Abstract

To avoid the dangerous consequences of climate change, humans need to overcome two intertwined conflicts. First, they must deal with an intra-generational conflict that emerges from the allocation of costs of climate change mitigation among different actors of the current generation. Second, they face an inter-generational conflict that stems from the higher costs for long-term mitigation measures, particularly helping future generations, compared to the short-term actions aimed at adapting to the immediate effects of climate change, benefiting mostly the current generation. We devise a novel game to study this multi-level conflict and investigate individuals’ behavior in a lab experiment. We find that, although individuals reach sufficient cooperation levels to avoid adverse consequences for their own generation, they contribute more to cheaper short-term than to costlier long-term measures, to the detriment of future generations. Simple “nudge” interventions, however, may alter this pattern considerably. We find that changing the default contribution level to the inter-generational welfare optimum increases long-term contributions. Moreover, providing individuals with the possibility to commit themselves to inter-generational solidarity leads to an even stronger increase in long-term contributions. Nevertheless, the results also suggest that nudges alone may not be enough to induce inter-generationally optimal contributions.

“Society is indeed a contract. […] not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” [1]

1. Introduction

The earth is facing massive environmental changes due to rising global temperature levels, which are fueled by human-created greenhouse gas emissions. We are already experiencing some adverse consequences of climate change with devastating prospects for future generations if no action is taken. A recent study estimates that 3.3 million premature deaths per year worldwide are due to illnesses linked to outdoor air pollution [2], which is at least partly associated with greenhouse gas emissions. This number is expected to double by 2050. Climate change has also been linked to human conflict, for example, water availability and extreme temperatures are associated with political conflicts in low-income contexts [3]. Additionally, global warming is expected to cause massive social costs due to ecological and economic losses in the not-so-far future, for example, rising sea levels and flooding of coastal urban areas or extreme weather events such as more frequent and stronger hurricanes. Furthermore, climate change will accelerate desertification [4], threatening food security and leading to migration. Finally, climate change is also massively disturbing different eco-systems, for example, in the Arctic and coral reefs, leading to the extinction of species.

To avoid the deterioration of the adverse consequences of climate change, it is necessary to limit the global average temperature increase to less than 2 °C above its preindustrial value, which requires an estimated 40–70% reduction of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 [5]. To not miss this target, fast and tremendous behavioral transformations at all levels–global, national, as well as individual efforts–are needed. As Nicolas Stern, a renowned scholar of the economics of climate change puts it: “We can take the opportunity, or we can lose it.” [6]. Indeed, individuals can make a difference, either through their behavior or by supporting political agents who are advancing programs of climate change mitigation. Hence, it is of utmost importance to better understand and promote individual efforts toward mitigating climate change. Understanding individual engagement in climate change mitigation requires the analysis of a complex social conflict with two layers. While one layer concerns the struggle within the current generation, the other layer addresses the tension between the current generation and future generations.

The intra-generational conflict is characterized by the collision of individual and collective interests. The collective interest requires that at least sufficiently many of us bear the relatively high individual costs of efforts related to climate change mitigation, e.g., buying ecologically superior “green” products instead of purchasing standard products. The outcomes of such environmental efforts, however, are shared collectively among all, irrespective of their personal efforts. This creates a public good dilemma in which people may free ride on others’ contributions [7]. Particularly in the context of climate change, free riding can be extremely dangerous because of so-called “tipping points”. Crossing a tipping point is supposed to unleash unrecoverable detrimental effects on the earth’s climate and life on earth [8]. Hence, if collective efforts of climate change mitigation do not meet certain thresholds, all humans face the risk of irreversible losses due to dramatic environmental changes [9,10,11].

In addition, climate change poses an inter-generational conflict, as individuals’ behaviors today will have positive or negative externalities on the members of future generations [12,13,14,15,16]. People of the current generation may act to avoid the detrimental effects for themselves only, by investing in short-term measures which exclusively or primarily protect the current generation while having little or no protective effect on future generations. Alternatively, the current generation could also support more costly long-term measures that protect themselves and future generations from adverse consequences of climate change. For instance, efforts to promote improvements of existing technologies aimed at reducing fossil fuel consumption may be considered a short-term measure, which delays the ultimate solution to the problem, i.e., moving away from fossil fuels altogether. In contrast, contributions to promote novel technologies based on renewable energies constitute a long-term measure. Both short-term and long-term measures of climate change mitigation may be promoted or hindered by collective regulations and individual behaviors, e.g., consumption behavior.

Previous research has focused on the obstacles and potential solutions to the intra-generational or the inter-generational conflict of climate change mitigation separately. Our first contribution to the literature is that we introduce a novel economic game that models individual efforts toward climate change mitigation, taking into account both conflict layers at the same time. That is, individuals must decide about costly short-term and even more costly long-term contributions, affecting both their own and future generations’ outcomes. In our laboratory experiment, we find that although individuals’ contributions suffice to avoid any adverse consequences of climate change for their own generation, short-term contributions exceed long-term contributions, leading to negative externalities for subsequent generations. Consequently, future generations have worse “starting conditions” and, in turn, have to make greater efforts to avoid the adverse consequences of climate change themselves.

As a second contribution to the literature, we experimentally test different interventions aimed at improving individuals’ long-term contributions. Specifically, we build on the concept of behavioral “nudges” [17]. In this context, we rely on “green nudges” as non-coercive and rather low-cost variations of the choice architecture, which aim to increase long-term contributions to climate change mitigation without affecting the decision-makers’ economic incentives [18], for a conceptual overview, see [19]. We find that changing the default contribution to the long-term, inter-generationally optimal contribution level, and additionally providing visual feedback about the own contribution’s externalities, reduces the difference between short-term and long-term contributions. We also find that giving individuals the possibility to self-commit to inter-generational solidarity–in addition to the default nudge–further increases long-term contributions, by up to 50% more than in the baseline setting. Hence, simple changes to the choice architecture help to reconcile the individual conflict between short-term and long-term contributions to climate change mitigation.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we introduce a novel multi-level conflict game of climate change mitigation. In Section 3, we provide a nuanced overview of the related literature, and in Section 4, we develop our hypotheses. The experimental procedures are described in Section 5. Results are presented in Section 6, and Section 7 discusses and provides implications for climate change mitigation.

2. A Game of Multi-Level Conflict in Climate Change Mitigation

We devise a game that captures both the intra- and inter-generational conflict in climate change mitigation. We model the intra-generational conflict of climate change mitigation as a public good game with collective risk [10], capturing the risk of severe adverse consequences associated with going beyond tipping points that are inherent to climate change. We model the inter-generational conflict such that a generation’s joint long-term contributions to climate change mitigation affect the capacity of the following generation to avoid adverse consequences for themselves.

