Prognostic Impact of Unplanned Hospitalization During First-Line Gemcitabine Plus Nab-Paclitaxel Therapy for Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Single-Center Retrospective Observational Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Definitions

Classification of the First UPH Cause

- Progression: UPH prompted by new biliary or duodenal obstruction or by symptoms attributable to disease progression.

- Recurrent biliary obstruction (RBO): UPH for cholangitis or biliary obstruction in patients who had undergone biliary drainage before treatment; RBO was defined in accordance with the TOKYO criteria 2024 [15].

- Adverse events (AE): UPH for conditions or symptoms that could not rule out attribution to GnP.

- Other: UPH for conditions judged clinically to have little direct relation to pancreatic cancer or GnP and not meeting the above definitions (Progression, RBO, AE).

2.4. Endpoints

2.5. Handling of Cut-Off Values for Clinical Variables

2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.7. Ethics

3. Results

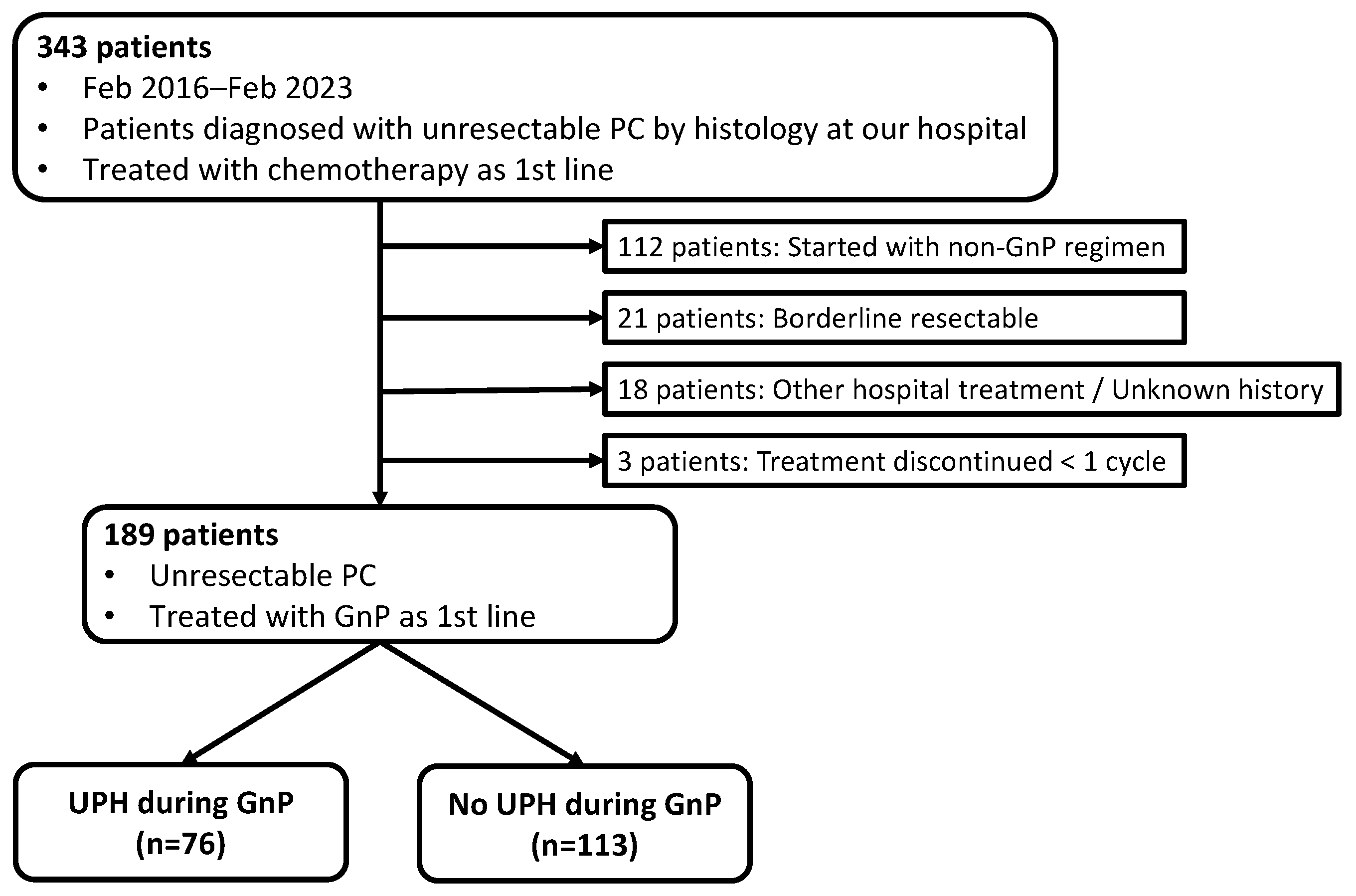

3.1. Patient Selection

3.2. Baseline Characteristics

3.3. Survival by UPH Status

3.4. Prognostic Factor Analysis

3.5. Survival by Reason for UPH

3.6. Risk Factors for UPH

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Clinical Implications of Risk Factors for UPH

4.3. Potential Strategies to Mitigate UPH

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Clinical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PC | Pancreatic cancer |

| GnP | Gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel |

| UPH | Unplanned hospitalization |

| OS | Overall survival |

| TVC | Time-varying covariate |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| RBO | Recurrent biliary obstruction |

| AE | Adverse event |

| ECOG | Eastern cooperative oncology group |

| PS | Performance status |

| mGPS | modified Glasgow Prognostic Score |

| NLR | Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio |

| CA19-9 | Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 |

| ED | Emergency department |

| Alb | Albumin |

| CRP | C-reactive protein |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| AUC | Area under the ROC curve |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| SEMS | Self-expandable metal stent |

| EUS-BD | Endoscopic ultrasound-guided biliary drainage |

| PTBD | Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage |

| NE | Not estimable |

| ADLs | Activities of daily living |

| IADLs | Instrumental ADLs |

| QOL | Quality of life |

| ICU | Intensive care unit |

| G8 | Geriatric 8 |

| FORFIRINOX | folinic acid (leucovorin), fluorouracil (5-FU), irinotecan, and oxaliplatin |

