Abstract

The Government of Colombia imposes a variety of taxes that must be paid by individual wage earners, called in their entirety “social protection contributions”. Since 2007 individual payments have been collected using an on-line mechanism. In order to improve compliance, the Government used a controlled field experiment in which various “pop-up messages” were sent to individuals when making their on-line payments, as behavioral “nudges”. We examine the impact of these nudges on individual reporting behavior. We find mixed evidence that these messages increased compliance rates relative to a control group that received a so-called “neutral” message. However, we also demonstrate that the use as the control group of individuals receiving a so-called “neutral” message creates considerable bias; that is, the receipt of any message of any type clearly influences behavior. Instead, we show that the appropriate control group should be individuals who receive no message at all. When this control group is used, we find that self-employed individuals generally increase their contributions; individuals who are making declarations on behalf of all employees in their company are less likely to respond to messages in a systematic way.

1. Introduction

Getting individuals to comply fully with their legally due tax obligations is a challenge in all countries, and tax agencies are constantly looking for ways to improve compliance.1 The standard tools have traditionally focused on enhanced enforcement policies (e.g., more frequent audits, more punitive fines) and, in some instances, improved taxpayer services (e.g., simpler tax forms, agency-completed tax forms). More recently, tax agencies have begun to explore alternative policies that utilize the insights of “behavioral economics”, loosely defined as the application of methods from other social sciences like sociology, anthropology, and, especially, psychology to economics. At its core is the belief that most individuals exhibit a “dual-process theory” of cognition and information processing, most fully developed and elaborated by []. Here an individual is seem as making some decisions automatically (e.g., rapidly, unconsciously, effortlessly, called “Fast” or “System 1” and done by “Humans”) and some non-automatically (e.g., deliberately, deductively, rationally, called “Slow” or “System 2” and done by “Econs”). As a result, individuals often exhibit systematic cognitive biases, at least in their automatic decision making, these biases prevent them from making decisions that are truly in their best interest, but these biases can be overcome by the ways in which choices are presented to individuals. By changing the “choice architecture” within which individuals make their automatic decisions, policy makers can “nudge” individuals away from their default settings in ways that encourage them to make better informed decisions without mandating that individuals behave in proscribed ways.2 Indeed, increasing numbers of countries have established a behavioral economics unit inside or outside of government, and have implemented policies suggested by these units, as documented in some detail by [,,,,], among many others.3

In the context of tax compliance, nudges have begun to expand the tools of government beyond the obvious and traditional ones of audit and fines. In some instances, tax agencies have explored policies that attempt to change taxpayer attitudes, in an effort to influence the “social norm” of tax compliance.4 In many instances these appeals to taxpayers’ social norms take the form of letters sent to taxpayers requesting payment of unpaid taxes, with accompanying statements like “Most people pay their taxes”, “Paying taxes helps others”, or “Taxes provide for public services”. These letters from tax agencies also sometimes attempt to change taxpayers’ perceptions of enforcement policies by communicating in a letter a higher probability of detection (e.g., [,,]), and the letters may attempt to influence taxpayers’ perceptions of the tax code by offering the administrative provision of informational services (e.g., []), again with somewhat variable impacts.

The use of messages as nudges began with [], and its use has grown significantly in recent years.5 For example, a recent controlled field experiment (or a “randomized controlled trial”) carried out in the United Kingdom by Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs (HMRC) and HMRC’s Behavioral Insights Team found that appeals to socially acceptable or appropriate forms of behavior often yielded a significant positive response []. A similar finding was made in a controlled field experiment in the State of Washington, where normative appeals promoted increased reporting compliance by taxpayers subject to that state’s Business and Occupation tax []. However, evidence for social appeals is not clear-cut. An earlier experiment conducted in Minnesota found no evidence that appeals to social norms had a significant impact on tax reporting compliance [], and there are multiple examples of controlled field experiments reporting ambiguous effects of moral appeals, including [,,,,,]. There is also a growing literature on controlled field experiments of various and creative types in Latin America, including [] for Argentina, [] for Chile, [] for Argentina, [] for Uruguay, [] for Peru, [] for Colombia, [] for Argentina, and [] for Uruguay. It seems clear that the impact on compliance of nudges—and nudges of any type—remains unresolved.

This paper uses a controlled field experiment in Colombia to examine the impact of messages as nudges on an individual’s subsequent reporting behavior. As discussed in detail later, the Government of Colombia imposes a variety of taxes that must be paid by individual wage earners, both self-employed individuals and employees of companies. Some of these taxes entitle the individuals to benefits whose size varies with their contributions, and some are used to finance government and non-government provision of training programs and social services. In their entirety, we call these payments “social protection contributions”. Importantly, since 2007 individual payments have been collected using an on-line mechanism, Planilla Integral de Liquidación de Aportes (or PILA), an electronic system that allows contributors to declare their obligations and to make their respective payments, after which the revenues are distributed to the separate programs. Virtually all payments are now collected through PILA, and the total amount raised from these payments is substantial. However, evasion of those contributions is also substantial. For example, total collections in 2012 were 39,940.0 billion Colombian pesos (COP) (or United States dollars (USD) 19.970 billion at an exchange rate of 1 USD = 2000 COP), equivalent to 5.4 percent of Colombian GDP.6 However, the Government estimated that potential contributions with full compliance for that same year were 54,540.0 billion COP, for a “tax gap” between potential and actual contributions of 14,600.0 billion COP, or 26.8 percent of potential contributions, or 2.0 percent of GDP []. The Government estimates that the tax gap has, if anything, increased in the last several years.

Concern with compliance led the Government to create in 2009 an agency called Unidad de Gestión Pensional y Contribuciones Parafiscales (or UGPP), which reports directly to the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público). As part of its overall compliance strategy, UGPP introduced in 2013 a program in which “pop-up messages” of various types were displayed in the electronic payment system PILA to randomly selected individuals. These messages included ones that reminded the individuals that they would face greater risk of audit or fines if they did not report honestly; they included one message that indicated that the individual would personally benefit; and they also included one message that attempted to appeal to the individual’s social norm of compliance. Importantly, these messages were shown to randomly selected individuals at the precise time that they were making their reporting decisions, and the messages allowed the individual to make whatever decisions that they wished to make.7 Note that the “individual” receiving the message was of two different types: an individual making the reporting decision as a representative, or agent, of a firm with multiple employees (termed a “company agent”), and an individual making the contribution on his or her own behalf as a “self-employed individual”. In our empirical analyses, we consider company agents and self-employed individuals separately.

Unlike many previous controlled field experiments, our paper therefore examines the impact of nudges sent directly to individuals via an online platform, it examines the impact of these messages at precisely the time when an individual is making his or her reporting decision, it examines messages that communicate both enforcement and social norms information, and it does so in a setting (Colombia) and for a tax (social protection contributions) that have not previously been considered.

Our paper also makes a methodological contribution. Most previous controlled field experiments have examined the impact of nudges by comparing the responses of individuals who receive the treatment message to a control group of individuals who receive a neutrally worded message.8 However, it seems likely the receipt of any message from the tax authority will affect behavior, regardless of the specific wording, so that a simple comparison of treatment versus control groups cannot hope to generate unbiased estimates of the impact of the nudge. Unlike most previous field studies, we are able to examine the impact of the nudge by comparing the treatment group with a control group of individuals who do not receive any message of any type, thereby avoiding this potential bias.

We find that the impacts of these different pop-up messages on individual reporting behavior are quite mixed, at least when we compare reporting behavior of those who receive a nudge via a message to a control group that received a so-called “neutral” message. Relatedly, we also demonstrate that the use as the control group of individuals receiving a so-called “neutral” message creates considerable bias; that is, the receipt of any message of any type clearly influences behavior. Indeed, we find convincing evidence that the receipt of these messages lead to systematic “decay” in individual participation, as individuals who had begun to make declarations chose not to complete their on-line payments once any message appeared. Given this response, we believe that the use of a control group that received a “neutral” message gives results that have little meaning, or at least results whose meaning is difficult to interpret. Instead, we argue that the appropriate control group should be individuals who receive no message at all. Indeed, when the appropriate control group is established, we find more plausible if still somewhat mixed results. Specifically, we find that self-employed individuals generally increase their declarations, often by large amounts, when they receive a message from the government. Individuals who are making declarations on behalf of all employees in their company (or company agents) are less likely to respond to messages in a systematic way.

