Topic Modeling of Positive and Negative Reviews of Soulslike Video Games

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: What are the themes and topics discussed in positive and negative reviews of Soulslike games?

- RQ2: Are there any significant differences in topics between positive and negative reviews of Soulslike games?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Steam Digital Game Distribution Platform

2.2. The Scraping Process

- High difficulty and frequent player character death as progression feedback;

- Deliberate, timing-based combat involving dodging, parrying, or stamina management;

- Interconnected level design that encourages exploration;

- Narrative conveyed through environmental storytelling rather than direct exposition.

2.3. Data Analysis

- The dataset was restricted to reviews tagged as English by Steam metadata.

- A corpus was created with the tm package’s corpus() function using its default parameters.

- A document-feature matrix (DFM) was generated using quanteda::dfm() with remove_punct = TRUE and remove = stopwords(“english”) to remove punctuation and stopwords, respectively.

- Tokens shorter than two characters were removed with min_nchar = 2 in dfm_remove().

- Rare terms appearing in fewer than five documents were removed using min_docfreq = 5 in dfm_trim().

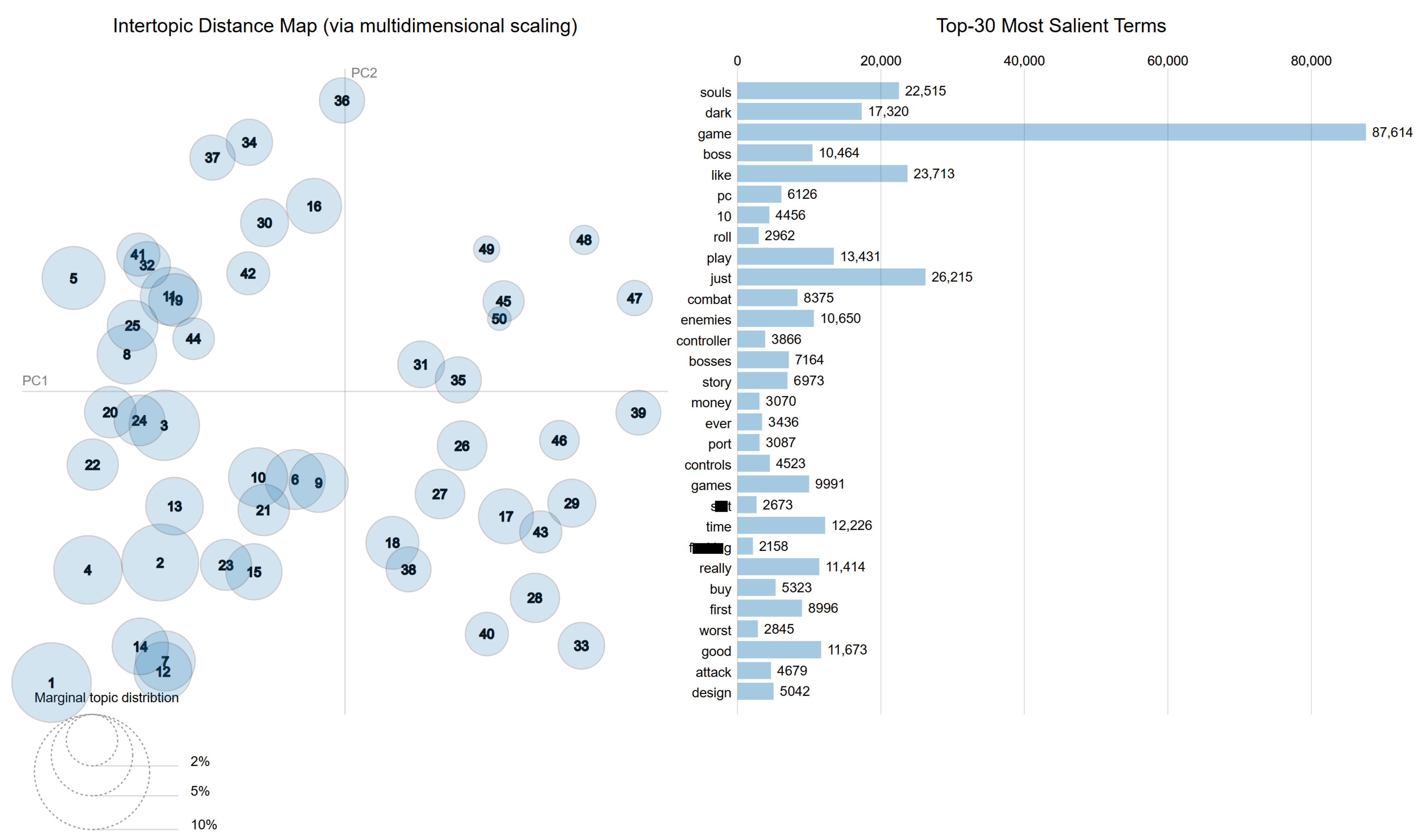

3. Results

3.1. General Results

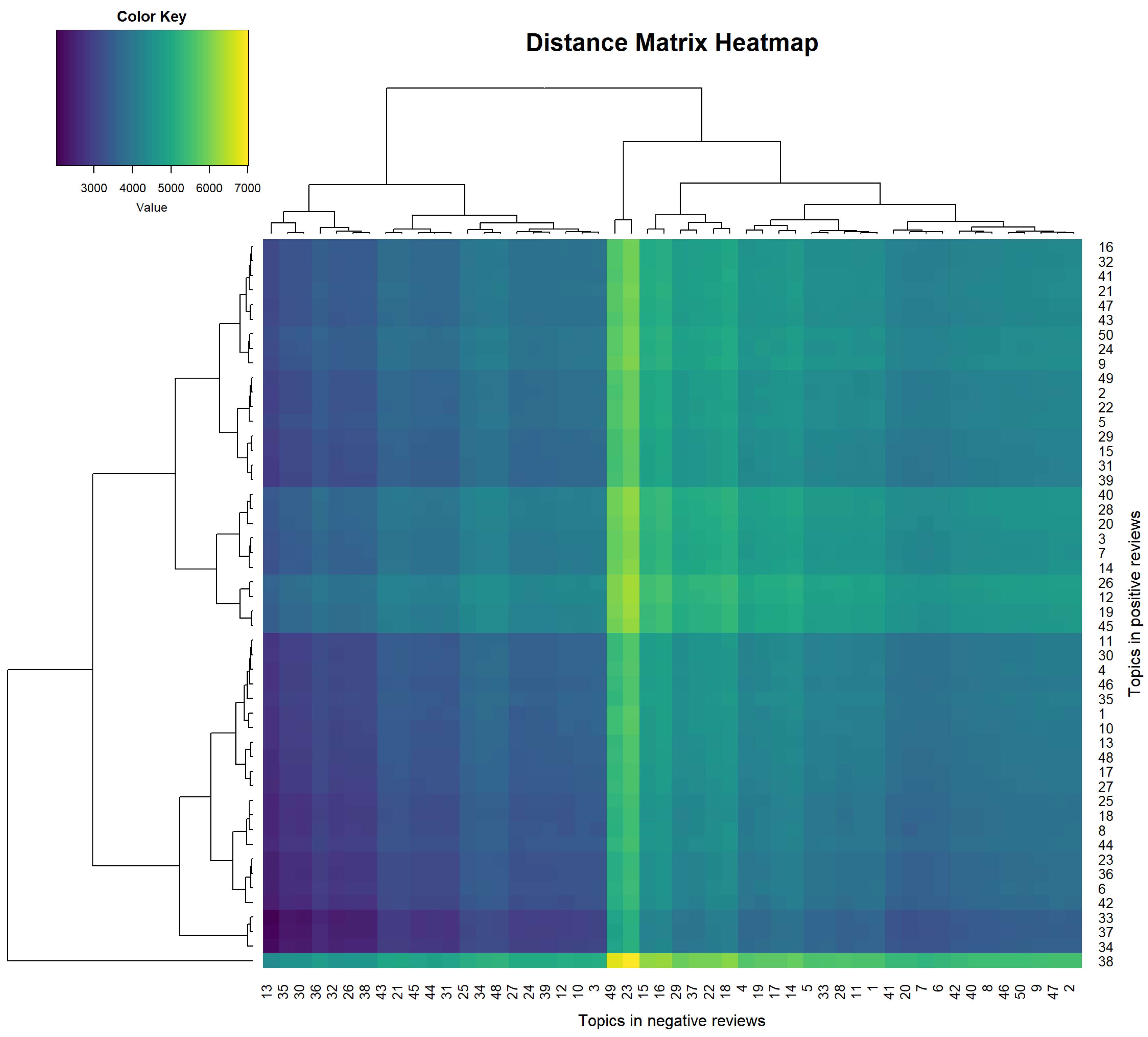

3.2. Topics in Positive Reviews

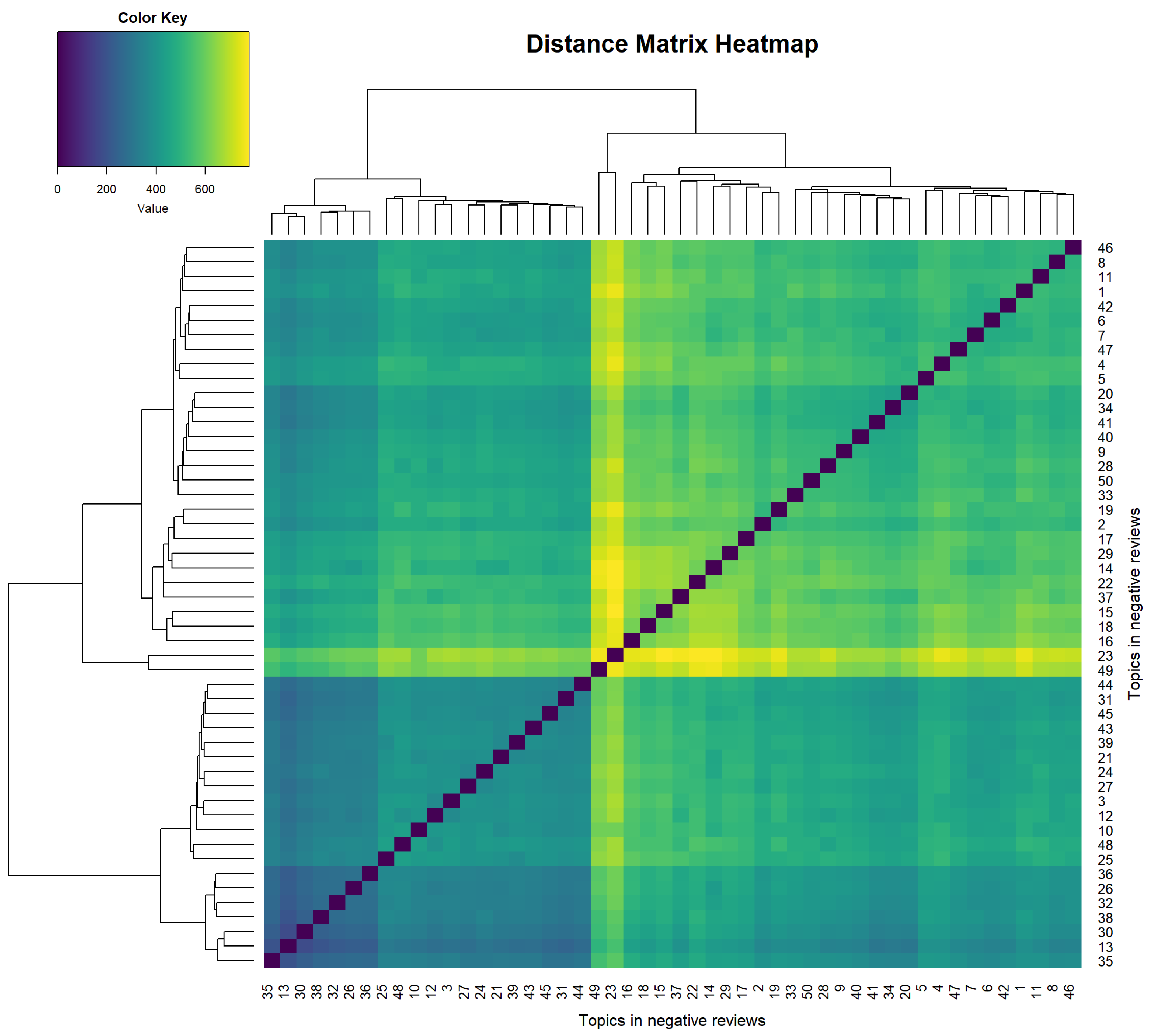

3.3. Topics in Negative Reviews

3.4. Comparison of Topics Between Review Types

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

4.2. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| DFM | Document–Feature Matrix |

