One Justice for All? Social Dilemmas, Environmental Risks and Different Notions of Distributive Justice

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Environmental Problems as Social Dilemmas

1.2. Environmental Justice and Heterogeneity in Justice Concerns

2. Theoretical and Empirical Background

2.1. Different Areas of Environmental Justice Research

2.2. Four Notions of Distributive Justice

2.3. Previous Research on Justice Preferences and Justice Perceptions at Different Levels

3. Data and Variables

3.1. Empirical Data: Samples of Four European Cities

3.2. Dependent Variable: Choice of Justice Principles

- All citizens should equally benefit from the protection measures, irrespective of their current noise exposure;

- The citizens with the highest noise exposure should benefit most from the protection measures;

- The highest number of citizens should benefit from the protection measures, irrespective of their current noise exposure;

- Current differences should be levelled as much as possible, so that all citizens have approximately equal levels of noise exposure.

3.3. Independent Variables: Socio-Economic Status and Noise Exposure

4. Results

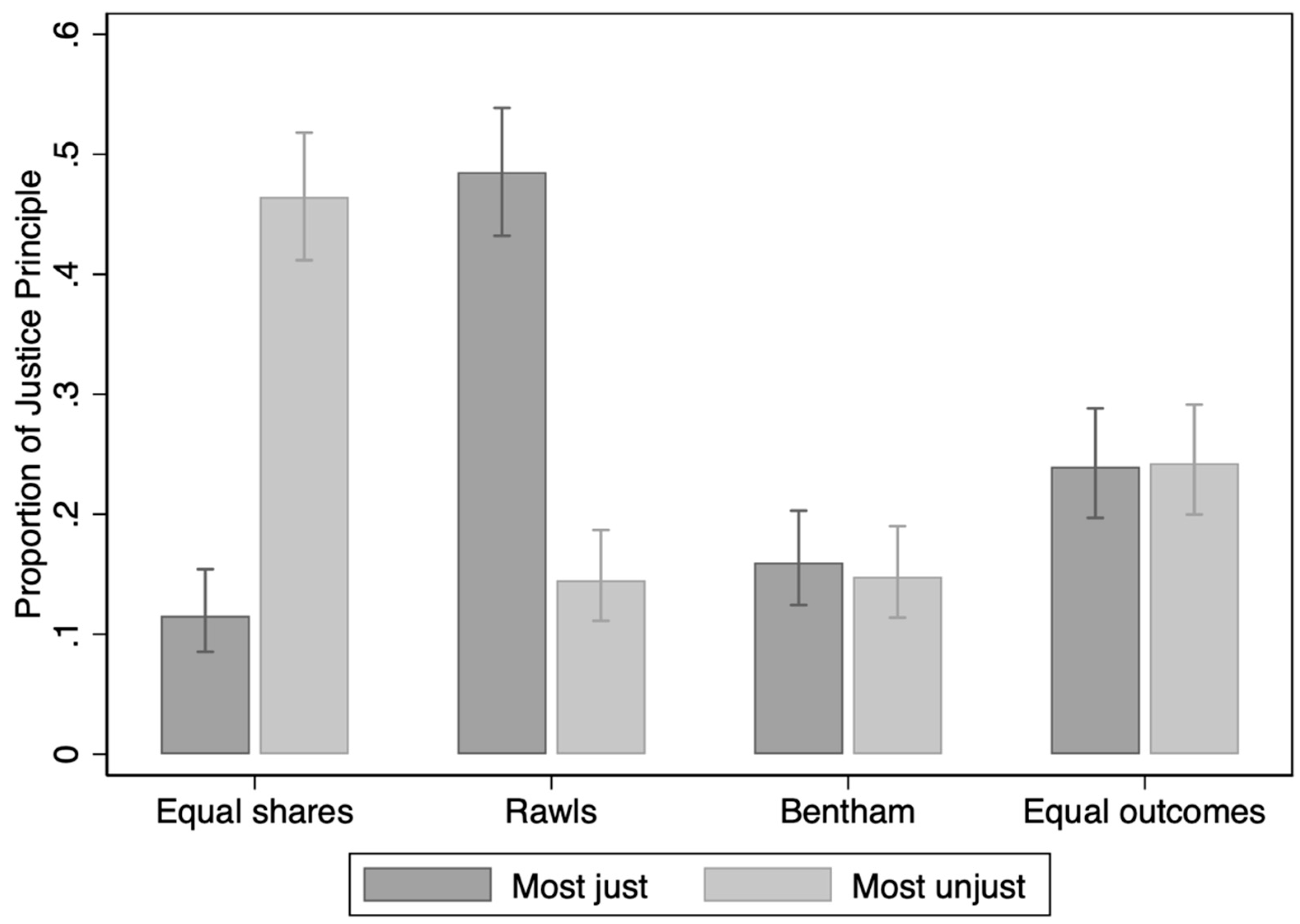

4.1. Justice Preferences across the Four Cities

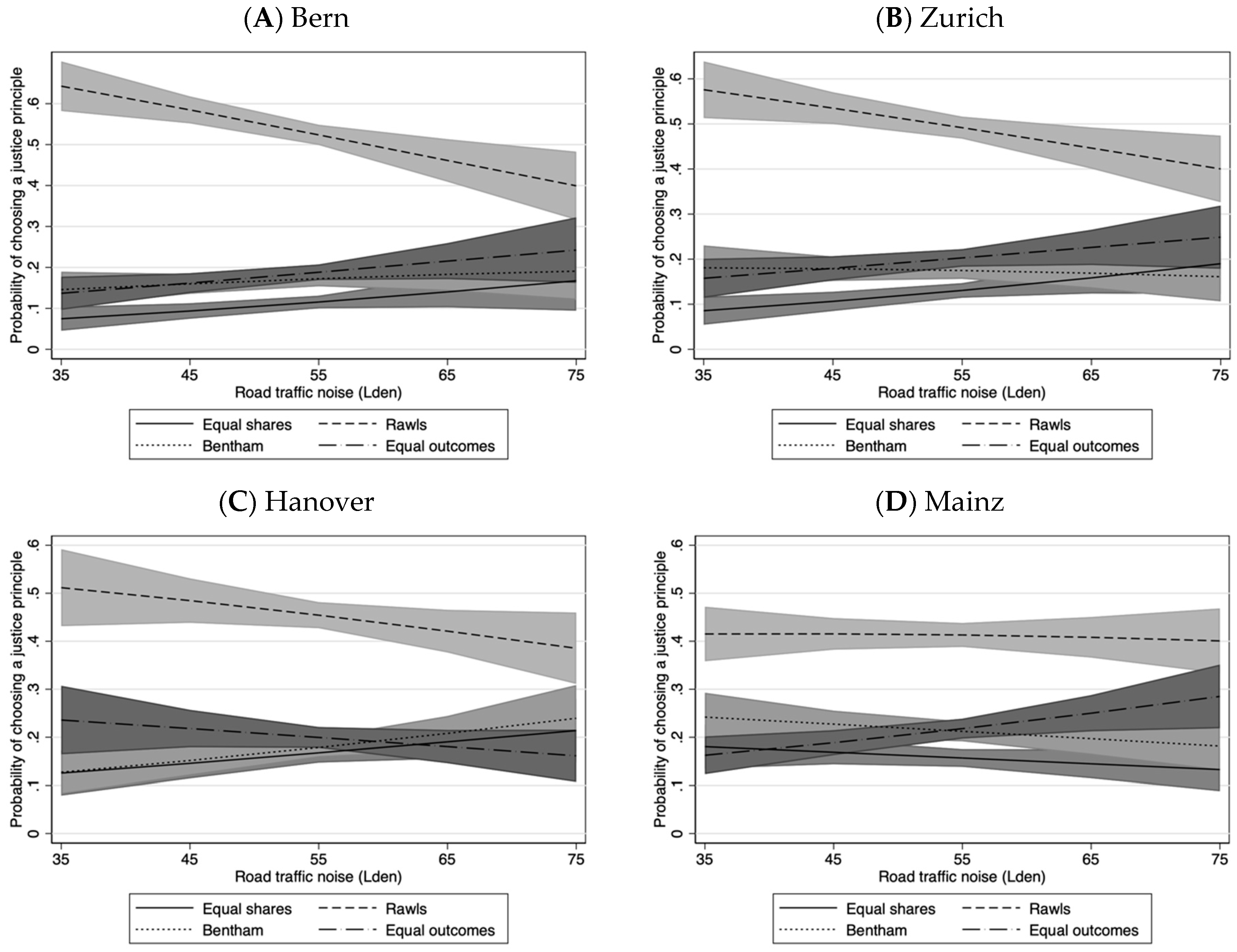

4.2. Heterogeneity of Justice Preferences

4.3. Additional Findings

- Veil of ignorance I: Imagine you move to another city. This city is just planning measures to protect citizens from road traffic noise: In your opinion, which of the following principles is most just/fair?

