Preparation of Temperature-Responsive Janus Nanosheets and Their Application in Emulsions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. XRD Analysis

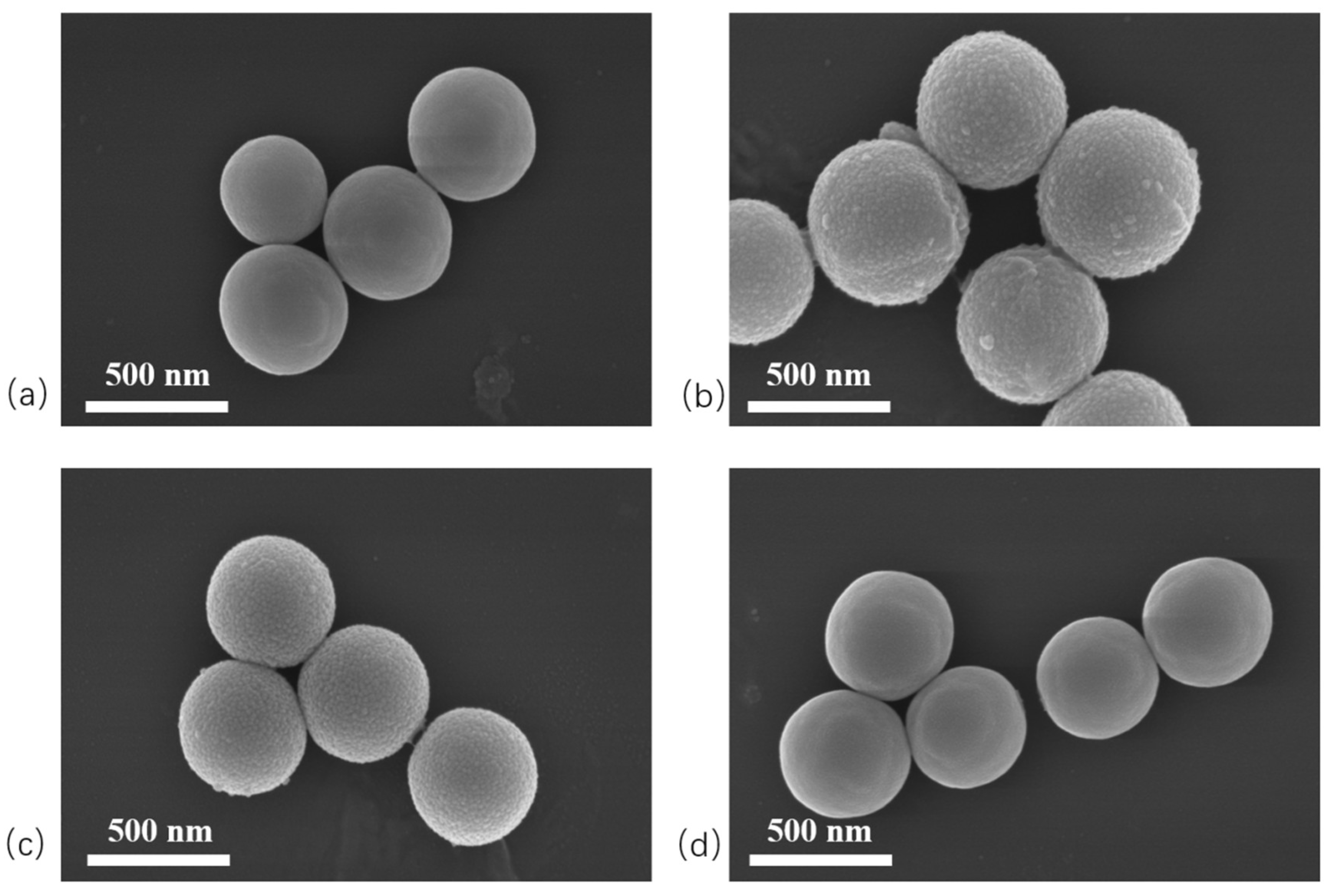

2.2. SEM Analysis

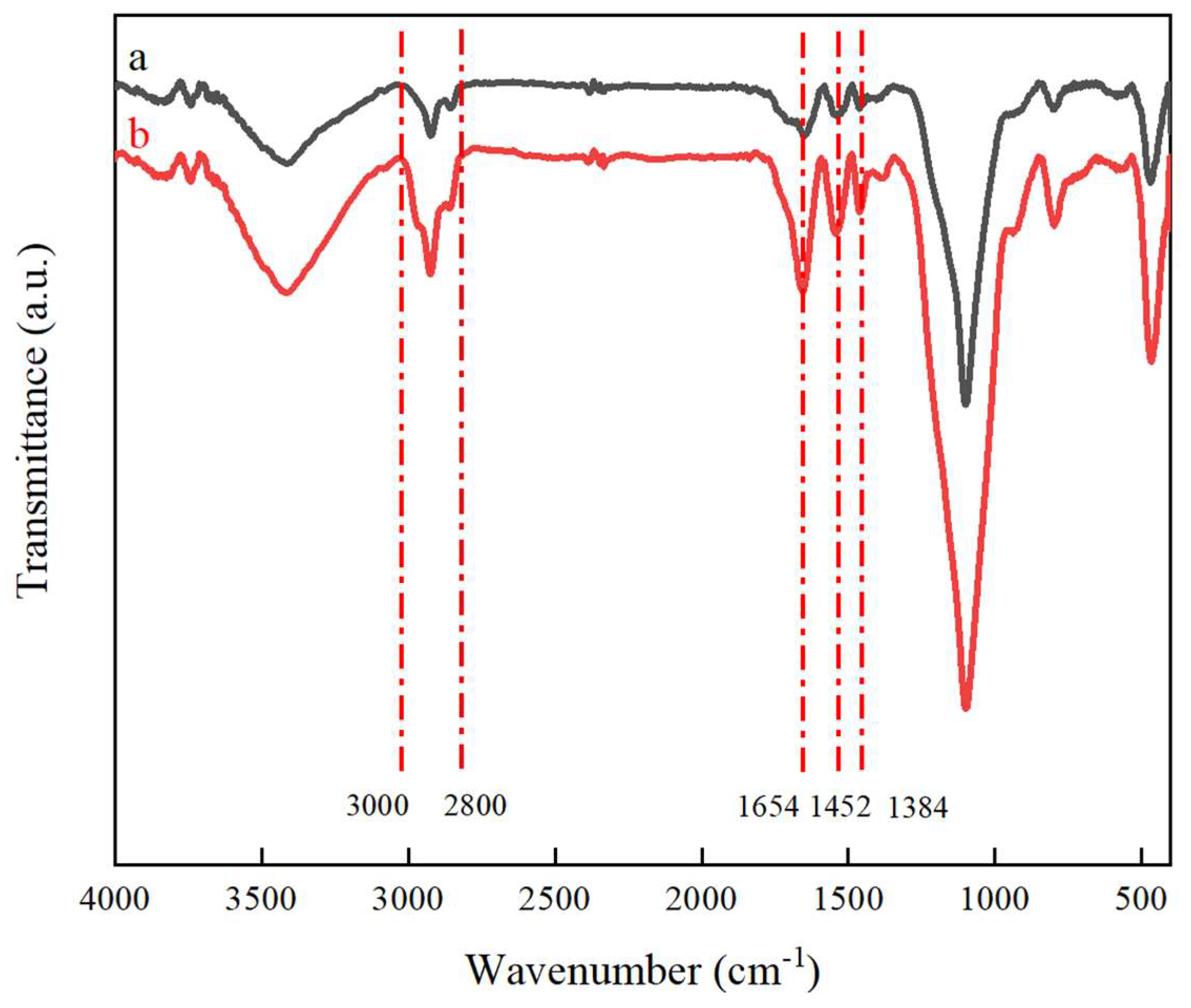

2.3. FTIR Analysis

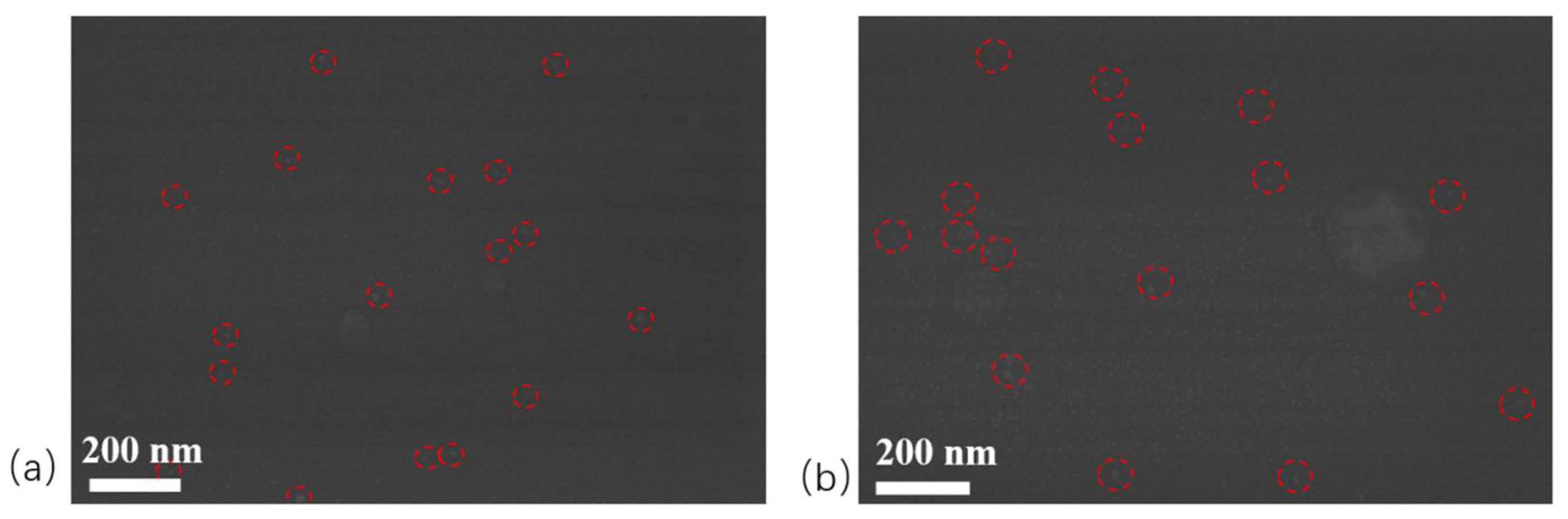

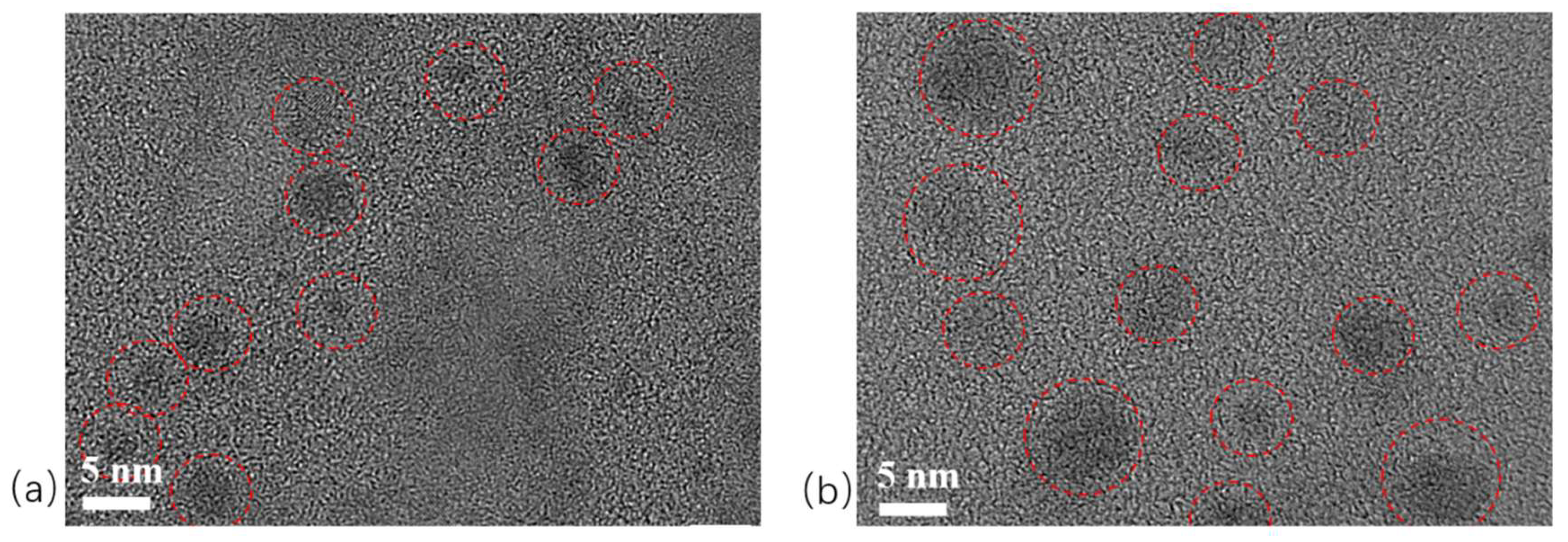

2.4. TEM Analysis

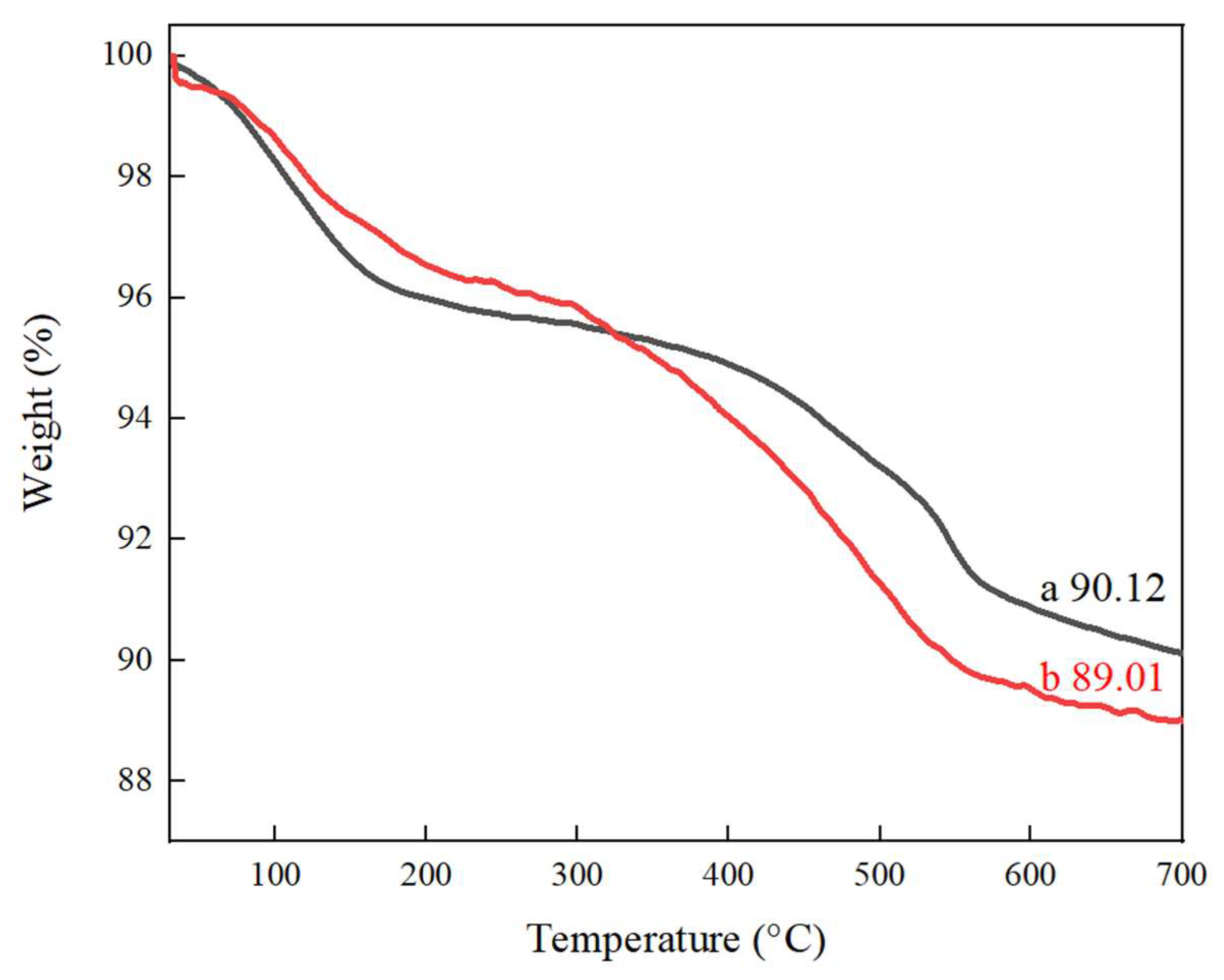

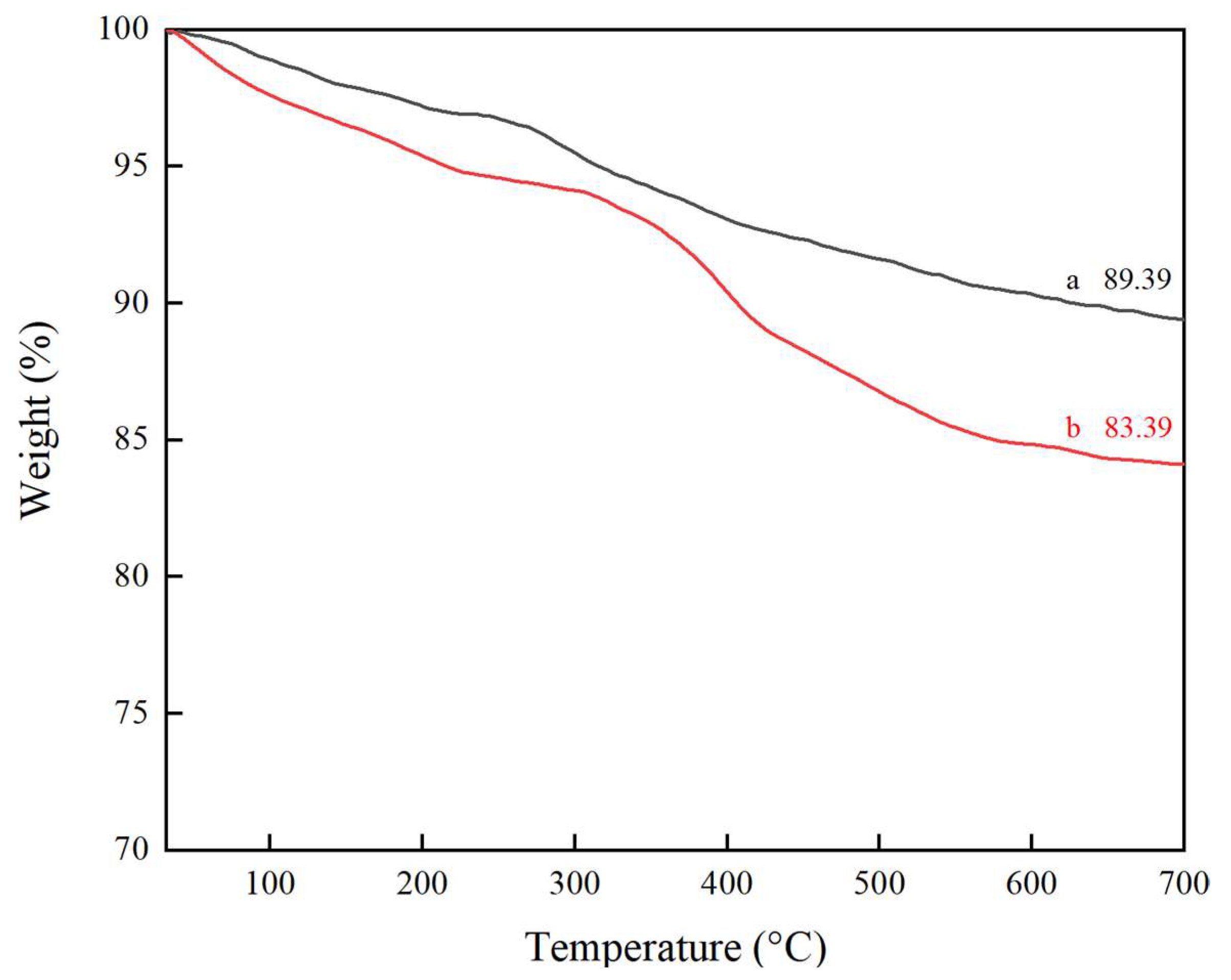

2.5. TG Analysis

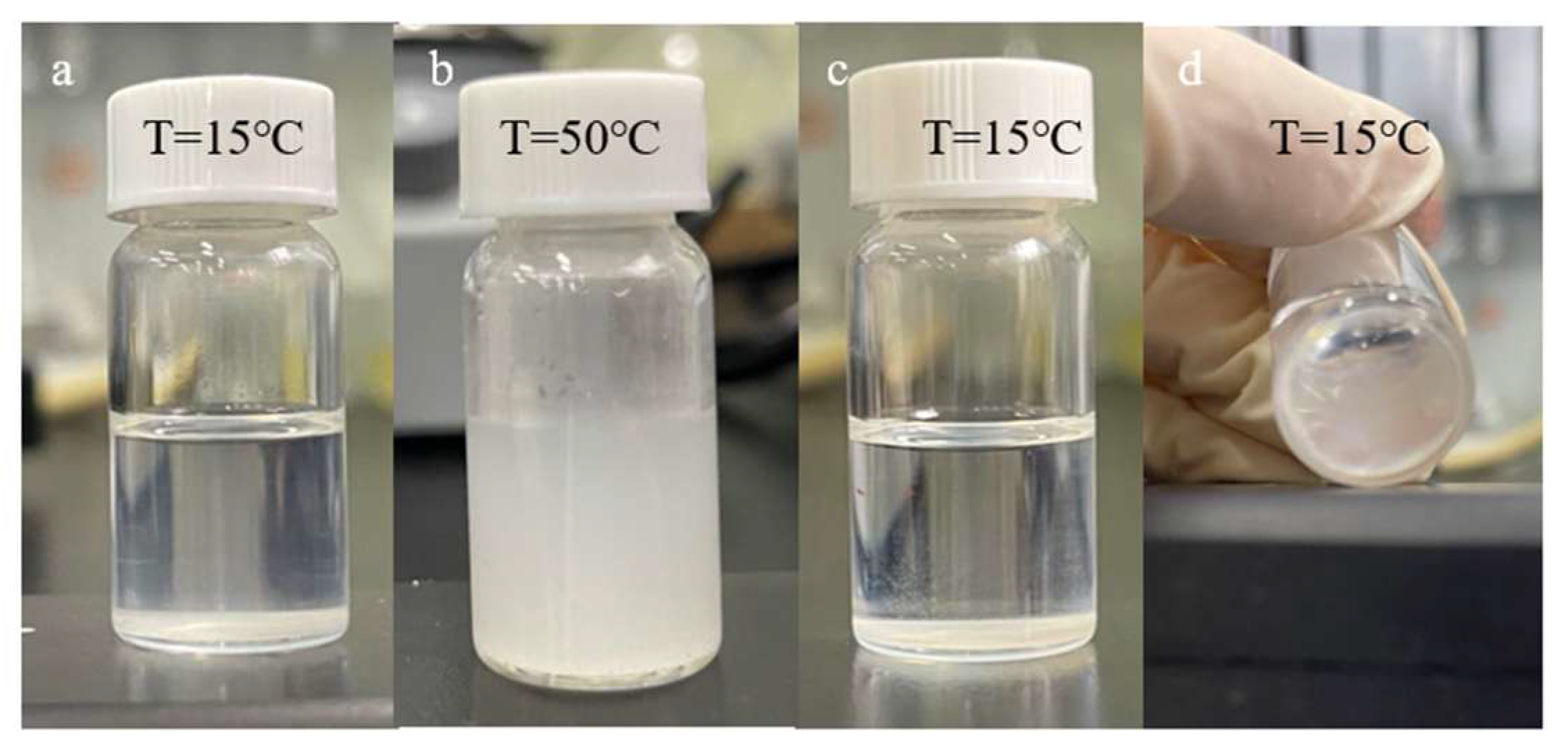

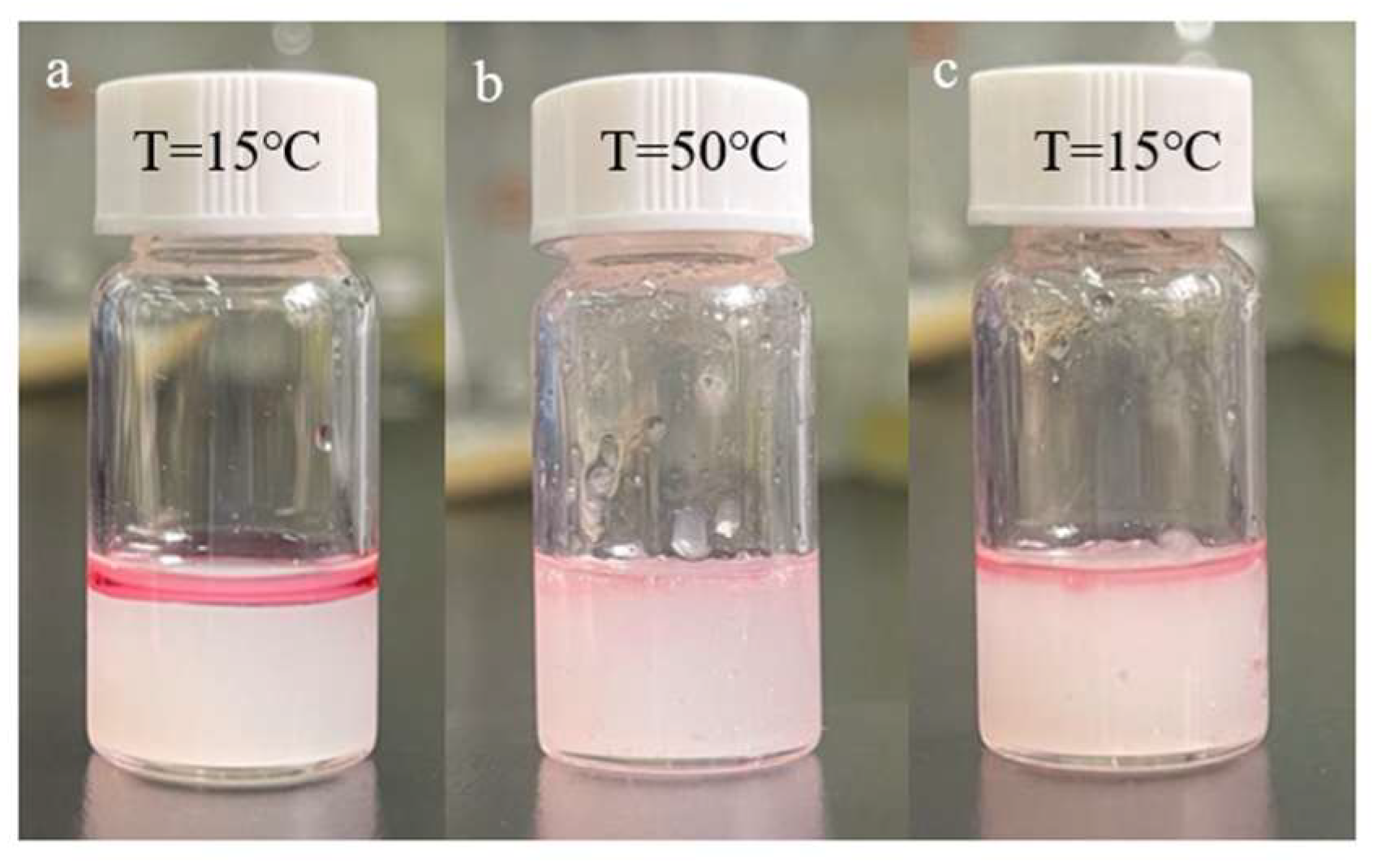

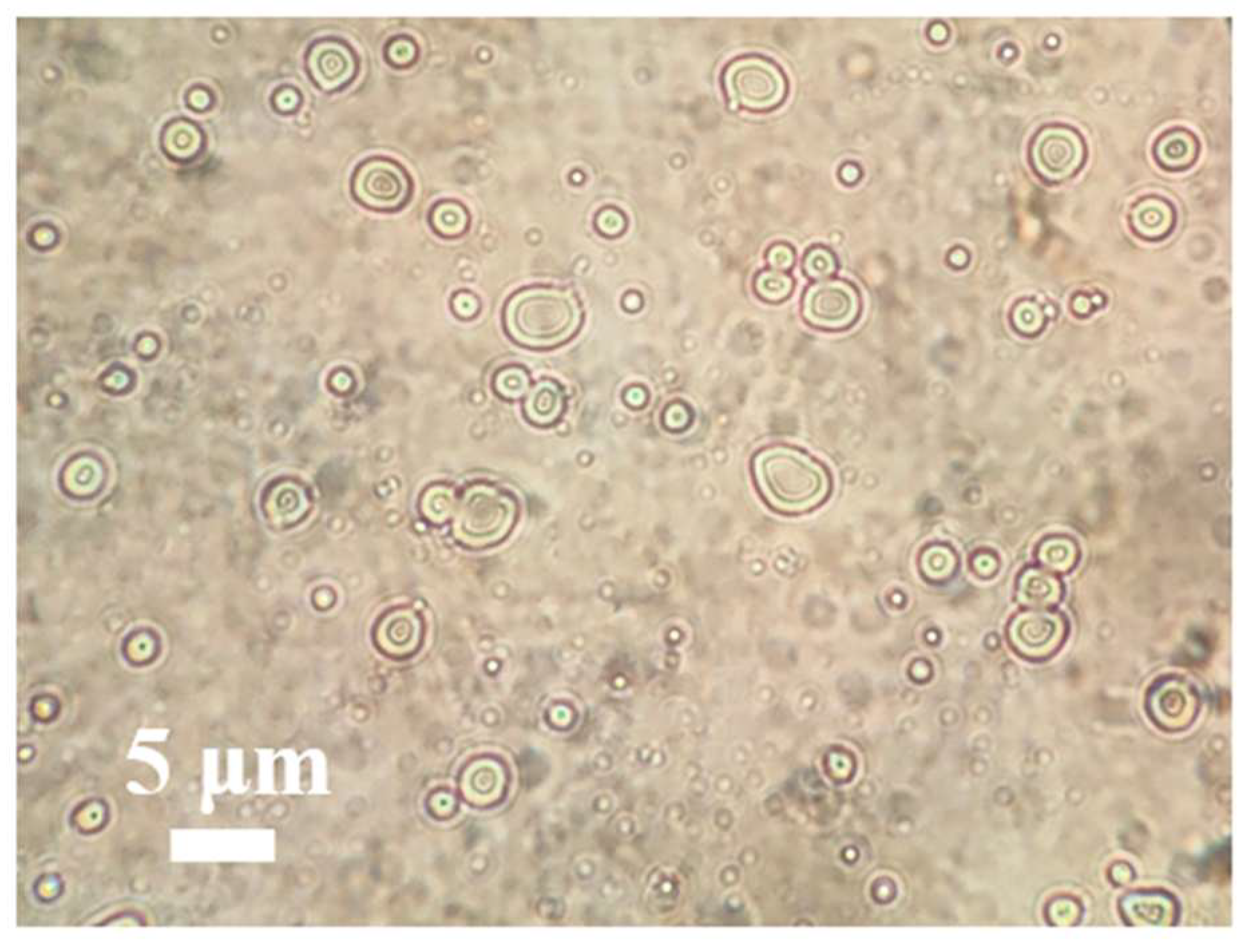

2.6. Emulsification Experiment

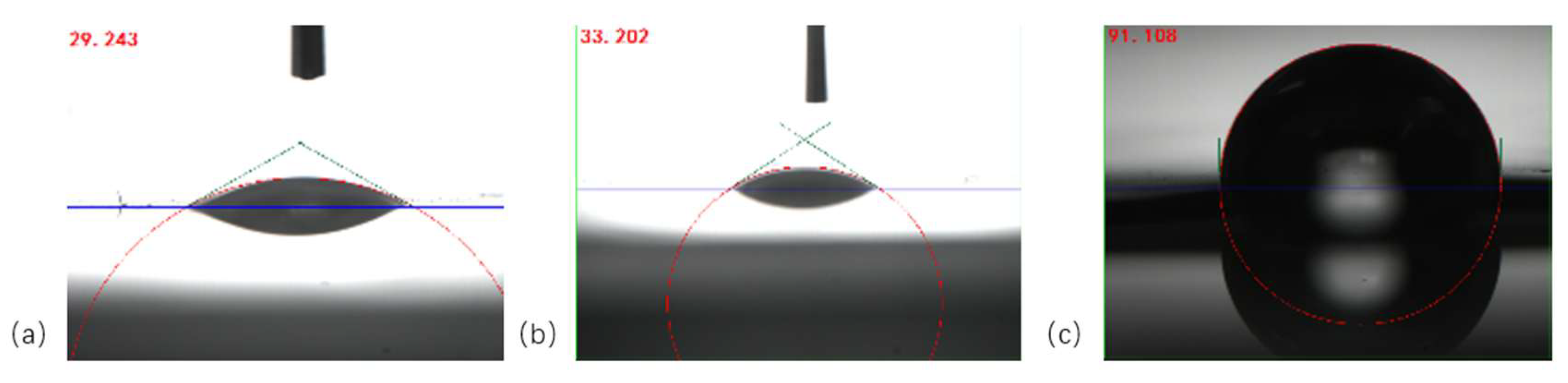

2.7. Contact Angle Test

3. Experiment

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.2. Sample Preparation

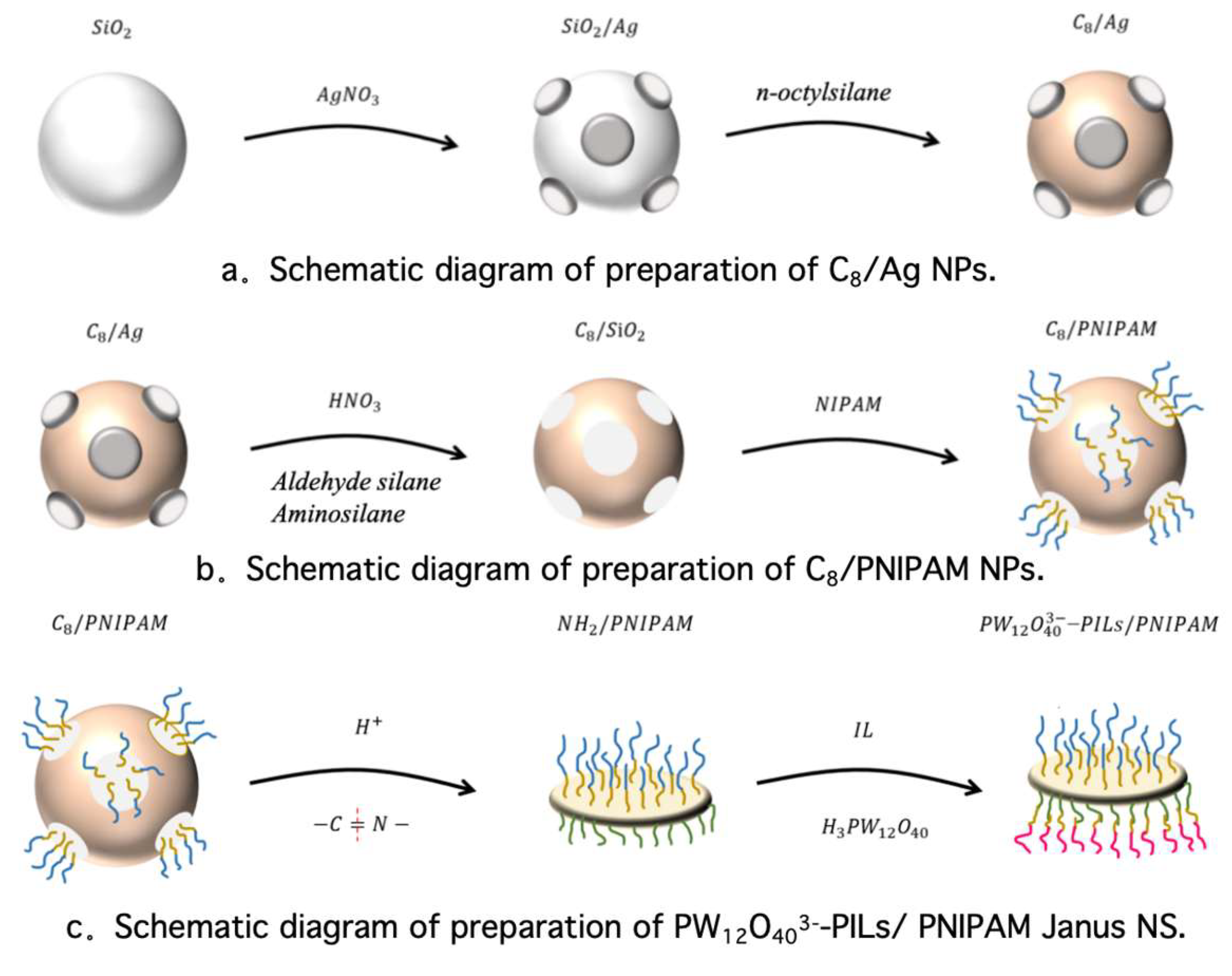

3.2.1. Preparation of C8/Ag NPs

3.2.2. Preparation of C8/PNIPAM NPs

3.2.3. Preparation of PW12O403−-PILs/PNIPAM Janus NS

3.3. Emulsification Tests

3.4. Material Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sondhi, S. Application of biosurfactant as an emulsifying agent. In Applications of Next Generation Biosurfactants in the Food Sector; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Reshmy, R.; Philip, E.; Madhavan, A.; Binod, P.; Awasthi, M.K.; Pandey, A.; Sindhu, R. Applications of biosurfactant as an antioxidant in foods. In Applications of Next Generation Biosurfactants in the Food