Promoting Residential Recycling: An Alternative Policy Based on a Recycling Reward System

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Model

3. Signaling Game

3.1. Equilibrium

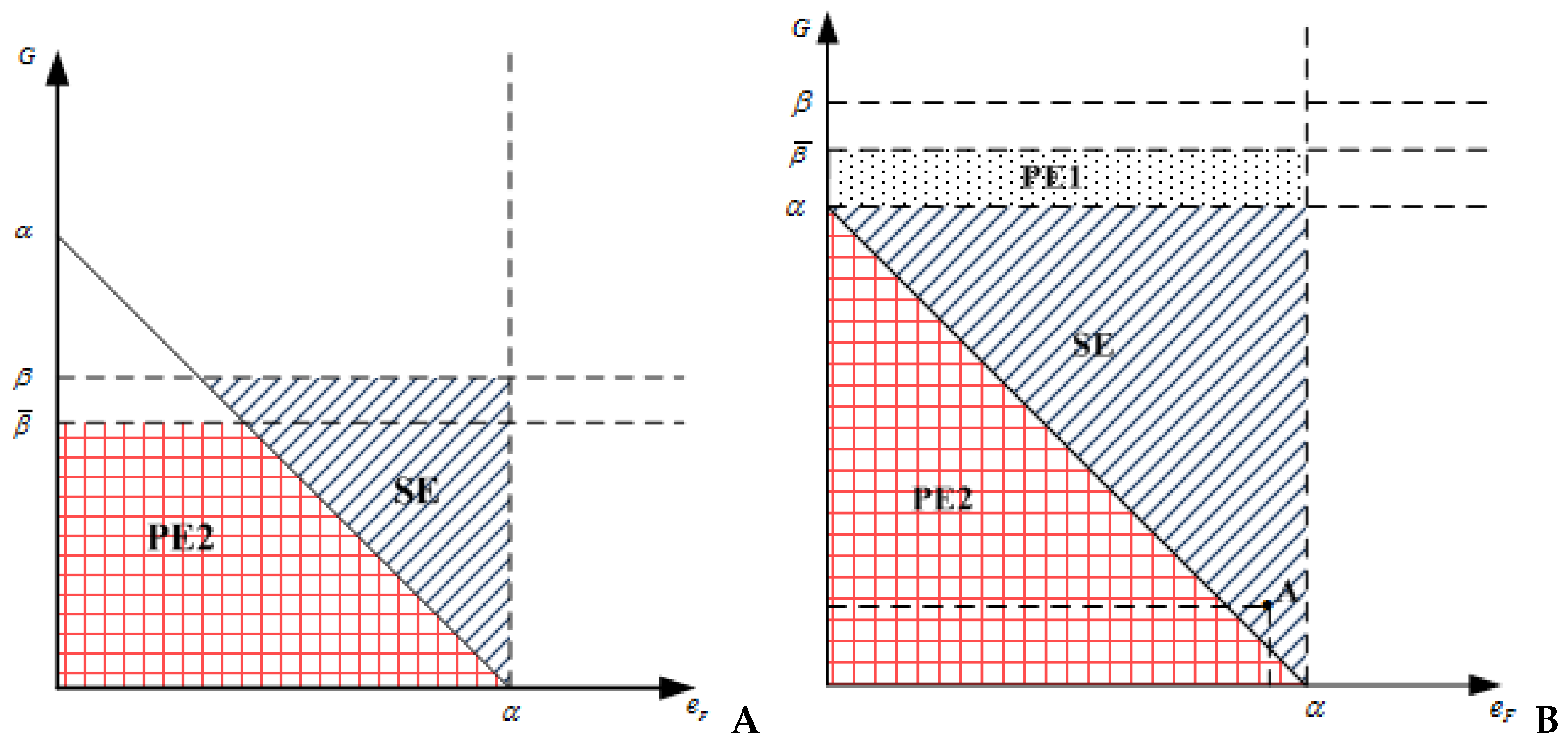

3.1.1. Separating Equilibrium

- The friendly resident commits and the resident does not commit if .

