To Tender or Not to Tender? Deliberate and Exogenous Sunk Costs in a Public Good Game

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

- Endogenous prize contests,

- Public good games with entry option and

- Sunk costs

2.1. Endogenous Prize Contests

- Escape the outside option for treatments where it is risky.

- Risk or loss averse individuals entering the market early, under the expectation that only few other players would enter, refrain from placing a high bid upon observing that there were in fact unexpectedly many entrants to the market.

2.2. Public Good Games with Entry Option

2.3. Sunk Costs

3. Setup

- First stage

- Each player receives an endowment of tokens. For a price of 1 token per ticket, they can purchase up to 100 tickets for the contest. Spendings of subject k in group K and m in group M are labelled and , respectively. Tokens that are not spent for the contest will be added to the player’s private account. With being the probability for group K to win over group M, the contest success function (CSF) similar to [1,2] is

- Second stage

- Players learn if their group has won or lost, other group’s first stage spending level, the corresponding winning probability and their group mates’ wealth level . Then, each group plays a public good game with being individual i’s investment into the public good.5 For this, subjects can invest a maximum of 100 tokens.6 The winning group will enjoy a high MPCR of . The losing group will be facing a low MPCR of .7 Individual payoff is then determined by:

- First stage

- Each player receives an endowment of tokens. Individual factors are induced, matching another group’s behaviour in the competition treatment and deducted from T.

- Second stage

- Groups play a public good game. Players see the current wealth level of their group mates (being ) and the wealth level of the other group they are connected with. Keeping in line with the matched groups from the competition treatment, the MPCR will be or . Individual payoff is determined by:

Procedures

4. Hypotheses

4.1. Standard Predictions

4.2. Behavioural Hypotheses—Group Behaviour

- Groups end up winning the contest because they have more competitive players, or

