Mobility Comparisons: Theoretical Definitions and People’s Perceptions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mobility Comparisons

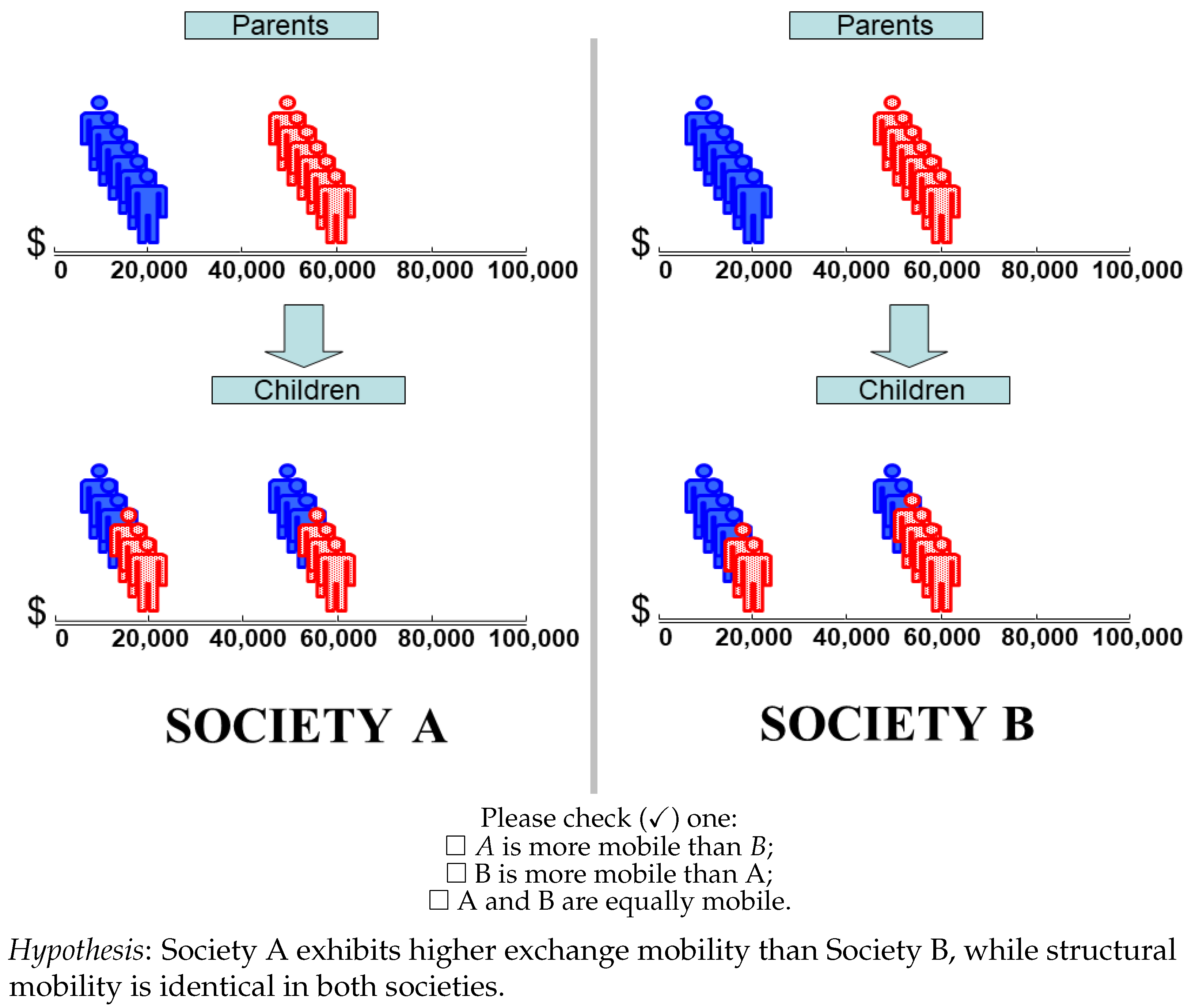

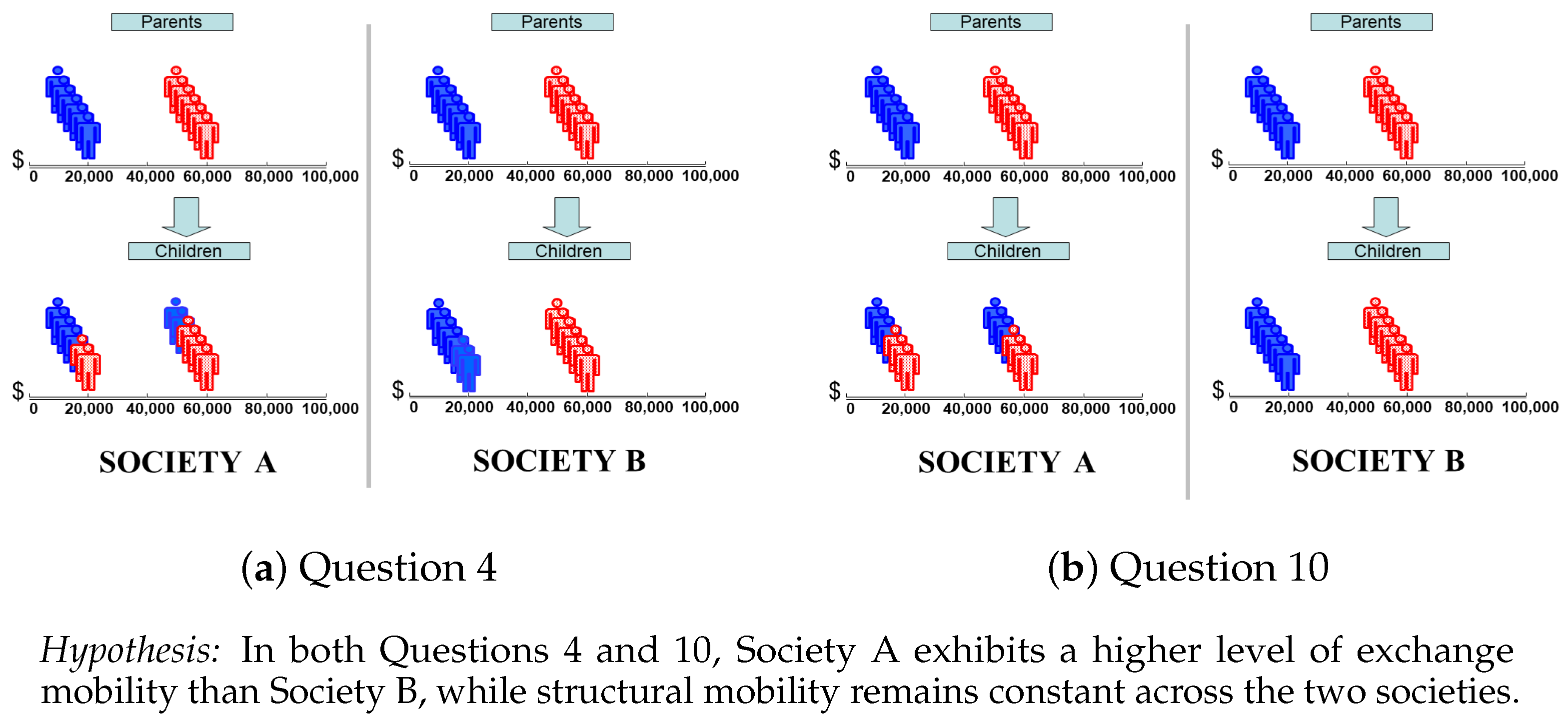

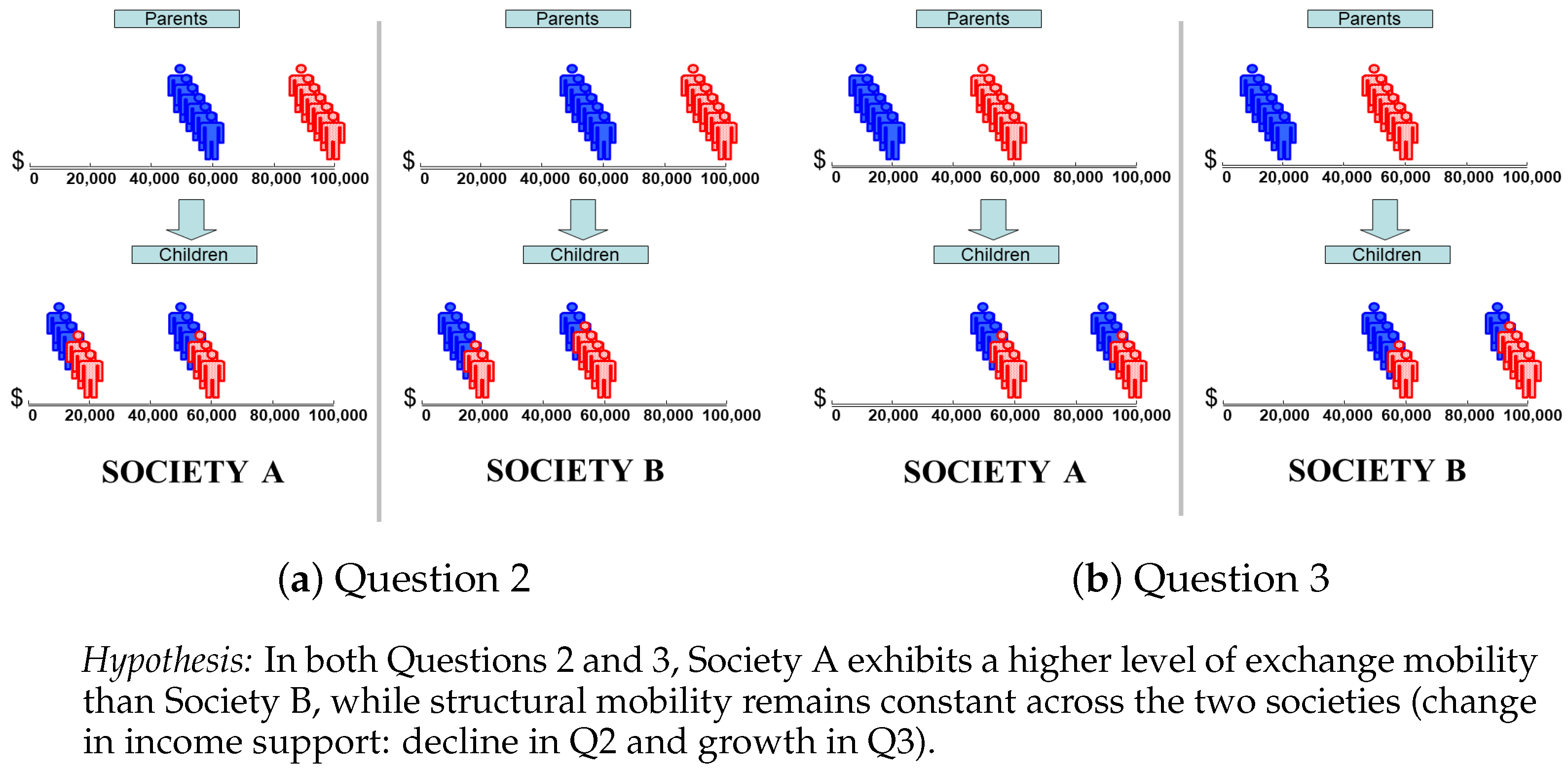

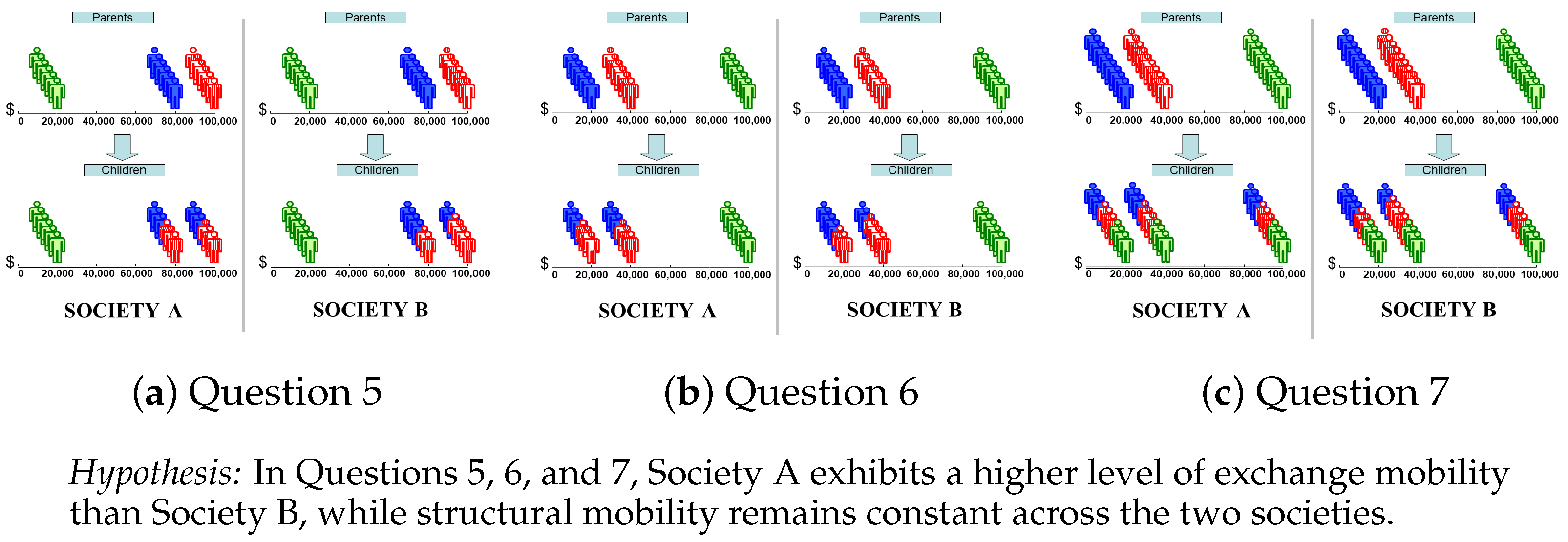

3. The Questionnaire Experiment

3.1. The Questionnaire

3.2. The Sample