- The administrator responds by establishing the RRS when he observes commitment, given that his posterior beliefs are and , and , where . However, he does not establish the RRS upon observing no commitment for all parameter values.

3.1.2. SE Versus Status Quo

3.1.3. Pooling Equilibrium

- (1)

- The resident commits regardless of her type if .

- (2)

- The administrator responds by establishing the RRS when he observes commitment, given that his posterior beliefs are , and , where . However, he does not establish the RRS upon observing no commitment for all parameter values.

- Both types of residents do not commit if .

- The administrator does not establish the RRS if he observes no commitment, given that his posterior belief is , and establishes it otherwise if .

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Equilibrium Conditions

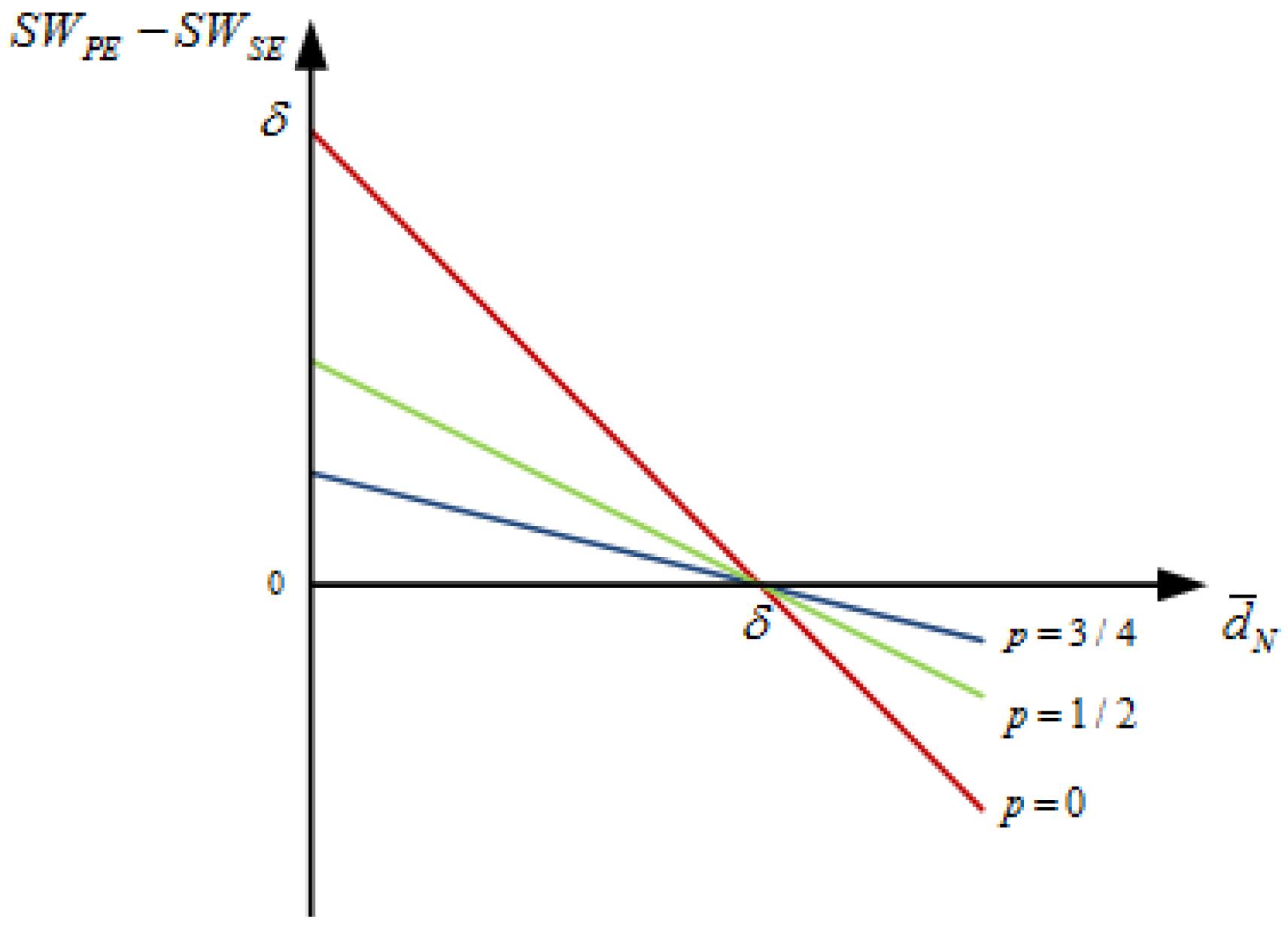

4.2. Comparison between SE and PE

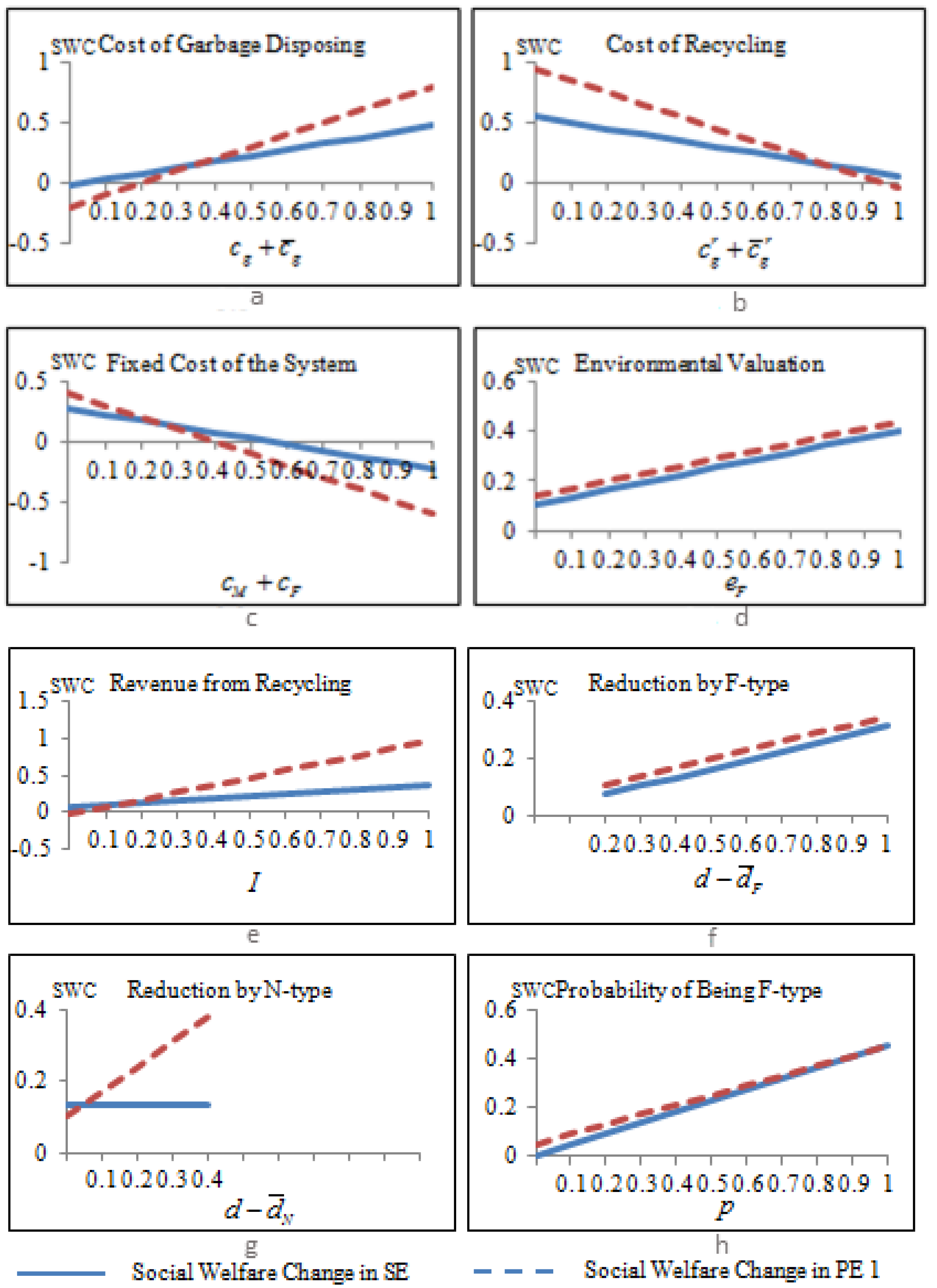

4.3. Simulation

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Proof of Proposition 1

Appendix A.2. Proof of Proposition 2

Appendix A.3. Corollary 1

Appendix A.4. Proof of Proposition 3

- If (A7) holds, the administrator’s optimal strategy is to establish the RRS when the resident commits. Under this circumstance, the resident does not have the incentive to deviate if and only ifNote that this condition is less restrictive for the friendly resident since her payoff under establishment of the RRS is strictly higher than the neutral type resident. For this reason, no resident deviates if . Therefore, the condition in which both types of residents commit, and the administrator establishes the RRS, can be sustained as a pooling equilibrium if inequality (A7) holds and .Rearranging the inequality,

