Appendix A.2. Reciprocity Model

In this section, I introduce the intention-based reciprocity model of Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger [

8]. The model uses psychological game theory based on Battigalli and Dufwenberg [

56]. Psychological games, first developed by Geanakoplos et al. [

57], differ from standard games in that an individual’s beliefs directly affects her utility. Using psychological game theory, Rabin [

7] modeled concerns for reciprocity in normal form games and Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger [

8] extended the idea to extensive form games. Reciprocity is captured by the idea that people like to be kind to people who are kind to them and be unkind to people who are unkind to them.

Formally, let

be the set of players. Denote nature as player

Let

H be the set of histories that lead to subgames. Each player

has a set of possible strategies

. The strategy set is

. Each strategy

gives a probability distribution on the possible choices of player

i at each history

. Each player

updated strategy is defined as

.

6 The probability distribution for the behavioral strategy of the chance player is defined as

which is commonly known to both players. Given end node payoffs, the expected material payoff for each player

is

.

Following Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger [

8] and Sebald [

58], additional notation must be introduced as it is necessary to keep track of first and second order beliefs. Each player

i has a set of beliefs,

, about the strategy of player

j. Let

be the belief player

i has about the strategy of player

j. Let

define the set of beliefs player

i has about the belief player

j has about player

strategy. Define

as the belief player

i has about the belief player

j has about player

strategy. To capture the main features of reciprocity beliefs need to be updated as the game progresses. Let

and

represent the updated beliefs at history

h. The utility for player

i is defined as follows:

where

.

In A.1,

utility depends on

own payoff plus concerns for reciprocity. The weight that

i places on reciprocity concerns is captured by

. The function

is a measure of the kindness of

i towards

j at history

h, and

is

belief about the kindness of

j towards

i at history

h. The kindness of player

i towards player

j is represented as a function of player

strategy choice

and belief

At a specific

and

the kindness of player

i is captured by the payoff that player

j gets minus an equitable payoff. The kindness function is defined as:

Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger [

8] calculate the equitable payoff for player

j by finding the

that gives player

j the highest possible payoff and finding the

that gives player

j the lowest possible payoff. The equitable payoff is an average of the payoffs for player

j evaluated at each

. This equitable payoff is:

where

, defined by Dufwenberg and Kirchsteiger [

8], is the set of efficient strategies for player

i such that

Player

belief about the kindness of player

j towards player

i has a similar structure and is defined as

7:

The equilibrium concept used in this paper is the sequential reciprocity equilibrium [

8,

58]. Define for all

and history

, let

be the set of behavioral strategies for each player

i that give the same choices as the strategy

for all histories other than

h.

Definition A1. The profile is a sequential reciprocity equilibrium (SRE) if for all and for each history the following properties hold:

(i) where

(ii) for all

(iii) for all

Property (i) means that at history h, player i chooses a strategy profile that maximizes utility given belief. In addition, it assures that player i follows the equilibrium strategy at all other histories. At the initial history, properties (ii) and (iii) imply that initial beliefs are correct. Property (i) adds that any sequence of choices that lead to a history have probability one. As a result, the SRE concept requires that in equilibrium beliefs be correct.

Proposition A2. Under perfect information and if , then in any SRE the potential behavior for player 2 can be described as follows:

- (a)

If , and , then player 2 will cooperate if player 1 cooperates and defect if player 1 defects.

- (b)

, then player 2 will always defect.

Proof. Player 2 can choose to cooperate or defect at each node

labeled in

Figure 1. Let player 1’s belief about what player 2 will choose at each node be defined as:

,

,

, and

. Player 2’s belief about player 1’s belief about what player 2 will choose at each node is defined as the expectation of player 1’s beliefs about player 2. This gives:

,

,

, and

. Player 1 can choose to cooperate or defect at node

. Let player 2’s belief that player 1 will cooperate be

. Player 1’s belief about player 2’s belief that player 1 will cooperate is defined as

. The game can now be analyzed as a psychological game with reciprocity.

