Explaining Public Goods Game Contributions with Rational Ability

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Survey

2.2. Public Goods Game

3. Results

Personality Traits

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zelmer, J. Linear Public Goods Experiments: A Meta-Analysis. Exp. Econ. 2003, 6, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Why free ride?: Strategies and learning in public goods experiments. J. Public Econ. 1988, 37, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Cooperation in public-goods experiments: Kindness or confusion? Am. Econ. Rev. 1995, 891–904. [Google Scholar]

- Gächter, S.; Kölle, F.; Quercia, S. Reciprocity and the tragedies of maintaining and providing the commons. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2017, 1, 650–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fosgaard, T.R.; Hansen, L.G.; Wengström, E. Framing and Misperception in Public Good Experiments. Scand. J. Econ. 2017, 119, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semmann, D.; Krambeck, H.-J.; Milinski, M. Volunteering leads to rock–paper–scissors dynamics in a public goods game. Nature 2003, 425, 390–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romaniuc, R.; Dubois, D.; DeAngelo, G.; McCannon, B. Intergroup Solidarity and Local Public Goods Provision: An Experiment; Working Papers; Universitiy of Montpellier: Montpellier, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cinyabuguma, M.; Page, T.; Putterman, L. Cooperation under the threat of expulsion in a public goods experiment. J. Public Econ. 2005, 89, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Gächter, S. Cooperation and Punishment in Public Goods Experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 980–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czap, H.J.; Czap, N.V.; Bonakdarian, E. Walk the Talk? The Effect of Voting and Excludability in Public Goods Experiments. Available online: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/ecri/2010/768546/abs/ (accessed on 8 March 2018).

- John, O.P.; Donahue, E.M.; Kentle, R.L. The Big Five Inventory—Versions 4a and 54; University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- John, O.P.; Naumann, L.P.; Soto, C.J. Paradigm shift to the integrative big five trait taxonomy. In Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2008; pp. 114–158. ISBN 978-1-59385-836-0. [Google Scholar]

- Perugini, M.; Tan, J.H.; Zizzo, D.J. Which is the more predictable gender? Public good contribution and personality. Econ. Issues 2010, 15, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, S.; Thöni, C.; Ruigrok, W. Temporal stability and psychological foundations of cooperation preferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 81, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, S.; Thöni, C.; Ruigrok, W. Personality, personal values and cooperation preferences in public goods games: A longitudinal study. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 50, 810–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzban, R.; Houser, D. Individual differences in cooperation in a circular public goods game. Eur. J. Personal. 2001, 15, S37–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, J. Smart or selfish—When smart guys finish nice. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2016, 64, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benet-Martinez, V.; John, O.P. Los Cinco Grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 75, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Argyle, M. Happiness and cooperation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 1991, 12, 1019–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton, M.C.; Paunonen, S.V.; Helmes, E.; Jackson, D.N. Kin altruism, reciprocal altruism, and the Big Five personality factors. Evol. Hum. Behav. 1998, 19, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsh, J.B.; Peterson, J.B. Extraversion, neuroticism, and the prisoner’s dilemma. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009, 46, 254–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ner, A.; Kong, F.; Putterman, L. Share and share alike? Gender-pairing, personality, and cognitive ability as determinants of giving. J. Econ. Psychol. 2004, 25, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Ner, A.; Kramer, A. Personality and altruism in the dictator game: Relationship to giving to kin, collaborators, competitors, and neutrals. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2011, 51, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SurveyMonkey. Available online: www.surveymonkey.com (accessed on 17 August 2013).

- Pacini, R.; Epstein, S. The relation of rational and experiential information processing styles to personality, basic beliefs, and the ratio-bias phenomenon. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 76, 972–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonderlic, E.F. Wonderlic Personnel Test and Scholastic Level Exam: User’s Manual; Wonderlic and Associates: Northfield, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, C.A.; Laury, S.K. Risk aversion and incentive effects. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1644–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Wheelwright, S.; Hill, J.; Raste, Y.; Plumb, I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: A study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2001, 42, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron-Cohen, S.; Jolliffe, T.; Mortimore, C.; Robertson, M. Another advanced test of theory of mind: Evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1997, 38, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirschauer, N.; Musshoff, O.; Maart-Noelck, S.C.; Gruener, S. Eliciting risk attitudes—How to avoid mean and variance bias in Holt-and-Laury lotteries. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2014, 21, 35–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.S.; Hatton, C.; Craig, F.B.; Bentall, R.P. Persecutory beliefs, attributions and theory of mind: Comparison of patients with paranoid delusions, Asperger’s syndrome and healthy controls. Schizophr. Res. 2004, 69, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golan, O.; Baron-Cohen, S.; Hill, J. The Cambridge Mindreading (CAM) Face-Voice Battery: Testing Complex Emotion Recognition in Adults with and without Asperger Syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2006, 36, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, D. Theory of mind in Asperger’s syndrome, schizophrenia and personality disordered forensic patients. Cognit. Neuropsychiatry 2006, 11, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isaac, R.M.; Walker, J.M.; Williams, A.W. Group size and the voluntary provision of public goods: Experimental evidence utilizing large groups. J. Public Econ. 1994, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladek, R.M.; Bond, M.J.; Phillips, P.A. Age and gender differences in preferences for rational and experiential thinking. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010, 49, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, L.A.; Forster, A.J.; Stiell, I.G.; Carr, L.K.; Brehaut, J.C.; Perry, J.J.; Vaillancourt, C.; Croskerry, P. Experiential and rational decision making: A survey to determine how emergency physicians make clinical decisions. Emerg. Med. J. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujimoto, H.; Park, E.-S. Framing effects and gender differences in voluntary public goods provision experiments. J. Socio-Econ. 2010, 39, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.-S. Warm-glow versus cold-prickle: A further experimental study of framing effects on free-riding. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2000, 43, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H. The Bonferonni and Šidák Corrections for Multiple Comparisons. In Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics; Salkind, N., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein, S.; Pacini, R.; Denes-Raj, V.; Heier, H. Individual differences in intuitive-experiential and analytical-rational thinking styles. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 71, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | In unreported results, we include a series of interaction variables between group size, gender and other control variables. None of these interaction effects were statistically significant and, hence, we do not report these results here. |

