Lanthanide-Induced Local Structural and Optical Modulation in Low-Temperature Ag2Se

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results and Discussion

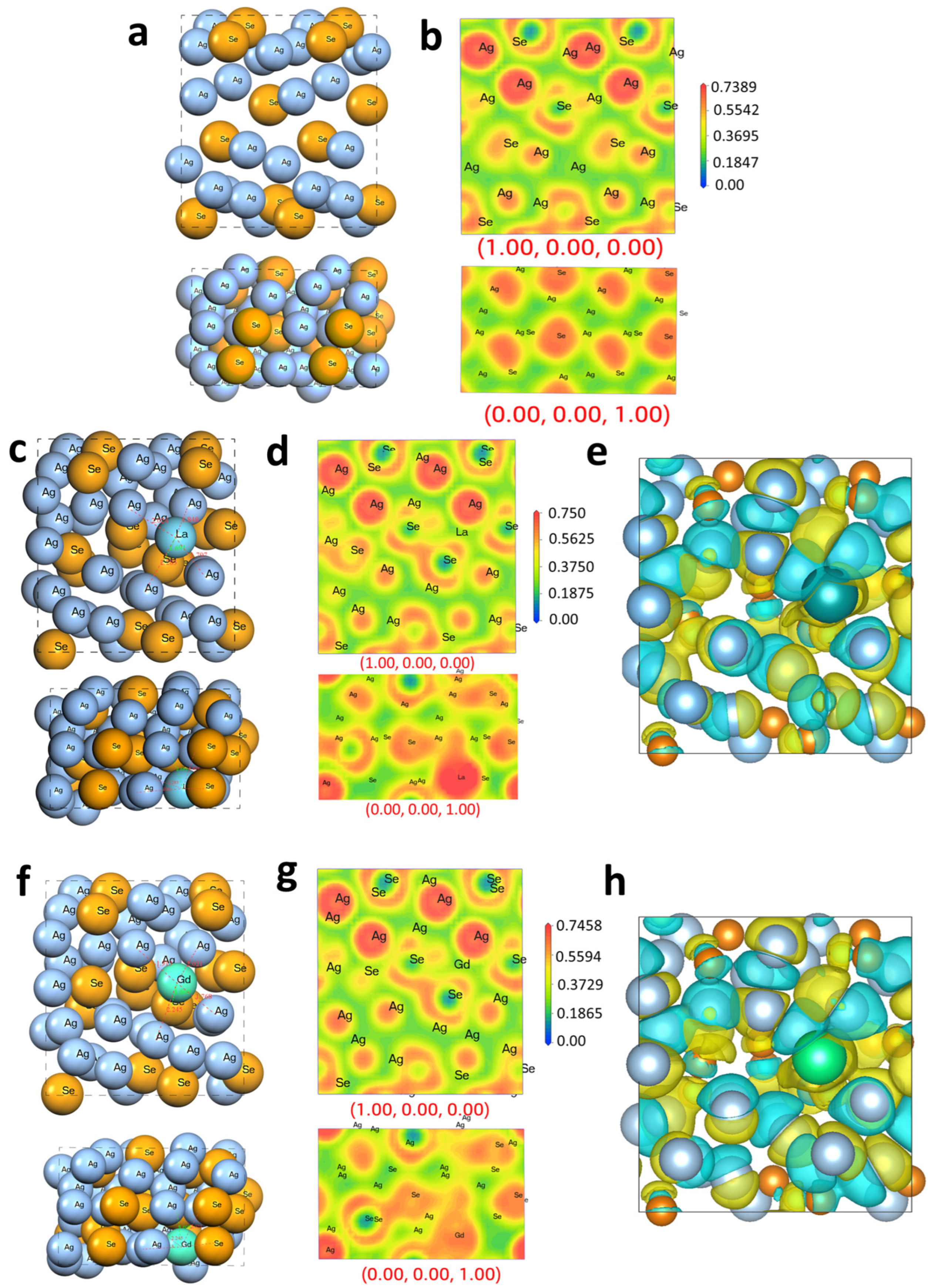

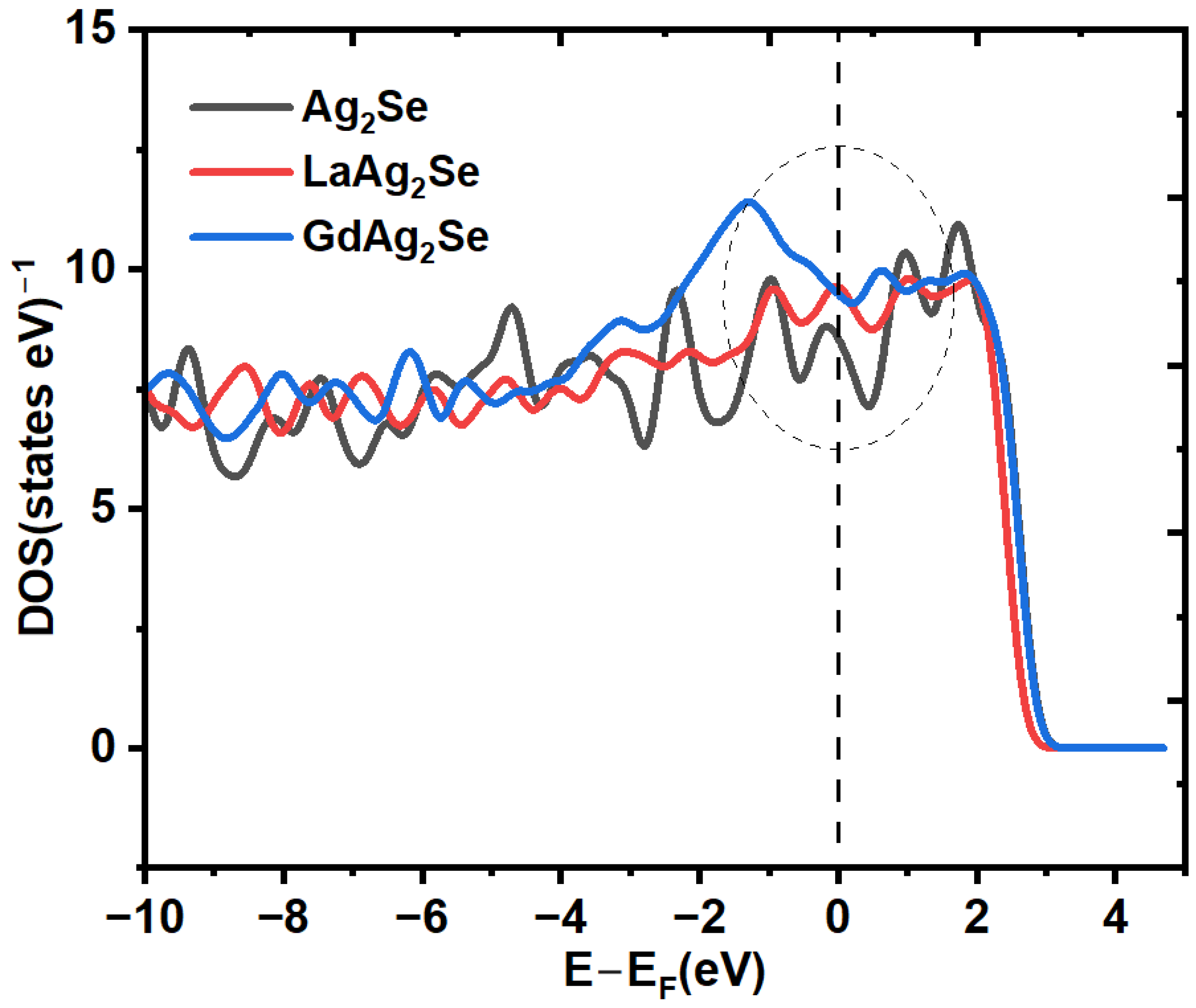

3.1. Electronic Properties of Ag2Se and La, Gd-Doped Ag2Se

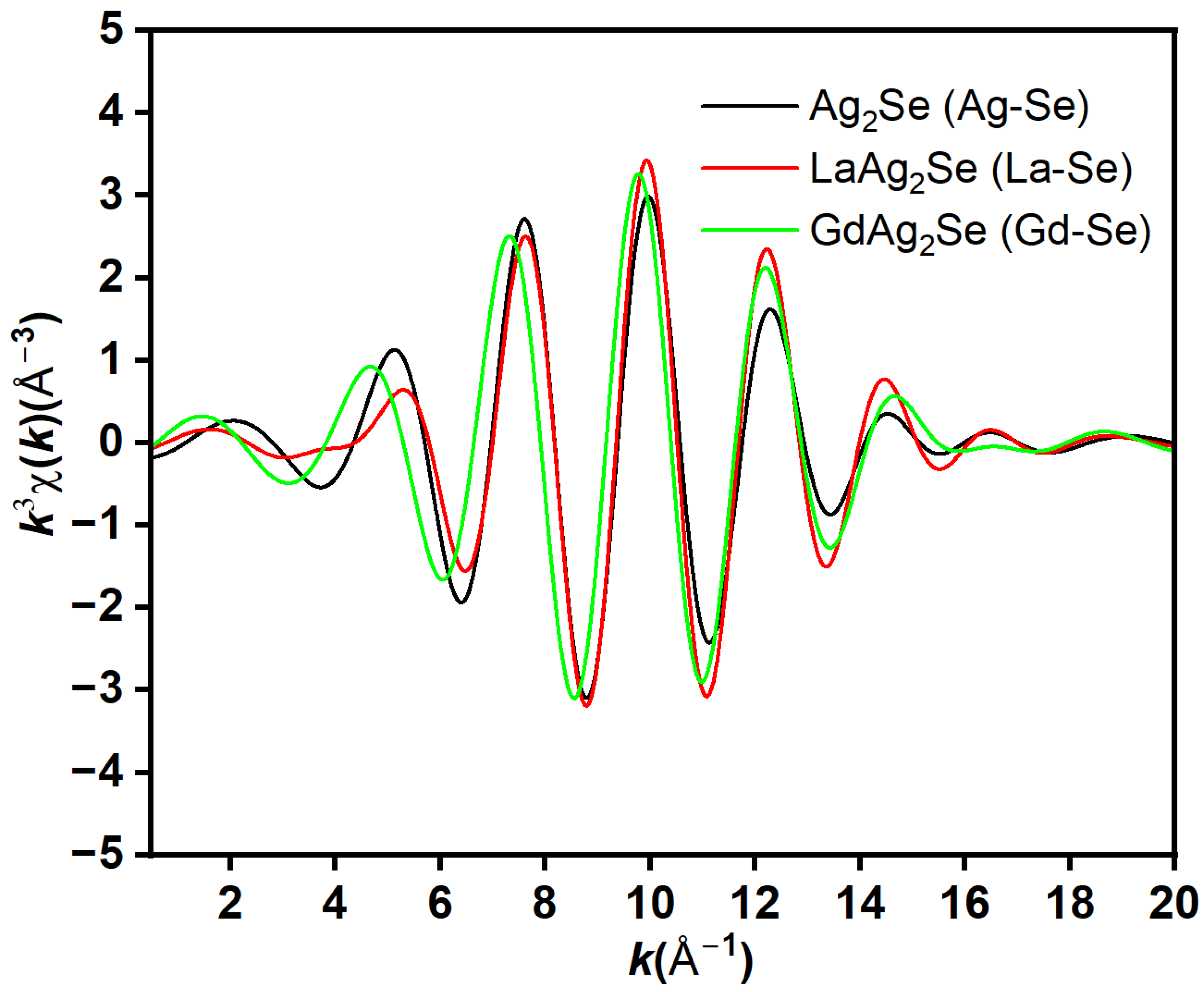

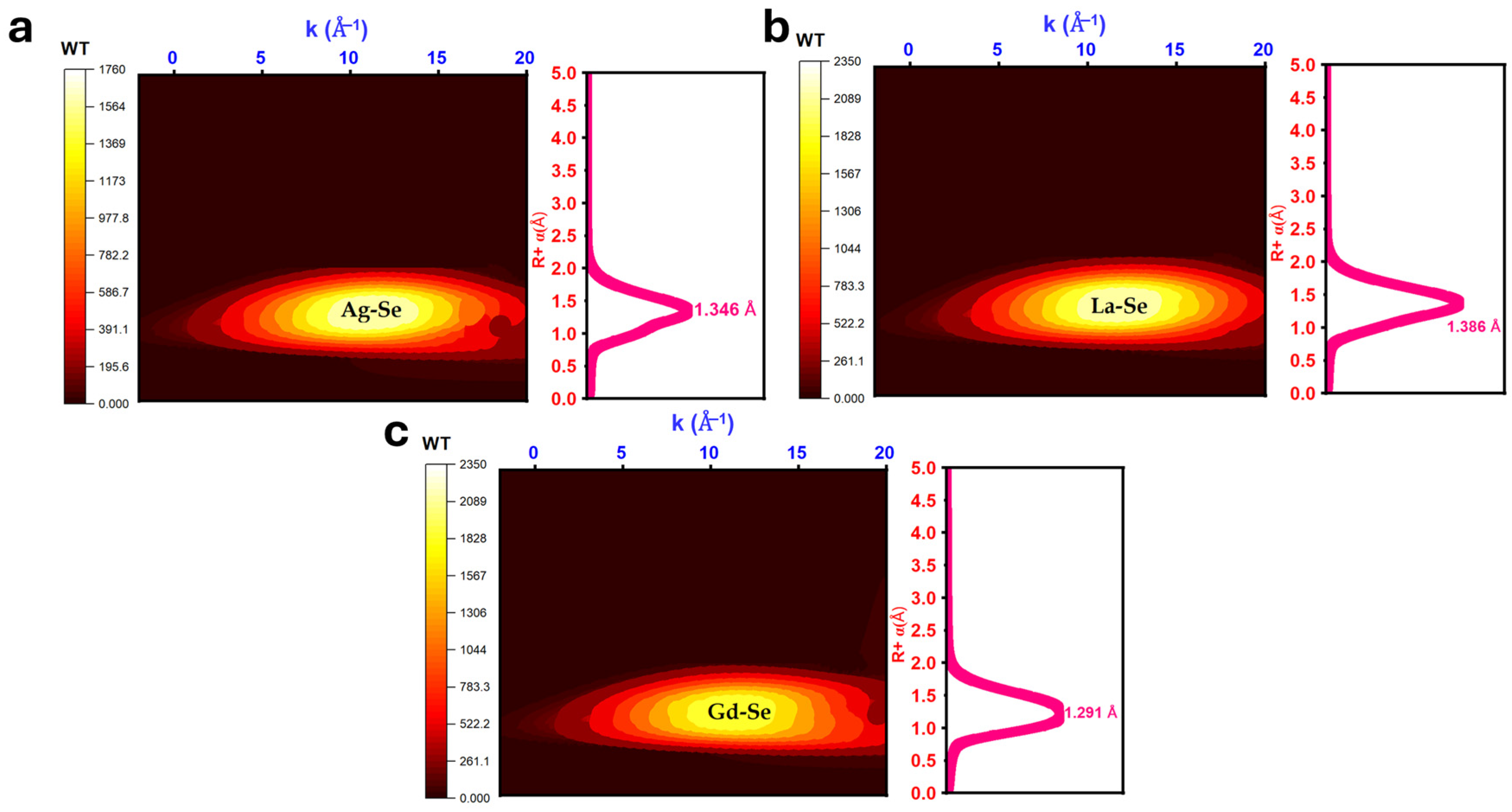

3.2. Extended X-Ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS)

3.3. Optical Properties

3.3.1. Dielectric Function

3.3.2. Absorption

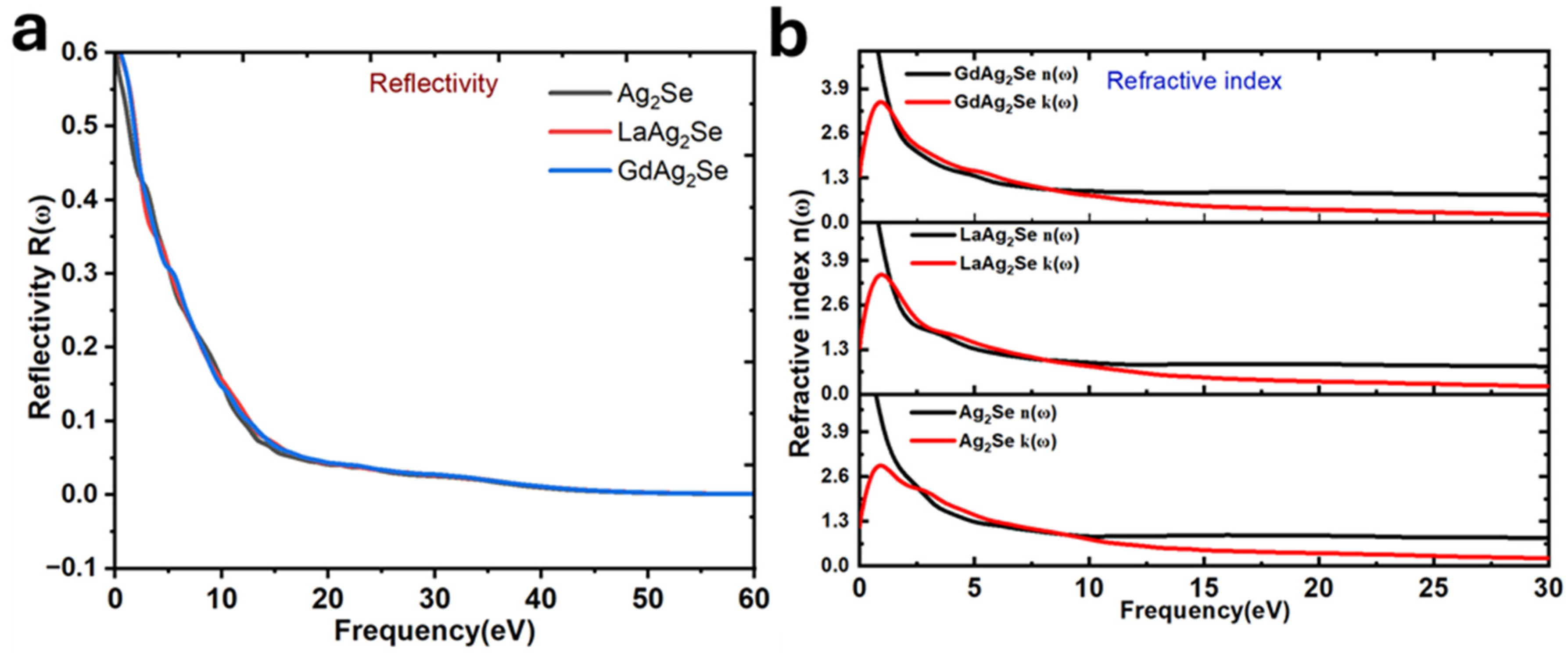

3.3.3. Reflectivity

3.3.4. Refractive Index (n, k)