If player 1 cooperates, then player 2’s belief about the the kindness of player 1 towards player 2 is . If player 1 defects, then . In any SRE player 2 will always make the same decision at history and . To see why, note that for player 2 to defect at it must be that . In order for the second mover to defect at it must be that . As a result, in any SRE it must be the case that . Similarly, in any SRE player 2 will always make the same decision at history and .

If (a) holds in equilibrium, then and . If player 1 cooperates, then . At player 2 will cooperate if . This holds if and . At , player 2 will cooperate if . This holds if and . Since , then in order for player 2 to cooperate in pure strategies at it must be the case that . For player 2 to defect at , then the following must hold . Since , then player 2 will defect at . As a result, if , and , then player 2 will cooperate if player 1 cooperates and defect if player 1 defects.

For (b) it must be the case that . If player 1 cooperates, then . At player 2 will defect if . This holds if . At player 2 will defect if which holds if . At player 2 will defect if . As a result, if , then player 2 will always defect. □

Proposition A3. Under imperfect information and if , then in any SRE the potential behavior for player 2 can be described as follows:

Proof. Let player 1’s belief about what player 2 will choose at each information set be defined as: , and . Player 2’s belief about player 1’s belief about what player 2 will choose at each information set is defined as the expectation of player 1’s beliefs about player 2. This gives: , and . Player 1 can choose to cooperate or defect at node . Let player 2’s belief that player 1 will cooperate be . Player 1’s belief about player 2’s belief that player 1 will cooperate is defined as .

Player 2 only observes the results of nature. Player 2’s evaluation of the kindness of player 1 depends on the belief about what node she is currently at. If player 2 observes cooperation, then the probability that player 2 believes she is at node is via Bayes rule. Similarly, . If player 2 observes defection, then and . Since the SRE concept requires that initial beliefs be correct, it follows that player 2 knows in equilibrium what player 1 chooses.

Player 2’s belief about the kindness of player 1 is . No matter the history, the kindness of player 2 towards player 1 will always be if player 2 cooperates and if player 2 defects.

Suppose that in equilibrium player 1 cooperates, then player 2 knows this. Since , player 2 knows that if nature cooperates then she is at node and if nature defects then she is at node . If nature cooperates, then player 2 will cooperate if . If nature defects, then player 2 will cooperate if . As a result, player 2 will make the same decision at nodes and . Similarly, if in equilibrium player 1 defects, . In this case, player 2 will make the same decision at nodes and .

For 1(a), . This is possible if . If , then player 1 will cooperate no matter the results of nature.

For 1(c), . This is possible if both . If , then player 2 will always defect.

For 2, . This is possible if , which holds for all . As a result, if player 1 defects, then player 2 will defect. □

Appendix A.3. Mixed-Concerns Model

In this section, I introduce the mixed-concerns model that combines the models of inequity aversion [

6] and reciprocity [

8] into a single framework. Let the utility of an individual

i be defined as:

where

and

. In Equation (

A6),

utility depends on

own payoff plus concerns for reciprocity and inequity aversion. The weight that

i places on these social preferences is captured by

. An additional parameter,

, is the relative weight placed on concerns for reciprocity and distribution. Higher values of

mean that person

i places a lower weight on reciprocity and greater weight on distributional concerns.

The function

captures the distributional concerns of an individual.

is assumed to be a modified version of inequity aversion defined as:

where

and

.

8 The functional form for

does not capture the idea from the inequity aversion model that people might dislike getting less than another person more than they feel bad about getting more. This could easily be incorporated into the model, but has been left out for simplicity.

9The function is a measure of the kindness of i towards j at history h, and is belief about the kindness of j towards i at history h. Both and have the same functional form described in the previous section. Since the focus is on sequential games, the analysis uses the sequential reciprocity equilibrium as it allows beliefs to be updated.

One advantage of the mixed-concerns model compared to other models that combine concerns for intentions and outcomes [

10,

11], is that chance players are incorporated into the model. Chance players are often used in theoretical models to capture many different environments and random devices are often used in experiments. The mixed-concerns model can make equilibrium predictions in these situations. In addition, the model allows us to investigate how changes in the distribution of the choices by chance players influences equilibrium predictions.

