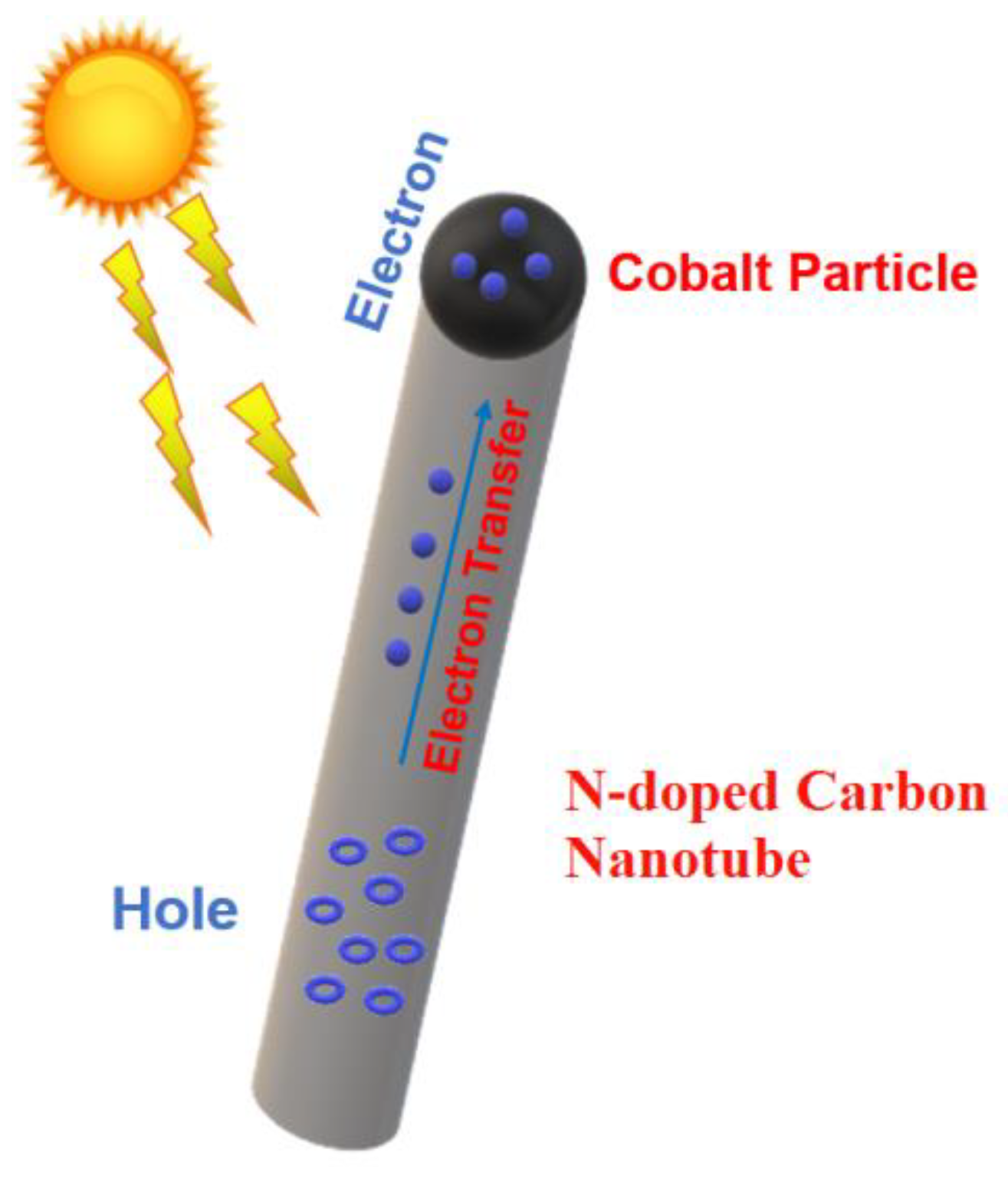

Co(O)x Particles in Polymeric N-Doped Carbon Nanotube Applied for Photocatalytic H2 or Electrocatalytic O2 Evolution

