Partner Selection and the Division of Surplus: Evidence from Ultimatum and Dictator Experiments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Literature

3. Design, Procedure, Methodology and Hypotheses

3.1. Procedure

| Session/Condition | Number of Proposer Subjects | Number of Recipient Subjects | Number of Rounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| UB | 16 | 16 | 6 |

| DB | 16 | 16 | 6 |

| US | 17 | 17 | 6 |

| DS | 18 | 18 | 6 |

| UC | 60 | 30 | 4 |

| DC | 50 | 25 | 5 |

3.2. Empirical Methodology

3.3. Hypotheses

4. Results

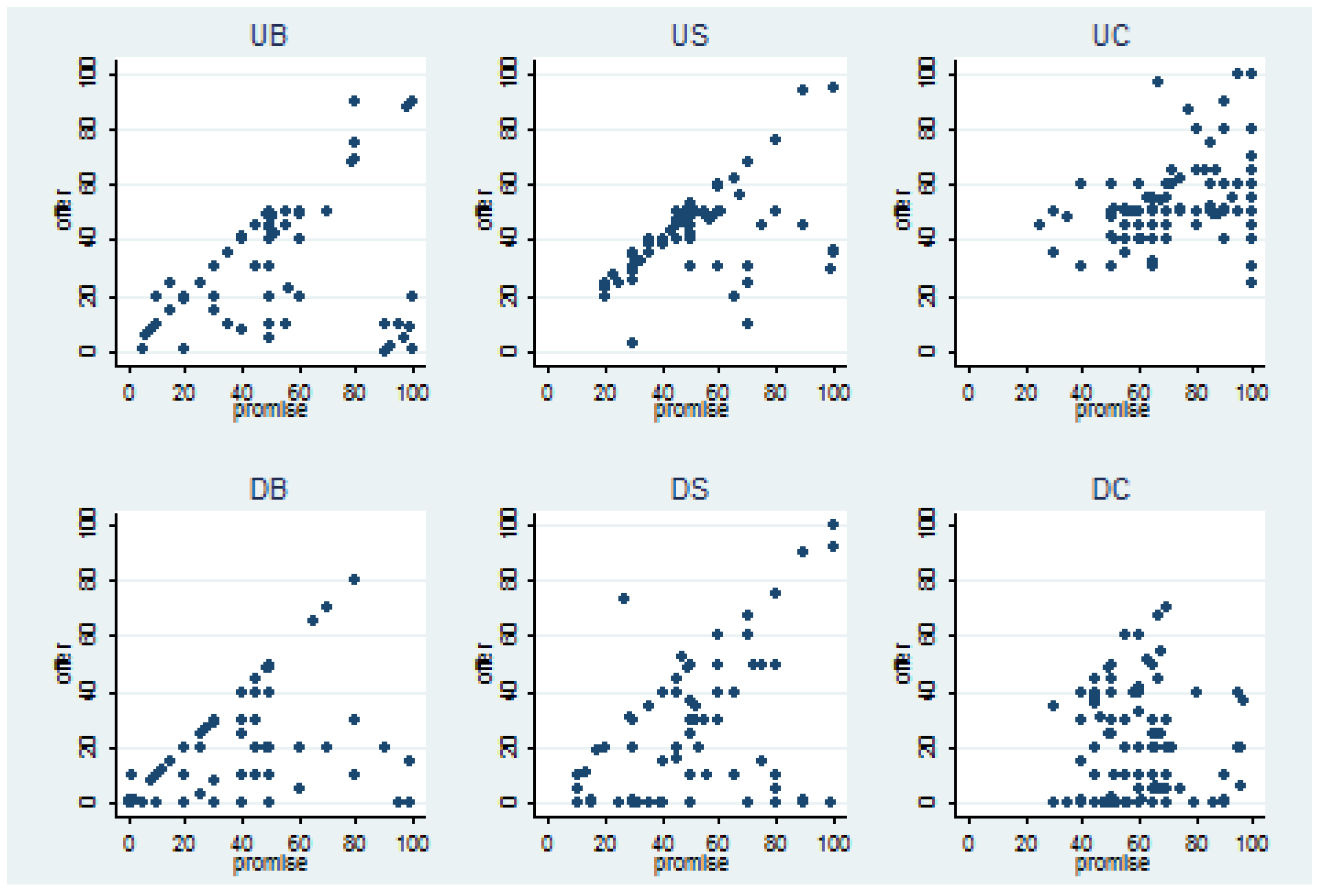

4.1. Promises, Offers and Credibility

| Treatment | Mean Offer | Mean Promise |

|---|---|---|

| UB | 35.7 (96) | 50.3 (96) |

| US † | 42.9 (42.1) (100) | 50 (102) |

| UC | 52.6 (120) | 68.9 (240) |

| DB | 16.5 (96) | 31.1 (96) |

| DS ** | 20.8 (19.5) (101) | 51.4 (108) |

| DC | 18.4 (125) | 60.1 (250) |

| Variable | Dep. Var. = Offer |

|---|---|

| promise | 0.27*** (0.08) |

| UB | 14.55*** (4.85) |

| DS | −1.09 (5.58) |

| US | 21.92*** (4.33) |

| DC | −5.88 (5.35) |

| UC | 25.02*** (6.16) |

| constant | 3.07 (3.19) |

| R2 | 0.44 |

| No. of obs. | 638 |

| Comparison | Ultimatum | Comparison | Ultimatum vs. Dictator |

|---|---|---|---|

| US vs. UB | Promise (US) ≈ Promise (UB) † Offer (US) > Offer (UB) * | US vs. DS | Promise (US) ≈ Promise (DS) Offer (US) > Offer (DS) *** |

| UC vs. UB | Promise (UC) > Promise (UB) *** Offer (UC) > Offer (UB) * | UC vs. DC | Promise (UC) > Promise (DC) *** Offer (UC) > Offer (DC) *** |

| UC vs. US | Promise (UC) > Promise (US) *** Offer (UC) ≈ Offer (US) | UB vs. DB | Promise (UB) > Promise (DB) *** Offer (UB) > Offer (DB) *** |