| ePRO | electronic patient-reported outcome |

Appendix A

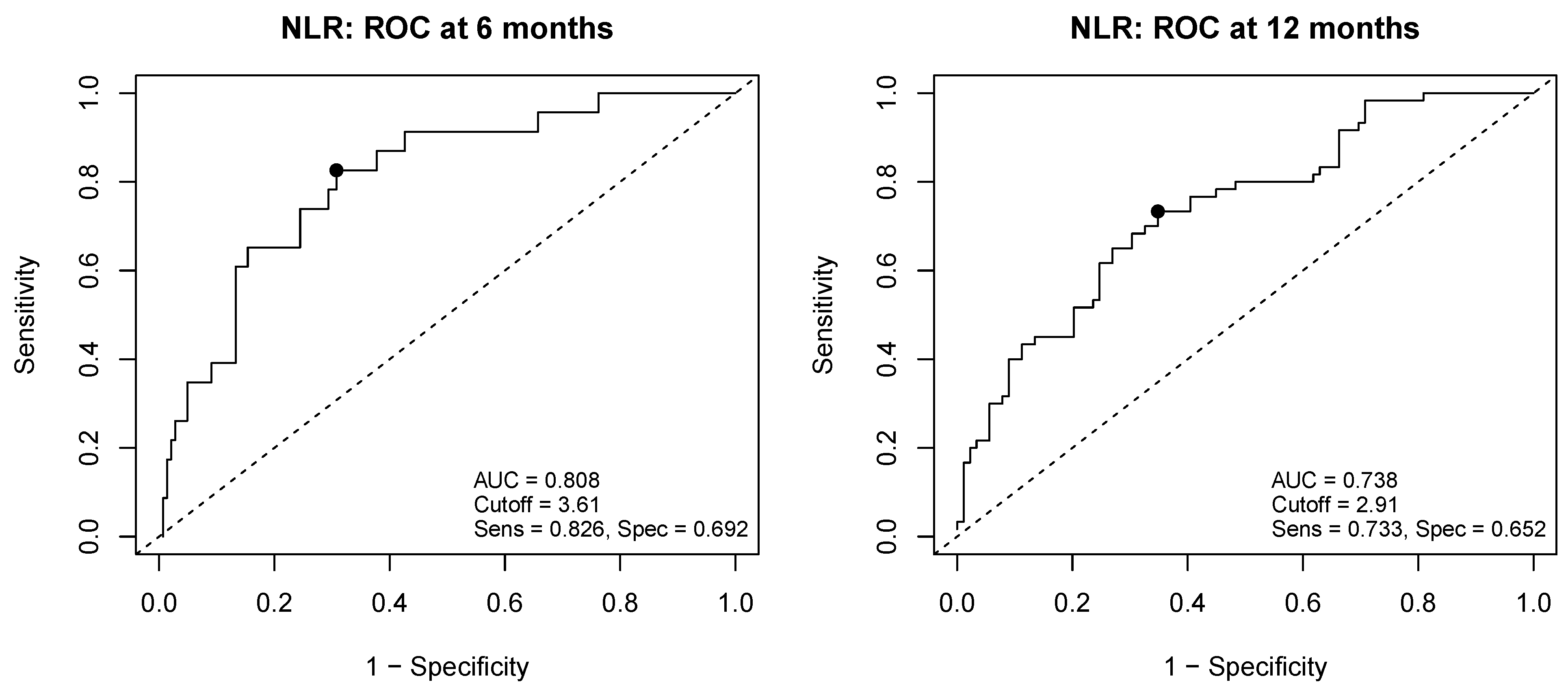

Appendix A.1. Determination of the Optimal NLR Cutoff Values Using Time-Dependent ROC Analysis

Appendix A.2. Sensitivity Analyses Using an Alternative NLR Cutoff (12-Month ROC–Derived Value)

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate Without TVC | Multivariate with TVC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age | |||||||||

| <70 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ≥70 | 0.89 | 0.62–1.29 | 0.54 | ||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| female (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| male | 0.61 | 0.43–0.88 | <0.01 | 0.63 | 0.44–0.92 | 0.02 | 0.64 | 0.44–0.94 | 0.02 |

| ECOG PS | |||||||||

| 0 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ≥1 | 1.67 | 1.08–2.58 | 0.02 | 1.60 | 1.02–2.51 | 0.04 | 1.74 | 1.20–2.52 | <0.01 |

| Tumor location | |||||||||

| Body–tail (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Head | 1.35 | 0.94–1.94 | 0.10 | ||||||

| Depth of invasion | |||||||||

| T3 ≥ (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| T4 | 0.94 | 0.65–1.36 | 0.74 | ||||||

| Disease extension | |||||||||

| Locally advanced (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Metastatic | 1.01 | 0.69–1.48 | 0.96 | ||||||

| Metastatic site | |||||||||

| None (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Liver | 2.02 | 1.40–2.92 | <0.01 | 1.95 | 1.31–2.90 | <0.01 | 2.01 | 1.32–3.06 | <0.01 |

| Lung | 0.90 | 0.52–1.58 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Peritoneal | 0.85 | 0.51–1.43 | 0.55 | ||||||

| Lymph node | 1.29 | 0.84–1.98 | 0.24 | ||||||

| Albumin (g/dL) | |||||||||

| ≥3.0 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| <3.0 | 2.95 | 1.46–5.96 | <0.01 | 1.32 | 0.61–2.85 | 0.48 | 1.20 | 0.59–2.47 | 0.61 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | |||||||||

| ≤1.0 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| >1.0 | 3.03 | 1.99–4.61 | <0.01 | 2.28 | 1.42–3.67 | <0.01 | 2.10 | 1.26–3.50 | <0.01 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | |||||||||

| ≤4.8 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| >4.8 | 1.08 | 0.76–1.56 | 0.66 | ||||||

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | |||||||||

| ≤35.4 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| >35.4 | 1.06 | 0.67–1.69 | 0.79 | ||||||

| NLR | |||||||||

| <2.91 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ≥2.91 | 2.04 | 1.42–2.93 | <0.01 | 1.58 | 1.07–2.33 | 0.02 | 1.58 | 1.08–2.30 | 0.02 |

| Pre-treatment biliary drainage | |||||||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.44 | 0.97–2.14 | 0.07 | 0.95 | 0.61–1.49 | 0.82 | 0.86 | 0.59–1.27 | 0.45 |

| UPH during GnP | |||||||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.97 | 1.37–2.84 | <0.01 | 2.06 | 1.37–3.09 | <0.01 | 2.75 | 1.82–4.15 | <0.01 |