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Photocatalysts Preparation

2.2. Materials and Characterization

2.3. Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production

2.4. Electrocatalytic Oxygen Production

3. Results and Discussion

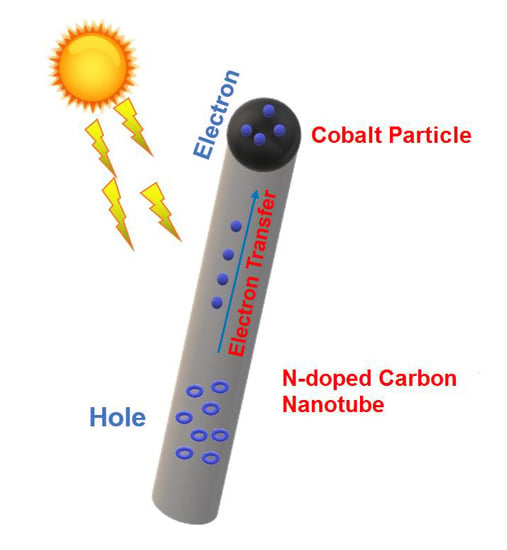

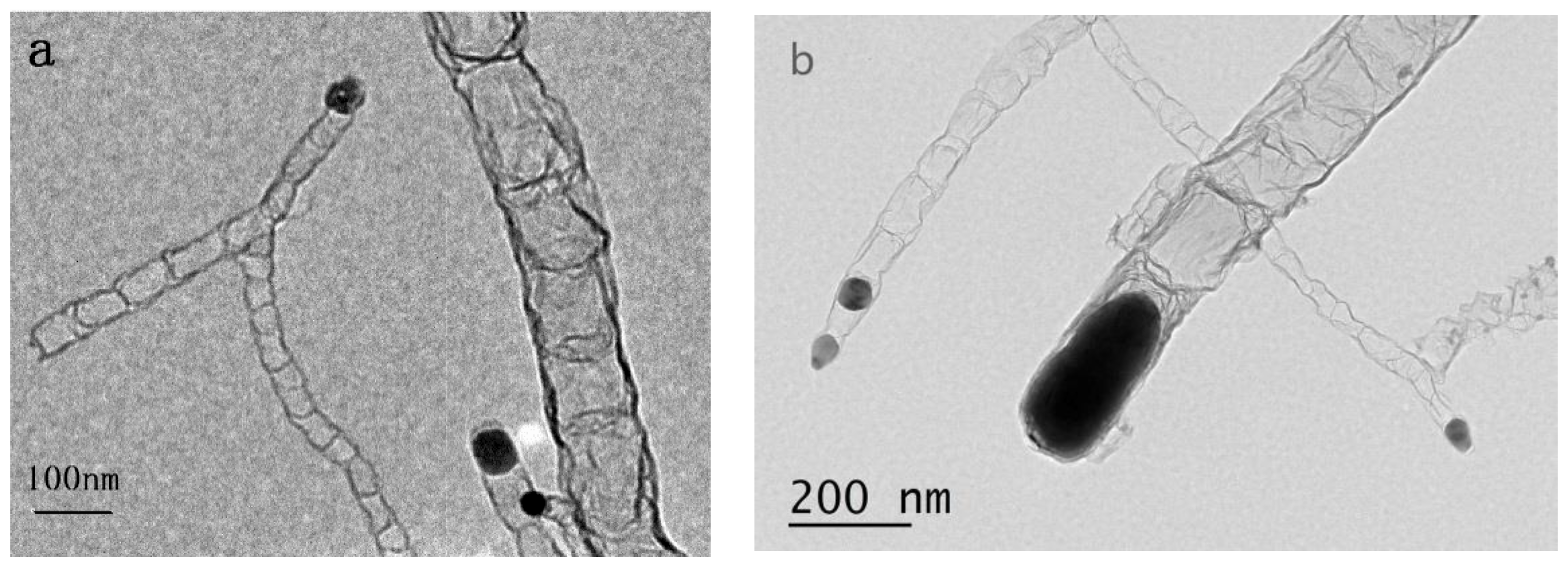

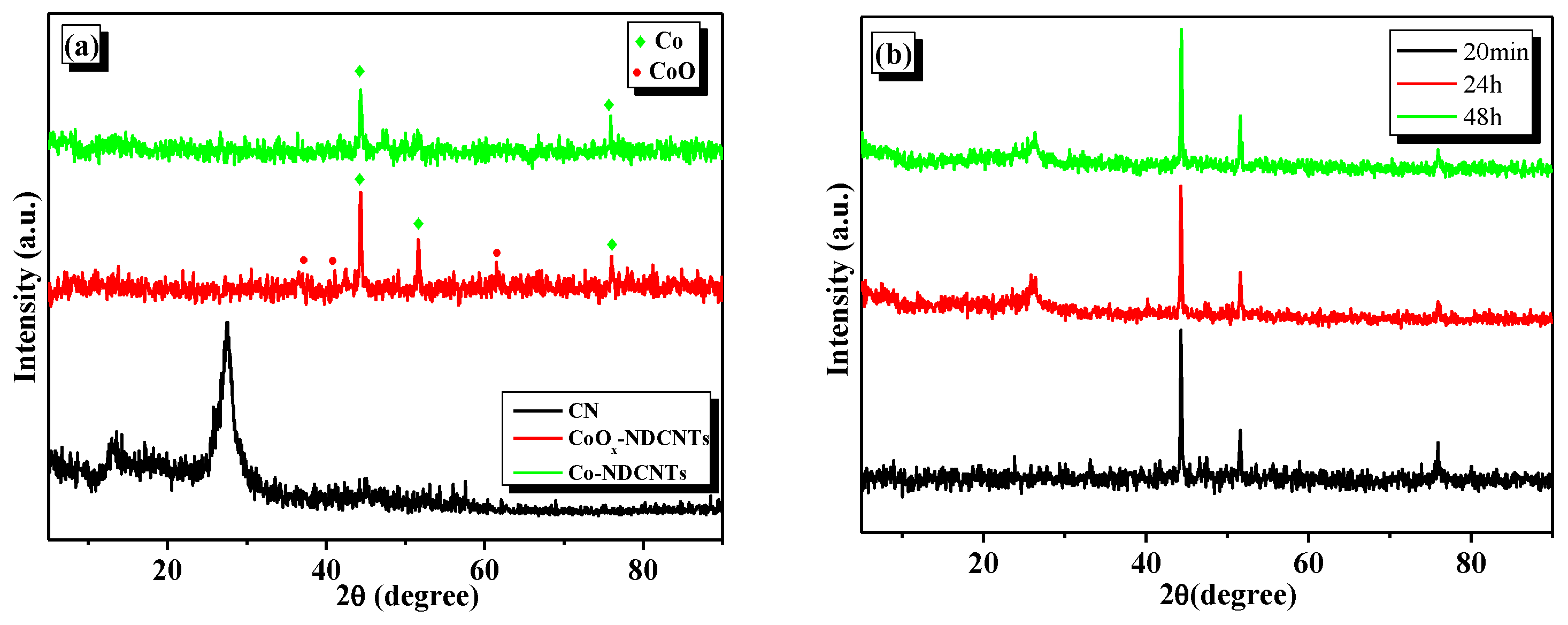

