Three-Dimensional Surgical Planning in Mandibular Cancer: A Decade of Clinical Experience and Outcomes

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

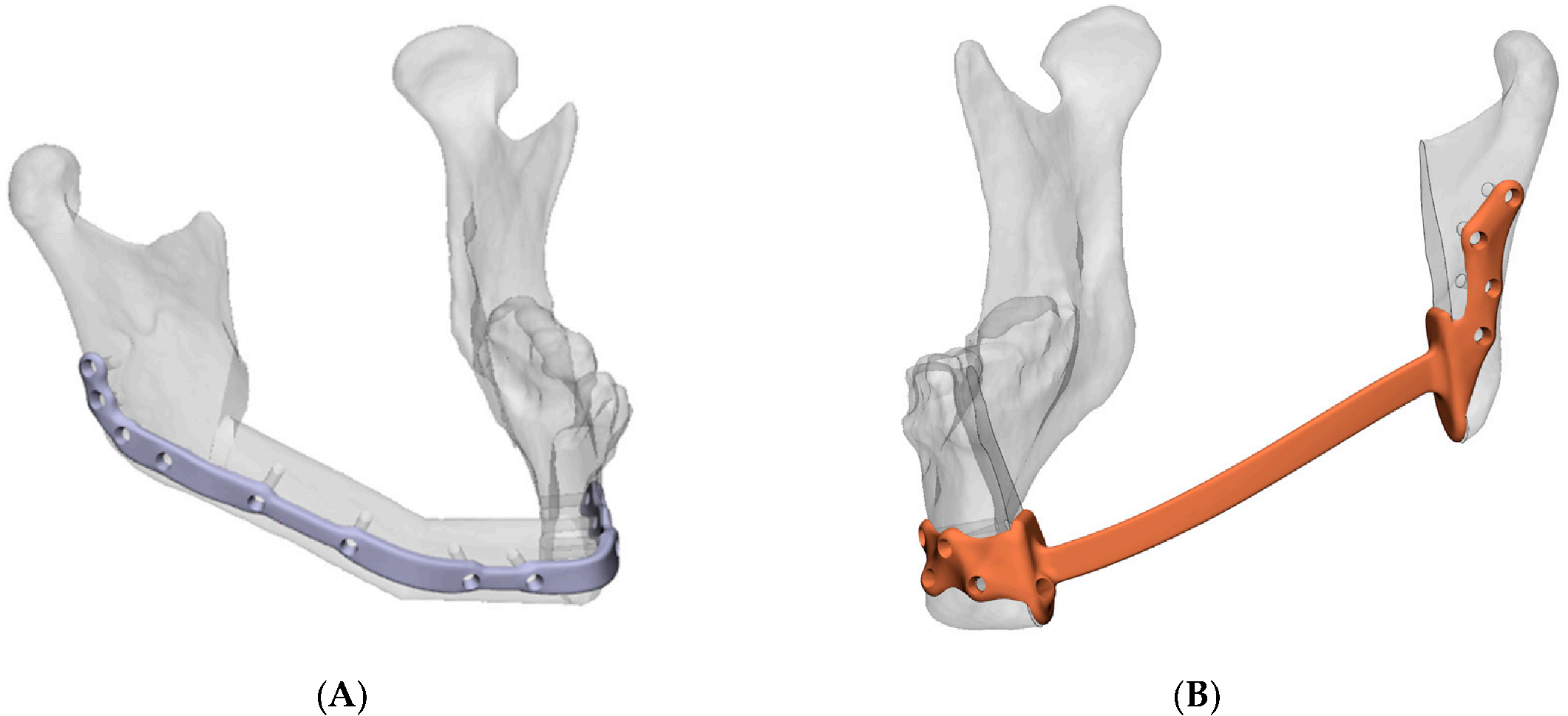

2.1. Clinical Workflow

2.2. Study Design and Population

2.3. Data Acquisition

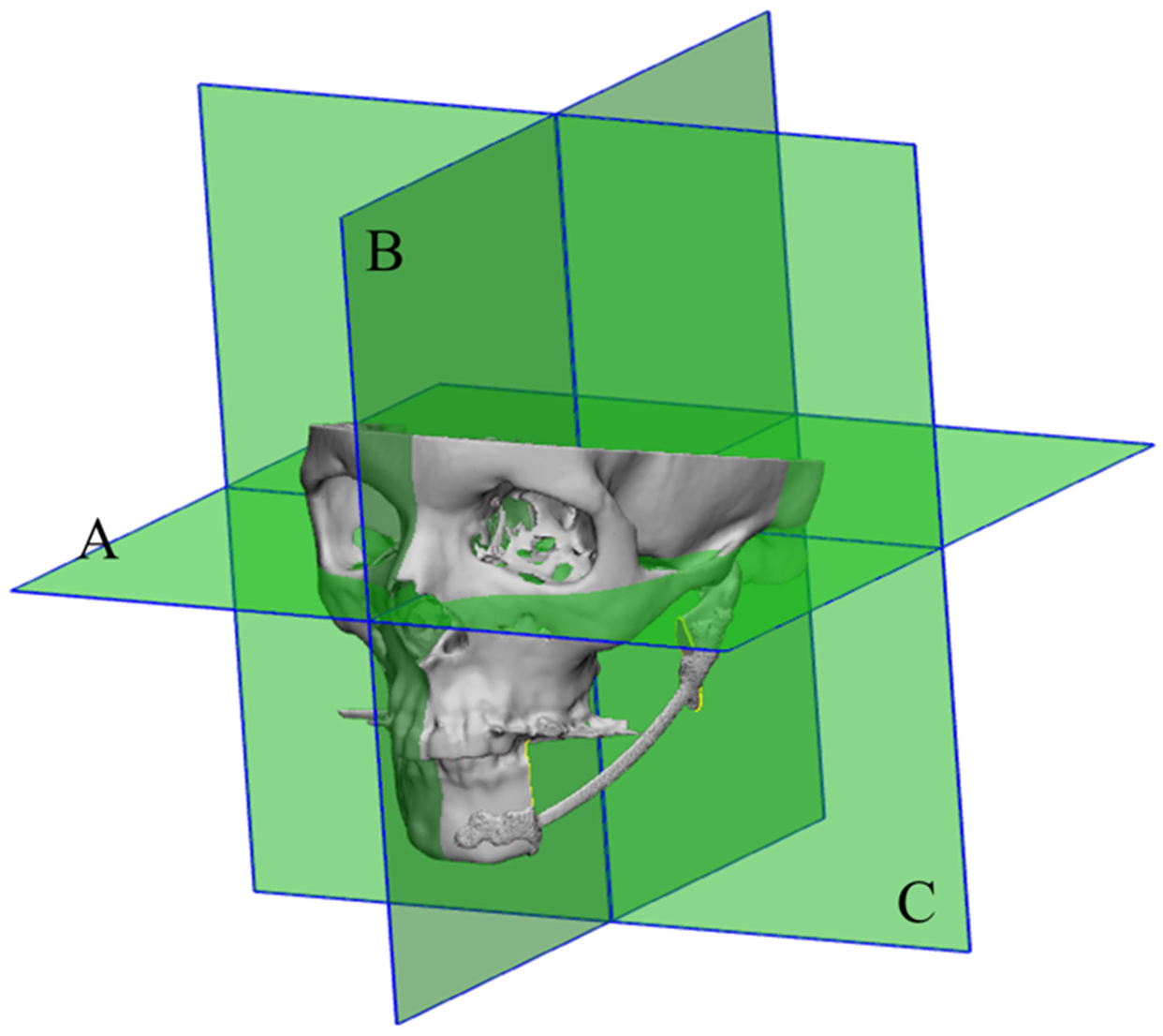

2.4. Orientation

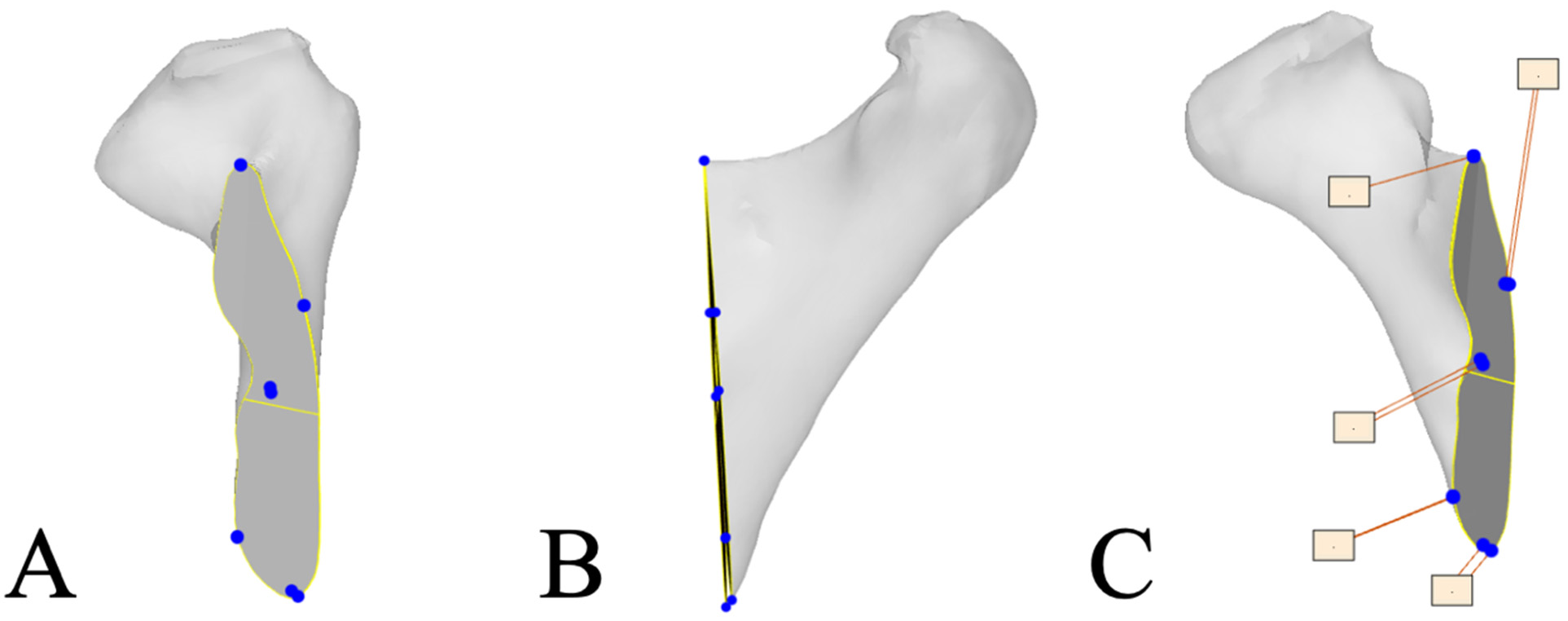

2.5. Resection Plane Accuracy Analysis

