Incorporation of Cd-Doping in SnO2

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. TDPAC Methodology

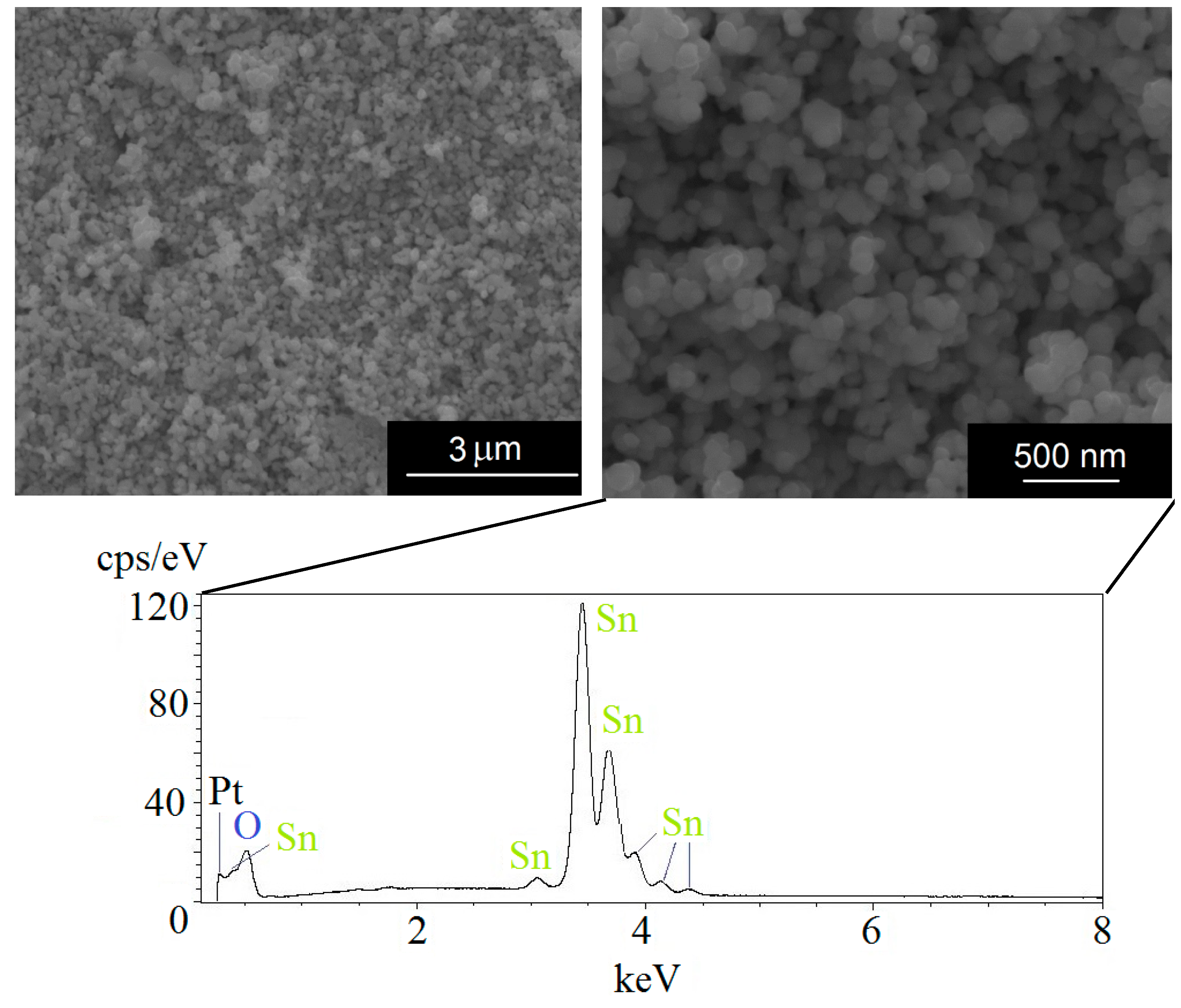

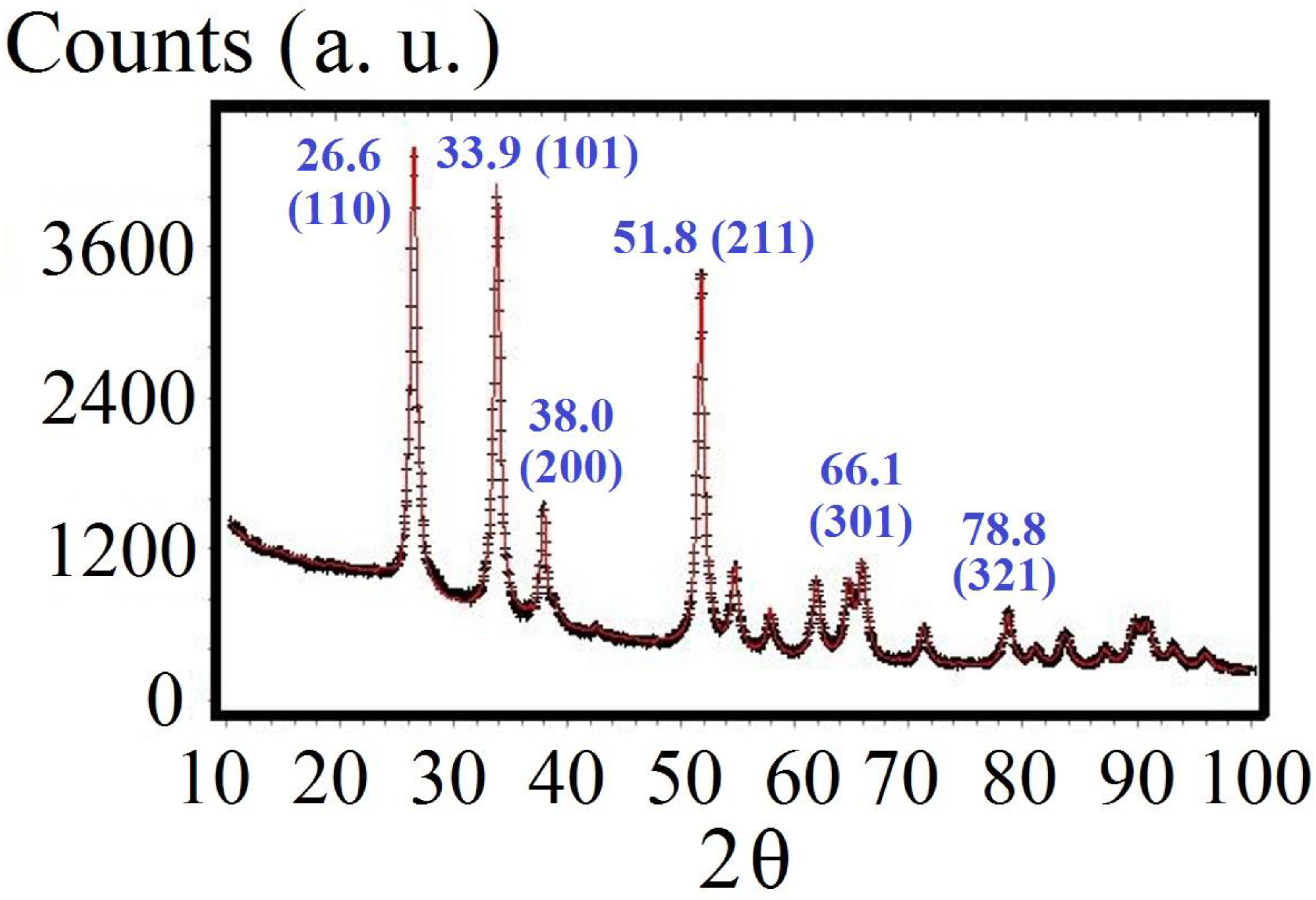

3. Experimental Methods

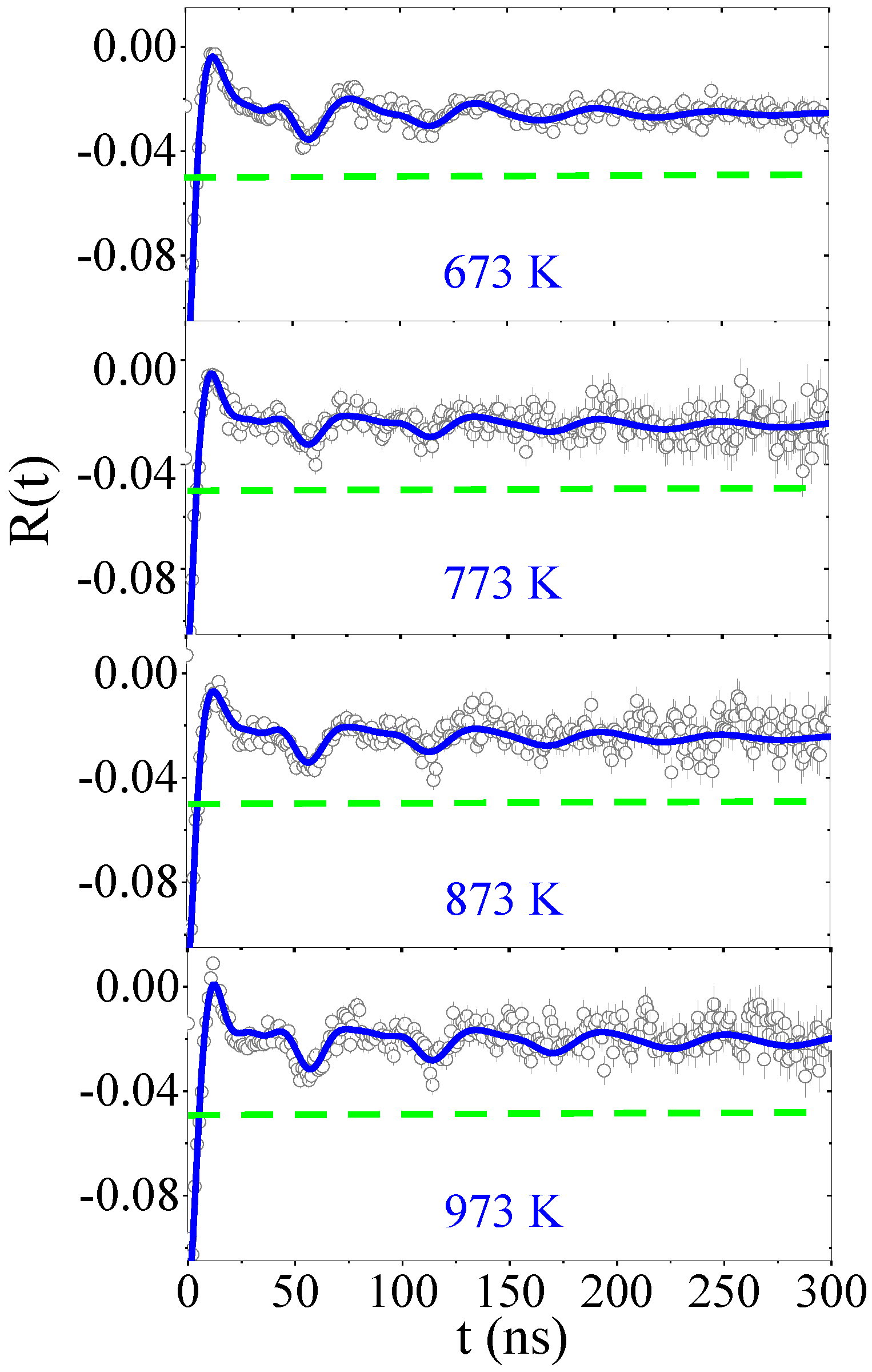

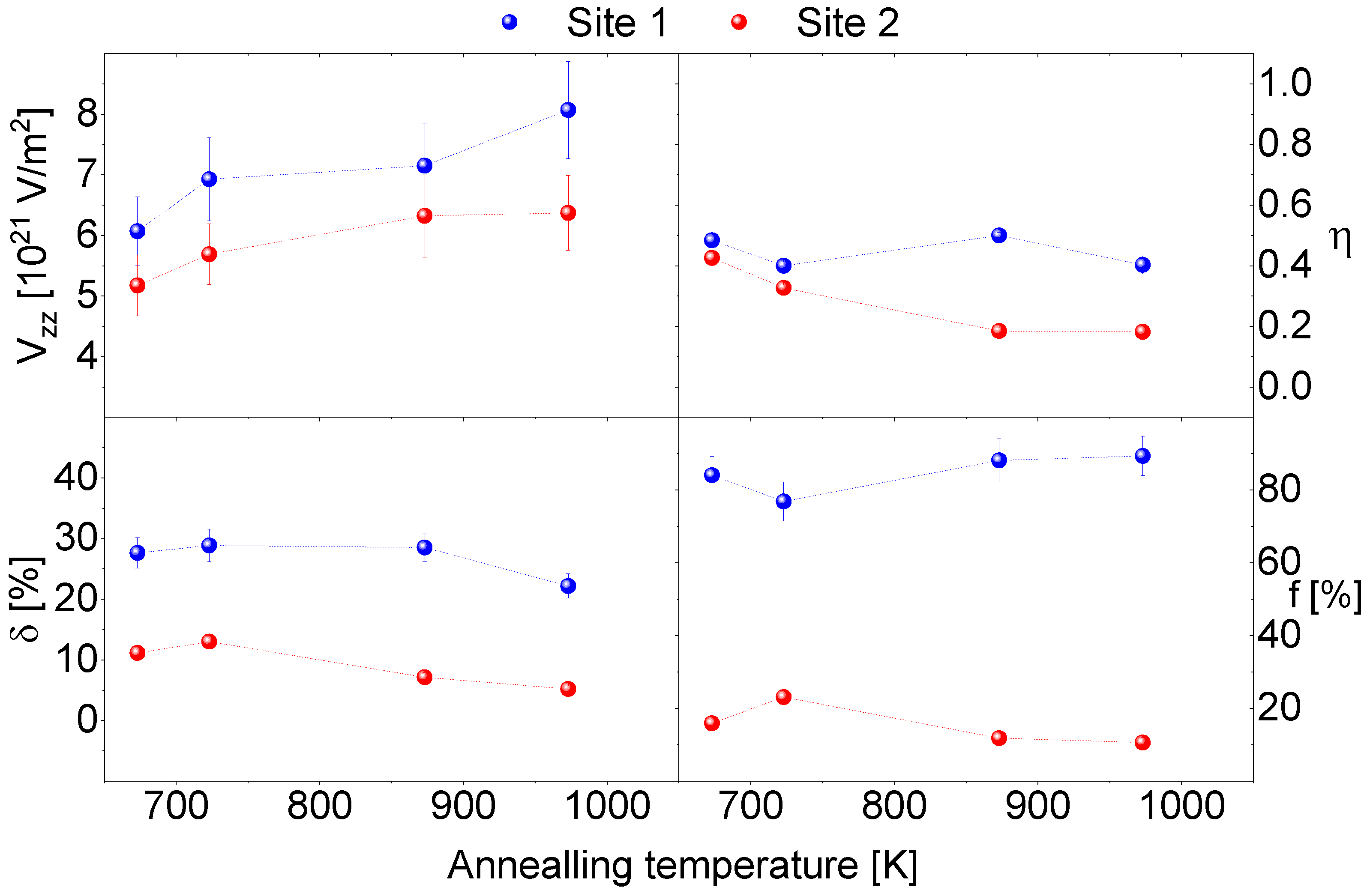

4. Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kiliç, Ç.; Zunger, A. Origins of coexistence of conductivity and transparency in SnO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2002, 88, 095501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Yu, K.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Wei, C. Construction of 1D SnO2-coated ZnO nanowire heterojunction for their improved n-butylamine sensing performances. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 35079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yan, Y.; Liu, T. Octahedral tin dioxide nanocrystals anchored on vertically aligned carbon aerogels as high capacity anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 31496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, A.; Børresen, B.; Hagenm, G.; Tsypkin, M.; Tunold, R. Preparation and characterisation of nanocrystalline IrxSn1−xO2 electrocatalytic powders. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2005, 94, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.; Alves, P.D.P.; de Andrade, A.R. Effect of the preparation methodology on some physical and electrochemical properties of Ti/IrxSn(1−x)O2 materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 9293–9299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardizzone, S.; Bianchi, C.L.; Borgese, L.; Cappelletti, G.; Locatelli, C.; Minguzzi, A.; Rondinini, S.; Vertova, A.; Ricci, P.C.; Cannas, C.; et al. Physico-chemical characterization of IrO2–SnO2 sol-gel nanopowders for electrochemical applications. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2009, 39, 2093–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tianshu, Z.; Hing, P.; Li, Y.; Jiancheng, Z. Selective detection of ethanol vapor and hydrogen using Cd-doped SnO2-based sensors. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 1999, 60, 208–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhou, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, B.; Xu, X.; Lu, G. One-step synthesis and gas sensing properties of hierarchical Cd-doped SnO2 nanostructures. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2014, 190, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, J.; Lupascu, D.C.; Carbonari, A.W.; Mansano, R.D.; Dang, T.T.; Vianden, R. Implantation of cobalt in SnO2 thin films studied by TDPAC. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 055304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, J.; Lupascu, D.C.; Carbonari, A.W.; Mansano, R.D.; Freitas, R.S.; Goncalves, J.N.; Dang, T.T.; ISOLDE Collaboration; Vianden, R. Cd and In-doping in thin film SnO2. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 121, 195303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimoni, J.; Bibiloni, A.G.; Mendoza-Zélis, L.A.; Damonte, L.C.; Sanchez, F.H.; Lopez-Garcia, A. Tdpac studies in the semiconductors SnO2 and Cu2O. Hyperfine Interact. 1987, 34, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renteria, M.; Bibiloni, A.G.; Moreno, M.S.; Desimoni, J.; Mercader, R.C.; Bartos, A.; Uhrmacher, M.; Lieb, K.P. Hyperfine interactions of 111In-implanted tin oxide thin films. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 1991, 9, 3625. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, H.; Deubler, S.; Forkel, D.; Foettinger, H.; Iwatschenko-Borho, M.; Meyer, M.; Rem, M.; Witthuhn, W. Acceptors and Donors in the Wide-Gap Semiconductors ZnO and SnO2. Mater. Sci. Forum 1986, 10, 863–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.M.; Carbonari, A.W.; Costa, M.S.; Saxena, R.N. Electric quadrupole interactions in nano-structured SnO2 as measured with PAC spectroscopy. Hyperfine Interact. 2010, 197, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, J.M.; Martucci, T.; Carbonari, A.W.; Costa, M.S.; Saxena, R.N.; Vianden, R. Electric field gradient in nanostructured SnO2 studied by means of PAC spectroscopy using 111 Cd or 181 Ta as probe nuclei. Hyperfine Interact. 2013, 221, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, E.L.; Carbonari, A.W.; Errico, L.A.; Bibiloni, A.G.; Petrilli, H.; Renteria, M. TDPAC study of Cd-doped SnO. Hyperfine Interact. 