Unlocking the Potential of AI in EUS and ERCP: A Narrative Review for Pancreaticobiliary Disease

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Applications of AI in Diagnostic Pancreaticobiliary Endoscopy

2.1. Endoscopic Ultrasound

| Publication Author, Year | Study Aim | Centers, n | Exams, n | Total nr Frames | Lesions nr Frames | Types of CNN | Dataset Methods | Analysis Methods | Classification Categories | SEN | SPE | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Săftoiu et al., 2008 [20] | Assess accuracy of real- time EUS elastography for detecting malignant pancreatic tumors using postprocessing software for analysis | 2 | NK | NK | NK | ANN (MLP) | A hue histogram was calculated for each frame, summarizing it into a single numerical form, and then averaged across frames for each patient | Train–test split, employing a 10-fold cross–validation | Normal pancreas, CP, pancreatic cancer, and PNET | 91.4% | 87.9% | 0.932 |

| Săftoiu et al., 2012 [21] | Assess accuracy of real-time EUS elastography in focal pancreatic lesions using computer-aided diagnosis by ANN analysis | 13 | 774 | 96,750 | NK | ANN (MLP) | Manually labeled and selected tumor regions in each frame for analysis | Train–test split, employing a 10-fold cross–validation | CP, pancreatic cancer | 87.59% | 82.94% | 0.94 |

| Kurita et al., 2019 [26] | Evaluate the use of AI and DL in analyzing cyst fluid to differentiate between malignant and benign PCLs, comparing it to tumor markers, amylase, and citology | 1 | NK | NK | NK | ANN | Frame labeling of all datasets (malignant cystic lesions were labeled as “1” and benign lesions as “0”) | Train–test split (80–20% with five-fold cross–validation) | Benign vs. malignant cystic pancreatic lesions | 95.7% | 91.9% | 0.966 |

| Kuwahara et al., 2019 [16] | Evaluate the use of AI via a DL algorithm to predict malignancy of IPMNs using EUS images | 1 | NK | 3970 (with data augmentation 508,160) | NK | ResNet | Frame labeling of all datasets (malignant were labeled as “1” and benign lesions as “0”) | Train–test split (90–10% with 10-fold cross–validation) | Benign vs. malignant IPMN | 95.7% | 92.6% | 0.98 |

| Naito et al., 2021 [22] | Train a DL model to assess PDAC on EUS-FNB of the pancreas in histopathological whole-slide images | 1 | NK | 532 | 267 | EfcientNet-B12 | Manual annotations (adenocarcinoma vs. non-adenocarcinoma) | Train–validation–test | ADC vs. non-ADC | 93.02% | 97.06% | 0.984 |

| Marya et al., 2021 [14] | Create an EUS-based CNN model trained to differentiate AIP from PDAC, CP, and NP in real time | 1 | NK | 1,174,461 | NK | ResNet | Video frames and still images were manually annotated and extracted from EUS (AIP, PDAC, CP, and NP) | Train–validation–test (60–20–20%) | PDAC, AIP, CP, or NP | 90% | 78% | NK |

| Udristoiu et al., 2021 [12] | Real-time diagnosis of focal pancreatic masses using a hybrid CNN-LSTM (long short-term memory) model on EUS images | NK | NK | 1300 (with data augmentation 3360) | PDAC: 1240; CPP: 1120; PNET: 1000 | Hybrid CNN-LSTM | Manual annotations (PDAC, CPP, or PNET) | Train–validation–test (80% of images were chosen randomly for validation or training and 20% for testing) | CPP, PNET, PDAC | 98.60% | 97.40% | 0.98 |