References

- Ito, Y.; Miyashiro, I.; Ito, H.; Hosono, S.; Chihara, D.; Nakata-Yamada, K.; Nakayama, M.; Matsuzaka, M.; Hattori, M.; Sugiyama, H.; et al. Long-term survival and conditional survival of cancer patients in Japan using population-based cancer registry data. Cancer Sci. 2014, 105, 1480–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuroda, T.; Kumagi, T.; Yokota, T.; Azemoto, N.; Hasebe, A.; Seike, H.; Nishiyama, M.; Inada, N.; Shibata, N.; Miyata, H.; et al. Efficacy of chemotherapy in elderly patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer: A multicenter review of 895 patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017, 17, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Von Hoff, D.D.; Ervin, T.; Arena, F.P.; Chiorean, E.G.; Infante, J.; Moore, M.; Seay, T.; Tjulandin, S.A.; Ma, W.W.; Saleh, M.N.; et al. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 1691–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwai, N.; Okuda, T.; Sakagami, J.; Harada, T.; Ohara, T.; Taniguchi, M.; Sakai, H.; Oka, K.; Hara, T.; Tsuji, T.; et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts prognosis in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadokura, M.; Ishida, Y.; Tatsumi, A.; Takahashi, E.; Shindo, H.; Amemiya, F.; Takano, S.; Fukasawa, M.; Sato, T.; Enomoto, N. Performance status and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio are important prognostic factors in elderly patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2016, 7, 982–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asama, H.; Suzuki, R.; Takagi, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Konno, N.; Watanabe, K.; Nakamura, J.; Kikuchi, H.; Takasumi, M.; Sato, Y.; et al. Evaluation of inflammation-based markers for predicting the prognosis of unresectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma treated with chemotherapy. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 9, 408–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Li, J.; Li, J.; Yi, P.; Wu, B.; Zhang, G.; Deng, D.; Li, Y.; et al. Risk and prognostic factors of survival for patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma metastasis to lung: A cohort study. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1521616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vainshtein, J.M.; Schipper, M.; Zalupski, M.M.; Lawrence, T.S.; Abrams, R.; Francis, I.R.; Khan, G.; Leslie, W.; Ben-Josef, E. Prognostic significance of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 in unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer treated with dose-escalated intensity modulated radiation therapy and concurrent full-dose gemcitabine: Analysis of a prospective phase 1/2 dose escalation study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2013, 86, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalaf, N.; Ali, B.; Liu, Y.; Kramer, J.R.; El-Serag, H.; Kanwal, F.; Singh, H. Emergency Presentations Predict Worse Outcomes Among Patients with Pancreatic Cancer. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2024, 69, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliss-Brookes, L.; McPhail, S.; Ives, A.; Greenslade, M.; Shelton, J.; Hiom, S.; Richards, M. Routes to diagnosis for cancer—Determining the patient journey using multiple routine data sets. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 107, 1220–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPhail, S.; Swann, R.; Johnson, S.A.; Barclay, M.E.; Abd Elkader, H.; Alvi, R.; Barisic, A.; Bucher, O.; Clark, G.R.C.; Creighton, N.; et al. Risk factors and prognostic implications of diagnosis of cancer within 30 days after an emergency hospital admission (emergency presentation): An International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership (ICBP) population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitney, R.L.; Bell, J.F.; Tancredi, D.J.; Romano, P.S.; Bold, R.J.; Wun, T.; Joseph, J.G. Unplanned Hospitalization Among Individuals With Cancer in the Year After Diagnosis. J. Oncol. Pract. 