Theories on Frustrated Electrons in Two-Dimensional Organic Solids

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Physics Relevant in Two Dimensional Organic Crystals

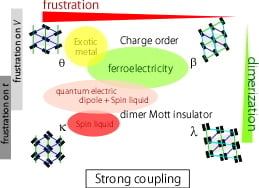

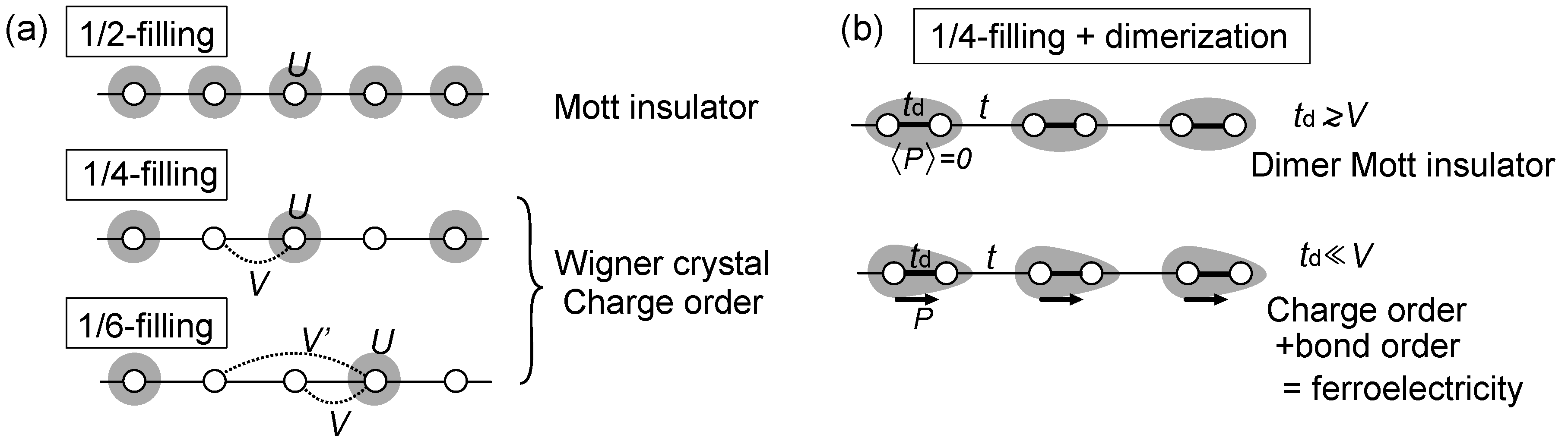

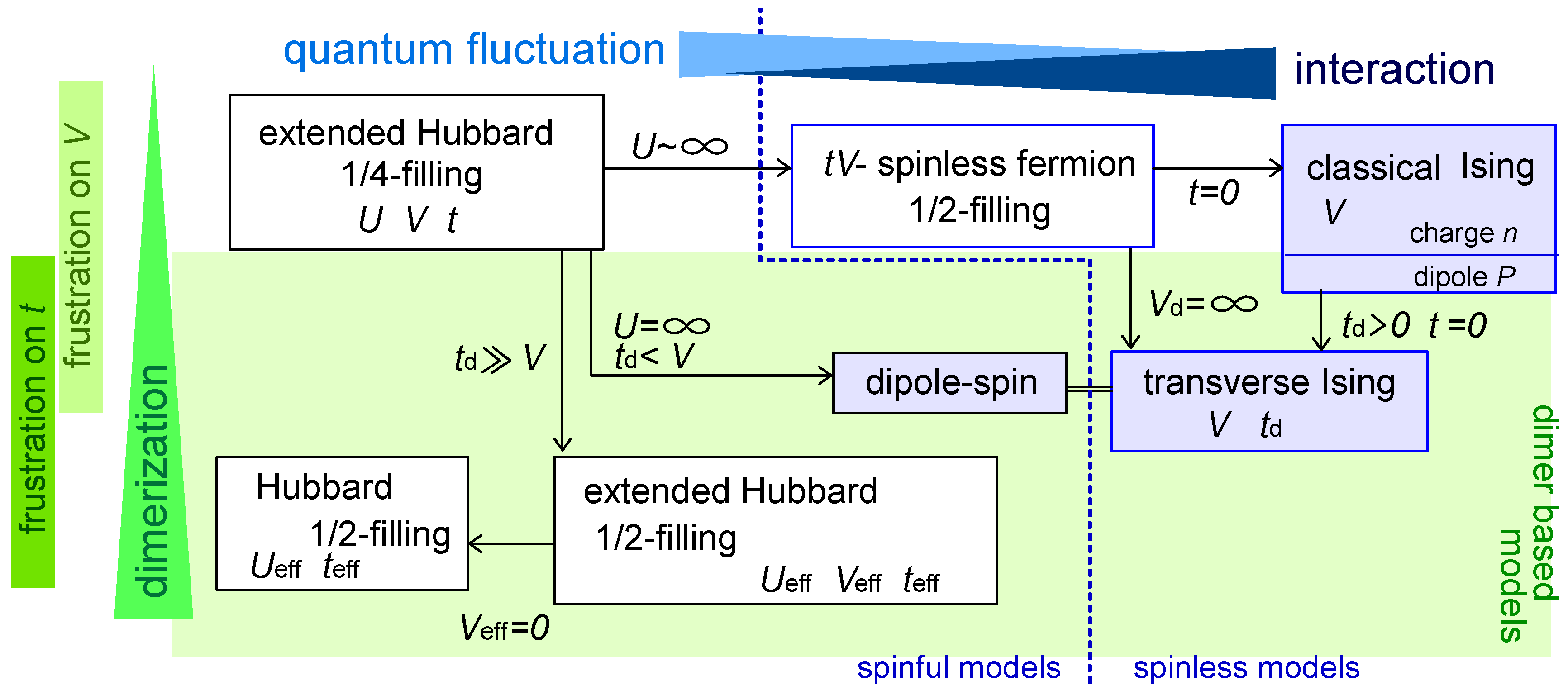

2.2. Classification of Models

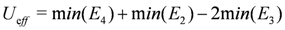

denote the creation/annihilation operator of electron on i-th site (molecule) with spin σ, and

denote the creation/annihilation operator of electron on i-th site (molecule) with spin σ, and  is the electron number operator, with ni = ni↑ + ni↓. U and Vij are the on-site and inter-site Coulomb interactions respectively, and tij is the transfer integral between sites i and j. We treat Vij as those between nearest neighbor molecules (sites) unless otherwise noted.

is the electron number operator, with ni = ni↑ + ni↓. U and Vij are the on-site and inter-site Coulomb interactions respectively, and tij is the transfer integral between sites i and j. We treat Vij as those between nearest neighbor molecules (sites) unless otherwise noted.

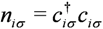

), and two electron states

), and two electron states  in the isolated dimer with

in the isolated dimer with  and td. The approximation to the half-filled Hubbard model (dimer approximation) corresponds to confining the basis of a dimer to those belonging to

and td. The approximation to the half-filled Hubbard model (dimer approximation) corresponds to confining the basis of a dimer to those belonging to  . The dipole-spin model is verified in cases where all the two electron levels,

. The dipole-spin model is verified in cases where all the two electron levels,  , become higher than

, become higher than  . Schematic illustration of the basis sets of the two approximations are shown in (b) and (c).

. Schematic illustration of the basis sets of the two approximations are shown in (b) and (c).

), and two electron states

), and two electron states  in the isolated dimer with

in the isolated dimer with  and td. The approximation to the half-filled Hubbard model (dimer approximation) corresponds to confining the basis of a dimer to those belonging to

and td. The approximation to the half-filled Hubbard model (dimer approximation) corresponds to confining the basis of a dimer to those belonging to  . The dipole-spin model is verified in cases where all the two electron levels,

. The dipole-spin model is verified in cases where all the two electron levels,  , become higher than

, become higher than  . Schematic illustration of the basis sets of the two approximations are shown in (b) and (c).

. Schematic illustration of the basis sets of the two approximations are shown in (b) and (c).

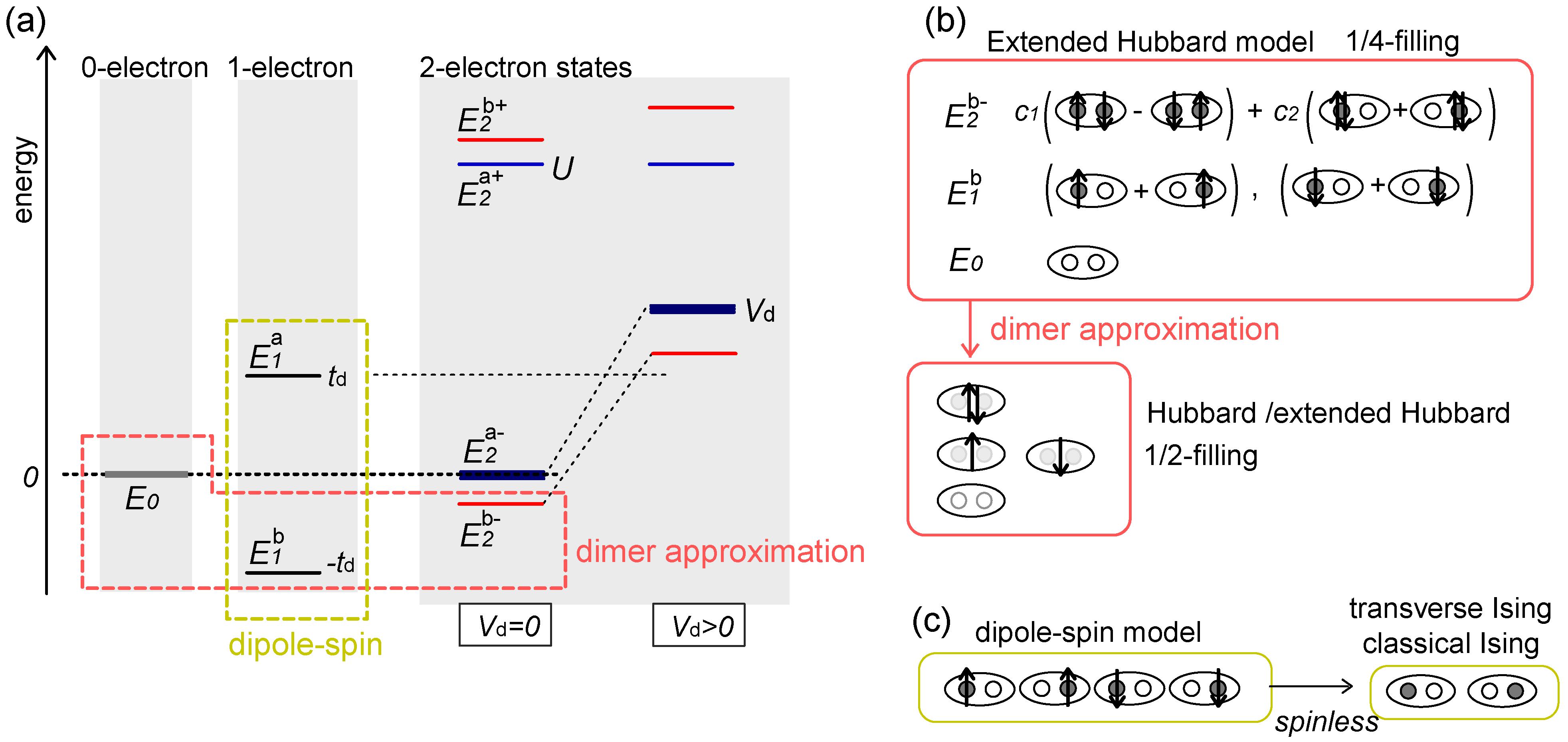

, of n-electron energy (n = 0,1,2), where superscript a/b denotes the anti-bonding/bonding state. Let us further simplify the model within the remaining basis states by eliminating the relatively higher energy degrees of freedom within them. In the case of Vd = 0 (and Vij = 0), a half-filled single band Hubbard model

, of n-electron energy (n = 0,1,2), where superscript a/b denotes the anti-bonding/bonding state. Let us further simplify the model within the remaining basis states by eliminating the relatively higher energy degrees of freedom within them. In the case of Vd = 0 (and Vij = 0), a half-filled single band Hubbard model

), one- (two

), one- (two  ’s) and two-electrons (lower

’s) and two-electrons (lower  ), shown in Figure 4(a,b), and regarding them as a new basis, which process is called the “dimer approximation”. The operator

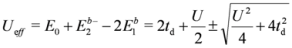

), shown in Figure 4(a,b), and regarding them as a new basis, which process is called the “dimer approximation”. The operator  creates/annihilates the electron on these new levels. The on-dimer Coulomb interaction is obtained within this new basis as a “one particle charge gap” of the isolated dimer,

creates/annihilates the electron on these new levels. The on-dimer Coulomb interaction is obtained within this new basis as a “one particle charge gap” of the isolated dimer,  . (In the hole picture,

. (In the hole picture,  gives the same result). So far, the upper bound of the above formula, Ueff ~ 2td, at U = ∞ (i.e., at

gives the same result). So far, the upper bound of the above formula, Ueff ~ 2td, at U = ∞ (i.e., at  , which is an upper bound of this level) had often been applied as the effective interaction strength in material systems. However, once we set Vd > 0, the above discussion may easily break down. There are two problems. Firstly, the on-dimer Coulomb interactions are modified to

, which is an upper bound of this level) had often been applied as the effective interaction strength in material systems. However, once we set Vd > 0, the above discussion may easily break down. There are two problems. Firstly, the on-dimer Coulomb interactions are modified to

, included in the dimer approximation shifts upward by Vd to near

, included in the dimer approximation shifts upward by Vd to near  . Therefore, discarding the anti-bonding one-electron state of

. Therefore, discarding the anti-bonding one-electron state of  in the dimer approximation itself, even using Equation (5), may no longer be valid.

in the dimer approximation itself, even using Equation (5), may no longer be valid. . The quantization z-axis of dipoles is fixed to the dimer-bond direction in real space. Including the spin degrees of freedom, Sz, the four basis states in Figure 4(c) are described as,

. The quantization z-axis of dipoles is fixed to the dimer-bond direction in real space. Including the spin degrees of freedom, Sz, the four basis states in Figure 4(c) are described as,  . The first order perturbation in the extended Hubbard model from the strong coupling limit, U = Vd = ∞, by td > 0 yields [20],

. The first order perturbation in the extended Hubbard model from the strong coupling limit, U = Vd = ∞, by td > 0 yields [20],

is the linear combination of Vij’s connecting the sites i and j each belonging to two adjacent dimers, m and n, respectively. By the hopping (td) of electron,

is the linear combination of Vij’s connecting the sites i and j each belonging to two adjacent dimers, m and n, respectively. By the hopping (td) of electron,  flips quantum mechanically between +1/2 and -1/2, thus this object is regarded as a quantum electric dipole.

flips quantum mechanically between +1/2 and -1/2, thus this object is regarded as a quantum electric dipole.