- If inequality (A7) does not hold, the administrator’s optimal strategy is to not establish the RRS when the resident commits. Therefore, the resident has no incentive to commit since . This contradicts with the strategy in which both types of residents commit. Therefore, if (A7) does not hold, the PE in which both types of residents commit cannot be supported.

Appendix A.5. Proof of Proposition 4

- If inequality (A9) holds, the administrator establishes the RRS upon observing that the resident commits. Therefore, the resident deviates from no commitment if her payoff, given the administrator establishes the RRS, is larger than the payoff under the current system. Note that the deviation incentive is more likely for the friendly type resident. Hence, the resident does not deviate if

- 2.

- If (A9) does not hold, the administrator’s participation constraint is not achieved whether the resident commits or not, and he does not establish the RRS. Under this condition, the resident does not have incentive to deviate because . Therefore, the case in which both types do not commit and the administrator does not establish the system can be sustained as a PE.

Appendix A.6. Proof of Lemma 2

- 1.Furthermore, producing a soda can from recycling saves 95 percent energy more than it does to create one from virgin materials. Specifically, the Department of Environmental Conservation [10] reports that recycling one aluminum can could save 0.4 kWh electricity. Despite the fact U.S. consumers use over 80 billion aluminum soda cans every year, only about half of them are recycled.