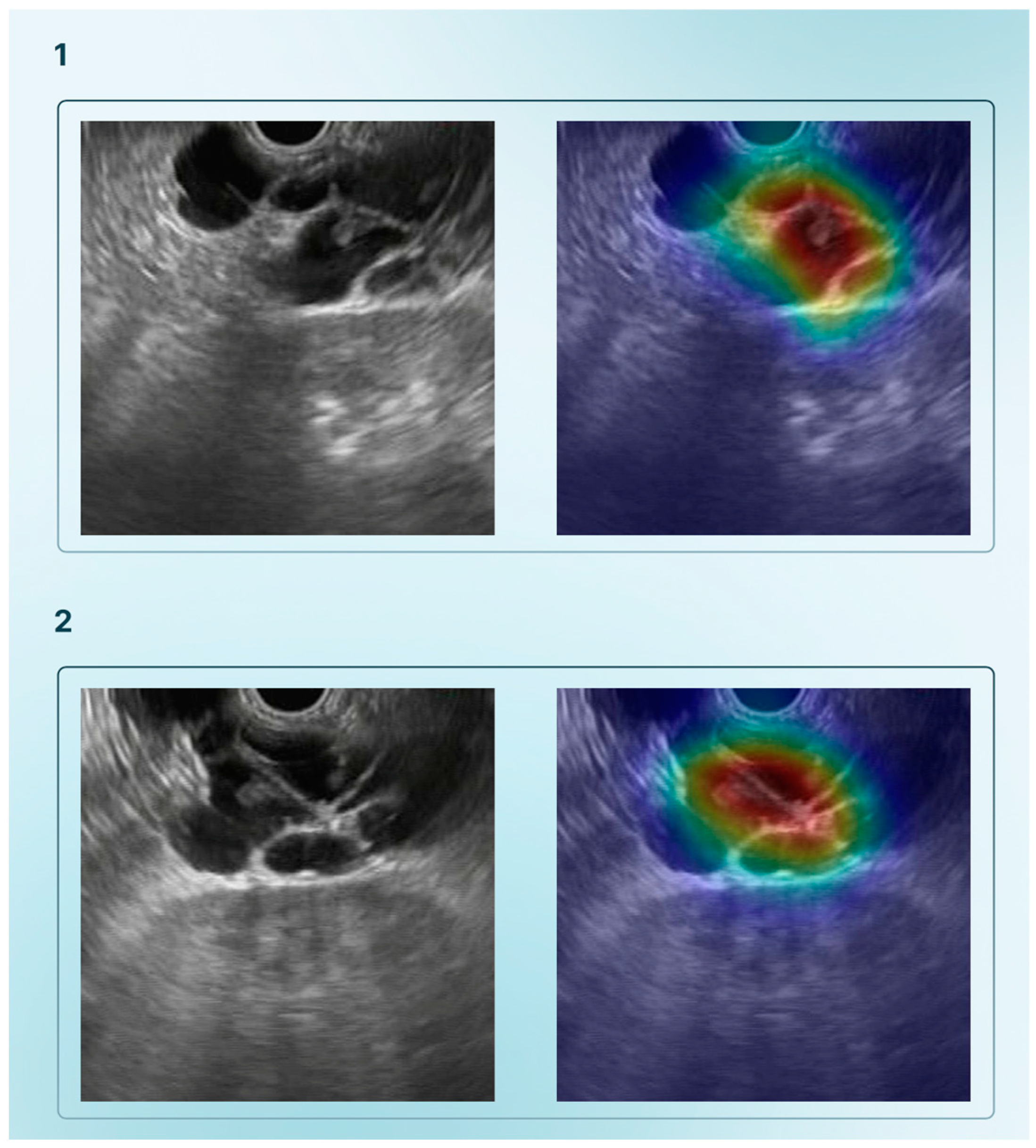

| Tonozuka et al., 2021 [27] | Detect PDAC from EUS images using a DL model | 1 | NK | 1390 static images (with data augmetation 88,320) | NK | CNN and pseudocolored heatmap | Frame labelling of all datasets (PDAC, CP, or NP) | Train–validation–test (training–validation set ratio: 90–10%; 10-fold cross–validation) | PDAC, CP, NP | 92.4% | 84.1% | 0.940 |

| Nguon et al., 2021 [10] | Develop a CNN to differentiate between MCN and SCN | 1 | NK | 211 | MCN: 130; SCN: 81 | ResNet | ROI around the cysts in EUS images were manually selected | Train–test (10 patients from each class—MCN and SCN—were used for testing, while the rest were used for training) | MCN, SCN | Single-ROI: 81.46%; Multi-ROI: 76.06% | Single-ROI: 84.36%; Multi-ROI: 84.55% | Single-ROI: 0.88; Multi-ROI: 0.84 |

| Ishikawa et al., 2022 [23] | Develop a AI-based method for evaluating EUS-FNB specimens in pancreatic diseases | 1 | NK | 298 | NK | AlexNet for DL and SimCLR for contrastive learning | NK | Train–validation–test | PDAC, MFP, AIP, PNET, IPMNs, and metastatic pancreatic tumor | DL: 85.8%; Contrastive learning: 90.3% | DL: 55.2%; Contrastive learning: 53.5% | 0.879 |

| Vilas-Boas et al., 2022 [9] | Develop a DL algorithm that differentiates mucinous and non-mucinous pancrea | 1 | 28 | 5505 | Mucinous PCLs: 3725; Non-mucinous PCLs: 1780 | Xception | Frame labeling of all datasets (Mucinous PCLs and non-mucinous PCLs) | Train–validation–test (80–20%) | Normal pancreatic parenchyma, mucinous PCLs, and non-mucinous PCLs | 98.3% | 98.9% | 1 |

| Qin et al., 2023 [13] | Develop a hyperspectral imaging-based CNN algorithm to aid in the diagnosis of pancreatic cytology specimens obtained by EUS-FNA/B | 1 | NK | 1913 | 890 | ResNet18+ SimSiam | NK | Train–validation–test (60–20–20%) | PDAC cytological specimens, benign pancreatic cells | 93.10% | 91.23% | 0.9625 |

| Tang et al., 2023 [25] | Develop a DL based system, for facilitating diagnosing pancreatic masses in CEH-EUS, and for guiding EUS-FNA in real-time, to improve the ability of distinguishing between malignant and benign pancreatic masses | 1 | NK | Model 1: 4342; Model 2: 296 | Model 1: 3546; Model 2: 167 (PDAC) | Model 1: Unet++ (ResNet-50 used as a backbone) | Manual labeling of all data sets (benign vs. malignant lesions) | Train–test (80–20%) for both models | Benign vs. malignant lesions | - Identification benign/malign pancreatic masses: 92.3%; - Guiding EUS-FNA: 90.9% | - Identification benign/malign pancreatic masses: 92.3%; - Guiding EUS-FNA: 100% | - Identification benign/malign pancreatic masses: 0.923; - Guiding EUS-FNA: 0.955 |

| Saraiva et al., 2024 [15] | Develop a CNN for detecting and distinguish PCN (namely M-PCN and NM-PCN) and PSL (PDAC and PNET) | 4 | 378 | 126,000 | M-PCN: 19,528; NM-PCN: 8175; PDAC: 64,286; PNET 29,153 | ResNet | Each image had a predicted classification related to the highest probability | Train–test split (90–10%) | M-PCN; NM-PCN; PDAC; PNET; NP | M-PCN: 98.9% NM-PCN: 99.3% PDAC:98.7% PNET:83.7% | M-PCN: 99.1% NM-PCN: 99.9% PDAC: 83.7% PNET: 98.7% | NK |