. Typically, the Holstein- and Peierls-type (equivalently, Su–Schrieffer–Heeger-type) of electron-lattice interactions shall be relevant in organic crystals due to the anionic potential, or to the electron-molecular-vibration-coupling, which have the form,

. Typically, the Holstein- and Peierls-type (equivalently, Su–Schrieffer–Heeger-type) of electron-lattice interactions shall be relevant in organic crystals due to the anionic potential, or to the electron-molecular-vibration-coupling, which have the form,

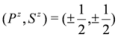

2.3. Frustration

3. Strong Coupling Regime

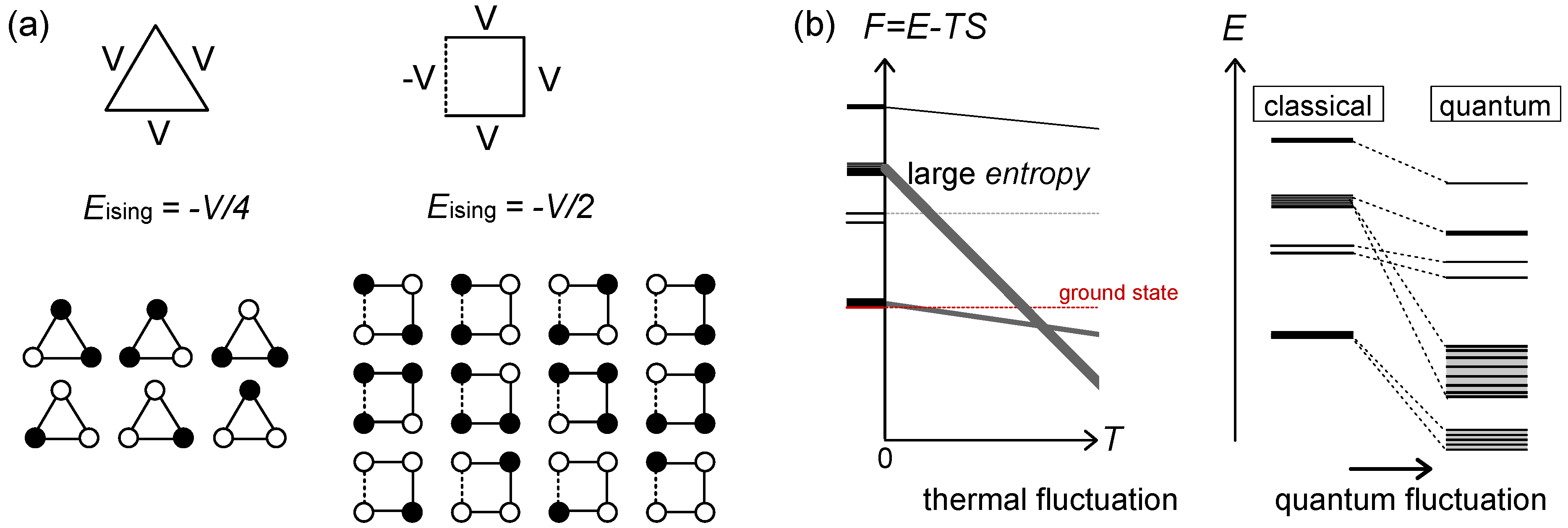

3.1. Frustrated Metal: Ground States

or

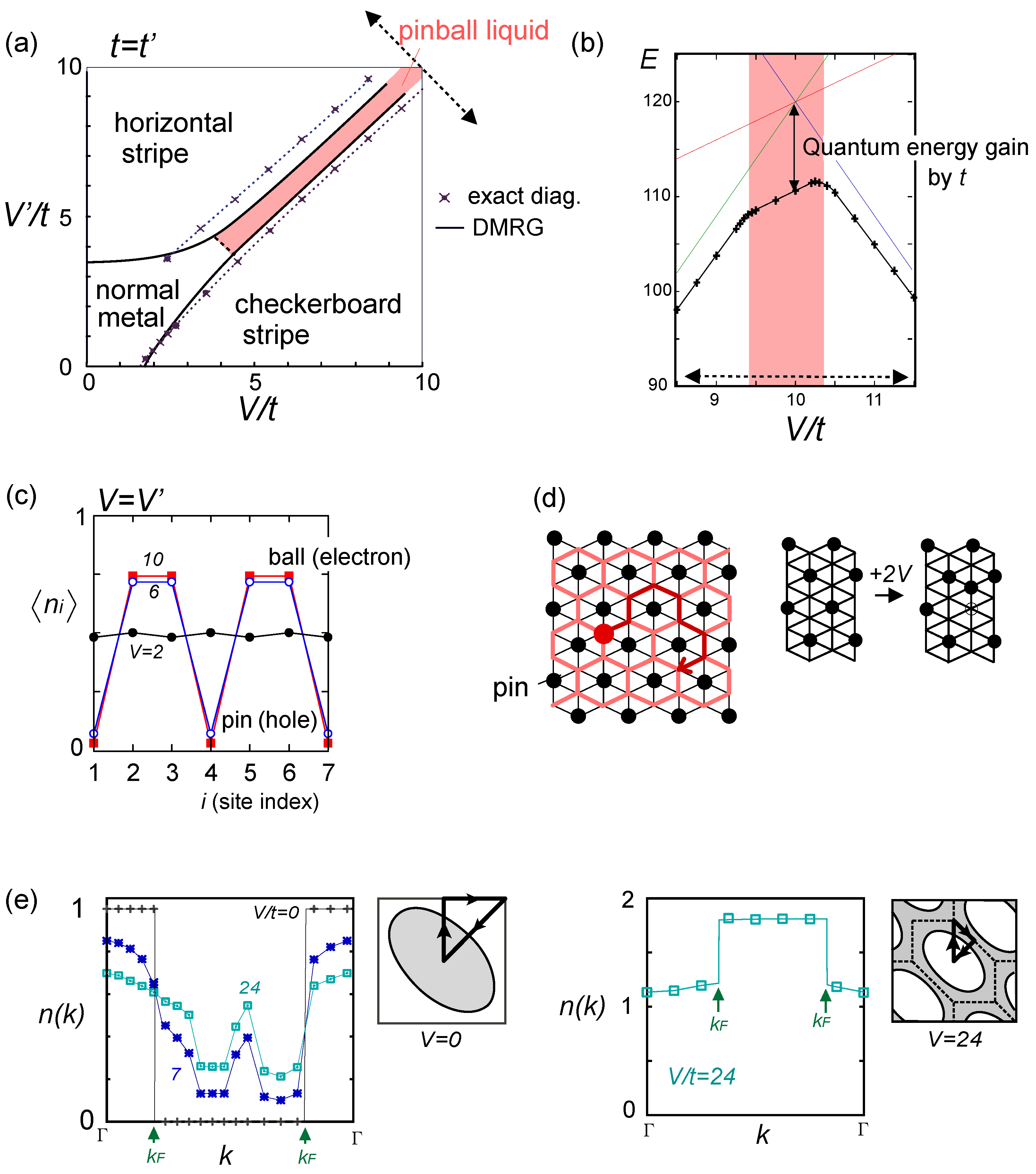

or  . Both choices are energetically degenerate, since the two diagonal V-bonds are still frustrated. These remaining degrees of freedom multiplied over L-chains contribute to the 2L fold degeneracy.

. Both choices are energetically degenerate, since the two diagonal V-bonds are still frustrated. These remaining degrees of freedom multiplied over L-chains contribute to the 2L fold degeneracy.  and t and exhibit two crossing points as first order transitions. Figure 9(c) shows the spacial distribution of charges along one bond direction; when one enters the pinball liquid phase, a three-fold poor-rich-rich (pin-ball-ball) distribution of charges develops. The fermions (holes) at the center of the hexagon form a solid, and the itinerancy of fermions develops along their edges, which could be approximately regard as a spontaneous spacial phase separation into solid and liquid components. The energetics roughly explains why this happens (see Figure 9(d)); if one tries to move the “pins” to its vacant neighbor, the energy loss is 2V, thus they cannot easily move. In contrast, moving the “balls” along the vacant honeycomb lattice has no classical energy cost but instead brings a kinetic (quantum) energy gain. The long range order of the solid component is verified by the size scaling analyses on the charge structural factor by a variational Monte Carlo (VMC) method [29,30]. The VMC calculation also showed that the Fermi surface reconstruction takes place at the phase transition from a normal metal to a pinball liquid. As shown in Figure 9(e), the momentum distribution function, n(k), is a step function at V = 0, which gives the round Fermi surface (electron pocket). At large V, n(k) exhibits a fine structure, and by folding the Brillouin zone into one-third, another stepwise function appears, forming a round hole pocket. This indicates a Fermi liquid nature of the balls. These results support a picture that the solids partially melt and form quasi-particles(balls) which are almost free despite their highly correlated origin. We note that there is still a possibility of having quantum liquid state originating from the good defect manifolds (0 < Nd < N/3 in Figure 6), in between the horizontal stripe and the pinball liquid, but the examination on this issue needs calculations on larger lattice size, and is left for future study.

and t and exhibit two crossing points as first order transitions. Figure 9(c) shows the spacial distribution of charges along one bond direction; when one enters the pinball liquid phase, a three-fold poor-rich-rich (pin-ball-ball) distribution of charges develops. The fermions (holes) at the center of the hexagon form a solid, and the itinerancy of fermions develops along their edges, which could be approximately regard as a spontaneous spacial phase separation into solid and liquid components. The energetics roughly explains why this happens (see Figure 9(d)); if one tries to move the “pins” to its vacant neighbor, the energy loss is 2V, thus they cannot easily move. In contrast, moving the “balls” along the vacant honeycomb lattice has no classical energy cost but instead brings a kinetic (quantum) energy gain. The long range order of the solid component is verified by the size scaling analyses on the charge structural factor by a variational Monte Carlo (VMC) method [29,30]. The VMC calculation also showed that the Fermi surface reconstruction takes place at the phase transition from a normal metal to a pinball liquid. As shown in Figure 9(e), the momentum distribution function, n(k), is a step function at V = 0, which gives the round Fermi surface (electron pocket). At large V, n(k) exhibits a fine structure, and by folding the Brillouin zone into one-third, another stepwise function appears, forming a round hole pocket. This indicates a Fermi liquid nature of the balls. These results support a picture that the solids partially melt and form quasi-particles(balls) which are almost free despite their highly correlated origin. We note that there is still a possibility of having quantum liquid state originating from the good defect manifolds (0 < Nd < N/3 in Figure 6), in between the horizontal stripe and the pinball liquid, but the examination on this issue needs calculations on larger lattice size, and is left for future study.  . Thus, this value is a crossover boundary between the weak and strong coupling regime. In this way, the strong coupling physics could be applied to a wide parameter region in the quarter-filled electronic systems.