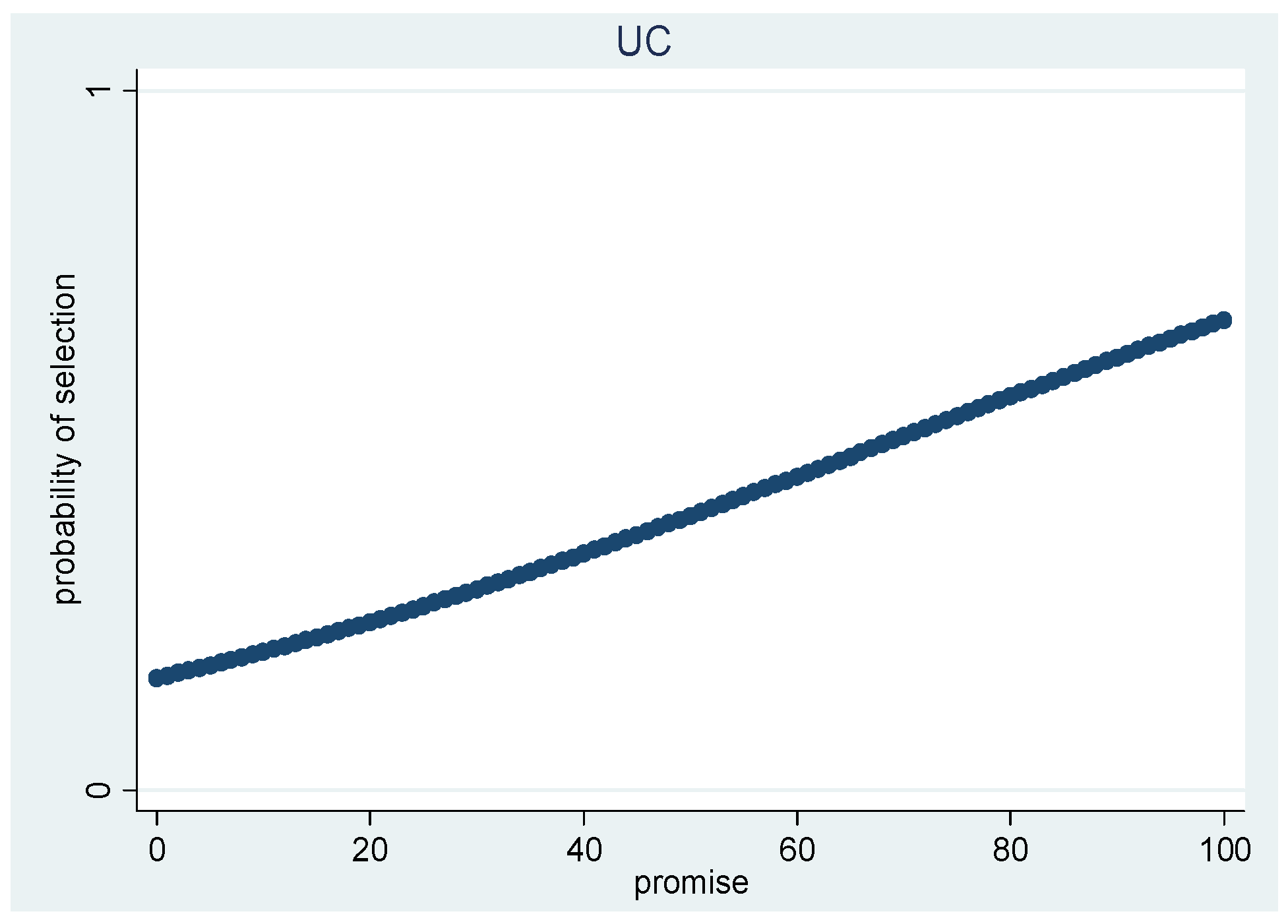

4.2. Credulity

| Ultimatum | Dictator | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Selection | 50.4 (100) | 29 (2) | -- | 50.5 (101) | 64.7 (7) | -- |

| Competition | 73.1 (120) | 64.7 (120) | 0.71 (111) | 58 (125) | 62.1 (125) | 0.41 (119) |

| UC (Linear) | DS (Linear) | DC (Cubic) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| constant | −1.16 *** (0.42) | 2.28 *** (0.75) | −7.55 *** (2.57) |

| promise | 0.01 *** (0.005) | −0.02 * (0.009) | 0.40 *** (0.14) |

| Promise2 | -- | −0.006 *** (0.002) | |

| Promise3 | -- | 0.00003 *** (0.00001) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| No. of obs. | 240 | 90 | 250 |

4.3. Offer Rejection

| UB | US | UC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| offer | 0.05 *** (0.01) | 0.08 ** (0.03) | 0.22 *** (0.05) |

| promise | −0.002 (0.004) | −0.02 ** (0.009) | −0.04 *** (0.01) |

| promise refused | -- | -- | 0.03 ** (0.01) |

| constant | 0.06 (0.67) | 0.32 (0.94) | −7.57 *** (2.32) |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.39 |

| No. of obs. | 96 | 68 | 120 |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A: Instructions

Instruction for DB

Instruction for UB

Instruction for DS

Instruction for US

Instruction for DC

Instruction for UC

Appendix B: Response Sheets

Response Sheet for DB

Response Sheet for UB

Response Sheet for DS

Response Sheet for US

Response Sheet for DC

Response Sheet for UC

References

- Hoffman, E.; McCabe, K.; Shachat, K.; Smith, V. Preferences, Property Right and Anonymity in Bargaining Games. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 7, 346–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, N.; Veszteg, R. Demonstration of Power: Experimental Results on Bilateral Bargaining. J. Econ. Psychol. 2011, 32, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, J.; Binmore, K.; Samuelson, L. Learning to be Imperfect: The Ultimatum Game. Games Econ. Behav. 1995, 8, 56–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, A.; Prasnikar, V.; Okuno-Fujiwara, M.; Zamir, S. Bargaining and Market Behavior in Jerusalem, Ljubljana, Pittsburgh and Tokyo: An Experimental Study. Am. Econ. Rev. 1991, 81, 1068–1095. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, C. Inequity Aversion and Advantage Seeking with Asymmetric Competition. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2013, 86, 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochet, O.; Putterman, L. Not Just Babble: A Voluntary Contribution Experiment with Iterative Numerical Messages. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2009, 53, 309–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellingsen, T.; Johannesson, M. Promises, Threats and Fairness. Econ. J. 2004, 114, 397–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanberg, C. Why Do People Keep Their Promises? An Experimental Test of Two Explanations. Econometrica 2008, 76, 1467–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Tullock, G. Non-Prisoner’s Dilemma. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1999, 39, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coricelli, G.; Fehr, D.; Fellner, G. Partner Selection in Public Goods Experiments. J. Confl. Resolut. 2004, 48, 356–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandts, J.; Cooper, D.; Weber, R. Legitimacy, Communication and Leadership in the Turnaround Game. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 2627–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulleck, U.; Kerschbamer, R.; Sutter, M. The Economics of Credence Goods: An Experiment on the Role of Liability, Verifiability, Reputation, and Competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 526–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.; Kerschbamer, R.; Qiu, J.; Sutter, M. Shaping Beliefs in Experimental Markets for Expert Services: Guilt Aversion and the Impact of Promises and Money-Burning Options. Games Econ. Behav. 2013, 81, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goeree, J.; Zhang, J. Communication and Competition. Exp. Econ. 2014, 17, 421–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, R.; Horowitz, J.; Savin, N.; Sefton, M. Fairness in Simple Bargaining Experiments. Games Econ. Behav. 1994, 6, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güth, W.; Schmittberger, R.; Schwarze, B. An Experimental Analysis of Ultimatum Bargaining. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1982, 3, 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heston, A.; Summers, R.; Aten, B. Penn World Table Version 7.0.; Center for International Comparisons of Production, Income and Prices, University of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bearden, J. Ultimatum Bargaining Experiments: The State of the Art. Available online: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=626183 (accessed on 14 January 2016).