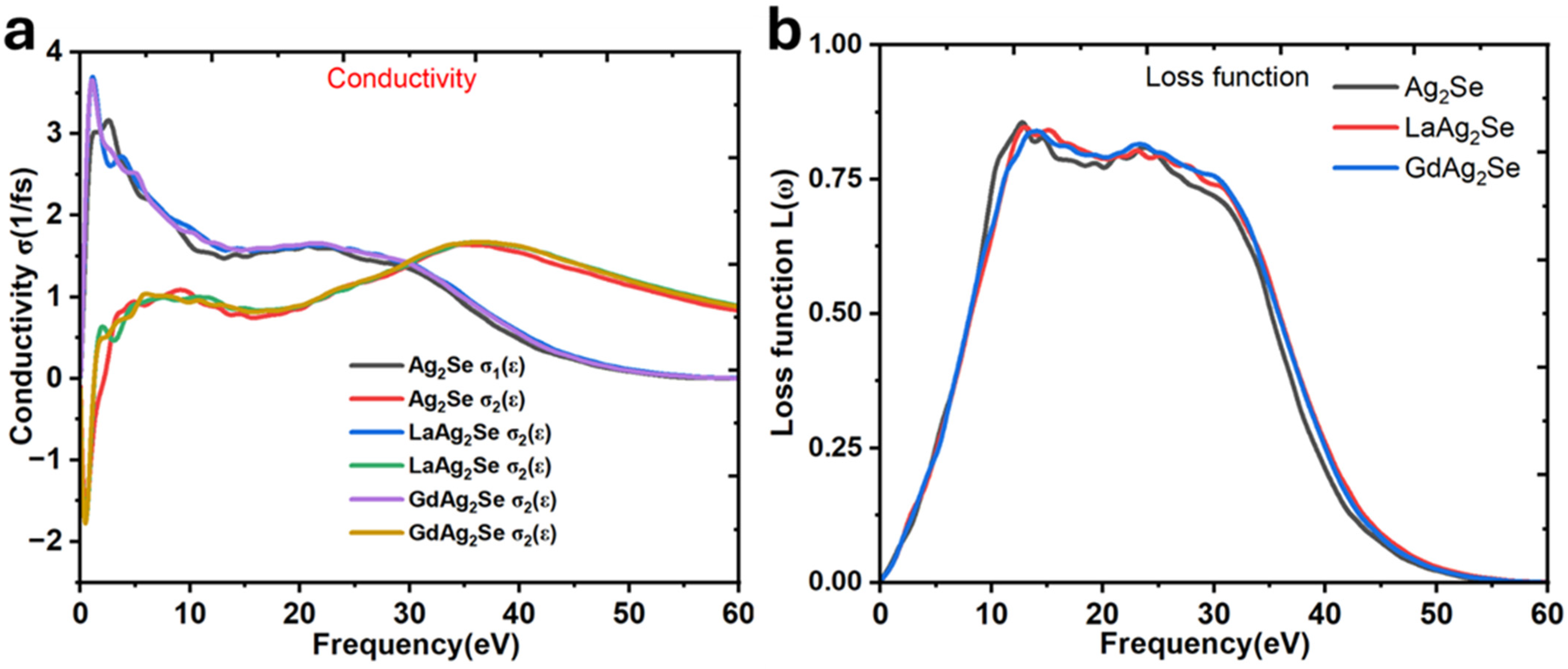

3.3.5. Optical Conductivity

3.3.6. Energy Loss Function

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, D.; Shi, X.-L.; Li, M.; Nisar, M.; Mansoor, A.; Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, F.; Ma, H.; Liang, G.X.; et al. Flexible power generators by Ag2Se thin films with record-high thermoelectric performance. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhang, M.; Jia, Y.; Li, J.; Gou, W.; Wang, Y.; Melzi, B.; Yan, Y.; Tang, X. Rapid low-temperature densification of Ag2Se bulk material: Mass transfer through the dissociative adsorption reaction of Ag protrusions and