Adult-Onset Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Systematic Review of Clinicopathologic, Immunophenotypic, and Therapeutic Characteristics

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

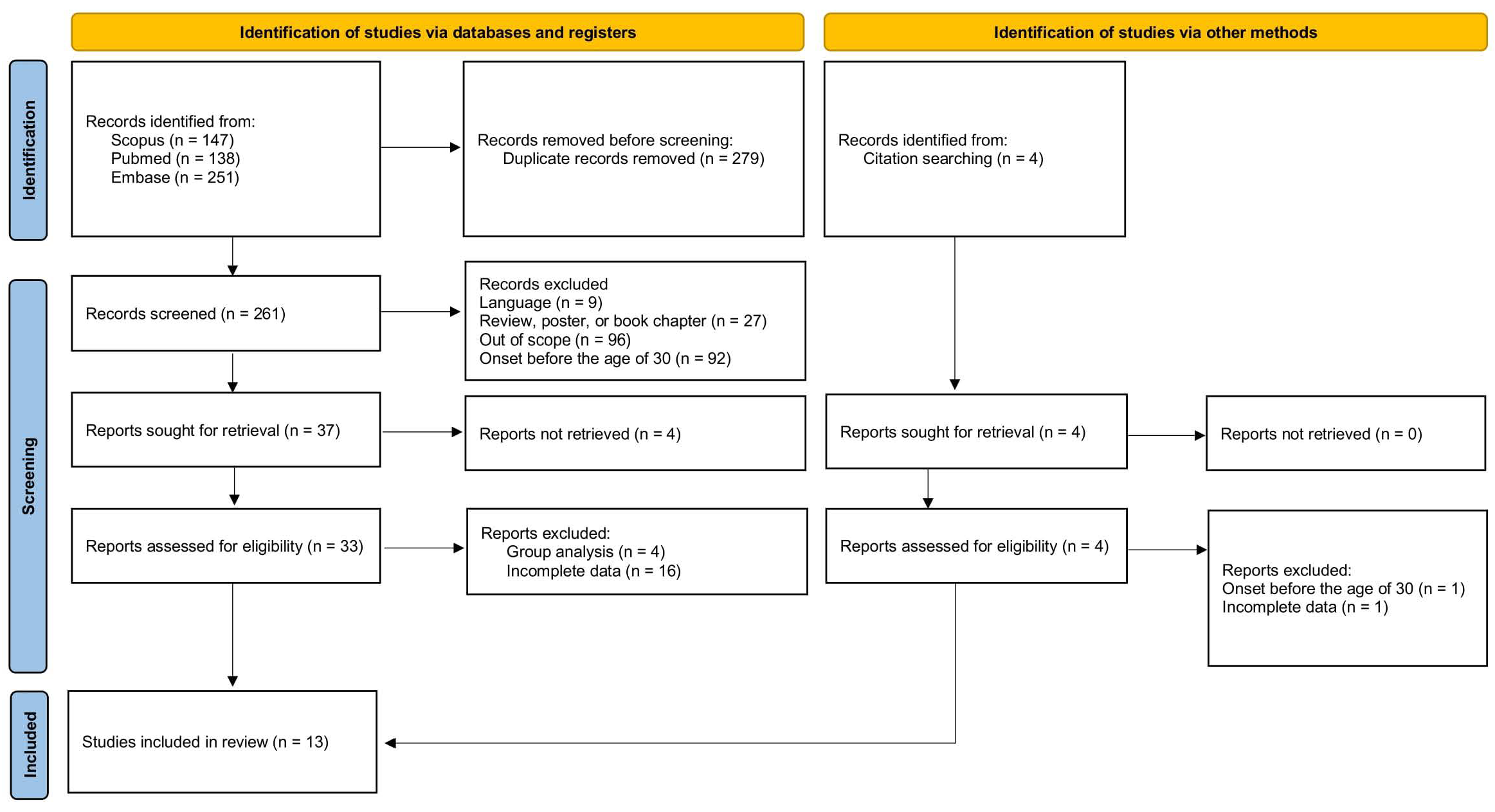

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Diagnosis of Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

4.2. The Role of CD8+ T-Cells

4.3. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides vs. Mycosis Fungoides with Hypopigmented Lesions

4.4. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides vs. Hypopigmented T-Cell Dyscrasia

