Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance of Te-Doped Bi2Se3−xTex Bulks by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedures

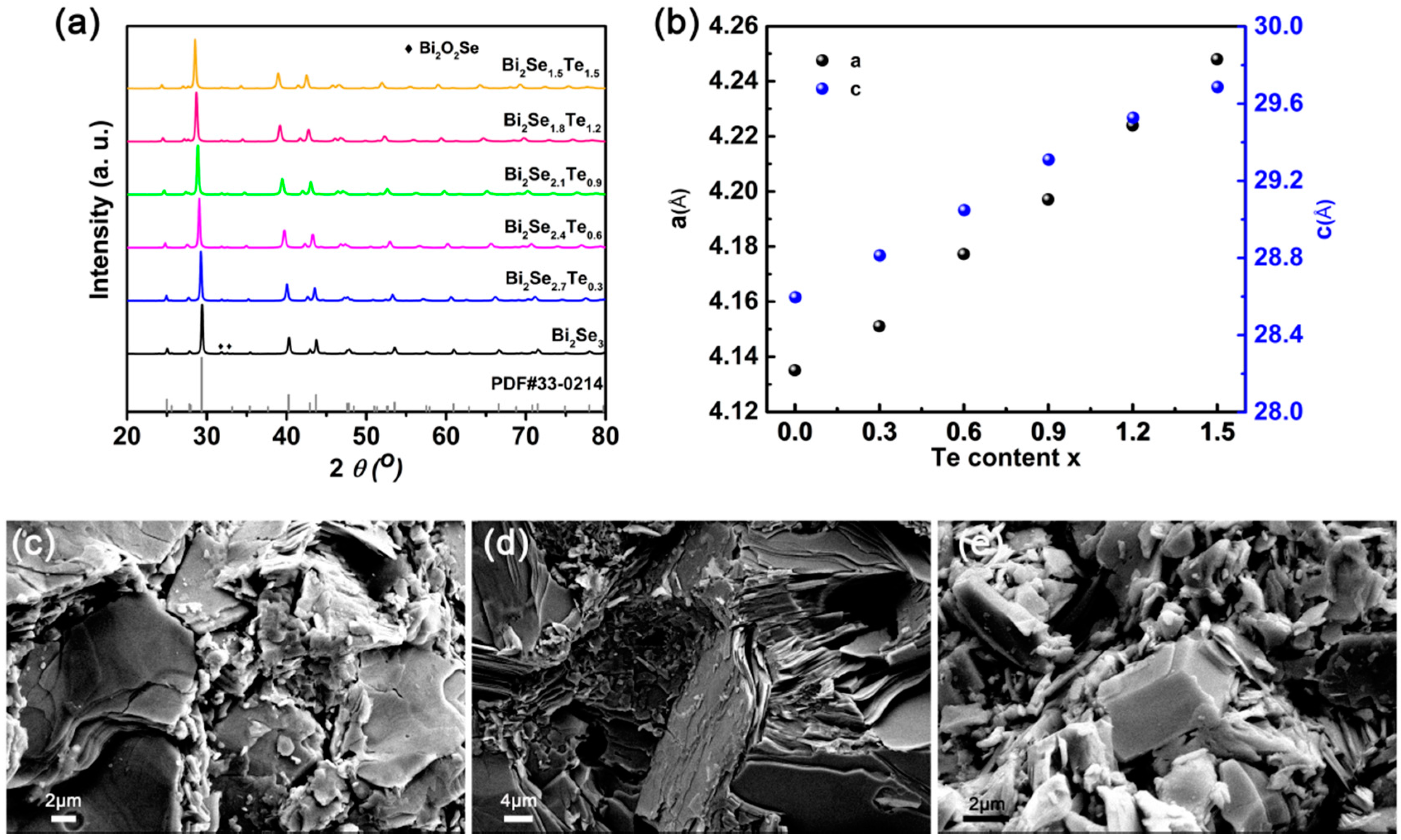

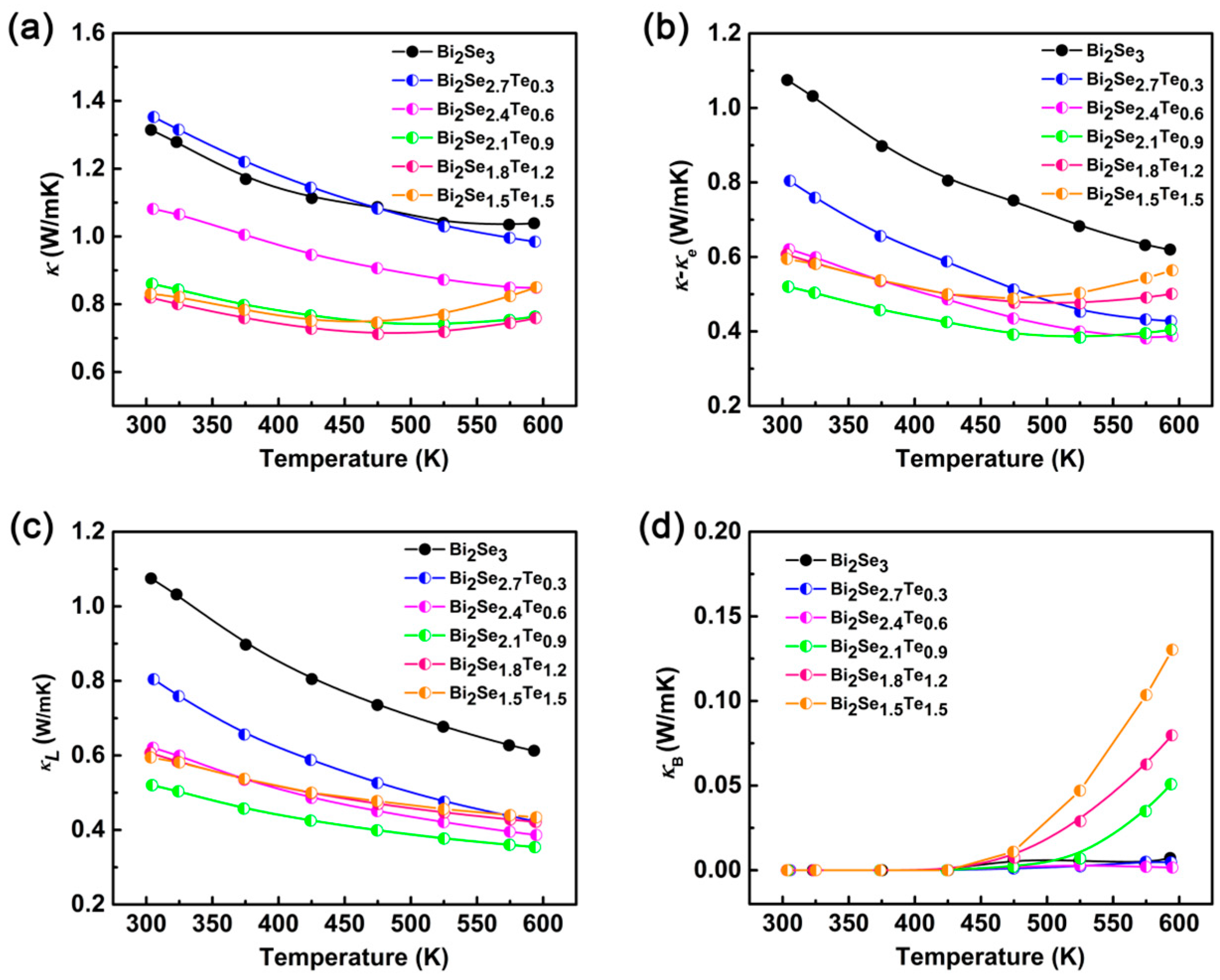

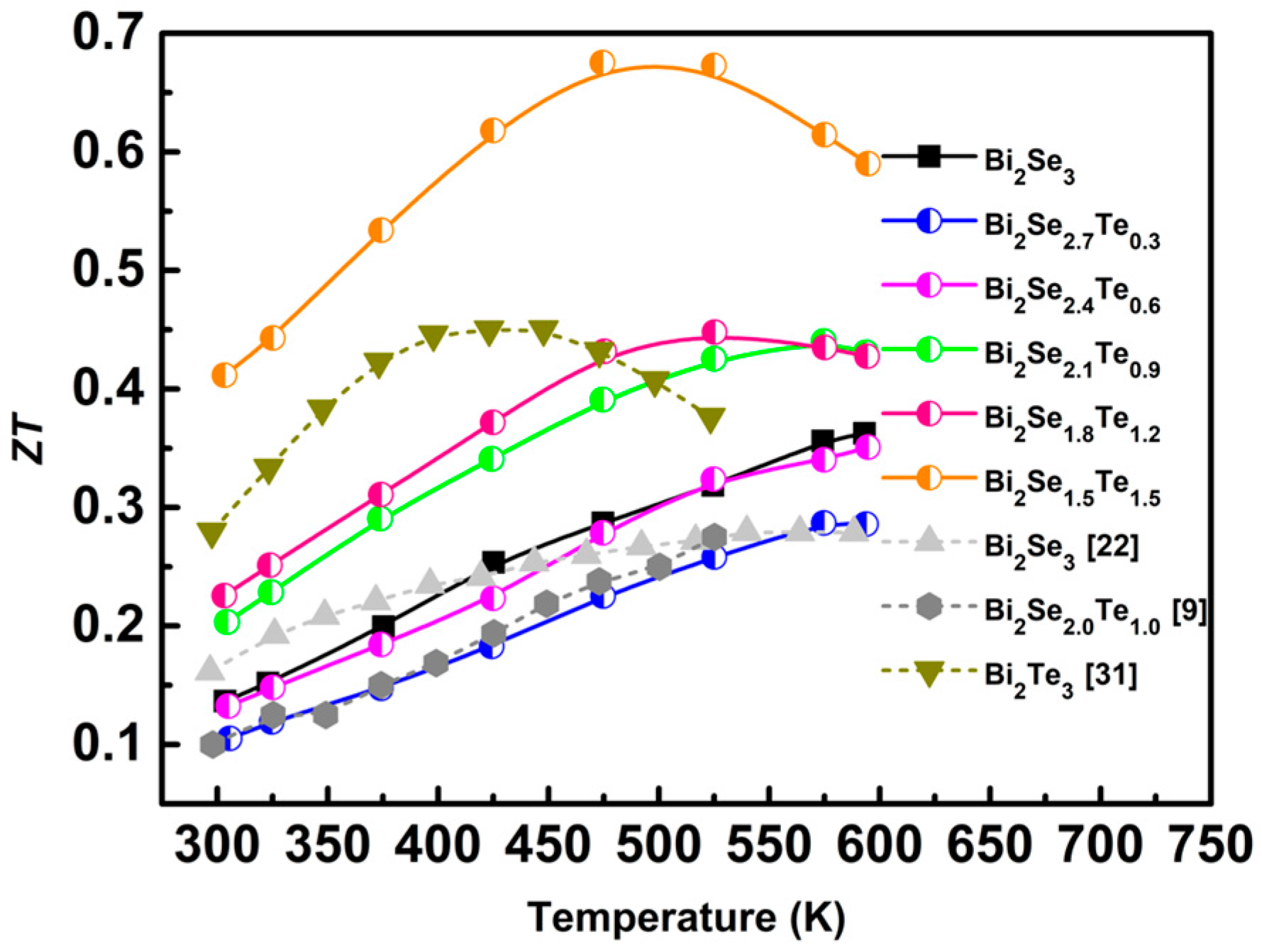

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, S.H.; Zhu, T.J.; Sun, T.; He, J.; Zhang, S.N.; Zhao, X.B. Nanostructures in high-performance (GeTe)x(AgSbTe2)100−x thermoelectric materials. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 245707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, L.E. Cooling, heating, generating power, and recovering waste heat with thermoelectric systems. Science 2008, 321, 1457–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tritt, T.M. Holey and unholey semiconductors. Science 1999, 283, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhyee, J.S.; Lee, K.H.; Lee, S.M.; Cho, E.; Kim, S.I.; Lee, E.; Kwon, Y.S.; Shim, J.H.; Kotliar, G. Peierls distortion as a route to high thermoelectric performance in In4Se3−δ crystals. Nature 2009, 459, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolas, G.S.; Sharp, J.; Goldsmid, J. Thermoelectrics: Basic Principles and New Materials Developments; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; Volume 45, p. 111. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, G.J.; Toberer, E.S. Complex thermoelectric materials. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Karthik, C.; Singh, B.; Siegel, R.W.; Borca-Tasciuc, T.; Ramanath, G. A new class of doped nanobulk high-figure-of-merit thermoelectrics by scalable bottom-up assembly. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, X.; Lan, J.L.; Ren, G.K.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Nan, C.W. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of n-type Bi2O2Se by Cl-doping at Se site. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2017, 100, 1494–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.S.; Lukas, K.C.; McEnaney, K.; Lee, S.; Zhang, Q.; Opeil, C.P.; Chen, G.; Ren, Z.F. Studies on the Bi2Te3–Bi2Se3–Bi2S3 system for mid-temperature thermoelectric energy conversion. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 552–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.S.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Lan, Y.C.; Chen, S.; Yan, X.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, H.; Wang, D.Z.; Chen, G.; Ren, Z.F. Thermoelectric property studies on Cu-doped n-type CuxBi2Te2.7Se0.3 nanocomposites. Adv. Energy Mater. 2011, 1, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.Z.; Shi, X.Y.; Lalonde, A.; Wang, H.; Chen, L.D.; Snyder, G.J. Convergence of electronic bands for high performance bulk thermoelectrics. Nature 2011, 473, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, L.D.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Thermoelectric figure of merit of a one-dimensional conductor. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 47, 16631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, T.E.; Linke, H. Reversible Thermoelectric Nanomaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 096601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biswa, K.; He, J.Q.; Blum, I.D.; Wu, C.I.; Hogan, T.P.; Seidman, D.D.; Dravid, V.P.; Kanatzidis, M.G. High-performance bulk thermoelectrics with all-scale hierarchical architectures. Nature 2012, 489, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dresselhaus, M.S.; Chen, G.; Tang, M.Y.; Yang, R.; Lee, H.; Wang, D.; Ren, Z.; Fleurial, J.P.; Gogna, P. New directions for low-dimensional thermoelectric materials. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Dresselhaus, M.; Dresselhaus, G.; Fleurial, J.P.; Caillat, T. Recent developments in thermoelectric materials. Int. Mater. Rev. 2003, 48, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauzlarich, S.M.; Brown, S.R.; Snyder, G.J. Zintl phases for thermoelectric devices. Dalton Trans. 2007, 21, 2099–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Sato, N.; Miyaoko, S. New optical recording material for video disc system. J. Appl. Phys. 1983, 54, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, J.; Crouch, D.; Raftery, J.; O’Brien, P. Deposition of bismuth chalcogenide thin films using novel single-source precursors by metal-organic chemical vapor deposition. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 3289–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayaz, A.A.; Giani, A.; Foucaran, A.; Pascal-Delannoy, F.; Boyer, A. Electrical and thermoelectrical properties of Bi2Se3 grown by metal organic chemical vapour deposition technique. Thin Solid Films 2003, 441, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.L.; Hu, L.P.; Zhu, T.J.; Liu, X.H.; Zhao, X.B. High performance n-type bismuth telluride based alloys for mid-temperature power generation. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 10597–10603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.L.; Qin, X.Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, J.; Ren, B.J.; Zou, T.H.; Xin, H.X.; Paschen, S.B.; Yan, X.L. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of n-type Bi2Se3 doped with Cu. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 639, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Syers, P.; Butch, N.P.; Paglione, J.; Fuhrer, M.S. Ambipolar surface state thermoelectric power of topological insulator Bi2Se3. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 1701–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, S. The crystal structure of Bi2Te3−xSex. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1963, 24, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, L.D.; Yao, Q.; Bai, S.Q.; Wang, Q. Effect of TeI4 content on the thermoelectric properties of n-type Bi–Te–Se crystals prepared by zone melting. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005, 92, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadel, K.; Kumari, L.; Li, W.Z.; Huang, Y.Y.; Provencio, P.P. Synthesis and thermoelectric properties of Bi2Se3 nanostructures. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Fu, F.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, G.; Liang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, X.; Yang, D.; Chi, H.; Tang, X.; et al. Self-propagating high-temperature synthesis for compound thermoelectrics and new criterion for combustion processing. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, G.K.; Lan, J.L.; Butt, S.; Ventura, K.J.; Lin, Y.H.; Nan, C.W. Enhanced thermoelectric properties in Pb-doped BiCuSeO oxyselenides prepared by ultrafast synthesis. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 69878–69885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Ren, G.K.; Tan, X.; Lin, Y.L.; Nan, C.W. Enhanced thermoelectric properties of Cu3SbSe3-based composites with inclusion phases. Energies 2016, 9, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.W.; Su, X.L.; Yan, Y.G.; Hu, T.Z.; Xie, H.Y.; He, J.; Uher, C.; Kanatzidis, M.G.; Tang, X.F. Manipulating the combustion wave during self-Propagating synthesis for high thermoelectric performance of layered oxychalcogenide Bi1−xPbxCuSeO. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 4628–4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Su, X.L.; Liang, T.; Lu, Q.B.; Yan, Y.G.; Uher, C.; Tang, X.F. High thermoelectric performance of mechanically robust n-type Bi2Te3−xSex prepared by combustion synthesis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2015, 3, 6603–6613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumoto, K.; Funahashi, R.; Guilmeau, E.; Miyazaki, Y.; Weidenkaff, A.; Wang, Y.F.; Wan, C.L. Thermoelectric ceramics for energy harvesting. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.L.; He, J.; Li, J.F.; Li, F.; Liu, Q.J.; Pan, W.; Barreteau, C.; Berardan, D.; Dragoe, N.; Zhao, L.D. High thermoelectric performance of oxyselenides: Intrinsically low thermal conductivity of Ca-doped BiCuSeO. NPG Asia Mater. 2013, 5, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.S.; Prasad, G.; Pohl, R.O. Experimental determinations of the Lorenz number. J. Mater. Sci. 1993, 28, 4261–4272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamuddin, M.; Dupre, A. Thermoelectric properties of p-type Bi2Te3-Sb2Te3-Sb2Se3 alloys and n-type Bi2Te3-Bi2Se3 alloys in the temperature range 300 to 600 K. Phys. Status Solidi A 1972, 10, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| x | n (1018 cm−3) | μ (cm2 V−1 s−1) | m*/m0 | S (μV K−1) | L (10−8 V2 K−2) | κL (Wm−1 K−1) | κL/κ | Density (g cm−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 5.94 | 444.48 | 0.19 | −118.23 | 1.83 | 1.07 | 81.7% | 7.01 |