- Veil of ignorance II: Imagine you move to another city. It is difficult to find a flat in this city. Therefore, you do not know yet where you will live in this city and how noisy or quiet it will be in your new area. This city is planning measures to protect citizens from road traffic noise: In your opinion, which of the following principles is most just/fair?

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variable | Bern | Zurich | Hanover | Mainz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education in years | Equal: −0.147 (−4.92) | Equal: −0.115 (−4.20) | Equal: −0.134 (−3.65) | Equal: −0.119 (−3.47) |

| Rawls: 0.127 (6.06) | Rawls: 0.088 (4.22) | Rawls: 0.078 (2.47) | Rawls: 0.127 (4.31) | |

| Benth: 0.168 (6.18) | Benth: 0.110 (4.15) | Benth: 0.105 (2.64) | Benth: 0.159 (4.55) | |

| LL0 | −2307.33 | −2131.63 | −1584.05 | −2034.09 |

| LLModel | −2231.39 | −2087.72 | −1558.28 | −1992.86 |

| n | 1960 | 1724 | 1234 | 1545 |

| Income in thousands CHF/Euro | Equal: −0.179 (−4.26) | Equal: −0.104 (−2.77) | Equal: −0.295 (−2.77) | Equal: −0.222 (−2.60) |

| Rawls: 0.064 (2.35) | Rawls: 0.086 (3.29) | Rawls: 0.207 (2.82) | Rawls: 0.160 (2.69) | |

| Benth: 0.071 (2.13) | Benth: 0.136 (4.33) | Benth: 0.266 (3.17) | Benth: 0.190 (2.84) | |

| LL0 | −2099.33 | −1965.45 | −1313.46 | −1667.45 |

| LLModel | −2073.74 | −1938.27 | −1291.63 | −1649.45 |

| n | 1789 | 1591 | 1028 | 1276 |

| Socio-Economic Status (ISEI) | Equal: −0.019 (−3.18) | Equal: −0.018 (−3.28) | Equal: −0.006 (−0.93) | Equal: −0.022 (−3.58) |

| Rawls: 0.020 (5.02) | Rawls: 0.013 (3.11) | Rawls: 0.015 (2.86) | Rawls: 0.014 (2.91) | |

| Benth: 0.020 (4.23) | Benth: 0.020 (3.93) | Benth: 0.020 (3.24) | Benth: 0.015 (2.76) | |

| LL0 | −2040.50 | −1844.64 | −1352.00 | −1695.04 |

| LLModel | −2001.89 | −1815.98 | −1341.02 | −1668.98 |

| n | 1731 | 1512 | 1054 | 1288 |

| Actual noise exposure in dB(A) | Equal: 0.006 (0.43) | Equal: 0.008 (0.71) | Equal: 0.023 (1.86) | Equal: −0.022 (−2.20) |

| Rawls: −0.026 (−2.63) | Rawls: −0.021 (−2.30) | Rawls: 0.002 (0.23) | Rawls: −0.015 (−1.90) | |

| Benth: −0.008 (−0.62) | Benth: −0.014 (−1.30) | Benth: 0.025 (2.10) | Benth: −0.021 (−2.34) | |

| LL0 | −2397.22 | −2147.35 | −1669.77 | −2235.13 |

| LLModel | −2392.66 | −2142.08 | −1665.52 | −2231.51 |

| n | 1953 | 1740 | 1296 | 1601 |

Appendix B

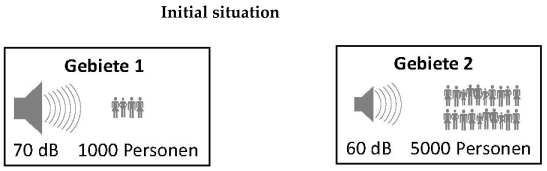

Version 1

Version 2

- ○

- The aim of Proposal A is to ensure that the same average noise level is not exceeded across the entire municipal area with the protective measures. The measures are therefore concentrated on the areas with very high noise pollution where few people live.

- ○

- In Proposal B, the aim is for all residents to benefit equally from the protective measures, regardless of their current noise exposure. Therefore, traffic noise is reduced by the same amount across the entire municipality.

