Recent Progress in Electric Furnace Titanium Slag Processing and Utilization: A Review

Abstract

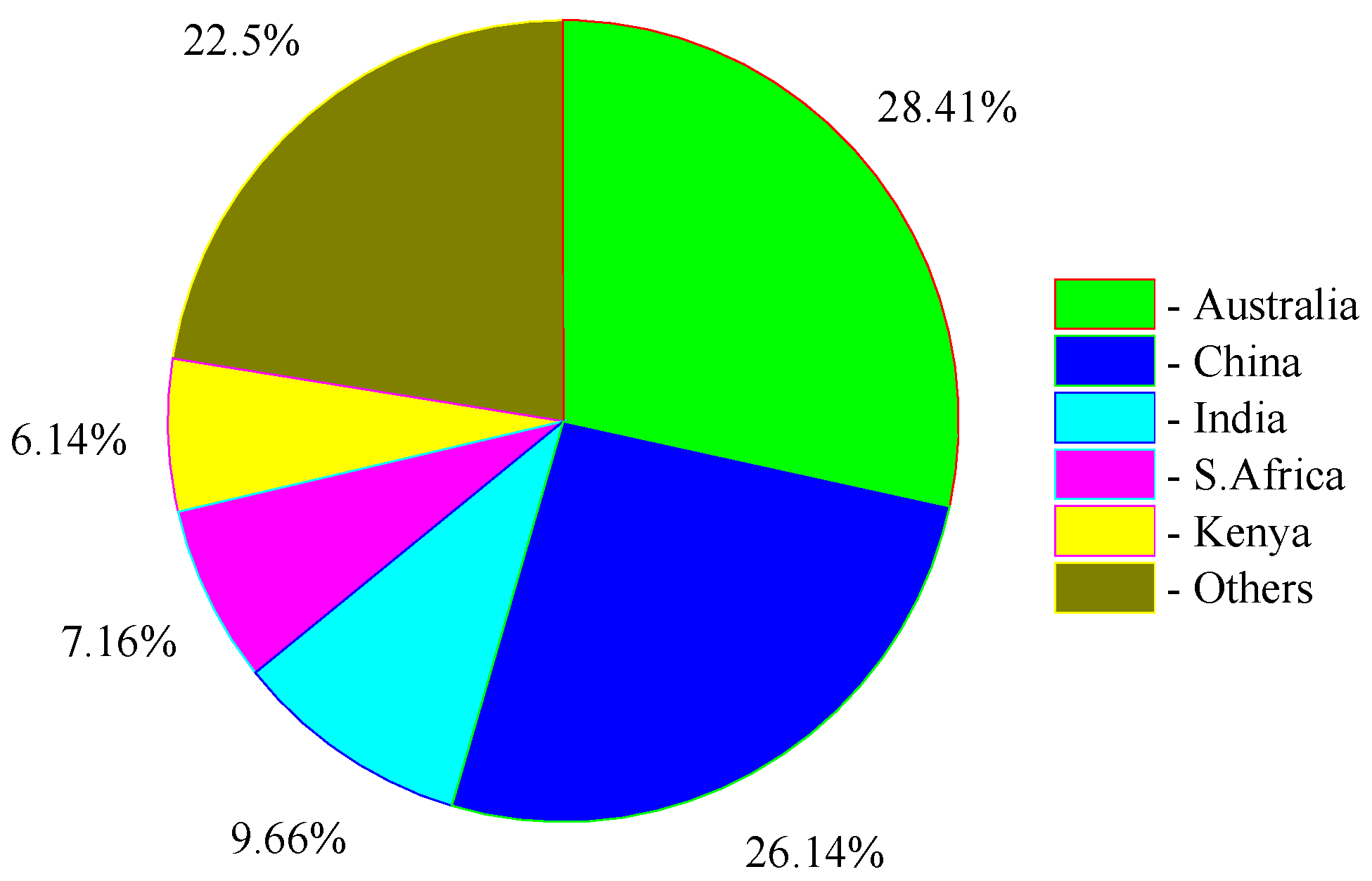

:1. Introduction

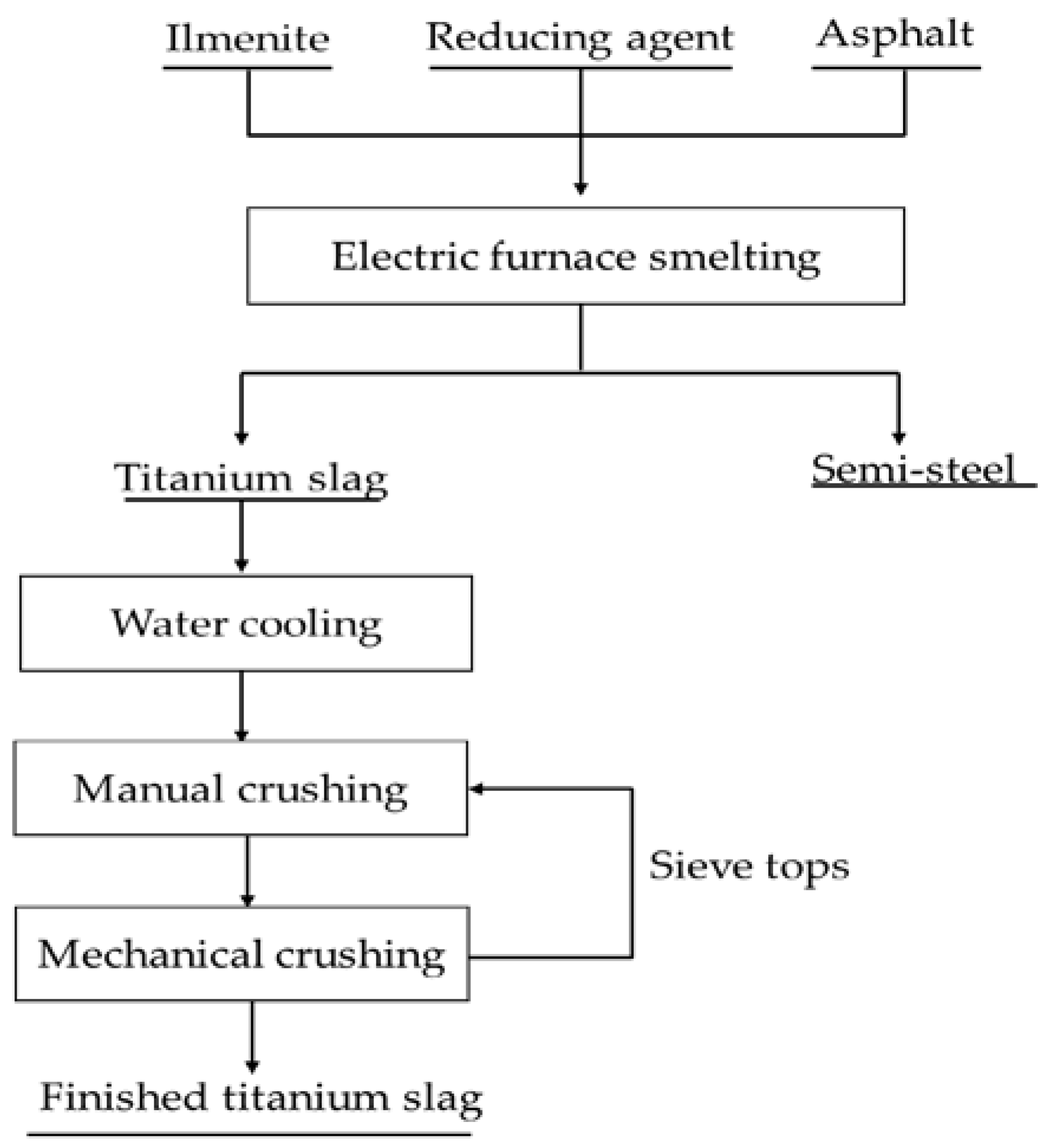

2. Titanium Slag Production and Characteristics

3. The progress of Titanium Slag Processing and Utilization

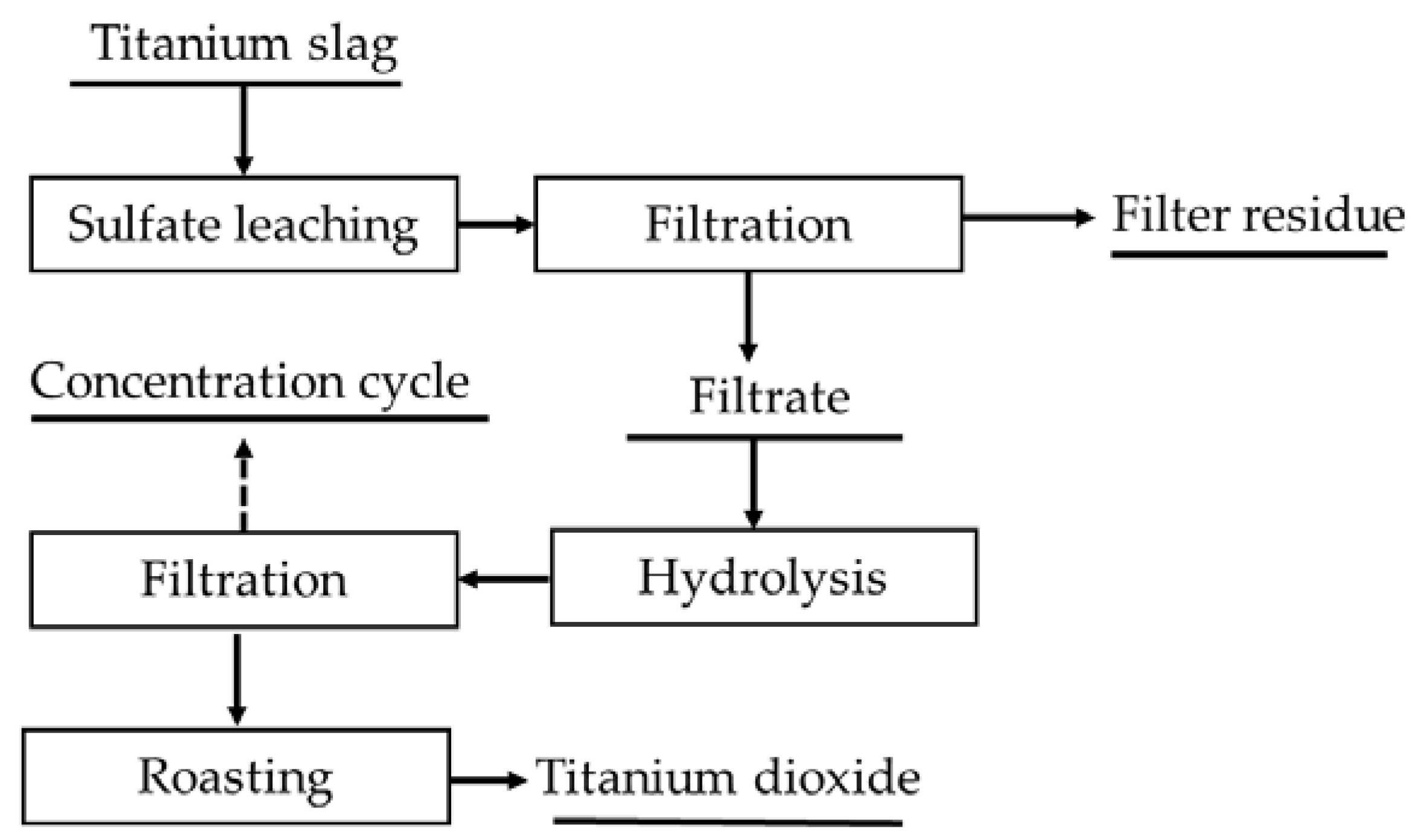

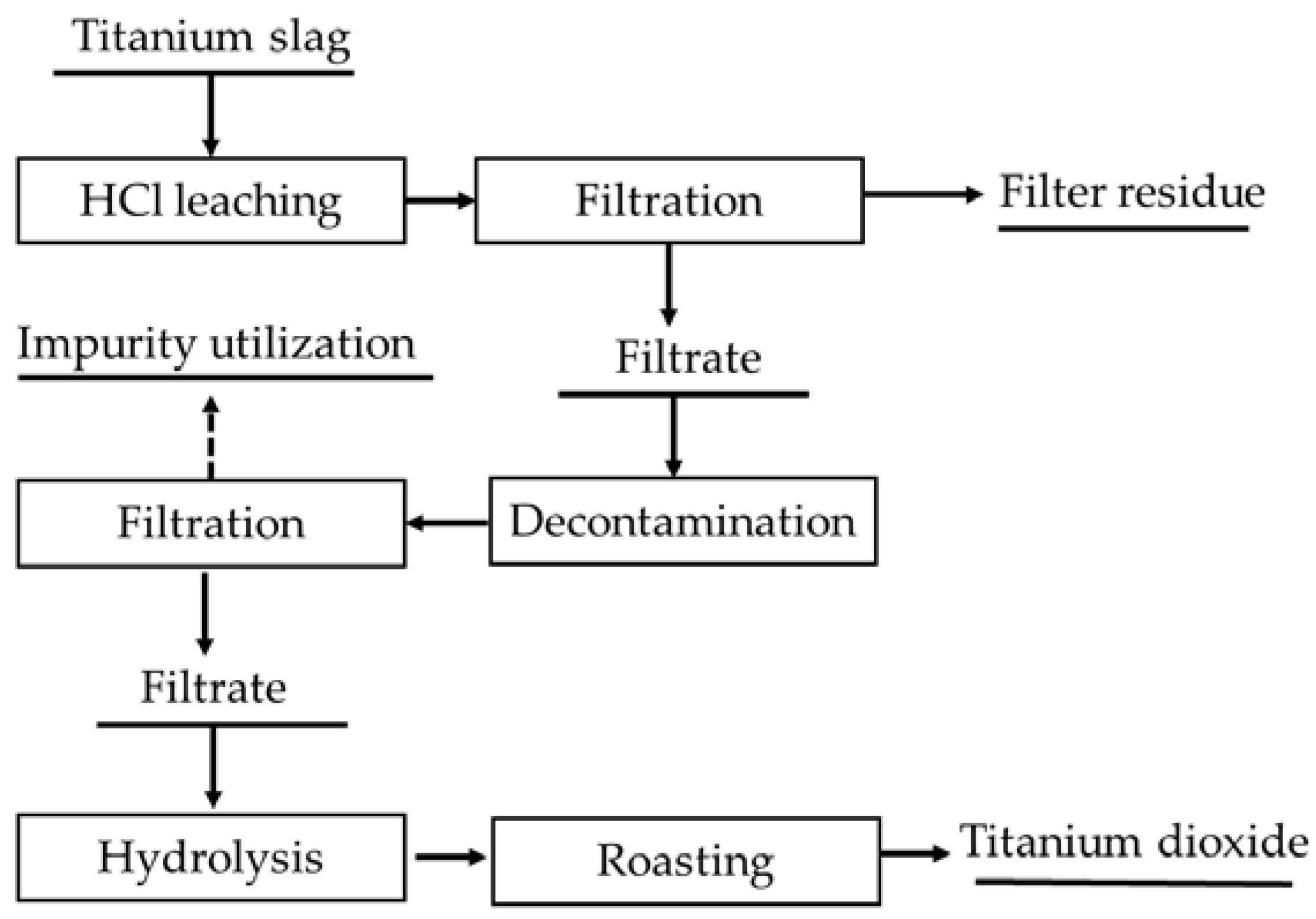

3.1. Preparation of Titanium Dioxide

3.1.1. H2SO4 Leaching Process

3.1.2. HCl Leaching Process

FeCl2 + 5TiOCl2 + 2AlCl3 + 5H2O + 9H2

2TiOCl2 + 2H2SiO3 + 9H2

3.1.3. Fluoride Leaching Process

3.1.4. Ammonia Decomposition–Leaching Process

3.2. Preparation of High-Quality Titanium-Rich Materials

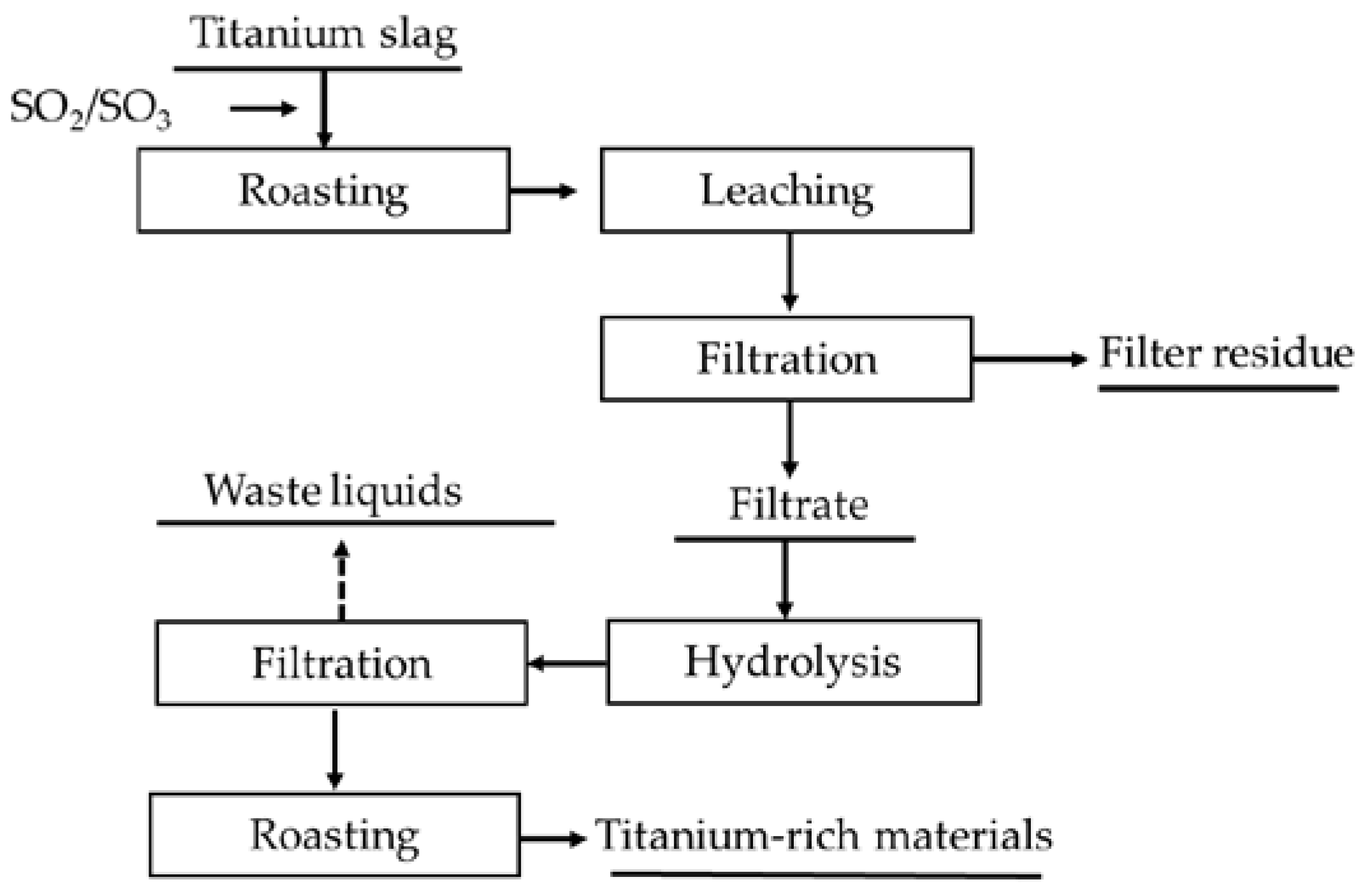

3.2.1. Sulfur Roasting–Leaching Process

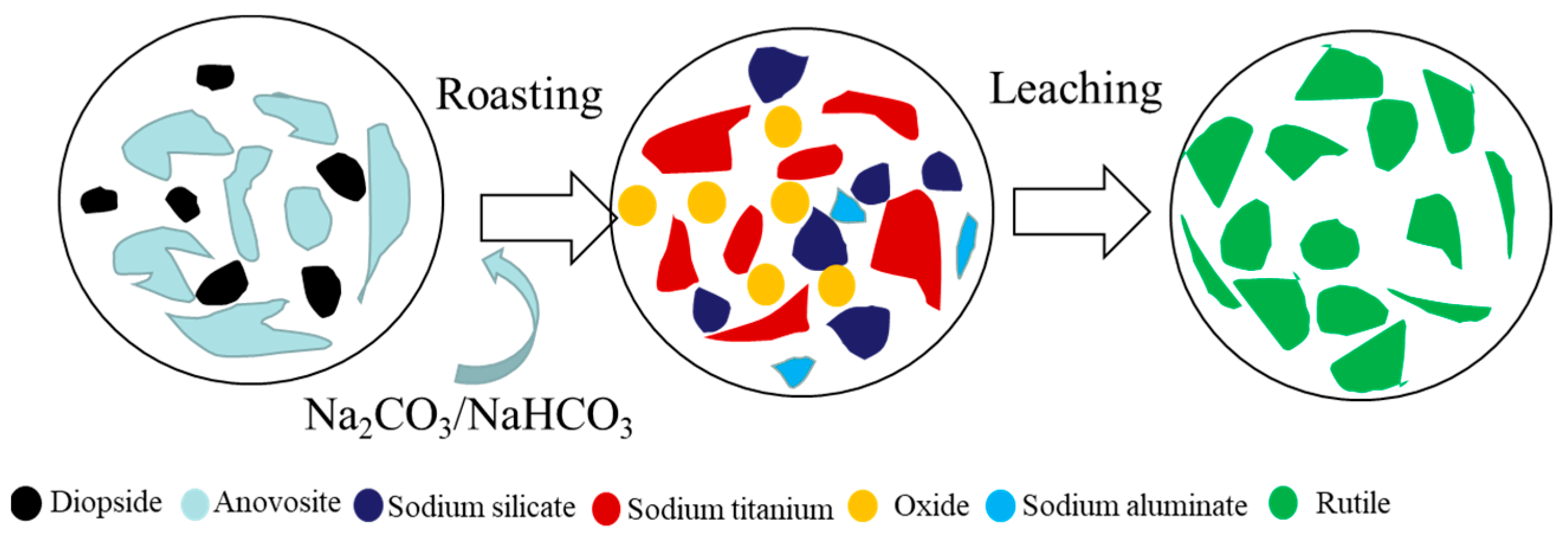

3.2.2. Alkaline Roasting–Leaching Process

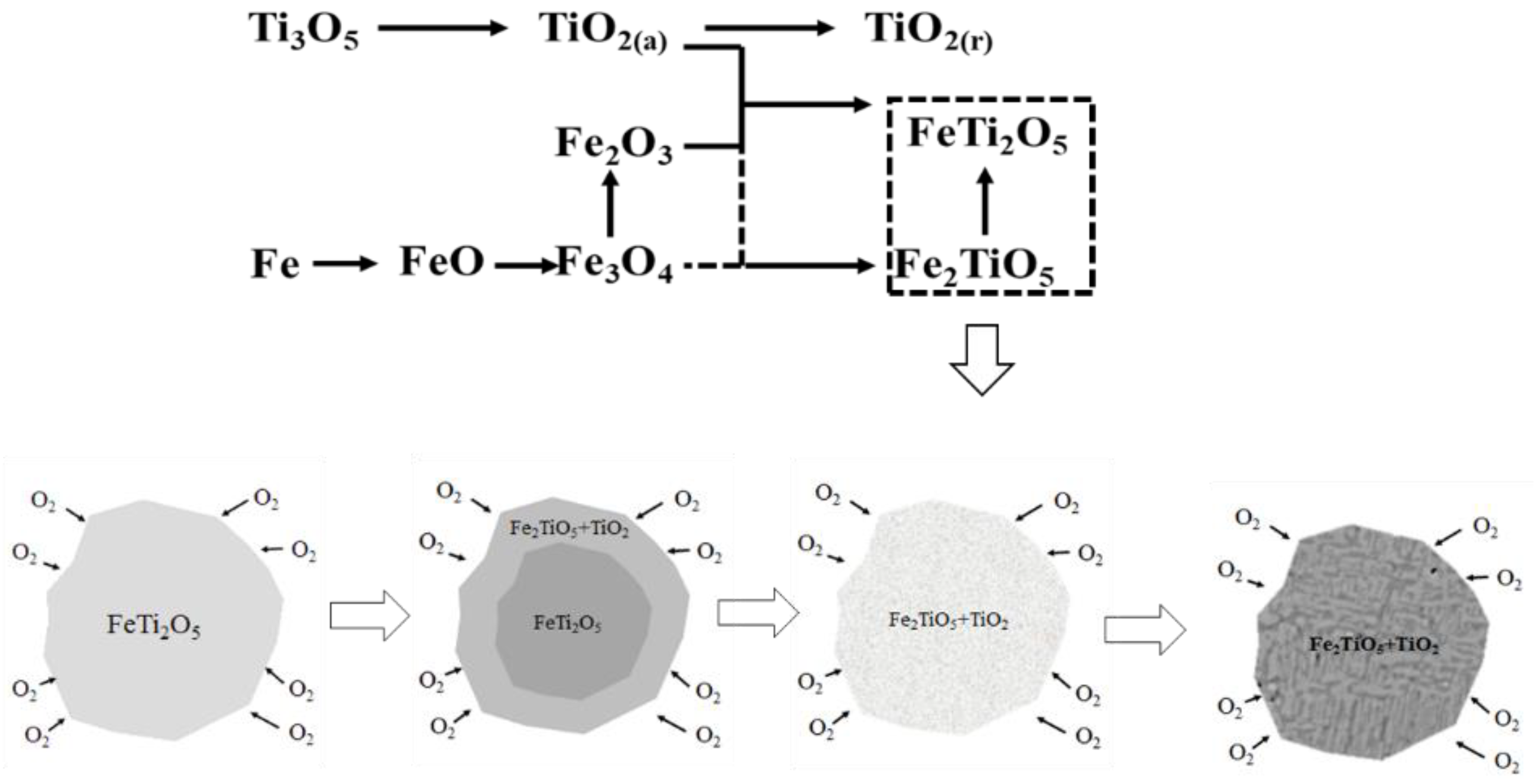

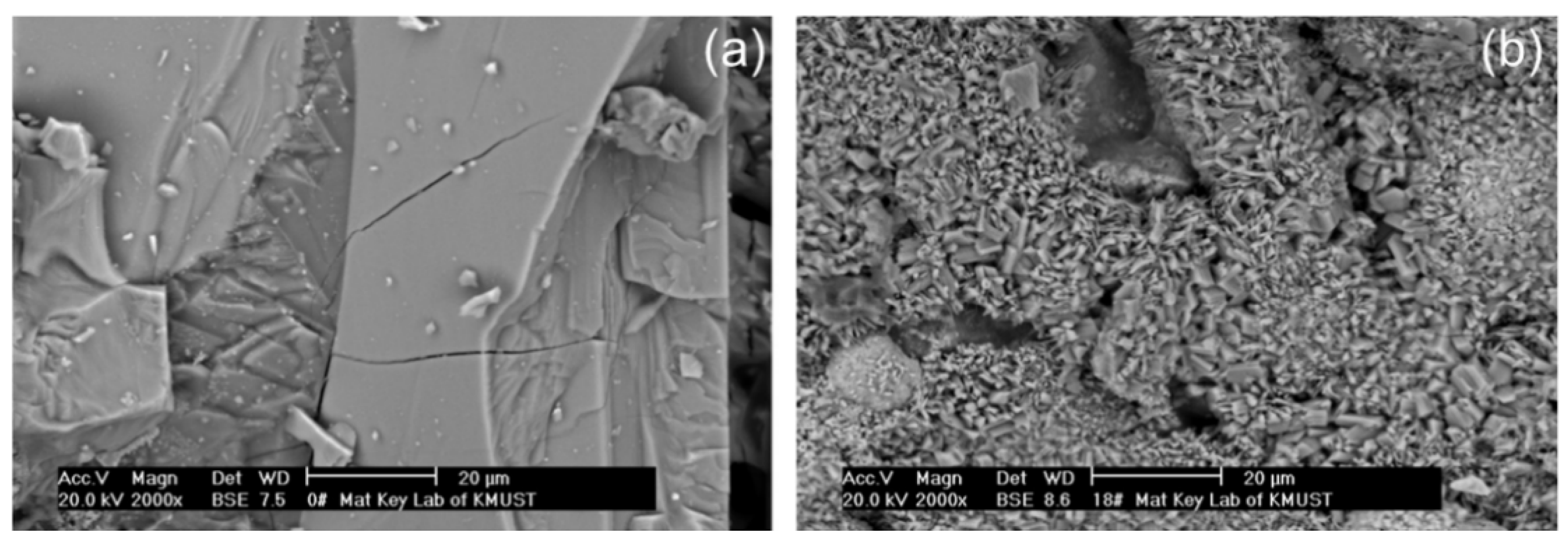

3.2.3. Oxide Roasting–Leaching Process

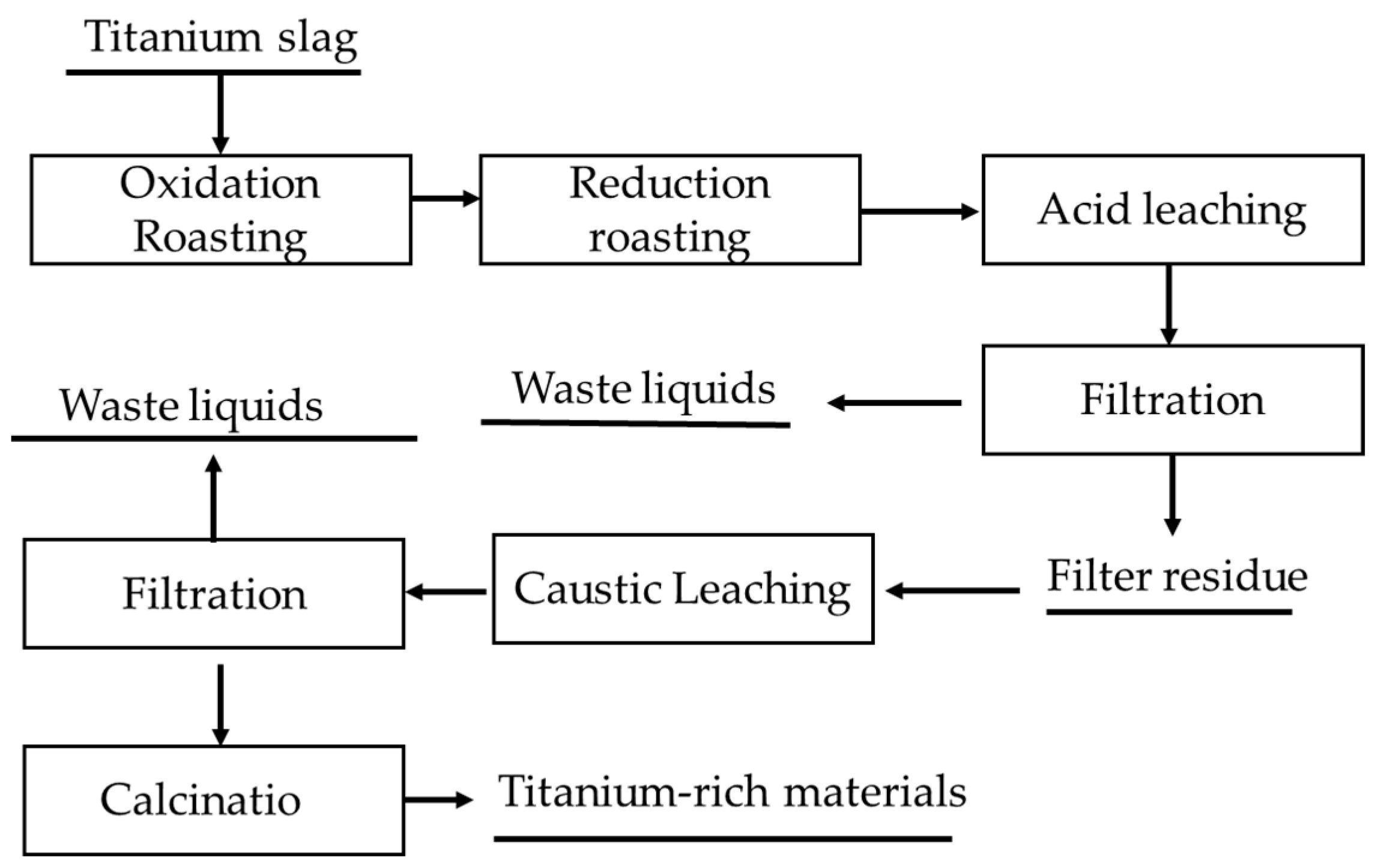

3.2.4. Oxidation and Reduction Roasting–Leaching Process

3.2.5. Phosphorylation Roasting–Leaching Process

3.3. The Effect of Impurities on the Utilisation of Titanium Slag

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Attar, H.; Ehtemam-Haghighi, S.; Kent, D.; Wu, X.; Dargusch, M.S. Comparative study of commercially pure titanium produced by laser engineered net shaping, selective laser melting and casting processes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 705, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, Z.H.; Jiao, H.D.; Mi, Z.S.; Wang, M.Y.; Jiao, S.Q. Selective extraction of titanium from Ti-bearing slag via the enhanced depolarization effect of liquid copper cathode. J. Energy Chem. 2020, 42, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, C.; Peng, J.H.; Chen, J. Optimizing conditions for wet grinding of synthetic rutile using response surface methodology. Min. Met. Explor. 2011, 28, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middlemas, S.; Fang, Z.; Peng, F. A new method for production of titanium dioxide pigment. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 131–132, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://prd-wret.3-us-west2.amazonaws.com/assets/palladium/production/atoms/files/mcs-2020timin.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Zhang, X.; Du, Z.; Zhu, Q.S.; Li, J.; Xie, Z.H. Enhanced reduction of ilmenite ore by pre-oxidation in the view of pore formation. Powder Technol. 2022, 405, 117539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.H.; Li, J.H.; Song, N.; Xiao, L.; Yang, S.L. Study of technological mineralogy on electrotitanum slag in panzhihua area. J. Mineral. Petrol. 2016, 36, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- He, A.X.; Chen, G.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.H.; Srinivasakannan, C.; Ruan, R.S. A novel method of synthesis and investigation on transformation of synthetic rutile powders from Panzhihua sulfate titanium slag using microwave heating. Powder Technol. 