4.5. Treatment of Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

4.6. Prognosis of Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides

4.7. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MF | Mycosis fungoides |

| hMF | Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides |

| CTCL | Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma |

| TCR | T-cell receptor |

| UVB | Ultraviolet B |

| PUVA | Psoralen plus ultraviolet A |

| UVA1 | Ultraviolet A1 |

| TOX | Thymocyte selection-associated high-mobility group box |

| RCM | Reflectance confocal microscopy |

| HTCD | Hypopigmented T-cell dyscrasia |

| LPP | Large-plaque parapsoriasis |

| MRD | Minimal residual disease |

References

- Sheern, C.; Levell, N.J.; Craig, P.J.; Jeffrey, P.; Mistry, K.; Scorer, M.J.; Venables, Z.C. Mycosis Fungoides: A Review. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2025, 50, 2365–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, F.C.; Sanches, J.A. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Review of Its Clinical Features and Pathophysiology. An. Bras. Dermatol. 2013, 88, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardigó, M.; Borroni, G.; Muscardin, L.; Kerl, H.; Cerroni, L. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides in Caucasian Patients: A Clinicopathologic Study of 7 Cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003, 49, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, B.; Brown, S.; Ackerman, A.B. “Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides” Is Not Always Mycosis Fungoides! Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2005, 27, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zackheim, H.S.; Epstein, E.H.; Grekin, D.A.; McNutt, N.S. Mycosis Fungoides Presenting as Areas of Hypopigmentation: A Report of Three Cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1982, 6, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.X.; Brown, A.D.; Davis, L.S. The Importance of Lymph Node Examination: Simultaneous Diagnosis of Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides and Follicular B-Cell Lymphoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2018, 4, 590–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Shabrawi-Caelen, L.; Cerroni, L.; Medeiros, L.J.; McCalmont, T.H. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: Frequent Expression of a CD8+ T-Cell Phenotype. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2002, 26, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.C.; Kim, Y.C. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides Mimicking Vitiligo. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2021, 43, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, J.T.; Trotter, M.J.; Haber, R.M. Juvenile-Onset Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides Mimicking Vitiligo. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2009, 13, 230–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ip, F.C.; Lee, K.C. A Case of Childhood Onset Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides Initially Diagnosed as Vitiligo. Hong Kong J. Dermatol. Venereol. 2015, 23, 77–80. [Google Scholar]

- Djawad, K. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides Mimicking Leprosy Successfully Treated with Oral and Topical Corticosteroids: A New Great Imitator? Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2021, 30, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigal, M.; Grossin, M.; Laroche, L.; Basset, F.; Aitken, G.; Haziza, J.L.; Belaich, S. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1987, 12, 453–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, G.M.; Niemeyer-Corbellini, J.P.; Quintella, D.C.; Cuzzi, T.; Ramos-e-Silva, M. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A 20-Case Retrospective Series. Int. J. Dermatol. 2018, 57, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathers, R.C.; Scherschun, L.; Malick, F.; Fivenson, D.P.; Lim, H.W. Narrowband UVB Phototherapy for Early-Stage Mycosis Fungoides. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002, 47, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongpraparut, C.; Setabutra, P. Phototherapy for Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides in Asians. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2012, 28, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, C.; Moulonguet, I.; Baudot, N.; Flageul, B.; Dubertret, L. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides in a Light-Skinned Woman. Br. J. Dermatol. 1998, 139, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, D.; Seçkin, D.; Özdemir, B.H. Hypopigmented Macules in an Adult Male Patient. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2008, 33, 667–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stierman, S.; Bedford-Lyon, N. Hypopigmented Discoloration on the Thigh. Cutis 2018, 101, E4–E6. [Google Scholar]