2.1. Players and Generations

There are n > 1 players in each generation. Each player i in the generation Gt is endowed with ei tokens and may contribute any integer number of tokens si to a short-term pool (short-term measures to mitigate climate change), and li tokens to a long-term pool (long-term measures), with 0 ≤ si ≤ li ≤ ei. Each token contributed to the short-term pool is multiplied by the productivity factor σ, and the return is distributed evenly among all players of Gt. Each token contributed to the long-term pool is multiplied by the productivity factor λ, and the return is distributed evenly among all players of Gt. Parameters σ and λ are set such that 1 < λ < σ < n, reflecting the characteristics of a social dilemma, for both the short-term and the long-term pool.

2.2. Intra-Generational Conflict

Let Et = nei be the sum of endowments in generation Gt. Let St and Lt be the sum of all tokens contributed to the short-term and the long-term pools by that generation, respectively. To capture the risks associated with tipping points, we define an absolute threshold contribution level T, with T < Et. This threshold is public information and is identical for all generations. If the sum of all contributions of generation Gt is lower than this threshold, i.e., St + Lt < T, then with probability p, the game will terminate after Gt. In this case, all players from generation Gt and all future generations will lose their earnings and endowments. Note, again, that it does not matter for whether the game will terminate or not if the threshold is reached by contributions to the short-term or long-term pool (or any combination of both).

Each subsequent generation, if it ever comes to play, faces the same game structure as described above. The payoff function for a player i in generation t is as follows:

2.3. Inter-Generational Conflict

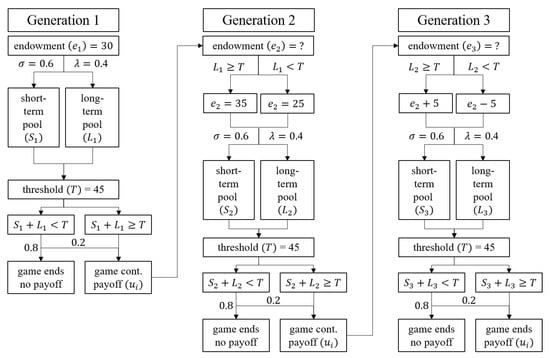

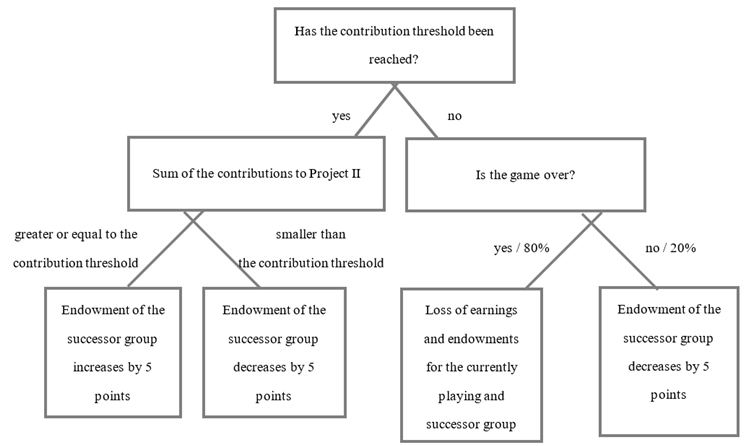

The capacity of the current generation to avoid termination of the game depends on their predecessors’ contributions to the long-term pool. If the players of Gt do not invest enough in the long-term pool, i.e., if Lt < T, then the endowment of each i player ei,t+1 of generation Gt+1 decreases by z units to ei,t+1 = ei,t − z. If, however, the players of Gt reach or pass the contribution threshold, i.e., Lt ≥ T, then the endowment of each i player ei,t+1 of generation Gt+1 increases by z units to ei,t+1 = ei,t + z. Note that the level of short-term contributions does neither increase nor decrease the endowment of the subsequent generation. Figure 1 provides a schematic overview of the game structure and its parameters.

Figure 1.

Structure and parameters of the multi-level conflict game in climate change mitigation.

2.4. Game Predictions

In the following stylized game-theoretical analysis, we assume that players have self-centered preferences and are risk-neutral. From the individual perspective, if the fellow players of a player’s own generation do not contribute, it is the best response for each player i to exert no effort either. Hence, mutual non-contribution constitutes a Nash-equilibrium. In addition, for sufficiently high values of p, each combination of players’ contributions that reaches exactly the threshold T constitutes a Nash-equilibrium as well. Considering that the contribution threshold T constitutes a focal point together with a “fair-share” contribution norm, one could expect an individual contribution of T/n. For any player i in any generation Gt, to prevent the termination of the game, contributions to the short-term pool are less costly but equally effective as efforts made toward the long-term pool. Hence, from the individual perspective, long-term contributions are dominated by short-term contributions. In other words, there are no monetary incentives to contribute to the long-term pool.

The intra-generational social optimum is as follows: From the perspective of generation Gt, the welfare is maximized if all players fully contribute to the short-term pool as σ > λ > 1.

The inter-generational social optimum is as follows: Given that generation Gt faces a subsequent generation Gt+1, investing T tokens to the long-term pool and contributing the remainder to the short-term pool is efficient if the cost of contributing to the long-term pool compared to the short-term pool T(λ − σ) is smaller than the loss in endowment nz for players of the subsequent generation Gt+1. Thus, from the inter-generational perspective, welfare is maximized if T(λ − σ) < nz.

In summary, from the own generation’s perspective, short-term contributions are optimal, but individuals have free-riding incentives. Additionally, from the perspective of all individuals, irrespective of the generation they belong to, long-term contributions at the level of T are optimal but are (more) costly for the contributing generation. Taking the simultaneous intra- and inter-generational conflicts together, the game constitutes a multi-level conflict of climate change mitigation.

2.5. Game Parameters

In our experimental game (for details, see below), there are m = 3 generations, each with n = 3 players. The game is played for a single (one-shot) contribution round in each group (although it could also be adapted as a repeated game). The endowment for each player amounts to e = 30; the contribution threshold equals to T = 45 (hence, a fair-share contribution would be 45/3 = 15 per player). The probability of losing all resources if the contributions fall short of the threshold amounts to p = 0.8. The productivity factor of the short-term pool is set to σ = 0.6, and the productivity factor of the long-term pool is set to λ = 0.4.1 These parameters imply that z must be at least 3 in order to render contributions to the long-term pool at the level of T the optimal choice from the inter-generational perspective. We therefore set z = 5.

