A Position-Based Fluid Method with Dynamic Smoothing Length

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fluid Simulation Using the Position-Based Fluid (PBF) Method

2.1. Introduction to the Position-Based Fluid (PBF) Method

2.2. Framework of the Position-Based Fluid (PBF) Algorithm

| Algorithm 1. Position-Based Fluid (PBF) Simulation Procedure |

| For each particle do: | apply forces | predict position End For each particle do: | find neighboring particles End while (iter < solverIterations) do: | For each particle do: | calculate End | For each particle do: | calculate | perform collision detection and response End For each particle do: | update position End End while For each particle do: | update velocity | apply vorticity confinement and XSPH viscosity | update position End |

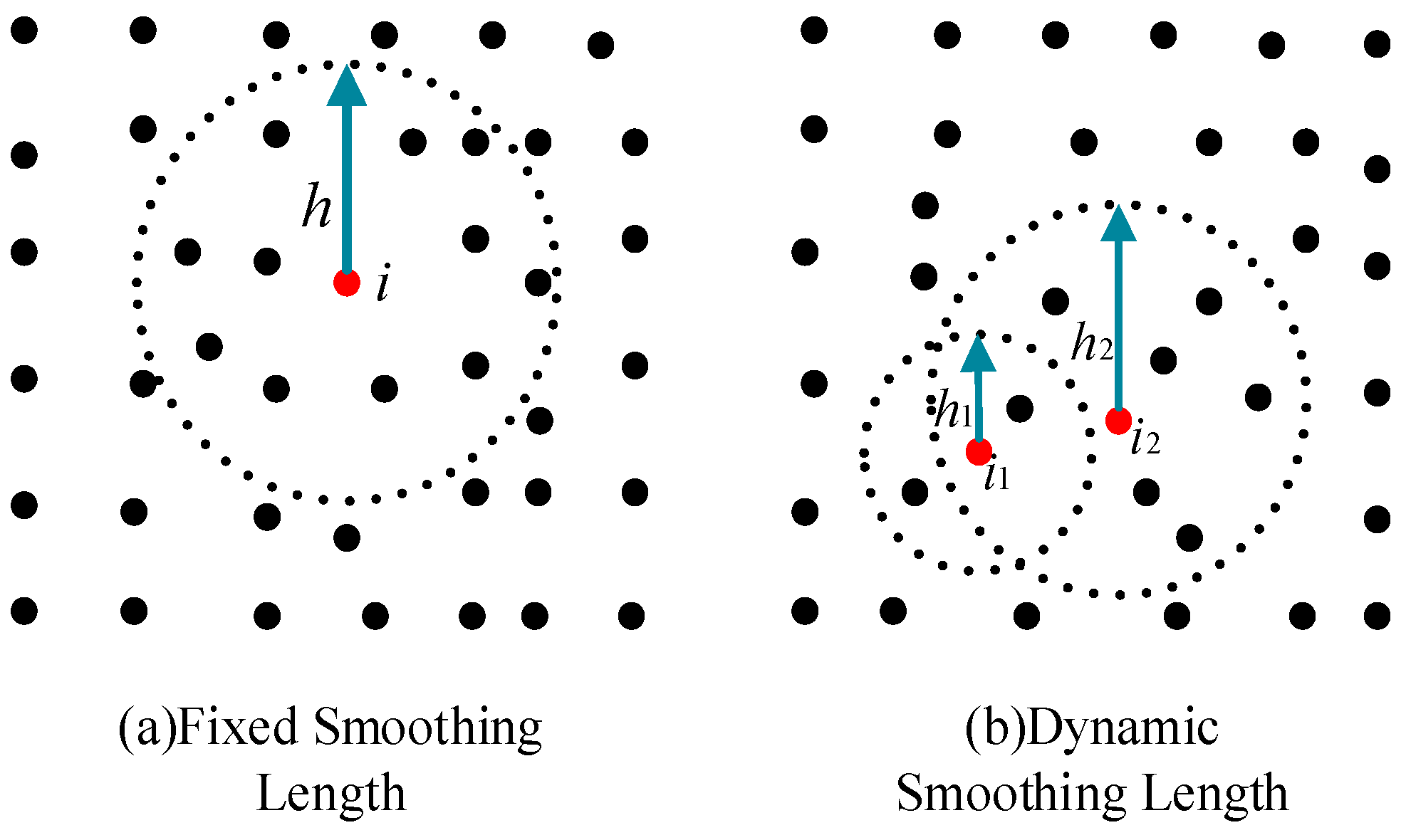

3. Research on Dynamic Smoothing Length

3.1. Dynamic Smoothing Length Method

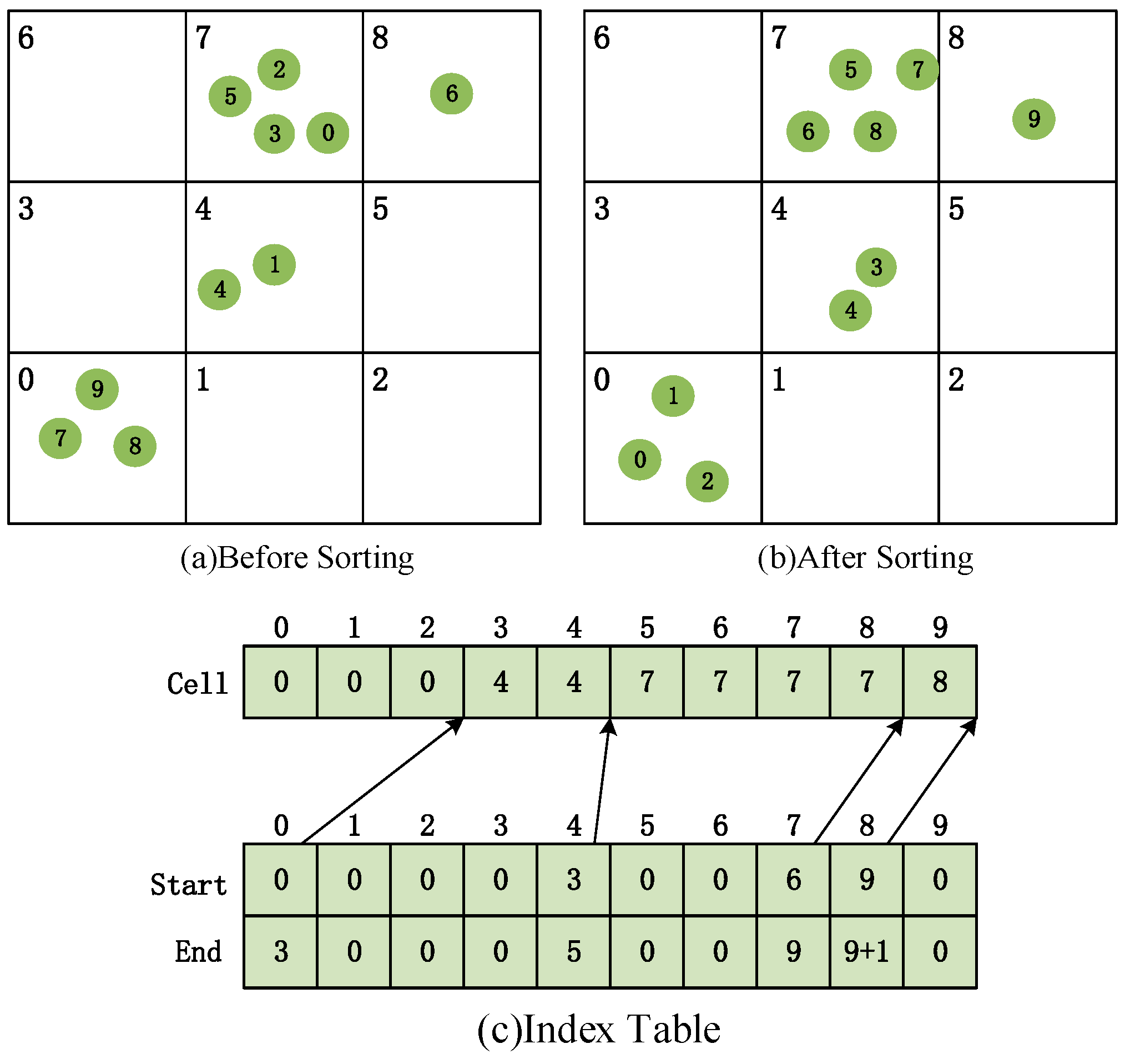

3.2. Neighbor Search Method for Dynamic Smoothing Length

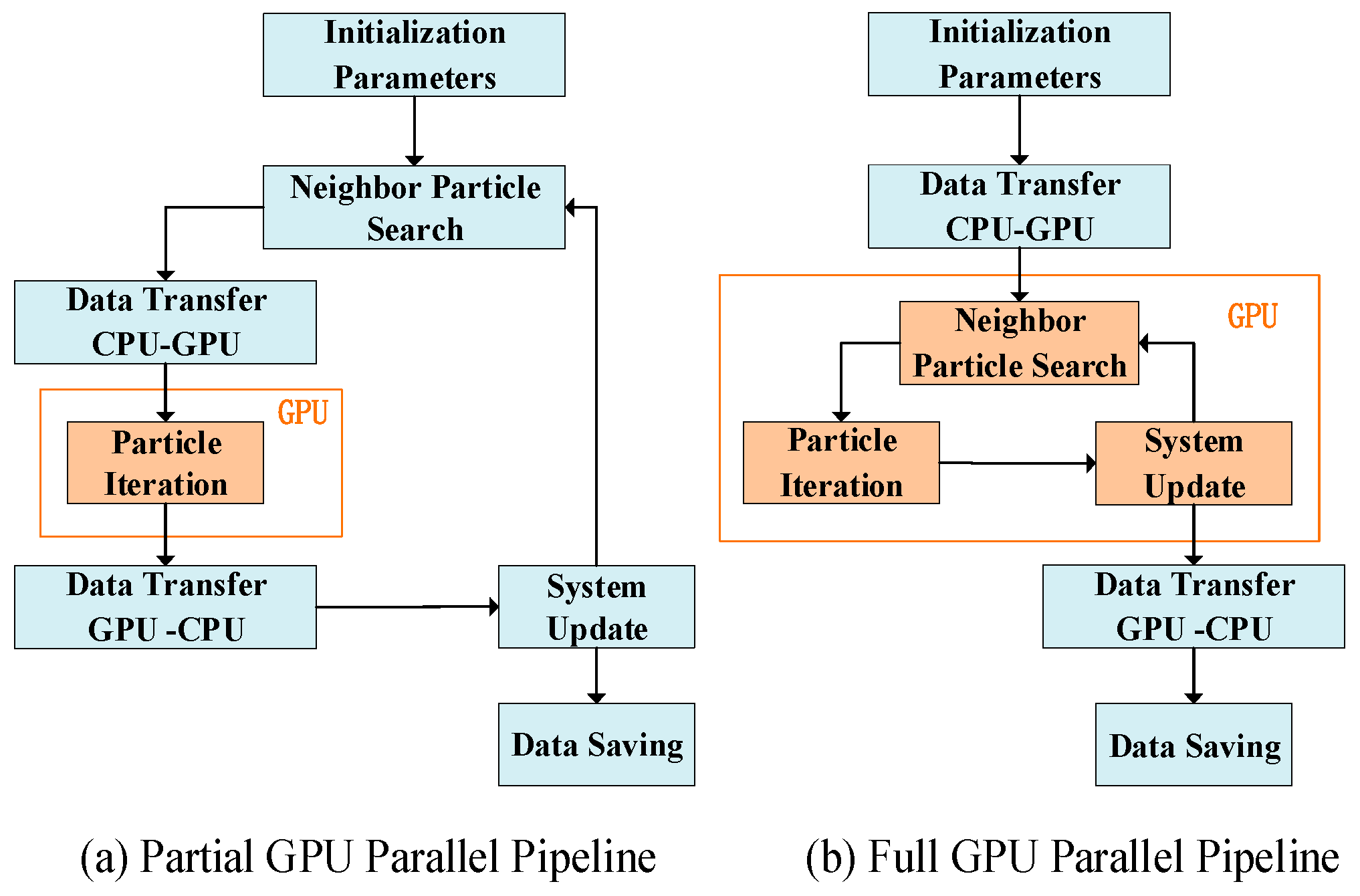

3.3. GPU Parallelization Method

3.4. Algorithm Framework for Dynamic Smoothing Length in Position-Based Fluids

| Algorithm 2. Dynamic Smoothing Length Simulation Procedure for Position-Based Fluids |