In the next section, we discuss the different types of social protection contributions in Colombia. We then present a framework in which the different pop-up messages may be interpreted, followed by the design of the experiment. We then present our results, and our conclusions are in the final section.

2. Social Protection Contributions in Colombia

In addition to the individual income tax, the Government of Colombia imposes a variety of taxes on the wages of workers.9 Some of these taxes are more properly viewed as contributions because individuals are entitled to benefits associated with their contributions. Several have all the features of a tax, but nevertheless do not go into the general revenues of the government and instead are used to finance government and non-government provision of training programs and social services. In their entirety, we call these payments “social protection contributions”.

These payments are divided into two broad groups. The first group corresponds to social security contributions, particularly pension, labor risk, and health care contributions. These contributions are imposed on labor income of employees and the self-employed. The second group corresponds to contributions that are usually called parafiscales, or mandatory taxes established by law that affect a specific and unique social or economic group and that are used for the benefit of that same sector. The parafiscales are imposed on the payrolls of employers and are used to finance the Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (or the Colombian Institute for Family Welfare, or ICBF), the Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje (or the National Training Service, or SENA), and the Cajas de Compensación Familiar (or the Family Benefit Fund).

Since 2007 the social protection contributions have been collected through PILA. The revenues collected through PILA are then distributed to the administrators of each type of contribution (i.e., pension funds, health care administrators, labor risk insurers, ICBF, SENA and Cajas de Compensación Familiar. Before PILA, individuals had to make their payments in separate amounts to each individual program. Also, since 2009 the Government has used UGPP to coordinate compliance policies and strategies.

As noted earlier, there are two main types of social protection contributions: Social security contributions and parafiscales. We consider each in turn.

2.1. Social Security Contributions

There are several main social security contributions. Pension contributions correspond to 16 to 18 percent of labor income of employees and self-employed individuals, paid on a monthly basis.10 For employees, employers pay 75 percent of the total contribution, and the employee pays the rest. These programs are administered by pension funds.

There are also contributions for labor risks (e.g., unemployment insurance, disability insurance). These contributions vary between 0.349 percent and 8.7 percent of the payroll, depending on the economic activity of the individual. In the case of employees, these contributions are all made by their employer. Since 2011 some self-employed individuals are also obligated to make this contribution. Insurance companies administer these programs.

There are also related contributions for health care. For most individuals, health care contributions are 12.5 percent of labor income of employees and self-employed individuals, paid on a monthly basis. Self-employed individuals must pay the full 12.5 percent contribution; for employees, their employers pay 8.5 percentage points and the employee pays 4 percentage points. Note that after the 2012 tax reform employers do not pay anything for employees who earn up to 10 times the minimum wage. These contributions are administered by the Empresas Administradoras de Salud (or EPS).

Every employee must pay the social security contribution depending on the total income earned during a month, including labor income (base wage) and other benefits, bonuses, and fringe benefits that the individual receives as a compensation for his or her work. This payment is made by an individual acting as an agent for the firm (company agent), who reports through PILA for each employee of the firm the employee identification number, the total income earned, other items in the tax base, and social security contributions. Note that there are some differences in items included in the base (e.g., bonuses) depending on the kind of employee (e.g., someone working for a private company, someone working for the government). Self-employed individuals must make contributions based only on the income earned from their economic activity, reporting their income and contributions via PILA.

2.2. Parafiscales

There are several types of parafiscales. The Cajas de Compensación Familiar was created at the end of the 1950s by entrepreneurs and workers with the objective of reducing the economic burden of the poorest workers, through monetary subsidies and in-kind services. Companies pay 4 percent of their payroll to the Cajas de Compensación Familiar. Self-employed individuals are not required to make these contributions. The Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF) is a decentralized public establishment created in 1968 with the aim of providing protection to children and improving the welfare of the Colombian families. Before the 2012 tax reform, all companies had to pay 3 percent of their payroll to the ICBF; after the tax reform, companies have to pay 3 percent of the payroll of employees who earn more than 10 times the minimum wage. Self-employed individuals are not obligated to pay these contributions. The Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje (or SENA) is a public institution under the supervision of the Ministerio de Trabajo (or the Ministry of Work). Its main function is to invest in social and technical development of the workers through various training programs of integral professional formation. Before the 2012 tax reform, all companies had to pay 2 percent of their payroll to the SENA; after the tax reform, companies have to pay 2 percent of the payroll of employees who earn more than 10 times the minimum wages. Self-employed individuals are not required to make these contributions. Note that the taxable base for the parafiscales is somewhat smaller than in the case of social security contributions due mainly to differential treatment of bonuses, and there is also a differentiation between public and private employees among those items. As with social insurance contributions, a company agent reports items for each employee of the firm, and the self-employed report their own income and contribution.

3. Theoretical Background: Enforcement, Nudges, and Compliance

The standard approach to tax administration focuses on enforcement as the main tool by which a government achieves compliance with its tax laws. This approach is consistent with, even if not necessarily derived from, the basic economics-of-crime model of tax compliance developed by [] and first applied to tax compliance by [].11. In this model, a purely rational, solely self-interested, completely self-controlled individual is assumed to maximize the expected utility of the income tax evasion gamble, weighing the benefits of successful underreporting against the risky prospect of detection and punishment. More precisely, an individual is assumed to have a fixed amount of “true” income, and must choose how much to report to the tax authorities and how much to underreport. The individual pays taxes at a given tax rate on every dollar of income that is reported, while no taxes are paid on underreported income. However, the individual may be audited with a fixed probability; if audited, then all underreported income is discovered, and the individual must pay a penalty on each dollar that he or she was supposed to pay in taxes but did not pay. The individual’s income if caught underreporting equals income less taxes paid on reported income less penalties on unreported taxes less the burden of preparing and filing a tax return. If underreporting is not caught, income is income less taxes paid on reported income less compliance costs. The individual is assumed to choose reported income to maximize expected utility, where utility is assumed to depend only on income. This optimization generates a standard first-order condition for an interior solution; given concavity of the utility function, the second-order condition is satisfied. Comparative statics results are easily derived, with reported income increasing if the audit rate or the penalty rate increases. Note that, although this framework was developed for, and has largely been applied to, the income tax reporting decision, its basic features apply to most any tax reporting decision, such as social protection reporting decisions in Colombia. Given that an individual’s social protection contributions often entitle the individual to a benefit that depends on his or her reported contributions, the standard approach must be modified to add this benefit. It is straightforward to demonstrate that reported income increases with the benefit [,].

The main conclusion from the economics-of-crime framework is that enforcement plays an important role in the individual’s reporting decision. Indeed, as emphasized by [,], this framework concludes that detection and punishment are the only factors driving an individual’s reporting decision; that is, the standard economic analysis concludes that an individual pays taxes because—and only because—of this fear of detection and punishment.

This is an important and plausible insight, one with clear and simple policy implications that leave little room for nudges. However, there are several problems here.12 Most all of these problems stem from the underlying assumptions of the standard neoclassical economic model of human behavior: Individuals are rational, they are purely self-interested, and they have unlimited willpower. While these assumptions may be a useful starting point for the analysis of individual behavior, there is increasing evidence that they are inaccurate and unrealistic depictions of many, perhaps most, individuals. As discussed by [] and [], there is growing acceptance that, contrary to the standard neoclassical approach:

- individuals are affected by the ways in which choices are “framed” (e.g., “reference points”, gains versus losses, “loss aversion”, “risk-seeking behavior”, “status quo bias”);

- they face limits on their ability to compute (e.g., “bounded rationality”, “mental accounting”);

- they systematically misperceive, or do not perceive at all, the true costs of actions (e.g., “fiscal illusion”, “saliency”, “overweighting” of probabilities);

- individuals face limits on their “self-control” (e.g., “hyperbolic discounting”, Christmas savings clubs, automatic enrollment programs);

- they are motivated not simply by self-interest, but also by notions of fairness, altruism, reciprocity, empathy, sympathy, trust, guilt, shame, morality, alienation, patriotism, social customs, social norms, and many other objectives; and

- they are influenced by the social context in which (e.g., diversity), and the process by which (e.g., voting rules), decisions are made.