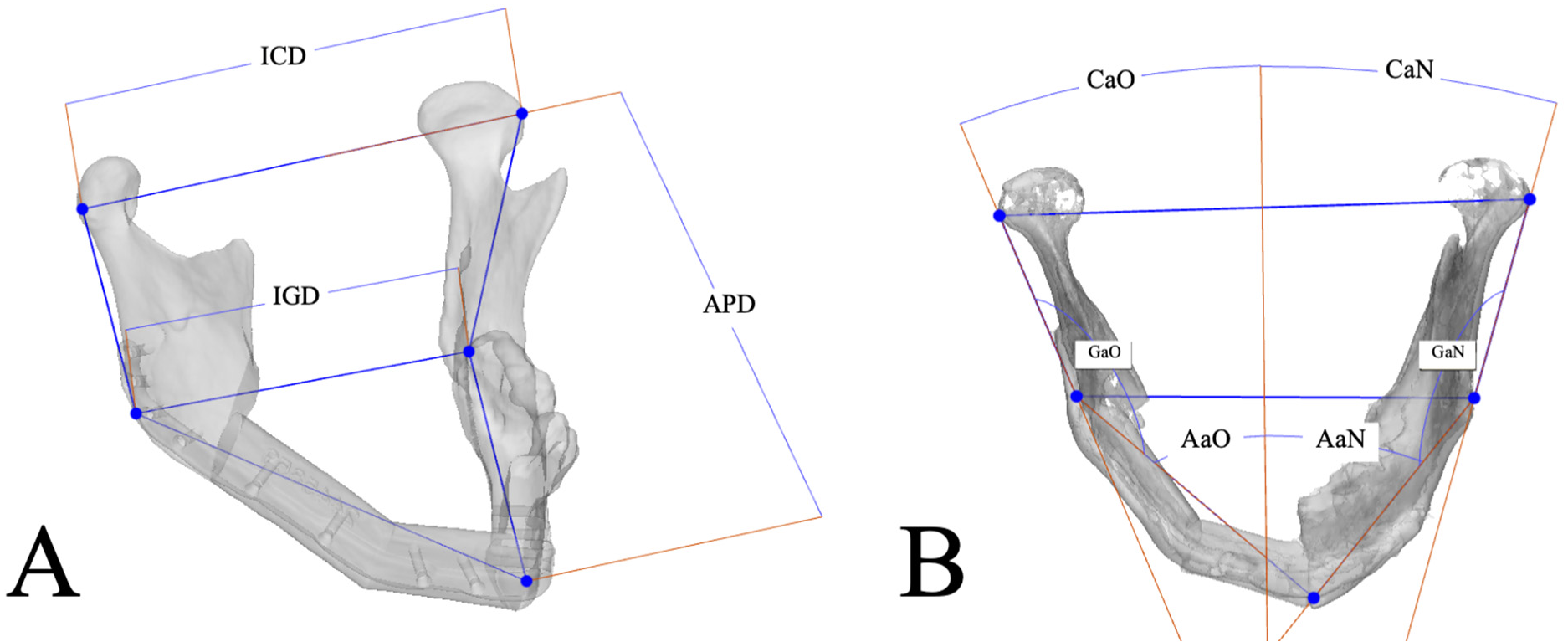

2.6. Mandibular Reconstruction Accuracy Analysis

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Clinical Outcomes

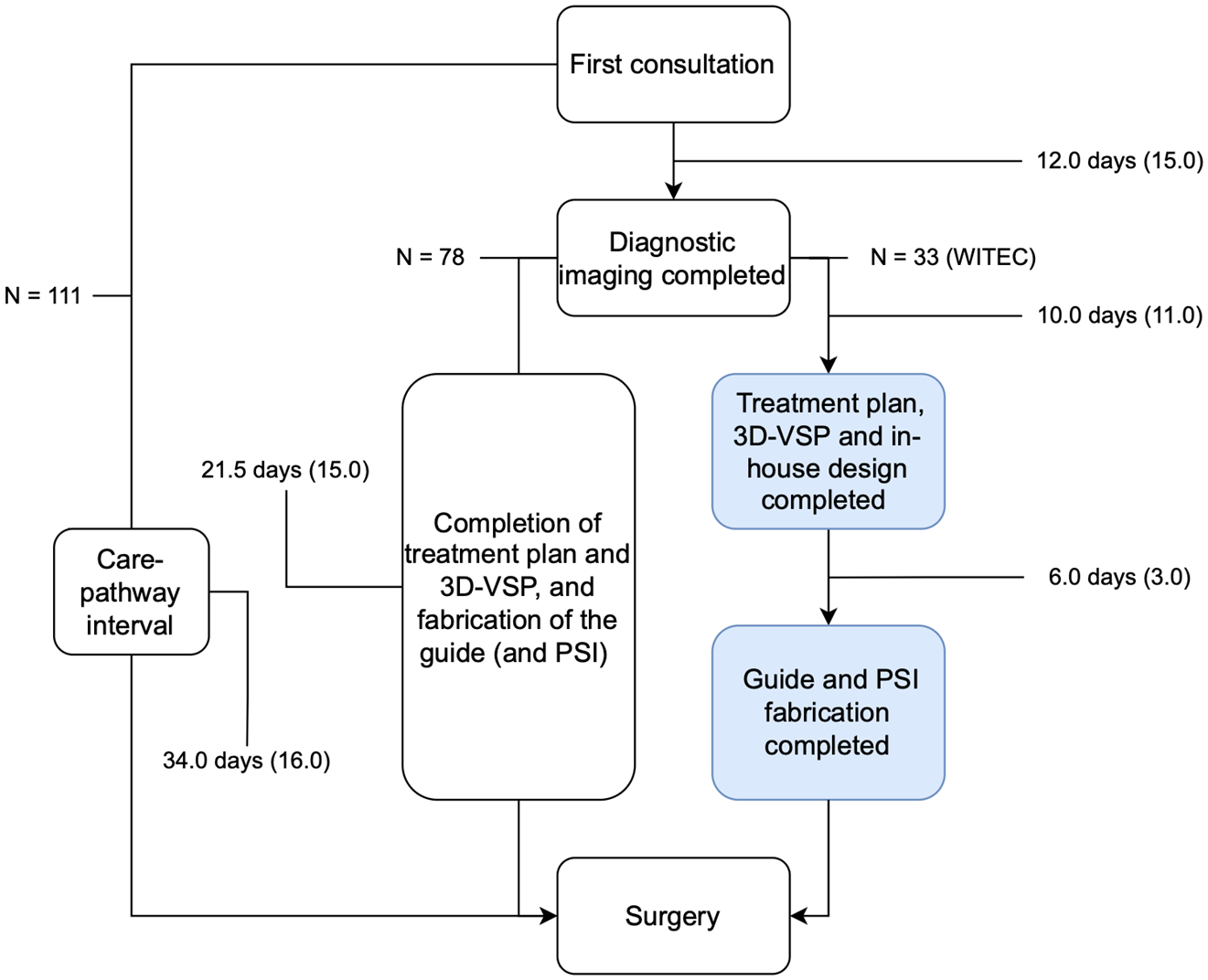

3.3. Treatment Timelines

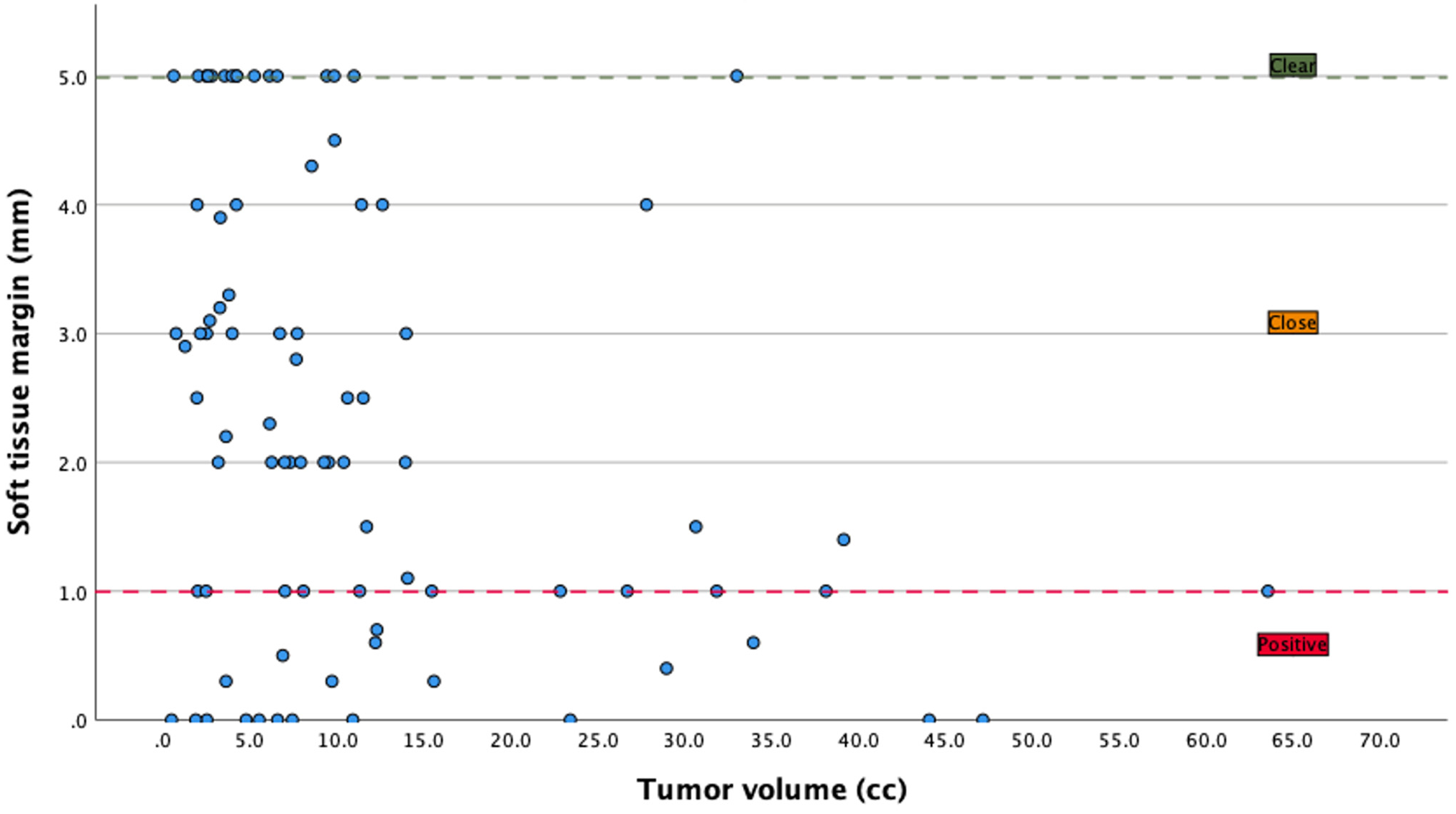

3.4. Margins

3.5. Complication Rates

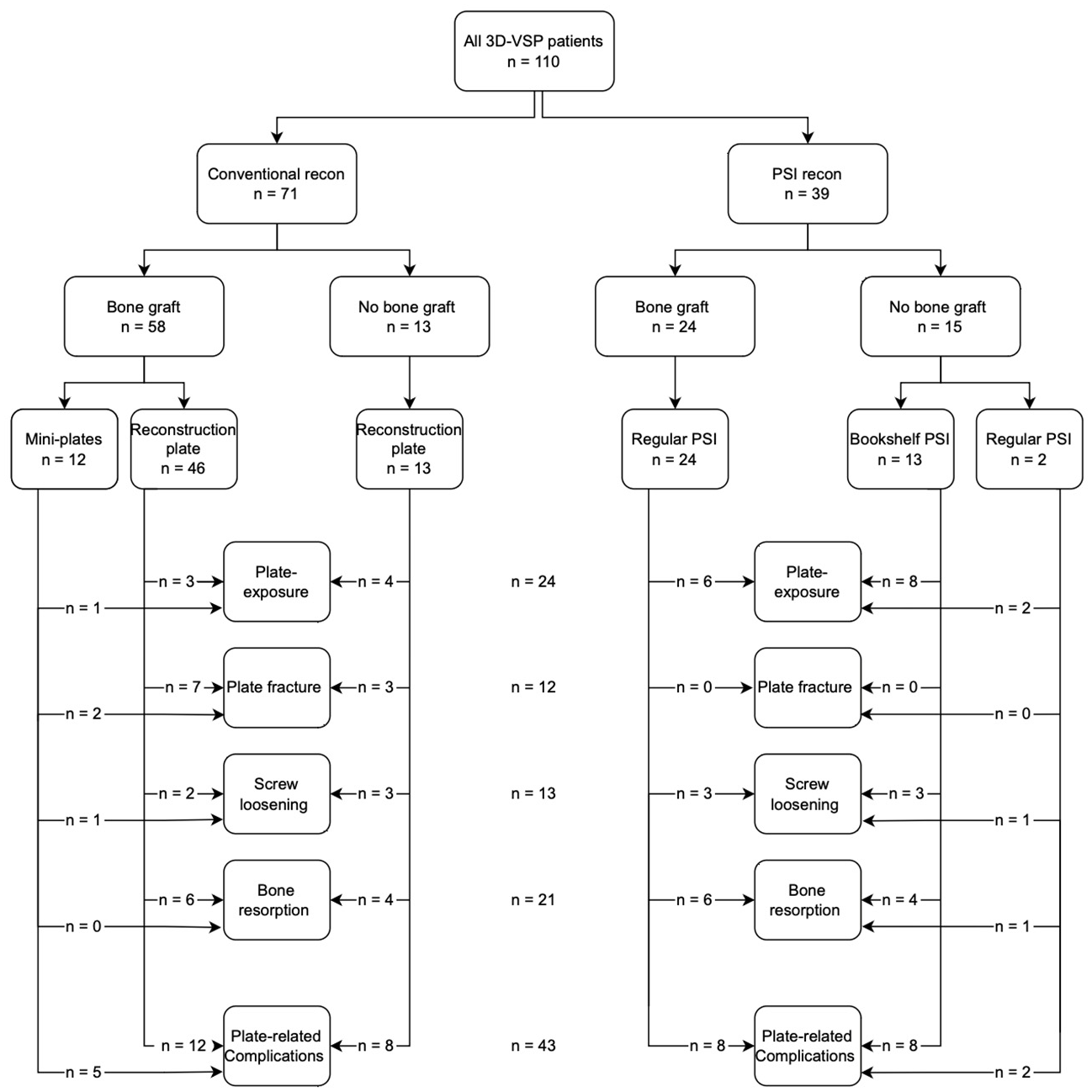

3.5.1. Plate-Related Complications

3.5.2. Plate Exposure

3.5.3. Plate Fracture

3.5.4. Bone Resorption

3.6. Plate Removal

3.7. Guides Not Used

3.8. Flap Failure

3.9. Local Recurrence

3.10. Osteotomy Plane Accuracy

3.11. Mandibular Reconstruction Accuracy

3.12. Intra-Observer Variation

3.13. Inter-Observer Variation

4. Discussion

4.1. Adherence to Dutch Guidelines

4.2. Complication Rate

4.3. Accuracy of Resection Plane and Mandibular Reconstruction

4.4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| CPI | Care pathway interval |

| 3D-VSP | Three-dimensional virtual surgical planning |

| UMCG | University Medical Center Groningen |

| PSI | Patient-specific implant |

| DICOM | Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine |

| ICD | Intercondylar distance |

| IGD | Intergonial distance |

| APD | Anteroposterior distance |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| MAD | Mean absolute difference |