2018, 323, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.J.; Meng, F.C.; Chu, J.L.; Qi, T.; Fang, F.Q.; Liu, Y.H. Preparation of rutile titanium dioxide pigment from low-grade titanium slag pretreated by the NaOH molten salt method. Dye. Pigment. 2016, 125, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, L.; Zhu, F.X.; Deng, P.; Zhang, D.F.; Jia, Y.Q.; Li, K.H.; Kong, L.X.; Liu, D.C. Behavior of Magnesium Impurity During Carbochlorination of Magnesium-bearing Titanium Slag in Chloride Media. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 13, 204–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.G.; Jiang, T.; Guo, Y.F.; Chen, J.; Fan, X.H. Upgrading a Ti-slag by a roast-leach process. Hydrometallurgy 2012, 113–114, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borowiec, K.; Grau, A.E.; Gueguin, M.; Turgeon, J.F. Method to Upgrade Titania Slag and Resulting Product. WO1997019199 A1, 3 November 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, K.J.; Xi, G.; Yao, J.; Xi, X. Status quo of Manufacturing Techniques of Titanium Slag in the world. World Nonferrous Met. 2006, 12, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Toromanoff, I.; Habashi, F. The composition of a titanium slag from sorel. J. Less Common. Met. 1984, 97, 317–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.J.; Xi, G.; Yao, J.; Xi, X. Titanium Slag State of Technology in the World. Rare Met. Lett. 2006, 25, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kasimuthumaniyan, S.; Singh, S.K.; Jayasankar, K.; Mohanta, K.; Mandal, A. An alternate approach to synthesize TiC powder through thermal plasma processing of titania rich slag. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 18004–18011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Guo, C.; Peng, J.H.; Srinivasakannan, C.; Ruan, R.S. Study of the oxygen reduction of low valent titanium in high titanium slag by microwave rapid heating. Powder Technol. 2017, 315, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Lei, T.; Mi, J.R.; Zhou, L. Studying on Phase Compositions and Removal Impurities Mechanism of Electro-Titanium Slag. Yunnan Metall. 2006, 35, 35–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grass, V.; Istomin, P.; Nazarova, L. X-ray diffraction refinement of the crystal structure of anosovite prepared from leucoxene. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2009, 44, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.X.; Fu, W.Z. Mineralogical Characteristics of Anosovite Solid Solution. Multipurp. Util. Miner. Resour. 2012, 3, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.N.; Liang, B.; Lü, L.; Yuan, S.J.; Zheng, L.J.; Wang, X.M.; Li, C. Beneficiation of titania by sulfuric acid pressure leaching of Panzhihua ilmenite. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 150, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Jiang, L.Y.; Song, Y. Titanium white sulfuric acid concentration by direct contact membrane distillation. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 285, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, M.; Pu, J.; He, L.; Ruan, R.; Omran, M.; Peng, J.; Chen, G.; Guo, C. Synthesis of rutile TiO2 powder by microwave-enhanced roasting followed by hydrochloric acid leaching. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 1140–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perovskiy, I.A.; Burtsev, I.N.; Ponaryadov, A.V.; Smorokov, A.A. Ammonium fluoride roasting and water leaching of leucoxene concentrates to produce a high grade titanium dioxide resource (of the Yaregskoye deposit, Timan, Russia). Hydrometallurgy 2022, 210, 105858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayl, A.A.; Ismail, I.M.; Aly, H.F. Ammonium hydroxide decomposition of ilmenite slag. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 98, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, F.B.; Luo, D.M.; Zhang, Z.; Liang, B.; Yuan, X.Z.; Fu, L. Study on the behavior of sulfur in hydrolysis process of titanyl sulfate solution. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 670, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, K.K.; Alex, T.C.; Mishra, D.; Agrawal, A. An overview on the production of pigment grade titania from titania-rich slag. Waste Manag. Res. 2006, 24, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.L.; Wen, S.M.; Feng, Q.C.; Liu, D.; Zhou, Y.W. Mechanism and kinetics study of sulfuric acid leaching of titanium from titanium-bearing electric furnace slag. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1750–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Li, C.; Liang, B. A two-step sulfuric acid leaching process of ti-bearing blast furnace slag. Chin. J. Process Eng. 2006, 6, 413–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qu, X.M.; Guo, Y.F.; Zheng, F.Q.; Jiang, T.; Qiu, G.Z. Performance of Sulfuric Acid Leaching of Titanium from Titanium-Bearing Electric Furnace Slag. J. Mater. Sci. Res. 2016, 5, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, J.B.; Liao, H.J.; Ye, E.D.; Zhang, X.Y. Study on Preparation of High Quality Titanium-rich Materials by Hydrochloric Acid Leaching of Panzhihua Titanium Slag. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 2016, 37, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Samal, S. The dissolution of iron in the hydrochloric acid leach of titania slag obtained from plasma melt separation of metalized ilmenite. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011, 89, 2190–2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samal, S. Preparation of synthetic rutile from pre-treated ilmenite/Ti-rich slag with phenol and resorcinol leaching solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 137, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Li, C.; Liang, B.; Xie, J. Leaching behavior of air cooled Ti-bearing blast-furnace slag in hydrochloric acid. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2008, 18, 557–563. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.J.; Zhao, H.G.; Wang, Q.; Li, N.; Wu, Z.S. Leaching behavior of blast-furnace slag with Ti in hydrochloric acid. Light Met. 2016, 6, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, F.Q.; Chen, F.; Guo, Y.F.; Jiang, T.; Travyanov, A.Y.; Giu, G.Z. Kinetics of Hydrochloric Acid Leaching of Titanium from Titanium-Bearing Electric Furnace Slag. JOM 2016, 68, 1476–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordienko, P.S. A Process for the Production of Titanium Dioxide Using Aqueous Fluoride. CA2593639, 24 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bakeeva, N.G.; Gordienko, P.S.; Pashnina, E.V. Coprecipitation of titanium (IV) and Iron (III) complex salts from peroxide-fluoride solutions. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2008, 78, 527–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeeva, N.G.; Gordienko, P.S.; Pashnina, E.V. Preparation of high-purity titanium salts from the system (NH4)2TiF6-(NH4)3FeF6-NH4F-H2O. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2009, 79, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakeeva, N.G.; Gordienko, P.S.; Pashnina, E.V. Mutual influence of ammonium hexafluorotitanate and hexafluorosilicate in ammonium fluoride solutions. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2010, 80, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.Q.; Guo, Y.F.; Qiu, G.Z.; Chen, F.; Wang, S.; Sui, Y.L.; Jiang, T.; Yang, L.Z. A novel process for preparation of titanium dioxide from Ti-bearing electric furnace slag: NH4HF2-HF leaching and hydrolyzing process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 490–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Zhang, G.Q.; Wang, K.; Luo, D.M.; Tang, S.Y.; Yue, H.R. Two-stage cyclic ammonium sulfate roasting and leaching of extracting vanadium and titanium from vanadium slag. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2022, 47, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Q.Q.; Dou, Z.H.; Zhang, T.A. Phase conversion and removal of impurities during oxygen-rich alkali conversion of high titanium slag. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 1664–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, M.H.; El Hussaini, O.M.; El-Shahat, M.F. New method to prepare high purity anatase TiO2 through alkaline roasting and acid leaching from non-conventional minerals resource. Hydrometallurgy 2020, 195, 105399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ling, Y.Q.; Li, Q.N.; Zheng, H.W.; Jiang, Q.; Li, K.Q.; Gao, L.; Omran, M.; Chen, J. Highly efficient oxidation of Panzhihua titanium slag for manufacturing welding grade rutile titanium dioxide. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 7079–7086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui YLGuo, Y.F.; Jiang, T.; Qiu, G.Z. Separation and recovery of iron and titanium from oxidized vanadium titano-magnetite by gas-based reduction roasting and magnetic separation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 3036–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.Q.; Guo, Y.F.; Liu, S.S.; Qiu, G.Z.; Chen, F.; Jiang, T.; Wang, S. Removal of magnesium and calcium from electric furnace titanium slag by H3PO4 oxidation roasting–leaching process. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2018, 28, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elger, G.W.; Holmes, R.A. Purifying Titanium-Bearing Slag by Promoted Sulfation. US4362557, 7 December 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Elger, G.W.; Stadler, R.A.; Sanker, P.E. Process for Purifying a Titanium-Bearing Material and Upgrading Ilmenite to Synthetic Rutile with Sulfur Trioxide. US4120694A, 17 October 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, L.L.; Zhai, Y.C.; Miao, L.H. Recovery of titania from high titanium slag by roasting method using concentrated sulfuric acid. Rare Met. 2015, 34, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Lee, C.T.; Yu, Y.H. Reaction of Titanium Dioxide with Ammonium Sulfate. Korean Chem. Eng. Res. 1989, 27, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Fouad, O.A. Upgrading of a low-grade titanium slag by sulphation roasting technique to produce synthetic rutile. Acta Metall. Slovaca 2005, 11, 14–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, L.L.; Zhai, Y.C. Reaction kinetics of roasting high-titanium slag with concentrated sulfuric acid. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2014, 24, S1003–S6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. Recovery of titanium from titanium bearing blast furnace slag by sulfate melting. Can. Metall. Q. 2014, 53, 440–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Liu, W.Z.; Hu, J.P.; Liu, Q.; Yue, H.R.; Liang, B.; Zhang, G.Q.; Luo, D.M.; Xie, H.P.; Li, C. Indirect mineral carbonation of titanium-bearing blast furnace slag coupled with recovery of TiO2 and Al2O3. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 26, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.Z.; Feng, Y.L.; Li, H.R. Extraction of valuable metals from Ti-bearing blast furnace slag using ammonium sulfate pressurized pyrolysis–acid leaching processes. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2020, 30, 2836–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, Q.B. Preparation of rutile titanium dioxide from titanium slag using molten method. Appl. Chem. Ind. 2008, 37, 140–145. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Q.J.; Qi, T.; Liu, Y.M.; Wang, L.N.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of Potassium Titanate Whiskers and Titanium Dioxide from Titaniferous Slag Using KOH Sub-molten Salt Method. Chin. J. Process Eng. 2007, 7, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docters, T.; Chovelon, J.M.; Herrmann, J.M.; Deloume, J.P. Syntheses of TiO2 photocatalysts by the molten salts method. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2004, 50, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Q.Q.; Dou, Z.H.; Zhang, T.A.; Yang, Z.N. Study on the one-step acid conversion of the alkali conversion product of high titanium slag to prepare TiO2 of high purity. Hydrometallurgy 2022, 211, 105887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, T.Y.; Wang, L.N.; Qi, T.; Chu, J.L.; Qu, J.K.; Liu, C.H. Decomposition kinetics of titanium slag in sodium hydroxide system. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 95, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, L.N.; Chen, D.S.; Wang, W.J. Preparation of Rutile Titanium Dioxide White Pigment by a Novel NaOH Molten-Salt Process: Influence of Doping and Calcination. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2011, 34, 905–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.C.; Wang, D.; Xue, T.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Qi, T. Activation pretreatment of low-grade Ti-slag by alkali roasting: Anticaking technique and kinetics of decomposition. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 11, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarish, B. Upgrading Sorel Slag for Production of Synthetic Rutile. US4038363, 26 July 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.G.; Guo, Y.F.; Jiang, T.; Chen, J.; Fan, X.H. Production of synthetic rutile from high Ca and Mg type titanium slag by mineral phase reconstruction process. Chin. J. Nonferrous Met. 2012, 22, 2642–2647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, S.H.; Omran, M.; Gao, L.; Zheng, H.W.; Guo, C. Microwave-assisted preparation of nanocluster rutile TiO2 from titanium slag by NaOH-KOH mixture activation. Advanced Powder Technol. 2022, 33, 103549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leddy, J.J.; Schechter, D.L. Pressure Leaching of Titaniferous Material. US3060002, 23 October 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Samal, S.; Mohapatra, B.K.; Mukherjee, P.S. The Effect of Heat Treatment on Titania Slag. J. Miner. Mater. Charact. Eng. 2010, 9, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Zhou, Z.A.; Guo, Y.F. Thermodynamics Analysis for Redox Calcination of Titanium Slag Produced by Electric Furnace in Panzhihua. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 2016, 37, 13–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, M.; Ji ZYFan, X.H.; Lv WZheng, R.Y.; Chen, X.L.; Liu, S.; Jiang, T. Preparing high-strength titanium pellets for ironmaking as furnace protector: Optimum route for ilmenite oxidation and consolidation. Powder Technol. 2018, 333, 385–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.Q.; Guo, Y.F.; Duan, W.T.; Liu, S.S.; Qiu, G.Z.; Chen, F.; Jiang, T.; Wang, S. Transformation of Ti-bearing mineral in Panzhihua electric furnace titanium slag during oxidation roasting process. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 131, 1767–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.F.; Jing, J.F.; Yang, L.Z.; Chen, F.; Wang, S.; He, J. Kinetics and mineral transformations of panzhihua electric furnace titanium slag during oxidation roasting, Reaction Kinetics. Mech. Catal. 2022, 135, 915–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Chen, J.; Peng, J.H. Effects of mechanical activation on structural and microwave absorbing characteristics of high titanium slag. Powder Technol. 