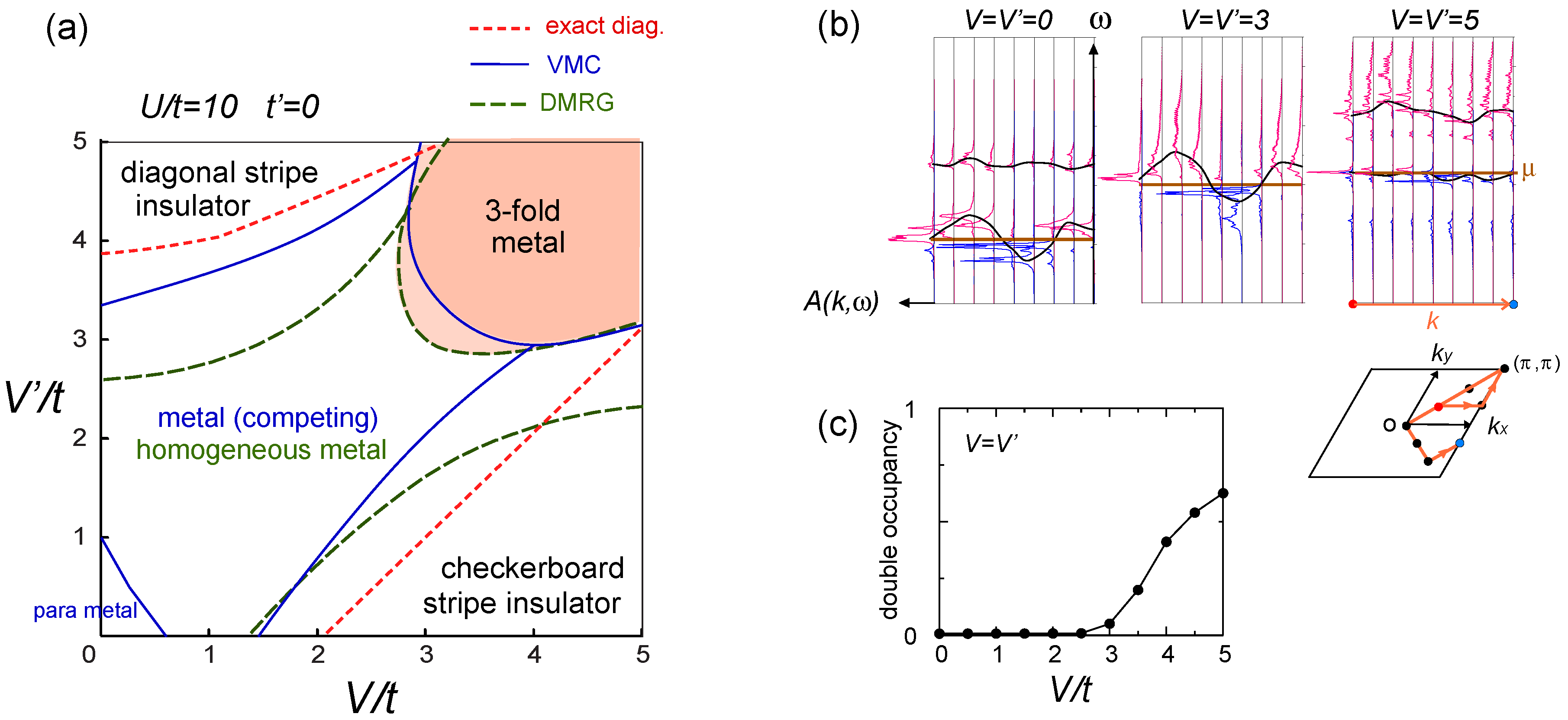

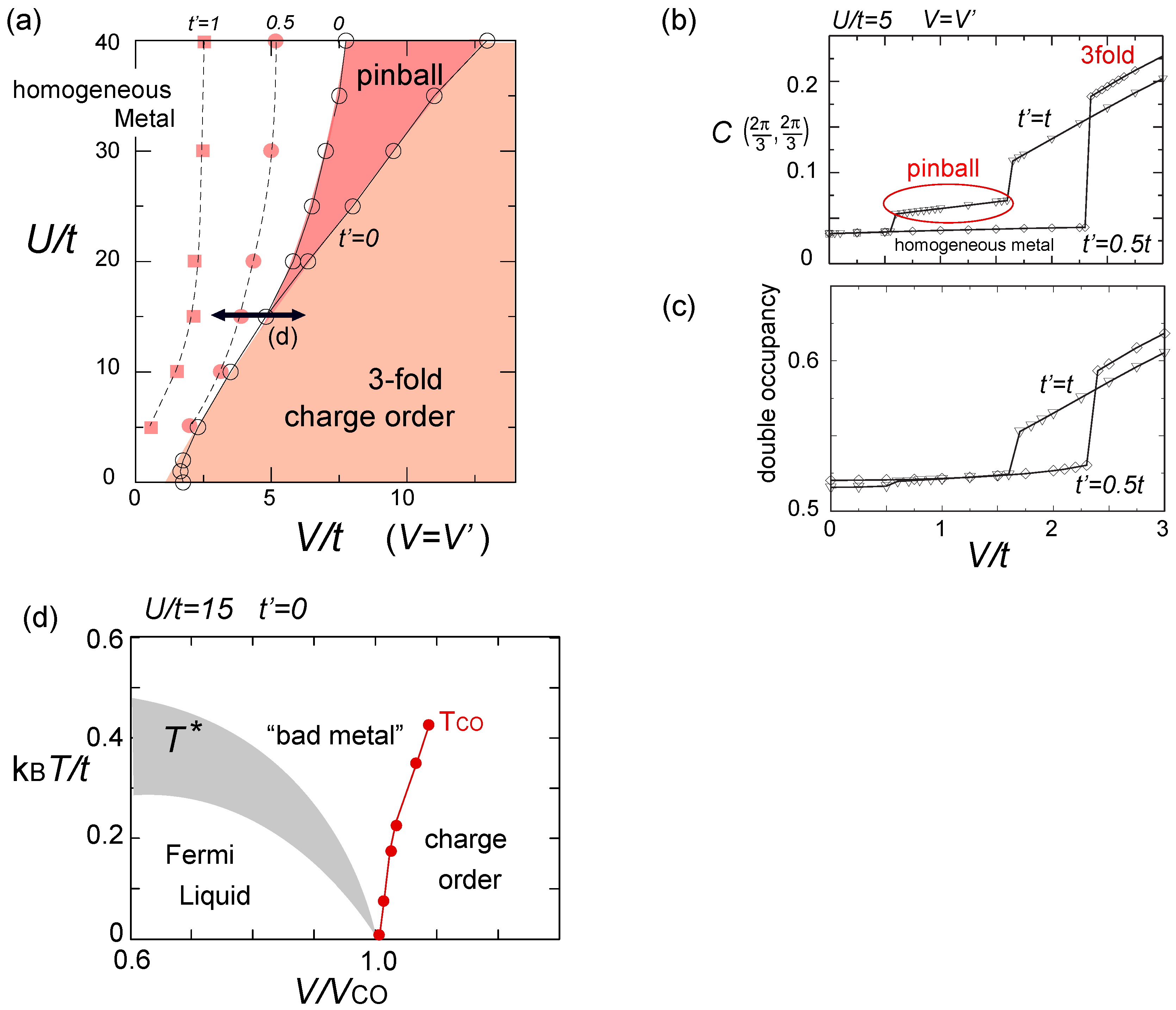

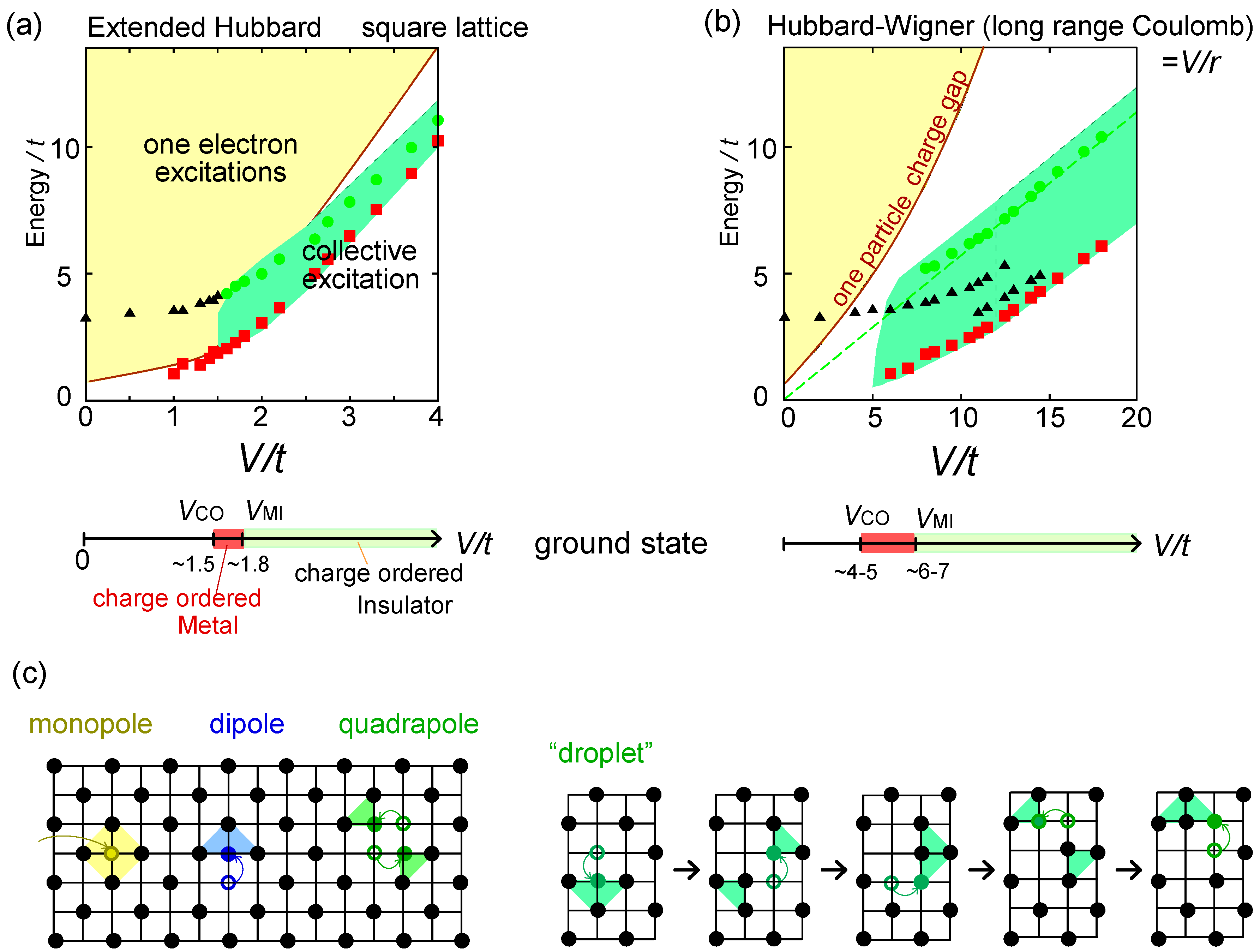

. Thus, this value is a crossover boundary between the weak and strong coupling regime. In this way, the strong coupling physics could be applied to a wide parameter region in the quarter-filled electronic systems.  from the tV-results and allow the double occupancy of electrons. Before discussing this issue, we overview the earlier works on the same extended Hubbard model, which are summarized in the phase diagram in Figure 10(a); the results of the exact diagonalization by Merino et al. [32], VMC by Watanabe et al. [33], and DMRG with by Nishimoto et al. [34] are put together for comparison. The one by Merino et al. [32] was the first work to point out the possibility of frustration in organic systems, while they missed the existence of three-fold metallic state, whose period is incompatible with the shape and size of their cluster (N = 4 × 4). Otherwise, the results by different methods are overall qualitatively in agreement with each other. However, large quantitative discrepancies of the phase boundaries indicate the extreme difficulty of dealing with the correlation effects in frustrated systems in the intermediate coupling region [35], as we discussed in Section 2.3. Actually, the mean field result on the same model by Kaneko and Ogata [36] has a pseudo-degenerate energy level (degenerate within the order of ~ O(10−3t~10−4t)) in the metallic state at the center of the phase diagram, consisting of many different stripes and three-fold states (“metal (competing)” in Figure 10(a)). Although the VMC calculation may lift some of the pseudo-degeneracy by including the correlation effect, the energies of the two stripes and three-fold state are still almost degenerate within the range of 10−4t [33].

from the tV-results and allow the double occupancy of electrons. Before discussing this issue, we overview the earlier works on the same extended Hubbard model, which are summarized in the phase diagram in Figure 10(a); the results of the exact diagonalization by Merino et al. [32], VMC by Watanabe et al. [33], and DMRG with by Nishimoto et al. [34] are put together for comparison. The one by Merino et al. [32] was the first work to point out the possibility of frustration in organic systems, while they missed the existence of three-fold metallic state, whose period is incompatible with the shape and size of their cluster (N = 4 × 4). Otherwise, the results by different methods are overall qualitatively in agreement with each other. However, large quantitative discrepancies of the phase boundaries indicate the extreme difficulty of dealing with the correlation effects in frustrated systems in the intermediate coupling region [35], as we discussed in Section 2.3. Actually, the mean field result on the same model by Kaneko and Ogata [36] has a pseudo-degenerate energy level (degenerate within the order of ~ O(10−3t~10−4t)) in the metallic state at the center of the phase diagram, consisting of many different stripes and three-fold states (“metal (competing)” in Figure 10(a)). Although the VMC calculation may lift some of the pseudo-degeneracy by including the correlation effect, the energies of the two stripes and three-fold state are still almost degenerate within the range of 10−4t [33]. along one bond direction by the DMRG, from [27]; (d) Sketch of a pinball liquid state (left) and the process of moving pins (right panel); (e) Momentum distribution function n(k) of the full Brillouin zone (left panel), and of the folded (1/3) Brillouin zone (right panel) by the VMC in [29], together with the schematic Fermi surfaces. The axis k is taken along the arrow of the Brillouin zone in the inset. At V/t = 24, n(k) is shown for full and 1/3-folded Brillouin zones, and the latter displays a reconstruction of the Fermi surface, with a Fermi liquid type of discontinuity.

along one bond direction by the DMRG, from [27]; (d) Sketch of a pinball liquid state (left) and the process of moving pins (right panel); (e) Momentum distribution function n(k) of the full Brillouin zone (left panel), and of the folded (1/3) Brillouin zone (right panel) by the VMC in [29], together with the schematic Fermi surfaces. The axis k is taken along the arrow of the Brillouin zone in the inset. At V/t = 24, n(k) is shown for full and 1/3-folded Brillouin zones, and the latter displays a reconstruction of the Fermi surface, with a Fermi liquid type of discontinuity.

along one bond direction by the DMRG, from [27]; (d) Sketch of a pinball liquid state (left) and the process of moving pins (right panel); (e) Momentum distribution function n(k) of the full Brillouin zone (left panel), and of the folded (1/3) Brillouin zone (right panel) by the VMC in [29], together with the schematic Fermi surfaces. The axis k is taken along the arrow of the Brillouin zone in the inset. At V/t = 24, n(k) is shown for full and 1/3-folded Brillouin zones, and the latter displays a reconstruction of the Fermi surface, with a Fermi liquid type of discontinuity.

along one bond direction by the DMRG, from [27]; (d) Sketch of a pinball liquid state (left) and the process of moving pins (right panel); (e) Momentum distribution function n(k) of the full Brillouin zone (left panel), and of the folded (1/3) Brillouin zone (right panel) by the VMC in [29], together with the schematic Fermi surfaces. The axis k is taken along the arrow of the Brillouin zone in the inset. At V/t = 24, n(k) is shown for full and 1/3-folded Brillouin zones, and the latter displays a reconstruction of the Fermi surface, with a Fermi liquid type of discontinuity.

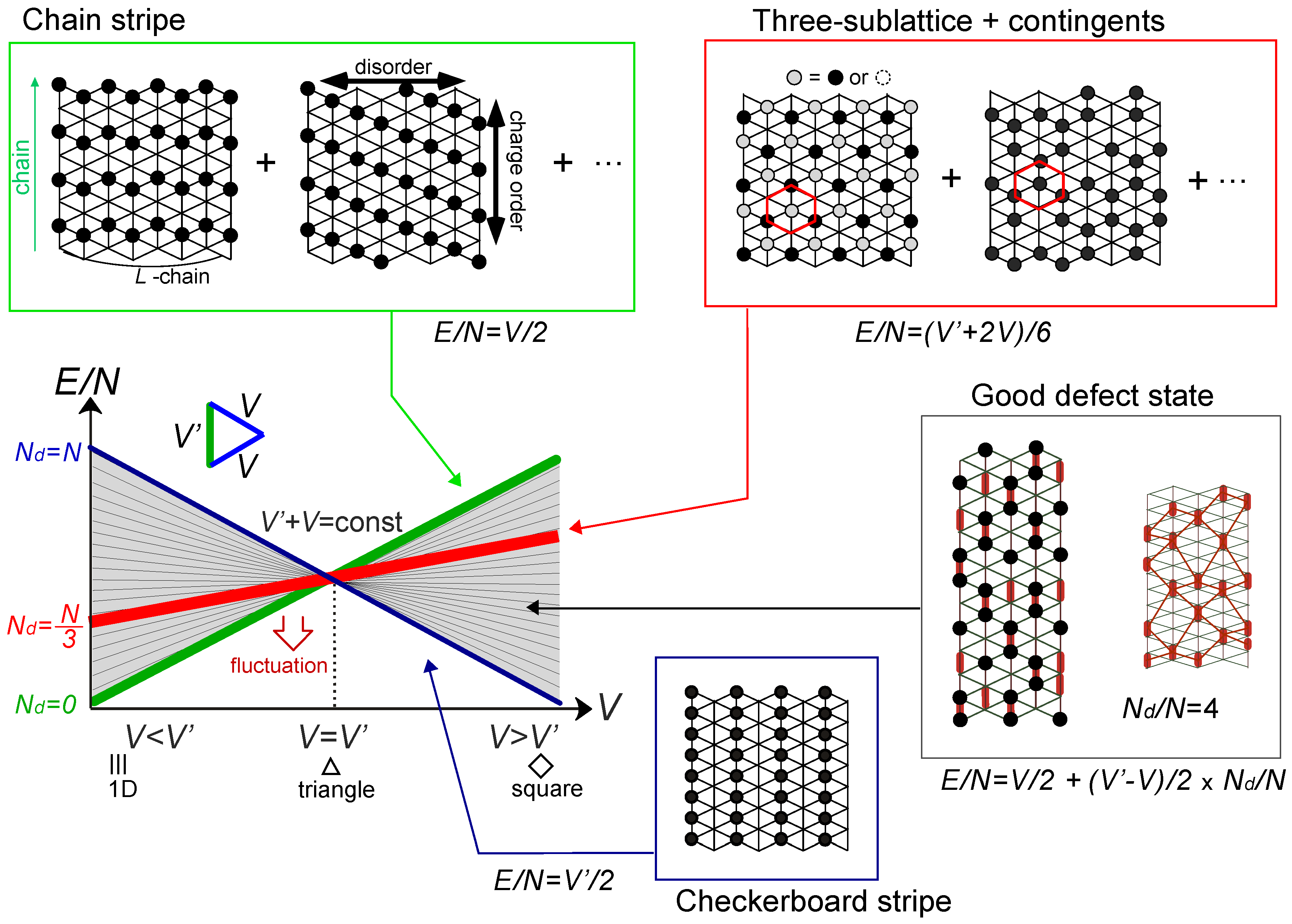

3.2. Frustrated Metal: Excitations

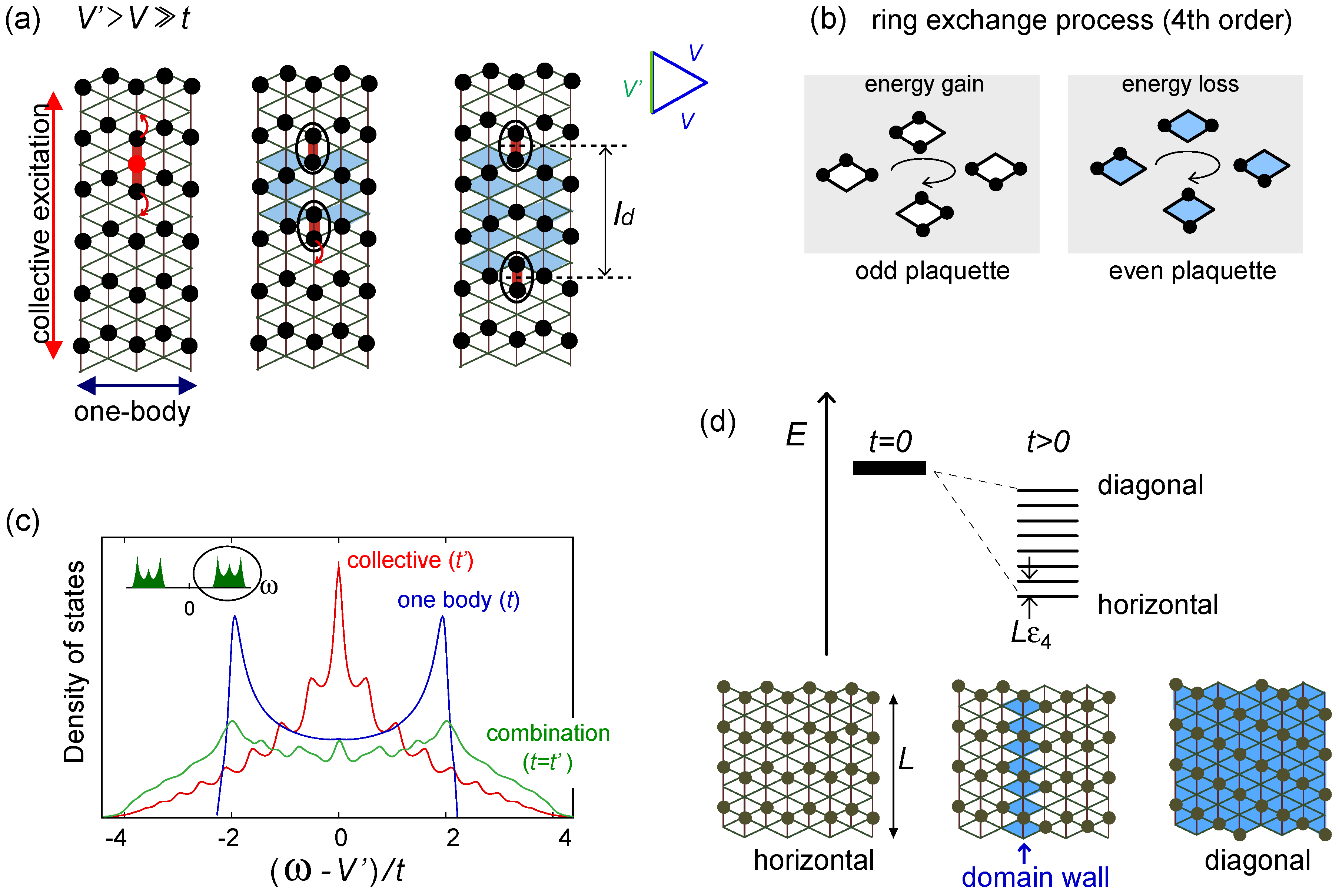

, which have the domain wall excitation. The diagonal/horizontal stripe filled with even/odd plaquettes has the highest/lowest energy.

, which have the domain wall excitation. The diagonal/horizontal stripe filled with even/odd plaquettes has the highest/lowest energy.

, which have the domain wall excitation. The diagonal/horizontal stripe filled with even/odd plaquettes has the highest/lowest energy.

, which have the domain wall excitation. The diagonal/horizontal stripe filled with even/odd plaquettes has the highest/lowest energy.