2007, 178, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, G.N.; Muñoz, E.L.; Carbonari, A.W.; Rentería, M. Experimental TDPAC and Theoretical DFT Study of Structural, Electronic, and Hyperfine Properties in (111In→) 111Cd-Doped SnO2 Semiconductor: Ab Initio Modeling of the Electron-Capture-Decay After-Effects Phenomenon. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 17423–17436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, J.; Schell, J. Investigação de parâmetros hiperfinos dos óxidos semicondutores SnO2 e TiO2 puros e dopados com metais de transição 3d pela espectroscopia de correlação angular gama-gama perturbada. Available online: https://teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/85/85131/tde-24032015-135507/en.php (accessed on 19 February 2015).

- Schatz, G.; Weidinger, A. Nuclear Condensed Matter Physics: Nuclear Methods and Applications; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Abragam, A.; Pound, R.V. Influence of electric and magnetic fields on angular correlations. Phys. Rev. 1953, 92, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzan, A.A.; Fong, C.; Kennedy, B.J.; Howard, C.J. Structural studies of rutile-type metal dioxides. Acta Crystallogr. B 1997, 53, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Khan, S.; Ansari, M.M.N. Microstructural, optical and electrical transport properties of Cd-doped SnO2 nanoparticles. Mater. Res. Express 2018, 5, 035045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catherall, R.; Andreazza, W.; Breitenfeldt, M.; Dorsival, A.; Focker, G.J.; Gharsa, T.P.; Giles, T.; Grenard, J.