| For each particle do: | apply forces | adaptive smoothing length adjustment (new) | predict position End For each particle do: | find neighboring particles using adaptive smoothing length (modified) End while (iter < solverIterations) do: | For each particle do | | calculate λ with adaptive smoothing length (modified) | End | For each particle do: | | calculate Δp with adaptive smoothing length (modified) | | perform collision detection and response | End | For each particle do: | | update position | End End For each particle do: | update velocity | update position End |

3.5. Analysis of Computational and Memory Overhead

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Implementation Environment

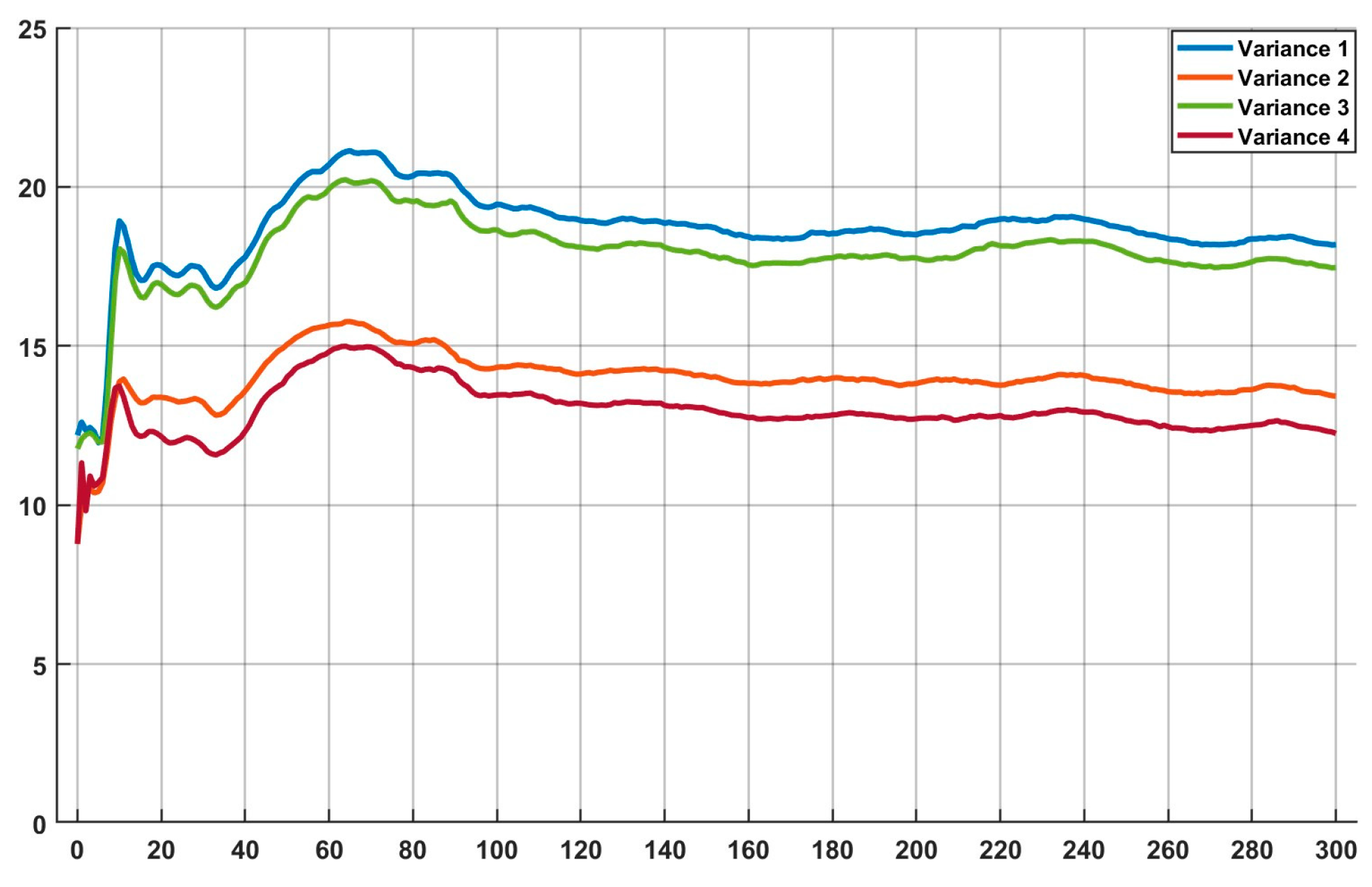

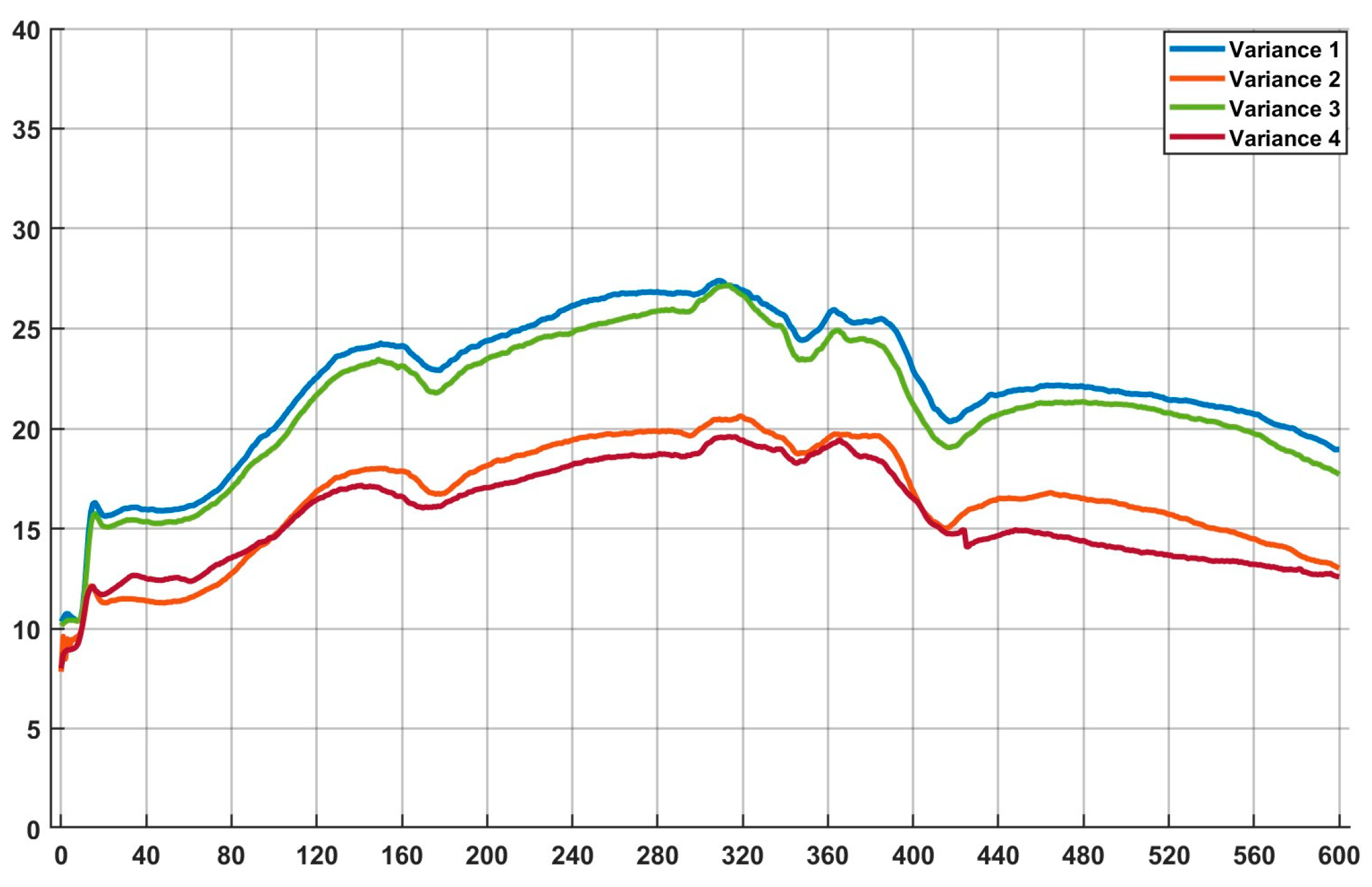

4.2. Neighbor Variance Comparison

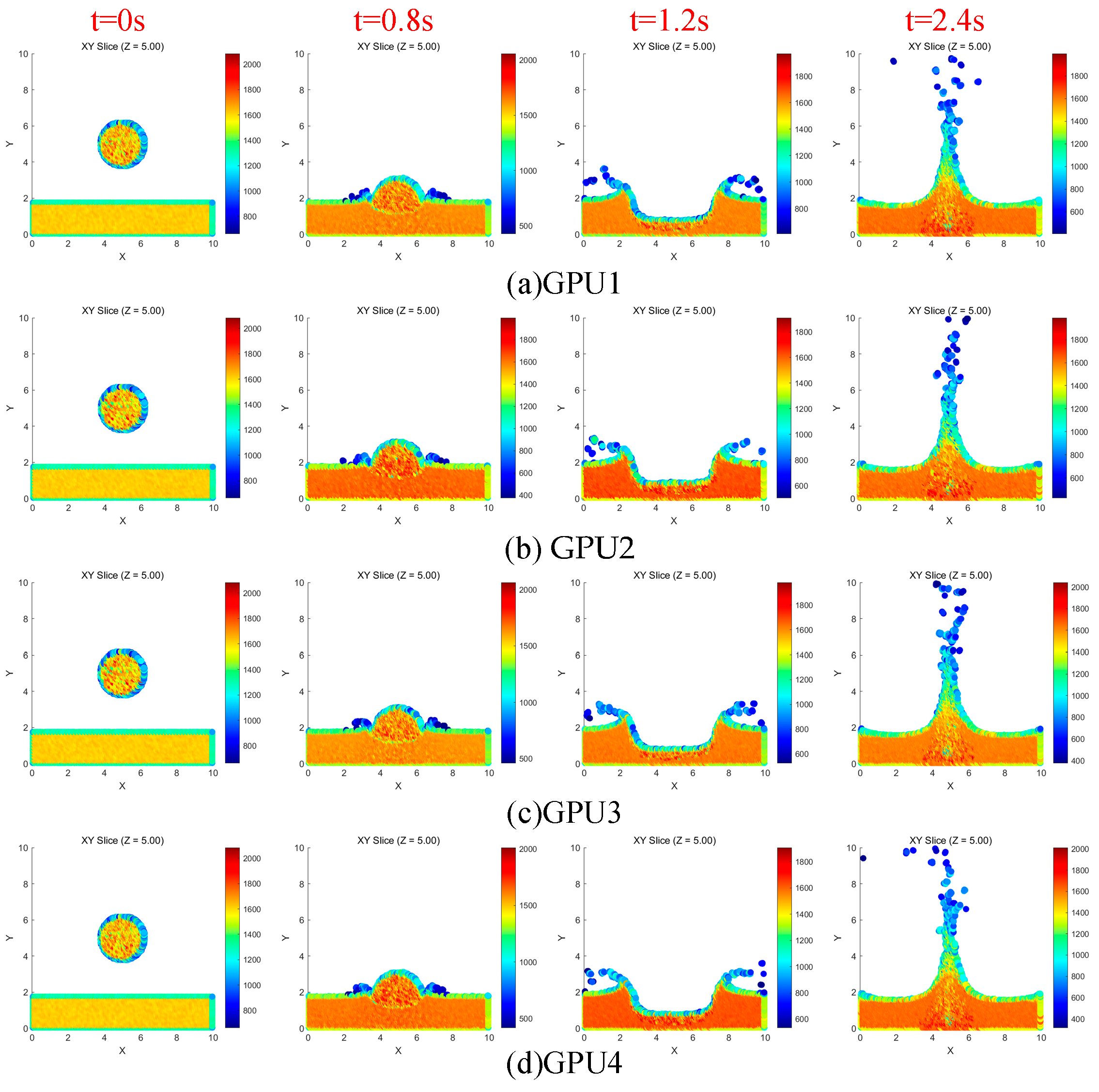

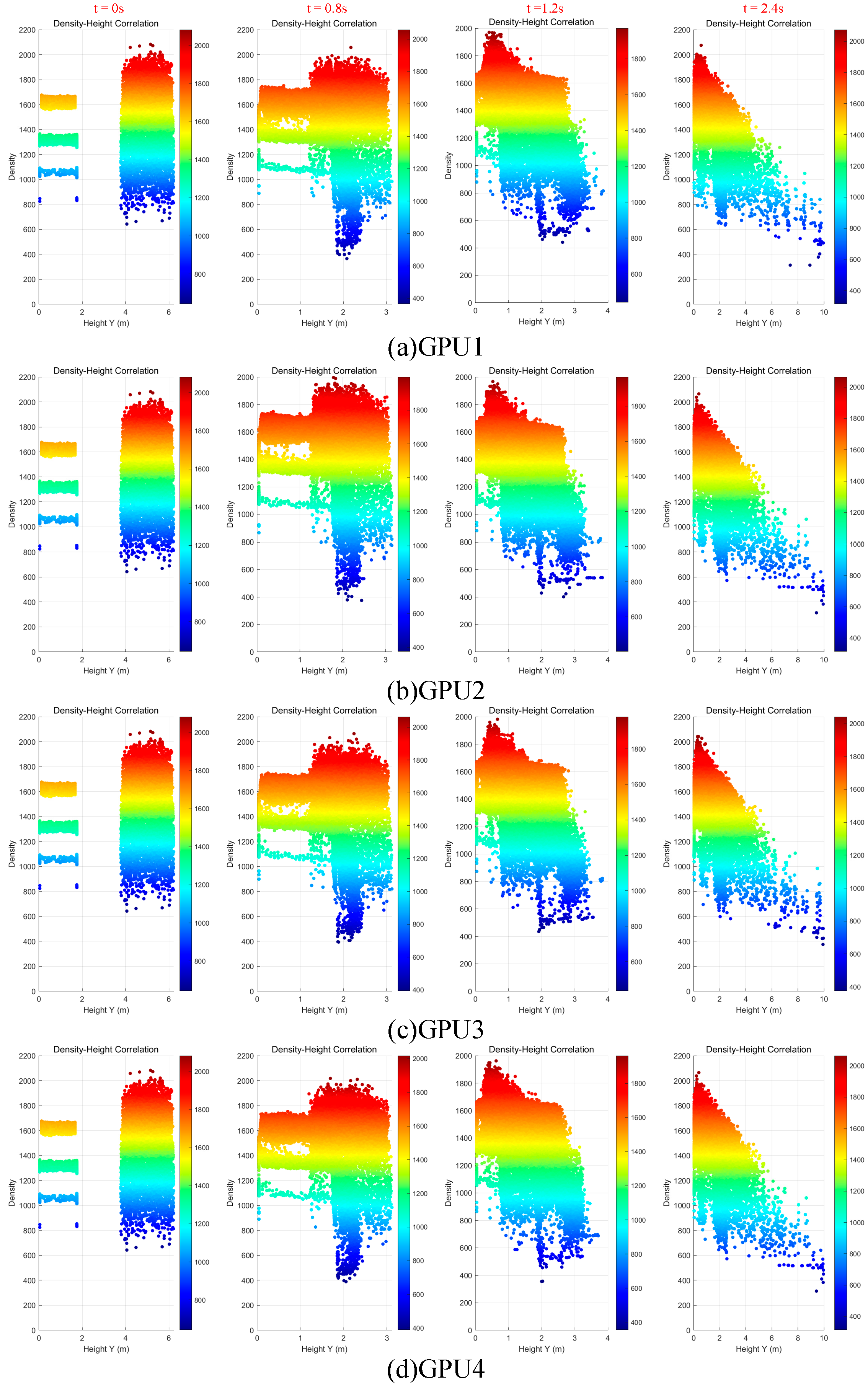

4.3. Visualization Analysis of Fluid Density Distribution

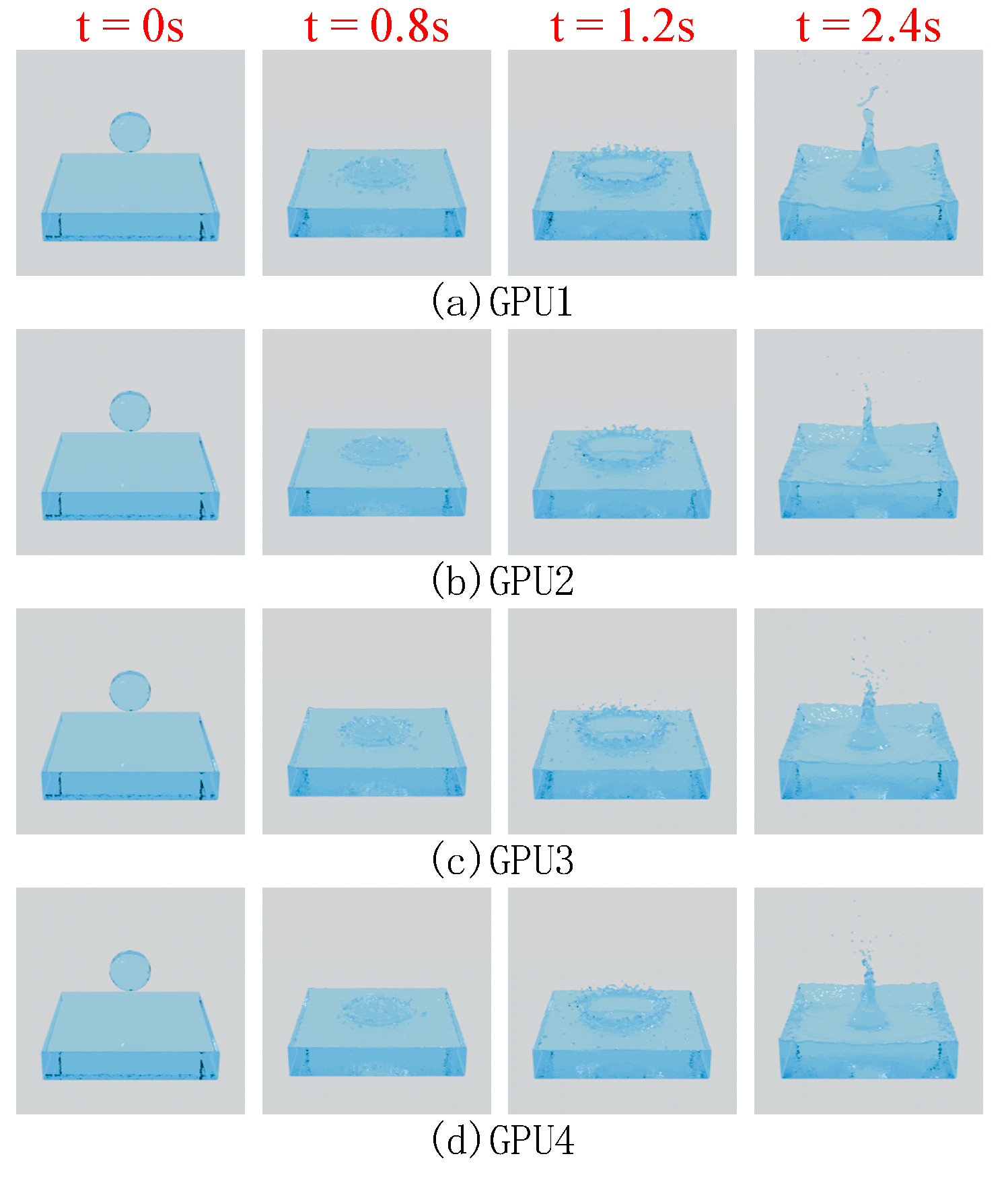

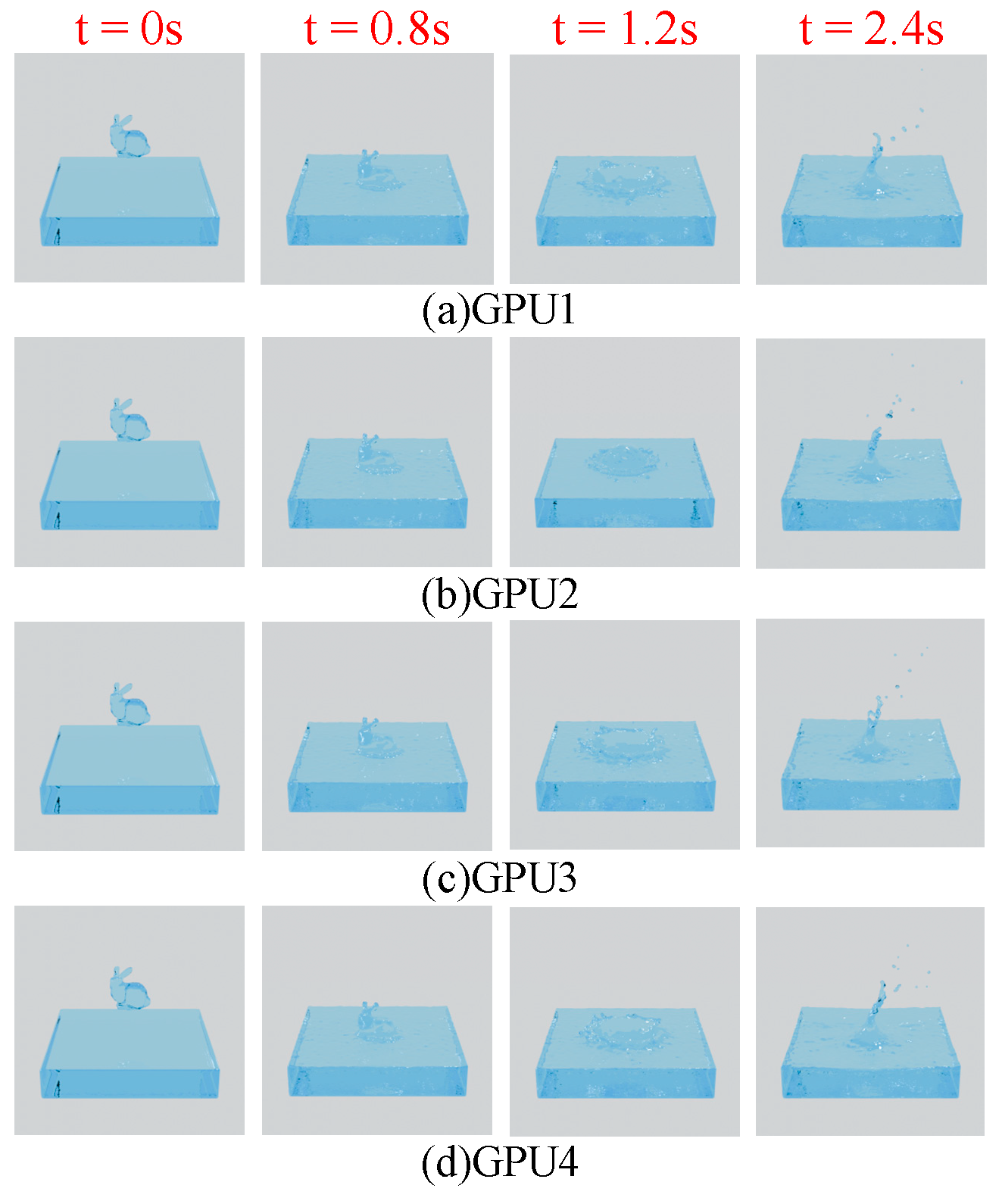