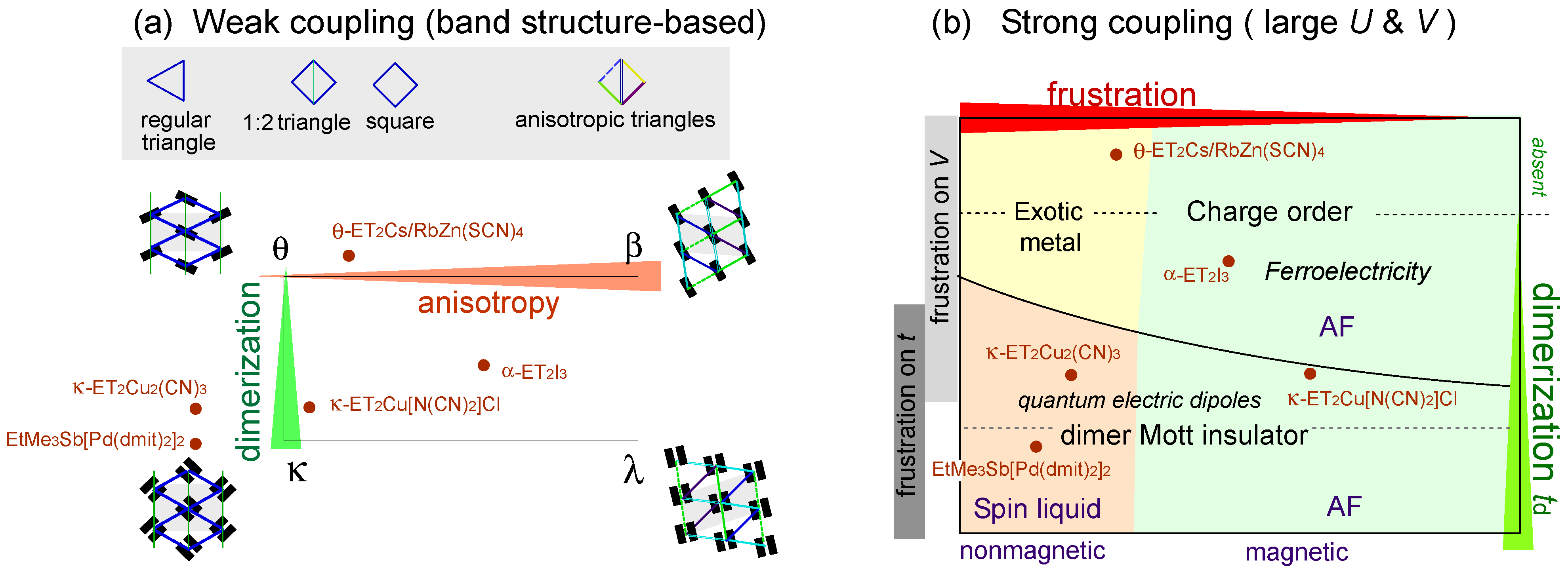

3.3. Dielectrics

- and

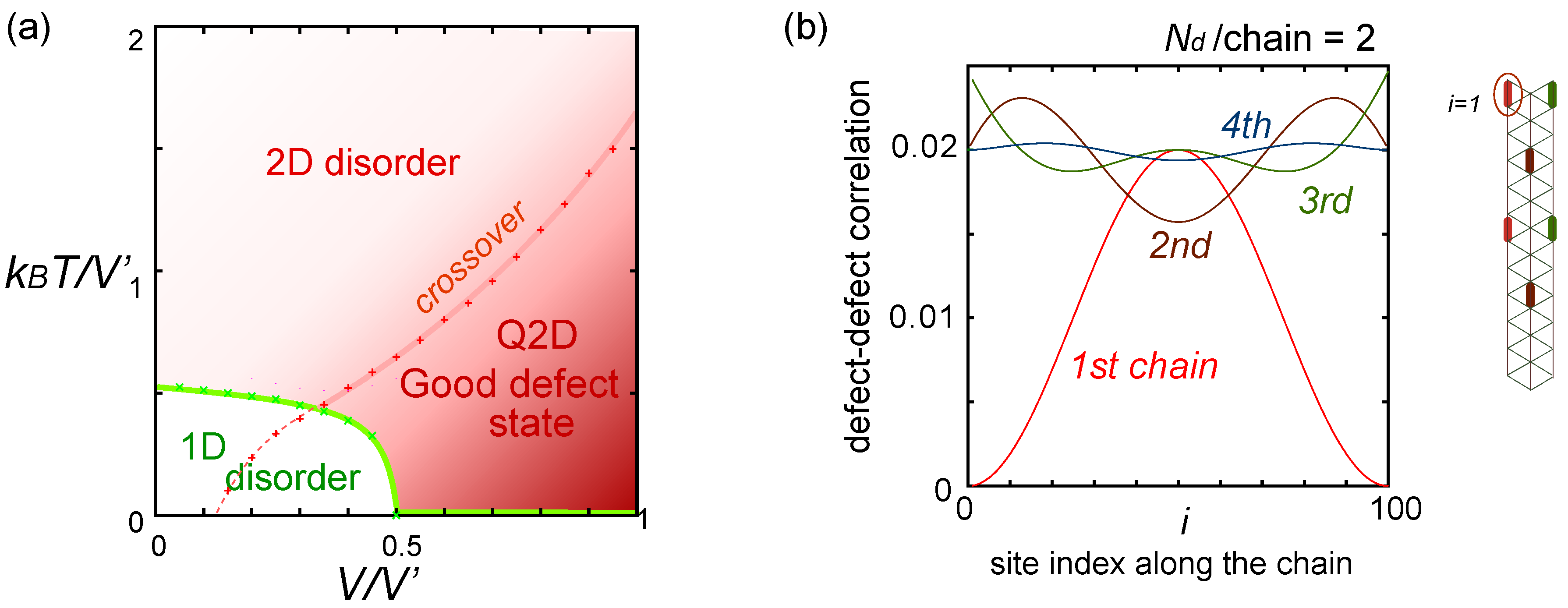

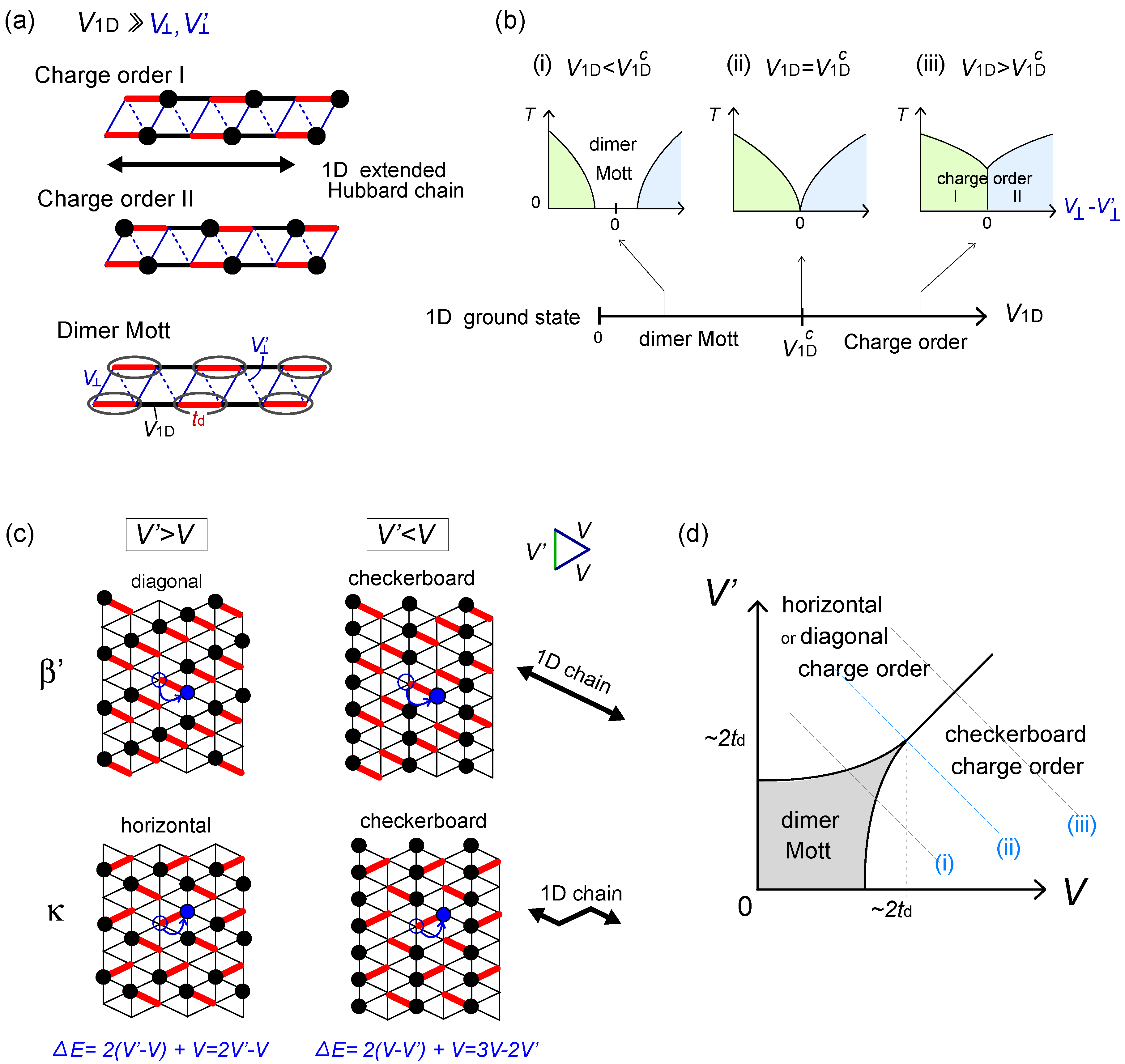

- and  -bonds, using the bosonization technique combined with the inter-chain mean-field (see Figure 14(a)) [51]. To understand their context we draw schematic phase diagrams in Figure 14(b); when U and td are enough large, the ground states in one-dimension (

-bonds, using the bosonization technique combined with the inter-chain mean-field (see Figure 14(a)) [51]. To understand their context we draw schematic phase diagrams in Figure 14(b); when U and td are enough large, the ground states in one-dimension (  ) are divided into the charge order and the dimer Mott insulator by the intra-chain Coulomb interaction at

) are divided into the charge order and the dimer Mott insulator by the intra-chain Coulomb interaction at  [52]. The small inter-chain Coulomb interactions,

[52]. The small inter-chain Coulomb interactions,  and

and  (

(  ), basically stabilize the charge ordering. Thus, as far as

), basically stabilize the charge ordering. Thus, as far as  , the system is charge ordered for all values of

, the system is charge ordered for all values of  and

and  (case (iii)). At

(case (iii)). At  , there is a critical value of

, there is a critical value of  to have a charge order (case (i)). This is because

to have a charge order (case (i)). This is because  and

and  work as mean-field potentials onto a neighboring chain along the two edges of the triangular unit, and if the charges are ordered, the signs of the two potentials differ and cancel out. This could be regarded as a “weak frustration effect”.

work as mean-field potentials onto a neighboring chain along the two edges of the triangular unit, and if the charges are ordered, the signs of the two potentials differ and cancel out. This could be regarded as a “weak frustration effect”. and

and  ; (b) Schematic phase diagrams of model (a) on the plane of temperature (T) and

; (b) Schematic phase diagrams of model (a) on the plane of temperature (T) and  , which Hotta constructed referring to the renormalization group and inter-chain mean-field results by Yoshioka et al [51]. The ground state of the pure 1D chain for

, which Hotta constructed referring to the renormalization group and inter-chain mean-field results by Yoshioka et al [51]. The ground state of the pure 1D chain for  is shown in the lower panel. Depending on the relative strength of V1D against

is shown in the lower panel. Depending on the relative strength of V1D against  , the finite temperature phase diagram at finite

, the finite temperature phase diagram at finite  is classified into three cases; (c) Dimerized (td in bold red bonds) β′- and κ-type of lattice structures based on the anisotropic triangular lattice with V and V′. The classical degeneracy of charge order at V′ > V (chain stripe in Figure 6) is lifted and the diagonal(β′) and horizontal(κ) stripes, which maximally gain the energy by ε2N/2, become the unique ground states; (d) Schematic ground state phase diagram of the dimerized extended Hubbard model on the lattices (c) at

is classified into three cases; (c) Dimerized (td in bold red bonds) β′- and κ-type of lattice structures based on the anisotropic triangular lattice with V and V′. The classical degeneracy of charge order at V′ > V (chain stripe in Figure 6) is lifted and the diagonal(β′) and horizontal(κ) stripes, which maximally gain the energy by ε2N/2, become the unique ground states; (d) Schematic ground state phase diagram of the dimerized extended Hubbard model on the lattices (c) at  , which Hotta depicted by regarding diagonal (β′) and horizontal (κ) bond directions as 1D chain.

, which Hotta depicted by regarding diagonal (β′) and horizontal (κ) bond directions as 1D chain.

and

and  ; (b) Schematic phase diagrams of model (a) on the plane of temperature (T) and

; (b) Schematic phase diagrams of model (a) on the plane of temperature (T) and  , which Hotta constructed referring to the renormalization group and inter-chain mean-field results by Yoshioka et al [51]. The ground state of the pure 1D chain for

, which Hotta constructed referring to the renormalization group and inter-chain mean-field results by Yoshioka et al [51]. The ground state of the pure 1D chain for  is shown in the lower panel. Depending on the relative strength of V1D against

is shown in the lower panel. Depending on the relative strength of V1D against  , the finite temperature phase diagram at finite

, the finite temperature phase diagram at finite  is classified into three cases; (c) Dimerized (td in bold red bonds) β′- and κ-type of lattice structures based on the anisotropic triangular lattice with V and V′. The classical degeneracy of charge order at V′ > V (chain stripe in Figure 6) is lifted and the diagonal(β′) and horizontal(κ) stripes, which maximally gain the energy by ε2N/2, become the unique ground states; (d) Schematic ground state phase diagram of the dimerized extended Hubbard model on the lattices (c) at

is classified into three cases; (c) Dimerized (td in bold red bonds) β′- and κ-type of lattice structures based on the anisotropic triangular lattice with V and V′. The classical degeneracy of charge order at V′ > V (chain stripe in Figure 6) is lifted and the diagonal(β′) and horizontal(κ) stripes, which maximally gain the energy by ε2N/2, become the unique ground states; (d) Schematic ground state phase diagram of the dimerized extended Hubbard model on the lattices (c) at  , which Hotta depicted by regarding diagonal (β′) and horizontal (κ) bond directions as 1D chain.

, which Hotta depicted by regarding diagonal (β′) and horizontal (κ) bond directions as 1D chain.

. However, the above quasi-one-dimensional result do not straightforwardly apply when

. However, the above quasi-one-dimensional result do not straightforwardly apply when  . The energetics will clarify this issue— moving one particle in the stripe states to the neighboring site by td costs a classical energy of ΔE = 2 | V′ − V|−V. When

. The energetics will clarify this issue— moving one particle in the stripe states to the neighboring site by td costs a classical energy of ΔE = 2 | V′ − V|−V. When  , this local quantum fluctuation gives only a small energy correction,

, this local quantum fluctuation gives only a small energy correction,  , and the stripe order remains as a ground state. Figure 14(c) shows the horizontal, diagonal and checkerboard stripes, which form a ground state in the β′ and κ-type crystals at V′ ≠ V. In contrast, in the opposite limit,

, and the stripe order remains as a ground state. Figure 14(c) shows the horizontal, diagonal and checkerboard stripes, which form a ground state in the β′ and κ-type crystals at V′ ≠ V. In contrast, in the opposite limit,  , the particles resonate within each dimer almost freely, and all stripe configurations connected by this fluctuation mix and form a dimer Mott insulator. Thus, the competition between td and ΔE rules the phase transition between the two insulators. We could thus draw a schematic phase diagram in two dimension shown in Figure 14(d). The frustration effect stabilizes the dimer Mott phase at V ~ V′, where ΔE takes a minimum.