Appendix A.3.1. Perfect Information

The main focus on this analysis will be on what player 2 chooses to do in the game with perfect information. In any SRE, the potential behavior for player 2 is described in Proposition 1.

Proposition A4. If , then in any SRE the potential behavior for player 2 can be described as follows:

- (a)

If , , and , then player 2 will cooperate if player 1 cooperates and defect if player 1 defects.

- (b)

If , , and , then player 2 will cooperate if player 1 and nature cooperates, and defect otherwise.

- (c)

If and , then player 2 will cooperate if nature cooperates and defect if nature defects.

- (d)

Ifand, orand, then player 2 will always defect.

Proof. Player 2 can choose to cooperate or defect at each node

labeled in

Figure 1. Let player 1’s belief about what player 2 will choose at each node be defined as:

,

,

, and

. Player 2’s belief about player 1’s belief about what player 2 will choose at each node is defined as the expectation of player 1’s beliefs about player 2. This gives:

,

,

, and

. Player 1 can choose to cooperate or defect at node

. Let player 2’s belief that player 1 will cooperate be

. Player 1’s belief about player 2’s belief that player 1 will cooperate is defined as

. The game can now be analyzed as a psychological game with mixed concerns.

If player 1 cooperates, then player 2’s belief about the the kindness of player 1 towards player 2 is . If player 1 defects, then . In any SRE player 2 will always defect at history . To see why, note that for player 2 to defect at it must be that . This holds if and . As a result, in any SRE it must be the case that . In addition, player 2 will not cooperate at both and . In order for cooperate to hold at both of those nodes, it would have to be that and which cannot occur. As a result, an equilibrium where player 2 cooperates at both and can be ruled out.

If (a) holds in equilibrium, then and . If player 1 cooperates, then . At player 2 will cooperate if , where if player 2 cooperates and if player 2 defects. This holds if and . At , player 2 will cooperate if . This holds if , and . Since , then in order for player 2 to cooperate in pure strategies at it must be the case that . Since player 2 cooperated at , then it must be the case that player 2 defects at . For player 2 to defect at , then the following must hold . Since , then player 2 will defect at . As a result, if , , and , then player 2 will cooperate if player 1 cooperates and defect if player 1 defects.

For (b), in equilibrium it must be the case that and . If player 1 cooperates, then . At player 2 will cooperate if . This holds if and . At player 2 will defect if . This holds if and . Since , in order for player 2 to defect at , then it must be the case that . In order for player 2 to defect at , then it must be the case that . This holds if and . As a result, if , , , then player 2 will cooperate if player 1 and nature cooperates and defect otherwise.

For (c), in equilibrium beliefs must be correct, which gives and . If player 1 cooperates, then . At player 2 will cooperate if . This holds if and . Player 2 will defect at if . This holds if and . Player 2 will cooperate at if . This will hold if and . Since , and , then in order to have this equilibrium it must be the case that . So if , and t, then player 2 will cooperate if nature cooperates and defect if nature defects.

For (d) it must be the case that . If player 1 cooperates, then . At player 2 will defect if . This holds if and . At player 2 will defect if which holds if and or if and . At player 2 will defect if . This holds if and or if and . If , then . If , then . Given this, it follows that if , and , then player 2 will always defect. If and , then player 2 will always defect. □

Concerns for only reciprocity [

8] or only inequity aversion [

6] arise as special cases. In order to understand the differences between the models of reciprocity and inequity aversion assume that