3. Related Literature

3.1. Conflict Structure of Climate Change Mitigation

Several games have been introduced to model the conflict of climate change adaptation and mitigation, for an overview, see [20]. The collective-risk social dilemma [10] models the intra-generational conflict of climate change mitigation. In this game, players are allocated to groups, and each player receives an endowment. They must independently decide whether to contribute (0 €, 2 €, or 4 €) to a climate fund. Only if players’ joint contributions reach a predefined contribution threshold T will they be paid their non-contributed endowment. If, however, contributions fall short of the threshold, they will lose their non-contributed endowment with a certain probability p.2 Milinski et al. [10] find that contributions to climate change mitigation increase with the probability of losing resources (probability of losing resources was either p = 0.1, p = 0.5, or p = 0.9) if the threshold contribution level is not reached. A follow-up study shows that under endowment asymmetry, the contributions are proportional to the player’s endowment [21]. However, when endowment asymmetry is combined with a greater risk of losing for the “poor” players, overall contributions decrease [22]. Communication may increase the prospects of reaching the contribution threshold under endowment uncertainty because “rich” players can signal the willingness of higher contributions early on [11].

Other games model inter-generational externalities. In a study using a dynamic public good game, where players’ contributions affect other players’ earnings in the next round, and players themselves benefit from others’ contributions in the previous round, too, contributions to the public good are higher compared to the intra-generational “standard” public good treatment [23]. Other experiments using inter-generational common-pool resource dilemmas find substantial heterogeneity in players’ preferences towards benefiting the subsequent generation [12], with substantial inter-generational prosocial behavior–although below the social optimum [14]. Minimum-effort games played in non-overlapping generations show that advice passed through from predecessors may serve as a coordination device to reach efficient outcomes, at least when the advice is made public and becomes common knowledge [24,25]. Jacquet et al. [13] adapt the collective-risk social dilemma in three between-subjects treatments with immediate or delayed payoff of the rewards of cooperation. The payoff was either delayed by one week (short delay) or by several decades (long delay). The difference between immediate payoff and the short delay is interpreted as intra-generational discounting, whereas the difference between immediate payoff and long delay is interpreted as inter-generational discounting. They find that contributions decrease if there is a short delay, and even more so if there is a long delay in payoff. Furthermore, Hauser et al. [15] use a sequential, multi-group collective-risk social dilemma to model inter-generational cooperation. They find increased levels of cooperation, i.e., smaller extraction from the common good, when groups decide democratically how much to extract using median voting [26], which binds all players to the same action.

Because our game considers both the intra-generational and the inter-generational conflict at the same time, it is structurally related to other multi-level conflicts typically studied in the context of inter-group conflict, for an overview, see [27]. The game that is closest to ours is the nested social dilemma [28,29], which models a conflict between local and global public good contribution. Here, players of two (or more) groups decide independently whether to contribute to two independent public goods. One “local” good that only benefits members of the own group and one “global” good that benefits both members of the own and the other group(s) equally. Contributions to the global good are collectively welfare-maximizing, yet, costlier from the individual and the individual’s group perspective (i.e., multiplied by a smaller MPCR than contribution to the local good). In this game, contributions to the local good have been shown to often exceed contributions to the global good [28]. Global contributions increase with players’ collective welfare concerns, e.g., due to greater global social identity [30] or due to a greater level of globalization measured on the individual- or country-level [31]. In the nested social dilemma, as well as in other multi-level conflict games, however, groups play simultaneously and the positive or negative externalities are bidirectional, whereas our game considers a unidirectional effect from the current generation to its successor generation.

3.2. Nudges toward Climate Change Mitigation

In complex decision tasks such as those related to climate change mitigation and characterized by, for instance, several behavioral options, delayed consequences, and limited opportunities to learn from experience, individual choices are likely to be error-prone [32,33,34]. This may cause the well-known attitude-behavior gap [35,36], i.e., attitudes/preferences do not necessarily correspond to the respective utility-maximizing behaviors. Moreover, preferences may not be “hard-wired” but can be formed during decision-making and can be affected by the decision architecture [34]. It has therefore been proposed that simple nudges may provide a non-coercive tool to increase the quality of decisions, e.g., by increasing individual or social welfare or both, in line with individuals’ initial preferences or when individuals have no strong preferences [17].

A prominent example of a nudge is the default effect. It has been shown that individuals are likely to stick with the default option in various domains, for instance, retirement savings [37,38], organ donation [39], environmental behavior [40,41,42], as well as in public good games [43,44].

Another example of a nudge is self-commitment, which serves as a promise to oneself and therefore increases the likelihood of overcoming self-control problems, even when there are no costs associated with deviations from the commitment [45]. Self-commitments have been shown, for instance, to increase charitable giving [46] and healthy behaviors [47].

In the context of economic games on climate change mitigation, we are aware of only a few studies that have investigated an intervention that can be considered a nudge. Using a repeated collective-risk social dilemma, Freytag et al. [48] investigate the effect of information feedback on groups’ likelihood of reaching the final contribution threshold. They find that groups are more likely to reach this threshold if they are informed about contribution “milestones” during repeated play. In another study applying a similar game structure, Tavoni et al. [11] provide participants with the possibility to announce their planned contribution to the other players. These “pledges” are non-binding and can be considered a commitment signaled to oneself and others. Results show that pledges increase subsequent contributions.

In our study, we extend this literature by experimentally investigating the effectiveness of two other simple nudges for promoting long-term contributions to climate change mitigation: the default nudge and the self-commitment nudge, as described above. As such, we test whether the exogenous modification of the choice architecture via (i) different default contributions and (ii) non-binding pledges to oneself affect contribution behavior. Different from Tavoni et al. [11], we do not study pledges to others; therefore, largely excluding social dynamics.

4. Treatments and Hypotheses

In the baseline treatment, we examine individuals’ behavior in the game’s basic form, thus serving as the control condition in our experiment. We provide participants with tokens (experimental currency units), which they might (or might not) contribute to the short-term and the long-term pool. That is, participants had to type in their preferred number of tokens to be allocated to each of the two pools. Tokens not contributed were automatically kept (see Appendix A Figure A1 for the decision screen).

Research using the collective-risk social dilemma [10] shows that groups are more likely to overcome the intra-generational conflict, i.e., reaching the critical contribution threshold, if the risk of dangerous consequences is high (i.e., p = 0.9 vs. low: p = 0.1), as is the case in the present experiment (p = 0.8). In other words, given the perceived risk is sufficiently high, individuals are more likely to coordinate on the efficient Nash equilibrium (i.e., choosing short-term contributions at the level of threshold T), avoiding the equilibrium of mutual non-contribution [49]. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1.

Individuals in the baseline treatment will contribute sufficient amounts in order to reach the critical contribution threshold.

Note that although contributions to the long-term pool are efficient from the collective, i.e., inter-generational, perspective, they are dominated by short-term contributions. In addition, research adapting a similar game structure in order to model an inter-generational conflict suggests that intra-generational cooperation is higher than inter-generational cooperation [13]. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2.

Individuals in the baseline treatment will contribute more to the short-term than to the long-term pool.