2.2. Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography and Cholangioscopy

| Publication Author, Year | Study Aim | Center n | Exams n | Total nr Frames | Lesion nr Frames | Types of CNN | Dataset Methods | Analysis Methods | Classification Categories | SEN | SPE | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ribeiro et al., 2021 [44] | Develop an AI algorithm for automatic detection of PP in DSOC images | 1 | NK | 3920 | 1650 | Xception | Frame labeling of all datasets (benign finding vs. PP) | Train–validation (80–20%) | Benign findings or PP | 99.7% | 97.1% | 1 |

| Saraiva et al., 2022 [35] | Develop a CNN-based system for automatic detection of malignant BSs in DSOC images | 1 | NK | 11,855 | 9695 | Xception | Frame labeling of all datasets (normal/benign findings vs. malignant lesion) | Train–validation (80–20% with a 5-fold cross-validation) | Normal/benign vs. malignant BSs | 94.7% | 92.1% | 0.988 |

| Pereira et al., 2022 [45] | Develop and validate a CNN-based model for automatic detection of tumor vessels using DSOC images | 1 | 85 | 6475 | 4415 | Xception | Frame labeling of all datasets (presence or absence of TV) | Train–validation split (80–20%) | Benign finding or TV | 99.6% | 99.4% | 1 |

| Marya et al., 2023 [37] | Develop a CNN model capable of accurate stricture classification and real-time evaluation based solely on DSOC images | 2 | NK | 2,388,439 | NK | ResNet50V2 (Exper t-CNN) | Annotation by expert (High-Quality Benign; High-Quality Malignant; High-Quality Suspicious; Low-Quality; Uninformative) | Train–validation split (80–20%) | High-Quality Benign; High-Quality Malignant; High-Quality Suspicious; Low-Quality; Uninformative | 93.3% | 88.2% | 0.941 |

| Robles-Medranda et al., 2023 [46] | Develop a CNN model for detecting neoplastic lesions during real-time DSOC | 5 | NK | CNN1: 818,080; CNN2: 198,941 | NK | YOLO | Frame labeling of all datasets (neoplastic vs. non-neoplastic) | Train–validation (90–10%) | Neoplastic vs. non-neoplastic | 90.5% | 68.2% | NK |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [38] | Develop MBSDeiT, a system aiming to (1) identify qualified DSOC images and (2) identify malignant BSs in real time | 3 | NK | NK | NK | DeiT (Data-efficient Image Transformer) | Annotation Model 1: Qualified/Unqualified Model 2: Cancer/Non-cancer | Train, validation, internal and external testing, prospective testing and video testing | Model 1: Qualified/ Unqualified Model 2: Cancer/Non-cancer | 95.6% (identifying malignant BSs with quality control AI model | 89.1% (identifying malignant BSs with quality control AI model) | 0.976 (identifying malignant BSs with quality control AI model) |

| Saraiva et al., 2023 [36] | Create a DL-based algorithm for digital cholangioscopy capable of distinguishing benign from malignant BSs | 2 | 129 | 84,994 | 44,743 | ResNet | Frame labeling of all datasets (benign vs. malignant strictures, including PP and TV) | Train–validation split (80–20%) | Normal/benign finding or malignant lesion | 83.5% | 82.4% | 0.92 |

| Saraiva et al., 2024 [39] | Validate a CNN model on a large dataset of DSOC images providing automatic detection of malignant BS and morphological characterization | 3 | 164 | 103,082 | 53,678 | NK | Frame labeling of all datasets (normal/benign findings or as a malignant lesion) | Train–validation split (90–10%) | Normal/benign findings; malignant lesion | 93.5% | 94.8% | 0.96 |

3. AI as an Ally to ERCP Procedural Techniques

| Publication Author, Year | Study Aim | Centers n | Patients N | Types of CNN | Dataset Methods | Analysis Methods | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al., 2020 [49] | Develop a difficulty scoring and assistance system (DSAS) for ERCP treatment of CBD stones by accurately segmenting the CBD, stones, and duodensocope | 3 | 1560 (1954 cholangiogram images) | D-LinkNet34 and U-Net | Manual annotation by expert endoscopists of the margin of CBD, stones, and duodenoscope on the cholangiograms. After that, two expert endoscopists and two non-expert endoscopist labeled the diameter of the largest stone and of the duodenoscope, the distal CBD diameter, distal CBD angulation, and distal CBD arm | Train, internal, and external test (train: 70%–test: 30%) | Performance of DSAS segmentation model for stones, CBD, and duodenoscope: mIoU: 68.35%, 86.42% and 95.85%, respectively Performance of DSAS: ARE for stone diameter: 15.97% (95% CI: 14.04–17.90) ARE for CBD length 12.87% (95% CI: 11.18–14.57) ARE for distal CBD angulation: 5.56% (95% CI: 4.81–6.32) ARE for distal CBD arm: 15.91% (95% CI: 13.52–18.31) |