- 2.Club goods are considered a subtype of public goods. They are excludable but non-rivalrous in consumption. Alternatively, the reward system could also allow for private goods.

- 3.The assessment of residents’ recycling preferences is difficult and often costly for the administrator. Guy and Rogers [11] found that individuals’ attachment to the community affects their attitudes toward recycling. Blaine et al. [12] argue that older individuals who live in rural settings are more likely to recycle.

- 4.The time structure represents the case in which an uninformed local government develops an initiative to infer the median voter’s preference on recycling. Residents decide whether or not to commit to the initiative, and after it is approved or defeated, the local government decides whether to implement the recycling system. Several states in the U.S. follow this time structure, for instance, the Arizona Establishing Waste Reduction, Recycling and Management Plan, Proposition 202 (1990), the Maine Recycling and Solid Waste Landfill Clean Up and Closures, Question 6 (1991), or the Massachusetts Recyclable Packaging Initiative, Question 3 (1992).

- 5.Folz [13] empirically shows that communities that encouraged participation in recycling through education and dissemination of public information were successful in increasing the number of participants in recycling.

- 6.Several cities in the U.S. offer this service. For example, Austin, Texas provides a weekly curbside recyclables pick-up service, and Seattle, Washington provides the same service monthly. Processing procedure and fees vary by local governments [22].