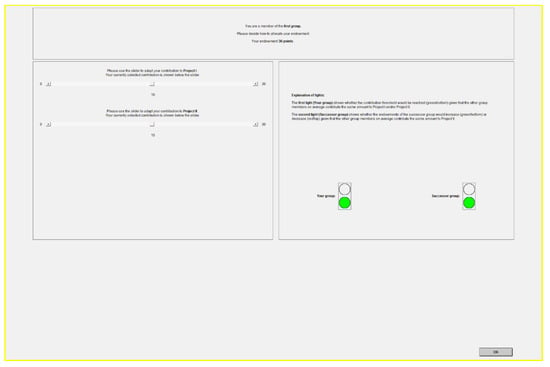

In the default treatment, we implement a default nudge mechanism. Specifically, participants had to make their allocations to the two pools via a slider input scale (see Appendix A Figure A2 for the decision screen). The default positions of the slider input were set at the social welfare optimum, i.e., at the optimal allocation of contributions to the different pools from the inter-generational perspective (15 tokens to the short-term pool and 15 tokens to the long-term pool).

Additionally, there were two feedback lights: The first feedback light was green if the expected overall contribution of the own generation to both pools was equal or above the threshold contribution (assuming that all players of the group would contribute an equal amount), such that the termination of the game could be securely avoided. It switched to red when the expected overall contribution was below the threshold, and players would face the risk of game termination with a likelihood of p = 0.8 (and a potential loss of their earnings). The second feedback light was green if the expected contribution of the own generation to the long-term pool only was equal or above the threshold, such that the subsequent generation’s endowments would increase.3 It switched to red if the expected contribution to the long-term pool was below the threshold and, consequently, the subsequent generation’s endowments would decrease.

Based on previous research showing that individuals are prone to stick with the default option [38,39,43], we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

Individuals in the default treatment will contribute more to the long-term pool than individuals in the baseline treatment.

In the default+commitment treatment, participants faced the same decision screen as participants in the default treatment (see Appendix A Figure A2). In addition, participants saw a self-commitment message before they learned about which generation they would be randomly allocated to. The commitment message read as follows:

Commitment: “I am aware of my responsibility as a member of the current group toward members of subsequent groups. I will not place the interest of my own group above the interests of subsequent groups. Hence, I will act in solidarity toward the members of subsequent groups, so that they do not have to face conditions that are worse than the conditions for my group”.

A disclaimer informed the subjects about the non-binding character of the commitment and the anonymity of their decision.

Note: “Your agreement is non-binding and only reflects your intention. No member of your group or of the other groups will find out whether you accepted or declined”.

Participants could then agree with the self-commitment message or could refuse to do so, i.e., “I accept the commitment/I decline the commitment”.

This commitment mirrors an inter-generational contract as suggested in the introductory quote by Burke [1], see above.4 Previous research has shown that individuals are prone to follow their self-commitment when commitment is costly [45,46,47]. Additionally, the content of the self-commitment message itself may create a moral suasion [50], potentially increasing long-term cooperation behavior. Accordingly, we formulate the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

Individuals in the default+commitment treatment will contribute more to the long-term pool than individuals in the default treatment.

5. Materials and Methods (Experimental Procedures)

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a laboratory experiment, gathering 12 cohorts (independent observations), each with 9 players in 3 generations, for each treatment (overall N = 324 participants). Participants were mainly students, aged 18 to 51 with an average age of 22.4 years, 75.2% of them were female. Participants were registered at the subject pool of a medium-sized German university, and were invited via ORSEE [51] to the experimental sessions, each session with either 9 or 18 participants.5

Once participants arrived at the laboratory, they were randomly seated in cubicles. Participants received written instructions, which included several examples of hypothetical contributions and their payoff consequences (see Appendix B). The instructions were read aloud by the experimenter. Afterward, participants were allowed to ask questions for clarification. The experiment was programmed using z-Tree [52]. Before participants made their contribution decisions, they had to answer some comprehension questions and the experiment only started after all participants had correctly answered the questions. Note that all participants received the same instructions. Particularly, all participants were informed that some generations will have just a successor or a predecessor generation, i.e., the first and third generations, respectively, while the second generation will have both a predecessor and a successor generation. Participants then learned to which generation they were being randomly allocated (first, second, or third). Players of the first generation made their contribution decisions first, followed by the second generation, and the last generation (given that the game would not terminate before). Participants received feedback on the contributions to the short-term and the long-term pool of each generation. Note that the pools and generations were labeled neutrally, i.e., “Pool I”, “Pool II”, and (first, second, third) “Group”, in all treatments. At the end of the experiment, tokens were converted into Euro (10 tokens = 1.50 Euro) and participants were paid in private. An experimental session lasted about one hour, and on average participants earned 14.06 € including a 5 € show-up fee.

6. Results

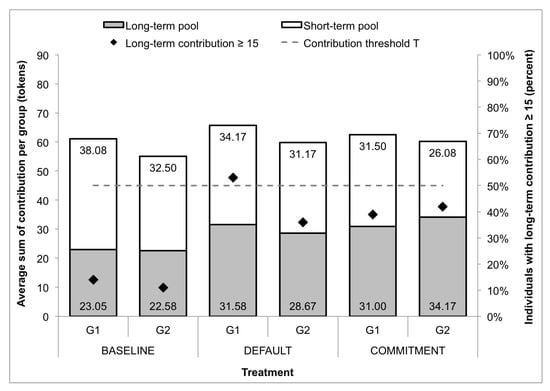

Figure 2 displays, for each generation in each treatment, the average sum of contributions to the short-term and the long-term pool per generation, as well as the share of individuals who contributed at least 15 tokens to the long-term pool. Note that only players of the first and second generations (in what follows: G1 and G2, respectively) have subsequent generation(s) and therefore face an inter-generational conflict. Thus, in the following, we restrict our analyses to participants of G1 and G2.6

Figure 2.

Average sum of contribution to the long-term pool (gray columns; left Y axis), to the short-term pool (white columns; left Y axis), and the contribution threshold T (gray dotted line; left Y axis), as well as individuals with a long-term contribution ≥ 15 (black diamonds; right Y axis) by treatment and generation.

6.1. Contributions in the baseline Treatment

We start by looking at participants’ decisions in the baseline treatment. In G1 and G2, the average sum of contributions is 61.13 (SD = 10.60) and 55.08 (SD = 12.49) tokens, respectively, to either of the pools. Supporting Hypothesis 1, all groups but one managed to meet the critical contribution threshold of T = 45 tokens that prevents termination of the game.

Result 1.

Individuals in the baseline treatment contribute sufficient amounts to reach the critical contribution threshold, and thus the risk of adverse consequences is avoided.