4.3. Behavioural Hypotheses—Individual Behaviour

5. Results

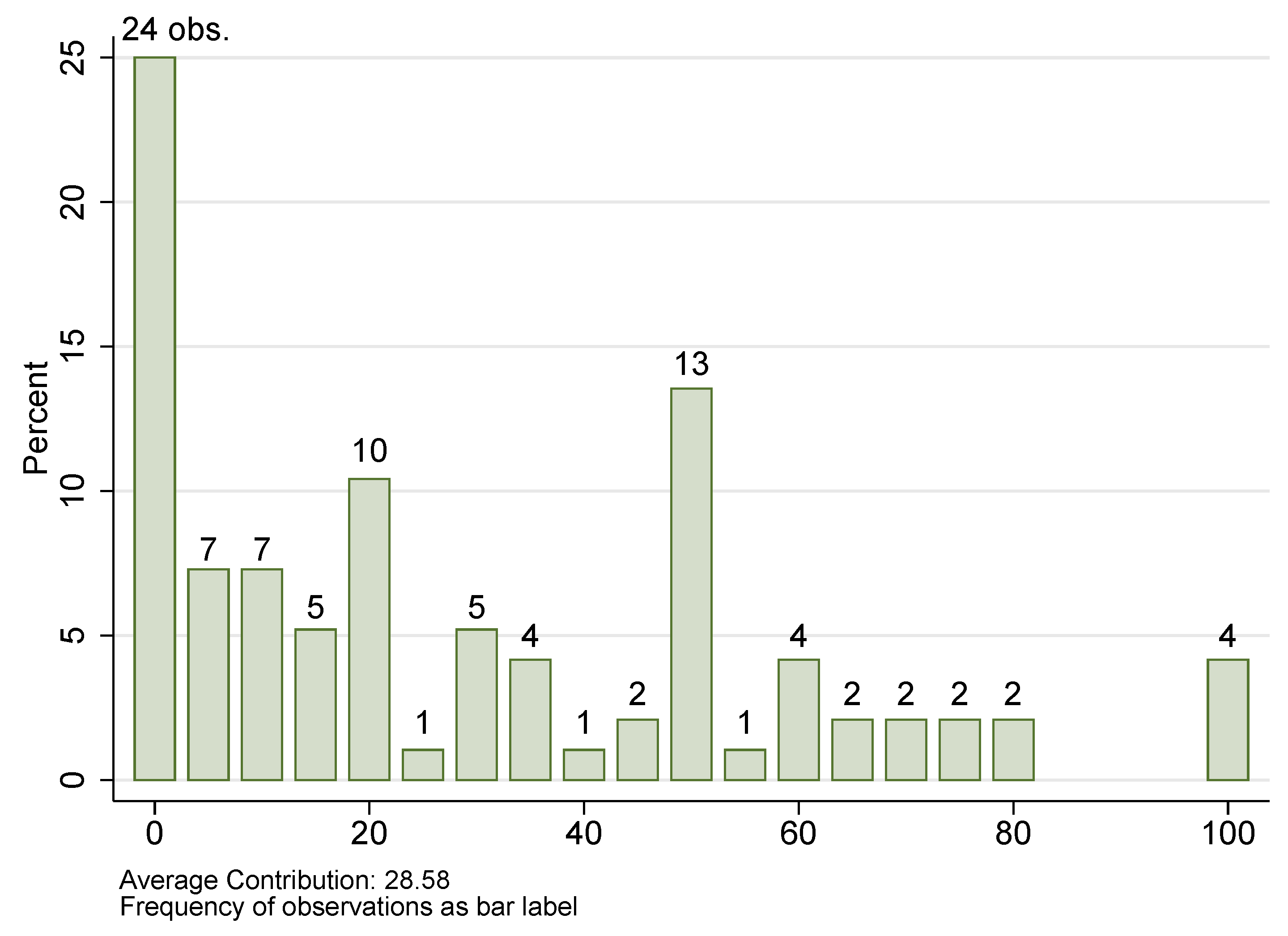

5.1. Team Contest

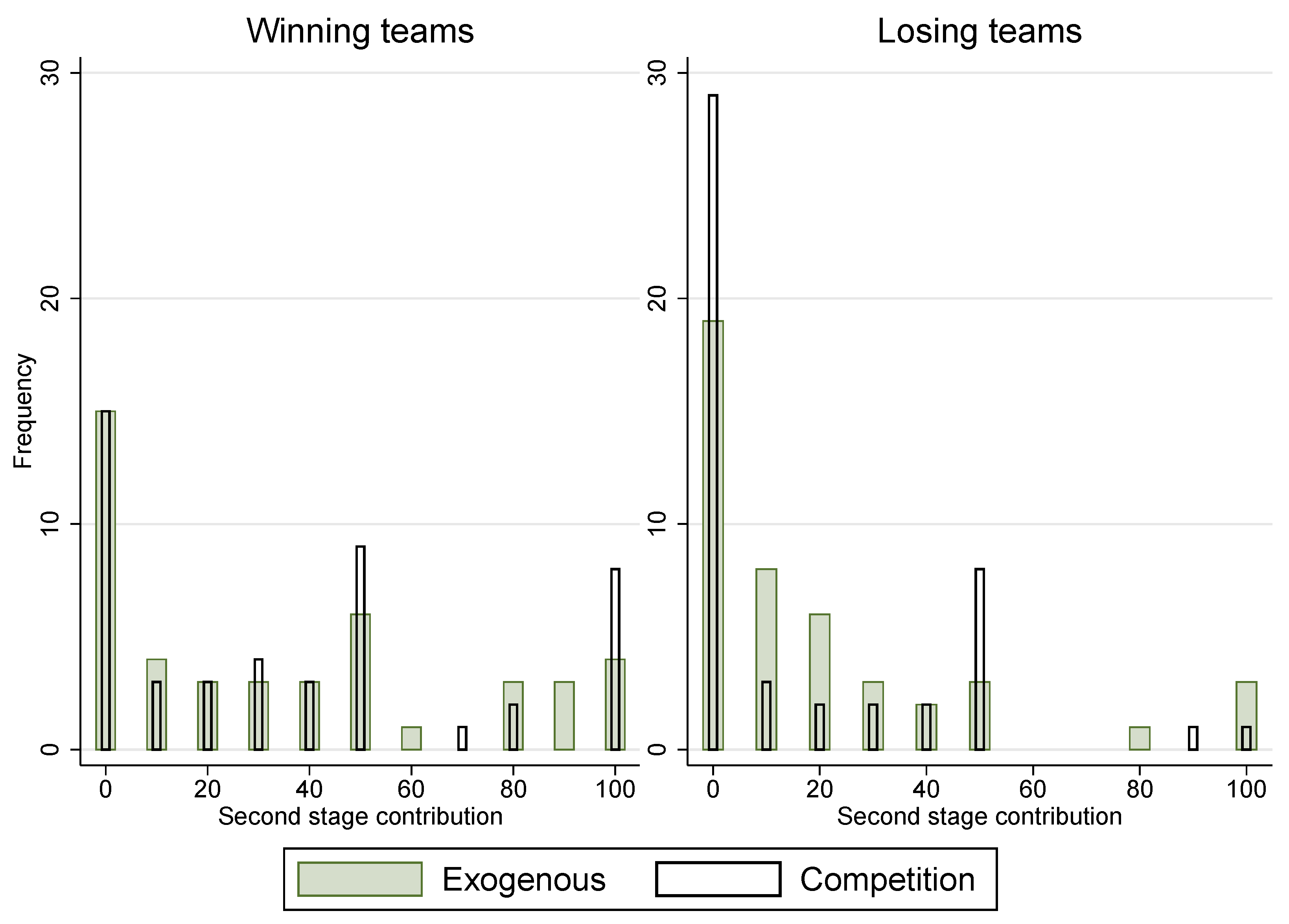

5.2. Second Stage Contribution

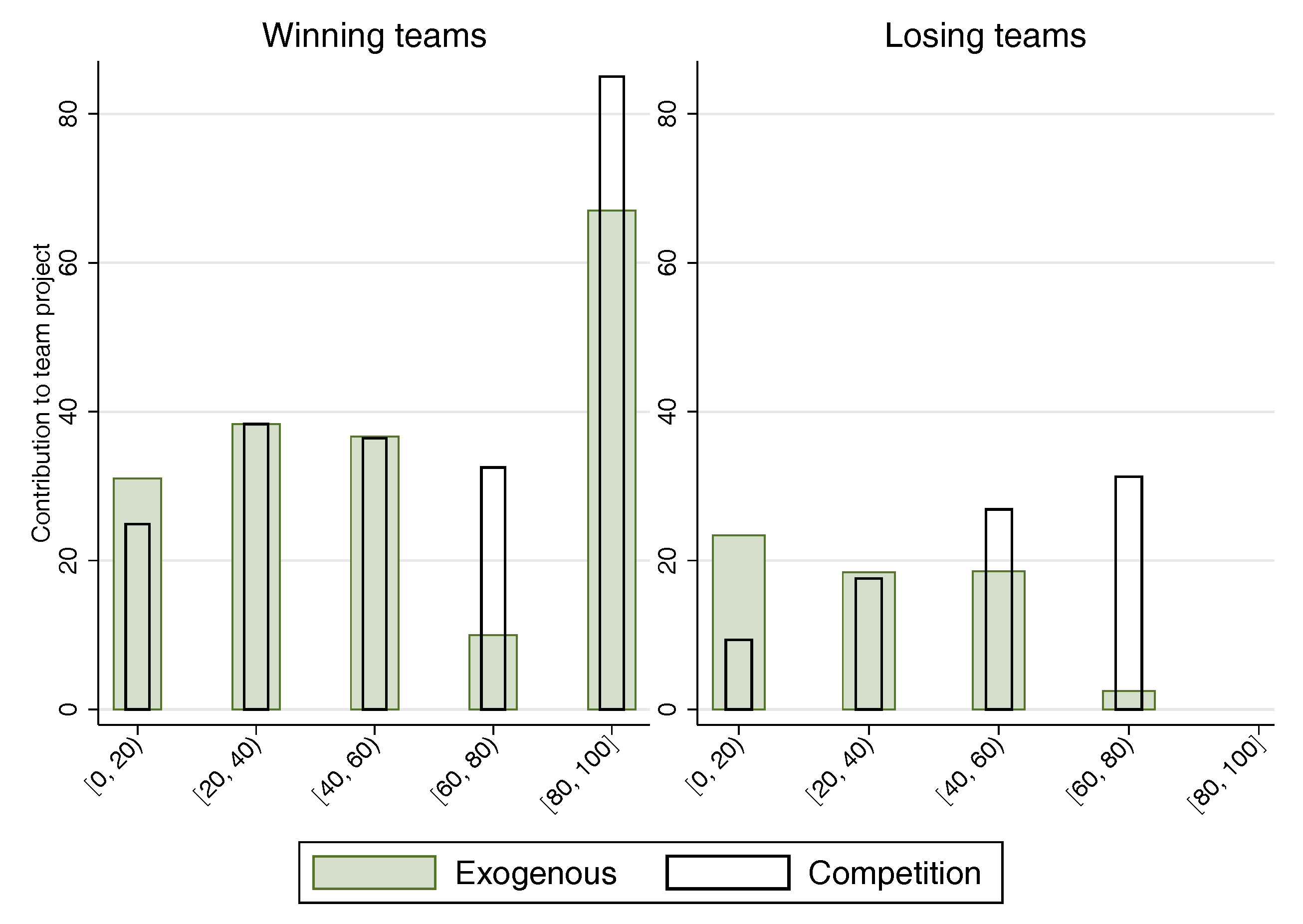

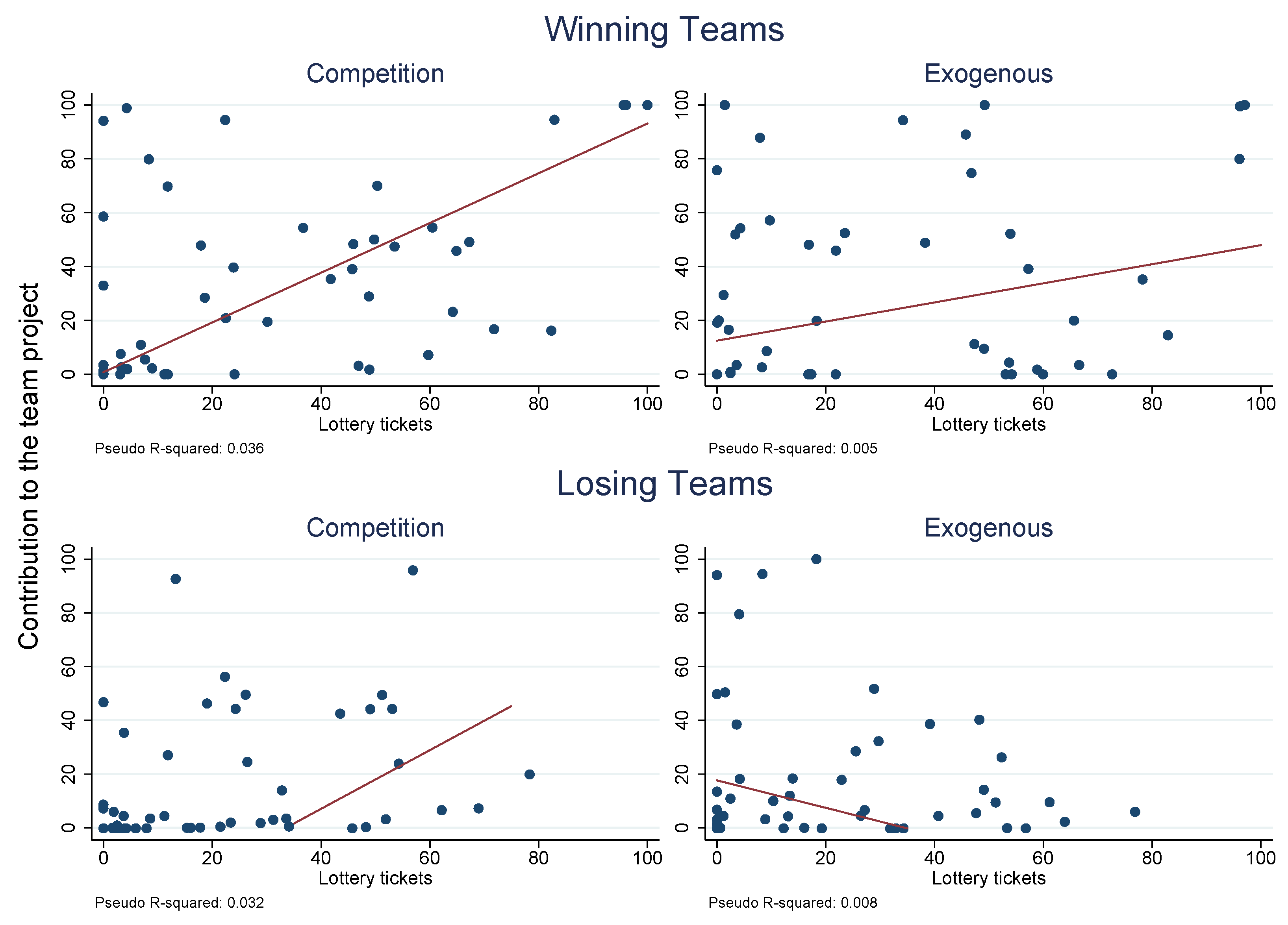

5.3. Relation between First and Second Stage Contribution

- Exogenous lose

- Player in the exogenous treatment in a group that lost in the first stage.

- Exogenous win

- Player in the exogenous treatment in a group that won in the first stage.

- Competition lose

- Player in the competition treatment in a group that lost in the first stage. This is the default in regressions (3) through (2).

- Competition win

- Player in the competition treatment in a group that won in the first stage.