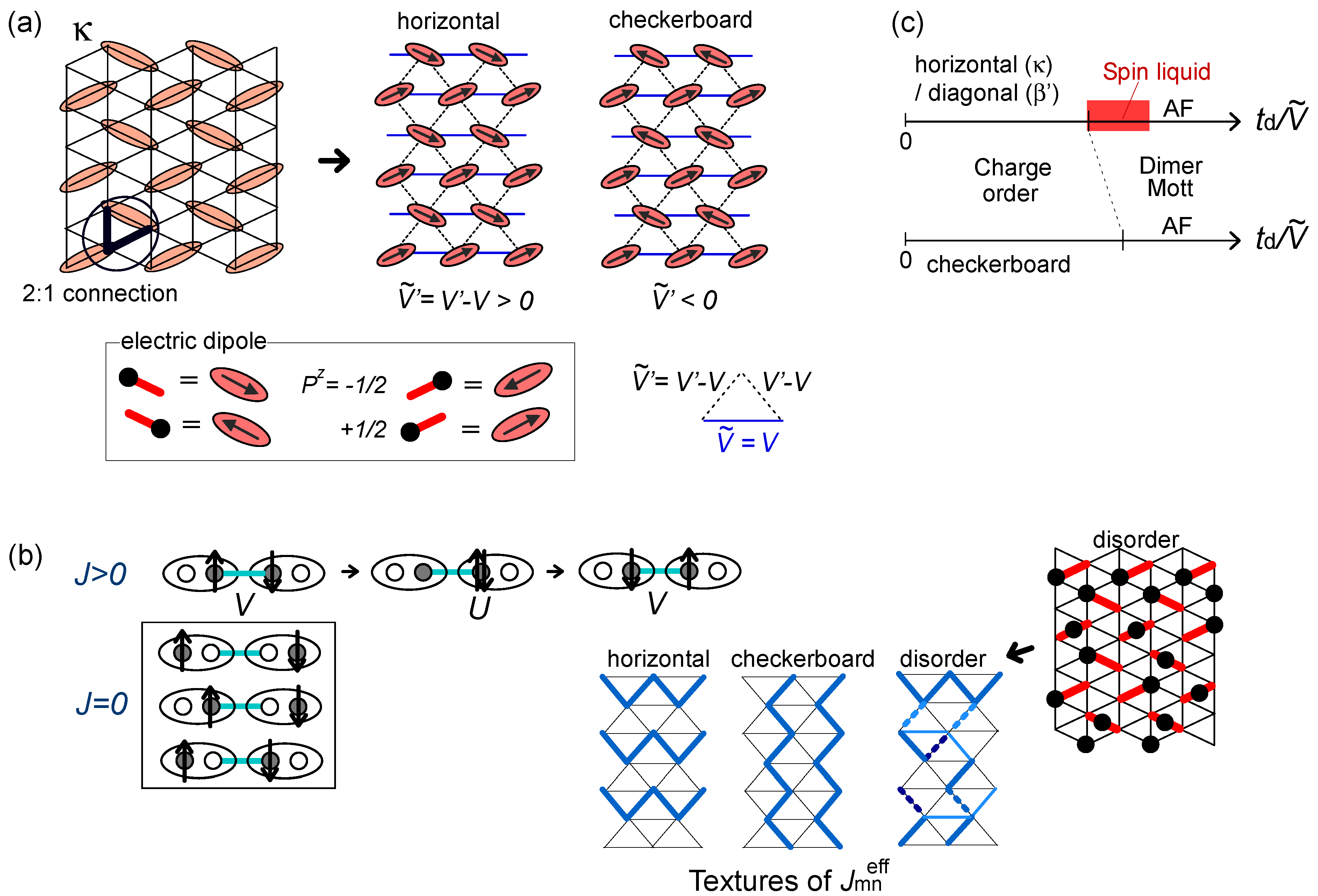

, the particles resonate within each dimer almost freely, and all stripe configurations connected by this fluctuation mix and form a dimer Mott insulator. Thus, the competition between td and ΔE rules the phase transition between the two insulators. We could thus draw a schematic phase diagram in two dimension shown in Figure 14(d). The frustration effect stabilizes the dimer Mott phase at V ~ V′, where ΔE takes a minimum. for ordered and disordered charge configurations; (c) Schematic phase diagram of the dipole-spin model [20].

for ordered and disordered charge configurations; (c) Schematic phase diagram of the dipole-spin model [20].

for ordered and disordered charge configurations; (c) Schematic phase diagram of the dipole-spin model [20].

for ordered and disordered charge configurations; (c) Schematic phase diagram of the dipole-spin model [20].

-bonds and their anisotropy reflects the geometry of the original lattice. When dimers have the 2:1 site connections via two bonds V and V′, the competing V ~ V′ suppress the interactions between dipoles as,

-bonds and their anisotropy reflects the geometry of the original lattice. When dimers have the 2:1 site connections via two bonds V and V′, the competing V ~ V′ suppress the interactions between dipoles as,  . This weak frustration effect is a source of the dimer Mott insulator near V = V′~ 2td, as we just discussed. Then, depending on the sign of

. This weak frustration effect is a source of the dimer Mott insulator near V = V′~ 2td, as we just discussed. Then, depending on the sign of  , either the horizontal or the checkerboard type of dipolar solid (charge order) is stabilized as in Figure 14(d).

, either the horizontal or the checkerboard type of dipolar solid (charge order) is stabilized as in Figure 14(d).  = ∞-limit of the extended Hubbard model (Section 2.2). At the first order, the transverse Ising term determines the ground state of the charge sector (dipole), and at the second order, the Kugel–Khomskii term rules the spin degrees of freedom through the couplings with the dipoles. The spin exchange interaction is evaluated from the coefficients of Sm ∙ Sn in Equation (7) as,

= ∞-limit of the extended Hubbard model (Section 2.2). At the first order, the transverse Ising term determines the ground state of the charge sector (dipole), and at the second order, the Kugel–Khomskii term rules the spin degrees of freedom through the couplings with the dipoles. The spin exchange interaction is evaluated from the coefficients of Sm ∙ Sn in Equation (7) as,

, enhances

, enhances  , as is seen from the second term in Equation (9). When the adjacent dimers have 2:1 site connections, the linear combination, Wz = J′−J, is adopted. (For more details including other terms, see [20]). This rule enables the construction of the spacial texture of

, as is seen from the second term in Equation (9). When the adjacent dimers have 2:1 site connections, the linear combination, Wz = J′−J, is adopted. (For more details including other terms, see [20]). This rule enables the construction of the spacial texture of  on a lattice for any given charge (dipole) configuration. The geometry of

on a lattice for any given charge (dipole) configuration. The geometry of  the localized spins on dimers recognize is thus far from being isotropic, e.g., those shown in Figure 15(b). In the vicinity of the phase transition from a dimer Mott to charge ordering, the correlation of dipoles develops, and the timescales of the fluctuation of short range charge orders slow down. The net

the localized spins on dimers recognize is thus far from being isotropic, e.g., those shown in Figure 15(b). In the vicinity of the phase transition from a dimer Mott to charge ordering, the correlation of dipoles develops, and the timescales of the fluctuation of short range charge orders slow down. The net  produced by the “nearly frozen” dipoles on dimers shall be inhomogeneous, and resultantly, a quantum disorder of spins emerges [20]. Such a dirty “spin liquid” could possibly emerge near the phase transition into the horizontal/diagonal charge ordering in which the frustration effect is relevant, but hardly near the checkerboard stripes (see Figure 15(c)).

produced by the “nearly frozen” dipoles on dimers shall be inhomogeneous, and resultantly, a quantum disorder of spins emerges [20]. Such a dirty “spin liquid” could possibly emerge near the phase transition into the horizontal/diagonal charge ordering in which the frustration effect is relevant, but hardly near the checkerboard stripes (see Figure 15(c)). 3.4. Spin Liquid Mott Insulator

, where J4 is the ring-exchange coupling constant [58]. Since the value of J4 in the localized spin system is generally considered to be weaker by the orders of magnitude than this critical value, a more realistic model was in need.

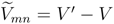

, where J4 is the ring-exchange coupling constant [58]. Since the value of J4 in the localized spin system is generally considered to be weaker by the orders of magnitude than this critical value, a more realistic model was in need.  . A series of studies followed, based on several other numerical methods, which are partially summarized in Figure 16(c,d). Koretsune et al. gave an exact diagonalization study on several different clusters up to N = 18, and averaged the results over the twisted boundary conditions to minimize the size/boundary effect [60]. Kyung and Tremblay applied a cellular dynamical mean-field theory (CDMFT) with 2×2 cluster embedded in bath sites, and proposed a superconducting phase just below the Mott insulator [61]. Clay et al., by the exact diagonalization on a N = 4×4 lattice, reported a (π,0) -magnetic ordering at large U region, and claimed an absence of superconductivity [62]. Another PIRG study [63] with N = 36 argued that in the regular triangle t = t′, the 120° order in the Heisenberg model appears at

. A series of studies followed, based on several other numerical methods, which are partially summarized in Figure 16(c,d). Koretsune et al. gave an exact diagonalization study on several different clusters up to N = 18, and averaged the results over the twisted boundary conditions to minimize the size/boundary effect [60]. Kyung and Tremblay applied a cellular dynamical mean-field theory (CDMFT) with 2×2 cluster embedded in bath sites, and proposed a superconducting phase just below the Mott insulator [61]. Clay et al., by the exact diagonalization on a N = 4×4 lattice, reported a (π,0) -magnetic ordering at large U region, and claimed an absence of superconductivity [62]. Another PIRG study [63] with N = 36 argued that in the regular triangle t = t′, the 120° order in the Heisenberg model appears at  via first order transition from NMI.

via first order transition from NMI.  and

and  between the AFI and the PM phases. The transition point from PM to NMI should lie between U/t ~ 4−5 at t′/t ~0.5 to 6−8 at

between the AFI and the PM phases. The transition point from PM to NMI should lie between U/t ~ 4−5 at t′/t ~0.5 to 6−8 at  . Let us briefly point out three main unsettled issues. dx2−y2-wave superconductivity (d-SC); Kino and Kontani first studied the t′/t-dependence of d-SC by the the fluctuation exchange (FLEX) approximation [64]. The variational Monte Carlo(VMC) studies [65,66] report a robust d-SC at the same intermediate range, t′/t ~0.4−0.7, which is in qualitative agreement with Kyung and Tremblay’s CDMFT (Figure 16(d) have d-SC at lower U than the above two studies). Dayal, Clay, and Mazumdar deny the d-SC phase, both by the exact diagonalization (red lines in Figure 16(d)) and by the QP (quantum number projection)-PIRG [67]. In general, the characteristic energy scale of SC should be several orders of magnitude smaller than t. The small cluster size of N ~ O(10) which leads to the artificial discretization of energy levels larger than that order may not be enough to stabilize the SC phases. The exact diagonalization or QP-PIRG of N = 4 × 4 to 8 × 8 might thus underestimate the stability of SC. Contrarily, FLEX, CDMFT and VMC basically have a mean-field character, somewhat lacking the long range correlation, in which case the SC shall be overestimated. For these reasons, the degree of stability of the d-SC phase cannot be easily concluded.

. Let us briefly point out three main unsettled issues. dx2−y2-wave superconductivity (d-SC); Kino and Kontani first studied the t′/t-dependence of d-SC by the the fluctuation exchange (FLEX) approximation [64]. The variational Monte Carlo(VMC) studies [65,66] report a robust d-SC at the same intermediate range, t′/t ~0.4−0.7, which is in qualitative agreement with Kyung and Tremblay’s CDMFT (Figure 16(d) have d-SC at lower U than the above two studies). Dayal, Clay, and Mazumdar deny the d-SC phase, both by the exact diagonalization (red lines in Figure 16(d)) and by the QP (quantum number projection)-PIRG [67]. In general, the characteristic energy scale of SC should be several orders of magnitude smaller than t. The small cluster size of N ~ O(10) which leads to the artificial discretization of energy levels larger than that order may not be enough to stabilize the SC phases. The exact diagonalization or QP-PIRG of N = 4 × 4 to 8 × 8 might thus underestimate the stability of SC. Contrarily, FLEX, CDMFT and VMC basically have a mean-field character, somewhat lacking the long range correlation, in which case the SC shall be overestimated. For these reasons, the degree of stability of the d-SC phase cannot be easily concluded.

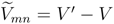

), and the higher-order contributions become by orders of magnitudes smaller (see Figure 17(a)). The ratio,

), and the higher-order contributions become by orders of magnitudes smaller (see Figure 17(a)). The ratio,  , at

, at  is indeed enough to stabilize the gapless spin liquid. The structural factor of the 120° order, S(Q = (4π/3,0)), drops at U/t ~ 10, as shown in Figure 17(b), suggesting a transition into a “spin liquid” phase. Above/below U/t = 10, S(Q)is enhanced/unchanged with the system size N, indicating that the magnetic long range order is only present above this critical point. At U/t < 10, one could expect either a short range correlation or a critical algebraic decay of correlation functions. A jump in the double occupancy is observed as a consequence of the level crossing of the ground state energies (see Figure 17(c)), in agreement with those calculated for the Hubbard model at N = 21. This work succeeded in showing that the low-energy effective model in the insulating phase, even in the vicinity of the metal-insulator transition, is indeed a pure spin model—in other words, they confirmed that the strong coupling perturbation theory is extended down to the order of t/U ~ O(0.1). This result strongly supports the first proposal on the origin of a spin liquid state by PIRG [59], that the spacial charge fluctuation near the Mott transition plays crucial role.

is indeed enough to stabilize the gapless spin liquid. The structural factor of the 120° order, S(Q = (4π/3,0)), drops at U/t ~ 10, as shown in Figure 17(b), suggesting a transition into a “spin liquid” phase. Above/below U/t = 10, S(Q)is enhanced/unchanged with the system size N, indicating that the magnetic long range order is only present above this critical point. At U/t < 10, one could expect either a short range correlation or a critical algebraic decay of correlation functions. A jump in the double occupancy is observed as a consequence of the level crossing of the ground state energies (see Figure 17(c)), in agreement with those calculated for the Hubbard model at N = 21. This work succeeded in showing that the low-energy effective model in the insulating phase, even in the vicinity of the metal-insulator transition, is indeed a pure spin model—in other words, they confirmed that the strong coupling perturbation theory is extended down to the order of t/U ~ O(0.1). This result strongly supports the first proposal on the origin of a spin liquid state by PIRG [59], that the spacial charge fluctuation near the Mott transition plays crucial role.

4. Weak Coupling Regime

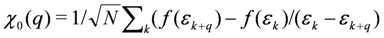

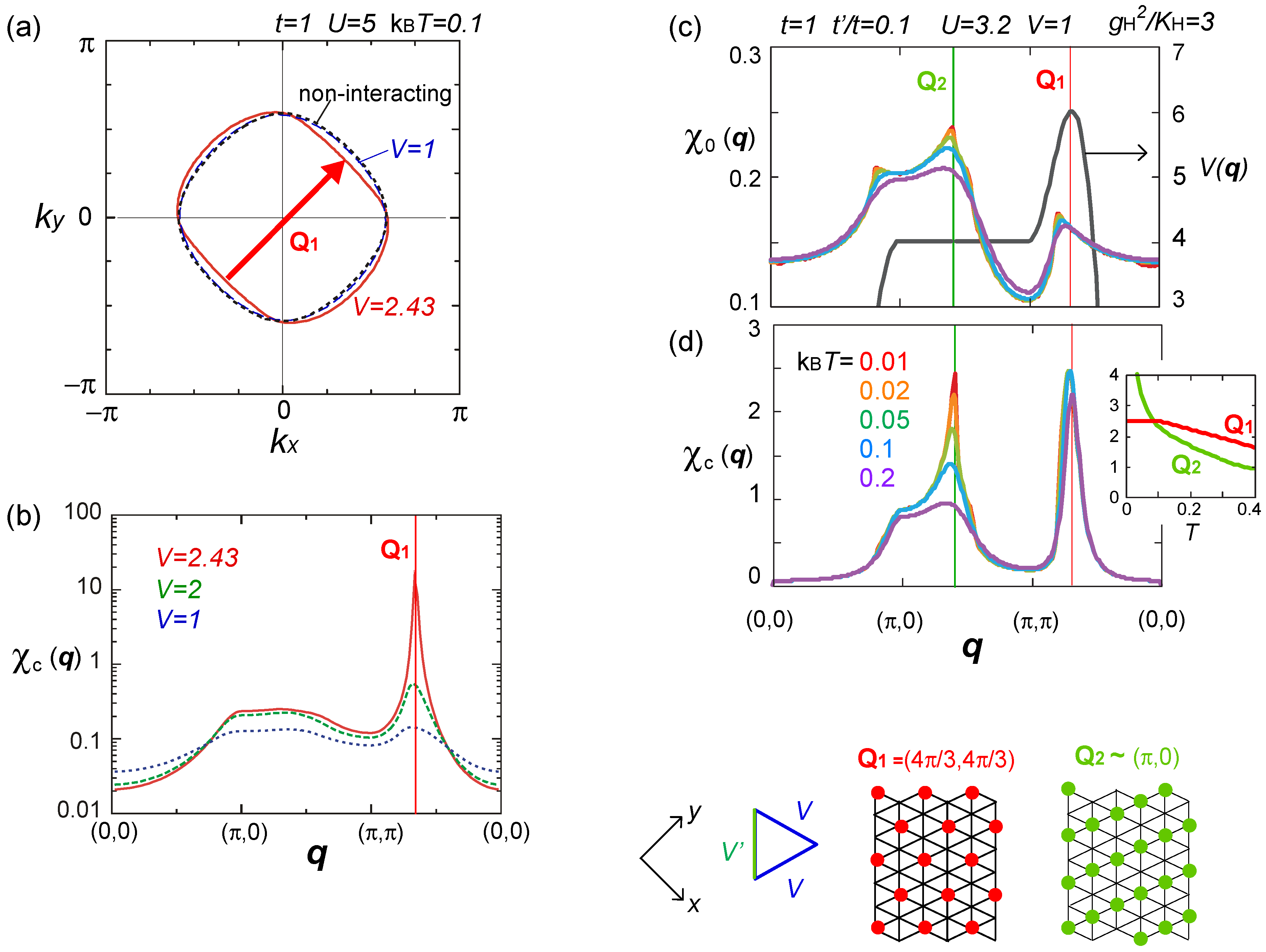

, is adopted as χ(q).