Regarding the question of which pool participants contributed to, the results, however, are less positive. We observe a remarkable gap between the contributions to the pools. In G1, the average sum of contributions to the long-term pool is 38% below the average of those that were contributed to the short-term pool (Wilcoxon-signed-rank (WSR) test; Z = 4.6, p < 0.001), and about 31% in G2 (WSR test; Z = 2.6, p = 0.009). In fact, only 14% of players in G1 and 11% of players in G2 contributed at least 15 tokens to the long-term pool, i.e., the amount necessary to avoid adverse consequences for the subsequent generation, given that all players of the current generation contribute an equal amount. Hence, participants’ contributions in the baseline treatment are largely inefficient in terms of reaching the inter-generational optimum, which supports Hypothesis 2.

Result 2.

Individuals in the baseline treatment contribute more to the short-term than to the long-term pool, leading to negative externalities for the subsequent generation.

6.2. Contributions in the default Treatment

Next, we compare contributions in the default treatment with contributions in the baseline treatment. The average amount of total tokens contributed to either of the two pools does not significantly differ from the baseline treatment, neither in G1 (Mann-Whitney-U (MWU) test; Z = −1.4, p = 0.151) nor in G2 (MWU test; Z = −1.1, p = 0.289). As in the baseline treatment, again, all groups but one contributed sufficiently to reach the contribution threshold.

Supporting Hypothesis 3, contributions to the long-term pool of G1 in the default treatment are on average 8.53 tokens higher than in the baseline treatment, which is a significant increase (MWU test; Z = −4.2, p < 0.001). A similar shift toward long-term contributions can be observed in G2, where we see an increase of 6.09 tokens (MWU test; Z = −3.0, p = 0.003). In fact, the share of individuals who contributed at least 15 tokens to the long-term pool increased in G1 from 14% in baseline to 53% in default (Fisher’s exact (FE) test; p = 0.001), and in G2 from 11% to 36% (FE test; p = 0.012). Moreover, the gap between short-term and long-term contributions is reduced drastically to 8% in both G1 and G2, compared to 38% and 31% in the baseline treatment, respectively (see above). Consequently, the difference between short-term and long-term contributions is not significant in the default treatment, in either generation (WSR tests; G1: Z = 0.9, p = 0.333; G2: Z = 1.2, p = 0.228).

Result 3.

Individuals in the default treatment contribute more to the long-term pool than individuals in the baseline treatment. Hence, the default nudge equalizes long-term and short-term contributions without reducing the overall contribution levels.

6.3. Contributions in the default+commitment Treatment

In the default+commitment treatment, the average amount of total tokens contributed does not significantly differ from the baseline treatment (similarly to the default treatment), either in G1 (MWU test; Z = −0.3, p = 0.751) or in G2 (MWU test; Z = −1.4, p = 0.151). Again, all but one group contributed at least the amount necessary to reach the contribution threshold.

Regarding the allocation of contributions to the short-term vs. long-term pool, the increase in long-term contributions is 7.95 tokens in G1 (MWU test; Z = −3.5, p < 0.001) and 11.59 tokens in G2 (MWU test; Z = −4.8, p < 0.001) compared to the baseline treatment. The share of players in G1 who contributed at least 15 tokens to the long-term pool is significantly larger than the share in the baseline treatment, both in G1 (39% vs. 14%; FE test; p = 0.031) and in G2 (42% vs. 11%; FE test; p = 0.007). In G1, short-term and long-term contributions are not significantly different (WSR test; Z = 0.5, p = 0.653), similarly to the default treatment. In G2, however, long-term contributions are more pronounced: Long-term contributions are about 31% higher than short-term contributions (WSR test; Z = −2.9, p = 0.004), and significantly higher than in G2 of the default treatment (MWU test; Z = −2.4, p = 0.017).

The difference between short-term and long-term contributions is further amplified when we focus only on those players who actually agreed with the commitment statement—a vast majority of 88% of them having done so. There is no significant difference between short-term and long-term contributions among the self-committed players in G1 (WSR test; Z = −0.5, p = 0.647). We find, however, that those who committed themselves to the solidarity statement contributed significantly more to the long-term pool than those who did not (MWU test; Z = 2.2, p = 0.026). Among self-committed players in G2, we find significantly higher contributions to the long-term pool than to the short-term pool (WSR test; Z = −3.3, p < 0.001). In addition, their long-term contributions are higher than those in the default treatment (MWU test; Z = −2.8, p < 0.005).

Result 4.

Individuals of G2 (but not of G1) in the default+commitment treatment contribute more to the long-term pool than individuals in the default treatment. Hence, an additional commitment nudge further increases long-term contributions without reducing the overall contribution levels.

6.4. Regression Analysis

To further explore the effects of the default and the commitment nudge, we estimated multi-level mixed-effects regressions, taking the dependencies within each generation and between the three generations in each group into account. Table 1 reports the regression coefficients. The dependent variable is the individual-level contribution to the long-term pool. We included dummies to indicate whether the default treatment or the default+commitment treatment is implemented. For the default+commitment treatment, we also included a dummy for those players who indeed committed themselves (Committed player). As control variables, we added a dummy for those decisions made by the players of the second generation (Player in G2), and the number of tokens that were available for contributions (Endowment).

Table 1.

Multi-level mixed effects regressions predicting contributions to the long-term pool.

We observe a significant effect of the default treatment and confirm our main finding from the non-parametric tests (Result 3), indicating that the contributions to the long-term pool are higher in the default treatment compared to the Baseline treatment. Moreover, the results indicate that committed players in the default+commitment treatment make significantly higher contributions to the long-term pool than players in the Baseline treatment (supporting Result 4, see above). For non-committed players, we find a negative, although non-significant coefficient. However, a Wald-test for linear hypotheses shows that the joint effect of the default+commitment treatment and the dummy for those who committed themselves (Committed player) is significantly larger than the effect of the default treatment (Chi2 = 4.59, p = 0.032). In other words, there is a positive overall effect of the default+commitment treatment compared to the default treatment, i.e., the higher long-term contributions from the committed players are not canceled out by the lower long-term contributions from the uncommitted players. A second regression that directly compares the default and the default+commitment treatment (see Appendix C Table A1) yields the same result and provides further support for this finding. Lastly, in both regressions the endowment dummy is positive and highly significant, indicating that the reduced endowment limits the potential contributions of individuals in G2. Overall, the regression results confirm the findings from the non-parametric analyses.7

7. Discussion

We contribute to the increasing literature on behavioral dynamics in intra- and inter-generational climate change dilemmas [53,54,55]. In line with previous research on intra-generational conflicts of climate change mitigation [10], our results indicate that individuals are willing to contribute in order to avoid the substantial risks associated with climate change. However, supporting research on the inter-generational conflict of climate change mitigation [13], it seems that the motivation to mitigate the adverse consequences of climate change is bounded to the own generation: In our experiment, players primarily contributed to short-term adaption rather than long-term mitigation.