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

References

- Kraeima, J.; Dorgelo, B.; Gulbitti, H.A.; Steenbakkers, R.; Schepman, K.P.; Roodenburg, J.L.N.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; Schepers, R.H.; Witjes, M.J.H. Multi-Modality 3d Mandibular Resection Planning in Head and Neck Cancer Using Ct and Mri Data Fusion: A Clinical Series. Oral Oncol. 2018, 81, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoonbeek, R.C.; Zwertbroek, J.; Plaat, B.E.C.; Takes, R.P.; Ridge, J.A.; Strojan, P.; Ferlito, A.; van Dijk, B.A.C.; Halmos, G.B. Determinants of Delay and Association with Outcome in Head and Neck Cancer: A Systematic Review. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 47, 1816–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Database, Dutch Online Guidelines. Head and Neck Tumors: Brief Description. Available online: https://richtlijnendatabase.nl/richtlijn/hoofd-halstumoren_sept_2023/startpagina_-_hoofd-halstumoren_2023.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Villemure-Poliquin, N.; Fu, R.; Gaebe, K.; Kwon, J.; Cohen, M.; Ruel, M.; Ayoo, K.; Bailey, A.; Galapin, M.; Hallet, J.; et al. Delayed Diagnosis to Treatment Interval (Dti) in Head & Neck Cancers—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oral Oncol. 2025, 160, 107106. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, K.; Moratin, J.; Horn, D.; Pilz, M.; Ristow, O.; Hoffmann, J.; Freier, K.; Engel, M.; Freudlsperger, C. Treatment Delay in Early-Stage Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Its Relation to Survival. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2021, 49, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, R.; Ward, M.C.; Yang, K.; Adelstein, D.J.; Koyfman, S.A.; Prendes, B.L.; Burkey, B.B. Increased Pathologic Upstaging with Rising Time to Treatment Initiation for Head and Neck Cancer: A Mechanism for Increased Mortality. Cancer 2018, 124, 1400–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witjes, M.J.H.; Schepers, R.H.; Kraeima, J. Impact of 3d Virtual Planning on Reconstruction of Mandibular and Maxillary Surgical Defects in Head and Neck Oncology. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 26, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merema, B.B.J.; Kraeima, J.; de Visscher, S.; van Minnen, B.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; Schepman, K.P.; Witjes, M.J.H. Novel Finite Element-Based Plate Design for Bridging Mandibular Defects: Reducing Mechanical Failure. Oral Dis. 2020, 26, 1265–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.F.; Choi, W.S.; Wong, M.C.; Powcharoen, W.; Zhu, W.Y.; Tsoi, J.K.; Chow, M.; Kwok, K.W.; Su, Y.X. Three-Dimensionally Printed Patient-Specific Surgical Plates Increase Accuracy of Oncologic Head and Neck Reconstruction Versus Conventional Surgical Plates: A Comparative Study. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreutzer, K.; Lampert, P.; Doll, C.; Voss, J.O.; Koerdt, S.; Heiland, M.; Steffen, C.; Rendenbach, C. Patient-Specific 3d-Printed Mini-Versus Reconstruction Plates for Free Flap Fixation at the Mandible: Retrospective Study of Clinical Outcomes and Complication Rates. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2023, 51, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, A.; Alamillos, F.; Heredero, S.; Redondo-Camacho, A.; Guler, I.; Sanjuan, A. Fibula Free Flap in Maxillomandibular Reconstruction. Factors Related to Osteosynthesis Plates’ Complications. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2020, 48, 994–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskander, A.; Kang, S.; Tweel, B.; Sitapara, J.; Old, M.; Ozer, E.; Agrawal, A.; Carrau, R.; Rocco, J.W.; Teknos, T.N. Predictors of Complications in Patients Receiving Head and Neck Free Flap Reconstructive Procedures. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2018, 158, 839–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendenbach, C.; Steffen, C.; Hanken, H.; Schluermann, K.; Henningsen, A.; Beck-Broichsitter, B.; Kreutzer, K.; Heiland, M.; Precht, C. Complication Rates and Clinical Outcomes of Osseous Free Flaps: A Retrospective Comparison of Cad/Cam Versus Conventional Fixation in 128 Patients. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 1156–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gemert, J.T.M.; Abbink, J.H.; van Es, R.J.J.; Rosenberg, A.; Koole, R.; Van Cann, E.M. Early and Late Complications in the Reconstructed Mandible with Free Fibula Flaps. J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 117, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.Y.; Lai, Y.S.; Lin, C.Y.; Wang, J.D.; Pan, S.C.; Shieh, S.J.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, Y.C. Plate-Related Complication and Health-Related Quality of Life after Mandibular Reconstruction by Fibula Flap with Reconstruction Plate or Miniplate Versus Anterolateral Thigh Flap with Reconstruction Plate. Microsurgery 2023, 43, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J.C.; Chan, H.H.L.; Yao, C.; Ziai, H.; Dixon, P.R.; Chepeha, D.B.; Goldstein, D.P.; de Almeida, J.R.; Gilbert, R.W.; Irish, J.C. Association of Plate Contouring with Hardware Complications Following Mandibular Reconstruction. Laryngoscope 2022, 132, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walia, A.; Mendoza, J.; Bollig, C.A.; Craig, E.J.; Jackson, R.S.; Rich, J.T.; Puram, S.V.; Massa, S.T.; Pipkorn, P. A Comprehensive Analysis of Complications of Free Flaps for Oromandibular Reconstruction. Laryngoscope 2021, 131, 1997–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heins, J.I.; Merema, B.B.J.; Kraeima, J.; Witjes, M.J.H.; Krushynska, A.O. Mandibular Implants: A Metamaterial-Based Approach to Reducing Stress Shielding. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 14, e2500405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merema, B.B.J.; Spijkervet, F.K.L.; Kraeima, J.; Witjes, M.J.H. A Non-Metallic Peek Topology Optimization Reconstruction Implant for Large Mandibular Continuity Defects, Validated Using the Mandybilator Apparatus. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.S.; Barry, C.; Ho, M.; Shaw, R. A New Classification for Mandibular Defects after Oncological Resection. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, e23–e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittayapat, P.; Jacobs, R.; Bornstein, M.M.; Odri, G.A.; Lambrichts, I.; Willems, G.; Politis, C.; Olszewski, R. Three-Dimensional Frankfort Horizontal Plane for 3d Cephalometry: A Comparative Assessment of Conventional Versus Novel Landmarks and Horizontal Planes. Eur. J. Orthod. 2018, 40, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.N.; Bloom, J.M.; Kulbersh, R. A Simple and Accurate Craniofacial Midsagittal Plane Definition. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 152, 355–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besl, P.J.; McKay, N.D. A Method for Registration of 3-D Shapes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1992, 14, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, N.; Llamas, J.M.; Cibrian, R.; Gandia, J.L.; Paredes, V. A Study on the Reproducibility of Cephalometric Landmarks When Undertaking a Three-Dimensional (3d) Cephalometric Analysis. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2012, 17, e678–e688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrell, P.E.; Nyquist, H.; Isberg, A. Validity of Identification of Gonion and Antegonion in Frontal Cephalograms. Angle Orthod. 2000, 70, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schoonbeek, R.C.; de Vries, J.; Bras, L.; Sidorenkov, G.; Plaat, B.E.C.; Witjes, M.J.H.; van der Laan, B.; van den Hoek, J.G.M.; van Dijk, B.A.C.; Langendijk, J.A.; et al. The Effect of Treatment Delay on Quality of Life and Overall Survival in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2022, 31, e13589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaff, L.H.; Platek, A.J.; Iovoli, A.J.; Wooten, K.E.; Arshad, H.; Gupta, V.; McSpadden, R.P.; Kuriakose, M.A.; Hicks, W.L., Jr.; Platek, M.E.; et al. The Effect of Time between Diagnosis and Initiation of Treatment on Outcomes in Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2019, 96, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barry, C.P.; MacDhabheid, C.; Tobin, K.; Stassen, L.F.; Lennon, P.; Toner, M.; O’Regan, E.; Clark, J.R. ‘Out of House’ Virtual Surgical Planning for Mandible Reconstruction after Cancer Resection: Is It Oncologically Safe? Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knitschke, M.; Backer, C.; Schmermund, D.; Bottger, S.; Streckbein, P.; Howaldt, H.P.; Attia, S. Impact of Planning Method (Conventional Versus Virtual) on Time to Therapy Initiation and Resection Margins: A Retrospective Analysis of 104 Immediate Jaw Reconstructions. Cancers 2021, 13, 3013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villarme, A.; Pace-Loscos, T.; Schiappa, R.; Poissonnet, G.; Dassonville, O.; Chamorey, E.; Bozec, A.; Culie, D. Impact of Virtual Surgical Planning and Three-Dimensional Modeling on Time to Surgery in Mandibular Reconstruction by Free Fibula Flap. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 50, 108008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 13485:2016; Medical Devices—Quality Management Systems—Requirements for Regulatory Purposes. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/59752.html (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Barroso, E.M.; Aaboubout, Y.; van der Sar, L.C.; Mast, H.; Sewnaik, A.; Hardillo, J.A.; Hove, I.T.; Soares, M.R.N.; Ottevanger, L.; Schut, T.C.B.; et al. Performance of Intraoperative Assessment of Resection Margins in Oral Cancer Surgery: A Review of Literature. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 628297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smits, R.W.H.; Hove, I.T.; Dronkers, E.A.C.; Schut, T.C.B.; Mast, H.; de Jong, R.J.B.; Wolvius, E.B.; Puppels, G.J.; Koljenovic, S. Evaluation of Bone Resection Margins of Segmental Mandibulectomy for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 47, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Lin, J.; Men, Y.; Yang, W.; Mi, F.; Li, L. Does Medullary Versus Cortical Invasion of the Mandible Affect Prognosis in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waech, T.; Pazahr, S.; Guarda, V.; Rupp, N.J.; Broglie, M.A.; Morand, G.B. Measurement Variations of Mri and Ct in the Assessment of Tumor Depth of Invasion in Oral Cancer: A Retrospective Study. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 135, 109480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heins, J.I.; Merema, B.B.J.; Schepman, K.; Lamers, M.J.; Vister, J.; van der Vegt, B.; Doff, J.; Kraeima, J.; Witjes, M.J.H. Accuracy of Mri-Based Tumor Delineation of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Mandibular Bone Invasion Using Histopathological Validation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2026; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Gowrishankar, S.; Van Keulen, S.; Mattingly, A.; Tanaka, H.; Topf, M.; Mannion, K.; Langerman, A.; Rohde, S.; Sinard, R.; Choe, J.; et al. Fluorescence-Guided Surgery for Assessing Margins in Head and Neck Cancer: A Review. JAMA Surg. 2025, 160, 1018–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debacker, J.M.; Schelfhout, V.; Brochez, L.; Creytens, D.; D’Asseler, Y.; Deron, P.; Keereman, V.; Van de Vijver, K.; Vanhove, C.; Huvenne, W. High-Resolution (18)F-Fdg Pet/Ct for Assessing Three-Dimensional Intraoperative Margins Status in Malignancies of the Head and Neck, a Proof-of-Concept. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeller, A.N.; Neuhaus, M.T.; Weissbach, L.V.M.; Rana, M.; Dhawan, A.; Eckstein, F.M.; Gellrich, N.C.; Zimmerer, R.M. Patient-Specific Mandibular Reconstruction Plates Increase Accuracy and Long-Term Stability in Immediate Alloplastic Reconstruction of Segmental Mandibular Defects. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2020, 19, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Su, Y.; Pu, J.; Zhang, C.; Yang, W. Cutting-Edge Patient-Specific Surgical Plates for Computer-Assisted Mandibular Reconstruction: The Art of Matching Structures and Holes in Precise Surgery. Front. Surg. 2023, 10, 1132669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, P.L.; Nelson, J.A.; Rosen, E.B.; Allen, R.J., Jr.; Disa, J.J.; Matros, E. Virtual Surgical Planning for Oncologic Mandibular and Maxillary Reconstruction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2021, 9, e3672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goormans, F.; Sun, Y.; Bila, M.; Schoenaers, J.; Geusens, J.; Lubbers, H.T.; Coucke, W.; Politis, C. Accuracy of Computer-Assisted Mandibular Reconstructions with Free Fibula Flap: Results of a Single-Center Series. Oral Oncol. 2019, 97, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roser, S.M.; Ramachandra, S.; Blair, H.; Grist, W.; Carlson, G.W.; Christensen, A.M.; Weimer, K.A.; Steed, M.B. The Accuracy of Virtual Surgical Planning in Free Fibula Mandibular Reconstruction: Comparison of Planned and Final Results. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 2824–2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annino, D.J., Jr.; Sethi, R.K.; Hansen, E.E.; Horne, S.; Dey, T.; Rettig, E.M.; Uppaluri, R.; Kass, J.I.; Goguen, L.A. Virtual Planning and 3d-Printed Guides for Mandibular Reconstruction: Factors Impacting Accuracy. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2022, 7, 1798–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pucci, R.; Weyh, A.; Smotherman, C.; Valentini, V.; Bunnell, A.; Fernandes, R. Accuracy of Virtual Planned Surgery Versus Conventional Free-Hand Surgery for Reconstruction of the Mandible with Osteocutaneous Free Flaps. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 49, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Mahallawy, Y.; Dessoky, N.Y.; Abdelrahman, H.H.; Al-Mahalawy, H. Evaluation of the Resection Plane Three-Dimensional Positional Accuracy Using a Resection Guide Directional Guidance Slot; a Randomized Clinical Trial. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramella, V.; Franchi, A.; Bottosso, S.; Tirelli, G.; Novati, F.C.; Arnez, Z.M. Triple-Cut Computer-Aided Design-Computer-Aided Modeling: More Oncologic Safety Added to Precise Mandible Modeling. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 1567.e1–1567.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| All (111) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (%) | Male | 51 (45.9%) | ||||