2019, 15, e20–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein-Brill, A.; Amar-Farkash, S.; Lawrence, G.; Collisson, E.A.; Aran, D. Comparison of FOLFIRINOX vs Gemcitabine Plus Nab-Paclitaxel as First-Line Chemotherapy for Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2216199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, K.K.W.; Guo, H.; Cheng, S.; Beca, J.M.; Redmond-Misner, R.; Isaranuwatchai, W.; Qiao, L.; Earle, C.; Berry, S.R.; Biagi, J.J.; et al. Real-world outcomes of FOLFIRINOX vs gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in advanced pancreatic cancer: A population-based propensity score-weighted analysis. Cancer Med. 2020, 9, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isayama, H.; Hamada, T.; Fujisawa, T.; Fukasawa, M.; Hara, K.; Irisawa, A.; Ishii, S.; Ito, K.; Itoi, T.; Kanno, Y.; et al. TOKYO criteria 2024 for the assessment of clinical outcomes of endoscopic biliary drainage. Dig. Endosc. 2024, 36, 1195–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenis, C.; Decoster, L.; Bastin, J.; Bode, H.; Van Puyvelde, K.; De Grève, J.; Conings, G.; Fagard, K.; Flamaing, J.; Milisen, K.; et al. Functional decline in older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy: A multicenter prospective study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2017, 8, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giri, S.; Griffin, R.; Newbrough, M.; Williams, G.R.; Richman, J.; Shrestha, S.; Bhatia, S. Risk of early functional decline and its association with overall survival among older adults with newly diagnosed gastrointestinal malignancies undergoing systemic therapy. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2025, 16, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.W.; Jeon, S.K.; Paik, W.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Joo, I.; Lee, J.M.; Lee, S.H. Prognostic value of initial and longitudinal changes in body composition in metastatic pancreatic cancer. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehrels, A.M.; Vissers, P.A.J.; Sprangers, M.A.G.; Fijnheer, N.M.; Pijnappel, E.N.; van der Geest, L.G.; Cirkel, G.A.; de Vos-Geelen, J.; Homs, M.Y.V.; Creemers, G.J.; et al. Longitudinal health-related quality of life in patients with pancreatic cancer stratified by treatment: A nationwide cohort study. eClinicalMedicine 2025, 80, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavakkoli, A.; Elmunzer, B.J.; Waljee, A.K.; Murphy, C.C.; Pruitt, S.L.; Zhu, H.; Rong, R.; Kwon, R.S.; Scheiman, J.M.; Rubenstein, J.H.; et al. Survival analysis among unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients undergoing endoscopic or percutaneous interventions. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 93, 154–162.e155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehviläinen, S.; Kuuliala, A.; Udd, M.; Nurmi, A.; Peltola, K.; Haglund, C.; Kylänpää, L.; Seppänen, H. Cholangitis and Interruptions of Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Associate with Reduced Overall and Progression-Free Survival in Pancreatic Cancer. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2024, 31, 2621–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, M.J.; Camandaroba, M.P.G.; Nassar, A.P., Jr.; de Jesus, V.H.F. Short-term survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer admitted to intensive care unit: A retrospective cohort study. Ecancermedicalscience 2022, 16, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemoun, G.; Weiss, E.; El Houari, L.; Bonny, V.; Goury, A.; Caliez, O.; Picard, B.; Rudler, M.; Rhaiem, R.; Rebours, V.; et al. Clinical features and outcomes of patients with pancreatic cancer requiring unplanned medical ICU admission: A retrospective multicenter study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2024, 56, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, M.; Imaoka, H.; Watanabe, K.; Sasaki, M.; Takahashi, H.; Hashimoto, Y.; Ohno, I.; Mitsunaga, S.; Umemoto, K.; Kimura, G.; et al. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia as a prognostic factor in patients with pancreatic cancer treated with gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel: A retrospective cohort study. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohba, A.; Ozaka, M.; Mizusawa, J.; Okusaka, T.; Kobayashi, S.; Yamashita, T.; Ikeda, M.; Yasuda, I.; Sugimori, K.; Sasahira, N.; et al. Modified Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, Irinotecan, and Oxaliplatin or S-1, Irinotecan, and Oxaliplatin Versus Nab-Paclitaxel + Gemcitabine in Metastatic or Recurrent Pancreatic Cancer (GENERATE, JCOG1611): A Randomized, Open-Label, Phase II/III Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 3345–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch, X.; Moreno, P.; Guerra-García, M.; Guasch, N.; López-Soto, A. What is the relevance of an ambulatory quick diagnosis unit or inpatient admission for the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer? A retrospective study of 1004 patients. Medicine 2020, 99, e19009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, G.A.; Uno, H.; Aiello Bowles, E.J.; Menter, A.R.; O’Keeffe-Rosetti, M.; Tosteson, A.N.A.; Ritzwoller, D.P.; Schrag, D. Hospitalization Risk During Chemotherapy for Advanced Cancer: Development and Validation of Risk Stratification Models Using Real-World Data. JCO Clin. Cancer Inform. 2019, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, M.R.; Loh, K.P.; Mohile, S.G.; Sohn, M.; Webb, T.; Wells, M.; Yilmaz, S.; Tylock, R.; Culakova, E.; Magnuson, A.; et al. External Validation of Risk Factors for Unplanned Hospitalization in Older Adults with Advanced Cancer Receiving Chemotherapy. J. Natl. Compr. Canc. Netw. 2023, 21, 273–280.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodewijckx, E.; Kenis, C.; Flamaing, J.; Debruyne, P.; De Groof, I.; Focan, C.; Cornélis, F.; Verschaeve, V.; Bachmann, C.; Bron, D.; et al. Unplanned hospitalizations in older patients with cancer: Occurrence and predictive factors. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 368–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maire, F.; Hammel, P.; Ponsot, P.; Aubert, A.; O’Toole, D.; Hentic, O.; Levy, P.; Ruszniewski, P. Long-term outcome of biliary and duodenal stents in palliative treatment of patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 101, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshikawa-Kimura, A.; Taira, K.; Maruyama, H.; Ishikawa-Kakiya, Y.; Yamamura, M.; Tanoue, K.; Hagihara, A.; Uchida-Kobayashi, S.; Enomoto, M.; Kimura, K.; et al. Influence of a biliary stent in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer treated with modified FOLFIRINOX. Medicine 2022, 101, e32150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasparini, G.; Aleotti, F.; Palucci, M.; Belfiori, G.; Tamburrino, D.; Partelli, S.; Orsi, G.; Macchini, M.; Archibugi, L.; Capurso, G.; et al. The role of biliary events in treatment and survival of patients with advanced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 1750–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemelä, J.; Kallio, R.; Ohtonen, P.; Saarnio, J.; Syrjälä, H. Impact of cholangitis on survival of patients with malignant biliary obstruction treated with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basch, E.; Deal, A.M.; Kris, M.G.; Scher, H.I.; Hudis, C.A.; Sabbatini, P.; Rogak, L.; Bennett, A.V.; Dueck, A.C.; Atkinson, T.M.; et al. Symptom Monitoring With Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Cancer Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 557–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevins, J.; Bhulani, N.; Goksu, S.Y.; Sanford, N.N.; Gao, A.; Ahn, C.; Paulk, M.E.; Terauchi, S.; Pruitt, S.L.; Tavakkoli, A.; et al. Early Palliative Care Is Associated With Reduced Emergency Department Utilization in Pancreatic Cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 44, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| All (n = 189) | UPH During GnP (n = 76) | No UPH During GnP (n = 113) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Median [IQR] | 68.0 [62.0–74.0] | 68.0 [62.0–74.0] | 68.5 [63.0–75.0] | 0.69 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male, n (%) | 102 (54.0%) | 43 (56.6%) | 59 (52.2%) | 0.66 |