- Uhlenhake, E.E.; Mehregan, D.M. Annular Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Novel Ringed Variant. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2012, 39, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaraphanth, R.; Douglass, M.C.; Lim, H.W. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: Treatment and a 6 1/2 -Year Follow-up of 9 Patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000, 42, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, K.; Langley, A.R. An Illustrative Case of Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep. 2025, 13, 2050313X251359024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafah, M.; Zaidi, S.N.; Kfoury, H.K.; Al Rikabi, A.; Al Ghamdi, K. The Histological Spectrum of Early Mycosis Fungoides: A Study of 58 Saudi Arab Patients. Oman Med. J. 2012, 27, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayasinghe, D.R.; Dissanayake, K.; de Silva, M.V.C. Comparison between the Histopathological and Immunophenotypical Features of Hypopigmented and Nonhypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Retrospective Study. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2021, 48, 486–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tarawneh, A.H.; Al Ta’ani, Z.; Tarawneh, A.; Albashabsheh, L. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Clinicopathological Study of 10 Patients From Jordan (Middle East). Bahrain Med. Bull. 2024, 46, 2227–2233. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelkader, H.A. Basement Membrane Thickness Helps to Differentiate Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides from Clinical and Pathological Mimickers. Int. J. Dermatol. 2023, 62, 1013–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodak, E.; David, M.; Maron, L.; Aviram, A.; Kaganovsky, E.; Feinmesser, M. CD4/CD8 Double-Negative Epidermotropic Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma: An Immunohistochemical Variant of Mycosis Fungoides. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 55, 276–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassab-El-Naby, H.M.M.; Hussein, M.M.; El-Khalawany, M.A. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides in Egyptian Patients. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2013, 40, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Cheikh, S.; Jouini, R.; Klai, S.; Khanchel, F.; Helal, I.; Ben Lazreg, K.; Hedhli, R.; Ben Brahim, E.; Hammami, H.; Fenniche, S.; et al. Detection of Clonal T Cell Receptor Gamma Gene Rearrangements in Mycosis Fungoïdes. Virchows Arch. 2022, 481, S132–S133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.A.H.; Mohamed, A.; Soltan, M.Y. Thymocyte Selection-Associated High-Mobility Group Box as a Potential Diagnostic Marker Differentiating Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides from Early Vitiligo: A Pilot Study. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2021, 87, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichimura, Y.; Sugaya, M.; Morimura, S.; Suga, H.; Mori, S.; Takahashi, H.; Akutsu, Y.; Sato, S. Two Cases of CD8-Positive Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides without TOX Expression. Int. J. Dermatol. 2016, 55, e164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, Y.; Shan, X.; Gao, M. The Differential Diagnosis of Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides and Vitiligo With Reflectance Confocal Microscopy: A Preliminary Study. Front. Med. 2021, 7, 609404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, M.; Huerta, T.; Williams, K.; Hristov, A.C.; Tejasvi, T. Dermoscopic Features of Mycosis Fungoides and Its Variants in Patients with Skin of Color: A Retrospective Analysis. Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2021, 11, e2021048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, S.H.; Bosseila, M.; Hegab, D.S.; Ali, D.A.M.; Kabbash, I.A.; AbdRabo, F.A.G. Evaluation of Diagnostic Accuracy of Dermoscopy in Some Common Hypopigmented Skin Diseases. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2024, 316, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Kruglov, O.; Akilov, O.E. CD8+ T Lymphocytes in Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: Malignant Cells or Reactive Clone? J. Investig. Dermatol. 2023, 143, 521–524.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodney, I.J.; Kindred, C.; Angra, K.; Qutub, O.N.; Villanueva, A.R.; Halder, R.M. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Retrospective Clinicohistopathologic Study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017, 31, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Z.N.; Tretiakova, M.S.; Shea, C.R.; Petronic-Rosic, V.M. Decreased CD117 Expression in Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides Correlates with Hypomelanosis: Lessons Learned from Vitiligo. Mod. Pathol. 2006, 19, 1255–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Darouti, M.A.; Marzouk, S.A.; Azzam, O.; Fawzi, M.M.; Abdel-Halim, M.R.E.; Zayed, A.A.; Leheta, T.M. Vitiligo vs. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides (Histopathological and Immunohistochemical Study, Univariate Analysis). Eur. J. Dermatol. 2006, 16, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal, A.M.; Gantchev, J.; Lagacé, F.; Barolet, A.; Sasseville, D.; Ødum, N.; Charli-Joseph, Y.V.; Salazar, A.H.; Litvinov, I.V. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: Loss of Pigmentation Reflects Antitumor Immune Response in Young Patients. Cancers 2020, 12, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, F.C.; Pereira, B.A.; Sotto, M.N.; Sanches, J.A. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides versus Mycosis Fungoides with Concomitant Hypopigmented Lesions: Same Disease or Different Variants of Mycosis Fungoides? Dermatology 2014, 229, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouloc, A.; Grange, F.; Delfau-Larue, M.H.; Dieng, M.T.; Tortel, M.C.; Avril, M.F.; Revuz, J.; Bagot, M.; Wechsler, J. Leucoderma Associated with Flares of Erythrodermic Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas: Four Cases. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000, 143, 832–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALCALAY, J.; DAVID, M.; SHOHAT, B.; SANDBANK, M. Generalized Vitiligo Following Sézary Syndrome. Br. J. Dermatol. 1987, 116, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Tan, S.H.; Lim, L.C. Leukoderma Associated with Sézary Syndrome: A Rare Presentation. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003, 49, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimouni, D.; David, M.; Feinmesser, M.; Coire, C.I.; Hodak, E. Vitiligo-like Leucoderma during Photochemotherapy for Mycosis Fungoides. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001, 145, 1008–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedland, R.; David, M.; Feinmesser, M.; Fenig-Nakar, S.; Hodak, E. Idiopathic Guttate Hypomelanosis-like Lesions in Patients with Mycosis Fungoides: A New Adverse Effect of Phototherapy. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2010, 24, 1026–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landgrave-Gómez, I.; Ruiz-Arriaga, L.F.; Toussaint-Caire, S.; Vega-Memije, M.E.; Lacy-Niebla, R.M. Epidemiological, Clinical, Histological, and Immunohistochemical Study on Hypopigmented Epitheliotropic T-Cell Dyscrasia and Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides. Int. J. Dermatol. 2020, 59, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magro, C.M.; Hagen, J.W.; Crowson, A.N.; Liu, Y.C.; Mihm, M.; Drucker, N.M.; Yassin, A.H. Hypopigmented Interface T-Cell Dyscrasia: A Form of Cutaneous T-Cell Dyscrasia Distinct from Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides. J. Dermatol. 2014, 41, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, R.; Mahgoub, D.; Zeid, O.A.; Abdel-Halim, D.M.; El-Hawary, M.; Hussein, M.F.; Morcos, M.A.; Aboelfadl, D.M.; Abdelkader, H.A.; Abdel-Galeil, Y.; et al. Hypopigmented Interface T-Cell Dyscrasia and Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Comparative Study. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2018, 40, 727–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, G.S.; Wasserman, D.I.; Byers, H.R.; Demierre, M.F. Hypopigmented T-Cell Dyscrasia Evolving to Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides during Etanercept Therapy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2008, 59, S121–S122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, J.; Sengupta, S.; Gangopadhyay, A. Vitiligo-like Lesions of Mycosis Fungoides Coexisting with Large Plaque Parapsoriasis: An Association or a Spectrum? Indian J. Dermatol. 2006, 51, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboul, S.; Santiago, S.; Weston, G.; Lu, J. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides-like Eruption Following Ixekizumab Treatment. JAAD Case Rep. 2025, 58, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joshi, T.P.; Duvic, M. Unmasking a Masquerader: Mycosis Fungoides Unveiled after Dupilumab Treatment. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2023, 88, e305–e306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukakul, T.; Nitayavardhana, S.; Janyong, N.; Silpa-Archa, N.; Wongpraparut, C. Phototherapy for Early-Stage Mycosis Fungoides in Thais. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2019, 102, 927–933. [Google Scholar]