| Kim et al., 2021 [48] | Develop an AI-assisted ERCP procedure to accurately detect the location of ampulla of vater and to estimate cannulation difficulty | 2 | 531 (451 for ampulla detection and 531 for cannulation difficulty) | Ampulla identification: U-Net (VGGNet-based encoder and decoder) Cannulation difficulty: VGG19 with batch normalizatio, ResNet50, and DenseNet161 | Ampulla identification: creation of a pixel-wise soft mask (density map with the probability of whether each pixel belongs to an ampulla) Cannulation difficulty: frame labeling of all data sets firstly in binary classification (easy case/difficult case) and then four-class classification (easy class, class whose cannulation time was over 5 min, class requiring additional cannulation techniques, and failure class) | 5-fold cross-validation | Ampulla identification: mIoU: 0.641, Precision: 0.762, Recall: 0.784 Cannulation difficulty: Easy cases Precision: 0.802, Recall: 0.719; Difficult cases: Precision: 0.507, Recall: 0.611 |

| Huang et al., 2023 [50] | Develop a CAD system to assess and classify the difficulty of CBD stone removal during ERCP | 3 | 173 | CAD | Frame labeling of all datasets (difficult and easy groups) | NK | Difficult” vs. “easy cases” Extraction attempts: 7.20 vs. 4.20 (p < 0.001) Machine lithotripsy rate: 30.4% vs. 7.1% (p < 0.001) Extraction time: 16.59 vs. 7.69 minutes (p < 0.001) Single-session clearance rate: 73.9% vs. 94.5% (p < 0.001) Total clearance rate: 89.1% vs. 97.6% (p = 0.019) |

4. AI for Predictive Analytics and Prognostic Models

Prognostic Models in Therapeutic ERCP

5. Integration of AI with Other Technologies in Pancreaticobiliary Endoscopy

5.1. Telemedicine and Remote Consultation

5.2. Short Reflection About the Future: Multimodal Data Fusion

6. Ethical and Regulatory Considerations

7. Future Challenges

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| EUS | endoscopic ultrasound |

| ERCP | endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| ANN | artificial neural network |

| DSOC | digital single-operator cholangioscopy |

| CADe | Computer-Assisted Detection |

| CADx | Computer-Assisted Diagnosis |

| PCL | pancreatic cystic lesion |

| MCN | mucinous cystic lesion |

| IPMN | intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm |

| SCN | serous cystic neoplasm |

| PPC | pancreatic pseudocyst |

| AUC | area under the curve |

| PDAC | pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PNET | pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor |

| AIP | autoimmune pancreatitis |

| CP | chronic pancreatitis |

| CNN | convolutional neural network |

| LSTM | long short-term memory |

| EUS-nCLE | endoscopic ultrasound-guided needle-based confocal laser endomicroscopy |

| CAD | computer-aided detection and diagnosis |

| BD | bile duct |

| EUS-FNA | endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration |

| EUS-FNB | endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy |

| MOSE | macroscopic on-site evaluation |

| HSI | hyperspectral imaging |

| RGB | Red, Green, Blue |

| CE-EUS | contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound |

| RCT | randomized-controlled trial |

| PPV | positive predictive value |

| NPV | negative predictive value |

| IDBS | indeterminate biliary stricture |

| CBD | common bile duct |

| PEP | Post-Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography Pancreatitis |

| EHR | electronic health record |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| CT | computer tomography |

| MRI | magnetic resonance imaging |

| PET | position emission tomography |

| WGS | whole-genome sequencing |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| HIPAA | Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| SaMD | Software as a Medical Device |