| Female, n (%) | 87 (46.0%) | 33 (43.4%) | 54 (47.8%) | |

| ECOG PS | ||||

| ≥1, n (%) | 38 (20.1%) | 20 (26.3%) | 18 (15.9%) | 0.12 |

| 0, n (%) | 151 (79.9%) | 56 (73.7%) | 95 (84.1%) | |

| Tumor Location | ||||

| Head, n (%) | 86 (45.5%) | 50 (65.8%) | 36 (31.9%) | <0.01 |

| Body–Tail, n (%) | 103 (54.5%) | 26 (34.2%) | 77 (68.1%) | |

| Depth of invasion | ||||

| T4, n (%) | 114 (60.3%) | 44 (57.9%) | 70 (61.9%) | 0.68 |

| T3≥, n (%) | 75 (39.7%) | 32 (42.1%) | 43 (38.1%) | |

| Disease extension | ||||

| Metastatic, n (%) | 132 (69.8%) | 52 (68.4%) | 80 (70.8%) | 0.85 |

| Locally advanced, n (%) | 57 (30.2%) | 24 (31.6%) | 33 (29.2%) | |

| Metastatic site | ||||

| Liver, n (%) | 90 (47.6%) | 36 (47.4%) | 54 (47.8%) | 1.00 |

| Lung, n (%) | 25 (13.2%) | 11 (14.5%) | 14 (12.4%) | 0.84 |

| Peritoneal, n (%) | 28 (14.8%) | 9 (11.8%) | 19 (16.8%) | 0.46 |

| Lymph node, n (%) | 47 (24.9%) | 21 (27.6%) | 26 (23.0%) | 0.58 |

| Pre-treatment biliary drainage, n (%) | 50 (26.5%) | 32 (42.1%) | 18 (15.9%) | <0.01 |