- Placek, W.; Kaszuba, A.; Lesiak, A.; Maj, J.; Narbutt, J.; Osmola-Mańkowska, A.; Wolska, H.; Rudnicka, L. Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy in Dermatology. Recommendations of the Polish Dermatological Society. Dermatol. Rev. Przegląd Dermatol. 2019, 106, 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alojail, H.Y.; Alshehri, H.; Kaliyadan, F. Clinical Patterns and Treatment Response of Patients With Mycosis Fungoides a Retrospective Study. Cureus 2022, 14, e21231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.Y.; Jin, H.; You, H.S.; Shim, W.H.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, G.W.; Kim, H.S.; Ko, H.C.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, M.B. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides Treated with 308 Nm Excimer Laser. Ann. Dermatol. 2018, 30, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L.; Perna, D.; Callen, J.; Owen, C. 34316 Successful Treatment of Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides in a Pediatric Patient with Excimer Laser. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2022, 87, AB206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.Z.; Jiang, Y.Q.; Xu, X.L.; Zhang, W.; Song, H.; Wang, X.P.; Zeng, X.S.; Sun, J.F.; Chen, H. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Clinicopathological Review of 32 Patients. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 15, 1259–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Gallo, D.; Albarrán Planelles, C.; Linares Barrios, M.; Fernández Anguita, M.J.; Márquez Enríquez, J.; Rodríguez Mateos, M.E. Treatment of Pruritus in Early-Stage Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides with Aprepitant. Dermatol. Ther. 2014, 27, 178–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimak-Pielas, A.; Robak, T.; Braun, M.; Żebrowska, A.; Robak, E. Rapidly Progressing CD8-Negative Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides in Adult Caucasian Male with Good Response to Mogamulizumab. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2025, 105, adv43932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, Y.K.; Koh, M.J.A.; Giam, Y.C.; Tang, M.B.Y.; Chong, W.S.; Tan, S.H. Pediatric Mycosis Fungoides in Singapore: A Series of 46 Children. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2014, 31, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnak, S.; Mark, L.A. Pediatric Mycosis Fungoides: Retrospective Analysis of a Series with CD8+Profile and Female Predominance. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 2022, 44, E994–E998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.H.; Lu, L.; Feng, J.D.; Song, H.B.; Zhang, S.Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, T.; Liu, Y.H. Real-World Clinical Characteristics, Management, and Outcomes of 44 Paediatric Patients with Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2023, 103, 6226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervini, A.B.; Torres-Huamani, A.N.; Sanchez-La-Rosa, C.; Galluzzo, L.; Solernou, V.; Digiorge, J.; Rubio, P. Mycosis Fungoides: Experience in a Pediatric Hospital. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017, 108, 564–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia Ocampo, O.J.; Julio, L.; Zapata, V.; Correa, L.A.; Vasco, C.; Correa, S.; Velásquez-Lopera, M.M. Mycosis Fungoides in Children and Adolescents: A Series of 23 Cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020, 111, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; Qiu, L.; Fu, L.; Liang, Y.; Wei, L.; Xiang, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Ma, L. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Clinical and Histopathology Analysis in 9 Children. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2021, 43, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poszepczynska-Guigne, E.; Bagot, M.; Wechsler, J.; Revuz, J.; Farcet, J.P.; Delfau-Larue, M.H. Minimal Residual Disease in Mycosis Fungoides Follow-up Can Be Assessed by Polymerase Chain Reaction. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 148, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, P.F.; Hsiao, C.H.; Tsai, T.F.; Jee, S.H. Minimal Residual Disease in Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2006, 54, S198–S201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.; McCook, A.A.; Switchenko, J.M.; Varma, S.; Lechowicz, M.J.; Tarabadkar, E.S. Risk Factors for Progression from Early to Advanced Stage Mycosis Fungoides: A Single Center Retrospective Analysis at the Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University. Blood 2021, 138, 1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan Ulutas, G.; Atci, T.; Baykal, C. Comparison of Pediatric- and Adult-Onset Mycosis Fungoides Patients in Terms of Clinical Features and Prognosis in a Large Series. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2025, 29, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castano, E.; Glick, S.; Wolgast, L.; Naeem, R.; Sunkara, J.; Elston, D.; Jacobson, M. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides in Childhood and Adolescence: A Long-Term Retrospective Study. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2013, 40, 924–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.A.; Halpern, J.; Yoo, J.; Thomson, M.; Loffeld, A.; Ramesh, R.; Abdullah, A. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: Should We Worry? Br. J. Dermatol. 2017, 177, 164–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Allen, P.; Case, K.; Zhuang, T.; Jedrzejczak, M.J.; Tarabadkar, E.S.; Lechowicz, M.J.; Bidot, S.S.; Asakrah, S. Transformed Mycosis Fungoides: Clinical and Pathologic Characteristics in a Single Center Retrospective Analysis. Blood 2021, 138, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, D.; Jedrych, J.J.; Ho, J.; Akilov, O.E. Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides with Large Cell Transformation in a Child. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2017, 34, e260–e264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, P.B.; Goyal, S.; Niyogusaba, T.; O’Leary, C.; Ayers, A.; Tarabadkar, E.S.; Khan, M.K.; Lechowicz, M.J. Clinical Presentation and Outcome Differences between Black Patients and Patients of Other Races and Ethnicities with Mycosis Fungoides and Sézary Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol. 2022, 158, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suh, K.S.; Kang, D.Y.; Park, J.B.; Jang, M.S.; Han, S.H.; Kim, S.T. Ichthyosiform Mycosis Fungoides: Clinicopathologic, Immunophenotypic, and Molecular Features. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013, 68, AB146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yuan, X.; Wang, D.; Luo, Z.; Liu, G. A case of hypopigmented mycosis fungoides complicated by acquired ichthyosis. Chin. J. Dermatol. 2020, 53, 1024–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.K.; Hsu, M.M.L.; Lee, J.Y.Y. Fusariosis Occurring in an Ulcerated Cutaneous CD8+ T Cell Lymphoma Tumor. Eur. J. Dermatol. 2006, 16, 297–301. [Google Scholar]