In short, individuals are not always the rational, outcome-oriented, self-controlled, selfish, and egoistic consumers envisioned by much of our standard theory. Behavioral economics uses these deviations from the standard assumptions as the starting point for a more realistic view on how individuals make choices. Importantly, behavioral economics uses these deviations as the justification for alternative government policies that change the choice architecture facing individuals, thereby leading to subsequent changes in individual behavior.

It is here that nudges enter. An individual may change his or her reporting decision based on such considerations as: how the reporting decision is framed; how complicated the decision may be; whether the individual’s costs—and benefits—of the decision (financial or otherwise) are highlighted and communicated; how the time dimension of these costs and benefits is conveyed to the individual; whether the potential impacts on others of one’s own decision are indicated to the individual; and whether the broader social context is mentioned. As suggested by the “Behavioral Insights Team” (BIT), first established with the U.K. government and now an independent company, there are many tools that can influence an individual’s decisions in a predictable way without prohibiting the individual from making a different decision [].

It is these insights from previous theoretical and experimental research on messages that directly inform the design of our controlled field experiment. As discussed later when we present our experimental design, a message may remind an individual that underreporting may be detected by the tax administration, even that the chances of detection are significant. A message may remind an individual that underreporting may lead to a financial penalty. A message may remind an individual that increased social protection reporting may lead to added benefits for the individual. A message may also be designed to influence the social norm of compliance, by reminding the individual that his or her reporting may benefit the broader society; as shown theoretically by [] and [], such a change in the social norm is likely to increase the individual’s reporting.

Overall, these messages are designed to influence the individual’s perceptions of the incentives and the effects of reporting. They are also designed to act as a prompt or a reminder about some of the potential consequences of his or her reporting decision. In principle, all of these messages are expected to nudge the individual toward increased reporting. Even so, previous research has given conflicting evidence on the effectiveness of these nudges.

In the specific context of Colombia, our research question is therefore simply stated: Do these pop-op messages nudge an individual to improve his or her compliance? The next section discusses our controlled field experiment design to investigate the impact of these nudges.

4. Controlled Field Experiment Design

The controlled field experiment consisted of seven treatment messages that were shown to a randomly selected sample of individuals at the moment that they were going to make their payment. In any of the seven cases, the individual who received the message had the option to modify his or her payment or to continue with the process as he or she was intending before the message. In an attempt to establish a baseline, one message (denoted Message 7) was intended to provide neither positive nor negative impacts; as we discuss later, we believe that this message did not provide the appropriate baseline for the control group, and so we also used an alternative measure of the baseline for the control group to make more meaningful comparisons. Other messages attempted to remind an individual about audit probabilities (Message 1—“Any contributor can be audited”), audit effectiveness (Message 2—“When we audit contributions evaders, we detect them”), and penalties (Message 3—“You face a high risk of being sanctioned if you evade”). Message 5 attempted to remind an individual that payment of the social protection contribution entitled the individual to some financial benefits from payment (“You will benefit if your contribution filing is accurate”). Message 6 was directed to an individual’s social norm of compliance (“We all benefit from accurate contribution filings”). UGPP ultimately decided to stop showing Message 4 (“You will be audited”) because it was deemed unlikely that UGPP could in fact audit all of the individuals who received this message. The messages are presented in Table 1, and more detail about each of the messages is presented in Appendix A.13

Table 1.

Messages.

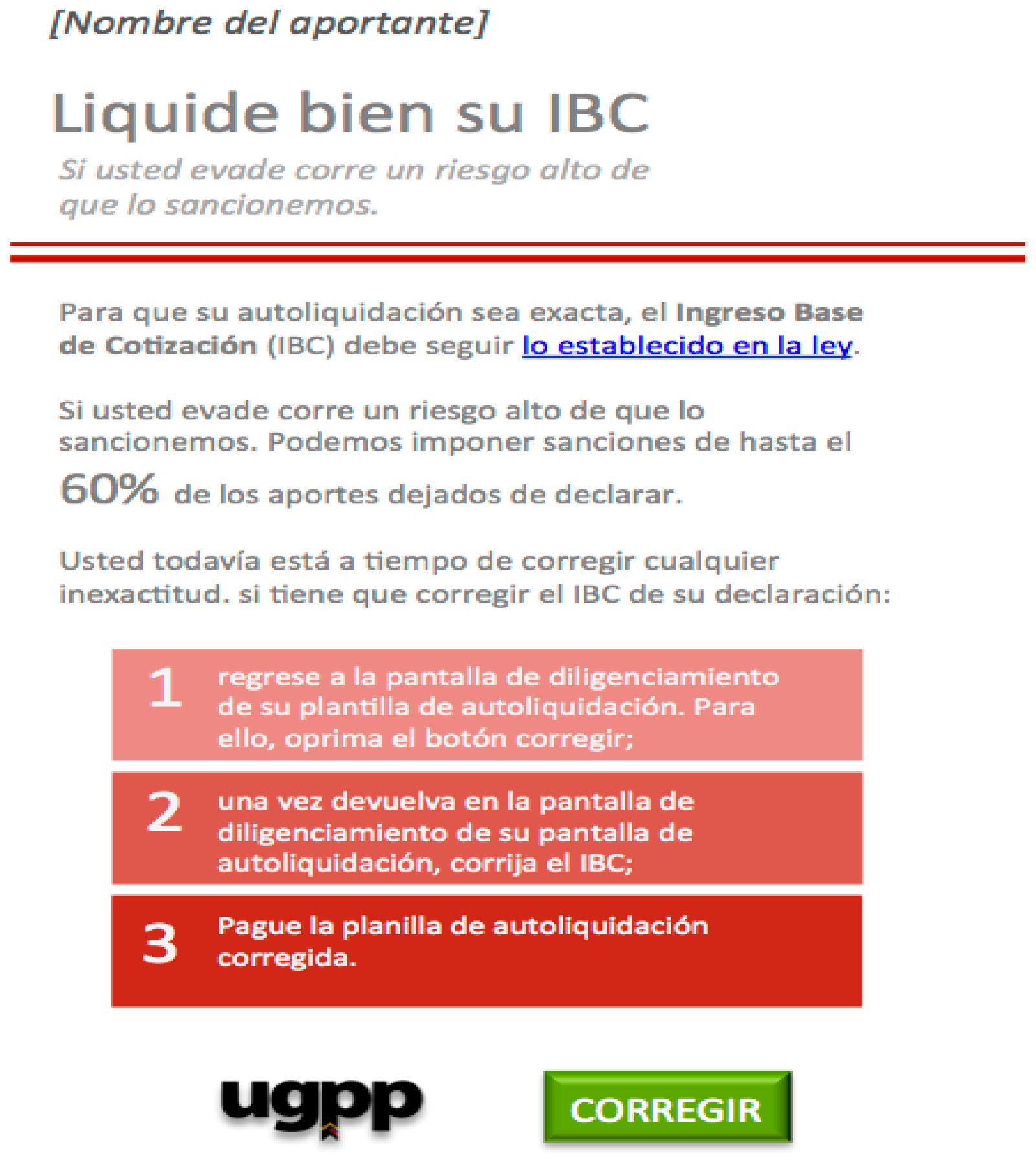

The ways in which these various messages were conveyed to individuals was identical across the messages and the operators. When an individual logged on to PILA, the individual’s name appeared, followed by the statement “Liquide bien su IBC”, which translates as “Pay your IBC correctly”, where IBC stands for Ingreso Base de Cotización or Income Base of Contribution. The various pop-up messages appeared as a nudge immediately below “Liquide bien su IBC”. Also, under each message there was additional information on how to make and correct any declaration of contributions, and this information was presented to contributors regardless of the specific message type that appeared to the contributor. For Message 7, there was no pop-up message; even so, the additional information on how to make and correct any declaration of contributions was shown to all contributors, including those who received Message 7. See the original Spanish version and the English translations of the messages in Appendix A, and see Appendix B for a screen shot of a typical message.