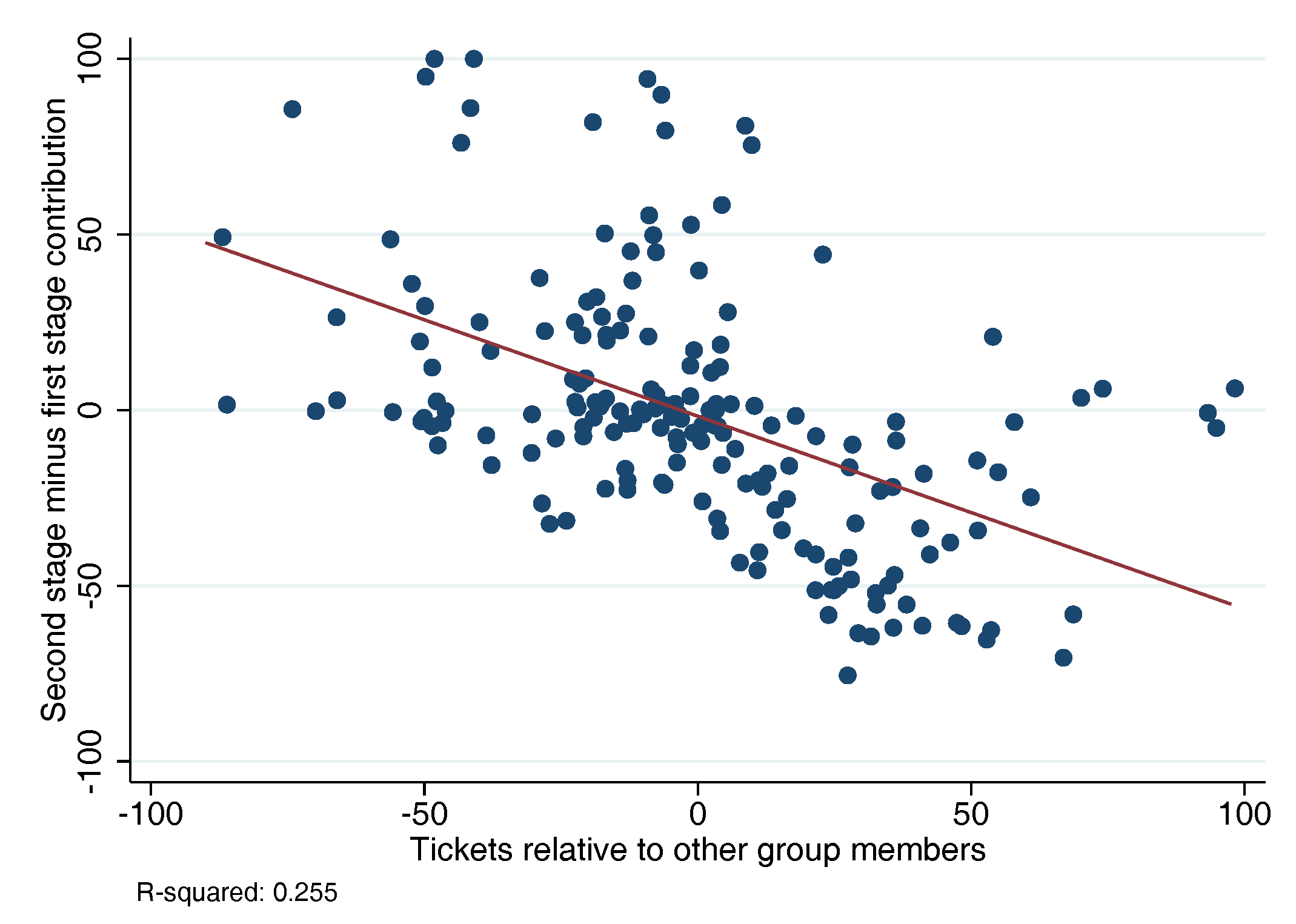

5.4. Regression to the Mean

6. Discussion

7. Materials and Methods

7.1. Instructions

7.1.1. Instructions Part 1

7.1.2. Instructions Part 2

| Winning team: | |

| Your Endowment | |

| − | Your tickets (between 0 and 100) |

| − | Your contribution to the team project (between 0 and 100) |

| + | your team’s total contribution to the team project |

| = | Your earnings |

| Losing team: | |

| Your Endowment | |

| − | Your tickets (between 0 and 100) |

| − | Your contribution to the team project (between 0 and 100) |

| + | your team’s total contribution to the team project |

| = | Your earnings |

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

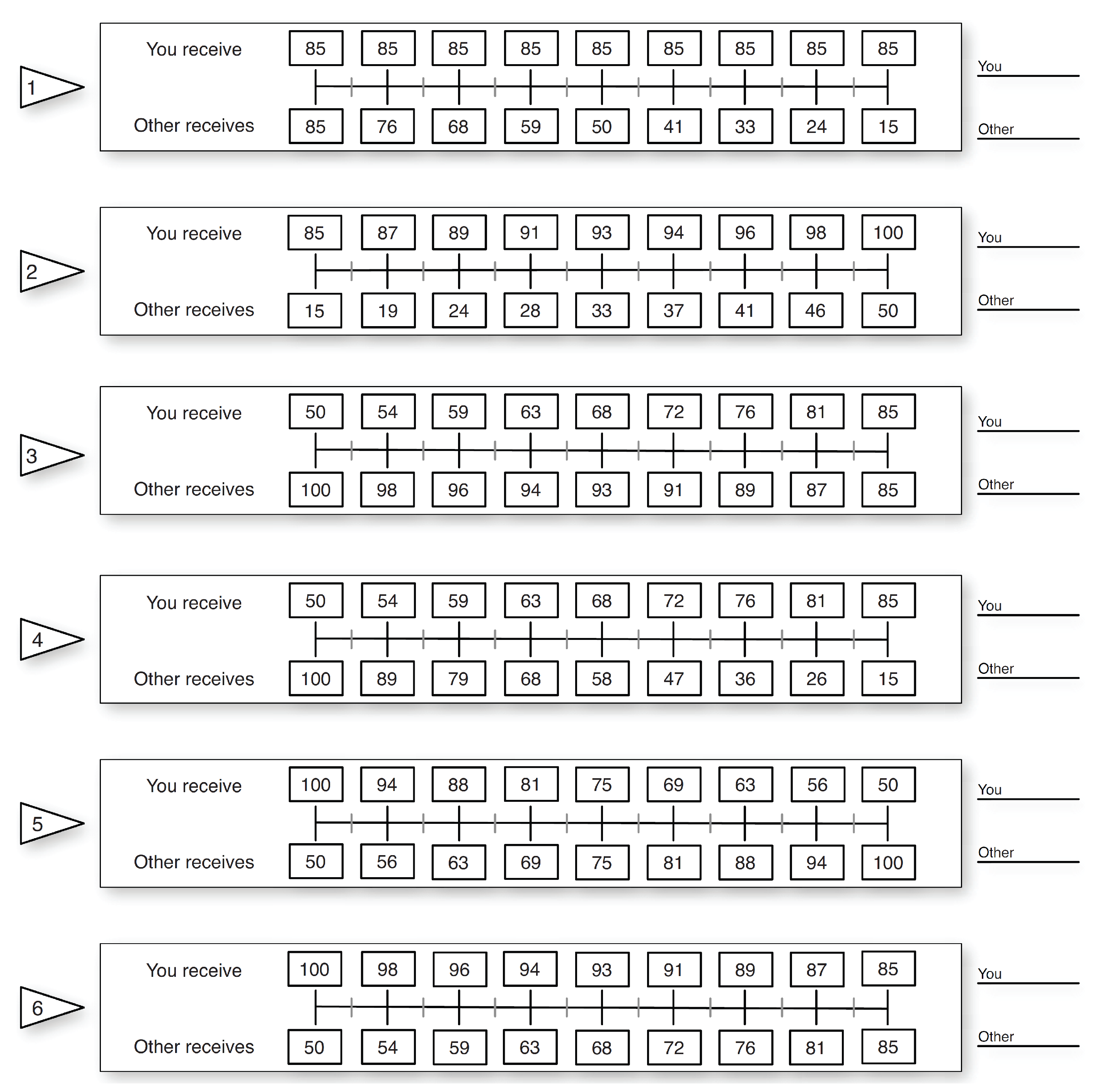

Appendix A. Social Value Orientation-Measure

Appendix B. Risk Neutral Equilibrium

- Second stage

- Players individually maximise their profit by setting own contribution :with . As and , there exists a corner solution .