- Naeini, F.N.; Soghrati, M.; Abtahi-Naeini, B.; Najafian, J.; Rajabi, P. Co-Existence of Various Clinical and Histopathological Features of Mycosis Fungoides in a Young Female. Indian J. Dermatol. 2015, 60, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Escala, M.E.; Kantor, R.W.; Cices, A.; Zhou, X.A.; Kaplan, J.B.; Pro, B.; Choi, J.; Guitart, J. CD8+ Mycosis Fungoides: A Low-Grade Lymphoproliferative Disorder. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 77, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diwan, H.; Ivan, D. CD8-Positive Mycosis Fungoides and Primary Cutaneous Aggressive Epidermotropic CD8-Positive Cytotoxic T-Cell Lymphoma. J. Cutan. Pathol. 2009, 36, 390–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaque, A.; Mereniuk, A.; Walsh, S.; Shear, N.H.; Sade, S.; Zagorski, B.; Alhusayen, R. Influence of the Phenotype on Mycosis Fungoides Prognosis, a Retrospective Cohort Study of 160 Patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 933–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case No. | Phototype/Ethnicity | Sex | Age at Symptom Onset (Years) | Age at Diagnosis (Years) | Staging | CD4/CD8 | Treatment | Outcome | Follow-Up (Months) | Final Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [16] | White | f | 31 | 32 | IA | CD4+ | PUVA | CR | 12 | CR |