Overall, these messages were intended to influence an individual’s perceptions of audit and penalty rates, reminding individuals of the possible consequence of underreporting. They were also intended to remind an individual of possible benefits of the social protection contributions, either to the individual or to society. Finally, they were intended to influence an individual’s social norm of compliance. In all cases individuals were free to make any decision that they wished to make. Also, in all cases individuals saw these messages at precisely the time when they were making their reporting decision, on the assumption that the impact of the messages would then be most immediately and strongly felt.

It is important to remember that the “individual” receiving the message was of two different types: an individual making the reporting decision as an agent of a firm with multiple employees (a “company agent”), and an individual making the contribution on his or her own behalf as a “self-employed individual”. In our empirical analyses, we consider company agents and self-employed individuals separately. Self-employed individuals were slightly less than one-third (or 29.0 percent) of the subjects, with company agents constituting the remainder of the subjects.

The experiment was conducted through two operators (Asopagos and Pago Simple), both private companies that collect the payment of each individual and then transfer the payment to the agencies responsible for administering each type of contribution (i.e., pension funds, health care administrators, labor risk insurers, Cajas de Compensación Familiar, SENA, and ICBF).14 The Colombian system allows these operator companies to work as intermediaries between the individuals and all the other administrators who are part of the social protection system. These two operators sent the messages to 4797 randomly selected individuals (company agents and self-employed individuals) between September and November 2013. These 4797 individuals received a total of 7479 randomly selected messages, so that some individuals received more than one message. Of all individuals, 3606 individuals (75.1 percent) received only one message and 1191 individuals (24.9 percent) received two or more messages.15 Asopagos accounted for 3285 of the 4797 individuals (or 68.4 percent of the participating individuals), and for 5712 of the 7479 messages (or 76.4 percent of the messages). Pago Simple accounted for 1512 of the 4797 individuals and for 1767 of the 7479 messages. In our empirical analysis, we examine only the 3606 individuals (2259 individuals from Asopagos and 1347 individuals from Pago Simple) who received a single message.

For Asopagos, the dataset contains 3285 individuals who received a total of 5712 messages. Of these 3285 individuals, 2259 (68.8 percent) received just one message, and the other 1026 individuals (31.2 percent) received two or more messages. Over two-thirds of the messages were sent during the first month (September) of the study. The actual messages sent by Asopagos were evenly and uniformly distributed across most of the seven message types for the 2259 individuals who received just one message. For example, 364 individuals received Message 1, 349 subjects received Message 2, 343 individuals received Message 3, 345 individuals received Message 5, 356 individuals received Message 6, and 340 individuals received Message 7. The exception is Message 4, which exhibits a smaller frequency (162 individuals) because UGPP ultimately decided not to show this message, as noted earlier.

Even though most (70.8 percent) of the Asopagos messages were sent during the first month (September), during each month the distribution of the messages was uniform, at about 14 percent for each message, with Message 4 again having a lower frequency. Also, the distribution of the messages by the day of the week indicates that most of the messages were sent during the first days of each month instead of being uniformly distributed between all the days, and the distribution of the messages by the time of the day indicates a concentration during some hours. For example, about two-thirds of the messages were shown between 9:00 a.m. and 12:00 p.m., with the largest percentage of messages (26.0 percent) sent between 10:00 a.m. and 11:00 a.m.

For Pago Simple, the dataset contains 1767 observations that represent 1512 individuals. Of these 1512 individuals, 1347 individuals (89.1 percent) received one message, and 165 individuals (10.9 percent) received two or more messages. Overall, most of the same general patterns are exhibited for Pago Simple as for Asopagos (e.g., frequency by type of message and frequency by day and time of day), although the Pago Simple dataset was generated only in September 2013 and the dataset is considerably smaller.

It should be noted that we examine Asopagos and Pago Simple separately, rather than combining them into a single dataset. We do this separate examination because the two datasets are not strictly comparable, given the months of coverage for the two datasets. For Pago Simple, the experiment was held only during October 2013; for Asopagos, the experiment was held from September 2013 to November 2013, and most messages for Asopagos were sent during the first week of September. We also had some concerns about the comparability of data across months for each dataset taken alone. Given these concerns, we examine each dataset separately.

5. Results

As discussed earlier, our basic research question is simply stated: Do these pop-op messages nudge an individual to improve his or her compliance? To answer this question, we rely mainly on calculations of difference-in-differences (DID) measures of the impact of messages. We also conduct several robustness tests, including the use of DID regression analysis to determine the impact on reporting of the different messages. These analyses are based on comparing the declarations of “individuals” (either “company agents” or “self-employed individuals”) in the period in which they received the message (denoted “Month of Message”) versus the monthly average over the previous year (“Previous Year”), in order to smooth monthly variations. We focus on two types of declarations: the average “Pension Payment” per worker, and the average “Health Care Payment” per worker. We use the per worker measures in order to normalize comparisons across self-employed individuals (who were making payments for their own individual and personal benefit) and company agents (who were making payments on behalf of all of the workers in their firm). As noted, we focus on those individuals who received a single message in order to avoid confounding the effects of multiple messages on compliance, and we also examine the two operators separately due to lack of comparability across the two datasets. Importantly, as we discuss later, we also use two alternative measures for the appropriate baseline control group.

5.1. Difference-in-Differences Estimates with “Neutral Message 7 as Control Group”

Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 present simple “difference-in-differences” (DID) estimates of the impacts of messages on Health Care Payments and Pension Payments, by message type (e.g., Message 1 versus Message 2 and so on), by individual type (e.g., company agent versus self-employed), and by operator (e.g., Asopagos versus Pago Simple). In all of these tables, the baseline control group in the DID estimation is assumed to be individuals who received Message 7, the message intended to be a “neutral” message; these results are denoted “Neutral Message 7 as Control Group”.

Table 2.

Health Care Payments with “Neutral Message 7 as Control Group”—Asopagos.

Table 3.

Health Care Payments with “Neutral Message 7 as Control Group”—Pago Simple.

Table 4.

Pension Payments with “Neutral Message 7 as Control Group”—Asopagos.

Table 5.

Pension Payments with “Neutral Message 7 as Control Group”—Pago Simple.

However, before examining these tables, it is important to note that one impact of sending any message is that many individuals who started to declare their payments simply did not complete the process once a message of any type appeared. Overall, 19 percent of the individuals who made declarations in the month prior to the start of the controlled field experiment and who began to make declarations in the treatment period opted not to complete their on-line payments once any message appeared, and virtually all of this “decay” came from self-employed individuals. We are able to quantify this overall decay (again, 19 percent of the total number of individuals), but we do not have any information on the declarations in the treatment period of those individuals who chose to opt out of their payments. Even so, this decay suggests several possible effects of a pop-up message. One possible effect is that there may be technical problems with the PILA website that are present with the website and/or that are aggravated by the pop-up message. PILA officials acknowledge this possibility, but we have no way of investigating its likelihood.16 Another possible effect is that individuals (mainly self-employed individuals) may believe that their receipt of any type of message increased their visibility to the tax authorities, and they responded by an attempt to disappear from this surveillance, even if this attempt was unlikely to be ultimately successful. We estimated a logistic regression in an attempt to explain this decay, with the dependent variable equal to 1 if the individual opted out of the payment and 0 otherwise and with the various message types as independent variables (along with some individual characteristics like the size of the individual’s payment in the month prior to the treatment). None of the explanatory variables was statistically significant, indicating that the decay occurred evenly across all messages and that the decay did not depend on individual characteristics.17 It is in part for this reason that we believe that the use of individuals who received Message 7 as the baseline control group likely biases individual responses, even though Message 7 was intended to be a neutral message, making these results of questionable and uncertain value. It is also in part for this reason that we employ an alternative measure for the baseline control group, as discussed later.