- Oosterbeek, H.; Sloof, R.; van de Kuilen, G. Cultural Differences in Ultimatum Game Experiments: Evidence from a Meta-Analysis. Exp. Econ. 2004, 7, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C. Dictator Games: A Meta Study. Exp. Econ. 2011, 14, 538–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C.; Thaler, R. Anomalies: Ultimatums, Dictators and Manners. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D. Regret in Decision Making under Uncertainty. Oper. Res. 1982, 30, 961–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomes, G.; Sugden, R. Regret Theory: An Alternative Theory of Rational Choice under Uncertainty. Econ. J. 1982, 92, 805–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, J. Communication, the Development of Trust, and Cooperative Behavior. Hum. Relat. 1959, 12, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1This suggests that recipients should select higher promises with greater likelihood, i.e., be credulous. We indeed found such a relationship in the competitive treatment but not in the non-competitive treatment, where the paucity of refusals prevented us from estimating a selection function.

- 3(It is additionally affiliated to the limited research on how choices in promise-communication conditions depend on the presence of punishment options: see, for example, Bochet and Putterman [6], who examine public goods problems. No paper we are aware of in this strand examines bargaining problems.)

- 4Although the game used by Ellingsen and Johannesson [7] is a trust game extended to include an ultimatum game element.

- 5Goeree and Zhang [14] find, in their communication treatments (2CNDR, 2CWDR and 3CWDR), that introducing competition, where the principal faces two agents, rather than one, lowers employment, efficiency and credibility of agent choice (see Figures 2 and 3, and Tables 2 and 3).

- 6The term promise was given semantic focus because promises are distinct and familiar. Additionally, they seem to be somewhat special: evidence suggests that if free-form communication is allowed, messages regularly get coded explicitly as promises (see, for example, Ellingsen and Johanesson [7]).

- 7Instructions and response sheets can respectively be found in Appendix A and Appendix B.

- 8The purchasing power parity exchange rate between the Indian Rupee and the US Dollar for 2009 was 15 rupees to a dollar according to the Penn World Tables (Heston, Summers and Aten [17]).

- 9Every proposer subject was matched to a single recipient subject.

- 10Specifically, mean offers in UB is greater than that in DB (F-test, p-value = 0.0002), mean offers in US is greater than that in DS (F-test, p-value = 0.0000) and mean offers in UC is greater than mean offers in DC (F-test, p-value = 0.0000).

- 11Why did credibility emerge in DB? One possibility is that the absolute power enjoyed by proposers in this condition paradoxically led to a manifestation of the preference for truth-telling, as in Vanberg [8], and thereby caused them to issue offers consonant with promises made, even if it did not actually lead to increased offers.

- 12Selectors in UC faced equal promises in 7.5 percent of cases while selectors in DC faced equal promises in 4.8 percent of cases.

- 13In the DS regression, 18 observations corresponding to those from round 1 were dropped as they predicted selection perfectly.

- 14The number of observations was 196, 216 and 220 for comparisons UB vs. US, UB vs. UC and US vs. UC respectively.

- 15One offer equaled 0 and was rejected.

- 16In the US, regression of 32 observations corresponding to those from rounds 1 and 4 were dropped as they predicted acceptance perfectly.

- 17We also ran probit regressions where we regressed offer on the gap between offer and promise (i.e., offer–promise). The results from these regressions (not reported here) are in line with those in Table 7 confirming that the probability of acceptance of an offer is positively related to the gap between offer and promise, so, for example, if promise is higher than the eventual offer, then the gap is negative and the probability of acceptance becomes lower.

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Banerjee, P.; Chakravarty, S.; Ghosh, S. Partner Selection and the Division of Surplus: Evidence from Ultimatum and Dictator Experiments. Games 2016, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7010003

Banerjee P, Chakravarty S, Ghosh S. Partner Selection and the Division of Surplus: Evidence from Ultimatum and Dictator Experiments. Games. 2016; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleBanerjee, Priyodorshi, Sujoy Chakravarty, and Sanmitra Ghosh. 2016. "Partner Selection and the Division of Surplus: Evidence from Ultimatum and Dictator Experiments" Games 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7010003

APA StyleBanerjee, P., Chakravarty, S., & Ghosh, S. (2016). Partner Selection and the Division of Surplus: Evidence from Ultimatum and Dictator Experiments. Games, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/g7010003