- ○

- The aim of Proposal C is to ensure that as many residents as possible experience a substantial reduction in noise pollution. The measures are therefore concentrated on areas with high noise pollution where many people live.

| Areas with Very High Noise Pollution 1000 Citizen | Areas with High Noise Pollution 5000 Citizen | |

| Traffic noise in dB without measures | 70 | 60 |

| Proposal A | 60 | 60 |

| Proposal B | 65 | 55 |

| Proposal C | 70 | 50 |

Version 3

| Proposal A All measures are implemented in areas with very high noise pollution so that the same average noise level is not exceeded throughout the entire municipal area. | Proposal B The measures are distributed evenly between areas 1 and 2 so that all residents benefit equally from them, regardless of their current noise exposure. | Proposal C All measures are implemented in areas with high noise pollution so that as many residents as possible experience a substantial reduction in noise pollution. |

| 1 | We decided not to introduce the equity concept here because it has two, relatively different meanings within literature. Based on classical equity theory [44], the first meaning pertains to a fair balance of own contributions/inputs/costs and own rewards/outcomes/benefits in a social relationship. The second meaning in contexts without direct own contributions pertains to a distribution of benefits/goods (or costs/bads) that takes different starting positions into account (including different needs) and tries to equalize the final distribution. |

| 2 | We developed and repeatedly modified this question in a series of pretests. |

| 3 | The dependent variable is a classification of four categories (“nominal scale”). Hence, we used the multinominal logit model to estimate the impact of education, income, socioeconomic status, and level of noise exposure on the choice of justice principles. We estimated bivariate linear equations by maximum likelihood estimation (MLE). The category “equal outcome” is chosen as a reference category. Coefficients of the respective category (e.g., “Rawls”) should be interpreted as an increase (decrease) in the log-odds (p/(1−p); p is the proportion of votes for the respective principle) by an increase of a unit of the independent variable. In formal terms: pj/(1−pj) = cj + bjx where pj is the proportion of support for justice principle j, cj and bj are the parameters estimated by the data and x is the independent variable. The solution for pj results in a non-linear relation between the independent variable and the proportion of support for the respective justice principle. Figure 2 graphically depicts the relationship pj = f(x) between the socioeconomic index and the proportion of votes for the justice principles in the four cities. Figure 3 shows the relationship between the level of noise exposure and the proportion of support for the justice principles. |