Se saturated vapor. Nanotechnology 2024, 35, 315702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Xia, Y.; Xu, L.; Zhao, M.; Li, M.; Cheng, Y.; Mao, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, L.; Tsang, S.W. Thermoelectric performance in Ag2Se nanocomposites: The role of interstitial Ag and Pb orbital hybridization. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 511, 162265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasiw, J.; Kamwanna, T.; Pinitsoontorn, S. Fast, Simple, and Cost-Effective Fabrication of High-Performance Thermoelectric Ag2Se through Low-Temperature Hot-Pressing. ChemNanoMat 2024, 10, e202400319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Gao, L.; Song, S.; Li, H.; Niu, G.; Chen, H.; Qian, T.; Ding, H.; Lin, X.; Du, S. Honeycomb AgSe monolayer nanosheets for studying two-dimensional dirac nodal line fermions. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2021, 4, 8845–8850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Luo, M.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Fan, T.; Ming, C.; Li, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Qiu, P.; Chen, L. Ag2Se Polymorphs: Structure Determination and Variations in Thermoelectric Properties. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 9277–9285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, R.K.; Pati, S.K. Computational approach to enhance thermoelectric performance of Ag 2 Se by S and Te substitutions. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2024, 26, 9340–9349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, L.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Li, L.; Huang, W. Adsorption of Gd3+ in water by N, S Co-doped La-based metal organic frameworks: Experimental and theoretical calculation. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 321, 123864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslandukov, A.; Jurzick, P.L.; Bykov, M.; Aslandukova, A.; Chanyshev, A.; Laniel, D.; Yin, Y.; Akbar, F.I.; Khandarkhaeva, S.; Fedotenko, T. Stabilization Of The CN35− Anion In Recoverable High-pressure Ln3O2 (CN3)(Ln= La, Eu, Gd, Tb, Ho, Yb) Oxoguanidinates. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202311516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröger, F.A.; Vink, H.J. Relations between the Concentrations of Imperfections in Crystalline Solids. In Solid State Physics; Seitz, F., Turnbull, D., Eds.; Solid State Physics; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1956; Volume 3, pp. 307–435. [Google Scholar]