Sector; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 391–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran, N.; Kang, D.; Han, J.; Gurunathan, B. Process optimization, economic and environmental analysis of biodiesel production from food waste using a citrus fruit peel biochar catalyst. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soodesh, C.Y.; Seriyala, A.K.; Navjot; Chattopadhyay, P.; Rozhkova, N.; Michalkiewicz, B.; Chatterjee, S.; Roy, B. Carbonaceous catalysts (biochar and activated carbon) from agricultural residues and their application in production of biodiesel: A review. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2024, 203, 759–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulredha, M.M.; Hussain, S.A.; Abdullah, L.C.; Hong, T.L. Water-in-oil emulsion stability and demulsification via surface-active compounds: A review. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 209, 109848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Chen, H.; He, L.; Ni, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Z.; Tian, Y. Comprehensive review of stabilising factors, demulsification methods, and chemical demulsifiers of oil-water emulsions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 358, 130206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borówko, M.; Staszewski, T.; Tomasik, J. Janus Ligand-Tethered Nanoparticles at Liquid–Liquid Interfaces. J. Phys. Chem. B 2023, 127, 5150–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.T.; Gates, I.D.; Natale, G. Dynamics of Brownian Janus rods at a liquid–liquid interface. Phys. Fluids 2022, 34, 012117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zeng, M.; Cheng, Q.; Huang, C. Recent progress toward physical stimuli-responsive emulsions. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2022, 43, e2200193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brugger, B.; Richtering, W. Magnetic, thermosensitive microgels as stimuli-responsive emulsifiers allowing for remote control of separability and stability of oil in water-emulsions. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 2973–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Choi, J.; Li, H.; Jia, Y.; Huang, R.; Stebe, K.J.; Lee, D. Janus particles with varying configurations for emulsion stabilization. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 20961–20968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yang, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Liang, F. Temperature-Responsive Janus Colloidal Emulsifier for the Removal of Organic Pollutants in One Pot. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 37125–37134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Yang, Z.; Lin, M.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z. Preparation of Janus nanosheets via reusable cross-linked polymer microspheres template. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 371, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtarianfar, S.F.; Khayatian, A.; Kashi, M.A. Effect of annealing of ZnO/Ag double seed layer on the electrical properties of ZnO/Ag/ZnO heterostructure nanorods. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, H.; Ye, B. Thermal diffusion and epitaxial growth of Ag in Ag/SiO2/Si probed by XRD, depth-resolved XPS, and slow positron beam. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 496, 143527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzi, L.; Hesemann, P.; Laassiri, S.; EL Hankari, S. Alternative approaches for the synthesis of nano silica particles and their hybrid composites: Synthesis, properties, and applications. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 11575–11614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ragib, A.; Chakma, R.; Wang, J.; Alanazi, Y.M.; El-Harbawi, M.; Arish, G.A.; Islam, T.; Siddique, M.A.B.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; Kormoker, T. The past to the current advances in the synthesis and applications of silica nanoparticles. Nano-Struct. Nano-Objects 2024, 40, 101395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Li, M.; Fu, S. Photoinduced Metal-Free Atom Transfer Radical Polymerization for the Modification of Cellulose with Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) to Create Thermo-Responsive Injectable Hydrogels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Younis, M.W.; Maqbool, M.; Goh, H.H.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Amjad, M.; Othman, M.H.D. Revolutionizing photocatalysis: Synthesis of innovative poly (N-tertiary-butylacrylamide)-graft-hydroxypropyl cellulose polymers for thermo-responsive applications via metal-free organic photoredox catalysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 288, 138775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawand, M.A. Silica Core@ Shell Nanoparticles for Biomedical Applications: A Study in Pharmaceutical Sciences; Åbo Akademi University: Turku, Finland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Djayanti, K.; Maharjan, P.; Cho, K.H.; Jeong, S.; Kim, M.S.; Shin, M.C.; Min, K.A. Mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a potential nanoplatform: Therapeutic applications and considerations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 6349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Li, S.; Shi, R.; Liu, H. Multifunctional mesoporous silica nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Shen, D.; Yin, S.; Wang, H.; Huo, P.; Yan, Y. Thermo-responsive functionalized PNIPAM@ Ag/Ag3PO4/CN-heterostructure photocatalyst with switchable photocatalytic activity. Chin. J. Catal. 2020, 41, 1573–1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Cao, Y.; Fan, T.; Zhang, M.; Yao, J.; Li, P.; Chen, S.; Liu, X. In situ synthesis of Ag3PO4/C3N5 Z-scheme heterojunctions with enhanced visible-light-responsive photocatalytic performance for antibiotics removal. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 754, 141926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizazu, G. Investigation of the effect of molecular weight, density, and initiator structure size on the repulsive force between a PNIPAM polymer brush and protein. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2022, 2022, 9741080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-F.; Luo, M.-B. Height-Switching of Active Polymers in Binary Polymer Brushes. Macromolecules 2025, 58, 5421–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Cao, T.; Du, J.; Qi, X.; Yan, H.; Xu, X. The Bi-Modified (BiO) 2CO3/TiO2 Heterojunction Enhances the Photocatalytic Degradation of Antibiotics. Catalysts 2025, 15, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarova, G.A.; Kozhunova, E.Y.; Gumerov, R.A.; Potemkin, I.I.; Nasimova, I.R. Effect of Polymer Network Architecture on Adsorption Kinetics at Liquid–Liquid Interfaces: A Comparison Between Poly (NIPAM-co-AA) Copolymer Microgels and Interpenetrating Network Microgels. Gels 2025, 11, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buritica, S.; Gutteriez, J.; Lapeyre, V.; Garrigue, P.; Brisson, A.; Tran, S.; Laurichesse, E.; Ly, I.; Schmitt, V.; Diat, O.; et al. Inter cross-linking microgels by superchaotropic nanoions at interface: Controlled stabilization of emulsions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 699, 138257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, A.; Agnihotri, P.; Bochenek, S.; Richtering, W. Adsorption dynamics of thermoresponsive microgels with incorporated short oligo (ethylene glycol) chains at the oil–water interface. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 6127–6139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, M.; Ofem, M.I.; Anwar, A.S.; Salisu, A.G. Thermo gravimetric analysis (TGA) of PA6/G and PA6/GNP composites using two processing streams. J. King Saud Univ.-Eng. Sci. 2020, 34, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, K.; Bhaumik, S.; Pramanik, S. Effect of graphite on tribological and mechanical properties of PA6/5GF composites. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 3341–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.; Gao, Y.; Xia, W.; Qi, X. Preparation of Bi@Ho3+:TiO2/Composite Fiber Photocatalytic Materials and Hydrogen Production via Visible Light Decomposition of Water. Catalysts 2024, 14, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Qi, X.; Yan, H. Development and Assessment of a Water-Based Drilling Fluid Tackifier with Salt and High-Temperature Resistance. Crystals 2025, 15, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barros, A.H.; Magalhães, R.F.; Murakami, L.M.S.; Diniz, M.F.; Sanches, N.B.; de Carvalho, T.A.; Dutra, J.C.N.; Dutra, R.d.C.L. Determination of elastomer content in NR/SBR/BR blends. Polímeros 2025, 35, e20250023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camadanli, S.; Hisir, A.; Dural, S. Synthesis and performance of moisture curable solvent free silane terminated polyurethanes for coating and sealant applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, Q.-C.; Li, J.; Wang, C.-Y.; Ren, Q. Synthesis of hydroxy silane coupling agent and the silane-terminated polyurethane chain-extended by butanediol. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2022, 19, 1457–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Qi, X.; Yan, H.; Xue, D.; Xu, X.; He, S.; Xia, W.; Zhang, J. Preparation of Temperature-Responsive Janus Nanosheets and Their Application in Emulsions. Crystals 2025, 15, 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100891

Gao Y, Qi X, Yan H, Xue D, Xu X, He S, Xia W, Zhang J. Preparation of Temperature-Responsive Janus Nanosheets and Their Application in Emulsions. Crystals. 2025; 15(10):891. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100891

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yue, Xuan Qi, Hao Yan, Dan Xue, Xuefeng Xu, Suixin He, Wei Xia, and Junfeng Zhang. 2025. "Preparation of Temperature-Responsive Janus Nanosheets and Their Application in Emulsions" Crystals 15, no. 10: 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100891

APA StyleGao, Y., Qi, X., Yan, H., Xue, D., Xu, X., He, S., Xia, W., & Zhang, J. (2025). Preparation of Temperature-Responsive Janus Nanosheets and Their Application in Emulsions. Crystals, 15(10), 891. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst15100891