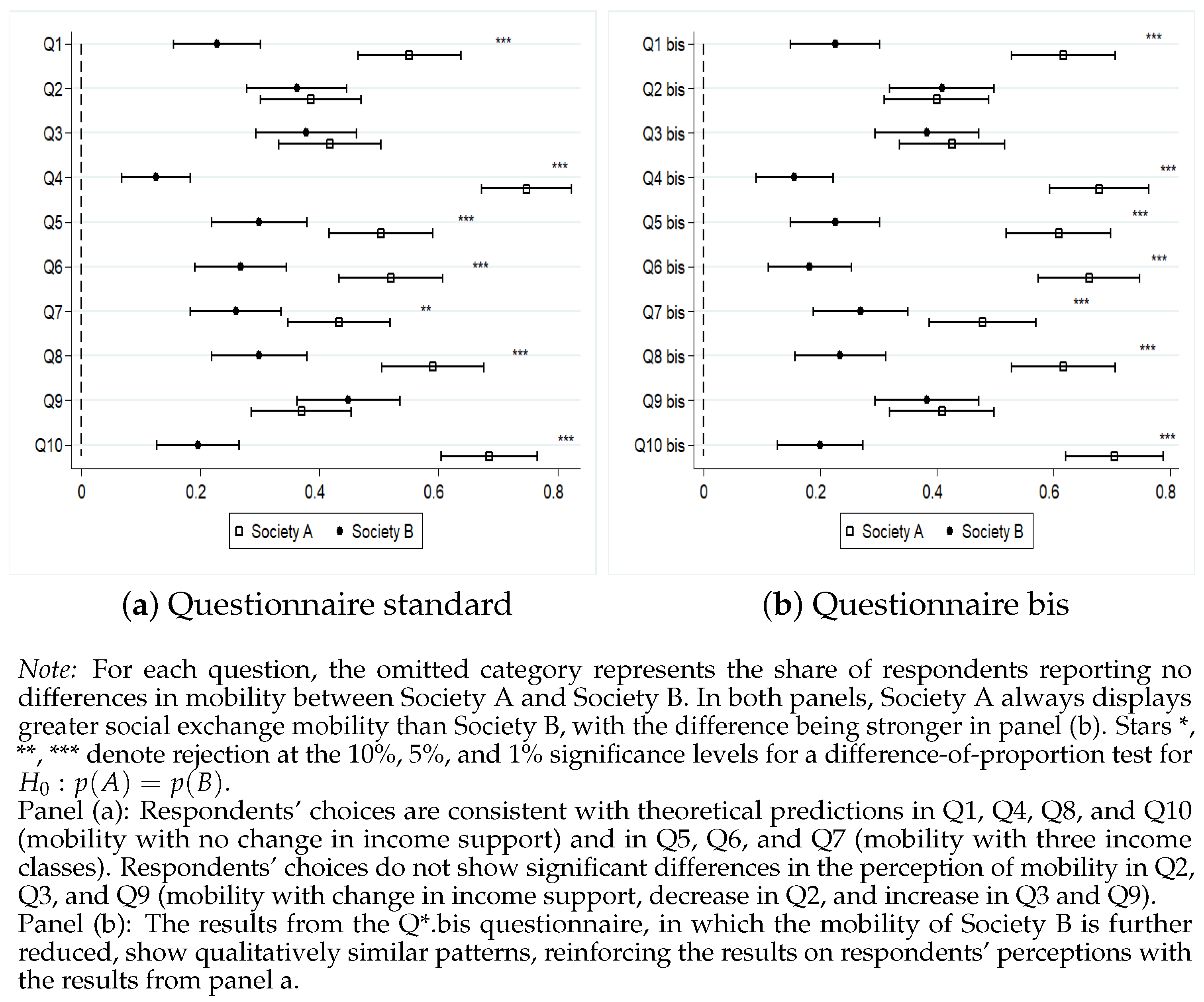

4. Results

5. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Instructions

Appendix A.2. Questions Q1bis–Q7bis

| 1 | Some recent studies have focused on combining evaluations of structural and exchange mobility. Ray and Genicot (2023) analyse the conditions under which economic growth provides greater benefits to individuals who are relatively worse off than to those who are better off, and call this condition upward mobility. In a similar vein, Van de gaer and Palmisano (2021) studied the conditions for positive welfare gains from economic development, dividing them into growth, mobility, and fluctuation aversion effects. Here, we are only concerned with the measurement of mobility, not its valuation from a welfare perspective. (For a discussion of the issues involved in assessing multidimensional well-being; see Decancq et al., 2015). |

| 2 | Dardanoni et al. (2012) provides empirical justification for monotonicity, describing it as a “fact of life”, as monotone transition matrices characterize most observed mobility processes. Theoretical properties of monotone mobility matrices are discussed in Dardanoni (1995). |