| Female | 60 (54.1%) | |||||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 66.7 (±13.9) | ||||

| Risk Factors | Smoking | 69 (62.2%) | ||||

| Alcohol | 55 (49.5%) | |||||

| Status (%) | Alive | 54 (48.6%) | ||||

| Dead | 57 (51.4%) | |||||

| Follow-up (months) | Mean (SD) | 59.8 (±144.8) | ||||

| T (%) | Clinical | Pathological | Cohen’s K 0.272 | Weighted-K 0.367 | p-value * 0.338 | |

| T1 | 8 (7.2%) | 8 (7.2%) | ||||

| T2 | 19 (17.2%) | 25 (22.5%) | ||||

| T3 | 5 (4.5%) | 2 (2.4%) | ||||

| T4 | 79 (71.2%) | 76 (68.5%) | ||||

| N (%) | N0 | 55 (49.5%) | 78 (70.3%) | 0.217 | 0.281 | <0.001 |

| N1 | 18 (16.2%) | 12 (10.8%) | ||||

| N2 | 36 (32.4%) | 16 (14.4%) | ||||

| N3 | 2 (1.8%) | 5 (4.5%) | ||||

| M (%) | M0 | 111 (100%) | 111 (100%) | |||

| M1 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Location | Left | 41 (36.9%) | ||||

| Right | 46 (41.4%) | |||||

| Front | 24 (21.7%) | |||||

| Brown Classification | I | 38 (34.2%) | ||||

| II | 49 (44.1%) | |||||

| III | 23 (20.7%) | |||||

| IV | 1 (0.9%) | |||||

| Used flap | Fibula | 81 (73.0%) | ||||

| Pectoralis | 25 (22.5%) | |||||

| major | ||||||

| Other | 5 (4.5%) | |||||

| Number of segments | 0 | 29 (26.1%) | ||||

| 1 | 49 (44.1%) | |||||

| 2 | 26 (23.4%) | |||||

| 3 | 7 (6.3%) | |||||

| Used plate | Conventional | 59 (53.2%) | ||||

| Miniplate | 12 (10.8%) | |||||

| PSI | 26 (23.4%) | |||||

| Bookshelf-PSI | 13 (11.7%) | |||||

| Adjuvant therapy | Radiotherapy | 71 (64.0%) | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 19 (17.1%) |