2015, 286, 218–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C. Rapid synthesis of rutile TiO2 powders using microwave heating. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 651, 503–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Song, Z.K.; Chen, J.; Srinivasakannan, C.; Peng, J.H. Investigation on phase transformation of titania slag using microwave irradiation. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 579, 612–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.Z.; Middlemas, S.; Guo, J.; Fan, P. A new, energy-efficient chemical pathway for extracting Ti metal from Ti minerals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 18248–18251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalabi, M.E.H.; Lasheen, T. Thermal treatment of titania slag under oxidation–reduction conditions. Eurasian Chem.-Technol. J. 2007, 9, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Z.Z.; Xia, Y.; Huang, Z.; Lefler, H.; Zhang, T.; Sun, P.; Free, M.L.; Guo, J. A novel chemical pathway for energy efficient production of Ti metal from upgraded titanium slag. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 286, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, G.Y.; Lei, C.; Zhu, Q.S.; Zhang, J.B.; Du, Z.; Yang, Y.F.; Fan, C.L. Dependence of Reduction Behaviors on the Molar Ratio of Fe2TiO5 and MgTi2O5 in the Pseudobrookite-Karrooite. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2016, 48, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, H.Y.; Meng, J.; Xie, G. Research on Reduction of Pre-oxidized Titanium Slag. Iron Steel Vanadium Titan. 2015, 36, 6–12. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyk, J.P.; Pistorius, P.C. Evaluation of a process that uses phosphate additions to upgrade titania slag. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 1999, 30, 823–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.G.; Yu, X.H.; Xu, Y.F. Study on the modification experimentation of acidsoluble titanium slag. China Nonferrous Metall. 2007, 4, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Guo, Y.F.; Qiu, G.Z.; Jiang, T.; Chen, F. Preparation of Ti-rich material from titanium slag by activation roasting followed by acid leaching. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2013, 23, 1174–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.F.; Liu, S.S.; Jiang, T.; Giu, G.Z.; Chen, F. A process for producing synthetic rutile from Panzhihua titanium slag. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 147–148, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; He, X.A.; Li, Y.H.; Feng, K.L.; Peng, J.H. A Method for Preparation of Rutile by Microwave Roasting and Phosphoric Acid Leaching. CN108793238A, 26 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; He, X.A.; Li, Y.H.; Feng, K.L.; Peng, J.H. A Method for Preparation of Artificial Rutile from High Titanium Slag by Phosphoric Acid Activation and Microwave Heating. CN107304067A, 31 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

