Optimism Bias during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Romania and Italy

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Does the optimism bias affect people’s beliefs in the case of the Covid-19 pandemic, as it affects other contexts discussed in the literature?

- (2)

- Are there particular instances, and associated objective and subjective factors, of how the optimism bias was experienced in Romania and Italy, at different moments of the pandemic evolution?

2. Research Hypotheses, Questionnaire and Data

2.1. Research Hypotheses

2.2. Questionnaire

2.3. Data

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Testing Optimism Bias

4.2. Non–Parametric Tests to Identify Correlations

5. Conclusions, Implications and Future Research

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Weinstein, N.D. Unrealistic optimism about future life events. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 806–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bavel, J.J.; Baicker, K.; Boggio, P.; Capraro, V.; Cichocka, A.; Crockett, M.; Cikara, M.; Crum, A.; Douglas, K.; Druckman, J.; et al. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020, 4, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dryhurst, S.; Schneider, C.R.; Kerr, J.; Freeman, A.L.J.; Recchia, G.; van der Bles, A.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.; van der Linden, S. Risk perceptions of COVID-19 around the world. J. Risk Res. 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeri, N.C.; Shrestha, N.; Rahman, M.S.; Zaki, R.; Tan, Z.; Bibi, S.; Baghbanzadeh, M.; Aghamohammadi, N.; Zhang, W.; Haque, U. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: What lessons have we learned? Int. J. Epidemiol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-H.; Cheong, H.-K.; Son, D.-Y.; Kim, S.-U.; Ha, C.-M. Perceptions and behaviors related to hand hygiene for the prevention of H1N1 influenza transmission among Korean university students during the peak pandemic period. BMC Infect. Dis. 2010, 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bish, A.; Michie, S. Demographic and attitudinal determinants of protective behaviours during a pandemic: A review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2010, 15, 797–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agüero, F.; Adell, M.N.; Pérez Giménez, A.; López Medina, M.J.; Garcia Continente, X. Adoption of preventive measures during and after the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus pandemic peak in Spain. Prev. Med. 2011, 53, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, G.; Kok, G. The theory of planned behavior: A review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 11, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. The health belief model. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 45–65. ISBN 978-0-7879-9614-7. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd, D.L.; Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 30, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharot, T. The optimism bias. Curr. Biol. 2011, 21, R941–R945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, G. Naturalistic decision making. Hum. Factors 2008, 50, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, S.M.W.; Gell, N.M.; Roth, J.A.; Scholes, D.; LaCroix, A.Z. The Relationship of Perceived Risk and Biases in Perceived Risk to Fracture Prevention Behavior in Older Women. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2015, 49, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludolph, R.; Schulz, P.J. Debiasing Health-Related Judgments and Decision Making: A Systematic Review. Med. Decis. Mak. Int. J. Soc. Med. Decis. Mak. 2018, 38, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D.; Klein, W.M. Resistance of personal risk perceptions to debiasing interventions. Health Psychol. 1995, 14, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouveia, S.O.; Clarke, V. Optimistic bias for negative and positive events. Health Educ. 2001, 101, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Niederdeppe, J. Exploring optimistic bias and the integrative model of behavioral prediction in the context of a campus influenza outbreak. J. Health Commun. 2013, 18, 206–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudisill, C. How do we handle new health risks? Risk perception, optimism, and behaviors regarding the H1N1 virus. J. Risk Res. 2013, 16, 959–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, J.-S.; Lee, S. Optimistic bias about H1N1 flu: Testing the links between risk communication, optimistic bias, and self-protection behavior. Health Commun. 2013, 28, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischhoff, B.; Wong-Parodi, G.; Garfin, D.R.; Holman, E.A.; Silver, R.C. Public Understanding of Ebola Risks: Mastering an Unfamiliar Threat. Risk Anal. Off. Publ. Soc. Risk Anal. 2018, 38, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katapodi, M.C.; Lee, K.A.; Facione, N.C.; Dodd, M.J. Predictors of perceived breast cancer risk and the relation between perceived risk and breast cancer screening: A meta-analytic review. Prev. Med. 2004, 38, 388–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bränström, R.; Kristjansson, S.; Ullén, H. Risk perception, optimistic bias, and readiness to change sun related behaviour. Eur. J. Public Health 2006, 16, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuper-Smith, B.J.; Doppelhofer, L.M.; Oganian, Y.; Rosenblau, G.; Korn, C. Optimistic beliefs about the personal impact of COVID-19. PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raude, J.; Debin, M.; Souty, C.; Guerrisi, C.; Turbelin, C.; Falchi, A.; Bonmarin, I.; Paolotti, D.; Moreno, Y.; Obi, C.; et al. Are people excessively pessimistic about the risk of coronavirus infection? PsyArXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Study of COVID-19 Risk Communication Finds “Optimistic Bias” Slows Preventive Behavior. Available online: https://today.uconn.edu/2020/04/study-covid-19-risk-communication-finds-optimistic-bias-slows-preventive-behavior/ (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Dolinski, D.; Dolinska, B.; Zmaczynska-Witek, B.; Banach, M.; Kulesza, W. Unrealistic Optimism in the Time of Coronavirus Pandemic: May It Help to Kill, If So—Whom: Disease or the Person? J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, L.J.; Lench, H.C.; Karnaze, M.M.; Carlson, S.J. Bias in predicted and remembered emotion. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2018, 19, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heine, S.J.; Lehman, D.R. Cultural variation in unrealistic optimism: Does the West feel more vulnerable than the East? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 68, 595–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierlach, E.; Belsher, B.E.; Beutler, L.E. Cross-Cultural Differences in Risk Perceptions of Disasters. Risk Anal. 2010, 30, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R.M. Optimism and realism: A review of self-efficacy from a cross-cultural perspective. Int. J. Psychol. 2004, 39, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.D.P.; Fowler, J.H. The evolution of overconfidence. Nature 2011, 477, 317–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, R.; Sharot, T.; Wolfe, T.; Düzel, E.; Dolan, R.J. Optimistic update bias increases in older age. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strunk, D.R.; Lopez, H.; DeRubeis, R.J. Depressive symptoms are associated with unrealistic negative predictions of future life events. Behav. Res. Ther. 2006, 44, 861–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korn, C.W.; Sharot, T.; Walter, H.; Heekeren, H.R.; Dolan, R.J. Depression is related to an absence of optimistically biased belief updating about future life events. Psychol. Med. 2014, 44, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, N.; Sharot, T.; Faulkner, P.; Korn, C.W.; Roiser, J.P.; Dolan, R.J. Losing the rose tinted glasses: Neural substrates of unbiased belief updating in depression. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asimakopoulou, K.G.; Skinner, T.C.; Spimpolo, J.; Marsh, S.; Fox, C. Unrealistic pessimism about risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in patients with type 2 diabetes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2008, 71, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, L.A.; Mahadevan, D.; Appelbaum, P.S.; Klein, W.M.P.; Weinstein, N.D.; Mori, M.; Degnin, C.; Sulmasy, D.P. Perceptions of control and unrealistic optimism in early-phase cancer trials. J. Med. Ethics 2018, 44, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, L.A.; Mahadevan, D.; Appelbaum, P.S.; Klein, W.M.P.; Weinstein, N.D.; Mori, M.; Degnin, C.; Sulmasy, D.P. Variations in Unrealistic Optimism Between Acceptors and Decliners of Early Phase Cancer Trials. J. Empir. Res. Hum. Res. Ethics 2017, 12, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treloar, C.; Hopwood, M. “Look, I’m fit, I’m positive and I’ll be all right, thank you very much”: Coping with hepatitis C treatment and unrealistic optimism. Psychol. Health Med. 2008, 13, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Pfleeger, S.L. Principles of survey research: Part 5: Populations and samples. ACM SIGSOFT Softw. Eng. Notes 2002, 27, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltar, F.; Brunet, I. Social research 2.0: Virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Res. 2012, 22, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, D.D. Snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociol. Methodol. 2011, 41, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, K. Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiner, D. Our Research’s Breadth Lives on Convenience Samples. A Case Study of the Online Respondent Pool “SoSci Panel”. Stud. Commun. Media 2016, 5, 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M.; Hollensen, S. Marketing Research: An International Approach; Prentice Hall/Financial Times: Harlow, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-273-64635-8. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, K.B. Researching Internet-Based Populations: Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Survey Research, Online Questionnaire Authoring Software Packages, and Web Survey Services. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 2005, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L. Instrument development for health belief model constructs. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1984, 6, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggaley, A.R.; Hull, A.L. The Effect of Nonlinear Transformations on a Likert Scale. Eval. Health Prof. 1983, 6, 483–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, T.J.; Pierce, H.R. A comparison of Likert scale and traditional measures of self-efficacy. J. Appl. Psychol. 1998, 83, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, G. Likert scales, levels of measurement and the “laws” of statistics. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2010, 15, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, A.J. Comparison of an ordinal and a continuous outcome measure of muscle soreness. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 1999, 15, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorens, V.; Buunk, B.P. Social Comparison of Health Risks: Locus of Control, the Person-Positivity Bias, and Unrealistic Optimism. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fife-Schaw, C.; Barnett, J. Measuring Optimistic Bias. In Doing Social Psychology Research; Breakwell, G.M., Ed.; The British Psychological Society and Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2008; pp. 54–74. ISBN 978-0-470-77627-8. [Google Scholar]