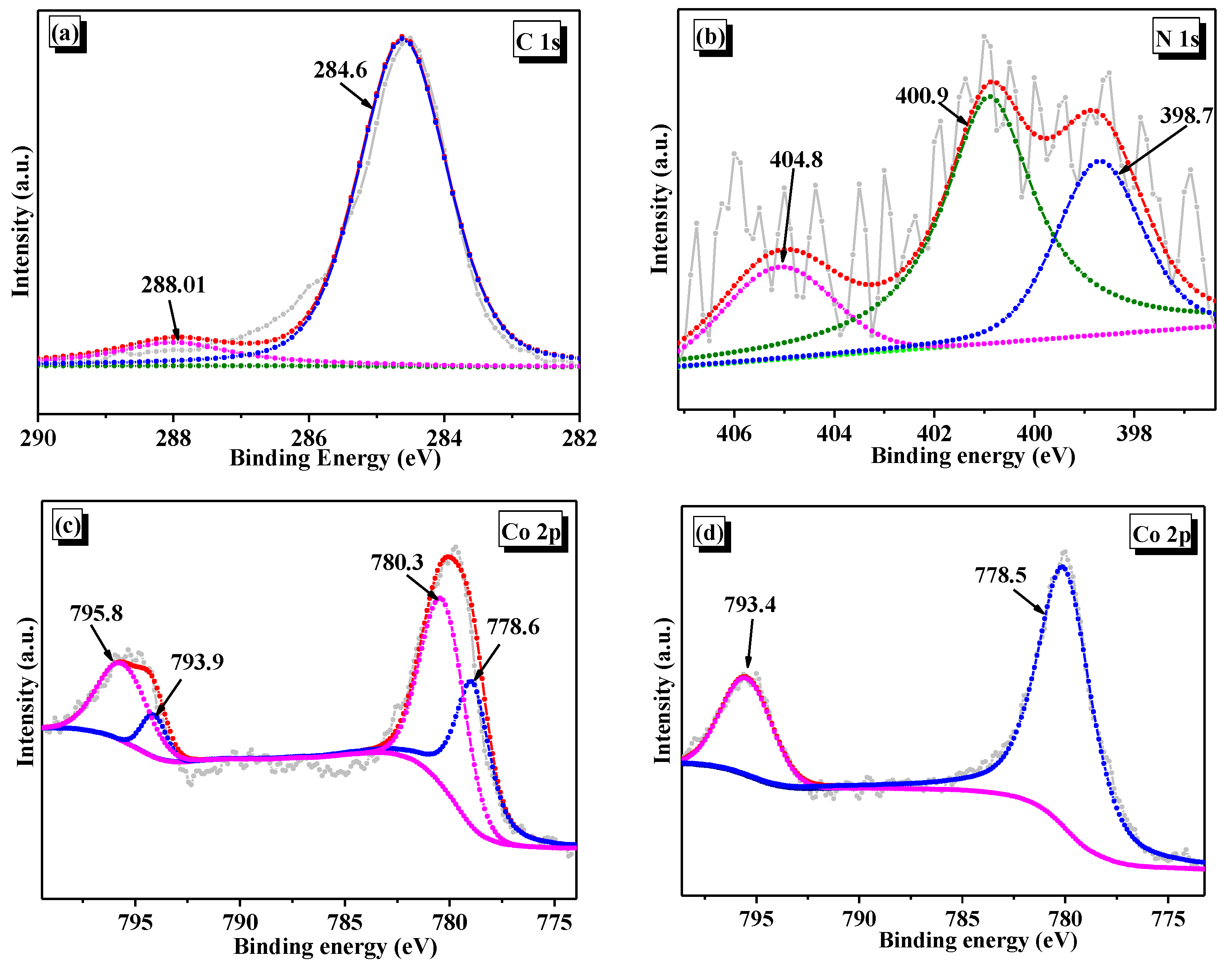

3.1. Morphology and Composition of Catalyst

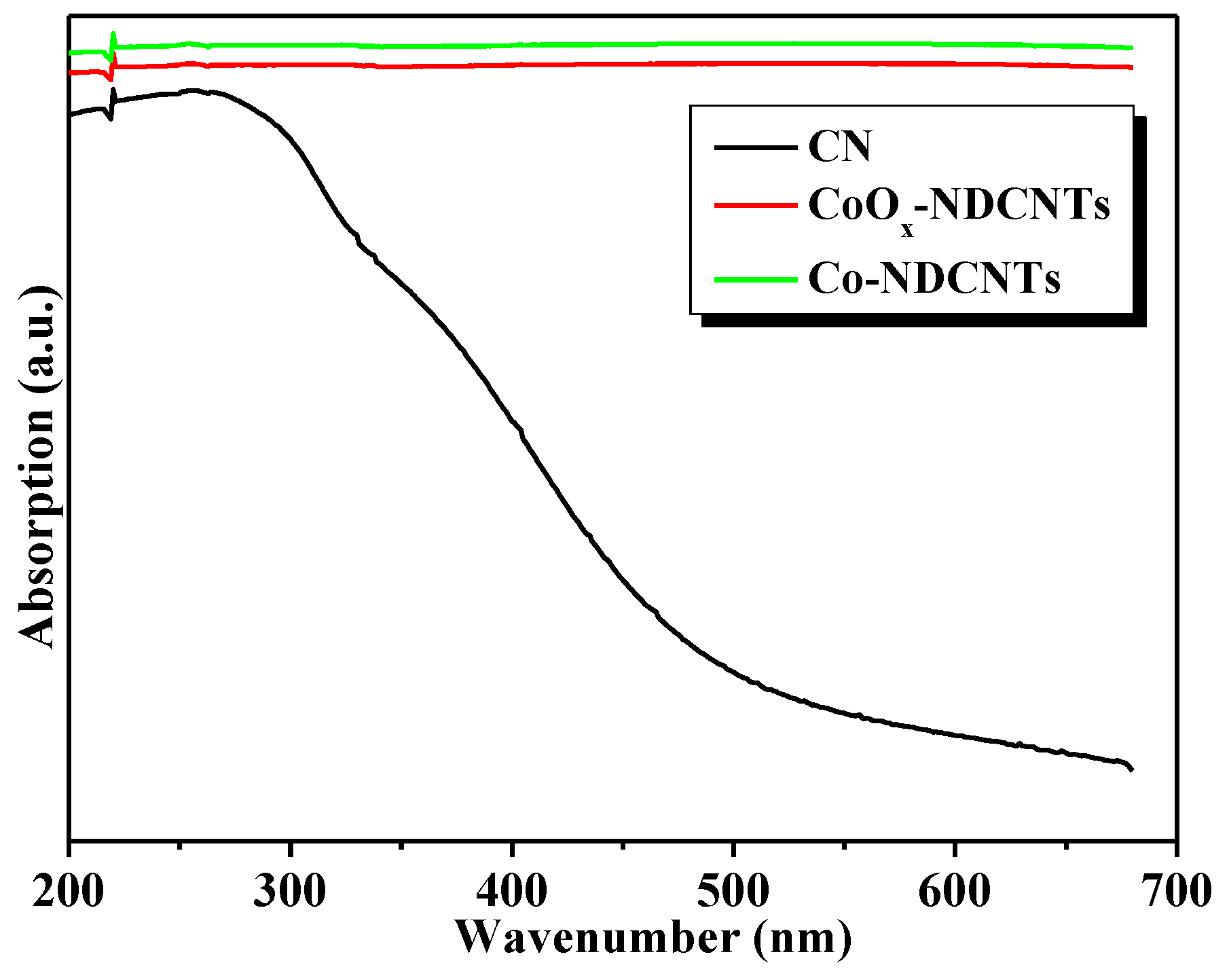

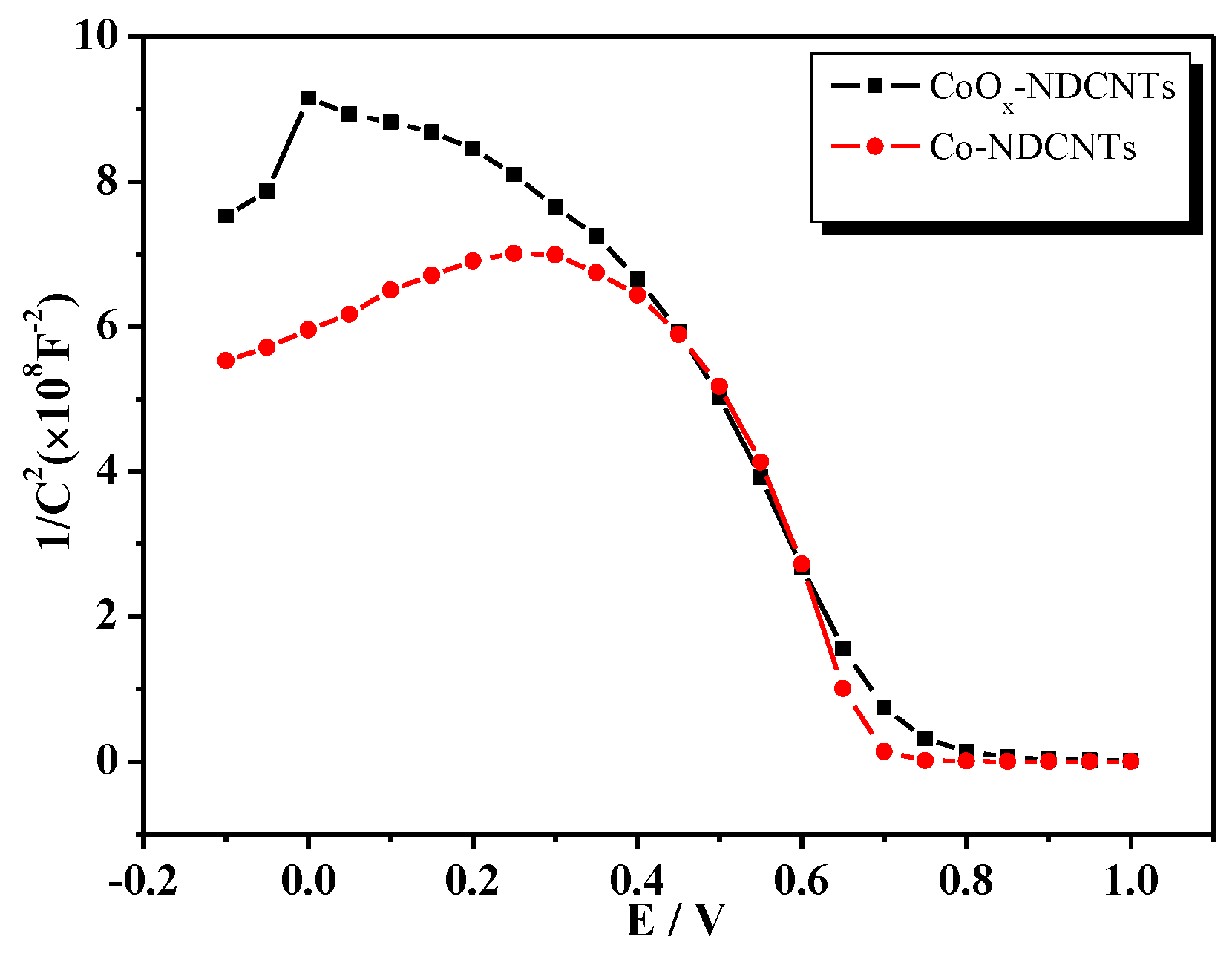

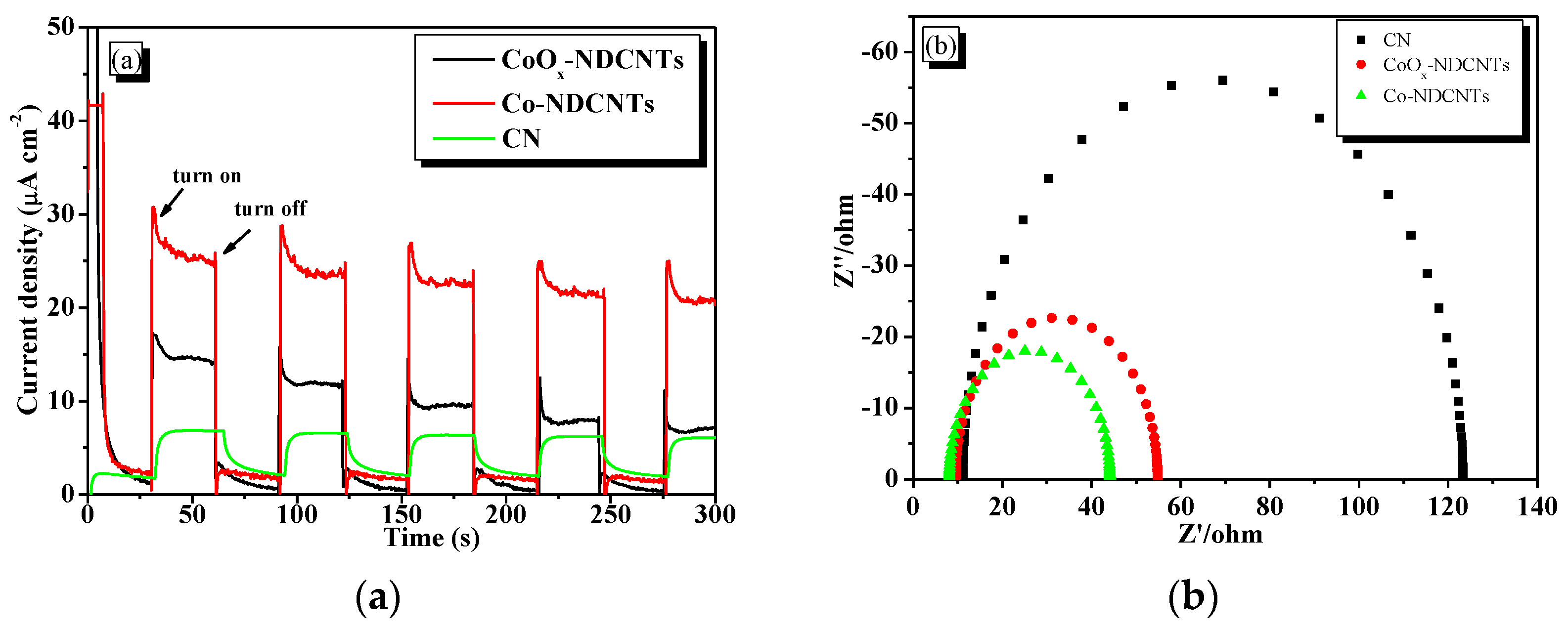