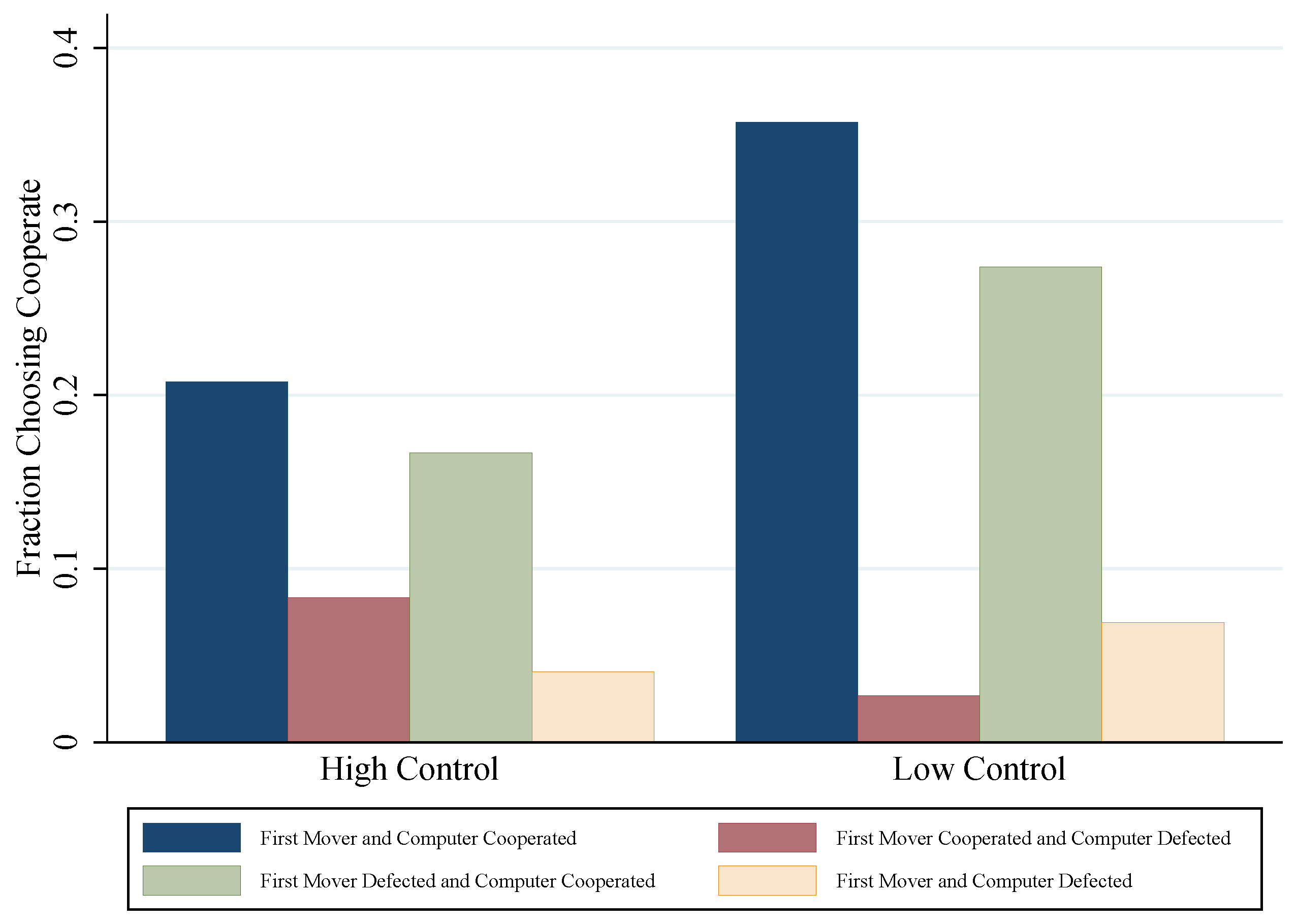

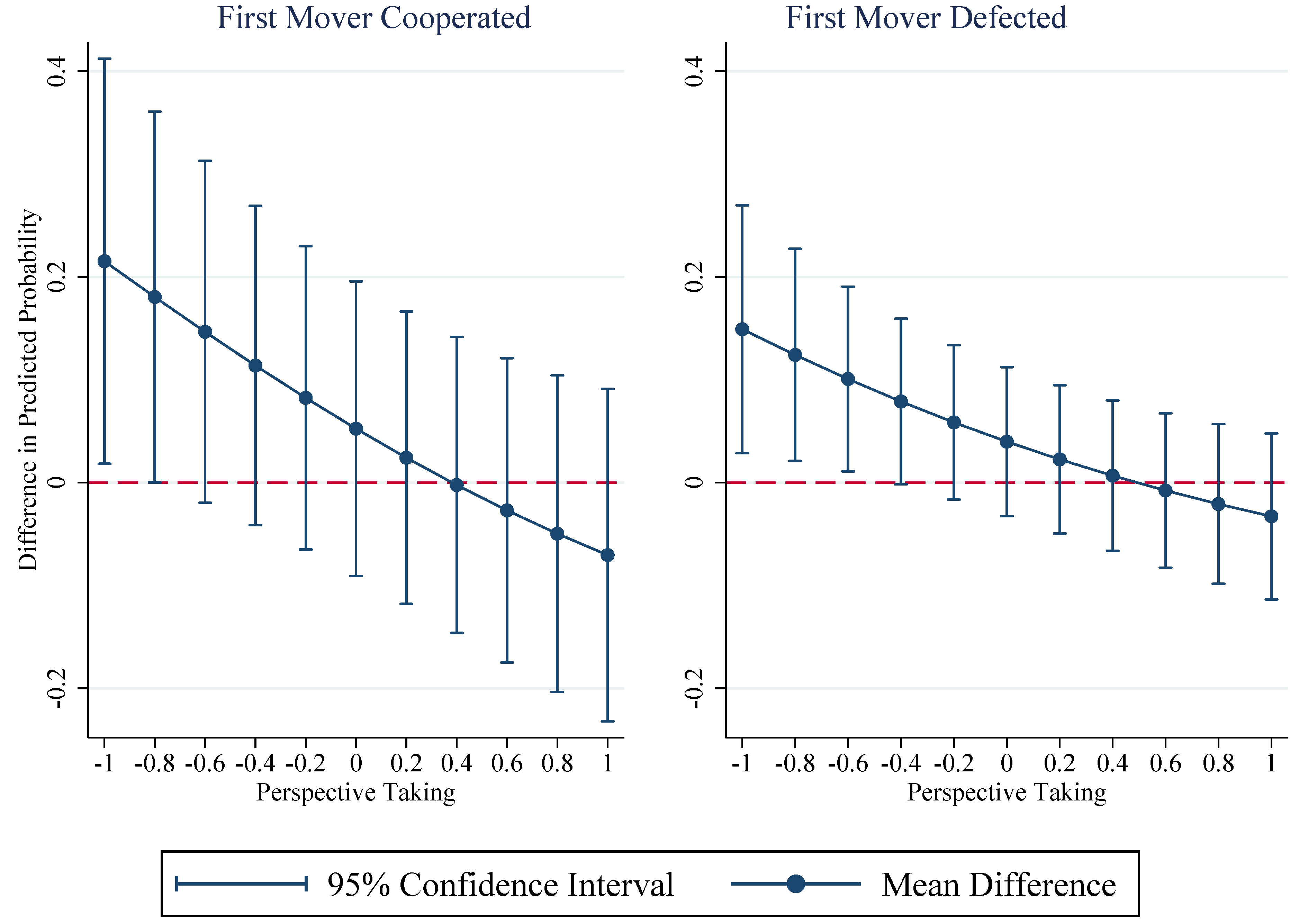

. In other words, assume that players are purely reciprocal. As a result of Proposition 1, if player 1 cooperates, then player 2 will cooperate if

and

. This implies that conditional cooperation by player 2 is only possible provided that player 1’s control is sufficiently high. If

, then player 2 will not cooperate in pure strategies if player 1 cooperates. For player 2 to interpret a choice by player 1 as kind or unkind, player 1 has to have a certain amount of control over that choice. This model suggests that when control is low, reciprocity is not sufficient to maintain cooperation by player 2. Note that as

decreases, then

must be lower in order to sustain defection as a pure strategy SRE. In other words, as control by player 1 increases, lower concerns for reciprocity are needed for player 2 to always defect.

If players are only inequity averse, then this implies that . As result of Proposition 1, inequity aversion predicts that player 2’s choice is not influenced by the values of . The intended choice of player 1 does not influence what player 2 will choose. Player 2’s choice depends only on the degree to which player 2 dislikes getting more than player 1. Cooperation by player 2 is determined by whether player 2 feels “guilty” over receiving more than player 1. If , then player 2 will cooperate if nature cooperates regardless of player 1’s choice. That is, the intended choice by player 1 is not behaviorally relevant. This contrasts with the pure reciprocity case in which player 1’s intended choice matters for player 2 rather than the results of nature.