Our results indicate that nudges are a promising class of interventions to increase long-term climate change mitigation. In our experiment, simple nudges, i.e., a default nudge and the self-commitment nudge, increased long-term contributions by almost 50%. Looked at from a different angle: the share of people who were willing to contribute (at personal cost) sufficient amounts to protect future generations tripled, although our interventions do not change any financial incentives. There are numerous examples of where such interventions could be used in order to change individual behaviors related to climate change, e.g., setting cars with lower CO2 emissions the default option at rental car search websites or asking for commitment of employees to environmentally friendly behaviors in their daily work routine (such as, for instance, duplex printing).

7.1. Limitations and Outlook

We acknowledge that the difference between the effectiveness of short-term and long-term contributions with regard to climate change mitigation often materializes over a much longer time horizon. For example, several generations might be able to use technologies based on fossil fuel (e.g., by developing more efficient technologies both in terms of harvesting and use), but this will only delay the point at which fossil fuels are depleted eventually. Hence, our game should be seen as a conceptual model for inter-generational conflicts that may also emerge between different cohorts of (several) generations, e.g., people living now and in the close future vs. people living in the more distant future.

A somewhat related issue with regard to the (limited) external validity of our game is the fact that we assume a strictly positive effect of long-term contributions on the successor generation’s welfare. Although this may be true for merely climate-related utility, there are certainly other utility aspects which may not always lead to a positive but even to a negative effect (e.g., decreased economic growth). Future research could implement such parameters into the devised game structure.

We also want to emphasize that our experiment was not designed to identify and disentangle different psychological processes potentially underlying the increased level of long-term contributions in the default and the default+commitment treatments. For instance, the default treatment differed from the baseline treatment not only by displaying a default contribution but also in the presentation of feedback lights, both of which may have affected contribution decisions. In a similar vein, the self-commitment message might have increased the salience of moral concerns or collective (inter-generational) identification, which could have increased long-term contributions independent from the commitment itself. Our aim was to test whether such behavioral nudge interventions are able to increase long-term contributions in an economic game setting with financial incentives. We find that (a combination of) behavioral insights can considerably change individually costly contribution behavior but admit some ambiguity regarding (differentiation of) the underlying socio-cognitive processes.

Despite these considerable changes due to simple and low-cost nudges, note that the behavioral changes in our game did not suffice to avoid the negative consequences for the following generations. Although other experimental parameters might have yielded more favorable outcomes, we do not claim that nudges are the “magic bullet” to mitigate the adverse consequences of climate change. Rather, a combination of nudges and incentives is likely to be most successful. However, we propose that nudges could be an important first step to pave the way for arguably more difficult-to-implement changes of incentives. As recent history has shown, coercive measures such as taxes on carbon emissions likely receive strenuous opposition by industrial stakeholders. Nudges, in contrast, are more likely to be accepted and could lead to more rapid (yet, smaller) changes in customers’ preferences. Once citizens’ preferences and behaviors change, it is more likely that the market will follow, e.g., more electricity from renewable energies will be available when consumers’ demand of “green” energy increases in the first place. Therefore, we argue that nudges could set an important precondition for potentially more effective policy measures.

7.2. Conclusions

We introduce a novel experimental game of climate change mitigation, integrating both the intra-generational and the inter-generational conflict at the same time. We find that simple nudges based on behavioral insights increase individual contributions to long-term climate change mitigation. Future research should use and adapt the game to study further economic and psychological factors that determine the individuals’ willingness to mitigate the negative consequences of climate change —not only for themselves but also for future generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B., Ö.G. and T.L.; investigation, R.B. and T.L.; data curation, T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.B.; writing—review and editing, R.B., Ö.G. and T.L.; visualization, R.B. and T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the “Excellence Initiative” (ZUK II) of the German Research Foundation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants of the ESA meeting 2016 in Jerusalem and Astrid Dannenberg for helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

baseline Treatment.

Figure A2.

Default and default+commitment Treatment.

Appendix B

Instructions for the Experiment

Original instructions were provided in German. They are available from the authors upon request.

General Information

We welcome you to this economics experiment. It is very important that you read the following information carefully. If you have a question, please raise your hand. We will then answer your question privately.

In this experiment, you can earn money. The exact amount depends on your decisions and on the decisions of other participants. Your total income from the experiment consists of two parts:

- Participation fee: Each participant in this experiment will receive 5 Euros. This remuneration is independent of the decisions and the earnings of the experiment.

- Earnings from the experiment: During the experiment, your income is first calculated in points. The total number of points that you score during the experiment will be converted into Euros at the end of the experiment, using the following conversion scheme: 10 points = 1.50 Euros.

Your total earnings are therefore made up of the participation fee and your earnings from the experiment. At the end of the experiment, you will receive from us your total earnings in cash, i.e., 5 Euros plus your earnings from the experiment.

During the experiment, you will not be allowed to communicate with the other participants. Non-compliance with this rule will result in your exclusion from the experiment and from all payments. All decisions are made anonymously, i.e., none of the other participants will learn of the identity of any other participant who have made a particular decision. Additionally, the payoff is anonymous, i.e., no participant will be informed of the earnings of the other participants.

Information about the experiment

Course of the experiment

- You are part of a group of 3 members. Throughout the experiment, you will interact exclusively with the members of your group.

- Your group belongs to a series with a total of 3 groups, each also consisting of 3 members. The groups of one series will take part in the experiment in succession. That is, the first group in the series has a successor group, the second one has a predecessor and a successor group, and the third group has only a predecessor group.

- Your group’s position in the series will be communicated to you on the screen before the start of the experiment.

Contribution decision

- Your task in this experiment is to make a contribution decision.

- All members of the first group in a series will receive an initial endowment of 30 points.

- All participants of a group will make their contribution decisions simultaneously and independently of each other.

- There are two projects available for the contribution decision, to which each member of the group can contribute any number of points of his/her initial endowment. You have to decide how many points you will contribute to each of the two projects.

- You will keep any points that you do not contribute to the projects in your private account.

Project I

- Each point contributed to Project I will be multiplied by 1.8 and distributed evenly to all group members.

- This means that for each contributed point, each of the 3 group members will receive 0.6 points from the project, regardless of which group member contributed that point.

Project II

- Each point contributed in Project II will be multiplied by 1.2 and distributed evenly to all group members.

- This means that for each contributed point, each of the 3 group members will receive 0.4 points from the project, regardless of which group member contributed that point.

Contribution Threshold and Game Over

- For each of the 3 groups, a contribution threshold applies, which is reached if the sum of all contributions of a group is at least 45 points. In order to reach this threshold, it does not matter whether the points were only contributed to Project I, Project II, or both.