| 2 [7] | White | f | 43 | 44 | IA (T1N0M0) | CD8+ | tGCS + sunlight | AD | 12 | AD |

| 3 [7] | White | f | 41 | 42 | IB (T2N0M0) | ND | PUVA | AD | 12 | AD |

| 4 [18] | Cauc. | f | 39 | 39 | ND | CD8+ | UVB | PR | 6 | relapse |

| tGCS | PR | 12 | PR | |||||||

| 5 [13] | Cauc. | m | 38 | 53 | IB (T2bN0M0) | ND | tGCS + PUVA | CR | 120 | CR |

| 6 [13] | Cauc. | f | 53 | 54 | IA (T1aN0M0) | ND | tGCS + UVB | PR | 144 | PR |

| 7 [12] | Cauc. | f | 64 | 64 | ND | CD4+ | HN2 + etretinate | PD | 22 | death |

| CVP | PD | |||||||||

| total beam electron | death | |||||||||

| 8 [13] | Cauc. | m | 62 | 63 | IA (T1aN0M0) | ND | tGCS + PUVA | PR | 96 | PR |

| 9 [13] | Cauc. | f | 57 | 63 | IA (T1bN0M0) | ND | tGCS + PUVA | CR | 96 | CR |

| 10 [15] | III | f | 61 | 61 | IA | ND | UVB | CR | 7 | relapse, with good response to UVB |

| 11 [15] | IV | m | 34 | 34 | IA | ND | UVB | PR | ND | ND |

| UVA1 | CR | 108 | CR | |||||||

| 12 [15] | IV | f | 31 | 39 | IB | ND | UVB | CR | 2 | relapse |

| PUVA | CR | ND | ND | |||||||

| 13 [15] | IV | f | 36 | 41 | IA | ND | UVB | PR | 4 | relapse, with good response to UVB |

| 14 [15] | IV | f | 36 | 37 | IA | ND | UVB | CR | 7 | relapse, with good response to tGCS |