- First stage

- Under common knowledge of rationality, players know that and maximisewith being the expected earnings from stage 2. Again, a corner solution exists with .

Appendix C. Contest Expenditures—The Role of Beliefs

- Second stage

- Player i’s payoff depends positively on her teammates’ input towards the team project , as in:Hence, player i’s most optimistic belief for the second stage would involve full contribution by all other group members, i.e., , which would amount to an account of and expected second stage earnings of for a winning group.

- First stage

- Most pessimistic beliefs about teammates’ contest spending behaviour are characterised as . If all teammates do not buy lottery tickets () and expected second stage payoff , player i maximises Equation (A2) at .Consider as alternative belief on first stage behaviour, that all teammates contribute symmetrically, i.e., . For this set of beliefs, Equation (A2) maximises at .

Appendix D. Additional Regressions

| Variables | (7) | (8) |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage Contribute | ||

| Social value orientation (SVO) | 0.529 ** | 0.395 * |

| (0.22) | (0.22) | |

| Risk parameter | 2.708 | |

| (2.03) | ||

| Female | 15.299 ** | |

| (6.55) | ||

| Age | 3.567 ** | |

| (1.49) | ||

| Number of siblings | −1.632 | |

| (2.76) | ||

| Smoking | 3.882 | |

| (12.64) | ||

| Politics important | −3.164 | |

| (3.65) | ||

| Trust in others | 13.727 ** | |

| (5.96) | ||

| Income Equality | −3.067 * | |

| (1.78) | ||

| Hard work | −1.119 | |

| (1.69) | ||

| Constant | 19.614 *** | −73.035 * |

| (4.62) | (36.93) | |

| N | 96 | 93 |

| R-squared | 0.060 | 0.435 |

| Variables | (9) | (10) | (11) | (12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Stage Contribute | ||||

| First stage | 0.241 *** | 0.210 ** | 0.269 * | 0.336 * |

| Contribute | (0.09) | (0.10) | (0.14) | (0.19) |

| Group Contribute | 0.108 * | 0.093 | 0.149 ** | 0.117 |

| Minus Self | (0.06) | (0.07) | (0.06) | (0.08) |

| Social value | 0.435 ** | 0.327 * | 0.355 * | 0.284 |

| orientation (SVO) | (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.19) | (0.19) |

| Exogenous lose | 2.557 | 5.381 | 17.171 ** | 18.633 * |

| (5.26) | (6.09) | (7.57) | (10.52) | |

| Exogenous win | 12.196 * | 12.697 * | 12.421 * | 16.964 * |

| (6.58) | (6.40) | (6.68) | (8.50) | |

| Competition win | 15.012 *** | 13.994 ** | 5.377 | 9.693 |

| (5.37) | (6.73) | (8.31) | (10.72) | |

| Exogenous lose | −0.635 *** | −0.577 * | ||

| × First stage Contr. | (0.21) | (0.30) | ||

| Exogenous win | −0.039 | −0.181 | ||

| × First stage Contr. | (0.18) | (0.24) | ||

| Competition win | 0.249 | 0.072 | ||

| × First stage Contr. | (0.21) | (0.27) | ||

| Constant | −1.255 | −39.688 | −2.461 | −39.307 |

| (4.85) | (32.75) | (5.41) | (34.09) | |

| Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| N | 186 | 181 | 186 | 181 |

| R-squared | 0.166 | 0.310 | 0.221 | 0.336 |

| (a) Exogenous Treatment. | ||||

| Variables | Contribution to the Team Project | |||

| (13) | (14) | (15) | (16) | |

| Exogenous Lose | Exogenous Win | |||

| First stage | −0.896 ** | −0.559 | 0.205 | 0.504 * |

| Contribute | (0.38) | (0.36) | (0.33) | (0.25) |

| Group Contribute | 0.142 | 0.076 | 0.570 *** | 0.619 *** |

| Minus Self | (0.24) | (0.20) | (0.18) | (0.14) |

| Social value | 0.062 | 0.025 | −0.033 | 0.335 |

| orientation (SVO) | (0.45) | (0.32) | (0.51) | (0.62) |

| Constant | −35.603 | 14.801 | −245.801 ** | −41.283 ** |

| (70.81) | (14.87) | (102.83) | (20.20) | |

| Controls | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| N | 43 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.138 | 0.008 | 0.143 | 0.035 |

| (b) Competition Treatment. | ||||

| Variables | Contribution to the Team Project | |||

| (17) | (18) | (19) | (20) | |

| Competition Lose | Competition Win | |||

| First stage | −0.095 | 0.817 ** | 0.080 | 0.664 ** |

| Contribute | (0.26) | (0.35) | (0.26) | (0.31) |

| Group Contribute | 0.509 *** | 0.572 *** | 0.003 | −0.066 |

| Minus Self | (0.18) | (0.19) | (0.20) | (0.23) |

| Social value | 1.852 ** | 1.646 ** | 1.020 ** | 1.671 * |

| orientation (SVO) | (0.71) | (0.73) | (0.37) | (0.91) |

| Constant | 58.374 | −85.612 *** | −333.308 *** | −15.653 |

| (79.29) | (23.42) | (82.57) | (25.38) | |

| Controls | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| N | 46 | 48 | 47 | 48 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.206 | 0.074 | 0.203 | 0.056 |

| Variables | Second stage Contribute | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (5.1) | (6.1) | (5.2) | (6.2) | |

| Exogenous lose | Exogenous win | |||

| First stage | -0.512 | -0.776** | 0.345 | -0.038 |

| Contribute | (0.32) | (0.32) | (0.24) | (0.36) |

| Social value | -0.018 | 0.116 | 0.141 | -0.197 |

| orientation (SVO) | (0.34) | (0.43) | (0.75) | (0.49) |

| Constant | 18.011 | -17.204 | 10.284 | -213.785* |

| (12.96) | (63.02) | (18.44) | (106.81) | |

| Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| N | 45 | 43 | 45 | 45 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.008 | 0.137 | 0.005 | 0.117 |