| All (111) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone margin | |||||

| Yes | 104 (93.7%) | ||||

| No | 7 (6.3%) | ||||

| Soft tissue margin | |||||

| Positive | 31 (27.9%) | ||||

| Close | 52 (46.8%) | ||||

| Clear | 28 (25.2%) | ||||

| Tumor volume in cc (mean (SD)) | 11.2 (±12.0) | ||||

| Tumor diameter in mm (mean (SD)) | 28.6 (±14.6) | ||||

| Tumor depth of invasion (mean (SD)) | 13.0 (±9.9) | ||||

| Pathological | Radiological | Cohen’s K | Weighted-K | p-value * | |

| Bone invasion Cortex Medulla Perineural invasion Lymphovascular invastion | 75 (67.6%) 41 (51.9%) 34 (48.1%) 39 (35.1%) 18 (16.2%) | 77 (69.4%) 23 (27.0%) 54 (73.0%) | 0.267 | 0.338 | 0.013 |

| Measurements | All Planes (155) | Posterior Plane (78) | Anterior Plane (77) | Plane Shift (155) * | p-Value ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center of gravity (mm) | 1.63 (±1.42) | 1.32 (±1.15) | 1.94 (±1.59) | 73 (47.1%) | 0.011 |

| Buccal (mm) | 1.77 (±1.77) | 1.23 (±1.32) | 2.32 (±2.00) | 73 (47.1%) | <0.001 |

| Lingual (mm) | 1.64 (±1.47) | 1.42 (±1.29) | 1.86 (±1.61) | 79 (51.0%) | 0.030 |

| Superior (mm) | 1.70 (±1.39) | 1.54 (±1.25) | 1.87 (±1.51) | 80 (51.6%) | 0.199 |

| Inferior (mm) | 1.98 (±1.90) | 1.71 (±1.77) | 2.26 (±2.00) | 74 (47.7%) | 0.047 |

| Angle (°) | 8.54 (±5.66) | 8.80 (±5.62) | 8.27 (±5.72) | 0.533 |

| Measurements | All Patients (82) | Conventional (41) | PSI (22) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercondylar distance (mm) | 1.86 (±1.54) | 1.97 (±1.83) | 1.61 (±1.17) | 0.757 |

| Intergonial distance (mm) | 2.57 (±1.99) | 2.78 (±2.07) | 1.65 (±1.07) | 0.048 |

| Anterio-posterior distance (mm) | 2.21 (±1.71) | 1.98 (±1.29) | 2.44 (±2.46) | 0.914 |

| Operated side | ||||

| Gonial Angle (°) | 3.50 (±2.63) | 3.00 (±1.54) | 3.51 (±2.76) | 0.419 |

| Axial Angle (°) | 3.09 (±3.05) | 2.75 (±2.11) | 3.96 (±3.27) | 0.231 |

| Coronal Angle (°) | 2.83 (±2.14) | 3.35 (±2.25) | 1.89 (±1.41) | 0.008 |

| Non-Operated side | ||||

| Gonial Angle (°) | 2.00 (±1.61) | 1.57 (±1.43) | 2.51 (±1.89) | 0.040 |

| Axial Angle (°) | 2.98 (±3.12) | 3.28 (±3.21) | 3.39 (±3.27) | 0.719 |

| Coronal Angle (°) | 2.51 (±2.04) | 2.68 (±2.12) | 2.20 (±1.72) | 0.419 |

| N | Plate-Related | Plate Exposure | Plate Fracture | Screw Loosening | Bone Resorption | Plate Removal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | 110 | 39.1% | 21.8% | 10.9% | 11.8% | 19.1% | 16.4% |

| Kreutzer [10] | 83 | 47.0% | 20.5% | 0.0% | 2.4% | 12.5% | 32.5% |

| Dean [11] | 111 | 26.1% | 14.4% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 2.7% | 18.9% |

| Eskander [12] | 515 | - | 15.0% | - | - | - | - |

| Rendenbach [13] | 128 | 60.2% | 21.9% | - | 7.0% | - | 31.3% |

| Van Gemert [14] | 79 | - | 11.3% | 5.1% | - | 5.1% | 18.9% |

| Chang [15] | 219 | 25.4% | 15.6% | 13.7% | - | - | - |

| Davies [16] | 94 | - | 30.0% | - | 12.8% | - | - |

| Walia [17] | 266 | 30.0% | 26.7% | 2.6% | - | 9.0% | 18.0% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yang, L.H.; Merema, B.B.J.; Kraeima, J.; Boeve, K.; Schepman, K.-P.; Huijing, M.A.; van der Beek, E.S.J.; Stenekes, M.W.; Vister, J.; de Visscher, S.A.H.J.; et al. Three-Dimensional Surgical Planning in Mandibular Cancer: A Decade of Clinical Experience and Outcomes. Cancers 2026, 18, 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020271

Yang LH, Merema BBJ, Kraeima J, Boeve K, Schepman K-P, Huijing MA, van der Beek ESJ, Stenekes MW, Vister J, de Visscher SAHJ, et al. Three-Dimensional Surgical Planning in Mandibular Cancer: A Decade of Clinical Experience and Outcomes. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):271. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020271

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Li H., Bram B. J. Merema, Joep Kraeima, Koos Boeve, Kees-Pieter Schepman, Marijn A. Huijing, Eva S. J. van der Beek, Martin W. Stenekes, Jeroen Vister, Sebastiaan A. H. J. de Visscher, and et al. 2026. "Three-Dimensional Surgical Planning in Mandibular Cancer: A Decade of Clinical Experience and Outcomes" Cancers 18, no. 2: 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020271

APA StyleYang, L. H., Merema, B. B. J., Kraeima, J., Boeve, K., Schepman, K.-P., Huijing, M. A., van der Beek, E. S. J., Stenekes, M. W., Vister, J., de Visscher, S. A. H. J., & Witjes, M. J. H. (2026). Three-Dimensional Surgical Planning in Mandibular Cancer: A Decade of Clinical Experience and Outcomes. Cancers, 18(2), 271. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020271