| LDA | Latent Dirichlet Allocation |

| JSD | Jensen–Shannon Divergence |

| RQ | Research Question |

References

- Guzsvinecz, T. The correlation between positive reviews, playtime, design and game mechanics in souls-like role-playing video games. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 4641–4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzsvinecz, T. Sentiment analysis of souls-like role-playing video game reviews. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2023, 20, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunzelman, C. How we deal with dark souls: The aesthetic category as a method. In Hybrid Play; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Jagoda, P. On Difficulty in Video Games: Mechanics, Interpretation, Affect. Crit. Inq. 2018, 45, 199–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S. Level Up! The Guide to Great Video Game Design; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Madigan, J. Forever Questing and “Getting Gud”. In Video Games and Well-Being; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petralito, S.; Brühlmann, F.; Iten, G.; Mekler, E.D.; Opwis, K. A Good Reason to Die: How Avatar Death and High Challenges Enable Positive Experiences. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 5087–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.G.; Dalsen, J.; Kumar, V.; Berland, M.; Steinkuehler, C. Failing Up: How Failure in a Game Environment Promotes Learning Through Discourse. Think. Ski. Creat. 2018, 30, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, J.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. The Concept of Flow. In Flow and the Foundations of Positive Psychology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolfi, E. Enjoying Death Among Gamers, Viewers, and Users: A Network Visualization of Dark Souls 3’s Trends on Twitch.tv and Steam Platforms. Inf. Vis. 2018, 17, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, J.P.; Dolan, S.M.; Drake, R.S.; Wilson, G.C.; Klein, R.M.; Eskes, G.A. A Survey of Video Game Preferences in Adults: Building Better Games for Older Adults. Entertain. Comput. 2017, 21, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, D. Giantness and Excess in Dark Souls. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, Bugibba, Malta, 15–18 September 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, A.; Cardoso, P.; Carvalhais, M. Asynchronous Interactions Between Players and Game World. In Springer Series in Design and Innovation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjaltason, K.; Christophersen, S.; Togelius, J.; Nelson, M.J. Game mechanics telling stories? An experiment. In Proceedings of the Foundations of Digital Games (FDG), Pacific Grove, CA, USA, 22–25 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fusdahl, T. Vulnerability and Growth in Video Game Narratives: Approaches to Storytelling in Dark Souls 3 and Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Melnic, D.; Melnic, V. Saved games and respawn timers: The dilemma of representing death in video games. Univ. Buchar. Rev. Lit. Cult. Stud. Ser. 2018, 7, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Theodorou, A. Prepare to die: Reconceptualising death, and the role of narrative engagement in the Dark Souls series (2011–2018). In Death, Culture & Leisure: Playing Dead; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A. Lighting the bonfire. In What Is a Game?: Essays on the Nature of Videogames; Hubbel, S.G., Ed.; McFarland & Company: Jefferson, MO, USA, 2020; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bopp, J.A.; Mekler, E.D.; Opwis, K. Negative emotion, positive experience?: Emotionally moving moments in digital games. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; pp. 2996–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, G.; Kraus, M. Measuring how game feel is influenced by the player avatar’s acceleration and deceleration: Using a 2D platformer to describe players’ perception of controls in videogames. In Proceedings of the 19th International Academic Mindtrek Conference, Tampere, Finland, 22–24 September 2015; pp. 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Chen, A.; Chi, S.; Zhang, G.; Hao, A. Analysis of emotional tendency and syntactic properties of VR game reviews. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Conference on Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces Abstracts and Workshops (VRW), Virtual, 12–16 March 2022; pp. 648–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowler, C.P.R.; Iacovides, I. “Horror, guilt and shame”–Uncomfortable Experiences in Digital Games. In Proceedings of the Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, Barcelona, Spain, 22–25 October 2019; pp. 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.C.; Wu, F.G.; Feng, C.H.; Shuai, C.Y. A research on how to enhance user experience by improving arcade joystick in side-scrolling shooter games. In Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotte, A.M.; Hepting, D.H.; Roshchina, A. Left-handed control configuration for side-scrolling games. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, UK, 4–9 May 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summerville, A.; Mariño, J.R.H.; Snodgrass, S.; Ontañón, S.; Lelis, L.H.S. Understanding mario: An evaluation of design metrics for platformers. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, Cape Cod, MA, USA, 14–17 August 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H. Integrating Visual Effects into 2D Platformer Games to Enhance Play Experiences. Ph.D. Thesis, Northeastern University, Shenyang, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wehbe, R.R.; Mekler, E.D.; Schaekermann, M.; Lank, E.; Nacke, L.E. Testing incremental difficulty design in platformer games. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 6–11 May 2017; pp. 5109–5113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzsvinecz, T. The Soulsification of video games. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2025, 84, 14827–14853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedegaard, S.; Simonsen, J. Extracting usability and user experience information from online user reviews. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’13), Paris, France, 27 April–2 May 2013; pp. 2089–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.N. A study of analyzing on online game reviews using a data mining approach: STEAM community data. Int. J. Innov. Manag. Technol. 2017, 8, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Bezemer, C.P.; Zou, Y.; Hassan, A. An empirical study of game reviews on the Steam platform. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2019, 24, 170–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, D.; Maalej, W. User feedback in the AppStore: An empirical study. In Proceedings of the 2013 21st IEEE International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 15–19 July 2013; pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busurkina, I.; Karpenko, V.; Tulubenskaya, E.; Bulygin, D. Game experience evaluation. A study of game reviews on the Steam platform. In Digital Transformation and Global Society (DTGS 2020); Alexandrov, D., Boukhanovsky, A., Chugunov, A., Kabanov, Y., Koltsova, O., Musabirov, I., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1242, pp. 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, H.; Shihab, E.; Nagappan, M.; Hassan, A. What do mobile app users complain about? IEEE Softw. 2015, 32, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasa, R.; Hoon, L.; Mouzakis, K.; Noguchi, A. A preliminary analysis of mobile app user reviews. In Proceedings of the 24th Australian Computer-Human Interaction Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 26–30 November 2012; pp. 241–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Kang, J.; Park, S. What makes the difference between popular games and unpopular games? Analysis of online game reviews from Steam platform using word2vec and Bass model. ICIC Express Lett. 2017, 11, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Stefanidis, K. A data-driven approach for video game playability analysis based on players’ reviews. Information 2021, 12, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Bezemer, C.P.; Hassan, A. An empirical study of early access games on the Steam platform. Empir. Softw. Eng. 2018, 23, 771–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza Goncalves, V.; Macedo, A. Similarities and divergences in electronic game review texts. In Proceedings of the 2020 19th Brazilian Symposium on Computer Games and Digital Entertainment (SBGames), Recife, Brazil, 7–10 November 2020; pp. 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreev, G.; Saxena, D.; Verma, J. Impact of review sentiment and magnitude on customers’ recommendations for video games. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Computational Performance Evaluation (ComPE), Shillong, India, 1–3 December 2021; pp. 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wase, K.; Ramteke, P.; Bandewar, R.; Badole, N.; Kumar, B.; Bogawar, M. Sentiment Analysis of Product Review. Int. J. Innov. Eng. Sci. 2018, 3, 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hutto, C.; Gilbert, E. VADER: A parsimonious rule-based model for sentiment analysis of social media text. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1–4 June 2014; Volume 8, pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis and Opinion Mining; Synthesis Lectures on Human Language Technologies; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baowaly, M.K.H.; Tu, Y.P.; Chen, K.T. Predicting the Helpfulness of Game Reviews: A Case Study on the Steam Store. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 36, 4731–4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, L.; Kasper, P.; Koncar, P.; Gütl, C. Investigating Helpfulness of Video Game Reviews on the Steam Platform. In Proceedings of the 2018 Fifth International Conference on Social Networks Analysis, Management and Security (SNAMS), Valencia, Spain, 15–18 October 2018; pp. 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chang, V.; Horvath, G. Explaining and Predicting Helpfulness and Funniness of Online Reviews on the Steam Platform. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 2021, 29, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, C.; Feng, W.C.; Sahu, S.; Saha, D. Measurement-Based Characterization of a Collection of On-line Games. In Proceedings of the 5th ACM SIGCOMM Conference on Internet Measurement (IMC ’05), Berkeley, CA, USA, 19–21 October 2005; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.; Li, X.; Nummenmaa, T.; Zhang, Z.; Peltonen, J. Patches and Player Community Perceptions: Analysis of No Man’s Sky Steam Reviews. In Proceedings of the 2020 DiGRA International Conference. Digital Games Research Association (DiGRA), Tampere, Finland, 2–6 June 2020; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y.; Nguyen, B.H.; Yu, F.; Huynh, V.N. Esports Game Updates and Player Perception: Data Analysis of PUBG Steam Reviews. In Proceedings of the 2021 13th International Conference on Knowledge and Systems Engineering (KSE), Bangkok, Thailand, 10–12 November 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, E.; Maalej, W. How Do Users Like This Feature? A Fine Grained Sentiment Analysis of App Reviews. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE 22nd International Requirements Engineering Conference (RE), Karlskrona, Sweden, 25–29 August 2014; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D.M.; Ng, A.Y.; Jordan, M.I. Latent Dirichlet Allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 993–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Gu, S.; Xu, X. GSLDA: LDA-based Group Spamming Detection in Product Reviews. Appl. Intell. 2018, 48, 3094–3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Nguyen, B.H.; Yu, F.; Huynh, V.N. Discovering Topics of Interest on Steam Community Using an LDA Approach. In Advances in the Human Side of Service Engineering; Freund, L.E., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiran, Y.; Srivastava, S. Aspect-based Sentiment Analysis on Mobile Phone Reviews with LDA. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Machine Learning Technologies, Nanchang, China, 21–23 June 2019; pp. 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Nguyen, B.H.; Tai, D.D.; Yu, F.; Fujinami, T.; Huynh, V.N. A Topic Modeling Approach for Exploring Attraction of Dark Souls Series Reviews on Steam. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Intelligent Human Systems Integration (IHSI 2022): Integrating People and Intelligent Systems, Venice, Italy, 22–24 February 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, B. Steam Usage and Catalog Stats for 2023. 2023. Available online: https://backlinko.com/steam-users (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Valve Corporation. User Reviews–Get List (Steamworks Documentation). 2023. Available online: https://partner.steamgames.com/doc/store/getreviews (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Valve Corporation. Documentation Home Page (Steamworks Documentation). 2023. Available online: https://partner.steamgames.com/doc/home (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Guzsvinecz, T.; Szűcs, J. Game Theory and Strategic Decision-Making in the Dark Souls Games. In Game Theory; Guzsvinecz, T., Szűcs, J., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2024; Chapter 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Steam-Reviews. 2021. Available online: https://pypi.org/project/steam-reviews/ (accessed on 2 July 2023).

