al., 2014 [55] | Male Kunming mice 6–8 weeks old Weight 180–220 g Excision wound (0.04 cm2) | GQDs | 1. Gross morphology of wound | Treatment with H2O2 and GQD band aid groups shows no significant results in wound closure | Treatment with GQD band aid groups as wound dressing shows no significant result for wound healing |

| 11 | Li et al., 2020 [56] | Male mice 6–8 weeks old Weight 180–220 g Incision wound (1.6 cm2) | CQDs | 1. Gross morphology of wound 2. Histological assessment (H & E stain) | CQDs-treated group show complete closure of wound and higher degree of healing within 5 days of treatment | CDQs contribute to faster wound healing and great potential for wound dressing |

| 12 | Liang et al., 2019 [57] | Male mice Excision wound (0.79 cm2) | ZnOQDs | 1. Morphology assessment | Treatment of ZnOQDs with GO-CS hydrogel shown 90% of wound closure after 14th day of treatment | ZnOQDs imbedded in GO-CS hydrogel show potential to be used for wound dressing |

| No | References | Experimental Model | Type Of Quantum Dots | Outcome Measures | Results | Antibacterial Mechanism | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yin et al., 2016 [54] | 1. Ampr E. coli 2. B. subtilis | MoS2NF | 1. Plate counting method 2. Morphology of the bacteria 3. Characterization of bacterial death | The bacteria that were incubated with MoS2 + H2O2 and exposed to the 808 nm laser show reduction in the bacteria viability and the bacteria inactivation of bacteria are 97% and 100% for Ampr E. coli and B. subtilis, respectively | The nanoparticles bind to bacterial membrane and decrease the integrity of the membrane. | PEG-MoS2NFs possess peroxidase catalytic activity and show to be effective for antibacterial properties |

| 2 | Omidi et al., 2017 [42] | 1. Staphylococcus aureus | CND | 1. Disc diffusion method 2. Optical density | The CDs showed inhibition zone of 3.1 mm, 3.7 mm and 4.6 mm for 5%, 10% and 15% v/v, respectively and inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus in the concentration of CDs was more than 10 mg ml−1 | No mechanism of action has been scrutinized in the research article. | The chitosan/CDs nanocomposites had antibacterial activity by inducing a clear inhibition of bacterial growth |

| 3 | Tian et al., 2019 [53] | 1. E. coli 2. S. aureus | MoS2QDs | 1. Plate counting method 2. Morphological observation of bacterial death 3. ROS measurement | The survival rates of bacteria were still above 80% for both S. aureus and E. coli treated with MoS2QDs | The production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) | Treatment of MoS2QDs may be effective towards Gram-positive but not in Gram-negative bacteria due to its dual layer of membrane |

| 4 | Xiang et al., 2019 [52] | 1. E. coli 2. S. aureus | CQDs | 1. Spread plate method 2. Morphology of bacteria | The antibacterial rates of the DFT-C/ZnO-hydrogel for S. aureus and E. coli are 78.9% and 70.7%, respectively and the cellular membrane are disrupted when exposed to treatment group in 15 min. | The release of Zn2+ ion into the bacterial membrane which increase the oxidative stress in bacteria. | The combination of carbon quantum dots/ZnO and folic acid-conjugated PDA hydrogel have shown high antibacterial properties |

| 5 | Liang et al., 2019 [57] | 1. E. coli 2. S. aureus | ZnOQDs | 1. Spread plate method 2. Gross appearance of bacteria 3. Characterization of bacterial death | The antibacterial efficacy was significantly improved by 98.90% against S. aureus and by 99.50% against E. coli when the ZnO QDs@GO-CS hydrogel was under 808 nm light irradiation | The release of Zn2+ which inhibit respiratory enzymes and ROS production. | The ZnO QDs@GO-CS hydrogel have a higher antibacterial property when expose to light radiation. |

| 6 | Sun et al., 2014 [55] | 1. E. coli 2. S. aureus | GQDs | 1. Disk diffusion assay 2. Growth-inhibition assay 3. Morphology of bacteria | Treatment with H2O2 with both GQDs cause the number of bacteria decreases and the bacterial surface became rough and wrinkled | The peroxide—like activity of GQD causes the loss in the integrity of cell wall and thus rupture the bacterial membrane. | The antibacterial ability of H2O2 had been remarkably improved with the help of GQDs |