- If the contribution threshold is reached in a group, the experiment will continue and the successor group will make its contribution decision.

- If the contribution threshold in a group is not reached, the game will terminate with a probability of 80%. All members of the active group and all members of the successor group(s) will lose their payoff from both projects and their initial endowment. In this case, the experiment will be over for you.

- With a probability of 20%, the game will not terminate if the contribution threshold has not been reached, but will continue, and the successor group will make their contribution decisions.

Determination of the initial equipment for the second and third groups

- In the first group of a series, the initial endowment available to each group member is 30 points.

- For the second and third group, the initial endowment is determined by the relationship between the contribution threshold and the sum of contributions in Project II from the predecessor group.

- If, in the predecessor group, the number of points invested in Project II equals or exceeds the contribution threshold of 45 points, the initial endowment increases by 5 points for each member of the successor group. If, in the predecessor group, the number of points invested in Project II falls below the contribution threshold of 45 points, the initial endowment for each member of the successor group is reduced by 5 points.

Information after making the decisions

After all members of the currently playing group have made their contribution decisions, members of all groups will receive the following information:

- Sum of the contributions of the members of the currently playing group to Projects I and II,

- Information on whether the contribution threshold has been reached. If it has not, information on whether the game will terminate or not,

- If the game is not over, then information about whether the initial endowment of the successor group is increasing or decreasing (except for the third group).

In addition, each member of the currently playing group will receive information about individual total earnings.

Example

| Group | First Group | ||

| Member | 1-1 | 1-2 | 1-3 |

| Endowment | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Contribution to Project I | 15 | 5 | 0 |

| Sum of the contributions to Project I | 20 | ||

| Earnings from Project I | 20 × 0.6 = 12 | ||

| Contribution to Project II | 10 | 8 | 3 |

| Sum of the contributions to Project II | 21 | ||

| Earnings from Project II | 21 × 0.4 = 8.4 | ||

| Keep in private account | 5 | 17 | 27 |

| Total earnings | 12 + 8.4 + 5 = 25.4 | 12 + 8.4 + 17 = 37.4 | 12 + 8.4 + 27 = 47.4 |

Diagram of Consequences of Contribution Decisions in a Group

Composition of your earnings from the experiment

- If termination of the game occurs, your earnings from the experiment will be as follows:Your earnings from the experiment = Your endowment − your contribution to Project I − your contribution to Project II + 0.6 × Sum of the points in Project I + 0.4 × Sum of the points in Project II

- If a termination occurs in your group or predecessor group, your earnings from the experiment will be zero.

- Regardless of a possible termination, each participant will receive 5 Euro as a participation fee.

Appendix C

Table A1.

Comparison of the default and the default+commitment treatment.

Table A1.

Comparison of the default and the default+commitment treatment.

| Dependent Variable: Contribution to Long-Term Pool | Coefficient | Robust Standard Error | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables: | ||||

| default+commitment treatment | −3.810 | 1.612 | 0.018 | −6.970–0.650 |

| Committed player | 5.555 | 1.707 | 0.001 | −2.210–8.901 |

| Player in G2 | 0.578 | 0.601 | 0.336 | −0.600–1.756 |

| Endowment | 0.254 | 0.067 | 0.001 | 0.124–0.384 |

| Constant | 2.533 | 2.286 | 0.268 | −1.947–7.014 |

Note: Comparison treatment: default. Only G1 and G2 are included. N = 129, Chi2 = 33.85. Group-level-1: Group of the 3 consecutive generations; Group-level-2: Generation. Wald-test: H0: default+commitment treatment + Committed player = 0: Chi2 = 4.54, p = 0.033.

Table A2.

Contributions Relative to the Individual Endowment.

Table A2.

Contributions Relative to the Individual Endowment.

| Dependent Variable: Relative Contribution to Long-Term Pool | Coefficient | Robust Standard Error | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables: | ||||

| default treatment | 7.359 | 2.735 | 0.007 | 1.999–12.719 |

| default+commitment treatment | −5.490 | 5.843 | 0.347 | −16.941–5.962 |

| Committed player | 19.764 | 6.149 | <0.001 | 7.695–31.797 |

| Player in G2 | 4.113 | 2.396 | 0.086 | −0.584–8.810 |

| Constant | 26.054 | 2.025 | <0.001 | 22.085–30.024 |

Note: Comparison treatment: baseline. Only G1 and G2 are included. N = 201, Chi2 = 37.34. Group-level-1: Group of the 3 consecutive generations; Group-level-2: Generation. Wald-test: H0: default+commitment treatment + Committed player = default treatment: Chi2 = 5.92, p = 0.015.

References

- Burke, E. Reflections on the French Revolution, 24th, ed.; Part 3; P.F. Collier & Son: New York, NY, USA, 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Lelieveld, J.; Evans, J.S.; Fnais, M.; Giannadaki, D.; Pozzer, A. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale. Nature 2015, 525, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsiang, S.M.; Burke, M.; Miguel, E. Quantifying the influence of climate on human conflict. Science 2013, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Odorico, P.; Bhattachan, A.; Davis, K.F.; Ravi, S.; Runyan, C.W. Global desertification: Drivers and feedbacks. Adv. Water Resour. 2013, 51, 326–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full.pdf (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Stern, N.H. Why Are We Waiting? The Logic, Urgency, and Promise of Tackling Climate Change, 1st ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar]

- Lenton, T.M. Early warning of climate tipping points. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2011, 1, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.; Dannenberg, A. Climate negotiations under scientific uncertainty. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 17372–17376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milinski, M.; Sommerfeld, R.D.; Krambeck, H.-J.; Reed, F.A.; Marotzke, J. The collective-risk social dilemma and the prevention of simulated dangerous climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 2291–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavoni, A.; Dannenberg, A.; Kallis, G.; Löschel, A. Inequality, communication, and the avoidance of disastrous climate change in a public goods game. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 11825–11829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chermak, J.M.; Krause, K. Individual Response, Information, and Intergenerational Common Pool Problems. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2002, 43, 47–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquet, J.; Hagel, K.; Hauert, C.; Marotzke, J.; Röhl, T.; Milinski, M. Intra- and intergenerational discounting in the climate game. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 1025–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.-E.; Irlenbusch, B.; Sadrieh, A. An intergenerational common pool resource experiment. SSRN Electron. J. 2004, 48, 811–836. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, O.P.; Rand, D.G.; Peysakhovich, A.; Nowak, M.A. Cooperating with the future. Nature 2014, 511, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstyuk, K.; Tarui, N.; Ravago, M.-L.V.; Saijo, T. Intergenerational Games with Dynamic Externalities and Climate Change Experiments. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2016, 3, 247–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peth, D.; Mußhoff, O.; Funke, K.; Hirschauer, N. Nudging Farmers to Comply With Water Protection Rules —Experimental Evidence From Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 152, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, C. Green nudges: Do they work? Are they ethical? Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannenberg, A.; Tavoni, A. Collective action in dangerous climate change games. In The WSPC Reference on Natural Resources and Environmental Policy in the Era of Global Change; Botelho, A., Ed.; Word Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2016; pp. 95–2016. [Google Scholar]