| 3 | See Bartolucci et al. (2001) for statistical inference on this ordering. |

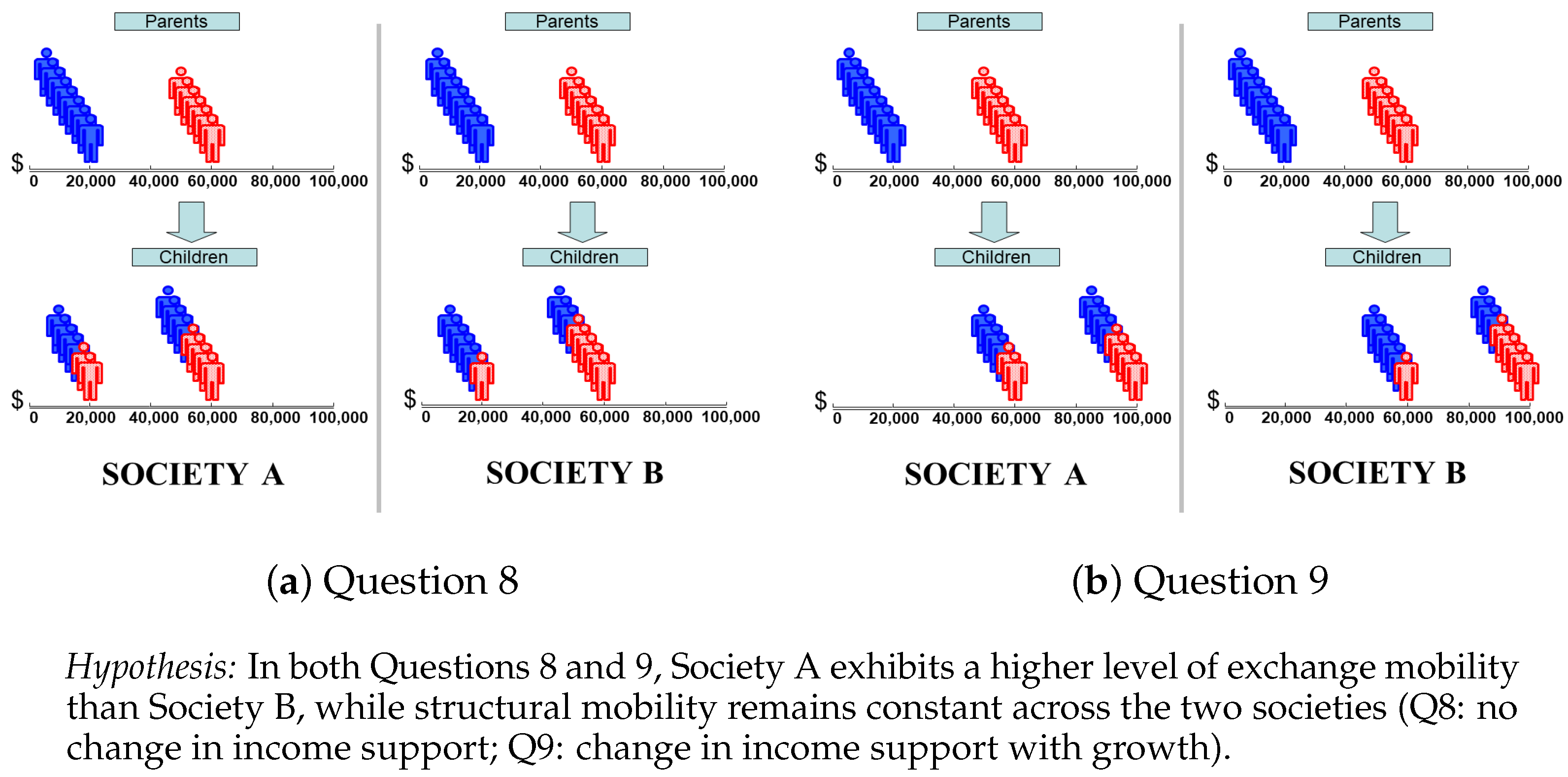

| 4 | In the example below, we adopt this representation for simplicity, where Society A always displays greater mobility. However, in the experimental questionnaire, we randomize both the order of the questions and which society exhibits greater mobility in each question. |

| 5 | People who are repeatedly flagged for lack of attention and care in answering questionnaires (incomplete surveys, failure on control questions, or responding too quickly) may be removed from the subject pool. |

| 6 | We present the aggregate sample, as we did not find statistically significant differences between respondents assigned to the two questionnaire versions. |

| 7 | Nevertheless, some argue that a relatively well-educated sample could be useful for abstract questions that require reasoned judgments, such as assessing whether people’s perceptions are consistent with theoretical predictions (Amiel & Cowell, 1992; Gaertner & Schokkaert, 2012). |

References

- Acemoglu, D., Egorov, G., & Sonin, K. (2018). Social mobility and stability of democracy: Reevaluating de Tocqueville. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133, 1041–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D., Egorov, G., & Sonin, K. (2021). Chapter 13—Institutional change and institutional persistence. In A. Bisin, & G. Federico (Eds.), The handbook of historical economics (pp. 365–389). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H., Villamor, I., & Ramani, R. S. (2021). MTurk research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Management, 47, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2005). Preferences for redistribution in the land of opportunities. Journal of Public Economics, 89, 897–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A., Miano, A., & Stantcheva, S. (2020). The polarization of reality. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 110, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, Y. (1999). The measurement of income inequality: The subjective approach. In J. Silber (Ed.), Handbook of income inequality measurement (pp. 227–243). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, Y., Bernasconi, M., Cowell, F., & Dardanoni, V. (2015). Do we value mobility? Social Choice and Welfare, 44, 231–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, Y., & Cowell, F. A. (1992). Measurement of income inequality: Experimental test by questionnaire. Journal of Public Economics, 47, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A. B. (1970). On the measurement of inequality. Journal of Economic Theory, 2, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A. B., & Bourguignon, F. (1982). The comparison of multi-dimensioned distributions of economic status. The Review of Economic Studies, 49, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci, F., Forcina, A., & Dardanoni, V. (2001). Positive quadrant dependence and marginal modeling in two-way tables with ordered margins. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 96, 1497–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benabou, R., & Ok, E. A. (2001). Social mobility and the demand for redistribution: The POUM hypothesis. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 447–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berinsky, A. J., Huber, G. A., & Lenz, G. S. (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20, 351–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binzel, C., & Carvalho, J. P. (2017). Education, social mobility and religious movements: The Islamic revival in Egypt. The Economic Journal, 127, 2553–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelen, A. W., Haaland, I. K., & Tungodden, B. (2018). Beliefs about behavioral responses to taxation. Norwegian School of Economics. [Google Scholar]