- Yatsenko, A.V.; Gloriozov, I.P.; Zhokhova, N.I.; Paseshnichenko, K.A.; Aslanov, L.A.; Ustynyuk, Y.A. Structure of lanthanide nitrates in solution and in the solid state: DFT modelling of hydration effects. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 323, 115005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Flores, C.; Bolivar-Pineda, L.M.; Basiuk, V.A. Lanthanide bisphthalocyanine single-molecule magnets: A DFT survey of their geometries and electronic properties from lanthanum to lutetium. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2022, 287, 126271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Fan, J.; Chen, B.; Qin, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, F.; Deng, R.; Liu, X. Rare-Earth Doping in Nanostructured Inorganic Materials. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 5519–5603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xie, T.; Peng, Q.; Li, Y. Ag, Ag2S, and Ag2Se Nanocrystals: Synthesis, Assembly, and Construction of Mesoporous Structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 4016–4022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Shi, X.-L.; Hu, B.; Liu, S.; Lyu, W.; Li, M.; Wang, S.; Chen, W.; Liu, W.-D.; Moshwan, R.; et al. Indium-Doping Advances High-Performance Flexible Ag2Se Thin Films. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, 2500364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.-Y.; Chen, G.; Gu, Y.-P.; Cui, R.; Zhang, Z.-L.; Yu, Z.-L.; Tang, B.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Pang, D.-W. Ultrasmall Magnetically Engineered Ag2Se Quantum Dots for Instant Efficient Labeling and Whole-Body High-Resolution Multimodal Real-Time Tracking of Cell-Derived Microvesicles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 1893–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, S.; Yang, C.; Diao, Q.; Hong, Z.; Han, H.; Liu, L.; Xu, W. Long-range ordering and local structural disordering of BiAgSe 2 and BiAgSeTe thermoelectrics. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 24328–24335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, S.; Irfan, M.; Omran, S.B.; Khenata, R.; Adil, M.; Gul, B.; Muhammad, S.; Khan, G.; Haq, B.U.; Vu, T. V Electronic band structure and optical characteristic of silver lanthanide XAgSe2 (X= Eu and Er) dichalcogenides: Insight from DFT computations. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 129, 108586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smerigan, A.; Hoffman, A.S.; Ostervold, L.; Hong, J.; Perez-Aguillar, J.; Caine, A.C.; Greenlee, L.; Bare, S.R. Advanced EXAFS analysis techniques applied to the L-edges of the lanthanide oxides. Appl. Crystallogr. 2024, 57, 1913–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smerigan, A.; Biswas, S.; Vila, F.D.; Hong, J.; Perez-Aguilar, J.; Hoffman, A.S.; Greenlee, L.; Getman, R.B.; Bare, S.R. Aqueous Structure of Lanthanide–EDTA Coordination Complexes Determined by a Combined DFT/EXAFS Approach. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 14523–14532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, H.; Tahir, M.B.; Sagir, M.; Alrobei, H.; Alzaid, M.; Ullah, S.; Hussien, M. Effect of potassium on the structural, electronic, and optical properties of CsSrF3 fluro perovskite: First-principles computation with GGA-PBE. Optik 2022, 259, 168741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.X.; Nicholls, R.J.; Yates, J.R. Accurate and efficient structure factors in ultrasoft pseudopotential and projector augmented wave DFT. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 115112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Khan, A.Z. Investigation of Optoelectronic and Thermoelectric Properties of Gd-Doped Sr2MgGe2O7: A DFT+ U+ SOC Study for Exploring High-Performance LED Phosphors. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025, 207, 112898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Jiang, H. Combined DFT and wave function theory approach to excited states of lanthanide luminescent materials: A case study of LaF3: Ce3+. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2023, 70, 604–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theprattanakorn, D.; Kaewmaraya, T.; Pinitsoontorn, S. Boosting thermoelectric efficiency of Ag2Se through cold sintering process with Ag nano-precipitate formation. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 2760–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, J.D. Simulating the Crystal Structures and Properties of Ionic Materials From Interatomic Potentials. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2001, 42, 37–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Hwang, A.; Lee, S.-H.; Jhi, S.-H.; Lee, S.; Park, Y.C.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.-S.; Doh, Y.