, is adopted as χ(q).  , is obtained from the full one-particle Greens’s function G(k) including the self-energy term, Σ(k). The effect of charge fluctuation that modifies the self energy (or equivalently the Fermi surface) through the exchange interaction,

, is obtained from the full one-particle Greens’s function G(k) including the self-energy term, Σ(k). The effect of charge fluctuation that modifies the self energy (or equivalently the Fermi surface) through the exchange interaction,  , is then taken into account by determining these quantities self-consistently. Such effect not included in RPA is visible in χc(q) by FLEX through the modification of χ(q) from the bare χ0 (q). Now, the self-consistent Hartree–Fock approximation could also include the modification of the self energy through the effective transfer integral,

, is then taken into account by determining these quantities self-consistently. Such effect not included in RPA is visible in χc(q) by FLEX through the modification of χ(q) from the bare χ0 (q). Now, the self-consistent Hartree–Fock approximation could also include the modification of the self energy through the effective transfer integral,  , via the Fock terms. However, without the feedback of higher order fluctuation effects to Σ(k), it is insufficient to discuss the modification of Fermi surface [75].

, via the Fock terms. However, without the feedback of higher order fluctuation effects to Σ(k), it is insufficient to discuss the modification of Fermi surface [75].  ), obtained by the RPA calculation. Adapted with permission from [76], copyrighted by the American Physical Society. The lower panels indicate the charge ordering pattern corresponding to the Q1 and Q2 wave numbers.

), obtained by the RPA calculation. Adapted with permission from [76], copyrighted by the American Physical Society. The lower panels indicate the charge ordering pattern corresponding to the Q1 and Q2 wave numbers.

), obtained by the RPA calculation. Adapted with permission from [76], copyrighted by the American Physical Society. The lower panels indicate the charge ordering pattern corresponding to the Q1 and Q2 wave numbers.

), obtained by the RPA calculation. Adapted with permission from [76], copyrighted by the American Physical Society. The lower panels indicate the charge ordering pattern corresponding to the Q1 and Q2 wave numbers.

) effectively formed along these stripes is enhanced, and the resultant energy gain works as an advantage to stabilize the horizontal charge ordering. They consider that such rather unusual modulation comes from the rotation of the molecules. Once gP >0, this modulation is stable even in the three-fold charge ordered state, in which the texture of charges show coexistence of two periods [78]. The coexisting two orders in the mean-field level shall turn into the above competing short range charge fluctuation at Q1 and Q2, when the electronic correlation is taken into account.

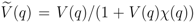

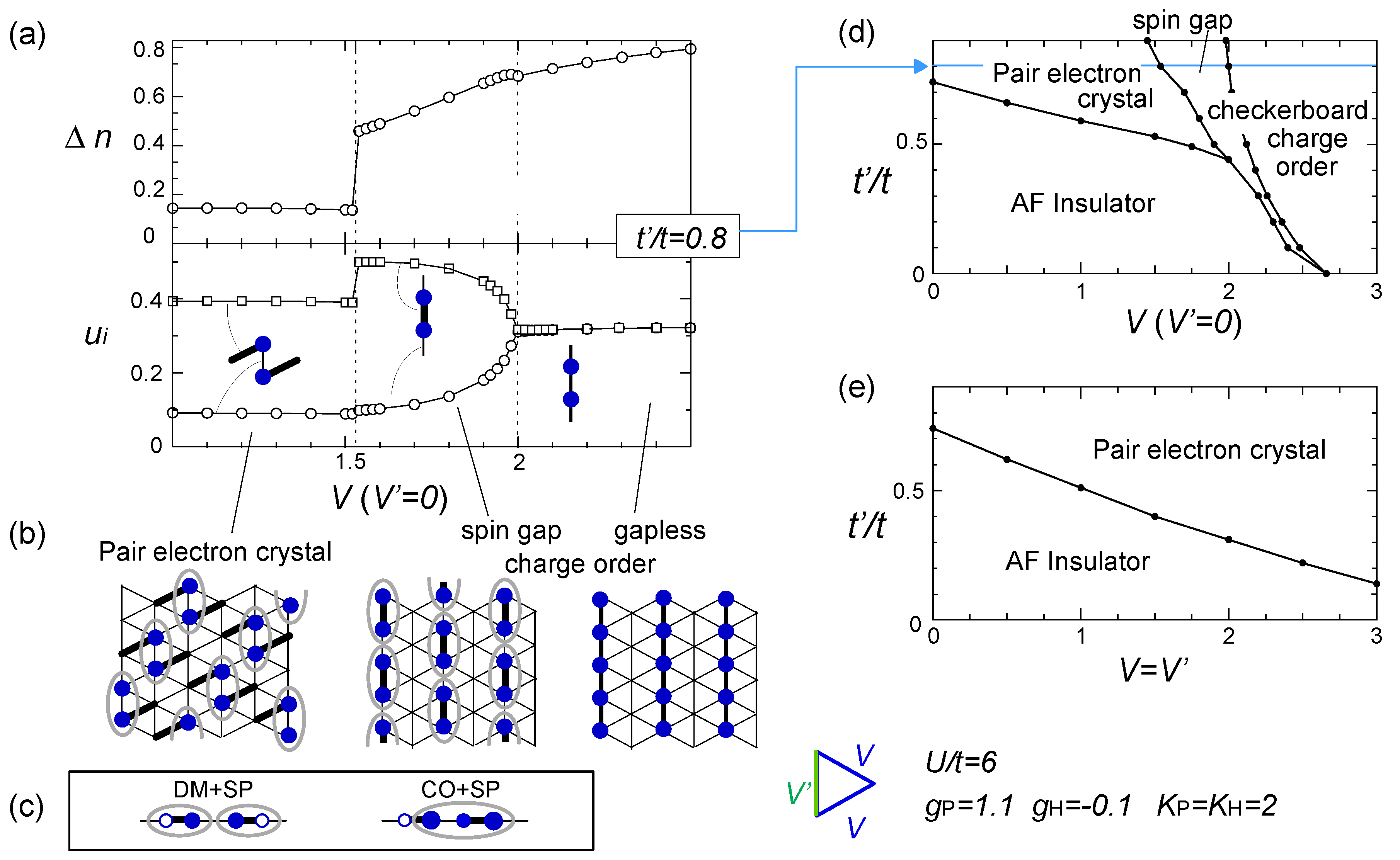

) effectively formed along these stripes is enhanced, and the resultant energy gain works as an advantage to stabilize the horizontal charge ordering. They consider that such rather unusual modulation comes from the rotation of the molecules. Once gP >0, this modulation is stable even in the three-fold charge ordered state, in which the texture of charges show coexistence of two periods [78]. The coexisting two orders in the mean-field level shall turn into the above competing short range charge fluctuation at Q1 and Q2, when the electronic correlation is taken into account. ) along the vertical bond (“-”), as shown in Figure 19(b). This state could be identified as the one referred to as DM + SP (dimer Mott-spin Peierls state) reported in the quantum Monte Carlo study by Otsuka et al. [80], and is discriminated from the spin gapped charge order which we roughly make correspondence with the CO + SP (charge ordered-spin Peierls state) (see Figure 19(c)). The phase diagram at V′ = 0 (square lattice-V) in Figure 19(d) is consistent with those of Otsuka et al.; the pair-electron crystal (DM + SP) turns into the spin gapped charge order (CO + SP) with increasing V, and finally a normal charge order without lattice distortion (ui = 0) sets in. Dayal et al. further showed in Figure 19(e) that the geometrical frustration, V = V′, completely replaces the charge ordered phases with the pair-electron crystal. To understand this result, recall our discussions in Section 3.3—the geometrical frustration in V destabilized the charge order against the dimer Mott insulator. The similar picture shall apply here by regarding the pair-electron crystal as an analogue of the dimer Mott insulator. However, compared to the pure dimer Mott case, the pair-electron crystal is more significantly stabilized, possibly owing to the spin degrees of freedom or to the spontaneous lattice modulation instead of the intrinsic dimerization. The increasing degrees of freedom thus could cope much better to release the frustration of V.

) along the vertical bond (“-”), as shown in Figure 19(b). This state could be identified as the one referred to as DM + SP (dimer Mott-spin Peierls state) reported in the quantum Monte Carlo study by Otsuka et al. [80], and is discriminated from the spin gapped charge order which we roughly make correspondence with the CO + SP (charge ordered-spin Peierls state) (see Figure 19(c)). The phase diagram at V′ = 0 (square lattice-V) in Figure 19(d) is consistent with those of Otsuka et al.; the pair-electron crystal (DM + SP) turns into the spin gapped charge order (CO + SP) with increasing V, and finally a normal charge order without lattice distortion (ui = 0) sets in. Dayal et al. further showed in Figure 19(e) that the geometrical frustration, V = V′, completely replaces the charge ordered phases with the pair-electron crystal. To understand this result, recall our discussions in Section 3.3—the geometrical frustration in V destabilized the charge order against the dimer Mott insulator. The similar picture shall apply here by regarding the pair-electron crystal as an analogue of the dimer Mott insulator. However, compared to the pure dimer Mott case, the pair-electron crystal is more significantly stabilized, possibly owing to the spin degrees of freedom or to the spontaneous lattice modulation instead of the intrinsic dimerization. The increasing degrees of freedom thus could cope much better to release the frustration of V.