3.2. Optical and Electrochemical Properties of Samples

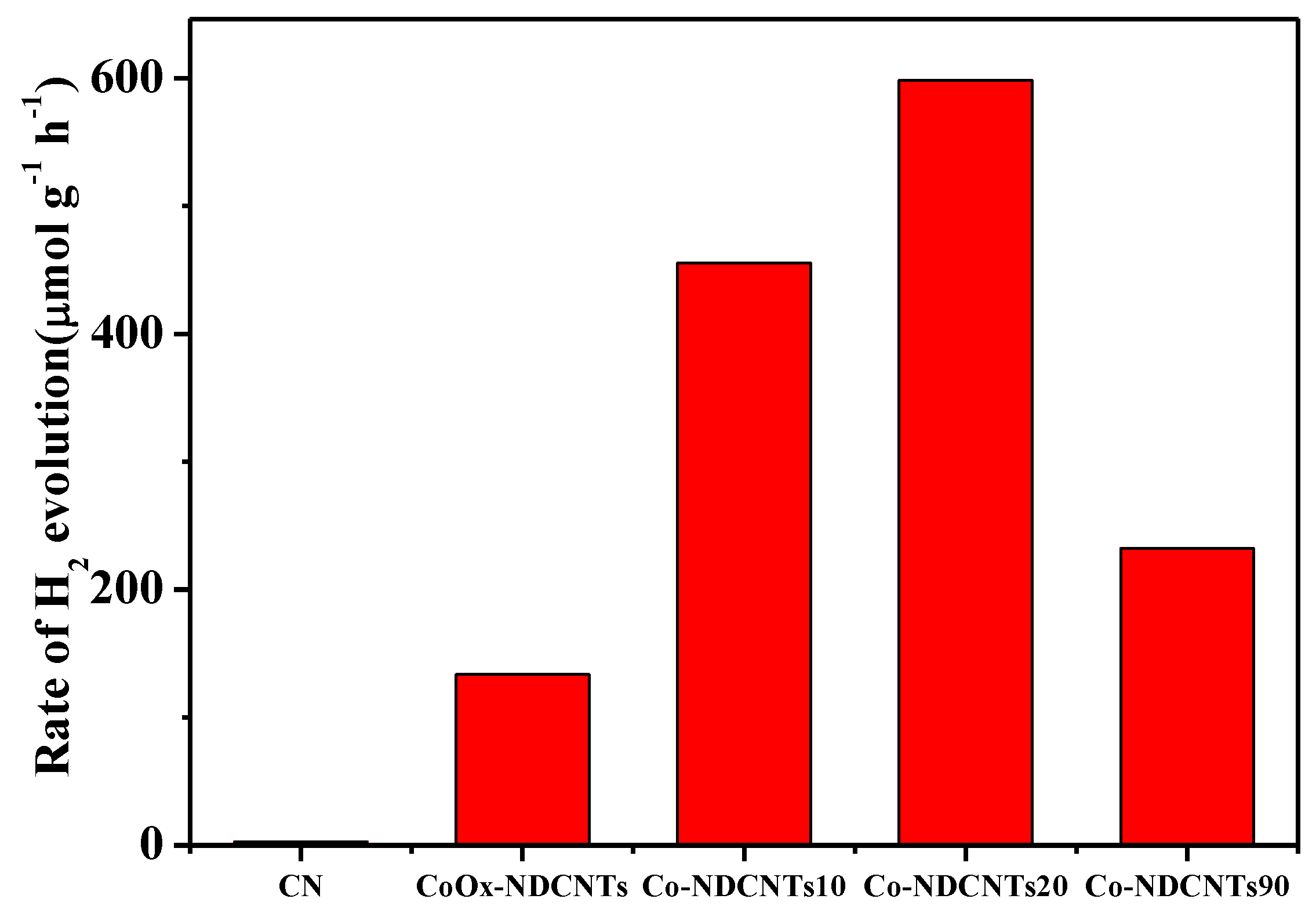

3.3. Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production Activity of Samples