| with Plastic biliary stent, n (%) | 33 (17.5%) | 25 (32.9%) | 8 (7.1%) | <0.01 |

| with SEMS, n (%) | 11 (5.8%) | 2 (2.6%) | 9 (8.0%) | 0.20 |

| with EUS-BD, n (%) | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (2.6%) | 1 (0.9%) | 0.57 |

| with PTBD, n (%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1 (1.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.40 |

| with Other drainage, n (%) | 2 (1.1%) | 2 (2.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.16 |

| History of other cancer, n (%) | 37 (19.6%) | 17 (22.4%) | 20 (17.7%) | 0.54 |

| Family history of PC, n (%) | 18 (9.5%) | 7 (9.2%) | 11 (9.7%) | 1.00 |

| Reason for first UPH (within UPH group) | ||||

| Progression, n (%) | 28 (36.8%) | |||

| RBO, n (%) | 26 (34.2%) | |||

| AE, n (%) | 16 (21.1%) | |||

| Other, n (%) | 6 (7.9%) | |||

| Other (n = 6), one case each: | ||||

| – Depression | ||||

| – Microbiologically confirmed Salmonella gastroenteritis | ||||

| – Osteoporotic compression fracture | ||||

| – Syncope | ||||

| – Hemorrhage from a vestibular schwannoma | ||||

| – Reflux cholangitis after gastrojejunostomy | ||||

| Variable | Univariate | Multivariate Without TVC | Multivariate with TVC | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age | |||||||||

| <70 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ≥70 | 0.89 | 0.62–1.29 | 0.54 | ||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| female (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| male | 0.61 | 0.43–0.88 | <0.01 | 0.62 | 0.43–0.89 | 0.01 | 0.63 | 0.44–0.91 | 0.01 |

| ECOG PS | |||||||||

| 0 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ≥1 | 1.67 | 1.08–2.58 | 0.02 | 1.57 | 1.00–2.47 | 0.05 | 1.72 | 1.17–2.51 | <0.01 |

| Tumor location | |||||||||

| Body–tail (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Head | 1.35 | 0.94–1.94 | 0.10 | ||||||

| Depth of invasion | |||||||||

| T3 ≥ (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| T4 | 0.94 | 0.65–1.36 | 0.74 | ||||||

| Disease extension | |||||||||

| Locally advanced (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Metastatic | 1.01 | 0.69–1.48 | 0.96 | ||||||

| Metastatic site | |||||||||

| None (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Liver | 2.02 | 1.40–2.92 | <0.01 | 2.04 | 1.37–3.03 | <0.01 | 2.12 | 1.40–3.22 | <0.01 |

| Lung | 0.90 | 0.52–1.58 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Peritoneal | 0.85 | 0.51–1.43 | 0.55 | ||||||

| Lymph node | 1.29 | 0.84–1.98 | 0.24 | ||||||

| Albumin (g/dL) | |||||||||

| ≥3.0 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| <3.0 | 2.95 | 1.46–5.96 | <0.01 | 1.36 | 0.64–2.93 | 0.43 | 1.29 | 0.63–2.64 | 0.49 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | |||||||||

| ≤1.0 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| >1.0 | 3.03 | 1.99–4.61 | <0.01 | 1.89 | 1.17–3.06 | <0.01 | 1.72 | 1.01–2.92 | 0.04 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | |||||||||

| ≤4.8 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| >4.8 | 1.08 | 0.76–1.56 | 0.66 | ||||||