| Variable | Median/Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 22/21.5 | 2.07 |

| Group size | 10/11.4 | 2.66 |

| Public Good Outcome | 3.4/3.41 | 0.827 |

| Public Good Contribution | ||

| • for all participants (N = 140) | 0.5/0.502 | 0.392 |

| • for all males (N = 85) | 0.5/0.517 | 0.429 |

| • for all females (N = 55) | 0.5/0.478 | 0.329 |

| • for group size = 8 (N = 32) | 0.5/0.495 | 0.400 |

| • for group size = 10 (N = 40) | 0.5/0.498 | 0.388 |

| • for group size = 12 (N = 24) | 0.64/0.566 | 0.394 |

| • for group size = 14 (N = 28) | 0.45/0.454 | 0.395 |

| • for group size = 16 (N = 16) | 0.5/0.513 | 0.416 |

| Rationality | ||

| • for all participants (N = 140) | 3.3/3.29 | 0.712 |

| • for all males (N = 85) | 3.3/3.198 | 0.755 |

| • for all females (N = 55) | 3.5/3.42 | 0.623 |

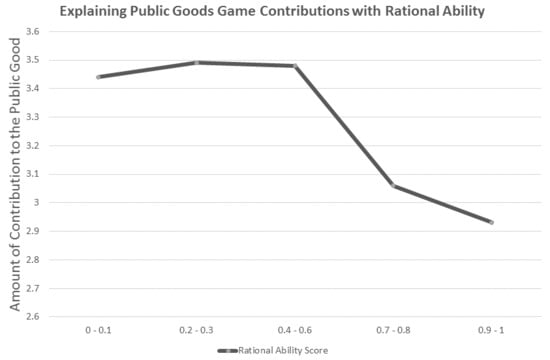

| Rational Ability Score | 0 < x ≤ 2 | 2 < x < 3 | 3 ≤ x < 3.5 | 3.5 ≤ x < 4 | 4 ≤ x | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investment in Public Good | ||||||

| All participants (N = 140) | ||||||

| • N | 11 | 28 | 37 | 38 | 26 | |

| • Mean (S.D.) | 0.85 (0.32) | 0.60 (0.42) | 0.51 (0.36) | 0.42 (0.36) | 0.34 (0.38) | |

| PG Contribution | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rational Ability | −0.155 ** (0.047) | −0.153 ** (0.047) | −0.150 * (0.048) | −0.176 **(0.047) | −0.219 * (0.067) |

| Risk Aversion | −0.001 (0.075) | 0.005 (0.076) | 0.006 (0.078) | 0.047 (0.085) | −0.004 (0.078) |

| Age | 0.037 ** (0.012) | 0.043 ** (0.013) | 0.034 (0.017) | 0.038 * (0.013) | 0.048 ** (0.014) |

| Male | 0.015 (0.061) | 0.038 (0.072) | 0.022 (0.060) | 0.016 (0.069) | |

| Group Size | −0.014 (0.012) | −0.012 (0.014) | −0.009 (0.013) | −0.014 (0.012) | |

| Big 5—Extraversion | 0.016 (0.050) | ||||

| Big 5—Agreeableness | 0.079 (0.059) | ||||

| Big 5—Consciousness | −0.126 (0.065) | ||||

| Big 5—Neuroticism | 0.067 (0.055) | ||||

| Big 5—Openness | −0.060 (0.057) | ||||

| Rational Engagement | 0.089 (0.058) | ||||

| Experiential Ability | 0.014 (0.076) | ||||

| Experiential Engagement | −0.031 (0.079) | ||||

| Wonderlic Score | −0.006 (0.007) | ||||

| Mind in the Eyes Score | −0.007 (0.010) | ||||

| Constant | 0.206 (0.348) | 0.188 (0.352) | 0.132 (0.408) | 0.349 (0.390) | 0.500 (0.507) |

| Control Variables | No | No | College, Major, Years in College | No | No |

| R2 | 0.138 | 0.145 | 0.160 | 0.196 | 0.172 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.119 | 0.114 | 0.088 | 0.133 | 0.108 |

| F | 11.46 *** | 7.712 *** | 4.412 *** | 6.050 *** | 4.010 *** |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lang, H.; DeAngelo, G.; Bongard, M. Explaining Public Goods Game Contributions with Rational Ability. Games 2018, 9, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020036

Lang H, DeAngelo G, Bongard M. Explaining Public Goods Game Contributions with Rational Ability. Games. 2018; 9(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleLang, Hannes, Gregory DeAngelo, and Michelle Bongard. 2018. "Explaining Public Goods Game Contributions with Rational Ability" Games 9, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020036

APA StyleLang, H., DeAngelo, G., & Bongard, M. (2018). Explaining Public Goods Game Contributions with Rational Ability. Games, 9(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/g9020036