Consider the information in Panel A of Table 2 on health care payments for company agents in the Asopagos dataset. A simple comparison of the health care payments for, say, company agents who were sent Message 1 (“Any contributor can be audited”) decreased on average their declarations in the Month of Message versus the monthly Average of the Previous Year by 2710 COP. However, company agents who were sent Message 7 (or the neutral message) also decreased their declarations, by 936 COP, and it is necessary to control for this difference in measuring the impact of Message 1; that is, we must calculate the difference-in-differences (DID) estimate by subtracting the Message 7 difference from the Message 1 difference to find the appropriate measure of the impact of Message 1. This DID estimate equals −1774 COP (= [−2710] − [−936]), which indicates that those company agents receiving Message 1 decreased their health care payments by 1774 COP relative to those receiving Message 7. The other DID estimates are calculated in a similar way.

These DID estimates indicate quite mixed impacts of the various messages, with no consistent pattern for these impacts. For health care payments made by company agents for the two operators (Table 2 and Table 3, Panel A), the impact of the messages was variable, sometimes increasing declarations and sometimes decreasing them. Only Message 3 (“You face a high risk of being sanctioned if you evade”) had a consistent, positive, and statistically significant impact on declarations for both operators. The other messages generally had opposite effects for the two operators. In contrast, for health care payments made by self-employed individuals (Table 2 and Table 3, Panel B), the impact of the various messages was in nearly all cases to decrease declarations, often by very large amounts; however, these impacts are not statistically significant given the large standard errors of the estimates, especially for Message 7.

Similarly, the impacts of the messages on pension payments were also quite mixed (Table 4 and Table 5). For pension payments made by company agents (Table 4 and Table 5, Panel A), the impact of the messages was again quite variable, sometimes increasing declarations and sometimes decreasing them. Indeed, no message had the same positive or negative impact on pension payments of company agents for the two different operators. In contrast, for self-employed individuals, pension payments always decreased in response to any of the messages (Table 4 and Table 5, Panel B), with quite large negative effects of all messages; again, however, these impacts are not statistically significant given the large standard errors.

Given the very mixed pattern of these responses, we believe that the use of individuals who received Message 7 as the baseline control group generates results that have little use, or whose meaning is difficult to ascertain. In the next section, we present our analyses of messages using an alternative baseline control group that, we believe, gives more meaningful results.

5.2. Difference-in-Differences Estimates with “No Message as Control Group”

The DID estimates in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 all use individuals who received Message 7 as the baseline control group, on the basis of the so-called “neutral” content of this message. However, as we have argued earlier, it seems unlikely that there can exist any message from the Government that is truly neutral. The mere act of sending a message already implies that more attention is given to a certain act (e.g., tax compliance), and it seems likely that individuals will respond in some way even to a supposedly neutral message. This is a potential concern with most all field studies on compliance that make use of some kind of purported neutral message from the tax authority to individuals, calling into question their findings.18 Indeed, our prior finding that many individuals who started to declare their payments did not complete the process once a message of any type appeared provides strong evidence that an individual will treat any message as an indicator of increased government scrutiny, with the potential for significant behavioral effects.

However, for one of the operators (Asopagos) we are able to establish an alternative baseline control group that, we believe, is an improved and unbiased measure for the baseline measure of individual declarations of health care and pension payments. This alternative baseline control group uses the monthly average of individual payments for the relevant program across all individuals who made contributions to Asopagos in the previous 12 months, before the pop-up message experiment was introduced by the UGPP. More precisely, instead of using the average monthly payment by individuals receiving Message 7 as the control group, we instead use the average monthly payment across all individuals who made contributions to Asopagos before the experiment was initiated and also during the experiment but who were not contacted directly or indirectly by the UGPP during the pre-experiment period or during the experiment. Unfortunately, we do not have such an alternative baseline control group for Pago Simple, and, given the lack of comparability across the two datasets from the two operators, we are not able to use the Asopagos baseline control group for the Pago Simple baseline control group. The two operators work in different parts of the country and serve different clienteles, so those who made their contributions to Asopagos are not representative of those who made their contributions to Pago Simple. Regardless, the results for Asopagos provide strong evidence that this alternative baseline control group is a more accurate measure of individual contributions for use in the DID calculations. We denote this alternative measure “No Message as Control Group”.

These results are presented in Table 6. These results for the “No Message as Control Group” now exhibit considerably more (if not complete) consistency, especially for self-employed individuals. For the most part, self-employed individuals respond to the receipt of any message by increasing their declarations, sometimes by considerable amounts. For example, self-employed declarations of health care payments to Asopagos (Table 6, Panel A, column 3) generally increase by significant amounts, even for Message 7. Similarly, self-employed declarations of pension payments to Asopagos (Table 6, Panel B, column 3) also increase by large amounts. In contrast, the responses of company agents remain somewhat mixed for types of contributions, sometimes increasing and sometimes decreasing but with no consistent pattern (Table 6, Panels A and B, column 2).

Table 6.

Difference-in-Differences Estimates with No Message as Control Group—Asopagos.

This erratic response by company agents likely reflects the possibility that an individual completing the declarations as a company agent on behalf of a company that employs many workers is largely unaffected by nudges that appeal to audits, sanctions, or social norms. Rather, a company agent is well aware of third-party information that is conveyed to the tax administration, and he or she is not as influenced by other considerations that reflect audits, penalties, or social norms. In any event, the responses of the company agent are in fact still somewhat erratic. In contrast, an individual completing the declarations on his or her own behalf has a more direct and personal stake in the declarations, and responds accordingly and systematically to the messages.

5.3. Robustness Tests

We use several robustness tests to examine our results.19 We compared declarations in the month in which the message was received versus the declarations in the immediately preceding month, rather than the average monthly payment over the previous 12 months. We made comparisons for total contributions (rather than for health care and pension payments separately). We tried alternative groupings of the messages.20 We also used regression estimates in order to control for other potential factors that may affect individual declarations, such as the region of the country in which the individuals are located (e.g., Caribbean, Antioquia, Pacific, Eastern Plains, South Central), the sector of the economy in which the individual works (e.g., public versus private), or the type of payroll (e.g., electronic versus manual). In all cases, we used our two alternative measures of the baseline control group. These results generally confirm the results that we report in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, and we do not report them.21

6. Conclusions

Our controlled field experiment shows mixed results for the impact of messages of various types on tax reporting. For company agents and self-employed individuals, our results indicate that the receipt of any message of any type leads to a significant decay in their participation. Due to this decay, it is essential that empirical work establishes a control group of individuals who are not affected by the receipt of a message. Our results indicate clearly that this control group is unlikely to include any individuals who receive any message, even a message that is believed to be “neutral”. When the appropriate control group is established, we find that self-employed individuals generally increase their declarations, often by large amounts, when they receive a message from the government. Individuals who are making declarations on behalf of their company (or company agents) are less likely to respond to messages in a systematic and predictable way, perhaps because their own personal benefits and costs are unlikely to be influenced by the nudge that a message is trying to convey.

These mixed results are consistent with some other field studies that find similarly varied results. At present, there is no widely accepted explanation for these differential results across studies. Our own belief is that our results are likely attributable to two features of our design, one positive and one negative. First, our design examines how messages affect individual choices at exactly the time when they make their reporting decisions, so that the individual’s choices have immediate effects. Second, our design examines how messages affect individual choices only at a single point in time, a one-time intervention that is common to most other field studies, so that the persistence of any responses is unknown. Future work is needed to demonstrate convincing reasons for differential results across field studies. It would be especially useful to examine the dynamic effects of interventions, to determine whether any impact (positive or negative) will persist after a single intervention or whether persistent interventions are needed to change permanently individual behavior.22

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to all sections of this research.