Appendix E. Control Variables

| Variables | (4) | (6) |

|---|---|---|

| Second Stage Contribute | ||

| First stage | 0.360 ** | 0.912 ** |

| Contribute | (0.17) | (0.37) |

| Group Contribute | 0.223 * | 0.262 ** |

| Minus Self | (0.12) | (0.12) |

| Social value | 0.809 ** | 0.721 ** |

| orientation (SVO) | (0.34) | (0.34) |

| Exogenous lose | 16.488 | 49.942 ** |

| (11.51) | (19.30) | |

| Exogenous win | 25.530 ** | 44.400 ** |

| (12.02) | (17.82) | |

| Competition win | 28.767 ** | 32.699 |

| (12.50) | (20.46) | |

| Risk parameter | 7.270 * | 6.264 |

| (3.69) | (3.94) | |

| Female | 10.767 | 8.824 |

| (10.13) | (9.35) | |

| Age | 3.484 * | 2.890 |

| (1.84) | (1.84) | |

| Number of siblings | 4.185 | 4.356 |

| (3.84) | (3.87) | |

| Smoking | −12.913 | −12.770 |

| (20.72) | (21.75) | |

| Politics important | −14.725 ** | −14.478 ** |

| (6.12) | (6.19) | |

| Trust in others | 11.438 | 7.464 |

| (7.79) | (7.63) | |

| Income Equality | 2.121 | 2.914 |

| (2.78) | (2.91) | |

| Hard work | −5.231 ** | −4.427 * |

| (2.47) | (2.50) | |

| Exogenous lose | −1.419 ** | |

| × First stage Contr. | (0.56) | |

| Exogenous win | −0.720 | |

| × First stage Contr. | (0.44) | |

| Competition win | −0.282 | |

| × First stage Contr. | (0.50) | |

| Constant | −127.493 ** | −130.816 ** |

| (50.81) | (53.69) | |

| N | 181 | 181 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.067 | 0.073 |

| Variables | Contribution to the Team Project | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (13) | (15) | (17) | (19) | |

| Exogenous Lose | Exogenous Win | Competition Lose | Competition Win | |

| First stage | −0.896 ** | 0.205 | −0.095 | 0.080 |

| Contribute | (0.38) | (0.33) | (0.26) | (0.26) |

| Group Contribute | 0.142 | 0.570 *** | 0.509 *** | 0.003 |

| Minus Self | (0.24) | (0.18) | (0.18) | (0.20) |

| Social value | 0.062 | −0.033 | 1.852 ** | 1.020 ** |

| orientation (SVO) | (0.45) | (0.51) | (0.71) | (0.37) |

| Risk parameter | −2.719 | 15.760 * | −5.537 | 22.633 *** |

| (6.71) | (7.66) | (5.28) | (6.85) | |

| Female | 24.237 ** | 43.473 | 16.922 | 37.388 * |

| (11.42) | (25.80) | (15.72) | (19.14) | |

| Age | 2.839 | 1.104 | -2.599 | 12.741 *** |

| (2.58) | (2.24) | (3.64) | (2.79) | |

| Number of siblings | 9.572 | -3.455 | 21.426 *** | −11.312 * |

| (7.53) | (5.82) | (7.34) | (6.59) | |

| Smoking | −55.281 ** | 39.069 | -15.025 | −148.254 *** |

| (20.34) | (57.84) | (32.35) | (45.91) | |

| Politics important | −18.907 * | −8.347 | 1.375 | −10.476 |

| (10.23) | (11.49) | (7.77) | (7.65) | |

| Trust in others | 2.902 | −13.040 | 23.770 *** | 27.203 * |

| (12.70) | (17.80) | (6.93) | (15.56) | |

| Income Equality | 10.225 *** | 18.709 *** | −7.284 * | −19.230 *** |

| (3.37) | (5.10) | (3.68) | (6.72) | |

| Hard work | −7.560 | 9.919 | −7.221 ** | −9.436 ** |

| (4.70) | (6.21) | (3.07) | (4.19) | |

| Constant | -35.603 | −245.801 ** | 58.374 | −333.308 *** |

| (70.81) | (102.83) | (79.29) | (82.57) | |

| N | 43 | 45 | 46 | 47 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.138 | 0.143 | 0.206 | 0.203 |

References

- Tullock, G. Efficient Rent Seeking. In Toward a Theory of the Rent-Seeking Society; Buchanan, J., Tollison, R., Tullock, G., Eds.; Texas A & M University Press: College Station, TX, USA, 1980; pp. 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, E.; Nitzan, S.; Rosenberg, J. Rent-seeking for pure public goods. Public Choice 1990, 65, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baye, M.R.; Hoppe, H.C. The strategic equivalence of rent-seeking, innovation, and patent-race games. Games Econ. Behav. 2003, 44, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, G.; Gneezy, U. Price Competition Between Teams. Exp. Econ. 2002, 5, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stub, S.T. Boeing, Airbus in Dogfight Over El Al. Wall Street J. 2012. Available online: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303665904577452612947594688 (accessed on 25 June 2018).

- Fouzder, M. Legal aid tenders: ‘hundreds’ of firms will go under. Law Soc. Gaz. 2015. Available online: https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/law/legal-aid-tenders-hundreds-of-firms-will-go-under/5047915.fullarticle (accessed on 25 June 2018).

- Arkes, H.R.; Blumer, C. The psychology of sunk cost. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1985, 35, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, G. Escalating Commitment in Individual and Group Decision Making: A Prospect Theory Approach. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1993, 54, 430–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savikhin, A.C.; Sheremeta, R.M. Simultaneous decision-making in competitive and cooperative environments. Econ. Inq. 2013, 51, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, S.; Morales, A.J.; Rodero, J. Competition lessens competition: An experimental investigation of simultaneous participation in a public good game and a lottery contest game with shared endowment. Econ. Lett. 2013, 120, 419–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dechenaux, E.; Kovenock, D.; Sheremeta, R. A survey of experimental research on contests, all-pay auctions and tournaments. Exp. Econ. 2015, 18, 609–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, K.A. Strategy and Dynamics in Contests; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Abbink, K.; Brandts, J.; Herrmann, B.; Orzen, H. Intergroup Conflict and Intra-Group Punishment in an Experimental Contest Game. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 420–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnthorsdottir, A.; Rapoport, A. Embedding social dilemmas in intergroup competition reduces free-riding. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2006, 101, 184–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, G.; Kugler, T.; Budescu, D.V.; Selten, R. Repeated price competition between individuals and between teams. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 66, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J.; Orzen, H.; Sefton, M.; Sisak, D. Strategic and Natural Risk in Entrepreneurship: An Experimental Study. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2016, 25, 420–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyck, J.B.V.; Battalio, R.C.; Beil, R.O. Asset Markets as an Equilibrium Selection Mechanism: Coordination Failure, Game Form Auctions, and Tacit Communication. Games Econ. Behav. 1993, 5, 485–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.J.; Ioannou, C.A.; Qi, S. Coordination with Endogenous Contracts: Incentives, Selection, and Strategic Anticipation. Available online: http://myweb.fsu.edu/djcooper/research/selectionandcoordination.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2018).