References

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollock, P. Social Dilemmas: The Anatomy of Cooperation. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 183–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, J.W. A Noncooperative Equilibrium for Supergames. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1971, 38, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, R. The Evolution of Cooperation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dal Bó, P. Cooperation under the Shadow of the Future: Experimental Evidence from Infinitely Repeated Games. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 1591–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliet, D. Communication and cooperation in social dilemmas: A meta-analytic review. J. Confl. Resolut. 2010, 54, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. A Theory of Fairness, Competition, and Cooperation. Q. J. Econ. 1999, 114, 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E.; Schmidt, K.M. The economics of fairness, reciprocity and altruism–experimental evidence and new theories. In Handbook of the Economics of Giving, Altruism and Reciprocity; Kolmand, S.-C., Ythier, J.M., Eds.; North-Holland: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 615–691. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, G.E.; Ockenfels, A. ERC: A Theory of Equity, Reciprocity, and Competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 166–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, O.P.; Hilbe, C.; Chatterjee, K.; Nowak, M.A. Social dilemmas among unequals. Nature 2019, 572, 524–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinangeli, A.F.M.; Martinsson, P. We, the rich: Inequality, identity and cooperation. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2020, 178, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, O.; Weesie, J. Inequality and Procedural Justice in Social Dilemmas. J. Math. Sociol. 2009, 33, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Simpson, B. Social Identity and Cooperation in Social Dilemmas. Ration. Soc. 2006, 18, 443–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksoy, O. Crosscutting circles in a social dilemma: Effects of social identity and inequality on cooperation. Soc. Sci. Res. 2019, 82, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fehr, E.; Naef, M.; Schmidt, K.M. Inequality Aversion, Efficiency, and Maximin Preferences in Simple Distribution Experiments: Comment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2006, 96, 1912–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellow, D.N.; Brulle, R.J. (Eds.) Power, Justice, and the Environment: A Critical Appraisal of the Environmental Justice Movement; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ringquist, E.J. Assessing evidence of environmental inequities: A meta-analysis. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2005, 24, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulle, R.J.; Pellow, D.N. Environmental Justice: Human Health and Environmental Inequalities. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2006, 27, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohai, P.; Pellow, D.; Roberts, J.T. Environmental Justice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzhaf, S.H.; Ma, L.; Timmis, C. Environmental Justice: The Economics of Race, Place, and Pollution. J. Econ. Perspect. 2019, 33, 185–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banzhaf, S.H.; Ma, L.; Timmis, C. Environmental Justice: Establishing Causal Relationships. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2019, 11, 377–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, B. Environmental Justice: Issues, Policies, and Solutions; Island Press: Covelo, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, D. Toward an Integrative Framework for Environmental Justice Research: A Synthesis and Extension of the Literature. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisendörfer, P. Umweltgerechtigkeit. Von sozial-räumlicher Ungleichheit hin zu postulierter Ungerechtigkeit lokaler Umweltbelastungen. Soz. Welt 2014, 65, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebe, U.; Bartczak, A.; Meyerhoff, J. A Turbine is not only a Turbine: The Role of Social Context and Fairness Characteristics for the Local Acceptance of Wind Power. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. Distributive Justice: What the People Think. Ethics 1992, 102, 555–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lange, P.A.M.; Joireman, J.; Parks, C.D.; Van Dijk, E. The Psychology of Social Dilemmas: A Review. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2013, 120, 125–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F. Environmental Justice Analysis: Theories, Methods, and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, G. Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder, K.; Downey, L. Interneighborhood Migration, Race, and Environmental Hazards: Modeling Microlevel Processes of Environmental Inequality. Am. J. Sociol. 2010, 115, 1110–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohai, P.; Saha, R. Which came first, people or pollution? A review of theory and evidence from longitudinal environmental justice studies. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 125011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preisendörfer, P.; Bruderer Enzler, H.; Diekmann, A.; Hartmann, J.; Kurz, K.; Liebe, U. Pathways to Environmental Inequality: How Urban Traffic Noise Annoyance Varies Across Socioeconomic Subgroups. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekmann, A.; Bruderer Enzler, H.; Hartmann, J.; Kurz, K.; Liebe, U.; Preisendörfer, P. Environmental Inequality in Four European Cities: A Study Combining Household Survey and Geo-Referenced Data. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2023, 39, 44–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullard, R.D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality, 3rd ed.; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schlosberg, D.; Carruthers, D. Indigenous Struggles, Environmental Justice, and Community Capabilities. Glob. Environ. Politics 2010, 10, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.L. Pesticide Drift and the Pursuit of Environmental Justice; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, D. Conceptualizing Environmental Justice: Plural Frames and Global Claims in Land Between the Rivers, Kentucky; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S. Models of Justice in the Environmental Debate. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syme, G.; Kals, E.; Nancarrow, B.E.; Montada, L. Ecological Risks and Community Perceptions of Fairness and Justice: A Cross-Cultural Model. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 2006, 12, 102–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, C.L.; Hegtvedt, K.A.; Watson, L.A.; Johnson, C. Justice for All? Factors Affecting Perceptions of Environmental and Ecological Injustice. Soc. Justice Res. 2014, 27, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Kals, E.; Feygina, I. Justice and Environmental Sustainability. In Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research; Sabbagh, C., Schmitt, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Arneson, R. Egalitarianism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2013; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2013/entries/egalitarianism/ (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Adams, S.J. Inequity in Social Exchange. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1965; Volume 2, pp. 267–299. [Google Scholar]

- Cudd, A.; Eftekhari, S. Contractarianism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/contractarianism/ (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Rawls, J. A Theory of Justice; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Binmore, K. Playing Fair. In Game Theory and the Social Contract; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Driver, J. The History of Utilitarianism. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2014; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/utilitarianism-history/ (accessed on 24 June 2024).