| TiO2 | Fe | CaO | MgO | Al2O3 | SiO2 | Ref | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rio Tinto | 78.5 | 7.73 | 0.66 | 5.57 | 2.36 | 2.75 | [4,12] |

| QIT | 80 | 9 | 0.6 | 5 | 2.9 | 2.4 | [13,14] |

| Tinfos | 75.4 | 7.6 | 0.66 | 7.92 | 1.19 | 5.35 | [15] |

| RBM | 85.5 | 9.4 | 0.14 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 1.5 | [15] |

| Indian rare-earth Limite | 79.21 | 16.75 | 0.34 | 1.43 | 1.1 | [16] | |

| Panzhihua | 72.43 | 9.26 | 0.86 | 3.12 | 2.55 | 7.39 | [17] |

| YunNan | 86.37 | 2.36 | <0.05 | 1.32 | 6.16 | 4.66 | [18] |

| Minerals | Anosovite | Ilmenite | Anatase | Metallic Iron | Olivine and Enstatite | Glass | Others |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content/% | 86.6 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 5.8 | 2.4 | 0.2 |

| Methods | Raw Material | Reaction Temperature | Waste Liquid and Residue | Reagent Cycle | Product Crystals | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2SO4 leaching | Titanium concentrate and titanium slag | 120~250 °C | Acid hydrolysis residue, waste acid, acid waste water | Some sulfuric acid can be recycled | Anatase and rutile | [21,22] |

| HCl leaching | Ilmenite and titanium slag | 80~100 °C | Acid hydrolysis residue, acid waste water | Hydrochloric acid can be recycled | Anatase and rutile | [23] |

| Fluoride leaching | Ilmenite, perovskite, rutile, high titanium slag, etc. | 100~140 °C | Thermal hydrolysis residue | Fluorinated reagents can be recycled | Anatase and rutile | [24] |

| Ammonia decomposition leaching | High titanium slag | 150 °C | Waste residue and ammonia | Ammonia can be recycled | Anatase | [25] |

| Methods | Reaction Temperature | TiO2 | Additives | (CaO, MgO) Removal Rate/Content | Waste Residues, Waste Liquids, and Waste Gases | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfur roasting–leaching | 300~800 °C | >98% | SO2/(NH4)2SO4 | 91.9%, 91.4% | Acid water, sulfate NH3/SO2, | [42] |

| Alkaline roasting–leaching | 800~1000 °C | >99% | NaOH/NaHCO3/Na2CO3 | 91.5%, 89.7% | Alkaline waste water, alkali salts | [43,44] |

| Oxide roasting–leaching | 1200~1550 °C | 98% | 96.5%, 94.3% | Acid water | [45] | |

| Oxide and reduction roasting–leaching | 800~1000 °C | >99% | 93.1%, 94.5% | Acid water | [46] | |

| Phosphorylation roasting–leaching | 800~1200 °C | 94% | H3PO4 | 87.19%, 94,68% | Acid water, phosphate | [47] |

| Methods | Titanium-Containing Phases | Impurity Phase | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| H2SO4 leaching | TiOSO4, H2TiO3, TiO2 | Fe2(SO4)3, MgSO4, CaSO4, Al2(SO4)3, H2SiO3 | [29] |

| HCl leaching | TiOCl2, H2TiO3, TiO2 | FeCl3, MgCl2, AlCl3, CaCl2, H2SiO3 | [34] |

| Fluoride leaching | (NH4)2TiF6, (NH4)3TiO2F5, TiO2, TiOF2 | (NH4)2SiF6, (NH4)2FeF6, CaF2, CaMg2Al2F12, NH4MgAlF6 | [41] |

| Ammonia decomposition leaching | (NH4)2TiO3, TiO2 | Fe(OH)3,Mg(OH)2,Ca(OH)2,Al(OH)3 | [25] |

| Sulfur roasting–leaching | TiOSO4, H2TiO3, TiO2 | Fe2(SO4)3, MgSO4, CaSO4, Al2(SO4)3, H2SiO3 | [53] |

| Alkaline roasting–leaching | Na2TiO3, TiO2 | Na2SiO3, NaAlO2, CaO, MgO, FeO | [11,65] |

| Oxide roasting–leaching | TiO2, MxTi3−xO5(0 < x < 2, M = Ti, Fe, Al, Mg, etc.) | Fe2(SO4)3, MgSO4, CaSO4, Al2(SO4)3, FeCl3, MgCl2, AlCl3, CaCl2, H2SiO3 | [72] |

| Oxidation and reduction roasting–leaching | TiO2, MxTi3−xO5(0 < x < 2, M = Ti, Fe, Al, Mg, etc.) | Fe2(SO4)3, MgSO4, CaSO4, Al2(SO4)3, FeCl3, MgCl2, AlCl3, CaCl2, H2SiO3 | [77] |

| Phosphorylation roasting–leaching | TiO2 | Mg3(PO4)2, FePO4, AlPO4, Ca3(PO4)2, SiO2 | [83,84] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jing, J.; Guo, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, F.; Yang, L.; Qiu, G. Recent Progress in Electric Furnace Titanium Slag Processing and Utilization: A Review. Crystals 2022, 12, 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst12070958

Jing J, Guo Y, Wang S, Chen F, Yang L, Qiu G. Recent Progress in Electric Furnace Titanium Slag Processing and Utilization: A Review. Crystals. 2022; 12(7):958. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst12070958

Chicago/Turabian StyleJing, Jianfa, Yufeng Guo, Shuai Wang, Feng Chen, Lingzhi Yang, and Guanzhou Qiu. 2022. "Recent Progress in Electric Furnace Titanium Slag Processing and Utilization: A Review" Crystals 12, no. 7: 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst12070958

APA StyleJing, J., Guo, Y., Wang, S., Chen, F., Yang, L., & Qiu, G. (2022). Recent Progress in Electric Furnace Titanium Slag Processing and Utilization: A Review. Crystals, 12(7), 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst12070958