- Frank, R.H. If Homo Economicus Could Choose His Own Utility Function, Would He Want One with a Conscience? Am. Econ. Rev. 1987, 77, 593–604. [Google Scholar]

- Amann, E.; Yang, C.L. Sophistication and the persistence of cooperation. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1998, 37, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbell, J.; Dawes, R.M. A “Cognitive Miser” Theory of Cooperators Advantage. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1991, 85, 515–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbell, J.M.; Dawes, R.M. Social Welfare, Cooperators’ Advantage, and the Option of Not Playing the Game. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1993, 58, 787–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosenzo, D.; Tufano, F. The Effect of Voluntary Participation on Cooperation. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2017, 142, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garland, H. Throwing good money after bad: The effect of sunk costs on the decision to esculate commitment to an ongoing project. J. Appl. Psychol. 1990, 75, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk. Econometrica 1979, 47, 263–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staw, B.M. The Escalation of Commitment to a Course of Action. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1981, 6, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, D.; Pommerenke, K.; Lukose, R.; Milam, G.; Huberman, B. Searching for the sunk cost fallacy. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 79–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offerman, T.; Potters, J. Does auctioning of entry licences induce collusion? An experimental study. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2006, 73, 769–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.O.; Ackermann, K.A.; Handgraaf, M.J. Measuring social value orientation. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2011, 6, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliet, D.; Parks, C.; Joireman, J. Social Value Orientation and Cooperation in Social Dilemmas: A Meta-Analysis. Group Process. Intergroup Relat. 2009, 12, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, B. The online recruitment system ORSEE 2.0. In A Guide for the Organization of Experiments in Economics; University of Cologne: Cologne, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbacher, U. z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glöckner, A.; Irlenbusch, B.; Kube, S.; Nicklisch, A.; Normann, H.T. Leading with (out) sacrifice? A public-goods experiment with a privileged player. Econ. Inq. 2011, 49, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnthorsdottir, A.; Houser, D.; McCabe, K. Disposition, history and contributions in public goods experiments. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2007, 62, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, R.M.; Walker, J.M. Group Size Effects in Public Goods Provision: The Voluntary Contributions Mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1988, 103, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednar, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, T.X.; Page, S. Behavioral spillovers and cognitive load in multiple games: An experimental study. Games Econ. Behav. 2012, 74, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cason, T.N.; Savikhin, A.C.; Sheremeta, R.M. Behavioral spillovers in coordination games. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2012, 56, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capraro, V. A Model of Human Cooperation in Social Dilemmas. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reuben, E.; Riedl, A. Enforcement of contribution norms in public good games with heterogeneous populations. Games Econ. Behav. 2013, 77, 122–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heap, S.P.H.; Ramalingam, A.; Stoddard, B.V. Endowment inequality in public goods games: A re-examination. Econ. Lett. 2016, 146, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.R.; Mellor, J.M.; Milyo, J. Inequality and public good provision: An experimental analysis. J. Socio Econ. 2008, 37, 1010–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, E.; Croson, R. Income and wealth heterogeneity in the voluntary provision of linear public goods. J. Public Econ. 2006, 90, 935–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, G.E.; Ockenfels, A. ERC: A Theory of Equity, Reciprocity, and Competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcoxon, F. Individual Comparisons by Ranking Methods. Biom. Bull. 1945, 1, 80–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H.B.; Whitney, D.R. On a Test of Whether one of Two Random Variables is Stochastically Larger than the Other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947, 18, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am. J. Psychol. 1904, 15, 72–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, W. Practical Nonparametric Statistics, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist, J.D.; Pischke, J.S. Mostly Harmless Econometrics an Empiricist’s Companion; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, W. Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Tech. Bull. 1994, 3, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, M.M.; Navarrete, C.D.; Van Vugt, M. Evolution and the psychology of intergroup conflict: The male warrior hypothesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2012, 367, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vugt, M.V.; Cremer, D.D.; Janssen, D.P. Gender Differences in Cooperation and Competition: The Male-Warrior Hypothesis. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babcock, L.; Recalde, M.P.; Vesterlund, L.; Weingart, L. Gender Differences in Accepting and Receiving Requests for Tasks with Low Promotability. Am. Econ. Rev. 2017, 107, 714–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.J.; Ecklund, R.C.; Smith, A.L. The relationships among competitiveness, age and ability in distance runners. J. Sport Behav. 1994, 17, 258. [Google Scholar]

- Inglehart, R.; Archivo de Estudios Sociales. World Values Surveys and European Values Surveys, 1981–1984, 1990–1993, and 1995–1997; ICPSR: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Crosetto, P.; Weisel, O.; Winter, F. A flexible z-Tree implementation of the Social Value Orientation Slider Measure (Murphy et al. 2011): Manual; Technical Report, Jena Economic Research Papers; Friedrich-Schiller-University: Jena, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brandts, J.; Riedl, A.; van Winden, F. Competitive rivalry, social disposition, and subjective well-being: An experiment. J. Public Econ. 2009, 93, 1158–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnemans, J.; van Dijk, F.; van Winden, F. On the dynamics of social ties structures in groups. J. Econ. Psychol. 2006, 27, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R.O.; Ackermann, K.A. Social Value Orientation: Theoretical and Measurement Issues in the Study of Social Preferences. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 18, 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stockard, J.; van de Kragt, A.J.C.; Dodge, P.J. Gender Roles and Behavior in Social Dilemmas: Are There Sex Differences in Cooperation and in Its Justification? Soc. Psychol. Q. 1988, 51, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, J.; Kuipers, K.J. A Structural Social Psychological View of Gender Differences in Cooperation. Sex Roles 2009, 61, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.L.; Laibson, D.I.; Scheinkman, J.A.; Soutter, C.L. Measuring Trust. Q. J. Econ. 2000, 115, 811–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovic, P. Smoking: Risk, Perception, and Policy; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Esteve, M.; Urbig, D.; van Witteloostuijn, A.; Boyne, G. Prosocial Behavior and Public Service Motivation. Public Adm. Rev. 2016, 76, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | |

| 2. | Public procurement procedures for legal aid providers in the UK illustrate a related application: Legal firms enter a tendering process for duty provider contracts. While this represents an attractive business for legal enterprises, there is a considerable amount of firms operating without duty work. In 2015, around 200 firms won no contract and currently operate without duty work [6] in press. |

| 3. | |

| 4. | Details are described in Appendix A. |

| 5. | This was called team project in the instructions. |

| 6. | Each player receives 200 tokens in the beginning, of which she can spend 100 tokens for the contest and 100 tokens for the subsequent public good game. We choose this setup with an overall endowment and two separate spending ceilings to put emphasis on the overall wealth effects of the first stage decisions and the fact that the two stages are linked as one game. Furthermore, there exist two separate ceilings, to keep constant the decision space across all players. So although players frequently enter the second stage with different momentary wealth levels, there are no constraints for the individual decision space emanating from the wealth levels. |