If players instead have mixed concerns about reciprocity and inequity aversion, then there are four possible pure strategy equilibria that could hold. If the equilibrium (a) occurs, then player 2 is more concerned about player 1’s intentions. This leads to reciprocal behavior where player 2 cooperates if player 1 cooperates and defects if player 1 defects. Provided player 1 has a sufficient level of control over the outcome, this equilibrium is possible. Notice that this equilibrium depends upon player 2’s concern for inequity aversion. Lower values of suggest that player 2 is more reciprocal; however, if is large, then this equilibrium may not occur due to the strong preference for equal outcomes.

The mixed concerns model also suggests another possible equilibrium (b). Here player 2 cooperates if player 1 and nature cooperates, but defects at all other histories. This equilibrium is not possible in the cases of pure reciprocity or pure inequity aversion. In this equilibrium, player 2 cooperates only if player 1 intended to cooperate and the result of that intention leads to cooperation. Intentions are not enough for player 2 to cooperate when player 1 cooperates and nature defects. In addition, if the concern about inequity aversion is sufficiently small, then player 2 will not cooperate if player 1 defects and nature cooperates. Here player 2 may be concerned about both intentions and the distribution of outcomes, but cooperation is only sustained when those concerns align.

The equilibrium (c) occurs if players are strongly inequity aversion averse. One thing to notice is that this equilibrium has no restrictions on the value of other than the assumption that . Since the mixed concerns model allows inequity aversion and reciprocity, player 2 must have a sufficiently high concern for inequity aversion in order for (3) to hold. One interesting result is that as the value of increases, this equilibrium holds for smaller values of . This result makes intuitive sense. To see why, suppose that player 2 is really concerned about reciprocity. When player 1 has little control, player 1’s choice is not seen as very intentional. Consequently, reciprocity has little weight in player 2’s decision. As a result, inequity aversion can become more important as first mover control decreases. Since reciprocity is not much of a factor when control is low, concerns for reciprocity do not conflict as much with concerns for inequity aversion at nodes and .

The equilibrium (d) gives the case when player 2 will always defect. If , then the model is just the self-interest model and player 2 will always defect. If , then the minimum value of that will lead to player 2 always defecting depends on the relative weight they place on the two concerns and the reversal probability.

Appendix A.3.2. Imperfect Information

In the imperfect information game, player 2 does not know what player 1 chose but does know the results of nature. In any SRE, the potential behavior for player 2 is described in Proposition 2.

Proposition A5. If , then in any SRE the potential behavior for player 2 can be described as follows:

If player 1 cooperates

- (a)

If and or and, then player 2 will cooperate if nature cooperates and defect if nature defects.

- (b)

If and , then player 2 will always cooperate.

- (c)

If and , then player 2 will always defect.

If player 1 defects

- (a)

If and , then player 2 will cooperate if nature cooperates and defect if nature defects.

- (b)

If and or and , then player 2 will always defect.

Proof. Let player 1’s belief about what player 2 will choose at each information set be defined as: , and . Player 2’s belief about player 1’s belief about what player 2 will choose at each information set is defined as the expectation of player 1’s beliefs about player 2. This gives: , and . Player 1 can choose to cooperate or defect at node . Let player 2’s belief that player 1 will cooperate be . Player 1’s belief about player 2’s belief that player 1 will cooperate is defined as .

Player 2 only observes the results of nature. Player 2’s evaluation of the kindness of player 1 depends on the belief about what node she is currently at. If player 2 observes cooperation, then the probability that player 2 believes she is at node is via Bayes rule. Similarly, . If player 2 observes defection, then and . Since the SRE concept requires that initial beliefs be correct, it follows that player 2 knows in equilibrium what player 1 chooses.

Player 2’s belief about the kindness of player 1 is . No matter the history, the kindness of player 2 towards player 1 will always be if player 2 cooperates and if player 2 defects. If at nodes and , then if player 2 defects and zero otherwise. If at nodes and , then if player 1 cooperates and is equal to zero otherwise.