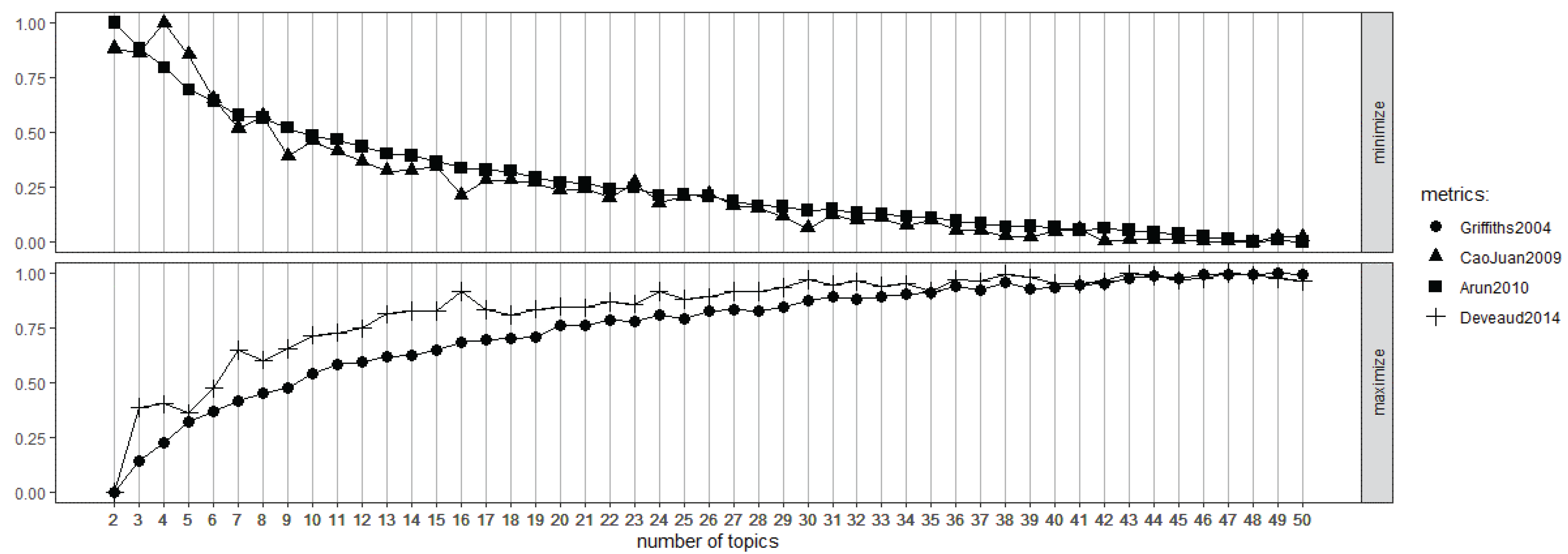

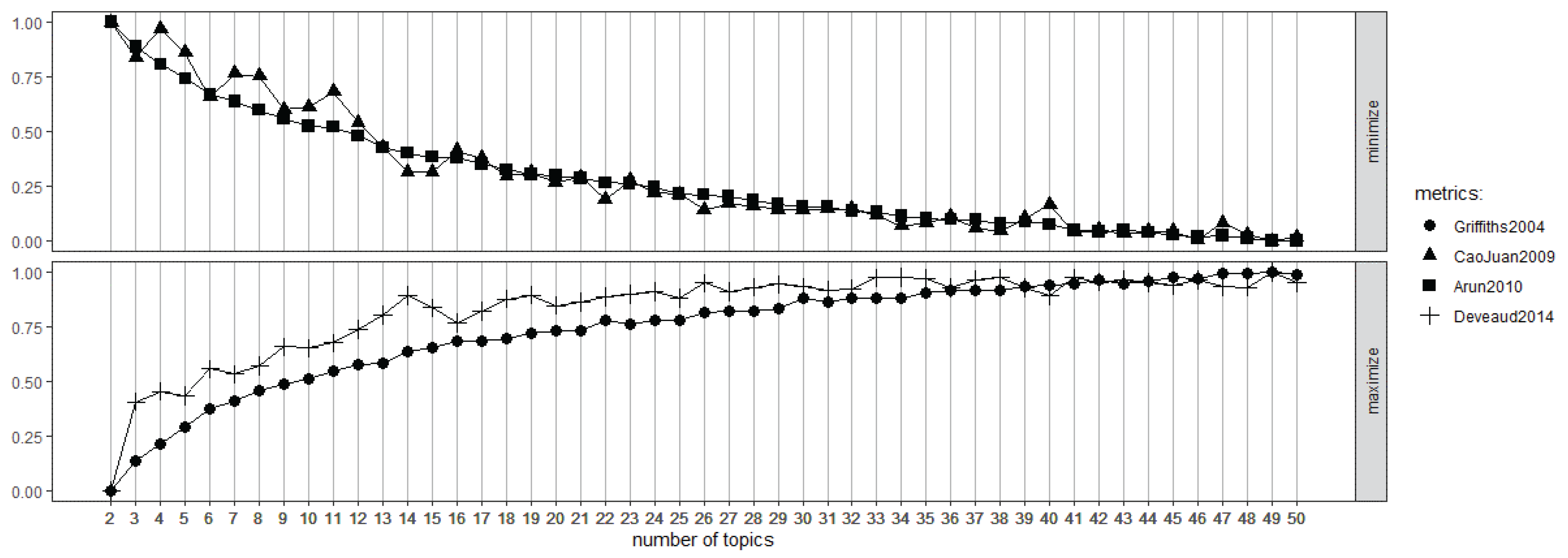

- Griffiths, T.L.; Steyvers, M. Finding scientific topics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 5228–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Xia, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S. A density-based method for adaptive LDA model selection. Neurocomputing 2009, 72, 1775–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, R.; Suresh, V.; Veni Madhavan, C.E.; Narasimha Murthy, M.N. On finding the natural number of topics with latent Dirichlet allocation: Some observations. In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deveaud, R.; SanJuan, E.; Bellot, P. Accurate and effective latent concept modeling for ad hoc information retrieval. Doc. Numér. 2014, 17, 61–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