- Chakravarty, S. R., Dutta, B., & Weymark, J. A. (1985). Ethical indices of income mobility. Social Choice and Welfare, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinquanta, G. (2020). Three essays on social mobility: Mobility dimensions, welfare evaluation and questionnaires evidence [Ph.D. thesis, University of Ca’ Foscari of Venice]. [Google Scholar]

- Corak, M. (2013). Income inequality, equality of opportunity, and intergenerational mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 27, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowell, F. A., & Flachaire, E. (2018). Measuring mobility. Quantitative Economics, 9, 865–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, M., & Dardanoni, V. (2009). The measurement of rank mobility. Journal of Economic Theory, 144, 1783–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardanoni, V. (1993). Measuring social mobility. Journal of Economic Theory, 61, 372–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardanoni, V. (1995). Income distribution dynamics: Monotone Markov chains make light work. Social Choice and Welfare, 12, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dardanoni, V., Fiorini, M., & Forcina, A. (2012). Stochastic monotonicity in intergenerational mobility tables. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 27, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, P., Sen, A., & Starrett, D. (1973). Notes on the measurement of inequality. Journal of Economic Theory, 6, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidai, S. (2018). Why do Americans believe in economic mobility? Economic inequality, external attributions of wealth and poverty, and the belief in economic mobility. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 79, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidai, S., & Gilovich, T. (2015). Building a more mobile America—One income quintile at a time. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, M. V., & Fiske, S. T. (2017). Movin’on up? How perceptions of social mobility affect our willingness to defend the system. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decancq, K., Fleurbaey, M., & Schokkaert, E. (2015). Chapter 2—Inequality, income, and well-being. In A. B. Atkinson, & F. Bourguignon (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2, pp. 67–140). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, D., & Vollmann, M. (2022). Misperceiving economic success: Experimental evidence on meritocratic beliefs and inequality acceptance. CESifo Working Paper No. 9983. CESifo. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, G. S. (2019). Concepts of social mobility. WIDER Working Paper No. 106. WIDER. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fields, G. S., & Ok, E. A. (1996). The meaning and measurement of income mobility. Journal of Economic Theory, 71, 349–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, R., Gladstone, K., Kuziemko, I., & Naidu, S. (2017). Do Americans want to tax capital? Evidence from online surveys. NBER working paper series No. 23907. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisman, R., Kuziemko, I., & Vannutelli, S. (2021). Distributional preferences in larger groups: Keeping up with the Joneses and keeping track of the tails. Journal of the European Economic Association, 19, 1407–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fréchet, M. (1951). Sur les tableaux de corrélation dont les marges sont données. Ann. Univ. Lyon 3ˆ e serie Sciences Sect. A, 14, 53–77. [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner, W., & Schokkaert, E. (2012). Empirical social choice: Questionnaire-experimental studies on distributive justice. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, P., & Spolaore, E. (2002). On the evaluation of economic mobility. The Review of Economic Studies, 69, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäntti, M., & Jenkins, S. P. (2015). Chapter 10—Income mobility. In A. B. Atkinson, & F. Bourguignon (Eds.), Handbook of income distribution (Vol. 2, pp. 807–935). Elsevier. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolm, S. C. (1976). Unequal inequalities. II. Journal of Economic Theory, 13, 82–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuziemko, I., Norton, M. I., Saez, E., & Stantcheva, S. (2015). How elastic are preferences for redistribution? Evidence from randomized survey experiments. American Economic Review, 105, 1478–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markandya, A. (1984). The welfare measurement of changes in economic mobility. Economica, 51, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengel, F., & Weidenholzer, E. (2023). Preferences for redistribution. Journal of Economic Surveys, 37, 1660–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paolacci, G., Chandler, J., & Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Running experiments on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Judgment and Decision Making, 5, 411–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, D., & Genicot, G. (2023). Measuring upward mobility. American Economic Review, 113, 3044–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stantcheva, S. (2023). How to run surveys: A guide to creating your own identifying variation and revealing the invisible. Annual Review of Economics, 15, 205–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y. (2018). Education, social mobility, and the mismatch of talents. Economic Theory, 65, 575–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de gaer, D., & Palmisano, F. (2021). Growth, mobility and social progress. Journal of Comparative Economics, 49, 164–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de gaer, D., Schokkaert, E., & Martinez, M. (2001). Three meanings of intergenerational mobility. Economica, 68, 519–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinzierl, M. (2017). Popular acceptance of inequality due to innate brute luck and support for classical benefit-based taxation. Journal of Public Economics, 155, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Society A | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Status | Child Status | ||

| Low | High | ||

| Low | a | ||

| High | |||

| Society A | |||

| Parent Status | Child Status | ||

| Low | High | ||

| Low | a | ||

| High | |||

| Society B | |||

| Parent Status | Child Status | ||

| Low | High | ||

| Low | b | ||

| High | |||

| Society A | |||

| Parent Status | Child Status | ||

| 20,000 | 80,000 | 100,000 | |

| 20,000 | |||

| 80,000 | |||

| 100,000 | 1 | ||

| Society B | |||

| Parent Status | Child Status | ||

| 20,000 | 80,000 | 100,000 | |

| 20,000 | |||

| 80,000 | |||

| 100,000 | 1 | ||

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Min | Max | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Demographics—(D) | |||||