Funding

This research was supported by a consulting agreement between Unidad de Gestión Pensional y Contribuciones Parafiscales (UGPP) and Gandour Consultores, Bogota, Colombia.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Editor and to several anonymous reviewers for many helpful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Mensajes/Messages (Spanish/English)

1. Cualquier aportante puede ser auditado.

- [Nombre del aportante] para que su autoliquidación sea exacta, el Ingreso Base de Cotización (IBC) debe reflejar el ingreso real del periodo.

- Los auditores de la UGPP revisamos constantemente la exactitud de la información presentada en las planillas de autoliquidación de los aportantes. En el último periodo, hemos realizado auditorías a personas que ejercen actividades económicas similares a la suya. Su planilla de autoliquidación para este periodo podría ser auditada en cualquier momento.

- Si el IBC registrado en la planilla no refleja el ingreso real durante el mismo periodo, todavía está a tiempo de corregirlo. Para esto debe:

- (1)

- presionar el botón que encontrará debajo de este mensaje que lo regresará a la pantalla de diligenciamiento de su plantilla de autoliquidación;

- (2)

- una vez esté en la planilla debe corregirla sustituyendo el valor que había determinado para el IBC por el valor de los ingresos reales durante el mismo periodo;

- (3)

- pagar la planilla de autoliquidación corregida.

1. Any contributor can be audited.

- [Name of the contributor], for your contribution statement to be accurate, the reported income (Ingreso Base de Cotización-IBC) must reflect the real income for the period.

- The auditors of the UGPP constantly review the accuracy of the information presented in the contributors’ declaration and payment statements. In the last period, we have audited people with economic activities similar to yours. Your statement for this period could be audited at any time.

- If the income registered in the form does not reflect the real income during the same period, there is still time to correct it. For this you must:

- (1)

- press the button that you will find below this message, which will return you to the filing screen of your contribution filing template;

- (2)

- modify the contribution statement by substituting the reported income (IBC) with the real income for the same period;

- (3)

- pay the modified contribution statement.

2. Cuando auditamos evasores los detectamos.

- [Nombre del aportante] para que su autoliquidación sea exacta, el Ingreso Base de Cotización (IBC) debe reflejar el ingreso real del periodo.

- Los auditores de la UGPP contrastamos el valor del IBC reportado por el aportante con la información reportada en otras bases de datos públicas y privadas. Hemos detectado [ %] de evasores entre los casos auditados.

- Si el IBC registrado en la planilla no refleja el ingreso real durante el mismo periodo, todavía está a tiempo de corregirlo. Para esto debe:

- (1)

- presionar el botón que encontrará debajo de este mensaje que lo regresará a la pantalla de diligenciamiento de su plantilla de autoliquidación;

- (2)

- una vez esté en la planilla debe corregirla sustituyendo el valor que había determinado para el IBC por el valor de los ingresos reales durante el mismo periodo;

- (3)

- pagar la planilla de autoliquidación corregida.

2. When we audit contributions evaders, we detect them.

- [Name of the contributor], for your contribution statement to be accurate, the reported income (Ingreso Base de Cotización-IBC) must reflect the real income for the period.

- The auditors of the UGPP compare the income (IBC) reported by the contributor with information reported in other public and private databases. We have detected ( ) [%] of evaders among the audited cases.

- If the income registered in the form does not reflect the real income during the same period, there is still time to correct it. For this you must:

- (1)

- press the button that you will find below this message, which will return you to the filing screen of your contribution filing template;

- (2)

- modify the contribution statement by substituting the reported income (IBC) with the real income for the same period;

- (3)

- pay the modified contribution statement.

3. Si usted evade corre un riesgo alto de que lo sancionemos.

- [Nombre del aportante] para que su autoliquidación sea exacta, el Ingreso Base de Cotización (IBC) debe reflejar el ingreso real del periodo.

- Si usted evade corre un riesgo alto de que lo sancionemos. Podemos imponer sanciones de hasta el 60% de los aportes dejados de declarar.

- Si el IBC registrado en la planilla no refleja el ingreso real durante el mismo periodo, todavía está a tiempo de corregirlo. Para esto debe:

- (1)

- presionar el botón que encontrará debajo de este mensaje que lo regresará a la pantalla de diligenciamiento de su plantilla de autoliquidación;

- (2)

- una vez esté en la planilla debe corregirla sustituyendo el valor que había determinado para el IBC por el valor de los ingresos reales durante el mismo periodo;

- (3)

- pagar la planilla de autoliquidación corregida.

3. You face a high risk of being sanctioned if you evade.

- [Name of the contributor], for your contribution statement to be accurate, the reported income (Ingreso Base de Cotización-IBC) must reflect the real income for the period.

- You face a high risk of being sanctioned if you evade. We can impose sanctions of up to 60% of the contributions left to declare.

- If the income registered in the form does not reflect the real income during the same period, there is still time to correct it. For this you must:

- (1)

- press the button that you will find below this message, which will return you to the filin screen of your contribution filing template;

- (2)

- modify the contribution statement by substituting the reported income (IBC) with the real income for the same period;

- (3)

- pay the modified contribution statement.

4. Usted será auditado.

- [Nombre del aportante] para que su autoliquidación sea exacta, el Ingreso Base de Cotización (IBC) debe reflejar el ingreso real del periodo.

- La planilla de autoliquidación que acaba de validar para este periodo ha sido seleccionada por los auditores de la UGPP para ser auditada. En el proceso que adelantaremos revisaremos que el valor del IBC que especificó en la planilla refleje el ingreso real de ese periodo en el porcentaje aplicable. Los aportantes que corrigen sus planillas antes del pago se evitan sanciones por inexactitud.

- Si el IBC registrado en la planilla no refleja el ingreso real durante el mismo periodo, todavía está a tiempo de corregirlo. Para esto debe:

- (1)

- presionar el botón que encontrará debajo de este mensaje que lo regresará a la pantalla de diligenciamiento de su plantilla de autoliquidación;

- (2)

- una vez esté en la planilla debe corregirla sustituyendo el valor que había determinado para el IBC por el valor de los ingresos reales durante el mismo periodo;

- (3)

- pagar la planilla de autoliquidación corregida.

4. You will be audited

- [Name of the contributor], for your contribution statement to be accurate, the reported income (Ingreso Base de Cotización-IBC) must reflect the real income for the period.

- Your contribution filing for this period has been selected by the auditors of the UGPP to be audited. We will review that your declared income matches the real income of the period. Contributors who correct their filings before payment avoid penalties for inaccuracy.

- If the income registered in the form does not reflect the real income during the same period, there is still time to correct it. For this you must:

- (1)

- press the button that you will find below this message, which will return you to the filing screen of your contribution filing template;

- (2)

- modify the contribution statement by substituting the reported income (IBC) with the real income for the same period;

- (3)

- pay the modified contribution statement.

5. Si su autoliquidación es exacta se beneficiará.

- [Nombre del aportante] para que su autoliquidación sea exacta, el Ingreso Base de Cotización (IBC) debe reflejar el ingreso real del periodo.

- Los cotizantes se benefician de la exactitud de su autoliquidación cuando reciben el valor proporcional que corresponde al ingreso real en incapacidades, licencias y mesada pensional. Si usted declara un IBC por un valor menor al ingreso real del periodo, el cotizante recibirán beneficios por montos inferiores a los que recibiría una persona que ha declarado un IBC que refleja ingresos reales.

- Si el IBC registrado en la planilla no refleja el ingreso real durante el mismo periodo, todavía está a tiempo de corregirlo. Para esto debe:

- (1)

- presionar el botón que encontrará debajo de este mensaje que lo regresará a la pantalla de diligenciamiento de su plantilla de autoliquidación;

- (2)

- una vez esté en la planilla debe corregirla sustituyendo el valor que había determinado para el IBC por el valor de los ingresos reales durante el mismo periodo;

- (3)

- pagar la planilla de autoliquidación corregida.