- Otten, W.; Van Der Pligt, J. Context Effects in the Measurement of Comparative Optimism in Probability Judgments. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 1996, 15, 80–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronay, R.; Kim, D.-Y. Gender differences in explicit and implicit risk attitudes: A socially facilitated phenomenon. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2006, 45, 397–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P.; Alessandri, G.; Abela, J.R.; McWhinnie, C.M. Positive orientation: Explorations on what is common to life satisfaction, self-esteem, and optimism. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2010, 19, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puskar, K.R.; Bernardo, L.M.; Ren, D.; Haley, T.M.; Tark, K.H.; Switala, J.; Siemon, L. Self-esteem and optimism in rural youth: Gender differences. Contemp. Nurse 2010, 34, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kouzy, R.; Abi Jaoude, J.; Kraitem, A.; El Alam, M.B.; Karam, B.; Adib, E.; Zarka, J.; Traboulsi, C.; Akl, E.W.; Baddour, K. Coronavirus Goes Viral: Quantifying the COVID-19 Misinformation Epidemic on Twitter. Cureus 2020, 12, e7255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Types, Sources, and Claims of Covid-19 misinformation. Available online: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/types-sources-and-claims-covid-19-misinformation (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Pennycook, G.; McPhetres, J.; Zhang, Y.; Rand, D.G. Fighting COVID-19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy nudge intervention. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 31, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985, 4, 219–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Fung, H.H.L.; Isaacowitz, D.M. Age differences in dispositional optimism: A cross-cultural study. Eur. J. Ageing 2009, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, L.D.; Macfarlane, S.; Yanez, C.; Imai, W.K. Risk-perception: Differences between adolescents and adults. Health Psychol. 1995, 14, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reniers, R.L.E.P.; Murphy, L.; Lin, A.; Bartolomé, S.P.; Wood, S.J. Risk Perception and Risk-Taking Behaviour during Adolescence: The Influence of Personality and Gender. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.E.; Adab, P.; Cheng, K.K. Covid-19: Risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ 2020, m1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipkus, I.M.; Klein, W.M.P.; Skinner, C.S.; Rimer, B.K. Breast cancer risk perceptions and breast cancer worry: What predicts what? J. Risk Res. 2005, 8, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.B. Explaining Americans’ responses to dread epidemics: An illustration with Ebola in late 2014. J. Risk Res. 2017, 20, 1338–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, M.R.; Franco-Watkins, A.M.; Thomas, R. Psychological plausibility of the theory of probabilistic mental models and the fast and frugal heuristics. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 115, 199–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischhoff, B.; Bostrom, A.; Quadrel, M.J. Risk Perception and Communication. Annu. Rev. Public Health 1993, 14, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibley, C.G.; Harré, N. The impact of different styles of traffic safety advertisement on young drivers’ explicit and implicit self-enhancement biases. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. The precaution adoption process. Health Psychol. 1988, 7, 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.M.; Weisfuse, I.B.; Hernandez-Avila, M.; del Rio, C.; Bustamante, X.; Rodier, G. Pandemic Influenza as 21st Century Urban Public Health Crisis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 1963–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.C.; Waters, L.; Holland, O.; Bevins, J.; Iverson, D. Developing pandemic communication strategies: Preparation without panic. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.R.; McGuire, W.J. Prior Reassurance of Group Consensus as a Factor in Producing Resistance to Persuasion. Sociometry 1965, 28, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, W.J. Vaccine for brainwash. Psychol. Today 1970, 3, 36. [Google Scholar]