5. Experimental Findings

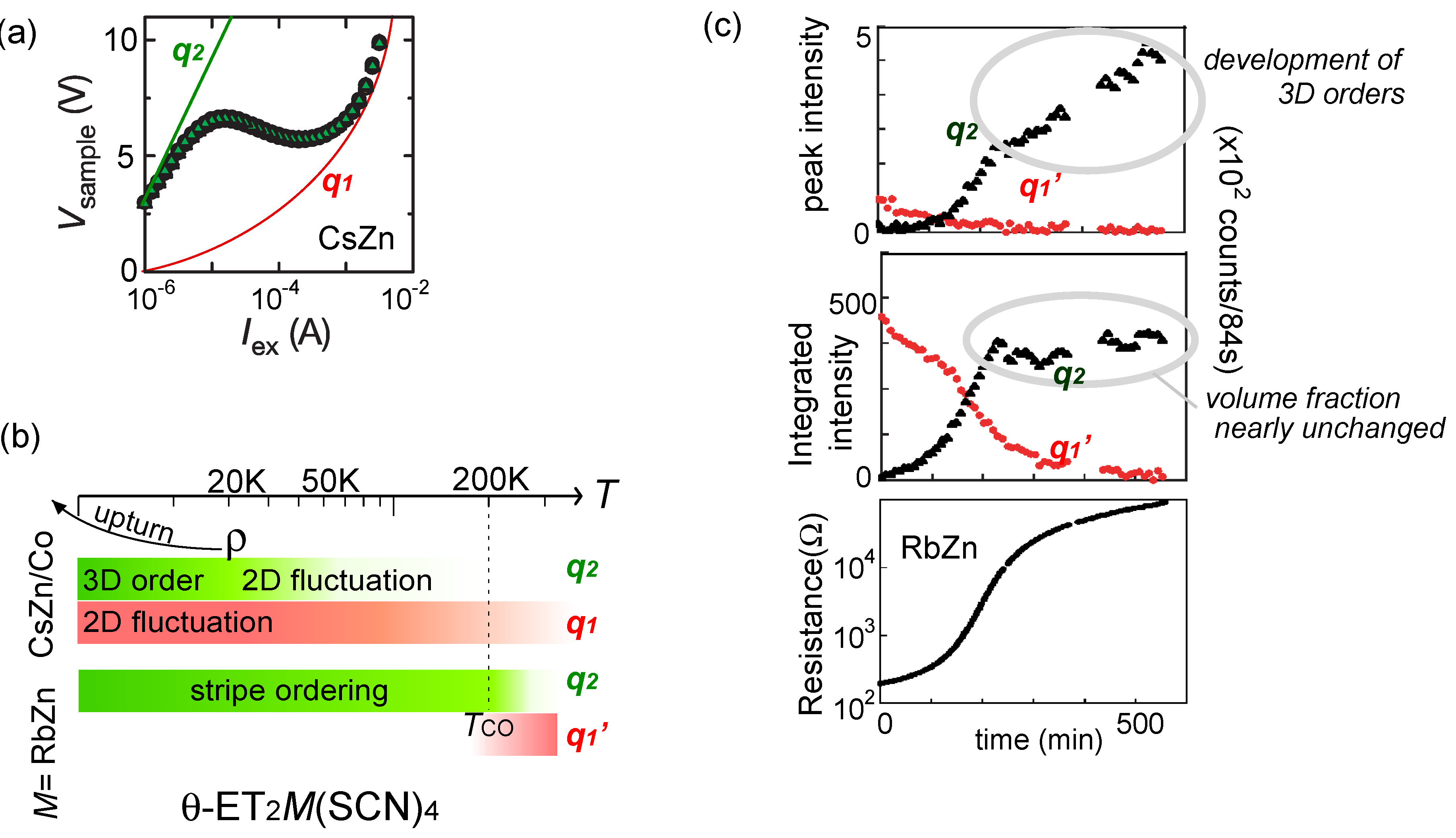

5.1. Competing Orders

5.2. Collective Charge Excitations

5.3. Spin Liquids, Dielectrics

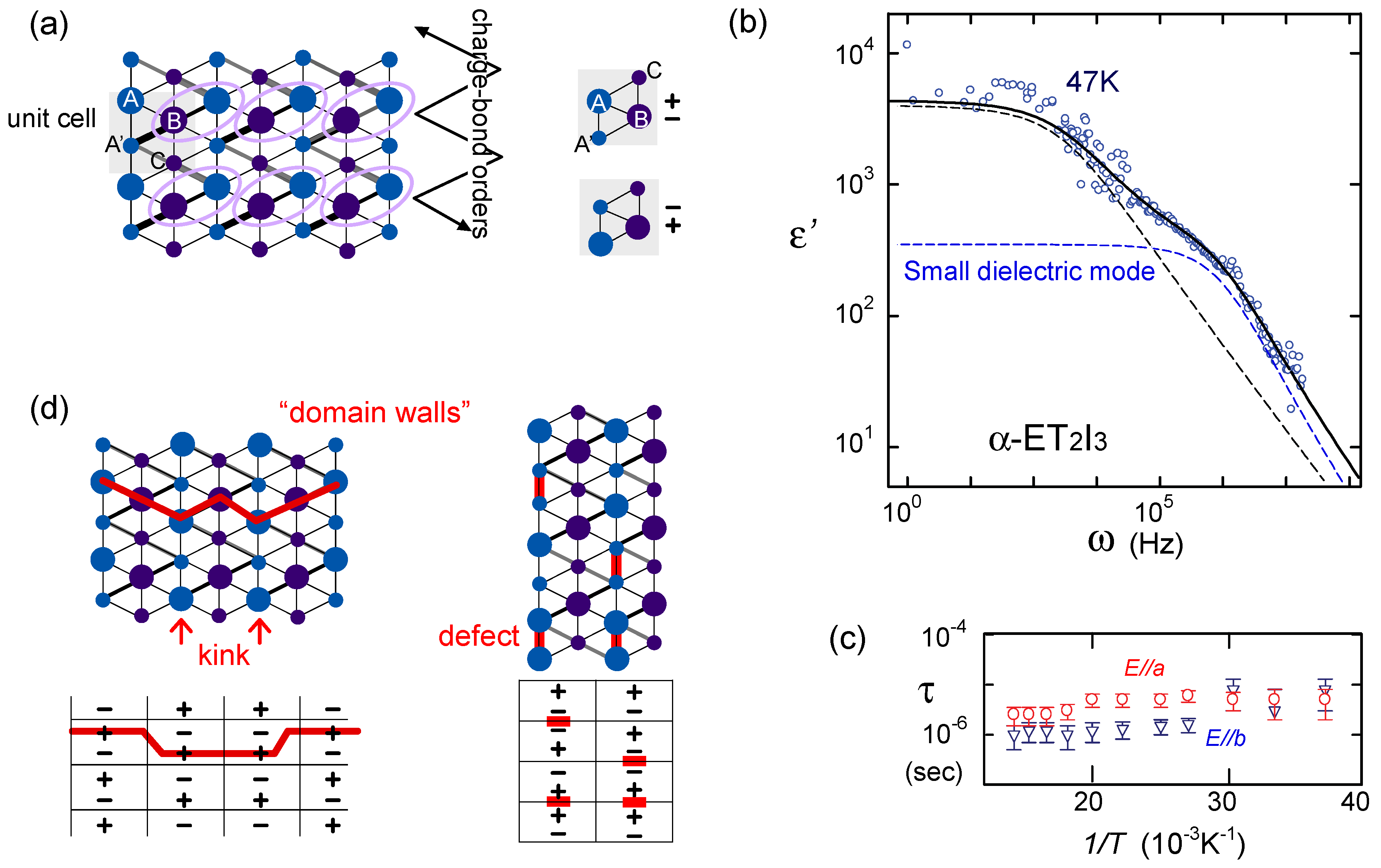

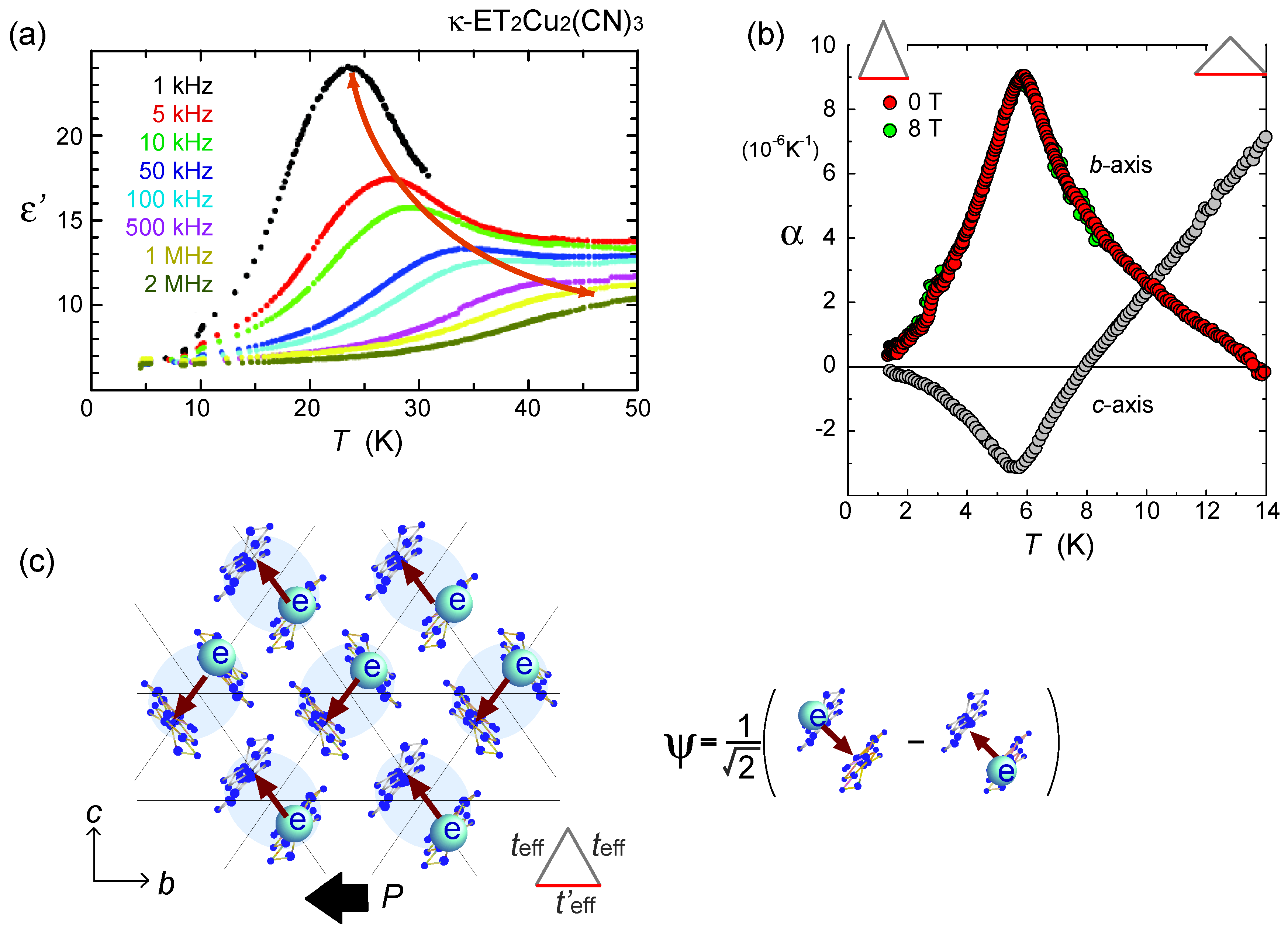

, with l being the distance of dimerized molecules, gives the experimental estimate, q = 0.1e, from the Curie–Weiss plot of the tail of the dielectric constant. As shown in Figure 22(c), the anti-bonding wave function ψ on a dimer indicates the strong quantum fluctuation of an electric dipole. When the correlation between different dipoles develops by the Coulomb interaction V, the macroscopic ferroelectric moment P could appear. Naka and Ishihara [104] also studied the model equivalent to the dipole-spin one, by the mean field and classical Monte Carlo method, presenting a clear picture of the ferroelectric charge order (dipolar order). Gomi et al. showed in their calculation that these dipoles contribute to a characteristic collective mode in a terahertz frequency region [105]. Thus, the theories began to reconcile with part of the experiments. From the exact diagonalization on the dipole-spin model, Hotta even found a possible “nonmagnetic” dimer Mott phase in the vicinity of transition to a ferroelectric ordering, in which the magnetic correlation becomes structureless for all k-numbers [20]. The origin of this “spin disorder” is the direct spin-charge coupling (see also Section 3.3), different from those of Section 3.4.

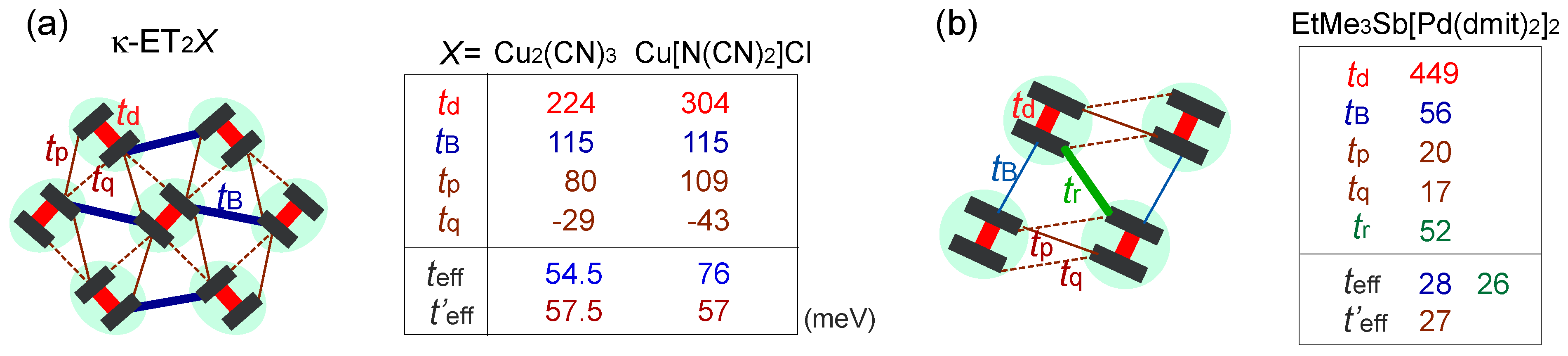

, with l being the distance of dimerized molecules, gives the experimental estimate, q = 0.1e, from the Curie–Weiss plot of the tail of the dielectric constant. As shown in Figure 22(c), the anti-bonding wave function ψ on a dimer indicates the strong quantum fluctuation of an electric dipole. When the correlation between different dipoles develops by the Coulomb interaction V, the macroscopic ferroelectric moment P could appear. Naka and Ishihara [104] also studied the model equivalent to the dipole-spin one, by the mean field and classical Monte Carlo method, presenting a clear picture of the ferroelectric charge order (dipolar order). Gomi et al. showed in their calculation that these dipoles contribute to a characteristic collective mode in a terahertz frequency region [105]. Thus, the theories began to reconcile with part of the experiments. From the exact diagonalization on the dipole-spin model, Hotta even found a possible “nonmagnetic” dimer Mott phase in the vicinity of transition to a ferroelectric ordering, in which the magnetic correlation becomes structureless for all k-numbers [20]. The origin of this “spin disorder” is the direct spin-charge coupling (see also Section 3.3), different from those of Section 3.4.  is more complicated) at lower temperature. The anomaly at 6 K may be understood in this direction, if the temperature dependence of the model parameters could be made clear. In order to perform comparative discussions, ab-initio calculations on other materials such as κ-ET2Cu[N(CN)2]Cl, EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2, and also the ones on the molecular-based models (not in unit of dimers) are awaited. At present, the semi-empirical evaluation of the transfer integrals at hand [14,106,107] summarized in Figure 23 provides a hint to understand the difference between materials; the degree of dimerization against other transfer integral yields td/tB ~ 2, 2.6, and 7 for κ-ET2Cu2(CN)3, κ-ET2Cu[N(CN)2]Cl and EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2, respectively. For example, if one assumes U/tB = 10 and Vd/tB = 6, the dimer approximation in Equation (5) gives Ueff/teff = 5:8 for κ-type and 12 for the dmit salt. The charge gap should accordingly be very large in the latter. At least, we could argue that the EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2 is a “clean” Mott insulator well approximated by the single band Hubbard model, whereas κ-ET2Cu2(CN)3 is a “dirty” Mott insulator since the intra-dimer degrees of freedom must be accounted for in such cases where td/V is relatively smaller. The origin of “the spin liquid” state may thus differ between the two.

is more complicated) at lower temperature. The anomaly at 6 K may be understood in this direction, if the temperature dependence of the model parameters could be made clear. In order to perform comparative discussions, ab-initio calculations on other materials such as κ-ET2Cu[N(CN)2]Cl, EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2, and also the ones on the molecular-based models (not in unit of dimers) are awaited. At present, the semi-empirical evaluation of the transfer integrals at hand [14,106,107] summarized in Figure 23 provides a hint to understand the difference between materials; the degree of dimerization against other transfer integral yields td/tB ~ 2, 2.6, and 7 for κ-ET2Cu2(CN)3, κ-ET2Cu[N(CN)2]Cl and EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2, respectively. For example, if one assumes U/tB = 10 and Vd/tB = 6, the dimer approximation in Equation (5) gives Ueff/teff = 5:8 for κ-type and 12 for the dmit salt. The charge gap should accordingly be very large in the latter. At least, we could argue that the EtMe3Sb[Pd(dmit)2]2 is a “clean” Mott insulator well approximated by the single band Hubbard model, whereas κ-ET2Cu2(CN)3 is a “dirty” Mott insulator since the intra-dimer degrees of freedom must be accounted for in such cases where td/V is relatively smaller. The origin of “the spin liquid” state may thus differ between the two. K, the inter-layer antiferroelectric phase appears (without the SHG signal), and it turns into a ferroeletric phase at T < 160 K, where the SHG signal sets in. These phases, now under investigation, are possibly related to the competition of the stripe orders [110]. Such new technique have drawn attention, because of the difficulty to elucidate experimentally the proper dielectric response in a sample with relatively high conductance. Indeed, many oxides containing mixed valent cations, displaying an insulating behavior and a defect-related conductivity at the same time, could easily display high dielectric constants as an artifact of inhomogeneity induced in samples, which are not related to the bulk ferroelectric polarization—it is called the Maxwell–Wagner-type of response [111]. In frustrated systems, such inhomogeneity may easily take place, and due to the relatively small charge gap, the organic crystals could also fall into this set-up. The careful examinations in the studies of “electronic dielectrics” is now strongly demanded.

K, the inter-layer antiferroelectric phase appears (without the SHG signal), and it turns into a ferroeletric phase at T < 160 K, where the SHG signal sets in. These phases, now under investigation, are possibly related to the competition of the stripe orders [110]. Such new technique have drawn attention, because of the difficulty to elucidate experimentally the proper dielectric response in a sample with relatively high conductance. Indeed, many oxides containing mixed valent cations, displaying an insulating behavior and a defect-related conductivity at the same time, could easily display high dielectric constants as an artifact of inhomogeneity induced in samples, which are not related to the bulk ferroelectric polarization—it is called the Maxwell–Wagner-type of response [111]. In frustrated systems, such inhomogeneity may easily take place, and due to the relatively small charge gap, the organic crystals could also fall into this set-up. The careful examinations in the studies of “electronic dielectrics” is now strongly demanded.

6. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

References

- Wannier, G.H. Antiferromagnetism: The triangular ising net. Phys. Rev. 1950, 79, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulouse, G. Theory of the frustration effect in spin glasses. Commun. Phys. 1977, 2, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Diep, H.T. Frustrated Spin Systems; World Scientific: Singapore, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Noda, Y.; Imada, M. Quantum phase transitions to charge-ordered and wigner-crystal states under the interplay of lattice commensurability and long-range coulomb interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H. Charge ordering in organic ET compounds. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2000, 69, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kino, H.; Fukuyama, H. Electronic states of conducting organic κ-(BEDT-TTF)2X. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1995, 64, 2726–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Hotta, C.; Fukuyama, H. Toward systematic understanding of diversity of electronic properties in low dimensional molecular solid. Chem. Rev. 2004, 105, 5005–5036. [Google Scholar]

- Hotta, C. Classification of quasi-two-dimensional organic conductors based on a new minimal model. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2003, 72, 840–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, T.; Kobayashi, A.; Sasaki, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Saito, G.; Inokuchi, H. The intermolecular interaction of tetrathiafulvalene and bis(ethylenedithio)tetrathiafulvalene in organic metals: Calculation of orbital overlaps and models of energy-band structures. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1984, 57, 627–633, and references therein.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, T.; Terakura, K.; Morikawa, Y.; Yamasaki, T. First-principles theoretical study of metallic states of DCNQI-(Cu,Ag) systems: Simplicity and variety in complex systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1995, 74, 5104–5107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, M.; Kuroda, H.; Uji, S.; Aoki, H.; Tokumoto, M.; Swanson, A.G.; Brooks, J.S.; Agosta, C.C.; Hannahs, S.T. Analysis of de Haas-van alphen oscillations and band structure of an organic superconductor, θ-(BEDT-TTF)2I3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1994, 63, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandpal, H.C.; Opahle, I.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Jeschke, H.O.; Valentí, R. Revision of model parameters for κ-type charge transfer salts: An Ab initio study. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Yoshimoto, Y.; Kosugi, T.; Arita, R.; Imada, M. Ab initio derivation of low-energy model for κ-ET type organic conductors. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, T.; Masukawa, N.; Inoue, T.; Saito, G. Realization of superconductivity at ambient pressure by band-filling control in κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1996, 65, 1340–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsch, A.; Ducassee, L. A valence-bond approach to the electronic localization in 3/4 filled systems. J. Phys. Fr. 1991, I1, 855–880. [Google Scholar]

- Mori, T. Estimation of off-sote coulomb integrals and phase diagrams of charge ordered states in the θ-phase organic conductors. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2000, 73, 2243–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriven, E.; Powell, B.J. Toward the parametrization of the Hubbard model for salts of bis(ethylenedithio)tetrathiafulvalene: A density functional study of isolated molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 2009, 130, 104508:1–104508:10. [Google Scholar]

- Mila, F. Deducing correlation parameters from optical conductivity in the Bechgaard salts. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 52, 4788–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In one dimension, taking U = ∞ in the extended Hubbard model exactly gives the t-V model as a Hamiltonian of the charge sector. In contrast, in two and three dimensions, the fermionic exchange sign requires complicated extra phases in the fermionic operator mapped from the electron operator, thus the two are only roughly, but not exactly, equivalent.

- Hotta, C. Quantum electric dipoles in spin-liquid dimer Mott insulator, κ-ET2Cu2(CN)3. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 241104:1–241104:4. [Google Scholar]

- Feiner, L.F.; Oleś, A.M.; Zaanen, J. Quantum melting of magnetic order due to orbital Fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1997, 78, 2799–2802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoji, I. Statistics of kagomé lattice. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1951, 6, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corruccini, L.R.; White, S.J. Dipolar antiferromagnetism in the spin-wave approximation. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 47, 773–777. [Google Scholar]

- Villain, J.; Bidaux, R.; Carton, J.-P.; Conte, R. Order as an effect of disorder. J. Phys. 1980, 41, 1263–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, C.; Furukawa, N.; Nakagawa, A.; Kubo, K. Phase diagram of spinless fermions on an anisotropic triangular lattice at half-filling. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 75, 123704:1–123704:6. [Google Scholar]

- Hotta, C.; Kiyota, T.; Furukawa, N. Dimensional crossover in the Ising antiferromagnet on the anisotropic triangular lattice at finite temperature. Europhys. Lett. 2011, 93, 47001:1–47001:6. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto, S.; Hotta, C. Density-matrix renormalization study of frustrated fermions on a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 79, 195124:1–195124:5. [Google Scholar]

- Hotta, C.; Furukawa, N. Strong coupling theory of the spinless charges on the triangular lattices: Possible formation of a gapless charge ordered liquid. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 193107:1–193107:4. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, M.; Hotta, C.; Miyahara, S.; Matsuda, K.; Furukawa, N. Variational monte carlo study of a spinless fermion t-V model on a triangular lattice: Formation of a pinball liquid. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- In the variational Monte Carlo study in [29], the plane wave function is used as a trial wave function, which is disadvantageous of realizing such long range order, to estimate the upper bound of the phase boundary, Vc = Vc′ ~ 12t. The DMRG result in [27] gives the lower estimate, Vc = Vc′ ~ 6t.