| IMDR | International Medical Device Regulators Forum |

| SEN | sensitivity |

| SPE | specificity |

| MLP | multilayer perceptron |

| CEH-EUS | contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound |

| NP | normal pancreas |

| ADC | adenocarcinoma |

| CPP | chronic pseudotumoral pancreatitis |

| MFP | mass-forming pancreatitis |

| PCN | pancreatic cystic neoplasm |

| M-PCN | mucinous pancreatic cystic neoplasm |

| NM-PCN | non-mucinous pancreatic cystic neoplasm |

| ROI | region of interest |

| NK | not known |

References

- Handelman, G.S.; Kok, H.K.; Chandra, R.V.; Razavi, A.H.; Lee, M.J.; Asadi, H. eDoctor: Machine learning and the future of medicine. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 284, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, H.; Mann, R.; Gandhi, Z.; Perisetti, A.; Zhang, Z.; Sharma, N.; Saligram, S.; Inamdar, S.; Tharian, B. Application of artificial intelligence in pancreaticobiliary diseases. Ther. Adv. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 14, 263177452199305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Stone, J.; Berzin, T. Artificial Intelligence in Pancreaticobiliary Disease; Practical Gastro: Westhampton Beach, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Vila, J.; Fernández-Urién, I.; Carrascosa, J. EUS and ERCP: A rationale categorization of a productive partnership. Endosc. Ultrasound 2021, 10, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subhash, A.; Abadir, A.; Iskander, J.M.; Tabibian, J.H. Applications, Limitations, and Expansion of Cholangioscopy in Clinical Practice. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 17, 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Ogura, T.; Hirose, Y.; Ueno, S.; Okuda, A.; Nishioka, N.; Miyano, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ueshima, K.; Higuchi, K. Prospective registration study of diagnostic yield and sample size in forceps biopsy using a novel device under digital cholangioscopy guidance with macroscopic on-site evaluation. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2022, 30, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmino, M.; Angelo, G.; Morais, H.; Dantas, M.R.; Valentim, R. Computer-aided detection (CADe) and diagnosis (CADx) system for lung cancer with likelihood of malignancy. Biomed. Eng. Online 2016, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerboni, G.; Signoretti, M.; Crippa, S.; Falconi, M.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; Capurso, G. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Prevalence of incidentally detected pancreatic cystic lesions in asymptomatic individuals. Pancreatology 2019, 19, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas-Boas, F.; Ribeiro, T.; Afonso, J.; Cardoso, H.; Lopes, S.; Moutinho-Ribeiro, P.; Ferreira, J.; Mascarenhas-Saraiva, M.; Macedo, G. Deep Learning for Automatic Differentiation of Mucinous versus Non-Mucinous Pancreatic Cystic Lesions: A Pilot Study. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguon, L.S.; Seo, K.; Lim, J.-H.; Song, T.-J.; Cho, S.-H.; Park, J.-S.; Park, S. Deep Learning-Based Differentiation between Mucinous Cystic Neoplasm and Serous Cystic Neoplasm in the Pancreas Using Endoscopic Ultrasonography. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarantis, P.; Koustas, E.; Papadimitropoulou, A.; Papavassiliou, A.G.; Karamouzis, M.V. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: Treatment hurdles, tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2020, 12, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udriștoiu, A.L.; Cazacu, I.M.; Gruionu, L.G.; Gruionu, G.; Iacob, A.V.; Burtea, D.E.; Ungureanu, B.S.; Costache, M.I.; Constantin, A.; Popescu, C.F.; et al. Real-time computer-aided diagnosis of focal pancreatic masses from endoscopic ultrasound imaging based on a hybrid convolutional and long short-term memory neural network model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, C.; Ran, T.; Pan, Y.; Deng, Y.; Xie, X.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, T.; Zhang, B.; et al. A deep learning model using hyperspectral image for EUS-FNA cytology diagnosis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 17005–17017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marya, N.B.; Powers, P.D.; Chari, S.T.; Gleeson, F.C.; Leggett, C.L.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K.; Chandrasekhara, V.; Iyer, P.G.; Majumder, S.; Pearson, R.K.; et al. Utilisation of artificial intelligence for the development of an EUS-convolutional neural network model trained to enhance the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Gut 2021, 70, 1335–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, M.; Agudo, B.; Haba, M.G.; Ribeiro, T.; Afonso, J.; da Costa, A.P.; Cardoso, P.; Mendes, F.; Martins, M.; Ferreira, J.; et al. Deep learning and endoscopic ultrasound: Automatic detection and characterization of cystic and solid pancreatic lesions—A multicentric study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 99, AB8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuwahara, T.; Hara, K.; Mizuno, N.; Okuno, N.; Matsumoto, S.; Obata, M.; Kurita, Y.; Koda, H.; Toriyama, K.; Onishi, S.; et al. Usefulness of Deep Learning Analysis for the Diagnosis of Malignancy in Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms of the Pancreas. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2019, 10, e00045-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machicado, J.D.; Chao, W.-L.; Carlyn, D.E.; Pan, T.-Y.; Poland, S.; Alexander, V.L.; Maloof, T.G.; Dubay, K.; Ueltschi, O.; Middendorf, D.M.; et al. High performance in risk stratification of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms by confocal laser endomicroscopy image analysis with convolutional neural networks (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 94, 78–87.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.; Yao, L.; Ding, X.; Chen, D.; Wu, H.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.; An, P.; et al. Deep learning–based pancreas segmentation and station recognition system in EUS: Development and validation of a useful training tool (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020, 92, 874–885.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, L.; Ding, X.; Chen, D.; Wu, H.; Lu, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. A deep learning-based system for bile duct annotation and station recognition in linear endoscopic ultrasound. EBioMedicine 2021, 65, 103238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săftoiu, A.; Vilmann, P.; Gorunescu, F.; Gheonea, D.I.; Gorunescu, M.; Ciurea, T.; Popescu, G.L.; Iordache, A.; Hassan, H.; Iordache, S. Neural network analysis of dynamic sequences of EUS elastography used for the differential diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2008, 68, 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Săftoiu, A.; Vilmann, P.; Gorunescu, F.; Janssen, J.; Hocke, M.; Larsen, M.; Iglesias–Garcia, J.; Arcidiacono, P.; Will, U.; Giovannini, M.; et al. Efficacy of an artificial neural network–based approach to endoscopic ultrasound elastography in diagnosis of focal pancreatic masses. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 10, 84–90.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, Y.; Tsuneki, M.; Fukushima, N.; Koga, Y.; Higashi, M.; Notohara, K.; Aishima, S.; Ohike, N.; Tajiri, T.; Yamaguchi, H.; et al. A deep learning model to detect pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma on endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Hayakawa, M.; Suzuki, H.; Ohno, E.; Mizutani, Y.; Iida, T.; Fujishiro, M.; Kawashima, H.; Hotta, K. Development of a Novel Evaluation Method for Endoscopic Ultrasound-Guided Fine-Needle Biopsy in Pancreatic Diseases Using Artificial Intelligence. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Sánchez, M.-V.; Napoléon, B. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound imaging: Basic principles, present situation and future perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 15549–15563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Tian, L.; Gao, K.; Liu, R.; Hu, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, J.; Fu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, W.; et al. Contrast-enhanced harmonic endoscopic ultrasound (CH-EUS) MASTER: A novel deep learning-based system in pancreatic mass diagnosis. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 7962–7973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurita, Y.; Kuwahara, T.; Hara, K.; Mizuno, N.; Okuno, N.; Matsumoto, S.; Obata, M.; Koda, H.; Tajika, M.; Shimizu, Y.; et al. Diagnostic ability of artificial intelligence using deep learning analysis of cyst fluid in differentiating malignant from benign pancreatic cystic lesions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonozuka, R.; Itoi, T.; Nagata, N.; Kojima, H.; Sofuni, A.; Tsuchiya, T.; Ishii, K.; Tanaka, R.; Nagakawa, Y.; Mukai, S. Deep learning analysis for the detection of pancreatic cancer on endosonographic images: A pilot study. J. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci. 2021, 28, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, N.S.; Trindade, A.J.; Sejpal, D.V. Determining the Indeterminate Biliary Stricture: Cholangioscopy and Beyond. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2020, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, V.T.; Faigel, D. Diagnosis and treatment of biliary malignancies: Biopsy, cytology, cholangioscopy and stenting. Mini-Invasive Surg. 2021, 5, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadi, M.A.; Itoi, T.; Moon, J.H.; Goenka, M.K.; Seo, D.W.; Rerknimitr, R.; Lau, J.Y.; Maydeo, A.P.; Lee, J.K.; Nguyen, N.Q.; et al. Using single-operator cholangioscopy for endoscopic evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures: Results from a large multinational registry. Endoscopy 2020, 52, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaleh, M.; Gaidhane, M.; Shahid, H.M.; Tyberg, A.; Sarkar, A.; Ardengh, J.C.; Kedia, P.; Andalib, I.; Gress, F.; Sethi, A.; et al. Digital single-operator cholangioscopy interobserver study using a new classification: The Mendoza Classification (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 95, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.-J.; Chen, J.-H.; Xu, H.