- Bentham, J. A Fragment on Government: PREFACE. In The Collected Works of Jeremy Bentham: A Comment on the Commentaries and A Fragment on Government; Burns, J.H., Hart, H.L.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Baliga, S.; Maskin, E. Mechanism design for the environment. In Handbook of Environmental Economics; Mäler, K.-G., Vincent, J.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 306–324. [Google Scholar]

- Frohlich, N.; Oppenheimer, J.A.; Eavey, C.L. Choices of Principles of Distributive Justice in Experimental Groups. Am. J. Political Sci. 1987, 31, 606–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frohlich, N.; Oppenheimer, J.A. Choosing Justice: Experimental Approach to Ethical Theory; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.T.; Matland, R.E.; Michelbach, P.A.; Bornstein, B.H. Just Deserts: An Experimental Study of Distributive Justice Norms. Am. J. Political Sci. 2001, 45, 749–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelbach, P.A.; Scott, J.T.; Matland, R.E.; Bornstein, B.H. Doing Rawls Justice: An Experimental Study of Income Distribution Norms. Am. J. Political Sci. 2003, 47, 523–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konow, J.; Schwettmann, L. The Economics of Justice. In Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research; Sabbagh, C., Schmitt, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Beatley, T. Applying Moral Principles to Growth Management. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 1984, 50, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebig, S.; Sauer, C. Sociology of Justice. In Handbook of Social Justice Theory and Research; Sabbagh, C., Schmitt, M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- Auspurg, K.; Hinz, T. Factorial Survey Experiments; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel, M.M.; Scheve, K.F. Mass Support for Global Climate Agreements Depends on Institutional Design. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 13763–13768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebe, U.; Preisendörfer, P.; Bruderer Enzler, H. The Social Acceptance of Airport Expansion Scenarios: A Factorial Survey Experiment. Transp. Res. Part D 2020, 84, 102363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys. The Tailored Design Method, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- AAPOR. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys, 9th ed.; The American Association for Public Opinion Research: Oakbrook Terrace, IL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bruderer Enzler, H.; Diekmann, A.; Hartmann, J.; Herold, L.; Kilburger, K.; Kurz, K.; Liebe, U.; Preisendörfer, P.; Widmer, A. Dokumentation Projekt “Umweltgerechtigkeit—Soziale Verteilungsmuster, Gerechtigkeitseinschätzungen und Akzeptanzschwellen”; ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rawls, J. Justice as Fairness: Political not Metaphysical. Philos. Public Aff. 1985, 14, 223–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ganzeboom, H.B.G.; De Graaf, P.M.; Treiman, D.J. A Standard International Socio-Economic Index of Occupational Status. Soc. Sci. Res. 1992, 21, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office. Federal Register of Buildings and Dwellings; Swiss Federal Statistical Office: Bern, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brink, M.; Schäffer, B.; Pieren, R.; Wunderli, J.M. Conversion between Noise Exposure Indicators Leq24h, LDay, LEvening, LNight, Ldn and Lden: Principles and Practical Guidance. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2018, 221, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Traub, S.; Seidl, C.; Schmidt, U.; Levati, M.V. Friedman, Harsanyi, Rawls, Boulding—Or somebody else? An experimental investigation of distributive justice. Soc. Choice Welf. 2005, 24, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsanyi, J.C. Can the Maximin Principle Serve as a Basis for Morality? A Critique of John Rawls’s Theory. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1975, 69, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Dron, C. The effect of an experimental veil of ignorance on intergenerational resource sharing: Empirical evidence from a sequential multi-person dictator game. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 175, 106662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Zenkyo, M.; Sakamoto, H. Making the Veil of Ignorance Work: Evidence from Survey Experiments. In Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Volume 4; Lombrozo, T., Knobe, J., Nichols, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021; pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Bowker, A.H. A Test of Symmetry in Contingency Tables. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1948, 43, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekmann, A.; Naef, M. Codebook Schweizer Umweltsurvey 2018; ETH Zürich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Reeskens, T.; van Oorschot, W. Equity, equality, or need? A study of popular preferences for welfare redistribution principles across 24 European countries. J. Eur. Public Policy 2013, 20, 1174–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Anjou, L.; Steijn, A.; van Aarsen, D. Social Position, Ideology and Distributive Justice. Soc. Justice Res. 1995, 8, 351–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hootegem, A.; Abts, K.; Meuleman, B. Differentiated Distributive Justice Preferences? Configurations of Preferences for Equality, Equity and Need in Three Welfare Domains. Soc. Justice Res. 2020, 33, 257–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korndörfer, M.; Egloff, B.; Schmukle, S.C. A Large Scale Test of the Effect of Social Class on Prosocial Behavior. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0133193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tutic, A.; Liebe, U. Contact Heterogeneity as a Mediator of the Relationship between Social Class and Altruistic Giving. Socius Sociol. Res. A Dyn. World 2020, 6, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, B. The Social Psychology of the Gift. Am. J. Sociol. 1967, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Ven, J. The Demand for Social Approval and Status as a Motivation to Give. J. Institutional Theor. Econ. 2002, 158, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, D.; Strobel, M. In equality Aversion, Efficiency, and Maximin Preferences in Simple Distribution Experiments. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, D.E. The Rise of the Environmental Justice Paradigm: Injustice Framing and the Social Construction of Environmental Discourses. Am. Behav. Sci. 2000, 43, 508–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holifield, R. Defining Environmental Justice and Environmental Racism. Urban Geogr. 2001, 22, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandel, M.J. Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller, J.; Hangartner, D.; Yamamoto, T. Validating Vignette and Conjoint Survey Experiments against Real-World Behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 2395–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, S.; Dsouza, E.; Kim, R.; Schulz, J.; Henrich, J.; Shariff, A.; Bonnefon, J.-F.; Rahwan, I. The Moral Machine Experiment. Nature 2018, 563, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Tversky, A. (Eds.) Choices, Values and Frames; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, G.E.; Brandts, J.; Ockenfels, A. Fair Procedures: Evidence from Games Involving Lotteries. Econ. J. 2005, 115, 1054–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, M.W. A model of procedural and distributive fairness. Theory Decis. 2011, 70, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Justice Theory | Distributive Justice Principle |