- Cano-Cortes, L.; Ralko, A.; F’evrier, C.; Merino, J.; Fratini, S. Geometrical frustration effects on charge-driven quantum phase transitions. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 80, 155115:1–155115:13. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, J.; Seo, H.; Ogata, M. Quantum melting of charge order due to frustration in two-dimensional quarter-filled systems. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 71, 125111:1–125111:5. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, H.; Ogata, M. Mean-field study of charge order with long periodicity in θ-(BEDT-TTF)2X. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 75, 063702:1–063702:4. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto, S.; Shingai, M.; Ohta, Y. Coexistence of distinct charge fluctuations in θ-(BEDT-TTF)2X. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 035113:1–035113:9. [Google Scholar]

- The VMC could afford a largest system size of N ~ 400 but assumes the trial wave function of a plane-wave type, and the possibility of better wave functions including more correlations always remains. At present, the DMRG result on a N = 8 × 6 cluster with m = 1400 could determine the energy within the accuracy of 10−2t, and thus may give relatively the most reliable result, while sometimes overestimating the ordered state due to boundary effects. The later study by the exact diagonalization in [31] shows quantitatively good agreement with the DMRG results [37].

- Kaneko, M.; Ogata, M. Mean-field study of charge order with long periodicity in θ-(BEDT-TTF)2X. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 75, 014710:1–014710:6. [Google Scholar]

- Nishimoto, S. Private communication, 2012. Leibniz Institute for Solid State and Materials Research, Dresden, Germany..

- Cano-Cortes, L.; Merino, J.; Fratini, S. Quantum critical behavior of electrons at the edge of charge order. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 036405:1–036405:4. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, J. Private communication, 2012. Universidad Autonoma de Madrid, Spain..

- Dressel, M. Quantum criticality in organic conductors? Fermi liquid versus non-Fermi-liquid behaviour. J. Phys. 2011, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaricci, A.; Camjayi, A.; Haule, K.; Kotliar, G.; Tanasković, D.; Dobrosavljević, V. Extended hubbard model: Charge ordering and wigner-mott transition. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 155102:1–155102:10. [Google Scholar]

- Hotta, C.; Pollmann, F. Dimensional tuning of electronic states under strong and frustrated interactions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 100, 186404:1–186404:4. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard, J. Generalized Wigner lattices in one dimension and some applications to tetracyanoquinodimethane (TCNQ) salts. Phys. Rev. B 1978, 17, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayr, M.; Horsch, P. Domain-wall excitations and optical conductivity in one-dimensional Wigner lattices. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 195103:1–195103:15. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Y.; Yonemitsu, K. Effects of electron-lattice coupling on charge order in θ-BEDT-TTF2X. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 76, 053708:1–053708:5. [Google Scholar]

- Fratini, S.; Merino, J. Unconventional metallic conduction in two-dimensional Hubbard–Wigner model lattices. Phys. Rev. B 2009, 80, 165110:1–165110:9. [Google Scholar]

- Pietig, R.; Bulla, R.; Blawid, B. Reentrant charge order transition in the extended hubbard model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 4046–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merino, J. Nonlocal coulomb correlations in metals close to charge order insulator transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 99, 036404:1–036404:4. [Google Scholar]

- Nad, F.; Monceau, P. Dielectric response of the charge ordered state in quasi-one-dimensional organic conductors. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 75, 051005:1–051005:12. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brink, J.; Khomskii, D.I. Multiferroicity due to charge ordering. J. Phys. 2008, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Tsuchiizu, M.; Seo, H. Charge-ordered state versus dimer-mott insulator at finite temperatures. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 76, 103701:1–103701:4. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuchiizu, M.; Yoshioka, H.; Suzumura, Y. Crossover from quarter-filling to half-filling in a one-dimensional electron system with a dimerized and quarter-filled band. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2001, 70, 1460–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.W. Resonating valence bonds: A new kind of insulator? Mat. Res. Bull. 1973, 8, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernu, B.; Lhuillier, C.; Pierre, L. Signature of neel order in exact spectra of quantum antiferromagnets on finite lattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1992, 69, 2590–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capriotti, L.; Trumper, A.E.; Sorella, S. Long-range neel order in the triangular heisenberg model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1999, 82, 3899–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trumper, A.E. Spin-wave analysis to the spatially anisotropic Heisenberg antiferromagnet on a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B. 1999, 60, 2987–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weihong, Z.; McKenzie, R.H. Phase diagram for a class of spin-1/2 Heisenberg models interpolating between the square-lattice, the triangular-lattice, and the linear-chain limits. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 14367–14375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misguich, G.; Lhuillier, C.; Bernu, B.; Waldtmann, C. Spin-liquid phase of the multiple-spin exchange Hamiltonian on the triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 1064–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Morita, H.; Watanabe, S.; Imada, M. Nonmagnetic insulating states near the mott transitions on lattices with geometrical frustration and implications for κ-(ET)2Cu2(CN)3. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2002, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koretsune, T.; Motome, Y.; Furusaki, A. Exact diagonalization study of mott transition in the hubbard model on an anisotropic triangular lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyung, B.; Tremblay, A.-M.S. Mott transition, antiferromagnetism, and d-wave superconductivity in two-dimensional organic conductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 97, 046402:1–046402:4. [Google Scholar]

- Clay, R.T.; Li, H.; Mazumdar, S. Absence of superconductivity in the half-filled band hubbard model on the anisotropic triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 166403:1–166403:4. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka, T.; Koga, A.; Kawakami, N. Quantum phase transitions in the hubbard model on a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 036401:1–036401:4. [Google Scholar]

- Kino, H.; Kontani, H. Phase Diagram of Superconductivity on the Anisotropic Triangular Lattice Hubbard Model: An Effective Model of κ-(BEDT-TTF) Salts. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 1998, 67, 3691–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Schmalian, J.; Trivedi, N. Pairing and superconductivity driven by strong quasiparticle renormalization in two-dimensional organic charge transfer salts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 127003:1–127003:4. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T.; Yokoyama, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Inoue, J. Superconductivity and a mott transition in a hubbard model on an anisotropic triangular lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 75, 074707:1–074707:15. [Google Scholar]

- Dayal, S.; Clay, R.T.; Mazumdar, S. Absence of long-range superconducting correlations in the frustrated half-filled-band Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 85, 165141:1–165141:8. [Google Scholar]

- The VMC calculation by Watanabe et al. [66] shows that the quasiparticle renormalization factor shows a jump at the transition from a d-SC to the Mott insulator, and its magnitude is enhanced with increasing t′/t. This fact is in agreement with the d-SC to NMI transition detected as a jump in the double occupancy by Kyung and Tremblay (CDMFT)[61].

- Mizusaki, T.; Imada, M. Gapless quantum spin liquid, stripe, and antiferromagnetic phases in frustrated Hubbard models in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, 014421:1–014421:10. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.-Y.; Läuchli, A.M.; Mila, F.; Schmidt, K.P. Effective spin model for the spin-liquid phase of the hubbard model on the triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 267204:1–267204:4. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.-S.; Lee, P.A. U(1) gauge theory of the Hubbard model: Spin liquid states and possible application to κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 95, 036403:1–036403:4. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, A.P. A flood or a trickle? Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 442–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motrunich, O.I. Variational study of triangular lattice spin-1 /2 model with ring exchanges and spin liquid state in κ-ET2Cu2(CN)3. Phys. Rev. B 2005, 72, 045105:1–045105:7. [Google Scholar]

- Zlatić, V.; Entel, P.; Grabowski, S. Spectral properties of two-dimensional Hubbard model with anisotropic hopping. Europhys. Lett. 1996, 34, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimi, K.; Kato, T.; Maebashi, H. Fermi surface deformation near charge-ordering transition. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2011, 80, 123707:1–123707:4. [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa, M.; Motome, Y. Charge ordering and coexistence of charge fluctuations in quasi-two-dimensional organic conductors θ-BEDT-TTF2X. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2007, 98, 206405:1–206405:4. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, M.; Noda, Y.; Nogami, Y.; Mori, H. Transfer Integrals and the Spatial Pattern of Charge Ordering in θ-(BEDT-TTF)2RbZn(SCN)4 at 90K. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2004, 73, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Yonemitsu, K. Nonlinear conduction by melting of stripe-type charge order in organic conductors with triangular lattices. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2011, 80, 103702:1–103702:4. [Google Scholar]

- Dayal, S.; Clay, T.; Li, H.; Mazumdar, S. Paired electron crystal: Order from frustration in the quarter-filled band. Phys. Rev. B. 2011, 83, 245106:1–245106:12. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, Y.; Seo, H.; Motome, Y.; Kato, T. Finite-temperature phase diagram of quasi-one-dimensional molecular conductors: Quantum monte carlo study. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2008, 77, 113705:1–113705:4. [Google Scholar]

- Kanoda, K. Metal-insulator transition in κ-(ET)2X and (DCNQI)2M: Two contrasting manifestation of electron correlation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 75, 051007:1–051007:16. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki, K. Theoretical aspects of charge correlations in θ-(BEDT-TTF)2X. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2009, 10, 024312:1–024312:11, and the references therein.. [Google Scholar]

- Sawano, F.; Terasaki, I.; Mori, H.; Mori, H.; Watanabe, M.; Ikeda, N.; Nogami, Y.; Noda, Y.F.; Sawano, I.; Terasaki, H.; et al. An organic thyristor. Nature 2005, 437, 522–524. [Google Scholar]

- Miyagawa, K.; Kawamoto, A.; Kanoda, K. Charge ordering in a quasi-two-dimensional organic conductor. Phys. Rev. B 2000, 62, R7679–R7682. [Google Scholar]

- Sawano, F.; Suko, T.; Inada, T.S.; Tasaki, S.; Terasaki, I.; Mori, H.; Nogami, Y.; Ikeda, N.; Watanabe, M.; et al. Current-density dependence of the charge-ordering gap in the organic salt θ-(BEDT-TTF)2CsZn(SCN)4 (M = Zn, Co, Co0.7Zn0.3). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 78, 024714:1–024714:5. [Google Scholar]

- Nogami, Y.; Hanasaki, N.; Watanabe, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Ito, T.; Ikeda, N.; Ohsumi, H.; Toyokawa, H.; Noda, Y.; Terasaki, I.; et al. Charge order competition leading to nonlinearity in organic thyristor family. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 79, 044606:1–044606:5. [Google Scholar]

- Yukawa, E.; Ogata, M. Mean-field analysis of electric field effect on charge orders in organic conductors. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 79, 023705:1–023705:4. [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki, K.; Terasaki, I.; Mori, H.; Mori, T. Large dielectric constant and giant nonlinear conduction in the organic conductor θ-(BEDT-TTF)2CsZn(SCN)X4. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2004, 73, 3364–3369. [Google Scholar]

- Kuroki, K. The origin of the charge ordering and its relevance to superconductivity in θ-(BEDT-TTF)2X: The effect of the fermi surface nesting and the distant electron.electron interactions. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2006, 75, 114716:1–114716:14. [Google Scholar]

- Ivek, T.; Korin-Hamzic, B.; Milat, O.; Tomic, S.; Clauss, C.; Drichko, N.; Schweitzer, D.; Dressel, M. Collective excitations in the charge-ordered phase of α-(BEDT-TTF)2I3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 206406:1–206406:4. [Google Scholar]

- Ivek, T.; Korin-Hamzic, B.; Milat, O.; Tomic, S.; Clauss, C.; Drichko, N.; Schweitzer, D.; Dressel, M. Electrodynamic response of the charge ordering phase: Dielectric and optical studies of α-(BEDT-TTF)2I3. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 165128:1–165128:13. [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi, T.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Sawa, H.; Takahashi, T.; Nakamura, Y. Charge ordering in α-(BEDT-TTF)2I3 by synchrotron X-ray diffraction. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2007, 76, 113702:1–113702:4. [Google Scholar]

- Kimber, S.A.J.; Senn, M.S.; Fratini, S.; Wu, H.; Hill, A.H.; Manuel, P.; Attfield, J.P.; Argyriou, D.N.; Henry, P.F. Charge order at the frontier between the molecular and solid states in Ba3NaRu2O9. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 217205:1–217205:4. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, R. Conducting metal dithiolene complexes: Structural and electronic properties. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 5319–5346. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, Y.; Miyagawa, K.; Kanoda, K.; Maesato, M.; Saito, G. Spin liquid state in an organic mott insulator with a triangular lattice. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003, 91, 107001:1–107001:4. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, S.; Nakazawa, Y.; Oguni, M.; Oshima, Y.; Nojiri, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Miyagawa, K.; Kanoda, K. Thermodynamic properties of a spin-1/2 spin-liquid state in a κ-type organic salt. Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 459–462. [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita, M.; Nakata, N.; Kasahara, Y.; Sasaki, T.; Yoneyama, N.; Kobayashi, N.; Fujimoto, S.; Shibauchi, T.; Matsuda, Y. Thermal-transport measurements in a quantum spin-liquid state of the frustrated triangular magnet κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3. Nat. Phys. 2008, 5, 44–47. [Google Scholar]

- Itou, T.; Oyamada, A.; Maegawa, S.; Kato, R. Instability of a quantum spin liquid in an organic triangular-lattice antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, S.; Yamamoto, T.; Nakazawa, Y.; Tamura, M.; Kato, R. Gapless spin liquid of an organic triangular compound evidenced by thermodynamic measurements. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashitam, M.; Nakata, N.; Senshu, Y.; Nagata, M.; Yamamoto, H.M.; Kato, R.; Shibauchi, T.; Matsuda, Y. Highly mobile gapless excitations in a two-dimensional candidate quantum spin liquid. Science 2010, 328, 1246–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Jawad, M.; Terasaki, I.; Sasaki, T.; Yoneyama, N.; Kobayashi, N.; Uesu, Y.; Hotta, C. Anomalous dielectric response in the dimer Mott insulator κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 125119:1–125119:5. [Google Scholar]

- Manna, R.S.; de Souza, M.; Bїuhl, A.; Schlueter, J.A.; Lang, M. Lattice effects and entropy release at the low-temperature phase transition in the spin-liquid candidate κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 104, 016403:1–016403:4. [Google Scholar]

- Lunkenheimer, P.; Müller, J.; Krohns, S.; Schrettle, F.; Loidl, A.; Hartmann, B.; Rommel, R.; de Souza, M.; Hotta, C.; Schlueter, J.A.; Lang, M. Multiferroicity in an organic charge-transfer salt: Electric-dipole-driven magnetism. Nat. Mater. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naka, M.; Ishihara, S. Electronic ferroelectricity in a dimer mott insulator. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2010, 79, 063707:1–063707:4. [Google Scholar]

- Gomi, H.; Imai, T.; Takahashi, A.; Aihara, M. Purely electronic terahertz polarization in dimer Mott insulators. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 82, 035101:1–035101:7. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, R.; Hengbo, C. Cation dependence of crystal structure and band parameters in a series of molecular conductors, β′-(Cation)[Pd(dmit)2]2 (dmit = 1,3-dithiole-2-thione-4,5-dithiolate). Crystals 2012, 2, 861–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Nogami, Y.; Oshima, K.; Ito, H.; Ishiguro, T.; Saito, G. Low temperature superstructure and transfer integrals in κ-(BEDT-TTF)2 Cu[N(CN)2]X: X = Cl, Br. Synth. Metals 1999, 103, 1909–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Iwai, S.; Boyko, S.; Kashiwazaki, A.; Hiramatsu, F.; Okabe, C.; Nishi, N.; Yakushi, K. Strong optical nonlinearity and its ultrafast response associated with electron ferroelectricity in an organic conductor. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2008, 77, 074709:1–074709:6. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K.; Kowalska, A.A.; Yakushi, K. Direct observation of ferroelectric domains created by Wigner crystallization of electrons in α-[bis(ethylenedithio)tetrathiafulvalene]2I3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 96, 122901:1–122901:3. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K. Private Communication, 2012. Institute for Molecular Science, Okazaki, Japan..

- Catalan, G.; Scott, J.F. Is CdCr2S4 a multiferroic relaxor? Nature 2007, 448, E4–E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kezsmarki, I.; Shimizu, Y.; Mihály, G.; Tokura, Y.; Kanoda, K.; Saito, G. Depressed charge gap in the triangular-lattice Mott insulator, κ-(ET)2Cu2(CN)3. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 74, R201101:1–R201101:14. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Hotta, C. Theories on Frustrated Electrons in Two-Dimensional Organic Solids. Crystals 2012, 2, 1155-1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2031155

Hotta C. Theories on Frustrated Electrons in Two-Dimensional Organic Solids. Crystals. 2012; 2(3):1155-1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2031155

Chicago/Turabian StyleHotta, Chisa. 2012. "Theories on Frustrated Electrons in Two-Dimensional Organic Solids" Crystals 2, no. 3: 1155-1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2031155

APA StyleHotta, C. (2012). Theories on Frustrated Electrons in Two-Dimensional Organic Solids. Crystals, 2(3), 1155-1200. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2031155