-J.; Yu, Q.; Liu, K. Efficacy and Safety of Digital Single-Operator Cholangioscopy in the Diagnosis of Indeterminate Biliary Strictures by Targeted Biopsies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.J.; Lim, J.; Han, S.-S.; Park, H.M.; Kim, S.-W.; Lee, W.J.; Woo, S.M.; Kim, T.H.; Won, Y.-J.; Park, S.-J. Distinct prognosis of biliary tract cancer according to tumor location, stage, and treatment: A population-based study. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii-Lau, L.L.; Thosani, N.C.; Al-Haddad, M.; Acoba, J.; Wray, C.J.; Zvavanjanja, R.; Amateau, S.K.; Buxbaum, J.L.; Calderwood, A.H.; Chalhoub, J.M.; et al. American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy guideline on the role of endoscopy in the diagnosis of malignancy in biliary strictures of undetermined etiology: Summary and recommendations. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 98, 685–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, M.M.; Ribeiro, T.; Ferreira, J.P.; Boas, F.V.; Afonso, J.; Santos, A.L.; Parente, M.P.; Jorge, R.N.; Pereira, P.; Macedo, G. Artificial intelligence for automatic diagnosis of biliary stricture malignancy status in single-operator cholangioscopy: A pilot study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2021, 95, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, M.M.; Ribeiro, T.; González-Haba, M.; Castillo, B.A.; Ferreira, J.P.S.; Boas, F.V.; Afonso, J.; Mendes, F.; Martins, M.; Cardoso, P.; et al. Deep Learning for Automatic Diagnosis and Morphologic Characterization of Malignant Biliary Strictures Using Digital Cholangioscopy: A Multicentric Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marya, N.B.; Powers, P.D.; Petersen, B.T.; Law, R.; Storm, A.; Abusaleh, R.R.; Rau, P.; Stead, C.; Levy, M.J.; Martin, J.; et al. Identification of patients with malignant biliary strictures using a cholangioscopy-based deep learning artificial intelligence (with video). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 97, 268–278.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, D.; Zhou, J.-D.; Ni, M.; Yan, P.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, T.; Zhan, Q.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, L.; et al. A real-time interpretable artificial intelligence model for the cholangioscopic diagnosis of malignant biliary stricture (with videos). Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 98, 199–210.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, M.; Widmer, J.; Haba, M.G.; Ribeiro, T.; Agudo, B.; Manvar, A.; Fazel, Y.; Cardoso, P.; Mendes, F.; Martins, M.; et al. Artificial intelligence for automatic diagnosis and pleomorphic morphologic characterization of malignant biliary strictures using digital Cholangioscopy: A multicentric transatlantic study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 99, AB20–AB21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, M.G.-H.; Pereira, P.; Widmer, J.; Ribeiro, T.; Castillo, B.A.; Vilas-Boas, F.; Ferreira, J.; Saraiva, M.M.; Macedo, G. Real-Life Application of Artificial Intelligence for Automatic Characterization of Biliary Strictures: A Transatlantic Experience. Technol. Innov. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 27, 250902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.S.; Abu Dayyeh, B.K.; Bhat, Y.M.; Gottlieb, K.T.; Hwang, J.H.; Komanduri, S.; Konda, V.; Lo, S.K.; Manfredi, M.A.; Maple, J.T.; et al. Confocal laser endomicroscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014, 80, 928–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilonis, N.D.; Januszewicz, W.; di Pietro, M. Confocal laser endomicroscopy in gastro-intestinal endoscopy: Technical aspects and clinical applications. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles-Medranda, C.; Baquerizo-Burgos, J.; Puga-Tejada, M.; Cunto, D.; Egas-Izquierdo, M.; Mendez, J.C.; Arevalo-Mora, M.; Alcivar Vasquez, J.; Lukashok, H.; Tabacelia, D. Cholangioscopy-based convoluted neuronal network vs. confocal laser endomicroscopy in identification of neoplastic biliary strictures. Endosc. Int. Open 2024, 12, E1118–E1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, T.; Saraiva, M.M.; Afonso, J.; Ferreira, J.P.S.; Boas, F.V.; Parente, M.P.L.; Jorge, R.N.; Pereira, P.; Macedo, G. Automatic Identification of Papillary Projections in Indeterminate Biliary Strictures Using Digital Single-Operator Cholangioscopy. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2021, 12, e00418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, P.; Mascarenhas, M.; Ribeiro, T.; Afonso, J.; Ferreira, J.P.S.; Vilas-Boas, F.; Parente, M.P.; Jorge, R.N.; Macedo, G. Automatic detection of tumor vessels in indeterminate biliary strictures in digital single-operator cholangioscopy. Endosc. Int. Open 2022, 10, E262–E268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robles-Medranda, C.; Baquerizo-Burgos, J.; Alcivar-Vasquez, J.; Kahaleh, M.; Raijman, I.; Kunda, R.; Puga-Tejada, M.; Egas-Izquierdo, M.; Arevalo-Mora, M.; Mendez, J.C.; et al. Artificial intelligence for diagnosing neoplasia on digital cholangioscopy: Development and multicenter validation of a convolutional neural network model. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 719–727. [Google Scholar]