4.4. Free-Surface Simulation

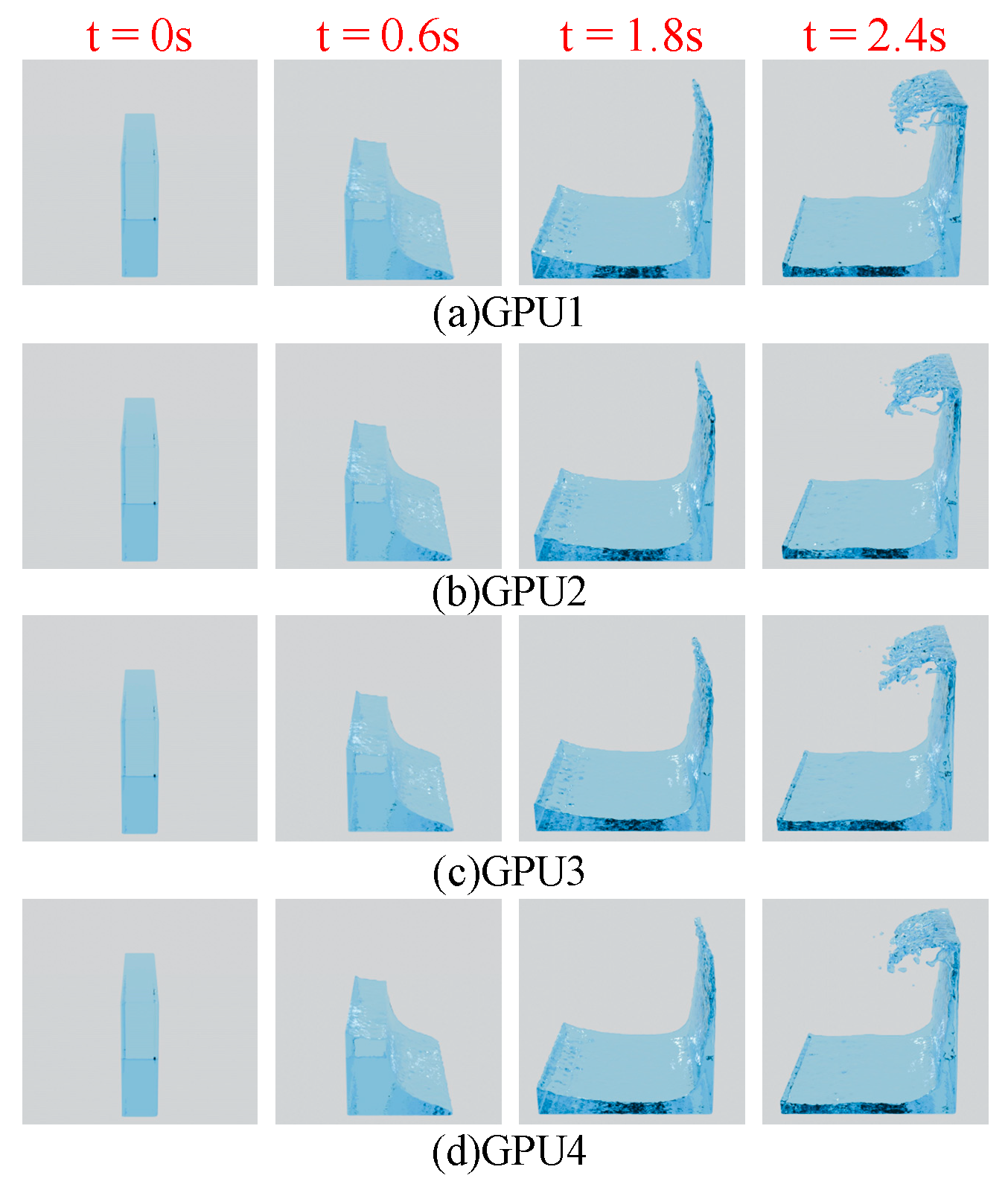

4.5. Dam Break Simulation

4.6. Analysis of Million-Particle Simulation Experiments

4.7. Visual Results

4.8. Strategy Comparison and Applicable Scenarios

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stam, J. Stable fluids. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, Los Angeles, CA, USA, 8–13 August 1999; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA; Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.: Carrollton, TX, USA, 1999; pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- LeVeque, R.J. Finite Difference Methods for Ordinary and Partial Differential Equations: Steady-State and Time-Dependent Problems; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Antoci, C.; Gallati, M.; Sibilla, S. Numerical simulation of fluid-structure interaction by SPH. Comput. Struct. 2007, 85, 879–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M.; Charypar, D.; Gross, M. Particle-based fluid simulation for interactive applications. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics Symposium on Computer Animation, San Diego, CA, USA, 26–27 July 2003; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.; Teschner, M. Weakly Compressible SPH for Free Surface Flows. In Proceedings of the 2007 ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics Symposium on Computer Animation, San Diego, CA, USA, 2–4 August 2007; Eurographics Association: Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 209–217. [Google Scholar]