- 7.For example, until 2011, five states (California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine and Oregon) had enacted bottle deposit laws for plastic water bottles.

- 8.In the sequential move game, the resident acts as a leader while the administrator acts as a follower. This setting allows the administration to infer some information from the resident’s decision.

- 9.This valuation can be rationalized by individual’s warm glow of recycling, social norms, or belief of benefits from recycling, as suggested by Viscusi et al. [18].

- 10.The Philadelphia Recycling Rewards program promotes recycling by providing rewards points to residents who correctly recycle. In this program, members use the rewards points to get local deals.

- 11.The per-unit cost of recycling for residents is larger or equal to the per-unit cost of garbage disposing because recycling requires extra handling of the waste such as sorting into different categories, as shown by Halvorson [17].

- 12.In a different setting, the administrator could recycle a certain percentage of the garbage under the current system. However, the existence of equilibria is robust to that context, and the qualitative results remain unaffected.

- 13.Since a friendly resident cares more about the environmental damage, under the same conditions, her behavior is more beneficial to the environment.

- 14.For instance, the establishment of the RRS requires an investment in recycling containers and pick-up vehicles.

- 15.For example, the EPA in 2013 developed a study about the benefits of recycling. The study argues that: recycling helps create jobs, reduces the need for new landfills, saves energy, supplies valuable raw materials to industry, and adds significantly to the U.S. economy.”

- 16.Note that neither type of resident recycles under PE2. Thus, it does not yield different social welfare.

- 17.The simulation results are robust under different parameter values and can be provided by the authors upon request.

- 18.Because , we only present Figure 3f,g under the parameter values that satisfy this condition.

References

- Stern, N. Climate. Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change. N. Engl. J. Public Policy 2007, 21, 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, K.; Walls, M. Optimal Policies for Solid Waste Disposal: Taxes, Subsidies, and Standards. J. Public Econ. 1997, 65, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKibbin, W.J.; Wilcoxen, P. The Role of Economics in Climate Change Policy. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002, 16, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillingham, K.; Newell, R.; Pizer, W. Modeling Endogenous Technological Change for Climate Policy Analysis. Energy Econ. 2008, 30, 2734–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.; Newell, R. Environmental and Technology Policies for Climate Mitigation. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2008, 55, 142–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, H.; Donder, P.D.; Gahvari, F. Political Competition within and between Parties: An Application to Environmental Policy. J. Public Econ. 2008, 92, 532–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N. Capitalism vs. the Climate. 9 November 2011. Available online: https://www.thenation.com/article/capitalism-vs-climate/ (accessed on 15 August 2016).

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emission through Recycling and Composting; EPA 910-R-11-003; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Communicating the Benefits of Recycling. 2013. Available online: http://www.epa.gov/osw/conserve/tools/localgov/benefits/ (accessed on 15 August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environmental Conservation. 2013. Available online: http://www.dec.ny.gov/chemical/44787.html (accessed on 15 August 2016).

- Guy, S.M.; Rogers, D.L. Community surveys: Measuring citizens’ attitudes toward sustainability. J. Ext. 1999, 37, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Blaine, T.W.; Mascarella, K.D.; Davis, D.N. An Examination of Rural Recycling Drop-Off Participation. J. Ext. 2001, 39, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Folz, D.H. Recycling Program Design, Management, and Participation: A National Survey of Municipal Experience. Public Adm. Rev. 1991, 51, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Adams, R.M.; Love, H.A. An Economic Analysis of Resident Recycling of Solid Waste: The Case of Portland, Oregon. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1993, 25, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiller, K.H.; Jakus, P.M.; Park, W.M. Resident Willingness to Pay for Dropoff Recycling. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 1997, 22, 310–320. [Google Scholar]