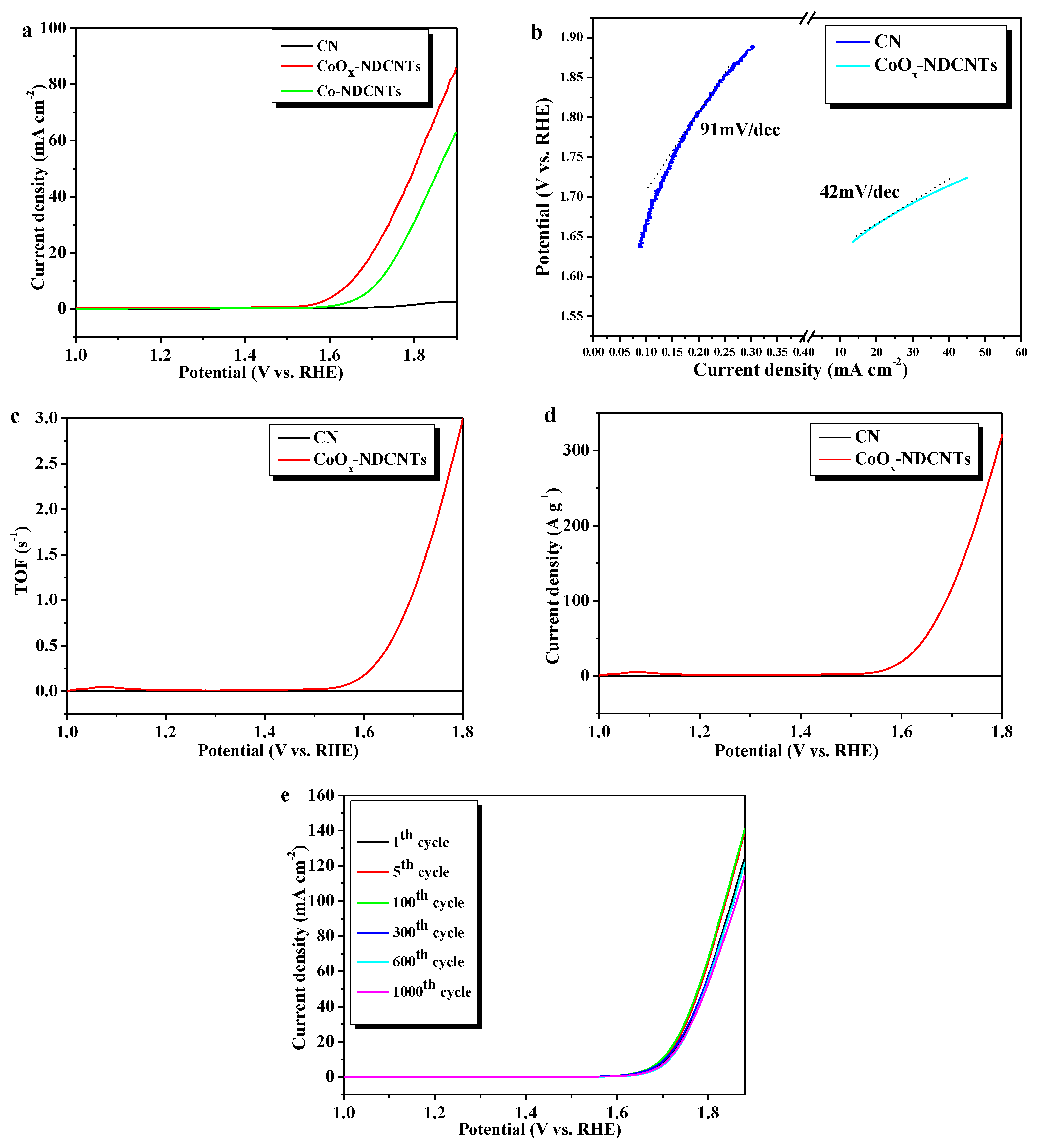

3.4. Electrocatalytic Oxygen Production Activity of Samples

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, X.; Shen, S.; Guo, L.; Mao, S. Semiconductor-based Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6503–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Yu, J.G. Carbon-based H2-production photocatalytic materials. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2016, 27, 72–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, N.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Huang, H.; Lifshitz, Y.; Lee, S.T.; Zhong, J.; Kang, Z. Metal-free efficient photocatalyst for stable visible water splitting via a two-electron pathway. Science 2015, 347, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Huang, F. Black titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanomaterials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 1861–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, S.W.; Ma, Z.; Song, W.G. Preparation and Characterization of Carbon Nitride Nanotubes and Their Applications as Catalyst Supporter. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 8668–8672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S.; Cui, D.; Wang, Q. Synthesis, characterization and electrocatalytic properties of carbon nitride nanotubes for methanol electrooxidation. Solid State Sci. 2009, 11, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tragl, S.; Gibson, K.; Glaser, J.; Duppel, V.; Simon, A.; Meyer, H.J. Template assisted formation of micro-and nanotubular carbon nitride materials. Solid State Commun. 2007, 141, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalom, M.; Inal, S.; Fettkenhauer, C.; Neher, D.; Antonietti, M. Improving Carbon Nitride Photocatalysis by Supramolecular Preorganization of Monomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 7118–7121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.S.; Lee, E.Z.; Wang, X.C.; Hong, W.H.; Stucky, G.D.; Thomas, A. From Melamine-Cyanuric Acid Supramolecular Aggregates to Carbon Nitride Hollow Spheres. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 3661–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.S.; Park, J.; Lee, S.U.; Thomas, A.; Hong, W.H.; Stucky, G.D. Three-dimensional macroscopic assemblies of low-dimensional carbon nitrides for enhanced hydrogen evolutio. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11083–11087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishida, Y.; Chabanne, L.; Antonietti, M.; Shalom, M. Morphology Control and Photocatalysis Enhancement by the One-Pot Synthesis of Carbon Nitride from Preorganized Hydrogen-Bonded Supramolecular Precursors. Langmuir 2014, 30, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Ding, Z.; Fu, X.; Wang, X. Construction of Conjugated Carbon Nitride Nanoarchitectures in Solution at Low Temperatures for Photoredox Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 11814–11818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, G.Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, J.G.; Wu, S.J.; Yan, W.F.; Liu, G. Plasmonic Au nanoparticles embedding enhances the activity and stability of CdS for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, K.; Tang, H.J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, C.G.; Liu, W.; Gao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Tang, Z.Y. New Insight into the Role of Gold Nanoparticles in Au@CdS Core-Shell Nanostructures for Hydrogen Evolution. Small 2015, 10, 4664–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinh, C.T.; Yen, H.; Kleitz, F.; Do, T.O. Three-Dimensional Ordered Assembly of Thin-Shell Au/TiO2 Hollow Nanospheres for Enhanced Visible-Light-Driven Photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6618–6623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.K.; Xu, Q. Functional materials derived from open framework templates/precursors: synthesis and applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2071–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaikittisilp, W.; Ariga, K.; Yamauchi, Y. A new family of carbon materials: synthesis of MOF-derived nanoporous carbons and their promising applications. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Reboul, J.; Furukawa, S.; Radhakrishnan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Srinivasu, P.; Iwai, H.; Wang, H.; Nemoto, Y.; Suzuki, N.; et al. Direct synthesis of nanoporous carbon nitride fibers using Al-based porous coordination polymers (Al-PCPs). Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8124–8126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Takata, T.; Hara, M.; Saito, N.; Inoue, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Domen, K. GaN:ZnO Solid Solution as a Photocatalyst for Visible-Light-Driven Overall Water Splitting. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8286–8287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Teramura, K.; Lu, D.; Takata, T.; Saito, N.; Inoue, Y.; Domen, K. Photocatalyst releasing hydrogen from water. Nature 2006, 440, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, L.; Han, C.C.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.F. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of novel polymeric g-C3N4 loaded with Ag nanoparticles. Appl. Catal. A 2011, 409, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajyothi, P.C.; Pandurangan, M.; Vattikuti, S.V.P.; Tettey, C.O.; Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Shim, J. Enhanced photocatalytic activity of Ag/g-C3N4 composite. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2017, 188, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.F.; Zhang, J.S.; Fu, X.Z.; Antonietti, M.; Wang, X.C. Fe-g-C3N4-Catalyzed Oxidation of Benzene to Phenol Using Hydrogen Peroxide and Visible Light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 11658–11659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, B.; Li, Q.Y.; Iwai, H.; Kako, T.; Ye, J.H. Polymeric Carbon Nitrides: Semiconducting Properties and Emerging Applications in Photocatalysis and Photoelectrochemical Energy Conversion. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2012, 4, 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.A.; Overbury, S.H.; Dudney, N.J.; Li, M.; Veith, G.M. Gold Nanoparticles Supported on Carbon Nitride: Influence of Surface Hydroxyls on Low Temperature Carbon Monoxide Oxidation. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 1138–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.C.; Li, Z.S.; Zou, Z.G. Photodegradation of Rhodamine B and Methyl Orange over Boron-Doped g-C3N4 under Visible Light Irradiation. Langmuir 2010, 26, 3894–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Niu, P.; Sun, C.H.; Smith, S.C.; Chen, Z.G.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.M. Unique Electronic Structure Induced High Photoreactivity of Sulfur-Doped Graphitic C3N4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 11642–11648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Mori, T.; Ye, J.H.; Antonietti, M. Phosphorus-Doped Carbon Nitride Solid: Enhanced Electrical Conductivity and Photocurrent Generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6294–6295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.S.; Wang, X.C.; Antonietti, M.; Li, H.R. Boron-and Fluorine-Containing Mesoporous Carbon Nitride Polymers: Metal-Free Catalysts for Cyclohexane Oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 3356–3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Shi, R.; Lin, J.; Zhu, Y.F. Enhancement of photocurrent and photocatalytic activity of ZnO hybridized with graphite-like C3N4. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 2922–2929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Bai, X.J.; Pan, C.S.; He, J.; Zhu, Y.F. Enhancement of photocatalytic activity of Bi2WO6 hybridized with graphite-like C3N4. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 11568–11573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.C.; Lv, S.B.; Li, Z.S.; Zou, Z.G. Organic–inorganic composite photocatalyst of g-C3N4 and TaON with improved visible light photocatalytic activities. Dalton Trans. 2010, 39, 1488–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagajyothi, P.C.; Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Ramaraghavulu, R.; Devarayapalli, K.C.; Yoo, K.; Prabhakar Vattikuti, S.V.; Shim, J. Photocatalytic dye degradation and hydrogen production activity of Ag3PO4/g-C3N4 nanocatalyst. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 14890–14901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Liu, Q.; Ge, C.J.; Cui, W.; Pu, Z.H.; Asiri, A.M.; Sun, X.P. CoP nanostructures with different morphologies: synthesis, characterization and a study of their electrocatalytic performance toward the hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 14634–14640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajyoyhi, P.C.; Devarayapalli, K.C.; Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Prabhakar Vattikuti, S.V.; Shim, J. Effective catalytic degradation of Rhodamine B using ZnCO2O4 nanodice. Mater. Res. Express. 2019, 6, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekanth, T.V.M.; Ramaraghavulub, R.; Prabhakar Vattikuti, S.V.; Shim, J.; Yoo, K. Microwave synthesis: ZnCo2O4 NPs as an efficient electrocatalyst in the methanol oxidation reaction. Mater. Lett. 2019, 253, 450–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Meng, Y.; Mao, X.; Ning, X.M.; Zhang, Z.; Shan, D.L.; Chen, J.; Lu, X.Q. New insight into enhanced photocatalytic activity of morphology-dependent TCPP-AGG/RGO/Pt composites. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 282, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin-Phillipp, N.Y.; Krauss, T.N.; van Aken, P.A. The Growth of One-Dimensional CuPcF16 Nanostructures on Gold Nanoparticles as Studied by Transmission Electron Microscopy Tomography. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 4039–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Cao, R.; Wang, J.; Bai, F.; Fan, H. Self-Assembled One-Dimensional Porphyrin Nanostructures with Enhanced Photocatalytic Hydrogen Generation. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.P.; Xu, H.; Qian, X.F.; Dong, Y.Y.; Gao, J.K.; Qian, G.D.; Yao, G.M. Direct Synthesis of Porous Nanorod-Type Graphitic Carbon Nitride/CuO Composite from Cu-Melamine Supramolecular Framework towards Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance. Chem. Asian J. 2015, 10, 1276–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.K.; Wang, J.P.; Qian, X.F.; Dong, Y.Y.; Xu, H.; Song, R.J.; Yan, C.F.; Zhu, H.C.; Zhong, Q.W.; Qian, G.D.; et al. One-pot synthesis of copper-doped graphitic carbon nitride nanosheet by heating Cu–melamine supramolecular network and its enhanced visible-light-driven photocatalysis. J. Solid State Chem. 2015, 228, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.C.; Antonietti, M. Polymeric Graphitic Carbon Nitride as a Heterogeneous Organocatalyst: From Photochemistry to Multipurpose Catalysis to Sustainable Chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Peng, L.; Liu, K.; Garcia, H.; Sun, C.Z.; Dong, L. Cobalt nanoparticle with tunable size supported on nitrogen-deficient graphitic carbon nitride for efficient visible light driven H2 evolution reaction. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 381, 122576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chen, C.H.; Shui, J.L.; Xie, S. Nickel-Foam-Supported Reticular CoO–Li2O Composite Anode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 117, 7247–7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Long, J.; Liang, J.; Lin, H.; Lin, H.; Wang, X. Vacuum heat-treatment of carbon nitride for enhancing photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 17797–17807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.J.; Yu, J.G.; Jaroniec, M. Preparation and Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic H2-Production Activity of Graphene/C3N4 Composites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 7355–7363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.G.; Wang, S.H.; Cheng, B.; Lin, Z.; Huang, F. Noble metal-free Ni(OH)2–g-C3N4 composite photocatalyst with enhanced visible-light photocatalytic H2-production activity. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2013, 3, 1782–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, G.H.; Zhang, L.Z. Porous structure dependent photoreactivity of graphitic carbon nitride under visible light. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ma, L.; Ning, L.; Zhang, C.; Han, G.; Pei, C.; Zhao, H.; Liu, S.; Yang, H. Charge Separation between Polar {111} Surfaces of CoO Octahedrons and Their Enhanced Visible-Light Photocatalytic Activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6109–6117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhang, L. Incorporation of CoO nanoparticles in 3D marigold flower-like hierarchical architecture MnCo2O4 for highly boosting solar light photo-oxidation and reduction ability. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 237, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Z.; Wang, W.; Dong, S.; He, J. Well-distributed cobalt-based catalysts derived from layered double hydroxides for efficient selective hydrogenation of 5-hydroxymethyfurfural to 2,5-methylfuran. Catal. Today 2019, 319, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellal, B.; Saadi, S.; Koriche, N.; Bouguelia, A.; Trari, M. Physical properties of the delafossite LaCuO2. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2009, 70, 1132–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Shao, M.F.; Ning, F.Y.; Xu, S.M.; Li, Z.H.; Wei, M.; Evans, D.G.; Duan, X. Au nanoparticles sensitized ZnO nanorod@nanoplatelet core–shell arrays for enhanced photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nano Energy 2015, 12, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.Z.; Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Zheng, X.X.; Zou, W.X.; Dong, L.; Qi, L. Enhanced activity of visible-light photocatalytic H2 evolution of sulfur-doped g-C3N4 photocatalyst via nanoparticle metal Ni as cocatalyst doped g-C3N4 photocatalyst via nanoparticle metal Ni as cocatalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 235, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zhao, X.U.; Liu, H. Visible-light sensitive cobalt-doped BiVO4 (Co-BiVO4) photocatalytic composites for the degradation of methylene blue dye in dilute aqueous solutions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2010, 99, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Q.; Ma, M.Y.; Cui, G.W.; Shi, X.F.; Han, F.Y.; Xia, X.Y.; Tang, B. A new strategy to realize efficient spacial charge separation on carbonaceous photocatalyst. Carbon 2014, 73, 333–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.F.; Wang, R.; Bao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, S.; Xie, Y. Zirconium trisulfide ultrathin nanosheets as efficient catalysts for water oxidation in both alkaline and neutral solutions. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2014, 1, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Sheng, W.; Zhuang, Z.; Fang, Q.; Gu, S.; Jiang, J.; Yan, Y. Efficient Water Oxidation Using Nanostructured α-Nickel-Hydroxide as an Electrocatalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 7077–7084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, S.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, B.; Yang, H. Electrochemical etching of α-cobalt hydroxide for improvement of oxygen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 9578–9584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, X.; Liu, K.; Chen, L.; He, H.; Chen, L.; Sun, C. Co(O)x Particles in Polymeric N-Doped Carbon Nanotube Applied for Photocatalytic H2 or Electrocatalytic O2 Evolution. Polymers 2019, 11, 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111836

Zheng X, Liu K, Chen L, He H, Chen L, Sun C. Co(O)x Particles in Polymeric N-Doped Carbon Nanotube Applied for Photocatalytic H2 or Electrocatalytic O2 Evolution. Polymers. 2019; 11(11):1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111836

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Xiaoxue, Ke Liu, Lichao Chen, Hengxiao He, Lusheng Chen, and Chuanzhi Sun. 2019. "Co(O)x Particles in Polymeric N-Doped Carbon Nanotube Applied for Photocatalytic H2 or Electrocatalytic O2 Evolution" Polymers 11, no. 11: 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111836

APA StyleZheng, X., Liu, K., Chen, L., He, H., Chen, L., & Sun, C. (2019). Co(O)x Particles in Polymeric N-Doped Carbon Nanotube Applied for Photocatalytic H2 or Electrocatalytic O2 Evolution. Polymers, 11(11), 1836. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11111836