| Age | 35.29 | 10.62 | 19 | 73 | 242 |

| Gender (1 = female, 0 = male) | 0.38 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 242 |

| Ethnicity (1 = white, 0 = otherwise) | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0 | 1 | 242 |

| Education (1 = master’s degree, 0 = less) | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0 | 1 | 242 |

| Marital status (1 = married or domestic partnership, 0 = otherwise) | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | 242 |

| Economic prospects—(P) | |||||

| (P1) Standard of living vs. US average | 2.71 | 0.75 | 1 | 5 | 242 |

| (1 = much lower, …, 5 = much higher) | |||||

| (P2) Standard of living vs. parents | 2.86 | 0.96 | 1 | 5 | 242 |

| (1 = much lower, …, 5 = much higher) | |||||

| (P3) Income opportunities vs. parents | 3.00 | 1.03 | 1 | 5 | 242 |

| (1 = much lower, …, 5 = much higher) | |||||

| Values—(V) | |||||

| (V1) Value of independence in economic positions | 3.77 | 0.74 | 1 | 5 | 242 |

| (1 = strongly disagree, …, 5 = strongly agree) | |||||

| (V2) Independence as equality of opportunity | 3.75 | 0.83 | 1 | 5 | 242 |

| (1 = strongly disagree, …, 5 = strongly agree) | |||||

| Q4 | Q10 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | = | A | B | = | ||||

| Q1 | A | 48.82% | 4.72% | 1.57% | Q1 | A | 44.88% | 6.30% | 3.94% |

| B | 15.75% | 3.15% | 3.94% | B | 11.81% | 7.87% | 3.15% | ||

| = | 10.24% | 4.72% | 7.09% | = | 11.81% | 5.51% | 4.72% | ||

| Q4 | A | 62.60% | 8.66% | 3.94% | |||||

| B | 3.15% | 8.66% | 0.79% | ||||||

| = | 3.15% | 2.36% | 7.09% | ||||||

| Q4bis | Q10bis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | = | A | B | = | ||||

| Q1bis | A | 54.78% | 2.61% | 4.35% | Q1bis | A | 55.65% | 3.48% | 2.61% |

| B | 7.83% | 8.70% | 6.09% | B | 7.83% | 13.04% | 1.74% | ||

| = | 5.22% | 4.35% | 6.09% | = | 6.96% | 3.48% | 5.22% | ||

| Q4bis | A | 59.13% | 6.96% | 1.74% | |||||

| B | 3.48% | 7.83% | 4.35% | ||||||

| = | 7.83% | 5.22% | 3.48% | ||||||

| Q6 | Q7 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | = | A | B | = | ||||

| Q5 | A | 40.94% | 5.51% | 3.94% | Q5 | A | 28.35% | 7.09% | 14.96% |

| B | 9.45% | 16.54% | 3.94% | B | 9.45% | 14.96% | 5.51% | ||

| = | 1.57% | 4.72% | 13.39% | = | 5.51% | 3.94% | 10.24% | ||

| Q6 | A | 28.35% | 8.66% | 14.96% | |||||

| B | 9.45% | 12.60% | 4.72% | ||||||

| = | 5.51% | 4.72% | 11.02% | ||||||

| Q6bis | Q7bis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | = | A | B | = | ||||

| Q5bis | A | 53.04% | 4.35% | 3.48% | Q5bis | A | 38.26% | 10.43% | 12.17% |

| B | 9.57% | 11.30% | 1.74% | B | 4.35% | 14.78% | 3.48% | ||

| = | 3.48% | 2.61% | 10.43% | = | 5.22% | 1.74% | 9.57% | ||

| Q6bis | A | 38.26% | 14.78% | 13.04% | |||||

| B | 4.35% | 9.57% | 4.35% | ||||||

| = | 5.22% | 2.61% | 7.83% | ||||||

| Q3 | Q9 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | = | A | B | = | ||||

| Q2 | A | 24.41% | 10.24% | 3.94% | Q8 | A | 29.92% | 23.62% | 5.51% |

| B | 11.81% | 19.69% | 4.72% | B | 5.51% | 18.11% | 6.30% | ||

| = | 5.51% | 7.87% | 11.81% | = | 1.57% | 3.15% | 6.30% | ||

| Q3bis | Q9bis | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | = | A | B | = | ||||

| Q2bis | A | 27.83% | 7.83% | 4.35% | Q8bis | A | 34.78% | 19.13% | 7.83% |

| B | 8.70% | 24.35% | 7.83% | B | 3.48% | 16.52% | 3.48% | ||

| = | 6.09% | 6.09% | 6.96% | = | 2.61% | 2.61% | 9.57% | ||

| Greater Mobility in | Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Society A | Society B | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| Q1 (2 × 2—stochastic independence) | 1.076 *** | −0.207 | 1.283 *** |