Suppose that in equilibrium player 1 cooperates, then player 2 knows this. Since , player 2 knows that if nature cooperates then she is at node and if nature defects then she is at node . If nature cooperates, then player 2 will cooperate if . If nature defects, then player 2 will cooperate if .

For 1(a), and . For this to be an equilibrium it must be that and . This hold under two conditions. In the first case, if , and , then player 2 will cooperate if nature cooperates and defect if nature defects. In the second case, if and , then player 2 will cooperate if nature cooperates and defect if nature defects.

For 1(b), . This is possible if and . If and , then both conditions will be satisfied. Player 1 will cooperate no matter the results of nature.

For 1(c), . This is possible if both and . If and , then player 2 will always defect.

If player 1 defects, then player 2’s belief about the kindness of player 1 is . For 2(a), and . This implies that and . These conditions will hold if and .

For 2(b), . This is possible if both and . These conditions will hold if and or and . □

To understand the equilibrium predictions when players are purely reciprocal, assume that . With pure reciprocity, player 2 ignores the results of nature. As a consequence, player 2 will choose to cooperate based on the equilibrium beliefs about what player 1 chose. If player 1 cooperates with probability one, then player 1 is being kind towards player 2. Even if player 2 observes defection by nature, player 2 knows that player 1 cooperated and player 1 is still viewed as kind.

The control that player 1 has still matters. When player 1 has more control, the value of needed for player 2 to cooperate can be smaller all other things equal. This suggests that cooperation should be higher when player 1 has more control. Notice however that cooperation in pure strategies is still possible even when control is low. This differs from the perfect information game.

If players are purely inequity averse, then . The equilibrium predictions for a player 2 with pure inequity aversion are the same for the perfect or imperfect information games. This makes sense because inequity aversion is only outcome based, and player 1’s intended choice does not influence player 2’s fairness judgments.

With mixed concerns, the potential equilibrium in 1(a) gives that player 2 will cooperate if nature cooperates and defect if nature defects. This equilibrium can occur if player 2 is strongly concerned about inequity aversion. Notice, however, that the equilibrium is also possible for a player 2 that cares a great deal about reciprocity. For certain ranges of , a player that is highly reciprocal will behave as if they are concerned about inequity aversion. This suggests that as control changes the types that players appear to be could change as well. As a result, it is possible that some players could behave inequity averse, self-interested, or reciprocal depending upon player 1’s level of control. In 1(b), player 2 will cooperate regardless of nature’s choice. In equilibrium, player 2 knows that player 1 cooperated and cooperation by player 1 is viewed as kind. This kindness is enough for players that are highly concerned about reciprocity to cooperate even if nature defects.

There are a large number of potential equilibria that can occur for player 1 due to self-fulfilling expectations. The focus of this paper on second mover behavior. In the interest of space, equilibrium predictions for player 1 are available upon request.