| 15 [17] | IV–V | m | 30 | 50 | IA | CD8+ | UVB | CR | 12 | CR |

| 16 [6] | IV–V | f | 40/50s | 50s | IA | CD4+ | UVB | CR | 12 | CR |

| 17 [21] | IV–V | f | 30 | 31 | IA (T1b) | CD4+ | tGCS + UVB | PR | 4 | PR |

| 18 [14] | V | f | 51 | 55 | IA | ND | UVB | CR | 1.5 | relapse |

| 19 [14] | V | f | 52 | 52 | IA | ND | UVB | PR | 1.5 | relapse |

| 20 [15] | V | m | 60 | 60 | IA | ND | UVB | PR | ND | ND |

| PUVA | CR | 2 | CR | |||||||

| 21 [20] | AA | m | 33 | 39 | IA | CD4+ | PUVA | CR | 36 | relapse with good response to PUVA |

| 22 [20] | AA | m | 30 | 40 | IA | CD4+ | PUVA | CR | 5.5 | CR |

| 23 [20] | AA | m | 45 | 46 | IA | CD4+ | PUVA | CR | 24 | relapse with good response to PUVA |

| 24 [19] | AA | f | 49 | 74 | ND | CD8+ | UVB | CR | 6 | relapse |

| UVB | PR | 2 | PR | |||||||

| 25 [13] | Black | m | 40 | 41 | IB (T2aN0M0) | ND | tGCS + UVB | CR | 72 | CR |

| 26 [13] | Black | f | 61 | 69 | IB (T2bN0M0) | ND | PUVA | CR | 72 | CR |

| 27 [13] | Black | f | 44 | 48 | IA (T1aN0M0) | ND | tGCS + PUVA | CR | 84 | CR |

| 28 [13] | Black | m | 67 | 68 | IA (T1aN0M0) | ND | PUVA | CR | 96 | relapse |

| 29 [13] | Mixed | f | 45 | 47 | IB (T2aN0M0) | ND | PUVA | PR | 24 | PD |

| Gem | PD | 24 | death | |||||||

| 30 [13] | Mixed | f | 75 | 75 | IA (T1bN0M0 | ND | tGCS + PUVA | CR | 60 | CR |

| 31 [13] | Mixed | f | 59 | 60 | IB (T2bN0M0) | ND | PUVA | CR | 72 | CR |

| 32 [13] | Mixed | m | 34 | 35 | IA (T1aN0M0) | ND | PUVA | PR | 84 | PR |

| 33 [7] | N.A.I. | f | 43 | 45 | IA (T1N0M0) | CD8+ | BCNU + tGCS | AD | 24 | AD |

| 34 [5] | Nicar. | f | 72 | 75 | ND | ND | HN2 | PR | 2 | PR |

| PUVA | UVB | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of treatment courses | 17 | 16 |

| Complete remission | 13 | 8 |

| Partial remission | 3 | 8 |

| Longest-lasting complete remission (months) | 120 | 72 |

| Relapse after remission (complete or partial) | 4 (25%) | 8 (50%) |

| Feature | Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides | Mycosis Fungoides with Secondary Hypopigmented Lesions |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation | Predominantly hypopigmented patches or plaques | Typical MF lesions (patches, plaques, and nodules) with hypopigmentation developing secondarily |

| Histopathology | Subtle epidermotropism, minimal epidermal damage | Typical MF histology |

| Immunophenotype | In most cases, CD8+ predominant | In most cases, CD4+ predominant |

| Patomechanism | Immune-mediated melanocyte damage | Secondary melanocyte dysfunction due to inflammation or treatment; in rare cases, disease progression |

| Prognosis | Generally favorable, indolent course | Usually associated with good prognosis; occasionally linked to progression |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kimak-Pielas, A.; Robak, E.; Robak, T.; Żebrowska, A. Adult-Onset Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Systematic Review of Clinicopathologic, Immunophenotypic, and Therapeutic Characteristics. Cancers 2026, 18, 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020265

Kimak-Pielas A, Robak E, Robak T, Żebrowska A. Adult-Onset Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Systematic Review of Clinicopathologic, Immunophenotypic, and Therapeutic Characteristics. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):265. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020265

Chicago/Turabian StyleKimak-Pielas, Agnieszka, Ewa Robak, Tadeusz Robak, and Agnieszka Żebrowska. 2026. "Adult-Onset Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Systematic Review of Clinicopathologic, Immunophenotypic, and Therapeutic Characteristics" Cancers 18, no. 2: 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020265

APA StyleKimak-Pielas, A., Robak, E., Robak, T., & Żebrowska, A. (2026). Adult-Onset Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides: A Systematic Review of Clinicopathologic, Immunophenotypic, and Therapeutic Characteristics. Cancers, 18(2), 265. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020265