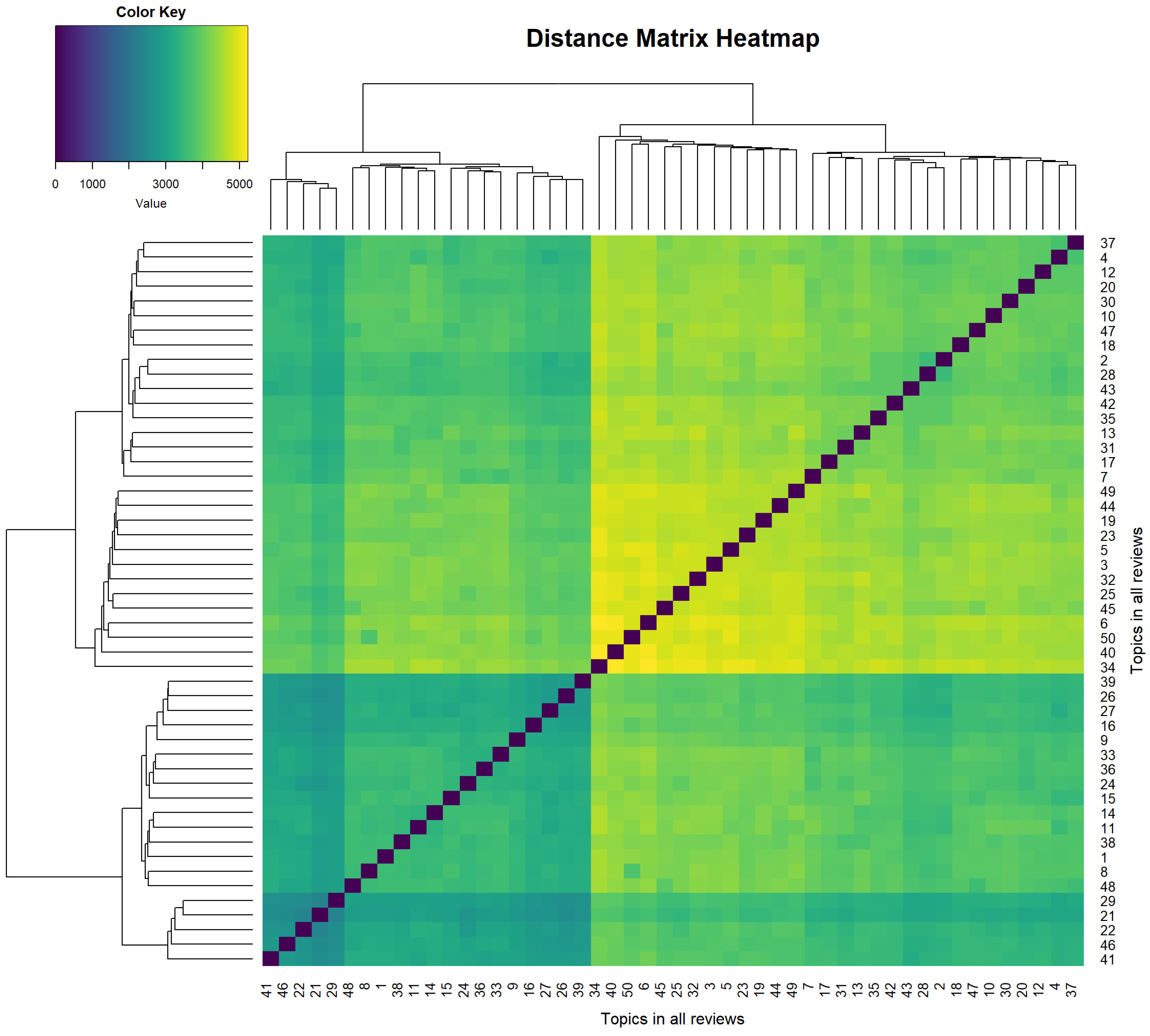

- Lin, J. Divergence measures based on the Shannon entropy. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1991, 37, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, H.; Wickham, H.; Kafadar, K. Letter-value plots: Boxplots for large data. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2017, 26, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Min | Max | Median | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative review | 0.00 | 1885.00 | 21.00 | 75.88 | 152.53 |

| Positive review | 0.00 | 2289.00 | 7.00 | 35.88 | 97.63 |

| Estimate | Standard Error | t Value | Pr(>|t|) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 110.35 | 0.61 | 179.69 | <0.001 |

| Positive review | −60.12 | 0.64 | −92.96 | <0.001 |

| Group | Topics |

|---|---|

| 1 | 4, 11, 13, 14, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32, 37, 41, 43, 44, 46 |

| 2 | 1, 2, 6, 8, 9, 15, 16, 33, 36, 38, 39, 42, 45 |

| 3 | 3, 5, 10, 12, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 30, 31, 34, 35, 40, 49, 50 |

| 4 | 47, 48 |

| 5 | 7, 18 |

| Group | Topics |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 8, 9, 11, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23, 26, 27, 30, 31, 32, 35, 36, 39, 41, 42, 45, 46 |