5. You will benefit if your contribution filing is accurate.

- [Name of the contributor], for your contribution statement to be accurate, the reported income (Ingreso Base de Cotización-IBC) must reflect the real income for the period.

- Contributors benefit from the accuracy of their filings when they receive a proportional value of their real income in disability allowances, paid leaves and pensions. If you declare a lower income, you will receive lower benefits than those that would be received by a person who has declared its real income.

- If the income registered in the form does not reflect the real income during the same period, there is still time to correct it. For this you must:

- (1)

- press the button that you will find below this message, which will return you to the filing screen of your contribution filing template;

- (2)

- modify the contribution statement by substituting the reported income (IBC) with the real income for the same period;

- (3)

- pay the modified contribution statement.

6. Si su autoliquidación es exacta todos nos beneficiamos.

- [Nombre del aportante] para que su autoliquidación sea exacta, el Ingreso Base de Cotización (IBC) debe reflejar el ingreso real del periodo.

- Si su autoliquidación es exacta se mejora el bienestar de los colombianos. Sus contribuciones atienden la protección integral de los niños y adolescentes, la calidad del servicio de salud, el acceso de manera gratuita a una formación profesional integral para aumentar la productividad del país, la protección de los trabajadores frente a riesgos asociados con sus labores y el derecho a una mesada pensional oportuna y confiable. En el último periodo [ ] aportantes han mejorado el bienestar de los colombianos con sus aportes.

- Si el IBC registrado en la planilla no refleja el ingreso real durante el mismo periodo, todavía está a tiempo de corregirlo. Para esto debe:

- (1)

- presionar el botón que encontrará debajo de este mensaje que lo regresará a la pantalla de diligenciamiento de su plantilla de autoliquidación;

- (2)

- una vez esté en la planilla debe corregirla sustituyendo el valor que había determinado para el IBC por el valor de los ingresos reales durante el mismo periodo;

- (3)

- pagar la planilla de autoliquidación corregida.

6. We all benefit from accurate contribution filings.

- [Name of the contributor], for your contribution statement to be accurate, the reported income (Ingreso Base de Cotización-IBC) must reflect the real income for the period.

- If your contribution filing is accurate, the well-being of Colombians is improved. Your contributions protect children and youngs, improve the quality of health services, give free access to comprehensive professional training to increase the country’s productivity, the protection of workers against risks associated with their work and the right to a timely and reliable pension allowance. In the last period [ ] contributors have improved the welfare of Colombians with their contributions.

- If the income registered in the form does not reflect the real income during the same period, there is still time to correct it. For this you must:

- (1)

- press the button that you will find below this message, which will return you to the filing screen of your contribution filing template;

- (2)

- modify the contribution statement by substituting the reported income (IBC) with the real income for the same period;

- (3)

- pay the modified contribution statement.

7. [No se especifica mensaje.]

- [Nombre del aportante] para que su autoliquidación sea exacta, el Ingreso Base de Cotización (IBC) debe reflejar el ingreso real del periodo.

- Si el IBC registrado en la planilla no refleja el ingreso real durante el mismo periodo, todavía está a tiempo de corregirlo. Para esto debe:

- (1)

- presionar el botón que encontrará debajo de este mensaje que lo regresará a la pantalla de diligenciamiento de su plantilla de autoliquidación;

- (2)

- una vez esté en la planilla debe corregirla sustituyendo el valor que había determinado para el IBC por el valor de los ingresos reales durante el mismo periodo;

- (3)

- pagar la planilla de autoliquidación corregida.

7. [No message is specified.]

- [Name of the contributor], for your contribution statement to be accurate, the reported income (Ingreso Base de Cotización-IBC) must reflect the real income for the period.

- If the income registered in the form does not reflect the real income during the same period, there is still time to correct it. For this you must:

- (1)

- press the button that you will find below this message, which will return you to the filing screen of your contribution filing template;

- (2)

- modify the contribution statement by substituting the reported income (IBC) with the real income for the same period;

- (3)

- pay the modified contribution statement.

Appendix B. Screenshot of Mensajes/Message 3

(“You face a high risk of being sanctioned if you evade.”)

References

- Cowell, F.A. Cheating the Government: The Economics of Evasion; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni, J.; Erard, B.; Feinstein, J. Tax Compliance. J. Econ. Lit. 1998, 36, 818–860. [Google Scholar]

- Slemrod, J.; Yitzhaki, S. Tax Avoidance, Evasion, and Administration. In Handbook of Public Economics; Auerbach, A.J., Feldstein, M., Eds.; Elsevier Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; New York, NY, USA, 2002; Volume 3, pp. 1423–1470. [Google Scholar]

- Mascagni, G. From the Lab to the Field: A Review of Tax Experiments. J. Econ. Surv. 2018, 32, 273–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemrod, J. Tax Compliance and Enforcement. J. Econ Lit. in press.

- Alm, J. Measuring, Explaining, and Controlling Tax Evasion: Lessons from Theory, Experiments, and Field Studies. Int. Tax Public Financ. 2012, 19, 54–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J. What Motivates Tax Compliance? J. Econ. Surv. 2019, 33, 353–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thaler, R.H.; Sunstein, C.R. Nudge—Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness; Yale University Press: New Haven, CN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mullainathan, S.; Schwartzstein, J.; Congdon, W.J. A Reduced-form Approach to Behavioral Public Finance. Ann. Rev. Econ. 2012, 4, 511–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetty, R. Behavioral Economics and Public Policy: A Pragmatic Perspective. Am. Econ. Rev. Pap. Proc. 2015, 105, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunstein, C.R. The Ethics of Influence: Government in the Age of Behavioral Science; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, A. The Origins of Behavioural Public Policy; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rabin, M. Psychology and Economics. J. Econ. Lit. 1998, 36, 11–46. [Google Scholar]