- Bruvoll, A. Factors Influencing Solid Waste Generation and Management. J. Solid Waste Technol. Manag. 2001, 27, 156–162. [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen, B. Effects of Norms and Opportunity Costs of Time on Resident Recycling. Land Econ. 2008, 84, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscusi, W.K.; Huber, J.; Bell, J. Alternative Policies to Increase Recycling of Plastic Water Bottles in the United States. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 2012, 6, 190–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, I.; Missios, P. Recycling and Waste Diversion Effectiveness: Evidence from Canada. Environmental and Resource Economics. Eur. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2005, 30, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fullerton, D.; Kinnaman, T.C. Resident Responses to Pricing Garbage by the Bag. Am. Econ. Rev. 1996, 86, 971–984. [Google Scholar]

- Kinnaman, T.C.; Fullerton, D. Garbage and Recycling with Endogenous Local Policy. J. Urban Econ. 2000, 48, 419–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Waste Prevention, Recycling, and Composting Options: Lessons from 30 US Communities. 2013. Available online: http://www.epa.gov/waste/conserve/downloads/recy-com/index.html (accessed on 15 August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Aadland, D.; Caplan, A.J. Willingness to Pay for Curbside Recycling with Detection and Mitigation of Hypothetical Bias. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2003, 85, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aadland, D.; Caplan, A.J. Curbside Recycling: Waste Resource or Waste of Resources? J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2006, 25, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koford, B.C.; Blomquist, G.C.; Hardesty, D.M.; Troske, K.R. Estimating Consumer Willingness to Supply and Willingness to Pay for Curbside Recycling. Land Econ. 2012, 88, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashenmiller, B. Cash Recycling, Waste Disposal Costs, and the Incomes of the Working Poor: Evidence from California. Land Econ. 2009, 85, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viscusi, W.K.; Huber, J.; Bell, J. Promoting Recycling: Private Values, Social Norms, and Economic Incentives. Am. Econ. Rev. Pap. Proc. 2011, 101, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D.; Widmar, R. Motivations and Barriers to Recycling: Toward A Strategy for Public Education. J. Environ. Educ. 1990, 27, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoni, J. Giving with Impure Altruism: Applications to Charity and Ricardian Equivalence. J. Political Economy 1989, 97, 1447–1458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palfrey, T.R.; Prisbrey, J.E. Anomalous Behavior in Public Goods Experiments: How Much and Why? Am. Econ. Rev. 1997, 87, 829–846. [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Community Facility Grants. United States Department of Agriculture, 2013. Available online: http://www.rurdev.usda.gov/HAD-CF_Grants.html (accessed on 15 August 2016). [Google Scholar]

- Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (Ohio EPA). Ohio EPA Awards 18 Community Recycling Grants. Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, 2013. Available online: http://www.epa.state.oh.us/ news/onlinenewsroom/newsbycategory/tabid/5980/vw/1/itemid/314/ohio-epa-awards-18-community-recycling-grants.aspx (accessed on 15 August 2016).

- Cho, I.; Kreps, D. Signaling Games and Stable Equilibrium. Q. J. Econ. 1987, 102, 179–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germani, A.; Pergolizzi, A.; Reganati, F. Law Enforcement and Illegal Trafficking of waste: Evidence from Italy. Econ. Bull. 2015, 35, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | I | d | p | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, T.; Espínola-Arredondo, A.; McCluskey, J.J. Promoting Residential Recycling: An Alternative Policy Based on a Recycling Reward System. Games 2016, 7, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7030021

Li T, Espínola-Arredondo A, McCluskey JJ. Promoting Residential Recycling: An Alternative Policy Based on a Recycling Reward System. Games. 2016; 7(3):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7030021

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Tongzhe, Ana Espínola-Arredondo, and Jill J. McCluskey. 2016. "Promoting Residential Recycling: An Alternative Policy Based on a Recycling Reward System" Games 7, no. 3: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7030021

APA StyleLi, T., Espínola-Arredondo, A., & McCluskey, J. J. (2016). Promoting Residential Recycling: An Alternative Policy Based on a Recycling Reward System. Games, 7(3), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7030021