| Item | Question |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Age | Respondent’s age |

| Gender | Male Female Other |

| The higher level of completed education is: | Middle education Higher education |

| Health and Covid–related questions | |

| Self reported health status | Lower than other people The same as other people Better than other people |

| Does your job allow you to work from home? | Yes No |

| How well informed do you consider you are regarding the preventive behavior you should pursue against Covid-19 infection? | Measurement: 1–10 1 = no information at all 10 = very well informed |

| To what extent you adopted the recommended preventive behavior against Covid-19? | |

| Perceived susceptibility | |

| SS1: It is very likely for me to get infected with Covid-19 | Measurement: 1–7 1 = total disagreement 7 = total agreement |

| SS2: It is very likely for someone to get infected with Covid-19. | |

| SS3: I feel that I have higher chances to get sick, compared to other people |

| Variable | Min | Mean | Median | Max | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (RO) | 16 | 33.89 | 32 | 82 | 13.26 |

| Age (IT) | 14 | 36.94 | 34 | 79 | 15.07 |

| Variable | Proportion | ||||

| Romania | Italy | ||||

| Gender Female Male | 75.5% 24.5% | 62% 38% | |||

| Education Middle education Higher education | 32.2% 67.8% | 34.9% 65.1% | |||

| Health status Below others Same as others Better than others | 6.7% 61.1% 32.1% | 5.5% 68.9% 25.6% | |||

| Work from home Yes No | 63.8% 36.2% | 83.8% 16.2% | |||

| Item | Measurement: | Optimism Index |

|---|---|---|

| Indirect measurement | ||

| SS1: It is very likely for me to get infected with Covid-19 | Likert 1–7 | OPT1 = SS1–SS2 |

| SS2: It is very likely for someone to get infected with Covid-19. | Likert 1–7 | - |

| Direct measurement | ||

| SS3: I feel that I have higher chances to get sick from Covid-19, compared to other people | Likert 1–7 | OPT3 = SS3 |