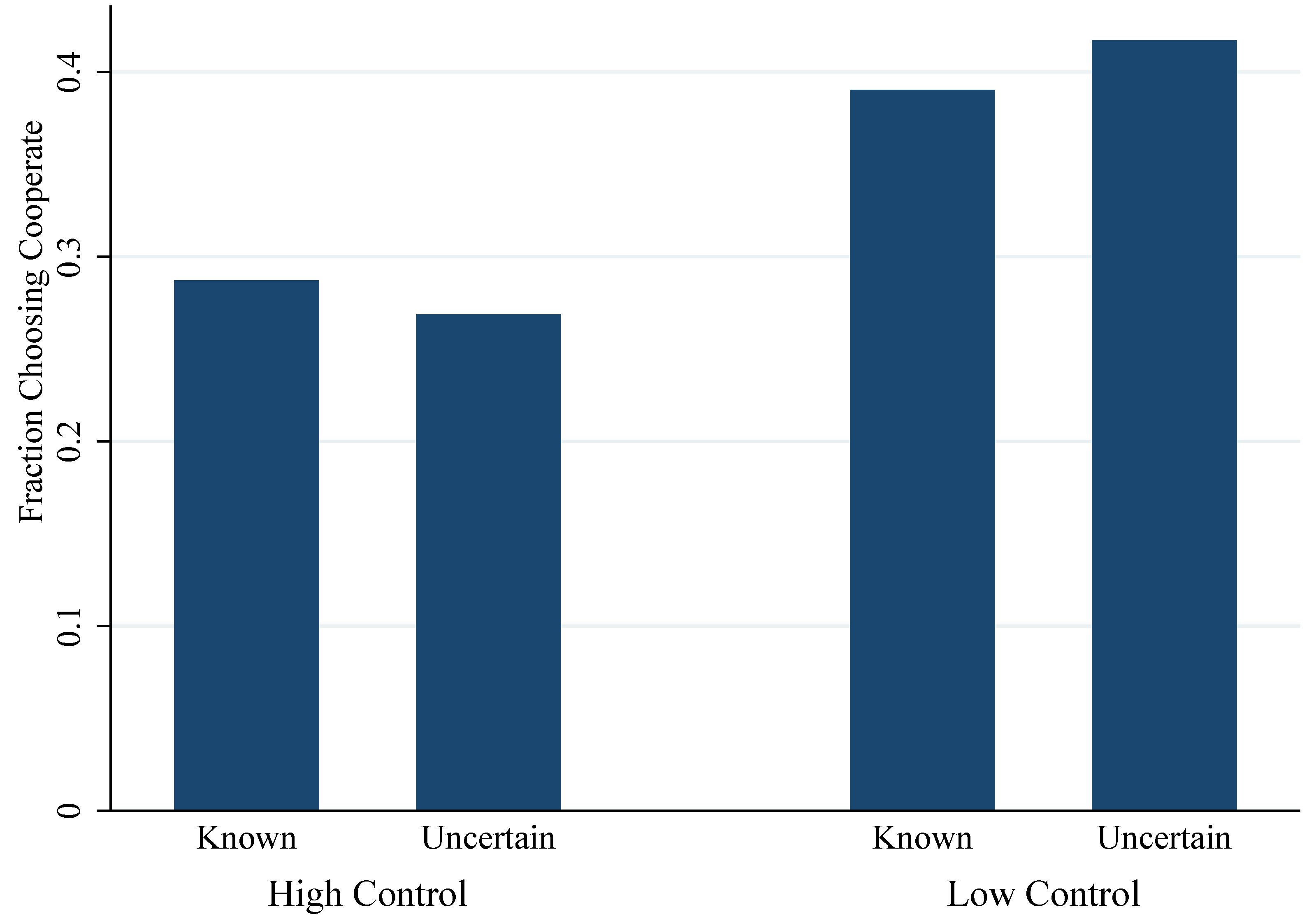

Appendix A.3.3. Perfect Versus Imperfect Information

Both the perfect and imperfect information games can be used to test the predictions of the fairness models explored in this paper. Predictions from pure self-interest and pure inequity aversion are the same no matter the information. As a result of these models, changes in the information about what player 1 chose should not be relevant for equilibrium behavior.

With pure reciprocity, equilibrium behavior could differ depending upon the information available to player 2. In the perfect information game, pure strategy cooperation by player 2 only occurs if control is high. However, in the imperfect information game, cooperation is still possible when control is low. Even when control is high, the concern for reciprocity needs to be much higher when information is perfect compared to the imperfect information game in order for cooperation to be possible. As a result, if subjects are motivated by reciprocity, then cooperation should be higher when information is imperfect compared to when the information is perfect.

In the mixed concerns model, when control is high in the perfect information game, it is possible to have an equilibrium in which player 2 cooperates if player 1 cooperates and defects if player 1 defects. However, when control is low this equilibrium no longer exists. This is not the case with the imperfect information game. When control is low it is still possible for player 2 to cooperate if player 1 cooperates and defect if player 1 defects. Even when control is high, the range of values for both and that lead player 2 to cooperate is largest in the imperfect information game. Thus, given that player 1 cooperates, cooperation by player 2 in the imperfect information game should be higher than in the perfect information game.