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | |||||||||

| ≤35.4 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| >35.4 | 1.06 | 0.67–1.69 | 0.79 | ||||||

| NLR | |||||||||

| <3.61 (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| ≥3.61 | 2.66 | 1.82–3.88 | <0.01 | 2.38 | 1.57–3.61 | <0.01 | 2.37 | 1.64–3.43 | <0.01 |

| Pre-treatment biliary drainage | |||||||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.44 | 0.97–2.14 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 0.60–1.47 | 0.79 | 0.84 | 0.56–1.25 | 0.39 |

| UPH during GnP | |||||||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.97 | 1.37–2.84 | <0.01 | 2.34 | 1.55–3.56 | <0.01 | 3.02 | 2.00–4.56 | <0.01 |

| Variable | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Age | ||||||

| <70 (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| ≥70 | 1.02 | 0.57–1.83 | 0.95 | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| female (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| male | 1.19 | 0.67–2.15 | 0.55 | |||

| ECOG PS | ||||||

| 0 (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| ≥1 | 1.88 | 0.92–3.89 | 0.08 | |||

| Tumor location | ||||||

| Body–tail (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| Head | 4.11 | 2.24–7.72 | <0.01 | 3.18 | 1.52–6.65 | <0.01 |

| Depth of invasion | ||||||

| T3 ≥ (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| T4 | 0.84 | 0.47–1.53 | 0.58 | |||

| Disease extension | ||||||

| Locally advanced (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| Metastatic | 0.89 | 0.48–1.69 | 0.73 | |||

| Metastatic site | ||||||

| None (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| Liver | 0.98 | 0.55–1.76 | 0.95 | |||

| Lung | 1.20 | 0.51–2.80 | 0.68 | |||

| Peritoneal | 0.66 | 0.28–1.56 | 0.35 | |||

| Lymph node | 1.28 | 0.66–2.49 | 0.47 | |||

| Albumin (g/dL) | ||||||

| ≥3.0 (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| <3.0 | 3.27 | 1.11–10.89 | 0.04 | 2.29 | 0.64–8.11 | 0.20 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | ||||||

| ≤1.0 (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| >1.0 | 2.15 | 1.07–4.34 | 0.03 | 1.79 | 0.81–3.92 | 0.15 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | ||||||

| ≤4.8 (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| >4.8 | 0.74 | 0.41–1.33 | 0.31 | |||

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | ||||||

| ≤35.4 (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| >35.4 | 0.72 | 0.33–1.56 | 0.40 | |||

| NLR | ||||||

| <3.61 (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| ≥3.61 | 1.60 | 0.88–2.90 | 0.12 | |||

| Pre-treatment biliary drainage | ||||||

| No (reference) | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 3.57 | 1.86–7.02 | <0.01 | 1.75 | 0.77–3.99 | 0.18 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Watabe, K.; Kan, M.; Ohno, I.; Uchida, S.; Sudo, T.; Yokozuka, K.; Abe, A.; Nakaya, Y.; Ogane, Y.; Kurosaki, H.; et al. Prognostic Impact of Unplanned Hospitalization During First-Line Gemcitabine Plus Nab-Paclitaxel Therapy for Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Single-Center Retrospective Observational Study. Cancers 2026, 18, 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020194

Watabe K, Kan M, Ohno I, Uchida S, Sudo T, Yokozuka K, Abe A, Nakaya Y, Ogane Y, Kurosaki H, et al. Prognostic Impact of Unplanned Hospitalization During First-Line Gemcitabine Plus Nab-Paclitaxel Therapy for Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Single-Center Retrospective Observational Study. Cancers. 2026; 18(2):194. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020194

Chicago/Turabian StyleWatabe, Kazuki, Motoyasu Kan, Izumi Ohno, Sodai Uchida, Taiga Sudo, Koki Yokozuka, Akinori Abe, Yoshiki Nakaya, Yoshiki Ogane, Hiroki Kurosaki, and et al. 2026. "Prognostic Impact of Unplanned Hospitalization During First-Line Gemcitabine Plus Nab-Paclitaxel Therapy for Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Single-Center Retrospective Observational Study" Cancers 18, no. 2: 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020194

APA StyleWatabe, K., Kan, M., Ohno, I., Uchida, S., Sudo, T., Yokozuka, K., Abe, A., Nakaya, Y., Ogane, Y., Kurosaki, H., Sakai, M., Sekine, Y., Takahashi, T., Ouchi, M., Ohyama, H., Sakai, N., Takano, S., Takayashiki, T., Ohtsuka, M., & Kato, J. (2026). Prognostic Impact of Unplanned Hospitalization During First-Line Gemcitabine Plus Nab-Paclitaxel Therapy for Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Single-Center Retrospective Observational Study. Cancers, 18(2), 194. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers18020194