-J.; Kim, J.; et al. Quantum Electronic Transport of Topological Surface States in β-Ag2Se Nanowire. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3936–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, B.; Zeng, T.-X.; Wu, Y.-G.; Fu, Z.-J.; Zhou, Z.-W. Ab initio GGA+ U investigations of the electronic properties and magnetic orderings in Mn, Gd doped ZB/WZ structural CdSe. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 142, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finzel, J.; Sanroman Gutierrez, K.M.; Hoffman, A.S.; Resasco, J.; Christopher, P.; Bare, S.R. Limits of Detection for EXAFS Characterization of Heterogeneous Single-Atom Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2023, 13, 6462–6473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kompch, A.; Sahu, A.; Notthoff, C.; Ott, F.; Norris, D.J.; Winterer, M. Localization of Ag dopant atoms in CdSe nanocrystals by reverse Monte Carlo analysis of EXAFS spectra. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 18762–18772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T.V.; Lavrentyev, A.A.; Gabrelian, B.V.; Parasyuk, O.V.; Ocheretova, V.A.; Khyzhun, O.Y. Electronic structure and optical properties of Ag2HgSnSe4: First-principles DFT calculations and X-ray spectroscopy studies. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 732, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvam, S.P.; Cho, S. EXAFS and spectroscopic insights into Mn, Tc, and Re-doped phthalocyanines: A multifaceted DFT study of electronic and optical properties. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 56, 105610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Kumar, P.; Surolia, P.K.; Chakraborty, T. Structure, electronic and optical properties of chalcopyrite semiconductor AgTiX2 (X= S, Se, Te): A density functional theory study. Thin Solid Film. 2021, 717, 138469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S.; Din, H.U.; Murtaza, G.; Ouahrani, T.; Khenata, R.; Omran, S. Bin Structural, electronic and optical properties of AgXY2 (X= Al, Ga, in and Y= S, Se, Te). J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 617, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.H.R.; Jiang, J.; Yeoh, K.H.; Tuh, M.H.; Chiew, F.H. Prediction of stable silver selenide-based energy materials sustained by rubidium selenide alloying. New J. Chem. 2022, 46, 22050–22063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tse, G. The electronic, optical, and vibrational properties of Ag3X (X= S, Se) with density functional theory. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2023, 37, 2350034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadim, A.M.; Abass, K.H. AP01038 Ag2Se Nanoparticles Synthesis by Co-Precipitation Method: Characterization and Antimicrobial Evaluation. Iraqi J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 21, 528–534. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, D.; Li, B.; Li, X.; AlTakrori, H.H.; Thirumalraj, B.; Rezeq, M.; Cantwell, W.; Zheng, L. Ultrahigh Seebeck Coefficient and Power Factor in Low-Temperature Fused Ag2Se Films via Superionic-Driven Plastic Deformation. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e08381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Sun, M.; Chen, C.; Lin, H.; Xu, C.; Kuang, H.; Xu, L. Enantiomeric NIR-II Emitting Rare-Earth-Doped Ag2Se Nanoparticles with Differentiated In Vivo Imaging Efficiencies. Angew. Chem. 2022, 134, e202210370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, H.; Ren, L.; Tu, B.; Wang, W.; Fu, Z. Theoretical study on composition-dependent properties of ZnO·nAl2O3 spinels. Part II: Mechanical and thermophysical. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 6455–6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Wang, H.; Ren, L.; Tu, B.; Wang, W.; Fu, Z. Theoretical study on composition-dependent properties of ZnO·nAl2O3 spinels. Part I: Optical and dielectric. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 104, 5099–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Panneer Selvam, S.; Cho, S. Lanthanide-Induced Local Structural and Optical Modulation in Low-Temperature Ag2Se. Crystals 2026, 16, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010004

Panneer Selvam S, Cho S. Lanthanide-Induced Local Structural and Optical Modulation in Low-Temperature Ag2Se. Crystals. 2026; 16(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010004

Chicago/Turabian StylePanneer Selvam, Sathish, and Sungbo Cho. 2026. "Lanthanide-Induced Local Structural and Optical Modulation in Low-Temperature Ag2Se" Crystals 16, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010004

APA StylePanneer Selvam, S., & Cho, S. (2026). Lanthanide-Induced Local Structural and Optical Modulation in Low-Temperature Ag2Se. Crystals, 16(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst16010004