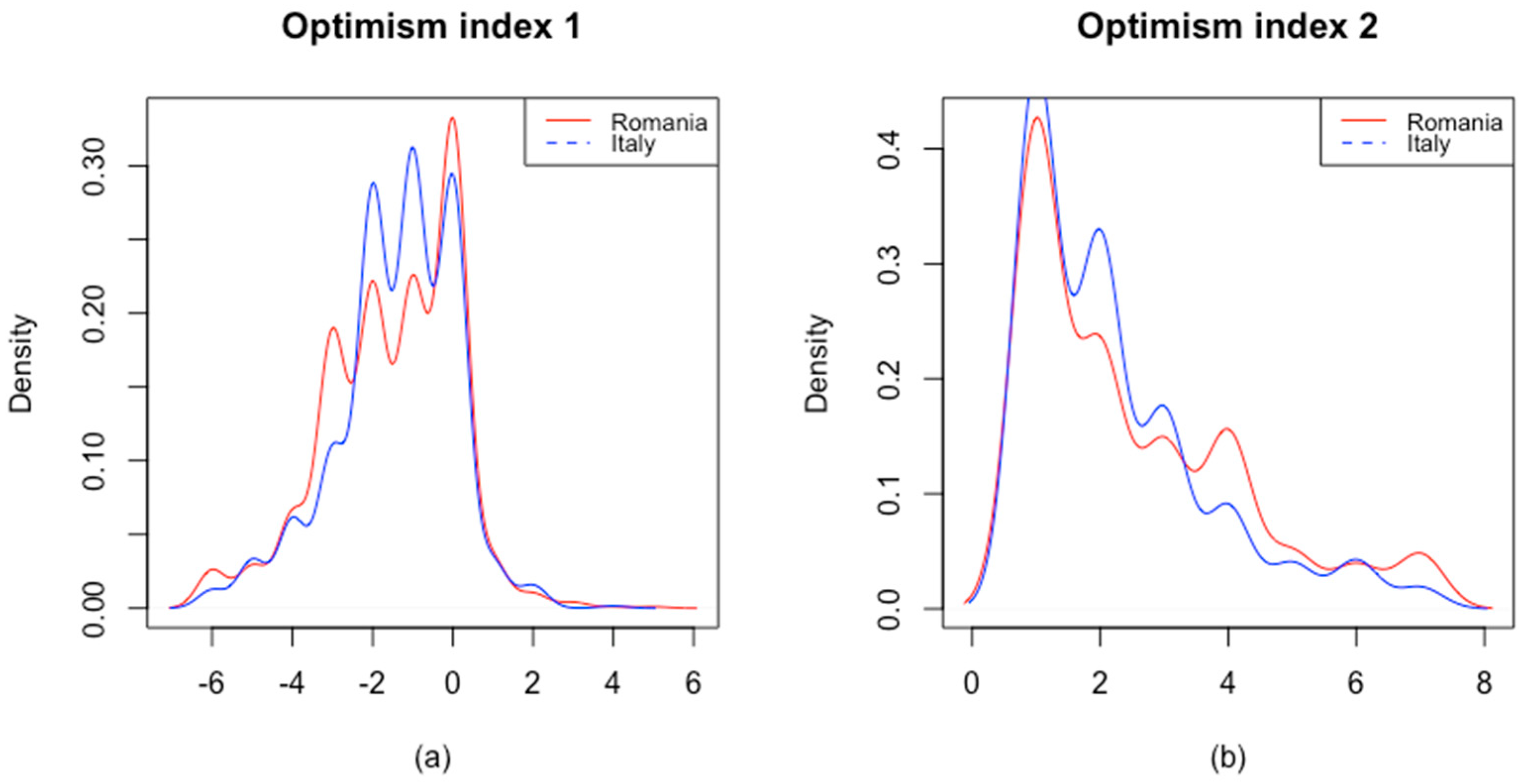

| Romania | Min | Median | Mean | Max | Sd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPT1 | −6 | −1 | −1.508 | 5 | 1.641 |

| OPT2 | 1 | 2 | 2.512 | 7 | 1.703 |

| Italy | Min | Median | Mean | Max | sd |

| OPT1 | −6 | −1 | −1.403 | 4 | 1.475 |

| OPT2 | 1 | 2 | 2.2 | 7 | 1.452 |

| Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon Test | Optimism Index 1 | Optimism Index 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Romania | ||

| H1a: Optimism bias exists | V = 11444, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | V = 53901, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 |

| Alternative hypothesis: | True location shift is lower than zero | True location shift is lower than 4 |

| Decision | H1(a): Optimism bias is confirmed in Romania | H1(a): Optimism bias is confirmed in Romania |