| 0.3 | 17.31 | 309.19 | 0.25 | −73.65 | 2.06 | 0.80 | 59.4% | 6.92 |

| 0.6 | 21.94 | 209.36 | 0.31 | −79.95 | 2.03 | 0.62 | 57.4% | 6.77 |

| 0.9 | 24.42 | 149.33 | 0.45 | −107.68 | 1.88 | 0.52 | 60.4% | 6.65 |

| 1.2 | 24.37 | 97.45 | 0.53 | −126.49 | 1.81 | 0.60 | 74.0% | 6.83 |

| 1.5 | 20.73 | 134.96 | 0.60 | −158.72 | 1.71 | 0.59 | 71.6% | 6.96 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, R.; Tan, X.; Ren, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, C.; Lin, Y.; Nan, C. Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance of Te-Doped Bi2Se3−xTex Bulks by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. Crystals 2017, 7, 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst7090257

Liu R, Tan X, Ren G, Liu Y, Zhou Z, Liu C, Lin Y, Nan C. Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance of Te-Doped Bi2Se3−xTex Bulks by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. Crystals. 2017; 7(9):257. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst7090257

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Rui, Xing Tan, Guangkun Ren, Yaochun Liu, Zhifang Zhou, Chan Liu, Yuanhua Lin, and Cewen Nan. 2017. "Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance of Te-Doped Bi2Se3−xTex Bulks by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis" Crystals 7, no. 9: 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst7090257

APA StyleLiu, R., Tan, X., Ren, G., Liu, Y., Zhou, Z., Liu, C., Lin, Y., & Nan, C. (2017). Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance of Te-Doped Bi2Se3−xTex Bulks by Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis. Crystals, 7(9), 257. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst7090257