| (0.287) | (0.333) | (0.283) | |

| Q2 (as Q1 with income decline) | 0.562 * | 0.121 | 0.440 |

| (0.297) | (0.315) | (0.272) | |

| Q3 (as Q1 with income growth ) | 0.858 *** | 0.378 | 0.480 * |

| (0.307) | (0.325) | (0.267) | |

| Q4 (2 × 2—immobility) | 1.978 *** | −0.233 | 2.211 *** |

| (0.329) | (0.416) | (0.330) | |

| Q5 (3 × 3—mobility between middle-top classes) | 1.097 *** | 0.182 | 0.915 *** |

| (0.300) | (0.341) | (0.274) | |

| Q6 (3 × 3—mobility between bottom-middle classes) | 1.050 *** | −0.009 | 1.059 *** |

| (0.294) | (0.339) | (0.282) | |

| Q7 (3 × 3—mobility between all classes) | 0.478 * | −0.419 | 0.897 *** |

| (0.288) | (0.324) | (0.281) | |

| Q8 (2 × 2—changes generations’ size) | 1.857 *** | 0.773 ** | 1.084 *** |

| (0.338) | (0.376) | (0.272) | |

| Q9 (as Q8 with income growth) | 0.857 *** | 0.678 ** | 0.179 |

| (0.320) | (0.327) | (0.266) | |

| Q10 (2 × 2—immobility) | 1.948 *** | 0.281 | 1.666 *** |

| (0.336) | (0.394) | (0.286) | |

| Q1bis (2 × 2—stochastic independence) | 1.492 *** | 0.093 | 1.399 *** |

| (0.326) | (0.373) | (0.291) | |

| Q2bis (as Q1 with income decline) | 0.822 ** | 0.480 | 0.342 |

| (0.322) | (0.332) | (0.274) | |

| Q3bis (as Q1 with income growth ) | 0.888 *** | 0.414 | 0.474 * |

| (0.325) | (0.339) | (0.275) | |

| Q4bis (2 × 2—immobility) | 1.538 *** | −0.332 | 1.870 *** |

| (0.319) | (0.396) | (0.320) | |

| Q5bis (3 × 3—mobility between middle-top classes) | 1.421 *** | 0.037 | 1.384 *** |

| (0.323) | (0.371) | (0.291) | |

| Q6bis (3 × 3—mobility between bottom-middle classes) | 1.566 *** | −0.122 | 1.687 *** |

| (0.324) | (0.385) | (0.306) | |

| Q7bis (3 × 3—mobility between all classes) | 0.724 ** | −0.225 | 0.949 *** |

| (0.307) | (0.338) | (0.285) | |

| Q8bis (2 × 2—changes generations’ size) | 1.550 *** | 0.189 | 1.361 *** |

| (0.330) | (0.378) | (0.298) | |

| Q9bis (as Q8 with income growth) | 0.754 ** | 0.324 | 0.431 |

| (0.313) | (0.331) | (0.278) | |

| Q10bis (2 × 2—immobility) | 2.140 *** | 0.474 | 1.666 *** |

| (0.385) | (0.431) | (0.303) | |

| Age | −0.007 | −0.005 | −0.002 |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| Gender (1 = female) | 0.094 | 0.202 | −0.108 |

| (0.129) | (0.139) | (0.107) | |

| Ethnicity (1 = white) | 0.420 *** | 0.451 *** | −0.031 |

| (0.138) | (0.150) | (0.120) | |

| Education (1 = master degree) | 0.672 *** | 0.700 *** | −0.028 |

| (0.216) | (0.229) | (0.149) | |

| Marital status (1 = married) | −0.622 *** | −0.047 | −0.574 *** |

| (0.127) | (0.136) | (0.106) | |

| (P1) Standard of living relative to average in the US | −0.119 | 0.008 | −0.126 ** |

| (0.074) | (0.079) | (0.060) | |

| (P2) Standard of living relative to parents | 0.227 *** | 0.246 *** | −0.019 |

| (0.084) | (0.092) | (0.074) | |

| (P3) Income opportunities relative to parents | −0.053 | −0.057 | 0.003 |

| (0.079) | (0.085) | (0.067) | |

| (V1) Independence preferable | 0.059 | 0.097 | −0.038 |

| (0.076) | (0.081) | (0.063) | |

| (V2) Independence as equality of opportunity | 0.260 *** | 0.112 | 0.148 ** |

| (0.072) | (0.073) | (0.062) | |

| Observations | 2420 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bernasconi, M.; Cinquanta, G.; Dardanoni, V.; Prete, V. Mobility Comparisons: Theoretical Definitions and People’s Perceptions. Games 2025, 16, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16030024

Bernasconi M, Cinquanta G, Dardanoni V, Prete V. Mobility Comparisons: Theoretical Definitions and People’s Perceptions. Games. 2025; 16(3):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16030024

Chicago/Turabian StyleBernasconi, Michele, Giulio Cinquanta, Valentino Dardanoni, and Vincenzo Prete. 2025. "Mobility Comparisons: Theoretical Definitions and People’s Perceptions" Games 16, no. 3: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16030024

APA StyleBernasconi, M., Cinquanta, G., Dardanoni, V., & Prete, V. (2025). Mobility Comparisons: Theoretical Definitions and People’s Perceptions. Games, 16(3), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/g16030024