| 7. | . The first and the last inequality define the public good game, in which subjects face a trade-off between individual monetary interest and social efficiency. The second inequality makes sure that the winning group encounters a more attractive game. |

| 8. | We have one pair of groups less in the exogenous treatment because of no-shows. Hence, there is in fact one pair of groups from the competition treatment which is not mirrored in an exogenous treatment session. |

| 9. | The software was programmed with “z-Tree” [33]. |

| 10. | Find a copy of the instructions in Section 7.1. |

| 11. | As for the one shot character of the game and the complex nature of the setup, we want to be as certain as possible that our participants understand the game. This is why we employ a trial round with randomly generated contributions and understanding questions. Participants could only proceed when they have answered everything correctly (guessing as strategy can be reasonably excluded). Screenshots will be provided in the supplementary material of this article. |

| 12. | About 16.00 or $18.00 at the time of the experiment. |

| 13. | |

| 14. | As reference, we also present results for ordinary least squares (OLS) in Appendix D. |

| 15. | The analysis in this Subsection employs data from the competition treatment only. |

| 16. | Outcomes stay qualitatively similar when using OLS (Appendix D). The model’s variance inflation factors (VIF’s) are within the usual recommended boundaries, presenting no evidence for multicollinearity. |

| 17. | For details see Appendix A. |

| 18. | Politics important, for example has been generated through the questionnaire using a Likert scale from 1–4, where participants were asked how important they find politics in their life. |

| 19. | For this term, participants answer the following question from the World Values Survey [55]: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” They pick one of the following two answers: “Need to be very careful”. or “Most people can be trusted”. |

| 20. | In Appendix D we present results for equivalent OLS regressions with robust standard errors for intra-group correlation. Results stay qualitatively the same. |

| 21. | We discuss the underlying control variables of Regressions (4) and (6) in an explorative analysis in Appendix E. |

| 22. | While the results of Regressions (1) and (2) might suggest a potential multicollinearity problem, this should only increase the standard errors of the coefficients if they are collinear and have no influence on the actual coefficients. The models’ variance inflation factors (VIF’s), however, reject the possibility of a potential multicollinearity problem. |

| 23. | See Table A4 in Appendix D. |

| 24. | [56] provide a helpful tool for implementation. |

| 25. | Results for corresponding models using OLS regression stay qualitatively identical. |

| 26. | We believe this approach delivers more lucid results here, than interaction terms would. |

| 27. | In a more recent study, Sell and Kuipers [61] examine the gender bias in cooperation levels in the context of a structural social psychological framework. They argue that a large part of variation in gender specific willingness to cooperate can be explained by structural differences and identities of institutional rules and norms. Sell and Kuipers [61] close with the optimistic note that these stereotypical gender roles, which are often perceived as innate, can in fact be overcome and ensuing social dilemmas be solved. |

| 28. | For this term, participants answer the following question from the World Values Survey [55]: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?” They pick one of the following two answers: “Need to be very careful.” or “Most people can be trusted.” |

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|

| First Stage Contribute | ||

| Social value orientation (SVO) | 0.708 ** | 0.514 * |

| (0.29) | (0.27) | |

| Risk parameter | 3.518 | |

| (2.35) | ||

| Female | 21.332 *** | |

| (7.77) | ||

| Age | 4.838 *** | |

| (1.74) | ||

| Number of siblings | −1.966 | |

| (3.15) | ||

| Smoking | 2.763 | |

| (15.35) | ||

| Politics important | −2.552 | |

| (4.19) | ||

| Trust in others | 17.066 ** | |

| (6.84) | ||

| Income Equality | −5.259 ** | |

| (2.09) | ||

| Hard work | −1.242 | |

| (1.93) | ||

| Constant | 12.482 * | −104.908 ** |

| (6.29) | (43.37) | |

| N | 96 | 93 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.008 | 0.072 |

| Win | Lose | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exogenous | 34.3 | 19.5 | 26.9 |

| Competition | 37.2 | 16.3 | 26.8 |

| Overall | 35.8 | 17.8 | 26.8 |

| Variables | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Stage Contribute | ||||

| First stage | 0.481 *** | 0.360 ** | 0.950 *** | 0.912 ** |

| Contribute | (0.16) | (0.17) | (0.35) | (0.37) |

| Group Contribute | 0.253 ** | 0.223 * | 0.317 *** | 0.262 ** |

| Minus Self | (0.11) | (0.12) | (0.11) | (0.12) |

| Social value | 0.986 *** | 0.809 ** | 0.850 ** | 0.721 ** |

| orientation (SVO) | (0.33) | (0.34) | (0.34) | (0.34) |

| Exogenous lose | 14.629 | 16.488 | 53.308 *** | 49.942 ** |

| (11.35) | (11.51) | (16.92) | (19.30) | |

| Exogenous win | 24.567 * | 25.530 ** | 39.158 ** | 44.400 ** |

| (12.74) | (12.02) | (15.79) | (17.82) | |

| Competition win | 31.763 *** | 28.767 ** | 27.690 | 32.699 |

| (11.00) | (12.50) | (17.98) | (20.46) | |

| Exogenous lose | −1.645 *** | −1.419 ** | ||

| × First stage Contr. | (0.50) | (0.56) | ||

| Exogenous win | −0.578 | −0.720 | ||

| × First stage Contr. | (0.40) | (0.44) | ||

| Competition win | −0.044 | −0.282 | ||

| × First stage Contr. | (0.44) | (0.50) | ||

| Constant | −51.175 *** | −127.493 ** | −63.599 *** | −130.816 ** |

| (12.60) | (50.81) | (16.16) | (53.69) | |

| Controls | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| N | 186 | 181 | 186 | 181 |

| Pseudo R-squared | 0.034 | 0.067 | 0.045 | 0.073 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Heine, F.; Sefton, M. To Tender or Not to Tender? Deliberate and Exogenous Sunk Costs in a Public Good Game. Games 2018, 9, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030041

Heine F, Sefton M. To Tender or Not to Tender? Deliberate and Exogenous Sunk Costs in a Public Good Game. Games. 2018; 9(3):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleHeine, Florian, and Martin Sefton. 2018. "To Tender or Not to Tender? Deliberate and Exogenous Sunk Costs in a Public Good Game" Games 9, no. 3: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030041

APA StyleHeine, F., & Sefton, M. (2018). To Tender or Not to Tender? Deliberate and Exogenous Sunk Costs in a Public Good Game. Games, 9(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9030041