- Camerer, C.F.; Loewenstein, G.F.; Rabin, M. (Eds.) Advances in Behavioral Economics; Russell Sage Foundation and Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery, E.J.; Slemrod, J. (Eds.) Behavioral Public Finance; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Congdon, W.J.; Kling, J.R.; Mullainathan, S. Policy and Choice—Public Finance through the Lens of Behavioral Economics; The Brookings Institution Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ariely, D. Predictably Irrational—The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions; Harper Collins: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, A. The Psychology of Taxation; Martin Robertson: Oxford, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler, E. The Economic Psychology of Tax Behavior; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Elster, J. The Cement of Society—A Study of Social Order; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Schmölders, G. Das Irrationale in der Offentlichen Finanzwirtschaft (The Irrational in Public Finance); Suhrkamp: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Frey, B. Not Just for the Money—An Economic Theory of Personal Motivation; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchler, E.; Hoelzl, E.; Wahl, I. Enforced Versus Voluntary Tax Compliance: The “Slippery Slope” Framework. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 210–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBarnet, D. Crime, Compliance, and Control; Ashgate/Dartmouth Publishers Ltd.: Burlington, VT, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, V. Defiance in Taxation and Governance—Resisting and Dismissing Authority in a Democracy; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Luttmer, E.F.; Singhal, M. Tax Morale. J. Econ. Perspect. 2014, 28, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slemrod, J.; Blumenthal, M.; Charles, C.C. Taxpayer Response to an Increased Probability of Audit: Evidence from a Controlled Experiment in Minnesota. J. Public Econ. 2001, 79, 455–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellner, G.; Sausgruber, R.; Traxler, C. Testing Enforcement Strategies in the Field: Thread, Moral Appeal, and Social Information. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 2013, 11, 634–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boning, W.C.; Guyton, J.; Hodge, R.H.; Slemrod, J.; Troiano, U. Heard It Through the Grapevine: Direct and Network Effects of a Tax Enforcement Field Experiment; NBER Working Paper 24305; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gangl, K.; Torgler, B.; Kirchler, E.; Hofmann, E. Effects of Supervision on Tax Compliance: Evidence from a Field Experiment in Austria. Econ. Lett. 2014, 123, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallsworth, M. The Use of Field Experiments to Increase Tax Compliance. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 2014, 30, 658–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallsworth, M.; List, J.A.; Metcalfe, R.D.; Vlaev, I. The Behavioralist as Tax Collector: Using Natural Field Experiments to Enhance Tax Compliance. J. Public Econ. 2017, 148, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, G.S.; Reckers, P.M.; Sanders, D.L. Increasing Tax Compliance in Washington State: A Field Experiment. Natl. Tax J. 2010, 63, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, M.; Christian, C.; Slemrod, J.; Smith, M.G. Do Normative Appeals Affect Tax Compliance? Evidence from a Controlled Experiment in Minnesota. Natl. Tax J. 2001, 54, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M. Misperception of Social Norms about Tax Compliance: From Theory to Intervention. J. Econ. Psychol. 2005, 26, 862–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M. A Letter from the Tax Office: Compliance Effects of Informational and Interpersonal Justice. Soc. Justice Res. 2006, 19, 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, M.; Taylor, N. An Experimental Evaluation of Tax-reporting Schedules: A Case of Evidence-based Tax Administration. J. Public Econ. 2004, 88, 2785–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B. Moral-suasion: An Alternative Tax Policy Strategy? Evidence from a Controlled Field Experiment in Switzerland. Econ. Gov. 2004, 5, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgler, B. A Field Experiment on Moral Suasion and Tax Compliance Focusing on Under-declaration and Over-deduction. Finanz Arch. Public Financ. Anal. 2013, 69, 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bott, K.M.; Cappelen, A.W.; Sorensen, E.; Tungodden, B. You’ve Got Mail: A Randomised Field Experiment on Tax Evasion; NHH (Norwegian School of Economics) Department of Economics Discussion Paper October 2017; Norwegian School of Economics: Bergen, Norway, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, L.; Scartascini, C. Tax Compliance and Enforcement in the Pampas: Evidence from a Field Experiment. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2015, 116, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomeranz, D. No Taxation Without Representation: Deterrence and Self-enforcement in the Value Added Tax. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015, 105, 2539–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Luzuriaga, A.; Scartascini, C. Compliance Spillovers Across Taxes: The Role of Penalties and Detection. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2019, 164, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Carpio, L. Are the Neighbors Cheating? Evidence from a Social Norm Experiment on Property Taxes in Peru; INSEAD Working Paper; INSEAD: Fontainebleau, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, T.; Monestier, F.; Piñeiro, R.; Rosenblatt, F.; Tuñón, G. Is Paying Taxes Habit Forming? Theory and Evidence from Uruguay; University of California-Berkeley Working Paper; University of California-Berkeley: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ortega, D.; Scartascini, C. Does the Delivery Method of a Message Matter? Results from a Field Experiment; Inter-American Development Bank Working Paper; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, E.; Scartascini, C. Imperfect Attention in Public Policy: A Field Experiment During A Tax Amnesty in Argentina; Inter-American Development Bank Working Paper; Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bérgolo, M.L.; Ceni, R.; Cruces, G.; Giaccobasso, M.; Perez-Truglia, R. Tax Audits as Scarecrows: Evidence from a Large-Scale Field Experiment; IZA Discussion Paper No. 12335; IZA—Institute of Labor Economics: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Gandour Consultores. First Estimate of Evasion of the Social Protection System; Gandour Consultores: Bogota, Colombia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, J.; López, H. Payroll Taxes in Colombia. In Fiscal Reform in Colombia—Problems and Prospects; Richard, M., Bird, J., Poterba, M., Slemrod, J., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 191–223. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.S. Crime and Punishment—An Economic Approach. J. Polit. Econ. 1968, 76, 169–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allingham, M.G.; Sandmo, A. Income Tax Evasion: A Theoretical Analysis. J. Public Econ. 1972, 1, 323–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; McClelland, G.H.; Schulze, W.D. Why Do People Pay Taxes? J. Public Econ. 1992, 48, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; Cherry, T.L.; Jones, M.; McKee, M. Social Programs as Positive Inducements for Tax Participation. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2012, 84, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graetz, M.J.; Wilde, L.L. The Economics of Tax Compliance: Fact and Fantasy. Natl. Tax J. 1985, 38, 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Elffers, H. Income Tax Evasion: Theory and Measurement; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Deventer, The Netherlands, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Torgler, B. Tax Compliance and Tax Morale: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Slemrod, J. Cheating Ourselves: The Economics of Tax Evasion. J. Econ. Perspect. 2007, 21, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; Bourdeaux, C.J. Applying Behavioral Economics to Public Budgeting and Finance. Rev. Public Econ./Hacienda Publica Esp. 2014, 3, 91–134. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office and Nesta. EAST: Four Simple Ways to Apply Behavioural Insights; Cabinet Office and Nesta: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alm, J.; McClelland, G.H.; Schulze, W.D. Changing the Social Norm of Compliance by Voting. Kyklos 1999, 52, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alm, J.; Torgler, B. Do Ethics Matter? Tax Compliance and Morality. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 635–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, G.W.; List, J.A. Field Experiments. J. Econ. Lit. 2004, 42, 1009–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | See [,,,,,,] for comprehensive surveys of this growing literature. |

| 2 | It is somewhat surprising that there is no consensus on the exact definition of a “nudge”. Perhaps the most widely accepted definition is by [], who define a nudge as “…any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behavior in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives”. |

| 3 | For various academic discussions of behavioral economics, see [,,,]. For more “popular” discussions, see [,,]. |

| 4 | The notion of a “social norm” of tax compliance has emerged from work in the psychology of taxation [,]. Although difficult to define precisely, a social norm can be distinguished by the feature that it is process-oriented, unlike the outcome-orientation of individual rationality []. A social norm therefore represents a pattern of behavior that is judged in a similar way by others and that is sustained in part by social approval or disapproval. If others behave according to some socially accepted mode of behavior, then the individual will behave appropriately; if others do not so behave, then the individual will respond in kind. The presence of a social norm is also consistent with a range of other approaches that incorporate similar notions. For example, see [,,,,]. See [] for a review of much of this literature. |

| 5 | See [] for a survey of field experiments on tax compliance. |

| 6 | The current exchange between the United States dollar (USD) and the COP is 1 USD = 3430 COP. |

| 7 | Note that [] present evidence that the specific way in which a message is delivered affects its impact, mainly by affecting the saliency, clarity, and credibility of the message. They also emphasize that messages may have unintended consequences. |

| 8 | An important exception is [], who also examine in their field experiment the behavior of individuals who do not receive any letter. We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for this observation. |

| 9 | The description presented here is based on the regulatory regime at the time that the controlled field experiment was designed and implemented, in 2013. Since then, the Government of Colombia has gone through various fiscal reforms that have changed some aspects of the initial regulatory regime. We detail these changes when they are relevant to the discussion. See [] for a detailed discussion of the Colombian system of payroll taxes and contributions. |

| 10 | There are some exceptions to these rates. For income lower than 4 times the minimum wage, the rate is 16 percent; for income between 4 and 16 times the minimum wage, the rate is 17 percent; above 16 times the minimum wage, the rate increases by 0.2 percent for each minimum wage until the rate reaches 18 percent. Again, see [] for a detailed discussion. |

| 11 | Again, see [,,,,,,] for comprehensive surveys of this literature. |

| 12 | See [,,,,,,], among many others, for discussions of the limitations of the standard economic model of tax compliance. For a somewhat contrary view, see [,]. |

| 13 | Each message conveyed information beyond a simple statement. For example, Message 1 started by telling individuals “Any contributor can be audited”. Message 1 also told individuals that:

The other messages also provided similar types of additional information, with the exception of Message 7. See Appendix A for details on the messages. |