- Milinski, M.; Röhl, T.; Marotzke, J. Cooperative interaction of rich and poor can be catalyzed by intermediate climate targets. Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton-Chellew, M.N.; May, R.M.; West, S. Combined inequality in wealth and risk leads to disaster in the climate change game. Clim. Chang. 2013, 120, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolleau, G.; Sutan, A.; Vranceanu, R.M. Do people contribute more to intra-temporal or inter-temporal public goods? Res. Econ. 2016, 70, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Graziano, S.; Maitra, P. Social Learning and Norms in a Public Goods Experiment with Inter-Generational Advice. SSRN Electron. J. 2004, 73, 357–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Schotter, A.; Sopher, B. Talking Ourselves to Efficiency: Coordination in Inter-Generational Minimum Effort Games with Private, Almost Common and Common Knowledge of Advice. Econ. J. 2008, 119, 91–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putterman, L.; Tyran, J.-R.; Kamei, K. Public goods and voting on formal sanction schemes. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, G. Intergroup Conflict: Individual, Group, and Collective Interests. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 7, 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, C.; McKee, M. Only for my own neighborhood? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2003, 52, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wit, A.P.; Kerr, N.L. ‘Me versus just us versus us all’ categorization and cooperation in nested social dilemmas. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 83, 616–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchan, N.R.; Brewer, M.B.; Grimalda, G.; Wilson, R.K.; Fatas, E.; Foddy, M. Global Social Identity and Global Cooperation. Psychol. Sci. 2011, 22, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchan, N.R.; Grimalda, G.; Wilson, R.K.; Brewer, M.; Fatas, E.; Foddy, M. Globalization and human cooperation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 4138–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.J. Task Complexity: A Review and Analysis. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1988, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.K.; Young, W.B. The relationship between task complexity and decision-making consistency. Res. Nurs. Health 1990, 13, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.W.; Bettman, J.R.; Johnson, E.J. Behavioral decision research: A constructive processing perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1992, 43, 87–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. Are we all environmentalists now? Rhetoric and reality in environmental action. Geoforum 2004, 35, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- How Do Consumers Respond When Default Options Push the Envelope? Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3050562 (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Choi, J.J.; Laibson, D.; Madrian, B.C.; Metrock, A. For Better or for Worse: Default Effects and 401(k) Savings Behavior. In Perspectives on the Economics of Aging; Wisse, D.A., Ed.; University of Chicage Press: Chichago, IL, USA, 2004; pp. 81–125. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.J.; Goldstein, D.G. Do Defaults Save Lives? Science 2003, 302, 1338–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pichert, D.; Katsikopoulos, K.V. Green defaults: Information presentation and pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egebark, J.; Ekstrrm, M.; Ekström, M. Can Indifference Make the World Greener? SSRN Electron. J. 2013, 76, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brounen, D.; Kok, N. On the Economics of Energy Labels in the Housing Market. SSRN Electron. J. 2010, 62, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cappelletti, D.; Mittone, L.; Ploner, M. Are default contributions sticky? An experimental analysis of defaults in public goods provision. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2014, 108, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, F.; Johansson-Stenman, O.; Pham, N. Funding a new bridge in rural Vietnam: A field experiment on social influence and default contributions. Oxf. Econ. Pap. 2015, 67, 987–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariely, D.; Wertenbroch, K. Procrastination, deadlines, and performance: Self-control by precommitment. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 13, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breman, A. Give more tomorrow: Two field experiments on altruism and intertemporal choice. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, J.; Mochon, D.; Wyper, L.; Morabe, J.; Patel, D.; Ariely, D. Healthier by Precommitment. Psycextra Dataset 2014, 25, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freytag, A.; Güth, W.; Köppel, H.; Wangler, L. Is regulation by milestones efficiency enhancing? An experimental study of environmental protection. Eur. J. Polit. Econ. 2014, 33, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadsby, C.B.; Maynes, E. Voluntary provision of threshold public goods with continuous contributions: Experimental evidence. J. Public Econ. 1999, 71, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Bó, E.; Dal Bó, P. ‘Do the right thing:’ The effects of moral suasion on cooperation. J. Public Econ. 2014, 117, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greiner, B. Subject pool recruitment procedures: Organizing experiments with ORSEE. J. Econ. Sci. Assoc. 2015, 1, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischbacher, U. z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp. Econ. 2007, 10, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Ponte, A.; Delton, A.W.; Kline, R.; Seltzer, N.A. Passing It Along: Experiments on Creating the Negative Externalities of Climate Change. J. Polit. 2017, 79, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.; Seltzer, N.; Lukinova, E.; Bynum, A. Differentiated responsibilities and prosocial behaviour in climate change mitigation. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2018, 2, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse, J.; Waichman, I. The effects of contemporaneous peer punishment on cooperation with the future. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | These parameters imply a discount rate of 0.33 from one generation to the next generation. |

| 2 | Note that in Milinski et al. [10], players know the exact probability of losing their endowment if they fail to reach the contribution threshold. In contrast, Barrett and Dannenberg [9] consider the scientific uncertainty by modeling both the threshold level as well as the probability of losing as an uncertain value with a uniform distribution. They show that uncertainty about the threshold level reduces contributions considerably. |

| 3 | The second light was only shown to participants in generations with a subsequent generation, i.e., generations 1 and 2. |

| 4 | Note, that the term “contract” is strictly speaking not correct, since future generations take part without their consent. Therefore, a more precise term would be “agreement”. |

| 5 | In the default+commitment treatment, we had two sessions with only 9 participants each. With respect to the main variables of interest (overall contributions, short-term and long-term contributions), there were no significant differences between the 9-person and 18-person sessions. |

| 6 | Note that in G3, as could be expected, the average sum of tokens contributed to the short-term pool significantly exceeds the sum of tokens contributed to the long-term pool, irrespective of treatment (Wilcoxon-signed-rank tests; baseline: Z = 3.5, p < 0.001; default: Z = 4.7, p < 0.001; default+commitment: Z = 5.1, p < 0.001). Interestingly, in all treatments, the majority of participants in G3 contributed a positive amount to the long-term pool. Unless otherwise stated, we report two-sided p-values for all tests. |

| 7 | When considering contributions relative to the individual endowment instead of absolute contributions, results remain qualitatively similar (see Appendix C Table A2). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).