| Italy | ||

| H1b: Optimism bias exists | V = 5873.5, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 | V = 14848, p-value < 2.2 × 10−16 |

| Alternative hypothesis: | True location shift is lower than zero | True location shift is lower than 4 |

| Decision | H1(b): Optimism bias is confirmed in Italy | H1(b): Optimism bias is confirmed in Italy |

| H1c: Romanians are more optimistic than Italians | W = 406575, p-value = 0.316 | W = 449538, p-value = 0.003626 |

| Alternative hypothesis: | True location shift is not equal to 0 | True location shift is lower than 0 |

| Decision | H1(c) is infirmed: No differences in optimism between countries | H1(c) is confirmed: Romanians are more optimistic than Italians |

| Test | Optimism Index 1 | Optimism Index 2 |

|---|---|---|

| No gender differences | ||

| Romania | W = 113470, p-value = 0.4037 H2a is supported | W = 112579, p-value = 0.2954 H2a is supported |

| Italy | W = 58846, p-value = 0.02707 H2a is not supported | W = 61780, p-value = 0.2405 H2a is supported |

| No education differences | ||

| Romania | W = 117340, p-value < 0.0001 H2b not supported | W = 110986, p-value < 0.0001 H2b not supported |

| Italy | W = 59130, p-value = 0.207 H2b is supported | W = 61520, p-value = 0.6981 H2b is supported |

| Bias increases with age | ||

| Romania | Rho = 0.104 p-value = 0.0005 H2c not supportedH2c is supported | Rho = 0.179 p-value < 0.0001 H2c not supported H2c is supported |

| Italy | 0.268 p-value < 0.0001 H2c is supported | 0.118 p-value = 0.0013 H2c is supported |

| No differences between those who have the option to work from home, and those who have not | ||

| Romania | W = 157786 p-value = 0.9864 H3 is not supported | W = 165230, p-value = 0.0002 H3 is supported |

| Italy | W = 37906, p-value = 0.7794 H3 is not supported | W = 39469, p-value = 0.2937 H3 is not supported |

| Kruskal-Wallis Test | Optimism Index 1 | Optimism Index 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Health status is related to optimism level | ||

| Romania | chi-squared = 8.3708 p-value = 0.015 | chi-squared = 27.551 p-value < 0.0001 |

| Italy | chi-squared = 18.543 p-value < 0.0001 | chi-squared = 30.474 p-value < 0.0001 |

| Romania | ||

| p-values | Lower health status than other people | Similar health status as other people |

| Similar health status as other people | 0.290 | - |

| Better health status than other people | 0.035 * | 0.114 |

| Italy | ||

| p-values | Lower health status than other people | Similar health status as other people |

| Similar health status as other people | 0.00053 *** | - |

| Better health status than other people | 0.058 | 0.028 * |

| Romania | ||

| p-values | Lower health status than other people | Similar health status as other people |

| Similar health status as other people | 0.00012 *** | - |

| Better health status than other people | 1.1 × 10−6 *** | 0.034 * |

| Italy | ||

| p-values | Lower health status than other people | Similar health status as other people |

| Similar health status as other people | 6.2 × 10−6 *** | - |

| Better health status than other people | 2.5 × 10−7 *** | 0.081 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Druică, E.; Musso, F.; Ianole-Călin, R. Optimism Bias during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Romania and Italy. Games 2020, 11, 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/g11030039

Druică E, Musso F, Ianole-Călin R. Optimism Bias during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Romania and Italy. Games. 2020; 11(3):39. https://doi.org/10.3390/g11030039

Chicago/Turabian StyleDruică, Elena, Fabio Musso, and Rodica Ianole-Călin. 2020. "Optimism Bias during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Romania and Italy" Games 11, no. 3: 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/g11030039

APA StyleDruică, E., Musso, F., & Ianole-Călin, R. (2020). Optimism Bias during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Romania and Italy. Games, 11(3), 39. https://doi.org/10.3390/g11030039