| 2 | 5, 6, 10, 13, 44, 48 |

| 3 | 2, 3, 7, 12, 14, 15, 16, 19, 24, 28, 29, 38, 40, 43, 47, 49, 50 |

| 4 | 17, 25, 37 |

| 5 | 4, 33 |

| Group | Topics |

|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 3, 4, 7, 19, 20, 31, 32, 35, 36, 37, 39, 44 |

| 2 | 6, 10, 11, 12, 14, 21, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 42, 43, 45, 48, 49 |

| 3 | 2, 5, 8, 9, 17, 22, 29, 33, 34, 38, 40, 41, 46, 47, 50 |

| 4 | 15, 16, 18, 28 |

| 5 | 13, 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guzsvinecz, T. Topic Modeling of Positive and Negative Reviews of Soulslike Video Games. Computers 2025, 14, 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14080339

Guzsvinecz T. Topic Modeling of Positive and Negative Reviews of Soulslike Video Games. Computers. 2025; 14(8):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14080339

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuzsvinecz, Tibor. 2025. "Topic Modeling of Positive and Negative Reviews of Soulslike Video Games" Computers 14, no. 8: 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14080339

APA StyleGuzsvinecz, T. (2025). Topic Modeling of Positive and Negative Reviews of Soulslike Video Games. Computers, 14(8), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14080339