- Troncone, E.; Mossa, M.; De Vico, P.; Monteleone, G.; Blanco, G.D.V. Difficult Biliary Stones: A Comprehensive Review of New and Old Lithotripsy Techniques. Medicina 2022, 58, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Kim, J.; Choi, H.S.; Kim, E.S.; Keum, B.; Jeen, Y.T.; Lee, H.S.; Chun, H.J.; Han, S.Y.; Kim, D.U.; et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted analysis of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography image for identifying ampulla and difficulty of selective cannulation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8381. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Lu, X.; Huang, X.; Zou, X.; Wu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, D.; Tang, D.; Chen, D.; Wan, X.; et al. Intelligent difficulty scoring and assistance system for endoscopic extraction of common bile duct stones based on deep learning: Multicenter study. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Xu, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, F.; Wu, D.; Zhou, W.; Wu, L.; Pang, T.; Huang, X.; Zhang, K.; et al. An artificial intelligence difficulty scoring system for stone removal during ERCP: A prospective validation. Endoscopy 2023, 55, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanovic, P.; Salkic, N.N.; Zerem, E. Artificial neural network predicts the need for therapeutic ERCP in patients with suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2014, 80, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Ding, T.; Qiao, S.; Meng, F.; Wang, S.; Li, P.; Wang, X. A novel YOLOv3-arch model for identifying cholelithiasis and classifying gallstones on CT images. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, C.-J.; Yeh, H.-J.; Chang, C.-C.; Tang, J.-H.; Kao, W.-Y.; Chen, W.-C.; Huang, Y.-J.; Li, C.-H.; Chang, W.-H.; Lin, Y.-T.; et al. Lightweight deep neural networks for cholelithiasis and cholecystitis detection by point-of-care ultrasound. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 211, 106382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akshintala, V.S.; Kanthasamy, K.; Bhullar, F.A.; Weiland, C.J.S.; Kamal, A.; Kochar, B.; Gurakar, M.; Ngamruengphong, S.; Kumbhari, V.; Brewer-Gutierrez, O.I.; et al. Incidence, severity, and mortality of post-ERCP pancreatitis: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 145 randomized controlled trials. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2023, 98, 1–6.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, H.; Ohno, E.; Furukawa, T.; Yamao, K.; Ishikawa, T.; Mizutani, Y.; Iida, T.; Shiratori, Y.; Oyama, S.; Koyama, J.; et al. Artificial intelligence in a prediction model for postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Dig. Endosc. 2024, 36, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibugi, L.; Ciarfaglia, G.; Cárdenas-Jaén, K.; Poropat, G.; Korpela, T.; Maisonneuve, P.; Aparicio, J.R.; Casellas, J.A.; Arcidiacono, P.G.; Mariani, A.; et al. Machine learning for the prediction of post-ERCP pancreatitis risk: A proof-of-concept study. Dig. Liver Dis. 2023, 55, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Dong, Z.; Huang, L.; Du, H.; Yang, T.; Luo, C.; Tao, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Wu, L.; et al. Multistep validation of a post-ERCP pancreatitis prediction system integrating multimodal data: A multicenter study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2024, 100, 464–472.e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laymouna, M.; Ma, Y.; Lessard, D.; Schuster, T.; Engler, K.; Lebouché, B. Roles, Users, Benefits, and Limitations of Chatbots in Health Care: Rapid Review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e56930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirunavukarasu, A.J.; Ting, D.S.J.; Elangovan, K.; Gutierrez, L.; Tan, T.F. Large language models in medicine. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1930–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, H.A.; Eisa, T.A.E.; Nasser, M.; Sahib, T.M.; Noor, A.A.; Alyasiri, O.M.; Salisu, S.; Hayder, I.M.; Younis, H.A. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Medicine and Healthcare: Applications, Considerations, Limitations, Motivation and Challenges. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniaci, A.; Lavalle, S.; Gagliano, C.; Lentini, M.; Masiello, E.; Parisi, F.; Iannella, G.; Cilia, N.D.; Salerno, V.; Cusumano, G.; et al. The Integration of Radiomics and Artificial Intelligence in Modern Medicine. Life 2024, 14, 1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagarswamy, K.; Shi, W.; Boini, A.; Messaoudi, N.; Grasso, V.; Cattabiani, T.; Turner, B.; Croner, R.; Kahlert, U.D.; Gumbs, A. Should AI-Powered Whole-Genome Sequencing Be Used Routinely for Personalized Decision Support in Surgical Oncology—A Scoping Review. BioMedInformatics 2024, 4, 1757–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbs, A.A.; Croner, R.; Abu-Hilal, M.; Bannone, E.; Ishizawa, T.; Spolverato, G.; Frigerio, I.; Siriwardena, A.; Messaoudi, N. Surgomics and the Artificial intelligence, Radiomics, Genomics, Oncopathomics and Surgomics (AiRGOS) Project. Artif. Intell. Surg. 2023, 3, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teoh, J.R.; Dong, J.; Zuo, X.; Lai, K.W.; Hasikin, K.; Wu, X. Advancing healthcare through multimodal data fusion: A comprehensive review of techniques and applications. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, W.; Jia, G.; Wu, Z.; Wang, T.; Wang, H.; Wei, K.; Cheng, C.; Liu, Z.; Zuo, C. A multidomain fusion model of radiomics and deep learning to discriminate between PDAC and AIP based on 18F-FDG PET/CT images. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2023, 41, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Zhao, Y.; Xiong, S.; Feng, Y.; Li, P.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, R.; Xie, P.; Luo, Z.; et al. Diagnosing Solid Lesions in the Pancreas With Multimodal Artificial Intelligence: A Randomized Crossover Trial. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2422454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. Epigenomic and Machine Learning Models to Predict Pancreatic Cancer: Development of a New Algorithm to Integrate Clinical, Omics, DNA Methylation Biomarkers and Environmental Data for Early Detection of Pancreatic Cancer in High-Risk Individuals. Available online: https://www.eppermed.eu/funding-projects/projects-results/project-database/imagene/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Mascarenhas, M.; Afonso, J.; Ribeiro, T.; Andrade, P.; Cardoso, H.; Macedo, G. The Promise of Artificial Intelligence in Digestive Healthcare and the Bioethics Challenges It Presents. Medicina 2023, 59, 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, E.A.; Blaiszik, B.; Brinson, L.C.; Bouchard, K.E.; Diaz, D.; Doglioni, C.; Duarte, J.M.; Emani, M.; Foster, I.; Fox, G.; et al. FAIR for AI: An interdisciplinary and international community building perspective. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elangovan, D.; Long, C.S.; Bakrin, F.S.; Tan, C.S.; Goh, K.W.; Yeoh, S.F.; Loy, M.J.; Hussain, Z.; Lee, K.S.; Idris, A.C.; et al. The Use of Blockchain Technology in the Health Care Sector: Systematic Review. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022, 10, e17278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrow, R.; Hatherley, J. The Promise and Perils of AI in Medicine. Int. J. Chin. Comp. Philos. Med. 2019, 17, 79–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, M.; Martins, M.; Ribeiro, T.; Afonso, J.; Cardoso, P.; Mendes, F.; Cardoso, H.; Almeida, R.; Ferreira, J.; Fonseca, J.; et al. Software as a Medical Device (SaMD) in Digestive Healthcare: Regulatory Challenges and Ethical Implications. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Araújo, C.C.; Frias, J.; Mendes, F.; Martins, M.; Mota, J.; Almeida, M.J.; Ribeiro, T.; Macedo, G.; Mascarenhas, M. Unlocking the Potential of AI in EUS and ERCP: A Narrative Review for Pancreaticobiliary Disease. Cancers 2025, 17, 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071132

Araújo CC, Frias J, Mendes F, Martins M, Mota J, Almeida MJ, Ribeiro T, Macedo G, Mascarenhas M. Unlocking the Potential of AI in EUS and ERCP: A Narrative Review for Pancreaticobiliary Disease. Cancers. 2025; 17(7):1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071132

Chicago/Turabian StyleAraújo, Catarina Cardoso, Joana Frias, Francisco Mendes, Miguel Martins, Joana Mota, Maria João Almeida, Tiago Ribeiro, Guilherme Macedo, and Miguel Mascarenhas. 2025. "Unlocking the Potential of AI in EUS and ERCP: A Narrative Review for Pancreaticobiliary Disease" Cancers 17, no. 7: 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071132

APA StyleAraújo, C. C., Frias, J., Mendes, F., Martins, M., Mota, J., Almeida, M. J., Ribeiro, T., Macedo, G., & Mascarenhas, M. (2025). Unlocking the Potential of AI in EUS and ERCP: A Narrative Review for Pancreaticobiliary Disease. Cancers, 17(7), 1132. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17071132