-L.; Locci, F.; Martins, P.; et al. The ISOLDE facility. J. Phys. G 2017, 44, 094002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, K.; Schell, J.; Correia, J.G.; Deicher, M.; Gunnlaugsson, H.P.; Fenta, A.S.; David-Bosne, E.; Costa, A.R.G.; Lupascu, D.C. The solid state physics programme at ISOLDE: Recent developments and perspectives. J. Phys. G Nucl. Part. Phys. 2017, 44, 104001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schell, J.; Lupascu, D.C.; Correia, J.G.M.; Carbonari, A.W.; Deicher, M.; Barbosa, M.B.; Mansano, R.D.; Johnston, K.; Ribeiro, I.S., Jr.; ISOLDE Collaboration. In and Cd as defect traps in titanium dioxide. Hyperfine Interact. 2017, 238, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schell, J.; Dang, T.T.; Carbonari, A.W. Incorporation of Cd-Doping in SnO2. Crystals 2020, 10, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10010035

Schell J, Dang TT, Carbonari AW. Incorporation of Cd-Doping in SnO2. Crystals. 2020; 10(1):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10010035

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchell, J., T. T. Dang, and A. W. Carbonari. 2020. "Incorporation of Cd-Doping in SnO2" Crystals 10, no. 1: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10010035

APA StyleSchell, J., Dang, T. T., & Carbonari, A. W. (2020). Incorporation of Cd-Doping in SnO2. Crystals, 10(1), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst10010035