|---|---|

| Egalitarianism | (a) Equal shares: All citizens equally benefit, irrespective of current differences. (b) Equal outcomes: Current differences are levelled by benefits in order that all citizens face equal conditions. |

| Contractarianism (Rawls) | The greatest benefit to the least advantaged citizens. |

| Utilitarianism (Bentham) | The greatest benefit to the greatest number of citizens. |

| Bern | Zurich | Hanover | Mainz | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Woman | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.53 | ||||

| Age in years | 43.31 | 13.53 | 42.96 | 13.34 | 44.62 | 13.98 | 42.90 | 14.86 |

| Education in years (8–18) | 15.10 | 3.00 | 15.11 | 3.11 | 14.94 | 2.45 | 14.98 | 2.36 |

| Income in CHF/Euro | 5521 | 2446 | 5941 | 2657 | 2220 | 1244 | 2378 | 1317 |

| International Socio-Economic Index (16–90) | 53.35 | 17.29 | 55.64 | 17.18 | 52.67 | 16.30 | 52.73 | 16.15 |

| Road traffic noise exposure in dB(A) | 51.93 | 6.11 | 53.08 | 7.11 | 55.23 | 7.50 | 52.87 | 8.40 |

| Justice Preferences 2017 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equal Shares | Rawls | Bentham | Equal Outcomes | Total | ||

| Justice Preferences 2018 | Equal shares | 4 | 12 | 3 | 5 | 24 |

| 17.39 | 4.51 | 3.95 | 6.33 | 5.41 | ||

| Rawls | 5 | 179 | 31 | 37 | 252 | |

| 21.74 | 67.29 | 40.79 | 46.84 | 56.76 | ||

| Bentham | 6 | 39 | 33 | 12 | 90 | |

| 26.09 | 14.66 | 43.42 | 15.19 | 20.27 | ||

| Equal outcomes | 8 | 36 | 9 | 25 | 78 | |

| 34.78 | 13.53 | 11.84 | 31.65 | 17.57 | ||

| Total | 23 | 266 | 76 | 79 | 444 | |

| 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liebe, U.; Bruderer Enzler, H.; Diekmann, A.; Preisendörfer, P. One Justice for All? Social Dilemmas, Environmental Risks and Different Notions of Distributive Justice. Games 2024, 15, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/g15040025

Liebe U, Bruderer Enzler H, Diekmann A, Preisendörfer P. One Justice for All? Social Dilemmas, Environmental Risks and Different Notions of Distributive Justice. Games. 2024; 15(4):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/g15040025

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiebe, Ulf, Heidi Bruderer Enzler, Andreas Diekmann, and Peter Preisendörfer. 2024. "One Justice for All? Social Dilemmas, Environmental Risks and Different Notions of Distributive Justice" Games 15, no. 4: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/g15040025

APA StyleLiebe, U., Bruderer Enzler, H., Diekmann, A., & Preisendörfer, P. (2024). One Justice for All? Social Dilemmas, Environmental Risks and Different Notions of Distributive Justice. Games, 15(4), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/g15040025