- Violeau, D.; Rogers, B.D. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) for free-surface flows: Past, present and future. J. Hydraul. Res. 2016, 54, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alduan, I.; Otaduy, M.A. SPH Granular Flow with Friction and Cohesion. In Proceedings of the 2011 ACM SIGGRAPH/Eurographics Symposium on Computer Animation, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–7 August 2011; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Solenthaler, B.; Pajarola, R. Predictive-corrective incompressible SPH. ACM Trans. Graph. 2009, 28, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodin, K.; Lacoursiere, C.; Servin, M. Constraint Fluids. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2012, 18, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q. Fluid Simulation Based on Position-Based Dynamics Framework. Mod. Comput. Prof. Ed. 2018, 25, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Macklin, M.; Müller, M. Position based fluids. ACM Trans. Graph. 2013, 32, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Li, H.; Cai, R.; Chen, B.F. An SPH liquid simulation method based on adaptive smoothing length. Comput. Appl. Res. 2020, 37, 2871–2875. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, R. An Adaptive SPH Method Based on Neighbor Particle Density-Weighted Average. Master’s Thesis, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2021. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P.; Jin, A. Application of GPU neighbor search method in SPH algorithm for aeolian sand flow. Comput. Appl. Softw. 2025, 42, 221–226. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xing, X.; Peijie, S.; Huahai, Z.; Wang, L.M. Parallel Implementation of Three-Dimensional Lattice Boltzmann Method on Multi-GPU Platforms. Front. Data Comput. 2025, 7, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X. Research on GPU-Accelerated SPH with Improved Linked-List Search and Its Application to Free Surface Flow. Master’s Thesis, Guangxi University, Nanning, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Schechter, H.; Bridson, R. Ghost SPH for Animating Water. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2012, 31, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, J.J. SPH without a Tensile Instability. J. Comput. Phys. 2000, 159, 290–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, J.M.; Crespo, A.J.C.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Optimization strategies for CPU and GPU implementations of a smoothed particle hydrodynamics method. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2013, 184, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, P.; Schlegel, P.; Solenthaler, B.; Pajarola, R. Interactive SPH simulation and rendering on the GPU. In Proceedings of the Eurographics/ACM SIGGRAPH Symposium on Computer Animation, Madrid, Spain, 2–4 July 2010; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Long, T. Numerical Simulation of Dam Break Energy Dissipation Using SPH-GPU Parallel Method with Improved Linked-List Search. Water Resour. Power 2025, 43, 133–137+99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.; Li, B.T. Multi-GPU thermal lattice Boltzmann simulations using OpenACC and MPI. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 201, 123649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.T.; Zhang, X.R.; Su, Z.J.; He, Q.L. Application of Deep Learning Methods in Computational Fluid Dynamics. J. Sichuan Univ. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2025, 62, 1254–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.A.; Cheng, L.; Shi, K.Q.; Ou, M.Y.; Zhu, H.N. Unsteady Fluid Prediction Based on Multi-Task Graph Neural Network. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 24, 11733–11740. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, W.; Mei, G. Machine Learning-Based VOF Method for Two-Dimensional Fluid Simulation. Shipbuild. China 2024, 65, 244–253. [Google Scholar]

| Device | Model | Core Count | Memory (GB) | Clock Frequency (GHz) | Compute Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | AMD Ryzen 7 4800H | 8 | 16 | 2.9 | - |

| GPU | GTX 1650 | 896 | 4 | 1.49 | 7.5 |

| Simulation Methods | Particle | tsim/ms | Speed-Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | 56,339 | 1332.02 | — |

| GPU1 | 25.30 | 52.63 | |

| GPU2 | 19.46 | 68.42 | |

| GPU3 | 24.33 | 54.73 | |

| GPU4 | 18.29 | 72.80 | |

| CPU | 300,592 | 7851.63 | — |

| GPU1 | 126.51 | 62.05 | |

| GPU2 | 99.93 | 78.56 | |

| GPU3 | 117.20 | 66.99 | |

| GPU4 | 84.34 | 93.08 | |

| CPU | 592,565 | 15,715.73 | — |

| GPU1 | 230.70 | 68.11 | |

| GPU2 | 195.01 | 80.58 | |

| GPU3 | 226.99 | 69.23 | |

| GPU4 | 177.72 | 88.42 |

| Simulation Methods | Particle | tsim/ms | Speed-Up |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | 58,960 | 1438.84 | — |

| GPU1 | 25.71 | 55.95 | |

| GPU2 | 24.12 | 59.62 | |

| GPU3 | 24.83 | 57.93 | |

| GPU4 | 21.88 | 65.76 | |

| CPU | 203,665 | 5464.48 | — |

| GPU1 | 89.74 | 60.89 | |

| GPU2 | 79.93 | 68.36 | |

| GPU3 | 87.71 | 62.3 | |

| GPU4 | 68.85 | 79.36 | |

| CPU | 407,885 | 10,587.29 | — |

| GPU1 | 155.37 | 68.14 | |

| GPU2 | 141.84 | 74.64 | |

| GPU3 | 146.99 | 72.02 | |

| GPU4 | 131.84 | 80.30 |

| Simulation Methods | ∆t | Particle | tsim/ms |

|---|---|---|---|

| GPU1 | 0.001 | 1,948,712 | 862.07 |

| GPU2 | 0.001 | 828.50 | |

| GPU3 | 0.001 | 840.47 | |

| GPU4 | 0.001 | 709.22 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zou, C.; Li, X. A Position-Based Fluid Method with Dynamic Smoothing Length. Computers 2026, 15, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010011

Zou C, Li X. A Position-Based Fluid Method with Dynamic Smoothing Length. Computers. 2026; 15(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleZou, Changjun, and Xirun Li. 2026. "A Position-Based Fluid Method with Dynamic Smoothing Length" Computers 15, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010011

APA StyleZou, C., & Li, X. (2026). A Position-Based Fluid Method with Dynamic Smoothing Length. Computers, 15(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers15010011