| 7 | Zhao et al., 2019 [49] | 1. S. aureus (ATCC6538, ATCC43300) 2. S. epidermidis 3. Methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus 4. E. coli 5. Salmonella paratyphi-β 6. Pseudomonas aeruginosa 7. Enterococcus faecalis | N-CQDs | 1. Disk diffusion method 2. Broth diffusion method 3. Characterization of bacterial death | There was 15.5 nm of inhibition zones observed on the agar plates that incubate S. aureus (ATCC6538 and ATCC43300), S. epidermidis, and MRSA and minimum inhibition concentration (MIC) results are measured 0.128 and 0.256 mg/mL on NCQDs on and S. aureus (ATCC6538) | The positively charged NCQD bind with negatively charged bacteria causing rupture on the cell membrane. | NCQDs exercised broad antimicrobial activity over various bacterial forms |

| 8 | Ren et al., 2020 [46] | 1. E. coli 2. S. aureus | GOQDs | 1. Spread plate method | The bacterial survival rate decreases to 20% and 30% for S. aureus and E. coli respectively in TA/KA-GOQDs | The antibacterial mechanism of nanoparticles does not explain in the article. | Treatment of GOQDs with TA/KA hydrogels have high antibacterial properties |

| 9 | Ma et al., 2020 [48] | 1. E. coli 2. MRSA | Vanadium oxide nanodots | 1. Spread plate method 2. Morphology studies on bacteria | The CFU of H2O2/VOxNDs are the lowest and the survival rate of bacteria also significantly the lowest, >20%, when compared to other treatment groups | The production of ROS which rupture the bacterial membrane. | H2O2/VOxNDs can inhibit growth of drug-resistant bacteria |

| 10 | Malmir et al., 2020 [61] | 1. E. coli 2. S. aureus | CQDs | 1. MIC test 2. Characterization of bacterial death | The CQD-TiO2 NPs inhibition zone was seen around S. aureus bacteria but have no effect on E. coli | The production of ROS, | The antibacterial activity of CQD-TiO2 NPs against E. coli was lower than S. aureus |

| 11 | Li et al., 2020 [56] | 1. E. coli 2. S. aureus | CQDs | 1. MIC test 2. Time-kill study 3. Bacterial morphology | The MIC values of CQDs and Arg-CQDs are 62.5 µg/mL and 125 µg/mL for E. coli, respectively, and 31.25 µg/mL and 62.5 µg/mL for S. aureus, respectively. The cellular membrane of the bacteria is disrupted when exposed to treatment. | The electrostatic interaction of positively charged nanoparticles and negatively charged bacteria disrupt the bacterial membrane and the release of ROS. | CQDs show high inhibitory activities for both E. coli and S. aureus |

| No | References | Experimental Model | Type of Quantum Dots | Outcome Measures | Results | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Li et al., 2020 [56] | HUVECs | CQDs | 1. CCK-8 tests 2. Live/dead assay | Cell viability of HUVECs is more than 85% at a concentration of 250 µg/mL | CQDs effectively promote the growth of HUVECs with a high survival rate |

| 2 | Sharma et al., 2019 [70] | HUVECs | CQDs | 1. Cell Proliferation assay 2. In vitro tube formation assay 3. In Ovo angiogenesis assay 4. qPCR | The development of capillary network in HUVECs model has been significantly increased compared to control as well as high expression of VEGF | The CD-urea showed a proangiogenic response in HUVECs model |

| 3 | Zhu et al., 2019 [69] | HUVECs | SeQDs | 1. Quantitative analysis of arteries 2. Protein expression | The treatment group of A-SeQDs have the highest diameter of arteries formed and increase NOS activity and NO production | SeQDs proved to promote angiogenesis properties |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salleh, A.; Fauzi, M.B. The In Vivo, In Vitro and In Ovo Evaluation of Quantum Dots in Wound Healing: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13020191

Salleh A, Fauzi MB. The In Vivo, In Vitro and In Ovo Evaluation of Quantum Dots in Wound Healing: A Review. Polymers. 2021; 13(2):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13020191

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalleh, Atiqah, and Mh Busra Fauzi. 2021. "The In Vivo, In Vitro and In Ovo Evaluation of Quantum Dots in Wound Healing: A Review" Polymers 13, no. 2: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13020191

APA StyleSalleh, A., & Fauzi, M. B. (2021). The In Vivo, In Vitro and In Ovo Evaluation of Quantum Dots in Wound Healing: A Review. Polymers, 13(2), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13020191